The Presence of Cyprus in English Literature: From Shakespeare to Durrell and Du Maurier

Transcript of The Presence of Cyprus in English Literature: From Shakespeare to Durrell and Du Maurier

THE PRESENCE OF CYPRUS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE: FROM SHAKESPEARE TO DURRELL

AND DU MAURIER

Demetra Demetriou

Cyprus has been a source of inspiration for great personalities in English literature,from the foremost playwright William Shakespeare to prolific novelists of the20th century, such as Lawrence Durrell and Daphne Du Maurier. Shakespeare, beingin the royal repertory, in favor of Elizabeth I and James I of England, and Durrell,having served in the colonial government of Cyprus, have vividly incorporated,each one in his work, moments from the historical adventures of Cyprus, whichtestify to the geopolitical interest of England in the island. For Du MaurierCyprus has been, on the other hand, a fertile land of literary production.

a. Othello: the Cypriot tragedy of Shakespeare

Love, jealousy, envy; uncontrollable passions, hamartia (sin) and pathos (passion):these are the first words that come to mind when someone refers to Othello. Theplay, written around 1603-4, belongs to the best creative period of Shakespeare andits space-time context is set initially in Venice and later on in 16th century Cyprus.

The historical sources connect Othello to the town of Famagusta, even though inthe play, there is just a vague reference made to some “port in Cyprus” (II,1) and to a“tower” (II,3), without citing any individual location. The medieval fortress of thetown is still called “Tower of Othello”. The Moorish Negro hero, Othello, who isappointed commander of Cyprus by Venice, has been traditionally linked to the Vene-tian officer Cristoforo Moro, who served as governor of Cyprus during 1505-1507.1

Even though Shakespeare uses as a source Cinthio Giraldi’s narrative “Ilmoro di Venezia”, which also takes place in Cyprus, he adds in his own version theOttoman threat, and this is not accidental. Venice lost Cyprus to the Ottomans in1571, and the threat of further Ottoman conquests was very clear. The British play-wright received information about these facts from the book of Richard Knolles

-830-

1 There is no proof that connects Cristoforo Moro with the case of the play; however, heseems to be identified with Othello from his surname, which means ‘black’ as well as ‘moor’.

Pag. 653-856 NEW 4-11:Layout 1 11/5/12 4:28 PM Page 830

General Historie of the Turkes (1603).2 This book, friendly towards Christian Venice,includes many pages on the Venetian-Ottoman differences over Cyprus and ithas been argued that Shakespeare used many of these elements in his play.3 Fur-thermore, the representation of Muslim Ottomans in the Shakespearean play is con-nected with the interest of the King of England James I for the control of the Ottomanpursuits in the Mediterranean. The defeat of the Ottoman navy at the Battle of Lep-anto (1571), the main reaction of the Christian states to the occupation of Cyprus,greatly pleased King James, who celebrated characteristically the victory of theChristian forces with his long poem “Lepanto”.4

Beyond the political objectives of Jacobean England, the strained atmosphereand the violence that reigns in threatened Cyprus, the conflict between East andWest, which frames up the difference of “the Moor” and Desdemona, give to theplay further tragic resonances. In the island of Aphrodite, a bloodstained end isreserved for the two lovers, since Othello decides to give justice and reach the finalcatharsis there:

OTHELLO [to DESDEMONA] I kissed thee ere I killed thee. No way but this:Killing myself, to die upon a kiss.5 [V, 2]

b. Lawrence Durrell in bitter lemons’ landIn an island of bitter lemons[…]Better leave the rest unsaid,Let the old sea-nurses keepTheir memorials of sleepAnd the Greek sea’s curly headKeep its calms like tears unshed6

-831-

THE PRESENCE OF CYPRUS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE: FROM SHAKESPEARE TO DURRELL AND DU MAURIER

2 Virginia Mason Vaughan, “Supersubtle Venetians: Richard Knolles and the geopolitics ofShakespeare’s Othello”, in Laura Tosi/Shaul Bassi (eds), Visions of Venice in Shakespeare,Farnham/Burlington 2011, p. 21.3 Ibid., p. 26.4 See extract of the poem with the title “Stanzas from the Lepanto”, in Edward Farr (ed.), SelectPoetry, chiefly sacred of the Reign of King James the First, Cambridge 1847, p. 5-7.5 William Shakespeare, Othello, in S. Greenblatt (ed.), The Norton Shakespeare. Based on theOxford edition, New York/London 1997, p. 2172.6 Lawrence Durrell, Bitter Lemons, New York 1957, p. 252. [The poem “Βitter Lemons”, accord-ing to a note of the writer, was published for the first time in Truth, 1st March 1957. In BitterLemons it is quoted in the end of the book].

Pag. 653-856 NEW 4-11:Layout 1 11/5/12 4:28 PM Page 831

Lawrence Durrell’s love for Greece and his emotional connection with theMediterranean island space have been painted with bright colours in his work. Witha good knowledge of the Greek language, he lived successively on the islands ofCorfu, Rhodes and later in Cyprus, where he stayed from 26th January 1953 until26th August 1956.7 He bought a small house in Bellapais, near Kyrenia and becamefriends with the Cypriot poet and later diplomat Nicos Kranidiotis, the painter PaulGeorgiou and other Cypriot scholars and artists.8 He initially worked as an Englishlanguage teacher at the Pancyprian Gymnasium of Nicosia. From the summer of1954 he worked as the Director of the Public Information Office,9 and later on asthe Head of the Department of Public Relations of the Colonial Government ofCyprus,10 but also as the editor of the magazine Cyprus Review,11 following theBritish colonial policy.

Cyprus was for Durrell a place of inspiration but also of literary production.In his correspondence with Henry Miller, he mentioned that already from March1953 he had begun writing his novel Justine,12 though he often complained aboutthe workload, which did not allow him enough time to work extensively on his ownwriting. With Justine he wished to outperform the fame of his own The Black Book,which had caused many and varied reactions in Britain. He mentions that hecompleted Justine in the summer of 1956,13 just before leaving Cyprus. Justine waspublished in 1957 and was the first of the four parts of The Alexandria Quartet,which gave him international fame as a writer. After Justine and after the start ofthe EOKA struggle in Cyprus (1955-1959), Durrell admitted to Miller his inten-tion to write a book on his experiences in Cyprus.14 These thoughts led to the

-832-

LINKED BY HISTORY - UNITED BY CHOICE: CYPRUS AND ITS EUROPEAN UNION PARTNERS

7 For the exact dates of Durrell’s arrival and departure from Cyprus see Ian S. Macniven, LawrenceDurrell. A biography, London 1998, p. 385 and 442.8 Ibid., p. 397.9 Ελευθερία (Eleftheria), Nicosia 18 August 1954.10 Macniven, op. cit., p. 427.11 Ibid., p. 418.12 Lawrence Durrel. Henry Miller. Une corespondance privée, trans. B. Willerval, Paris 1963,p. 356.13 Ibid., p. 366.14 Ibid., p. 367-368.

Pag. 653-856 NEW 4-11:Layout 1 11/5/12 4:28 PM Page 832

writing of Bitter Lemons, which was published in 1957 and became immediatelya best-seller, winning in the same year the Duff Cooper prize. The AlexandriaQuartet and Bitter Lemons were lucky to have as their translator in Greek thedistinguished Cypriot intellectual, Aimilios Hourmouzios.

One can easily discern both the autobiographical and the political15 character of

Bitter Lemons, which was born in the historical-political conditions of Cyprus, con-

temporary to the author. Even though the book reflects both Durrell’s personal

views and the positions of the British colonial government,16 which did not agree

with the aims of EOKA’s struggle, it constitutes an important literary testament,

which reconstructs the tumult of this critical period, through the eyes, and the charm-

ing narration, of one of the major British writers of the 20th century. According to

Durrell, it is “a somewhat impressionistic study of the moods and atmosphere of

Cyprus during the troubled years 1953-6”.17

Bitter Lemons afterwards generated a literary dialogue with the Closed Doors18

by the celebrated Cypriot poet and novelist Costas Montis, but also with the nov-

el The Age of Bronze19 of the Greek writer and diplomat Rodis Roufos; both

works act as an “answer”20 to Bitter Lemons, having as their thematic centre the

anti-colonial struggle of the Cypriots in 1955-59. Years later Durrell reconsid-

ered his views,21 although he always looked at British policy with a critical eye.

In 1964 he stated characteristically for Cyprus in the Greek newspaper Thessa-

-833-

THE PRESENCE OF CYPRUS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE: FROM SHAKESPEARE TO DURRELL AND DU MAURIER

15 Even though Durrell refuses the political character of the book in the preface of BitterLemons, the book is not deficient in political comments. See Richard Pine, Lawrence Durrell:The Mindscape, London 1994, p. 252-256.16 For the colonial discourse of Durrell in Bitter Lemons see Petra Tournay, “ColonialEncounters: Lawrence Durrell’s Bitter Lemons of Cyprus”, in Anna Lillios (ed.), LawrenceDurrell and the Greek World, Cranbury 2004, p. 158-168.17 Durrell, op. cit., p. 9.18 Κώστας Μόντης, Κλειστές πόρτες (Closed Doors), Nicosia 1964.19 Rodis Roufos, The Age of Bronze, London/Melbourne 1960.20 Costas Montis introduces Closed Doors in the frontispiece of the collection as “An answerto Durrell’s Bitter Lemons”.21 Cf. Durrell’s letter to the Times, an extract of which was republished in the Cypriot news-paper Ελευθερία (Eleftheria), Nicosia 23 May 1964.

Pag. 653-856 NEW 4-11:Layout 1 11/5/12 4:28 PM Page 833

loniki: “It [Cyprus] is a tragic island and I suffer for its drama more than anyone

else. I hope […] [this] is the last round of the efforts of the Cypriot people for its

freedom.”22

The Cypriot period of Durrell was accompanied by strong emotional changes:

the deterioration of his wife’s mental health, the requirements and the responsibil-

ity to raise his daughter Sappho on his own, the problems in his marriage that

came later. Added to these were financial difficulties, the obstacles he encountered

in his writing, the clash between the Greek and the British in Cyprus, “the unfold-

ing of the Cyprus tragedy”,23 which he lived “both from the village tavern and

from the Government House.”24 This last aspect of his life in Cyprus cost him the

loss of many friendships, including that of the Greek Nobel Prize Laureate George

Seferis. The two had met during Seferis’ visits to Cyprus in 1953 and 1954, but the

latter was disappointed by the behaviour of his friend. In his diaries, and even in

the poem “In the Kyrenia district”,25 Seferis paints a dark picture of Durrell. Even

though Durrell’s stay on the island was relatively long and creative, it probably left

a bitter lemon flavour in his memories as well as in his work.

c. “The nightingales won’t let you sleep in Platres”

Seferis’ well-known verse about the nightingale’s characteristic song from his

famous poem “Helen”,26 the anaphora of which is associated with intense poetic

vigilance, was written in Platres, a small village up in the Troodos Mountains.

Platres was also host to another important literary figure back in the late 30’s, the

English novelist and playwright Daphne Du Maurier, who was also inspired by the

Cypriot mountainous landscape.

Du Maurier, was born in London in 1907 and died in 1989. She is mostly known

-834-

LINKED BY HISTORY - UNITED BY CHOICE: CYPRUS AND ITS EUROPEAN UNION PARTNERS

22 Θεσσαλονίκη (Thessaloniki), Salonica 10 July 1964.23 Durrell, op. cit., p. 9.24 Ibid.25 George Seferis, “In the Kyrenia district”, Logbook III, in Collected Poems. 1924-1955, trans.E. Keeley/ Ph. Sherrard, London 1969, p. 463, 465, 467, 469.26 Seferis, “Helen”, ibid., p. 349, 351, 353, 355.

Pag. 653-856 NEW 4-11:Layout 1 11/5/12 4:28 PM Page 834

for her novels, which gave her international fame. She visited Cyprus twice, in 1936

and 1937,27 and particularly Platres, one of the main hill-resorts of Cyprus since

colonial days. She stayed at the Forest Park Hotel, along with her daughter and hus-

band, an army officer, at the time posted in Egypt. Her biographer Margaret Forster

mentions that Du Maurier arranged a holiday in Cyprus in mid-September 1936

and returned to Alexandria at the end of the month;28 nevertheless, Cyprus Mail,an English language newspaper published in Cyprus, informed its readers about

Du Maurier’s visit on the 5th September 1936, a fact that implies she was already

in Cyprus since the beginning of the month. The newspaper also pointed out that

“[Du Maurier] is completing now her new book during her stay in Cyprus”,29 which

meant that Du Maurier had finished writing the chronicle of her family The DuMauriers (1937) while on the island. Concerning the length of her stay, accord-

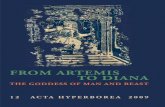

ing to her own note in the book of signatures of the Forest Park Hotel, that one

can see even today, she and her husband “spent in Cyprus four and a half happy

peaceful weeks”.30

Du Maurier’s Cypriot friend and important intellectual figure of Larnaca,Theodora Pierides, whose cottage lies near the Forest Park, confirms the fact thatit was in Platres that Du Maurier completed the writing of The Du Mauriers, andthe place where she wrote most of her novel Rebecca (1938), which is generallyregarded as her masterpiece.31 The two women enjoyed daily their afternoon tea inTheodora’s garden surrounded by lavenders, while they were discussing how thewriting of Rebecca was coming along: “In order to get inspired and write Rebec-ca, Daphne firstly had to go from the “Park” at home and take a deep breath oflavender”.32

Professors Alistair and Gina Wisker write characteristically concerningRebecca’s setting: “The Forest Park Hotel uses the different levels of Platres with

-835-

THE PRESENCE OF CYPRUS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE: FROM SHAKESPEARE TO DURRELL AND DU MAURIER

27 Δημήτρης Πιερίδης, Η ζωή με χιούμορ (Life with a sense of humour), Athens 2004, p. 41.28 Margaret Forster, Daphne du Maurier, London 1994, p. 127-128. 29 Cyprus Mail, Nicosia 5 September 1936.30 The Forest Park Hotel Archive.31 See Theodora Pierides’ memoirs, recorded by her son, Dimitris Pierides, in his book Η ζωήμε χιούμορ, op. cit., p. 41. 32 Ibid., p. 42.

Pag. 653-856 NEW 4-11:Layout 1 11/5/12 4:28 PM Page 835

imagination. It is itself a building which seems to hunt the pages of Du Maurier’sfictions and it is said to have inspired the setting for the filmic version of Rebecca”.33

Indeed, the wooded Manderley and its “triumphal” nature, which is described fromthe very beginning of the book, resembles to the landscape one can enjoy fromthe rooms of the above-mentioned hotel. In Rebecca however, nature is associat-ed with the Gothic setting opening the novel, an essential element which is meantto imply a story shrouded in darkness and mystery, illustrating at the same timecertain elements of character: “The woods, always a menace even in the past, hadtriumphed in the end. They crowded, dark and uncontrolled, to the borders of thedrive”.34 Du Maurier also mentions in a letter of hers to Pierides in October 1937,that Cyprus’ idyllic environment and dazzling light were not really helping theprogress of the novel: “It is because I had forced myself to see everything around…ina Gothic style, and this because of Rebecca”.35

Du Maurier herself adapted Rebecca as a stage play in 1939, which was a suc-cess in London in 1940. The novel has also been adapted to the cinema, as othergreat works of the author, by the well known English director Alfred Hitchcockin 1940, and won a best-cinematography36 and best-picture37 Academy Award, whileit was also nominated for another 9 Oscar awards. It inspired additional booksand writers, such as Barbara Cartland, Angela Carter, Fay Weldon and EmmaTennant.38

Its anonymous narrator, haunted by Rebecca’s name and presence, strugglesto find her own identity, through a world of lingering memories and terror. EvenDu Maurier herself would become “inhabited” by Rebecca, as she explains inher letter to Theodora in October 1937: “Rebecca is still haunting me, I am seri-

-836-

LINKED BY HISTORY - UNITED BY CHOICE: CYPRUS AND ITS EUROPEAN UNION PARTNERS

33 Alistair and Gina Wisker, “Daphne du Maurier at the Forest Park Hotel”, in The ForestPark Hotel Archive, Platres 2011, p. 1.34 Daphne Du Maurier, Rebecca, London 1961 (1st edn 1938), p. 1.35 Πιερίδης, op. cit., p. 43. [Pierides publishes Du Maurier’s letter to his mother translated intoGreek. Citations in this article are therefore translated from its Greek version].36 Νέος Κυπριακός Φύλαξ (Neos Kypriakos Fylax), Nicosia 19 January 1941.37 Kristin Thompson/David Bordwell, Film History. An Introduction, New York 22003 (1st edn1993), p. 228.38 Wisker, op. cit., p. 2.

Pag. 653-856 NEW 4-11:Layout 1 11/5/12 4:28 PM Page 836

ously thinking of vanishing her but it is still impossible. You can only execute theliving. Not the ghosts! Know that they constantly live among us. Don’t be fright-ened if you ever meet them. They won’t harm you. Whatever harm they did, wasdone while living”.39

From the Renaissance to the 20th century, Shakespeare, Durrell and Du Mau-rier’s works are interlaced either with the progress of history in the Mediterraneanarea, or with Cyprus’ people and nature, reflecting the cultural bonds which con-nect Cyprus with the British Isles and contributing to the pages of universal lit-erary heritage.

-837-

THE PRESENCE OF CYPRUS IN ENGLISH LITERATURE: FROM SHAKESPEARE TO DURRELL AND DU MAURIER

39 Πιερίδης, op. cit., p. 43.

Pag. 653-856 NEW 4-11:Layout 1 11/5/12 4:28 PM Page 837

-838-

LINKED BY HISTORY - UNITED BY CHOICE: CYPRUS AND ITS EUROPEAN UNION PARTNERS

The book of signatures of the Forest Park Hotel testifies today to the visitof the English novelist Daphne Du Maurier in Cyprus in 1936. It is in thevillage of Platres that Du Maurier completed the writing of her book TheDu Mauriers (1937) and wrote much of her masterpiece Rebecca (1938)during her second visit to Cyprus in 1937.

Photo: The Forest Park Hotel Archive.

Pag. 653-856 NEW 4-11:Layout 1 11/5/12 4:28 PM Page 838