Sri Lanka: Emerging from the ruins - UNHCR

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Sri Lanka: Emerging from the ruins - UNHCR

3R E F U G E E S

2 E D I T O R I A L

A glimmer of hope for some of the world’s worst humanitarian crises.

4It was one of the world’s longest running conflicts, but hundreds ofthousands of civilians in Sri Lanka are ‘giving peace a chance.’ By Ray Wilkinson

ChronologyA brief look at Sri Lanka’s recent history.

Local experiencesHumanitarian workers at the center of the storm.

It’s a minefieldCleaning up after the guns fall silent.

16 W O R L D N E W S

A global map of the latest refugee developments.

Death, despair, hopeWorking on both sides of the front line.

23 Y O U T H

World Refugee Day celebrates young people.

28 S H O R T T A K E S

A roundup of stories from around the world.

30 P E O P L E A N D P L A C E S

31 Q U O T E U N Q U O T E

C O V E R S T O R Y

UN

HC

R/

N.B

EH

RIN

G/

CS

/C

IV•2

00

3U

NH

CR

/L

.TA

YL

OR

/C

S/

TZ

A•2

00

2

4The war lasted fornearly two decades.Around 65,000 people

were killed and more thanone million were forced fromtheir homes. But in the lastyear a fragile peace hasreturned to Sri Lanka.Hundreds of thousands ofpersons have already goneback and the return isexpected to continue thisyear.

28 It was once one ofthe most stablecountries in Africa,

but today Côte d'Ivoire is atthe center of that continent'slatest troubles.

23 To highlight not onlytheir specialproblems, but also

the resilience of millions ofdisplaced young persons,UNHCR has dedicated WorldRefugee Day this year toyouth.

EEddiittoorr::Ray Wilkinson

FFrreenncchh eeddiittoorr::Mounira Skandrani

CCoonnttrriibbuuttoorrss::UNHCR Sri Lanka staff, Morgan Morris, Brenda Barton,Betty Talbot, Fernando del Mundo,Millicent Mutuli, Astrid VanGenderen Stort, Jack Redden

EEddiittoorriiaall aassssiissttaanntt::Virginia Zekrya

PPhhoottoo ddeeppaarrttmmeenntt::Suzy Hopper,Anne Kellner

DDeessiiggnn::Vincent Winter Associés

PPrroodduuccttiioonn::Aloha Scan - GenevaFrançoise Peyroux

DDiissttrriibbuuttiioonn::John O’Connor, Frédéric Tissot

MMaappss::UNHCR - Mapping Unit

HHiissttoorriiccaall ddooccuummeennttssUNHCR archives

RREEFFUUGGEEEESS is published by the MediaRelations and Public InformationService of the United Nations HighCommissioner for Refugees. Theopinions expressed by contributorsare not necessarily those of UNHCR.The designations and maps used donot imply the expression of anyopinion or recognition on the part ofUNHCR concerning the legal statusof a territory or of its authorities.

RREEFFUUGGEEEESS reserves the right to edit allarticles before publication. Articlesand photos not covered by copyright ©may be reprinted without priorpermission. Please credit UNHCRand the photographer. Glossy printsand slide duplicates of photographs notcovered by copyright © may be madeavailable for professional use only.

English and French editions printedin Italy by AMILCARE PIZZIS.p.A.,Milan.Circulation: 224,000 in English,French, German, Italian, Spanish,Arabic, Russian and Chinese.

IISSSSNN 00225522--779911 XX

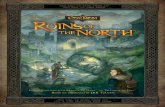

CCoovveerr:: Hope amidst the ruins.

UNHCR/R.CHALASANI/CS/LKA• 2002

UUNNHHCCRRP.O. Box 25001211 Geneva 2, Switzerlandwww.unhcr.org

N ° 1 3 0 - 2 0 0 3

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

CS

/L

KA

•20

02

2 R E F U G E E S

More than a quarter of a million civilians

returned home in the last year following

two decades of war in Sri Lanka.

In Afghanistan more than two million people

went back in 2002 and UNHCR expects to help a

further 1.5 million this year.

A massive repatriation will start shortly in

Angola—yet another country where war persisted

for decades and where a peaceful outcome at times

seemed highly unlikely.

That is the good news. However, as this magazine

went to press conflict in the Middle East began with

the threat of the creation of hundreds of thousands

of new refugees. There were fears the conflict would

dominate not only world headlines, but also the

attention and purse strings of traditional donors

which help uprooted people in all corners of the

globe.

In such circumstances, funding for ongoing

refugee operations sometimes suffers and the

military and political fallout from the ‘new’

emergency also spills over.

Afghan President Hamid Karzai articulated the

concerns of governments, humanitarian officials

and refugees alike in the buildup to war when he

urged the United States: “Don’t forget us if Iraq

happens.”

The situations in Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and

Angola are both delicate and extremely promising.

Tens of thousands of persons were killed and

millions fled their homes in wars which lasted for

generations. But within a few months of each other,

hopes for peaceful solutions blossomed. This hope

will only come to full bloom with the continued

attention and assistance of global goodwill.

Around half of the world’s displaced persons—

some 20 million people—are children and what

is loosely termed ‘young people’ between the ages of

13 and 25.

There are a myriad of agencies and international

laws to protect the children of this group, but

relatively little attention has been paid toward the

problems of youth.

Which is a great pity. At a sensitive time in their

lives, when they are completing their social,

education and sexual personas, young people find

themselves particularly vulnerable to various forms

of exploitation.

To highlight not only their special needs, but also

the key roles they will play in the development of

their local communities and nations—whether they

return to their ancestral homes or begin life in a

new country—this year’s World Refugee Day on June

20 is dedicated to youth.

“Don’t forget us if Iraq happens…”

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

CS

/L

KA

•20

02

Returnees to Sri Lanka..

T H E E D I T O R ’ S D E S K

5R E F U G E E S

After two decades of war, SRI LANKA IS ON THE MEND

by Ray Wilkinson

T he sleek grey vessel sliced out of the mid-night darkness and rammed the tiny fish-ing boat broadside on. Moments before,23-year-old Mohan Raj Sumathi wasflung headlong into the sea, two male pas-

sengers grabbed her three-year-old daughter, Rana,as the boatload of 20 people began fighting for theirlives in the pitch black waters.

The 18-foot long plastic fishing vessel was fol-lowing an ‘inside’ channel on the short 25 kilometerroute between India and Sri Lanka when the sec-ond ship, possibly a patrol boat, hit it. Fortunately,the panicked passengers, none of them able toswim, were protected from deeper seas and greaterdanger by a necklace of islands known as Adam’sBridge. As they struggled to stay afloat in the shal-lows, Rana held above the waves by her two bene-factors, the fishermen righted their capsized boatand the group eventually reached safety.

“We lost everything except our lives, but many peo-ple kissed the land when we reached Sri Lanka,” theyoung mother said as she recounted her traumaticreturn in December last year. “It feels good, very goodto be back. I have no regrets.”

Her homeland had once been described as the Pearlof the Indian Ocean where the term Serendib (fairytale) was coined, an exotic tourist destination withbreathtaking beaches, herds of elephant and otherwildlife, rare birds and elegant peacocks.

But this dreamy spice island began turning into aliving nightmare within years of achieving inde-

pendence from Great Britain in 1948. The majority Sin-halese government adopted a series of measures suchas making their dialect, Sinhala, the country’s sole of-ficial language and controlling access to universityplaces, moves which the minority Tamil communityviewed as a deliberate attempt to marginalize it.

Simmering resentment exploded into violent con-frontation in July 1983, when 13 government soldierswere killed in an ambush by guerrillas of a group call-ing itself the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)demanding full independence for the nearly threemillion Tamils.

Nearly two decades of civil war followed. The Pearlof the Indian Ocean became the Teardrop of Buddha—a reference to its distinctive physical shape and thedesperate straits into which it had sunk.

DESTRUCTION AND KILLINGSHundreds of villages and towns were literally flat-

tened, mainly on the northern Jaffna Peninsula, theneighboring Vanni region and in the east of the coun-try. The world paid only fleeting attention to this ob-scure internal struggle, but an estimated 65,000 per-sons were killed in conflicts which ranged from small-scale hit-and-run raids to massive head-on pitchedbattles. A new form of warfare became commonplace,the precursor of a worldwide phenomenon—the sui-cide bomber.

More than one million people—one in every 18 SriLankans—including Tamils such as Mohan RajSumathi, Sinhalese and members of the country’s Ã

UN

HC

R/

R.W

ILK

INS

ON

/C

P/

LK

A•2

00

3

Safe after a narrowescape.

NEARLY TWO DECADES OF CIVIL WAR FOLLOWED. HUNDREDS OF VILLAGES WERE FLATTENED. AN ESTIMATED 65,000 PERSONS WERE KILLED. MORE THAN ONE MILLION PEOPLE WERE UPROOTED.

6 R E F U G E E S

sizeable Muslim community, fled or were forcibly up-rooted from their homes. The great majority becameinternally displaced, moving between temporary wel-fare centers, friends or relatives homes, sometimes asmany as 10 or 20 times during their prolonged wan-derings. They stayed in each place sometimes for days,sometimes for years, as the course of the conflict ebbedand flowed across the shattered landscape.

Around one million people left the country alto-gether. Many established thriving communities inEurope, North America and Australia, though oth-ers fled as refugees to neighboring India in severalwaves during the 1980s and 1990s and became knownin the Indian press as the region’s new ‘boat people.’

Mohan Raj Sumathi was one of the last to go tothe ‘big neighbor’ in 1998 and her story was typical ofcountless others. Her home village on the Jaffna Penin-sula repeatedly changed hands along with the for-tunes of war. A teenager, pretty and single, she decidedto leave with her mother and brother rather than riskbeing forcibly recruited by the LTTE as a soldier orrunning afoul of the army. She escaped in the same

kind of fishing boat she would later return home on,spent two years in a refugee camp where she met herhusband and started a family in exile.

She had harbored few hopes of returning homequickly, she said. After all, there had already been sev-eral peace attempts in the last few years, but all hadended in failure. And the war, like conflicts inAfghanistan and Angola, had degenerated into agrinding conflict seemingly without end and with-out solution—in humanitarian parlance a so-calledprotracted crisis (Refugees magazine, N° 129).

BREAKTHROUGHRemarkably, however, there were recent major

breakthroughs in all three regions. An estimated twomillion Afghans returned home following the fall ofthe hard-line Taliban regime in Kabul in 2001. InAngola, the scene of one of the world’s most intractablewars in which hundreds of thousands of persons werekilled and more than four million uprooted, a majorrepatriation also began and was expected to gathermomentum through this year.

A makeshift school-house for returningchildren.

ON THE MEND

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

320

69

7R E F U G E E S

In February last year, Colombo and the LTTE, bothwearied and debilitated by the years of fighting, signeda cease-fire accord, began protracted negotiations andannounced a series of compromises. The Tamil Tigers,for instance, eventually dropped their demand for anindependent state in favor of autonomy within a newgovernment structure and in turn were allowed toexpand their political presence in some regions of thecountry.

All sides were only too aware of previous failures,but under the umbrella of a Norwegian diplomaticinitiative, the cease-fire held throughout last year andinto 2003.

Traumatized civilians insidethe country voted with their feet.With few possessions and littlemoney, small family groupshopped aboard trucks and tractorsand headed back to their destroyedtowns and villages. The SriLankan return lacked the dramaand spectacle of Kosovo or Rwanda

where hundreds of thousands of people went backin a matter of days in unstoppable waves, filmed ev-ery inch of the way by the world’s media.

Here it was almost a stealthy homecoming in onesand twos, but no less significant than those other re-turns. By spring, around 260,000 Sri Lankans hadgone back and if the guns stay silent, the rate of re-turn was expected to continue at a similar pacethrough 2003.

Several hundred of the estimated 64,000 refugeesin Indian camps also came home, some like MohanRaj Sumathi preferring to risk the perilous trip byboat because initially it was faster and involved less

WEARIED AND DEBILITATED BY YEARS OF FIGHTING, THE GOVERNMENT AND THE TAMIL TIGERS LAST YEAR SIGNED A CEASE-FIREACCORD, BEGAN PROTRACTED NEGOTIATIONS AND ANNOUNCED A SERIESOF COMPROMISES. AROUND 260,000 CIVILIANS RETURNED HOME.

Ã

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

CS

/L

KA

•20

02

8 R E F U G E E S

official red tape than other routes. UNHCR has nowestablished a free and safer formal repatriation pro-gram for potential returnees.

INCREASED PACENeill Wright, UNHCR’s representative in Sri

Lanka, said he expected the pace of this refugee re-turn to increase significantly once cheap sea ferryroutes, halted during the war, were re-established.

Assisting those refugees will be a major focus forthe agency, but it has already significantly boosted itsactivities to support the dramatic shift towardpeace, approving a $10 million supplementary bud-

get for this year and expanding its physi-cal presence in the war-affected areas.

The organization will continue tospearhead international efforts to en-force its traditional mandate—offering le-gal and physical protection for war-affected civilians—as well as financing arange of special projects to provide newtemporary shelter, health and sanita-tion facilities, kick starting various com-munity services and cheap and quick in-come generating projects to enable re-turnees to become self-sufficient.

“A lot of these activities are bridgingprograms which are necessary until long-term aid from other agencies can kick inlater this year,” Wright said. “There hasbeen a major breakthrough and it is es-

sential to keep the momentum going.”Other, earlier repatriations have faltered at this

stage because what is now referred to in humanitar-ian circles as the ‘gap’ was allowed to develop be-tween the emergency phase of a refugee crisis and thesubsequent need for sustained, long-term develop-ment. In response to harrowing television footage ofrefugees fleeing and dying, the international com-munity all too often has been prepared to pump lav-

ish funds into an emergency, but has been much morereluctant to foot the bill for less sexy and even moreexpensive community and national rebuilding. Hu-manitarian and development organizations com-pounded this problem by cooperating only fitfully.

Last year, High Commissioner Ruud Lubbers an-nounced what he called a 4Rs initiative in which gov-ernments and major organizations would in futurework much more closely together with the aim of pro-viding a seamless flow of aid through an emer-gency’s major phases—repatriation, reintegration, re-habilitation and reconstruction—hopefully elimi-

nating the infamous ‘gap.’Sri Lanka was selected as one of four global regions

to field-test this concept. “Returnee and reintegra-tion assistance alone won’t help Sri Lanka erase thedamage wrought by years of conflict and economicstagnation,” Lubbers said recently and pledged UN-HCR would work closely with institutions such as theWorld Bank, the U.N. Development Program and theAsian Development Bank.

The refugee agency has one other major plus in itscolumn as it helps to try to put Sri Lanka togetheragain, according to Wright and other senior UNHCRveterans. “We were one of the few international or-ganizations which was involved throughout most ofthe crisis, even when things got very rough,” Wrightsaid. “We now have a lot of credibility—with the gov-ernment, with the LTTE and with the civilians wehave been helping. We helped make a difference andthis has translated into donor support for our opera-tions here.”

LONG, DIFFICULT, DANGEROUSWhen the agency opened its first office in Colombo

on November 2, 1987, its aims appeared to be clear-cutand short-term. The military situation had appar-ently stabilized and India dispatched a peacekeep-ing force to Sri Lanka. UNHCR agreed, under itsmainstream mandate, to help the estimated 100,000refugees then in India to return home. The prospectsfor a lasting peace looked good.

An internal report underlined the reality: “Thoughonly modest, UNHCR’s role is widely acknowledgedas being a catalyst in promoting a favorable climatefor the re-establishment of normal life in the northand east of the country.”

There was no foreboding at this time the situationwould soon change so dramatically that the organi-zation would be plunged into uncharted waters, be-coming involved in one of its longest, most difficultand most dangerous operations.

Fighting between the armyand the LTTE intensified in theearly 1990s and swirled with in-creased ferocity across the northand east. The numbers of newlydisplaced persons increased dra-matically. Even some of the

refugees UNHCR had helped return home to start anew life were forced to flee again.

The government and the U.N. Secretary-Generalasked the agency to expand its operations to includenot only the refugees immediately under its mandate,but the far more numerous internally displaced. Inthe context of Sri Lanka’s civil war, it was virtuallyimpossible to differentiate between IDPs and re-fugee returnees.

UNHCR agreed. It would be one of the first timesthe agency became heavily involved with IDPs in suchlarge numbers, but this new commitment did raise

Returning home in 1989. But the warwould soon startagain.

UNHCR WILL CONTINUE TO OFFER LEGAL AND PHYSICAL PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS, AS WELL AS FINANCING A RANGE OF SPECIAL PROJECTS.

ON THE MEND

Ã

9R E F U G E E S

February 4, 1948Ceylon gains independenceafter 152 years of British rule.

June 1956Sinhala, the language of themajority Sinhalese population,is designated the country’s soleofficial language, the first ofseveral government measureswhich the minority Tamilpopulation worried wereofficially inspired efforts tomarginalize them.

1972Ceylon changes its name to SriLanka and Buddhism is givenprimary place as the country’sreligion, further antagonizingthe Hindu Tamil community.

1976The Liberation Tigers of TamilEelam (LTTE), one of severalTamil military or politicalorganizations, is formed astensions increase in the northand east of the country.

July 23, 1983Thirteen government soldierskilled in an LTTE ambush atTinnevely effectively beginningthe country’s civil war duringwhich the guerrillas willdemand full independence forthe country’s nearly threemillion Tamils. Several hundredTamil civilians killed insystematic anti-Tamil riotingand conflict spreads innorthern Sri Lanka. Largenumbers of civilians beginfleeing their homes, becominginternally displaced within SriLanka or refugees inneighboring India.

1987Government forces isolate LTTEin the northern city of Jaffnaand Colombo reachesagreement with India, which issympathetic to the Tamil cause, on thedeployment of an Indianpeacekeeping force to theisland.

November 2, 1987UNHCR begins operations in SriLanka, primarily to assist in therepatriation of an estimated100,000 refugees from India. Atthis time there are anestimated 400,000 civiliansuprooted from their homes,but as the conflict continuesthrough the 1990s, this rises tomore than one million

displaced civilians.

1991The last Indian troops leaveafter getting bogged down inescalating fighting in the northof the country and the LTTEforces take over many of thevacated areas.

1991UNHCR expands its operationsfollowing a specific request bythe U.N. Secretary-General, toinclude helping hundreds ofthousands of civiliansinternally displaced withinthe country. It is one of thefirst times the agency hasworked with such largenumbers of IDPs anywhere.

1991The LTTE is implicated in theassassination of Indian PrimeMinister Rajiv Gandhi insouthern India by a suicidebomber and two years laterPresident Premadasa is killedin a bomb attack by the LTTE,possibly the first group tointroduce suicide bombings asa military strategy.

January 31, 1996 A suicide bomb kills more than100 civilians and woundsanother 1,300 at the Central Bankin the capital, Colombo, and thegovernment extends a state ofemergency across the country.

1997-2000Continuous and intensivefighting in the north and east ofthe country as the fortunes ofwar swing back and forth.President Kumaratunga iswounded and more than 20others killed by a femalesuicide bomber at an electionrally in 1999. As many as 65,000persons are killed during thenearly two-decade longconflict.

February 2002After several previously failedattempts at peace, thegovernment and Tamil Tigerssign a permanent cease-fireagreement, paving the way fortalks under a new peaceinitiative sponsored by Norway.

2002A peace dividend begins. The

major highway linking thenorthern Jaffna Peninsula withthe rest of the country opensfor the first time in 12 years;airline flights to Jaffna resume;the government temporarilylifts its ban on the Tamil Tigerswho drop their demand for aseparate state in favor of someform of autonomy.

2002-2003As a series of negotiationscontinue, some 260,000internally displaced civiliansreturn to their homes. Around1,000 refugees arrive back fromIndia. To consolidate the peaceprocess, UNHCR expands bothits presence in the areas mostaffected by the conflict and itsoverall budget to nearly $15million. The agency will assisthundreds of thousands of IDPsand refugees still waiting to goback to their villages withprotection and materialassistance programs.

Sri Lanka at a glance

Nothing escaped the ravages of war.

UNHCR WILL ASSIST HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF IDPs AND REFUGEESSTILL WAITING TO GO BACK TO THEIR VILLAGES.

©S

EA

N S

UT

TO

N/

PA

NO

S P

ICT

UR

ES

10 R E F U G E E S

questions about its mandate and when, where andhow it should help some or all of the 20-25 millioninternally displaced people worldwide. Although suf-fering similar privations to refugees, internally dis-placed persons do not enjoy similar international pro-tection afforded refugees.

Many live in so-called ‘failed states’ such as Soma-lia. Paradoxically, this may make it easier for interna-tional organizations to help them because they canimpose their own rules and guidelines. But in SriLanka, while providing material assistance and ad-vocating on both sides that civilians must enjoy basichuman rights, UNHCR was fully aware that a func-tioning sovereign government was the ultimate au-thority and protector ofthe population while the LTTEinsisted it spoke for the entire Tamil community.

RAZOR’S EDGE“We were walking a constant tightrope,” said Janet

Lim who was the agency’s representative in the late1990s. “Whatever move you made, it was likely tounsettle one side or another.”

As an internal debate within the agency on itsglobal role towards IDPs continued through the 1990sand into the new millennium, UNHCR’s operations

in Sri Lanka periodically came under review.“At times it was touch and go,” Lim recalls.

There were doubts about the IDP involvement,about costs and the seeming futility of the con-flict. Luckily, perhaps “It was a low cost pro-gram and we were punching above our finan-cial weight at the time,” Lim said. “We gainedenormous respect for staying, but if we had

pulled out, as it was suggested occasionally, we wouldnever have been able to return. It would have been adisaster for so many people we were trying to help.”

On the ground, field personnel were confrontedwith enormous personal risk. In the past, protectionofficers worked on the fringes of ongoing conflicts,helping refugees who had already reached safety. Butthey, along with other emergency staff, were nowpitched into the center of the storm. Officials workedon both sides of the front lines, in government andLTTE-controlled territory, trying to protect civilians,ferrying emergency supplies through and aroundfighting zones, risking attack from both the groundand the air, and even on occasion, from the sea (seestories pages 12 and 20).

Officials had to win and maintain the confidenceof both sides to be able to continue their work ratherthan being branded as military spies, an easy chargeto make against anyone moving between opposingarmies.

A 1989 internal assessment described the delicatesituation: “The repatriation operation in Sri Lankaskates on a glassy pond, and the pirouettes andarabesques that we go through bear no resemblanceto those in any other UNHCR program.”

It added: “Security is tenuous, and incidents re-sulting in injury and death are frequent. The staffmust be simultaneously diplomatic, courageous,patient, wary and energetic. They must also main-tain their neutrality.”

In addition to working with large numbers ofIDPs, the agency introduced the new concept of ‘openrelief centers’—sites where vulnerable civilians re-ceived material help and protection in-country andwhere both armies agreed to respect UNHCR’s moral

Field protection.

“WE WERE ONE OF THE FEW INTERNATIONALORGANIZATIONS INVOLVED THROUGHOUT THE CRISIS. WE NOW HAVE A LOT OF CREDIBILITY. WE HELPED MAKE A DIFFERENCE.”

ON THE MEND

UN

HC

R/

R.W

ILK

INS

ON

/C

S/

LK

A•2

00

3

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

CS

/L

KA

•20

02

11R E F U G E E S

authority. The centers also obviated the aimof some civilians to flee further afield toIndia.

Tens of thousands of people took refuge in thesecenters though there were setbacks. The most infa-mous occurred at a center called Madhu when oneshell hit a church steeple, killing around 50 people.Critics questioned the very concept of the centers andtheir aim of short-circuiting another mass flight toIndia, but Janet Lim said, “For me the argument boileddown to the relative safety these centers offered whenthere was so much fighting and misery. We didn’t havethe luxury of guaranteeing absolute safety. A practi-cal solution was the key. They worked.”

ASSESSING THE SITUATIONAs peace talks continued through spring this

year, a visitor recently toured the war-affected areas.The fighting had generally been confined to the

north and east, the rest of Sri Lanka escaping thebrunt of the destruction. But war did periodicallyand violently shatter the surface calm of the port cap-ital of Colombo. President Premadasa was killed inone bomb attack in 1991; more than 100 persons werekilled and 1,300 wounded by a suicide bomber at thecountry’s Central Bank in 1996; and fourteen personswere killed and several planes destroyed in a similarattack on the international airport two years ago.

Amidst today’s big city bustle and renewed signsof optimism, physical scars are vivid reminders of therecent past: a line of gutted office buildings near thedowntown naval headquarters; police and army posts,heavily sandbagged and ringed with barbed wire,maintain a wary vigilance at the airport and otherkey buildings; a machine gun post perched high aboveone downtown hotel scans the ocean. At hotel recep-tion desks, collection boxes still urge clients:

“Help provide shelter for your brother

He has given his today for yourtomorrow.”

Most of an increasing number of tourists takingadvantage of cheap package tours and the relativecalm, head to the palm-fringed beaches south ofColombo, but the refugee story is due north. A nar-row two-lane trunk road hugs the west coast of SriLanka to Puttalam district, an area of sweeping, shal-low lagoons, salt pans, fishing boats and prawn farms.In more peaceful times this region, too, might be apopular tourist destination, but the only visitors inthe last 15 years were tens of thousands of civiliansfleeing the fighting further north.

The area’s population doubled with the new ar-rivals. Dozens of welfare and relocation centers wereestablished. Fleeing civilians were housed in mosques,schools and civic centers and private homes. Putta-lam is not a wealthy area, but like many areas

around the world inundated with displaced persons,it has displayed both a remarkable tolerance and re-silience in absorbing so many homeless civilians withso few resources.

Many of the displaced persons are Muslims fromthe Jaffna or Mannar regions further north who grav-itated here because of the large number of local co-religionists. Some have already returned home.Others are more cautious, waiting to see if the peacelasts, wondering whether to settle here permanentlyand what awaits them, if anything at all, ‘back

Lessons in avoiding sexual violence.

Children's playtime.

Emergency distribution.

Returning fishermen in Jaffna.

IT WAS ONE OF THE FIRST TIMES THE AGENCY BECAME HEAVILY INVOLVED WITH INTERNALLY DISPLACEDPERSONS IN SUCH LARGE NUMBERS.

Ãcontinued on page 14

UN

HC

R/

R.W

ILK

INS

ON

/C

S/

LK

A•2

00

3

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

CS

/L

KA

•20

02

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

CS

/L

KA

•20

02

12

Gregory Mariathas maynot have been quite ableto see the whites of thepilot’s eyes, but the

terrifying sight of the divingwarplane was still close enough forhim to read the lettering on itsfuselage.

“I was lying on my side, lookingup and was clearly able to read outthe aircraft’s identification marks inEnglish,” he said recently. “Then theplane released its bombs, rightabove my head it seemed at thetime. I was sprayed with sand anddebris. My hair and arms wereburned. But luckily the jungle was sothick there I escaped further injuryfrom the bombing.”

Mariathas had been riding in atruck to a timber depot in Tamil-controlled territory in northern SriLanka when a marauding warplanezeroed in on an apparent target-of-opportunity and swooped to attack.

The incident highlighted a grimnew reality for the small number ofinternational and local humanitarianofficials such as Mariathas involvedin Sri Lanka’s bitter civil conflict.

Until recent years, UNHCRofficials had normally worked on the fringesof war, helping refugees stabilize and rebuildtheir lives once they had escaped fromdangerous situations. Indeed, the refugeeagency began operations in Sri Lanka in 1987specifically to assist refugees to return fromIndia during one early interlude in the war.

But when the conflict re-ignited throughthe 1990s and into the new millennium, fieldstaff from UNHCR and a few other agenciessuch as the International Red Cross, weresucked inexorably into the eye of theinferno.

The refugee organization expanded itsoperations to assist not only refugees butalso hundreds of thousands of civilians

internally displaced on both sides of thefront lines, in government and LTTE-heldterritory. In the swirl of battle, it provided atenuous physical, legal and moral protectionregime for terrified families. The agencybecame a mediator with the army and theLTTE high command, its field staff constantlywalking the delicate tightrope between beingtrusted intermediaries or branded assuspected spies.

Staff and civilians became caught in thedeadly crossfire of major firefights, franticcalls being exchanged between field offices,Colombo, Jaffna and rebel headquarters toarrange a hasty cease-fire allowing trappedpeople to escape. Convoys ferried

desperately needed emergencysupplies across the front lines andthrough no man’s land into thebeleaguered rebel enclave. Vehicularmovement was subject to sporadicsurprise helicopter or warplaneattack.

Field personnel were isolated forweeks or months in rebel-heldterritory or on the Jaffna Peninsulawhere often their only physical linkwith the outside world was a perilousnight time boat ride between thepeninsula and the east coast port ofTrincomalee.

LOCAL BURDENThe heaviest burden in this little

reported and little known conflictinevitably fell on local staff whoendured two long decades of conflictand whose own families weresometimes among the very civiliansUNHCR was trying to help.

Amidst some of the worst fightingof the war in 1995, driver S.Koneswaran remembers “the mosthorrible moments of my life” as hetried to flee Jaffna town and find aplace of safety for his still trappedfamily. “Everyone was trying to leave.

There was a monstrous traffic jam,” heremembers. “We were just moving along inchby inch. There was shelling and firingeverywhere. So many people being killed andwounded. It took me two days to get out”and find a relatively safe area on the fringesof the battle.

Then he had to get back into Jaffna tobring his parents out. “The LTTE wouldn’t letme through their lines. I had to work my waybetween the two armies, cutting through therice paddies. I felt I was going to be shot byeither side any moment.”

At this time, government warplanes hadimprovised what to Koneswaran seemed likehomemade bombs, effectively large oil

R E F U G E E S

Life in the war zoneA grim new reality for humanitarians working at the center of Sri Lanka’s conflict

Tamil returnees in 1995.

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

CS

/L

KA

•20

02

UN

HC

R/

H.J

.DA

VIE

S/

CS

/L

KA

•19

95

13R E F U G E E S

barrels filled with explosives which wererolled out of slow flying Russian builttransport planes. “They spiralled down veryslowly,” he said. “We could track them asthey fell. During the day we could see themcoming and run away. It was not so bad. Butat night it was far worse, because we couldn’tsee where they would land.”

One evening, as he stood outside hishouse in Jaffna, he heard the ominous rumbleof ‘bombs’ falling. “I tried to jump a gate andhead for an air raid shelter” which everyonehad dug in their gardens, he said. He waslucky. He didn’t reach the bunker but thebomb exploded on the opposite side of thehouse, peppering the building but leavinghim unscathed.

Another UNHCR worker, T. Kandasamywas not so lucky. He was also standing nearhis home during other fighting when he washit in the stomach by shrapnel but herecovered.

UNHCR had established a series of so-called open relief centers for civilians—physically unprotected ‘safe’ sanctuarieswhich both sides had agreed to respect.Madhu in Sri Lanka’s northern Vanni regionwas the largest, at times housing manythousands of people, and driver S.Siebagnamam was helping to ferry suppliesto the trapped civilians there.

“At this time the army was retreating andthere was very heavy fighting,” he said. “Itwas raining heavily and it was very late atnight when a shell struck the Catholicchurch. I was some yards away. Even abovethe rain and the gunfire I heard the cryingand screaming. Everything was veryconfusing, but when I reached the building

there was blood everywhere. The walls weresplattered and elsewhere blood was flowinglike a river. The people were milling aroundterrified, but they couldn’t go anywherebecause there was fighting in all directions.”

It was one of the worst tragedies of itskind in the war and nearly 50 people died.

UNDER SIEGEAnd then there were the ‘routine’

incidents of life in a war zone—the lack ofcommunications with the outside world, thelack of information, of transport, petrol,food or medicine.

“Malaria was very bad at the time,”Gregory Mariathas remembers. “We all got it

repeatedly, sometimes when we were drivingin convoy. My colleagues would strap meinto a seat with a belt and we would carryon, with me shivering away.”

As one recent visitor was being driven toMannar Island, the local UNHCR driverremarked almost matter of factly: “That usedto be my home” pointing to a semi-destroyed building now in the middle of asmall military compound. “We had to get outduring the fighting. We have foundsomewhere else.”

Nimal Peiris had already fled the chaos toIndia during the early part of the war andthen returned home where he eventuallybecame an interpreter and protection clerkfor UNHCR on Mannar Island—a major exitpoint on Sri Lanka’s west coast for civiliansfleeing to India and the scene of majorfighting. Even today some stretches of theisland remain devastated.

He remembers the “motorcycle incident”vividly. He was riding with a colleague on aUNHCR motorcycle when two armed LTTEfighters stopped them and one demandedthe bike. “I refused and told them ‘If youwant this bike then shoot me,’” he said. “For45 minutes he held a pistol to my head,

arguing. Eventually the second man freed us.”The cycle was donated to a local

organization, but the persistent guerrillaeventually commandeered it. Three monthslater Peiris again saw the man and themotorcycle.

After a formal complaint, the machinewas returned and the man arrested by hisown high command for the robbery andother crimes.

Even minor successes like that werewelcome in the chaos of war. B

“THE WALLS WERE SPLATTERED AND ELSEWHERE BLOOD WAS FLOWING LIKE A RIVER. THE PEOPLE WERE MILLING AROUNDTERRIFIED, BUT THEY COULDN’T GO ANYWHERE BECAUSE THEREWAS FIGHTING IN ALL DIRECTIONS.”

War destruction.

14 R E F U G E E S

home.’ Canthey believe the politi-

cians’ promises? Should theirchildren’s education come first?

DASHED HOPESLike all uprooted peoples, each individual relates

heart-rending stories of violent upheaval, the hope ofimmediate return and then the despair of long exile.Fifty-seven-year-old Abdul Hameed Badurdeen waspart of Jaffna’s thriving Muslim community with ahome on the main thoroughfare, Moor Street, when

one day in October 1990, the community was de-stroyed. All the Muslims were summoned to a localschool, given just two hours notice to leave and withvirtually no possessions or money, bused into exile.

“We were told we might be back in two days,” herecalls ruefully. “Thirteen years later and we arestill not home.” Refugees worldwide are often told bytheir tormentors or wrap themselves in self-delusionthat their exile will be fleeting, but the reality is of-ten very different.

Abdul Hameed Badurdeen and his family wan-dered the country as nomads for years before set-tling in Puttalam. Since the cease-fire, communitymembers have returned to Jaffna on exploratoryvisits but as one said, “What would you do if you re-turned and found a tree growing in your old livingroom and the rest of the house destroyed?”

There is a constant tug-of-war in the gut of alldisplaced persons between hope and fear, a deepseated desire to return to the ancestral hearth or toturn one’s back on a dreadful past and begin life afreshsomewhere else.

Often the wanderlust is strongest in the young, but21-year-old Liyakath Aikhan Mohammed Aslam isin no doubt: “I was seven when I fled. I can’t even re-member anything about my own village. But I will beso proud when I return there,” he said. When will that

be? “Oh, in a few days. Or maybe in a few years.”Followed by a fatalistic shrug.

For now he lives in Kuringipitty, a tiny hamletof nearly 200 displaced persons at the head of a

lagoon. He is clearly very bright and clever, butbecause of his nomadic existence, he has had

no formal education and cannot read or write.His future looks bleak even if the peace be-

comes permanent.Several homes in Kuringipitty burned down re-

cently, and on this visit a UNHCR team drops offemergency supplies—plastic buckets, sleeping mats,blankets. Each package is worth a little over $40, butfor people with nothing, even this modest help is price-less.

Protection work—the core of UNHCR’s man-date—is both labor intensive and basic. It may take afull day or even longer for a team to visit a few peoplein an isolated community.

A check list: Do they have basic shelter, water anda little medicine? Are they being harassed by the lo-cals or military? Has the school reopened? Is thereany work or income support? Help may be needed to

resolve land and home owner-ship problems. Ensuring thatif people do go home, they do sovoluntarily and once there en-joy their basic human rights.Has the only access road to thevillage destroyed during thefighting been repaired? Havethere been any recent inci-

dents of child abductions? If UNHCR officials can-not help directly, liaise with local government offi-cials or another organization to provide a clinic orschool books. One thousand and one mundanetasks.

EYE OF THE STORMMoving north, the signs of war and its destruc-

tive aftermath proliferate. When the guns fell silentin late 2001, the LTTE controlled a 100 kilometer

“THE REPATRIATION OPERATION IN SRI LANKA SKATES ON A GLASSY POND, AND THE PIROUETTES AND ARABESQUES THAT WE GO THROUGH BEAR NO RESEMBLANCE TO THOSE IN ANY OTHER UNHCR PROGRAM.”

Ã

UN

HC

R/

R.W

ILK

INS

ON

/C

S/

LK

A•2

00

3

Cleaning up after the guns fall silent

It was surely one of the most bizarresights of the war. “I was in Mannar districtwhen I saw a small and rather strangeherd of cattle,” recalls Luke Atkinson of

the Norwegian People’s Aid group. “On closerinspection, I noticed that most of the cowswere three legged. They had each had one legblown off by mines.

“The farmer had kept them alive by bindingtheir wounds but he appealed to me, ‘Whatcan I do with these three-legged cattle? Whatcan I do?’”

Atkinson is a de-mining consultant helpingto train a cadre of 600 field staff for the Hu-manitarian De-mining Unit (HDU), an organi-zation responsible for cleaning up the TamilTiger-controlled areas of Sri Lanka. The armyand other international groups are workingin government-controlled areas.

Regions emerging from long conflicts—Cambodia, the Balkans, Angola, Afghanistan—all face a lingering nightmare legacy of war in-cluding minefields, booby traps and unex-ploded military ordnance such as bombs andshells.

And though the encounter with the crip-pled herd of cattle had an almost tragicomicelement, it underlined in a peculiarly poignantway a similar physical threat facing Sri Lanka’sreturning civilians, their livestock and theirability to rebuild shattered local communities.

The army laid more than one million minesduring the two-decade long war, the LTTE asmaller but unknown number. The military re-cently agreed to share with civilian de-minersprecise maps of their minefields, a moveAtkinson said would be invaluable in reducingthe inevitable number of casualties and

speeding up de-mining activities.The consultant said he was already im-

pressed with the discipline shown by many re-turnees who had moved back into their oldhomes, but had resisted the temptation toventure into uncleared and potentially lethalfarmland just a few yards away.

RISKY WORKStill, the situation remained highly danger-

ous, both for the mine clearers and civilians.One six-man team was recently at work on

the shoulder of the country’s main north-south artery, the A9 truck road. To the un-trained eye, its method of operation appeared

basic, even primitive and fraught with risk.Each de-miner was dressed loosely in flimsyrubber wellingtons (gumshoes) which offer lit-tle protection against unexploded material,flak jacket, visor and white hardhat.

Their gear was recently upgraded, accord-ing to the team leader directing operationsthrough a bullhorn as the men spaced them-selves at 15 meter intervals and began work.Traffic rumbled by a few feet away. A beauti-fully dressed woman in heels walked daintilyby, seemingly unconcerned about any immi-nent surprise.

The de-miners were each armed with anunsophisticated, long-handled and rustinggarden rake with which they vigorouslycombed and then cleared the underbrush. Theleader insisted to a skeptical visitor that therake strokes were too light to trigger any lurk-ing mines, but would merely uncover them af-ter which they could be detonated on thespot or made safe and removed.

Each 30 minutes the teams were changedto allow the men to rehydrate with huge gulpsof water. In one day each de-miner clearedjust a few square yards. Each earned 7,000 ru-pees ($80) per month, a good salary in SriLanka, and the work will certainly last for sev-eral years.

But even though the problem here may notbe quite as dangerous as in places like Angola,the toll is still enormous. An estimated 1,000persons were killed or injured since civiliansbegan returning home in large numbers. In oneparticularly tragic incident a de-miner blewhimself up when he mistakenly sat on a minewhich had only been unearthed a few minutesearlier. B

Mine clearing and mine awareness inSri Lanka's Vanni region.

15R E F U G E E S

UN

HC

R/

R.W

ILK

INS

ON

/C

S/

LK

A•2

00

3

W O R L D

16

67

W O R L D

7The worst humanitariancrisis in the western

hemisphere continued tointensify into the new year,particularly around Colombia’sborder areas, even though thegovernment held negotiationswith some paramilitary andrebel groups on demobilizationand peace talks. In the nearlyfour decades of conflict, anestimated two million civilianswere displaced within thecountry. UNHCR has helped bybeginning to register thesecivilians.

8There are more than 40 million uprooted personsaround the world—refugees, asylum seekers, civilians

internally displaced within their own countries. More than half thistotal—around 20 million people—are children and youths—the groupaged between 13 and 25. This year’s World Refugee Day on June 20will celebrate these young people—not only their special problems,such as these deaf Sudanese refugees, but also their exceptionalpromise if given an opportunity to escape a life in exile and obtainan education.

6It was a case of exchangingone hell for another. As

widespread unrest continued in theWest African state of Côte d’Ivoirethis spring, more than 80,000Liberian refugees and Ivorian citizensfled westwards for safety in, of allcountries, Liberia. Meanwhile, as athree-year insurgency intensified inwestern Liberia itself, a new wave ofrefugees poured into the nextcountry, Sierra Leone, which itself istrying to recover from a decade-longcivil war. In the last two years around60,000 Liberians sought sanctuary inSierra Leone in a dizzying round ofrefugee musical chairs.

W E S T A F R I C A

4 Rwanda’s genocide in 199world’s worst killing field

exodus of more than two million pnation. In the intervening decadethe country. But efforts are now uhomecoming. An estimated 60,00refugees in surrounding countriepeople will voluntarily return homrangements should be agreed wit

R W A N D A

5The war in Angola lasted for a quarter ofa century. Hundreds of thousands of person

were probably killed in the conflict. More thanfour million persons were ripped from their townand villages, seeking safety either inside theravaged African nation or in surroundingcountries. Many people have already gingerlybegun returning home (picture shows a feedingcenter) following a cease- fire signed last yearbetween the government and UNITA rebels andas in Sri Lanka, this trend is expected to continuethis year… as long as the guns of war remain silen

A N G O L A

W O R L D

C O L O M B I A

UN

HC

R/

B.P

RE

SS

/C

S/

KE

N•1

99

9

UN

HC

R/

N.B

EH

RIN

G/

CS

/L

BR

•20

03

UN

HC

R/

C.S

AT

TL

EB

ER

GE

R/

CS

/A

GO

•19

94

UN

HC

R/

L.T

AY

LO

R/

CS

/T

ZA

•20

02

UN

HC

R/

P.S

MIT

H/

CS

/C

OL

•20

02

© E S A 1 9 9 5 . O R I G I N A L D A T A D I S T R I B U T E D B Y E U R I M A G E

D N E W S

17

4

5

2

1

D N E W S

3It will be the largestever refugee

resettlement programundertaken out ofAfrica. After finalvetting, the first of around12,000 so-called SomaliBantu people will begin ajourney out of exileshortly—from a refugeecamp in northern Kenya tonew homes across thebreadth of the United

States. The Bantu, a distinctive group of people who wereoriginally slaved from southern Africa in the 18th and19th centuries to Somalia, fled when that countrycollapsed in the early 1990s. For a decade, the U.N. refugeeagency tried to find them refuge in their ancestral homes,but when those efforts failed, the United States agreed toaccept them for resettlement as a special group.

K E N Y A

2After nearly two decadesof civil war, a cease-fire to

end one of the world’s longestconflicts continues to hold. Morethan a quarter of a millioninternally displaced persons andhundreds of refugees havealready returned home followingan agreement signed in early2002. The pace is expected tocontinue through this year withrefugee returns from Indiagaining momentum. Anestimated 65,000 persons werekilled in the conflict, more thanone million people were uprootedand hundreds of villages andtowns destroyed.

S R I L A N K A

1After a breakbecause of the harsh

winter conditions, thelarge-scale repatriation ofAfghan civilians back totheir homes has restarted.UNHCR expects to assistaround 1.2 millionrefugees and a further300,000 internallydisplaced persons, helpingthem to reconstruct theirhomes and restart theirlives. It has asked for abudget of $195 million.Last year, more than twomillion people returned.

A F G H A N I S T A N

94 triggered not only one of theds in modern history, but also a masspeople from that landlocked African

e, the majority of civilians returned tounderway to finalize the Rwandan00 Rwandans continue to live ases including Zambia where some 5,000me in the coming months. Similar ar-th other nations throughout 2003.

fs

ns

,ent.

3

UN

HC

R/

B.P

RE

SS

/C

S/

KE

N•2

00

2

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

CS

/L

KA

•20

02

UN

HC

R/

N.B

EH

RIN

G/

DP

/A

FG•2

00

2

18 R E F U G E E S

deep swath of jungle, east to west, known as the Vanni,isolating from the rest of the country the vital gov-ernment-controlled northernmost Jaffna Peninsula,the crown jewel which the two sides had duelled over.

The A9 trunk road cleanly bisects the north of theisland, running south to north, slicing through thegovernment front lines into the heart of the Vanniregion and snaking into Jaffna town. It had beendubbed the Highway of Death during the war andeven in more peaceful times is a useful barometer ofthe country’s health.

The military tried to choke this rump Tamilstate of Vanni during the war by imposing both a mil-itary and economic blockade on the region, but

some emergency humanitarian supplies for thecivilian population were allowed through. Field of-ficer Kilian Kleinschmidt recalled the extreme ten-sion and danger of running a convoy through no man’sland between the opposing armies in 1997:

“Boy, it’s hot—45 or 50 Celsius, but who cares? Whodares to breathe anyway?

Pitch dark—there is the abandoned farm half way; thelittle Hindu shrine where truck drivers pray during the daycrossing no man’s land.

The palm trees with their tops shot away by artillery.Big Dany driver is so quiet, hiding behind his wheel

and driving so slowly—crawling, inching. Waiting for thebang which will tell us, for a fraction of a sec-ond, that the mine has got us and we willnever make it home.

No time to write a last letter; no time to cryand scream. Advancing carefully—500, 400,300, 200, 100 yards. Made it all the way backto where we had started. Totally wet. Wrecked.

Greeted by this little black clothed fighter atthe rebel checkpoint.

My decision to try to get back from rebel territory throughthe front lines. Didn’t my friend the brigadier promise tolet me ‘in’ even at night?

Didn’t I tell my friend, the rebel checkpoint comman-der, that we would be allowed to cross by the army?

Didn’t he reply that if our convoy crossed there wouldbe no return—he would mine the no man’s land for the night,attack any moving object?

The army didn’t open the barrier. We had to returnthrough no man’s land.

The mine didn’t rip us into little chunks. They didn’tshoot.

Safety.”

PROGRESSWhen the A9 was reopened for civilian traffic

early last year, it was the most tangible sign ofprogress. The embargo on such sensitive items ascement has been gradually lifted and prices in the en-clave, once prohibitive for virtually everything, arenow on a par with the rest of the country. Traffic vol-ume has increased and modern Japanese trucks joustwith World War II vintage Morris Minors and Austincars for bragging rights on the crumbling highway.Burned out armored personnel carriers still litter theshoulders but de-miners in rubber galoshes and vi-sors sweep for mines and unexploded ordnance withgarden rakes. An ambitious plan is on the drawingboards to rebuild this vital artery.

But to travel on the A9 one enters a twilight zonebetween war and peace and two nations, the Sinhaleseland of Buddhists and a Tamil-controlled territory ofHindus. The two armies are on stand down but eyeeach other warily. The LTTE has established its ownpolice force, court system and tax authority, thoughmany civilians say the collection of taxes amounts to

A Sinhalese returnee farmer.

“WE WERE TOLD WE MIGHT BE BACK IN TWO DAYS. THIRTEEN YEARS LATER AND WE ARE STILL NOT HOME.”

ON THE MEND

UN

HC

R/

R.W

ILK

INS

ON

/C

S/

LK

A•2

00

3

19R E F U G E E S

nothing more than a crude shakedown. The Vannieven operates in a different time zone, 30 minutes be-hind national time.

In a great swirl of movement, a partial reorderingof the civilian landscape, tens of thousands of dis-placed civilians have returned to the Vanni region orhave left it for the densely populated Jaffna region ashave other groups from Colombo and Puttalam.

Off the main highway, monsoon rains have washedaway bridges and rural roads. Therehas been no maintenance for twodecades. The jungle encroaches oneverything.

Deep in the interior at Murippuvillage, protection officer Kahin Is-mail checks on the progress of nineMuslim families who returned lastyear. The news is good. There hasbeen no harassment. Tamil neigh-bors loaned one family money to buynets and a fishing boat and an eldertells visitors, “Even if I die, I will diehere happily.”

“So far,” according to Ismail “mostof the returnees are people with noth-ing to lose. Those with businesses orhomes elsewhere are holding back,waiting to see what happens. Butthe authorities here are handling thereturnees with kid gloves.” He added,“I spend maybe 50 percent of my timemonitoring civilians like today. Therest involves helping to solve prob-lems like land disputes. Soon UN-HCR will also begin monitoring a gov-ernment program to assist families re-turning to their original homes with cash grants.

Further along the rutted track lies Mullativu. Gov-ernment soldiers and rebels fought one of thebiggest pitched battles of the war herein the mid-1990s. Hundreds werekilled. The town is still a wreck. Tworusting freighters captured by theLTTE and sunk by governmentwarplanes scar the beach. It may takeyears to breathe new life into thistown.

In contrast, Kilinochchi, a non-descript center sitting astride the A9,which has become the LTTE administrative capi-tal, is bustling with energy. Offices are being rebuilt,shops opening and returning civilians cobbling to-gether simple huts on the outskirts of town.

Heading towards Jaffna, the A9 has become a dif-ferent kind of battleground for the hearts and mindsof the country’s civilian population. Every few kilo-meters, gaudy, hand painted billboards extol the brav-ery of Tamil martyrs though the accompanying En-glish translations are somewhat convoluted:

“In the entrance of enemyThe life in prison will get lightnessIf we are strong

In the earth without barriersBraveness blooms when we left.”

Across another front line and into army-controlledterritory and a black and yellow banner proclaims

“Highway for Unity and Peace.” At every war-scarredbridge, a government notice instructs the public thatit had been destroyed by Tamil fighters. Both sides are

keeping their options open, reminding their respec-tive publics of the sacrifices they made during the war.

ULTIMATE PRIZEOnce the jewel of Tamil culture, the peninsula was

the ultimate prize, the center of the military stormwhere many thousands of persons died in set piecebattles and the bulk of the civilian population up-rooted from their homes.

Much of the mainland, lagoons and islands remain

UNHCR is upgrading the level of psychiatric treatment available to returning civilians.

A LONE SAILING VESSEL ANCHORED AND UNLOADED PILES OF RIPEMANGOES, SUITCASES, FISHING NETS, A BICYCLE, AND A LOUDLYBLEATING BLACK GOAT. IT WAS THE FIRST TIME CIVILIANS HAD BEENALLOWED TO SAIL BACK TO THEIR OLD HOMES.

Ãcontinued on page 22

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

DP

/L

KA

•20

02

20

Afew bloodstains in the dust,household belongings scatteredaround the little mud house 200yards from the main junction in

Mankulam. A plastic wall clock smashed, indi-cating the time of death of the old man whowas killed instantly by shrapnel from a shellwhich hit this strategic junction in one of theso-called ‘uncleared areas’ in the north of thecountry.

Never mind: another useless death, morehatred and more displacement as hundreds offamilies leave the same night on overbur-dened ox-carts or little tractors, past ‘heroescemetery’ where rebels have buried theirfighters, and into the jungle which offers a lit-tle cover, water and snakes. Don’t bother

building another hut. Some civilians out ofthe hundreds of thousands who have beendisplaced, have done this 10 times, 20 timesalready, but the war always catches up withthem and repeats the cycle.

It begins with a peaceful village. Butthen there is the dreadful intrusion: bom-bardment, attack, scare, flight; finding anew place, building a house, starting a gar-den, bombardment, attack, scare, flight…The shelling of Mankulam is just a minor in-cident on the wider stage of an unendingwar between government and rebel forces.Why should we even bother about this for-

gotten conflict? But then there are no otherwitnesses; maybe 10 international staff work-ing in the rebel-controlled area. So we feel re-sponsible—we are responsible—for protect-ing the innocent, constructing a credible ac-count of the situation, trying to maintain thedelicate balance of trust with both sides, con-vincing the commanders perhaps that theirmilitary operations could be driving the civil-ians-caught-in-the-middle into the oppositecamp. We owe it to the dead old man ofMankulam and especially the survivors.

Once back in government territory, I urgemy army interlocutor, a brigadier, that bombssuch as those which fell on Mankulam do notnecessarily win hearts and minds. Withouttrying to interfere with military operations,

couldn’t we agree that the army will advancealong the main road and we can group civil-ians in the jungles left and right? Yes we can.But can we for our part guarantee there willbe no rebel cadres among these families? Nowe can’t. The dialogue continues.

Later, there is a similar exchange with offi-cials of the rebel LTTE: on civilian rights versus‘the cause’ and military strategy, how to getcivilians out of the way of the fighting, free-dom of movement. I sit on the same sofa set, afamiliar prop which has been transported withthe constantly moving war headquarters fromplace to place in the rebel enclave duringthese endless discussions. We disagree onmany things but do concur jokingly that whenpeace breaks out the excellent rebel logisti-cians will easily be able to find new employ-ment.

Each side is kept closely informed aboutthese meetings ‘on the other side’ of the frontlines.Transparency is our only weapon in hold-ing their trust and allowing us to continueworking.

CROSSING THE LINEThe Captain of Ramya House, the last mili-

tary checkpoint between the government-held territory and rebel-controlled Vanni re-gion, is our ‘most beloved enemy.’ We getalong… kind of… but his job is to make it as dif-

R E F U G E E S

Death, despair… and then hopeFor the handful of humanitarian officials working on bothsides of the Sri Lanka conflict during the late 1990s, lifewas a daily, dangerous tightrope, as they tried to convincesoldiers and rebels alike to respect a beleaguered civilianpopulation, at the same time maintaining the trust ofsuspicious commanders, negotiating the front lines withemergency supplies and crossing a scary no man’s landwhere anything could happen. When KKiilliiaann KKlleeiinnsscchhmmiiddttwas a senior field officer in the northern town of Vavuniyain 1996-97, the war seemed so hopelessly bogged down,even aid officials wondered why they were there.

The rusting weapons of war.

UN

HC

R/

R.W

ILK

INS

ON

/C

S/

LK

A•2

00

3

21R E F U G E E S

ficult as possible for humanitarian workersand their emergency supplies to reach the en-clave. We meet almost every day and the rou-tine is always the same. Verification of per-mits. The physical scrutiny of goods. Yet an-other piece of paper for one thousandblankets, 10 bales of used clothes and cookingutensils. Other permits for new tires, one bagof cement and one jerrican of fuel for the UN-HCR field office.

Is he in a good mood? An enthusiasticmovement of the head from right to left meansyes—a hesitant shaking means that we will see.No movement at all and some frowns on hisforehead mean a clear no! A telephone call tothe Brigadier or Headquarters in Colombo maymean no departure today. Come back tomor-row at which time you will need a new move-ment permit from the capital.

Will he order the used clothes to be sortedby individual colors? Camouflage is refused.Ten bottles of shampoo are confiscated. Theshampoo could be used as engine oil. AA sizedbatteries are verboten, since they could be in-serted in mines. The one bag of cement for anew UNHCR base camp? Not today, despite apermit. It could be used to construct a rebelbunker.

A body being repatriated from Sweden in asealed coffin must be searched for restricteditems and weaponry—by hand and metal de-

tector. The checking officers visibly recoil andcover their noses as they open the zinc cof-fin—but restricted items have been discov-ered before in the most unlikely places.

The convoy proceeds cautiously into the2000-yard no man’s land between the militaryand rebel checkpoints. Blue flashlights revolvefrom the vehicles roofs, alerting everyone toour presence.

The lid of the coffin from Sweden bounces

open. Bunkers built from smashed palm trees,mud and sand line the route. There are sol-diers dressed in flip-flops, green t-shirts andboxer shorts, rifles thumping against theirbacks. Heavy rails which formed the country’smajor rail link which were ripped up to act ascrash barriers, must be physically manhandledaside. A government convoy of 40-50 truckswith essential commodities moves through. Itis a true oddity of this war that even as bothsides try to kill each other, Colombo has de-cided to keep feeding the rebel pocket, civil-ians and LTTE fighters alike.

The transfer of dead soldiers and rebels isoften made in this dangerous no man’s land,but sometimes even this poignantly tragic actof kindness can have a grisly end. A truckloaded with corpses from a recent battle ar-rives. Access to cross the front lines is deniedbecause the arrival of so many dead bodieswould be an acute embarrassment and publicrelations disaster. Even the checkpoint com-mandant has tears in his eyes. The bodies will

find no permanent resting place, but will sim-ply be listed as missing in action.

A seemingly endless and hopeless war con-tinued on its way.

Epilogue: One paragraph appears in a Euro-pean newspaper about the peace process in SriLanka. There is also a 30-second television re-port. My LTTE ‘colleagues’ shake hands with agovernment delegation in a process brokeredby the Norwegians. But didn’t we discuss this in1996 and 1997? and the idea went nowherethen. But good news at last. B

A UNHCR food convoy in no man’s land.

“WHY SHOULD WE EVEN BOTHER ABOUT THIS FORGOTTEN CONFLICT? BUT THEN THERE ARE NO OTHER WITNESSES. WE ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR PROTECTING THE INNOCENT.”

UN

HC

R/

B.C

LA

RA

NC

E/

CS

/L

KA

•19

91

22 R E F U G E E S

in ruins, heavily fortified with bunkers, berms andbarbed wire.

Professor Thaya Sumasundaram of Jaffna Uni-versity’s Faculty of Medicine, says the psychologicaldamage suffered by the population may be evengreater. “Where are we on the ladder compared with,say, Cambodia or Bosnia?” the professor, whoworked extensively in Cambodia, asked rhetorically.“It became very bad here and had the war carried onmuch longer we would have hit rock bottom—just likeCambodia.”

He added, “The ages-old social net is no longer thereto protect society. The role of women has changed dra-matically. Elders have lost their legitimacy and youngpeople their inhibitions. We can’t go back to the oldways, that’s for sure, but if there is one glimmer of hopeit is that some important structures have not beencompletely wiped out.”

But as the crush of returning people mounts, thearmy has gradually reduced the size of its formerlyout-of-bounds high security zones. Some recon-struction, including work on a sparkling white library,is underway. Civilian flights have resumed to the onceisolated pocket. Ferry services may get underway soon,facilitating the return of refugees from India.

It is a modest beginning. Moor Street, the home ofnearly 4,000 Muslim families before the war, includ-ing Abdul Hameed Badurdeen quoted earlier in this

report, remains gutted and apparently empty.One man poked around a ruined home. He told a

visitor during a chance meeting he had returned thatvery day to assess the damage and decide whether tobring his family back. Attracted by the conversa-tion, other Muslims emerged from the shadows andsought reassurance from UNHCR protection offi-cer Rafael Abis about the future.

“When we came here a month ago, there was no ac-tivity at all. Nothing. Nobody,” he said. “This is progress.It is slow, but it is progress.”

There was another encouraging encounter atManddaitivu village on one of the outlying areasthe same day. While Abis discussed with recentlyreturned Catholics the possibility of removing rollsof barbed wire from the beaches, a lone sailing vesselanchored and unloaded piles of building poles, ripemangoes, suitcases, pots and pans, kettles, fishing nets,a bicycle and finally a loudly bleating black goat.

It was the first time returning civilians had beenallowed to sail back to their old homes rather than go-ing via the heavily guarded highway.

“Another small first,” said Abis. As if to empha-size how peaceful and even ‘normal’ the situationappeared, off duty sailors enjoyed a game of cricket inthe afternoon heat nearby, the lazy thwack of a ballon bat making war and destruction at that momentseem a long way off. B

Rebuilding Jaffna.

OFF THE MAIN HIGHWAY, MONSOON RAINS HAVE WASHED AWAY BRIDGES AND RURAL ROADS. THERE HAS BEEN NO MAINTENANCE FOR TWO DECADES. THE JUNGLE ENCROACHES ON EVERYTHING.

ON THE MEND

UN

HC

R/

R.W

ILK

INS

ON

/C

P/

LK

A•2

00

3

UN

HC

R/

J.S

TE

JSK

AL

/C

S/

RW

A•1

99

9

GrowingPAINS

23R E F U G E E S

GrowingPAINS

Young people should be preparing for adulthood;instead, they are trapped in the limbo of exile

Rwanda: lookingto the future.

24 R E F U G E E S

Golden childhood memories have crum-bled into nightmare. If prompted, 24-year-old Arami remembers her family’s“lovely villa, and as a young girl playingwith my friends in the small beautiful

garden” in Somalia. Her recent memories, however,are dominated by thoughts of “my father being killedin a massacre” during the country’s civil war and hersubsequent flight into exile. “We had to run away inour pyjamas. We couldn’t think of taking anythingwith us.”

Teenagers Bolleh and Emmanuel recall singingand dancing with their friends on the beaches aroundMonrovia, the capital of Liberia, selling jeans in adowntown shop and just ‘hanging out’ as youngstersdo. Until they were kidnapped by one of the country’srebel groups as child soldiers, brainwashed that“Death is better than life” and forced to both fight andsometimes execute opposing guerrillas in cold blood.

Layla was happiest visiting “a little mosque where Icould speak with God alone and in peace. It had beau-tiful, gold-framed windows through which I could see

AT A TIMEWHEN THEYSHOULD BEHONING THEIRSOCIAL,EDUCATIONALAND SEXUALPERSONAS,THEY FINDTHEMSELVESCAUGHT IN ATERRIBLELIMBO OFEXILE...IGNORED,EXPLOITED ORCONDEMNEDTO A LIFEWITHOUTHOPE.

©S

.SA

LG

AD

O/

AG

O•1

99

7

25R E F U G E E S

the mountains and the running water.” The 13-year-old had been born in exile in Iran after her family fledneighboring Afghanistan as that country collapsed.But there would be no happy homecoming for thisyoungster and her family. Fearing they might beforcibly deported back to Afghanistan from theiradopted homeland, they moved instead to the westand eventually ended up in Greece where they soughtasylum.

Fate has played a particularly cruel trick on Arami,Bolleh, Emmanuel and Layla and millions of others

like them around the world.At a critical time of ‘growing up’ when they should

be honing their social, educational and sexual per-sonas ready for an adult future, young people findthemselves caught instead in a terrible limbo of exilewhere they can be alternately ignored, exploited orcondemned to a life without hope.

GLOBALLY DISPLACEDThere are more than 40 million uprooted persons

around the world—refugees, asylum seekers, civilians

Youngsters wereforcibly recruitedto fight in Angola'squarter century civilwar, but educationis the way forward.

U N I C E F / G . P I R O Z Z I / B W / A G O • 1 9 9 6

26 R E F U G E E S

internally displaced within their own countries andother groups.

More than half of this global total—around 20 mil-lion people—are children and what is loosely termed‘young people’, though the exact number of this lattergroup is difficult to accurately assess. The very con-cept of ‘youth’ varies according to national culturesand different organizations set arbitrary age limits todelineate the boundaries between children, youthsand adults.

In general, UNHCR considers anyone between theages of 13 and 25 to be young refugees. To highlight notonly their special problems, but also their exceptionalpromise, the agency dedicated this year’s WorldRefugee Day on June 20, to refugee youth and a seriesof special concerts, cultural festivals, public debatesand religious services around the world were planned.

All uprooted peoples are in need of assistance. But

as their numbers grew inexorably in the decades fol-lowing World War II, it became increasingly clear toagencies like UNHCR that particular groups such aswomen, children or the elderly, needed different typesof help within a general humanitarian framework.Special programs and international conventionswere established to meet those needs.

There were no such particular accords for youthwho, instead, were covered by more general programsand treaties such as the 1951 Refugee Convention, its1967 Protocol, the 1989 Convention on the Rights ofthe Child and various optional protocols and UN-

HCR’s own Policy on Refugee Children.Despite this patchwork protection, it has become

increasingly clear that these young people also facedparticular pressures—physical, educational, econom-ic and sexual—which needed to be specifically ad-dressed.

CHILDREN OF WAROne of the worst fates befalling disenfranchised

young people is their forcible recruitment as child sol-diers. The U.N. estimated that more than 300,000 un-derage youths, most of them between 15 and 17, cur-rently are fighting in some of the world’s most brutalwars, undergoing indescribable experiences. In SierraLeone’s recent civil war teenage soldiers were some-times forced to kill their own parents and neighbors aspart of gruesome indoctrination ceremonies or to de-liberately mutilate other victims. Young females werereduced to the role of sex slaves, servicing dozens ofpartners.

These youngsters became little more than highlydangerous zombies who, even if they survived andthen escaped the war, were in need of months or yearsof specialized care.

In addition to international political pressure onwarring factions, regular armies and rebels alike, toeliminate underage recruitment, agencies through-out the humanitarian spectrum also began psycho-logical, family reunion, educational and vocationalprograms to try to salvage damaged victims like 15-year-old Jonathan in Sierra Leone.

“They gave me guerrilla training. They gave me agun,” the still traumatized youth explained in a mono-tone during his rehabilitation program. Did he takedrugs? “Yes.” Did he kill people? “Lots.” Was that wrong?“It was just war, what I did then. I only took orders.” Andwhat does he want to do now? Chillingly his responsewas, “Join the military. I know what to do there.”

Forcible recruitment and sexual slavery may be ayoung girl’s worst nightmare, but even if they escapethat fate the threat of other sexual violence is alwayspresent in a refugee climate where social and familystructures have collapsed. Girls are seen as ‘easy tar-gets’ in refugee camps, becoming victims of outrightrape or coercion. Some are forced into prostitution orto bestow ‘favors’ on powerful men such as camp lead-ers or teachers, merely to survive.

WIDESPREAD HARASSMENT“Forty to 60 percent of sexual assaults are against

girls below the age of 16,” says Linnie Kesselly, a com-munity services officer in Uganda. “Girls and womenare deceived and sexually used because they don’tknow their rights and because they can’t sustainthemselves financially.”

Like 22-year-old Mariama who admitted to sleep-ing with a string of men after being ditched by her reg-ular boyfriend, sometimes for one night, sometimesfor a couple of weeks, for as little as five Liberian dol-

Unexploded ordnance is a particular danger to youngsters including this Sri Lankan returnee who was wounded by a land mine in his garden.

“IF YOUNGPEOPLE ARELEFT ONSOCIETY’SMARGINS, ALLOF US WILL BEIMPOVERISHED.”

UN

HC

R/

R.C

HA

LA

SA

NI/

CS

/L

KA

•20

02

27R E F U G E E S

lars (10 cents). “I never wanted that life,” she said withresignation, “ but there is no other way to survive.”

When 18-year-old Musu from Sierra Leone ap-plied for a school scholarship, a teacher on the inter-viewing committee asked her to be his girlfriend. “Itold him I didn’t want to be his friend,” she remem-bers. “I never did get that scholarship.”

In such a threatening and permissive environmentlacking all normal social constraints, health problemsproliferate. Sexually transmitted infections, includingHIV/AIDS, have become commonplace among bothsexes. Young women face early and unwanted preg-nancies, unsafe abortions or high levels of maternaldeaths and, in some parts of the world even in super-vised camps, ongoing genital mutilation.

A variety of approaches has been adopted to try tocombat sexual exploitation and the resultant healthproblems.

One common sense approach has been to improvebasic security with better housing, lighting and moreaccessible public amenities in camps which mayhouse tens or hundreds of thousands of people, reduc-ing the opportunity for rape. Girls are educated aboutboth the physical and health dangers as are key malefigures such as camp leaders who may not appreciateor be willing to tackle the problems faced by theirwomenfolk. The more economically self-sufficientyoung women also become, having a skill or a trade,the less vulnerable and dependent they are to ex-ploitation.