Using an Ecological Framework to Understand Parent–Child Communication about Nutritional...

Transcript of Using an Ecological Framework to Understand Parent–Child Communication about Nutritional...

This article was downloaded by: [University of Missouri Columbia]On: 11 September 2013, At: 09:08Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Applied CommunicationResearchPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjac20

Using an Ecological Frameworkto Understand Parent–ChildCommunication about NutritionalDecision-Making and BehaviorKhadidiatou Ndiaye, Kami J. Silk, Jennifer Anderson, HaleyKranstuber Horstman, Amanda Carpenter, Allison Hurley & JeffreyProulxPublished online: 09 May 2013.

To cite this article: Khadidiatou Ndiaye, Kami J. Silk, Jennifer Anderson, Haley KranstuberHorstman, Amanda Carpenter, Allison Hurley & Jeffrey Proulx (2013) Using an Ecological Frameworkto Understand Parent–Child Communication about Nutritional Decision-Making and Behavior, Journalof Applied Communication Research, 41:3, 253-274, DOI: 10.1080/00909882.2013.792434

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2013.792434

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

Using an Ecological Framework toUnderstand Parent!ChildCommunication about NutritionalDecision-Making and BehaviorKhadidiatou Ndiaye, Kami J. Silk, Jennifer Anderson,Haley Kranstuber Horstman, Amanda Carpenter,Allison Hurley & Jeffrey Proulx

Investigating the content of communication about food and nutrition in the parent!childdyad can provide insight into how roles and rules associated with food are instantiatedwithin the family context. The current study uses an ecological framework to considerthe multiple levels of influence on communication and dietary behavior in families.Interviews (N "33) were conducted with parents and children from low-incomefamilies in two different counties within a Midwestern state. Interview transcripts wereanalyzed using categories developed from the ecological framework. Geographicinformation systems technology data also provided information about dyads’ externalfood environment and available food options. Results indicate low levels of commu-nication about food choices between parents and children, as well as low involvementfrom children in food selection and preparation. Findings also identify the accessibility ofhealthy food and financial considerations as key barriers to facilitating nutritionalchoices. Strategies for designing interventions that encourage initiation of familialdiscussions about food, promote positive nutritional role models, and highlight the

Khadidiatou Ndiaye (PhD, The Pennsylvania State University) is an Assistant Professor of Global Health in theSchool of Public Health & Health Services at George Washington University, Washington, DC. Kami J. Silk(PhD, University of Georgia) is an Associate Professor of Communication and Associate Dean of GraduateStudies at Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. Jennifer Anderson (PhD, Michigan State University) isan Assistant Professor at South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD. Haley Kranstuber Horstman (PhD,University of Nebraska-Lincoln) is an Assistant Professor at the University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia,MO. Amanda Carpenter (MA, Michigan State University) is a doctoral student in the Department ofCommunication at Rutgers University, Newark, NJ. Allison Hurley (MA, Michigan State University) is Web andMarketing Communications Specialist at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA. Jeffrey D. Proulx (MA, MichiganState University) is a doctoral. student and instructor in the Department of Communication at the University ofIllinois Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL. Correspondence to: Khadidiatou Ndiaye, The George WashingtonUniversity, Department of Global Health, School of Public Health & Health Services, 2175 K Street, NW, Suite200, Washington, DC 20037, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

ISSN 0090-9882 (print)/ISSN 1479-5752 (online) # 2013 National Communication Association

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2013.792434

Journal of Applied Communication ResearchVol. 41, No. 3, August 2013, pp. 253!274

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

importance of positive feedback and rewards for healthy food decision-making behaviorsare discussed.

Keywords: Ecological Framework; Parent!Child Communication; Nutrition; Decision-Making; Behavior

Dietary patterns of children and adults are influenced by their social environment

(Viswanath & Bond, 2007), including the information exchanged in the parent!child

dyad. Public-health professionals have called for increased attention to the role of thefamily in determining child eating habits and conversations about dietary choices

(Borra, Kelly, Shirreffs, Neville, & Geiger, 2003). Communication scholars haveargued that the health-communication environment of children*including the

influence of families, media, and other environmental cues*can significantly shape

children’s dietary patterns (Andrews, Silk, & Eneli, 2010; Flora & Schooler, 1995).Therefore, more communication research should focus on the factors influencing

family communication about nutrition (Baxter, Bylund, Imes, & Scheive, 2005), and

specifically, explore nutrition-related communication in families from the perspectiveof both parents and children.

Working within an ecological framework (Davison & Birch, 2001), this articlerecognizes the interplay between family culture and the environment within which

the family functions. The current article explores parent!child communication asone dimension of family culture that helps shape nutritional practices (Galvin,

Bylund, & Brommel, 2004); it focuses on family messages, interaction patterns,

and processes as salient features of the family culture. The ecological subcategories(child and individual characteristics; family and parental style factors; community

and societal factors) will be discussed in the context of family communication

research.The first section of this article will introduce an ecological model of predictors of

childhood overweight1 (Davison & Birch, 2001). Next is a discussion of familycommunication about nutrition. The third section explains the interview methods

used to collect data from parents and children as well as geospatial methods.Implications of findings are discussed as they relate to creating interventions and

strategies for improving parent!child communication about nutrition.

Literature Review

Ecological Model

Children’s dietary patterns are best understood with attention to the contextual

factors that influence such behavior. Human development researchers have long

posited that the context in which a behavior occurs interacts with the individual toinfluence his/her behavior (Bronfenbrenner, 1986). This perspective, originally

known as ecological systems theory (EST; Bronfenbrenner, 1986), has been renamed

254 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

bioecological systems theory (BST) to emphasize the role of biology in humanbehavior (Ryan, 2001). This theoretical perspective suggests that to understandindividuals’ health, one has to explore their ‘‘ecological niche’’ including family,school, religion, and then branch out to the community, society, and the outermostlayer of cultural influence.

These different influences are organized into five bi-directional systems: micro-systems (the inner layer including the direct impact on the individual), themesosytem (linking elements in the microsystem), exosystem (the indirect impactof society/community), the macrosystem (the furthest layer encompassing norms,beliefs, and culture), and chronosystem (addressing the impact of time and changes).Bronfenbrenner’s conceptual model highlights the impact of all these nestedenvironments and their reciprocal influences.

EST/BST has been applied to the context of childhood overweight to identify thecomplexity of predictors of this increasing health condition (Davison & Birch, 2001).In Davison and Birch’s (2001) ecological model, nested environments are con-ceptualized as characteristics impacting child health. As explained in the followingsection, at the core of the current study’s ecological model is child weight status,followed by child characteristics and risk factors, parental and family characteristicsand finally community and societal factors.

Child weight and individual characteristics. Child weight status is the core of themodel, as it serves as the central influence on child health (Davison & Birch, 2001).Child weight status is impacted directly by child characteristics and risk factors suchas gender, age, physical activity, and dietary patterns. For instance, children’s dietarypatterns are important to consider because they have been shown to be closely linkedwith children’s weight and body fat (Guillame, Lapidus, & Lambert, 1998). Individualchild characteristics (such as familial susceptibility to weight gain) have been shownto influence childhood overweight at the individual level (Heitmann, Lissner,Sorenson, & Bengtsson, 1995).

Family and parental styles factors. According to Davison and Birch (2001), the familyand parental styles level encompasses a wide range of factors including parents’encouragement of child activity, family and child television viewing, and childfeeding practices. This author asserted that family influence on children’s nutritionoccurs by sharing nutritional knowledge and health concerns from parent to child,parental modeling of nutritional behavior, parent!child interactions during mealtimes, and food-related control patterns. Parental behaviors, such as work schedules,have been found to directly impact child dietary patterns (Davison & Birch, 2001;Hill & Peters, 1998). For example, longer work hours increase the likelihood ofchildren consuming pre-made and convenience foods, which are often unhealthy. AsFlora and Schooler (1995) argued, family communication, both direct (e.g., talkingabout food at meal times) and indirect (e.g., modeling of dietary behaviors), areprimary means through which children’s dietary patterns are affected.

Family and child television viewing patterns may also impact the food conversa-tions and behaviors within the family because of food marketing (Institute of

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 255

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

Medicine, 2005). Food marketing largely targets young children, dominatesadvertising time during child-specific programming, and focuses on high-fat, low-nutrient foods marketed as ‘‘kid food’’ (e.g., Harrison & Marske, 2005). The direct-to-consumer marketing strategy seeks to convince children they should be makingtheir own food decisions. As a result, children are exerting influence in familypurchasing decisions (see The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation [KFF], 2004, forreview). These food marketing strategies color parent!child communication aboutfood at all levels of the ecological model, affecting other community-level factorsinfluencing parent!child decisions about food.

Community and societal factors. At the community level, various institutional andenvironmental factors influence child nutrition and exercise patterns (Davison &Birch, 2001). These factors include school lunch programs, family leisure-timeactivity, and the availability of healthful foods in a family’s community. The types offoods parents are able to provide to children are dependent on the availability offoods in nearby supermarkets (Cheadle et al., 1991), and this commercial foodenvironment is often coupled with the effect of socio-economic status (SES) onfamily dietary patterns. Families in lower SES groups have less diverse and lesshealthful diets than those in higher SES groups (Wolfe & Campbell, 1993). Also,individuals in lower SES groups are more likely to live in ‘‘food deserts’’ where freshfruits and vegetables are not as available when compared to their more affluentcounterparts (Ver Ploeg et al., 2009). The nutritional environment in which anindividual lives is important when analyzing potential health outcomes of givenenvironmental factors.

While taking an ecological approach to understand parent!child communicationabout health, the current study focuses on family and community levels of influence.Our goal is to highlight the importance and complexity of family communication ininfluencing childhood obesity. Our discussion of the community and childcharacteristics is centered on how these levels ultimately impact parent!childcommunication about nutrition.

Parent!Child Communication About Nutrition

The ecological model highlights a number of influences on health behaviors, andat the center of these experiences for children is the environment of the family(Davison & Birch, 2001), where children can learn about health and nutrition throughcommunication with family members. Families create meaning through stories, rules,rituals, patterns of interaction, and messages (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). Thesystem of meaning that develops from these interactions is a family’s culture (Galvinet al., 2004). Family cultures are created through discourse systemically, in process,and through time, thereby providing a family with structure, values, rules, andlanguage present in any culture. This systemic discourse can be examined byattending to family interaction patterns, processes, and power structures. Thesepatterns, routines, and rituals are useful to consider when examining the relationship

256 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

between family communication and health (Baxter & Clark, 1996; Segrin & Flora,2005).

Family interactions have been shown to have dramatic physical and psychological

effects on children. Many studies have shown that family distress negatively impactsboth parent and child health (for an overview, see Jones et al., 2004). Research hasalso examined the potential positive effects of family interactions on health like socialsupport within families and its relationship to the health of family members.

Specifically, family members who receive social support report fewer health problemsthan those who do not (Walen & Lachman, 2000), and supportive family structuresoffer many mechanisms for promoting proper diet and nutrition, including parentalcontrol and modeling of healthy behaviors (Cohen, Gottlieb, & Underwood, 2000).

Thus, when considering the effect of family communication on child health, it isimportant to investigate the way a variety of communication processes*includingfamily rituals, roles, rules, and decision-making strategies*work to predict childnutrition and health behaviors.

Family rituals. Family rituals have special shared meaning for the family (Jorgenson &Bochner, 2004) and symbolize something greater than the acts themselves (Baxter &Clark, 1996). Family rituals can be more or less formalized, and in terms of

understanding the impact of ritual on nutrition, perhaps the most important type ofritual to consider is patterned family interactions. Although patterned familyinteractions are informal, casual, and common, they can have larger symbolicmeaning. For example, sharing dinner together can provide symbolic communication

about family roles, expectations, rules, and values (Wolin & Bennett, 1984). Familyprocesses as a whole are influential for lifestyle health issues such as nutrition, diet,and exercise (Golan & Crow, 2004), and parent approaches to food and nutritionshape children’s nutritional attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (Gable & Lutz, 2000). As

family rituals become engrained in the family’s daily patterns, they also affect andreflect the roles that family members form and reform throughout their life course.

Family roles. Through their patterned interactions and structures, family memberscreate and recreate roles in their family, which are associated with power in decision-

making. Power, defined as ‘‘the ability to change the behavior of other familymembers’’ (Cromwell & Olson, 1975, p. 5), is revealed in the roles various familymembers play, and the resulting structure of the family. Families may have patriarchal(centered on a powerful male), democratic (focused on more than one person, i.e.,

mother and father), child-centered (attendant to the child’s wishes), or dispersed(lacking clear leadership) power structures (Segrin & Flora, 2005).

Family roles and power structures impact the type of communication that occurs

between parents and children, and may be particularly apparent when negotiatingfood choices and other health behaviors (Tucker & Anders, 2001). Extreme parentalcontrol of eating practices, for example, can significantly negatively impact children’sability to regulate their need for food intake and engage in healthy eating habits

(Birch & Fisher, 1995; Johnson & Birch, 1994), while lack of parental control can have

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 257

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

a negative effect on children’s ability to develop an accurate sense of how to eathealthfully and manage this practice individually (Gable & Lutz, 2000).

Gable and Lutz (2000) found that parents who reported greater control of childeating also indicated their children watched more television and were engaged infewer extracurricular activities, further increasing their child’s likelihood of child-hood obesity. Children who watch television often request advertised foods (Lewis &Hill, 1998), requiring that parents negotiate the child’s needs and his/her requests(Harrison & Liechty, 2012). Specifically, Harrison and Liechty (2012) found childrenwhose parents restricted their television viewing ate fewer unhealthful foods, whereasparents’ coviewing television or instructing children on television behaviors wasrelated to higher intake of unhealthful foods. Further, supportive forms of influenceare often successful in encouraging health-promoting behaviors such as proper dietand nutrition whereas non-supportive forms of influence prompted health-compromising behaviors (Tucker & Anders, 2001). Although a patriarchal ormatriarchal model would unlikely allow for children to play a role in nutritiondecision-making, democratic, child-centered, and dispersed parenting styles wouldallow children to have more or less influence on purchasing decisions and mealtimechoices. Because power structures are often enacted through rule enforcement anddiscipline (Baumrind, 1991), it is also important to investigate the rules parentsestablish and administer in the family.

Family rules. Broderick (1993) postulated that rules can be organized into four levels:family paradigm (define overarching ideals of family; e.g., a competitive family),mid-range policies (direct behavior across different contexts; e.g., all memberscontribute to chores), metarules (establish boundary conditions; e.g., unless one issick, one must walk the dog each day), and concrete rules (specific rules aboutbehavior), which are of particular interest to this study. Concrete rules can be eitherregulative or constitutive. Regulative rules dictate desired or prohibited behaviorssuch as making one’s bed or eating vegetables, and constitutive rules offer aninterpretation of the meaning of certain behaviors such as eating fast food makes aperson unhealthy (Broderick, 1993). Overall, families generate and abide by concreterules regarding diet and nutrition, necessarily affecting the nutritional behaviors ofchildren; however, these rules can be negotiated in the family decision-makingprocess (Paugh & Izquierdo, 2009).

Family decision-making. A final aspect of the process of family communicationaddressed in this study is decision-making. Turner’s (1970) classic model of familydecision-making is a useful lens for broadly understanding the ways that familiesmake decisions. Turner (1970) stipulated a decision may be reached using one ofthree styles: consensus, accommodation, or de facto. In the consensus style, all familymembers must agree to the solution; for accommodation, some family membersacquiesce to the decision of another family member(s) such as the parent(s); and inthe de facto style, the situation makes the decision for the family (Turner, 1970).When making nutritional decisions, such as what food to purchase or what toprepare for dinner, families likely employ all of these styles of decision-making.

258 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

However, continual use of a particular type of decision-making style could haveprofound effects on the overall nutritional patterns of the family, and the childspecifically.

In summary, the family unit provides a context for investigating communicationbetween parents and children. Family rituals, roles, rules, and decision-makingaround nutritional choices can provide insight for understanding the challenges inpromoting positive health decisions and outcomes within families. Yet, wheninvestigating parent!child communication about health, it is imperative thatimportant societal and contextual factors are taken into account. In the currentstudy, we explore the interplay of family communication and contextual factorsthrough the ecological framework in an effort to understand the complexity ofparent!child communication about food and health. To that end, the followingresearch question is posited:

RQ: How does the ecological framework inform our understanding of parent!child communication about nutrition?

Method

Procedure

Participants were recruited from two counties in a Midwestern state. Recruitmenttook place at a family expo held by the community and a county health department(specifically, the offices of the Women Infants & Children program). Trained researchassistants approached parents and children at these sites and asked if they would bewilling to participate in the current project. In order to participate, participants hadto qualify as low-income, the child had to be between 8 and 10 years of age, and boththe parent and child had to complete the full interview.

Participants first completed consent and assent forms (for children). Theinterviews proceeded with a combined interview of both the parent and child,which typically lasted 15 to 20 minutes. Immediately after the combined interview,the parent and child completed separate interviews, which also typically lasted 15 to20 minutes. Upon completion of the interviews, parents were given a $15 gift card toa local grocery store.

Participants

A total of N"33 parents were interviewed with their children. Demographicinformation was recorded for the parents (i.e., adults), but not children. The averageage of adults was 35.26 years (SD"6.41 years). Most adult participants were female(N"31), with two males participating in the study. Most adult participants werewhite (n"14); other parents reported their race as black (n"6) or Hispanic (n"2);and other participants’ races were unidentified (n"9). Ten adult participants weremarried and nine were single (n "9); three participants were divorced; and 20participants did not provide their marital status. Almost half of the adult participants

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 259

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

(n "14) were unemployed at the time of the interview. Overall, parent participants

reported fairly good overall health (M "4.22, SD " .85) on a 1!5 scale (1 "not very

good, 5 "very good), an average overall diet (M "3.70, SD "8.22), and an average

level of physical activity (M "3.26, SD "1.29). Five participants reported a family

history of obesity.

Materials

Interview guides. The interview guide was developed from existing nutrition scalesand family communication open-ended items. The combined parent!child interview

guide asked participants to recall things they may have taught their children about

food (e.g., talking about consequences of consuming unhealthy foods) and whether

the parent followed through on the advice he or she gave to his/her child. Parents also

described their most recent trip to the grocery store and the previous week of meal

preparation. Throughout the discussion, parents were asked to describe how (and if)

they talked with their children during these episodes. Parents also discussed their

techniques for getting their child to eat more of his/her meals and for responding to

the child eating something the parent does not want them to eat. Finally, parents were

asked to recall a particularly memorable conversation about nutrition they may have

had with their child.During the child-only interview, children were asked about their level of

involvement with nutritional decisions in terms of grocery shopping and meal

preparation. Children also responded to questions about how they negotiate with

their parents to get to eat or to avoid eating certain foods, any nutritional behaviors

they kept hidden from their parents, parents’ techniques for getting them to eat more

or for responding to them eating something the parent did not want them to eat, and

what they have learned about nutrition from their parents. Finally, children were

asked to recall a particularly memorable conversation about food they had with their

parents.

Coding

Following completion of the interviews, the audiotapes were transcribed verbatim

and unitized with subject!verb pairings as the unit of analysis. First, four reviewers

evaluated the transcripts and identified key ideas that reflected the different levels of

the nutritional ecological model. They identified specific coding categories based on

their individual comprehensive evaluations of the transcript, and tentative categories

were discussed and revised by the reviewers (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Coding

categories were examined for their underlying meaning to form larger, representative

themes of the ecological model. Themes were compared for congruency, refined

until 100 percent agreement was attained, and then finalized by the research team

to ensure they adequately reflected the responses gathered during the interview

sessions.

260 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

Geospatial Analysis

In addition to interview data that reflected multiple levels of the ecological model,

geographic information system technology (GIS) data were also considered as a

strategy to examine the larger community level of the model. A beneficial tool for

analyzing food-availability patterns and general access to nutrition, GIS allows for

distinct locations to be mapped. This mapping is a visualization of a given area’s

nutritional environment; this allows one to identify geographic regions with limited

access to nutritional food and/or access to food with low nutritional value. In the

present article, county-level indices were used to assess the relative food environment

of the two Midwestern counties in which participants resided. These measures were

then compared with national averages to provide a general depiction of the food

environment within which participants of the given study lived, and offers a context

for drawing comparisons to other geographic locations ([State Name Removed]

Department of Technology, Management & Budget: Center for Shared Solutions and

Technology Partnerships, 2002; USDA, 2011).

Results

Findings were organized into three levels in line with the ecological framework

(Davison & Birch, 2001): (1) child factors, such as personal preferences and eating

habits; (2) family communication factors including negotiations, conversations about

food; and (3) external factors that included structural, situational, and environmental

factors.

Child Factors

Child factors were defined as intrapersonal factors that influence choices about food.

Factors such as the child weight status and susceptibility to weight gain were outside

the scope of this study. However, personal preferences about food were mentioned

when participants indicated children often had pickier tastes than their parents. For

example, one participant stated, ‘‘When she [my mom] makes spaghetti, I told her that

I don’t like mushrooms in it’’ (Child #31). Therefore, children took opportunities to

voice their personal preferences and some parents did try to accommodate ‘‘picky’’

children. Although the preferences of the child were often cited as a factor that

influenced food decision-making, parental preferences also affected these choices for

the entire family. For example, one father stated, ‘‘So with me, it’s been about being

healthy because I’ve been a vegetarian for six years. Her mom eats a lot of fast foods, so

(the child) has both sides of it’’ (Parent #9). Another parent participant pointed out

her preferences and how they affect her child’s nutrition by stating, ‘‘Usually he eats

what I eat, so if I don’t like something, he won’t like it’’ (Parent #16). In sum, while

children choices seem to guide some nutritional decisions, parental preferences were

more important in this sample.

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 261

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

Family Characteristics and Communication about Nutrition

The essential aspects of familial communication were often referenced withindiscussions of the family structure and the impact it has on healthy decision-making.Familial communication factors included memorable conversation, rules, and roles(child’s voice, parental role) within the family context.

Memorable conversations. We explored stories and anecdotes about food, since theyplay an important role in familial communication about nutrition. One major themeassociated with familial communication was stories about food. Some participantsdid share stories and anecdotes about their family. For example, an anecdote aboutfood from a parent dealt with his child’s first experience with nutritional decision-making. The participant stated, ‘‘Probably the first time I took her to Old CountryBuffet. . . . I told her to try a little bit of everything to see if she likes it or not. It wasthe first time I tried to get her to really try something’’ (Parent #14). This parent’sstory gives a glimpse into the approach parents take in helping their children establishtheir own personal preference. To further explore stories and roles within the family,we asked the participants about memorable messages or those messages that peopleremember and consider influential to their future behavior (Knapp, Stohl, &Reardon, 1981). Overall, the majority of participants could not recall memorablemessages about food. For example, one participant said, ‘‘Well, we don’t talk aboutanything like food’’ (Parent #12). When a child participant was asked whether his orher family had conversations about food, the participant responded, ‘‘No, only inschool where we do recycling and learn about the color and feel of fruit’’ (Child #14).In other cases, the participants could recall conversations about food had happened,but could not remember specifics. For example, one participant stated, ‘‘I don’t knowwhat they say, but they do say stuff ’’ (Child #7). This finding suggests that childrencannot readily recall or retain parental messages or conversations about food.

Although participants indicated family conversations about food did occur, therewas a limited amount of discussion about food when children were making healthynutritional decisions. Instead, these negotiations usually took more of a reactivestance either as a response to a question or because the child was disobeying. Forexample, when asked what his or her parent says when they choose healthy food, twochildren replied similarly, ‘‘They don’t say anything’’ (Child #13), and ‘‘Yeah, theydon’t say anything really’’ (Child #15).

When asked about discussions about nutrition during meal times, mostparticipants indicated that while conversations usually took place, they were mostlyabout their daily activities and not centered on food. For example, one parent stated,‘‘We talk about what they do during the day, and talk about going to the movies andstuff ’’ (Parent #27). When participants indicated they did talk about nutrition atdinner, it was often in reference to how the food tasted rather than the ingredients.For example, one participant stated, ‘‘Well, usually every night we go, ‘Wow this tastesgood’ or ‘Ew, I don’t like this’’’ (Child #9). In summary, participants recalled fewstories and conversations about communication about food and nutrition. Thisfinding does not necessarily mean that communication about food was lacking,

262 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

instead it may suggest the importance of food-centric rules and negotiations. Ifparents and children did not recall general stories, they may still have food rulesimpacting choices and behaviors within the family.

Rules. Food-centric rules were often discussed among participants as being essentialfunctions of their family structure and lifestyle, including both regulative andconstitutive rules. Regulative rules that influenced nutritional choices varied betweenfamilies, and were often associated with food restrictions, or with rewards andpunishments. First, restrictive rules often dealt with strict restrictions or guidelinesthe child must follow without discussion. For example, one parent stated, ‘‘There’s nojunk food in the morning. You have to eat breakfast. Junk food is limited. And fruitsnacks are considered junk food early in the morning’’ (Parent #32). On the otherhand, a more lenient parent said, ‘‘In general I don’t like them to have a lot of junkand processed foods. Still on occasion we eat it, I don’t restrict them all the time’’(Parent #7).

In addition to restrictive regulative rules, there were also regulative rules that werecoupled with rewards or punishments. Rules that were not followed were often metwith punishments that typically took the form of food restrictions. For example, oneparent stated, ‘‘They can’t have their dessert unless they eat their dinner’’ (Parent #7).One child stated, ‘‘I can’t go outside until I finish my plate’’ (Child #23). Rules withrewards were also used to influence children’s eating behaviors within a number offamilies. For example, one participant said, ‘‘I do give them challenges too; ifeveryone eats all their food on their plate you’ll get treats or desserts afterwards’’(Parent #31). Another parent provided an example of a rule that she reminds herkids of often, ‘‘If you guys eat a good dinner, then we’ll do a treat’’ (Parent #10).

Participants also spoke about various constitutive rules that gave meaning tonutritional behaviors. For example, one parent said, ‘‘If you don’t eat the right typesof food, you are going to end up getting fat’’ (Parent #8). Another parent’s expressionof constitutive rules provides a contrast between the meanings attached to differenttypes of foods: ‘‘Fruits and vegetables are good for you; candy and doughnuts are notgood for you’’ (Parent #13). Children also referenced constitutive rules aboutnutrition. For example, one child said his or her parent told him/her, ‘‘that if you eattoo many sweets and bad food that you will be unhealthy’’ (Child #13). The childnoted his/her parent attached negative physical outcomes to the consumption ofunhealthy foods, saying that if you eat unhealthily, ‘‘you can get big and stuff, andweak’’ (Child #13). The discussion of rules also expanded to the negotiations of therules governing food-decision-making within the family structure.

Negotiations. Negotiations stemming from such rules often involved the child askingfor something he or she might not be able to have normally. For example, one parentdiscussed a negotiation with her child about choosing food at restaurants. Theparticipant stated, ‘‘They’ll be like, ‘Mom can I get this?’ And I’ll be like, ‘Well, I don’treally care, but maybe it’s a little bit much, it’s a lot of food for your little body don’tyou think?’’’ (Parent #8). Although there was a negotiation, the structures of thefamilies often lead to the parent dominating the discussion and determining the

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 263

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

outcome, thus leading to the use of an accommodating decision-making style.

Another example of this was discussed when a child participant was explaining

negotiations about meal times. The participant stated, ‘‘If they say not to eat it,

I don’t eat it. If they tell me to eat it and I have no choice, I usually just sit there and

try to try it. If I don’t like it, I just kind of sit there’’ (Child #9).While negotiations within some families often reflected the accommodation style

of decision-making, other families’ decision-making style was closer to a consensus

style that allowed for more input from the children during these discussions. These

types of discussions often ended in an agreement between the parent and the child.

For example, when discussing meal times with the family, one participant stated,

‘‘I ask them what they want then we agree on something’’ (Parent #13). Thus, in

some cases, a consensus style of decision-making about food was adopted by parents

rather than an accommodation style. The parents’ negotiations were in part

motivated by what they perceived as their role in the child’s nutrition.

Family roles. Throughout the interviews, parent participants consistently alluded totheir roles within their unique family structure. The parents often talked about their

responsibility to educate their children about nutrition and making healthy choices.

This education was provided through nutritional advice for children. Most parents

indicated that the advice they most frequently suggest to their children is to eat fruits

and vegetables, and stay away from sugar and snacks. For example, one participant

stated she often reminds her child about: ‘‘Making good choices about what you

eat and trying to encourage more fruits and vegetables’’ (Parent #9). Another

parent repeated this statement by saying, ‘‘Just try to eat fruits and vegetables is

really it. Just eat a balanced diet and sweets aren’t good for your teeth and stuff ’’

(Parent #10).Although some parents believe they serve as positive role models by following their

own advice about nutrition, others admitted they might not be providing a good

example for healthy decision-making. One participant stated, ‘‘Milk is a must, even

though I don’t drink milk myself, I still encourage them to drink it’’ (Parent #32).

Another participant noted her own health issues and trying to lead her children down

a different path. She said, ‘‘Just don’t follow my footsteps. Or, you guys try to be

healthy, you know, and eat healthy. And then maybe you won’t have the same

problems I have right now [hypertension and diabetes]’’ (Parent #41).Although the rules and restrictions within each family seemed to determine the

child’s role, most children had some level of input in nutritional decision-making.

Participants indicated the child would occasionally help parents with grocery

planning and shopping, but this responsibility fell primarily on the parents. For

example, one participant stated, ‘‘If it’s something I would normally buy and there’s a

choice, then sometimes [they have input], but they don’t get to say ‘I want this’ and I

buy it automatically’’ (Parent #7). On the other hand, another parent said, ‘‘We talk

about what we are going to eat for the week and what he wants to eat for the week, I’ll

let him pick some sweets out like cupcakes’’ (Parent #27).

264 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

Community and Societal Factors

Data from parental interviews and the GIS analysis revealed that community factorsincluding SES and accessibility issues were relevant and influential to parent!childcommunication about nutrition.

SES. Economic considerations had a large impact on food decision-making, ashousehold income was a deciding factor in participants’ choices about food.Choices made at the grocery store were often impacted by immediate monetaryavailability. For example, one participant noted: ‘‘We get the sales papers and wecircle the stuff that’s on sale. And we normally go to Wal-Mart and match our pricesthere. We look for stuff that’s easy to cook, seeing that I work so many hours’’(Parent #32). Another participant indicated, ‘‘When it comes time for dinnersI actually cook a meal that’s usually a last minute thing or it depends on the foodstamps we have left for the month. So the food we get all depends on the budget’’(Parent #14).

Economic status also affected how often participants could eat at restaurants. Forexample, one child participant stated, ‘‘Sometimes my mom says if we have themoney we can go to a restaurant, but we don’t do that anymore’’ (Child #16).Another participant stated, ‘‘They pretty much know we’re eating at home because Ibe broke, except for pay days, then we go out to eat. Other than that, it’s pretty muchhome’’ (Parent #12). Financial influences on dietary habits, therefore, can reflect a defacto style of decision-making, wherein the situation (i.e., limited financial resources)determines decisions about food choices.

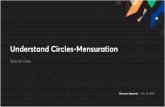

Food accessibility. GIS data provided visualizations of participants’ residences withinthe given area and maps of the nutritional environment. Results were aggregatedwithin three major food environment descriptors: food choices, health and well-being, and community characteristics, as identified by the Economic Research Service(2011). Selections from each of these three categories were highlighted and discussedcomparatively, using the two Midwestern counties where participants were recruitedand resided (County A and County B).

In the analysis, measures of food choices referred to general rates of food accesspoints available to participants. General food environment characteristics, thenumber of fast food restaurants, grocery stores, farmer’s markets and WIC authorizedstores (all per 1,000 people) per county were used as indices, revealing the twocounties had fewer grocery stores, WIC authorized grocery stores, and farmers’markets compared to the national average (see Figure 1). In other words, access tohealthy food options was limited in participants’ counties.

Participants did talk about these food environment characteristics as they relatedto decision-making. While participants were not specifically asked about thegeographical information, the topic did come into light as they discussed restaurantand shopping choices. For example, when asked about the restaurant choice, onechild mentioned: ‘‘Yeah, well, when we pick the restaurant we’ll pick like the closestrestaurant’’ (Child#7). Others talked about choices related to their SES such as

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 265

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

WIC Authorized Stores

0.00

0.050.10

0.150.20

0.250.30

Location

Num

ber

of S

tore

s pe

r 10

00 P

eopl

eNational Mean

County A

County B

Fast Food Restaurants

0.00

0.20

0.40

0.60

0.80

1.00

Location

Num

ber

of S

tore

s pe

r 10

00 P

eopl

e

National Mean

County A

County B

Grocery Stores

0.000.05

0.100.15

0.200.25

0.30

Location

Num

ber

of S

tore

s pe

r 10

00 P

eopl

e

National Mean

County A

County B

Farmer's Markets

0.00

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

Location

Num

ber

of S

tore

s pe

r 10

00 P

eopl

e

National Mean

County A

County B

Figure 1. WIC authorized grocery stores, and farmers markets compared to the nationalaverage.

266 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

picking the restaurant where children could eat for free (Parent #32). Finally, oneparticipant talked about going out of their community to shop for cereal at a private,organic grocery store (Parent #15).

The lack of food shopping choices not only inhibits healthy food selections(Turrell, Hewitt, Patterson, Oldenburg, & Gould, 2002), but likely impacts parents’decisions to engage them in fruitful discussions about nutrition. A parent whorecognizes the low food availability is unlikely to promote foods that are not readilyavailable or affordable with their children. On a positive note, the number of fastfood restaurants, while certainly present, is lower than the national average, as areobesity rates among young children; adult obesity rates, however, are much higherthan the national average.

Discussion

Over the last ten years, the dialogue about childhood obesity has been at the forefrontof national debate, with programs such as the First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Movecampaign (letsmove.gov) encouraging children to be active in order to curb obesityrates. Childhood represents a critical time wherein prevention efforts can effectivelyreduce lifetime obesity rates through positive nutritional choices within and outsidethe family structure (Barlow, 2007). Parents are central to these efforts because theyplay a key role in the nutritional choices of their children. Research has stressed theimportance of parental modeling and behaviors regarding nutrition (e.g., parentalfeeding practices, Ventura & Birch, 2008) in establishing a healthy diet for children.These parenting practices are even more relevant in low-income families, who bearthe brunt of childhood obesity rates (Hedley et al., 2004). The current study providedinsights into low-income family nutritional practices based on interviews withparents and children from low-income families and a community level analysis oftheir nutritional environment. Parents and children answered questions about theirrules, roles, and rituals associated with grocery shopping, meal preparation and otherfood-related activities, while the GIS data provided information about grocery stores,farmers markets, and other descriptive information. The findings have importanttheoretical implications, including expanding the ecological model into parent!childnutrition contexts, and practical implications, including interventions regarding foodrules and strategies for engaged decision-making.

Theoretical Implications: Ecological Insights about Parent!Child Nutrition

This study investigated parent!child communication about nutrition from anecological framework, and demonstrated the model’s utility in developing anunderstanding of the range of factors that impact nutritional decision-making. Themulti-level composition of the ecological model revealed a range of factors thatultimately impact children’s nutrition behaviors. It is clear that different levels offactors need to be taken into account to effectively understand and address children’snutrition. Parents and children do not simply live in a household; they are also

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 267

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

members of a community and are limited by their neighborhood choices andfinancial situation.

The ecological model provides a lens to make sense of the complex influences onnutrition and nutritional behaviors, both globally and specifically. When investi-gating the ecological model globally, findings from the current study show that thefluidity between levels impacts parent!child communication about nutrition.Parents look at the impact of all ecological levels as they consider child preferences,nutrition information, financial resources, and food availability in their decisionsabout what to purchase, prepare, and ultimately eat. The levels of the ecologicalmodel are interconnected as illustrated by parent comments about challenges withpicky children, family rules and roles, structural issues like lack of financialresources, and community barriers like lack of affordable fruits and vegetablesin local supermarkets. These findings clearly demonstrate that a comprehensiveeffort addressing nutrition should include several levels of intervention. Policychanges and structural improvements need to complement public communicationcampaigns.

Examination of specific levels of the ecological model also provides key insightsinto the communication process. For example, when considering the family factorlayer where parent!child interaction occurs, we see that parents did not necessarilyreinforce the nutritional messages they gave to their children (i.e., parent telling thechild to drink milk when the parent did not do so). Although some parents identifiedas nutritional role models because they provided their children with advice andinstructions on healthy food choices, many parents acknowledged they were flawedrole models. Parents admitted to a ‘‘do as I say, not as I do’’ approach, which ispotentially problematic as children examine parents’ behavior as role models for whatis and is not acceptable behavior (Andrews et al., 2010). However, given that resultsfrom the current study suggest that children do not carefully attend to the verbalmessages sent by parents, these discrepancies between communication and behaviormay not have had a significant impact on these children’s habits. Future research onthe family factor layer should tease out the ways children reconcile contradictoryparental instructions and behaviors, and the effects of contradicting messages onchildren’s nutrition and health behaviors. Yet, as we discuss the key communicationintervention areas in the following section, it is important to recognize that, althoughcommunication is an important influence on child nutrition decision-making, itcannot compensate for a lack of adequate nutritional resources.

Improving Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition

The current study’s findings suggest that, because parents rarely talk directly withchildren about nutrition, there is potential to improve parents’ communicationhabits in this context. Overall, the study revealed limited communication aboutnutrition with children. When communication did occur, parents most often choseto simply verbally direct children’s eating behaviors, rather than choosing morecommunication patterns. For example, parents made meal and snack decisions

268 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

without much interaction with their children. Furthermore, little or no efforts weremade to engage the children or use mealtimes as nutritional education tools. Bothparents and children had difficulty recalling memorable messages related to food.Perhaps food is a taboo topic and is not often discussed (Petronio, 2002), or thediscussion is constrained by external factors such as limited funds and strenuousschedules. If resources are scarce, choice is limited by necessity and communication,and input about food selection and preparation would naturally be limited.

However, because of this relative lack of communication about nutrition, there arevast opportunities to work with parents and children to improve nutrition andcommunication about food decision-making. Avenues for communication interven-tions include engaging parents and children in shared decision-making activities andidentifying appropriate food parameters and family eating practices.

Strategies for engaged decision-making. Involving children in nutritional decision-making improves their health behaviors and health outcomes (Epstein, Valoski,Wing, & McCurley, 1994; Tinsley, Markey, Ericksen, Ortiz, & Kwasman, 2002). Forexample, Tinsley and colleagues (2002) found that families with an authoritativeparenting style, where children are included in some decision-making, reported morehealthy eating behaviors than those with other parenting styles. In a long-term fieldexperiment with 158 families, Epstein et al. (1994) found that an intervention thattargeted both parents and children to improve shared dietary decision-makingproduced the greatest dietary and weight improvements*at five and ten yearintervals after the program was completed*compared to either child-only or non-targeted interventions. That is, previous research suggests that the greatest changes ineating habits occur when parents and children work together and share in theresponsibility for developing healthy eating habits.

Given that shared parent!child decision-making about eating improves healthyeating behaviors in children, future interventions should continue to utilize thisapproach and augment such programs with more concrete suggestions for parent!child communication interactions. This communication focus for family-basednutrition interventions could provide example dialogues or scripts for conversationsabout nutrition and provide information about consensus-style decision-making.Such communication elements may improve parents’ ability to implement changeslike involving children in nutritional decisions like grocery lists, simple foodpreparation, and making healthy snack choices. Additionally, although mediamessages were not a focus of the current study, past research demonstrates theimportant relationship between advertising messages and childhood obesity (e.g.,KFF, 2004); thus, interventions could also teach parents to help children criticallyengage with media messages.

Food rules. While parents did not necessarily communicate with their children abouthealthy food choices, they routinely applied food-related rules. For instance, food wasoften used as a reward, or punishment tactic, as parents allowed snacks or treats forcompleting chores, getting good grades, and behaving appropriately. Restrictions onfood were used for punishment or to account for limited financial resources. In

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 269

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

addition, the ‘‘eat everything on your plate’’ rule was also applied by some parents in

the study. Although research on food rules and restriction is complex, generally,

overly permissive practices are linked to higher obesity rates and food restriction also

has a negative impact on child health (Barlow, 2007). These findings are likely not

limited to low-income populations, as families from all levels of SES often use food as

a reward and punishment (Eppright, 1969). Perhaps interventions should model the

types of rules that allow children to develop healthy nutrition-related decision-

making styles, rather than rules that place too much control over children’s eating

habits. For example, an intervention may model meal preparation rules that

encourage parents to have primary input on the main elements of a meal, but allow

children to select a side dish, or the ingredients in a salad.

Limitations and Future Research

Although the findings from the current study advance empirical and practical

knowledge on parent communication and child health habits, this study is not

without limitations. First, the present study drew on a relatively small number of

dyadic interactions from low-income populations, which are relatively difficult to

reach. However, many of these findings, particularly using food for rewards and

punishments, are likely relevant to all SES levels. Future research should investigate

the varying approaches parents from different SES levels take to educate and socialize

their children’s nutritional decision-making. Since regional, ethnic, religious, and

educational differences likely co-exist with varying levels of SES, an intercultural

approach to the study of parent!child communication about food also may be

fruitful.Next, the sample primarily included mothers, rather than fathers, as participants.

While mothers are typically more influential when it comes to children’s nutritional

choices (Scaglioni, Salvioni, & Galimbert, 2008), fathers still play an important role

in shaping the family culture and communication about nutrition. Indeed, the way

fathers communicate with their children*both daughters (Punyanunt-Carter, 2008)

and sons (Floyd & Morman, 2000)*creates a communication environment that

influences children’s behaviors. Thus, future research should investigate the role of

fathers’ communication in children’s current and future decision-making about

nutrition and health.Furthermore, expanding upon the ecological investigation of family nutrition talk,

future research should investigate the role of food (in)security, as it is a relevant

factor in shaping family nutritional decisions. Food security exists ‘‘when all people at

all times have access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food to maintain a healthy and

active life’’ (World Health Organization, 2012), and those who live in food-insecure

households likely experience communication about food differently from those who

live in food secure contexts. Future research should investigate the ways in which

family talk depends on the household food security and perceptions of food security

within the family. Findings may point to useful interventions for families with food

270 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

insecurity, and provide them with tools for managing and explaining food, nutrition,

and health to their children.

Conclusion

This study provided information about current family communication practices

related to nutrition, and placed those interactions within an ecological framework to

understand the various levels of influence operating to affect childhood nutrition

behaviors. This study suggests many families often do not have conversations about

nutrition, and the communication about nutrition that does occur is often focused

on structural constraints on dietary practices or negotiation of concrete rules

regarding dietary choices. Thus, future interventions need to address these structural

and environmental challenges if they are to impact positively the nutritional choices

and overall health of families. By creating an at-home environment where parents and

children communicate about food choices, nutrition, and meal preparation, future

interventions can have a substantial, positive impact on parents’ and children’s

dietary habits.

Acknowledgements

This project has been partially funded with Federal funds from USDA’s Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program*Nutrition Education program by way of the

Michigan Nutrition Network at Michigan State University Extension in partnership

with the Michigan Fitness Foundation. This material is based upon work supported

in part by the Michigan Department of Human Services, under contract number

ADMIN-10-99010. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations

expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

reflect the view of Michigan State University or the Michigan Department of Human

Services.

Note

[1] Childhood overweight and obesity are defined using BMI values that are adjusted for age and

gender. The overweight classification is used for those in the 85th!95th percentile; the obese

classification is used for those in the 95th percentile and above (Barlow, 2007).

References

Andrews, K., Silk, K., & Eneli, I. (2010). Parents as health promoters: A theory of planned behaviorperspective on the prevention of childhood overweight and obesity. Journal of HealthCommunication, 15, 95!107. doi:10.1080/10810730903460567

Barlow, S. E. (2007). Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment,and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: Summary report. Pediatrics,120, S164!S192. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2329C

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 271

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use.Journal of Early Adolescence, 11, 56!95. doi:10.1177/0272431691111004

Baxter, L. A., Bylund, C. L., Imes, R. S., & Scheive, D. M. (2005). Family communicationenvironments and rule-based social control of adolescents’ healthy lifestyle behaviors. TheJournal of Family Communication, 5, 209!227. doi:10.1207/s15327698jfc0503_3

Baxter, L. A., & Clark, L. A. (1996). Perceptions of family communication patterns and theenactment of family rituals. Western Journal of Communication, 60, 254!268. doi:10.1080/10570319609374546

Birch, L. L., & Fisher, J. A. (1995). Appetite and eating behavior in children. Pediatric Clinics ofNorth America, 42, 931!952.

Borra, S. T., Kelly, L., Shirreffs, M. B., Neville, K., & Geiger, C. J. (2003). Developing healthmessages: Qualitative studies with children, parents, and teachers help identify communica-tions opportunities for healthful lifestyles and the prevention of obesity. Journal of theAmerican Dietetic Association, 103, 721!728. doi:10.1053/jada.2003.50140

Broderick, C. B. (1993). Understanding family processes: Basics of family systems theory. NewburyPark, CA: Sage.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Researchperspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723!742. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

Cheadle, A., Psaty, B., M., Curry, S., Wagner, E., Deihr, P., Koepsell, T., & Kristal, A. (1991).Community-level comparisons between the grocery store environment and individualdietary practices. Preventative Medicine, 20, 250!261. doi:10.1016/0091-7435(91)90024-X

Cohen, S., Gottlieb, B. H., & Underwood, L. G. (2000). Social relationships and health. In S. Cohen,L. G. Underwood, & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention:A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 3!25). New York: Oxford Press.

Cromwell, R. E., & Olson, S. (1975). Power in families. New York: Wiley.Davison, K. K., & Birch, L. L. (2001). Childhood overweight: A contextual model and

recommendations for future research. Obesity Reviews, 2, 159!171. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00036.x

Economic Research Service. (2011). Food environment atlas source data [data file]. Retrieved fromhttp://ers.usda.gov/foodatlas/downloads/data_download.xls

Epstein, L. H., Valoski, A., Wing, R., & McCurley, J. (1994). Ten-year outcomes of behavioralfamily-based treatment for childhood obesity. Health Psychology, 13, 373!383. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.13.5.373

Eppright, E. (1969). Eating behavior of pre-school children. Journal of Nutrition, 1, 16!19.Flora, J. A., & Schooler, C. (1995). Influence of health communication environment on children’s

diet and exercise knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. In G. L. Kreps & D. O’Hair (Eds.),Communication and health outcomes (pp. 187!213). Cressfilt, NJ: Hampton Press.

Floyd, K., & Morman, M. T. (2000). Affection received from fathers as a prediction of men’saffection with their own sons: Tests of the modeling and compensation hypothesis.Communication Monographs, 67, 347!361. doi:10.1080/03637750009376516

Gable, S., & Lutz, S. (2000). Household, parent, and child contributions to childhood obesity.Family Relations, 49, 293!300. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00293.x

Galvin, K. M., Bylund, C. L., & Brommel, B. J. (2004). Family communication: Cohesion and change(6th ed). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitativeresearch. New York: Aldine.

Golan, M., & Crow, S. (2004). Parents are key players in the prevention and treatment of weight-related problems. Nutrition Reviews, 62(1), 39!50. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00005.x

Guillame, M., Lapidus, L., & Lambert, A. (1998). Obesity and nutrition in children: The BelgiumLuxemburg child study IV. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 52, 323!328. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600532

272 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

Harrison, K., & Liechty, J. M. (2012). U.S. preschoolers’ media exposure and dietary habits: Theprimacy of television and the limits of parental mediation. Journal of Children and the Media,6, 18!36. doi:10.1080/17482798.2011.633402

Harrison, K., & Marske, A. L. (2005). Nutritional content of foods advertised during the televisionprograms children watch most. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 1568!1574.doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.048058

Hedley, A. A., Ogden, C. L., Johnson, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Curtin, L. R., & Flegal, K. M. (2004).Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults 1999!2002.Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 2847!2850. doi:10.1001/jama.291.23.2847

Heitmann, B. L., Lissner, L., Sorenson, T. I., & Bengtsson, C. (1995). Dietary fat intake and weightgain in women genetically predisposed for obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 61,1213!1217. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7762519

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation [KFF]. (2004, February). The role of media in childhoodobesity. Issues Brief. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org.

Hill, J. O., & Peters, J. C. (1998). Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science, 280,1371!1374. doi:10.1126/science.280.5368.1371

Institute of Medicine. (2005). Food marketing to children: Threat or opportunity? Washington, DC:National Academies Press.

Johnson, S. L., & Birch, L. L. (1994). Parents’ and children’s adiposity and eating style. Pediatrics, 94,653!660. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/94/5/653.short

Jones, D. J., Beach, S. R., & Jackson, H. (2004). Family influences on health: A framework toorganize research and guide intervention. In A. L. Vangelisti (Ed.), Handbook of familycommunication. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Jorgenson, J., & Bochner, A. P. (2004). Imagining families through stories and rituals. InA. Vangelisti (Ed.), Handbook of family communication (pp. 513!538). Mahwah, NJ:Erlbaum.

Knapp, M., Stohl, C., & Reardon, K. (1981). Memorable messages. Journal of Communication, 31,27!41. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1981.tb00448.x

Koerner, A. F., & Fitzpatrick, M. A. (2002). Understanding family communication patterns andfamily functioning: The roles of conversation orientation and conformity orientation.Communication Yearbook, 26, 37!69.

Lewis, M. K., & Hill, A. J. (1998). Food advertising on British children’s television: A contentanalysis and experimental study with nine-year-olds. International Journal of Obesity, 22,206!214. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0800568

[State Name Removed] Department of Technology, Management & Budget: Center for SharedSolutions and Technology Partnerships. (2002). [State Name Removed] Geographic DataLibrary [Collection of GIS Data Files] Retrieved from [website removed].

Paugh, A., & Izquierdo, C. (2009). Why is this a battle every night? Negotiating food and eating inAmerican dinnertime interaction. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 19, 185!204. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1395.2009.01030.x

Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of privacy: Dialectics of disclosure. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.Punyanunt-Carter, N. M. (2008). Father!daughter relationships: Examining family communication

patterns and interpersonal communication satisfaction. Communication Research Reports, 25,23!33. doi:10.1080/08824090701831750

Ryan J. (2001). ‘Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory’. Retrieved January, 9, 2012 fromhttp://pt3.nl.edu/paquetteryanwebquest.pdf.

Scaglioni, S., Salvioni, M., & Galimbert, C. (2008). Influence of parental attitudes in thedevelopment of children eating behavior. British Journal of Nutrition, 99, S22!S25.doi:10.1017/S0007114508892471

Segrin, C., & Flora, J. (2005). Family communication. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Parent!Child Communication about Nutrition 273

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3

Tinsley, B. J., Markey, C. N., Ericksen, A. J., Ortiz, R. V., & Kwasman, A. (2002). Health promotionfor parents. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 5. Practical issues inparenting (2nd ed., pp. 311!328). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tucker, J. S., & Anders, S. L. (2001). Social control of health behaviors in marriage. Journal ofApplied Social Psychology, 31, 467!485. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02051.x

Turner, R. (1970). Family interaction. New York: Wiley.Turrell, G., Hewitt, B., Patterson, C., Oldenburg, B., & Gould, T. (2002). Socioeconomic differences

in food purchasing behavior and suggested implications for diet-related health promotion.Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 15, 355!64. doi:10.1046/j.1365-277X.2002.00384.x

United States Department of Agriculture: Economic Research Service. (2011). Food environmentatlas source data [data file]. Retrieved from http://ers.usda.gov/foodatlas/downloads/data_download.xls.

Ventura, A. K., Birch, L. L. (2008). Does parenting affect children’s eating and weight status?International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5, 15!26. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-5-15

Ver Ploeg, M., Breneman, V., Farrigan, T., Hamrick, K., Hopkins, D., Kaufman, P., et al. (2009).Access to affordable and nutritious food*measuring and understanding food deserts and theirconsequences: Report to Congress. Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/AP/AP036/

Viswanath, K., & Bond, K. (2007). Social determinants of nutrition: Reflections on the role ofcommunication. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 39, S20!S24. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2006.07.008

Walen, H. R., & Lachman, M. E. (2000). Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends:Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and PersonalRelationships, 17, 5!30. doi:10.1177/0265407500171001

Wolfe, W., & Campbell, C. C. (1993). Food pattern, diet quality, and related characteristics of schoolchildren in New York State. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 93, 1280!1284.doi:10.1016/0002-8223(93)91955-P

Wolin, S. J., & Bennett, L. A. (1984). Family rituals. Family Process, 23, 401!420. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1984.00401.x

World Health Organization. (2012). Trade, foreign policy, diplomacy and health: Food security.Retrieved from http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story028/en/

274 K. Ndiaye et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

issou

ri Co

lum

bia]

at 0

9:08

11

Sept

embe

r 201

3