united states department of commerce

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of united states department of commerce

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF INDUSTRY AND SECURITY

Washington, D.C.

IN THE MATTER OF

SECTION 232 NATIONAL SECURITY INVESTIGATION OF IMPORTS OF ALUMINUM

)))))))))))

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

WRITTEN COMMENTS OF US MAGNESIUM LLC

Jennifer Lutz ECONOMIC CONSULTING SERVICES, LLC 2001 L Street, NW, Ste. 1000 Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 466-7720 Economic Consultant for US Magnesium LLC

Stephen A. JonesBenjamin J. Bay KING & SPALDING LLP 1700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20006-4706 (202) 737-0500 Counsel for US Magnesium LLC

June 23, 2017

I. INTRODUCTION

On April 26, 2017, the Secretary of Commerce initiated an investigation under Section 232 of

the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as amended, 1 for the Department of Commerce ("Commerce") to

determine the effects on the national security of imports of aluminum. On May 9, 2017, Commerce

published a Federal Register notice stating that it would conduct a public hearing on June 22, 2017,

and that written comments should be filed by June 29, 2017.2 Pursuant to Commerce's notice, US

Magnesium LLC ("US Magnesium") submits the following comments.

II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

US Magnesium is headquartered in Salt Lake City, UT, and has its production facility on

the western shore of the Great Salt Lake in Rowley, UT. The only remaining U.S. producer of

commercial quantities of primary magnesium, US Magnesium directly employs about 440

people and indirectly employs hundreds more. As such, it is the largest and most important

supplier of magnesium to U.S. companies producing aluminum alloys. Virtually all aluminum

alloys contain magnesium, which provides critical hardening properties to aluminum alloys. All

of these alloys are important for the aluminum industry and therefore critical to the health of the

national economy. Because almost all aluminum alloys require magnesium, and because the

domestic manufacture of products made from aluminum alloys is critical to U.S. national

security, the domestic production of magnesium is also critical to U.S. national security.

I 19 U.S.C. § 1862.

2 Bureau of Industry and Security, Notice of Request for Public Comments and Public Hearing on Section 232 National Security Investigation of Imports of Aluminum, 82 Fed. Reg. 21509 (May 9, 2017). A second notice was subsequently issued changing the deadline for the submission of written comments to June 23, 2017. Bureau of Industry and Security, Change in Comment Deadline for Section 232 National Security Investigation of Imports of Aluminum, 82 Fed. Reg. 25597 (June 2, 2017).

288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

In addition, magnesium is required for the production of other military-critical products,

such as steel, nodular iron, titanium, beryllium, and zirconium. Magnesium is also used directly

as a component in illumination and countermeasure flares, heater packets, and aerospace castings

for the military. Domestic production of magnesium is therefore critical to the ability of

Department of Defense ("DOD") to source the material needed for these products.

Magnesium is an import-sensitive material, and US Magnesium and its predecessor,

Magnesium Corporation of America, have been combating dumped and subsidized imports of

pure, alloy, and granular magnesium for many years. The Department of Commerce imposed

antidumping duty orders on imports of magnesium from China in 1995, 2001, and 2005. Those

orders, however, have not eliminated the adverse impact of China on US Magnesium or the

global magnesium market. Massive overcapacity in China has depressed markets worldwide,

diverting magnesium to the relatively higher prices available in the United States. China

produces over 85 percent of global magnesium requirements and has the capacity to supply more

than 100 percent of global demand. With capacity utilization rates under 60%, Chinese excess

capacity, overproduction, and pricing practices have destroyed the formerly vibrant magnesium

industries of Canada, Japan, and Europe, which no longer exist. Now, the U.S. industry is in

danger. Twenty years ago, there were three domestic primary magnesium producers with

nameplate capacity of 168,000 MT. Today, only US Magnesium remains. In 2006, Canada had

123,000 MT of primary magnesium capacity. Today, it has none. New capacity continues to be

installed in China, with a massive new production facility in Qinghai province coming on line

just this year. That facility has been commissioned to produce 100,000 tons per year, which

constitutes, by itself, almost enough capacity to supply the entire U.S. market.

-2-288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

US Magnesium is adversely affected by imports of pure, alloy, and granular magnesium

from Israel, Russia, and Turkey, among other countries. Imports from Russia and Turkey have

increased significantly in recent months. In addition, other product forms, such as secondary

alloy magnesium, magnesium scrap, and magnesium reagents for steel production are entering

the United States in increasing volumes from many countries and taking market share from US

Magnesium. These additional volumes have resulted in price declines that are harming US

Magnesium's financial condition, employment, and ability to invest in capacity to supply the

U.S. market. While US Magnesium has recently invested [ ] in the

equipment needed to expand its capacity, it has not been able to utilize this capacity due to

adverse market conditions. The company cannot continue to invest in maintaining or adding

additional capacity to supply the aluminum industry without assurance that it will be able to

operate profitably in the United States. In fact, without a significant improvement in conditions,

it [ ] produce magnesium in the United States.

US Magnesium believes that the health of the domestic aluminum industry is critical to

national security, and as such, the industry should be granted relief Likewise, US Magnesium

believes that the domestic magnesium industry is critical to national security. Accordingly, US

Magnesium requests that the Department of Commerce determine that imports of magnesium

threaten to impair the national security of the United States and impose trade relief to ensure that

the U.S. magnesium industry can survive and grow.

- 3 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

Ill. BACKGROUND

A. Overview of Magnesium Production in the United States

The magnesium industry has been important to the national security of the United States

since its inception. 3 The first magnesium plants were built in the United States during World

War I by General Electric, Dow Chemical, American Magnesium Company, and others.

Demand declined after the war, and by the late 1920s, only Dow continued production. That

changed when the United Stated entered World War II. Dow continued production, but the

Federal government established thirteen new magnesium plants to meet the military's need. By

the end of World War II, U.S. production capacity was 291,000 tons per year. Much of that

capacity was taken off line after World War II, but production was again revived during the

Korean War. After the Korean War, Dow operated its plant in Freeport, Texas and a

government-owned plant in Velasco, Texas at full capacity to build a government stockpile-

highlighting the strategic importance of magnesium to the military. This stockpile was gradually

depleted and eventually terminated in 1975, making the United States completely reliant on the

domestic magnesium industry to meet any increased demand in times of military action or

national emergency.

Dow's business focus shifted in the early 1970's, and it eventually closed the Velasco

plant and operated only the Freeport plant. Alcoa entered the magnesium industry in the early

1970's, opening Northwest Alloys in Addy, Washington in 1976. National Lead Industries

operated a plant on the shore of the Great Salt Lake and commenced magnesium production

there in 1972. In 1980, AMAX, Inc. acquired the National Lead Industries plant, brought the

3 This discussion is based on an article written by Marvin B. Lieberman, a Professor of Policy at UCLA's Anderson School of Management, dated August 17, 2000, entitled "The Magnesium Industry in Transition." The article was obtained from Dr. Anderson's web site at http://www.anderson.ucla.edu/faculty/marvin.lieberman/publications/MagnesiumlndustryTransit ion2001.PDF. A copy of the article is included as Exhibit 1.

-4-288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

plant to design capacity, and sold it to Magnesium Corporation of America ("Magcorp") in 1989.

In the early 1990's, imports began to flood into the market, first from Canada, then from Russia

and China. Although antidumping duty orders and countervailing duty orders were imposed on

imports from Canada in 1992 and on imports from China in 1995, the severe price pressures in

the market caused Dow to close the Freeport plant in 1998 (after rising water from a hurricane

damaged the plant) and Alcoa to close Northwest Alloys in 2001. In 2001, Magcorp filed for

bankruptcy protection, and its assets were purchased out of bankruptcy in 2002 by US

Magnesium. Since that time, US Magnesium has been the only U.S. producer of commercial

quantities of primary magnesium.

B. Overview of US Magnesium

US Magnesium harvests brines from the Great Salt Lake to produce magnesium. US

Magnesium directly employs 440 people, and indirectly employs hundreds more, such as

contractors and service providers in Tooele County, Utah. United Steelworkers Union Local

8319 represents workers at US Magnesium's plant, and the union supports US Magnesium's

efforts in this Section 232 investigation.

US Magnesium produces pure magnesium (containing at least 99.8 percent by weight of

magnesium), alloy magnesium (containing less than 99 .8 percent by weight of magnesium), and

magnesium granules, as well as recovering and selling a variety of byproduct chemicals. 4

C. U.S. Magnesium Production is Critical to National Security

As noted above, US Magnesium is the last remaining producer of primary magnesium in

the United States. Twenty years ago, there were three U.S. producers.5 Today, only US

288154

4 http://usmagnesium.com/products/; http ://usmagnesium.com/products/ chemicals/.

5 https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/magnesium/400498.pdf.

- 5 -

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

Magnesium remains, and while it has invested significantly to increase its production capacity by

two-thirds in the past ten years, domestic capacity remains less than half of what it was 20 years

ago.

The Defense Logistics Agency ("DLA") lists magnesium as a strategic material,6 and US

Magnesium frequently has military visitors to its plant to review its operations. For example, in

October 2016 and April 2017, groups from the [

] visited US Magnesium. During these visits, they discussed the importance of

magnesium to the national economy and to national security. 7 As another example, in May

2016, representatives of [ ] visited the plant. In a letter thanking

US Magnesium for its hospitality, [ ] noted that the magnesium provided by

US Magnesium for countermeasure flares is a "critical material. "8 Magnesium is used in the

production of a number of products that are critical to national security.

1. Aluminum

With respect to aluminum, the direct subject of this investigation, magnesium is essential

to the production of aluminum alloys. Aluminum is identified by the DLA as a strategic

material.9 Virtually all aluminum alloys contain magnesium, which provides hardening

properties to the alloys. Because almost all aluminum alloys contain magnesium, and because

the domestic manufacture of products made from aluminum alloys is critical to U.S. national

security, the domestic production of magnesium is also essential to U.S. national security.

288154

6 http://www.dla.mil/HQ/ Acquisition/StrategicMaterials/Materials.aspx

7 See Exhibit 2.

8 See Exhibit 3.

9 Id.

- 6 -

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

The U.S. aluminum industry consumes approximately [ ] ST of magnesium per

year. US Magnesium supplies approximately [ ] percent of that consumption. Over recent

years, the prices at which it sells to the aluminum sector [

] percent from 2012 to 2016 due to low-priced import competition.

2. Steel

Magnesium is also essential to the production of steel. Desulfurization reagents

containing magnesium are used to remove sulfur. Sulfur is an undesired element in most steel

applications (a result of the use of coke in blast furnace smelting), because it impedes welding

and forming and can cause the steel to be brittle. To remove sulfur from steel during the

steelmaking process, a desulfurizing reagent - primarily made of magnesium, lime, and/or

calcium carbide, either alone or in a blend - is injected into the hot metal through a lance. Once

the reagent is injected, the sulfur-containing compounds found in the iron transfer to slag, which

is then discarded. US Magnesium [ ], as it

was first [ ] by imports of granular magnesium from China, and then, following the

imposition of anti dumping duties on such imports from China, by imports of magnesium

reagents. US Magnesium (then operating as Magnesium Corporation of America, or Magcorp)

supplied almost [ ] ST of magnesium to the U.S. market [ ] for

the desulfurization market in 1998. That volume fell to just over [ ] ST in 1999, as

desulfurization reagent producers shifted purchases to granular magnesium from China. By

2000, [ ] . In 2001, Magcorp obtained trade relief against

imports of granular magnesium from China. Magcorp, and subsequently US Magnesium,

[

], because those products were not covered by the order. Today,

- 7 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

US Magnesium estimates that approximately [ ] ST of magnesium is contained in the

desulfurization reagents consumed by the domestic steel industry each year. 10

3. Military Flares

Magnesium is used in other military applications. Among specific DOD uses, it is used

in the production of illumination and countermeasure flares for the U.S. military. The volume of

magnesium consumed in these applications varies from year to year, and totaled [ ] in

2016. US Magnesium has supplied [ ] of the volume for these applications in

recent years.

4. Heater Packets for Military Food Rations

Magnesium is used in heater packets for military food rations. US Magnesium has

[

]

5. Gravity Castings

Alloy magnesium is used in the production of gravity castings for the aerospace industry,

such as gearboxes, transmission housings, andjet engine components. US Magnesium estimates

that [ ]

of magnesium used for DOD castings in 2016. US Magnesium competes with import sources for

this business, and in 2016, supplied [ ] of the market.

6. Magnesium Sheet and Plate

The DOD also consumes magnesium sheet and plate in various applications, including

test fixtures, batteries, and electronics enclosures. US Magnesium estimates that this use

10 Imports of magnesium desulfurization reagents enter under HTS 3824.99.9295. This is a basket category, so the exact volume of imports is not known. US Magnesium has requested a breakout in the tariff schedule for this product.

- 8 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

accounts for [ ] per year. In recent years, this business was supplied by imports from

[

]

7. Titanium

Magnesium is also used in the production of certain metals, including titanium,

beryllium, and zirconium, all of which have significant military applications. Magnesium is used

in the production of titanium, with one pound of magnesium required for each pound of titanium

produced. Titanium is identified by the DLA as a strategic material, 11 and is used in the

production of components for fixed and rotating wing aircraft, and vehicles such as tanks. US

Magnesium has supplied [ ] of the magnesium purchased to produce titanium

sponge in the United States. That volume, however, has fallen sharply with the closure in 2016

of ATI's plant in Rowley, UT, right next to US Magnesium's production facility. When ATI

closed the facility, its press release indicated that the closing was due to adverse market

conditions. 12

8. Beryllium

Beryllium is identified by the DLA as a strategic material, 13 and is used in military-

related applications such as electrical components, optical systems, and tank mirrors. Each

pound of beryllium produced requires almost 3 pounds of magnesium. US Magnesium estimates

that U.S. beryllium production consumed [

288154

11 http://www.dla.mil/HQ/ Acquisition/StrategicMaterials/Materials.aspx

12 http://ir.atimetals.com/news-and-events/press-releases/2016/08-24-2016-122218784

13 Id.

- 9 -

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

] of that volume supplied by US Magnesium. While US Magnesium has [

] with import sources.

9. Zirconium

Zirconium is identified by the DLA as a strategic material, 14 and is used in nuclear

reactors andjet engine components. Over one-half pound of magnesium is used to produce each

pound of zirconium. The volume of magnesium used in this application has declined over recent

years, totaling approximately [ ] in 2016. US Magnesium [

]

D. Imports Pose a Significant Threat to Continued U.S. Magnesium Production

1. Magnesium is an Import Sensitive Material

US Magnesium, and its predecessor, Magcorp, have been combating dumped and

subsidized imports of pure, alloy, and granular magnesium for many years. In such

investigations, the U.S. International Trade Commission ("ITC") has made a series of findings

with respect to the "conditions of competition" that affect the domestic market for magnesium.

In its investigations, the ITC has found that "{t}he market for pure and alloy magnesium {is}

price competitive," with differences other than price reported to be insignificant. 15 In more

recent investigations, the ITC has continued to find magnesium to be "a fungible, commodity

product, for which price is an important factor in purchasing decisions." 16 The ITC has further

found that demand for magnesium is derived from the demand for applications in which

14 Id.

15 Pure and Alloy Magnesium from Canada and Pure Magnesium from China, US ITC Pub. 3859 (July 2006) ("Pub. 3859") at 27-28.

16 Magnesium from China and Russia, Inv. Nos. 731-TA-1071 and 1072 (Final), USITC Pub. 3763 (Apr. 2005) ("Final Reporf') at 16.

- 10 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

magnesium is used. 17 These applications include aluminum production, die-casting, and iron and

steel desulfurization. Demand in these applications "generally tracks overall economic

activity." 18

The ITC has noted frequently in its discussion of the conditions of competition that

primary electrolytic producers of magnesium, such as US Magnesium:

Have a strong incentive to maintain a continuous level of production because the electrolytic cells used to make primary magnesium must be kept in constant operation to avoid their deterioration and significant rebuilding costs. Therefore, when faced with price competition, primary magnesium ?roducers will tend to cut prices to maintain production volume. 1

Demand for magnesium is price inelastic, meaning that lower prices for magnesium do not cause

increased consumption. Thus, primary magnesium producers are extremely sensitive to price

competition.

2. Imports of Magnesium Have Historically Threatened and Continue to Threaten Magnesium Production in the United States (and in Other Countries)

Imports of magnesium pose a significant threat to the domestic industry. Twenty years

ago, the domestic industry consisted of three producers, US Magnesium (then Magcorp},

Northwest Alloys (a captive producer for Alcoa Aluminum), and Dow Magnesium. Dow

Magnesium closed its Freeport, Texas plant in 1998. It suffered damage to the plant in a

hurricane, and market conditions, caused largely by low-priced imports, were so poor that Dow

decided not to return the plant to operation. Northwest Alloys closed in 2001, with the owners

citing the high production costs relative to other sources. In fact, Alcoa closed the plant because

288154

11 Id.

18 Id.

19 Id. at 17, footnote omitted.

- 11 -

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

it was able to purchase imports of magnesium at significantly lower prices. As U.S. production

capacity was being closed, the Chinese industry expanded capacity on a massive scale. U.S.

capacity exceeded Chinese capacity through 1998, until China's capacity started to increase

significantly, causing U.S. production to shut down.20

Similarly, there were three primary magnesium producers in Canada, all of which have

ceased production. One Canadian producer, Magnola Metallurgy, started production in 2001 at a

plant that was designed eventually to reach 58,000 MT of capacity, but it was temporarily idled

in 2003, before the construction of its production equipment was complete. Magnola's press

release regarding its closure stated" ... {W}e are facing reality head-on and adjusting to the

developments that have occurred in the marketplace, including increased production from

China."21 Another Canadian producer, Norsk Hydro Canada Inc. (''NHCI") announced in

October 2006, that it would close its facility. 22 The company stated:

It is primarily the extensive export of very low-priced metal from China that is preventing continued production at the world's largest and most environmentally friendly magnesium plant."23

A third Canadian producer, Timminco, scaled back its production starting in 2006.24

Press reports note that Timminco "found that it could import magnesium from China {into

20 See Exhibit 4.

21 News Release, ''Noranda to Shutter Quebec Magnesium Plant," American Metal Market March 25, 2003 (emphasis added), attached in Exhibit 5.

22 See "Norsk Hydro to close Quebec magnesium plant," American Metal Market (October 31, 2006) in Exhibit 6.

23 Id.

24 See Timminco magnesium workers sign labor deal, American Metal Market (June 5, 2007) in Exhibit 7.

- 12 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

Canada} at a lower cost than running the Haley operation."25 The most recent (2015) USGS

Minerals Yearbook reports no Canadian production of primary magnesium. 26

In fact, the global magnesium market continues to be highly distorted by the Chinese

industry. The Chinese magnesium ind~stry is by far the largest in the world. While global

production (used as a proxy for consumption) was reported to be 972,000 MT in 2015, global

capacity was reported to be 1.9 million MT, with China accounting for 1.6 million MT of that

capacity.27 Regular trade remedies against China, such as antidumping duty orders, are not

sufficient to protect domestic industries. For example, the EU instituted an antidumping duty

order against imports of pure magnesium from China in April 1999. Despite this measure,

French producer Pechiney closed its 17,000 MT primary magnesium production facility in

Marignac, France in June 2001 due to competition with cheaper imports,28 although it continued

to perform some recycling. In 2002, Norsk Hydro Norway closed its 42,000 MT plant in

Porsgrunn, Norway, blaming low-priced exports from China.29 Indian producer Southern

Magnesium and Chemical, which had obtained an anti dumping duty order on imports of pure

magnesium from China, eventually ceased production and instead became an importer of low-

25 Id.

26 See Exhibit 8.

21 Id.

28 "Pechiney's Magnesium Plant to Stay Shut," American Metal Market (October 16, 2001 ), in Exhibit 9. Although Pechiney ceased production of primary magnesium in 2001, it maintained all of the equipment necessary to re-melt magnesium and alloy magnesium scrap in order to produce secondary magnesium.

29 "Porsgrunn Magnesium to End," American Metal Market (October 14, 2001), in Exhibit 10.

- 13 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

priced magnesium from China.30 Through the Chinese industry's expansions and the closure of

capacity in other countries, including the United States, China's share of total global magnesium

production capacity has increased from 5.2 percent in 1998 and 1999 to over 84 percent in 2014

and 2015.31

IV. CONSIDERATION OF THE REGULATORY FACTORS STRONGLY SUPPORTS A DETERMINATION THAT IMPORTS THREATEN TO IMPAIR THE NATIONAL SECURITY OF THE UNITED STATES

A. The Quantity and Makeup of Imports of Magnesium Are Harming the Domestic Industry, Strongly Supporting an Affirmative Determination

The damaging effects of imports are particularly clear with respect to the magnesium

industry. As detailed above, numerous producers, both in the United States and in other

countries, have been forced to cease production because of the severe imbalances caused by the

massive overcapacity in China. The distortions in the market make US Magnesium highly

vulnerable to import competition. If US Magnesium is forced to shut down due to the poor

market conditions caused by imports, national security interests will be harmed. Third-country

suppliers unable to compete against the onslaught of Chinese production would also likely close

over time, as they have over the past decades, leaving the United States and other markets reliant

on magnesium from a single country source: China.

While overall import volumes of traditional forms of magnesium have not increased

significantly, the non-traditional forms have made significant gains in acceptance among

magnesium consumers. 32 Inexpensive substitutes for primary pure and alloy magnesium, namely

30 Annual Report 2002-2003, Directorate General of Anti-Dumping and Allied Duties.

31 See Exhibit 4.

32 See Exhibit 11. Combined imports of magnesium under the HTS numbers for pure magnesium, alloy magnesium, magnesium waste and scrap, and granular magnesium have not increased overall in volume from 2014 through Ql 2017.

- 14-288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

magnesium waste and scrap and secondary alloy magnesium, are being imported in increased

quantities and used in various applications, driving down primary magnesium prices. The price

differential is quite notable, as shown below.

TABLE 1: U.S. Import Average Unit Values (" AUV") for Primary Pure and Alloy Magnesium and Secondary Alloy Magnesium and Magnesium Waste and Scrap (in $/lb.)

2013 2014 2015 2016 Imports of:

Primary Pure Magnesium $1.86 $1.86 $1.84 $1.62

Secondary Alloy Magnesium $1.66 $1.57 $1.50 $1.41

While the existing U.S. antidumping duty orders against imports of pure, alloy, and

granular magnesium from China have largely been successful in controlling direct imports of

those products, the resulting higher U.S. prices have made the United States a primary market for

third-country suppliers, such as Israel, Russia, and Turkey. Additionally, imports of inexpensive

substitutes for pure and alloy magnesium, based on scrap from very low priced Chinese ingot

generated in third-country markets, have increased in volume at declining prices, allowing

Chinese magnesium to continue to disrupt U.S. market conditions. Imports of magnesium waste

and scrap have increased 25 percent during the 2013 - 2016 period. 33 This scrap results from

overseas diecasting operations that use low-priced Chinese alloy magnesium as the input.

Diecasting produces significant amounts of scrap - the use of 100 pounds of magnesium in

diecasting operations results in about 40 to 60 pounds of scrap. Magnesium scrap is used as a

substitute for primary pure magnesium as an alloying ingredient by the aluminum industry, and

33 Id.

- 15 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

is used by the diecasting industry in place of primary alloy magnesium. While magnesium scrap

is used in many of the same applications as primary magnesium, the AUV of such imports was

less than half of the AUV of imports of primary alloy and two-thirds of the AUV of imports of

primary pure magnesium in 2016.

Scrap from extremely low-priced Chinese alloy magnesium used in overseas diecasting

operations also finds its way to the United States as secondary alloy magnesium. The main

import sources of this secondary alloy magnesium are Taiwan, Germany, Canada, and Japan.

Other sources include France, Mexico, South Korea, the Czech Republic, India, Austria,

Hungary, Serbia, and Thailand.34 Secondary alloy products are used as substitutes for primary

pure and alloy magnesium in a wide range of applications. Imports of secondary alloy

magnesium from these sources have increased by 78 percent from 2013 to 2016. As shown in

Table 1, the AUV of such imports fell by 15.0 percent and is far below the AUV of imports of

primary pure or alloy magnesium.

B. US Magnesium's Capacity is [

Following the imposition of antidumping duty orders covering magnesium in various

forms from China, US Magnesium invested significantly in its production facility, both to

increase capacity as well as to capture increased volumes of byproducts, the sales of which offset

US Magnesium's production costs. In the last ten years, US Magnesium has increased

nameplate capacity by two-thirds, and has started spending on projects that would increase its

capacity even more. However, US Magnesium has put its investments on hold, and even its

existing capacity is currently [ ], because of current

market conditions. US Magnesium:

34 See Exhibit 4. Imports from the UK are excluded from this analysis. These are very high-priced specialty alloys used to make gravity castings.

- 16 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

• Currently has access to sufficient raw materials to produce a larger volume of

primary magnesium;

• Has unused cell capacity, as it has shut down the cells that supplied ATI, has

postponed rebuilding of other electrolytic cells, and has plans to cut an additional

[ ] MT of capacity in 2017 and 2018 by taking down additional electrolytic

cells;

• Has invested [ ] to expand capacity, but put such plans put on hold due

to deteriorating market conditions. Significant investments include [

].

C. Imports of Magnesium Have Caused Serious Adverse Effects

Over the years, US Magnesium has sought, and received, relief from imports of

magnesium from China. However, this relief has not been sufficient to ensure US Magnesium's

continued operations. US Magnesium first received relief against imports of pure magnesium

ingots from China in May 1995. 35 Following the imposition of that antidumping duty order,

imports of pure magnesium in ingot form fell sharply. However, following that action, imports

of granular magnesium increased rapidly, and a petition was filed against such imports, with

relief being granted in November 2001. Following this order, imports of granular magnesium

fell, and imports of alloy magnesium increased. US Magnesium sought, and received, relief

35 See Exhibit 12. The imports subject to this order include pure magnesium as well as "off-spec pure" magnesium, which contains less than 99.8 percent magnesium but does not meet an ASTM specification for alloy magnesium. Thus, the investigation and orders covered the imports entering under the HTS number for pure magnesium as well as most, if not all, of the imports entering under the HTS number for alloy magnesium.

- 17 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

against imports of alloy magnesium from China as well, with an antidumping duty order issued

in April 2005. While US Magnesium enjoyed significant benefits from these actions, these

benefits have not been sustained.

Despite the fact that unwrought forms of magnesium from China are generally covered

by antidumping duty orders with high deposit rates, US Magnesium is still harmed by imports.

First, imports of downstream products have increased. For example, US Magnesium previously

sold significant volumes of pure magnesium ingots for the production of granular magnesium

that was then converted into desulfurization reagents. After U.S. imports of granular magnesium

from China were subject to duties, imports of magnesium desulfurization reagents, largely from

China, increased, taking over that segment of the market. This is true for magnesium anodes as

well.

Furthermore, because the Chinese magnesium industry is so dominant globally,

producers in third countries have shifted significant volumes to the U.S. market, as imports from

China cause severe price depression in third-country producers' home markets and export

markets, in order to take advantage of the higher U.S. prices. Of course, while U.S. prices

remain higher than in markets where Chinese magnesium trades freely, the increase in imports

from other sources has suppressed U.S. prices dramatically as more and more sources compete to

sell magnesium in the United States, and the gap between U.S. and other market prices has

narrowed significantly. 36 Moreover, as noted above, there has also been a significant increase in

volumes of secondary alloy magnesium and magnesium scrap. As Chinese alloy magnesium is

used in third-country markets, the scrap metal generated is often either shipped to the United

States or converted into secondary alloy in other countries and shipped to the United States.

36 See Exhibit 13 Slide 25.

- 18 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

This is evident from the U.S. import statistics. While import volumes have not increased

uniformly, the sourcing of imports has shifted, and import values have fallen, taking U.S. prices

with them. For example, with respect to pure magnesium, Israel was the largest import supplier

in the 2012 to 2017 period.37 In 2012, Israel accounted for over 80 percent of total imports of

pure magnesium. By the first quarter of 2017, Israel accounted for only 46 percent of imports,

with imports from Russia gaining significant share at very low prices. It is easy to see how

imports from Russia gained share: the AUV of such imports was only $1.31 per pound in the

first quarter of2017. Total imports of pure magnesium have increased in 2017, with imports

from low-priced sources such as Russia and Turkey accounting for the increase.38 This price is

significantly below US Magnesium's prices, allowing imports from Russia to displace US

Magnesium at numerous customers. From 2012 to Ql 2017, the average unit landed duty-paid

value of imports fell from $1.98 per pound to $1.52 per pound, a decline of over 23 percent.

A similar pattern exists with respect to imports of alloy magnesium. Israel has

consistently been the largest import supplier of alloy magnesium, accounting for over 50 percent

of total imports in 2012 and 2013.39 By 2016, Israel accounted for only 31.5 percent of total

imports, with imports of secondary alloy magnesium, made from scrap produced from Chinese

alloy magnesium, increasing sharply. From 2012 to 2016, the average unit landed duty-paid

value of imports under this HTS category fell from $2.61 per pound to $2.34 per pound, a

decline of over 10 percent. However, as shown in Table 1 above, the AUV of such secondary

288154

37 See Exhibit 11.

38 Id.

39 Id.

- 19 -

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

alloy magnesium imports fell by 15. 7 percent and is far below the A UV of imports of primary

pure or alloy magnesium.

The decline in U.S. prices has been significant. Industry publication Platts Metals Week

reports weekly spot transaction prices for imported pure magnesium in the U.S. market. This

price declined from a high of $2.60 per pound in February of2010 to only $1.455 per pound in

April 2017, a decline of $1.145 per pound, or 44 percent.40

As non-Chinese producers have competed in the U.S. market, and particularly as low

priced imports of scrap and secondary alloy have increased in volume, both largely based on the

use of Chinese magnesium in other markets, prices have fallen significantly. 41 In addition to the

absolute decline in price, the spread between magnesium prices in the U.S. and other markets has

narrowed substantially.

While US Magnesium enjoyed several years of substantially improved performance due

to the antidumping duty orders, the dynamics described above have placed considerable pressure

on U.S. magnesium prices, and thus US Magnesium's viability. As described above, US

Magnesium's electrolytic production process does not permit US Magnesium to tum its cells on

and off in the near-term based on market conditions. Instead, US Magnesium is forced to

maintain its production levels, and meet the lower prices offered in the U.S. market in order to

keep its plant operating. Export markets are not a viable outlet for US Magnesium's production,

for the same reason that third-country producers are eager to sell into the U.S. market: prices in

other markets are very low in comparison to the U.S. market because of China's unrestricted

access.

40 See Exhibit 14.

41 See Exhibit 13, Slide 25.

-20-288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

While U.S. prices remain above Chinese levels, they are currently [

] The AUVofUS Magnesium's sales have fallen from

[

]

In response to deteriorating U.S. market conditions, [

]

This decline in prices and increase in costs necessarily had an adverse effect on US

Magnesium's profitability. In FY 2012, US Magnesium's operating income was almost [

] percent of sales.42 By FY 2016, operating income had fallen to [

percent of sales. During the November 2016 -March 2017 period, US Magnesium [

].

42 US Magnesium's fiscal year runs from November 1 through October 31.

- 21 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

For FY 2017, US Magnesium's most recent projections show continued deterioration.

US Magnesium projects its sales volume to decline by [

] These changes are expected to result in [

]

D. Without Relief, the Domestic Magnesium Industry Will Suffer Further Injury

Without relief, the recent downward trends experienced by US Magnesium are likely to

worsen. There has been no interruption in the factors causing these trends, and none is expected.

Despite the enormous level of unused capacity in China, capacity continues to be added.

The largest addition to capacity is the 100,000 MT Qinghai Salt Lake Magnesium plant.43

According to Qinghai Salt Lake Magnesium, construction of the plant is complete, and

magnesium production began in January 2017 .44 Plans for this plant include expanding capacity

to 400,000 MT.45 While this is the largest expansion in Chinese capacity, the 2015 Minerals

Yearbook identifies two additional increases to capacity in the Chinese industry.46

Increases in third-country magnesium capacity are also planned and underway. A slide

presentation at the International Magnesium Association's 2017 conference shows plans to add

capacity in Canada, India, Turkey, Iran, and Australia. Given the level of global oversupply in

the magnesium market, a significant portion of this increase in capacity is likely to be aimed at

288154

43 See Exhibit 15.

44 Id.

45 See Exhibit 8 at 45.3.

46 Id.

-22-

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

the U.S. market.47 Although the financial viability of these plans is uncertain, domestic

magnesium production will remain under threat from numerous sources in addition to China.

These proposed increases in capacity are not linked to increases in demand. The most

recent estimates from the U.S. Geological Survey show the global magnesium industry operating

at just above 50 percent of capacity.48 Global production in 2015, the most recent year for which

U.S. Geological Survey data are available, declined 3 percent from 2014 levels.49 Decreased

production in China was attributed to declines in consumption in China and in its export

markets. 50 Additions to capacity are clearly not being driven by demand factors.

In the United States, one significant U.S. consumer of magnesium, ATI, closed its

titanium plant in Rowley, Utah, causing U.S. demand for magnesium to decline by [

]. US Magnesium supplied this plant, and its closure makes US Magnesium

even more vulnerable to the effects of imports.

Due to the conditions in the U.S. market, US Magnesium is reducing its production.

Once capacity is shut down, it cannot easily be restarted. The electrolytic cells that supplied ATI

have been shut down, removing [ ] MT of capacity. US Magnesium plans to cut [

] . These combined shutdowns amount to the removal of over [ ]

MT of domestic capacity to produce magnesium. These capacity reductions are harmful to US

Magnesium for multiple reasons. As already noted, an electrolytic cell that has been shut down

288154

47 See Exhibit 13, Slide 30.

48 See Exhibit 8.

49 Id.

50 Id.

-23 -

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

cannot simply be restarted. It must undergo an extensive, and expensive, rebuilding process,

which can take many months. While a cell can be rebuilt in three weeks, US Magnesium has

only a limited number of workers trained to do this very specialized work. Therefore, only one

cell can be rebuilt at a time. Furthermore, significant lead time is required for the materials

necessary to rebuilt the cell. The anode, for example, takes approximately six months to procure.

The cost to rebuild one of US Magnesium's larger electrolytic cells, including labor and

materials, is approximately [ ].

The capacity reductions are further harmful to US Magnesium because of the high fixed

costs associated with its plant. US Magnesium's plans to increase capacity over the years have,

in large part, been made with a goal of spreading those high fixed costs over a larger volume of

production. The closure of capacity has the effect of raising per-unit production costs, making it

more difficult for US Magnesium to compete in the long term. In addition, the planned

reductions in production volume make it likely that US Magnesium would have to terminate

skilled workers. The specialized workforce needed to build and operate these unique electrolytic

cells will be lost. Such workers have at least 10 to 20 years of experience, and are not easily

replaced in a short period of time if conditions warranted the return of capacity to production.

In addition to the reductions in production, US Magnesium has a number of plant

improvements that it has started to implement, but put on hold because of the deteriorating

conditions in the market. In 2014, US Magnesium announced its plans to increase nameplate

capacity to 76,500 MT. Instead, it has taken capacity offline. In order to reach 76,500 MT, US

Magnesium would have had to build additional electrolytic cells and complete the recently

constructed spray dryer to increase the availability of magnesium chloride feedstock. While US

Magnesium began implementing this program, it stopped when it realized that it would not have

-24-288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

additional demand for capacit)r, and would instead be lowering its production levels. While the

electrolytic cells can be rebuilt and the [ ], current

and expected conditions in the U.S. magnesium market do not warrant the necessary capital

expenditures. At the public hearing held in conjunction with this investigation, several U.S.

aluminum producers noted that, while military applications account for only a portion of U.S.

aluminum production, the industry must rely on healthy conditions in the commercial segment of

their business to ensure the availability of aluminum for military applications. US Magnesium

faces the same conditions with respect to the magnesium market.

E. Any Relief on Imports of Aluminum Should Include Imports of Important Inputs Such as Magnesium

Magnesium production is essential to U.S. national security due to its necessity in the in

the production of many products, including aluminum, which is essential to national security.

Any import relief granted in this investigation should include relief for the domestic magnesium

industry as well. While the domestic magnesium industry has sought and won relief against

unfairly traded imports, the protection is not sufficient to overcome the distortions of the global

magnesium market caused by the enormous Chinese industry and its massive overcapacity.

These conditions make the U.S. market, and its relatively high prices, a highly desirable market

to any third-country producers who prefer not to compete with China's extremely low prices.

US Magnesium urges the imposition of relief in the form of tariffs on imports of pure

magnesium (HTS 8104.11.0000), alloy magnesium (HTS 8104.19.0000), magnesium waste and

scrap (HTS 8104.20.0000), granular magnesium (HTS 8104.30.0000), magnesium reagents

(HTS 3824.99.9295), and magnesium anodes (HTS 8543.30.9000).51 Allowing the current

51 US Magnesium believes that the conditions of competition in the magnesium industry would make quotas and tariff-rate quotas far less effective in providing relief.

-25 -288154

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

conditions to continue without relief would likely result in the eventual closure of the sole

remaining U.S. producer of primary magnesium. The United States would lose an industry that

is essential to national security, eroding its manufacturing base, as well as a highly skilled, well

paid workforce that has been in place for decades. Without a domestic industry, the existing

antidumping duty orders would be irrelevant and eliminated, and third-country producers that are

viable largely due to the higher U.S. prices would start to fail as well. China would be the only

remaining source of magnesium to the U.S. market.

V. CONCLUSION

The Department of Commerce should find that imports of magnesium in various forms

threatens to impair the national security of the United States and include relief from such imports

in any remedies ordered in the Aluminum 232 investigation.

Please contact us if you have any questions.

Jennifer Lutz

ECONOMIC CONSULTING SERVICES, LLC 2001 L Street, NW, Ste. 1000 Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 466-7720

Economic Consultant for US Magnesium LLC

- 26 -288154

Respectfully submitted,

Isl Stephen A. Jones Stephen A. Jones Benjamin J. Bay

KING & SPALDING LLP 1700 Pennsylvania A venue, NW Washington, D.C. 20006-4706 (202) 737-0500

Counsel for US Magnesium LLC

NON-CONFIDENTIAL

Exhibit List

1. The Magnesium Industry in Transition, Marvin B. Lieberman, August 17, 2000

(http://www.anderson.ucla.edu/faculty/marvin.lieberman/publications/MagnesiumindustryTr

ansition2001.PDF)

2. [ ]

3. [ ] 4. U.S. Geological Survey Data on U.S. and Chinese Magnesium Capacity

5. Noranda to Shutter Quebec Magnesium Plant, American Metal Market, March 25, 2003

6. Norsk Hydro to close Quebec Magnesium Plant, American Metal Market, October 31, 2006

7. Timminco Workers Sign Labor Deal, American Metal Market, June 5, 2007

8. U.S. Geological Survey, 2015 Minerals Yearbook: Magnesium

9. Pechiney's Magnesium Plant to Stay Shut, American Metal Market, October 16, 2001

10. Porsgrunn Magnesium to End, American Metal Market, October 14, 2001

11. U.S. Imports of Magnesium

12. U.S. Imports of Pure, Alloy, and Granular Magnesium from China

13. Global Primary Magnesium Supply and Demand Balance, 2016

14. Metals Week U.S. Dealer Import Price for Pure Magnesium 15. Qinghai Salt Lake 2017 Slide Show

288153

The Magnesium Industry in Transition

By Marvin B. Lieberman 1

The Anderson School at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

Abstract. Dow Chemical dominated the magnesium industry for decades but ultimately exited in 1998. This article considers the evolution of the industry and Dow's decision to divest.

Key Words: Capacity,· dominant film, exit, limit pricing, magnesium.

I. Introduction

Few economists are familiar with the industrial history of magnesium, the lightest metal in

commercial use. For much of the twentieth century, the Dow Chemical Company dominated world

production of magnesium and maintained a position of near-monopoly in the United States. To deter

entry when commercial demand for magnesium began to grow appreciably in the 1960s, Dow

employed a remarkable range of tactics, including announcements of excess capacity, limit p1icing, and

sophisticated price discrimination.2 Moreover, Dow's production efficiency, honed through decades of

experience, was widely recognized. Yet by the end of the century Dow's advantages had eroded, and

significant entry occurred in the US and especially abroad. Faced with growing import competition,

falling prices, and a storm~damaged plant, Dow exited the industty in November 1998.

This a1ticle describes the evolution of the magnesium industry and its current status.3 It begins

with an overview of magnesium's uses and production methods, and concludes with an assessment of

Dow's exit decision.

1. Magnesium's ApP-Iications and Markets

Initially used as a pyrotechnic material in bombs and flares, magnesium now has diverse

applications. These include "structural" uses in aerospace, automotive, and other products that take

1 I thank Ken Corts and Deborah Kramer for helpful comments. This aiticle gives interpretations of Dow Chemical's actions, and I retain full responsibility for errors. 2 These tactics are considered in detail in Lieberman (1983, 1998). 3 Extensive information on the magnesium industry can be obtained from the US Geological Survey web site, http://minernls.usgs.gov/mincrals/pubs/commodity/magnesium/. Kenney ( 1979) provides historical perspective.

Marvin B. Lieberman 8117/00

advantage of magnesium's light weight.4 Additional applications exploit magnesium's extensive

chemical prop~rties. About half of all magnesium produced today is added to aluminum alloys to

enhance their characteristics. Magnesium's single largest use is in aluminum "flip-top" cans, where

about ;2.5% magnesium content is essential.

Unlike other metals that trade on a global market at a reasonably uniform price, the markets for

magnesium have been fragmented. For many years magnesium producers such as Dow were able to

maintain price discrimination, facilitated by sizable US imp01t tariffs. 5 Tariff reductions have curtailed

the scope for such practices, leading to a more uniform market. The US duty on imported magnesium

ingot foll from 40% in the 1960s to 8% by the mid-1980s, with most imports from Canada and Israel

now fully exempt.

2. Production Teclmolog)(

There are two principal methods for making magnesium: the thermic process and the

electrolytic process. Small-scale producers have generally utilized the thermic process in which

dolomite, an abundant ore, is heated until magnesium vapor is given off. Entry is relatively easy for this

technology, which has low capital cost but high operating costs. Prior to the rationalization of world

magnesium tariffs, most major developed countries had at least one thermic plant.

Electrolytic plants are capable of attaining lower average total cost than thennic plants. Dow

was a pioneer in the development of electrolytic technology. In the electrolytic process, an electric

current is applied through magnesium chloride obtained from underground brine or sea water. While

the electrolytic process for magnesium is similar to the standard Hall process for making aluminum,

cost-efficient operation of a magnesium plant has required a considerable amount of tacit engineering

knowledge. In recent years, however, know-how has become more widespread as foreign producers

have gained experience and process improvements developed in the former Soviet Union have become

available for license. With technology less of a barrier, access to cheap energy has become more

important, thus favoring plant locations outside the United States.

4 Magnesium's density is 112 pounds per cubic foot, compared with 175 pounds for aluminum and 449 pounds for steel.

5 To utilize excess capacity in the 1960s, for example, Dow sold magnesium to buyers in Germany at a discount of up to 40% off the US market price. Moreover, magnesium alloys with elastic demand were often priced at a discount by Dow.

Marvin B. Liebcmrnn 8/17/00

2

II. Industry Evolution

1. Early Growth Driven by Wartime Demand

Wartime surges in demand shaped the magnesium industry dming the first half of the twentieth

century. Prior to 1915 Gennany was the world's sole source of magnesium. With the British blockade

of Gennany during World War I, seven magnesium plants were built in the United States, although only

those of Dow Chemical and the American Magnesium Company (AMC) were commercially significant.

The end of World War I led to a drastic decline in the demand for magnesium. All of the

magnesium plants in the US were shut down except for those operated by Dow and by AMC, which

became a subsidiary of Alcoa. In 1927 Dow and AMC signed a patent cross-licensing agreement, and

they set up an arrangement that granted AMC the right to purchase magnesium from Dow at a

significant discount from the market price. Dow then expanded capacity, and AMC closed its plant

Dow thus became the only US magnesium producer from 1928 until the outbreak of World War Tl.

By 1938, the eve of World War II, the four major magnesium-producing countries were

Germany with 12,000 tons per year capacity, Britain with 5,000 tons per year capacity, the US (Dow)

with 3,300 tons per year capacity, and France with 2,500 tons per year capacity. During World War II,

magnesium production capacity expanded enormously throughout the world. German capacity reached

a peak of 34,000 tons through the expansion of existing facilities. Furthermore, as the war progressed,

the Ge1mans built new magnesium plants in Austria and Norway.

Wartime expansion of magnesium production in the US statted in 1940 when Dow doubled the

capacity of its Midland, Michigan, plant and started construction of a new plant in Freeport, Texas.

During 1941-1943, fifteen new magnesium plants were built in the United States, thirteen by the US

government. Dow operated only one of these government-owned plants (at Velasco, Texas, not far

from the Freeport plant). By the end of the war the US production capacity for magnesium increased by

a factor of nearly one hundred, to 291,000 tons per year. 6

6 The outbreak of war in Europe did not prevent the application of antitrust law in the United States. In 1941 the Justice Department charged Dow, Alcoa, and I. G. Farben of Germany with price-fixing and the use of patent cross-licensing to monopolize magnesium production in the US. The companies pleaded no contest and signed a consent decree that called for compulsory patent licensing and the dissolution of prior patent agreements.

Marvin B. Liebennan 8/17/00

3

2. Postwar Deve1012ments

After the war, production of magnesium decreased drastically. US production foll from a peak

of 184,000 tons in 1943 to only 5,300 tons in 1946. Germany was prohibited from producing

magnesium. Moreover, most of the German plants were located in what became the Soviet zones of

Germany and Austria. The Russians dismantled the plants and took them back to the USSR.

As the war ended, Dow closed its original plant at Midland because of improved economies at

its Freeport, Texas plant. All of the government plants were closed by November 1945. Thus, Dow's

Freepmi plant remained the only plant in the US producing magnesium after the war. Post-war US

magnesium production rose very modestly from 5,300 tons in 1946 to 15, 700 tons in 1950, which was

significantly below the 18,000 ton capacity of the Freeport plant.

The Korean War revived magnesium production. Dow increased the capacity of its Freeport

plant to 24,000 tons per year. Seven government-owned magnesium plants were reactivated and by the

end of 1951 were producing at 70% of capacity. Overseas, Norsk Hydro Elektrisk (a private company

with majority ownership by the Norwegian government) began reconstruction of the German-built plant

at Heroya, No1way, at 12,000 tons per year capacity in 1950.

After the Korean War demand for magnesium decreased, and virtually all the US government

owned magnesium plants were again shut down except the Velasco, Texas, plant operated under lease

by Dow. The US govenunent established a public auction to sell the Velasco facility, which was by far

the most efficient of the magnesium plants built by the government dwing World War II. Prior to the

auction, Dow operated the Freeport and Velasco plants at capacity to build a magnesium stockpile.

Dow proved to be the sole bidder for the Velasco plant, which was subsequently closed for four years

as Dow drew inventories down.

While Dow dominated the post-war production of magnesium in the US and worldwide, an

important constraint on Dow's pricing was the existence of a US government-owned stockpile amassed

for emergency wartime use. At its peak, this government stockpile contained enough magnesium to

supply all US consumption for several years or more. The government made periodic sales from the

stockpile, which was gradually depleted and eventually tenninated in 1975.

Marvin B. Liebennan 8117/00

4

3. Entr,y Deterrence by Dow

In 1958 a new entrant, Alabama Metallurgical Corporation (Alamet), began construction of a

new 6,000-ton-per-year thennic plant, partly to serve the market for high-purity magnesium, which

Dow was unable to supply. By the mid-1960s, several firms announced their intention to enter into

magnesium production, attracted by magnesium's growth potential and by prospective refinements in

process technology. In addition, the major aluminum producers were known to be considering entry

into magnesium.

Presumably, Dow recognized that significant entry would have made magnesium more of a

commodity, which would have reduced Dow's margins and ability to price discriminate. Dow

unde1took a series of sophisticated actions and announcements to deter these potential entrants:

" Dow committed to a six-year "price incentive program" of gradual price cuts to buyers in

the aluminum alloying industry. The details of this program were designed to deter entry by

the technologically-advanced aluminum makers, such as Alcoa. Dow could have cut price

immediately but chose instead to commit to a schedule of time-phased reductions. By doing

so, Dow minimized its revenue loss while still sending a credible signal on its likely

production costs.

" For other buyers Dow continued its policy of pricing magnesium ingot slightly below the

production cost of a thennic plant. This limit pricing policy was reinforced by periodic

announcements of excess capacity and efficiency gains, which signaled the potential for

price cuts if large-scale entry occurred. For example, in 1965 Dow announced a series of

incremental capacity expansions obtained by improving the electrolytic cells at its plants.

One year later Dow reported that it was reactivating large amounts of idle capacity at the

Freeport plant. And in 1967 Dow announced construction of a new magnesium plant

located in the Pacific Northwest. Dow built part of this plant but then put construction on

hold.

Thus, Dow announced excess capacity, signaled low costs, and contractually guaranteed low

prices to a targeted set of buyers. These deterrence tactics, which have been considered at some length

Marvin B. Lieberman 8117/00

5

in the economics litcrature,7 appear to have forestalled large-scale ent1y into the US magnesium

industry in the 1960s. Two start-ups entered the industry but soon encountered serious technical

problems with their plants. Moreover, by the end of the decade, Alamet closed its small therrnic plant

after years of marginal results. 8 Thus, by the early 1970s Dow found itself once again the sole producer

of magnesium in the United States.

4. Dow's Strategic Shift

The early 1970s were a turning point for Dow. The firm shifted from its "limit-pricing"

strategy, designed to maintain Dow's position as the dominant magnesium producer, to a "skim

pricing" type of strategy intended to maximize more immediate returns. (Figure l plots the price of

magnesium ingot from the 1950s through the 1990s.) Dow ended its "price incentive program" in

1971, raising the price paid by the aluminum companies from 30.25 cents to 36.25 cents per pound. By

the following year, growth in US demand had absorbed all of Dow's excess production capacity.

Dow's ability to raise prices was constrained briefly by wage and price controls imposed by the US

government. When these controls were lifted in 1974, Dow responded by doubling the price of

magnesium ingot, followed by additional price hikes. In part, such price increases were needed to

cover the post-OPEC rise in energy costs. But the pattern suggests that Dow was now striving to

maximize short-te1m profitability while cutting back on investment in the magnesium business. For

example, in 1972 Dow sold its magnesium research library to Battelle Laboratories and transferred

magnesium R&D staff to other business units. Dow's production capacity peaked in the 1970s and

then declined as the firm chose not to expand or even renew its existing facilities.

Responding to these developments, Alcoa entered the magnesium industry, opening a plant in

Washington state in 1976. NL Industries, one of the announced entrants of the 1960s, struggled with

its technologically-troubled plant at the Great Salt Lake. AMAX, Inc., acquired this plant in 1980,

brought it to design capacity, and then sold it to Magnesium Corporation of America (MCA). Yet

despite the entry of these two large-scale magnesium producers in the United States, Dow's skim

7 See, for example, Spence (1977), Dixit (1980), Bulow et al. (1985) and Lieberman (1987) on excess capacity; Gaskins (1971), Milgrom and Roberts (1982) and Harrington (1986) on limit pricing; and Aghion and Bolton (1987) on contractual barriers to entry. While Dow's behavior may seem consistent with theories on the use of excess capacity as an entry deteITcnt, it is important to note that Dow exploited capacity built by the government during World War II. Dow understood how to use excess capacity as a strategic weapon but never built such capacity when required to pay the full investment cost. 8 Following Alamet's exit, the US market for high-purity magnesium was supplied by imports.

Marvin B. Lieberman 8/17/00

6

pricing strategy seems to have been comparatively successful. The inflation-adjusted US market price

of magnesium held at historically high levels for more than a decade. Moreover, Dow's share of US

capacity remained above 60%, even though the firm's world market share steadily declined.

5. The Rise of Imgorts

Dow's position weakened considerably in the 1990s. Tariff reductions, expansions by foreign

producers, and the fall of communism made the magnesium market more global and increased the

pressure on magnesium prices in the United States. Norsk Hydro, the world's second largest

magnesium producer and a major refiner of aluminum, opened a large-scale magnesium plant in Canada

in early 1990.9 Much of the plant's output was exported to the United States, where magnesium prices

fell sharply. MCA filed an anti-dumping suit, which blocked fu1iher imports from Canada until the mid-

1990s. Concurrently, the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 led to an intensification of

competition in the world magnesium market. Magnesium producers in the fonner Soviet states of

Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan turned to exports as means of generating hard currency. Average US

prices dropped significantly in 1992, and a two-tier pricing system was established, with import prices

below the transaction prices charged by US producers. In 1994, MCA initiated further anti-dumping

actions against shipments from Russia, the Ukraine and China. With the cessation of US imports from

these countries, as well as from Canada, prices rose substantially in 1995.

With the resolution of the dumping investigations by the U.S. International Trade Commission,

imports resumed in 1996 from Russia and Canada. This led to an immediate drop in prices, followed

by continued price reductions over the next few years. The US became a net importer of magnesium,

and by 1997 imports had grown to exceed Dow's annual production capacity. The trend was forecast

to continue for the foreseeable future, as new entrants announced plans for additional large-scale

magnesium plants in Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, and elsewhere.

6. Dow's Exit

Beleaguered by imports and the erosion of its cost advantage, Dow's magnesium operations

were further hit by natural catastrophe in 1998. Dow's remaining magnesium plant at Freeport, Texas,

was struck by lightning in June and flooded by Hurricane Francis and other rainstorms in August and

9 Industry experts believed that this plant achieved cost efficiencies exceeding those of Dow.

Marvin B. Lieberman 8/17/00

7

September. Dow declared a "force majcure" and then announced on November 20 that it was shutting

the plant, cffoctive immediately. This abrupt closure ended Dow's hist01y of more than 80 years in the

magnesium industry, serving as the world's largest producer from World War II through the mid-

1990s.

Dow's exit signaled the declining role of US producers in the increasingly global magnesium

industry. The principal countries importing magnesium to the United States from 1995 to 1998 were

Canada (52%), Russia (22%), China (12%) and Israel (5%). In 1999, the year after Dow's exit, the

world's major magnesium producing nations were the United States (22% of world output), Canada

(23%), China (16%), Russia (13%), Norway (9%) and Israel (6%). Norsk Hydro had emerged as the

world's largest magnesium maker, with plants in Norway and Canada accounting for slightly less than

one-fourth of world magnesium output. A quarter century earlier, Dow's world market share had been

twice as great, and Dow was the sole producer in the United States, from which it exported heavily.

Assuming that many of the announced magnesium plants are completed by new entrants around the

world, this trend toward globalization and declining concentration should continue through the early

part of the twenty-first century.

Ill. Conclusions

The hist01y of the magnesium industry illustrates the rise and fall of a dominant finn, a process

that has been documented for many industries (e.g., Rosenbaum, 1998). Factors leading to Dow's

success have been common among dominant firms: early entry, cost efficiency, and strategic deterrence

behavior. What seems unusual about magnesium, though, is that Dow appears to have made a

conscious choice to relinquish its position. This strategic shift occurred in the early 1970s, when Dow

began to "harvest" its magnesium business rather than invest beyond its Texas plants. Dow switched

from a "limit pricing" strategy designed to deter entry, to a "skim pricing" type of strategy that

ultimately sacrificed the firm's viability as a magnesium producer.

Why did Dow make such a choice? Unlike Dow, other dominant firms have opted to expand

preemptively in related industries (e.g., DuPont in titanium dioxide (Ghemawat, 1984) and Alcoa in

aluminum prior to 1945). One potential explanation is that Dow's cost advantage was not sustainable.

Dow's production process benefited from years of incremental improvements but was not

Marvin B. Liebennan 8/17/00

8

fundamentally different from the technology potentially available to others. (DuPont, by comparison,

had pioneered a more differentiated process for titanium dioxide.) Moreover, Dow's cost advantage

was due in part to simple economies of scale. Dow was the only magnesium producer with electrolytic

plants of efficient scale in the decades following the Second World War. Given modest demand for

magnesium during peacetime and a potential global market fractured by tariffs, there were no

opportunities for enhy of another efficient-scale plant until the US market expanded sufficiently in the

1960s. Later, as demand grew and tariffs fell, such plants could be sited in many locations around the

world.

Constraints relating to "economies of scope" may also have made continued expansion

unattractive for Dow. Dow's cost advantage arose partly from economies specific to the Texas plant

complex where Dow's magnesium process utilized byproducts ftom other chemical operations. Such

advantages could not be easily replicated at other sites, and the supply of byproducts may have limited

Dow's ability to expand internally. Moreover, while Dow may have enjoyed economies of scope in

magnesium production, on the marketing side magnesium had little in common with Dow's core

chemical businesses. Magnesium was thus a potential candidate for divestiture as Dow sought to focus

and restructure its operations in the 1980s and 1990s. 10 At the same time, price hikes on magnesium

provided cash flow in a period of transition that was difficult for Dow and for the chemical industry

generally.

Continued expansion in magnesium would also have risked antitrust scrutiny. Alcoa's policy of

aggressive capacity expansion was condemned by Judge Learned Hand in his Supreme Court rnling

against that company in 1945. Similar investments by Dow to maintain dominance would surely have

attracted Justice Department attention in the 1970s.

Thus, many factors contributed to Dow's decision to divest. Taken as a whole, Dow's actions

and the industry's evolution show how dominant positions can erode in capital-intensive, homogeneous

product industries where technological change takes place relatively slowly. Over a period of decades,

the forces of demand growth, tariff reduction, and technology diffusion have transformed magnesium

from a specialty material with a dominant producer into a commodity product with a competitive global

market. While such trends toward globalization and declining concentration can be seen in many

industries, seldom do we observe such a dramatic decline by a dominant firm.

10 In the early 1990s Dow unsuccessfully sought a buyer for the Freeport plant.

Marvin B, Liebe1man 8/17/00

9

REFERENCES

Aghion, P. and P. Bolton (1987). "Contracts as a Barrier to Enh-y," The American Economic Review 77(3): 388-401.

Bulow, J., J. Geanakoplos and P. Klemperer (1985). "Holding Idle Capacity to Deter Entry," The Economic Journal 95: 178-182.

Dixit, A. (1980). "The Role ofinvestment in Entry-Dete1Tence." The Economic Journal 90: 95-106.

Gaskins, D. (1971). "Dynamic Limit Pricing: Optimal Pricing Under Threat of Entry." Journal of Economic Theory.

Ghemawat P. (1984). Capacity Expansion in the Titanium Dioxide Industry. The Journal of Industrial Economics XX.XIII: 145-163

Harrington, J. E. (1986). "Limit Pricing when the Potential Entrant is Uncertain of Its Cost Function," Econometrica 54(2): 429-438.

Kenney, G. B. (1979). An Analysis of the Energy Ejficiency and Economic Viability of Expanded Magnesium Utilization, Garland Publishing, New York.

Lieberman, M. B. (1983). "The U.S. Magnesium Industry (A), (B), and (C)," Stanford University, Graduate School of Business, case S-BP-231.

Lieberman, M. B. (1987a). "Excess Capacity as a Barrier to Entry: An Empirical Appraisal." Journal of Industrial Economics 35(June): 607-627.

Lieberman, M. B. (1998). "Dow Chemical and the Magnesium Industry." In D. L Rosenbaum, ed., Market Dominance, Praeger, Westport, CT.

Milgrom, P., and D. J. Roberts (1982). "Predation, Reputation, and Entry Detenence." Journal of Economic Theory 27(2): 280-312.

Rosenbaum, D. I., ed. (1998). Market Dominance: How Firms Gain, Hold, or Lose It and the Impact on Economic Pe1j'ormance, Praeger, Westport, CT.

Spence, A. M. (1977). "Entry, Capacity, Investment and Oligopolistic Pricing." The Bell Journal of Economics 8: 534-44.

Marvin B. Liebetman 8/17/00

10

Figure 1: Price of Magnesium Ingot

2.5---------------------------, -1992 Dollars

--Current Dollars

2

"'C c: ::l 1.5 0

D.. !... (]J

Q. II) ... ~ 1 - -···· 0 Cl

0 " " ... " " " ... 1954 1958 1962 1966 1970 1974 1978

Year

1982 1986 1990 1994 1998 Source: US Geological Survey, Metal Prices in the United States through 1998. (Yearend price of 99.8% purity ingot, updated) .

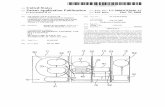

1,800,000

1,600,000

1,400,000 i='" 2 5

1,200,000

1,000,000

800,000

600,000

400,000

0

Primary Magnesium Production Capacity in China and the United States (in metric tons)

·------·...-,. 90.0%

*' ~<· S0.0%

!L .. ____ .. ···--··-~ 70.0% "

f/ --;;;

60.0%

Chinese capacity as ~

; 50.-0%

% of global capacity i •

~-,,,,

1--------------------.c "------~ ;... 40.0%

1----------------"---------·---------J ' 30.-0%

1------------b: ' 20.0%

10.0%

~ 0.0%

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

- Chinese Capacity - U.S. Capacity "'""' .. Chinese capacity as% of Global Capacity

WDRLD ANNUAL PRIMARY MAGNESIUM (Metric tons)

Total 500,000 497,500 523,000 523,000 486,000 426,000 497,000 601,000 621,000 722,-000

China as% of Total 5.2% 5.2% 6.2% 6.2% 24.7% 28.2% 37.8% 44.9% 48.6% 55.7% 61.9%

Source: USGS Minerals Yearbook, various years.

65.-0"/o

WORLD A.."INUAL PRIMARY MAGNESfUM (Metric tons)

188,000

Total 886,000 1,080,000 l, l 70,000 . l 12.:l:Q'"O!l9_b~:20,QQQ~!·.~l!Q2QQQ).,11Q,Q.Q~!.,!l.~~QQ~~~.Q~J,.~Q{l±Q()_(L

China as% of Total 67.9% 80.8% 8L5% 83.1% 8L8% 81.2% 80.4% 84.6% 84.7% 842%

611612017 Noranda to shutter Quebec magnesium plant I American Metal Market

COPYING AND DISTRIBUTING ARE PROHIBITED WI THO UT PERMISSION 0 .F THE PUBLISHER

No1·anda to shutter Quebec magnesium plant Mar 2r,, 200~ ! 09:1 o PA'f I

Noranda Inc. has finalized its decision to close the Magnola magnesium plant in Danville, Quebec. The Toronto-based company confirmed that the shutdown, slated to begin next month, is "for an indefinite period of time, until market conditions allow for a viable operation of the plant."

Noranda, which holds an So-percent stake in the operation, announced its intention to close Magnola in January (AMM, Jan. 29), but held talks with 20-percent owner Socit Gnrale Financement de Qubec (SGF) before finalizing the decision.

SGF, a government agency, initially said it would look at ways to keep the plant open and lobbied the Canadian Minister for International Trade to consider imposing dumping duties on Chinese magnesium imports (AMM, Feb. 5).

Two weeks ago the decision to close the plant was delayed while further negotiations between Noranda and SGF took place. It now appears that those talks failed to bear fruit and Noranda will begin to lay off Magnola's 380 workers by the end of next month. About io workers will remain on site after the shutdown to maintain the plant, Noranda said.

A spokeswoman for SGF did not return calls seeking comment Tuesday.

Bob Sippel, president ofN oranda subsidiary Mtallurgie Magnola Inc., decried the impact that Chinese imports have had on Magno la.

"Although we believe in a positive future for magnesium, we are facing reality head on and adjusting to the developments that have occtmed in the marketplace, including increased production from China," Sippel said.