Tibet from Buddhism to Communism

Transcript of Tibet from Buddhism to Communism

Heather Stoddard

Tibet from Buddhism to Communism*

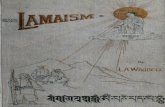

The conflict between Mohammed and Marx has received a fair amount of scholarly attention; so have the occasional attempts at syncretism, fusing the two visions. The confrontation of Buddha and Marx is just as interesting, and has been explored rather less. There are certain parallels between Buddhism and Islam. Both contain a High Tradition of great, scholarly sophistication which lends itself to purification, and can con- stitute the banner of political and spiritual ‘Reform’ and revival. This has in fact happened within both Islam and Buddhism. But within the two most thoroughly Buddhism-dominated societies, Mongolia and Tibet, the process was not allowed to run its course. Each of these countries has a small population, and in each case what might have been the natural internal develop- ment was distorted by the overwhelming might of a great communist power. In neither case, however, has the victory of Marx over Buddha been complete or uncontested. The crucial events did not happen simultaneously in the two countries, but happened about three decades later in Tibet than they had in Mongolia. The present article contains insights into and information about the last years of the ancien regime in Tibet, based on unique understanding and research opportunities.

E.G.

IN EARLY FEBRUARY 1946, THE PRINTERS THACKER SPINK & Co. Ltd of Calcutta received the first of a rather surprising series of orders: - 4,000 applications for membership of the Tibetan Pro-

- 2,000 membership cards. gressist Party,’ plus

*This article is an English extract of the first part of Le Mendiant de Z’Amdo, Gedun Chompe2 ( I 905-1 951 ), SociCtk Ethnographique, Universitk de Paris X, Nanterre 92001, France. This study will be published at the beginning of 1986.

1 The Tibetan Progresskt Party was originally formed in 1939, in Kalimpong, India, by Rabga Pangdatshang, Kunphel-la and Changlochen, see below p. 90.

T I B E T : T R A N S I T I O N F R O M BUDDHISM T O COMMUNISM 77

This was soon followed by a letter, asking for a revision of the contents of the application form, and accompanied by a drawing of the party insignia. The design, representing a sword, a scythe and a weaver’s loom, against a snowy mountain, though obviously inspired by Soviet models, was quite original. In March a further order of 4,000 of the revised entry forms was made. Thacker Spink & Co. Ltd were not to mark their name on the documents, but apart from this, no attempt at secrecy was sought by the distinguished Tibetan who paid several visits to the printing house.

There had been much discussion in the Indian newspapers concerning the liberty of forming political parties and although no reply had been given by the government of Bengal to the request of Rabga Pangdatshang, a leading eastern Tibetan intellectual,* he went ahead, taking the word of the media on faith and in the frontier town of Kalimpong in India founded the first Tibetan political party in exile.

Apart from a few vague reference^,^ no one has yet discussed openly the rise and fall of the Tibet Revolutionary Party and the overriding impression is that the subject is, or has been, taboo, at least in Tibetan expatriate circles if not also in the West and in the People’s Republic of China. However, having made a detailed study of military and political developments in the first half of the century, taking the progressive current as a

* Eastern Tibet is divided up into two traditional provinces, Kham and Amdo, natives of each being known respectively as Khampa and Amdowa. Rabga Pangdatshang, who came from one of the most wealthy Khampa trading families, made a formal request to the Bengal government concerning the formation of his party (Kalimpong is in Bengal), as he apparently did not wish it to be a clandestine organization.

3 Rakra bKras-mthong Thub-bstan Chos-dar, dCe-’dun Chos-’phel gyi Lo-rgyus, Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, LTWA, Dharamsala, 1980, pp. 102-105: ‘Apho Rabga etc. . . had founded a party, called the Tibetan National Congress, or something like that . . . and had offered a programme of revolutionary reform, in harmony with the times, and in order to defend the government’. See also the very vague references to Rabga’s political activity in A.W. Radhu, Carauane Tibitaine, Paris, Fayard, 1981, pp. 171-72, and K. Dhondup, ‘Gedun Chompel, the Man Behind the Legend’, in Tibetan Review, October 1978, pp. 12-13. W.D. Shakabpa, in Tibet. A Political History, Yale University Press, 1967, does not mention the existence of the party, neither in the English version, nor in the extended Tibetan version, Bod kyi Srid Don rcyal-rabs. An Advanced Political History of Tibet, Delhi, 1976.

78 GOVERNMENT A N D OPPOSITION

central theme, I feel it is quite legitimate to initiate a discussion of the subject, with the hope that new materials and viewpoints will be f o r t h ~ o m i n g . ~

The very word ‘transition’ used in the title raises the question as t o the nature of the change in the Tibetan government that was to have such dramatic consequences in the 1950s and 1960s. It is usually presented as the abrupt upheaval of an ancient traditional society, violently propelled into the twentieth century. In many ways this is true. On the one hand, the change is held to have been imposed from the outside by the invading troops of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, who took by surprise a peaceloving and unsuspecting population, and an ecclesiastical government, crushing mercilessly with modern weapons a spontaneous unarmed popular uprising. On the other hand, we are told that the ‘liberation’ from Western imperialism took place in a peaceful manner, with minimal resistance from the Tibetan population, who in fact welcomed the PLA with open arms and much rejoicing, since at last they could rejoice the great Chinese motherland and free themselves from the tyranny of a cruel and despotic clergy.

I t is the purpose of this study to question both these extreme views which for divergent reasons agree in supporting a sudden transformation, directed from without, thus absolving the ruling elite of their very real responsibility and ignoring an internal process of political awakening that had begun with the accession to power in 1893 of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, whose reign was to last until 1933.

We shall therefore examine the careers of a heterogeneous cluster of individuals, originating on the whole from the peripheral areas of the Tibetan plateau, whose orientation was towards a new ‘real’ Tibet, where ecclesiastical rule would be replaced by a modern socialist government. We would underline that in our view it was less British imperialism or Chinese com- munist evangelism that was the cause of the ‘transition’, but

4 See Heather Stoddard, Le Mendiant de I’Amdo, see title note, p. 76. Melvyn Goldstein of Cleveland is preparing a very extensive political study of the period and Chie Nakane, o f Tokyo, a study of the nobility in the fust half of the twentieth century. Both publications are awaited as important contributions to our under- standing of the internal political processes in Tibet during this period.

TIBET: T R A N S I T I O N F R O M BUDDHISM T O COMMUNISM 79

rather more deep internal divisions, political and psychological, exacerbated by an effete, incompetent and hesitant Tibetan ruling hierarchy, bound tightly to the path of ‘conservative sanity’, paradoxically by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama himself.

THE T H I R T E E N T H DALAI LAMA

I say paradoxically, since it was the Thirteenth Dalai Lama who from early on in his reign showed himself, in spite of a strong autocratic trait in his character, to be an open-minded reform- ist who desired above all else to guide Tibet securely into the twentieth century, redefining her boundaries and giving her a strong army capable of defending them. He created a number of the formal accessories of statehood: a national flag: ministries of war and foreign affairs; a mint; postal and telegraph services; as well as the beginnings of international commercial agree- ments. He also revised a number of laws, lightening the burden of corvke imposed on an impoverished population in Central Tibet, and abolishing capital punishment.

Already in the 1890s, he had invited a group of gunsmiths from the Kalimpong-Darjeeling area to Lhasa to improve the arsenal.6 British aggression in Sikkim and against Tibet itself in 1888 was no doubt the prime reason for this. Early on Dorjiev,’ the notorious Bury at scholar-cum-Russian emissary, probably had a strong influence on him, and his own lack of personal security - he survived at least attempted assassination around the time of his accession* - would perhaps have heightened his

5 India Office Records, L/Political & Secret/12.4167. Coll. 36/4, Flag of Tibet, 1923.

6 See a photograph of the gunsmiths at the arsenal in Lhasa in the early 1920s, C. Bell, Tibet Past &Present, Oxford, 1924, opp. p. 192.

7 Agvan Dorjiev (1849-1938), see Le Mendiant de Z’Amdo, op. cit., Ch. 11. De- scribed as a Russian spy by most Western writers, he played an important role in the little known pan-Mongol movement of the early part of this century, and was a highly respected Tibetan Buddhist scholar, and close intimate of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama.

8 See Ekai Kawaguchi, Three Years in Tibet, Bibliotheca Himalayica, Ratna Pustak Bhandar, Kathmandu 1979, pp. 375-82, for a graphic description of the punishment accorded t o the conspirators. Also W.D. Shakapba, op. cit., p. 195, and Tokan Tada, The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Tokyo, Toyo Bunko, 1965, pp. 104-105.

80 GOVERNMENT A N D OPPOSITION

interest in weaponry. During his flight from the British to Urga in Mongolia, in 1904, and the following visit to Beijing, under pressure from both the Manchu and the British government^,^ he acquired a considerable amount of military information, meeting Russian, German, Japanese and other foreign diplomats, specifically questioning them on the training of armies and their defence systems.

Before his fleeting return to Lhasa in 1909, after four years of exile in China and Central Asia, he had created a new cabinet, composed of independentist ministers, who fled with him to India in 1910, with a Chinese price on their heads and a Chinese army on their heels. Before his final return to Lhasa in 1912 he had set up a Ministry of War. The close association of the military and financial departments from this time on until the death of the pontiff in 1933 bears witness to the sustained and growing awareness amongst his close associates of the impor- tance of defence.

The favour accorded by the pontiff to several eastern Tibetan Khampa families - notably the celebrated Pangdatshangs - enabled them to acquire considerable wealth and influence in Tibetan society in the first half of the century. They joined with and stimulated a rising class of merchants and encouraged the development (though still in its very early stages) of a new bourgeois intelligentsia. This favour was in the first place inspired by the Khampas’ faithful protection of the Dalai Lama’s person during his flight to India from the invading armies of Zhao Erfeng. Half a century of intermittent warfare between Chinese and Tibetans in the Sichuan/Kham border region had been crowned with the arrival on the scene in 1905 of the silent and efficient ‘Butcher Zhao’” who brought two quite new elements into the history of Sino-Tibetan relations: the destruction of Tibetan Buddhism and the colonization of the Tibetan plateau by the poor peasants of Sichuan.

The plateau was now to be divided and assimilated into three regular Chinese provinces: Qinghai, Xikang and Central Tibet,

9 Parshotam Mehra, Tibetan Polity. 1904--1937, Wiesbaden, Otto Harrassowitz, 1976, p. 14; T. Tada, op. cit. pp. 49-55.

Z’histoire du Tibet, Paris 1962, p. 112, for an account of the arrival of Zhao Erfen’s forces at Lhasa, and for a personal appreciation o f the ‘Butcher’.

10 See Jacques Bacot, Introduction

TIBET: TRANSITION FROM BUDDHISM TO COMMUNISM 81

and rapidly colonized. The fervently religious and ferociously independent Khampas, who bore the brunt of this double offensive, launched from Sichuan, and caused directly by the British Younghusband expedition in 1904,” were only too pleased to co-operate with the spiritual and temporal leader in his new frontier defence policy. That this was not easy to implement for numerous reasons, not least the internal divisions amongst the Khampas themselves, does not detract from the fact that from this period onwards, close links are maintained between the mint, the army and the frontier troops.

By the mid 1920s the Dalai Lama made a perceptible swin away from his earlier progressive sway and from militarization. 1 8

Perhaps it was due to the everlasting ambiguity of British ‘aid’, always obstructive as far as weaponry was concerned, coupled with an attempted coup de force made by the young noblemen trained as officers by the British army in Quetta. They burst into the A ~ s e m b l y ’ ~ in full session one day in 1925, demanding military representation. For the clergy, they had gone too far. They were invited, shortly after this, to a ceremonial tea, where the pontiff defrocked and degraded them and ordered them to grow their Prussian-cropped hair in conformity with the sumptuary laws of the government officials of the Dewa Zhung.14 The violence in Mongolia, which accompanied the sup- pression of the lamaist church and the installation of the revolutionary government, had also made a profound im- pression on the Dalai Lama’s mind. One year before his death he issued a warning on the imminent ‘red’ danger that might rear its head either from without or within, sweeping away in

1 1 It was the British military expedition that had directly provoked Chinese retali- ation in Kham and the creation of the project of assimilation of the Tibetan plateau. Sir Francis Younghusband, India and Tibet, London, 1910; Parshotam Mehra, The Younghusband Expedition, London, 1968, and Peter Fleming, Bayonets to Lhasa, London, 1961.

1 2 P. Mehra, The North-Eastern Frontier, Vol. II, 1914-1954, Delhi, 1980, pp. xxiii-xxiv.

13 The Assembly, often called the National Assembly (in Tibetan: Tshogs-’du), was formed in 1871, and consisted of the abbots of the three big monasteries of Drepung, Sera and Ganden, and the heads of all government departments. W.D. Shakabpa, op. cit., p. 190. See Ram Rahul, The Government and Politics ofTibet , Delhi, 1969, pp. 31-2, for a description of its functions. ‘The role of the Tsongdu was very important in the determination of all questions of policy.’

14 sDe-pa gZhung: i.e. the Tibetan government.

82 GOVERNMENT AND OPPOSITION

true Cultural Revolutionary fashion monks and monasteries and all the teachings of the Buddha, till nothing would be left but the name. This, his last testament, known as the K ~ c h e m , ' ~ was to have long-term consequences. His words impressed them- selves not only on the pious and superstitious minds of the con- servative majority, but also on the minds of the young pro- gressives, dreaming and conspiring towards a new Tibet.

We have written testimony of one of them at least16 and circumstantial evidence that others too took as a watchword the passage in the Kachem in which the pontiff urges his fellow countrymen to learn from both great neighbours, South and East, better to defend the Land of Snow against these imposing powers.

THE I N T E R R E G N U M

In the two years following the death - perhaps the assassination - of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama in December 1933'' we see the exodus of a small but significant group of individuals, either banished or going into voluntary exile in China or India for the next decade or more. First, Kunphel-la, favourite of the dead pontiff, together with two or more companions (in January 1934); and secondly members of the 'republican party' whose leader, Lungshar, after having succeeded in ousting 'his erst- while rival (Kunphel-la), was himself imprisoned and blinded for high treason very shortly afterwards." Lungshare was the most widely travelled of all Lhasa nobles, having accompanied the first and only group of four noble boys who were sent to Rugby for a modern education. Lungshar spent a year visiting England,

1 s Made public in 1932. See W.D. Shakabpa, op. cit. p. 270. 16 Rabga Pangdatshang, in the Tibetan newspaper, Melong, Kalimpong, 24 December

1936. See translation in Le Mendiant de Z'Amdo, op, cit, Ch. 111. 17 C. Bell, Portrait of the Dalai Lama, London, 1946, p. 388, makes veiled allusions

to this in his detailed account of the last days of the Dalai Lama. See Le Mendiant de Z'Amdo, op. cit, Ch. 111. A new Tibetan publication from Lhasa, Bod kyi rig gnus lo rgyus rgyu cha bdams bsgrigs, Lhasa, 1982, gives two slightly different versions of the last moments of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, one by Lha-klu Tsche-dbang rDo-rje, on his father Lungshar, see pp. 100-1, and another by Brag-gseb Thub-bstan Chos- rgyal, on the Dalai Lama's doctor, see pp. 127-9, in which the state oracle is de- scribed as forcibly administering medicine that was far too strong.

18 See Who's Who in Tibet, 1938, India Office Records, IOR L/P&S/ZO/D220, p. 44.

TIBET: TRANSITION FROM BUDDHISM TO COMMUNISM 83

France and Germany before returning to Lhasa where he was given the post of Minister of Finance. In this capacity he attempted to create a badly needed surplus of money to pay for the equally badly needed improvement in the army. It should be noted that Lungshar is somewhat maligned in British accounts.19 He had lived in England, and seen the wonders of the homeland, and therefore he was expected to be pro-British, but he was not, and try as one would it was difficult to brand him as pro-Chinese. He was, it seems, pro-Tibetan. It is to this unsung category that most of the persons we are to follow belong, in spite of, or rather because of extensive travels and sojourns in other countries.

Lungshar’s career ended in 1934 in what may be called the Tibetan version of the Bastille,2o but Kunphel-la survived. The headstrong favourite of the last years of the Dalai Lama’s life, he was one of several men of humble origin raised to high state by the pontiff. He had been responsible for the introduction of the first motor car, the first cinema projector, the first regiment of a modern Tibetan army. For several years the most powerful man in Tibet (apart from the Dalai Lama), it was he who con- trolled the mint and the army. He maintained good relations with the Khampa frontier troops, not only in terms of supplies, but also in terms of trust. For between the Tibetans of the eastern provinces of Kham and Amdo and the Lhasa nobility, little love was lost.

Kunphel-la was absolved of the murder of the Dalai Lama, but banished in the same year to Kongpo in Southern Tibet. The clergy feared a military take-over and the cabinet ministers feared that they would be subordinated to a new political regime with Kunphel-la as prime minister. Another exile was to join Kunphel-la. This was the ex-duke Changlochen, who had appeared on the scene in 1925 as one of the young British- trained army officers who burst into the Assembly demanding

19 See H.E. Richardson, A Short History of Tibet, New York, 1962, pp. 139-41. Lungshar is condemned as a medieval conspirator.

20 In 1951, the Zhol prison was almost as empty as the Bastille a t the time of the French Revolution. There had been a general amnesty on the occasion of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s enthronement. The prison was also enshrouded in a similar aura of torture and cruelty. See the Tibetan version of Lungshar’s end, by his son, Lha-klu Tshe-dbang rDo-rje, op. cit., pp. 93-109, and Rakra, op. cit., pp. 111-14, who in contrast defends the conditions in the prison compared to others in Asia.

84 GOVERNMENT AND OPPOSITION

military representation. Not long after his degradation he had been sent on service to Chamdo in Kham, and there undoubtedly he came into contact with Rabga and Tobgay Pangdatshang, serving in the frontier army under orders from the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. As member of Lungshar’s Republican Party, Changlochen found himself also banished. He joined Kunphel-la in Kongpo and thence they fled together to Kalimpong in India, in December 1934.

In Kham, the two Pangdatshang brothers heard the news of the death of the Dalai Lama and of Kunphel-la’s arrest. Their immediate reaction was to rise up in revolt and seize the govern- ment arsenal in Chamdo. Following a counter-attack by Tibetan government troops, they both disappeared into China. There Tobgay received some military training from the Guomindang, and Rabga applied himself to the study of political philosophy, particularly to the Three Principles of the People by Sun Yatsen. Also, with the Kuchern of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama in mind, he made prolonged visits to India in order to learn about the ways of the British Empiree2’

The timid conservatism of the interim government between the reigns of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dalai Lamas, coupled with the blind bigotry of the extreme orthodox Gelugpa22 clergy led (or forced?) several of the more open- minded of the monastic community to quit. In 1934, the Indian Buddhologist R5hul SahkFityayan was in Lhasa. He was not only a scholar, but also a member of the Indian Communist Party and founder member of the All India Peasants’ Union (Kisun Sabhu). In Tibet he was in frequent contact with Geshe Sherab Gyatsho, one of the most accomplished and influential Gelugpa scholars of the day, and also with his iconoclastic disciple, Gedun Chompel, who was to accompany R5hul Szrikfityayan to India that summer, into twelve years of voluntary exile. Geshe Sherab himself had been a close associate of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, and no doubt also knew Dorjiev. In July 1934 R5hul wrote in his diary that ‘Geshe Sherab was the first among the Gehgpa hierarchy to welcome the successes of Mao Zedong, and the first to express the wish for a

1 1 Cf. supra no. 16 and infra no. 27. 11 Gelugpa, one of the four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism, and politically the

most powerful, with the Ddai Lama and the Panchen Lama as its foremost leaders.

TIBET: TRANSITION FROM BUDDHISM TO COMMUNISM 85

programme of reforms which would permit a new era in Tibetan history’.23

The sympathy with which Geshe Sherab regarded Mao’s progress in China was no doubt largely influenced by the Chinese Communist Party declarations concerning the ‘national rn inor i t ie~’ ,~~ inspired in turn by official Soviet policy on minorities. Geshe Sherab originated from the extreme north- east of the Tibetan plateau, in Amdo. He had spent his early years in the monastery of Labrang and had seen (im Amdo) and heard of (in Kham), the terrible clashes between Chinese and Tibetans, during the first decades of the century, both at the end of the Manchu dynasty and during the following years.25

The avowed aims expressed both in the Three Principles of the People, and in the Constitution of the Chinese Communist Party, rang sweetly in the ears of those of the eastern Tibetans who were aware of the ambiguous status of their provinces, and who felt themselves to be both abandoned by the Tibetan government and a prey to the hungry warlords of Sichuan and Qinghai. They read in the Jiangxi Constitution the signals of a new age. This ‘Constitution of the Soviet Republic’ called for the equality of nationalities, freedom of religion and recog- nition of

the right to self determination of the national minorities of China, right to complete separation from China, and to the formation of an independent state for each national minority. All Mongolians, Tibetans, Miao, Yao, Koreans and others living in the territory of China shall enjoy the full right to self determination, i e . they may either join the Union of Chinese Soviets or secede from it and form their own state as they may prefer.. . .26

So, in early 1937, Geshe Sherab abandoned (or was banished from) the Land of Snow, accepting a high post in the

23 Rihul SB&+tylyan, M Z G ] & m Y&ri (Autobiography), Vol. 11, the month of June 1934, Ilahabad, Kitab Mahal, 1950.

24 Although at this time China had very little, or no control at all, over many of the regions of the actual national minorities, that they were to claim as belonging to the PRC.

*I See Eric Teichman, Travels of a Consular Officer in Eastern Tibet, Cambridge University Press, 1922, p. 228 note.

26 June Dreyer, China’s Forty Millions, Harvard, 1976, pp. 63-4.

86 GOVERNMENT AND OPPOSITION

Guomindang and an invitation to reside in China.27 There he is said to have translated Sun Yatsen’s Three Principles of the People from Chinese into Tibetan.28

In fact, the Amdowas had been, since the early eighteenth century, on special terms with the Manchu court in Beijing. It took two and a half months of arduous and even dangerous travel to reach Lhasa from the monastery of Kumbum in northern Amdo, whence most of the Tibetan caravans started out. This great geographical distance was accompanied by a psychological and political chasm between the eastern and central Tibetans, exacerbated by the indifference of the Dewa Zhung towards the political status of the eastern provinces. Unity was maintained, as it had been throughout the centuries, since Mongol times, by religious ties.

In China, Geshe Sherab steered a diplomatic course through the ‘heaving red waters’ of the revolution, with such address that he became the most influential and active of all Tibetan lamas residing there. After 1949, he rose through a series of political posts in Qinghai (the Tibetan province of Amdo takes up the major part of the new Chinese province) to become vice- governor of the province (1949-1967), also holding from 1953 to 1967 the post of president of the All China Buddhist Associ- ation, visiting, in this capacity, Sweden, Burma, Ceylon, Nepal and Cambodia. He made frequent broadcasts to his fellow Tibetans on the plateau, urging them to accept the communist regime, all the while maintaining an outspoken defence of the rights and specific needs of the national minorities, especially in education, traditional customs, practices and econom . He died

There were a number of other progressive Tibetan lamas such as Geda of Kanze, and Jamyang Zheba of Labrang, though little

after brutal treatment during the Cultural Revolution. 19

27 H.E. Richardson, A Cultural History of Tibet, Boulder, Colorado, 1980, p. 245. See the Tibetan newspaper, Melong, Kalimpong, 1 January 1951, for an article by Tharchin on Geshe Sherab Gyatsho.

2s See IOR L/P&S/12/24O/Coll.36/39, 1 December 1944. There are doubts, how- ever, as Rabga Pangdatshang also made a translation of the Three Principles of the People into Tibetan.

29 See the various editions of Who’s Who in Republican and Communist China, Shirob Jaltso (or Zhihai). See also the obituary (in Tibetan) in Shes-bya, Dharamsala, June 1981, pp. 25-6. A paper entitled ‘The Long Life of Geshe Sherab Gyatsho’ was given, by the present author, at the Conference of the International Association of Tibetologists, at Munich, July 1985.

TIBET: TRANSITION FROM BUDDHISM TO COMMUNISM 87

is known of their careers at present. Phagpa-Lha of Chambo became and still is a leading (‘honorary’?) figure in the govern- ment of the Autonomous Region of Tibet, and it was Gonkhar Trulku who headed the first revolutionary soviet in Eastern Tibet in 1935. Dungkar Lozang Trinle, Tseten Zhabdrung and other scholars helped in the setting up of Tibetan teaching programmes in the Institutes of National Minorities.

The Mongol lama Geshe Chodrak, a close friend of Gedun Chompel and RZhul Siinkrityayan, was the author of the first modern Tibetan-Tibetan dictionary, He joined the new Chinese Translation Bureau set up in Lhasa in the early 1950s, to work side by side with a number of lay Tibetans already known for their critical attitude towards the ecclesiastical government. The first task was the translation into Tibetan of the classics of Marxist and Maoist-Leninism.

Lacking any theoretical documents, it is difficult to know exactly what was envisaged for the future ‘real’ Tibet, by the new Tibetan intellectuals of the 1930s and 1940s. It is certain that the ideas were multifarious, heterogeneous and no doubt naive in many ways. They included elements drawn from the whole range of contemporary political ideologies: Guomindang republicanism, communism as it was developing in China; British liberalism; Asian nationalism founded on the anti- colonial, anti-imperialist struggles for independence; even militant nazism, as it was understood in south-east Asia at the time.30 Tibet, however, had not suffered andlor benefited from an occupying imperial Western power, as much of the rest of Asia and Africa had. Some central Tibetan families sent their progeny to the British Mission schools on the other side of the Himalayas, but being of noble origin, they identified them- selves, in the main, if not exclusively, with the elite British ruling class in India. A few well-off Khampa and Amdowa families, on the other hand, sent their sons and more rarely their daughters to China to study in the Guomindang schools and military and political academies. Of these several individuals developed into political activists. Described as ‘naive’, ‘oppor- tunist’, ‘crafty’, the extent of their commitment and the

30 Abridged, ‘whitewashed’ versions o f Mein Kampf were circulating in India and South-East Asia at the time. See Hitler’s Mein Kampf, introduction by D.C. Watt, translation by R. Manheim, London, 1969, pp. xv, xvii.

88 GOVERNMENT A N D OPPOSITION

long-term effort they put in to find a solution, first for the eastern provinces and ultimately for the whole Tibetan plateau is almost unknown. It is significant that the first attested attempt to establish an autonomous or independent state of Kham in between China and Central Tibet was made in 1932, one year after the ‘Soviet Constitution of Jiangxi’. Li Tieh Tseng described the abortive event in the following terms:

Supported by the popular masses, Ke-sang Ce-ren, Commissar of Xikang affairs for the Guomindang, easily disarmed the garrison forces of the warlord of Sichuan, Liu Wenhui, who had invaded Batang, and in March 1932 declared the foundation of an autonomous regime.31

The ‘regime’ was rapidly dismantled, following which its author disappeared equally rapidly from the scene.

E A R L Y TIBETAN COMMUNISTS

The early Tibetan communists formed the most distinctive group among the emerging new Tibetan progressives, in that the key figures (with the exception of Phuntshog Wangyal) never sought or had the opportunity to go beyond the frontiers of the Land of Snow or of China, and thus remained within the large historical current of the Chinese Communist Party.

T.N. Takla has given us a very brief outline of the careers of several of them.32 We also find a number included in the various versions of the Who’s Who of Republican and Communist China. The first were those who joined, were ‘enlisted’ or ‘abducted’ into the Red Army when the Long March traversed Kham and Amdo in 1935. Perhaps the youngest was Sangye Yeshe (or Tian Bao). He was appointed director of the Youth Department of the first Tibetan Soviet government ‘Popa’i Dewa’, set up in Kanze in 1935, under the leadership of Gongkhar Trulku, following negotiations with the Chinese revolutionaries. These negotiations had themselves followed serious hostilities between the Tibetans and Chinese, as the fleeing Long Marchers entered Tibetan territory. According to Takla this Soviet government ‘died a quick and natural death’ after the departure of the Chinese troops, as it had no base in

31 Li Tieh Tseng, Tibet. Today and Yesterday, New York, 1960, p. 61. 32 T.N. Takla, ‘Notes on some early Tibetan communists’ in Tibetan Review, June-

July 1969, pp. 7-9, 19.

TIBET: TRANSITION FROM BUDDHISM TO COMMUNISM 89

the Tibetan highlands. However, according to another source,33 ‘they left Tibetan converts behind, many of whom were later given posts in a Tibetan autonomous zhou established in Sichuan in November 1950’. After a long and illustrious career, Sangye Yeshe was elected Chairman of the People’s Govern- ment of the Tibet Autonomous Region in 1979. Two other Tibetans who accompanied Mao to Yenan were to distinguish themselves: Lo Tenga of Kanze also had a brilliant career and eventually became Political Commissar in Manchuria, while Tashi Wangchuk of Nyarong became member of the Liberation Committee for the North-West - Qinghai, Gansu and Xinjiang. He was later elected member of the Nationalities Affairs Com- mittee and in 1950, Chairman of the Qinghai Minorities Institute. Both of these two died under tragic circumstance^.^^

The question as to whether these Tibetans, even those in the highest positions, such as the Panchen Rinpoche and Ngapho Ngawang Jigme, ever exercised any real power of decision is a very debatable point. Since his appointment in 1979, Sangye Yeshe is the first non-Han, Tibetan Chairman of the Tibetan Autonomous Region since its foundation. Other Tibetans who joined the CCP in the late 1930s and early 1940s were to experience this dilemma. One fairly well-known case is that of Phuntshok Wangyal. Originating in Batang, in Kham, he and his companion Ngawang Kelsang studied in the Guomindang Political Academy in Chongqing. The two men soon became, in secret, CCP members. Not long after, they found themselves sent down for ‘indiscipline’. They were already disillusioned with the Guomindang system, as they saw the unequal treat- ment meted out to Tibetans once they graduated and rose in the ranks of the Chinese hierarchy. In spite of hlgh-sounding titles, all real power was in the hands of the Han Chinese. The theoretical equality of the nationalities did not work out in practice. Making their way to Kham, the two companions fought, with the Tibetans, against the troops of Chiang Kaishek, who were massing along the eastern marches of the plateau in 1942 and 1943, and making absolutist demands concerning rights of movement, establishment of airports and roads on the

33 A Biographic Dictionary of Chinese Communism 1921-1965, Volume 2, Harvard

34 See T.N. Takla, op. cit., p. 8. University Press, 1971, p. 748.

90 GOVERNMENT A N D OPPOSITION

Tibetan plateau by the Chine~e.~’ Convinced communists, though much impressed with the potential might of China, Phuntshok Wangyal and Ngawang Kelsang formed a provisional revolutionary eastern Tibetan government in T ~ a k u r , ~ ~ then made their way to Kalimpong, where they presented proposals for a future government of Tibet, and the reform of the present ecclesiastical system, requesting support and aid from the Bri t i~h.~’ This request was studiously ignored. The same pro- posals were later presented to Surkhang, the most influential minister in the Tibetan government, but again to no avail.

In Kalimpong, Phuntsok Wangyal made contact with Rabga Pangdatshang and his circle. Their political affiliations were widely divergent, but both had strong sympathies towards China, and both were searching for a new solution for Tibet. Rabga’s villa had become a centre for political discussion.

Earlier in 1939, Rabga, Kunphel-la and Changlochen had prepared a ‘Concise Agreement’ for the formation of a political party, following which Rabga left for China, presumably to seek financial and moral support for its organization. The first appli- cation forms that he ordered in February 1946 had placed the party in a position of complete subordination t o the Guomindang and to the will of Chiang Kaishek. But in the following two months Rabga Pangdatshang obviously decided upon a change of tactic. Perhaps he met with a categoric refusal on the part of his fellow Tibetans? Or perhaps he realised the full force of the racist assimilation policy of the new version of Chiang Kaishek’s book, Destiny of China? In any case, in the revised version of the application forms, the Tibetan Progressist Party, though still vaguely affiliated, is to all intents and purposes an independent political party. The triple name on the insignia gives an indi- cation of this separate identity and also of its rather ambiguous and tentative political stand:

In Tibetan: Nub-Bod Zegs-bcod skyid-sdug: West (sic!)

In Chinese: Xizang Gemingdang: Tibet Revolutionary Party. In English: Tibetan Progressist Party.

Tibetan (i.e. Xizang) Improvement Party.

35 India Office Records, L/P&S/12/4210 Coll. 3 6 / 3 9 , 2 3 October 1943. 36 Oral information. 37 India Office Records, op. cit., 1 0 November 1943.

TIBET: TRANSITION FROM BUDDHISM TO COMMUNISM 9 1

It seems that in the Chinese version, by using the word geming - revolution, Rabga Pangdatshang subtly but defiantly distinguishes his party from the Republican Guomin-dang. Whereas in the Tibetan version, by using the softer legs-bcod - ‘improvement’, he seeks not to alarm a very naive and unsophisticated population, wary of, if not totally unaware of, the import of any of the modern political ideologies. In the English version, ‘progressist’ suggests perhaps a similar guarding against inflammatory terms that might have alarmed the British.

In spite of these precautions, the British took immediate action. With Mr Lambert, the top CID man in India, in charge of interrogations, scores of Tibetans residing in the Kalimpong area were questioned over a period of two or three months. The result was the break-up of the Tibetan Progressist Party and the extradition of Rabga Pangdatshang to China, since he possessed an official Guomindang passport. Other members associated with the party were dispersed. Meanwhile in Lhasa the Tibetan government was informed by degrees of the existence of the party, outside the frontiers of Tibet, and of the fact that one of its sympathizers was present in Lhasa. This heavy hinting resulted in the arrest of Gedun Chompel who had returned to Tibet after twelve years of exile, at the beginning of 1946, before the application forms had even been ordered. He was accused of everything from communism to forging bank-notes and after a gruelling period of interrogation behind closed doors, was whipped (50 lashes) and thrown into jail, having become a scapegoat for the whole affair and ultimately a martyr to the nascent cause of Tibetan n a t i o n a l i ~ m . ~ ~ A detailed analysis of the rise and fall of the TPP based on British govern- ment papers and on interviews with a number of party members is to be published shortly.39

Meanwhile, Phuntshok Wangyal and Ngawang Kelsang had also settled down in Lhasa, in the house of the elder brother of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. Phuntshog Wangyal became music teacher in the Guomindang school and at the same time formed his own clandestine party: ‘The Secret Society for Tibetans Under Oath’.40

38 See his life story, which forms the second part of Le Mendiant de l’Amdo, op.

39 Le Mendiant de Z’Amdo, op. cit., Ch. 111. 40 See T.N. Takla, op. cit., p. 9.

cit.

92 GOVERNMENT A N D OPPOSITION

According to Takla, it is doubtful whether Phuntsok Wangyal and his party had any effective contacts in eastern Tibet. How- ever, neither does Takla mention either of the two reform projects presented to the Tibetan government by Phuntsok Wangyal in 1943 and 1949. In whichever source we look, there are gaping holes. In the late 1940s, it seems most unlikely that ‘The Secret Society for Tibetans Under Oath’ was isolated and limited to Lhasa. The eastern Tibetans had tried again and again to shake the Lhasa officials out of their torpor. In 1949 this is what actually happened, but not with the desired result.

Instead of rising up with their fellow Tibetans from the East as one nation, the clerical and noble elites of Lhasa rose with uncommon alacrity, cut off what little there was in the way of telecommunications with the outside world for two weeks, and under a smoke screen evicted Phuntshok Wangyal and all the members of his party who had signed the reform project, together with the entire Chinese community of Lhasa. With musical fanfares they were escorted out of Lhasa and directed towards the Indian frontier and then to China.

The reaction of the Tibetan government was hardly surprising. they had lately been moved to defend actively the independent position of the government so painstakingly formed by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. The first International Trade Mission had recently returned from a trip around the world, on Tibetan passport^.^' The ex-regent Reting had recently expired after an abortive attempted return to power - reputedly with Chinese backing. In Lhasa itself, Phuntsok Wangyal had presented yet another project for the radical reform of Tibetan society (without mentioning the word ‘communist’) and it was all written in Chinese. Rabga Pangdatshang was still at large, and Gedun Chompel barely out of prison, though in very poor physical condition. The heralds of the new age - that ‘night- mare’ prophesied so vividly by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama - were crossing the thresholds of the houses of the Lhasa nobility, and creeping, in monks’ robes, into the mona~teries.~’

At this same moment, in Amdo, Apha Alok and Geshe

41 India Office Records L/p&S/12/4230 Coll. 36/53, Trade Mission. See also W.D. Shakabpa, op. cit., pp. 294-97.

42 Rakra, op. cit., p. 169, gives a sinister and romantic account of a meeting be- tween Gedun Chompel and a communist party agitator in monk’s robes, in Lhasa, 1950.

T I B E T : T R A N S I T I O N F R O M BUDDHISM TO COMMUNISM 9 3

Sherab Gyatsho are said to have joined in, in the late 1940s, with a group of Khampas in an attempt to found a new com- bined government of the whole of eastern Tibet. Their aim was to coerce or ultimately force the Central Tibetans to join in with them to repel what they considered an inevitable Chinese invasion. Having united the whole plateau, they would create a new government and a new social system.43

However, Mao Zedong was himself on the threshold of victory. Very rapidly the eastern Tibetans received an ultimatum: either be crushed or join hands with the new China. Their own projected revolutionary government was declared by the Chinese to be one with that of the PRC and broadcasts were made from the periphery areas of Kham and Amdo, from Xining, Lanzhou, Xian and Chengdu, calling the Dewa Zhung to join in the great proletarian revolution.

GEDUN CHOMPEL

In the midst of all this turmoil, a key figure was drinking him- self to death, watching the hopelessly disunited Tibetans - those few who were aware of any impeding cataclysm - tugging vainly in several directions at once. Gedun Chompel (1905- 1951) was a learned philosopher and scholar, one of the most brilliant dialecticians of his time. He was also a ‘mad’ non- conformist, nurtured until the age of thirty in that rich and conflictual Nyingmapa-Gelugpa* tradition. His own discovery of ancient Tibetan history had led him to question the entire edifice of Buddhist scholastic tradition, and when Riihul Sahkfityayan arrived in Lhasa in 1934, he did not hesitate to accept the invitation to accompany the Indian scholar and political activist on his return journey to India. At first passion- ately involved in his search for the origins of Tibetan writing, and the historical vestiges of Buddhism, Gedun Chompel was also introduced by RZhul into the world of pre-independence India: to Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and to Bose, to the renaissance of classical Indian values and teachings, to the bitter and multifarious anti-British struggles. He was to spend twelve impecunious years travelling from Darjeeling to Sri Lanka, from

43 Le Mendiant de l’Amdo, op. cit., Ch. 111. 44 Nyingmapa, another of the four schools of Tibetan Buddhism, see note 22.

94 GOVERNMENT AND OPPOSITION

Ajanta to Swiit, studying Sanskrit and Pdi, the lives of the bhikkhus of the Theravsdin tradition, translating the great Indian classics into Tibetan, reading widely in English, and assimilating modern western political ideologies. He read Kant, Marx, Hitler and Spinoza, Sufi poetry, on Judaism and Zen, on Shintoism, on science and technology, on the discovery of the continents and the expansion of the West. He became the first modern Tibetan cartographer, and the first Tibetan scholar to read the Dunhuang manuscript^.^^ In 1938, only four years after his arrival in India, he was described as a fearless man, totally dedicated to the revolution, and to the radical transfor- mation of his society but feeling somewhat helpless and alone in the face of the overwhelming weight of the church and the bigoted clergy.46

Associated at one time or another, especially in the 1940s, with almost all the persons mentioned here - (with the exception of the Tibetan communists educated and remaining in China) - he became, when he returned to Lhasa in early 1946, a source of nationalist inspiration and a focal point for information concerning the modern world and political develop- ments. The two actually never met, but if Phuntshok Wangyal conceived of a new pan-Tibetanism, opting to remain within the fold of the newly emerging China, inspired by the theoretical freedom promised in the Soviet constitution, Gedun Chompel was in the process of developing another type of pan-Tibetanism, with a view to uniting the whole area of Tibetan civilization: from Ladakh to the Koko Nor, from Tsaidam to Monyul, into a new political state. More than any of his contemporaries, he appears as an idealist, permeated to the marrow by his own culture, and at the same time critically aware of it in the wider context of Asia, and the world. Naive he may have been, but in this he was scarcely alone.

In the arch-traditionalist society of Lhasa, the seeming eccen- tricities of his thought and behaviour were, for many, much more readily acceptable, thanks to his reputation and relative

4s The earliest written Tibetan manuscripts that are known (8th-10th century). Two important collections are in the British Library and the BibliothZque Nationale, Paris.

46 Ph& Moukherji, ‘Rahulji kE sith Tibbat kE abhiyin mem’, in Sarasuati (Hindi journal), July 1964, 64.

TIBET: TRANSITION FROM BUDDHISM TO COMMUNISM 95

sanctity as a ‘mad’ mah%iddha4’ and former renowned dialectician. In comparison, the outright projects of political and social transformation proposed by Phuntshok Wangyal, or the somewhat ambiguous stance of Rabga Pangdatshang’s ‘revolutionary-cum-progressive party’, both with rather strong Chinese connections, were open to immediate hostility and rejection.

And yet the tragic death of Gedun Chompel, after he had been released from prison in 1949, and installed, as government historiographer (under house arrest),48 in the Jhokhang - in the holy of holies of Tibetan Buddhism - illustrates poignantly the tragic dilemma of the society, reflected in the exceptional individual. The conflict between two states of mind: on the one hand, that of powerful religious inspiration, guiding the society as a whole, and on the other, the pregnant force of economic, political and scientific awakening. These were brought into abrupt and hazardous confrontation.

The future careers of those who surrounded Gedun Chompel, both those who went into exile in 195949 and those who chose to stay and collaborate with the Chinese regime in the hope of creating a new society,” illustrate the limitations, the uneven- ness and the violence of the attempted integration of Tibet into the world of the twentieth century.

47 In Tibetan grub-tho& or grub-chen, considered as enlightened beings, beyond the entraves of the cycle of existence (samsara), and therefore of all norms of conven- tional behaviour.

48 He was in fact under ‘city arrest’, his movements being limited to the periphery of Lhasa.

49 For example, Rabga Pangdatshang, Abdul Wahid, Lachung Apho, Chichak, Rakra Rinpoche.

so For example, Geshe Sherab, Horkhang Sonam Pelbar, Geshe Chodrak, Phuntshok Wangyal.