The Potential of Digital Technologies to Support Literacy Instruction Relevant to the Common Core...

Transcript of The Potential of Digital Technologies to Support Literacy Instruction Relevant to the Common Core...

147

FEATURE ARTICLE

Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 58(2) October 2014 doi: 10.1002/jaal.335 © 2014 International Reading Association (pp. 147–156)

The Potential of Digital Technologies to Support Literacy Instruction Relevant to the Common Core State Standards

Amy C. Hutchison & Jamie Colwell

Digital tools have the potential to transform instruction and promote literacies outlined in the Common Core State Standards. Empirical research is examined to illustrate this potential in grades 6–12 instruction.

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) place a significant emphasis on the use of digital technology to promote

domain specific literacy in grades 6–12 learning and instruction. Additionally, to improve adolescents’ col-lege and career readiness, the national standards em-phasize what literacy research has indicated for years: evolving modes of reading, writing, and communi-cating require a reconsideration of literacy integra-tion in content area classroom contexts (Coleman, 2011 ). The Common Core standards also include the use of digital tech-nology in middle and high school education (National Governor ’ s Association & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010 ). Thus, now more than ever, teachers have to con-sider how digital tools may be effectively uti-lized in their content

curricula to build literacy skills among adolescents. Further, adolescents are avid consumers of digital technology in their everyday lives (Madden, Lenhart, Duggan, Cortesi, & Gasser, 2013 ), and research sug-gests that more concerted efforts are needed to con-nect students’ out-of-school literacy practices to their in-school literacy practices (Hinchman, Alvermann, Boyd, Brozo, & Vacca, 2003/2004 ; Hutchison & Henry, 2010 ) to bridge traditional and new literacies (Moje, 2009 ).

The research base in this area is new, but rapidly emerging. Reports of research on the use of digital technology in literacy have quickly grown over the previous decade, and researchers, using empirical evi-dence, have offered multiple implications and sugges-tions for integrating digital tools to support literacy in middle and high school classrooms. These suggestions are ultimately useful, but the rapid pace at which digi-tal technology has emerged has created a somewhat overwhelming repository of resources from which teachers and teacher educators can draw insight into promoting literacy with digital tools. Thus, the pur-pose of this article is two-fold: First, we wish to draw attention to the ways that the use of digital technology

Amy C. Hutchison is an assistant professor of literacy at Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa, USA; e-mail [email protected] .

Jamie Colwell is an assistant professor of literacy at Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia, USA; e-mail [email protected]. .

Authors (left to right)

148

JOU

RN

AL

OF

AD

OLE

SC

ENT

& A

DU

LT L

ITER

AC

Y

58(

2)

OC

TOB

ER 2

014

FEATURE ARTICLE

is integrated into the Common Core English Language Arts (ELA) Standards to promote literacy. Because the use of digital technology is not a separate strand, but rather, is integrated into the ELA standards, teachers may not be aware of the extent to which in-struction involving digital technology is expected. Second, we wish to help teachers envision how these technology-related standards can be addressed and in-tegrated with other non-technology-specific standards. To that end, we reviewed the existing literature to identify the ways in which the digital tools and proj-ects identified could be used to address both digital and non-digital strands of the CCSS.

Theoretical Framework The use of digital tools to promote literacy in grades 6–12 classroom contexts is the focus of the research described in this article. Research suggests that the study of new literacies in adolescent classroom con-texts is important because teachers must prepare stu-dents to become literate in using digital tools and engaging in activity in online contexts to be success-ful in the 21st century workplace, and students must develop multiple literacies related to using digital technology (Leu, Kinzer, Coiro, & Cammack, 2004 ; Leu, O ’ Byrne, Zawilinski, McVerry, & Everett-Cacopardo, 2009 ). Thus, our review is grounded in several aspects of theories of new literacies (Kress, 2003 ; Leu et al., 2004 ; Lankshear & Knobel, 2007 ).

First, proponents of new literacies propose that teachers need to see literacy as broader than just read-ing printed text (Gee, 2003 ; Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2001 ; Kress, 2003 ; Lankshear & Knobel, 2007 ) and change their instruction accordingly (O ’ Brien & Bauer, 2005 ). Bailey ( 2009 ) asserts that “too many sec-ondary teachers resist seeing literacy as dynamic, and therefore they do not make the changes in their in-struction and curricula that are necessary to make lit-eracy instruction for today ’ s adolescents more relevant to young lives and challenging in ways that will truly engage modern youth” (p. 210). Further, we must rec-ognize that literacy practices are embedded within so-cial contexts (Gee, 2001 ) and are connected to social purposes (Barton, Hamilton, & Ivanic, 2000 ). Not only does literacy occur within social contexts, but digital tools provide new and increased opportunities for so-cial interaction and collaboration, and therefore pro-vide new learning opportunities and contexts. Thus, the social and collaborative aspects and contexts of lit-eracy must be addressed in classroom instruction.

Another important aspect of new literacies in re-lation to our review is the idea that digital technolo-gies produce new multimodal text formats as traditional text is combined with sound, images, and colors in increasingly complex ways. To that end, Kress ( 2003 ) argues that the screen has replaced printed text as the primary mode of communication in society. This shift, and the affordances of digital technology for communicating ideas, has significant implications for the classroom. Students must not only understand that color, image, sound, and alpha-betic text each carry meaning in different ways, but also that they are complementary and interactive (Kress, 2003 ). As Lemke ( 1998 ) states:

Meanings in multimedia are not fixed and additive (the word meaning plus the picture meaning), but multiplicative (word meaning modified by image context, image meaning modified by textual context), making a whole far greater than the simple sum of its parts (pp. 283–284, emphasis added) .

A final aspect of new literacies theory informing our review is that digital contexts for reading and writ-ing require unique skills, strategies, and dispositions (Coiro, 2007; Leu, Kinzer, Coiro, and Cammack, 2004 ) for comprehension. As such, students must be taught the skills to locate, critically evaluate, synthe-size, and communicate information from the Internet. These skills, strategies, and dispositions must be taught and reinforced in the classroom to help students become fully literate by today ’ s defini-tion of literacy. With these tenets in mind, we exam-ine uses of digital technology in literacy instruction and illustrate how digital technology can be used to address both technology-specific and non-technol-ogy-specific Common Core ELA standards.

Method The studies and connections offered in this paper are drawn from our systematic review of the literature pub-lished between the years 2000–2013 on the uses of digital tools to promote literacy in grades 6–12 class-rooms. We analyzed the empirical literature on this topic using a content analysis approach (Krippendorff, 2004 ) to study trends, uses, and outcomes of employ-ing digital tools in classrooms. We searched three ma-jor search engines in education (ERIC, Education Research Complete, and Education Full Text) and conducted hand searches of major journals in literacy

149

The

Pot

enti

al o

f D

igit

al T

echn

olo

gies

to

Sup

por

t L

iter

acy

Inst

ruct

ion

Rel

evan

t to

the

Com

mon

Cor

e S

tate

Sta

ndar

ds

to retrieve articles. Our search yielded 491 articles, and we narrowed our pool of research to 36 studies after excluding studies conducted in higher education, lit-erature reviews, commentary, or non-empirical re-search. Further, we did not consider research that took place in after-school or pullout reading programs be-cause we wanted to investigate studies representative of traditional classroom contexts and environments.

We also recognize that many studies have been published regarding the integration of technology into classroom environments, but often those studies

do not focus on literacy or literacies promoted by technology. Thus, we excluded studies that did not make explicit connections to literacy and/or language arts. This approach also excluded broader studies, such as evaluation of one-to-one laptop programs, which may have involved the use of digital tools for literacy purposes, but whose purpose was not to focus on literacy. Of the 36 studies, 10 met our parameters and were conducted in grades 6–12 classrooms. Table describes each study and provides additional informa-tion about the context of each study.

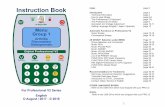

TABLE Description of Articles Reviewed

Representative Study Number/Age/Grade of Students and Content Area of Study Digital Tool Aim of Project(s)

Bailey ( 2009 ) 28 ninth-grade students in a suburban high school in the Northeastern US

PowerPoint To represent students’ interpretations of poetry using multimodal features of PowerPoint software.

Castek & Beach ( 2013 )

Sixth- and seventh-grade students in middle school science classrooms

iPad/tablet apps To have students collaborate, create, and organize texts in science to promote disciplinary literacy using various iPad apps.

Colwell, Hunt-Barron, & Reinking ( 2013 )

48 seventh-grade female students in two sections of a science class in the Southeastern US

Laptops with Internet To guide students in gathering and evaluating information on the Internet.

Curwood & Cowell ( 2011 )

Three 10th-grade English classes in Midwestern US

Webpage design tools

To extend students’ analysis of poetry to the development of online digital pages to represent poems in a digital, graphic format.

Grisham & Wolsey ( 2006 )

Three classes of eighth-grade students in a middle school in Southern CA

Online threaded discussion boards

To engage students in asynchronous discussion about young adult literature.

Hughes ( 2009 ) 11th-grade students PhotoStory 3, iPhoto, PowerPoint, Corel, iMovie, Flash

To have students create multimodal poetry presentations.

O ’ Brien, Beach, & Scharber ( 2007 )

15 seventh- and eighth-grade struggling readers in a writing intervention class in the Twin Cities

PowerPoint Writing software (i.e., Comic Life) Radio play digital tools

To engage students in multimodal writing and culminating PowerPoint presentations.

Smythe & Neufelt (2010)

Sixth- and seventh-grade English Language Learners in a language arts class in Canada

Podcasts To engage ELLs in podcasting through writing and recording stories for third-grade students and then uploading the recording to an Internet server.

Tarasiuk ( 2010 ) 252 students in grades 6–8 in the suburbs of Chicago

Wiki To engage students in writing and editing information about novels in literature on a class wiki.

Wolsey & Grisham ( 2007 )

One English teacher ’ s eighth-grade middle school classes in Southern California

Online threaded discussion

To facilitate students’ online, collaborative conversations about literature.

150

JOU

RN

AL

OF

AD

OLE

SC

ENT

& A

DU

LT L

ITER

AC

Y

58(

2)

OC

TOB

ER 2

014

FEATURE ARTICLE

This article considers these studies to present: (a) ways in which digital tools have been integrated into grades 6–12 literacy instruction and (b) ideas about how the digital tools might be used to support teaching with the CCSS.

A Discussion of Research We reviewed the literature and used our theoretical framework to organize the studies into four themes that are discussed in the following subsections. Although some studies aligned with multiple themes, due to space limitations we discuss each study within only one theme.

Reading and Writing Multimodal Texts The consumption and production of multimodal texts are among the most prominent ways that the CCSS require students to use digital technology. The standards state that students should be able to both evaluate content presented in diverse media formats as well as use digital media to convey information. Therefore, both creating and understanding multi-modal texts is of importance for classroom instruc-tion. Of the studies we reviewed, multimodal texts were read and created in various ways. Associations with using PowerPoint in the classroom often evoke images of lecture and teacher-centered instruction. Yet, PowerPoint contains various features, such as au-dio and hyperlink tools, that students may use to de-velop complex, multimodal products of learning. Bailey ’ s ( 2009 ) study reported how students used PowerPoint to present personal, multimodal interpre-tations of poetry. Bailey suggested that creating multi-modal interpretations through PowerPoint presentations required students to engage in study of purpose when creating a digital interpretation and consideration of the audience to which the interpre-tation would be presented. Also, students felt empow-ered by using PowerPoint and their knowledge of the ways that color, sound, and image influence meaning because the tool provided a way to communicate their point of view.

Curwood and Cowell ( 2011 ) used multimodal webpage design tools to help students interpret and represent poetry. The construction of online content required that students consider the use of images, em-bedded texts and transitions, audio, timing, and modes of representation to illustrate imagery, mood, and literary techniques, and these multimodalities were literacies associated with using digital tools

(Kress, 2003 ). Thus, multiple types of literacy, rang-ing from technical practices to interpretive skills, can be supported by integrating webpage design into the English curriculum. Additionally, Curwood and Cowell ( 2011 ) found that students who often strug-gled with traditional literacy practices, such as print-based reading and writing, were successful in the higher-level literacy practices involved in webpage design, such as analytical thought and symbolic rep-resentation of ideas.

Another study (Hughes, 2009 ) reported on help-ing students learn how to read and create multimodal presentations by having students view and create digi-tal poems. Prior to creating their own digital poetry performance, students viewed digital poems, examin-ing modes of expression, looking at the visual images, the written text, the narration (voice), and the musi-cal soundtracks that played in the background, and considered how these different modes converged and were complementary. As a result, students created multimodal and multi-linear presentations, spontane-ously collaborated with each other, felt that they were writing for an authentic audience, and shifted their views of poetry from negative to positive.

CCSS connections . Beyond the Common Core standards aimed at using digital technology to read and write multimodal texts, the digital tools used in these studies could also be used to address non-technology-specific standards such as those listed in Figure 1. For example, students must assess point of view or purpose, as described in the previous section, when studying and interpreting the content and style of poems (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.6). Also, PowerPoint productions may be considered a form

FIGURE 1 Additional Anchor Standards Relevant to Using Digital Tools for Reading and Writing Multimodal Texts

151

The

Pot

enti

al o

f D

igit

al T

echn

olo

gies

to

Sup

por

t L

iter

acy

Inst

ruct

ion

Rel

evan

t to

the

Com

mon

Cor

e S

tate

Sta

ndar

ds

of writing as they express ideas and are products of students’ interpretations. The CCSS specify that stu-dents must “write informative or explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization and analysis of content” (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.2). Although students may or may not write traditional, text-only sentences when devel-oping PowerPoint presentations for interpretation or explanation, these presentations can be used to ex-amine and convey complex ideas and information. Further, the development of webpages for projects such as Curwood and Cowell ’ s ( 2011 ) encourages students to demonstrate understanding of figurative language (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.L.5) and be knowledgeable in how language works in different contexts to make effective choices for meaning or style (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.L.3).

Collaboration The CCSS also call for students to use digital tools to interact and collaborate with others. Castek and Beach ( 2013 ) highlight many ways that tablet apps can foster digital collaboration and create a connec-tion between digital and disciplinary literacies. They encouraged collaboration by having students use Diigo (a social bookmarking/annotation app) to an-notate articles arguing for and against a controversial issue. Students were able to leave digital sticky notes in the articles to pose questions and reflections within the articles and then use Diigo ’ s collaboration feature to share the notes with other students in the class. The researchers noted that by sharing their digital an-notations, students were exposed to differing re-sponses and differing text interpretations. Students also used sticky note annotations to respond to each other ’ s claims about the text.

Students in Castek and Beach ’ s ( 2013 ) study also used Voicethread, a tool for creating multimodal pre-sentations, as a collaboration tool. Students created Voicethreads about what caused the extinction of the dinosaurs by inserting images relevant to their ideas and adding voice-overs explaining their predictions. Students then viewed one another ’ s Voicethreads and offered critiques through the text and audio com-ments feature, which “exposed [students] to compet-ing arguments as well as different interpretations of the evidence collected from the articles they read” through which some students “referenced one an-other ’ s arguments to formulate their own counterar-guments along with evidence supporting those

counterarguments, a practice central to inquiry-based science” (Castek & Beach, 2013 , p. 562).

Another study that illustrated collaboration with digital tools was that of O ’ Brien, Beach, & Scharber ( 2007 ) in which students create PowerPoint presenta-tions about video games and the design of an ideal city that they mapped, populated with fictional char-acters, and wrote about. They also collaborated to cre-ate a story that they turned into a radio play and performed. O ’ Brien and colleagues found that stu-dents were able to use their prior knowledge from out-of-school practices and social capital to support collaborative work on multimodal projects. As a re-sult, students were more likely to express opinions or judgments in which they were granted some power or agency and were more socially engaged in writing activities.

Finally, Grisham and Wolsey ( 2006 ) and Wolsey and Grisham ( 2007 ) reported on using electronic threaded discussion groups to facilitate collaborative conversations about literature. They found that the asynchronous nature of online discussion prompted students to think more critically about their responses to literature and to members of their groups than did a paper journal or face-to-face discussions. Students also developed critical literacy skills because the col-laborative discussions forced students to consider each other ’ s viewpoints.

CCSS connections . The aforementioned collaborative digital projects also address many Common Core standards beyond using digital technology to collaborate (see Figure 2). For example, Castek and Beach ’ s use of Diigo required students to closely read texts and cite specific textual evidence when writing to support conclusions drawn from the text (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.1). When reading pro and

FIGURE 2 Additional Anchor Standards Relevant to Using Digital Tools for Collaboration

152

JOU

RN

AL

OF

AD

OLE

SC

ENT

& A

DU

LT L

ITER

AC

Y

58(

2)

OC

TOB

ER 2

014

FEATURE ARTICLE

con articles on a controversial topic, students also had to analyze two texts addressing similar topics and compare the viewpoints of the authors (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.9). In reading these articles writ-ten from pro and con perspectives, students had to consider how the author ’ s word choices shaped the meaning and tone of the text (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.4). In each of the collaborative projects de-scribed, students had to evaluate the arguments and claims written by their peers to assess the validity of their reasoning and the sufficiency of their evidence (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.8). Further, in each collaborative project, students had to read and com-prehend informational texts in order to participate with their peers (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.10).

Collecting Resources The CCSS also call for students to use digital tech-nology to “gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources, assess the credibility and accuracy of each source, and integrate the informa-tion while avoiding plagiarism” (CCSS Initiative, 2010). One study in our review (Colwell, Hunt-Barron, & Reinking, 2013 ) guided students in gath-ering and evaluating information through a process called Internet Reciprocal Teaching (IRT). IRT is an instructional framework that they used to guide students in developing questions, locating, evaluat-ing, synthesizing, and communicating information found online as part of a science inquiry project. Although use of the IRT framework was seemingly effective at first, they noted some challenges that teachers should be aware of when using IRT. Specifically, teachers should be wary of relying on teacher-centered instruction and student reliance on teacher knowledge, should carefully structure assign-ments and describe clear expectations, and should create parameters to help prevent students from solely relying on their previous Internet experience in lieu of implementing the new strategies presented to them.

Another study (Tarasuik, 2010 ) in our review re-ported on helping students gathering information digitally through the use of a wiki, an online tool that allows users to post and edit written and visual content in a shared space. Wiki technology is often used to have students collectively create a database of learned information on a common topic, encour-aging reading, writing, and editing skills. Tarasuik had students create wiki pages to gather and orga-nize information about vocabulary, summaries, and

characterization as they read novels. Students com-bined information from the text with images and in-formation that they found online. Students then used the information to create digital book talks about their novels. In addition to helping them gather resources, use of the wiki engaged students in collaboration and consideration of others’ ideas, en-hancing social aspects of learning (Lankshear & Knobel, 2011 ).

CCSS connections . Multiple Common Core standards, beyond using digital tools to gather information, were addressed in these studies. For example, students in Tarasiuk ( 2010 ) study were required to read novels and add information about those novels to the class wiki, requiring students to engage in multiple literacy activ-ities that ranged from the consideration and analysis of texts for themes, perspective, and summary (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.2, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.3, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.6). To convey mastery of these literacy skills through a wiki activity, students must also use multiple forms and purposes of writing such as writing informative or ex-planatory texts to examine and articulate information clearly, produce clear writing appropriate to task, pur-pose, and audience, and use technology to produce and publish writing on a wiki (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.2, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.4, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.6). Further, because a wiki is a common online space where information may be added and edited, students in Tarasuik ’ s study devel-oped and strengthened their writing through multiple types of editing and rewriting (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.5). See Figure 3 for a complete listing of the relevant standards.

FIGURE 3 Additional Anchor Standards Relevant to Using Digital Tools for Collecting Resources

153

The

Pot

enti

al o

f D

igit

al T

echn

olo

gies

to

Sup

por

t L

iter

acy

Inst

ruct

ion

Rel

evan

t to

the

Com

mon

Cor

e S

tate

Sta

ndar

ds

Sharing Information and Soliciting Feedback In addition to the ways already described, the CCSS call for students to use digital technology to share information. Specifically, the standards state:

1 . Use technology, including the Internet, to pro-duce and publish writing and to interact and collaborate with others (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.6).

2 . Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and en-hance understanding of presentations (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.5).

One way that students shared information in the studies reviewed was through podcasts. Smythe and Neufeld ( 2010 ) reported on how students created en-hanced podcasts (meaning they included images) of stories written for third-grade students. Students in this study wrote content for podcasts to use as aids when speaking, and data indicated that students felt that they were writing for a wider audience than the teacher and other students in the class as they wrote this content. Thus, this activity was consistent with the perspective that literacy is a social practice (Gee, 2003 ). The authors also noted that the transformation of writing into speech to create the podcast mitigated some language barriers, such as spelling and punctu-ation, that many ELLs struggle to master, creating a more positive learning environment where students felt supported by their achievements and were able to make connections to their out-of-school lives through the personal stories they created and shared in the podcasts, creating a bridge between students’ in- and out-of-school literacies (Moje, 2009 ).

Although Smythe and Neufeld ’ s ( 2010 ) study did not report that students solicited feedback on their podcasts, podcasts may also be used to solicit feedback through comments that can be posted where the podcast is hosted. Additionally, many of the other tools already described in this review (such as Diigo, Voicethread, and wikis) can be used to share information and solicit feedback from others.

CCSS connections . By first writing podcast content, students engage in writing informative texts that ef-fectively select, organize, and analyze content (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.2). Students also use tech-nology to publish that writing through collaboration with others (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.6), albeit

the writing is published in the form of oral language. Thus, anchor standards for speaking are targeted as well. According to CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.5, students should make strategic use of digital media to express information, which is the focal activity in a podcast. Further, as Smythe and Neufeld ( 2010 ) illus-trate, podcasts may be an effective method to engage English Language Learners in speech, which pro-motes command of formal English through speech (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.6). See Figure 4 for a complete listing of these relevant standards.

Implications for Using Digital Tools to Promote Literacy Here we consider the studies reviewed in light of the-ory that framed this research and provide practical implications for grades 6–12 classrooms. Knowing that, in the space of this manuscript, we cannot pro-vide connections for each individual content area at both middle and high school levels, we invite the reader to consider the practical implications offered for each tool and the connections we drew to the CCSS to determine applicable uses for their class-rooms and for teacher education. However, we dis-cuss broad implications for using digital tools in 6–12 classrooms to support teaching with the CCSS.

The Importance of Social Context in Supporting Literacy In each of the studies presented in this article, stu-dents were working together to create and understand new information, or were creating a digital project for others to view or listen to. This social context empow-ered students in several ways. First, by collaborating, they were able to co-construct knowledge to form

FIGURE 4 Additional Anchor Standards Relevant to Using Digital Tools to Share Information and Solicit Feedback

154

JOU

RN

AL

OF

AD

OLE

SC

ENT

& A

DU

LT L

ITER

AC

Y

58(

2)

OC

TOB

ER 2

014

FEATURE ARTICLE

ideas and products that they may not have on their own. This idea is consistent with Lankshear and Knobel ’ s ( 2007 ) notion of new literacies. They de-scribe how Web 2.0 tools enable expertise and au-thority to become collective and distributive rather than centralized as well as the benefits of having mul-tiple users, with their multiple perspectives, create together to generate knowledge. Thus, the digital tools in these studies, and the ways teachers had stu-dents collaborate in order to leverage the affordances of the tools, enabled students to learn from each other and create knowledge and products greater than any individual could. Further, Street ( 2001 ) defines liter-acy practices as particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing in cultural contexts. This definition of literacy leads us to further appreciate the value of the way these digital tools were used in these classrooms. Teachers were providing opportunities for students to become literate in new ways by pre-senting them with new digital contexts. This literacy opportunity is particularly important, given that these online spaces provide the cultural context in which many adolescents read and write.

Additionally, because many of these digital tools promote production of material that is viewable or accessible by multiple people who are often outside of the walls of the classroom, they allow students to compose for a broad audience, which may also play a role in empowering students. Providing students an audience beyond the teacher or the classroom em-phasizes the value of student knowledge and of en-gaging students in global conversations to promote new types of skills and dispositions associated with using digital tools for communication (Coiro et al., 2008 ). Although research has suggested awareness of audience may initially concern students (Merchant, 2005 ) and some students may focus too heavily on appearance and format of online writing instead of content (Grisham & Wolsey, 2006 ), these constraints usually lessen with continued use of digital tools, suggesting the importance of familiarizing students with digital tools and providing multiple low-stakes opportunities for students to use digital tools in a manner that improves content learning. Also, be-cause students were producing digital materials for a broader audience of their peers (Curwood & Cowell, 2011 ; Smythe & Neufeld, 2010 ), they engaged in ex-tensive revision and editing, which aligned with more traditional literacy skills and connect new lit-eracies to traditional literacies (Hinchman et al., 2004/2005).

Broadening Literacy Instruction Through the Use of Digital Tools The research studied here also illustrates ways in which teachers can integrate digital technology into instruction to enhance literacy instruction to simulta-neously support both digital and non-digital literacy skills because literacy is considered in a broader per-spective that encompasses multiple practices beyond traditional reading skills (Gee, 2003 ; Lankshear & Knobel, 2007 ). Primarily, the studies suggested how digital tools might complement and enhance instruc-tion of traditional literacy skills to create a bridge to teach existing content in more meaningful ways. An oft-cited teacher concern for the integration of digital tools into instruction is that the tools may be an add-on to instruction and increase the amount of time a teacher spends planning and implementing literacy instruction (Hutchison & Reinking, 2011 ). Yet, the literature reviewed in this article illustrates how digi-tal tools can be integrated to enhance existing instruc-tion and simultaneously teach and connect more skills, particularly multimodalities (Kress, 2003 ).

This review suggested that there is value in allow-ing students to represent ideas in a manner that com-bines traditional, print-based texts with non-linguistic elements of communication, usually displayed through graphic and oral representations of learning. Through such activities, students were able to more vividly express ideas and opinions involving traditional literacy practices, such as analysis and critical think-ing, by also considering elements of color, image, and sound, which aligns with Kress ’ s ( 2003 ) perspective of developing literacy through technology. Yet, some studies did note concerns that digital tools may be used in perfunctory ways that do not necessarily sup-port literacy learning and multimodal skills (Bailey, 2009 ; Smythe & Neufeld, 2010 ). Thus, continued re-search is necessary to understand the balance required to optimally integrate digital tools to support literacy.

Bringing Out-of-School Digital Practices into the Classroom Finally, these studies suggested the potential of digital technology for bridging traditional and new literacies to connect what are often called in- and out-of-school practices (Hinchman, et al., 2003/2004 ). By integrat-ing digital tools into the K–12 classroom, students may be able to use familiar literacy practices from their out-of-school literacy repertoire, such as blog-ging, discussing content online, and app-using. These practices may help students connect their out-of-

155

The

Pot

enti

al o

f D

igit

al T

echn

olo

gies

to

Sup

por

t L

iter

acy

Inst

ruct

ion

Rel

evan

t to

the

Com

mon

Cor

e S

tate

Sta

ndar

ds

school lives to school to make instruction more rele-vant and as background knowledge for new learning (Alvermann, 2008 ).

However, many students, particularly adolescents, have already established practices for locating infor-mation online, and these practices may conflict with instruction aimed at improving online comprehen-sion (Colwell et al., 2013 ). Instruction that considers online research and literacy strategies that adolescents bring to the classroom from their out-of-school digital practices may better support students in locating, criti-cally evaluating, synthesizing, and communicating information from the Internet. Theory suggests that these skills are critical to successful online reading comprehension (Coiro, 2007; Leu, Kinzer, Coiro, and Cammack, 2004 ), and addressing these out-of-school practices and skills may bridge out-of-school literacies to in-school instruction that aligns with the CCSS.

Overall themes and findings from the studies considered here support the instantiation of new lit-eracies into middle and high school literacy instruc-tion and make direct connections to theory. However, we also use these studies and this article to identify practical methods for how digital tools are successfully being used in grades 6–12 classrooms and how those methods may seamlessly align with both digital and non-digital strands of the CCSS. We recognize that the adoption of the CCSS is a heavily debated topic, with numerous points and counterpoints readily available. Yet, many teachers are being asked to revise their curricula or use re-vised curricula to target the CCSS in instruction. Thus, we considered how the instructional methods discussed in the studies described in this article may already align with the CCSS to illustrate how digital tools can provide a viable option for integrating mul-tiple standards into middle and high school content instruction. We encourage educators to consider these studies as examples of how digital tools may be a bridge to implementing the CCSS in a manner consistent with current pedagogical goals and to target multiple literacy skills in grades 6–12 instruction.

References Alvermann , D.E. ( 2008 ). Why bother theorizing adolescents’ on-

line literacies for classroom practice and research? Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 52 ( 1 ), 8 – 19 . doi: 10.1598/JAAL.52.1.2

Bailey , N.M. ( 2009 ). “It Makes It More Real”: Teaching New Literacies in a Secondary English Classroom . English Education , 41 ( 3 ), 207 – 234 .

Barton , D. , Hamilton , M. , & Ivanic , R. (Eds.) ( 2000 ). Situated literacies: Reading and writing in context . London, England : Routledge .

Castek , J. , & Beach , R. ( 2013 ). Using apps to support disciplinary literacy and science learning . Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 56 ( 7 ), 554 – 564 . doi: 10.1002/JAAL.180

Coiro , J. , Knobel , M. , Lankshear , C. , & Leu , D.J. ( 2008 ). Central issues in new literacies and new literacies research . In J. Coiro , M. Knobel , C. Lankshear , and D.J. Leu (Eds.), The handbook of research in new literacies . Mahwah, NJ : Erlbaum .

Coleman , D. ( 2011 ). Bringing the common core to life . Retrieved March 20, 2013, from http://usny.nysed.gov/rttt/resources/bringing-the-common-core-to-life.html .

Colwell , J. , Hunt-Barron , S. , & Reinking , D. ( 2013 ). Obstacles to developing digital literacy on the Internet in middle-school science instruction . Journal of Literacy Research , 45 ( 3 ), 295 – 324 . doi: 10.1177/1086296X13493273

Curwood , J. , & Cowell , L.H. ( 2011 ). iPoetry: Creating Space for New Literacies in the English Curriculum . Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 55 ( 2 ), 110 – 120 . doi: 10.1002/JAAL.00014

Take ActionS T E P S F O R I M M E D I A T E I M P L E M E N T A T I O N

1 . Review your own state ’ s standards for the grade level you teach . Evaluate the extent to which you are addressing the digital standards through your current instruction. What are you missing? Make a long-term plan to determine how you can address all of these digital standards during the course of a school year with the digital tools available to you. Use the examples in this article to help you think about the many ways that you can meaningfully integrate digital technology.

2 . Make a list of all the digital tools available to you that you are not currently using. Choose one of those tools and determine how you can use it to teach both digital and non-digital standards. It is important to expose students to different websites, apps, and types of digital technology. Visit this site for ideas about using various digital tools: http://fcit.usf.edu/matrix/digitaltools.php .

3 . If you are having a difficult time getting started, consider using a planning tool such as the Technology Integration Cycle for Literacy and Language Arts (Hutchison & Woodward, 2014 ; see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/trtr.1225/abstract ). This planning tool guides teachers in selecting digital tools and integrating them in a way that ensures alignment to the instructional goals.

156

JOU

RN

AL

OF

AD

OLE

SC

ENT

& A

DU

LT L

ITER

AC

Y

58(

2)

OC

TOB

ER 2

014

FEATURE ARTICLE

Gee , J.P. ( 2001 ). Reading as situated language: A sociocognitive perspective . Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 44 , 714 – 725 .

Gee , J. ( 2003 ). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy . New York, NY : Palgrave .

Grisham , D.L. , & Wolsey , T.D. ( 2006 ). Recentering the middle school classroom as a vibrant learning community: Students, literacy, and technology intersect . Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 49 ( 8 ), 648 – 660 .

Hinchman , K.A. , Alvermann , D.E. , Boyd , F.B. , Brozo , W.G. & Vacca , R.T. ( 2003/2004 ). Supporting older students in- and out-of-school literacies . Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 47 ( 4 ), 304 – 310 .

Hughes , J. ( 2009 ). New Media, New Literacies and the Adolescent Learner . E-Learning , 6 ( 3 ), 259 – 271 .

Hutchison , A. , & Woodward , L. ( 2014 ). A Planning Cycle for Integrating Technology into Literacy Instruction . Reading Teacher , 67 ( 6 ), 455 – 464 . doi: 10.1002/trtr.1225

Hutchison , A. , & Henry , L. ( 2010 ). Internet use and online read-ing among middle-grade students at risk of dropping out of school . Middle Grades Research Journal , 5 ( 2 ).

Hutchison , A.C. & Reinking , D. ( 2011 ). Teachers’ perceptions of integrating information and communication technologies into literacy instruction: A national survey in the U.S . Reading Research Quarterly , 46 ( 4 ), 312 – 333 . doi: 10.1002/RRQ.002

Kress , G. ( 2003 ). Literacy in the new media age . New York, NY : Routledge .

Kress , G. , & Van Leeuwen , T. ( 2001 ). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication . New York, NY : Oxford University Press .

Krippendorff , K. ( 2004 ). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology . Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage Publications Inc .

Lankshear & Knobel ( 2007 ). A new literacies sampler . New York, NY : Peter Lang .

Lankshear & Knobel ( 2011 ). New literacies: Everyday practices and classroom learning ( 3rd ed. ). New York, NY : Open University Press .

Lemke , J.L. ( 1998 ). Metamedia literacy: Transforming meanings and media . In D. Reinking , M.C. McKenna , L.D. Labbo , & R.D. Kieffer (Eds.), Handbook of literacy and technology: Transformations in a post-typographic world (pp. 283 – 301 ). Mahwah, NJ : Erlbaum .

Leu , D. J. , Jr. , Kinzer , C. K. , Coiro , J. , & Cammack , D. ( 2004 ). Toward a theory of new literacies emerging from the Internet and other information and communication technologies . In R. B. Ruddell & N. Unrau (Eds.), Theoretical models and pro-cesses of reading ( 5 t h Ed. ). ( 1568 – 1611 ). International Reading Association : Newark, DE .

Leu , D.J. , O ’ Byrne , W.I. , Zawilinski , L. , McVerry , J.G. , & Everett-Cacopardo , H. ( 2009 ). Expanding the new literacies conversa-tion . Educational Researcher , 38 ( 4 ), 264 – 269 . doi: 10.3102/0013189X09336676

Madden , M. , Lenhart , A. , Duggan , M. , Cortesi , S. , & Gasser , U. ( 2013 ). Teens and technology . Pew Internet & American Life Project . Retrieved from ht tp://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teens-and-Tech.aspx .

Merchant , G. ( 2005 ). Digikids: Cool Dudes and the New Writing . E-Learning , 2 ( 1 ), 50 – 60 .

Moje , E.B. ( 2009 ). A call for new research on new and multi-literacies . Research in the Teaching of English , 43 ( 4 ), 348 – 362 .

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers . ( 2010 ). Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects . Washington, DC : Authors .

O ’ Brien , D. , Beach , R. , & Scharber , C. ( 2007 ). “Struggling” middle schoolers: Engagement and literate competence in a reading writing intervention class . Reading Psychology , 28 ( 1 ), 51 – 73 .

O ’ Brien , D.G. , & Bauer , E. ( 2005 ). New literacies and the institu-tion of old learning . Reading Research Quarterly , 40 , 120 – 131 .

Smythe , S. , & Neufeld , P. ( 2010 ). “Podcast Time”: Negotiating Digital Literacies and Communities of Learning in a Middle Years ELL Classroom . Journal Of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 53 ( 6 ), 488 – 496 . doi: 10.1598/JAAL.53.6.5

Street , B. ( 2001 ). Introduction . In B. Street (Ed.), Literacy and Development: Ethnographic Perspectives . London, England : Routledge .

Tarasiuk , T.J. ( 2010 ). Combining traditional and contemporary texts: Moving my English class to the computer lab . Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 53 ( 7 ), 543 – 552 . doi: 10.1598/JAAL.53.7.2

Wolsey , T.D. , & Grisham , D.L. ( 2007 ). Adolescents and the new literacies: Writing engagement . Action in Teacher Education , 29 ( 2 ), 29 – 38 .

More to ExploreC O N N E C T E D C O N T E N T - B A S E D R E S O U R C E S

✓ Visit http://www.corestandards.org/ to learn more about the Common Core State Standards, or click on the active links to the standards throughout the digital version of this article .