'Whose Theatre is it anyway?" Ancient chorality versus modern drama

Transcript of 'Whose Theatre is it anyway?" Ancient chorality versus modern drama

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

1

[In Flynn, Alex and Tinius, Jonas (eds) Anthropology, Development and Performance: Reflecting on Political Transformations, based on proceedings of a colloquium at the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences (IUAES) conference at Manchester, August 2013. Anthropology and Theatre Series, Palgrave Macmillan (March 2015)]. ‘”WHOSE THEATRE IS IT ANYWAY?”: ANCIENT CHORALITY VERSUS MODERN DRAMA’ This chapter explores the extent to which the relative marginalisation of ‘theatre’ in

the disciplines of anthropology and sociology is the consequence of a set of

assumptions about ‘theatre’ which became naturalised in the early 20th century: in

particular, the notion of a play as its text, and of (a) performance as its realisation. For

many today, the word ‘theatre’ still connotes going to or putting on ‘a play’, and the

word ‘drama’ engagement with psychological realism or some or other imagined

human universality: but both these notions became dominant in the 1880s, when

theatre and acting became increasingly identified with authentic and authored texts.

With this change, theatre became newly serious, respectable, and above all focussed

on the staged work, a provocative object which both challenged and flattered the

analytical and interpretative capacities of the newly inclusive public it implied.

Wherever writing exists, performances, however broadly defined, will have some or

other relationship with forms of textual prescription, record, and imitation: but literary

drama (or modern drama, the new drama, or simply ‘the drama’) emerging together

with late nineteenth-century European interest in the authentic, social realism and

naturalism, marked a significant shift away from a concept of theatre as social ritual

and public event: one which still influences attitudes to theatre today, and has had a

profound impact on approaches to theatre historiography. ‘We should not assume the

conditions of modern theatre as normative’,1 as Zoe Svendsen says: but we should

also look at the implications of this for how we view theatre in other times and

periods.

This move towards an object-centered view of theatre coincided with a growing

interest in psychology, the darkening of the auditorium, and concomitant separation of

audience and performers (‘fourth wall’). The corresponding emphasis on the thing

performed, or performand, and de-emphasis on audience, was reinforced by 1 Svendsen 2012.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

2

subsequent developments in modernism, cinema, and national identity. Current

academic discussion in many disciplines still reflects this ‘commonsense’ view of

performance as the rendering of a pre-existing object - whether text, story or idea. 2

The idea of an ‘original’ which can never be fully realised but only endlessly

approximated, is culturally and historically specific to Western Europe and the

nineteenth-century, as I have suggested elsewhere.3 This chapter uses the example of

ancient Greek theatre to illustrate how this focus on the performative object has

worked to obscure theatre’s perception and function in other times and places as a

representative instance of, and engagement with, a public, community, or audience.

This shift of focus has directed scholarly and popular normative assumptions about

theatrical practices in periods before this change, and outside the Western tradition. It

is important to examine the retroactive impact of this relatively recent modern

dramatic (and Western) paradigm, and to be alert for historiographies which have

viewed earlier theatrical practices through its lens. Its influence has been pervasive,

despite the correction to this view of theatre in the form of Performance Studies,

which evolved out of anthropology,4 and views theatre as a prima facie space of self-

reflexion for its participant societies.5 For example, in many discussions of theatre a

text of some kind is typically sought or expected, or if not, at least an event

circumscribed by a timed start and finish, or an architecturally-limited stage, or a

story centered on individual characters, whose actions, or whose rendering via an

actor, conforms with ideas of psychological plausibility assumed to be universal.

This view of theatre has worked to shrink its hermeneutic and metaphorical potentials.

For as both the symbol and practice of collectivity, ‘theatre’, however variously

conceived, must surely have always had a fundamental relationship to the concerns of

social anthropology, as was recognised at the turn of the nineteenth- and twentieth-

centuries and again in the 1960s.6 It is worth asking why the vision of theatre as

anthropology in the work of Victor Turner and Richard Schechner in the 1960s, for

2 E.g. Hall and Harrop 2011: 10. 3 Foster 2012: 121-122, following e.g. Wayakabashi 2011: 27. 4 E.g. Turner 2011 (1969), 1988; Schechner 1965, 1985. 5 On ritual see also Geertz 1975; Lukes 1975 and Bocock 1974. These were followed by appraisals of ritual and tradition in modern industrialised societies e.g. by Connerton 1989; Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983 and Bordieu 1984, many of whom take cues from Williams 1991 (1954, revised 1966). 6 For example, the so-called Cambridge Ritualists: Ackerman 2002; Calder 1991, and Arlen 1990: for the 1960s, n. 3-4 above.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

3

example, gave rise not to a re-interrogation of the concepts and categories involved,

as is now increasingly the case (witness this volume), but to a schism between

‘Theatre Studies’ on the one hand and ‘Performance Studies’ on the other.

Commodification is part of the picture, and a supposed opposition between ‘plays’ as

commercial entertainment versus as works of art with autonomous values (both

commodify, as does this supposed opposition itself):7 but so is the way such an

object-centered view of theatre has played into the disciplinary agendas of the modern

university.

In Classics, for example, some scholars have been understandably keen to emphasise

the transcendental and autonomous potentials of ‘Greek plays’, 8 as well as the idea of

theatre’s origins in ancient Greece;9 and early Theatre Studies, keen to establish

parameters for its subject-matter, was understandably drawn to the idea of plays as

literature, and to the idea of a repertoire of ‘professional’ productions in which

commercial or critical success was held to correlate with importance.10 Any discipline

concerned to prove the inherent value of an objective subject-matter, to some extent,

has a built-in disincentive to seek out and identify the ethnographer in the

ethnography; and perhaps, to also welcome the implication that the inherent aesthetic

autonomous potentials of the objective works in question cause their repetition. Yet

there is no extra-social space in which such works can occur; and recognizably

repeated works by definition specifically engage with their local and temporal

contexts. Indeed, theatre is a paradigm for this process, inherently invoking the

collective past, as Marvin Carlson, Paul Connerton and others have pointed out.11 The

theatrical has been taken as a useful model for the fundamentally social nature of all

art, for example, by Michael Fried (from art history), or Nicholas Bourriaud (from

sociology), both recently critiqued by Jacques Rancierre’s revision of the role and

agency of the theatre audience.12 This chapter also therefore raises the question of the

role of intellectual institutions, and disciplinary agendas, in perception-creation: in

7 For commodification in this period, Ridout 2006, 2009. 8 Argued explicitly by Hall, who uses the word ‘masterpiece’: Hall 2013: xxxii. 9 E.g. Michael Scott in his recent TV series and forthcoming book ‘Ancient Greece: the Greatest Show on Earth’: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b039gly5 (accessed June 4th 2014). 10 For an introduction to theatre historiography, see Postlewait 2009; Bratton 2003; Bial and Magussen 2010; Postlewait and McConachie 1989 (and similar subsequent proceedings of the IFTR Historiography Working Group: http://theaterhistoriography.wordpress.com/, accessed June 4th 2014). 11 Carlson 2010; Connerton 1989. 12 Fried 1988, 1998; Bourriaud 2002; Rancierre 2011, a recent key text in Performance Studies.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

4

particular, the potency of ideas of origins, periodization, and diachronic continuity, in

which ideas of ancient Greek theatre have played a central role. Whatever actually

happened on the Athenian acropolis in the mid-fifth century B.C., it has been an

imaginary site in which the very idea of ‘theatre’ has been constructed, and contested.

References to theatre history, or a ‘history of theatre’ often mask an unexamined

assumption that there is a unitary and transhistorical set of practices meaningfully the

same in cultural contexts as diverse as, say, a dramatic competition in a five-day

festival in fifth-century B.C Athens, nineteenth-century Britain, or the global

present.13 ‘Greek drama’, in its modern reception, contributes centrally to such

powerful historiographic imaginaries of sequence and objectivity.

This chapter touches on two key moments of creation in what are now, for us, ‘Greek

plays’: the contrast between original seasonal choral competition in the dramatic

festivals of fifth-century B.C. Athens and their subsequent fourth-century B.C.

reperformance; and the ‘revolutionary’ discovery in late nineteenth-century Britain

that supposedly authentic versions of these texts could be effective for a modern

audience, which – along with authentic Shakespeare performances - helped establish

the idea of drama as literary.

In Britain at the turn of the twentieth century ‘Greek plays’ became newly reified as

part of moves to extend education to all, and to develop a quality national theatrical

repertoire, at the same time as in a contrasting move, the discipline of anthropology

sought to dethrone a classical Atheno-centric ideal, and to question the appropriation

of classical Greece as the origins of an imperial Western identity.14 Later continental

explorations of Athenian drama by structural anthropologists such as Levi-Strauss,

Jean Paul Vernant and Vidal-Naquet as exemplary for sociological and

anthropological principles have similarly existed side by side (with some exceptions)

13 To question this traditionally Athenocentric view of the origins of the Western theatrical tradition is a current focus of classical scholarship: see Eric Csapo’s review of Bosher 2012 (Classical Journal Online, Oct 5, 2013). 14 Philhellenic idealism was initially associated with pre-unification Germany: see Foster, Wilson and Roche (eds) 2013. In Britain Queen Victoria had long used the imagery of classical Greece to represent the British establishment, and by the end of the nineteenth-century many, such as liberal prime-minister Gladstone, for example, were politically invested in the potential of non-Western archaeology to correct a jingoism implicit in such classicizing. This was part of the impetus behind excavations in Crete (by Arthur Evans) and for some, the appeal of Egyptomania. These currents are in evidence in, for example, the discussions of the so-called Cambridge Ritualists and Fraser’s Golden Bough.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

5

with strands in classical scholarship and theatre studies committed to a view of a

‘Greek plays’ as autonomous text-based aesthetic objects. That this narrative of a

Greek-originated ‘theatre’ has not been more thoroughly interrogated suggests the

importance of historically-contextualising not only cultural events themselves, but

also the complexly social subject-positions which attribute their evolving definition

and value. Aesthetics and sociology are not only linked in the embodied experience of

individual subjectivity, but in the broader collective constructions of history.15

Perhaps an example of the potency of this object-centered view of theatre is the fact

that classical scholars have only relatively recently recognised the crucial importance

of distinguishing Athenian drama’s origins in choral competition from the later

reification of a handful of these as reperformed texts (recent studies which constitute a

‘choral turn’);16 or that Theatre Studies has only relatively recently recognised the

importance of including in its purview so-called amateur practices.17 Both

disciplinary strands are now contributing to a wider current debate about the

conceptual boundaries of theatre and the theatrical.18 But critiques of this modern

dramatic paradigm have of course existed since it began. Theatre practitioners such as

Brecht, Artaud and Beckett, who have famously objected to its depoliticising effects,

its emphasis on the text as masterpiece, on character-centered narratives about

individuals rather than social conditions or systems, and its distanced safety as a

bourgeois ritual, have themselves been subsumed into a historiographic reception

which has turned them into chronologically iterated texts.19 The recent changes in

practice given epochal expression in Hans-Thies Lehmann’s 2006 Post-Dramatic

Theatre have now challenged this idea of theatre definitively.20 But a new kind of

prompt to question our concepts of theatre and theatre history also exists in the form

15 Connerton 1989; Bourriaud 2002. 16 Billings, Budelmann and Macintosh 2013: 2. See also Gagné and Hopman 2013. 17 Eg Nadine Holdsworth’s AHRC-funded research project on Amateur theatre at Warwick University: http://amateurdramaresearch.com/ (accessed June 4th 2014). For the need to embrace amateur practice, and the argument against the conventional amateur-professional distinction, see Dobson 2011: 1-11; more recently, Ridout 2013. 18 Eg Meineck 2013; Davis, J. and Smythe 2012. 19 Cf the recent attempt to faithfully reproduce Schechner’s Dionysus in 69 by University of Texas Students in 2009, which Schechner himself pointed out was impossible. 20 Lehmann 2006 (trans. Jürs-Munby). For discussion, see her preface; for a critical view, Fensham 2012. Lehmann reserves the term ‘pre-dramatic’ for ancient Greek and medieval theatre, marking ‘dramatic’ theatre as beginning with Shakespeare: Lehmann 1991, extended in Lehmann 2013. I am grateful to Karen Jürs-Munby for this reference, and her helpful comments on this chapter. For post-dramatic theatre in general, see her co-edited volume Jürs-Munby, Carroll, and Giles 2013.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

6

of the digital and global present, which draws attention to the agency of audiences,

collectivity, and publics, and the negotiation of authorities at play in processes of

selection, record, and repetition.21 Where Artaud denounced the hagiography of the

aesthetic object in 1938 by inveighing against the ‘masterpiece’,22 our present era is

witnessing the end of the object altogether, as the legal terms of a recent Capitol

Records lawsuit suggest.23 It is no longer objects, but access which is being bought

and sold. In an environment of ‘recognition capital’, familiarity is a key commodity: a

critical mass of ‘hits’ constitutes a virtual entity.24 In a digital world, where a thing is

who knows about it, flash mobs are theatre par excellence, as some scholars have

noted;25 and the rise of second-screening, plus the extraordinary popularity of a wide

variety of alternative ‘live’ screen content in local cinemas in Britain since 2009,

suggests the previous importance of dynamics of social identity which had been at

play in past temporally-specific and scarce film exhibition at movie theatres.26 A

revisioning of theatre as complex social practice is thus a timely correction of its still

normative conception as an aesthetic object. Theatre and performance, as collective

phenomena about multiplicity and indeterminacy, are increasingly useful tools to

think with.27

Most scholars in any discipline would not discuss, say, ‘religion’ or ‘politics’ without

at least referring to the problem of language, and the culturally-situated nature of such

concepts. But for whatever complex reasons, the same sensitivity has not typically

attached to the term ‘theatre’, which is often used as if its referents can be universally

assumed. Yet for ancient Athenians, questions of theatre were of course questions of

21 For the implications of digital culture, see e.g. Jenkins 2008; Lessig 2001 and 2008; and Shirky 2008. 22 Artaud 1958: 74-83. 23 The acquittal of digital resale company Redigi for infringing copyright by facilitating the selling on of previously-purchased rights in digital music files was based on a finding that in digital environments there is no legal distinction between original and copies: http://newsroom.redigi.com/redigi-wins-major-victory-in-court-hearing-over-pre-owned-digital-music-capitol-records-emi-vs-redigi/ (accessed March 17th 2014). 24 The Annoying Orange is an example: a private individual posted home-made You-Tube videos, which after a million hits became a TV series, clothing line, merchandise franchise, and is now a movie in development: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Annoying_Orange (accessed Nov 4th 2013). 25 Anderson 2013. 26 Theatron, in ancient Greek, originally described the seats, the place where audiences watch something or other, whatever there was to see (theama): see http://academic.reed.edu/humanities/110tech/theater.html# (accessed June 4th 2014). 27 Cull and Minors 2012: 4. See also the Arnolfini/Bristol Performing Documents project and April 2013 conference: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/arts/research/performing-documents/project-description/ (accessed June 4th 2014).

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

7

both politics and religion. Our modern European languages tend to separate in their

vocabulary experiences which were then captured as inseparable in the mythological

figure and concept of Dionysus. God of mimetic illusion, altered mental states,

collective behaviour (maenadism combines all three) and profoundly associated with

death and the afterlife, Dionysus is never safe: but the dionysiac is typically

something which people do, or experience, together.

Current studies in Classics recognise the role of Aristotle’s Poetics in establishing a

distinct existence for the texts of Athenian drama from their quintessentially political

choral origins. It is not Athenian drama which Aristotle was attempting to explain, but

the massive and widespread reperformance of a few of its texts beyond Athens a

century later. As Martin Revermann puts it:

‘...contextualised studies of Athenian drama have led to a radical re-evaluation

of the plays as largely choral events, thus putting the chorus (back) in the

interpretative centre of the dramatic texts. This insight marks a sharp departure

from a long tradition of scholarship informed by Aristotle’s Poetics, and

shaped by the idea that Athenian drama reached its full level when it broke

away from its choral origins (Poetics 1449a 19-15).’28

This renaissance of interest in chorality offers useful contrast with modern drama’s

reification of a play as its text. The explosion of performances of Greek drama since

the 1960s, especially by radical theatre collectives and post-colonial and marginal

groups taking ensemble and physical theatre approaches, can itself be seen as an

ongoing creative reaction to this tradition of investment in the objectivity of ancient

Greek dramatic texts: creative practices which have in turn stimulated changes in

scholarship. 29 What follows looks at the original choral nature of Athenian drama and

at Aristotle’s crucial role in directing attention away from it, before turning to the

earliest so-called ‘archaeological’ productions of the authentic dramatic texts of

Greek drama and Shakespeare in Britain in the 1880s, which, I argue, played a key

role in the emergence of the modern dramatic paradigm. 28 Revermann 2013. 29 Most famously, Richard Schechner’s ‘Dionysus in 69’ (on which see Zeitlin 2011, in Hall, Macintosh and Wrigley’s edited volume Dionysus Since 69, which offers additional examples); for recent productions in New York, see Meineck 2013.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

8

Chorality lost and found: or how Greek Tragedy became both ‘Greek’, and

‘Tragic’

That Athenian drama became a model for the idea of the text-based play, and of play-

based theatre, is ironic: for the fifth-century B.C. Athenian dramatic competitions

whose textual traces would later become ‘Greek plays’ were ritualised forms of

collective self-questioning, developed from, and extending the metaphorical and

physical potentials of, traditional choral performance.30 Understanding of the original

circumstances which gave rise to these texts requires the abandoning not just of terms

like ‘theatre’ and ‘drama’, with their later very different accreted meanings, but as

Oddone Longo said in Zeitlin and Winkler’s groundbreaking 1990 Nothing to do with

Dionysus: Athenian Drama in its Social Context, also any ideas of ‘text’ and

‘author’.31

The grand procession for which these static performances were an end point (what we

now call ‘dramas’ were initially called ‘circular choruses’32), the marching displays of

Athenian war-orphans in full hoplite armour which preceded them, the first day of

dithyrambs from each of the ten Attic demes, and the five day Athenian festival itself

of which the dramatic competition was one part, were all describable as choreuein.

What is now referred to by the title Oedipus Tyrannus, written by the Athenian

general Sophocles, was in its own day one quarter of a losing four-part competition

entry then referred to as a ‘chorus granted by the city’, with the same twelve young

men performing three tragedies and a satyr play in a single day. This tour de force

physical accomplishment was itself part of the theama (wonder, thing looked at). The

chorus leader or trainer was the named victor in inscriptions, with writer’s names

30 For an excellent introduction to this scholarship see Gagné and Hopman 2013: 17-23. For other overviews, see Green 1996; Wiles 1997; Easterling 1997; Cartledge 1997, Goldhill and Osborne 1999; Csapo 1994; Kowlazig 2007 and Revermann and Wilson (eds) 2008; with critical angles on this scholarship from Padel and Bierl 2009. Zimmerman usefully summarises current debates in Classics about Greek tragedy in Brill’s Pauly Supplement 5 The Reception of Classical Literature: Walde (ed) 2012: 480-489. 31 Longo, 1990: 13. Zeitlin and Winkler 1990 followed notable engagement with the civic and social aspects of Greek drama by Calame 1977 (trans 1996) and Pickard-Cambridge 1968, among others. 32 Csapo 2013.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

9

appearing only after 448 B.C.33 The Greater or City Dionysia was the city’s principle

expense of the year (it cost the same as the invasion of Sicily, for example; one

ancient commentator said its exorbitant cost was a factor in Athens losing the

Peloponnesian war), and attendance was obligatory. In the manner of orations in the

Athenian lawcourts, which were argued in the first person plural, these performances

expressed the voice of a ‘we’, rather than that of an individual speaking for, or on

behalf of, the city.34 The audience were the performers, and the city the set: there was

no ‘off stage’ in an Athenian dramatic festival. The city itself, in the visual field of

spectators, was a geographical participant in the narratives.35

Choral activity was above all participatory: choreuein is something you do, not view.

As audiences today who play football for fun might go to watch a professional

football match, some scholars say almost all those watching an Athenian drama would

themselves at one time have danced and sung in a lyric or dramatic chorus. Even the

most conservative suggest a figure of at least 10%, and acknowledge that the other

90% would likely have participated in other kinds of choral performances at other

times of year. Seasonal choral dance was an embedded aspect of local custom in the

Attic countryside, whose residents flooded into Athens for the Greater Dionysia: so

those watching these choruses would have been the sons and grandsons of earlier

singer-dancers, or grandfathers and great-grandfathers of future ones. The dithyrambs

with which the festival began appear to have been an opportunity to precisely

guarantee wide participation: fifty boys and fifty men from each of the ten demes of

Attica performed traditional songs and dances originally associated with welcoming

Dionysus into the city.36 Two days of comedies in competition, each with different

choruses of twenty four, were followed by three days of tragic choruses. For these

participant-audiences, the sport or team game of choral dramatic competition was a

transhistorical space which connected both past and future, offering a social identity

via the ritual repetition not of a text, but of embodied action (singing-and-dancing, or

33 Vase painting depicts only choruses until the 430s B.C., when an interest in actors appears: Csapo 2010: 12-13. 34 As excitement about the festival spread, and Athens succeeded militarily, the performances became the self-conscious display of Athenian accomplishment to its foreign visitors: tributary city-states opened the ceremonies by displaying their ‘gifts’ in the theatre, which were then formally carried in procession to the highly visible acropolis treasury above, the Parthenon. 35 Meineck 2013: 8-9. 36 For the social function of dithyrambic participation, see Wilson 2000, 2007.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

10

melpein, for which there is no single English word)37 in calendrical or seasonal time.38

As such Athenian choruses were not only an emblem of collective performance, but

also of precisely its provocative multiplicity, and its ability to extend that collectivity,

or rather to pose the question of its extension, in time and space. As Renaud Gagné

and Marianne Hopman have recently argued, the chorus, as the words of choral odes

(‘songs’) so often indicate, metaphorically explored tensions between the individual

and the group, the physically present and the re-presented, uniqueness and

repeatability, the local and its transcendence. 39 As Claude Calame puts it:

‘song-and-dance ensembles of maidens, men or women were fundamentally

social and civic events integral to an elaborate system of self-presentation and

communication centered on the polis...Their song unfolds both in the specific

time of the performance and in cyclical temporality of ritual...choral

polyphony [is] the ability not just to mean more than one thing at once but to

‘mean’ in utterly different respects.’40

Without reconceiving these ‘plays’ as choruses, i.e. as participant theatre through

which audience, performers, authors and producers ritually performed their diverse

and historical collectivity, it is easy to miss the extent to which Athenian drama,

which flourished at the same time as the city’s brief experiment with demokratia, was

the enactment and symbol of precisely the challenge of collective decision-making.41

Athenian tragedy’s characteristic interest in the unreliable power of speech, and in

considering alternate ways of looking at an issue, is an acknowledgment of the

difficulty of collective decision-making, or bouleuesthai,42 a difficulty of which it was

possible to be both proud and scared. ‘Democracy’, regardless of its various

appropriations since then, was in these novel circumstances a self-evidently counter- 37 And for which the muse is Melpomenē. 38 For an interesting discussion of the relationship between commemorative ritual and the calendar see Connerton 1989. Seasonality itself – fertility, harvest – is one of the core associations of Dionysus cf. his role as the god of wine, and associated grapevine imagery. 39 Gagné and Hopman 2013: 25-28. 40 Calame 2013. 41 Geometric patterning, and the awe the accuracy of unison inspired, was a feature of later fourth century reperformance (see below, p. ). 42 The bouleuterion was an alternate name for the Athenian pnix, a hemispherical auditorium, also on the Acropolis, where collective policy was decided. In many towns and cities in classical antiquity the bouleuterion and theatron often maintained an exact symbolic architectural equivalence: in the ancient Greek city of Messene on the Peloponnese, for example, not only the basic shape is the same but Roman refacing in marble uses the same decorative pattern for both hemispherical auditoria.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

11

intuitive idea. The processes of demokratia in which every Athenian citizen43 had an

equal vote but numerical majority ruled practically guaranteed perennial

disagreement: it is significant that powers of persuasion and the fallible nature of

evidence and logical argument are central features not only of Athenian tragedy, but

also of Athenian philosophy. It is not easy to accept a system where everyone puts in

a single pebble and almost a majority shares the same view but all are asked to drop

their cause and accept a decision against them because one or two misguided

individuals happen to choose otherwise.44 In such circumstances it is helpful to

dramatise that whatever view is held, there is always another point of view; or that no

single position is ever entirely right or wrong; or that no-one can know for sure the

course of future events or the ‘right action’ at the time: only with hindsight. For Edith

Hall, the difficulty of collective decision-making, or ‘deliberation’ – finding the right

counsel, advice, or course of action (boulē) drives Athenian tragedy into existence

and gives it its key characteristics; for Simon Goldhill, thinking along similar lines

about the power of language to persuade one way or the other, the essence of tragedy

is the conflict, or agōn, with krisis, or the need for decision (krineein = to decide, or

judge) bringing it to a head. Defining features of Greek tragedy, such as its interest in

the unreliable power of speech, the indeterminacy of meaning, the danger of taking

single-sided or single-minded moral positions, or the irredeemably perspectival nature

of truth or justice, reflect these built-in difficulties of collective decision-making and

the inherent drama of winner-takes-all voting. The chorus stand as a symbol of, and

exemplify in their speech and songs, the necessarily fraught negotiation of

irreconcilably multiple points of view.

In much of Athenian tragedy, the act, or thing done (dra-ma) is the speech act. The

historical emergence of drama (the past participle of the Greek verb dra-ein, to do or

make) has been associated with the decision to have an individual actor separately

impersonate one of the characters in traditional choral storytelling, who instead of

speaking as part of the chorus, is thus liberated to interact with it. Others prefer to

locate the beginning of drama in the moment when Aeschylus (525-456 B.C.) added a

second actor, allowing interaction between impersonated characters: the favoured

43 A category, it should be noted, which did not include women or foreigners and was economically based on slave labour. 44 The meaning, for many, of the Oresteia triology (c. 458 B.C.): see e.g. Goldhill 2004.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

12

example is the scene in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon (c. 458 B.C.) when Agamemnon,

arriving home after the Trojan war, refuses to step down from his chariot onto

precious fabrics as a dangerously hubristic act, only for Clytemnestra to persuade him

in real time to do what moments before he declared he never would.45 A speech act

(persuasion) leads directly to another kind of act, and both are en-acted for the benefit

of live witnesses, problematizing the distinction between words and deeds, or

suggesting the force of words as deeds.

In this same play Aeschylus explicitly satirises collective decision-making, when the

chorus of old men ‘deliberate’ about how to react to the sound of Agamemnon’s cries

as he is stabbed inside the palace. The following choral exchange of multiple points of

view follows several hundred lines (almost a sixth of the play) from Cassandra in

which she predicts that she and Agamemnon are about to be killed: and the same

chorus in their alter-ego as non-characterised ode-singers have also already

foreshadowed this revenge in song. Both these precedents vividly frame their

surprising (and funny) inability to decide what to do, when they hear Agamemnon

yell inside the house:

Agamemnon: Ahh! I’ve been hit, stabbed – a blow that really hit the mark (kairian)

Chorus (separate voices): -Sssh! Listen! Who is shouting they have taken a fatal

(kairios) wound?

Agamemnon: Ahh! No! Again! Hit a second time, a second stab –

Chorus: -That’s the king: the deed is already done, by the sound of it. We need to

work together to figure out (bouleumata) how best to protect ourselves.

-In my opinion we should send out a call to all the citizens to gather here now at the

house.

-No, at a time like this you have to act instantly – we might be able to catch them in

the act, bloody sword in hand –

-I agree, my vote (psephos) is that we do something. We can’t take our time when

something is happening right this minute, as we speak –

45 The pioneering Victorian producer of authentic Greek dramas, Fleeming Jenkin, for example, sees this as the moment where ‘drama’ triumphs over ‘lyric’: Colvin and Ewing 1887, 1, 17 (2011).

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

13

-We all know what’s happening: Aegisthus and Clytemnestra are seizing power in

typical tyrant fashion.

-Yes, because we are wasting our time discussing what to do! While we’re talking

they are acting to shatter our peaceful lives forever!

-Who can ever know what the right choice is (boulē)? Before you take any kind of

action you have to consider its advisability (bouleuesai).

-I agree – and you can’t plan to bring the dead back to life

-You should all be ashamed of yourselves – letting these usurpers destroy the royal

household because you are scared of getting hurt –

-Yes, death is nowhere near as bad as tyranny. I’d rather die! Come on!

-Wait – the only evidence we have is we have heard shouting – how do we know

those sounds mean he was actually being murdered?

-Yes, we need to know exactly what we are talking about first. Guessing is not the

same as knowing for certain, as having the facts.

-I agree with what everyone has said – we need to slash through all this speculation

and know with razor-sharp accuracy (tranos eidenai, to know piercingly) exactly

what has happened to Agamemnon. (tetraino = to stab, pierce).

Clytemnestra: (coming out of the palace) I am not ashamed that I spoke exactly as

was fitting (kairōs) earlier, but now I am saying the opposite. How else are enemies

who are meant to be friends supposed to fight? I caught him in my net of words, and it

held him fast....46

In Athenian tragedy, a knife in flesh is still a debatable thing, however decisive its

consequences. Similarly, the incontrovertible fact of a dead body also does not

reliably ‘speak louder than words’: in Euripides’ Hippolytus, Theseus chooses not to

believe his son, who is telling the truth in words, over the clear ‘statement’ of the

dead body of Phaedra, his wife (who left a suicide note accusing Hippolytus). Later

normative definitions of ‘tragedy’ as concerned with violent narratives about

character and suffering miss this original crucial and characteristic interest in the

slipperiness of definitive meaning, contradiction, and multiple perspectives. Yet the

horribly extreme can be seen as precisely deriving from these agendas, as serving the

purpose of demonstrating that even in the most apparently one-sided situations, such

46 Aeschylus’ Agamemnon 1343-1371 (my translation).

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

14

as a mother killing her children, or a child his mother, there is always another point of

view: things are never single, simple, or ‘piercingly’ clear.

The afterlife of Athenian comedy foregrounded its function as reflecting, expressing

and contesting the highly specific historical conditions of Athenian demokratia. But

the subsequent fate of the entries in the tragic competition in Athens was quite

different. A request was made to the Archon in 456 B.C. for permission to reperform

Aeschylus’ Oresteia, two years after its victory in the dramatic competition, and to

commemorate Aeschylus’s death. Other important developments followed, as

inscriptions from the 440s suggest: the introduction of an actor prize in 444 B.C., (as

what is expected becomes established, how it is performed becomes a focus of

interest): the establishment of the additional Lenaia festival in the 440s B.C. as an

opportunity for the performance of dramas specifically, suggesting they had become

recognised as a discrete art form deserving of special focus; and the addition of the

writer’s name to that of the choregos or chorus leader as joint prize-winners. These

moves, and not only original performance, can be seen as originating moments for

what would later be called ‘Greek plays’.

Reperformance is a distinct gesture from the presentation of a self-declared original

work. It accelerates the solidification of generic expectations.47 It foregrounds the

recognisability of elements in the work, and becomes about who has that capacity to

recognize, or in Paul Connerton’s terms, ‘remember’.48 Text and performance have

long been seen in opposition to one another, which, as I suggested, reflects a

nineteenth-century modern dramatic frame through which we have become

accustomed to view Greek drama. A more meaningful opposition or distinction may

be deliberate reperformance versus original performance (i.e. about which

expectations are unclear or unknown). Texts and performances must be expected to

imaginatively participate in each other in various ways: it is the shift in the context of

collective expectations which marks a historic distinction between self-consciously

innovative works and the collusive pressure of prescription, whether this is expressed

in textual form or not. Texts do not determine, or even necessarily influence, the 47 The Lenaia festival in 442 B.C. which began as a festival specifically for drama, soon becoming a focus for comedies, allowing tragedy to take precedence at the increasingly internationally-attended Dionysia. 48 Connerton 2009.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

15

reason for, or the nature of, a reperformance: rather, the sine qua non of a

reperformed work is that it is recognizable by some social group or other: a

codification of expectations expressed by the concept of genre.

Nevertheless, while texts do not necessarily cause reperformance, they certainly help

make it available, and transportable. There is evidence that the written texts of

Athenian dramas, in the context of the popular dissemination of texts of other kinds

(e.g. philosophical treatises of the sophists), played a key role in their widespread

afterlife beyond Athens. The first surviving detailed reference to tragedies being in

wide circulation as texts is in Aristophanes’ Frogs (c. 405 B.C.) in which Dionysus

says reading the Andromeda in a boat (ie pointedly not sitting in a theatre with a lot of

other people on a festival day) caused a pang of desire for Euripides.49 When an

Athenian crew were captured attacking Syracuse in 407 B.C. they were allegedly

spared the death penalty because they could recite the Syracusans’ favourite passages

of Euripides.50

With reperformance, the ideological meanings of such repetition become inseparable

from the meaning of the work: theatre becomes about repeating the well-known thing,

a thing which has value because of who else knows it too. In the fourth century B.C.

the massive reperformance beyond Athens of a small handful of famous Athenian

dramatic texts (performed side by side with newly written works which have not

survived) offered a space in which diverse and geographically-scattered Greek-

speaking cities could establish a common cultural identity as Hellenes. This spread is

roughly coincident with the building of stone theatres (such as Epidaurus, for

example): in contrast, the seating for which, say, Aeschylus wrote his Oresteia in 458

B.C was banked wooden stands, probably in a rectilinear arrangement for ease of

temporary assembly and disassembly (we know the city made some of its costs back

by renting out the wooden stands for other festivals elsewhere). Later fourth-century

stone theatres were, in contrast, a year-round architectural symbol of the collective,

figuring the city as its population, or demos: shrewd politics, as the widespread

financing and building of stone theatres by non-democratic Hellenistic autocrats 49 Aristophanes’ Frogs 60-70. 50 Ruth Scodel sensibly argues that this wider literary spread, as well as posterity, was in the minds of the three tragedians when they wrote their festival competition texts, as was Athenian cultural hegemony: Scodel 2001.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

16

suggests. Stone theatre-building enabled autocratic authorities to appear to be people-

centered, while the specially-marked seats for priests and kings in the front rows

signal their additional function as representing the people’s relationship to power.

The Romans would increasingly formalise theatrical and later amphitheatrical seating

as a stratified microcosm of social relations.51 That this is not necessarily merely an

aspect of the structural function of the ancient theatre as ‘seating’ is important to note:

the Maya in Chicen Iza, for example, architecturally frame public space as highly

significant, but without emphasizing collectivity or participation as a factor.52 Texts

which were originally the expression of a particular and turbulent Athenian and

democratic moment, with civic stone theatre building became a vehicle for the

expression of the collective’s fixed ‘place’, in every sense. Unsurprisingly, this

widespread reperformance led to rapid professionalization, with actors soon becoming

celebrities53 and Hellenistic kings soon styling themselves as actors.54 It was in the

context of such a wider imperial geography that the heroic political narrative – the

story of the individual characters within the dramas – became the focus of these

increasingly familiar plays, rather than the choral, and quintessentially participatory

values of their performance. Stone theatres, in their fixed banked rows of

hemispherical seats, also offered ideal vantage points from which to appreciate the

‘stand and chant’ geometric choral arrangements which were the feature of later

fourth century reperformance, and in which unison was a primary visual and aural

goal: 55 this skill was now the wonder, or thing looked at (theama) – quite different

from the same twelve young men playing four different choruses to their friends and

families in a single tour-de-force marathon event, no doubt the centre of gossip while

in preparation for half the year.

When Aristotle attempts to describe ‘tragedy’ in the Poetics (no longer, by 333 B.C.

‘Athenian’ tragedy) it is this phenomenon of widespread and selective reperformance

which he is addressing, for his audience of non-democratic and non-Athenian patrons

51 Beacham 1991; for Roman audiences see Bartsch 1994; for an excellent sociological analysis of the Roman arena in particular, Fagan 2011. 52 John Powell, Yale Council of Archaeological Studies: lecture at QMUL, Dec 3, 2011. 53 Hall and Easterling 2002. 54 Spivey 1997: 305; Pollit 1986, passim. 55 As discussed by Demosthenes, and as later satirised by Woody Allen in his 1995 film Mighty Aphrodite. As Rush Rehm has pointed out, this later ideal of unison needs to be distinguished from original performances in Athens, which were part of a much ‘wider experiential schema’ of the festival as a whole, specific to that place and time: Rehm 2002: 13-19.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

17

and readers. To some extent it is therefore natural that he seeks generic definition and

explanation in the apolitical characteristics of the performative ‘object’ itself, as

precisely separated from (transcendent, and textual) its originating, and highly

historically-specific, political context. Hellenistic kings such as Alexander the Great,

to whom Aristotle was not only tutor, but owed his economic capacity to write the

Poetics in the first place, already understood themselves as ‘performing’ their lives as

actors, or characters from the imaginaries of epic and tragic texts. This, too, makes it

likely that Aristotle would look to narratives concerning individual actors for the

explanation of tragedy’s appeal. Edith Hall has pointed out the markedly apolitical

nature of Aristotle’s explanations for what is by his time a ‘Greek’ tragedy, noting

that he positions audience reaction as central (catharsis etc) yet nowhere mentions the

polis.56 But we might question the extent to which Aristotle would have felt himself

able, in such a context (however liberal his patronage by Alexander) to suggest that

the qualities of tragedy were a positive expression of Athenian democracy, or that

Athenian drama was characteristically interested in raising questions about the

difficulties of right-ruling; or in that its central figures were models not only of flawed

characters, but flawed leaders. At the same time, he was writing in the context of

intense philosophical interest in the idea of explanation itself: so some or other

explanation was indicated. This, and the fact that his parallel discussion of comedy

did not survive, have helped direct attention towards what the individuals in these

works do, and what happens to them. Later readings of Aristotle through this lens

have taken tragic texts even further away from their original problematizing of truth,

speech and persuasion in a participatory context (often ignoring the passages where

Aristotle describes tragedy as originating from choral dancing) to position Aristotle’s

views as defining not only tragedy, but theatre and even narrative itself (cf. his use in

the Hollywood film industry). These readings led to a circular reading of tragic texts -

precisely out of context - as primarily concerning the fate and suffering of individuals,

and emblematic of human universals. This in turn helped prompt a vision of theatre

itself as the contents of its narratives, with heroic ‘actors’ (in both senses) at the

centre. It is the difficult decision-making of these individuals which henceforth gains

attention, rather than that of the audience-performer community. Thus, in so far as a

Western theatre tradition can be seen as having significant roots in Athenian

56 Hall 1998.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

18

democratic drama, these roots meaningfully belong less to fifth-century democratic

Athens, than to this later fourth-century period of crystallization, via reperformance

and textual reception, which shifts theatre’s origins away from being quintessentially

an exercise in political self-awareness, towards anodyne escape via the imagined

pathos (or in late nineteenth-century terminology, ‘psychology’) of an-other.

Unsurprisingly, those Athenian tragic texts or their elements which do not fit this

generic model, such as Euripides Ion, or Helen, are either ignored or adapted to

conform to this expectation. As Rush Rehm says, Euripides Ion, for example, is not

‘tragic’ at all in the popular sense of the word.57 With Aristotle, suffering and horror

became tragedy’s identifying characteristics. But they were also the characteristics

which popular reperformance gradually selected. The thirty-three play texts which

survive (of the thousand or so performed in the fifth-century) were not necessarily the

original Athenian competition winners, but the plays which actors and audiences

chose to reperform in the next century.58 (Sophocles’ Oedipus did not win, for

example: nor did Euripides’ Medea). The elements of these particular reperformed

dramas therefore were the ones which came to also feature strongly in the culture

Rome adopted as its Mediterranean multi-lingual patrimony, 59 especially after Greek

texts (in particular, Homer and the three tragedians, once canonized 60) became the

substance of an ancient Mediterranean education. Once established, any such

‘popularity’ is to some extent self-generating, for reasons not entirely to do with the

internal characteristics of the plays themselves; in Roman reworkings of Greek

culture, the very familiarity of a traditional Medea, Hercules, or Orestes, for example,

becomes an opportunity to make new kinds of meanings. Situations and characters

which aroused the strongest feelings, or which become focused into key moments of

decision, and which offered actors the most dramatic potential appear (for

understandable reasons) to have been consistently preferred; but these are quite

distinct pleasures from the provocative suggestion that even in the case of an extreme

action like Medea killing her children, there is always another point of view.

57 Rehm 2004. 58 They were eventually ordered to be written down in order to stem the process of actor revision: Easterling 1997; Easterling and Hall 2002. 59 Easterling 1997; see also Macdonald and Walton 2007. 60 Yunis (ed) 2003; Hall and Easterling 2002.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

19

In the modern period, when choral drama is read (partly through Aristotle) as

narrative, the chorus is seen as another a character in the action, a confidante, Master

of Ceremonies, or punctuating interlude. When choral drama is read as philosophy,

the chorus is seen conceptually as a commentator on events. These visions of Greek

tragedy are themselves also both deeply influenced by Roman precedents. Seneca, a

Roman writer in the court of Nero (4. B.C. – 65 A.D) played a key role in establishing

later ideas of tragedy as the locus of the humanly terrible: in his form of poetic

physical theatre the chorus disappears. Seneca’s tragedies do not dramatise

persuasion, or put in question the audience’s capacity to judge, but rather explore the

metaphoric potentials of quintessentially familiar material.61 Although Seneca can be

seen as inspiring later graphic displays of violence, from Shakespeare’s Macbeth to

Sara Kane’s Phaedra, his own violence remained located in his poetry, as Helen

Slaney suggests:

‘the cruelty generally remains inside [Senecan] discourse and is not

represented on stage: and the chorus provides a moral, political or didactic

interpretation of the offstage atrocities.’62

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as Joshua Billings has pointed out,

Aristotle’s discussion of tragedy (especially of Poetics 7.1) which was written as a

prescriptive recommendation for what then appeared to work best, was read as

descriptive of the tragic texts which survive:

‘Modern understanding of the tragic chorus primarily as a participant in the

action of tragedy - Aristotle and Horace’s normative prescription [that] the

chorus should be integrated into the plot - was (mis)understood as a

descriptive judgment on the role of the chorus in tragedy - [i.e. that it is]

fundamentally part of the action.’63

Billings argues that this change, as explored by German romantic writers and

philosophers, was key in effecting a shift from seeing ‘chorality’ to seeing choruses. 61 For the argument about whether Seneca’s poetic texts were performed or not, see now Slaney (forthcoming). 62 Slaney 2013. 63 Billings 2013.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

20

From the early nineteenth-century onwards, as a modern concept of text-based

‘tragedy’ gained ground, the chorus became seen as a problem for the performance of

Greek drama. It is no coincidence that the revisioning of theatre in the 1960s as

essentially about the collective has led to a modern revival of interest in Greek drama.

Edith Hall says there have been more productions of ‘Greek plays’ since the 1960s

than in their entire history since their first performance in the fifth century B.C.,

including in antiquity itself.64 As Peter Meineck and Helen Eastman have separately

noted (both are theatre practitioners as well as scholars) an increase in non-text-based

ensemble practices, and the re-prioritising of audiences and self-referentiality, has

coincided with (choral) Greek drama moving from being seen as a problem for

performance, to being seen as about performance itself.65

Ancient reperformance and Aristotle, then, played key roles in the reification of

Greek drama: but current perceptions of both also significantly reflect their discussion

in the academy after the advent of modern drama. What follows stresses the

importance of the historical moment when the scientific method, and its progressive

potentials as expressed by the modern university, helped narrow ancient ideas of a

transcendent and paradoxical chorality to the confines of a specific text or occasion.

In so doing, it located the idea of theatre itself in the textual or performative object,

rather than a public’s capacity to recognize – and especially, to recognize itself. It

was precisely because theatre had previously been understood as a function of

audiences that the first so-called ‘archaeological’ productions of Greek plays in Greek

in Britain (using the authentic historic texts) caused the sensation they did. Their

power to be effective, apparently objectively unchanged, across vast gulfs of cultural

and temporal difference was the declared scientific discovery: one which caused

national headlines and a ‘scrimmage’ for tickets.66 This coincided with a growing

interest (in novels, as well as plays) in psychology and character as human universals.

64 A claim which is hard to verify, as it depends on record keeping. But it marks a desire to emphasise the relevance and importance of what Hall sees as a meaningfully continuous performance history of ‘Greek drama’ to the present: a continuity which this chapter puts into question. 65 Eastman 2013; for excellent recent case studies of productions in the USA, Meineck 2013. For an introduction to productions of Greek drama since Schechner and the 1960s, see Hall, Macintosh and Wrigley 2004. 66 The Academy, Dec 8, 1883.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

21

‘Theatre’ versus ‘drama’

In Britain, a touring performance of Frank Benson’s 1880 Oxford Agamemnon, at St

George’s Hall, London,67 a venue associated with the performance of classical music

and the spoken word, was hailed as the first performance in Britain of an authentic

text of Greek drama; it followed by a few months William Poel’s performance of the

First Folio version of Hamlet,68 also hailed as the first authentic public performance

of Shakespeare’s actual text since his own day.69 Poel and Benson soon afterwards

worked together: Poel was hired as Stage Manager for the F.R. Benson Company in

1884, and was involved with the Orestean Trilogy world tour. The idea of such

touring productions and ‘black box’ theatre (ie non-spectacular, and without elaborate

fixed sets) evolved together with a new respect for the dramatic text. Poel and Benson

shared an interest in the authentic historic performance text, and saw their challenge

as making it work dramatically in its unadulterated form: at the time, a novel idea.70 A

community of progressive artistic innovators – e.g. Benson, Poel, Lewis Campbell,

Gilbert Murray, Benjamin Jowett - were involved in archaeological (or authentic)

productions of both Shakespeare and Greek plays. Such early respect for the text,

once established, offered a space of appreciation in which new literary dramatists like

Ibsen and Shaw could find receptivity. Henry James, H.G. Wells and Joseph Conrad

would all experiment with writing plays in the same spirit as they experimented with

new forms of the novel, and film. Gail Marshall, discussing this general

transformation of the concept of theatre not just in Britain but also in the United

States, notes how the two words ‘theatre’ and ‘drama’ became opposed during the

1880s and 1890s:

‘The conflict between old and new was part of a broader debate at this time, as

Henry Arthur Jones notes, between the “theatre and the drama”, between the

attractions and commercial requisites of the spectacle, and the interests of the

literary.’71

67 Dec 16-18, 1881. 68 April 16, 1881. For this production see Lundstrom 1984: 14-16, 17-32. 69 For Poel’s significance in context, see Chothia 1996: 233-‐34; Dobson 2011: 65-‐108. 70 As Shaw said: 1948. 71 Marshall 1998: 136. ‘Literary’, according to Marshall, was an adjective specifically associated with the innovative work of Henrick Ibsen, promoted by Edmund Gosse (Gosse 1872). Archer’s translations

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

22

Henry James, for whom ‘the acted play was a novel intensified’72 notoriously

struggled with the separation:

‘The whole odiousness of the thing lies in the connection between the drama

and theatre. The one is admirable in its interest and difficulty; the other

loathsome in its conditions.’73

The historic texts of Greek drama and Shakespeare played a central role in laying the

foundations for the emergence of this new idea of theatre precisely because they were

already well-known, and respected, in non-performance contexts: especially, in

education. These so-called ‘archaeological’ performances attracted the attention of a

wider progressive artistic community, including novelists, painters, musicians and

designers, as well as theatre-makers (eg Henry James, Oscar Wilde, Gordon Craig and

father Edward Godwin, Frederick Leighton, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, William

Archer, Granville Barker and George Bernard Shaw) many of whom would go on to

become centrally associated with both modern drama (or new drama, or the just ‘the

drama’) and the movement for a serious national theatre.74 The founding of the

Oxford University Dramatic Society (OUDS) by Benjamin Jowett in 1883 was in

pursuit of establishing such a new ‘serious’ and text-based theatre. Jowett’s decision

to found the OUDS not as a dining or college society, but as a pan-university

organization, with the presidents of other clubs and societies invited to sit on its board

(the Vincents, Bullingdon, Boating, Football, Cricket, etc) itself suggested that this

new ‘drama’ was not, as earlier amateur dramatics had been, a membership-driven

social club, but of universal appeal, implicitly of interest to all.75 Where in 1880

Jowett had been against the touring of Benson’s Agamemnon to London, he actively

encouraged the OUDS production of The Merchant of Venice in 1883 - described as

‘Shakespeare more intelligibly and intelligently performed than it can ever hope to be

under any other conditions’ - to tour to the Vaudeville Theatre in London and to

(Pillars of Society in 1880, Doll’s House in 1889, and Ghosts in 1891) launched a wave of ‘Ibsenism’: Chothia 1996: 25. 72 Chothia 1996: 181. 73 Henry James Letters, Vol III: 452: in Marshall 1998: 136. 74 On theatre and nation, including as a modernist reaction to industrialisation, see now the introduction by Holdsworth 2010. William Poel called for a reconstructed Globe theatre as early as 1900. 75 ‘The Shooting Stars’ had unusually been a university-wide organisation, which made the Boulton and Park scandal all the more serious; Adderley’s ‘Philothespians’ had been a Christ’s College Dining Club.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

23

Stratford-upon-Avon, suggesting that by then, he saw his role in founding the OUDS

as an opportunity to use an Oxford and academic context to influence attitudes to

theatre nationally, towards precisely interest in, and respect for, the text. Oscar Wilde

was called back to Oxford in the mid-1880s to review OUDS productions in an effort

to drum up interest for the new society, which in its first decade, struggled to find a

student audience and public approval:

‘I know that there are many who consider that Shakespeare is more for the

study than the stage. With this view I do not for a moment agree…

Shakespeare wrote his plays to be acted, and we have no right to alter the form

which he himself selected for the full expression of his work... Why should

not degrees be granted for good acting? Are they not given to those who

misunderstand Plato and mistranslate Aristotle?...76

In Wilde’s favorable comparison of the good actor with the bad classical scholar he

unmistakably identifies a concept of acting as an interpretation of a text. The actual

words of the text are seen as autonomous and objective, a provocation to

understanding (‘misunderstand...mistranslate’). But it was not only the discovery of

the affective potential of the actual words of the text which were ‘revolutionising’

theatre, as the press declared, but the idea of authentic visuals, too. Wilde continues:

...’Even the dresses had their dramatic value. Their archeological accuracy

gave us, immediately on the rise of the curtain, a perfect picture of the

time….the fifteenth century in all the dignity and grace of its apparel was

living actually before us…[and added to the] intellectual realism of

archaeology [was] the sensuous charm of art.’

What was new about these authentic performances was an imaginative engagement

with the idea of the performative historical object, whether embodied in words,

costume, set or sound. This shift of focus from audiences to the object on stage

effected by these ‘archaeological’ plays helped pave the way for modern drama. That

76 Dramatic Review, May 23 1885. Irving would make the same point in Oxford ten years later (Richards, 1994) suggesting that the opinion that Shakespeare should only be read was well established.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

24

theatre, until this point, had been understood as the assembly of some or other

audience, was one reason the dramatic potential of the verbatim texts of Greek drama

outside of their original audience context was a surprise. Before then, plays may have

been engagements with familiar texts, but these were precisely adapted to their

present audiences. R.C. Jebb, writing in 1883, explained that the performance of

authentic Greek plays had never been attempted before because it was always

assumed they would be intelligible only to an Athenian audience. The assumption had

been that ‘a successful Sophocles presupposed a Periclean Athens;’77 or as The Times

put it, ‘no one could expect or require that a play of Sophocles should evoke

excitement from a modern audience’.78 These archaeological plays surprised everyone

by suggesting, if well interpreted by their performers, this was not the case. They

appeared to prove that the object contained its own mysterious power to affect.

Before modern drama, Britain’s multifarious theatrical culture included burlesques,

extravaganzas, amateur theatricals, musical entertainments and tableaux vivants.

Henry Irving had done much to increase the respectability of theatre in the 1870s and

80s, but his Shakespearean productions (for which the famous painters of the

illusionistic backdrops received central billing in programmes) were ‘visuality at its

height’:79 as Jaqueline Bratton puts it, ‘scenic illusion then defined “what was a

play”’.80 But this does not mean that the conditions of viewing which we assume

today for static paintings and other forms of two-dimensional art necessarily operated.

Richard Schechner rightly marks the incompatibility of the proscenium arch with

Greek drama, which, like Shakespeare, figures audience presence in its dramatic

dynamics;81 but it is not illusionism or two-dimensionality as such which occludes

awareness of audience. Indeed, before the shift of focus to the object on stage

coincident with modern drama, that the focus of attention is not the stage – however

thrillingly visual - is often emphasised. It is dramatized, for example, by Degas’ 1876

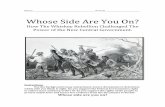

painting of the revival of the early ‘ballet’ Robert le Diable (Fig. 1):

77 Jebb 1883. 78 The Times, Nov 28, 1882. 79 Chouhan 2012. 80 Bratton, 2007: 253. 81 In an interview with Peter Meineck: Meineck 2013a: 2-11 (p. 11).

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

25

Fig. 1. The Ballet Scene from Meyerbeer's Opera Robert Le Diable, by Edgar

Degas.

In Degas’ 1876 painting the marked inattention of the audience to the focal point of

the stage, despite its luminescence, is vividly conveyed by the criss-crossing lines of

sight, echoed by the diagonals of the bassoons. Depictions of theatre in nineteenth-

century fiction, from Austen to Wharton, similarly feature a theatre gaze ‘directed at

the auditorium’.82

The priority of audience presence is expressed architecturally by Victorian theatres

built before the mid-1880s, in which the auditorium was typically as brightly lit as the

stage, with the boxes often facing directly away from the stage, and side seats facing

each other. When such eighteenth- and nineteenth-century theatres were built, 82 Chothia 1996: 180.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

26

performers and audience were equally lit, and visible to each other. Many such

theatres still in use today across Britain have become naturalised as a home for

serious literary drama; but few would deny they are poorly suited for such

experiences.83 Seats often have a restricted view of the stage, or a better view of the

other seats than of the stage: seeing and hearing subtle performance - facial and vocal

expression, looks, hesitation - from a distance can be a struggle. But it is not only, as

might first appear, that dancing or singing gave the shape of these stages their logic: it

is also that theatres themselves conceived of their ‘stage’ as including the

auditorium.84 The fact that the auditorium had been experimentally darkened by

Wagner as early as 1857, in pursuit of precisely the kind of private emotional

immersion which would later prevail, but did not immediately catch on, underscores

that a dark house was by no means an immediately obvious idea. Not only was it felt

unsafe, but it meant the audience could not see each other: and since antiquity, at the

heart of the pleasure of a public theatre was as much the drama of collectively being

seen, as of seeing. Auditorium and stage were a shared space, the audience fellow

performers, the watchers watched watching.85

These theatrical forms themselves hark back to antiquity. With the shift from Greek

circular cavea to the Roman horseshoe, side seats became fully perpendicular in

relation to the scaenae frons, and directly faced each other, rather than the stage.86 In

the sixteenth century the sharpness of this Roman horseshoe curve posed a problem to

Renaissance artists excited to recreate Roman scenographic perspective effects, after

the rediscovery of Vitruvius.87 They were stumped by the contradiction between the

needs of perspectival illusion and the Vitruvian theatre’s U-shape, which

emblematized collective presence as itself the important sight.88 Permanent theatre

buildings still demonstrated these contradictory priorities as late as 1884, when the

Old Vic was rebuilt with its ‘stage boxes’ actually facing away from the stage.

83 Although, correspondingly, they are good for musicals, where recognition and audience presence plays a role. 84 Electric lights were in use from the 1850s onwards but imitated the function of gas or limelights, or created special effects. 85 Cf. Ovid Ars Amatoria I, l.99: spectatum veniunt, veniunt spectentur ut ipsae (here, the cultissima femina of Rome). 86 Exemplified by the contrast between the theatres of Dionysus and of Herodes Atticus on the same slope of the Athenian Acropolis today. 87 Beacham 1991. 88 Vince 1984: 12. Discussion in Beacham 1991: 203-211.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

27

‘Drama’, involving relationships revealed by scripted dialogue between characters on

a stage which we are expected to analyze and interpret in terms of psychology and

emotion, ourselves hidden in darkness (or at least, in a conceptual collective

‘privacy’) emerged in the late 1880s and early 1890s. In 1887, seven years after

Benson and Poel’s first experimental ‘archaeological’ production of Aeschylus’

Agamemnon, André Antoine opened his Theatre Libre in Paris, said to have inspired

Strindberg’s Intimate Theatre in Stockholm and Barker and Vedrenne’s Court Theatre

in London (later, the Royal Court). Antoine pioneered the use of overhead lighting,

intimate spaces (so the actors’ faces could be seen, and hushed ‘realistic’ delivery

heard)89 and controversially positioned actors, including himself, with their backs to

the audience.90 He also notably staged plays with unprecedented respect for the

authority and integrity of their verbatim texts, often liaising with the play’s original

authors (eg Tolstoy, Hauptmann) over the details of the translation. Antoine went on

to perform the first complete texts of Shakespeare in France (e.g. with the Fool

restored to Lear, and the Gravediggers to Hamlet).91

Zoe Svendsen describes the advent of modern drama as the essence of audience

experience moving from being about social and political identity, to being about

psychological analysis and prediction.. Jean Chothia describes the change as a move

from the key relationship being between characters and the audience, to being

between characters on stage. She emphasizes its coincidence with the evolution of

effective stage lighting, and the darkening of the auditorium, i.e. with the ‘fourth

wall’, a term coined in connection with Antoine’s productions.92 As Chothia says:

‘No longer the acknowledged core of the action, the audience experiences the illusion

of looking in on another real, self-centered world... 93 [They become] passive

onlookers, and Bottom and Macbeth’s Porter [are now] characters, not

89 Blackadder 2003: 17-39. 90 Chothia 1991: xvii, 15-16, 20-37: ‘The Fourth Wall’, and 1996: 178-203 Ch. 7,‘Literary Drama’. 91 Chothia 1991: 9, 80-111 Ch. 5, ‘A Playwright’s Theatre’. Both Antoine and Frank Benson were influenced by the Saxe-Meinigen company, with their simple sets and realistic crowd scenes, as well as by the Comedie Francaise 1881 production of Oedipe Roi, with Mounet-Sulley. For earlier German attempts to privilege the texts of Shakespeare, see Williams 1986: 210-221. 92 As well as the changes in the social make-up of the audience which made such darkening safe. 93 Chothia 1991: 24-25.

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

28

comedians....’94 The complex metaphorical relationship between real world and the

world of the play is lost as theatre changes ‘from playing to, to playing for, an

audience...departing from the practice of centuries to establish the dominant

twentieth-century mode’.95

In Wilde’s 1895 The Importance of Being Earnest, for example, as in farce in general,

the audience is told, and knows all along, what is to be revealed (that Jack is not

Earnest, and was found); and as in its ancient Sophoclean model Oedipus Tyrranus

(in contrast to whose tragic stakes it achieves a ribald frisson) a central pleasure lies in

the collective anticipation of its inevitable revelation, in the collusion of

‘knowingness’ itself. The objectification of the show on stage made possible the

disappearance of this idea of ‘knowing’ collusion with an audience. British director

Carl Heap, who specialises in the performance of Medieval Mystery plays, defines

modern drama as ‘not letting the audience see through the cracks’.96 Director Katie

Mitchell, who in her approach claims a line of descent going back directly to

Stanislavsky, famously trains her actors never to think of the audience.97 In the works

of Ibsen, Strindberg, or Chekhov, broadly contemporaneous with Wilde’s theatrical

satires, we learn what is significant at the same time as the characters, and our

prediction of (or surprise at) events is in accordance (or not) with our own assessment

of their psychology. The 1895 drawing rooms of Ibsen and Wilde, then, mark the cusp

between two very different types of theatre. The idea the actors must pretend the

audience are not looking is a different kind of pleasure than the acknowledged and

inclusive reciprocity between performers and audience such as we find in the delivery

of Oscar Wilde’s one-liners, or in his theatrical antecedents in farce, Restoration

Comedy, Roman comedy, or indeed, Athenian tragedy.98 These earlier ‘theatres’ were

94 To restore this relationship to audience is one of the impacts of the reconstructed Globe, and a goal of practitioners like Mark Rylance (e.g. Taming of the Shrew, 2013; or Twelfth Night in which Olivia is played by him). 95 Chothia 1991:29. 96 He says the best illustration of ‘modern drama’ is its parody in Michael Greene’s Coarse Acting (rev. 1994), offering the example of an Edinburgh festival production based on Greene’s book, in which four people sat round a table whose legs had fallen off so it was propped up by their laps, and when the doorbell rang, rather than move, they improvised conversation to explain why they were choosing not to answer. 97 Mitchell 2010. 98 Mike Leigh, in his recent play Grief (National Theatre UK, 2012) explores the links between this idea of psychologically realistic ‘acting’ which we are invited to judge or interpret, and the repressions of the bourgeois culture with which its consumption, as ‘drawing room’ drama, became associated. Its damning climax is a moment of inaction, where the uncle, in response to the screams of his sister

Ancient Chorality versus Modern Drama Clare Foster

29

organised around the pleasures of a precisely common recognizand. Collective

recognition was also the dynamic behind tableaux vivants, which for Catharine Hail,

head of the V & A theatre collection, epitomise the nineteenth-century. Theatre would

still be - and to some extent always must be - about audience and audiences after this

change: but as Susan Bennett has argued, the identity of theatre with audience, and

thus its inherently public significance, would recede in favour of analysis and

interpretation of the objective presentation.99 Strindberg’s famous call for change in

his preface to Miss Julie captures the change of focus in which these then theatrical

pioneers were engaged:

‘I have few illusions of being able to persuade the actor to play to the audience

and not with them…I do not dream that I shall ever see the full back of an

actor throughout the whole of an important scene, but I do fervently wish that

vital scenes should not be played opposite the prompters box as though they

were duets milking applause. …if we could get rid of the side-boxes (my

particular bête noire) with their tittering diners and ladies nibbling at cold