The form and function of young children's magical beliefs

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of The form and function of young children's magical beliefs

Developmental Psychology1994, Vol. 30, No. 3, 385-394

Copyright 1994 by the American Psychological Association, Inc.0012-1649/94/S3.00

The Form and Function of Young Children's Magical Beliefs

Katrina E. Phelps and Jacqueline D. Woolley

Research and common lore suggest that children subscribe to a rich world of fantasy, includingbeliefs about magical entities and events. This study explores how children use magic to explainevents they witness in the real world. Children 4, 6, and 8 years of age were asked a set of interviewquestions designed to assess general magical beliefs. They were then presented with physical eventsand were asked to predict and explain their occurrence and to state whether they believed the eventswere magical. The extent of children's magical beliefs, as measured by the interview, decreased withage. Regarding explanations of events, the availability of correct physical explanations for the eventsaccounted for a significant portion of the variance in children's claims that the events were magic.Findings suggest that magic is used by children as an explanatory tool when they encounter eventsthat both violate their expectations and elude adequate physical explanation.

In his assessment of comparative religion, Horton (1979)contended that the elaborated theoretical systems derived fromboth science and the supernatural "attempt to explain and in-fluence the working of one's everyday world by discovering theconstant principles that underlie the apparent chaos and flux ofsensory experience" (p. 355). Indeed, the development of orga-nized, explanatory systems of knowledge seems an integral partof human nature; it allows people to categorize objects andevents and to make predictions on the basis of their experiences(Carey, 1985; Keil, 1989). In American society, the quest foranswers to the questions how and why begins early in life; by thepreschool years, children are actively seeking explanations foran abundance of physical and social events (Callanan & Oakes,1992; Dunn, 1988; Hood & Bloom, 1979) and are able to pro-vide explanations for a growing number of experiences in theirworld (Barbieri, Colavita, & Scheuer, 1990; Bullock, Gelman, &Baillargeon, 1982; Donaldson, 1986; S. A. Gelman & Kremer,1991). It is assumed that gradually, as children acquire bothgeneral and domain-specific knowledge about the varied andcomplex causal forces at work in the environment, their attri-butions come to resemble those of adults. In Horton's terms,children and adults come to use the same principles to explain"the apparent chaos and flux of sensory experience" they en-counter in the world around them.

Even though most everyday experiences can be explained byprinciples that are based on natural laws, Horton (1979) im-plied that humans also formulate theoretical systems on the ba-sis of supernatural or magical tenets. What evidence is therethat children in western cultures entertain such forms of expla-

This research was supported in part by the University Research Insti-tute at the University of Texas at Austin.

We wish to thank Les Cohen, Paul Harris, Judy Langlois, Karl Ro-sengren, and Eugene Subbotsky for their comments and suggestions. Weare also grateful to Ian Harris for his advice on statistical matters and toAnneBritt Orlik for volunteering her editorial expertise.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed toKatrina E. Phelps or Jacqueline D. Woolley, Department of Psychology,Mezes Hall 330, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78712.

nation? According to the Piagetian classical literature (e.g., Pia-get, 1929, 1930), young children are especially susceptible tomagical thought; they believe that humans can control the fateof external objects and events through various thoughts (suchas wishes) and actions (such as looking or gesturing). Childrenin the preschool years, by this account, tend to erroneously as-cribe human reasons or purposes to matters of mechanicalcause and effect. For example, a young child may attribute thefact that it is raining outside to her wish for it to rain. Althoughit was not Piaget's intent to claim that these types of errors dem-onstrate children's belief in a magical world, he did propose thatchildren possess a qualitatively different understanding of theeffects of various forces in the world from that of adults andthat children apply their naive conceptions to explanations ofnatural phenomena.

To the extent that nonnaturalistic belief systems are formedand used, beliefs in magic and associated magical thinking maybe especially prevalent in young children and might, in the ab-sence of sophisticated scientific knowledge, be evoked forpurposes of explanation. Of particular interest are (a) the degreeto which children engage in "magical thinking" (i.e., adopt be-liefs in magic itself) and, relatedly, (b) whether children's expla-nations of physical reality incorporate certain elements ofmagic. Magic, as implied here, and as defined by Webster's(1959), is "the art which claims or is believed to produce effectsby the assistance of supernatural beings. . . or by a mastery ofsecret forces in nature." The following investigation addressestwo specific questions concerning children's magical beliefs andexplanations: (a) to what extent do children consciously sub-scribe to a concept of magical entities and events, and (b) underwhat conditions do children evoke magical forces to explainreal world events.

The Nature of Children's Magical Beliefs

In addition to the common lore regarding young children'sbeliefs in a magical, mystical world, there is now a growing bodyof research indicating that children maintain a variety of beliefsabout magic. These beliefs include conceptions of magical be-ings as well as magical events.

385

386 KATRINA E. PHELPS AND JACQUELINE D. WOOLLEY

The types of magical beings that exist in children's mindsrange from the commonplace to the supernatural. In a surveyconducted by Rosengren, Kalish, Hickling, and Gelman (inpress), parents of children between the ages of 4 and 6 reporteda substantial degree of belief among their children in both spe-cific event-related figures (Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, andthe Tooth Fairy) and supernatural fantasy figures (fairies, magi-cians, ghosts, witches, monsters, and dragons). The highest de-gree of belief was perceived to be in the event-related figures andthe fantasy figures who perform good deeds. Data from in-terviews with children (Johnson & Harris, 1991) corroboratethese parental perceptions. When asked about their beliefs inthe existence and magical powers of Santa Claus, God, fairies,and witches, 3- and 4-year-old children most often viewed Santaand God as real, fairies as both real and magical, and witches asmagical but not real. In addition, children attributed magicalpowers almost exclusively to supernatural beings over both fa-miliar ordinary beings (e.g., teachers, mommies, or grandpas)and special ordinary beings (e.g., policemen, kings, and pirates).As in the Rosengren et al. (in press) study, primarily the super-natural good beings were judged by children to be real; the evilbeings were deemed make-believe.

Although these interviews reveal significant beliefs in super-natural entities among young children, when asked about un-usual events, children of the same age tend to deny belief inmagical occurrences. For example, in experiments performedby Subbotsky (1985, in press), children were told a story abouta "magic box" that transformed pictures into objects or becamepermeable when magic words were recited. When questionedabout the likelihood of such phenomena in everyday life, a ma-jority of 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children denied the possibility ofthese occurrences. However, when the children were subse-quently left alone in the room with the supposed magic itemfrom the story, nearly all carried out some attempt (such as wav-ing their hands or chanting magic words) to work the type ofmagic they had heard about in the story. These findings suggestthat although children can verbally proclaim disbelief in thepowers of magic, when left alone, their behavior belies a residualcuriosity.

Harris, Brown, Marriott, Whittall, and Harmer (1991) alsofound evidence of latent magical beliefs, by using a similar pro-cedure to investigate children's belief in the potential existenceof an imagined creature. Children 4 and 6 years of age wereshown two empty boxes and were asked to imagine either amonster or a rabbit inside one of the boxes. When questioned,most children denied that the creature was in the box. The ex-perimenter then left the room and the child's behavior towardthe two boxes was recorded. Children of both ages were morelikely to investigate the box with the imagined entity than theneutral box, and half of the children admitted afterward to won-dering if the creature was really in the box. These findings werereplicated with children 3,5, and 7 years of age, with a fairy andan ice-cream cone as the imagined items (Johnson & Harris, inpress). Although very few children initially claimed anythingcould appear in the box, over half adopted a credulous stanceregarding the contents of the imagination box; credulous chil-dren wondered if the imagined item might be in the box, tested

that possibility by opening it, and sometimes evoked magic byway of explanation.

Children's Use of Magical Explanations

In summary, these results portray young children as con-structivists who actively build bodies of knowledge in a varietyof domains, including developing conceptions of both naturaland supernatural entities and events. Whereas to adults, beliefsbased on natural physical principles and beliefs grounded inmagic may appear contradictory, for young children, both ex-planatory systems may successfully serve the purpose of makingsense of an often wondrous world. Accordingly, both mundaneand magical explanations may be acceptable to young children.This raises the question of what might govern children's appli-cation of each of these types of conceptual alternatives. An in-triguing suggestion is offered by Subbotsky (in press) in his dis-cussion of children's adherence to rules of object permanence.He posited that naturalistic thinking dominates children's rea-soning with regard to everyday reality but that unusual circum-stances encourage children's latent magical beliefs to surface.By this account, rather than arbitrarily and indiscriminately in-fusing magic into their world, or maintaining two separate andincompatible sets of beliefs about the world, children invokemagic as an explanatory mechanism to handle events that donot fit with their everyday expectations. Data from several linesof inquiry lend tentative support to this contention.

In evaluating children's causal attributions, researchers useprinciples of "naive physics"; children attend to the physicalprinciples of inertia, constancy, permanence, and noncreation,for example (Johnson & Harris, in press; Wellman & Gelman,1992). These four principles hold that inanimate objects do notspontaneously move, transform their shape or identity, disap-pear, or come into existence. Johnson and Harris (in press) pre-sented children with pairs of outcomes, within which one eventconformed to a given principle and the other violated it (e.g.,drawing a picture vs. a picture appearing by itself), and askedthem to judge whether these events were caused by a real personor by a magic fairy. Three- and 4-year-old children judged thenonviolation events to be ordinary (caused by Jack or Jill) andthe other outcomes as magical (caused by "Magic Fairy").Thus, young children appear to be sensitive to a number ofphysical principles constraining inanimate objects and relegateexceptional events to the domain of magic.

Further evidence suggests that children make this distinctionwith regard to events involving animate objects as well as inan-imate ones. Rosengren et al. (in press) found that 4- and 5-year-old children were very accurate in their ability to discriminatebetween ordinary and extraordinary occurrences of biologicaltransformations. Children at this age understand growth andmetamorphosis to be nonarbitrary, unidirectional changes(from small to large and simple to complex, respectively). Whenpresented with a magician as the agent of change, however, chil-dren chose to suspend these rules and to accept transformationspreviously judged impossible as real and possible with the aidof magic.

The familiarity of the objects involved in particular eventsmay also have an effect on children's use of magic as an explan-

MAGICAL EXPLANATIONS 387

atory tool. Familiar objects, as defined by Nass (1956), are thosethat a child could have possibly (but not necessarily) experi-enced directly, whereas remote objects are beyond the directexperience of a child. A list of causal questions about familiarand remote objects was derived by Berzonsky (1971) and wasadministered to 6- and 7-year-old children. Questions for thefamiliar objects included what makes a clock tick, a kite fly, abicycle go, leaves fall from the trees, and balloons go up intothe air. Remote object questions included what makes the windblow, the moon change shape, the stars shine, the day get dark,and rainbows come out after the rain. The results indicated thatchildren's familiarity with the objects or events about whichthey were questioned produced significant differences in thetype of causal explanations they provided. Questioning childrenabout objects with which they may have been familiar yieldedfewer magical explanations than questions about remote, unat-tainable objects. Accordingly, Berzonsky (1971) identified in-sufficient knowledge and a lack of understanding of logicalphysical relationships as the most important determinants ofnonnaturalistic thought.

A final example of the influence of knowledge and conceptualcomplexity on children's explanations can be found in the do-main of language. Research indicates that children frequentlyoffer magical interpretations of sentences that adults treat asmetaphorical. Winner, Rosenstiel, and Gardner (1976) pre-sented subjects with a set of metaphors, one of which was, "Theprison guard was a hard rock." A common interpretation givenby adults was, "The guard was mean and did not care about thefeelings of the prisoners." In contrast, children's responses oftenpreserved the literal meaning of the sentence: "The king had amagic rock and turned the guard into another rock." In thislatter case, to achieve plausibility, they called on the powers ofmagic to negate the laws of the natural world. In a study re-ported by Reyna (1985), adults and 6- and 9-year-old childrenreceived metaphoric sentences and were directed to interpreteither the noun or verb phrases. Approximately one third of thechildren's responses to the sentences were scored as magical,whereas very few adults gave magical interpretations of the met-aphors. These values were obtained under conditions in whichchildren were explicitly told that the events described in sen-tences occurred in real life.

Collectively, previous studies suggest that young childrenmaintain a variety of beliefs about fantasy figures and magicalforces, and these beliefs are constrained by children's burgeon-ing knowledge and experience with the world. Research alsosuggests that these magical beliefs may serve as an explanatorytool to aid children in dealing with new, and in some cases, per-plexing information. The two primary goals of the presentstudy are to further assess the nature of children's magical be-liefs and to analyze when and why children evoke magic to ex-plain physical events. We expect children to subscribe to a widerange of magical beliefs that may vary depending on their age.However, regarding their use of magic to explain physical phe-nomena, we expect that the availability of physical explanationsfor events will exert a stronger effect on children's claims ofmagic than will age or general magical beliefs. Specifically, wehypothesize that children of all ages will most often claim that

events are magical when the events violate their expectationsand when they lack natural physical explanations for the events.

Pilot Study

To select items to be used in the focal task, we presented to36 children (M = 5 years 10 months, range = 3 years 4 monthsto 8 years 2 months) 14 physical events and gave them a set ofinterview questions assessing magical beliefs (see Appendix A).For each of the physical events, children were asked to providea prediction and an explanation and to state whether theythought the event was magical. (This procedure is describedmore thoroughly in the Materials and Procedure section.) Halfof the children in each of the younger (3-5 years) and older (6-8 years) age groups were given the interview questions first, andthe other half of the children received the event tasks first. Toassess whether the order of interview and event tasks presenta-tion had an effect on children's claims that the events were mag-ical, we performed a 2 (age group: 3-5-year-olds and 6-8-year-olds) X 2 (order: interview first and interview second) analysis ofvariance (ANOVA) on children's claims of magic. This analysisrevealed a significant effect of age, F( 1, 32) = 22.99, p< .0001,but no significant effect of presenting the interview before (M =5.94) or after (M = 6.55) the physical events, and no significantAge X Order interaction. The age effect reflected the older chil-dren's producing fewer claims of magic (M = 3.56) than theyounger children (M = 8.94).

Eight of the 14 items piloted were selected for use in the focaltasks. The items and events were chosen with regard to both thephysical expectations they elicited and the causal mechanismsthey used. (See Appendix B for a description of task items andevents.) The events defied a number of normal physical con-straints: gravity (ball pipe, magnetic pole, and hand boiler); sizeconstancy (magnifier and die trick); color constancy (ficklefoam); object permanence (quarter bank); and inertia (mag-netic disks). When asked to predict what would happen in eachof the events, most of the children in both age groups madepredictions consonant with these physical principles. Thus, thepilot data indicated that even young preschoolers had knowl-edge of these physical constraints governing objects and actionsand had formed expectations on the basis of these principles.

We also selected items with the aim of including events in-volving causal mechanisms known differentially to children ofvarious ages. Events at varied difficulty levels were selected toensure that children of all ages received both events for whichthey were likely to have physical explanations and events forwhich they were unlikely to have such explanations. Children'sability to provide correct physical explanations for the eventsindicated that all children, including the youngest subjects, hadsome knowledge of the concepts of air pressure and magnifyingglasses used in the ball pipe and magnifier events; these weretherefore considered the early causal concepts. The effects ofheat sensitivity and magnetic attraction, demonstrated in thefickle foam, hand boiler, magnetic disks, and magnetic poleevents, were understood by a majority of the older, but not theyounger children. Hence, these were termed middle causal con-cepts. Lastly, the actual magic tricks, including the die trick and

388 KATRINA E. PHELPS AND JACQUELINE D. WOOLLEY

quarter bank, confounded all but a few of the oldest childrenand thus constituted the late causal concepts.'

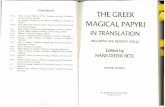

Table 1Percentage of Children Granting Real Status toMagician and Fairy Magic

Method

Subjects

Forty-eight children from three age groups participated: sixteen 4-year-olds (M = 4 years 4 months, range = 3 years 8 months to 4 years 11months); sixteen 6-year-olds (M = 6 years 3 months, range = 5 years 8months to 6 years 10 months); and sixteen 8-year-olds (M = 8 years 1month, range = 7 years 8 months to 8 years 10 months). Twenty-six ofthe subjects were male and 22 were female. Names were obtainedthrough birth records kept on file at the University Children's ResearchLaboratory, and parents were contacted by letter and telephone. Thesubjects were recruited from an ethnically mixed, but predominantlyWhite, middle-class population in a large southwestern American city.

Materials and Procedure

Children were tested individually in a single 15-min session. As pilotdata indicated no significant effect of the order of presenting the in-terview and event tasks, all children initially received the set of inter viewquestions assessing general magical beliefs. The questions were designedto evaluate children's beliefs concerning agents of magic, types of magic,and contexts in which magic can occur. In the first part of the interview,children were asked about their beliefs regarding magicians and fairies.Specifically, they were asked if the two entities could do magic, whatkind of magic they could do, if they did magic in the real world or justin stories, and whether or not they did real magic. In the second part ofthe interview, children were asked about their own powers and the pow-ers of others; questions probed whether they thought the experimentercould do magic, whether they themselves could do magic, and whethersomeone could learn to do magic. (The interview questions are includedas Appendix A.)

Children were then presented with a series of physical events involv-ing the items selected from the pilot study. The event tasks comprisedeight trials presented in two parts: prediction and explanation. T\\z pre-diction portion assessed what children expected to happen with regardto an event before seeing it, and the explanation portion assessed chil-dren's understanding of the principal mechanism underlying each eventonce it was shown to them. In the prediction segment of each trial, chil-dren were presented with eight items, one at a time, and were askedquestions relating to a hypothesized event involving each item (see Ap-pendix B). For example, children were shown two circular magnets andwere asked (a) "If I want to push one of these disks with the other one,will they have to touch for it to move, or can it move by itself?" Onresponding, children were asked (b) why it would happen as they pre-dicted ("Why would they have to/not have to touch?"). The order ofpresentation of the items was randomized across subjects.

The explanation portion of the experiment commenced on comple-tion of the prediction questions for all eight items. In this segment, chil-dren were presented with the test items again, in the order in which theywere originally received. At the onset of the explanation segment of eachtrial, children were reminded of the event they were to consider involv-ing the item and of the prediction they made concerning this event.Children were then shown the event and were asked three additionalquestions: (c) "How do you think this happened?" (this could beprompted with, "What do you think made this happen?"), and (d) "Doyou think this was magic or not magic?" followed by (e) "Do you thinkthis was real magic or just fooling you?" in the cases in which childrenresponded affirmatively to Question d. The order of alternatives pre-sented in Questions d and e was counterbalanced within subjects.

Q8.Q9.

Question (Q)

A fairy does magic in the real worldA magician does real magic

4 years

5075

Age group

6 years

1956

8 years

012

Results

Magical Belief Interview

Recall that children were first asked simply if they believed inmagic (see Appendix A). In response to this question, approxi-mately one third of the children in each age group professed abelief in magic, another third stated they did not believe inmagic, and the final third were uncertain. Despite this split ininitial responses, all children claimed that magicians could domagic (Question 2) and that magicians existed in the real world(Question 7). Most children (79%) were also quite certain thatfairies could do magic (Question 3) and that fairies did realmagic as opposed to "fooling you" magic (Question 10; 92%).In addition, all children believed magicians and fairies diddifferent kinds of magic (Question 6). Children gave a variety ofresponses to Questions 4 and 5 regarding the specific types ofthings magicians and fairies could do. In general, magicianswere associated with making things appear and disappear, pull-ing rabbits and scarves out of a hat, performing card tricks, andcutting people in half; fairies were noted for flying, grantingwishes, transforming objects and people, and taking teeth away.

Two of the interview questions concerning magician and fairymagic revealed significant differences in the magical beliefs ofchildren of different ages. These questions addressed the extentto which children believed magic to be a real process done bybeings in the everyday world. The questions were "Does a fairydo magic in the real world, or just in stories?" (Question 8) and"Does a magician do real magic, or is a magician just foolingyou?" (Question 9). Children's responses were coded in the fol-lowing manner: To Question 8, responses of real world or bothwere coded as 2, / don't know responses were coded as 1, andanswers of just stories were coded as 0. Similarly, to Question 9,answers of real magic or both were coded as 2, answers of/ don'tknow were coded as 1, and responses of just fooling you werecoded as 0. Chi-square analyses indicated a statistically signifi-cant association between response type and age group for eachof the two questions: Question 8, x2(4, N = 48) = 13.09, p <.01, and Question 9, x2(4, N = 48) = 14.12, p < .01. The per-centages of children in each age group granting real status tomagician and fairy magic (responses coded as 2) are presentedin Table 1.

1 Unlike the other events that used natural physical principles toachieve the desired outcomes, both of the tricks involved deception inthe form of hidden compartments, which allowed objects to appear tochange or disappear.

MAGICAL EXPLANATIONS 389

To produce an overall interview score, all yes answers to ques-tions in the magician and fairy magic section of the interviewwere coded as 2, any uncertain responses were coded as 1, andall no answers were coded as 0. Children's scores across Ques-tions 1-3 and 6-10 were then summed to produce an interviewtotal (range = 8-16).2 A one-way ANOVA on interview totalrevealed a statistically significant effect of age, F(2,45) = 8.22,p < .001. Younger children had significantly higher scores thanolder children, with means equaling 13.31, 11.88, and 10.50,for 4-, 6-, and 8-year-olds, respectively. Post hoc Scheffe testsrevealed a statistically significant difference between the scoresof 4-year-olds and 8-year-olds (p < .001) but not between 4- and6-year-olds or 6- and 8-year-olds (ps > .05).

Additional age differences were apparent in children's re-sponses to questions concerning the magical abilities of them-selves and others, presented in the second section of the in-terview. An identical pattern of responses emerged for Ques-tions 11 and 12; when asked if they thought the experimenter orthey themselves could do magic, only 25% of 4-year-olds and31% of 6-year-olds said yes or maybe, whereas 69% of 8-year-olds responded affirmatively. A chi-square analysis on the num-ber of yes, maybe, and no responses given by children in each ofthe three age groups revealed a significant relationship betweenthe two variables, x2(2, N = 48) = 7.37, p < .05. Responses weresimilarly assessed for Question 13; when asked if magic couldbe learned, 100% of 8-year-olds, 75% of 6-year-olds, and 56% of4-year-olds claimed that it could be, x2(2, N = 48) = 8.73, p <.05.

Event Tasks

For each of the eight event tasks, children's predictions ofwhat was going to happen in the event, their physical explana-tions of why it happened, and their claims of magic were as-sessed. Children's predictions for each event were scored as ac-curate (matching what actually happened) or inaccurate. Theexplanations children produced after viewing the events weredivided into three categories: correct physical explanations,guesses, and answers of "I don't know." Any mention of themechanism causing an event (such as magnetism, heat of yourhand, false top, etc.) was coded as a correct physical explana-tion. Guesses were considered to be any attempt at an explana-tion that did not match the correct physical explanation (e.g.,"Maybe air made it happen," "It does it just because," or ""Youdid it like that"). Nearly 25% of the responses given by the 4-year-olds were statements of this type; however, very few (only9%) of the older children's responses constituted guesses. Ineach of these cases, it was clear that the children were not con-vinced that they had a valid causal explanation, but rather itappeared as if they felt pressured to make a guess in response tothe experimenter's question concerning how the event hap-pened. For this reason, guesses were not considered equivalentto physical explanations, and they were counted as a separatecategory. Two independent raters coded all of the data, and in-terrater reliability was .92 (calculated as number of agreementsover number of agreements plus disagreements). Disagreementswere resolved by discussion.

Three separate ANOYAs on children's accurate predictions,

Table 2Percentage of Accurate Predictions, Physical Explanations, andMagic Responses to Items Involving Early,Middle, and Late Causal Concepts

Response

Accurate predictionsEarly causal conceptsMiddle causal conceptsLater causal concepts

Physical explanationsEarly causal conceptsMiddle causal conceptsLater causal concepts

Claims of magicEarly causal conceptsMiddle causal conceptsLater causal concepts

4 years

75199

849

13

387078

Age group

6 years

69229

1002819

34766

8 years

813850

1006659

01638

correct physical explanations, and claims of magic across alleight events revealed significant age effects for each of these fac-tors, respectively: F\2,45) = 5.71, p < .01; F(2,45) = 28.71, p< .0001; and F(2,45) = 14.02, p> < .0001. Table 2 illustrates therange of understanding of the different causal concepts. Recallthat the tasks were divided into three subgroups according tothe level of difficulty of the causal concept encoded in eachevent and task item; early concept items included the ball pipeand magnifier; middle concept items consisted of the ficklefoam, hand boiler, magnetic disks, and magnetic pole; and laterconcept items were the die trick and quarter bank. Most of thechildren in each age group made accurate predictions for theearly causal concept events, whereas fewer did so for the middlecausal concepts, and fewer yet for the later developing concepts.The percentage of accurate predictions made by children in-creased with age. Similar results were obtained for children'sphysical explanations; the availability of correct physical expla-nations for events decreased as causal concepts became moredifficult and increased across age.

Children's claims of magic showed the reverse pattern, withan increase in magical claims for middle and later causal con-cepts and a decrease in magical claims with age. Across all eighttasks, the mean claims of magic were as follows: 4-year-olds,M = 5.13; 6-year-olds, M = 3.25; and 8-year-olds, M = 1.38.Children's beliefs that the events they witnessed were real magic(as opposed to fooling) also decreased with age: Of the 156 timesin which children stated events they witnessed were magic, 71%,50%, and 18% of the follow-up responses given by 4-, 6-, and 8-year-olds, respectively, indicated they believed the magic in-volved was real.

The primary question of interest concerned which variableor variables best accounted for children's claims that physicalevents were magical. A preliminary single-factor ANOVA re-

2 Questions 4 and 5 were opened-ended questions and could not beassigned a numerical value. They were therefore excluded from the in-terview total score.

390 KATRINA E. PHELPS AND JACQUELINE D. WOOLLEY

Table 3Number of Children's Event Task Responses Across FourPhysical Explanation and Magical ClaimContingency Groupings

Age group

Response

Correct physical explanationClaim of magicNo claim of magic

No physical explanationClaim of magicNo claim of magic

4 years

829

7417

6 years

452

4824

8 years

192

2114

Note. There were a total of 128 responses for each age group, as 16children at each age responded to eight event task items.

vealed no effects of sex on claims of magic. To assess the relativeexplanatory power of the four interrelated variables of age,magic interview total, accurate predictions, and correct physi-cal explanations, we subjected children's overall claims ofmagic to a multiple linear regression analysis. When enteredalone, each of the covariates reached a level of statistical sig-nificance; however, when analyzed jointly, the strong corre-lations between the variables allowed the single covariate of cor-rect physical explanations to account for a majority of the vari-ance in children's responses of magic to events.3 Thus, of thesefour predictors, only the availability of correct physical expla-nations for events accounted for a significant portion of the vari-ance in children's claims of magic {R2 = .61,/? < .0001).4

Further evidence of the influence of physical explanations onchildren's claims of magic accrues on inspection of the patternof contingencies within individual subjects' responses. Chil-dren's responses to each event were categorized into one of fourcontingency groupings: (a) they had a physical explanation andclaimed the event was magic; (b) they had a physical explana-tion and did not claim magic; (c) they did not have a physicalexplanation and claimed magic; or (d) they did not have a phys-ical explanation and did not claim magic. The number of re-sponses of each type across the three age groups is presented inTable 3.

Overall, only 3% of children's responses were of the first type;that is, they had a physical explanation for an event and claimedit was magic. In contrast, 82% of children's responses fell intothe second and third categories: Either children had a physicalexplanation and did not claim the event was magic, or they didnot have a physical explanation and did claim the event wasmagic. The percentages of responses across age groups withinthese two contingency categories revealed two developmentaltrends. As indicated in Table 3, responses consisting of a physi-cal explanation and no claim of magic increased with age, anda concomitant decrease was evident in the percentage of re-sponses involving no physical explanation and a claim of magic,X2( 1, N = 48) = 147.9, p < .0001.5 A closer examination of thefactors associated with children's claims of magic revealed that92% of magic claims were made when children had no explana-tion for an event; 84% of these involved events that both vio-

lated the predictions children originally made and eluded sub-sequent explanation. Therefore, although children of differentages varied in their knowledge of physical mechanisms and intheir overall willingness to evoke magic, the availability of phys-ical explanations was the primary determinant of whether chil-dren of all ages claimed events were magical. In addition, theviolation of children's expectations played a role in children'sclaims of magic.

Discussion

The combined results of the interview and the event tasksreveal both developmental similarities and differences in chil-dren's magical beliefs. Age differences were found for children'sdefinitions of magic and their beliefs about the contexts inwhich magic can occur. Important similarities, however, ap-peared in children's assessments of which events qualified asmagical; children of all ages most often evoked magic to explainevents that violated their expectations and for which they lackedadequate physical explanations.

The magical beliefs interview revealed developmentalchanges in children's conceptions of different types of magic.Nearly all of the children tested believed that both magiciansand fairies could do magic, and many of the older children wereable to provide examples of the kinds of feats these two figurescould perform. Children's responses indicated a growing aware-ness of magic in the form of tricks and a subsequent differenti-ation of real magic from trickery. This growing awareness is bestexemplified by children's elaborations and spontaneous com-ments. As one 6-year-old stated, "Magicians trick your eye, butfairies do it for real"; another claimed, "Fairies do like miracles,and magicians do like card tricks." An 8-year-old expanded onthis distinction by explaining, "Magicians can't make a houseappear right at the instant—they have to make it by doing mir-rors, and a fairy can make it appear just like that!" Evidence ofthis developing distinction was also apparent in the observeddecrease with age in children's assertions that a magician doesreal magic, and in the concurrent decrease in children's claimsthat the magic they purported to witness in the physical eventswas real magic.

Related differences were found in children's responses toquestions concerning whether the experimenter and the chil-dren themselves could do magic, and if magic could be learned.A majority of 8-year-olds believed all of these to be possible,

3 The correlations between several of the covariates entered into theregression equation were notable: age and interview score, r = .52; ageand correct physical explanations, r = .77; and accurate predictions andcorrect physical explanations, r = .63.

4 The portion of variance accounted for by children's physical expla-nations was measured by Type HI sums of squares (the sums of squaresattributed to a covariate when it is entered into the regression equationlast).

5 This chi-square analysis represents the difference in deviance be-tween the log-linear models fitted with and without the interaction ofphysical explanation and claims of magic (McCullagh & Nelder, 1989).It is given as an approximation as it does not take into account potentialsubject-to-subject variation.

MAGICAL EXPLANATIONS 391

indicating further children's growing understanding of the con-cept of magic as trickery. In contrast, only one of the 4-year-oldsin the study mentioned tricks when describing different kindsof magic or explaining the task events. Rosengren et al. (in press,Study 3) similarly reported that only two of twenty 4- and 5-year-old children suggested that magicians used tricks or decep-tion to elicit surprising transformations. It appears that magic,in the early preschool years, is conceived of as a singularly realforce, and it is not until children begin to understand the notionof tricks that it takes on a dual nature.

In addition to revealing changes in the conceivable forms ofmagic, the interview data suggest that the contexts in whichmagical agents and objects operate change as children develop.Children shift from readily infusing the real world with magicto primarily relegating magic to a separate, nonreal domain.Many 4-year-old children alleged that fairies do magic in thereal world. One 4-year-old insisted that fairies were in the roomwith us doing their magic but they were really, really tiny so wecould not see them. Conversely, all of the 8-year-old childrendeclared that fairies only exist in stories or movies. Children'sbehavior in certain experimental settings also demonstratestheir increasing reluctance to grant credibility to magical forcesoperating in the real world. Recall Subbotsky's (in press) studyin which he read children a fairy tale about a girl who had amagic box that became permeable when magic words werechanted. When presented with a box identical to the one de-scribed in the story, children engaged in a variety of attempts toreplicate the magic performed in the fairy tale. However, thisseemingly magical behavior decreased significantly between theagesof4and6.

Despite these developmental differences in children's beliefsabout magical agents and objects, the findings from the eventtasks reveal an important similarity in all children's use ofmagic as an explanation for physical events. Children's willing-ness to consider an event magical appears to be related both totheir understanding of a number of general physical principlesnormally operative in the world and to their knowledge of spe-cific causal mechanisms. This is in accord with the observedresponse patterns of children in recent studies. Recall thatJohnson and Harris (in press) presented children with pairs ofordinary and extraordinary events (e.g., a picture being drawnand one appearing spontaneously) and found that children asyoung as 4 years of age appropriately labeled the latter as magi-cal. Similarly, in Rosengren et al.'s (in press) study of children'sknowledge of principles of biological change, preschool chil-dren were highly adept at distinguishing between normal trans-formations and the kinds of transformations that require magic.Although neither of these studies was designed to addresswhether children's claims of magic are based on the violation ofexpectations and the availability of physical explanations, theresults suggest that the events and transformations childrenclaimed were magical were precisely those they found to be un-usual and for which they could not produce a satisfactory phys-ical or biological mechanism.

Whereas these previous studies were only suggestive of thisresponse contingency, the present study was specifically de-signed as a test of the determinants of children's beliefs in mag-ical outcomes. Accordingly, children were asked about real,

physical events demonstrated to them, as opposed to hypothet-ical events or events in stories. This was done to assure thatchildren's responses were based on their perceptions of magicin the real world, rather than a pretend or storybook context. Inaddition, a broad range of causal concepts was introduced sochildren of each age would experience both familiar and unfa-miliar events. As all the events defied natural physical principlesabout which children of all ages had formed expectations, itwould not have been unreasonable for children to claim that allthe events were magic. This outcome may have been especiallyplausible given that children were specifically asked, for eachevent, whether they thought the occurrence was magic. How-ever, children did not respond in such a uniform manner; sig-nificant differences in children's claims of magic were found,and the factor that most strongly accounted for these differenceswas the availability of physical explanations for events. Theseresults suggest that as children's knowledge of the causal mech-anisms underlying specific events increases, their use of magicalexplanations for those events decreases.

Several children seemed especially aware of this correspon-dence. When asked if a magnifying glass that made a picture ofa kitten appear larger was magic, one 8-year-old responded, "Ifpeople know that it's a magnifying glass, then they won't thinkit's magic." Similarly, regarding the hand boiler that made blueliquid rise, another child noted, "If you didn't know the heat ofyour hand pushes it up, it would look like magic because usuallywater goes down." On several occasions children discovered theunderlying causal mechanism of an event after they had alreadyclaimed that the event was magic. In one instance, a 6-year-oldgirl was not aware of the repellent force of magnets, so whenshe saw two magnets move away from each other without anyapparent cause, she was amazed and exclaimed that it must bemagic. When the magnets were accidentally flipped, however,they immediately stuck together and she realized the event wascaused by magnetism rather than magic: "Oh, I get it. They'remagnets." Chandler and Lalonde (in press) likewise observedthat children can "manage to evoke genuinely magical explana-tions without necessarily abandoning their search for some realworld explanation."

There is also some evidence indicating that a certain level ofconceptual understanding may be necessary for sophisticatedcausal explanations to be accepted by children. Koutsourias(1984) read two sets of stories concerning the disappearanceof water (i.e., the concept of evaporation) to 4- and 5-year-oldchildren. The first set of stories contained no explicit, realisticexplanation of why evaporation occurs; in the second set of sto-ries, such an explanation was provided by one of the story char-acters. After each set of stories, subjects were instructed tochoose either a nonnaturalistic explanation (e.g., children'swishes) or a naturalistic explanation (e.g., heater, sun) for theevent in the story. Koutsourias predicted that after hearing arealistic explanation, children would be less likely to select anonnaturalistic explanation. Contrary to his expectations, how-ever, children did not change their reasoning after receiving in-struction on the process of evaporation. Instead, most subjectsconsistently responded with one or the other of the explanationsacross stories, indicating they did not fully understand the in-formation provided.

392 KATRINA E. PHELPS AND JACQUELINE D. WOOLLEY

In the present study, conceptual limitations of this sort wereevident in the few responses of younger children who had aphysical explanation but who still claimed an event was magic.This occurred most frequently for the events illustrating theeffects of magnetic forces. It seems plausible that children mightknow the word for magnets or magnetism without fully under-standing the force that causes magnets to behave in the way theydo. Indeed, one child defended his claim of magic after he pro-claimed the disks were magnets by admitting, "It's magic 'causeI don't know how it does that." Another child understood thatthe heat of her hand was what caused a black pad to changecolors, but she had no idea what kind of surface would react inthat way, and therefore reported it could be magic.

There are a number of potential relationships between chil-dren's beliefs about magic and their use of magic to explainphysical events. Recall that, according to the interview, chil-dren's beliefs in supernatural forces and beings appears to de-cline between the ages of 4 and 8. Yet children of all ages stillevoked magic to explain otherwise inexplicable physical events.Regarding this latter application of magic in the event tasks,there are at least three possibilities to describe how children areusing the term magic; it may be the case that (a) children do notactually believe the things they see are magic, but they use thisterm simply as a placeholder to label events that are mysterious;(b) children are just saying the events are magic to play alongwith what they perceive to be a game context; or (c) children sayand believe the events they witness may be "really magic" in thesupernatural sort of sense. The findings of the present study,while attempting to differentiate between children's beliefsabout trick magic and real magic, do not systematically addresswhich of these more subtle descriptions most accurately char-acterizes children's responses. However, the true surprise(bugged eyes, raised eyebrows, and dropped jaws) and reluctantadmittance on the part of some children that the things theysaw "must be magic" may be taken as anecdotal evidence insupport of something closest to the third state of affairs. At leastit appears less likely that the term magic merely serves as a vac-uous label children learn to apply in situations in which theylack alternative explanations for events. In addition, it is un-likely that children answered on the basis of a perceived "playmode" (R. Gelman, Spelke, & Meek, 1983), as their applicationof magical explanations was neither universal nor randomwithin the experimental session. On the contrary, children judi-ciously allocated only certain occurrences to the realm ofmagic. Thus, although the first possibility suggests it is impor-tant not to assume that children's use of magic as an explana-tory device necessarily implies they believe in real magic, it isequally important to note that children's use of magic in thispragmatic way does not necessarily negate that magic is a con-ceptually meaningful category to them. The results of the pres-ent study support the contention that children maintain differ-ent sets of beliefs about natural and supernatural causal princi-ples, and they systematically apply explanations on the basis ofthe latter conceptions only when specific criteria are satisfied.

These criteria appear to be twofold; in this study, children ofall ages most often claimed events were magic when the eventsviolated their previously stated expectations as well as whenthey lacked an adequate explanation for the outcomes. This

pairing of violated expectations and lack of physical explana-tions emerges as especially diagnostic when contrasted with sev-eral other state of affairs young children may frequently en-counter. In certain situations young children may have no ex-planation for an event, but it may fall perfectly in line with theireveryday expectations. One example of this would be a lightswitch causing a light to turn on.6 Although young children (andmany adults for that matter) may not be able to provide an ac-curate explanation involving electricity and circuits, they wouldprobably not claim this event was magic. Certainly there arenumerous occurrences children view as natural or ordinaryrather than supernatural or extraordinary even though they donot have readily available explanations for them. E. V. Subbot-sky (personal communication, February 9, 1993) referencedthis distinction as the difference between events that are unex-plained and events that are unexplainable. Whereas childrenmay believe that adults or experts can understand the formerclass of events, they may be more likely to think the latter kindsof events are inexplicable to all and therefore conceive of themas magic. One other alternative to consider includes the case inwhich an event falls outside the realm of children's expectationsrather than violating their specific predictions. For instance,consider telling a child about the planets moving around thesun, or showing a child a drop of gasoline falling into water.Although these events may seem somewhat mysterious toadults, we may not expect children to be surprised by their oc-currence, as these events presumably do not violate any beliefschildren hold regarding planetary motion or liquid mixture.Precisely because these events do not violate any preconcep-tions, we would not expect children to evoke magic to explainthem.

The findings from the present study support the hypothesisthat children will use magic to explain events that (a) violatetheir expectations and (b) fail to be otherwise explained. Itstands to reason that providing children with additional infor-mation to alter their predictions or supplying them with accept-able physical explanations for events would limit their use ofmagic as an explanation for events. Further research will beneeded to evaluate the strength of these claims and to determinemore precisely the respective roles of accuracy of predictionsand availability of physical explanations in children's magicalversus nonmagical explanations of events.

6 We thank Karl Rosengren for bringing this example to our atten-tion.

References

Berzonsky, M. D. (1971). The role of familiarity in children's explana-tions of physical causality. Child Development, 42, 705-715.

Barbieri, M. S., Colavua, E, & Scheuer, N. (1990). The beginning ofthe explaining capacity. In G. Conti-Ramsden & C. E. Snow (Eds.),Children's language (Vol. 7, pp. 245-271). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bullock, M., Gelman, R., & Baillargeon, R. (1982). The developmentof causal reasoning. In W. E. Friedman (Ed.), The developmental psy-chology of time (pp. 209-254). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Callanan, M. A., & Oakes, L. M. (1992). Preschoolers' questions andparents' explanations: Causal thinking in everyday activity. CognitiveDevelopment, 7, 213-233.

MAGICAL EXPLANATIONS 393

Carey, S. (1985). Conceptual change in childhood. Cambridge, MA:Bradford Books.

Chandler, M. J., & Lalonde, C. E. (in press). Surprising, miraculous, andmagical turns of events. British Journal of Developmental Psychology.

Donaldson, M. L. (1986). Children's explanations: A psycholinguisticstudy. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Dunn, J. (1988). The beginnings of social understanding. Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press.

Gelman, R., Spelke, E. S., & Meek, E. (1983). What preschoolers know-about animate and inanimate objects. In D. R. Rogers & J. A. Slo-boda (Eds.), The acquisition of symbolic skills (pp. 297-326). New\hrk: Plenum.

Gelman, S. A., & Kremer, K. E. (1991). Understanding natural cause:Children's explanations of how objects and their properties originate.Child Development, 62, 396-414.

Harris, P. L., Brown, E., Marriott, C, Whittall, S., & Harmer, S. (1991).Monsters, ghosts and witches: Testing the limits of the fantasy-realitydistinction in young children. British Journal of Developmental Psy-chology, 9, 105-123.

Hood, L., & Bloom, L. (1979). What, when and how about why: Alongitudinal study of the early expression of causality. Monographs ofthe Society for Research in Child Development, -W(No. 181). Chicago:University of Chicago Press.

Horton, R. (1979). Ritual man in Africa. In W. A. Lessa & E. Z. Vogt(Eds.), Reader in comparative religion (pp. 347-358). New York:Harper & Row.

Johnson, C, & Harris, P. L. (1991, July). Young children's views of mag-ical events and beings. Paper presented at the Eleventh Biennial Meet-ing of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Develop-ment, Minneapolis, MN.

Johnson, C, & Harris, P. L. (in press). Magic: Special but not excluded.British Journal of Developmental Psychology.

Keil, F. C. (1989). Concepts, kinds, and cognitive development. Cam-bridge, MA: MIT Press.

Koutsourias, H. (1984). Inhibiting magical thought through stories.Child Study Journal, 14, 227-236.

McCullagh, P., & Nelder, J. A. (1989). Generalized linear models. Lon-don: Chapman & Hall.

Nass, M. L. (1956). The effects of three variables on children's conceptsof physical causality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 53,191-196.

Piaget, J. (1929). The child's conception of the world. London: KeganPaul, Trench, & Trubner.

Piaget, J. (1930). The child's conception of physical causality. London:Kegan Paul, Trench, & Trubner.

Reyna, V. F. (1985). Figure and fantasy in children's language. In M.Pressley & C. Brainerd (Eds.), Cognitive learning and memory in chil-dren: Progress in cognitive development research (pp. 143-179). NewYork: Springer-Verlag.

Rosengren, K. S., Kalish, C. W., Hickling, A. K., & Gelman, S. A. (inpress). Exploring the relation between preschool children's magicalbeliefs and causal thinking. British Journal of Developmental Psychol-ogy

Subbotsky, E. V. (1985). Preschool children's perception of unusualphenomena. Soviet Psychology, 23, 91 -114.

Subbotsky, E. V. (in press). Early rationality and magical thinking inpreschoolers: Space and time. British Journal of Developmental Psy-chology.

Webster's New International Dictionary of the English Language.(1959). (2nd ed., unabridged). Springfield, MA: G. & C. Merriam.

Wellman, H. M., & Gelman, S. A. (1992). Cognitive development:Foundational theories of core domains. Annual Review of Psychology,43, 337-375.

Winner, E., Rosenstiel, A. K., & Gardner, H. (1976). The developmentof metaphoric understanding. Developmental Psychology, 12, 289-297.

(Appendixes follow on next page)

394 KATRINA E. PHELPS AND JACQUELINE D. WOOLLEY

Appendix A

Magical Beliefs Interview

1. Do you believe in magic?

Magician and Fairy Magic

2. Can a magician do magic?3. Can a fairy do magic?4. What kind of magic does a magician do?5. What kind of magic does a fairy do?6. Do magicians and fairies do the same kind of magic, or different

kinds of magic?

7. Does a magician do magic in the real world, or just in stories?8. Does a fairy do magic in the real world, or just in stories?9. Does a magician do real magic, or is a magician just fooling you?

10. Does a fairy do real magic, or is a fairy just fooling you?

Self and Other Magic

11. Do you think I can do magic?12. Do you think you can do magic?13. Do you think someone could learn to do magic?

Appendix B

Task Items and Events

Ball pipe: A pipe with a lightweight ball resting in the cup at the endof it. When air is blown into the pipe, the ball rises up.

Question (Q): "If I blow in this pipe, will the ball go up in the air, orwill the ball stay sitting in the cup, like it is now?"

Magnifier: A clear jar with a magnifying glass in the lid that enlargesa picture of a kitten placed in the jar.

Q: "If I put this picture of a kitten in this box, will the kitten lookbigger, or will the kitten look the same size as it does now?"

Fickle foam: A heat-sensitive black pad that changes colors whenwarmed by a person's hand.

Q: "If I put my hand on this black pad, when I take my hand off againwill the pad still be black, like it is now, or will the places where I touchit look different?"

Hand boiler: A glass container with bulbs at the top and the bottom,and a tube connecting the two. Blue liquid in the bottom of the glassrises to the top when it is warmed by the heat of a person's hand.

Q: "If I put this glass in my hand, will the liquid go up to the top, orwill the liquid stay on the bottom, like it is now?"

Magnetic disks: Two unattached magnetic disks that repel one an-other and thus appear to "scoot" across the table of their own accord.

Q: "If I want to push one of these disks with the other one, will theyhave to touch for it to move, or can it move by itself?"

Magnetic pole: A short pole with a magnetic ring on the bottom thatrepels a second ring dropped from the top, causing the ring to bounceback to the top of the pole.

Q: "If I drop this ring on the pole like I did the first one, will it falldown to the bottom of the pole, or will it stay on top?"

Die trick: A tiny die placed in a dish with a false lid that drops downto expose a large die when it is lifted.

Q: "If I cover this die up, and then look at it again, will it still be small,like it is now, or will it be different?"

Quarter bank: A box with mirrors creating the illusion of a fully-visible inside that makes a quarter appear to vanish when it is droppedinto a secret compartment.

Q: "If you look inside while I drop this quarter into this box, will yousee the quarter fall in, or will you not see the quarter?"

Received January 17, 1993Revision received July 21, 1993

Accepted August 2, 1993 •