Social identity complexity, cross-ethnic friendships, and intergroup attitudes in urban middle...

Transcript of Social identity complexity, cross-ethnic friendships, and intergroup attitudes in urban middle...

Social Identity Complexity, Cross-Ethnic Friendships, and IntergroupAttitudes in Urban Middle Schools

Casey A. Knifsend and Jaana JuvonenUniversity of California, Los Angeles

This study investigated contextual antecedents (i.e., cross-ethnic peers and friends) and correlates (i.e., inter-group attitudes) of social identity complexity in seventh grade. Social identity complexity refers to the per-ceived overlap among social groups with which youth identify. Identifying mostly with out-of-school sports,religious affiliations, and peer crowds, the ethnically diverse sample (N = 622; Mage in seventh grade = 12.56)showed moderately high complexity. Social identity complexity mediated the link between cross-ethnic friend-ships and ethnic intergroup attitudes, but only when adolescents had a high proportion of cross-ethnic peersat school. Results are discussed in terms of how school diversity can promote complex social identities andpositive intergroup attitudes.

Social self-definition becomes increasingly impor-tant during adolescence, as youth begin to under-stand the significance of group membershipsto themselves and others (Harter, 2012; Sani &Bennett, 2004) and strive to understand with whichgroups they align themselves (Brown, 1990; Cros-noe, 2011; Newman & Newman, 1976). Most ado-lescents identify not only with groups that areascribed or assigned (e.g., gender and ethnicity),but also with groups that are chosen (e.g., extracur-ricular activities and clubs; Aboud, 1988; Bernal,Knight, Garza, Ocampo, & Cota, 1990; French, Seid-man, Allen, & Aber, 2006; Maccoby, 1998; Phinney,1990; Tanti, Stukas, Halloran, & Foddy, 2011). Inaddition, close friendships, cliques, and crowdsbecome especially relevant during this period (e.g.,B. B. Brown & Klute, 2003; Steinberg & Morris,2001) and are likely to be internalized as part ofone’s identity. As youth identify with multiplesocial groups, their social self-definition can becomeincreasingly complex. Relatively little is known,however, about how multiple social identities inter-sect (e.g., Kiang, Yip, & Fuligni, 2008; Rowley,Sellers, Chavous, & Smith, 1998). The goal of thisstudy is to examine the ways in which the multiplegroups with which youth identify (e.g., ethnic,

interest-based, or activity groups) overlap, and howsuch structural overlap is related to cross-ethnicfriendships and intergroup attitudes in an ethnicallydiverse sample of middle school students.

Studying the complexity of social identities inearly adolescence is expected to be relevant for sev-eral reasons. By early adolescence, youth have mas-tered the prerequisite cognitive skills forsimultaneous, multiple classification (Aboud, 1988;Bigler & Liben, 1992). Moreover, young adolescentsbegin to differentiate themselves into different roles(e.g., self with friends, parents, or classmates; Harter,1999, 2012). Research examining the intersections ofmultiple aspects of self (e.g., perceived roles, as wellas abilities and behavior) among adolescents sug-gests that youth vary in the degree to which theirself-aspects are perceived to overlap, and that exami-nation of such overlap provides insights about per-sonal self-complexity (Evans, 1994; Linville, 1985).Although less research has focused on the complex-ity of social identities defined by group memberships(e.g., self as a school band member, as part of thepopular group, or as an African American), we pre-sume that young adolescents also vary in how theyview the overlap of their multiple social groups.

Social Identity Complexity

In this study, we examine social identity complexitythat refers to the perceived overlap of the groups

This research was supported by the National Science Founda-tion and the National Institutes of Health. The authors wouldlike to thank members of the UCLA Middle School DiversityProject for their assistance with data collection, as well as Guada-lupe Espinoza, Negin Ghavami, Sandra Graham, Hannah Schac-ter, and Ylva Svensson for their comments on the manuscript.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed toCasey A. Knifsend, Department of Psychology, University ofCalifornia, Los Angeles, 1285 Franz Hall, Los Angeles, CA90095-1563. Electronic mail may be sent to [email protected]

© 2013 The AuthorsChild Development © 2013 Society for Research in Child Development, Inc.All rights reserved. 0009-3920/2013/xxxx-xxxxDOI: 10.1111/cdev.12157

Child Development, xxxx 2013, Volume 00, Number 0, Pages 1–13

with which a person aligns him- or herself (Roccas &Brewer, 2002). This construct is assessed by consider-ing the overlap in the compositions of one’s multiplein-groups (Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Miller, Brewer, &Arbuckle, 2009; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). For exam-ple, the question for an African American teen whoidentifies herself as a member of the school band andas part of the popular crowd is to what degree themembers of these groups overlap. When she per-ceives the members of her salient social in-groups tooverlap (e.g., most band members are also popularand African American), her social identity complex-ity is low because the same peers belong to each in-group. That is, her social self consists of groups thatconverge into one relatively cohesive, or structurallyless complex, social identity. In contrast, when sheperceives only a few band members to be popular orAfrican American, her social identity complexity ishigh because in-group members in one category canbelong to out-groups across the other categories. Inother words, when this popular, African Americanband member strongly identifies with her schoolband, she is presumed to regard her non–AfricanAmerican and not-so-popular band members as partof “her group,” much like she regards her AfricanAmerican peers. Thus, these distinct in-groups cap-ture the structural complexity of her social identities.

Social identity complexity complements otherdevelopmental social identity approaches that focuson single identities. For example, ethnic identity(i.e., group esteem) becomes increasingly importantduring middle school, especially among ethnicminority youth (French et al., 2006). Because one’sethnic identity emerges along with other socialidentities, however, the social identity complexityconstruct provides a way to understand how thesedifferent groups intersect. That is, youth with astrong ethnic identity can vary in how they seethemselves as members of other social groups. Ifthey identify with other social groups that consistof only a few same-ethnic peers, these other socialidentities should theoretically have no implicationson their ethnic identity as to being weaker or lessimportant. Rather, identifying with both one’sethnic group and other groups with small same-ethnic representations should further facilitate posi-tive intergroup attitudes, inasmuch as youth cansimultaneously consider multiple groups represent-ing various aspects of their social identity.

Social Identity Complexity and Intergroup Attitudes

Considering that in-group preference emerges asearly as childhood (e.g., Bigler, Jones, & Lobliner,

1997; Dunham, Baron, & Carey, 2011), the ways inwhich social identity complexity can promote posi-tive intergroup attitudes in relatively ethnicallydiverse middle schools are of particular concern.When social in-groups are largely overlapping (i.e.,low social identity complexity), boundaries between“us” versus “them” are reinforced. That is, if mostother band members are also African American andpopular, one’s sense of their social identity isstrong, but possibly exclusive. In contrast, when in-groups are largely nonoverlapping, group bound-aries are diffused. When out-group members canbelong to an in-group (e.g., some or many bandmembers are non–African American), prejudicetoward ethnic out-groups should be reduced(Roccas & Brewer, 2002).

Consistent with these predictions, Brewer andPierce (2005) found that greater social identity com-plexity was related to more similar feelings ofwarmth toward in-group and out-group members(i.e., lower in-group preference). We are aware ofonly one small-scale study in a middle school sam-ple that demonstrated that predominantly Euro-pean American middle school students with morecomplex social identities reported less apprehensionabout, and greater benefits of, interacting withpeers from other ethnic groups (Knifsend & Juvo-nen, 2013). Whether social identity complexity isassociated with positive intergroup attitudes amongethnic minority youth remains unknown. Moreover,relatively little is known about what gives rise tocomplex social identities. That is, what environmen-tal factors, or what we refer to as contextual ante-cedents, might help us to understand thedevelopment of complex social identities?

Contextual Antecedents of Social Identity Complexity

According to Roccas and Brewer (2002), objectivesocial experiences are likely to influence social iden-tity complexity. Testing this hypothesis cross-sectionally in a predominantly European Americanadult sample, Miller et al. (2009) found that individ-uals living in ethnically diverse areas demonstratedhigher levels of social identity complexity, relativeto those who lived in more homogenous areas.Thus, environments with multiple, partiallyoverlapping groups (e.g., neighbors can be ethnicin-group or out-group members) likely reinforcethe idea that groups can overlap in various ways(Roccas & Brewer, 2002). We presume that ethnicallydiverse schools function similar to neighborhoods,especially if there are substantial opportunities fordifferent ethnic groups to affiliate with one another.

2 Knifsend and Juvonen

While diverse environments may strengthensocial identity complexity, Roccas and Brewer(2002) note that the quality of out-group contactmay be especially influential to social identity com-plexity. In a study of Irish college students, high-quality contact with religious out-group members(i.e., conversing with people of a different faith inneighborhood or in social settings, and havingfriends of a different religious background) wasassociated with greater social identity complexity(Schmid, Hewstone, Tausch, Cairns, & Hughes,2009). In ethnically diverse middle schools wherethere are opportunities for cross-ethnic affiliation,this may mean that adolescents who have closecross-ethnic friendships are particularly likely torealize that the boundaries between in-group andout-group members are fluid.

Social Identity Complexity as a Mediator

Given the respective associations between cross-ethnic interaction, social identity complexity, andintergroup attitudes, it is pertinent to examinewhether social identity complexity mediates theassociation between cross-ethnic interaction andethnic intergroup attitudes. According to intergroupcontact theory, cross-group contact under certainconditions (e.g., equal status between groups) canminimize prejudice (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew, 1998;Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). Studies on children andadolescents suggest that greater cross-group contactis associated with higher perceived wrongfulness ofrace-based exclusion (Crystal, Killen, & Ruck, 2008;Ruck, Park, Killen, & Crystal, 2011), lower in-groupbias (Aboud, Mendelson, & Purdy, 2003), and morepositive out-group attitudes (Tropp & Prenovost,2008). In particular, cross-ethnic friendships may beespecially influential to intergroup attitudes becausethey fulfill many of the conditions of contact theory(Davies, Tropp, Aron, Pettigrew, & Wright, 2011;Pettigrew, 1998). For instance, in a study of Germanand Turkish children, cross-ethnic friendships wereassociated with more positive out-group attitudes(i.e., out-groups rated as friendly, smart, and polite;Feddes, Noack, & Rutland, 2009). Thus, takingadvantage of opportunities for cross-ethnic friend-ships in diverse settings may be especially impor-tant to intergroup attitudes.

Although affective and cognitive mechanismsunderlying the association between out-group affili-ation and intergroup attitudes (e.g., anxiety aboutintergroup interactions; Brown & Hewstone, 2005)have been investigated, to our knowledge only onestudy has examined social identity complexity as a

mediator of this link. In their study of Irish adults,Schmid et al. (2009) found that social identity com-plexity mediated the association between positiveinteraction with out-group members (e.g., convers-ing with religious out-group members and havingout-group friendships) and perceived affective dis-tance (i.e., warmth) between religious in-group andout-group members. Whether social identity com-plexity might help account for the associationbetween cross-ethnic friendships and ethnic out-group attitudes among young adolescents attendingdiverse schools is one of the main questions guid-ing this study.

Current Study

Extending past research on social identity devel-opment by examining the intersections of multiplesocial groups, this study investigates how cross-ethnic affiliation is associated with social identitycomplexity, and how identity complexity in turn islinked with ethnic intergroup attitudes, in seventhgrade. Self-definition through groups should beespecially relevant in the middle school context.Middle schools are less structured and on average 7times larger than neighborhood elementary schools,making the school social context increasingly chal-lenging for young adolescents to navigate (Eccles &Midgley, 1989; Juvonen, Le, Kaganoff, Augustine, &Constant, 2004). We presume that identificationthrough various school-based groups can help ado-lescents navigate within this expanding social scenebecause of their heightened need to fit in and tobelong with peer groups (Brown, 1990; Crosnoe,2011).

Two main goals guide this study. Our first goal isto preface our main analyses by describing thegroups with which adolescents identify during mid-dle school, and by analyzing ethnic differences incross-ethnic friendships, social identity complexity,and ethnic intergroup attitudes (i.e., measured associal distance between ethnic in-groups and out-groups; Brewer & Pierce, 2005). Second, our maingoal is to investigate the associations between cross-ethnic friendships, social identity complexity, andethnic intergroup attitudes. We hypothesized thatsocial identity complexity (i.e., overlap in composi-tions of four social groups, including ethnic group)would mediate the link between cross-ethnic friend-ships and ethnic intergroup attitudes when adoles-cents have many cross-ethnic peers at school. Giventhat our study is the first to investigate social identitycomplexity in ethnically diverse schools, which varyin opportunities for cross-ethnic interaction in ways

Social Identity Complexity in Urban Middle Schools 3

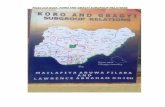

that can affect cross-ethnic friendships (Hallinan &Teixeira, 1987), we expected that the link betweencross-ethnic friendships and social identity complex-ity may be stronger when there is ample choice ofpeers with whom to form such friendships. Hence,we tested a moderated mediation model in whichthe association between cross-ethnic friendships andsocial identity complexity (i.e., a path in Figure 1) ispresumed to vary depending on the availability ofcross-ethnic peers.

Method

Data for this study were collected as part of a larg-er, longitudinal study of middle schools located inCalifornia. Analyses for this study relied on datacollected in the spring of seventh grade (during the2010–2011 school year) from four schools. Each ofthe schools was selected because they were ethni-cally diverse, providing opportunities for cross-ethnic interaction. Relying on Simpson’s Index ofDiversity (i.e., ranging from 0 to 1; Simpson, 1949),the four schools ranged from .61 to .70, suggestingthat schools were fairly comparable in terms oftheir high ethnic diversity. The percentage of stu-dents receiving free or reduced lunch ranged from26% to 57% across the schools (Ed-Data, 2012).

Participants

Participants ranged in age at seventh grade datacollection from 11 to 14 years (M = 12.56,SD = 0.54). Based on self-reports, the final sample(N = 622) was 41% Latino or Mexican American(n = 257), 34% European American (n = 212), 14%African American (n = 90), and 10% East or South-east Asian American (n = 63), with 53% female.Adolescents who identified as Other (e.g., MiddleEastern) or as belonging to two or more ethnicgroups were excluded from the current analyses

because our ethnic intergroup attitudes measureonly considered the four major ethnic or racialgroups (i.e., asked about attitudes toward Asian,Black, Latino, and White youth). Representations ofeach ethnic group in our sample varied acrossthe four schools (Latino or Mexican American:25%–51%; European American: 19%–48%; AfricanAmerican: 14%–22%; and Asian American: 5%–11%).

Procedure

In the fall of sixth grade, adolescents broughthome parent consent forms and informational let-ters explaining the study. To increase the numberof returned consent forms (either allowing or notallowing study participation), adolescents and par-ents returning the consent form were entered into araffle of $50 gift cards. Eighty percent of distributedconsent forms were returned, and of those 17% didnot grant permission to participate in the study.Only those who returned parent consent forms per-mitting participation and assented to participatewere included in the study. Seventh-grade datawere collected across two class periods. Researchersread most items aloud. Participants received $10 forcompleting the questionnaire.

Measures

Availability of cross-ethnic peers. Availability ofcross-ethnic peers in one’s grade at school was cal-culated using California Department of Educationstatistics on the number of seventh-grade studentsfrom each ethnic group (see Table 1; CaliforniaDepartment of Education, 2011). For each ethnicgroup within each of the four schools, wecomputed a score reflecting the proportion of

Cross-ethnic Friendships

Ethnic Outgroup Distance

Social Identity Complexity

Availability of Cross-ethnic

Peers

a b

c/c’

Figure 1. Moderated mediation model.

Table 1Distributions of Ethnic Groups in the Seventh Grade at Each School

School

AfricanAmerican

(%)

AsianAmerican

(%)

EuropeanAmerican

(%)

Latino orMexicanAmerican

(%)Other(%)

School 1 40 (14) 30 (10) 118 (40) 91 (31) 15 (5)School 2 62 (21) 16 (5) 58 (19) 155 (52) 10 (3)School 3 117 (22) 61 (11) 122 (23) 211 (41) 17 (3)School 4 117 (16) 70 (10) 343 (48) 177 (25) 15 (2)

Note. While students categorized as Other were not included inour current sample, they were accounted for in calculations ofavailability of cross-ethnic peers at school. The Other group con-sisted of students identified as American Indian or AlaskanNative, Pacific Islander, Filipino, or as belonging to two or moreethnic groups.

4 Knifsend and Juvonen

seventh-grade peers who belong to ethnic out-groups (i.e., number of seventh-grade students ofall other ethnic backgrounds divided by the totalnumber of seventh-grade students, minus oneself).Overall, adolescents in our sample had a meanavailability score of .68 (SD = .14, range = .49–.95),suggesting an average of 68% of one’s grade matesbelonging to a different ethnic group than theirown. This value is consistent with the relativelyhigh diversity of the schools.

Proportion of cross-ethnic friendships. Participantsprovided an unlimited number of nominations oftheir “good friends” who were in the seventh gradeand attended the same school. Cross-gender friend-ship nominations were permitted. We relied onfriendship choices, rather than reciprocal nomina-tions, because we presumed that one’s perceptionsof their friendships are most relevant to their self-definition. For each friend listed, participantsresponded to one item asking whether the friendbelongs to the same or a different ethnic group.Consistent with prior studies on social identitycomplexity (Schmid et al., 2009), we employed asubjective measure of cross-ethnic friendshipsbecause perceptions of cross-ethnic friendships wereexpected to be most relevant to perceived socialidentity complexity. To control for friendship net-work size, the proportion of cross-ethnic friendshipswas calculated by dividing the number of cross-ethnic friends by the total number of friends nomi-nated. Reflecting the diversity of the settings, half(M = .50, SD = .33) of listed friends were rated asbelonging to a different ethnic group, on average.

Social identity complexity. The adolescent socialidentity complexity measure, measuring the degreeto which in-groups are perceived to overlap, wasadapted from an adult version used by Brewer andPierce (2005) and an adolescent version used byKnifsend and Juvonen (2013). Data collection wasadministered on 2 days to implement the socialidentity complexity measure. On the 1st day of datacollection in seventh grade, participants were askedto list three social groups that described them as aperson. Before identifying themselves with theirgroups, participants were provided with types ofgroups that could describe them (e.g., extracurricu-lar activities, sports, religious groups, or socialgroups) and with four to five examples of each.Participants were then asked to imagine that theywere filling out a new Facebook page describingthemselves to people who do not know them, andto list three groups that best describe them as a per-son. We provided examples of groups, in additionto general categories of possible groups (e.g., reli-

gious groups or social groups; Brewer & Pierce,2005), to ensure that young adolescents understoodthe types of groups to which they may belong.

After identification of social groups on the firstday of data collection, research assistants individual-ized each participant’s questionnaire with their fourgroup memberships (i.e., the three social identitygroups listed on the 1st day, in addition to self-reported ethnic group). Ethnicity was used as thefourth group membership because we expected theoverlap between one’s ethnic group with their othersocial groups to be particularly relevant to ethnicintergroup attitudes. To ensure that ethnicity wasindeed as salient as the other three social groupslisted, we also obtained importance ratings for eachof the four groups (see below). During this 2nd dayof data collection, participants then rated the groupmembership overlap of each bidirectional pairing oftheir four groups. To orient them to the task, anexample was provided where they estimated “Howmany soccer players are seventh graders?” and“How many seventh graders are in soccer?” on a5-point scale (1 = almost all, 5 = hardly any). Relyingon the same 5-point scale, participants then rated the12 pairings of their own social groups (e.g., “Howmany people in [Group A] are in [Group B]? Howmany people in [Group B] are in [Group A]?”). Socialidentity complexity scores were calculated as themean of the 12 ratings reflecting the overlap of thefour groups listed. A high score indicates little per-ceived membership overlap among groups (i.e., highsocial identity complexity). On average, adolescentsin our sample perceived between about half and afew members of one in-group to belong to anotherin-group (M = 3.27, SD = 0.61), suggesting a moder-ate degree of social identity complexity.

Reliability was calculated using a Spearman–Brown split-half coefficient. The 12 ratings weredivided into two subsets, such that bidirectionalpairings were in different subsets (i.e., “How manypeople in [Group A] are in [Group B]?” in onesubset, “How many people in [Group B] are in[Group A]?” in the other subset). The Spearman–Brown reliability coefficient was .88, suggesting thatthe social identity complexity measure has goodinternal consistency.

Importance of social identities. Because social iden-tity complexity is based on social in-groups that arepersonally meaningful (Roccas & Brewer, 2002),participants were asked to rate the importance oftheir four groups on the 2nd day of data collectionin seventh grade. Specifically, they rated the impor-tance of their three social groups and their ethnicgroup (e.g., “How important is it to you that you

Social Identity Complexity in Urban Middle Schools 5

are a [Group A] member?”). Responses were on a5-point scale (1 = definitely not important, 5 = defi-nitely important).

Intergroup attitudes. Items assessing the degreeto which seventh-grade students wanted to associ-ate with ethnic in-group and out-group memberswere used to calculate social distance (Bogardus,1933; Brewer, 1968; Jones, 2004; Marsden, 1988).Participants were first provided with an examplewhere they were asked to rate if they would like toeat lunch, get together at their house, dancetogether at a party, or sit together on a schoolbus with kids who were in the eighth grade (i.e.,out-group based on grade), on a 5-point scale(1 = no way!, 5 = for sure yes!). After completing theexample, participants responded to the same fouritems for Asian, Black, Latino, and White youth(e.g., “Now think about doing these things withkids who are [Ethnic Group]. Would you want toeat lunch with…”) for a total of 16 items. Blocksof the four items within each ethnic group werepresented in four different orders that were ran-domly assigned to the participants. We chose tofocus on these developmentally relevant behavioralitems assessing social distance (included as part ofa larger battery of intergroup attitudes measures) toexpand on prior research on social identity com-plexity that has relied mainly on affective measuresof in-group bias (e.g., Schmid et al., 2009).

Consistent with adult studies of social identitycomplexity (e.g., Brewer & Pierce, 2005), we reliedon an aggregated measure of social distance fromall three ethnic out-groups, rather than examiningdistance from specific ethnic groups. Social distancewas calculated by subtracting the average of 12items for three ethnic outgroups from the averageof 4 items for members of one’s own ethnic group.Thus, higher social distance scores indicate greaterin-group preference, whereas lower social distancescores indicate that ethnic out-groups are ratedmore similarly to one’s in-group. On average,adolescents in our sample preferred their ethnicin-group over out-groups (M = 0.41, SD = 0.66).Cronbach’s alphas calculated among 4 in-groupitems (a = .86) and 12 out-group items (a = .94)indicated very high internal reliability.

Results

The Results section consists of three parts. To pre-face our main analyses, we first describe the socialgroups listed by young adolescents in our sample.The second part presents analyses of ethnic group

differences in cross-ethnic friendships, social iden-tity complexity, and ethnic intergroup attitudes (i.e.,measured as perceived social distance from ethnicout-groups). In the third part, we describe results ofregression analyses testing the links between cross-ethnic friendships, social identity complexity, andethnic intergroup attitudes. Specifically, we testwhether social identity complexity mediates theassociation between cross-ethnic friendships andethnic intergroup attitudes when youth have a highavailability of cross-ethnic peers at school.

Social Identities

To describe the types of groups with which youthidentify, trained research assistants categorizedsocial groups into nine categories with high inter-rater reliability, j = .97. As reflected in Table 2, out-of-school sports (e.g., club soccer or swimming) werethe most common groups listed, followed by groupsbased on religious affiliation (e.g., Christian orJewish), peer crowds (e.g., popular people or nerds),out-of-school performing arts (e.g., ballet or theater),gaming (e.g., video gamer), school-based clubs (e.g.,Cooking Club or National Junior Honor Society),special interests (e.g., robotics or environmentalgroups), out-of-school visual arts (e.g., animation orphotography), and academic orientation (e.g., goodstudents or overachievers), respectively. Descriptivestatistics of the importance ratings of each social in-group suggested that on average, the groups listedwere regarded as important (M = 3.87, SD = 1.06,range = 3.22–4.58 on a 5-point scale). The averageimportance of ethnicity (i.e., the only group identity

Table 2Number and Percentage of Adolescents Reporting Common SocialIdentities

Social identity

Importance

n (% ofadolescents) M SD

Out-of-school sports 353 (57) 3.97 0.96Religious affiliation 325 (52) 4.17 0.98Peer crowds 286 (46) 3.41 1.10Out-of-school performing arts 211 (34) 4.01 1.00Gaming 162 (26) 3.22 1.13School-based clubs 156 (25) 4.24 0.88Special interests 91 (15) 3.92 1.07Out-of-school visual arts 58 (9) 4.15 0.87Academic orientation 39 (6) 4.58 0.83Other 9 (1) 4.00 1.12

Note. Importance of social groups was measured on a 5-pointscale, where 1 = definitely not important and 5 = definitely important.

6 Knifsend and Juvonen

not self-nominated) was similar to the overall impor-tance ratings (M = 3.91, SD = 1.17), suggesting thatit was as important as the three other social groups.Although we could not compare group importanceratings statistically because specific groups variedacross individuals, groups based on academic orien-tation and school clubs received particularly highimportance ratings (Ms > 4.20), in spite of their rela-tive infrequency.

Ethnic Group Differences

To explore group differences in cross-ethnicfriendships, social identity complexity, and per-ceived distance from ethnic out-groups, a series ofanalysis of variance (ANOVA) models wereemployed. Possibly reflecting relative group size,ethnic groups differed in proportions of cross-ethnicfriendships, F(3, 618) = 7.00, p < .001, g2

p = .03. Posthoc independent samples t tests with a Bonferronicorrection suggested that Latino or Mexican Ameri-can adolescents (M = .45, SD = .34) had a smallerproportion of cross-ethnic friends than Asian Ameri-can adolescents (M = .63, SD = .33), t(318) = 3.95,SE = 0.05, p < .001, and African American adoles-cents (M = .56, SD = .33), t(345) = 2.76, SE = 0.04,p < .01. There were also significant differences insocial identity complexity across ethnic groups, F(3,618) = 4.72, p < .01, g2

p = .02. Post hoc t tests with aBonferroni correction indicated that Latino orMexican American adolescents (M = 3.20, SD = 0.64)perceived lower social identity complexity thanAsian American adolescents (M = 3.45, SD = 0.60),t(318) = 2.73, SE = 0.09, p < .01. Lastly, ethnicgroups differed in their social distance from ethnicoutgroups, F(3, 618) = 6.40, p < .001, g2

p = .03. Posthoc t tests revealed that Latino or Mexican Americanyouth (M = 0.53, SD = 0.72) reported greaterout-group distance (i.e., greater in-group preference)relative to African American adolescents (M = 0.25,SD = 0.58), t(345) = 3.31, SE = 0.08, p < .01, andEuropean American adolescents (M = 0.31,SD = 0.60), t(467) = 3.48, SE = 0.06, p < .01.

In sum, Latino or Mexican American youth hada smaller proportion of cross-ethnic friends, lowersocial identity complexity, and greater ethnic out-group distance compared to other ethnic groups inour sample. In contrast, Asian American adoles-cents had a high proportion of cross-ethnic friend-ships and relatively high social identity complexity.In the next section, the associations between cross-ethnic friendships, social identity complexity, andethnic out-group distance are tested in a moderatedmediation model.

Moderated Mediation Model

Our main goal was to test the links between cross-ethnic friendships, social identity complexity, andethnic intergroup attitudes by relying on a moder-ated mediation model investigating whether theindirect effect was especially strong when adoles-cents had a high availability of cross-ethnic peers intheir grade at school. Correlations of the main modelvariables are presented in Table 3. Regression mod-els were run using the PROC REG procedure and thePROCESS macro in SAS version 12.1 (Hayes, 2013).Analyses controlled for ethnicity and school attendedusing dummy coding to account for group differ-ences in these variables. In addition to the ethnic dif-ferences discussed in the prior section, youth atSchool 1 perceived less out-group distance than ado-lescents at Schools 2 and 4, F(3, 618) = 6.96, p < .001,g2

p = .03. Given that most research on social identitycomplexity focuses on European American samples,the school with the highest percentage of EuropeanAmerican students, School 4, was chosen as the com-parison school. Similarly, European American ado-lescents were chosen as the comparison group forethnicity. Considering that availability of cross-ethnic peers and availability of cross-ethnic friend-ships were entered separately and as an interactionterm in our regression models, each variable was cen-tered around its mean to reduce multicollinearity.Centered variables were used to compute the productof the two variables to test the moderator hypothesis.

Because we expected that availability of cross-ethnic peers would moderate the a path in ourmediational model (see Figure 1), our first objectivewas to examine availability of cross-ethnic peers asa moderator of the association between cross-ethnicfriendships and social identity complexity, using athree-step method (Baron & Kenny, 1986). First,proportion of cross-ethnic friendships was enteredseparately as a predictor of social identity complex-ity. Cross-ethnic friendships were a significant

Table 3Pearson Correlations of Cross-Ethnic Availability, Friendships, SocialIdentity Complexity, and Ethnic Out-Group Distance

1 2 3 4

1. Availability of cross-ethnicpeers

— .25*** .07 �.03

2. Cross-ethnic friendships — .13** �.28***3. Social identity complexity — �.15***4. Ethnic out-group distance —

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

Social Identity Complexity in Urban Middle Schools 7

predictor of social identity complexity, b = 0.21,SE = 0.07, p < .01. Second, availability of cross-ethnic peers was entered into the model to test itseffect over and above cross-ethnic friendships.Availability of cross-ethnic peers was not associatedwith social identity complexity, b = 0.25, SE = 0.27,p = .35. Third, the product of the two predictorvariables was entered. Results of this regressionmodel revealed a significant interaction over andabove the effects of the two predictors, b = 1.35,SE = 0.56, p < .05. As reflected in Figure 2, a greaterproportion of cross-ethnic friendships significantlypredicted higher social identity complexity, butonly when availability of cross-ethnic, same-gradepeers at school was at its mean (b = 0.19, SE = 0.08,p < .05) or greater than 1 SD above its mean(b = 0.37, SE = 0.10, p < .001). Consistent with ourhypothesis, this finding may be explained bygreater proportions of cross-ethnic friendships whenthere is a moderate to high availability of cross-ethnic peers in one’s grade at school (95% CI offriendships when availability is 1 SD below mean is[.35, .44], 95% CI of friendships when availability atmean is [.49, .55], 95% CI of friendships when avail-ability is 1 SD above the mean is [.54, .68]).

To test the moderated mediation model, our sub-sequent objectives were to examine the direct effectof cross-ethnic friendships on ethnic out-group dis-tance, as well as how both cross-ethnic friendshipsand social identity complexity relate to out-groupdistance (Baron & Kenny, 1986). First, analyses ofthe direct effect of cross-ethnic friendships on ethnicout-group distance suggested that a greater propor-tion of cross-ethnic friendships was associated withless out-group distance (i.e., c path in Figure 1;b = �0.51, SE = 0.08, p < .001). Second, cross-ethnicfriendships and social identity complexity weretested as predictors of out-group distance in the

same model. As shown in Table 4, greater propor-tions of cross-ethnic friendships (i.e., c′ path inFigure 1; b = �0.48, SE = 0.08, p < .001) and morecomplex social identities (i.e., b path in Figure 1;b = �0.12, SE = 0.04, p < .01) were each associatedwith less distance from ethnic outgroups.

Given that there was a direct link between cross-ethnic friendships and ethnic out-group distance,and that social identity complexity was associatedwith out-group distance, the next set of analysesfollowed procedures outlined by Preacher, Rucker,and Hayes (2007) to test conditional indirect effects.Conditional indirect effects refer to mediationaleffects at different levels of the moderator (i.e.,availability of cross-ethnic peers in one’s grade).Bootstrapping was used to investigate the role ofsocial identity complexity as a mediator at variousvalues of cross-ethnic availability (Bollen & Stine,1990; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). The bootstrappingmethod produced 95% bias-corrected confidenceintervals of estimates of the indirect effect from1,000 resamples of the data. Confidence intervalsthat do not contain zero indicate that the condi-tional indirect effect is significant at a = .05.

As reported in Table 5, conditional indirecteffects were first examined at three levels of cross-

Figure 2. Availability of cross-ethnic peers in the seventh gradeas a moderator of the association between cross-ethnic friend-ships and social identity complexity.

Table 4Regression Models Predicting Mediator and Dependent Variable inModerated Mediation Model

Predictors b SE

Mediator variable model (DV = social identity complexity)Constant 3.34*** 0.05African American �0.24** 0.09Asian American �0.03 0.11Latino or Mexican American �0.12* 0.06School 1 0.00 0.08School 2 �0.01 0.08School 3 0.01 0.06Cross-ethnic friendships 0.19* 0.08Availability 0.29 0.27Cross-Ethnic Friendships 9 Availability 1.35* 0.56

Dependent variable model (DV = ethnic out-group distance)Constant 0.84*** 0.15African American �0.04 0.08Asian American 0.23** 0.09Latino or Mexican American 0.18** 0.06School 1 �0.29*** 0.08School 2 �0.06 0.08School 3 �0.18** 0.06Cross-ethnic friendships �0.48*** 0.08Social identity complexity �0.12** 0.04

Note. DV = dependent variable.*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

8 Knifsend and Juvonen

ethnic availability that were 1 SD below the mean(.54), at the mean (.68), and 1 SD above the mean(.81). Social identity complexity was a significantmediator only when cross-ethnic availability was ator 1 SD above its mean. To further investigate theexact level of cross-ethnic availability at whichsocial identity complexity is a significant mediator,conditional indirect effects were examined at eachpossible level of cross-ethnic availability in oursample. As shown in Table 5, these results suggestan indirect effect of social identity complexity whenadolescents have 69% or greater cross-ethnic peersin the seventh grade at their school. That is, consis-tent with our hypothesis, social identity complexitymediated the association between cross-ethnicfriendships and distance from ethnic out-groupswhen adolescents had a high proportion of cross-ethnic peers in the seventh grade at their school.

Discussion

Complementing research on social identity develop-ment that focuses primarily on single social

identities (e.g., ethnic), we examine multiple socialidentities and the ways in which they intersect inan early adolescent sample. By capturing the per-ceived overlap among multiple social groups withwhich youth identify, the social identity complexityconstruct can help us understand in-group andout-group distinctions (or the lack thereof), and istherefore particularly applicable to the study of in-tergroup attitudes. To study these constructs in thecontext of existing relationships within schools, it isalso critical to consider cross-ethnic friendships andthe availability of cross-ethnic peers within theschool when relating social identity complexity tointergroup attitudes.

One of our main objectives was to investigate thelink between social identity complexity and ethnicintergroup attitudes. Consistent with prior research(e.g., Brewer & Pierce, 2005), young adolescentswith high social identity complexity reported lessdistance from ethnic outgroups. Social identity com-plexity likely minimizes the distinctions between in-groups and out-groups, which can promote positiveintergroup attitudes (Brewer & Pierce, 2005). Alter-natively, social identity complexity may functionsimilarly to the common in-group identity modeland dual-identity approach (Gaertner & Dovidio,2000; Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman, &Rust, 1993), which posits that connecting in-groupsand out-groups through a common, superordinatein-group extends positive in-group attitudes to allmembers of the larger group. Although social iden-tity complexity differs in that it considers specifi-cally perceptions of multiple, lateral in-groups,individuals with high social identity complexitydefine their in-groups across one category as includ-ing both in-groups and out-groups across other cate-gories (e.g., members of the school band can beAfrican American or European American).

Given that high social identity complexity wasassociated with more positive attitudes toward eth-nic outgroups, we were particularly interested ininvestigating the contextual antecedents associatedwith complex social identities. Consistent with ourhypothesis, we documented that close cross-ethnicfriendships are associated with social identity com-plexity, and that this effect is especially strongwhen youth have ample opportunities to form suchrelationships at school (i.e., availability of cross-ethnic classmates is at or greater than its mean).These findings are consistent with research basedon adult samples, suggesting that individuals whoshare interpersonal relationships with out-groupmembers may be especially aware of malleableboundaries between in-groups and out-groups

Table 5Conditional Indirect Effect at Different Levels of Cross-Ethnic Avail-ability

Availability (a1 + a3W)b1 SE Lower 95% CI Upper 95% CI

Conditional effect at availability = mean � 1 SD (DV = ethnicout-group distance).54 �0.00 0.01 �0.03 0.03.68 �0.02 0.01 �0.06 �0.01.81 �0.05 0.02 �0.10 �0.01

Conditional effect at range of values of availability (DV = ethnicout-group distance).49 0.01 0.02 �0.02 0.05.53 0.00 0.02 �0.02 0.04.59 �0.01 0.01 �0.04 0.01.69 �0.03 0.01 �0.06 �0.01.76 �0.04 0.02 �0.08 �0.01.81 �0.04 0.02 �0.10 �0.01.84 �0.05 0.02 �0.11 �0.01.90 �0.06 0.03 �0.14 �0.02

Note. Availability scores are centered about mean availabilityacross the sample. The conditional indirect effect is (a1 + a3W)b1,where a1 is the association of the predictor, cross-ethnic friend-ships with the mediator, social identity complexity; a3 is the asso-ciation of the interaction of cross-ethnic friendships andavailability of cross-ethnic peers with social identity complexity;W is availability of cross-ethnic peers; and b1 is the association ofsocial identity complexity with ethnic out-group distance. Forbrevity, only a subset of the range of values of availability ispresented. DV = dependent variable.

Social Identity Complexity in Urban Middle Schools 9

(Schmid et al., 2009). Moreover, the role of cross-ethnic availability as a moderator of the linkbetween cross-ethnic friendships and social identitycomplexity underscores the importance of having arange of opportunities to form cross-ethnic friend-ships. Although prior research did not account forcross-group availability, possibly because opportu-nities for out-group affiliation were comparableacross groups (e.g., Catholics and Protestants in Ire-land; Schmid et al., 2009), cross-ethnic availabilitywas considered in this study because opportunitiesfor out-group interaction varied across the fourschools for youth from different ethnic groups.Considering that most adolescents with low avail-ability of cross-ethnic peers reported that less thanhalf of their friends belonged to other ethnicgroups, it is possible that only one or a couple ofcross-ethnic friends are not enough to influencesocial identity complexity. That is, consistent withprior research suggesting that adults with the great-est social identity complexity have an extremelyhigh degree of cross-group interaction (e.g., all ofone’s friends belong to an out-group; Schmid et al.,2009), social identity complexity is promoted moststrongly when adolescents with many options forcross-ethnic affiliation avail themselves of theseopportunities.

Due to the moderating effect of cross-ethnicavailability, social identity complexity mediated thelink between cross-ethnic friendships and ethnicout-group distance only when cross-ethnic avail-ability was relatively high (i.e., ≥ 68%). That is, themediational model was supported when ethnic in-group representation was at or below 32% withinone’s school. Similar to results of our moderationanalyses, opportunities for cross-ethnic affiliationmust be present and taken advantage of for socialidentity complexity to account for the link betweencross-ethnic friendships and ethnic intergroup atti-tudes. Extending research in adult samples investi-gating social identity complexity as a mediator ofthis association (Schmid et al., 2009), this study con-tributes to research on the link between cross-ethnicaffiliation and out-group attitudes among children(e.g., Aboud et al., 2003; Feddes et al., 2009) bysuggesting a mediational role of social identitycomplexity for young adolescents, especially whenthere are many cross-ethnic peers with whom toaffiliate at school.

Limitations and Future Directions

In this study, we relied on a sample derivedfrom four urban middle schools that were

ethnically diverse. However, because relative ethnicrepresentation was similar across the four ethnicgroups in each school (e.g., Latino or MexicanAmerican youth were one of the largest groups,and Asian American students were the smallestgroup), the degree to which cross-ethnic peers wasavailable may have affected ethnic groups in oursample in different ways. For example, Latino orMexican American youth (who had the lowestprobability of cross-ethnic contact) had few cross-ethnic friends and low social identity complexity,and demonstrated the greatest perceived distancefrom ethnic out-group members. In contrast, thesmallest ethnic group (Asian American youth) hadmore cross-ethnic friends and higher social identitycomplexity than Latino or Mexican American ado-lescents. In light of these systematic differencesacross groups, it is critical to avoid inferences aboutethnic group differences without considering therelative size of each ethnic group. Conductingfuture studies using samples in which the relativesize of ethnic groups varies across schools is imper-ative. Moreover, additional research in which theoverall ethnic diversity of schools varies is impor-tant. Adolescents who belong to a relatively smallethnic group in schools with one majority ethnicgroup may not avail themselves to opportunitiesfor cross-ethnic contact to the same extent as smallethnic groups in our highly diverse sample (Moody,2001).

Although our data were collected as part of alarger longitudinal study beginning in sixth grade,we were not able to conduct longitudinal analysesbecause social identity complexity was measuredbeginning in seventh grade. The social identitycomplexity measure was not implemented duringthe 1st year of middle school because earlier pilotdata suggested that a substantial proportion ofsixth-grade students experienced difficulty namingthree groups with which they identify. Because toour knowledge no study on social identity complex-ity has relied on longitudinal data, additionalresearch is needed to examine stability (or change)in social identity complexity, and the direction ofeffects, over time. For instance, considering thatyouth develop a greater ability to compare and con-trast conflicting, multiple selves during middle ado-lescence (e.g., taking on different roles with parentscompared to peers; Harter, 2012), it is possible thatsocial identities also become more complex and dif-ferentiated during this period. Although priorresearch proposes possible causal links (e.g., Milleret al., 2009; Schmid et al., 2009), little is knownabout whether earlier out-group contact can predict

10 Knifsend and Juvonen

later social identity complexity, or whether socialidentity complexity can affect subsequent inter-group attitudes.

Lastly, additional research linking social identitycomplexity to other important outcomes is needed.While social identity complexity was associatedwith positive ethnic intergroup attitudes, such com-plexity may also be associated with psychologicalwell-being. Self-complexity theory predicts that con-sidering oneself to have multiple, unique self-aspects (i.e., high self-complexity) buffers againstpsychological maladjustment (Linville, 1985).Because social identity complexity is similar to self-complexity in that it considers the degree of differ-entiation between multiple social in-groups thatcontribute to self-definition, we predict that highsocial identity complexity is associated with bettermental health. For individuals with convergentsocial groups (i.e., low social identity complexity),threats to one group should more easily compro-mise personal well-being. In contrast, largely sepa-rate in-groups (i.e., high social identity complexity)buffer against negative reactions when one socialgroup is threatened because failure in one domaindoes not imply failure in every domain (Roccas &Brewer, 2002). While theoretically social identitycomplexity should be related to psychologicaladjustment, to our knowledge no study has testedthis hypothesis. As declines in psychological well-being may be especially common during early ado-lescence (e.g., Chung, Elias, & Schneider, 1998),examining how social identity complexity is associ-ated with psychological adjustment during thisperiod may be a crucial future direction.

Conclusions and Implications

Consistent with prior research (e.g., Bartko &Eccles, 2003; LaFontana & Cillessen, 2010; Smith,Denton, Faris, & Regnerus, 2002), many adolescentsin our sample identified with groups based onout-of-school sports, religious affiliation, and peercrowds. Although fewer adolescents listed academicorientation and school-based clubs, these groupswere rated as highly important to self-definition.Whereas sports, religion, and peer crowds are typi-cal groups through which many youth identifywith their peers, social groups that promote connec-tions with school may be especially important toself-definition for young adolescents. Connecting toothers and finding one’s niche in school is expectedto be particularly important during earlyadolescence, as youth transition to middle schoolsthat are larger and less structured compared to

neighborhood elementary schools (Juvonen et al.,2004). Investigating how to make school-basedclubs and academic activities more accessible to allstudents to promote identification with school isparticularly important.

Finally, this study contributes to discourse aboutthe benefits of ethnically diverse schools. Althoughthe school-aged population in the United States isbecoming increasingly ethnically diverse, manyadolescents attend schools with a high proportionof same-ethnic peers (Orfield & Lee, 2007). Resultsof this study, however, highlight the importance ofattending schools with a high proportion of cross-ethnic peers to the development of cross-ethnicfriendships, complex social identities, and positiveethnic intergroup attitudes. Diverse schools may bein the position to facilitate cross-ethnic friendshipsand complex social identities by providing opportu-nities for students of different ethnic backgroundsto interact in ways that facilitate friendships. Forexample, collaborative extracurricular activities inwhich students from various backgrounds caninteract and form friendships may be especiallyimportant to social identity complexity (K. T.Brown, Brown, Jackson, Sellers, & Manuel, 2003;Knifsend & Juvonen, 2013). Thus, this study sug-gests that ethnically diverse school contexts, whenpossible, may be able to play a vital role in promot-ing complex social identities and positive inter-group attitudes.

References

Aboud, F. E. (1988). Children and prejudice. Oxford, UK:Basil Blackwell.

Aboud, F. E., Mendelson, M. J., & Purdy, K. T. (2003).Cross-race peer relations and friendship quality. Inter-national Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 165–173.doi:10.1080/01650250244000164

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading,MA: Addison-Wesley.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychologicalresearch: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical consider-ations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51,1173–1182. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bartko, W. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2003). Adolescent participa-tion in structured and unstructured activities: A per-son-oriented analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence,32, 233–241. doi:10.1023/A:1023056425648

Bernal, M. E., Knight, G. P., Garza, C. A., Ocampo, K. A.,& Cota, M. K. (1990). The development of ethnic iden-tity in Mexican-American children. Hispanic Journal ofBehavioral Sciences, 12, 3–24. doi:10.1177/07399863900121001

Social Identity Complexity in Urban Middle Schools 11

Bigler, R. S., Jones, L. C., & Lobliner, D. B. (1997). Socialcategorization and the formation of intergroup atti-tudes. Child Development, 68, 530–543. doi:10.2307/1131676

Bigler, R. S., & Liben, L. S. (1992). Cognitive mechanismsin children’s gender stereotyping: Theoretical and edu-cational implications of a cognitive-based intervention.Child Development, 63, 1351–1363. doi:10.2307/1131561

Bogardus, E. S. (1933). A social distance scale. Sociologyand Social Research, 17, 265–271. Retrieved October 15,2012, from http://search.proquest.com/docview/615013114

Bollen, K. A., & Stine, R. (1990). Direct and indirecteffects: Classical and bootstrap estimates of variability.Sociological Methodology, 20, 115–140. Retrieved Septem-ber 13, 2012, from http://sm.sociology.illinois.edu/

Brewer, M. B. (1968). Determinants of social distanceamong East African tribal groups. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 10, 279–289. doi:10.1037/h0026563

Brewer, M. B., & Pierce, K. P. (2005). Social identitycomplexity and outgroup tolerance. Personality andSocial Psychology Bulletin, 31, 428–437. doi:10.1177/0146167204271710

Brown, B. B. (1990). Peer groups and peer cultures. In S.Feldman & G. Elliott (Eds.), At the threshold: The develop-ing adolescent (pp. 171–196). Cambridge, MA: HarvardUniversity Press.

Brown, B. B., & Klute, C. (2003). Friendships, cliques, andcrowds. In G. Adams & M. Berzonsky (Eds.), Blackwellhandbook of adolescence (pp. 330–348). Malden, MA:Blackwell.

Brown, K. T., Brown, T. N., Jackson, J. S., Sellers, R. M.,& Manuel, W. J. (2003). Teammates on and off thefield? Contact with Black teammates and the racial atti-tudes of White student athletes. Journal of Applied SocialPsychology, 33, 1379–1403. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01954.x

Brown, R. J., & Hewstone, M. (2005). An integrative the-ory of intergroup contact. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advancesin experimental social psychology (Vol. 37, pp. 255–331).San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

California Department of Education. (2011). DataQuest[Data file and code book]. Retrieved September 13,2012, from http://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/

Chung, H., Elias, M., & Schneider, K. (1998). Patterns ofindividual adjustment changes during middle schooltransition. Journal of School Psychology, 36, 83–101.doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(97)00051-4

Crosnoe, R. (2011). Fitting in, standing out: Navigating thesocial challenges of high school to get an education. Cam-bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Crystal, D. S., Killen, M., & Ruck, M. (2008). It is who youknow that counts: Intergroup contact and judgmentsabout race-based exclusion. British Journal of Developmen-tal Psychology, 26, 51–70. doi:10.1348/026151007X198910

Davies, K., Tropp, L. R., Aron, A., Pettigrew, T. F., &Wright, S. C. (2011). Cross-group friendships and inter-group attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and

Social Psychology Review, 15, 332–351. doi:10.1177/1088868311411103

Dunham, Y., Baron, A. S., & Carey, S. (2011). Conse-quences of “minimal” group affiliations in children.Child Development, 82, 793–811. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01577.x

Eccles, J. S., & Midgley, C. (1989). Stage-environment fit:Developmentally appropriate classrooms for youngadolescents. In C. Ames & R. Ames (Eds.), Research onmotivation in education (Vol. 3, pp. 139–186). San Diego,CA: Academic Press.

Ed-Data. (2012). Fiscal, demographic, and performance dataon California’s K-12 schools [Data file and code book].Retrieved September 19, 2012, from http://www.ed-data.k12.ca.us/

Evans, D. W. (1994). Self-complexity and its relation todevelopment, symptomatology, and self-perceptionduring adolescence. Child Psychiatry and Human Devel-opment, 24, 173–182. doi:10.1007/BF02353194

Feddes, A. R., Noack, P., & Rutland, A. (2009). Direct andextended friendship effects on minority and majoritychildren’s interethnic attitudes: A longitudinal study.Child Development, 80, 377–390. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01266.x

French, S. E., Seidman, E., Allen, L., & Aber, J. L. (2006).The development of ethnic identity during adolescence.Developmental Psychology, 42, 1–10. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1

Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (2000). Reducing intergroupbias: The common ingroup identity model. Philadelphia:Psychology Press.

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman,B. A., & Rust, M. C. (1993). The common ingroup iden-tity model: Recategorization and the reduction of inter-group bias. In W. Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.),European review of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 247–278).Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Hallinan, M. T., & Teixeira, R. A. (1987). Students’ inter-racial friendships: Individual characteristics, structuraleffects, and racial differences. American Journal of Educa-tion, 95, 563–583. doi:10.1086/444326

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self: A developmen-tal perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

Harter, S. (2012). Emerging self-processes during child-hood and adolescence. In M. Leary & J. Tangney (Eds.),Handbook of self and identity (2nd ed., pp. 680–715). NewYork: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation,and conditional process analysis: A regression-basedapproach. New York: Guilford Press.

Jones, P. E. (2004). False consensus in social context: Dif-ferential projection and perceived social distance. BritishJournal of Social Psychology, 43, 417–429. doi:10.1348/0144666042038015

Juvonen, J., Le, V., Kaganoff, T., Augustine, C., &Constant, L. (2004). Focus on the wonder years: Challengesfacing the American middle school. Santa Monica, CA:Rand.

12 Knifsend and Juvonen

Kiang, L., Yip, T., & Fuligni, A. J. (2008). Multiple socialidentities and adjustment in young adults fromethnically diverse backgrounds. Journal of Research onAdolescence, 18, 643–670. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00575.x

Knifsend, C. A., & Juvonen, J. (2013). The role of socialidentity complexity in intergroup attitudes amongyoung adolescents. Social Development, 22, 623–640.doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00672.x

LaFontana, K. M., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2010). Develop-mental changes in the priority of perceived status inchildhood and adolescence. Social Development, 19,130–147. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00522.x

Linville, P. W. (1985). Self-complexity and affective extrem-ity: Don’t put all of your eggs in one cognitive basket.Social Cognition, 3, 94–120. doi:10.1521/soco.1985.3.1.94

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Growing up apart,coming together. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UniversityPress.

Marsden, P. V. (1988). Homogeneity in confiding rela-tions. Social Networks, 10, 57–76. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(88)90010-X

Miller, K. P., Brewer, M. B., & Arbuckle, N. L. (2009).Social identity complexity: Its correlates and anteced-ents. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12, 79–94.doi:10.1177/1368430208098778

Moody, J. (2001). Race, school integration, and friendshipsegregation in America. The American Journal of Sociol-ogy, 107, 679–716. doi:10.1086/338954

Newman, P. R., & Newman, B. M. (1976). Early adoles-cence and its conflict: Group identity versus alienation.Adolescence, 11, 261–274. Retrieved December 16, 2012,from http://www.researchgate.net/journal/0001-8449_Adolescence

Orfield, G., & Lee, C. (2007). Historic reversals, acceleratingresegregation, and the need for new integration strategies.Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project/Proyecto DerechosCiviles, UCLA.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. AnnualReview of Psychology, 49, 65–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytictest of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personalityand Social Psychology, 90, 751–783. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Phinney, J. S. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents andadults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108,499–514. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007).Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory,

methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate BehavioralResearch, 42, 185–227. doi:10.1080/00273170701341316

Roccas, S., & Brewer, M. B. (2002). Social identity com-plexity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6, 88–106. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_01

Rowley, S. J., Sellers, R. M., Chavous, T. M., & Smith, M.A. (1998). The relationship between racial identity andself-esteem in African American college and highschool students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol-ogy, 74, 715–724. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.715

Ruck, M. D., Park, H., Killen, M., & Crystal, D. S. (2011).Intergroup contact and evaluations of race-based exclu-sion in urban minority children and adolescents. Journalof Youth and Adolescence, 40, 633–643. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9600-z

Sani, F., & Bennett, M. (2004). Developmental aspects ofsocial identity. In M. Bennett & F. Sani (Eds.), The devel-opment of the social self (pp. 77–100). East Sussex, UK:Psychology Press.

Schmid, K., Hewstone, M., Tausch, N., Cairns, E., &Hughes, J. (2009). Antecedents and consequences ofsocial identity complexity: Intergroup contact, distinc-tiveness threat, and outgroup attitudes. Personality andSocial Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1085–1098. doi:10.1177/0146167209337037

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experi-mental and nonexperimental studies: New proceduresand recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

Simpson, E. H. (1949). Measurement of diversity. Nature,163, 688.

Smith, C., Denton, M. L., Faris, R., & Regnerus, M.(2002). Mapping American adolescent religious partici-pation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41,597–612. doi:10.1111/1468-5906.00148

Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent develop-ment. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83–110. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83

Tanti, C., Stukas, A. A., Halloran, M. J., & Foddy, M.(2011). Social identity change: Shifts in social identityduring adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 555–567.doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.012

Tropp, L. R., & Prenovost, M. (2008). The role of inter-group contact in predicting interethnic attitudes: Evi-dence from meta-analytic and field studies. In S. Levy& M. Killen (Eds.), Intergroup attitudes and relations inchildhood through adulthood (pp. 236–248). Oxford, UK:Oxford University Press.

Social Identity Complexity in Urban Middle Schools 13