The 2nd Line of the Duenos Inscription

Transcript of The 2nd Line of the Duenos Inscription

Si ringraziano:la Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Torinoil Lions Club Villanova d’Asti

© 2011Copyright by Edizioni dell’Orso s.r.l.via Rattazzi, 47 15121 AlessandriaTel. 0131.252349 Fax 0131.257567e-mail: [email protected]: //www.ediorso.it

Realizzazione informatica di Arun Maltese ([email protected])

È vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale, non autorizzata, con qualsiasi mezzo effettuata,compresa la fotocopia, anche a uso interno e didattico. L’illecito sarà penalmente perse-guibile a norma dell’art. 171 della Legge n. 633 del 22.04.1941

ISBN 978-88-6274-319-8

Nell’autunno del 2006 Gianni Abbate, Mario Enrietti, Renato Gendre, MarioNegri hanno costituito l’Associazione Culturale ‘Alessandria’, con sede presso ilLiceo Classico ‘Balbo’ di Casale Monferrato (AL).La pubblicazione di questa rivista è uno degli scopi statutari dell’Associazione

Atti del Convegno Internazionale

Le lingue dell’Italia anticaIscrizioni, testi, grammatica

Die Sprachen AltitaliensInschriften, Texte, Grammatik

In memoriam Helmut Rix (1926-2004)

a cura di Giovanna Rocca

7-8 marzo 2011

Libera Università di Lingue e Comunicazione

IULM

Milano

presentazione

Bibliografia degli scritti di Helmut Rix

RICORDI DI HELMUT RIX

Gerhard Meiser In memoriam Helmut Rix

Aldo Luigi prosdocimi In memoriam…

Jürgen Untermann La mia amicizia con Helmut Rix

RELAzIONI

Luciano Agostiniani pertinentivo

Michael H. Crawford Tribunes in Italy

Emmanuel Dupraz Osservazioni sulla coesione te -stuale nei rituali umbri: il casodelle Tavole I e IIa

Heiner Eichner Anmerkungen zum Etruskischenin memoriam Helmut Rix

Joseph F. Eska –Rex E. Wallace Script and language at ancient

Voltino

José Luis García Ramón Secondary yod, palatalisation,syncope, initial stress as relatedfeatures: Sabellic and Thessalian

p. VII

XI

1

3

7

11

17

45

49

67

93

115

462 INDICE

Olav Hackstein persistenz bei präfix- und parti-kelverben im Lateinischen: ital.*per ‚ver-‘ und *ped ‚zugrunde‘,lat. periūrāre und peiierāre ‚ei-nen Meineid schwören‘

Jón A. Harðarson The 2nd Line of the Duenos In-scription

Rosemarie Lühr „prägnante Konstruktionen“ inden klassischen Sprachen

Daniele F. Maras Skerfs

Maria pia Marchese Un problema di lettura e di sin-tassi nel Cippo Abellano

Vincent Martzloff Spuren des Gerundivsuffixes imSüdpikenischen: qdufeniúí (pen -na S. Andrea), amcenas (Bel -monte)

Kanehiro Nishimura A phonological Factor in Mārs’Lexical Genealogy

Dariusz piwowarczyk The Oscan appelluneí and thegraphemic-phonemic correspon-dences

paolo poccetti Strutture della coordinazione inetrusco

Luca Rigobianco Rix 1979 (1981): etr. uni < lat.*Iūnī. Tracce della presenza dii.e. *-j(e/o)H2 in etrusco

Timo Sironen La ricerca sugli imprestiti grecie latini nella lingua osca. Lostato della ricerca

Elena Triantafillis Ancóra sull’iscrizione ‘ernica’Rix He 2

137

153

165

185

199

209

233

247

253

289

303

311331

463INDICE

Brent Vine Umbrian disleralinsust

Michael Weiss Observations on the prehistoryof Lat. augur

Andreas Willi Revisiting the Etruscan verb

SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO IN STORIA LINGUISTICA DELMEDITERRANEO ANTICO

Manuela Anelli Una glossa italica?

paolo Cagnazzo Rix 1957: ‘Sabini – Sabelli –Samnium’ e la prospettiva delle‘medie aspirate’. Uno sguardoretrospettivo

Laura Montagnaro Venetico termon. Lessico e isti-tuzionalità nella terminologiadella confinazione

Giulia Sarullo Il Cippo del Foro. prima e dopoGoidanich (1943): cronaca perun bilancio storiografico

INDIRIzzI DEGLI AUTORI

345

365

387

403

419

439

453

1. Introduction

The Archaic Latin Duenos Inscription (CIL I2 4) most probably datesfrom the 1st half of the 6th century BC.1 The text is inscribed on the sidesof a kernos with three small globular vases. In all likelihood it oncebelonged to the votive deposit of a temple situated on the Quirinal Hill inRome. The deposit was found near the Church of San Vitale on the ViaNazionale. It may be considered certain that the kernos was an object ofutility, in which three perfumes or ointments could be kept.

The inscription is written from right to left in three lines without wordspaces. The text has turned out to be rather difficult to translate, due to bothepigraphic and linguistic problems. Nevertheless, one can say that the 1stand 3rd lines have been convincingly interpreted. But the 2nd line still re-sists a widely accepted interpretation. The aim of this paper is to improveour understanding of the second line as well as that of the whole inscription.

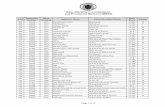

The following illustration of the inscription was published in Hermes16 (1881):

Jón Axel Harðarson

THE 2ND LINE OF THE DUENOS INSCRIpTION

Alessandria 5 – 2011, pp. 153-163.

1 I thank the participants of the conference for helpful discussions. I would alsolike to express my thanks to Reiner Lipp for valuable comments on an earlier versionof this paper.

������������ ��

������������������������� ��� ��������

���������������

���������������������������� ������������ !�"� �����##�$���� ����"������ ������

�������%���������$�&�������������� ��� ���#���������� ��� �����'���� �(���������� "���

)��#����* � ����������'����������������#����)����������*���*������ ���������"����

��������������+��������������,�"����������� ���( �������������������������-��

.���� ��������.��/0������ ��� �"$�#����� ������������������ ����'���� �( ���

�#1�������������$2����(����������������"� ��������"��� �������#��'����

������ ���������� �(����������"���)������������������������ �(�������(���� ��� ������

���� �� � ������ ���� � �� �#� � ����� ���������� � �� � ��� ���2 ���� � �� �#��� ����)����� ����

���)�� �������#��" ��/�*������� 2�������� $���������� �����3������� ��*��#����

���*�����)�$��������������&���������������� ������� � � ��(����$������������������������

�����"������� ������� �����"���*����������� �����)�������� ����������� �(���� �

�����������(������� ���������

���������(��)����� ���������������� ���������( ���#�� ��������������%���44�!5

������ ���������������� ��63

�5 �7.8-���8�.7-+7�98�9����/8��8�8/�7�7-9�-.�,�7-�8�

�5 �-�8�/7�-�7:8�7��8-���:���,�.7�-

35 �.8/7-98�;8�8�8/9�/798�/79�.8/7�/898�9��7-���7�

�������'�������������� ��������������������������������� �� ��� ����(������ ����'���������� �

"$����' ����,���������������*��#�����""��� �������������*�� ���������� �������

154 J. A. HARðARSON

2. Transcription of lines 1-3

1: IOVESATDEIVOSQOIMEDMITATNEITEDENDOCOSMISVIRCOSIED2: ASTEDNOISIOpETOITESIAIpACARIVOIS3: DVENOSMEDFECEDENMANOMEINOMDVENOINEMEDMALOSTATOD

3. Interpretation and translation of lines 1 and 3

1: Iouezāt deiuōs, kwoi mēd mitāt: Nei tēd endō kozmis u irgō siēd‘The person who gives me swears by the gods: If the girl should notbe kind / friendly towards you …’

3: Duenos mēd fēked en māno(m) meinom du enōi. Nē mēd malo(s) stātōd(or malos tātōd)‘A good man made me as a fine gift for a good man. Let an evil per-son not steal me!’

For the form MITAT see MEISER 1998:4, 8, Vine 1999:294-298, LIV2

430; for EN()MANOMEINOM see VINE 1999:298-302; for MALOSTATOD seeRIX 1985 (esp. pp. 205-207, 210f.) and EICHNER 1988-1990:216, 238.

4. Recent proposals on the interpretation of the 2nd line

According to HARTMANN (2005:114 w. ref.), more than 50 proposalshad been made on the interpretation of the inscription up to 1960. It isbeyond the scope of this paper to undertake a review of the older interpre-tations of the 2nd line. Here we will confine ourselves to only two recentproposals made by Heiner Eichner and Eva Tichy.

(1)Eichner’s interpretation (1988-1990):as(t) tḗd noisi ó(p)petóit, esi/iái pācā rĭuóis (iambic reading)‘[wenn dir die Maid …] Nicht in die Arme fliegt, / Versöhn’ ihr Herzdurch Duft!’

The metric form of the translation reduces its precision. In the discus-sion of the single words Eichner translates the instrumental ablativeRIVOIS more exactly as ‘durch [Duft-]Ströme, [Duft-]Schwaden’ (p. 214).

For the history of the reading AS(T) TED NOISI see EICHNER pp. 213,232f. The reading pACA RIVOIS was suggested by STEINBAUER (cf.1989:34-35) („paca rivois ‘schaffe Frieden / besänftige durch dieGüsse’).

155

According to Eichner, the form *op-petoit (from op-petō, here withthe meaning ‘entgegenstreben, in die Arme fliegen’) is a relic of the origi-nal formation of the thematic optative in proto-Italic. Two objections canbe raised against this interpretation. (1) Neither the Italic nor the Celticlanguages show any remnants of the pIE thematic optative characterizedby the suffix cluster *-o-ih1-. (2) As the form SIED in the first line of ourinscription shows, the 3rd sg. pres. opt. took the secondary ending -d (notthe primary ending -t < pIE *-ti) in Early Latin.

The interpretation of ESIAI pACA RIVOIS as ‘Versöhn’ ihr Herz durchDuft!’ faces the problem that we don’t expect the dative case of theanaphoric pronoun. The Latin verb pācāre, of course, takes the directobject in the accusative, cf. eam paco ‘I soothe her’. The use of a dativeof personal interest with this verb would only be possible in connectionwith the accusative, but not without it. So, e.g., we could say ei cor paco‘I soothe her heart’, but not *ei paco, with ellipsis of the direct object.2

In order to avoid a „Hinkjambus“ at the end of the line Eichner iscompelled to assume that the Latin word rīuus ‘stream’ once had a by-form with a short i (*rĭuos), of which there is no further evidence. Hederives this formation from an old „Komprehensivplural“ with zero gradeof the root and a stressed suffix.

(2)Tichy’s interpretation (2002):as(t) tēd n’oissi opēt, oit esiāi, pākā rīu ois‘und trifft sie nicht die Wahl, dich mitzunehmen, nimm (das) für siemit, befriedige sie in Strömen!’

In her interpretation, Tichy draws on my identification of the verbalform opēt with the meaning ‘optat’ (see below).

Tichy explains the forms oissi and oit as infinitive and 2nd sg. imp. ofan active root present *oit- ‘to take sth./sb. along’, which she, togetherwith Gk. oi[sw, -omai ‘I will fetch, take along’, traces back to pIE *h3eit-‘to take along’. According to her, the Greek verb continues a voluntative*h3éit-se/o-. This form may have its counterpart in CLuw. hizza(i)- ‘to

2 The same would, of course, apply to a nonce word *pākō based on an adjective*pākātos ‘peaceful, pacified’, which was reinterpreted as a past passive participle.Such a back-formation could only have been transitive (with accusative rection). Butthere is no reason to assume that the verb pācō did not exist in the 6th century BC,only because it is elsewhere first attested in Cicero in its finite forms (cf. STEIN -BAUER 1989:34f.). plautus has only the form pācātus.

THE 2ND LINE OF THE DUENOS INSCRIPTION

156 J. A. HARðARSON

fetch’ (cf. MELCHERT 2007). Tichy identifies the forms oissi and oit withthe Latin verb ūtor ‘I use’ and argues that the meaning ‘to use’ may havedeveloped from ‘to take along in one’s own interest’ (‘im eigenenInteresse mitnehmen’).

As DUpRAz 2004 has pointed out, this explanation of OISI and OITinvolves some problems. It is clear from the Italic evidence that the root*oit- had the meaning ‘to use’, cf. pael. past ptc. abl. sg. f. oisa aetate‘usā aetate’ (Ve 214/pg 10), Osc. úíttiuf f. ‘ūsus’ (< *oit-iōn-s). It wouldbe difficult to warrant the assumption that in the 6th c. BC the Latin ver-bal root *oit- still preserved the meaning ‘to take along’ in the activevoice, wheras the middle voice had developed the meaning ‘to use’.

To this observation the following may be added: (1) Since it is clearfrom the evidence that the Italic root *oit- had the meaning ‘to use’,which most probably developed in the middle voice, we expect that theverb was a deponent already in proto-Italic. (2) There is no (further) evi-dence for a root present *h3eit- ‘to fetch, take along’. (3) Assuming thiswas in fact the original meaning of the root we would rather expect it tohave formed a root aorist. (4) If the negative ne were indeed representedin the text we would not expect the elision of e, especially if we bear inmind how carefully the text is written. (5) Moreover, the position of thenegative ne would be unexpected. An unmarked word order would havebeen *as(t) tēd oissi ne opēt. (6) The interpretation ‘and if she does notchoose to take you along, then take (it) along for her’ doesn’t seem to fitvery well in the context of the inscription.

Dupraz (ibid.) has proposed a correction to Tichy’s translation of the2nd line while retaining her word analysis. He translates the second lineas follows: ‘si elle ne souhaite pas faire usage (OISI) de toi [comme époux? comme amant ?], fais usage (OIT) pour elle [de ce vase], apaise[-la]avec des flots [de parfum ?]’. This interpretation is indeed similar to myown proposal, but, with the above mentioned in mind, the word analysismust seem implausible.

5. A new interpretation of the 2nd line3

as(t) tēd noi si (or noisi) opēt oiteziiai, pākā rīuois‘and if she does not want to be intimate with you (or enjoy your love), thensoothe (her) with the streams (of fragrance)!’

3 Indeed, this proposal of mine dates back to the summer term of 1994.

157

Ad noi si (or noisi):noi is an ablaut variant of nei (see line 1), used in connection with the

particle si (for this explanation see EICHNER 1988-90:213, 233f. w. ref.).It is also attested in Umbr. nosue ‘if not’ < *noi suai (cf. Osc. nei suae).The variants nei and noi are reminiscent of the ablaut forms sei in Lat.SEI, sī, sīue etc. and *soi in Umbr. sopir ‘siquis’ < *soipis < *soi kwis (cf.EICHNER loc. cit. 234).

For the forms *nei and *noi as well as *sei, *soi and *si cf. further:pIE *sei, *soi, *si: OLat. SEI, SEIC, Cl. Lat. sī ‘if’, orig. ‘so’ (pl. si dis

placet), sīc ‘so, thus’ < *sei-ḱe : pGmc. *sai ‘ecce’ (Goth. sai, OHG sē,cf. Brugmann 1904:28) < *soi, pGmc. *sa-sai ‘this’ (> pNc. *sa-sē >Run. ON sasi, cf. Klingenschmitt 1987:185) < Tp *so-soi : *si in pIE*sio-/siio- (Skt. syá- ‘that’, pGmc. nom. sg. f. *sijō (≈ Skt. syā) > OE sīo‘that’, OS, OHG siu ‘she’), Gaul. acc. sg. n. sosin ‘this’, and probablyalso in OE ðēs ‘this’, etc., and OS nom. sg. f., instr. sg. n., nom. acc. pl.n. thius, i.e. with -s < pGmc. *-si. – From the stem *se/o-.

pIE *tei, *toi, *ti: Dor. tei'de ‘here’ (cf. BRUGMANN 1904:29): toiv (atthe beginning of a phrase), toi; gavr, toigavr ‘so then, therefore’, toivnun‘therefore, accordingly’ (cf. CHANTRAINE 1968:1123) : *ti in germ. *þi-(late pNc. acc. sg. m. þin (Roes), OGutn. þina ‘this’, OS nom. acc. sg. n.thit, MLG ditte, OHG diz/dizzi < WGmc. *þitti < *þit-þi(t), cf.Klingenschmitt 1987:183, 187), and in pIE *tio-/tiio- (Skt. tyá- ‘that’,pGmc. *þija-, cf. OS nom. sg. f. = nom. acc. pl. n. thiu, OHG diu <pGmc. *þijō). – From the stem *te/o-.

pIE *ḱei, *koi, *ḱi: Gk. kei', ejkei' ‘there’ : Ogam-Ir. COI ‘here’ : Lat.ci-s ‘on this side’. – From the stem *ḱe/o-.

pIE *ghei, *ghoi, *ghi: OLat. HEIC (CIL I2 1211), Lat. hīc, Fal. HEC,HE, FE ‘here’ < *ghei(ḱe) : OLat. HOI ‘here’ (CIL I2 2658, 6th c. BC) <*ghoi (cf. MEISER 1998:4, 162) : Skt. hí, Av. zī, Gk. naiv-ci ‘surely,indeed’ < *ghi. – From the stem *ghe/o-.

As BROCK (1897:171-179) has demonstrated, the original measure ofnisi in plautus is nīsī . I have picked out four of the 15 examples cited byhim:

Mos. 4, 3, 14 Haud póstulo édepol. Vérum crás, nīsī priús (iamb. sen.)4

4 Note that if the line ends in a iambic word the thesis of the 5th foot cannot beformed by a short syllable (see e.g. CRUSIUS 1992:64). Exceptions from this rule donot apply to the quoted line.

THE 2ND LINE OF THE DUENOS INSCRIPTION

158 J. A. HARðARSON

per. 2, 2, 52 Séd ego césso, máne. Molésta es. Érgo quóque, nīsī sció (troch.sept.)5

Amp. 1, 1, 128 nīsi item únam, uérberátus quám pepéndi pérpetém (troch. sept.)Tru. 2, 5, 16 mále quod múlier fácere incépit, nīsi effícere pérpetrát (troch. sept.)

On the assumption that the univerbation of noi and si took place afternoi had changed to nei the following development can be postulated forthe plautine form nīsī as well as for Cl. Lat. nĭsĭ: noi si > *nei si / *nei sei(due to the influence of sei) > *nẹ si / *nẹ sẹ > plautine *nẹsi (?) (thenuniverbation after the change of i to e in final position) / *nẹsẹ (writtennisi in the later transmission of the texts) > *nẹsi / *nẹsī (shortening by„Tonanschluss“, cf. Brugmann 1909:83, who derives nisī from *neisei,and compares sĭ-quidem, quŏ-que, etc.) > nisi, nisī (> nisi: Iambic short-ening).

Ad opēt:This verb most probably has its counterpart in Umbr. 3rd sg. imp. II

upetu from /opẹ-/ ‘to choose’ (cf. LIV2 299). The form opēt is a 3rd sg.pres. ind. from *opēzi ‘to choose, wish, desire’, which is best explainedas an iterative *h3op-éie/o- from the root *h3ep- ‘to choose’ (attested inLat. optāre < freq. *opetā-, which was formed on the basis of the past ptc.*opeto- = Umbr. gen. sg. n. opeter). This analysis, which I proposed in1994 (see fn. 3), has been adopted in LIV/LIV2.

The use of a present indicative (opēt) in the second condition asopposed to the present optative (siēd) in the first condition can beexplained in different ways: First, the same conditional particle is notused in both sentences, the former protasis being introduced by nei, thelatter by ast noi si. This difference provides more syntactic freedom.Second, we can observe that the syntactic rules of Old Latin are less strictthan those of Classical Latin.6 There are also certain divergences. plautus,e.g., regularly uses the present indicative with the particles nisi and ni inexpressions of threat (see Lindsay 1907:125), cf. Amp. 1, 1, 205 faciamego hodie te superbum, nisi hinc abis. In all periods the conception canshift in long sentences, which leads to syntactic incongruence. Third, the

5 If the line ends in a iambic word the thesis of the 6th foot has to be formed by along syllable (cf. preceding note) (see CRUSIUS 1992:73).

6 Note in this connection Lindsay’s (1907:1) general remark on the syntax ofplautus: „The rules of Latin Syntax which prevailed in the classical period […] sooften fail us in reading plautus, that plautine Latin at first sight appears to be regard-less of rules.“

159

verb opēt has itself a modal meaning. In Latin there are examples of theindicative use of the verb volo in conditional sentences, where one wouldrather expect the subjunctive, cf. pl. Tru. 4, 2, 38 si uolebas participari,auferres dimidium domum. Taking these things into account leads to theconclusion that the use of a present indicative in the 2nd line of ourinscription does not pose any problem.

Ad oiteziiai:This is the infinitive of the deponent verb *oit-e/o- ‘to use’, that also

has the transferred meaning ‘to enjoy the friendship of any one, to befamiliar or intimate with, to associate with a person’ (Lewis and Short),for which cf., e.g., Cic. Rosc. Am. 11, 27 quā (Caeciliā) pater usus eratplurimum, id. Fam. 1, 3, 1 Trebonio multos annos utor valde familiariter,id. Att. 16, 5, 3 Lucceius qui multum utitur Bruto.

The ending *-ziiai is a proto-Latin remodeling of *-điai < *-dhiai < pIE*-dhieh2i, loc. sg. f. from *-dhio- (< *-dhh1-io-).7 The same ending is prob-ably also preserved in Gk. -(s)sai, which functions as the ending of theinf. act. of the s-aorist. In the middle voice it was modified to -sqai underthe influence of the endings with -sq- (-sqe, -sqon, -sqhn, -sqw, -sqwn)(cf. Schwyzer 1959:809 and Sze me rényi 1996:324f.).8 For Greek middleinfinitives like fevresqai ‘to carry’ we can, therefore, postulate the follow-ing development: *bhére-dhieh2i > *bhére-dhiai > *phére-thiai > *phére-tsai> *phéressai → fevresqai. In the position after s the ending *-dhiai (<*-dhieh2i) most likely became Gk. -qai by regular sound change (cf. Rix1976:239 and Lipp 2009:107). Accordingly, Gk. h|sqai ‘to sit’ could be areflex of pIE *h1éh1s-dhieh2i.

9

In Sanskrit, Avestan, Oscan and Umbrian a parallel formation is con-

7 On this reconstruction cf. MEIER-BRÜGGER 2007:251. The element *-dhio-, firstreconstructed for the Indo-Iranian infinitives in *-dhiāi (see below), was linked withthe verbal root *dheh1- ‘to put, make’ by BARTHOLOMAE 1890:152 (who assumedthat the original meaning of Skt. bháradhyai was ‘Tragung zu tun’).

8 For the connection of the Gk. infinitive endings -(s)sai and -sqai with Skt.-dhyai cf. further RIX 1976:238f., SIHLER 1995:609f. and LIpp 2009:107f.

9 For Boeotian and Cretan we would, indeed, have expected intervocalic *dhi inthe sequence *Vdhiai to have yielded tt, cf. Boeot., Cret. mevtto" ‘medius’ as opposedto Ion., Att., Arc. mevso" and Heracl., Lesb. mevsso" < *médhios. But like the otherdialects, Boeotian and Cretan had the ending -sai in the inf. act. of the s-aorist (inBoeotian it changed to -sh through monophthongization). Although this might sug-gest polygenesis of the ending -sai it seems more plausible to assume Boeotian andCretan to have borrowed it from other dialects.

THE 2ND LINE OF THE DUENOS INSCRIPTION

160 J. A. HARðARSON

tinued, cf. Skt. bhára-dhyai ‘to carry’, sáca-dhyai ‘to follow’, OAv.vǝrǝziieidiiāi ‘to do, work, perform’ < dat. sg. f. *bhére-dhieh2ei,*sékwe-dhieh2ei, *ur ǵié-dhieh2ei or dat. sg. n. *bhére-dhiōi, *sékwe-dhiōi,*ur ǵié-dhiōi (cf. Lipp 2009:107f.), Osc. SAKRAFÍR ‘sacrari’, Umbr. pihafi,pihafei ‘piari’ < pSab. *-fiẹ+r < *-dhiē < pIE instr. sg. n. *-dhieh1 (cf.García-Ramón 1993 and Meiser 2003:56f.). As Sanskrit and Greek show,this use of an abstract noun in *-dhio- or *-dhieh2- originally was diathe-sis-indifferent.

The remodeling of *-điai to *-ziiai in proto-Latin was caused by theinfluence of the corresponding active infinitive in *-zi. The further deve -lopment within Latin was as follows: *-ziiai > *-riiei > *-riiẹ+r > -riēr,plautine -rir (mostly at the end of a line with the metric structure – ⏑ –)> -rier.10

We could also assume that the characteristic r of the medio-passivewas added to the infinitive ending at a time when it still had the diph-thong -ai , i.e. *-ziiai. In that case *-ziiai+r would have yielded *-riieir >*-riiẹr > -riēr, cf. *post-moiriiom > *poz-meiriiom > *pōmẹriiom > Lat.pōmērium ‘area behind the walls’ (cf. MEISER 1998:71 and WEISS2009:120). But as the remodeling of the imp. II shows (cf. OLat. obse-quitō, utuntō → obsequitor, utuntor), the addition of r can have takenplace relatively late.

The ending -rier is preserved in all conjugations except the third, wereit was replaced by -ier (dīcier etc.). This ending is most probably an inno-vation, which can be explained in the following way:

amārī : amārier = dīcī : x (= dīcier)The ending -rī < *-rei < *-zei can, in turn, continue a dat. sg. of an s-

stem (cf. Skt. jīváse ‘to live’) (so the traditional explanation). Alternative-ly, but less likely, it may be considered to have been formed after themodel of the competing ending -ei in the third conjugation (dīcī < *deiḱ-ei, originally dat. sg. of a root noun).11

10 Note that in all probability s was voiced in the position between vowel and i inproto-Latin, like in all other voiced environments. That means that the pLat. continu-ant of the pIE genitive ending *-osio was *-ozio (cf. pOpLIOSIO VALESIOSIO, 6th c.BC), which later changed to *-oiio (TITOIO, 3rd c. BC). As this example shows us,we cannot derive the Lat. medio-passive ending -rier from a preform *-ziai (+ r),since it would have undergone assimilation of the intervocalic *zi (> *ii). Therefore,we have to assume that the starting point was *-ziiai (with *-zi- from the active *-zi).

11 Cf. MEISER 2003:57, who assumes that the medio-passive ending „*-sey“(> -rī) in the 1st, 2nd and 4th conjugations is a back-formation from the active ending

161

My explanation of the middle ending -rier is similar to that proposedby Meiser (2003: 57f.). The main difference is that he derives it from*-điēr, the same formation as pSab. *-fiẹr (see above), while I prefer toconnect it with a probable precursor attested in the Duenos inscription.

References

BARTHOLOMAE 1890: Chr. Bartholomae, Das griechische Infinitivsuffix-sqai, “Rheinisches Museum für philologie” 45, 1890, 151-153.

BROCK 1897: A. Brock, Quaestionum grammaticarum capita duo. Iurievi(Dorpati), C. Mattiesen, 1897.

BRUGMANN 1904: K. Brugmann, Die Demonstrativpronomina der in-dogermanischen Sprachen. Eine bedeutungsgeschichtliche Unter-suchung,Teubner, Leipzig, 1904.

BRUGMANN 1909: K. Brugmann, Altitalische Miszellen, “Indo germanischeForschungen” 24, 1909, 72-86.

CHANTRAINE 1968: p. Chantraine, Dictionnaire étymologique de lalangue grecque. Histoire des mots, Klincksieck, paris, 1968.

CRUSIUS 1992: Fr. Crusius, Römische Metrik. Eine Einführung. 8. Aufl.Neu bearbeitet von Hans Rubenbauer, Max Hueber,Münschen,1992.

DUpRAz 2004: E. Dupraz, ūtor, ūteris, ūsus sum, ūtī, in A. BLANC – J.-p.BRACHET – C. DE LAMBERTERIE (edd), Chronique d’étymologielatine, No 2, 237-239, “Revue de philologie” 78/2, 2004, 317-339.

EICHNER 1988-1990: H. Eichner, Reklameiamben aus Roms Königszeit,“Die Sprache” 34, 1988-1990, 207-238.

GARCÍA-RAMóN 1993: J.L. García-Ramón, zur Morphosyntax der pas-sivischen Infinitive im Oskisch-Umbrischen: u. -f(e)i, o. -fír undursabellisch *fiẹ (*-dhieh1), in H. RIX (ed), Oskisch-Umbrisch:Texte und Grammatik. Arbeitstagung der IndogermanischenGesellschaft und der Società Italiana di Glottologia vom 25. bis 28.September 1991 in Freiburg, Dr. Ludwig Reichert, Wiesbaden,1993, 106-124.

HARTMANN 2005: M. Hartmann, Die Frühlateinischen Inschriften und

„*-si“ (> -re) under the influence of the medio-passive ending „*-ey“ (> -ī) of the 3rdconjugation.

THE 2ND LINE OF THE DUENOS INSCRIPTION

162 J. A. HARðARSON

ihre Datierung. Eine linguistisch-archäologisch-paläographischeUntersuchung, Ute Hempen, Bremen, 2005.

KLINGENSCHMITT 1987: G. Klingenschmitt, Erbe und Neuerung beimgermanischen Demonstrativpronomen, in R. BERGMANN – H.TIEFENBACH – L. VOETz (edd) Althochdeutsch, Carl Winter,Heidelberg, 1987, 169-189.

LINDSAY 1907: W.M. Lindsay, Syntax of Plautus, James parker & Co,Oxford, 1907.

LIpp 2009: R. Lipp, Die indogermanischen und einzelsprachlichenPalatale im Indoiranischen. Band II: Thorn-Problem, indoirani -sche Laryngalvokalisation, Carl Winter, Heidelberg, 2009.

LIV = Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben. Die Wurzeln und IhrePrimärstammbildungen. Unter der Leitung von Helmut Rix undder Mitarbeit vieler anderer bearbeitet von Martin Kümmel,Thomas zehnder, Reiner Lipp und Brigitte Schirmer, Dr. LudwigReichert, Wiesbaden, 1998.

LIV2 = 2nd edition of LIV. (zweite erweiterte und verbesserte Auflagebearbeitet von Martin Kümmel und Helmut Rix), Dr. LudwigReichert, Wiesbaden, 2001.

MEIER-BRÜGGER 2007: M. Meier-Brügger, Infinitiv-Formans *-dhio- <*-dhh1io-?, in A.J. NUSSBAUM (ed.), Verba docenti. Studies in his-torical and Indo-European linguistics presented to Jay H. Jasanoffby students, colleagues and friends, Beech Stave press, Ann Arbor,2007.

MEISER 1998: G. Meiser, Historische Laut- und Formenlehre der lateini-schen Sprache, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt,1998.

MEISER 2003: G. Meiser, Veni, vidi, vici. Die Vorgeschichte des lateinis-chen Perfektsystems, C. H. Beck, München, 2003.

MELCHERT 2007: H.C. Melchert, Luvian Evidence for PIE *h3eit- ‘takealong, fetch’, “Indo-European Studies Bulletin” 2007.

RIX 1985: H. Rix, Das letzte Wort der Duenos-Inschrift, “MünchenerStudien zur Sprachwissenschaft” 46, 1985, 193-220.

SCHWYzER 1959: E. Schwyzer, Griechische Grammatik. 1. Band:Allgemeiner Teil. Lautlehre. Wortbildung. Flexion. Dritte, unverän-derte Auflage, C. H. Beck, München, 1959.

SIHLER 1995: A. Sihler, New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin,Oxford University press, New York – Oxford, 1995.

STEINBAUER 1989: D. Steinbauer, Etymologische Untersuchungen zu denbei Plautus belegten Verben der lateinischen ersten Konjugation.Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Denominative. DissertationRegensburg, Druckerei Gräbner, Altendorf b. Bamberg, 1989.

163

SzEMERÉNYI 1996: O.J.L. Szemerényi, Introduction to Indo-EuropeanLinguistics. Translated from Einführung in die vergleichendeSprachwissenschaft, 4th edition, 1990, with additional notes andreferences, Clarendon press, Oxford, 1996.

TICHY 2002: E. Tichy, Gr. oi[sein, lat. ūtī und die Mittelzeile der Duenos-Inschrift, “Glotta” 78, 2002, 179-202.

VINE 1999: B. Vine, A Note on the Duenos Inscription, “UCLA Indo-European Studies” 1, 1999, 293-305.

WEISS 2009: M. Weiss, Outline of the Historical and ComparativeGrammar of Latin, Beech Stave press, Ann Arbor, 2009.

THE 2ND LINE OF THE DUENOS INSCRIPTION