Transnational Strategies and Regional Development: The Case of GM and Delphi in Mexico

Transcript of Transnational Strategies and Regional Development: The Case of GM and Delphi in Mexico

Industry and Innovation, Volume 11, Numbers 1/2, 127–153, March/June 2004

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND

REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT: THE CASE

OF GM AND DELPHI IN MEXICO

JORGE CARRILLO

The transnational corporation General Motors (GM) has transferred a large numberof its industrial plants and jobs to Mexico, particularly to the northern region of

the country. Delphi Automotive Systems,1 a GM spin-off specializing in parts andcomponents, has become Mexico’s second largest private employer after the CarsoGroup. Delphi’s growth as an employer has coincided with an upgrading of the firm’sactivities in Mexico from simple assembly to include sophisticated product design,development, and research. This shift has enriched workplace activities in several ofDelphi’s plants and, more importantly, facilitated the establishment of the firstintra-firm network of technical centers and manufacturing plants within Mexico’smaquiladora export industry.2 Among the locations where GM and Delphi haveestablished plants, Ciudad Juarez stands out as the best example both of this industrialupgrading based on the agglomeration of simple processes like the assembly of wireharnesses, and of the development potential of the automotive industry and thechallenges that must be overcome to achieve such a breakthrough.

Delphi’s role in Ciudad Juarez follows closely the trajectory of the auto industrywithin Mexico, which has always been dominated by foreign capital. Since the 1980s,however, the Mexican automotive industry has undergone a deep transformationbased on investments by the US ‘‘Big Three’’, particularly GM, and the rapid produc-tivity growth and regional specialization of their operations. In order to confrontJapanese competition, these companies relocated plants to Mexico to take advantageof the country’s low wages and geographical proximity to the USA, as well asincentives offered through the Mexican government’s macroeconomic policies andthe existence of aggressive local private economic groups. Thus, the strategy ofconsolidating and expanding the Mexican consumer market was exchanged forone that sought positive outcomes based on increasing efficiency of transnationalcompanies’ direct investments (Carrillo et al. 1999).

1 Delphi separated from GM in 1995 and became fully independent in 1999. By 2001 it employed more than 193,000persons around the world, and operated 198 manufacturing plants, 53 sales and service centers, 31 technicalcenters, and 44 joint ventures, located in 43 countries.

2 Maquiladoras are foreign-owned or Mexican controlled plants that process, manufacture, and assemble temporarilyimported components for re-export in free trade zones or in-bond operations enjoying special tariff and taxtreatment. The maquiladoras are not an ‘‘industry’’ in the proper sense of the word because they include plantoperations in many sectors, although electronics, auto parts, and apparel are the most important. The maquiladoraprogram was initiated in 1965 under the Border Industrialization Program. The majority of plants are ownedby American, Japanese, and Korean firms that moved to the northern border of Mexico in order to reduceproduction costs.

1366-2716 print/1469-8390 online/04/01/20127-27 © 2004 Taylor & Francis Ltd

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

DOI: 10.1080/1366271042000200484

128 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

Through this change in corporate strategy, the Big Three sought to transformMexico into a low-cost export platform for small four and six cylinder cars (Mortimore1995), and global sourcing of auto components. New engine plants were verysuccessful in introducing modern technology (Shaiken and Herzenberg 1987); thesame was true of the maquiladoras (Krafcik 1988; Shaiken 1990). More recently,Mexican plants have been producing light trucks. The rise in Mexican production offinished cars and trucks has been overwhelmingly for export, primarily to the USAand Canada (95 percent in 2002). There are now close to 100 models of automobilesand light trucks assembled in Mexico, and these are no longer limited to economyvehicles (AMIA 2002: No. 445).

In terms of productive specialization, priority has been placed on the productionand export of compact and subcompact cars, certain types of engines, and a limitedrange of auto parts, particularly wire harnesses, radios, seat coverings, mufflers, andexhaust pipes (Carrillo and Ramırez 1997). The maquiladoras that manufacture autoparts have played a tremendous role in this process. Many are the only plants thatproduce certain types of auto parts for the US market. In addition, they are the maingenerators of employment in Mexico. In 2001, automotive parts and componentsrepresented the principal export ‘‘product’’ under the Maquiladora and PITEX pro-grams, with $11.8 billion in exports to the USA.3

This paper is divided into three parts. The first section examines GM’s global strat-egies and Mexico’s changing place within them. These strategies are essential tounderstanding GM’s presence in Mexico and the profound transformation of its affili-ates in re-orientating away from production for the Mexican domestic market towardsglobal operations. The second section traces the evolution of the maquiladora industry,demonstrating how evolving strategies for reducing costs through the establishmentof export-oriented plants in Mexico, combined with intervening government supportand organizational learning, have resulted in an important process of skill upgrading.Finally, the successful experience of Delphi-GM in Ciudad Juarez is analyzed as anexample of how the agglomeration of companies under specific social and institutionalconditions can add value by forming a sectoral cluster in which a network of companiesaccelerate learning, especially among engineers and technicians.

In this manner the firm, the sector, and the territory combine to support specificconditions which, though difficult to imitate, provide hope for upgrading industrialdevelopment in the widely diffused export production zones. Four key trends emergefrom this analysis:

(i) changes in global sourcing strategies, with greater supplier selectionand the development of closer, knowledge-intensive linkages with coresuppliers (the GM story in Section 1);

(ii) changes in local clusters’ characteristics as they undergo upgradingprocesses based on the success of some local producers in building akey position within global supply chains (the maquiladoras story inSection 2);

3 Between 1998 and 2001 the percentage change in the value of exports in this sector was 33.2 percent.PITEXóProgram of Temporary Imports for Export.

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 129

(iii) the influence of policy initiatives both at the global and regional levels(NAFTA) and at the local level (Chihuahua cluster upgrading program)on the evolution of corporate strategies (Delphi story in Section 4);

(iv) the improvement of employment conditions in Mexican plantsengaged in higher-value activities despite the increasingly global natureof labor market competition (Section 3).

1. GENERAL MOTORS’ TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES

GM’s strategies will be reviewed first from a global perspective, and then as theyapply to Mexico. Globally, GM is one of the world’s leading companies, and numberone in the automotive industry. However, like other US corporations, GM facedenormous organizational, financial, productive, and competitive problems during the1980s, due in part to strong market penetration by Japanese firms. This situationforced GM to experiment with different strategies in order to maintain its position,which resulted in a broad industrial restructuring and rapid reduction in production,plants, and company employment within the USA.

Between 1985 and 1988, GM’s output decreased from 9.06 to 7.74 million units.Nevertheless, GM maintained its role as the leading company in the automotiveindustry. In 1990, GM’s critical situation led its new president to improve thecorporation’s finances through a broad restructuring program focused primarily oncost reductions. The main features of this restructuring included: (a) alliances withother auto companies, aimed at extending GM’s product line and markets, andimproving technology; (b) industrial modernization through the adoption of newtechnologies, automation of production processes, and introduction of new produc-tion methods based on functional flexibility, work teams, and quality circles; (c)reductions in the number of models offered and specialization of production amongfinal assembly plants, and auto parts divisions; and (d) a reduction in the number ofsuppliers worldwide. This global reorganization became necessary for GM in the mid-1990s (Bordenave and Lung 2002).

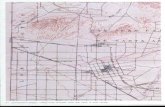

These changes followed a series of previous strategies designed to reduce costs,particularly labor costs. In the 1960s and 1970s GM closed factories and laid offworkers in the northern and midwestern regions of the USA, while opening plants inthe southern ‘‘right-to-work’’ states. Beginning in the late 1970s, GM has locatedplants in regions where labor is cheap and abundant (Figures 1 and 2), thus favoringsome Latin American countries, and especially Mexico, where in 1986 GM employed52,000 workers in final assembly and maquiladora plants, and produced more than600,000 engines and 200,000 vehicles.

Development of suppliers

Along with reducing its own wage bill, one of GM’s key cost saving strategies involvedreducing the number of its suppliers, while developing the ‘‘survivors’’. The mainobjective of this policy is to modify the type of relationships between GM and itssuppliers worldwide, in order to optimize this interaction and reduce costs. Thestrategy was designed to address three overlapping problems. First, component

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

130 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

FIG

UR

E1:

LOC

AT

ION

OF

VEH

ICLE

IND

UST

RY

Sou

rce:

Ban

com

ext

(200

3)

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 131FI

GU

RE

2:P

RES

ENC

EIN

MEX

ICO

Sou

rce:

Del

ph

i(2

002)

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

132 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

purchasing was one of the company’s main runaway expenditures in the USA. Second,GM subsidiaries produced 70 percent of all the components used in their vehicles inthe USA. Finally, the company’s losses in North America were massive. By paring itssupply chain, GM aimed to save between $1.5 billion and $2.0 billion between 1992and 1995 (Gonzalez 1996).

Through this strategy, GM seeks to reduce the worldwide manufacturing costs ofthe company’s parts suppliers as much as possible. On the one hand, this requiresUS suppliers to compete with their foreign counterparts, both for the American aswell as the international market, based on quality, price, and service. However, thesystem simultaneously creates a tremendous demand for international coordinationof auto parts. Therefore, GM assists suppliers in identifying the areas where mostwaste is occurring, as well as those with high and unjustified costs. The central idea,as expressed by ex-president of GM-Mexico Richard Nerod, is that the suppliers’survival depends on their ability to operate in the framework of globalization. Thatis, they should participate more emphatically in the export market, particularly in theNAFTA region, to become more competitive, provide for a more balanced commercialexchange, reduce the number of suppliers with whom they contract, and ensure thattheir production of vehicles and auto parts becomes increasingly economical.4

Overall, this strategy calls for externalizing auto parts, and maintaining final assemblyand the production of engines within the company. For GM, this meant graduallyisolating its parts divisions before finally spinning off Delphi in 1998. Prior to its sale,GM encouraged Delphi to operate as an autonomous company, and required it tocompete for contracts based on price, quality, and delivery time, rather than the‘‘family company’’ relationship. In the mid-1990s, GM incorporated its many autoparts companies into a single firm: Delphi Automotive Systems (now renamed asDelphi), the largest global player in this highly fragmented industry.5

Delphi has simplified its organizational structure by unifying its six divisions andbecoming an integrated supplier. Delphi is the world’s most diversified supplier ofsystems and automotive components, capable of manufacturing everything fromcomponents to subsystems, complete systems, and modules, with an emphasis ontotal quality, cost control, and market responsiveness (Delphi Automotive Systems1996).ç1

Particularly important are the Packard and the Energy and Engine Control System(Delphi Energy) divisions. The former has manufacturing and engineering facilities inmore than 32 countries and is uniquely equipped to assist its clients with thedesign, development, and production of totally integrated power systems and signaldistributions. The latter represents the most comprehensive portfolio of power traincapabilities in the global automotive industry. With a worldwide network of technical

4 The main criticism directed against this system comes from the UAW, which views it as a permanent threat, on theone hand, to close dozens of factories that are financially independent, yet commercially dependent on GM’sindustrial organization, and, on the other hand, to relocate plants toward areas with lower costs, such as southernEurope or northern Mexico. The important 1998 UAW-GM conflict revolved around this issue.

5 The firm comprises six divisions focusing on three main activities: Dynamics and Propulsion (Delphi Energy &Engine Management Systems, Delphi Saginaw Steering Systems, and Delphi Chassis Systems); Security, Temperature& Electric Architecture (Delphi Interior & Lighting Systems, Delphi Harrison Thermal Systems, and Delphi PackardElectric Systems); Electronic Communications and Portable (Delphi Delco Electronics Systems). In 1997 it accountedfor 20 percent of GM’s $31.4 billion sales.

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 133

and production centers, the Energy and Engine Control System division can design,develop, and manufacture totally integrated systems and components to controlstorage and energy conversion, the flow of air and fuel toward the engine, thecombustion process, and the conversion of vehicle emissions (Delphi AutomotiveSystems 1996). The Mexican Technical Center (MTC) and the Electrical Systems andSwitching plant (SEC) in Ciudad Juarez, which will be discussed in Section 3, belongto this division.

Furthermore, this logic of maintaining fewer but more closely integrated suppliershas been replicated down the supply chain. Like GM, Delphi has reduced the numberof its suppliers globally, but at the same time has integrated them and made themmore efficient. The pressure of globalization is acutely felt, with GM demanding thatall original equipment suppliers (OES) be certified as compliant with QS 9000 qualitynorms by 1998.

GM in Mexico

General Motors-Mexico (GMM) was formally incorporated in 1985, but it began assem-bling CKD sets for vehicles for the domestic market in 1936 with 48 workers (CruzGuzman 1995). The role played by GM’s Mexican operations has changed over time.Between the 1930s and the early 1960s, the automaker operated a single plant inMexico City assembling imported auto parts for sale to the domestic market. From themid-1960s until the late 1970s, operations expanded to include the manufacture of autoparts and engines for the domestic market, and to a lesser extent for export, with thecompany adding a plant in Toluca. Since the early 1980s, GMM has operated primarilyas a manufacturer of vehicles, engines, and auto parts for export. During this period,automobile and engine plants were established in Ramos Arizpe, Coahuila, and variousmaquiladoras were built in Mexican border cities. Most recently, GMM invested $400million in a new light truck-assembly plant that opened in Silao in 1994 (Figure 1).In addition, GMM’s role was expanded to include undertaking co-investments andparticipating in business ventures beyond the automotive industry (Figure 1).

Historically, GM’s strategy in Mexico has been to increase its productive capacity,diversify its product line and markets, and expand its business operations. In short, ithas sought to substantially boost its importance in the country. For 2002, GMMoccupied the second place in domestic auto sales (22 percent of all cars manufacturedand imported) and second place in light vehicles (27 percent of the total). It is theonly producer of heavy trucks in Mexico (AMIA 2002: No. 445). In addition, Delphiwas the leading transnational corporation in Mexico in terms of number of plants andsecond in total employment. This is consistent with GM’s tendency toward globalrationalization, specializing each of its operations to focus on a single market, in thiscase, NAFTA. In terms of auto production, the strategy for Mexico has been to buildfewer models in larger quantities to serve the North American market. A similar trendcan be seen in the maquiladora plants producing wire harnesses and electricalproducts.6

6 The ignition wiring harnesses sets consist of multiple isolated electric drivers that are assembled to terminals,connectors, sockets, and other wiring devices. They are used to connect several electric components (e.g. lights,instruments, and motors) to an energy source (generally batteries and generators), etc. to handle high voltages inselect parts of ignition (as starters, generators, distributors, and spark plugs) in vehicles like cars, planes, and boats(USTIC 1997).

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

134 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

According to GM’s Chief Economist, Mustafa Mohatarem, NAFTA is much morerelevant for Mexico than for other countries. Already, GM has accelerated pre-existingtendencies, and more important still, changed the role that Mexico plays in thegroup’s current and future growth strategy. Mohatarem underlined the following keytrends: a rise in domestic sales and of the projections for the short and long term; arise in technological capabilities; a rise in the value-added generated in the country;a rise in labor-intensive work (practically all of which has been moved to Mexico);and the strengthening of this process due to the recent strikes in the USA (author’sinterview, 26 March 1999). Nevertheless, important changes are affecting Mexicanproduction because of the 2001–2003 recession in the USA and the emergence ofChina as a major producer.

Overall, GMM has shifted its strategies over time as the country’s economic policieshave changed. During the import substitution (ISI) period, GMM formed allianceswith Mexican firms to take advantage of protectionism and government regulations.Later, during the free trade period, they developed joint projects with Mexican plantsto supply GM-OEMs and auto parts plants. But the most important strategies were todevelop new plants for export to the US market and to establish maquiladora facilitiesfor the same purpose from the early 1980s.

Production of vehicles and engines for export

Traditionally, GMM has been one of the main producers of vehicles for both thedomestic and export markets, and especially for light trucks, as is indicated in Table 1.From 1999 to 2002 GM light vehicle production grew from 325,000 to 500,000.Originally, during the ISI period, GM’s corporate strategy in Mexico centered on truckproduction for the local market. In the early 1960s, engine production began inToluca (capacity 120,000) while truck assembly took place in Mexico City (capacity60,000). During the boom years of the import substitution policy (1978–82), GMMadapted to the county’s growing demand for passenger cars by concentrating onassembling and selling models aimed solely at the national market. Even so, salesvolumes were very low, never reaching even 20,000 units a year for any specific

TABLE 1: MEXICO: GENERAL MOTORS VEHICLE PRODUCTION 1980–2001

Production for domestic Share of total vehicles in

market Production for export Mexico

Years Autos Trucks Autos Trucks Autos (%) Trucks (%)

1980 21,250 23,474 0 0 7.01 13.15

1985 18,667 37,038 29,833 119 19.63 24.56

1990 32,782 62,311 40,993 — 21.34 31.71

1995 14,985 19,569 124,703 395,566 19.97 24.54

2000 104,278 14,970 83,226 242,196 14.65 42.65

2001 82,662 16,374 56,294 292,472 11.49 51.14

2002 97,133 20,461 45,048 345,360 12.47 57.65

Source: Author’s elaboration based on AMIA, Organo Informativo de la Asociacion Mexicana de la IndustriaAutomotriz, A.C. (different years).

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 135

model, including the best-selling Malibu. By 2002, GM-Toluca produced close to12,000 light vehicles.

But GMM’s raison d’etre since the late 1970s has been to produce at new facilitiesfor export to the US market. This process began with a $250 million investment in anew complex at Ramos Arizpe to manufacture engines and passenger cars, and newarrangements for auto parts (in-bond plants and ‘‘projects’’ with national companies)(Carrillo et al. 1999). The Ramos Arizpe complex had the capacity to build 450,000engines and 100,000 passenger cars annually, accounting for 37 percent of all enginesexported from Mexico between 1982 and 1994 (15 million, making it the largestexporter of engines in Latin America) and a significant proportion of passenger carexports since 1987. While in 1980 practically all its production was earmarked forthe domestic market, by 2001, 77.9 percent of its manufactured units were for export.More recently, capacity at the Ramos Arizpe plant has been increased to 300,000 carsa year. In 2002, the plant produced more than 250,000 light vehicles, but productionhas recently been scaled back to less than 200,000 units (Global Insight 2003). Underç2this same strategy, the old facility located in Toluca (a brownfield site) was alsorestructured to produce engines for both the export and domestic markets (Table 1).

The changes in GM’s strategy were very important for the Mexican automobileindustry. As at Ford, the group’s strategy was not so much to modernize the existingMexico City/Toluca facilities and convert them into export operations. Rather theprincipal focus was to establish new export facilities, first for the manufacture ofengines, but then for passenger cars as well. Besides the plant in Ramos Arizpe, anew truck plant is operating in Silao which produced 230,000 units for export in2002, matching their production of the previous 3 years (Figures 1 and 3). However,GM’s strategy was less clear-cut than Ford’s, and was based more solidly on low wagesthan on high-tech facilities. Still, international competitive standards were reached.The new strategy entailed specialization in certain engines, two passenger vehicles(the Century and Cavalier models), and certain auto parts via in-bond plants, all forexport. Thus, in somewhat different fashion, GM also integrated its new facilities inMexico into its North American production system and, in the case of auto parts andespecially engines, into its global sourcing arrangements.

Location of auto parts maquiladoras (Delphi-GM)

Beginning in 1978, GM developed a broad-based maquiladora program consisting by1988 of 15 companies with 27 plants employing approximately 20,000 workers, andproducing a wide range of automotive parts for export to the USA, such as instrumentpanels, air and heating controls, antennas, front lights, molds, ceramic magnets, etc.(Expansion 16 August 1989). By 1992, GMM had, directly and indirectly, 32 maquila-dora plants in northern Mexico (El Financiero 4 December 1992). Today, Delphiemploys more than 71,000 employees in Mexico at close to 60 plants (Figure 4).Delphi-Mexico represents slightly more than a third of the corporation’s worldwideworkforce (204,000 jobs), and everything indicates that the process of job relocationwill continue. A Delphi worker in Mexico receives, on average, from $1.65 to $3 perhour plus benefits, compared with $10 per hour for the average non-union Delphiworker in Vandalia, Ohio, and $17 per hour in the case of a UAW member (Wall Street

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

136 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

FIGURE 3. GM PLANTS PRODUCTION

Source: Author’s elaboration based on CIMEX-WEFA Authomotive Industry Analysis (2003)

Journal 3 June 1996). Hence globalization of production at Delphi has also beenaccompanied by an important process of rationalization of production, which consistsof reducing the number of plants in the USA, concentrating factories in Mexico, andintegrating vertically and horizontally.

GM’s productive integration in the North American market has been extremelysuccessful. In two decades it has created an important platform for vehicle, engine,and auto parts exports, structurally integrating the Mexican plants into their NorthAmerican production. The spin-off of Delphi from GM has also had a tremendousimpact on Mexican auto parts operations, creating a true North American regionalproduction network.

2. THE EVOLUTION OF THE MAQUILADORA INDUSTRY IN MEXICO

The recent history of the maquiladora industry in Mexico has been strongly led bythe automobile sector, in particular the growth of Delphi Automotive Systems.Through the establishment of assembly plants for export, the maquiladora industryhas grown at meteoric rates, generating thousands of jobs and millions of dollars inforeign exchange (Table 2). On the other hand, however, the industry has been

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 137

FIGURE 4: DELPHI: MODEL OF LEARNING AND COORDINATION: POLI-CENTRAL

Source: Lara, A. and Carrillo, J. 2003: Technological globalization and intra-company coordination in theautomotive sector: the case of Delphi-Mexico, International Journal of Automotive Technology and

Management, 3(1/2): 101–121.

TABLE 2: MEXICO: GROWTH OF THE MAQUILADORA INDUSTRY

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2002 2007a

Employment (000)

Total 119.5 212.0 460.3 634.0 1,291.2 1,082.5 1,650.1

Auto parts 7.5 40.1 98.9 139.1 237.0 231.1 399.6

Plants

Total 620 760 1,938 2,104 3,590 3,265 3,986

Auto parts 53 63 160 166 246 258 319

Mexican value-added ($ million)

Total 762.2 1,160.9 3,610.9 4,959.9 17,270.0 18,800.0 33,370.0

Auto parts 61.9 330.3 910.1 1,190.4 3,181.9 4,545.9 8,754.4

aProjections: CIMEX-WEFA and Global Insight 2003: Maquiladora Industry Outlook, January.Sources: Author’s elaboration based on INEGI maquiladora statistics.

strongly criticized for employing an overwhelmingly unskilled labor force, for poorintegration into the Mexican economy, and for raising pollution levels. This view,however, is static and does not reflect the profound changes occurring within themaquiladora sector. A more dynamic three-phase perspective can be advanced, whichoffers a much better understanding of the capacity for development within the sector,as exemplified by Delphi’s Mexican growth.

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

138 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

The maquiladora industry in Mexico has been characterized from the outset by lowlevels of domestic content and patterns of subcontracting and vertical integration thatoffer little growth of local supply chains or industrial development. Following a modelof international subcontracting in which decisions concerning production, suppliers,technology, and marketing are taken by parent companies in the USA (Carrillo andHernandez 1985), an association is typically established between the parent companyand the maquiladora operations in which the former takes charge of the knowledge-intensive operations and establishes the technical specifications and the prices of theservices. Meanwhile, the maquiladoras (generally big plants) are limited to carrying outmuch simpler processes (Koido 2003). This productive and technological hierarchyfrequently coincides with poor working conditions and low standards of living wherethe maquiladoras are located. This is precisely because the companies sought torelocate to greenfield sites with an abundance of cheap, docile, non-union labor(Frobel et al. 1981), and to intensively develop operations for unskilled productionin the most marginal sectors (which generate less value in the global productivechain) (Gereffi 1994; Bair and Gereffi 2002).ç3

This situation, however, has varied substantially over time. The maquiladora industryis, at present, one of the Mexican economy’s most dynamic sectors (Table 2),accounting for nearly half of the country’s merchandise exports. Industrial moderniza-tion and job enrichment has resulted in greater productivity and competitiveness formany of the companies involved. The maquiladora industry’s evolution can be dividedinto three stages (Carrillo and Hualde 1998).

First stage (1965–81): productive disintegration and intensification ofmanual work

In this first stage, the maquiladoras maintained slow growth and remained of limitedimportance to the Mexican economy (representing less than 5 percent of manu-facturing employment in Mexico). However, the industry’s evolution was subject tocycles in the US economy, and to a lesser degree to strong pressures from US tradeunions which drew attention to the growing relocation of their members’ companiesand jobs south of the border. At the time, these first-generation7 maquiladorasoccupied the lowest rung within the production chain. This position was associatednot only with assembly activity, but also with the intensification of manual work.Maquiladoras were characterized by the presence of foreign-owned, traditional assem-bly plants, productively disconnected from domestic industry, with low technologicallevels, and dependent on decisions made by their parent companies and their mainclients. In terms of labor organization, they were based on intensive manual labor byyoung women, with rigid job posts and repetitive and monotonous activities requiringa minimum of training (1–3 days) (Fernandez-Kelly 1983). Their competitiveness layprecisely in the relatively low wages (less than one-quarter of US levels) and highwork intensity, resulting in a type of first-generation company that impoverished the

7 By generation we mean an ideal type of firms with a certain socio-technical level. While these designations areessentially metaphorical, they are useful for representing both change over time and the differences between firmsat a given point in time. This approach recognizes the coexistence at any given time of companies of differentgenerations.

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 139

jobs. The productive linkages maquiladoras established locally were very few and farbetween. In contrast, what were strengthened were companies promoting localindustrial development, as well as twin plants (generally warehouses and offices) inthe neighboring cities on the US side of the border. In this stage, auto parts plantshad still not been established.

Second stage (1982–93): industrial modernization, productivespecialization, and rationalization of work

With the strong devaluation of the Mexican peso during the 1980s, substantial changesbegan to occur that sustained the growth of labor productivity and employment inthe maquiladora industry (which expanded from 8.8 percent of total manufacturingemployment in 1985 to 16.1 percent in 1990). New industrial activities emerged, asdid productive specialization in particular districts, such as ‘‘Television Valley’’ inTijuana (Carrillo and Mortimore 1998) and the ‘‘Wire Harness Valley’’ in Juarezç4

ç5 (Carrillo and Hinojosa 2001).8 Furthermore, the spatial concentration of the industrybegan to affect the educational system. As more skilled workers were needed (20percent of the total workforce were professionals and technicians in 1989), plantsbegan exchanges with several universities and technical institutions (Carrillo 1993).

By the mid-1980s, two key changes in manufacturing could be seen, particularly inauto parts plants. First, the introduction of machinery and automated equipmentmoved the maquiladoras beyond simple, labor-intensive manufacturing. Second, theintroduction of new forms of workplace organization raised efficiency and expandedthe role of workers. Just-in-time production and total quality control (JIT/TQC)principles were broadly disseminated, but with high levels of adaptation to the localcontext (the ‘‘hybrid model’’; Abo 1994). These techniques gave workers moreresponsibility on the shop floor, and required greater commitment and involvementfrom them. Although most jobs continued to be organized as basic assembly work,more advanced techniques such as teamwork, group participation, and functionalflexibility were adopted by many maquiladora companies, especially in the auto partsindustry (Wilson 1992; Echeverri-Carrol 1994; Carrillo 1995).ç6

If in the first stage of maquiladora development, transnational electronics companiesbased in the USA promoted this pattern of vertical international subcontractingwithout local linkages, in the second stage the drivers were US automotive companies(mainly GM), and Asian and European transnational corporations (TNCs). Competi-tiveness came to be based on a combination of quality, delivery, unit costs, and laborflexibility. Low wages were still a factor, but of reduced importance compared withthe first-generation maquiladoras.

This second generation represented a true technological and organizational break-through, not only because of their adoption of the Japanese system of production,but also because of the learning dynamics and constant experimentation that they

8 Wire harnesses are an apparently minor component of the automobile industry. Although they represent less than1 percent of the aggregate value of a car, their role is nonetheless much more important. Automobiles are nowcontrolled through complex electric/electronic systems and each function is operated or monitored through acomplex distribution system involving cables, connectors, and electronic sensors. Consequently, wire harnesses areusually referred to as the car’s nervous system.

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

140 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

engaged in (as in the case of Delphi’s Electric Systems plant in Ciudad Juarez). Agreater ability to anticipate demand and respond rapidly to its growing fluctuationsbecame characteristic of these plants. A clear example of their stability and adaptivecapacity in the face of important problems, such as labor mobility, is that these plantswere systematically able to increase competitiveness while experiencing extremelyhigh levels of voluntary personnel turnover of (more than 100 percent yearly between1985 and 2000) (Carrillo 1993; Carrillo et al. 1999). In spite of this high turnover,employment continued to expand, with maquiladoras growing from small andmedium-sized enterprises (148 workers in 1980 per plant) to large facilities (842 in2003). This contradictory process (high employment turnover accompanied bygrowth in plant size and competitiveness) can be explained by (a) a high degree offlexibility in personnel decisions, (b) short introductory training and continuoustraining programs for longer-service employees, (c) the introduction of quality stand-ards like the ISO/QS 9000, and (d) the emergence of a small stable group of skilledworkers and human resource managers.9

Although the flexibility of jobs and workplace activities increased in this generationof companies, the incorporation of highly skilled labor, such as engineers, was largelyabsent. Design processes were limited and the development of clusters was stillincipient. Despite this, young Mexican engineers found in the maquiladora plants asector in which to accumulate knowledge and begin professional careers (Hualde1994). The number of technicians grew from 50,708 to 137,304 between 1989 and1999 to represent 11.4 percent of the total maquiladora employment in Mexico.

Third stage (1994–2001): development of technical centers and knowledge-intensive work

During the early 1990s, new TNC plants were established in the auto parts industry,as well as in electronics. The annual growth of the maquiladora industry reached arecord 20.5 percent in value-added and 14.2 percent in employment between 1994and 2000. Nationally, the maquiladoras represented 31.5 percent of manufacturingemployment in 2000. This tremendous increase was related to both NAFTA and thedevaluation of the Mexican peso. The territorial agglomeration process in electronics(mainly TV and computers) and auto parts continued (Carrillo et al. 1999), but in anindustrial cluster style, characterized by the emergence of intra-firm networks. Delphiand Valeo’s technical centers are clear evidence of this trend.

The third-generation companies are best distinguished from their predecessors bythe completely new type of establishment that emerged, based on different relationsamong companies and different workplace activities. These are productive networksbased on engineers’ specialized knowledge. The plants are no longer oriented eitherto assembly or manufacturing, but rather to the integration of design, research anddevelopment with manufacturing. Thus a process of localized vertical integration hasbegun through the formation of industrial complexes on the Mexican side of theborder. These complexes link up within a given area, connecting engineering centers

9 Approximately 40 percent of the labor force is stable and the remaining 60 percent is characterized by high turnover(Carrillo and Santibanez 2001). Also, most of the workers have previous experience in other assembly plants, whichallows them to pick up new jobs quickly.

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 141

TABLE 3: DISTRIBUTION OF MAQUILADORA PLANTS BY

GENERATIONS

Generations Auto parts Total

‘‘First generation’’ 23% 18%

‘‘Second generation’’ 57% 56%

‘‘Third generation’’ 20% 26%

Total 81 298

Source: Calculated by Jorge Carrillo and Redi Gomis. Survey:‘‘Aprendizaje Tecnologico y Escalamiento Industrial en PlantasMaquiladoras’’, COLEF, 2002. Project CONACYT No. 36947-s‘‘Technological Learning and Industrial Upgrading. Perspectives forDevelopment of Innovation Capabilities in the Maquiladoras inMexico’’, COLEF/FLACSO/UAM.

that supply maquiladora plants, which in turn have specialized direct and indirectsuppliers such as plastic injection molding, machine shops, or IT services, in additionto important all-around suppliers in different regions of the USA. More and morelinkages between different Delphi plants in Juarez are developing.

The case of Delphi’s Technical Center in Ciudad Juarez (MTC) is for the time beingone of the few examples of this process in the maquiladora industry. But MTChas been expanded tremendously, employing more than 2,100 people (60 percentengineers). What is novel about this strategy is that the company has ‘‘discovered’’the advantages of using a relatively cheap, yet highly skilled sector of the labor force:engineers and high-level technicians (whose wages are one-third of their counterpartsin the USA).10

The responsibility, discretion, and knowledge involved in these new companies areof a very high level. Work proceeds on projects based on teams of engineers withtechnical support, which operate under constant pressure to reach better results thanthose of their competitors. In this case, competitiveness stems from the reduction inthe duration of the projects, cuts in operational costs, and high manufacturability ofdesigns due to the technological capability of the engineers, their low relative wages,and the easy communication with their nearby internal customers (in this case,Delphi’s assembly maquiladoras).

To conclude, there have been significant organizational and productive learningtrajectories in many maquiladora auto part plants, resulting in major improvementsin the type of work and rising skill levels. The particular case of Delphi demonstratesthis process of industrial and skill upgrading, as we will see in the next section.

The relative distribution of first, second, and third-generation plants is uncertain,partly because the categories themselves are not precisely definable. But a roughestimate of the size of each group can be made based on survey evidence (Table 3).Depending on the indicator, somewhere between 25 and 30 percent of plants seem

10 To explain this new trend, Lee Crawford, ex-director of Delphi Operations in Mexico and Central America observed:‘‘Delphi has 27 Technical Centers world wide. The pattern is to reduce the number of centers and locate themoutside USA, where clients are located. In the case of Mexico their clients are the maquilas. In some components,such as sensors, it is not necessary to be close to assemblers, but in other products, such as instrument panels,

ç7 yes’’ (interview with author, 5 December 1999).

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

142 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

to be at the technological frontier. This matches the number of plants that claim tobe ISO 9000 certified, operate at the forefront of their product category, upgradetheir equipment and products frequently, and have increased the proportion ofengineers and technicians. At the other end of the spectrum, it appears that around15–25 percent of the plants consistently lag behind. This is roughly the size of thegroup that is three or more years behind in technology, lacks QS 9000 certification,never innovates in equipment and products, and has not increased the number ofengineers, technicians, or hours of training in its plants. These plants are more likelyto compete primarily on the basis of price rather than product quality, and to lookfor locations with abundant supplies of low-wage, unskilled, labor.

3. DELPHI AND CIUDAD JUAREZ: CLUSTER FORMATION AND REGIONAL

DEVELOPMENT

The generational shift in the auto parts maquiladoras can be illustrated through thecase of Delphi in Ciudad Juarez.

Formation of an automotive cluster

Ciudad Juarez has become a nodal point for the automotive sector due to itsgeographic location and high level of industrial specialization. One-third of allmaquiladoras in Mexico are located in the state of Chihuahua, and Ciudad Juarezaccounts for 75 percent of these. In this sense, Chihuahua’s development is based onCiudad Juarez. The three auto giants (GM, Ford, and Chrysler) and their first-tiersuppliers alone account for 68.5 percent of the total industry workforce in this city.

The relocation of auto parts companies associated with the Big Three to CiudadJuarez has prompted foreign competitors to do the same. In other words, theindustrial/territorial agglomeration in this sector has given rise to a productivespecialization in which many companies coexist side by side, but at the same timecompete for a greater share of the market, as well as for skilled and unskilled workers.At the extreme end of the development process is the opening of a R&D center.During the 1990s, GM’s strategy had been to establish its own maquiladoras to supplyboth its own assembly plants and those of other companies. Contrarily, Ford andChrysler have mainly preferred to subcontract production to specialized companies(such as Essex, Lear Seating, or Yazaki) able to supply them with parts like wireharnesses and seat covers. More recently, a transnational process of concentrationhas occurred among first-tier auto parts producers or original equipment suppliers(OES), who now work directly with the major automotive groups or original equip-ment manufacturers (OEMs) like GM, Toyota, Honda, Ford, Isuzu, Mercedes, andBMW.

An important example of this process of productive specialization is Juarez’s wireharness plants. Beginning in 1979, dozens of auto parts companies owned by GM,Ford, Chrysler, Yasaky, Siemens, and Essex, among others, arrived on the scene.Delphi’s Packard division alone employed 33,000 Mexican workers (nearly 27,000 in

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 143

TABLE 4: AUTOMOTIVE MAQUILADORAS, CIUDAD JUAREZ (1987–1999)

1998–1999

Corporation 1987 Plants 1999 Plants 1987 Employment Employment

Delphi 10 14 15,058 26,875

Ford Motor 5 5 6,587 4,617

Chrysler 2 n.d. 2,727 8,332

Yazaki 2 11 2,253 12,348

United Technology Automotive 2 10 2,240 16,076

Electric Wire Products 2 n.d. 1,285 6,888

Lear Favesa 3 5 3,000 12,700

Alcoa n.d. 5 n.d. 4,473

Sumitomo n.d. 6 n.d. 3,200

Strattec Security n.d. 1 n.d 2,072

Siemens n.d. 3 n.d. 2,609

Valeo (previously ITT Automotive) n.d. 1 n.d. 2,650

Johnsons Controls n.d. 4 n.d. 6,329

Robert Bosh n.d. 1 n.d. 785

American Safety 1 1 1,228 1,200

Subtotal 25 67 32,624 120,088

Total 37 n.d. 34,678 n.d.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on Maquiladora Industry Directory, February 1999. Maquiladora Associationat Juarez and Electronic Directory of Export Maquiladora Industry in Mexico, SECOFI, December 2000,Mexico.

Juarez) at the beginning of 1996 (Table 4). Wire harnesses are one of the leadingproducts assembled in Mexico, and the second most exported maquiladora productafter garments, with $4.949 billion of exports in 1998.

The most important wire harnesses are located in the engine and the instrumentpanels; but they can also be found in the door panels, seats, and lighting systems(USITC 1997: 3–19). Typically, wire harness assembly involves numerous productionç8lines in order to accommodate a great variety of vehicle models. Additionally, the finalassembly process incorporates an intricate complex of operations that cannot bepractically or economically automated.

Each plant specializes in a limited range of wire harness sets needed for specificvehicle models. The production of wire harnesses requires flexibility because of rapidshifts in demand (according to the vehicle type, model, and version, as well asfrequent changes in electronic components and designs). A simple car is connectedby thousands of wires that measure more than a kilometer and half. Therefore, thedesign techniques and capacities to connect wire harnesses are essential to obtainmaximum efficiency using minimal space (Sumitomo 1998). Typically, wire harnessesç9form what might be thought of as the central nervous system of a car, consisting of13 subsystems.

Historically, the evolution of the wire harness sets for vehicles can be broken downinto three periods, as Lara (1999, 2003) points out: the simple wire harness (1900–ç10

73), the harness as central nervous system (1974–93), and the harness integrated inmodular systems (1994–). First-generation wire harnesses were exclusively a meansof transmitting electrical power. Between 1910 and 1919 wire harnesses were

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

144 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

developed to control the electric lights and starter systems. By the middle of the1950s, the rise of air conditioning necessitated modifications in wire harnesses totransfer more power and include a greater number of wires, requiring automobiles tocarry three bunches, or subsystems, of harnesses.

In the beginning of the 1970s, the rapid diffusion of electronic components led tothe design of more complex combustion systems—fuel injection and the ‘‘travelcomputer’’—(due to the growing maturity of semiconductor and integrated circuitmanufacture, and the growing demand for energy-efficient and less polluting vehicles).The use of electronic components was expanded, as was the electric/electronic (E/E) system, so the number of wire harnesses was increased from 3 to 12 per vehicle.This convergence of the automobile and electronic sectors resulted in: (i) theappearance of new functions and new E/E components, (ii) the substitution ofmechanical parts for E/E parts, and (iii) the combination of mechanical parts with E/E components. With the growing number of electronic components demanding avariety of electrical loads, a wider range of wire harnesses were needed. During thisperiod, therefore, the wire harness was transformed from a marginal component tobecome the central nervous system of the vehicle.

Finally, from 1970 to 1990 wire harnesses were almost entirely redesigned toaccommodate the introduction of new and improved electronic components. At theend of the 1980s, Koido (1992) observed that:

minor automobile model changes every year affect the wiring harness designs and leadto modifications in the production process. Moreover, small changes in some electronicparts can prompt changes in wiring harness design even in the middle of a car model year.

Today, the average automobile integrates 14 types of harnesses, each related tospecific E/E components. In addition, a vehicle can require more than 40 electricsubsystems. The number of cables for each automobile is variable and depends onthe size of the engine: 800 cables for 1,500 cm3 and 1,500 cables for 2,500 cm3, forexample. Each wire harness uses roughly 100 types of different connectors and thereexist more than 200 types of terminals (Lara 2000). This complexity is leadingç11

assemblers and auto parts makers to: (i) adopt module designs, (ii) substitute fiberoptics for copper, and (iii) to develop multiplex systems. In order to managethese continuous changes, firms need to develop open and flexible wire harnessarchitectures (Lara 1999). Approximately 80 percent of the new designs representç12

ç13 variations on previous designs (Gilson 1999).This process, together with modular production, requires the increased proximity

of: (i) the centers that design and develop E/E components, (ii) the centers thatmanufacture E/E components, and (iii) the centers or plants that manufacturewire harnesses. Third-generation harnesses are qualitatively different in architecture(variability/stability) from the unstable harnesses of the second generation. Theignition wire harness sets developed by the mid-1990s can also be considered thirdgeneration because of the emergence of R&D and technical support centers that cantranslate customers’ heterogeneous requirements into the manufacturing processesof their nearby suppliers (Lara 2003).ç14

A good example of such supply chain integration is the MTC, which designs forseveral OEMs and is closely linked with Delphi’s Electric Systems and Switching (SEC)

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 145

plant in Juarez, as well with the rest of the group’s manufacturing facilities in Mexico.In other words, MTC functions as the hub of an intra-company network in order tocoordinate multiple functions for Delphi and other OEMs (Lara and Carrillo 2003).

The process of agglomeration and cluster formation has received support fromgovernment institutions and, more substantially, from private economic groups in thestate of Chihuahua. Together, they formed the Chihuahua Siglo XXI (Chihuahua 21stCentury) project in 1994, based on promoting clusters. This was possibly the firstMexican initiative with this focus (which preceded the adoption of industrial policiesaimed at strengthening productive chains—see the Industrial Policy and Foreign TradeProgram of 1996); although the state government participates, it is clearly an initiativeof Chihuahua’s private business groups. Among its goals is to transform Chihuahuainto a state with an intensive knowledge-based economy, with nuclei of high value-added manufacturing plants supported by the production of complementary materialsand services (DRI/McGraw-Hill 1994). This program mainly targets the cluster ofautomotive and electronic plants in Ciudad Juarez as the basis for the state’s develop-ment. The most recent federal government program (the National Development Planfor 2001–2006) also focuses on industrial clusters as the most dynamic sector of theMexican economy.

In 1998, Chihuahua Siglo XXI was folded into a new program (Chihuahua Now)and a number of results were achieved. The most important was the improvement ofinstitutional capacities and the creation of a consensus among local economic groups.However, managers interviewed observed that the precise scope and modalities ofthis program remained vague. It also suffered from a broader skepticism about thecredibility of government policy initiatives, despite having been initiated in large partby private economic groups. The key problem identified by Carrillo et al. (2001) wasthe lack of financial resources for supplier development and training programs.Additionally, the program was unable to identify problems such as the weak ‘‘associa-tionalism’’ and lack of managerial leadership in the region. Despite these weaknesses,Siglo XXI and Chihuahua Now established the basis for future strategic initiativesand institutional capacity building. The state of Chihuahua is, without a doubt, oneof most important industrial areas in Mexico and a creative milieu for local economicdevelopment (see, for example, the 2003 Juarez Strategic Plan at www.planjuarez.org).

A second-generation maquiladora: Delphi’s SEC plant

The case of Delphi-Energy Electric Switching Systems (SEC) plant exemplifies thelearning process of what we have termed second-generation maquiladoras. Thiscompany was established in 1980 to produce solenoids, sensors, and switches. By1993, the plant’s sales had reached $385 million, with 87 percent of its productionexported to the North American market (including Canada) and the remainder soldwithin Mexico and other countries. As can be seen from Table 5, in 1995 the plantproduced 20 million solenoids and 17 million sensors, clearly demonstrating its statusas a mass-production facility.

This plant improved its competitiveness in the 1990s because it was able to respondefficiently to changes in technology and demand with high-quality products. Thecompany has received QS 9000 certification and other awards such as Ford’s Q1. SEC

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

146 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

TABLE 5: JUAREZ CLUSTER MAQUILADORA PLANTS OF DIFFERENT GENERATIONS

Variables SEC (2nd generation) MTC (3rd generation)

Year of start 1980 1995

Parent company Delphi-Electronics Delphi-Electronics

Number of plants in Mexico 2 3

Foreign capital 100% 100%

Capital investment ($ million) 150 150

Total sales in 1995 ($ million) 450 0.40

Production costs. Share of incomes 15% —

Percentage of exports 100 100

Principal market USA (80%) USA (80%)

Principal product Solenoids, sensors, and valves Solenoids, sensors, valves, wire

harnesses, etc.

Volume of production (all 1995) 20 million (solenoids) 12 (projects)

17 million (sensors)

Total employment (June 1999) 4,000 1,700

Percentage of production workers 80% 10%

Percentage of engineers 7% 90%

Labor cost (from the total cost) 5–10% Not available

Daily activity of the plant 24 hours (3 shifts) 24 hours (8 shifts)

Main activity Assembly Design

Manufacture Development

Principal location of main Mexico USA

competitors

Principal competitor Siemens Bosh

Principal problem of the plant Customs procedures in Mexico Border transport

Principal role of the plant Produce to a high quality R&D

Competitive situation Improved Shortened delivery time

Main competitive advantages Quality products —

Principal pressure on improved Time reduction Time reduction

competitively

Principal responses to competitive Increase specialization Incorporate more R&D activities

pressures (more components or systems)

Medium term projects Increase exports Expand installed capacity

Introduce new products Increase exports

Open new plants Introduce new products

Establish alliances with national and Open another plant

foreign producers Establish alliances with national and

foreign producers

Decision making in the plant Components supply Selection of production and

Quality control processing technology

Purchase of equipment

Volume for export

National suppliers

Indirect suppliers

Provision of incentives

Financial operations

Merchandising

Main categories of components Plastics/metals/cardboard Plastics/wires

No. of suppliers 273 Subsidiaries in 30 countries (5 main

components)

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 147

TABLE 5: Continued

Variables SEC (2nd generation) MTC (3rd generation)

No. of suppliers in Mexico 2 4

Percentage of national content 1% 1%

Main obstacle to increase the use Little trust in programmed delivery Lack of price competitively

of national suppliers

Significant changes in practices None mentioned JIT implementation

followed by suppliers

Sharing of information with Quality control methods/JIT/quick Quality control methods/JIT/quick

principal suppliers: response response

Product information Product information

Demand forecasts Demand forecasts

Production plans Production plans

Source: Author’s elaboration based on personal interviews.

has nearly 100 clients, of which the most important are two Ford and two GM plantsin the USA. To improve its competitiveness, the plant has struggled to reduce itsdelivery times and shorten production cycles through enhanced specialization andthe adoption of new organizational practices. In particular, the plant has increasedtraining per worker to an average of 70 hours a year (the manufacturing industryaverage nationwide is around 40 hours).

In 1996, the plant had 4,200 employees, of whom 85 percent were productionworkers and 7 percent were engineers and technicians. Wages and benefits repre-sented less than 15 percent of the total cost of production, which was 70 percentautomated in terms of value. The plant has also adopted Japanese productionmethods. In 1982, Statistical Process Control was introduced and, as of 1988, JIT/TQC techniques were implemented, including teamworking, quality circles, andcellular manufacturing, among others. This was the first maquiladora plant to employmore male workers than women, to implement new ideas on synchronized manu-facturing (JIT, U-shaped cells, factories within the factory), and to diversify itsproducts. At the present time, it handles 18 inventory turns per year. This allows usto understand why the most far-reaching changes affecting the plant, which beganwith the onset of NAFTA, have occurred precisely in the field of development anddesign, both of products and processes.

A third-generation maquiladora: Delphi’s Juarez Technical Center (MTC)

Delphi Energy Division, the MTC’s parent company, is located in Warren, Ohio.Nevertheless, MTC works for all six divisions of Delphi and employs staff from thesedivisions as well as other independent component suppliers. Delphi-Energy decidedto relocate one of its seven R&D centers outside the USA for the first time in itshistory. Thus, the Anderson, Indiana plant (1,800 miles away) was transferred toJuarez. This strategic decision resulted from the need to reduce production cycles,delivery times, and total costs. While Delphi-Energy engineering centers employ 500people on average, the MTC currently employs more than 2,100. In the first year of

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

148 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

operations it was able to cut total costs by 60 percent and delivery time by 20 percent(compared with the Anderson plant).

The MTC opened in 1995 in Juarez as ‘‘just another maquiladora’’, with an initialinvestment of $150 million (slightly less than half devoted to equipment). Mexicanengineers and technicians were sent to GM’s Anderson center for several months toreceive the necessary training in critical areas. This was a completely new type ofoperation for Mexico, responsible not just for the production of specialized autoparts, but for integrated design and manufacturing. This center is expected to providea ‘‘full package’’ service, covering everything from a general idea (even ‘‘before there’sanything on paper’’), to development of the complete product and manufacturingsystem, including the actual production lines.

The decision to relocate the MTC to Ciudad Juarez was strategic for GM. Accordingto managers interviewed, it depended on three critical factors: (a) proximity to theUSA; (b) 15 years of learning experience in the maquiladora plants of Ciudad Juarez;and (c) the quality of Mexican engineers’ knowledge of the field. The underlying aimwas to reduce project development cycles and delivery times by moving engineeringcloser to manufacturing facilities.

Juarez has a considerable workforce available with many years of experience in theauto parts sector. Although the training of engineers and technicians was not sufficientto fill the demand for skilled workers in the region, high labor mobility helps inrecruiting potential employees. In the field of education, the state of Chihuahuasupports universities and technological schools offering a variety of engineeringcourses with content developed to meet industry needs; there is even an importantresearch center on materials in the city of Chihuahua itself. GM evaluated the localpool of engineers available to be hired by the MTC, and concluded that they wereextremely competent.

We will now examine three areas of great importance in this center: production,human resources, and supply chains, in order to understand the learning process andthe evolution of local capabilities.

The center’s operations are based on the formation of variable project teams,following a full-package strategic plan comprising four phases. The first phase is thebeginning of the idea. The client presents his request, in which often ‘‘. . . he doesnot even exactly know what he wants, but rather has an approximate idea of hisneeds’’. The second phase involves designing the project by drafting a proposal basedon an initial concept and establishing different work teams. At this stage, the centerworks closely with the client. The third phase is the validation of the product. Oncethe prototype is approved, the necessary equipment is purchased or adapted forconstructing and validating the concept. ‘‘Now we are no longer dealing with samples,but with dozens of pieces (500 for example).’’ At stake is the manufacturability of thedesigns. The production equipment is produced or designed (the measuring andother equipment is validated) and the manufacturing infrastructure is installed. Thelayout, manuals, etc. are designed. In other words, assembly lines are designed,constructed, and equipped with machinery, tools, etc. At this stage, for example, theSEC’s manufacturing unit was designed. The fourth phase consists of continualimprovement in product designs and prototypes as well as their manufacturability.

MTC began by hiring 20 percent foreign engineers and technicians and 80 percent

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 149

Mexicans. Initially it had 370 employees (90 percent of whom were engineers). MTCwas the first technical center to achieve QS 9000 certification, becoming in effect atraining center and example for other centers throughout the division.

The center has four salary categories and many variations within them. Althoughthe monthly wages of $900 plus benefits are relatively high in the local context,salaries are only slightly above those paid in other maquiladoras (for engineers) andidentical to those of their customers (the engineers working in SEC). In any event,salaries are not the only reason why many engineers wish to work in the MTC:opportunities for decision-making initiative are also important.

Despite a domestic content of only 1 percent, the MTC is no technological island,but is instead integrated into a local intra-company system (Figure 4). This third-generation facility represents an industrial breakthrough. As one manager engineerpointed out: ‘‘. . . in the maquiladoras, the recipes continue, we make them here . . .we’re dealing with the design industry’’.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The story of GM and Delphi in Mexico, especially in Juarez, shows a clear trajectoryof industrial upgrading. OEM and OES firms have been able to develop morecompetitive structures and organizational forms, and improve performance levels. Inthis process local private actors as well as public institutions have played an importantrole in stimulating the formation of the auto industry cluster. Furthermore, NAFTAhas sparked the growth of new plants and employment, closely integrated withproduction in the USA and Canada. Nevertheless, this upgrading process has notgiven rise to a balanced pattern of endogenous regional development.

General Motors and Delphi have been operating in Mexico for more than 60 years.During the company’s first 30 years in the country, its Mexican operations’ mainfunction was to assemble automobiles for the domestic market; during the next 30years, their central role was to produce vehicles, engines, and auto parts for export.In this latter period, new modern plants have been built to manufacture automobiles,trucks, engines, and electrical system components. This period has also seen animportant geographic decentralization of production, extending to practically theentire country—as can be seen from Figures 1 and 2. All this has allowed GM tosubstantially increase its presence in Mexico, particularly through its Delphi spin-off.As we have seen, Mexico plays a central role in the global strategies of this first-tiersystem integrator.

There is no doubt that the final assemblers, as well as the auto part maquiladoras,have undergone industrial upgrading, particularly at a technological level. But techno-logical sophistication does not guarantee competitiveness. Still, firms that are at thetechnological frontier of their industry and that compete successfully in an inter-national arena, where national policies offer little in the way of protection, are morelikely to succeed in the long run. Third-generation plants are at a competitiveadvantage relative to second and especially first-generation plants, because they caninnovate in products and processes, apply best-practice management techniques, andcompete on the basis of quality.

Although Delphi’s auto parts strategy in Mexico has been one of productive

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

150 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

specialization based on the establishment of maquiladora plants using labor-intensiveprocesses, one can observe a learning dynamic that ranges from the assembly processto R&D. The jobs that have most enriched the maquiladoras’ tasks and activities arethose of technicians, engineers, and managers in second and especially third-genera-tion facilities. Skill upgrading is reflected in an increase in earnings, since thesecompanies provide higher wages than do others in the area. However, the supplychains that these companies develop locally are limited. Thus, while in areas such asJuarez, the industrial cluster is based on a network of plants and companies belongingto the same corporation (vertically integrated, with strong horizontal support ser-vices), few Mexican companies have been able to participate in this process, withthe exception of low value-added activities like cardboard packaging and machineshop parts.

Accompanying this process of firm and labor upgrading, cities such as Juarez havenot only experienced an explosive growth in maquiladora plants and employment,but also of secondary and tertiary educational institutions, professional businessservices, and quasi-governmental development agencies such as the Chihuahua SigloXXI program, among others. But the integration of local Mexican suppliers to Delphiplants has, unfortunately, been limited, mainly because of the former’s low quality,small scale, delivery problems, and high costs, as well as a lack of support from thelatter.

More generally, strategic initiatives in Juarez, such as Siglo XXI and ChihuahuaNow, have failed to improve supplier development, but other gains have been made,such as the improvement of institutional capacities. Now, the Mexican governmenthas initiated plans to double supplier capacity in the auto parts sector. However,Mexican-owned suppliers do not currently operate in the first or second tiers of theautomotive supply chain. Most instead provide production services to foreign-ownedsuppliers, as in the case of local machine shops.

According to the TNCs themselves, public policies have had a small impact onlocal suppliers. A TNC manager underlined that: ‘‘The state and federal governmenthave had little or nothing to do with the development of local suppliers’’;

We have come close on occasions, they [the state government] have even come topromote supplier fairs, but we are basically in charge of searching for input suppliers[. . .] as in the case of chemical compounds, which we now have to buy in Monterrey. . . it is an initiative of ours that is carried out via personal networks.

Public policies have not had the desired success for a variety of reasons: manyfirms are insufficiently familiar with the available support services; funding is limited;some policies are inappropriate, while others have low rates of efficiency; there areno systematic policy evaluations and sometimes there are no evaluations at all. Mostfundamentally, government agencies at all levels (national, state, local) do not appearto consult TNCs and suppliers regularly, while the latter do not fully believe in thepolicies themselves, which they consider bureaucratic and inefficient. Although theadvances in industrial development policies should be acknowledged, it is now moreimportant to be clear about their weaknesses and the limited progress that has beenachieved.

Finally, the weak linkages of transnational automotive and component firms with

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 151

the wider Mexican economy described above are by no means unique to this sector.Across a range of industries, sourcing from Mexico is based primarily on agreementswithin and between TNCs, while indigenous supplier firms face scale, price, delivery,productivity, and technology problems (Miker Palafox 1996; Ramırez 1997; Altenburgç15

ç16 et al. 1998; Carrillo and Gonzalez 1999). Although foreign-owned subsidiaries repre-ç17sent an important vehicle for the modernization of the Mexican economy, theirç18transnational character also represents an important constraint on their contributionto a more balanced pattern of endogenous regional development.

Although there is great optimism within the governmental sector and businessorganizations about the future of the Mexican auto parts industry, the developmentof independent local suppliers has been limited. Emerging countries such as Chinarepresent an important challenge for Mexican production. Delphi, for example, hasalready established wire harness plants in China, while GM invested $60 million inan Indian technical center in 2003. So Mexico’s status as a major auto parts producercould erode in the near future. The future depends not only on TNCs’ investmentdecisions but also on the Mexican government’s industrial policies and new regionaldevelopment initiatives by various combinations of public and private actors. Theconsolidation of regional industrial clusters would be the best strategy to counteractthe current trend of plant closings and reduced foreign direct investment. Theopportunities for, and challenges to, consolidation of the Mexican auto parts sectorare considerable. More research and wider participation by all the actors involved inthis process are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank CONACYT for their support in the realization of thisproject and is grateful for the further support of the Auto Part National Industry (INA)and the Mexican Association of Automobile Industry (AMIA). I wish to thank themanagers of the maquiladora firms for interviews, information, and access to theirfacilities, especially those of Delphi-Mexico. I also want to thank Jonathan Zeitlin andJeff Rothstein for important comments and help with revisions.

REFERENCES

Abo, T. (ed.) 1994: Hybrid Factory. The Japanese Production System in the United States.New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aguilar, I. 1996: Competitividad, flexibilidad y rotacion de personal en la industriaç19

maquiladora del televisor en Tijuana. Thesis, Regional Development Masters Program, ElColegio de la Frontera Norte, Tijuana.

AMIA (several numbers) Asociacion Mexicana de la Industria Automotriz, A.C. Boletın organoinformativo mensual, Mexico.

Bancomext 1997: La globalizacion de la industria automotriz: retos y oportunidades paraç20

Mexico, Bancomext 60 Aniversario, Tercer Ciclo de Conferencias, Bancomext, Mexico,4 June.

Bordenave, G. and Lung, Y. 2002: The Twin Internationalization Strategies of USCarmakers GM and Ford, IFREDE-E3i, Universite Montesquieu Bordeaux IV, Bordeaux(Working Paper 2002–1).

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

152 INDUSTRY AND INNOVATION

Boyer, R., Charron, J., Jurgens, U. and Tolliday, S. (eds.) 1998: Between Imitation andç19

Innovation: The Transfer and Hybridization of Productive Models in the InternationalAutomobile Industry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carrillo, J. (ed.) 1993: Condiciones de empleo y capacitacion en las maquiladoras deexportacion en Mexico. Tijuana: Secretaria del Trabajo y Prevision Social and El Colegiode la Frontera Norte.

Carrillo, J. 1995: Flexible production in the auto sector: industrial reorganization at Ford-Mexico, World Development, 23(1): 87–101.

Carrillo, J. and Hernandez, A. 1985: Mujeres fronterizas en la industria maquiladora.Mexico: Secretarıa de Educacion Publica y Centro de Estudios Fronterizos.

Carrillo, J. and Hualde, A. 1998: Third generation maquiladoras? The Delphi-General Motorscase, Journal of Borderlands Studies, 13(1): 79–97.

Carrillo, J. and Ramırez, M.A. 1997: Reestructuracion, eslabonamientos productivos ycompetencias laborales en la industria automotriz en Mexico, in M. Novick and M.A.Gallart (eds.), Competitividad, Redes Productivas y Competencias Laborales, pp. 193–234. Montevideo: OIT/CINTERFORD/Red Educacion y Trabajo.

Carrillo, J. and Santibanez, J. 2001: Rotacion de personal en las maquiladoras, 2nd edn.Tijuana: Secretarıa del Trabajo y Prevision Social and El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, Plazay Valdez Editores.

Carrillo, J., Mortimore, M. and Alonso, J. 1999: Competitividad, y Mercados de TrabajoEmpresas de Autopartes y de Televisores en Mexico. Mexico: Plaza y Valdez Editores,Universidad Autonoma de Ciudad Juarez y Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana.

Carrillo, J., Miker, M. and Morales, J. 2001: Empresarios y redes locales. Autopartes yconfeccion en el norte de Mexico. Tijuana: Plaza y Valdez Editores.

CIMEX-WEFA and Global Insight 2003: Maquiladora Industry Outlook, January.COLEF 2002: Encuesta Aprendizaje Tecnologico y Escalamiento Industrial en Plantas

Maquiladoras, Departamento de Estudios Sociales, COLEF, Tijuana.Cruz Guzman, J. 1995: Implicaciones del cambio tecnologico y organizacional sobre la fuerza

de trabajo en General Motors (Planta Distrito Federal), in A. Arteaga (ed.), Proceso detrabajo y relaciones laborales en la industria automotriz en Mexico, pp. 111–137.Mexico: Fundacion Friedrich Ebert, Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa.

DRI/McGraw-Hill y SRI International 1994: Chihuahua: Mexico’s First 21st CenturyEconomy, Chihuahua: Ed. Gobierno del Estado de Chihuahua, Desarrollo Economico delEstado de Chihuahua and Desarrollo Economico de Ciudad Juarez.

Echeverri-Carroll, E. 1994: Flexible linkages and offshore assembly facilities in developingç21

countries. Unpublished paper, School of Business, University of Texas at Austin.Fernandez-Kelly, M.P. 1983: For We Are Sold, I and My People: Women and Industry in

Mexico’s Frontier. Albany: State University of New York Press.Frobel, F., Jurgens, U. and Kreye, O. 1981: La nueva division internacional del trabajo.

Mexico: Siglo XXI.Gambrill, M.C. 1980: La fuerza de trabajo en las maquiladoras. Resultado de una encuesta yç19

algunas hipotesis interpretativas, Lecturas del CEESTEM. Mexico: CEESTEM.Gereffi, G. 1994: The organization of buyer-driven global commodity chains: how US retailers

shape overseas production networks, in G. Gereffi and M. Korzeniewicz (eds.),Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism, pp. 95–122. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Gonzalez, S. 1996: Estrategia corporativa y operacion local en las principales empresasautomotrices instaladas en la zona de Toluca, Research Report. Toluca: UniversidadAutonoma del Estado de Mexico, January.

Hualde, A. 1994: Mercado de trabajo y formacion de recursos humanos en la industria

IAI111P010 FIRST PROOF 02-03-04 20:09:27 AccComputing

TRANSNATIONAL STRATEGIES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 153

electronica maquiladora de Tijuana y Ciudad Juarez, CONACCYT Research Report.Tijuana: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

INEGI (several years) Estadısticas Mensauales de la Industria Maquiladora de Exportacion.Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadıstica, Geografıa e Informatica.

Koido, A. 1992: Between two forces of restructuring: US–Japanese competition and thetransformation of Mexico’s maquiladora industry. Unpublished PhD thesis, Johns HopkinsUniversity.