Wages of Whiteness & Racist Symbolic Capital (ed. Wulf D. Hund, Jeremy Krikler, David Roediger)

-

Upload

uni-hamburg -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Wages of Whiteness & Racist Symbolic Capital (ed. Wulf D. Hund, Jeremy Krikler, David Roediger)

Wages of Whiteness&

Racist Symbolic Capitaledited by

Wulf D. Hund, Jeremy Krikler,David Roediger

LIT

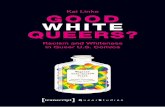

Cover: Wulf D. Hund and Stefanie Affeldtusing a collage of a trimmed photograph by Margaret Bourke-White

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche NationalbibliothekThe Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the DeutscheNationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet athttp://dnb.d-nb.de.

ISBN 978-3-643-10949-1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

©LIT VERLAG Dr. W. Hopf Berlin 2010Fresnostr. 2 D-48159 MünsterTel. +49 (0) 2 51-620 320 Fax +49 (0) 2 51-922 60 99e-Mail: [email protected] http://www.lit-verlag.de

Distribution:

In Germany: LIT Verlag Fresnostr. 2, D-48159 MünsterTel. +49 (0) 2 51-620 32 22, Fax +49 (0) 2 51-922 60 99, e-mail: [email protected]

In Austria: Medienlogistik Pichler-ÖBZ, e-mail: [email protected]

In Switzerland: B + M Buch- und Medienvertrieb, e-mail: [email protected]

In the UK: Global Book Marketing, e-mail: [email protected]

In North America by:

Transaction PublishersRutgers University35 Berrue CirclePiscataway, NJ 08854

Phone: +1 (732) 445 - 2280Fax: + 1 (732) 445 - 3138for orders (U. S. only):toll free (888) 999 - 6778e-mail: [email protected]

Contents

Editorial 1

EXPOSÉS

Accounting for the Wages of Whiteness 9U.S. Marxism and the Critical History of RaceDavid Roediger

Racist Symbolic Capital 37A Bourdieuian Approach to the Analysis of RacismAnja Weiß

Negative Societalisation 57Racism and the Constitution of RaceWulf D. Hund

STUDIES

A Paroxysm of Whiteness 99›White‹ Labour, ›White‹ Nation and ›White‹ Sugar in AustraliaStefanie Affeldt

Re-thinking Race and Class in South Africa 133Some Ways ForwardJeremy Krikler

›A White Man’s Country‹? 161The Chinese Labour Controversy in the TransvaalDagmar Engelken

Racializing Transnationalism 195The Ford Motor Company and White Supremacyfrom Detroit to South AfricaElizabeth Esch

Editorial

When in 1937 the Ohio River burst its banks, it wrought havoc, claimedalmost four hundred lives, and rendered about a million people home-less. Like Hurricane Katrina more recently, the disaster exposed acuteracial and class divisions. They were captured in one of the most famousphotographs of Margaret Bourke-White, ›At the Time of the LouisvilleFlood‹. Reproduced on the cover of this Yearbook, it shows victims ofthe catastrophe awaiting the distribution of relief supplies. The people inneed queuing up with their empty buckets, baskets and bags in front of thehuge billboard advertising the American way of life have been describedmany times, and the contrasts of the picture have been emphasised.1 Cen-tral to them is the hierarchical arrangement of needy blacks and wealthywhites.

It is obvious that the impoverished black victims of the flood couldnot have identified with the prosperous, white middle-class family por-trayed on the billboard. But how would that family have been viewed bya white worker from Louisville who had lost his job in the Depression,sold his car, and then suffered the catastrophe of the flood? For him, thebillboard might have appeared to mock his position: jobless, carless, con-sumed by worry for his family. But it still held out a promise. If only thatworker had the money, he could join those portrayed on the poster. Theywere, after all, like himself, white. The ›American Way‹, the ›AmericanDream‹ seems open to one like himself who is counted as part of a whitecommunity that allows its marginalised members what William EdwardBurghardt Du Bois, two years before the flooding of the Ohio, called »asort of public and psychological wage«.2

1 Many of these contrasts are enumerated in John A. Walker, Sarah Chaplin: VisualCulture: an Introduction. Manchester etc.: Manchester University Press 1997, p. 124:»blacks / whites, individuals / family, poor / affluent, passive / active, careworn / care-free, pedestrians / car owners, facing to the side / facing to the front, below / above,documentary-genre photo / advertising genre photo«.

2 William Edward Burghardt Du Bois: Black Reconstruction. An Essay Toward a His-tory of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy inAmerica, 1860-1880. New York: World Publishing 1964 (1. ed. New York: Harcourt,Brace and Co. 1935), p. 700.

2 Editorial

Such gratification is identified (by David Roediger) as an element ofthe ›wages of whiteness‹, that »could be used to make up for alienat-ing and exploitative class relationships«. It would in this way contributeto the »construction of identity through otherness«. According to it, anegative element would be adopted in the formation of the identity of›white‹ lower classes that was conceived (by Jeremy Krikler) as a para-dox: »What made the white proletarians what they were was that whichthey were not«. The associated »inclusion by exclusion« is characterized(by Wulf D. Hund) as »negative societalisation«. »Societies shaped bydominance« do »not solely cohere by their own culture and tradition«,but also by depreciating the culture and tradition of the others.3

At the time of the Louisville flood, such ideas were already beinggiven theoretical voice. Max Weber conceptualised it through his notionof »ethnic honour« and pointed to the poor whites in the South of theUnited States as exemplifying it. Their »social ›honour‹« was called a»purely negative« relation, because it was »fully dependent on the socialdegradation of blacks«. Sigmund Freud, meanwhile, spoke of an »autho-risation to despise outsiders«. He reckoned that it was indispensable forclass societies, because it »recompensed« the »oppressed« for »restric-tions in their own circle«.4

For Du Bois, this dimension of racism was only one element of white-ness as a whole social complex. Most of all, whiteness for him was linkedto the chance of material gratification. He answered the question »whaton earth is whiteness that one should so desire it« by referring to the »ex-ploitation of darker peoples«, which had diverse beneficiaries – »not only[. . . ] the very rich, but [. . . ] the middle class and [. . . ] the laborers«.5

Because of this, the compensation granted by the wages of white-ness is not merely a sedative; it is accompanied by the right of ac-

3 Cf. David Roediger: Wages of Whiteness. Race and the Making of the American Work-ing Class. Rev. ed. London etc.: Verso 1999, p. 13 f.; Jeremy Krikler: White Rising. The1922 Insurrection and Racial Killing in South Africa. Manchester: Manchester Univer-sity Press 2005, p. 149; Wulf D. Hund: Negative Vergesellschaftung. Dimensionen derRassismusanalyse. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot 2006, p. 123 (quotation trans-lated).

4 Max Weber: Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Grundriß der verstehenden Soziologie, ed. byJohannes Winckelmann. Köln etc.: Kiepenheuer und Witsch 1964, pp. 303, 309; Sig-mund Freud: Die Zukunft einer Illusion. In: id., Fragen der Gesellschaft. Ursprüngeder Religion. Sigmund Freud Studienausgabe, ed. by Alexander Mitscherlich, AngelaRichards, James Strachey, vol. 9. Frankfurt: Fischer 1974, pp. 135-189, p. 147 (quota-tions translated).

5 William Edward Burghardt Du Bois: The Souls of White Folk. In: id., Darkwater.Voices from Within the Veil. New York: Schocken 1969 (1. ed. New York: Harcourt,Brace and Howe 1920), pp. 29-52, pp. 30, 43.

Editorial 3

cess to the benefits of white supremacy. Using the USA as an example,Charles W. Mills explained its complex structure, referring to somatic,metaphysical, epistemological, cultural, political and economic factors.Economically, white wealth had been extracted from red soil by blacklabour through »racial exploitation«. Politically, this had welded the dif-ferent social groups of ›whites‹ to one »ruling race«. Culturally, all ele-ments of civilisation had undergone systematic »bleaching«. Epistemo-logically, a »white normativity« had thus established itself. Metaphysi-cally, this made possible the separation of »white Herrenvolk« and »non-white, particularly black, Untermenschen«. Somatically, nonwhite bodieswere thereby subjected to »racial embodiment and alienation«.6

The advantages resulting from such relations benefited even poorwhites in manifold ways. They not only promised an ideological dividendfrom whiteness, but also allowed access to education, jobs, residentialproperty, health care, entertainment and, of course, politics. Of particularinterest in this regard, is Anja Weiß’s extension and adaptation of PierreBourdieu’s notion of symbolic capital so that it is applicable to racist dis-crimination in general and race societies in particular: »Racialized sym-bolic capital is an asymmetrically distributed resource with considerableinfluence on the life chances of its owners«.7 The symbolic capital con-veyed by ›whiteness‹ combines psychological with material elements. Onthe one hand, it offers an authorization to ostracize others. On the otherhand, it enables a share of societal wealth.8

Finally, somatic whiteness finds habitual expression in a normativebody consciousness. Its role models can be traced far back. They werefor centuries propagated as aesthetic norm and eventually sanctionedthrough the methods of scientific racism. The ›average American girland boy‹ were already purely white at the World’s Columbian Exposi-tion in Chicago in 1893. Shortly after the Ohio flood, when they werenamed ›Normman‹ and ›Norma‹ in 1939 at the New York World’s Fair,their statues had not in the least changed. Eventually, they were projectedby the USA into outer space. The plates mounted on the ›Pioneer‹ space-crafts ten and eleven depict as the representatives of the earth’s population

6 Charles W. Mills: White Supremacy as Sociopolitical System: A Philosophical Perspec-tive. In: White Out. The Continuing Significance of Racism, ed. by Ashley W. Doane,Eduardo Bonilla-Silva. New York etc.: Routledge 2003, pp. 35-48, pp. 40 ff.

7 Anja Weiß: The Racism of Globalization. In: The Globalization of Racism, ed. byDonaldo Macedo, Panayota Gounari. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers 2006, pp. 128-147,p. 133.

8 Cf. Charles W. Mills: Racial Exploitation and the Wages of Whiteness. In: What WhiteLooks Like. African-American Philosophers on the Whiteness Question, ed. by GeorgeYancy. New York etc.: Routledge 2004, pp. 25-54.

4 Editorial

a white couple conforming to traditional gender roles. To this very daythey continue to traverse the universe and we can only hope that they willnot fall into the hands of any halfway intelligent extraterrestrial species.9

The essays assembled in this volume shed light on the complexworlds of racism and whiteness with various examples from differingperspectives.

David Roediger (University of Illinois) preliminarily addresses theevolution of whiteness as a category of critical social analysis. He devel-ops a corrective to the assumption that the critical study of whiteness wasat the core a post-modern project. He does so by emphasizing the placein the 1990s of Marxist and Marxist-inspired studies in the emergenceof such scholarship in the US, especially in the field of history where aheterodox group of scholars and activists came to regard whiteness asa problem and made it an urgent object of inquiry. On this view, eventhe influence of psychoanalysis as a tool in the study of white identity,advantage and practice emerged from debates within the left.

Anja Weiß (Universität Duisburg-Essen) subsequently explains thatthe perspective of whiteness studies can be expanded by a modificationof Bourdieu’s category of symbolic capital. She starts from a distinc-tion between economic and cultural capital and adds reflections regardingsymbolic power. From there she develops an enhanced multi-dimensionalmodel of social disparity. It integrates racism as a form of symbolic dom-ination into the analysis of social structure. Racist symbolic capital is,in the course of this, understood as a collective resource which allowsprocesses of social inclusion or exclusion. Both processes are correlated.Racist symbolic capital is, therefore, not a ›property‹ but an expressionof contested social relations of inequality.

Wulf D. Hund (Universität Hamburg) pleads for the generalisation ofthis concept and for its application to an analysis of racism as negative so-cietalisation. He understands racist symbolic capital as a resource whichhas assumed historically diverse shapes. In his essay he begins by shininga light on several pre-modern patterns of racist discrimination which pro-ceeded without the category of race. Subsequently he discusses the emer-

9 Those responsible for this version of ›Normman‹ and ›Norma‹ were well aware ofthe racialized message and recorded: »it was not possible to avoid some racial stereo-types, but we hope that this man and woman will be considered representative of all ofmankind« (Carl Sagan, Linda Salzman Sagan, Frank Drake: A Message From Earth.In: Science, 175, 1972, 4024, pp. 881-884, p. 883); for the previous cf. Roberta J.Park: Physiology and Anatomy are Destiny?! Brains, Bodies and Exercise in Nine-teenth Century American Thought. In: Journal of Sport History, 18, 1991, 1, pp. 31-63,p. 57 (›1893‹) and Julian B. Carter: The Heart of Whiteness. Normal Sexuality and Racein America, 1880-1940. Durham etc.: Duke University Press 2007, p. 1 ff. (›1939‹).

Editorial 5

gence of the race stereotype and its ideological utilization in scientific asin popular pleas for the diminishing (or blanking out) of the potential forsocial conflict through outwards dissociation. The practical implementa-tion of this racist community building is explored through the examplesof the white Australia policy and German political antisemitism.

Stefanie Affeldt (Universität Hamburg) specifies the analytic dimen-sions of the categories ›racist symbolic capital‹ and ›wages of white-ness‹ using the example of the ›white sugar campaign‹ in Australia andits prologue. By analyzing the story of the physical, social and demo-graphical ›whitening‹ of the Queensland sugar industry she demonstratesthat whiteness as a social construction entailed continuous definition andredefinition. In particular in the early twentieth century the (re)drawingof boundaries of belonging alternately included and excluded groups ofimmigrants, while simultaneously the consumption of sugar became ameans of expressing loyalty to the Australian nation.

Jeremy Krikler (University of Essex) explores some missing dimen-sions in the study of race and class in South Africa. Warning of the dan-gers of too great an emphasis on class in exploring race, he neverthelessshows where socio-economic interests were vital in the development ofthe racial order in the country. He focuses particularly on master-servantrelations – which historians have tended to ignore – and reveals how theyhad the capacity to cut across classes amongst whites, since white work-ers frequently had black servants. The article is also concerned with iden-tifying how the politics of white supremacy, with its focus on racial de-mography, shaped South Africa’s economy, society and politics. Kriklercloses by proposing that much is to be gained by South African historiansadapting and utilizing Tim Mason’s famous ideas regarding the relation-ship of politics to the economy in Nazi Germany.

Dagmar Engelken (University of Essex) investigates the ChineseLabour Question in South Africa in the early-twentieth century and re-veals a most complex articulation of race and class. For the white work-ing class was far from united in its response to the recruitment of scoresof thousands of indentured Chinese workers for the South African goldmines. The trade unionists affected by the Australian experience stronglyopposed Chinese labour but they were unable to carry the rank and filemineworkers with them: a majority of those workers saw their own em-ployment opportunities dependent on the Chinese workers, the influx ofwhich they were prepared to support if these indentured workers weresegregated, prevented from competing with white workers in designatedjobs, and provided their employment was ended once sufficient African

6 Editorial

labour was forthcoming. Engelken demonstrates how attitudes to the Chi-nese shifted, how these shifts were linked to the concerns of particularclasses (or groupings within them) and yet how the Chinese Labour Ques-tion nevertheless provided a cement for the bonding of political forcesamongst whites at a crucial time.

Elizabeth Esch (Columbia University) examines the ways in whichthe workplace and corporate initiatives beyond it imagined the assemblyline worker as a white citizen/consumer in linked but very different waysin the U.S. and South Africa between World War 1 and World War 2.Making the Ford Motor Company’s auto- and race-making activities inDetroit and in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, and the Carnegie Commis-sion inquiry into the ›poor white‹ problem in South Africa central to heranalysis, she shows how ideas about white supremacy, consumption andthe factory travelled. The resulting analysis suggests that whiteness wasdefined transnationally, but also emerged in ways profoundly impactedby specific national and subnational circumstances, demographics, andstructures. Thus ›Fordism‹, while seeking to reduce labor to a set of mo-tions standardizable within factories and across continents, ought alsoto be conceived of as set of distinct racial projects in which the Amer-icanized white U.S. assembly line worker came to embody possibilitiesneeding to be adapted to the rest of the world.

(Wulf D. Hund, for the editorial committee)

Accounting for the Wages of Whiteness

U.S. Marxism and the Critical History of Race

David Roediger

Abstract: Beginning in 1990, a series of historical studies of the United Statesadopted a common focus on how and why whiteness arose and persisted as a so-cial category, inaugurating a new body of scholarship on the study of race. The au-thor’s own The Wages of Whiteness became a much-praised and sharply critiquedcontribution to this literature. That book, and the study of whiteness generally,have often been cast as indicative of trends towards postmodernism in the study ofhistory. The article argues instead that the major works launching the critical his-torical study of whiteness, especially those of Theodore Allen, Alexander Saxton,and Noel Ignatiev, represented generations of specifically Marxist thought aboutrace, hearkening back to the union struggles of the 1930s and 1940s, as wellas the acceleration Black freedom movements of the 1960s, even as they triedto make sense of working class conservatism during the later period in whichthey appeared. The Wages of Whiteness shared these Marxist origins, and joinedothers in the emerging field in being decisively influenced by Black radical schol-ars, especially C. L. R. James, James Baldwin, and W. E. B. Du Bois. Even thewidely misunderstood use of psychoanalysis by those critically studying white-ness emerged from within a Marxist tradition. Across differences in approachand in conclusions, critical white history emerged within an historical materialistmilieu.

Nell Irvin Painter’s recent and excellent The History of White Peoplemaintains, »Critical white studies began with David R. Roediger’s TheWages of Whiteness: The Making of the American Working Class in 1991and Noel Ignatiev’s How the Irish Became White in 1995«.1 I have spentlots of energy over the last twenty years in order to not be the figurePainter points to, and for some very good reasons. However, in this arti-cle I want to acknowledge some kernel of truth in what she holds.

The good reasons for disavowing being a founder (or co-founder)of critical whiteness studies are several. To produce such a lineage po-tentially takes the 1990s moment of publication of works by whites on

1 Nell Irvin Painter: The History of White People, p. 388.

10 David Roediger

whiteness as the origin of a ›new‹ area of inquiry, when in fact writersand activists of color had long studied white identities and practices asproblems needing to be historicized, analyzed, theorized, and countered.The burden of my long introduction to the edited volume Black on White:Black Writers on What It Means to Be White, is precisely to insist on lo-cating the newer studies within a longer stream, on whose insights theyrely. Moreover, even in the last twenty years the most telling critiques ofwhiteness have come from such writers of color such as Toni Morrison,Cheryl Harris and now Painter.2

My desire has thus been to acknowledge the critical study of white-ness as a longstanding tradition, pursued mainly by those for whomwhiteness has been a problem, including some radical white scholarswho now join the argument that an embrace of white identity has led toabsences of humanity and of the effective pursuit of class interest amongwhites. To adopt this broader and more accurate view of the work that hadbeen done seemed to me to most effectively guard against the view thatstudying whiteness was a fad, akin to passing fancies like ›porn studies‹.Writing an early article on ›whiteness studies‹ in ›New York Times Mag-azine‹ in 1997 Margaret Talbot distilled this view with particular venomand lack of comprehension. Lamenting that the fad was part of a largertrend toward »books that seem ill-equipped to stand the test of time«,she chose to only consider white writers on whiteness, and indeed wroteunder the title »Getting Credit for Being White«.3

The particular identification of The Wages of Whiteness and How theIrish Became White as founding texts have also threatened – in the de-signs of others, not Painter – that the genealogy of the field thus cre-ated would set up attacks on it as an ultra-radical project designed to fur-ther revolutionary aims, not scholarly knowledge. That is, Ignatiev and Ihave occupied high profiles as figures whose books have circulated fairlywidely among young activists and whose desire to further the ›abolitionof whiteness‹ has been repeatedly stated. The rightwing journalist DavidHorowitz’s hysterical attacks on ›whiteness studies‹ have most insistentlyplayed on the theme that such work is not scholarship at all, but indoc-trination and propaganda. Horowitz once extravagantly and implausiblytried to locate critical studies of whiteness »in the theoretical writings andpolitics of mass murderers like Lenin and Mao, and totalitarian dictatorslike Fidel Castro, Ho Chi Minh, Stalin, Hitler and Mussolini«.4

2 Cf. David Roediger (ed.): Black on White, pp. 1-26; Toni Morrison: Playing in the Dark;Cheryl Harris: Whiteness as Property.

3 Margaret Talbot: Getting Credit for Being White, pp. 116-119.4 David Horowitz: Ethnic Studies or Racism; Chris Weinkopf: Whiteness Studies.

Wages of Whiteness 11

Eric Arnesen’s three ever-shriller essays on the subject warn simi-larly against ›whiteness studies‹. They score red-baiting points – argu-ing that radical politics drives the manipulated conclusions of writingson whiteness – saving the greatest contempt for my work and especiallyIgnatiev’s, as species of »sectarian moralism«. Regarding Ignatiev, Arne-sen would seem to prefer a purge to debate, writing, »that his [Ignatiev’s]political cult-like sensibility should find a respectable place in universityhistory departments is a testament to the academy’s perhaps overly gener-ous and ecumenical culture (at least toward matters considered progres-sive)«. On this view, Ignatiev’s political activism imparted an indeliblemark of »left splinter-sectarianism« to his historical accounts. My ownsin is to advance »outlandish« anti-racist politics as part of academicwriting – to go beyond the »discursive barricades« and to advocate an›assault on white supremacy‹ in the real world.5

All of this said, I would no longer fully demur from Painter’s dating ofa new early-1990s beginning for the critical studies of whiteness, as longas it is clear that we are considering the field’s specific emergence withinthe discipline of United States history and acknowledge that if Ignatievand I stood as faces most identified with the boldness and revolutionarycommitments of that beginning, we were far from alone in it, or at itsintellectual head. To include a fuller roster of those writers of the historyof whiteness from the 1990s as founders of a new phase in the evolutionof this inquiry would thus both add accuracy and lessen the vulnerabil-ity of the field to attack, though other important figures equally pursuedactivist projects and held left commitments intellectually. In particularAlexander Saxton and Theodore Allen were there at the beginning andwith weightier early books than mine and Ignatiev’s. Soon Venus Green,Michael Rogin, George Lipsitz, Bruce Nelson, and Karen Brodkin wouldbe publishing important studies.6

Ignatiev and I mainly contributed the most memorable soundbites –the idea of whiteness as a ›wage‹ and the insistence that some immigrants›become white‹, though even there the phrasings are, as we shall see, verymuch in the debt of older works by the African American socialist writersW. E. B. Du Bois and James Baldwin. The presence of this larger groupof heterodox, overwhelmingly Marxist, radical historians of whiteness in

5 Eric Arnesen: Passion and Politics, pp. 340 f.; Eric Arnesen: Paler Shade of White,pp. 33 ff.

6 Cf. Alexander Saxton: Rise and Fall of the White Republic; Theodore Allen: The In-vention of the White Race; Venus Green: Race on the Line; Michael Rogin: Blackface,White Noise; George Lipsitz: The Possessive Investment in Whiteness; Bruce Nelson:Divided We Stand; Karen Brodkin: How Jews Became White Folks.

12 David Roediger

the 1990s ensured that the slight books Ignatiev and I wrote could not beentirely marginalized and indeed soon received intense discussion acrossdisciplines.

This essay hence attempts to situate the 1990s origins of a new, dis-tinctly history-based body of critical studies of U.S. whiteness among acircle of writers with common and disparate left experiences and Marxistideas, dating back at least to the 1960s and in some cases to the 1930s.The authors of these studies often shared mentors, inspirations, and pub-lishing venues. We knew each other by the twos, threes and fours, al-though we never functioned as a group and in fact would have bridled atthe idea that a field of ›whiteness studies‹ should exist outside of radicalhistory and ethnic studies.

The article attempts then to describe a milieu, and to recall some ofits formation, suggesting the key role of a Marxism grounded in laboractivism and in the ideas of C. L. R. James, Baldwin, George Rawick,and above all Du Bois. Even the embrace by some of us of psychoanaly-sis as a way to shape inquiries emerged, this article argues, from withinthe left. The achievement of Marxists in recasting study of race throughcritical histories of whiteness deserves emphasis because the successesof historical materialism in the U.S. have been rare enough over the lasttwo decades. The field’s emergence as an historical materialist project,and partly in the specific context of the Black freedom movement, alsowarrants elaboration because there is some tendency among academiccritics to imagine that the critical study of whiteness issues from post-modernism, Freud, and identity politics, even in opposition to Marxism.At its most sloppy, or desirous of scoring supposed points for one kindof Marxism over another, such criticism descended to branding criticalwhiteness studies as a »critique of historical materialism« or as an ex-pression of »the anti-materialism so fashionable at present« or even (in acritique of Allen of all writers) as »extreme philosophical idealism«.7

Such critiques have typically credited Arnesen’s frankly empiricistand non-Marxist stance early in a review essay and then have later pro-nounced on which books under consideration are sufficiently materialistand which are not. (It might be said in mitigation that Arensen in thespace of a few lines was capable of criticizing whiteness scholars fornot making a ›cleaner‹ break from Marxism, and then to brand them as›pseudo-Marxists‹, implying perhaps that he held some unstated commit-ment to a fully unspecified ›real‹ Marxism. He likewise could deride psy-

7 Brian Kelly: Introduction, pp. xxix, x and xl (›critique‹, ›anti-materialism‹ and ›ideal-ism‹).

Wages of Whiteness 13

choanalysis and simultaneously claim a perch from which to judge othersas practicing ›pseudo-psychoanalysis‹. There was ample room for confu-sion).8 In some cases there crops up among scholars who have scarcelyacknowledged the existence of Marxism in their long careers a suddeninterest in defending Marxism against ›whiteness studies‹, one whichcomes to be directed against those you have long written as Marxists.9

A Long Left Project

Weighty books of history are often responsive to the dangers of the mo-ments in which they appear, but they cannot be called into being in thosemoments. Much, and not so much, should therefore be made of the factthat the first major studies of working class white identity and practicewere written in reaction to the 1980s regimes of Ronald Reagan and pub-lished in or just after the term of George Herbert Walker Bush in the1990s. These presidencies locate the then-new studies not only in reac-tionary times, but also in periods in which substantial numbers of whiteworkers, even union members, voted for reaction. For writers, and read-ers, of critical histories of whiteness, the moment elicited a passionateinterest in working class conservatism and its relationship to race. Think-ing and voting as whites, rather than as workers, made the white worker aproblem in the present and opened possibilities of making the emergenceof the white workers an historical problem as well.

However, the longer trajectories of figures like Saxton and Allen sug-gest more varied inspirations. Appearing in 1990, Saxton’s The Rise andFall of the White Republic: Class Politics and Mass Culture in Nine-teenth Century America predated all of the other books under consider-ation here. Rise and Fall was Saxton’s fifth book, following three prole-tarian novels from the 1940s and 50s, and the brilliant account of laborand anti-Chinese racism in California, The Indispensable Enemy: Laborand the Anti-Chinese Movement in California. Coming to the Commu-nist movement in the 1930s, after education at Harvard and Universityof Chicago, Saxton became an organizer in the railroad and constructionindustries and served as a paid publicist for the Committee on MaritimeUnity, a left effort to unite workers in unions with very different prac-tices where race was concerned. He entered graduate school in historyat University of California midlife after losing the opportunity to market

8 Andrew Hartman: Rise and Fall, pp. 23, 26 and passim; John Munro: Roots of ›White-ness‹, pp. 175-192; Eric Arnesen: A Whiter Shade of Pale, pp. 33 ff. (›pseudo‹).

9 Peter Kolchin: Whiteness Studies, pp. 156, 159, 166 and passim.

14 David Roediger

fiction, and for a time his requests for a passport, amidst early Cold Warrepression.10

Saxton’s labor activism frequently centered on race even in the un-commonly tough Jim Crow atmospheres of the railway brotherhoods andthe building trades. When he attempted to explore anti-discriminationstruggles among railroad workers in his 1948 novel The Great Midland,Saxton had to look to the mass production industries to imagine howthings might be plotted. As he wrote in reissuing the novel later, he had»never heard of any shop steward on any railroad who defended blackworkers«. At one 1940s point, Saxton agitated for fair employment in therailway crafts and ran into the argument that African Americans shouldhave no representation on fair employment practices committees becausethey would act out of racial loyalty and self-interest, as whites suppos-edly did not. »Apparently«, he bitingly observed, »white men belong tono race«.11

Saxton’s attempts to think through how to write about race and classin fiction led in similar directions. An avid student of John Steinbeck’spopular successes, he later wrote of the latter’s decision to make theworkers in Grapes of Wrath white refugees from the Oklahoma DustBowl, not »Mexican and Mexican American proletarians« as part of pat-tern in which »white racism enters [into Steinbeck’s work] not generallyas affirmation but in the form of silences and omissions«.12 His magnif-icent first academic book, The Indispensable Enemy, dissected the dis-figured labor unity eventuating from organization on as white workersand against Asian workers. Saxton’s later activism against the VietnamWar and activities in founding Asian American studies joined his labororganizing in shaping his treatment of race in Rise and Fall of the WhiteRepublic, which emphasized the connections of race to power, and to anability to create cross-class ›white‹ coalitions at every turn.13

Similarly, Theodore Allen drew on a half-century of radical organiz-ing, much of it specifically in industry, in writing his two-volume TheInvention of the White Race in the 1990s after a series of antecedent arti-cles and pamphlets, mainly with radical presses. Born into a middle-classfamily in Indianapolis and raised also in West Virginia, Allen was »pro-

10 Alexander Saxton: Rise and Fall, pp. xiii-xviii, Robert Rydell: Grand Crossings,pp. 263-285, Alexander Saxton: The Great Midland, pp. xv-xxx and Josephine Fowler:Transcribed Interview with Alexander Saxton, passim, provide the details on Saxton’slife and work.

11 Alexander Saxton: The Great Midland, pp. xvii f.12 Alexander Saxton: In Dubious Battle, p. 260, n. 20.13 Cf. Robert Rydell: Grand Crossings, p. 280 and passim; Alexander Saxton: The Indis-

pensable Enemy and Rise and Fall of the White Republic.

Wages of Whiteness 15

letarianized by the Great Depression«, as he put it. He tried college fora day, finding it uncongenial to independence of mind. By 17, he hadjoined the American Federation of Musicians and was soon a delegate tothe central labor body in Huntington, West Virginia and a member of theCommunist Party. He came into the Congress of Industrial Organizationsmining coal in West Virginia, a state where the United Mine Workerswas a racially diverse organization and where the extent of interracialunity very much shaped the prospects of unionism. After an injury tookhim from the mines, Allen worked mainly in New York City as a factoryoperative, retail clerk, draftsman, a math teacher at Grace Church School,and later a mail handler, museum worker and librarian at Brooklyn PublicLibrary. Leaving the Communist Party in the late 1950s, he was immedi-ately active in the Provisional Organizing Committee to Reconstitute theCommunist Party.14

In the 1960s Allen attempted to engage the New Left around thequestion of its ›blindspot‹ around race and particularly what he saw asthe formation of the white race as the real ›peculiar institution‹ in U.S.history. Allen’s historical work sought to provide a firm grounding forthe position that identification of some workers with the white race con-stituted the ›Achilles heel‹ of U.S. revolutionary possibilities. So muchwas this the case, and so underdeveloped was thinking on the problemfrom the left that Allen titled a late 1960s work Can White Radicals BeRadicalized? However, in sharp contrast with some others who embracedthe term ›white skin privilege‹, such as the Weatherman tendency insideStudents for a Democratic Society (SDS) and then after it, the analysis re-garded white workers as capable of being drawn to revolutionary actions.As they learned not be deterred from pursuing their long-term interests bymeager and even pitiful short-term and relative advantages, such workerswould, on this view, come to see struggles for liberation of other racescentral to the movement of a class.15

As it was put in the title of a 1967 pamphlet to which Allen con-tributed, Understanding and Fighting White Supremacy, became his dualtasks, inseparable and deadly serious. The simultaneous argument forboth the overwhelming weight of race in social control throughout U.S.history, and the possibility that its weight could shift and change the mo-mentum of struggles decisively made Allen elaborate history, and espe-

14 Jeffrey Perry: In Memoriam, p. 3 (›proletarianized‹), cf. ibid., pp. 1-4; Jonathan Scott:Introductory Notes on Theodore Allen’s ›Base and Superstructure and the SocialistPerspective‹, pp. 77 ff.

15 Cf. Michael Staudenmaier: Revolutionaries Who Tried to Think, pp. 7 ff.; Jeffrey Perry:In Memoriam, pp. 4-8; Michael Staudenmaier: The White-Skin Privilege Concept.

16 David Roediger

cially the colonial histories of Ireland and Virginia, very carefully. Bythe time of his 1975 pamphlet Class Struggle and the Origin of RacialSlavery: The Invention of the White Race Allen had made the interra-cial Bacon’s Rebellion the key event in his accounting of the turn to raceas the centerpiece of class control by Virginia’s elite and in his subtitlehad set out the agenda of his research over the next two decades. In hisepic two volumes on that invention, the British development of interme-diate control strata to enforce colonialism in Ireland provides not onlya comparative case to seventeenth century Virginia but also one whoselessons were inter-imperially deployed in ruling North American places.The effect of concentrating on the two cases is to divorce racial oppres-sion from the timelessness of allegedly natural realities, to make it anhistorical phenomenon, but a very longstanding and often decisive one.

Allen’s collaborator, Noel Ignatin, would also become a leading fig-ure in writing the critical history of whiteness a quarter century later,by then writing under the name Noel Ignatiev. Ignatin, born in Philadel-phia, dropped out of University of Pennsylvania in the early 1960s andfor twenty-three years worked in Chicago and elsewhere in the steel,farm equipment, and electrical industries, gaining skills as an electricianand machinist. He met Allen around efforts to reconstitute a communistmovement in the 1960s. The two joined forces on a pamphlet addressing›white skin privilege‹ in 1967. Ignatin went from Students for a Demo-cratic Society (SDS) to become a central figure in the Sojourner TruthOrganization (STO) from its founding in 1969 through the 1970s. STOdistinctively mixed Leninism, workplace- (but not trade union-) based or-ganizing, attraction to the ideas on race, class and nation of the Trinida-dian revolutionary C. L. R. James, efforts at critical solidarity with Blackand Puerto Rican revolutionaries, and close study of both U.S. historyand of the historical materialism generally.

Active on many fronts, Ignatin particularly wrote on race and theworking class, processing experiences within plants in the 1972 speechcirculated internally as ›Black Worker, White Worker‹ and published in1974 as Black Workers, White Workers. The talk described white work-ers’ identity as the result of ›sweetheart agreement‹ between bosses andthem. That agreement left bosses still bosses and workers as workers whohad learned to »HUG THE CHAINS OF AN ACTUAL WRETCHEDNESS«.The analysis was controversial even inside STO. When ›Radical Amer-ica‹ published it, editors issued objections in a sort preamble even asthey ran the piece.16 Twenty years later Ignatiev’s How the Irish Became

16 Noel Ignatin: Black Workers, White Workers, pp. 40, 47 and 41-60; Michael Stauden-

Wages of Whiteness 17

White would wrestle with similar questions of how to balance consentand coercion as they intertwined in making some workers white in thenineteenth century U.S.

Though separated from Ignatiev in age by only a decade, my own ex-periences were those of a different political generation, joining the NewLeft late its evolution in 1969 and coming to be an SDS leader in 1970 ina vibrant chapter on the isolated Northern Illinois University campus ata time when the organization had finished its national existence, but wewere not told. My political experience in SDS, the revolutionary socialistRed Rose Bookstore Collective, and the pro-strike and anti-Nazi Chicagoorganization called Workers Defense, featured very much an orthodoxMarxist education, leavened by encounters with a declining movementfor Black Power, with a rising movement for women’s liberation, withsurrealism, and with old-time libertarian Marxists gathered in the collec-tive running the Charles H. Kerr Company, the world’s oldest socialistpublisher. I chaired Kerr’s board in parts of the 80s and 90s.

That my work is sometimes linked to the post- (and anti-) Marxism ofChantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau is thus remarkable in that I actuallyresisted even much use of Antonio Gramsci’s increasingly mainstreamedMarxist work as a concession to reformism. Similarly, the emphasis insome of my work on the coinage and usage of ›keywords‹ – for example›boss‹, ›master‹, and ›greaser‹ – for better and worse came not from deepknowledge of what Arnesen calls »the growing appeal of cultural studies,with its emphasis on [. . . ] word play«, but from the British Marxism ofRaymond Williams and the Russian Marxism of M. M. Bakhtin.17

Similarly, the attempt in Wages of Whiteness to put the choices ofantebellum white workers to define themselves as ›not slaves‹ and ›notblack‹ in the context of processing the alienation and time discipline at-tendant on proletarianization, rather than simply in the context of inter-racial labor competition, was informed decisively by consideration of thework of the British Marxist historian E. P. Thompson.18 When SouthAfrican solidarity work became the focus of my activism in the late 80sand 90s, the attendant learning was again principally from Marxists, espe-cially those attempting to open discussions of ›racial capitalism‹, so that

maier: Unorthodox Leninism, passim; id.: Revolutionaries Who Tried to Think, pp. 11-27 and 31-37.

17 Cf. David Roediger: Wages of Whiteness, p. 17, n. 34 and Eric Arnesen: WhitenessStudies and the Historians’ Imagination, p. 4; on Laclau and Mouffe, cf. Sharon Smith:Race, Class, ›Whiteness Theory‹ at http://www.isreview.org/issues/46/whiteness.shtmland Roediger: Wages of Whiteness, p. 17, n. 28.

18 David Roediger: Wages of Whiteness, pp. 9, 95.

18 David Roediger

among the most cherished responses to Wages of Whiteness became forme Jeremy Krikler’s attempt to adapt some of its ideas to South Africanhistory.19

For others too interventions in working class struggles shaped schol-arship on whiteness. The leading study of the labor process and the whiteworker came in Bruce Nelson’s 2001 volume Divided We Stand: Ameri-can Workers and the Struggle for Black Equality. Nelson dropped out ofBerkeley to become a radical labor activist for most of the 1970s, workingon a truck assembly line before pursuing a doctorate. Venus Green, whosemagnificent Race on the Line remains the most insightful account of howwhiteness functioned in a context of labor, skill and law in one industrylabored and organized in the telephone industry that she studies for a longperiod before completing a Columbia Ph.D.20 Karen Brodkin warmed upto writing her How Jews Became White Folks by completing a wonder-ful anthropological account of multiracial struggles of hospital workers,an account she cast as one of solidarity as well as scholarship. GeorgeLipsitz, whose The Possessive Investment in Whiteness stands among themost-cited of the seminal works under consideration here, »enrolled ingraduate school hoping to learn enough about labor history to understandour failure« after the rout of a radical collective he joined in the early1970s to support an oppositional rank-and-file caucus in a Teamsters Lo-cal in St. Louis.21

Confluences

Several webs drew us partly together well before the 1990s, beyond theclose collaboration of Ignatin and Allen. Lipsitz and I were in St. Louis,and around the same oppositional labor groups, at about the same timein the early 70s and came to know each other through mutual admirationfor the St. Louis-based Marxist historian George Rawick, whose 1972classic From Sundown to Sunup: The Making of the Black Communityclosed with an extended meditation on the origins and costs of whiteness.Rawick, Allen, and Ignatin all wrote widely circulated, often reprinted,and deeply provocative articles on race and class for the sometimes SDS-connected journal ›Radical America‹, also a major source of work by C.

19 Cf. Jeremy Krikler: Lessons from America; Allison Drew, David Binns: Prospects forSocialism in South Africa.

20 Cf. Bruce Nelson’s website at http://www.dartmouth.edu/ history/faculty/nelson.html;Venus Green: Race on the Line, pp. ix ff.

21 George Lipsitz: Conversations with Scholars of American Popular Culture, p. 4; KarenBrodkin: Studying Whiteness, pp. 1 ff.; Karen Brodkin Sacks: Caring by the Hour.

Wages of Whiteness 19

L. R. James, a major direct influence on Ignatin and, through Rawick, onLipsitz and myself. My most reread source on James was the 1981 specialissue of the Sojourner Truth Organization’s special issue of Urgent Tasksdevoted to him, for which Ignatin, Rawick and I all wrote.

In the late 1970s, when I met Ignatin in Chicago, it was through mu-tual friendships with members of the Chicago Surrealist Group, espe-cially Penny and Franklin Rosemont, the latter of whom eventually pro-duced a brilliant article on the history and logic of surrealism’s critiqueof whiteness, published in ›Race Traitor‹ under the co-editorship of Ig-natiev (formerly Ignatin). Although we disagreed sharply on the role oftrade unions at the time, a particular formulation in Ignatin’s ›RadicalAmerica‹ reflections on Black and white workers had very much enteredmy consciousness: »the key problem is not the racism of the employ-ing class, but the racism of the white worker (after all, the boss’s racismis natural to him because it serves his class interests)«.22 As much as Inow regard the two problems as inextricably linked, the emphasis on thewhite worker’s centrality to the racial order was a hard-won insight avail-able in few other places on the left, save those dismissing white workersaltogether.

When book-length works on whiteness and the ›white blindspot‹ inU.S. history began to appear several major works appeared in one series,with Haymarket list from Verso/New Left Books publishing the work ofSaxton, Allen and myself, under the editing of Mike Davis and MichaelSprinker. The Haymarket Series likewise published Vron Ware’s Beyondthe Pale and Fred Pfeil’s White Guys as early and important interventionsin the newly developing field. I was the press’ reader for Allen’s works,offering little to improve his force and eloquence, but some advice onhow to pare the manuscript’s daunting length and to divide it into twovolumes. When Verso later reissued Saxton’s White Republic, I wrote theforeword.23

The extent and meaning of such connections can be overstated. Forexample, Allen and I met only once, despite his staying on a first-namebasis throughout the writing of his massive critique On Roediger’s Wagesof Whiteness. Nor, of course, did a common commitment to Marxism im-ply agreement on particulars, with the tone and content of that same Allenessay providing a good example, right down to Ted’s rejection of the veryterm ›whiteness‹. (These, however, were political arguments in which it

22 Noel Ignatin: Black Workers, White Workers, p. 47; for the previous see Franklin Rose-mont: Surrealism.

23 Cf. Alexander Saxton: Rise and Fall of the White Republic.

20 David Roediger

should be said that Allen’s tone was far more balanced and comradelythan glosses on his position have been).24

The common choice by Ignatiev, Allen, and myself of the experi-ences of the Irish as keys to white racial formation makes sense in termsof Marx’s and Engels’s own emphases on the Irish as central to how theBritish working class was divided and ruled, but our various accountsof the Irish spin in very different directions, separated by centuries intime and an ocean in space.25 In the balance of this article, some ofdifferences among the early U.S. writers of critical histories of white-ness will become clear, especially concerning the use of psychoanalysis.These were, however, differences among Marxists, not, as is sometimesargued, differences between Marxism and cultural studies. As Ignatievputs it in characterizing of his work, mine, Saxton’s and Allen’s »whatthese works have in common [. . . ] is that they take class struggle as theirstarting point« – class struggle, as we shall see, as theorized especiallyin a moment of high and grounded appreciation of the work of BlackMarxists.26

In a high compliment marred only by his desire to be dismissiveand offensive, the Princeton historian Sean Wilentz has called the crit-ical study of whiteness »black nationalism by another means«.27 Someof the writers above might demur from the specific terminology, feel-ing need to distinguish between narrow and revolutionary nationalismsor even to note the narrowness in all nationalism. However termed, ina broad sense the impact of African American struggles and thought,especially in the moment of Black Power, shaped the critical study ofwhiteness decisively. Suddenly, there was a ›white left‹ named as suchand even developing self-awareness and self-critique. There was, after themid-60s articulations of Black Power, after the statements of the StudentNon-Violent Coordinating Committee on the need for white radicals toorganize among whites and against white supremacy, and above all aftertremendous motion by Black industrial workers in Detroit and elsewhere,a new possibility opened for a pamphlet like Allen’s late 60s interventionCan White Radicals Be Radicalized? to be written and read. There was,as Ignatiev memorably put it in the early 70s, a »civil war in the mind«

24 Cf. Theodore Allen: On Roediger’s Wages of Whiteness, pp. 1-27 and Gregory Meyer-son: Marxism, Psychoanalysis, and Labor Competition, passim.

25 Cf. Noel Ignatin: White Blindspot, p. 9; Noel Ignatiev: How the Irish Became White,passim; David Roediger: Wages of Whiteness, pp. 133-163; Theodore Allen: Inventionof the White Race, vol. 1, pp. 152-158.

26 Noel Ignatiev: Whiteness and Class Struggle, p. 228.27 Wilentz as quoted in Margaret Talbot: Getting Credit for Being White, p. 119.

Wages of Whiteness 21

of some white workers as they reacted to the appeals of the energy andsuccess of Black workers’ struggles.28

The realization, as Ignatiev later wrote, that »[a]s a matter of survival,the direct victims of white privilege have always studied it«, became es-pecially powerful in this context of glimmers of white left self-awarenessand of a too-often ignored continuing common work among Black andwhite radicals during the Black Power period.29 The specific contribu-tion that Ignatin first, and I later, found in the example and writing ofC. L. R. James, was a longstanding insistence that struggles for AfricanAmerican liberation were not separate from or subsidiary to the ques-tion of class conflict. This became an important argument for the need toencourage white workers to support Black liberation as their struggle.30

The approach to the connection of immigration and whiteness, and to thesenses in which some despised and poor European immigrants ›becamewhite‹ in the U.S., very much grew from the essays of James Baldwin.Most of these came to be collected in his The Price of the Ticket, the ti-tle of which connects whiteness, migration and misery in the U.S. Butin terms of offering a ›plot‹ for the racialized history of immigration, itwas Baldwin’s short, direct and popular 1984 piece On Being ›White‹and Other Lies in the African American fashion magazine ›Essence‹ thatgave us the decisive formulation: »White men – from Norway, for ex-ample, where they were Norwegians, became white by slaughtering thecattle, poisoning the wells, torching the houses, massacring Native Amer-icans, raping Black women«. However much this dramatic rendering re-quired more – for example, more of the sense and practice of race ofthe Irish in Ireland and the British Empire before coming – it distilled atruth that opened tremendous intellectual space in immigration history.Ignatiev, who made me aware of the ›Essence‹ article, most ably claimedthat space in his How the Irish Became White.31

Apprehending Du Bois

Such connections among African American thought, Black Power, andthe critical history of whiteness focused especially on multiple and long-

28 Noel Ignatiev: Black Workers, White Workers, p. 42.29 Noel Ignatiev: Whiteness and Class Struggle, p. 228.30 Cf. Scott McLemee (ed.): C. L. R. James on the ›Negro Question‹, passim.31 David Roediger (ed.): Black on White, pp. 177 f. (›Norwegians‹); see James Baldwin:

The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, esp. pp. xix, 409-414, 425-433, 667-675; Noel Ignatiev: ›Whiteness‹ and American Character; Noel Ignatiev: How the IrishBecame White.

22 David Roediger

standing apprehensions of the great African-American thinker and mili-tant W. E. B. Du Bois. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America gavesubsequent writers both the terminology and the model with which toundertake their tasks. Thus Ignatin’s and Allen’s use of the term ›whiteblindspot‹, both in their 1969 pamphlet and afterwards, modifies a linefrom that Du Bois volume; in titling his article on race and shopfloordynamics Black Worker, White Worker, Ignatin used the first two chap-ter titles from Du Bois’s masterpiece, the first work to problematize the›white worker‹. The very idea of the ›wages of whiteness‹ came fromBlack Reconstruction’s memorable phrase regarding the »public and psy-chological wage« afforded to poor white Southerners after the Civil War,wages making them privileged and keeping them poor and in line. In-deed, Ignatiev wrote in a 2003 essay in Historical Materialism: »Amongscholars it was W. E. B. Du Bois who first called attention to the problemof the white worker«.32

Within the Communist Party, and the web of relations to AfricanAmerican organizations it maintained, Saxton and Allen encountered DuBois’s ideas in a way unavailable within the white academic mainstream,especially during the post-World War 2 period in which anti-Communistrepression sought to target and marginalize Du Bois. Saxton, as it hap-pened, shared both a hometown (Great Barrington, Massachusetts), anda university (Harvard) with Du Bois. And yet as Saxton later wrote, nei-ther place taught him about Du Bois. »What I learned about Du Bois«,he wrote, »I learned from the Communist Party«, whose literature repre-sentative sold Saxton Black Reconstruction at a time when it was largelyignored.

Similarly, Theodore Allen’s long experience in the Party left himknowing enough of the work of Du Bois to make it the basis of his rewrit-ing of U.S. history from the mid-1960s onward.33 As the radical labor ac-tivist and historian Jeff Perry, Theodore Allen’s literary executor, notedin a memorial after the latter’s death, Black Reconstruction informed thedesign of Allen’s historical writings from the start, namely mid-1960sattempts to overcome »the white blindspot« in a study of the Civil War,Populism and the Great Depression. In reacting to what he rightly saw

32 Noel Ignatin: White Blindspot; Noel Ignatiev: ›The American Blindspot‹, p. 243 (onDu Bois on the American Blindspot) and passim; Jeffrey Perry: In Memoriam, p. 4;David Roediger: Wages of Whiteness, p. 12; W. E. B. Du Bois: Black Reconstruction inAmerica, pp. 3-31 and 700 f. (›public and psychological wage‹); Noel Ignatiev: White-ness and Class Struggle, p. 227 (›first called attention‹).

33 Cf. Alexander Saxton: The Great Midland, p. xxiv; Noel Ignatiev: ›The AmericanBlindspot‹, p. 250.

Wages of Whiteness 23

as unjust neglect of Invention of the White Race by scholars late in hislife Allen took comfort in the view that the dynamic called to mind »the›white-centric‹ attitude that greeted the appearance of Du Bois’s BlackReconstruction, the classic class-struggle interpretation of the history ofthe post-Civil War South«. It was Allen who introduced Black Recon-struction to Ignatin.34

My own experiences in studying with the great African American ex-pert on Du Bois, and on Black nationalism and class, Sterling Stuckey,likewise made for constant readings and re-readings of Black Reconstruc-tion. Indeed more broadly, when I collected the writings for the editedvolume Black on White: Black Writers on What It Means to Be White,fully two-thirds of the selections were from classic readings in AfricanAmerican history I had done with Stuckey. While it is most often pointedout that Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction inspired the title of Wages ofWhiteness, it structured the book multiply and even entirely.

It was the ability to be able to see profound motion and tragicallypersistent patterns regarding race – to place the self-activity of Blackworker and the whiteness of the white worker at the very center of U.S.history – that made a Du Bois so indispensable. When, for example, Ig-natiev undertook an extended comparison of Du Bois’s work on Recon-struction with the more-publicized accounts provided by Eric Foner, heinsisted that the idea of a »general strike of the slaves« – so critical inDu Bois’s view of war and emancipation and so attenuated in Foner –made the two works qualitatively different. At stake was the centrality ofself-emancipation of slaves and the knowledge that this motion createdthe possibility that white workers might seek something more than being›not slaves‹.

From the first line onward, Du Bois insisted that Black Reconstruc-tion was »drama« and later that it was »tragedy«, as well. Du Bois por-trayed Black workers as at the center of everything as »the real modernlabor problem«. Emancipation brought an »upward moving of white la-bor«, but reassertions of white supremacy followed. In one of countlessformulations that show Du Bois linking the origins of race with capital-ism, but not adopting the farfetched view that white supremacy could notin turn be itself a decisive factor in class rule, he wrote that »color castefounded and retained by capitalism« was during and after Reconstruc-tion »adopted, forwarded and approved by white labor«. In the post-Civil

34 Jeffrey Perry: In Memoriam, p. 4 (›blindspot‹); Jonathan Scott, Gregory Meyerson: AnInterview with Theodore W. Allen, pp. 1 f. (›white-centric‹); Noel Ignatiev: ›The Amer-ican Blindspot‹, p. 243, n. 1.

24 David Roediger

War South and the world, »[w]hen white laborers were convinced thatthe degradation of Negro Labor was more fundamental than the uplift ofwhite labor, the end was in sight«.35

In trying to explain why white labor acquiesced (and more) in suchtragedies, all the while able to »discern in [them] no part of our labormovement«, Du Bois produced the passage that came to give Wages ofWhiteness its title. The passage begins with an acknowledgement that thegroup under consideration, white Southern laborers during Reconstruc-tion, »received a low wage«, as they would have to in a devastated anddefeated region. However, they »were compensated in part by a sort ofpublic and psychological wage [. . . ] because they were white«. »Publicdeference and titles of courtesy« accrued to them, as did admission toparks and the best schools Police »were drawn from their ranks«, andlegal structures, »dependent on their votes«, kept them out of jail. Thefranchise had »small effect upon the economic situation«, but much onperceptions of dignity, Du Bois adds, elaborating a litany of matters goingto both policy and psychology.36

It has been objected that treating the ›the wages of whiteness‹ in sig-nificant measure as psychological seems to dismiss the material benefitsalso forthcoming, with Ignatiev allowing that I perhaps took the mate-rial dimensions for granted. This is true enough but it also applies toDu Bois’s attempts in the original to show how a system worked whenresources of rulers were so meager that little buying off of anyone waspossible. My own task was also to describe a situation – the antebellumNorth – in which the small Black population meant that a labor marketcould not be shaped wholesale by racial competition and segmentationand ideological, psychological, political and cultural appeals to whitesmattered much more than immediate economic self-interest. Ignatiev isquite right that this was not always and everywhere the case.

In any case the main criticism from outside of Marxism was of a muchdifferent order, and by its very extremity perhaps helped Ignatiev and I tosee how close our positions were on a larger political spectrum. Arnesen,after a desultory attempt to develop and contextualize Du Bois’s ideas onthe ›public and psychological wage‹ suddenly shifted gears in a featuredInternational Labor and Working Class History essay to make Du Bois

35 W. E. B. Du Bois: Black Reconstruction in America, pp. 3 and 727 (›drama‹, ›tragedy‹),16 (›modern labor problem‹), 30 (›upward moving‹, ›color caste‹), 347 (›degradation‹);cf. Noel Ignatiev: ›The American Blindspot‹, pp. 244 and passim.

36 W. E. B. Du Bois: Black Reconstruction in America, pp. 700 f.; concerning the follow-ing see Noel Ignatiev: Whiteness and Class Struggle, pp. 230 f.; David Roediger: Wagesof Whiteness: pp. 6-12; Theodore Allen: On Roediger’s Wages of Whiteness, p. 7.

Wages of Whiteness 25

the problem. At first seeming – the writing is exceptionally unclear –to accuse ›whiteness studies‹ of adopting a superficial, decontextualizedreading of Du Bois, he then focuses on accusing Du Bois himself of em-bodying a foolish »Marxism-lite«. It then turns out that the ›lite-ness‹consists of adhering to the idea that workers have interests in common,not really one of the frothier notions of Marxism.37

Whatever else divided our views, it seems certain that Saxton, Allen,Ignatiev and myself took for granted that Du Bois had made anythingbut a ›lite‹ intervention into Marxism. Indeed Paul Richards 1970 articlein ›Radical America‹, W. E. B. Du Bois and American Social History:The Evolution of a Marxist described Black Reconstruction as we allwould have, not simply as Marxist but as central to any development ofan ›American Marxism‹. So ingrained was this assumption that my ownplacement of Du Bois after a section on the deficiencies of much Marx-ist writing was undoubtedly insufficiently clear for this reason. Neverimagining that Du Bois would be seen as a ›post-Marxist‹, let alone as›Marxism-lite‹, I took for granted that Black Reconstruction developed,rather than departed from (or debased) Marxist theory. That positionmade sense among the milieu writing early critical histories of white-ness, but led regrettably to confusion among a broader audience and astime passed.38

Marxism and Psychoanalysis

Deriding any taking seriously of psychoanalytical insights has emergedas a point of overwrought unity between rightward-drifting critics likeArnesen and left ones like Gregory Meyerson.39 But even here the de-bates ought to acknowledge that the use of the ideas of Freud and otherpsychoanalytical writers in Wages of Whiteness, came out of Marxismand Black revolutionary traditions.

A story regarding the great Marxist and psychoanalytical politicalscientist Michael Rogin perhaps provides a useful point of entry. WhenWages of Whiteness appeared, even with the example of Saxton’s Riseand Fall of the White Republic at hand, I worried that my work was be-

37 Eric Arnesen: Whiteness and the Historians’ Imagination, pp. 9-11, esp. 10 (›lite‹); PaulRichards: W. E. B. Du Bois and American Social History, pp. 62 and 56-61.

38 Paul Richards: W. E. B. Du Bois and American Social History, pp. 62 and 56-61; An-drew Hartman: The Rise and Fall of Whiteness Studies, p. 34 (›post-Marxist‹).

39 Eric Arnesen: Whiteness and the Historians’ Imagination, pp. 21-23; Gregory Meyer-son: Marxism, Psychoanalysis, and Labor Competition, passim; Frank Towers: Project-ing Whiteness, pp. 47-57.

26 David Roediger

yond all boundaries of acceptability, even intelligibility, and would beroundly attacked. Before reviews much appeared, Rogin sent me a draftof his essay on the book, slated to appear in ›Radical History Review‹.I did not know him at the time, only his extraordinary scholarship. Thegenerous and long review essay he wrote reassured me about the book’sreception – indeed it put the book’s arguments more clearly and adven-turesomely than I had. But there was one problem: Throughout the piece,in total dozens of times – the draft misspelled my name as ›Roedinger‹.After hesitating, I contacted him with thanks and with the hope that cor-rections might be made. They were, but the real payoff was Rogin’s re-sponse to me. He excitedly said that the error should be read as a tribute,an attempt to smuggle in an ›n‹ so that all letters in his name would be inmine as well, making him a ›father‹ of the book.

The response underlined what I already knew, that Rogin took psy-choanalysis more seriously than I. But it also sent me back to Rogin’sFathers and Children: Andrew Jackson and the Subjugation of the Amer-ican Indian, which I had remembered mainly for its ›psychohistory‹, butwhich also tellingly deployed Marxist categories of accumulation andwhich featured a long first section, amounting to a third of the book, ti-tled ›White‹. In that sense, Rogin was rightly claiming, at the level ofmethods (including historical materialism) and content, to have been a›father‹ of critical histories of whiteness. When Saxton was a graduatestudent at Berkeley, Rogin, who later became a leading student of white-ness and immigration, was one of his mentors.40

While, like many New Left students, I read attempts to bringMarx and Freud together – Herbert Marcuse, Norman O. Brown, JulietMitchell, Eli Zaretsky, Wilhelm Reich and above all Frantz Fanon –the specific possibility of applying insights from these works to race inU.S. history came through appreciation of the closing chapters of GeorgeRawick’s From Sundown to Sunup: The Making of the Black Commu-nity. There Rawick departed from his classic history of slavery to probemodern racism more broadly, especially in its early phases after Europe’s›discovery‹ of the Americas and expanded slave trade with Africa. Dur-ing this transition to capitalism, Rawick argued, the various repressions ofdesire required to fashion societies and personalities devoted to the accu-mulation of capital exacted tremendous human costs. Especially among

40 Iain Boal: In Memoriam, passim, esp. on Rogin’s ties to radical labor movements; LauraMulvey: Professor Michael Rogin; Michael Rogin: Black Masks, White Skin; id.: Fa-thers and Children, pp. xxxiv, 2 f., 19-113 and 165-205; id.: Blackface, White Noise;Robert Rydell: Grand Crossings, p. 279.

Wages of Whiteness 27

slave-traders and colonial slaveholders, white racism came to be devel-oped, indeed invented, hard by such repressions.

The Africans met and commoditized as part of the development ofplantation economies came to be seen as embodiments not only of ownedlabor, but also of the desires that elites had only recently, and only par-tially, repressed. In organizing their own disappointments and desires,elites imagined Black workers as both degraded and as possessed of tiesto nature, eroticism, and pre-capitalist work rhythms that held appealeven as they were deplored. In Rawick’s memorable phrasing, »[t]he En-glishman«, in such interactions, »met the West African as a reformed sin-ner meets a comrade of his previous debaucheries«, all the while creating»a pornography of his former life«.

Rawick, who as my friend and mentor taught me much about Marx-ism in the 70s and 80s, relied at key points on Marcuse, Fanon, Freud,and especially on the Austrian-born Marxist associate of Freud, WilhelmReich. Reich’s Nazi-era work attempted to understand the Mass Psychol-ogy of Fascism, as based on character structures wedded to both internal-izing and dealing out misery. Rawick called Reich’s Character Analysis»that great underground classic of modern thought« and held that his ownanalysis of white supremacist and master class ideology »could not havebeen written without [Reich’s] monumental attempt to relate Marx andFreud«. Rawick, a friend in the 1950s of Reich’s socialist associate, thepsychoanalyst Erich Fromm, risked much in so deeply calling on psy-choanalysis. C. L. R. James, for whom Rawick served as personal assis-tant in the 60s, found From Sundown to Sunup to be »the best thing Ihave read on slavery«, predicting it »will make history«. However, evenJames sharply registered displeasure with its Freudian closing chapters.Nonetheless such risks were incurred from within Marxism.41

My perhaps-too-simple analysis in Wages of Whiteness took Rawick’swork on race, slavery and early capitalism into the realm of the North-ern white working class formation in the antebellum period of workingclass formation. As proletarianization brought new losses of access to thecommons and new forms of time discipline and social regimentation tofar greater numbers of people, white workers processed loss by projectingonto Black workers what they still desired in terms of imagined absenceof alienation, even as they bridled at being treated as ›white niggers‹.42

41 George Rawick: Listening to Revolt, pp. xlii (James’s reaction), 102 (›reformed sin-ner‹), 180, n. 9 (on debts to Reich) and 31, 66, 162, 93-119; generally, see JohnAbromeit: Whiteness as a Form of Bourgeois Anthropology.

42 David Roediger: Wages of Whiteness, pp. 66-84; id.: Notes on Working Class Racism,pp. 61-67 explores specifics debts to Rawick.

28 David Roediger

There were likewise other inspirations beyond Rawick, as I had be-gun close association with the surrealist movement, where commitmentsto Marx and Freud coexisted. Especially through friendly debates withthe surrealist writers Paul Garon and Franklin Rosemont, I increasinglylearned about the older writings on racism of the important organizer of aglobal network of Marxist psychoanalysts, Otto Fenichel, and of SandorFerenci, as well as the more recent work of Joel Kovel.43

As importantly, I have come to understand that psychoanalysis wasthere at the beginnings with Du Bois’s choice to discuss a specifically›psychological wage‹ as central to white identity. The useful recent schol-arship on Du Bois and psychoanalysis at times gravitates too easily to-wards connections between ›double consciousness‹ and Freud’s ideas.However, since Du Bois had not read Freud when he wrote about ›dou-ble consciousness‹ in The Souls of Black Folk in 1903, such affinities hadto exist at a high level of abstraction regarding ideas emerging among›intellectual contemporaries‹.44

As Du Bois had it in his 1940 autobiography Dusk of Dawn, it wasin about 1930 that »the meaning and implications of the new psychologyhad begun slowly to penetrate my thought. My own study of psychology[. . . ] had pre-dated the Freudian era, but it prepared me for it. I nowbegan to realize that in the fight against race prejudice, we were not facingsimply the rational, conscious determination of white folk to oppress us;we were facing the age-long complexes sunk now largely to unconscioushabit and irrational urge«.45

In 1935, midway between that realization and Dusk of Dawn, Du Boispublished Black Reconstruction, which could thus hardly have used thephrase ›psychological wage‹ lightly. There is a sense then in which, thecritic Andrew Hartman, though fully unsympathetic to the Freudian ap-proach, is onto something in his overstatement that »Roediger furthers DuBois’s psychoanalysis«, though I certainly did not know enough about DuBois and Freud to see this dimension when I first wrote. In short, giventhese multiply Marxist inspirations, Bruce Laurie’s recent review essaycould not be more startlingly wrong when it connects the use of psycho-

43 David Roediger: Colored White, pp. 40 and 252, n. 36. On Fenichel, see Russell Jacoby:The Repression of Psychoanalysis.

44 Peter Coviello: Intimacy and Affliction, pp. 2 and 3-37; Christina Zwarg: Du Bois onTrauma. All of the material on Du Bois and psychoanalysis benefitted from research byDonovan Roediger.

45 W. E. B. Du Bois: Dusk of Dawn, pp. 295 f.; Shannon Sullivan: On Revealing White-ness, pp. 231 f.

Wages of Whiteness 29

analysis in my work to examples provided by the Southern conservativehistorian David Donald.46

As in the case of James’s reaction to Rawick, some of the early writersof critical histories of whiteness deplored the bits of psychoanalysis inWages of Whiteness. Allen in particular found »resort to the languageof psychoanalysis« unfortunate, but he to a surprising extent joined thefray, praising much in the work of Kovel and Fanon, though on somewhatnarrow bases, including the improbable view that Fanon »proceeded fromMarxist economic determinist premises«. Saxton’s firm judgment wasthat »difficulties seem exceptionally severe for psychohistory because ofits assumption that real causes are psychic ones that can be approachedonly through metaphorical interpretation«.47

This stance so impresses Hartman that his review essay hinges its pro-nouncement that Saxton is the best historian of whiteness – I agree – onit. It so impresses Eric Arnesen that he exempts Saxton from even hav-ing to be considered within the benighted study of whiteness. However,Saxton’s categorical pronouncements come as he explains why psycho-analysis cannot explain the origins of white supremacy, again a positionwith which I agree. Shortly thereafter, he discusses John Quincy Adams’sviews on Othello in a very different way and explains, »I am of coursebringing forward an argument previously rejected, to the effect that whiteEuropean Americans constructed metaphors linking African blackness toshameful actions and to the dark passions of sexuality«. He continued:»While I consider this [psychohistorical] argument unpersuasive as anexplanation for the initiation of African slavery, it seems to work plau-sibly well when placed in a dependent relationship to prior ideologicalproductions« – also a position with which I agree.48

Ignatiev meanwhile found that Wages of Whiteness »errs« by losingtrack of »attendant material advantage« without which there could hardlybe sustained »psychological value of the white skin«. However, he added,»I do not know enough about psychoanalysis to venture a judgment onhow much it can explain by itself«. Rogin, Rawick, and Rosemont, onthe other hand very much championed the use of psychoanalysis, thoughnot by itself. Like so much else, this is a question on which Marxists dif-

46 Andrew Hartman: Rise and Fall of Whiteness Studies, p. 35; Bruce Laurie: Workers,Abolitionists, and the Historians, p. 36.

47 Theodore Allen: On Roediger’s Wages of Whiteness, p. 9 (both ›resort‹ and ›economicdeterminist‹); Alexander Saxton: Rise and Fall of the White Republic, pp. xvi, 13 (›ex-ceptionally severe‹); the following quote is from ibid., p. 89 (›previously rejected‹).

48 Andrew Hartman: The Rise and Fall of Whiteness Studies, pp. 35 f.; Eric Arnesen:Whiteness and the Historians’ Imagination, pp. 27, n. 4 and 31, n. 83.

30 David Roediger

fer, though not as starkly as some retrospective accounts of early criticalwhite histories imply.49

Past and Present

A closing clarification of just what is claimed in this article is apposite, asare brief remarks on the field today and the continuing if diffuse impactof its radical origins. The argument is that the Marxist left generated themost influential early historical studies of whiteness in the U.S. past. Theclaim is not that by virtue of their historical materialist origins that thoseworks are therefore correct or complete. Indeed many of their gaps in mywork particularly might better be traced to their origins in the specificdebates and movements I have outlined above. The relative inattention togender, which Allen remarked on near the end of his life, is one example.I have attempted with mixed success to remedy this blindspot in Wagesof Whiteness, but to date more by adding rather than fundamentally re-thinking the whole ensemble of social relations.

We would been better poised perhaps if we had followed James Bald-win’s relationship to psychoanalysis, with its rich dimensions of sexualityand gender as well as race, as well as Du Bois’s invocation of psychol-ogy. Similarly, as my exchange with Rogin suggested, the classic Marxistdebates are much more at home discussing the relation of whiteness toslavery than to settler colonialism, another problem only beginning to beaddressed in my own work.50 Likewise it seems possible that a particulardesire to unearth the story of how white workers forwarded racism leftthe relationship of whiteness to capital and to management relatively un-derdeveloped.51 But however deep these deficiencies, which might makeus as Marxists think about the possibility that we do have much to learnfrom other bodies of theory, it remains the case that both the errors andthe considerable strengths in early critical histories of whiteness grew outof Marxism, in specific political moments.

More recent historical writing on whiteness in U.S. history hasemerged in a very different political context. As I argue at length inthe 2006 essay Whiteness and Its Complications, much such recent writ-ing on race in the U.S. is best understood as reflecting academic trends.

49 Noel Ignatiev: Whiteness and Class Struggle, pp. 230 f.50 Robyn Wiegman: Whiteness Studies and the Paradox of Particularity; Jonathan Scott,

Gregory Meyerson: An Interview with Theodore W. Allen, pp. 3 ff.; David Roediger:Colored White, pp. 103-137; id.: How Race Survived U.S. History, pp. 12-29, 51-63 and127 f.; Jean-Paul Rocchi: Dying Metaphors and Deadly Fantasies, pp. 159-177.

51 Elizabeth Esch, David Roediger: ›One Symptom of Originality‹.

Wages of Whiteness 31