R.G. Cole - Unsung Heroes

description

Transcript of R.G. Cole - Unsung Heroes

-

Reformation Printers: Unsung HeroesAuthor(s): Richard G. ColeSource: The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Autumn, 1984), pp. 327-339Published by: The Sixteenth Century JournalStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2540767 .Accessed: 19/10/2011 09:15

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

The Sixteenth Century Journal is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to TheSixteenth Century Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=scjhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/2540767?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

Sixteenth Century Journal XV (3) 1984

Reformation Printers: Unsung Heroes

Richard G. Cole Luther College

IT IS FREQUENTLY STATED that the Reformation would have been im- possible or would have had little chance of popular acceptance without the rapid spread of typography. The implications of the media revolu- tion go much further than the suggestion that popular acceptance of the Reformation was enhanced by the utilization of the printing press. The Reformation itself seems to be almost unthinkable without taking into consideration the printed pages of Luther's sermons, essays, ad- dresses, and biblical translations. Indeed, the Reformation went hand in hand with book and press. There is in all the centuries preceding the sixteenth century nothing comparable to the print media explosion of the 1520s, an upsurge of activity that coincided exactly with the Ref- ormation in Germany.

Individual authors and their specific works are only half of the story of the printing dimension of Reformation times. The people who cast the type and rolled the ink are frequently overlooked by scholars because they are regarded as mere cogs in the wheel of the printing revolution. The Reformation printer formed an important part of the rapidly growing number of literate people and became an elite, albeit numerically -small new class, a class not based on traditional lines of political status and economic wealth but one based on a very high degree of literacy. In ascertaining the relative merits of the Reforma- tion printer, one may ask: "Is the typist of the paper as important as the author?" No, but one is tempted to reply that the Reformation printer played an especially crucial and significant part in the publish- ing of the Reformation pamphlet, especially in the early and critical years of the Reformation. Printers were often well-educated, skilled, versatile, and pragmatic individuals. They had to ascertain their mar- kets, obtain the necessary manuscripts and then see them through the press. Oftentimes they teamed up with scholarly humanists who served as proofreaders and artists for illustrations.

What was Luther's attitude toward the printers? In Luther's printed works, especially in his Table Talks and Letters, he on occasion addresses his thoughts to the various printers who published his works. Shortly before the beginning of the Reformation in a letter writ- ten on September 9, 1516, to George Spalatin, the chaplain and private secretary of Frederick the Wise, Luther discusses his intentions to pre- pare some of his exegetical lectures on the Psalms for publication. But,

-

328 Sixteenth Century Journal

he maintained, when he finished this task, he wanted them to be printed with his direct supervision, which in this case meant that the printing would have to be done locally by Johann Grunenberg, who had been printing in Wittenberg since 1508. Luther continues by stating that another reason for local printing was that his work would be printed in a rougher typeface. Luther wrote: "I am not impressed with publica- tions printed in elegant type by famous printers. Usually they are trifles, worth only the eraser."'

The resulting avalanche of Luther's Reformation pamphlets printed by dozens of printers in many places followed Luther's wishes. Thousands of Reformation pamphlets were printed in a homely format with bold type. Later, Luther was to regret that some of his printers were indeed not only unknown but did inelegant or even poor printing. In another letter to Spalatin, written in 1521, Luther notes how unhap- py he is with the printing done by Grunenberg on his treatise On Con- fession. Luther wrote: "It is printed so poorly, so carelessly, and con- fusedly, to say nothing of bad typefaces and paper. Johann the printer is always the same old Johann and does not improve." Luther went on to suggest that errant printing compounds confusion in later editions. Bad printing is a sin, said Luther. "I shall send nothing more until I have seen that these sordid money-grubbers, in printing books, care less for their profits than for the benefit of the reader."2 Grunenberg may have been a bad printer but some years later Luther seemed to have forgotten his vexations with him, and in 1532 he stated that Grunenberg was a man of scruples and honestly worried about making too much profit in his printing. Further, "Grunenberg," said Luther, "was a godly man and was blessed."3

At least in the early years of the Reformation Luther felt that it would be necessary to keep a close working connection with his print- ers, not only for the sake of correctness but because he liked to be close at hand to suggest portions of the Bible that he would like to see illus- trated, as he did in the case of Hans Lufft, the famous and rich Witten- berg Bible printer.4 Luther realized the tremendous power of printers and their products; words in print became virtual missiles on the bat- tlefield of ideas. The power of the printed word is suggested by Luther in his treatise On the Papacy in Rome (1520), which was an attack on the Franciscan pamphlet writer Augustine Alveld of Leipzig. Luther

'Luther's Works, ed. H.T. Lehman (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1963), 48: 18-19. Hereafter cited as LW.

2LW, 48: 292. 'LW, 54: 141. 4Carl C. Christensen, Art and the Reformation in Germany (Athens, Ohio: Ohio

University Press, 1979), p. 110.

-

Printers: Unsung Heroes 329

writes: "If he (Alveld) had not put his apelike book into German to poi- son poor laymen, he would have been too insignificant for me to bother with."5 If a bad book could be poison, presumably a good one would be a useful weapon or, as Luther once stated, a book could be a "new vex- ation for the Antichrist and his soldiers.'"6 After twelve more years of much printing and writing, Luther could look back from the apex of his successful career as a reformer and be a bit more reflective about the value of a printed work. He said in one session reported in Table Talk that he would like it if it were possible to have all of his books de- stroyed so that only the sacred writing of the Bible would be read. He was afraid that even his followers would forsake the Bible and only read commentaries upon commentaries. But since it was entirely un- likely that hundreds of thousands of copies of his works could or would be destroyed, he conceded that: " I would like my books to be preserved for the sake of history in order that men may observe the course of events and the conflict with the Pope ...."7 Later in the fall of 1538 Luther echoed the same sentiments when commenting on the writings of his co-reformer Johann Brenz. Luther said Brenz wrote such a big commentary on twelve chapters of Luke that it "disgusts the reader to look into it."8 Apparently, Luther had become so accustomed to the brief Reformation polemical pamphlet that longer works such as he himself had done earlier no longer appealed even to him.

Luther sensed that he was riding the crest of a printing boom and a wave of a relatively new technology. Perhaps it was only natural for a scholar of Luther's caliber to be interested in the various forms of communication, but the special needs and problems of a reform move- ment added a special impetus not only for Luther but also for his print- ers, who were eager to serve the new market for published materials. If printers are the essential link in the new communication process, then more needs to be known about these people of enterprise and skill. One of the problems in obtaining an in-depth picture of the Reformation printer is that with relatively few exceptions not a great deal of infor- mation has survived on the printer, or if it has, it is widely scattered. Available information is often poorly indexed, if indexed at all. The names of printers are seldom indexed in, for example, published edi- tions of Luther's works or in sixteenth-century pamphlet catalogs. Several years ago this writer conducted a computerized sorting of the bibliographical information contained in the relatively large collection of sixteenth-century Reformation pamphlets (Flugschriftensammlung

6LW, 39: 103. 6LW, 48: 230-231. 7LW, 54: 274. 8LW, 54: 311.

-

330 Sixteenth Century Journal

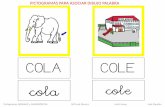

Gustav Freytag) located in the City and University Library in Frank- furt am Main. In the coding of the material I included the coding of printer's name and location of publication as well as other data. Since the names of printers had never been indexed for the collection, the print-out gave me something especially useful to help me understand better the printing dimension of the Reformation. In the overall sam- ple of over three thousand pamphlets, there were three hundred and ninety names of obscure printers who in the course of the sixteenth century had rolled their presses in over one hundred different geo- graphical locations (see figure 1). In the portion relating specifically to works by or about Luther there were over four hundred and fifty-seven editions of pamphlets printed by fifty German printers in twelve dif- ferent locations. About twenty percent of the Luther editions were without a printer's mark or colophon. From the list of names on the print-out, I have been able to gather data on most of Luther's printers, but neither is my present study nor the Freytag collection the total picture (see figure 2).

What kind of people were the German printers? The printers of the Reformation may rival the humanists as being one of the first identifi- able secular groups bringing their support to the cause of the Reforma- tion. Some years ago Bernd Moeller argued that aside from the human- ists, copper miners were the first group to identify with the early Ref- ormation.9 What about the printers? Certainly, they are a smaller per- centage of the population yet probably a more significant group than the miners. There is some evidence that the printers, who were likely to be above average in skill and education, often opted for Reformation theology. Not only did the printer turn the talents of his trade to print- ing of Reformation books, but he, in some cases, chose a career in the parish. Ernest Schwiebert in his "Reformation Lectures" gathered a number of interesting statistics from the old Wittenberger Ordinier- tenbuch of 1539 (first published in 1844).10 Nine occupations were listed from which people had come before they opted to become emer- gency lay preachers. The occupations included merchants, burghers, stonemasons, sextons, schoolmasters, clothiers, and printers. Of the total of thirty-five people listed in various categories, over one-third of them listed their occupation as printer. The high rate of printers be-

"Quoted in Steven E. Ozment, The Reformation in the Cities (New Haven: Yale Uni- versity Press, 1980), p. 124. Two recent books with much useful information are Eliza- beth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. 2 vols. (Cambridge: Cam- bridge University Press, 1979), and Miriam U. Chrisman, Lay Culture, Learned Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982).

10Ernest Schwiebert, "Reformation Lectures delivered at Valpariso University" (Valpariso: Mimeographed Copy, 1937), p. 285.

-

Printers: Unsung Heroes 331

TOWNS

Altenburg

Augsburg

Bamberg

Basel

Erfurt

Leipzig

Munchen

Nurnberg

Strassburg

Tubi ngen

Ulm

Wittenberg

Zurich

Zwickau

Unknown , " 473

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200

Number of polemical editions by Luther and his friends. Some of the total are editions of the same work.

Figure 1. The Years 1518-1529 Major centers of pamphlet production as indicated by data from the years 1518-1529 in the Freytag Collection.

-

332 Sixteenth Century Journal

PRI NTERS

Jorg Gastel

S. Grimm and M. Wirsung

Johann Grunenberg

Jobst Gutknecht

Gabriel Kantz

Melchior Lotter

Hans Lufft

Silvan Otmar

Melchior Ramminger

Georg Rhau

Christian Rodinger

Nicolaus Schirlentz

Wolfgang Stockel

Unknown 665

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Number of polemical pamphlet editions by or about Luther, some are different editions of same work.

Figure 2. Works by Martin Luther and other reformers. Data is from the Freytag Collection.

-

Printers: Unsung Heroes 333

coming preachers is much greater than one might expect to be the nor- mal rate. Even though Schwiebert's sample is a small one, the results add some weight to the assertion that typographic people had a special affinity for the Reformation.

One of the outstanding printing families noted for their production of Luther's pamphlets and Bibles and also for their early espousal of Lutheran doctrine was Melchior Lotter and his sons, Melchior the Younger and Michael, who was married to Luther's first cousin once removed on the Lindemann (maternal) branch of his family tree." Mel- chior the Elder learned the printing trade and married Dorothea Kach- elofen, daughter of the Leipzig printer, Conrad Kachelofen. As so often happened in the sixteenth century, printers who married daughters or widows of printers usually got a printing press in the bargain. Lotter, up to the time of the Reformation, printed short works on handicrafts, mining, school instruction, popular medicine, religious and astrologi- cal tracts, folk literature and items on politics. He was, indeed, one of the foremost printers in the diocese of Meissen and was the official printer for the bishop. Melchior the Elder apparently spent some time with Luther at Leipzig during the debates in 1519 and formed with him a lasting friendship. Lotter's father-in-law (Kachelofen) turned his press over to his son-in-law and spent most of his time running the Kachelofen tavern, which served as the Luther headquarters during the debates with Eck. The contact of Luther with Lotter led to the es- tablishment of a branch printing office in Wittenberg, manned by his two sons, Melchior and Michael.12 After 1519 Duke George of Saxony discouraged Evangelical publications in Leipzig, a factor which also encouraged the branch operation in Wittenberg. Melchior the Elder continued to publish Lutheran works, albeit clandestinely. One of his chief assistants in the print shop in Leipzig, Hermann Tulich, later became a professor at Wittenberg.'3

Another reason behind the formation of a branch office in Witten- berg was that Philip Melanchthon, the young Greek professor at Wit- tenberg, felt the urgent need to have printed Greek texts for his stu- dents. Hand copying of Greek texts seemed obsolete and unnecessary in the age of typography. When Michael and Melchior the Younger ar- rived in Wittenberg, they brought with them Latin and Greek type, as well as bold-faced Gothic. Besides printing many books for the univer- sity, they published many of Luther's writings as well as works by

"Ian Siggins, Luther and his Mother (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981), p. 30. Also see W. G. Tillmans, "The Lotthers: Forgotten Printers of the Reformation," Con- cordia Theological Monthly 22 (1951): 261.

12Alfred Gotze, Die hochdeutschen Drucher der Reformationzeit (Berlin: de Gruy- ter, 1963), p. 29. - ',W. G. Tillmans, "The Lotthers ...," p. 261.

-

334 Sixteenth Century Journal

Melanchthon and Carlstadt. Soon after the arrival of the Lotters in Wittenberg, Luther planned to have them republish works already done by Grunenberg, the printer with the clumsy type and careless typesetters.'4 Also, Luther and his new printers decided that certain types of publications should be printed in fascicles. The sale of the first printing would determine how many more to produce, and the printer would not be stuck with extra sheets. This subscription system may well be one of the first times books were printed in this fashion.15 After a few years Melchior the Younger left Wittenberg quite suddenly and returned to Leipzig. His father was ill, and he may have returned to help his parent, or Melchior the Younger may have been nettled by a new and aggressive printer in Wittenberg by the name of Hans Lufft.16 Nevertheless, Melchior the Younger remained an ally of Luther and continued to publish Reformation tracts until his death in 1542.

Michael Lotter continued working in Wittenberg and kept print- ing fascicles of Luther's Church and House Postil until 1529, at which time he left Luther's city and went to Magdeburg. Eventually, Michael Lotter joined those reformers who opposed the Augsburg and Leipzig interims of 1548, two years after Luther's death. He followed the theology of the "hard line" and "pure" Lutherans led by Flacius Il- lyricus, the strong opponent of Philip Melanchthon. In sum, the Lot- ters may have been some of the most important printers of the early and stormy years of the Reformation. They were skilled printers and sensitive and responsive to Lutheran evangelical ideas. Certainly, they prospered financially, but they are, indeed, at least three of the unsung heroes of the Reformation.

In the middle 1520s the rising star in the Wittenberg printing scene was Hans Lufft, who lived and printed in Wittenberg from 1523 to 1584.17 Lufft printed a variety of pamphlets but most of his pam- phlet work was completed by 1534. Between 1534 and 1574 Lufft's press produced thousands of Luther Bibles.18 Lufft was an accurate and neat printer and was one who was devoted to Luther and the cause of Reformation. His success in mass producing Bibles ultimately gained a fortune as well as fame for Lufft. He became the richest man in Wittenberg.20 Lufft's daughter married the prominent Wittenberg

14LW, 48: 150. 15LW, 48: 150, note 8. 16W. G. Tillmans, "The Lotthers...." p. 263. 17Josef Benzing, Buchdruckerlexikon des 16. Jahrhunderts (Frankfurt a/M.: Klost-

ermann, 1952), p. 181. 18Gotze, p. 54. 19Walter G. Tilimans, The World and Men Around Luther (Minneapolis: Augsburg,

1959), p. 162. 20Gotze, p. 54.

-

Printers: Unsung Heroes 335

physician Andrew Aurifaber, and Luther himself attended the wed- ding.21 By 1550 Lufft was aRatsherr (member of the City Council), and in 1563 he became mayor of Wittenberg. Indeed, Lufft's career is a re- markable combination of skill and business sense which projected him to the forefront of Luther's printers.

About the same time as Lufft was beginning his printing career in Wittenberg, a number of other printers were appearing on the scene. Besides the Grunenbergs (Johann, Hans and George), the Lotters, and Lufft, six more printers had appeared in Wittenberg by 1525. As early as 1521 Andreas Carlstadt had invited Nickel Schirlentz to set up his press in his house. Schirlentz published a large number of pamphlets by and about Luther and continued to publish until 1547. Some of the other printers were undoubtedly apprentices who had begun to print with their own colophons. For example, Hans Weiss had worked with the Lotters until 1525 and then published a number of Luther's pam- phlets on his own press. In 1539 Weiss was called to Berlin and was of- fered a printing monopoly by Elector Joachim II; Weiss became the first printer in Berlin.22

There almost seemed to be an epidemic of printing fever in Witten- berg. The famous portrait painter and woodcut artist Lucas Cranach the Elder became a partner with Christian Doring, a goldsmith, livery stable and restaurant owner, and set up a printing establishment. Be- tween 1522 and 1525 several dozen Luther pamphlets came off their press.23 Joseph Klug did most of the printing for them until 1525 when he too became an independent and with his son published song books. Klug was the first to publish Luther's "A Mighty Fortress.' '24 Cran- ach's talent for utilizing woodcut illustrations made him a natural to become involved in the printing business since the woodcut illustra- tion became the hallmark of the Reformation polemical pamphlet. Cranach was a very close friend of Luther, and Luther addressed him in letters with terms of endearment.25 Strangely, Cranach's Reforma- tion printing venture with Christian Doring has not received much at- tention. Colin Clair, in his recent work A History of European Printing (1976), does not mention Cranach as a printer. Curiously, he does men- tion a press set up in 1911 in Weimar known as the Cranach Press.26 At any rate, Cranach later became mayor of Wittenberg, in 1537 and again in 1540. Cranach's wife was the daughter of the mayor of Gotha.27

21LW, 54: 269. 22Gotze, p. 56. 23Ibid., p. 50. 24Ibid., p. 53. 25LW, 48: 201, note 2; LW, 49: 103. 26Colin Clair, A History of European Printing (New York: Academic Press, 1976), p.

411. 27 Gotze, P. 2.

-

336 Sixteenth Century Journal

Josef Benzing in his Lexicon of Printers (Buchdrucker Lexikon) lists twelve printers active in their trade in Wittenberg during the cru- cial decade of the 1520s. All but one of these (Symphorian Reinhart) are represented in the Freytag data as printers of Luther's works.

As one might expect, Wittenberg had become a powerful commu- nications center for the spread of the Reformation. Other important centers of Reformation printing were Nurnberg, Augsburg, Zwickau, Erfurt, and Basel. These cities are well known for their Reformation activity and Reformation printing, facts which are confirmed by the tabulating of Freytag data. There were dozens of other locations in which the works of Luther and many other reformers were produced. If it were possible to know all of the editions of Luther's works from every press in Germany, it would be a safe assumption that printers who opted for Reformation works in general would print as much of Luther's work as they could. It was as John Froben of Basel wrote to Luther: "We have sold about all of your books except ten copies, and never remember to have sold any more quickly."28

The imperial city of Augsburg was another locus of Reformation printing in the early years of the reform movement. Of the fourteen printers active in the 1520s the Freytag data (which is only one sample and not a definitive list) indicates that seven people, or sixty-five per- cent of the printers in Augsburg, printed works by Luther. Augsburg- ers such as Sigismund Grimm, a doctor of medicine and owner of an apothecary, joined forces with Marx Wirsung, a rich merchant, and published a number of Luther's sermons.29 Silvan Otmar, the son of a prominent Augsburg family, became one of the most prolific printers of Luther's and of other Reformation figures. Silvan had distinguished himself prior to the Reformation with his printing of a pre-Luther ver- nacular German Bible.30 Otmar's son, Valentin, followed in the same tradition. Other Augsburg printers in the 1520s such as Melchior Ramminger and Heinrich Steiner were productive printers but in later years ran into financial troubles. Steiner, for example, tried to enhance his sales by using a false printing location; he claimed his work was produced in the holy city of Wittenberg rather than Augsburg.3"

28Johann Froben to Luther (February 14, 1519) cited in H. J. Hillerbrand, The Ref- ormation in its own Words (London: SCM, 1964), p. 76.

29Gotze, p. 2. 30Ibid., pp. 5-6. Lucien Febvre was impressed by how much political and religious

radicalism could be found among typographic people. He writes: "A Augsbourg, par ex- emple, Hetzer, correcteur de Silvan Otmar, est Fun chefs du clan baptiste de le ville: lui- meme 6crit quelques libelles." See Lucien Febvre and Henri Jean Martin, L'Apparition du Livre (Paris: Albin Michel, 1958), p. 441.

31Ibid., p. 9.

-

Printers: Unsung Heroes 337

In the imperial and commercial city of Nurnberg seven out of nine or seventy-five percent of the total number of printers noted for pam- phlet editions published Luther's work even though the regulations imposed by the magistrates discouraged overly controversial works. Hans Hergott actually was exiled from Nurnberg for printing Anabap- tist works. One of the most prolific Nurnberg printers of Luther's works was Jobst Gutknecht, who was not afraid to have his name con- nected with Luther; Gutknecht frequently printed with a colophon. In general the list of names of printers and places that emerge in the Freytag collection of Reformation pamphlets seems significant. There are almost fifty identifiable printers of Luther's works in the 1520s printing in twelve separate locations in the Freytag data alone. There are another seventy printers in various locations printing mostly Ref- ormation tracts. Overall for the sixteenth century, there are three hun- dred and ninety-one printers, eight hundred and ninety-four authors and one hundred and twenty-five cities noted in the Freytag data. Forty-two of the locations that surface in the Freytag data are men- tioned by Schottenloher in his great bibliography of the sixteenth cen- tury as the object of significant historical research based on the histor- ical records of printing.32 Eighty-two of the smaller locations where printers lived and worked have not been the subject of specific print research. The odds are overwhelmingly in favor of the contention that if a German printer published pamphlets especially in the 1520s, he published Protestant materials. What is often thought of as a war of pamphlets between the followers of Luther and pope in Rome may be seen as a lopsided one.

There were, however, many significant German Catholic printers and a fairly broad-based genre of Catholic materials paralleling the work of the Lutheran printers in the 1520s. But as a group their num- ber seems far less impressive than those printing on the side of the Evangelicals. Some Catholic printers, such as Wolfgang Stockel, print- er in Leipzig, printed Catholic materials only reluctantly after he was forced by Duke George in 1522 to cease publishing Luther's works. But before Stockel acquiesced to the duke's orders, he tried his hand in operating a small press in Grimma in the Austrian Alps. There he pub- lished works by Luther's co-worker Johann Eberlin, but apparently Stockel ran into financial difficulty in Grimma and moved to Dresden, where he printed solely for Catholic polemicists such as Emser, Coch- laus, Alfeld, Petrus Sylvius, and others.33 Also, there were men such as

32Karl Schottenloher, ed., Bibliographie zur Deutschen Geschichte im Zeitalter der Glaubenspaltung 1517-1585 (Leipzig: Hiersemann, 1940), vol. 4.

33Gotze, p. 21. Gotze writes of one printer, Johann Singriener of Vienna, that he "bleibt Katholik" as if it were a rarity among printers to remain Catholic (p. 51).

-

338 Sixteenth Century Journal

Johann Gruninger, one of the few Catholic priests in Strassburg, who until 1531 printed the works of Murner, Cochlaus, Dietenberger, and Wimpfeling. One Catholic polemist, Thomas Murner, became his own printer in order to engage more effectively in the propaganda wars. As a pamphleteer Murner had tried to link Lutheran reformers with the peasant bands who rose up in insurrection between 1523 and 1526. Murner set up his own press in Lucerne and published there until 1529.34 Another prominent Catholic printer in the early Reformation was Johann Weissenberger, a printer-priest in Landshut. Weissenbur- ger published three hundred copies of the papal bull against Luther and a number of pirated second editions of Catholic polemics by Jo- hann Eck, Johann Eckhard, Thomas Murner, a reprint of the Edict of Worms, and a number of anonymous pamphlets directed against Franz von Sickingen and the knights.35 Finally, there was Alexander Weissenhorn, who printed in Augsburg from 1528 to 1539 for Catholic polemicists such as Cochlaeus, Eck and after 1539 printed exclusively for the Ingolstadter theologians. Weissenhorn's press produced a flock of Catholic polemics.36

Given the extent of the explosion of pamphlet literature even as early as 1521, it is not surprising that the Edict of Worms of 1521 de- clared that all Lutheran books and pamphlets be burned. A few years later, in 1525, Ferdinand, the brother of Emperor Charles V and ruler of the Hapsburg possessions of Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Carni- nola, forbade the buying and selling or printing of works by Luther and his co-workers.37 Although local officials had orders to destroy heretical materials, they often hesitated to interfere with pamphlet printing either because they were sympathetic to the ideas contained therein or they refused to interfere with the powerful economic inter- ests of the printing business.38 Moreover, because of the decentralized nature of pamphlet printing, distribution was often rapid; local author- ities were often confronted with a fait-accompli. A final complication in the Catholic move to suppress Protestant printers was the fact that by as early as 1521, there was a tacit acceptance in some areas, such as Electoral Saxony, of the spirit if not the fact of cuis regio, eius religion a condition of local control militating against uniform regulation of any kind.

34Benzing, p. 113. 35Karl Schottenhoher, Die Landhuter Buchdrucker des 16. Jahrhunderts (Nieuw-

koop: de Graaf, 1930, 1967), pp. 2, 4-5. 36Gotze, p. 10. 37Friederich Kapp, Geschichte des Deutschen Buchhandels (Leipzig, 1886), pp.

431-432. 38Louise Holborn, "Printing and the Growth of the Protestant Movement in Ger-

many from 1517 to 1534," Journal of Church History 9 (1942): 135.

-

Printers: Unsung Heroes 339

Certainly, Luther's printers were eager to reap the fruits of good business whether it be a tavern or a printing shop. But many printers seemed to have a special devotion to the Reformation. They, indeed, were the unsung but often prosperous heroes of the Reformation move- ment.

Article Contentsp. [327]p. 328p. 329p. 330p. 331p. 332p. 333p. 334p. 335p. 336p. 337p. 338p. 339Issue Table of ContentsThe Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Autumn, 1984), pp. 259-384Front Matter [pp. 280-340]Baldung's Bewitched Groom Revisited: Artistic Temperament, Fantasy and the "Dream of Reason" [pp. 259-279]Christopher Mont, Anglo-German Diplomat [pp. 281-292]The Expression of the Idea of Toleration in French during the Sixteenth Century [pp. 293-310]An Elizabethan Experiment in Psalmody: Ralph Buckland's Seaven Sparkes of the Enkindled Soule [pp. 311-326]Reformation Printers: Unsung Heroes [pp. 327-339]Vera Philosophia cum sacra Theologia nusquam pugnat: Keckermann on Philosophy, Theology, and the Problem of Double Truth [pp. 341-365]Book Notices [pp. 365-366]Book ReviewsReview: untitled [pp. 367-369]Review: untitled [p. 370]Review: untitled [pp. 371-372]Review: untitled [p. 372]Review: untitled [p. 373]Review: untitled [p. 374]Review: untitled [p. 375]Review: untitled [pp. 375-376]Review: untitled [p. 377]Review: untitled [pp. 377-380]Review: untitled [pp. 380-381]Review: untitled [pp. 381-383]Review: untitled [pp. 383-384]Back Matter