Surviving the Eco-Apocalypse: Losing the Natural World and ...

Surviving the Dirty Thirties: A Story of Kansas Farm Families and Survial in the 1930s

Transcript of Surviving the Dirty Thirties: A Story of Kansas Farm Families and Survial in the 1930s

Surviving The DirtyThirties

A Story of Kansas Farm Familiesand Survival in the 1930s

John Patchen

The 1930s was a tumultuous period for agriculture in Kansas. Drought, soil erosion, swarms of insects and notorious dust storms were but a few of the hardships that Kansas farm families faced as they struggled to survive what was arguably the toughest recovery period in the history of Kansas agriculture. “Surviving the Dirty Thirties” examines four Kansas farm family’s survival during these challenging times through the use of mechanization to increase production, diversification to adapt to the changing environmental and economic climate, and the use of varied market strategies to improve profitability as markets fluctuated. While many crop yields decreased in average yields throughout the state, the total

Patchen 1

acres planted per year increased by the end of the decade, and overall grain output statewide remained relatively unchanged despite a severe lack of precipitation. The story of these four families provides a compelling insight as to how some Kansas farm families were able to survive the Dirty Thirties.

Patchen 2

Kansas has been known as an agricultural based state

virtually since its entry into the union in 1861. Agriculture

is more susceptible to nature’s influences that can cause this

aspect of the Kansas economy to flourish or decline more than

most. One such example is drought, and this was certainly the

case during the Dirty Thirties.1 The recovery of Kansas

agriculture from the 1929-1941 drought is nothing short of

remarkable given the myriad of obstacles that the Kansas farmer

faced.

There were many federal programs to assist farmers through

the 1930s. While some farmers took advantage of federal programs

such as the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act and the Agricultural

Adjustment Acts of 1933 and 1938, there were those farmers who

managed to survive the Dirty Thirties without these programs.

For those farmers who survived the 1930s with minimal government

assistance, recovery from the drought of the 1930s was due

1 Author’s Note: The term Dirty Thirties was used quite frequently by those individuals interviewed by the author. The term refers to the frequent duststorms that were experienced during the 1930s, and the fact that, after the storms, houses, cars, animals, and people would be covered with a layer of dirt, as well as dirt in their eyes, ears, noses, etc.

Patchen 3

primarily to three factors: the introduction of mechanization,

diversification, and sound market strategies.

Several questions must be addressed when examining how many

families managed to recover from this historic drought and not

only produced respectable yields, but in some years produced

record yields. Some families were primarily cash grain

operations, others were diary, yet others had a balance of

livestock and grain. They all shared common difficulties though,

the nutrient-rich topsoil was long gone, blown away during the

dust storms of the early 1930s, and what top-soil remained was

short of moisture after several years of below average rainfall.2

The Great Depression of the 1930s meant that many Kansas

families had to drastically curtail spending during years of poor

production. Towards the end of the 1930s, due largely to the

wheat harvest of 1938,3 purchases of farm tractors began to

increase and farmers were primed to plant even higher numbers of

acres.4 If a farmer survived the Dirty Thirties, chances were he 2 Kansas State University. Annual Rainfall Totals 1900- 1999. (Manhattan: Kansas State University, 2000), 5.3 United States Department of Agriculture, National Agriculture Statistics Service, Kansas Field Office. Kansas Wheat History. Kansas Annual Wheat Report (Topeka, Kansas, 2012) 344 See Charts in Appendix A

Patchen 4

had seen the worst of times. Times were bleak during the 1930s,

but they were not always that way.

They years leading up to the Dirty Thirties were actually

successful and profitable, “prior to the 30s there weren’t any

[hardships]”5 remarks Riley Winkler “’28, ’29, ’30, ’31, ’32 were

good crops, but farmers were getting a dime a bushel for their

wheat.”6 For Winkler’s father who farmed 1280 acres of wheat

near Montezuma, Kansas, an average wheat harvest could yield

about 18,500 bushels. However, farmers in western Kansas

received far less per bushel than those in eastern Kansas.7

Location was everything, and at ten cents a bushel, Riley’s

Dad was getting about a third of what an eastern Kansas farmer

got per bushel. On average, farmers in eastern Kansas received

about twenty cents a bushel more for their wheat.8 Still,

Riley’s father made a respectable average of $1850 per year

during that time span. The wheat harvest of 1931, which produced

251 million bushels, would remain the best on record until 1947,9

5 Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).6 Ibid.7. United States Department of Agriculture, Kansas Wheat History. 31.8 See author’s note in Appendix A.9 United States Department of Agriculture, Kansas Wheat History. 31.

Patchen 5

yet the abundance of wheat that year drove market prices down and

wheat was at an all-time low.10

In just a few short years, everything would change. The

fields were dry, the rains had stopped coming. Years of

continuous farming and moldboard plowing had taken their toll on

the prairies, and Mother Nature was extracting her revenge.

Everyone continuous farmed. As soon as you got one crop

out, you put the next one in. When the wheat was done, you

had to plant your livestock feed. In western Kansas, we

didn’t have hay like you guys here in the east, so you had

to plant the feed to feed your livestock. The plow was the

only way to put the stubble and the weeds under, so as soon

as the combine was done, you got on the tractor started

turning everything under. They didn’t know then that that

was the cause of all the problems, but turning all that dirt

over left it exposed, and when it all dried out when the

winds came, there was nothing to keep it from blowing

away.11

10 See Author’s Note in Appendix B.11 Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).

Patchen 6

Even in the dry years, Kansas families continued to plant.

They didn’t have a choice, farming was their livelihood and for

many, the only thing they knew how to do. Of course there was

the weather they had to contend with, winter month’s subfreezing

temperatures, and hot summer months with temperatures that could

reach 100° sometimes with no rain in sight. The Kansas annual

wheat report mentions crops plagued by pests,12 and then there

were even those infamous dust storms. If these natural threats

to their livelihoods were not bad enough, man-made threats were

worse.

Some Kansas families had to contend with fellow farmers

stealing crops straight from their fields. Pete Thompson, whose

family farmed near Colby, Kansas remarked, “Dad used to tell me

stories of how Grandpa had to hire men to stand guard over his

fields to keep other farmers from coming in and cutting their

wheat during the 30s…they’d come in at night while it was dark

and hand cut the wheat to augment their own wheat harvest.”13

12 United States Department of Agriculture, Kansas Wheat History, 8-9.13 Pete Thompson interview with the author, (October 21, 2013).

Patchen 7

Somehow, Kansas farm families endured. The number of acres

planted steadily increased, while for many crops, average bushel

per acre yields dropped during the “Dirty Thirties”14 What is the

most remarkable part of the equation is that during the years of

1929-1945 eastern Kansas farmers enjoyed only five of seventeen

years where rainfall was above the historical average of 36.88

inches.15 Western Kansas farmers experienced far greater

drought.16

In eastern Kansas from 1930-1939, there was only one year

where rainfall exceeded the historical average in any significant

quantity. The year 1931, which would stand as a record crop for

16 years, saw an excess of 4.31 inches of rainfall.17 In 1938,

the total rainfall exceeded the historical average by .10 inch.18

The other eight years saw rainfall averages fall short in varying

amounts from -2.16 inches to -15.73 inches.19 For the entire

ten-year period, eastern Kansas was -66.22 inches behind on

14 See Appendix C. 15 National Weather Service Forecast Office, "Kansas City annual precipitation 1889-2010." Last modified December 18, 2008.

16 Kansas State University. Annual Rainfall Totals 1900- 1999, 5.17 National Weather Service Forecast Office, "Kansas City annual precipitation 1889-2010."18 Ibid.19 Ibid.

Patchen 8

rainfall.20 The wheat harvest suffered tremendously during these

years, and some farmers turned to other crop types as

supplemental crops.21

1938 was quite possibly the most memorable year for many of

those farm families that chose to go with minimal government

assistance. In many recollections, those individuals who were

around to remember the 1930s recall family members making

significant purchases in 1938.22 Riley Winkler remembers that

after the 1938 wheat harvest, his father purchased a new pickup

truck and a new car for his mother.23 Pete Thompson recalls that

his grandfather purchased a new John Deere D tractor that year to

take over belt work24 from the large crawlers25 he already owned.

Jackie Flory, who grew up in rural Douglas County Kansas, also

remembers that her father purchased a used International

Harvester tractor that same year. The purchase of this tractor

20 Ibid.21 See Appendix C and D.22 Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).23 Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).24 Pete Thompson interview with the author, (October 21, 2013).25 Jackie Flory interview with the author. (October 29, 2013).

Patchen 9

allowed her father to rent more ground and increase the

productivity of the farm.26

In 1938, Kansas farmers planted 16.9 million acres of wheat

and harvested 14.4 million of those acres. However, the yield

was only an average of 10.5 bushels per acre (bu. /acre) and the

total production was 152.2 million bushels.27 That year, Kansas

was slightly above the historical average on rainfall, but the

previous six years of negative rainfall totals meant that soil

moisture was already down, and the lack of precipitation that

year after seeding damaged the wheat crop.28 Even though the lack

of precipitation from the previous years hampered the overall

production of the harvest, the overall lack of wheat within the

market drove the price up that year, and what wheat was in the

market brought a premium price.29

Wheat was not the only crop that struggled. Most of the

other Kansas crops saw significant decrease in yields, though

oats saw a significant increase in yield during the 1930s. Corn

26 Ibid.27 United States Department of Agriculture, Kansas Wheat History. 31.28 United States Department of Agriculture, Kansas Wheat History, 7-8.29 Ibid.

Patchen 10

dipped in yield production from a previous ten year average of

21.3 bu. /acre to 13.1 bu. /acre, a drop in production of almost

38.5 percent.30 Hay production went from 1.34 tons per acre to

1.12 tons per acre, a drop of 16.5 percent.31 As mentioned

previously, wheat went from a ten year average of 13.4 bu. /acre

to 11.8 bu. /acre, a net loss of almost 10 percent.

While these numbers may not appear to be significant, for a

farmer with a 160 acre farm, they could be devastating. To put

it in contextual perspective, the loss of .20 tons of hay per

acre in a 15-acre hay field meant a loss of 3 tons of hay over

the entire field. Spread over three or four similar fields, the

farmer lost 12 tons of hay. The loss of that much hay to feed

over the winter meant that the farmer would have to down-size his

cattle herd or worse yet, sell off a horse, and for some farmers,

the primary means of working the land.32

In the grain markets, the loss of yields was even worse.

The two bushel per acre drop in wheat production was more severe

30 United States Department of Agriculture, "Kansas Corn Yields." United States Deparment of Agriculture NASS Database. Generated October 18, 2013

31 United States Department of Agriculture, “Kansas Hay Production.” United States Department of Agriculture NASS Database. Generated October 18, 2013.

32 Jackie Flory interview with the author. (October 29, 2013).

Patchen 11

at the time than the drop in corn production. Corn during the

1930s was primarily grown for animal feed on the farm. Wheat

however, was a cash crop, and a two bushel per acre loss in wheat

production was felt far more than an eight bushel per acre drop

in production for corn.

Grain was not only a source of cash income, it was a source

of livestock feed. For many farmers in western Kansas, once the

wheat harvest was harvested, grain for their livestock was

planted. The type of crop grown varied, but barley was one source

of grain grown for livestock.33 Another source of grain grown

for livestock was a type of sorghum prominently grown in western

Kansas.34 The drought had its effect on livestock feed production

as well, and reduced yields meant less feed for livestock, and

forced farmers and ranchers to reduced herd sizes.35

Even though farmers and ranchers were forced to reduce herd

sizes, not all of them took advantage of government programs such

as the Federal Surplus Readjustment Act (FSRA). Pete Thompson,

whose father and grandfather farmed near Colby, Kansas, remembers

33 Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).34 Ibid.35 Ibid.

Patchen 12

that his grandfather was forced to reduce the size of his cattle

herd. His grandfather refused to take advantage of the kill off

program. Instead his grandfather was able to sell some of his

cattle to the Army installation at Fort Riley, Kansas, where they

were slaughtered and fed to the troops.36

Yet, for all these hardships the question remains as to how

farmers who took minimal government assistance survived the

1930s? There is no magical answer, no clear-cut definition. It

is literally a finely woven, interconnected series of events,

technology, hard work, determination, diversification and

skillful market planning. For some Kansas farm families,

surviving the Dirty Thirties actually meant expanding their farms

to increase acreage. For others, it meant skillful use of

existing acreage with technology, diversity and the ability to

control when they sold their crop. Yet to another farmer it

meant a combination of expansion, mechanization, diversity and

market management.

Hard work and determination are not intangibles that can be

measured, nor can their impact fully be quantified. At the same 36 Pete Thompson interview with the author, (October 21, 2013).

Patchen 13

time, their importance and the role in the recovery from the

Dirty Thirties cannot be dismissed. Yet to truly understand how

these families recovered from the 1930s, one must identify those

events and actions that can be measured.

There can be little doubt that technology and

diversification were the two greatest keys to the agricultural

recovery of the Dirty Thirties. Determining which one is greater,

however, is a far greater challenge. In reality, both events had

equal impact on the recovery. Why so? During the 1930s, Kansas

was agriculturally and geographically diverse. So while a farmer

in western Kansas benefited from technology and being able to

plant large numbers of acres, a farmer in eastern Kansas could

very well benefit from being diverse and having a smaller number

of acres but a wider variety of crops and livestock.

The importance of technology to the Flory, Thompson and

Winkler families was dramatic. In the interviews conducted with

these family members, all distinctly recall increased

productivity. Two of the three family members interviewed noted

that family members either purchased or leased additional ground

Patchen 14

within a few years of the purchase of their family’s first

tractors.37 It is of note that all of the additional land

purchases or leases occurred during the 1930s.

Flory and Thompson recalled that their families either

purchased their first tractor or additional tractors during the

1930s.38 Two western Kansas families already had tractors either

at the beginning of the 1930s were just prior to the 1930s and

had significant acreages of land. The reason for the need for

tractors was obvious. With large acreages of land, tractors were

far more efficient than horses.

The size of the farm dictated the size of the tractor. In

western Kansas it was more common to see a Rumley Oil-Pull or

Caterpillar crawler.39 These larger horsepower tractors were

needed to farm the larger farms found in western Kansas. But in

eastern Kansas, where a farmer might only have 160 or 320 acres,

a farmer could manage with a much smaller tractor. Still a

37 Jackie Flory interview with the author. (October 29, 2013), 38 Jackie Flory interview with the author. (October 29, 2013), Pete Thompson interviewwith the author, (October 21, 2013).

39 Author’s note- crawlers were tractors equipped with tracks. The term came from the way the tracks “crawled” across the ground.

Patchen 15

tractor was a significant investment for a farmer, but the

increase in production was well worth the investment.

Otto Boerkircher, who farmed in Douglas County all of his

life, bought an Allis Chalmers WC for $650 in 1937.40 The WC was

a legitimate 2-3 plow tractor.41 By pulling two plows at nearly

twice the speed of a horse-drawn team, he could cover twice the

land in a day. The addition of the belt pulley meant that Otto

could now purchase machinery that could be driven by the belt

pulley, further increasing the productivity of the farm. With

the power takeoff unit, Otto could purchase a small pull-type

combine to harvest his crops. The purchase of this tractor

allowed Otto to greatly improve profitability on the farm without

adding additional manpower.42

Out in western Kansas, the picture was entirely different.

Farmers had larger tracts of land and needed larger tractors.

Riley Winkler recalls that his Dad’s first tractor was a Rumley

Oil-Pull.43 The Oil-Pull was a large kerosene-burning tractor

40 Otto Boerkircher interview with the author. (September 14, 1991)41 Please see Appendix E .42 Joe Turner interview with the author. (Ocotber 22, 2013).43 Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013)..

Patchen 16

initially stated as a 30-60. However, they tested closer to 40–70

during the 1924 Nebraska Tractor Tests.44

Pete Thompson recalls that his grandfather purchased two

large Caterpillar Diesel Sixties in 1931,45 some of the first

diesel tractors in the county.46 These crawlers were larger than

Winkler’s father’s Rumley. They tested at 65-77 in 1932, making

them a 6-7 plow tractor.47 With two of these crawlers, his

grandfather could do the equivalent work of nearly six four-

horse plow teams—with dramatically less manpower. This would be

vital to offsetting the reduced wheat yields of the 1930s.48

The use of tractors meant that all of these farmers could

farm more land. Tractors could work larger tracts of land, at

greater speeds, with larger equipment. Fuel was cheap in the

1930s as Thompson recalls, “Fuel was cheap, three or four cents a

gallon, and you could do so much more work with those big

44 Brackett, E.E. Nebraska Power Test #103. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1924.)45Author’s note- Mr. Thompson refers to these tractors as “Diesel Sixties,” and for a few years they were marketed as such, but in 1933/4 Caterpillar changed the model designation to “Diesel Sixty-Five” after the Nebraska Test revealed a higher horsepower rating.

46 Pete Thompson interview with the author, (October 21, 2013).47 Zink, Carlton L. Nebraska Tractor Test #203. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1931.)48 See tables in Appendix D, Appendix F .

Patchen 17

Caterpillars. It didn’t take long for Dad and Grandpa to realize

that two tractors were more cost efficient than two four-horse

plow teams.”49

The ability to work more land meant that, even in the

drought years, these farm families could offset lower yields by

having more acres to harvest. Even with wheat falling to 11.8

bu./acre, if a farmer doubled the amount of land he worked, he

could still have a higher gross income.50 Otto Boerkircher, who

had a significantly smaller farm, required a smaller tractor. The

Winkler family farm was much larger than Boerkircher’s, required

a larger tractor. The Thompson family, who had the largest farm

of all the families, required the largest tractors available.

Jackie Flory recalled that her dad leased an additional 160

acres shortly after the purchase of their first tractor in

1938.51 Thompson recalled that within a few years of his family

purchasing the two Caterpillar Diesel Sixties, they expanded

their acreage.52 The use of mechanization allowed families to

49 Pete Thompson interview with the author, (October 21, 2013).50 Please see Appendix51 Jackie Flory interview with the author. (October 29, 2013).52 Pete Thompson interview with the author, (October 21, 2013).

Patchen 18

increase the size of their farms, and for these families, the

impact was almost immediate.

Each individual interviewed asserted that the use of

tractors on the farm was significant in its increase in

productivity. Flory estimated “at least double the amount of

work,”53 while Winkler suspected “a couple hundred percent

increase”54 in overall production. Thompson concurred with

Winkler, suggesting a “two to three hundred percent increase in

the amount of work done and a significant decrease in the amount

of time it took to get it done.”55

An understanding of the market and skillful utilization of

the resources they had in terms of grain and livestock and other

assets on the farm were also vital to surviving the 1930s. Not

all farmers had the means to store grain on the farm, but those

that did had an invaluable asset. By storing grain, farmers had

the ability to wait for the market to rise and sell that grain at

higher prices. As Winkler and Thompson recalled, those who could

53 Jackie Flory interview with the author. (October 29, 2013).54 Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).55 Pete Thompson interview with the author. (October 21, 2013).

Patchen 19

not store grain normally had to sell it right out of the field at

lower prices.56

Grain storage requires a dedicated storage facility and many

smaller farmers with less acreage may not have been able to

afford such a facility. Riley Winkler recalls that his dad

converted an old barn they no longer used for machinery storage

into a granary.57 Pete Thompson’s grandfather did the same.58 The

facilities allowed these men to hold their crop until the market

rose and the price were more favorable.

Winkler remembers his father selling wheat “Dad had this old

barn he’d converted into a granary. He drove down the center

aisles, the bins were on sides, he’d fill the truck up with

wheat. When he needed to sell wheat, he’d take a little wheat

into town, get a quarter a bushel. He’d always take a different

route when he’d go to town; he didn’t want the neighbors to know

we had wheat there on the farm.”59 The difference between

56 Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).57 Riley Winkler, interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).58 Pete Thompson interview with the author. (October 21, 2013).59 Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).

Patchen 20

getting a dime a bushel for those farmers selling straight out of

the field and a quarter a bushel later was huge.

Grain production was the primary source of income for many

Kansas farmers. The drought of the 1930s saw the average yield

per acre drop as a statistical whole. A year by year analysis of

the 1930s shows that most crop declined in yields in terms of

bu./acre from 1931-1935, they then began to increase and

stabilize by the end of the decade.60 Reduced yields per bushel

meant less income per acre, the primary way to offset this was to

increase one’s acreage.61 The Kansas farmer’s ability to adapt

to the changing conditions, diversify his operation, implement

new crop types, was monumental to his survival.

Wheat remained the primary crop in Kansas during the 30s,

but the emergence of other crop types played a pivotal role in

the survival of the Kansas farmer. Corn was used as a livestock

feed, as was barley and oats. The changes in the weather

patterns forced Kansas farmers to change their normal crop

rotations to adjust for the moisture that was available during

60 Please see Appendix D, Appendix F.61 Please see Appendix D, Appendix F.

Patchen 21

specific times of the year. More acres of oats were planted,

barley began to supplant corn as a primary livestock feed.

Oats were one of the few crops in Kansas that actually saw

significant increase in yield during the 1930s. Otto Boerkircher

was well known for his affinity for growing oats,62 and Thompson

recalled his family planting some oats as well.63 To understand

why oats were appealing to some farmers, one must understand the

planting cycle, the growth cycle, the root structure, and the

moisture needs of this crop. Unlike wheat, oats can be planted in

early spring. The old farmer saying, “throw them in the mud,” is

not far from the truth. Oats can be planted at a lower soil

temperature and, provided it is warm, enough can be planted mid-

March.64 They have a relatively short growing season and can be

ready for harvest in late June.

Since oats have a much shallower root structure,65 the roots

don’t need to go as deep in the soil to get to moisture. So, on

drought ridden soils, any rain that falls can be readily absorbed

62 Joe Turner interview with the author. (October 22, 2013).63 Pete Thompson interview with the author. (October 21, 2013).64Stoskopf, N. C. “Cereal Grain Crops.” (Reston: Reston Publishing Company. 1985.), 168-91.65 Ibid

Patchen 22

as it hits the soil. Furthermore, since oats have such as short

growth cycle,66 they are less likely to be “burned” by high

temperatures and the “blow winds” that made the 1930s famous.

Additionally, if the previous winter had any significant

snowfall, there would be moisture in the soil for the first vital

month of the growth cycle. These factors made oats an appealing

option for Kansas farmers in the 1930s.67

While barley didn’t see the growth in popularity state wide

that oats saw, it was still a popular crop for some Kansas

families. Both Flory and Winkler recall their families planting

barley,68 and neighbors recall that Boerkircher planted barley as

well.69 Barley was used primarily as a livestock feed but also

as a cash crop. The reason for barley’s popularity in the 1930s

was due largely to its drought tolerance. Barley, unlike corn,

is not as moisture demanding and can tolerate high

temperatures.70 Furthermore barley is a small grain and does not

66 Ibid.67 Riley Winkler, interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).68 Jackie Flory interview with the author. (October 29, 2013, Riley Winkler interview with the author. (October 23, 2013).

69 Joe Turner interview with the author. (Ocotber 22, 2013).70 Stoskopf, N. C. “Cereal Grain Crops.” (Reston: Reston Publishing Company. 1985.), 38-51.

Patchen 23

require a hammer mill or a grinder for preparation as a livestock

feed.

Barley can be planted in the fall or in the spring.71 When

planted in the spring, barley can be planted in early March and

harvesting can begin as early as June.72 Barley requires a

minimum of 10 inches of rainfall to produce a decent crop.73

During a drought year, this factor would have been extremely

important when considering what crops to plant. Like oats, barley

owes its resiliency to the fact that it has a hardy root

structure.74 However, barley is not as tolerant to colder

temperatures and therefore winter planting does carry some risk

for Kansas farmers.75

Diversity was significant to these families. Wheat remained

the primary cash crop, though prior to the 1930s corn was also a

significant crop in Kansas. As the 1930s progressed corn

diminished in total acres planted, and a new crop, sorghum, began71 Anderson et al. . “Growth and Development Guide for Spring Barley”. University of Minnesota Agricultural Extension Folder AG-FO-2548, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1985.) 1.

72 Stoskopf, N. C. “Cereal Grain Crops.” (Reston: Reston Publishing Company. 1985.), 38-51.73 Ibid.74 Ibid.75 Ibid.

Patchen 24

to increase in total acres planted.76 By diversifying into more

drought resistant crops, or crops that were better suited for the

precipitation cycles that were occurring, these families were

able to continue to survive the 1930s.

As mentioned previously, grain was the primary source of

income for many Kansas farmers; however livestock was an

important secondary source of income as well as sustenance. Many

Kansas farmers also adjusted their livestock operations during

the 1930s. A large number of farmers scaled-back cattle

operations, dairy operations, and many moved out of cattle

operations altogether in favor of hogs. Cattle operations

required roughage during the winter months and pasture during

spring and summer, as well as grain for feed. Hogs, on the other

hand, were less diet restrictive and the range of feeding options

was much wider.

Hogs consume barley, corn, oats, or even table scraps for

feed. While they did require some roughage such as hay, a 200-

300 pound hog certainly did not require nearly as much hay per

day as an 800-1,000 pound cow. A farmer could have two or three76 Please see Appendix D.

Patchen 25

hogs for each cow. Hogs also demand significantly less water,

another valuable resource during the 1930s.

Finally, it must be considered is how these factors all

combined to allow Kansas farmers to plant ever-increasing numbers

of acres of crops. From the beginning to the end of the 1930s, in

the most difficult times, Kansas farmers steadily increased the

number of acres planted per year, while bushel yields

struggled.77 This fact cannot be lost on future generations for

it shows the resiliency of the Kansas farmer during the 1930s.

In many ways, surviving the 1930s without minimal government

assistance was all about numbers—the little numbers that matter.

Mechanization meant not only greater productivity, it also meant

greater profitability. It allowed the Kansas farmer to do more

work, plant more acres and offset reduced grain yields.

Diversification also meant greater productivity and

profitability. In a time where every cent mattered, every square

foot of land counted and every animal they had to feed counted,

farmers could ill afford to resist change. The ability to have

some control over the markets was just as important, and those 77 Please see Appendix D.

Patchen 26

farmers who had that ability had a decided advantage. They had

the ability to sell at higher prices and increase profitability.

The story of how some Kansas farm families survived the

Dirty Thirties with minimal assistance is one of perseverance.

The sheer will and determination, resiliency and drive are traits

for which many Kansans are known. But the survivors of the Dirty

Thirties are different in ways that words just cannot describe.

As the men and women who survived these terrible times age and

eventually pass on, so too does our link to this remarkable

period in Kansas history. Theirs is a story that needs to be

recorded and passed on to future generations to not only learn

from, but to experience in ways that words do not always do

justice.

Patchen 27

Appendix A

The author, who is neighbors with the individual interviewed, inquired again about the disparity between the pricestated in the interview and the prices shown both on the NASS database, and the Kansas Annual Wheat Report, (which show Identical numbers.) Mr. Winkler admitted that it was possible that his father could have received a higher price, but that his recollection was that, on average, western Kansas wheat prices were a about ten to fifteen cents lower than what eastern Kansas farmers received. This is certainly plausible, as numerous factors account towards market prices, such as test weight, moisture content, crop condition, etc., though in the 1930s grainelevators did not have the technology to measure moisture content. Factors such as shipping to major railway stations alsofactored into local elevator prices.

Appendix B

The most probable explanation for the reduced prices in 1931and 1932 was market gluttony. During years in which the market is flooded with a surplus, prices drop significantly. Depending on how the market for that particular crop was prior to the “bumper crop” year, it the market may take only a year or two to stabilize, or it may take several years, depending on how the stocks of that particular crop are nationwide. Given that the five years prior to 1931 were all rather productive, and that 1932 was on par with the harvests averages of those five years, (United States Department of Agriculture 2012, 31) it is understandable that prices stayed low in 1932 as well. The harvest of 1933 was almost half of the 1932 harvest, so prices began to rise in 1933. (United States Department of Agriculture 2012, 31)

Appendix C

Patchen 28

The most common crop types in Kansas in the 1920s were wheat, rye, corn, oats, and barley. This remained true in the 1930s, except for the emergence of sorghum as a cash crop. The following table shows the average ten year average yield per acrefor both decades and increase or decrease from the 1920s to the 1930s.

Crop Type 1920s Ten YearAvg.

1930s Ten YearAvg.

Net Increase orDecrease

Wheat 13.11 11.85 -9.61%Rye 10.66 10.63* -.002%Corn 21.23 13.14 -38.10%Oats 21.48 23.66 +9.21%Barley 15.60 13.17 -15.57%Source: USDA NASS Database, “Production Yields Barley, Corn, Rye, Oats, Wheat, 1920-1939”, 2013.

This table indicates shows that except for oats, the primary croptypes in Kansas all suffered during the 1930s. As indicated later in the text, wheat remained the primary cash crop, but somefarmers would shift their secondary cash crops from corn to oats to barley. The data set here suggest that barley suffered far less yield reduction in terms of percentage loss than corn. For essentially the same yield farmers could plant barley, and utilize existing harvesting equipment, without the need for binders (an early form of combine for corn) and other specializedcorn harvesting equipment. This would certainly be appealing forsmaller eastern Kansas farmers who had smaller numbers of acres, and who often shared this type of equipment. (Jackie Flory interview with the author, October 29, 2013.)

Appendix D

The following table show the Kansas wheat harvest for the 1930s:

Patchen 29

Year Acres Planted AcresHarvested

Pct. Harvested

Yield

Bushels Produced

1939 13,703,000

9,574,000

70% 12 114,888,000

1938 16,942,000

14,494,000

86% 10.5 152,187,000

1937 17,110,000

13,172,000

77% 12 158,064,000

1936 14,254,000

10,458,000

73% 11.5 120,267,000

1935 13,456,000

6,888,000

51% 9.3 64,058,400

1934 12,699,000

8,610,000

68% 9.8 84,378,000

1933 13,231,000

7,361,000

56% 9.1 66,985,100

1932 12,963,000

10,365,000

80% 11.6 120,234,000

1931 13,898,000

13,623,000

98% 18.5 252,025,500

1930 13,687,000

13,132,000

96% 14.2 186,474,400

Source: Kansas Annual Wheat Report, Page 31

By comparison, a survey of the most common crops of the 1930s :

YEAR BARLEY CORN OATS RYE SORGHUM WHEAT TOTAL1930 502,000 7,150,00

01,404,000

- 1,685,000 13,687,000

24,428,000

1931 562,000 6,863,000

1,607,000

67,000 1,798,000 13,898,000

24,795,000

1932 731,000 7,687,000

1,703,000

53,000 2,338,000 12,963,000

25,475,000

1933 936,000 7,764,000

1,737,000

48,000 2,759,000 13,231,000

26,475,000

1934 537,000 5,174,000

1,495,000

61,000 3,030,000 12,699,000

22,996,000

1935 433,000 5,600,000

1,694,000

167,000

3,706,000 13,456,000

25,056,000

1936 528,000 5,109,000

2,016,000

144,000

2,962,000 14,254,000

25,013,000

Patchen 30

1937 514,000 2,995,000

1,568,000

187,000

2,699,000 17,110,000

25,073,000

1938 452,000 2,456,000

1,615,000

145,000

2,850,000 16,942,000

24,460,000

1939 1,160,000

3,316,000

1,663,000

152,000

3,157,000 13,703,000

23,151,000

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, Total Acres Planted: Barley, Oats, Rye, Oats, Sorghum, Wheat, 2013.

While the number of acres planted remained relatively stable, thenumber of farms, did not. Both Agricultural Censuses in the 1920s showed 167,000 farms in Kansas. In 1930 the Department of Agriculture Census showed 166,000 farms in Kansas, that number declined by the end of the decade to 161,000. (United States Department of Agriculture, Kansas Farm Facts, 95)

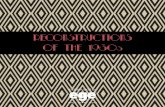

The only crop that saw significant acreage decline was corn,which declined by nearly half of its start-of-the decade production. Those lost acres were supplemented with increased sorghum and rye acreages, and in 1939, barley acreage. During the 1930s, Kansas farmers averaged, 24,692,000 acres planted, while losing 5,000 farms. Compared to the ten year historical average, Kansas farmers dramatically increased production:

Patchen 31

0

5000000

10000000

15000000

20000000

25000000

300000001920

1921

1922

1923

1924

1925

1926

1927

1928

1929

1930

1931

1932

1933

1934

1935

1936

1937

1938

1939

Total Acres Planted 1920-1939

Acres Planted

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, Total All Field Crops, 2013

Appendix E

Plow and Tractor Terminology

Plow and tractor ratings can be a bit confusing even to the most seasoned antique tractor enthusiasts. There are many factors that must be considered when determining a tractors plowing rating. During the 1930s most plows were equipped with either 12

Patchen 32

inch or 14 inch moldboard or bottoms. Determining a tractors plowrating took a number of factors into consideration. The tractors drawbar horsepower rating, soil composition, depth of draft, withof the moldboard, a number of moldboards. Needless to say initially it could be quite confusing determining a tractor’s true working ability.

As plows became larger their terminology changes well. As multiple moldboards became a viable option due to mechanization terminology was adapted that clarified plows for agricultural use. Plows are rated using a two number system and X–Y format that lets the farmer know the number of moldboards and the width of the moldboards. If a plow is rated as a 3–12 plow, that plow has three moldboards that are 12 inches wide. Likewise a plow that is rated as a 3-14 has three moldboards 14 inches wide. This rating system improved farmer’s ability to understand a tractors plow rating.

Now that the plow rating has been explained it is possible to move on to how tractors were rated. Since 12 inch and 14 inch moldboards were the most common forms of moldboard plows during the 1930s a means of rating a tractor for a farmer had to be devised. Taking into consideration the previous factors mentioned, manufacturers determined that for most soil conditionsa single 12 inch moldboard required on average 8-12 horsepower topull at a depth of 8 inches. A 14 inch moldboard required on average, 10-14 horsepower to pull at a depth of 8 inches.

Finally to determine a tractor’s plow rating, manufacturers took a tractors drawbar horsepower and divided it by the average horsepower to pull one 14 inch moldboard and one 12 inch moldboard. So if a tractor was rated at 34 horsepower at the drawbar a tractor had a plow rating of 3 plows (34/12= 2.833 for a 14” moldboard and 34/12=3.4 for a 12” moldboard.) It was not an exact science, because soil conditions varied, but it gave

Patchen 33

farmers a general rule of thumb of what a tractor could do, and with weighting a tractors performance could be improved.

Patchen 34

Appendix F

The following table shows the primary crop type yield by year and the yield for each year:

YEAR BARLEY CORN OATS RYE WHEAT1930 20.5 12.5 28 10.5 14.21931 16 18 29 12 18.51932 14 19 24 11 11.61933 8.5 12 19 9 9.11934 8.2 5.2 16 9.8 9.81935 14 9.5 29 10.5 9.31936 11 6 21 10.5 11.51937 11.5 13 26 11.5 121938 17 21 26 11 10.51939 11 15.2 18.6 10.5 12

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, Total Production: Barley, Corn, Oats, Rye Wheat, 2013.

The numbers show that initally the 1930s were average, as indicated by the Winkler interview. However yields decreased starting in 1933 and continued to decline until 1935. Yields began to slowly stablize, with some fluxuations, until the end ofthe decade. The exception was with oats, which is explained in the text.

Appendix G

While it might be somewhat difficult to reason as to why some families actually benefited by expanding during the 1930s, afurther examination will show why.

A farmer that had 80 acres of availble row crop ground in wheat during the 1930s, and received the average yield of 11.85 bushels per acre would, on average, have 948 bushels of wheat at his disposal per year to sell at market. Compared to the 1920s average of 1048 bushels, he lost 100 bushels per year. During the 1920s the average yearly price was about $1.05 per bushel,

Patchen 36

During the 1930s however, the average price per bushel was about $.70 per bushel. Not only were prices lower, but the farmer was losing 100 bushels a year, and in in some years, a lot more. If the farmer got an average crop of 948 bushels, and the average price of $ .70, the farmer would make $664 for the year, $442 less than what he would make during the profitable 1920s. (United States Department of Agriculture 2012, Kansas Annaul Wheat Report, 31)

However, if the farmer could expand either through purchasing additonal land or leasing, and double his available row crop ground, he could, in theory, double that amount to $1328.

Patchen 37

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Documents

Boerkircher, Otto, interview by John Patchen. (May 17, 1992).

Brackett, E.E. Nebraska Power Test #103. Test Results, Lincoln: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1924.

United States Department of Agriculture. "Historic Kansas Farm Facts, Number of Farms and Land in Farms, 1900-2005." National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2006. http://www.nass.usda.gov/Statistics_by_State/Kansas/Publications/Annual_Statistical_Bulletin/2006/pdf/historic.pdf (accessed November 25, 2013).

—. "Kansas Corn Yields." United States Deparment of Agriculture NASS Database. 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/6AFCA16B-87EF-381F-9EA6-86379E12EAD3 (accessed October 15, 2013).

—.. "Kansas Hay Production." United States Deparment of Agriculture NASS Database. 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/38468630-F795-3131-BAE2-AAC4F98F29F5 (accessed October15, 2013).

—. "Kansas Oat Yields." United States Department of Agriculture NASS Database. 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/50372797-3818-3672-96B2-D9C51CEFFD61 (accessed October 15, 2013).

—. "Production Yields: Barley, Corn, Oats, Rye, Wheat." United States Deparment of Agriculture NASS Database. November 25, 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/8206C165-36C5-3A23-B133-FD8FE5784842 (accessed November 25, 2013).

Patchen 38

—. "Total Acres Planted All Field Crops." United States Department of Agriculture NASS Database. 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/B63D8ABA-058C-35DB-AD4B-48E49EEB906F (accessed November 1, 2013).

—. "Total Barely Acres Planted." United States Deparment of Agriculture NASS Database. 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/042414E4-F26D-35C3-BE60-02825D3A4831 (accessed November 1, 2013).

—. "Total Oats Acres Planted." United States Department of Agriculture NASSDatabase. 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/CDC4C9E5-73FD-32AC-A3DE-38C680162E8D (accessed November 1, 2013).

—. "Total Wheat Acres Planted." United States Department of Agriculture NASS Database. 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/5AE67325-FF31-3789-B8BF-143AB46D40D2 (accessed November 1, 2013).

—. "Yields by Year 1920-1939: Barley, Corn, Oats, Rye, Wheat." United States Department of Agriculture NASS Database. November 25, 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/390B19A4-3077-34E4-9D16-83286F7D390F (accessed November 25, 2013).

—. "Yields by Year 1930-1939: Barley, Corn, Oats, Rye, Wheat." United States Department of Agriculture NASS Database. November 25, 2013. http://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/results/8206C165-36C5-3A23-B133-FD8FE5784842 (accessed November 25, 2013).

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agriculture Statistics Service, Kansas Field Office. Kansas Wheat History. Kansas Annual Wheat Report, Topeka, Kansas: United States Department of Agriculture, 2012.

Patchen 39

Kansas State University. Annual Rainfall Totals 1900- 1999. Rainfall Total, Manhattan: Kent State University, 2000.

Zink, Carlton L. Nebrask Tractor Test #304. Test Results, Lincoln: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1938.

--. Carlton L. Nebraska Tractor Test #203. Test Results, Lincoln: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1931.

Interviews

Flory, Jackie, interview by John Patchen. (October 29, 2013).

Winkler, Riley, interview by John patchen. (October 23, 2013).

Secondary Sources

Books

Stoskopf, N. C. “Cereal Grain Crops.” Reston: Reston Publishing Company. 1985.

Documents

Anderson, P.M., E.A. Oelke, and S.R. Simmons. “Growth and Development Guide for Spring Barley”. University of Minnesota Agricultural Extension Folder AG-FO-2548, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1985.

Clement, Ralph W. Kansas Floods and Droughts. National Water Summary, Kansas 1988-89 Floods and Droughts, Lawrence, Kansas: U.S. Geological Survey, 1989.

National Weather Service Forecast Office – Pleasant Hill. "KansasCity annual precipitation 1889-2010." National Weather Service. 2013.