Selling Artifacts to Save the Past

Transcript of Selling Artifacts to Save the Past

Maupin 1

Chris Maupin

25 March 2015

Proposal: Selling Artifacts to Save the Past

To raise much needed revenue for archaeological

excavations, reduce the strain of storage and maintenance of

artifacts on museums and national heritage agencies and help

undercut the trade in illicit antiquities, governments,

universities, public museums and related institutions should

consider making duplicate, common and unwanted artifacts

available to the public for sale.

Government agencies responsible for management of

archaeological sites and artifacts in antiquities rich countries

- nations whose long histories of human occupation have left them

with considerable archaeological and architectural remains -

have found themselves increasingly pressed to adequately store

and preserve the wealth of archaeological materials excavated or

accidentally unearthed in their territories. The situation has

been described as “a crisis in curation” and that “the problem

continues to be widespread and serious” (Kersel 44). Many of

Maupin 2

these nations once participated in a system known as “partage”

under which foreign archaeological missions divided duplicate or

similar objects between themselves and national heritage and

museums agencies. With the end of European colonialism and a rise

in nationalist sentiment in many of these countries, the partage

system came to an end and all antiquities stayed in the host

nations. This helped fuel the storage crisis (Kersel 48).

This crisis is not limited to developing nations

rich in antiquities but to economically postmodern western

nations as well. At the most recent “Dig It!” conference in

London, museum professionals and archaeologists met to discuss

the crisis of storage for archaeological collections in the UK.

Despite much debate, no practical solutions were arrived at

(Sharpe).

Just as a crisis exists in storing archaeological

materials, another crisis is slowly unfolding for national

heritage agencies and research institutions in funding both

routine ongoing archaeological excavations and rescue

archaeology, and with such basic tasks as maintenance of ancient

monuments and the publication of archaeological excavation

Maupin 3

reports. Sometimes referred to as “archaeology’s dirty secret,”

the failure to publish excavation results can be said to reduce

archaeologists to little more than looters (Kersel 46). This is

true both in antiquities rich Mediterranean and Near Eastern

nations, where widespread political instability has frightened

away outside funding sources, even in specific countries that

have remained stable, and in developed European nations, where

national priorities have shifted in light of fiscal belt

tightening. “Archaeology in England is in the middle of its worst

crisis ever” was the pronouncement in a recent blog entry by a

prominent British academician (Nevell).

At archaeological sites all across the

Mediterranean world and beyond, remains that have been excavated,

published and restored over the past century or more have begun

to fall victim to official neglect. One site, in particular, has

garnered a great deal of attention due to its high profile:

Pompeii. Visited by as many as two and a half million tourists

and locals per years, the site has suffered extensively at the

hands of the very tourists whose revenues support it and through

wasteful and indifferent practices by the Italian governmental

Maupin 4

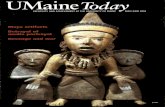

agency tasked with its preservation. The photographs below make

this point very clear. In the first image, a frescoed wall of the

mid-First Century AD is shown covered in graffiti scratched into

its surface by Italian school children and foreign tourists

(Personal photograph).

In the second image, a storage pen for excavated materials is

open to the weather, allowing complete and fragmentary Roman

transport vessels, roof tiles and even a lead cinerary container

to slowly crumble due to lack of climate control (Personal

photograph).

Maupin 5

Despite a legal market for antiquities in most

European and North American countries, there is also an illicit

market, involving the illegal removal of artifacts for profit,

and it thrives in times of political upheaval. Egypt, Syria and

Iraq have all fallen victim to this practice in recent years. To

many people involved in archaeology and cultural heritage

protection, the importance of this problem far outweighs the

other issues raised above. While evidence suggests that the

actual extent of illicit excavation in most countries is not as

severe as sensationalist media reports would suggest (Proulx 17-

18), there can be no doubt that in times of conflict and

Maupin 6

political instability the problem is exacerbated. The well-heeled

cultural heritage “industry” and the archaeological community

have sought to associate this trade (which is primarily carried

out by impoverished locals when conflicts impede their

livelihoods, and who are primarily seeking precious metals that

may be easily transported or melted down) with organized crime on

an international scale (Massey 732-33). Both communities have

made many imperious pronouncements, seeking to take the moral

high ground in the debate over antiquities, but have offered

little in the way of practical solutions to this illicit trade.

In a 2003 interview, Jane Waldbaum of the Archaeological

Institute of America said simply “We do not support a legal trade

in antiquities. Period” (Tierney).

Although the crises outlined above can only be

solved through multiple solutions, there is one proposal that can

address, at least in part, all of them: Selling, using a

carefully monitored and documented methodology, duplicate or

common antiquities to help reduce the artifact storage problem,

generate much needed revenue for archaeological digs and research

Maupin 7

by national heritage agencies and universities and help to

undercut the illicit trade in antiquities.

The assertion that duplicate archaeological

objects that have little or no practical research value, after

being recorded and placed in storage, could be sold to benefit

archaeology, museums and heritage protection is not a new one. It

has proven to be a highly controversial suggestion, arousing

powerful emotional responses from the archaeological, historic

preservation, cultural heritage, museum and antiquities dealer

communities. In view of the recent unprecedented acts of

religiously motivated destruction of archaeological resources in

the Middle East, the continuing decay of World Heritage sites in

Italy such as Pompeii and the gradual shifting of financial

priorities in most countries away from culture, the arts and

heritage, the time has come to examine this idea seriously.

The most credible proposal of this type came from

a most unexpected source. The late Israeli archaeologist Avner

Raban, a highly respected scholar and field archaeologist with

forty years experience, rocked the archaeological world in 1997

with an article entitled “Stop the Charade: It’s Time to Sell

Maupin 8

Artifacts” (42). Raban proposed that Israel and other

Mediterranean countries should permit the sale of artifacts from

legal archaeological excavations following their publication in

scientific journals. Specifically, he proposed that such sales be

governed by clearly defined rules that included triplicate

documentation of each object (one to the government archives, one

to the excavating institution and one to the purchaser) and a

prioritization of objects that sent unique items to national or

regional museums and less important items to university or other

study collections for further research or display. Only the

remaining objects might be sold on the legal antiquities market

through authorized dealers. To guarantee the items would be

traceable for future study, each object would also bear the

excavation permit number, a registry number and locus number -

the precise location of the find within the excavation (45).

The logic behind Raban’s proposal was that objects

with such precise documentation, even if they tended to be very

common types, would fetch far greater sums on the open market

than objects with no clear provenance, a concept that this writer

can attest to through personal experience. The revenue thus

Maupin 9

generated for archaeological projects, storage, display and

additional curatorial research would also change the perception

of the antiquities buying community from facilitators of looting

to benefactors of archaeology. In addition to undercutting the

illicit trafficking in such objects, Raban’s proposal would also

make it more difficult for forgers to ply their trade (45).

Of course, entrenched interests continue to oppose

ideas such as Raban’s, the most obvious of these being the

professional associations representing the established

archaeological community. These special interests cling to

outmoded nationalistic concepts of cultural patrimony because

doing so facilitates obtaining excavation permits in host

countries. In a recent New York Times piece, J. Paul Getty Trust

Chief Executive James Cuno addressed the issue of repatriating

art and artifacts to nations on the basis of “national identity”

claims, which he argues cannot be adjudicated, only debated. He

argues that the notion of “cultural heritage” is a construct of

modern nation states and therefore not relevant to archaeological

context (Cuno). And in a remarkable break with much of the

academic community, Sir John Boardman, Emeritus Professor of Art

Maupin 10

and Archaeology at Oxford University and widely recognized as the

world’s greatest living authority on ancient Greek vase painting,

posed the question: “So who do these archaeologists think they

are, as absolute guardians of the world’s heritage?” (qtd. in

“Some Scholar’s Opinions”). He criticizes at length the

archaeological community for failure to publish excavation

reports, comparing an unpublished excavated site to the

destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, and for their complicity in

supporting, through their silence in the interest of receiving

excavation permits, tyrannical regimes in antiquities rich

nations. Despite such criticisms, the archaeological community

continues to resist any innovative proposals such as Raban’s that

might appear to lessen their grip on the past.

Since Raban’s original article, similar

ideas have been floated again. Herschel Shanks, publisher of

Biblical Archaeology Review magazine, said in 2003, following the

looting of the Iraq Museum, ''Archaeologists like taking the high

moral ground against selling antiquities, but it doesn't solve

the problem of looting. I would like to use market solutions.

Sell very common objects, like oil lamps or little pots, and use

Maupin 11

the money to pay for professional excavations'' (Tierney). And at

the recent “Dig It!” conference in London, an audience member

asked if museums should sell excess material in their shops. The

panel unanimously replied in the negative (Sharpe).

Despite the resistance, ideas similar to

Raban’s may soon prove to be the only viable option for dealing

with the issues outlined above. Time, space and funds are running

short for archaeologists, museums and the past itself.

Works Cited

Kersel, Morag M. “Storage Wars: Solving the Archaeological

Curation Crisis?” Journal of

Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies 3.1 (2015): 42-54.

Print.

Massey, Laurence. “The antiquity art market: between legality and

illegality.” International

Journal of Social Economics 35.10 (2008): 729-738. Print.

Maupin 12

Nevell, Mike. “Archaeology in Crisis.” Archaeologyuos. Wordpress, 7

Apr. 2014. Web.

Pompeii, Italy. Personal Photographs by Author. December, 2002,

JPEG files.

“Pompeii to Receive Italy Rescue Fund.” BBC News. BBC, 4 Mar.

2014. Web.

Proulx, Blythe Bowman. “Organized crime involvement in the

illicit antiquities trade.” Trends in

Organized Crime 14.1 (2010): 1-29. Print.

Raban, Avner. “Stop the Charade: It’s Time to Sell Artifacts.”

Biblical Archaeology Review 23.3

(1997): 42-43. Print.

Sharpe, Emily. “An embarrassment of riches: UK museums struggle

with archaeological

Archives.” The Art Newspaper. theartnewspaper.com, 6 Mar.

2015. Web.

“Some Scholar’s Opinions.” International Association of Dealers

in Ancient Art. n.d. Web.

Accessed 15 Mar. 2015.