Reducing Cheating Opportunities in Online Test - Digital ...

Self-Reports of Student Cheating: Does a Definition of Cheating Matter?

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Self-Reports of Student Cheating: Does a Definition of Cheating Matter?

Winter 2007 3

Self-Reports of Student Cheating:Does a Definition of Cheating Matter?

Robert T. Burrus, KimMarie McGoldrick, and Peter W. Schuhmann

Abstract: The authors examine student cheating based on implicit and explicit

definitions of cheating. Prior to being provided a definition of cheating, students

reported whether they had cheated. Students were then provided a definition of

cheating and asked to rereport their cheating behaviors. Results indicate that stu-

dents do not understand what constitutes cheating and are much more likely to

report cheating postdefinition. In addition, both pre- and postdefinition cheating

behaviors are more prevalent for students with lower GPAs and for those who per-

ceive more cheating by student peers. Alcohol consumption, seeing another stu-

dent cheat, fraternity/sorority membership, and athletic membership also increase

the likelihood of cheating. These findings are consistent with previous studies. On

the basis of a sample of students who provided cheating data after a definition of

cheating is communicated, the authors find that students who believe that pun-

ishment for cheating is relatively severe are less likely to report cheating and that

students at institutions with well-publicized honor codes are less likely to admit

to cheating compared with students at nonhonor code institutions.

Key words: cheating, crime, honor code

JEL codes: A22, K42

Authors of most studies have found that classroom cheating occurs frequently,

with as many as 50 to 75 percent of students admitting to cheating (Baird 1980;

Robert T. Burrus (e-mail: [email protected]) and Peter W. Schuhmann are associate professors ofeconomics at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, and KimMarie McGoldrick is an asso-ciate professor of economics at the University of Richmond. Copyright © 2007 Heldref Publications

In this section, the Journal of Economic Education publishes original theo-retical and empirical studies of economic education dealing with the analysisand evaluation of teaching methods, learning, attitudes and interests, materials,or processes.

PETER KENNEDY, Section Editor

Research in Economic Education

Singhal 1982; Meade 1992; Franklyn-Stokes and Newstead 1995) and 50 to 70

percent of faculty reporting that they have observed cheating in their classroom

(Stevens and Stevens 1987; Stern and Havlicek 1986). Study results suggest that

many factors influence student cheating. These study results indicate that indi-

vidual student characteristics1 and their academic environment2 affect cheating

behavior. Programs such as student honor codes have also been shown to affect

cheating behavior, perhaps because honor codes reduce the perception that other

students are cheating (McCabe and Trevino 1993).

Cheating among college students has been examined through formal economic

modeling. In particular, student cheating is likened to other types of criminal

behavior, in which the rational agent weighs the costs and benefits of a criminal

action (Becker 1968). Bunn, Caudill, and Gropper (1992) acknowledged, how-

ever, two main differences between societal crimes like theft and classroom

crime. First, professors can affect the costs of crime in ways that police cannot.

Professors can disperse students, make different versions of exams, and can mon-

itor behavior much more closely than can local enforcement officers—activities

that have been confirmed to reduce student cheating (Hollinger and Lanza-

Kaduce 1996). Second, because exam answers are similar to public goods, the

victims of cheating are not necessarily made worse off by the cheaters. It is not

surprising that Houston (1986) found a positive relation between cheaters and the

degree of acquaintance of the victim.

In this study, we consider a third difference between societal crime and class-

room cheating. Societal laws are usually explicit whereas there is often a degree

of ambiguity concerning the behaviors that are considered student cheating. In an

attempt to clarify what constitutes cheating, institutions often provide a statement

of cheating behaviors that includes specific definitions. For example, the defini-

tion of cheating that was presented to students for the current study was directly

quoted from the student handbook of one of the two institutions considered and

stated that cheating is defined as any one of the following: (a) the submission of

work that is not one’s own; (b) the giving or receiving of illegal aid from other

persons or materials or from materials brought into the classroom by you (such

as looking at someone else’s paper or “cheat sheets”); (c) the use of prior knowl-

edge of the contents of the test or quiz without authorization from the instructor—

“Knowledge of the contents” can include conversation about the test with

students who already have completed it or unauthorized viewing of the test paper.

Even with this provided definition, some students failed to consider discussing

a take-home exam with other students as cheating unless the instructor explicitly

defined the behavior as cheating. Gardner, Roper, and Gonzalez (1988) found that

surveys underestimate student cheating as cheaters often claim that they do not

cheat. This finding is, perhaps, a result of students failing to recognize the full set

of behaviors that constitute cheating.

The degree of interpretation ambiguity in cheating definitions has been noted

in Wright and Kelly (1974); Barnett and Dalton (1981); Graham et al. (1994).

Those study results generally indicate that students and faculty agree about the

most severe or obvious forms of cheating (copying from other student’s exams,

using cheat sheets, and turning in research that is not one’s own) but disagree

4 JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC EDUCATION

concerning which other behaviors are cheating (plagiarism and bibliographical

misrepresentation, working with other students on homework when it has been

expressly forbidden, using an old test to study without the teacher’s knowledge,

and getting questions or answers about an exam from someone who has already

taken it). This ambiguity affects behavior as indicated by Franklyn-Stokes and

Newstead (1995), who found an inverse relationship between the perception of

a behavior as cheating and the likelihood that students will cheat in that way.

They concluded that clear and consistent definitions of acceptable and unac-

ceptable behaviors would likely decrease undesirable academic behaviors.

In a framework similar to those employed by Bunn, Caudill, and Gropper

(1992), Mixon and Mixon (1996), and Mixon (1996), we sought to determine the

degree to which a provision of a definition of cheating influenced cheating behav-

ior, ceteris paribus. We extended previous research by considering cheating

reported by the student respondent prior to provision of a formal definition and

cheating reported after provision of a definition. Using probit specifications, we

modeled the probability of cheating. A comparison of reported cheating instances

before and after the aforementioned definition was provided sheds light on the

issue of whether a formal definition of cheating affects the relationships between

cheating and the explanatory variables.

An important issue in all studies that rely on survey data is that survey responses

are likely to contain reporting errors. This is especially true in the case of self-

reported cheating behavior by students. In an attempt to ensure truth in reporting,

Kerkvliet (1994) employed a randomized response technique to nearly 200 princi-

ples of economics students and found that 42 percent of students reported cheat-

ing, using a randomized response technique, whereas only 25 percent reported

cheating, using a direct question survey. Kerkvliet pointed out that the randomized

response survey method decrease sample size as only a portion of the surveyed stu-

dents answered the sensitive cheating questions. By providing a definition of

cheating to all surveyed students, our study sought to elicit more accurate cheat-

ing data without decreasing the size of the sample. However, we acknowledge that

lack of complete anonymity may have introduced biases noted by Kerkvliet.

This research is, therefore, important for two reasons. First, if colleges and uni-

versities are serious about minimizing cheating, they must first understand the

disparity between student and faculty definitions of cheating, and, next, they must

seek cost-effective means to reduce the disparity. Second, because our results

indicated that many students were unaware of what cheating is, research investi-

gating cheating behavior via student surveys may be forming erroneous conclu-

sions in cases where a formal definition of cheating was not provided.

DATA AND SURVEY DESIGN

In spring 2000, over 384 principles of economics students at two U.S. univer-

sities, The University of Richmond (UR) and the University of North Carolina

Wilmington (UNCW), were surveyed to gather information on cheating.3

Participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous. One unique aspect in

the comparison of these two institutions is that UR has a very formal and

Winter 2007 5

integrated honor system in which students face frequent reminders of the impor-

tance of academic honesty whereas UNCW does not. After removing incomplete

surveys, a maximum of 300 (UR, 106; UNCW, 194) usable observations com-

posed our sample.4 In the survey, students were asked to provide demographic

and general scholastic information and their perceptions on academic dishonesty

and the certainty and severity of punishment for cheating. Students were also

asked about the frequency of their personal cheating, using their own standards

of what constitutes cheating and were asked again following the provision of the

definition of cheating given above. Variable names, definitions, and descriptive

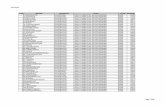

statistics are reported in Table 1 for the entire sample and by institution.

Using the midpoint of the grade point average (GPA) categories, we found the

average student GPA to be nearly 3.0. Twenty-nine percent of respondents were

members of a fraternity or sorority (FRATSOR), and 10 percent were athletes

(ATHL). Students reported drinking an average of six alcoholic beverages

(ALCOHOL) each week. Eighty-three percent of students believed they were

honest (HONEST). Seventy-one percent of respondents had witnessed cheating

at the college level (SEECHEAT), but only 20 percent had witnessed someone

getting caught for cheating (CCAUGHT).

Students were also asked about their perceptions concerning the degree to

which cheating occurs on their campus, the certainty and severity of punishment

for cheating, and their attitudes concerning the appropriateness of cheating. Fifty-

five percent of students believed that cheating occurred only on occasion or never

(OCCASION), whereas 13 percent believed that cheating occurred very often

(VOFTEN). Only 15 percent believed that the probability of being caught cheat-

ing was 25 percent and above (25CAUGHT � 50CAUGHT � 75CAUGHT).

Forty-eight percent of students believed that between 0 and 25 percent of student

cheaters got caught (0CAUGHT). Forty-four percent of students thought that

punishment for cheating at their college was severe (SEVPUNISH).

As expected, students reported significantly more cheating after the formal def-

inition of cheating was provided (PNCHEAT), with an average of 3.32 incidences

in the last 12 months compared with the predefinition number (NCHEAT) of 1.8;

thus, students tended to underreport cheating behavior when a definition of cheat-

ing was not given. The percentage of students reporting at least one incident of

cheating (CHEATER) also increased from 39 percent to 53 percent after the def-

inition was provided (PCHEATER). The increase in the percentage of students

reporting cheating was similar to the increase in cheating behavior discovered by

the use of randomized response surveys (Kerkvliet 1994).

Interpretation of these results is confounded by the fact that students in the two

institutions are mixed in their interpretations of what behaviors constitute cheating.

Prior to the provision of the definition of cheating, our survey elicited opinions on

the behaviors that students considered as cheating. We note that some of these behav-

iors may not constitute cheating in all circumstances and that the policies of indi-

vidual instructors may change the context of what constitutes cheating in a particular

class. Nonetheless, the responses to these questions provided insight into student’s

perceptions. Although a majority of students (93 percent) defined glancing at the test

or quiz of the students sitting next to them to compare their answers as cheating

6 JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC EDUCATION

Winter 2007 7

TA

BL

E 1

. Var

iabl

e N

ames

and

Def

init

ions

Var

iable

Def

init

ion

Tota

lU

RU

NC

W

GPA

G.P

.A.

inte

rval

s “b

elow

1.7

5,”

“1.7

5 t

o 1

.99,”

“2.0

to 2

.249,”

“2.5

to 2

.749,”

“2.7

5 t

o

2.9

83.0

52.9

42.9

9,”

“3.0

0 t

o 3

.249,”

“3.2

5 t

o 3

.499,”

“3.5

to 3

.749,”

and “

7.7

5 t

o 4

.00”

are

coded

as

1.6

25,

1.8

75,

2.1

25,

2.3

75,

2.6

25,

2.8

75,

3.1

25,

3.3

75,

3.6

25,

and 3

.875,

resp

ecti

vely

.F

RA

TS

OR

(%

)1 �

frat

ernit

y/s

oro

rity

mem

ber

; 0 �

nonm

ember

28.6

720.1

044.3

4A

LC

OH

OL

(n)

num

ber

of

alco

holi

c dri

nks

consu

med

per

wee

k—

“11 o

r m

ore

”is

coded

as

11 (

not

%)

6.0

97.1

15.5

3A

TH

L (

%)

1 �

athle

te;

0 �

nonat

hle

te10.0

015.0

97.2

2H

ON

ES

T (

%)

1 �

studen

t co

nsi

der

s th

at h

e/sh

e is

hones

t;

0 �

oth

erw

ise

83.0

082.0

883.5

1S

NH

ON

ES

T (

%)

1 �

studen

t co

nsi

der

s th

at h

e/sh

e is

som

ewhat

hones

t or

not

hones

t;

0 �

oth

erw

ise

17.0

017.9

316.5

0S

EE

CH

EA

T (

%)

1 �

studen

t has

wit

nes

sed c

hea

ting;

0 �

oth

er71.3

362.2

676.2

9O

CC

AS

ION

(%

)1 �

chea

ting o

ccurs

only

on o

ccas

ion o

r nev

er;

0 �

oth

er54.6

762.2

650.5

2P

ER

IOD

IC (

%)

1 �

chea

ting i

s per

iodic

; 0 �

oth

er

32.6

730.1

934.0

2V

OF

TE

N (

%)

1 �

chea

ting o

ccurs

ver

y o

ften

; 0 �

oth

er12.6

77.5

515.4

6C

CA

UG

HT

(%

)1 �

studen

t has

wit

nes

sed a

chea

ter

get

cau

ght;

0 �

oth

er19.6

712.2

623.7

175C

AU

GH

T (

%)

1 �

over

75%

of

chea

ters

get

cau

ght;

0 �

oth

er3.6

73.7

73.6

150C

AU

GH

T (

%)

1 �

bet

wee

n 5

0 a

nd 7

5%

of

chea

ters

get

cau

ght;

0 �

oth

er2.3

30.9

43.0

925C

AU

GH

T (

%)

1 �

bet

wee

n 2

5 a

nd 5

0%

of

chea

ters

get

cau

ght;

0 �

oth

er9.3

39.4

39.2

80C

AU

GH

T (

%)

1 �

bet

wee

n 0

and 2

5%

of

chea

ters

get

cau

ght;

0 �

oth

er48.3

357.5

543.3

0D

KC

AU

GH

T (

%)

1 �

don’t

know

per

centa

ge

of

chea

ters

that

get

cau

ght;

0 �

oth

er36.3

328.3

040.7

2S

EV

PU

NIS

H (

%)

1 �

punis

hm

ent

for

chea

ting i

s se

ver

e; 0

�oth

er44.3

360.3

835.5

7M

OD

PU

NIS

H (

%)

1 �

punis

hm

ent

for

chea

ting i

s m

oder

ate;

0 �

oth

er29.6

724.5

332.4

7M

ILD

PU

NIS

H (

%)

1 �

punis

hm

ent

for

chea

ting i

s m

ild;

0 �

oth

er7.0

02.8

39.2

8D

KP

UN

ISH

(%

)1 �

punis

hm

ent

for

chea

ting i

s unknow

n;

0 �

oth

er19.0

012.2

622.6

8N

CH

EA

T (

n)

Num

ber

of

epis

odes

of

chea

ting e

pis

odes

rep

ort

ed p

rior

to t

he

pro

vis

ion o

f a

def

init

ion

1.8

02.1

51.6

1of

chea

ting

(Tab

le c

onti

nues

)

8 JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC EDUCATION

TA

BL

E 1

. Con

tinue

d

Var

iable

Def

init

ion

Tota

lU

RU

NC

W

PN

CH

EA

T (

n)

Num

ber

of

chea

ting e

pis

odes

rep

ort

ed p

ost

the

pro

vis

ion o

f a

def

init

ion

3.3

22.9

93.5

0of

chea

ting

CH

EA

TE

R (

%)

1 �

indic

ated

chea

ting b

efore

the

def

init

ion o

f ch

eati

ng w

as p

rovid

ed;

0 �

oth

er38.7

35.8

540.2

1P

CH

EA

TE

R (

%)

1 �

indic

ated

chea

ting a

fter

the

def

init

ion o

f ch

eati

ng w

as p

rovid

ed;

0 �

oth

er53.0

42.4

558.7

6L

OO

KPA

PE

R (

%)

1 �

gla

nci

ng a

t an

oth

er s

tuden

t’s

quiz

or

exam

is

chea

ting;

0 �

this

beh

avio

r is

not

93.0

095.2

891.7

5ch

eati

ng

TA

KE

HO

ME

(%

)1 �

askin

g a

cla

ssm

ate

a ques

tion a

bout

a ta

ke-

hom

e ex

am i

s ch

eati

ng;

0 �

this

42.3

374.5

324.7

4beh

avio

r is

not

chea

ting

OL

DT

ES

T (

%)

1 �

usi

ng a

tes

t or

quiz

fro

m a

pre

vio

us

sem

este

r to

stu

dy i

s ch

eati

ng;

0 �

this

beh

avio

r 19.3

331.1

312.8

9is

not

chea

ting

CO

MP

HW

(%

)1 �

com

par

ing h

om

ework

answ

ers

wit

h a

cla

ssm

ate’

s pri

or

to c

lass

is

chea

ting;

0 �

this

9.3

315.0

96.1

9beh

avio

r is

not

chea

ting

AS

KH

W (

%)

1 �

askin

g f

or

hel

p f

rom

a c

lass

mat

e on t

he

assi

gned

hom

ework

is

chea

ting;

0 �

this

2.3

34.7

21.0

3beh

avio

r is

not

chea

ting

UR

(%

)1 �

studen

t at

tends

the

Univ

ersi

ty o

f R

ichm

ond;

0 �

studen

t at

tends

the

Univ

ersi

ty o

f 35.3

3N

/AN

/AN

ort

h C

aroli

na

Wil

min

gto

n

Not

e.G

PA �

gra

de

poin

t av

erag

e; U

R �

Univ

ersi

ty o

f R

ichm

ond;

UN

CW

�U

niv

ersi

ty o

f N

ort

h C

aroli

na-

Wil

min

gto

n.

(LOOKPAPER), only 42 percent believed that asking a classmate a question about

a take-home exam (TAKEHOME) was cheating. Nineteen percent believed that

studying from an old exam was cheating (OLDTEST), whereas 9 percent and 2 per-

cent, respectively, believed that comparing homework answers with a classmate’s

prior to class (COMPHW) and asking for help from a classmate on the assigned

homework (ASKHW) were cheating behaviors. We found that a statistically higher

proportion of students from UR reported that each of the aforementioned behaviors

was cheating, except in the case of LOOKPAPER (where the proportion was higher

for UR students but not significantly so). In other words, a higher proportion of stu-

dents at UR judged these behaviors to be cheating. These differences are detailed in

the last two columns of Table 1 and are quite large in most cases. We attributed these

differences to a heightened awareness of the honor code at UR. As McCabe and

Trevino (1997, 384) put it, institutions with formal honor codes that “are widely dis-

tributed and understood by members of the academic community” are “an integral

part of the campus culture.” Other institutions do have honor codes, but these codes

are “tucked away in campus policy manuals that are rarely read (p. 384).”

Consequently, we also expected that the students at UNCW, the institution with-

out a formal honor code, would be less likely to report that they were cheaters and

would report fewer incidences of cheating in the past 12 months. That is, we

hypothesized that although the actual frequency of academic dishonesty at the two

institutions may be similar, students at the university with a formal honor code

would be more aware that they were actually cheating. The latter of these expec-

tations was confirmed. Students at UR reported a significantly higher incidence of

cheating (an average of 2.15) than students at UNCW (1.61) prior to the provision

of the cheating definition. After the definition of cheating was provided, however,

UNCW students reported significantly more incidences of cheating compared with

UR students (3.50 to 2.99). In addition, 35.85 percent of the UR students reported

at least one incidence of cheating prior to the provision of the definition compared

with 40.21 percent of the UNCW students. After the definition was given, 42.45

percent of the UR students reported that they were cheaters whereas 58.76 percent

of the UNCW students reported that they had cheated. Hence, UNCW students

were not only less likely to report even grievous behaviors such as discussing a

take-home exam as cheating, but were also more likely to underreport cheating

incidences if a definition of cheating is not provided.

MODEL

To examine the factors that influence the probability of cheating both before

and after a definition is provided, we estimated the following equation, using a

bivariate probit specification:

Yi � �0 � �1(GPAi) � �2(FRATSORi) � �3(ATHLi) � �4(HONESTi)

� �5(ALCOHOLi) � �6(SEECHEATi) � �7(CCAUGHTi)

� �8(SEVPUNISHi) � �9(MODPUNISHi) � �10(DKPUNISHi) (1)

� �11(PERIODICi) � �12(VOFTENi) � �13(75CAUGHTi)

� �14(50CAUGHTi) � �15(25CAUGHTi) � �16(DKCAUGHTi) � �17(URi).

Winter 2007 9

We had two values of the dependent variable for each individual. CHEATER (� 1

if the student indicated cheating prior to the provision of a definition), and PCHEATER

(� 1 if they indicated cheating after the provision of a definition) were used as

dependent variables. Hence, in equation (1), Yi � 0, if the student reported zero inci-

dences of cheating in the past 12 months (pre- or postdefinition) and � 1 otherwise.

These two values will be different only if the provision of the definition caused

students to realize they had been cheating when they previously thought otherwise.

Obviously, the two values of the dependent variable may be correlated; hence,

a standard probit model may result in biased coefficient estimates. The bivariate

probit model was a simultaneous equations model that controlled for the correla-

tion between the two related choices; thus, the bivariate probit model might pro-

vide more efficient estimates. Further, because the bivariate probit model

estimated the pre- and postcheating responses simultaneously, it allowed for a

meaningful statistical comparison of the parameter estimates between the two

models.5 We could therefore gain insight into whether the influence of factors that

affect cheating was different between the pre- and postdefinition models.

HYPOTHESES

The literature generally suggests that individual student characteristics affect

cheating behavior. For example, students with higher GPAs will be less likely to

cheat because they will have less to gain and more to lose from cheating.6 We

anticipated that in both the pre- and postdefinition regressions the GPA variable

would be negative and significant. On the basis of the results in Houston (1986),

who showed that cheating usually occurs between acquaintances, we anticipated

that students belonging to a fraternity or a sorority (FRATSOR) or who were

involved in athletics (ATHL) were more likely to cheat than other students. These

hypotheses were also supported by Baird (1980), Kerkvliet (1994), Genereux and

McLeod (1995), McCabe and Bowers (1996); and McCabe and Trevino (1997).

Following the results in Kerkvliet (1994), we expected a positive relationship

between the amount of alcohol consumed by students (ALCOHOL) and cheating

behavior. Students who considered themselves to be more honest (HONEST)

were expected to be less likely to cheat than were students who considered them-

selves only somewhat honest or not honest.

Environmental considerations may also affect cheating behavior. The literature

suggests that student observations of cheating-related behaviors may have the

greatest impact on student cheating behavior. Similar to the studies of Bunn,

Caudill, and Gropper (1992), Mixon and Mixon (1996), and Mixon (1996), we

expected that students who had witnessed cheating (SEECHEAT) would be more

likely to cheat, whereas, if they witnessed a cheater being caught (CCAUGHT),

they would be less likely to cheat. Likewise, cheating behavior was influenced by

the degree to which students perceived that cheating occurs. PERIODIC and

VOFTEN are a set of categorical indicator variables representing perceptions

about how frequently cheating occurs, with cheating occurring on occasion or

never as the omitted category. The parameter estimates for these variables were

expected to be positive and increasing.

10 JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC EDUCATION

To compare current results with previous research that examined the degree to

which the certainty and severity of punishment affected student cheating, we con-

structed a set of categorical dummies representing student perceptions of the

severity of punishment. SEVPUNISH, MODPUNISH, and DKPUNISH are equal

to one if the student perceived the punishment for cheating as severe, moderate, or

unknown and equal to zero otherwise. MILDPUNISH is the omitted category.

SEVPUNISH and MODPUNISH were expected to be negative in both the pre-

and postdefinition regressions. DKPUNISH may, however, produce a positive or

negative parameter estimate as a student who was uncertain of the punishment for

cheating may be expected to be more likely to cheat than students who thought

punishment was severe but less likely to cheat than a student who thought punish-

ment was mild. To capture the effect of student perceptions of the certainty of pun-

ishment, we also included a set of variables representing the percentage of cheaters

that the student respondent believed would be caught. The variables 75CAUGHT,

50CAUGHT, and 25CAUGHT indicate that more than 75 percent, between 50 per-

cent and 75 percent, between 25 percent and 50 percent of cheaters would be

caught, respectively, whereas DKCAUGHT indicates that the respondent was

unsure of the certainty of punishment. 0CAUGHT, a variable that indicates that

between zero and 25 percent of cheaters would be caught, is the omitted category.

The regression coefficients for these indicator variables were expected to be neg-

ative and to decrease in absolute value moving from higher to lower percentages.

Again, we had no clear expectation regarding the sign of DKCAUGHT.

Finally, to control for differences across the two universities, we included a

dummy variable for UR. Because this school has a formal honor code, we antic-

ipated a negative sign for this variable in both the pre- and postdefinition regres-

sions; however, this variable may simply capture other differences between the

two universities.

Specifying the model using pre- and postdefinition dependent variables allowed

for interesting comparisons. For example, we anticipated that the coefficient on the

UR dummy variable would increase in absolute value between the pre- and post-

definition specifications because the change between pre- and postdefinition

cheating incidences was higher for UNCW than for UR. It was difficult to predict

how the other coefficient signs would change from the predefinition specifications

to the postdefinition specifications. Obviously, a coefficient estimate that was

larger and more significant in the postdefinition regressions represented a variable

that had more influence on cheating behavior than was indicated by the predefin-

ition estimate. These changes might result from students being better informed

about the behaviors that constituted cheating postdefinition.

RESULTS

The results of the bivariate probit model are reported in Table 2. Because the

probit coefficients had no direct interpretation, we also report marginal effects.7

Most of the signs were in the direction predicted. The highly significant rho vari-

able showed that the unobservable characteristics that influenced whether a stu-

dent admited to cheating in the predefinition model also affected the cheating

Winter 2007 11

12 JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC EDUCATION

TA

BL

E 2

. Biv

aria

te P

robi

t M

odel

Res

ults

wit

h C

HE

AT

ER

and

PC

HE

AT

ER

as

Dep

ende

nt V

aria

bles

.

Pre

def

init

ion

Post

def

init

ion

Var

iable

Rt

Mar

gin

al e

ffec

tR

tM

argin

al e

ffec

t

INT

ER

CE

PT

0.5

925

0.8

79

2.0

842

2.6

59*

GPA

–0.3

877

–2.0

46**

–0.0

668

–0.4

932

–2.7

90*

–0.0

600

FR

AT

SO

R0.4

447

1.9

81**

0.1

047

0.4

638

2.1

43**

0.0

406

AL

CO

HO

L0.0

368

1.5

83

0.0

070

0.0

445

2.0

00**

0.0

051

AT

HL

1.1

130

2.8

76*

0.3

477

0.5

432

1.6

41***

–0.0

336

HO

NE

ST

–0.8

913

–3.8

76*

–0.2

778

–0.5

672

–2.0

65**

–0.0

021

SE

EC

HE

AT

1.0

532

3.3

85*

0.3

488

0.6

955

3.2

35*

–0.0

030

PE

RIO

DIC

0.2

983

1.4

00

0.0

405

0.4

277

2.0

34**

0.0

541

VO

FT

EN

0.6

393

2.3

76**

0.2

595

0.1

591

0.4

75

–0.0

692

CC

AU

GH

T–0.2

863

–1.2

83

–0.1

646

0.0

668

0.2

93

0.0

556

CA

UG

HT

75

0.0

377

0.0

56

0.0

007

0.0

703

0.1

47

0.0

110

CA

UG

HT

50

–0.6

894

–0.8

69

–0.2

819

–0.2

502

–0.4

57

0.0

458

CA

UG

HT

25

–0.3

375

–1.0

91

–0.1

464

–0.1

074

–0.3

27

0.0

273

DK

CA

UG

HT

–0.4

885

–2.3

23**

–0.1

524

–0.3

692

–1.7

53***

–0.0

118

SE

VP

UN

ISH

0.0

369

0.1

05

0.2

176

–0.7

401

–1.6

28***

–0.2

110

MO

DP

UN

ISH

–0.0

837

–0.2

29

0.2

275

–0.9

566

–2.0

63**

–0.3

057

DK

PU

NIS

H–0.4

723

–1.1

77

0.0

802

–1.0

819

–2.1

87**

–0.2

852

UR

–0.3

396

–1.5

91

–0.0

025

–0.6

220

–2.8

04*

–0.1

124

�0.7

966

11.2

87*

LL

–276.2

184

Res

tric

ted L

L–347.9

074

�143.3

78*

Not

e.C

HE

AT

ER

�1 i

f in

dic

ated

chea

ting p

rior

to t

he

pro

vis

ion o

f a

def

init

ion;

PC

HE

AT

ER

�1 i

f in

dic

ated

chea

ting a

fter

the

pro

vis

ion o

f a

def

init

ion.

*In

dic

ates

sig

nif

ican

t at

.01 T

ype

I er

ror

level

,**in

dic

ates

sig

nif

ican

t at

.05 T

ype

I er

ror

level

,***in

dic

ates

sig

nif

ican

ce a

t .0

10 T

ype

I er

ror

level

.

response after a definition was given. In other words, we rejected the null

hypothesis that the two equations were uncorrelated; the model did not consist

of independent probit equations that could be estimated separately.

Ignoring for the moment the impact of perceptions of the certainty and sever-

ity of punishment for cheating, there are several interesting and consistent demo-

graphic results across the bivariate probit pre- and postdefinition equations.8

Students with higher GPAs and students who believe that they are honest are less

likely to be cheaters (Table 2). Students who participate in Greek organizations

and university athletics and who have witnessed other students cheating are more

likely to be cheaters. These results are consistent with previous research.9

Student characteristics that were significant in the postdefinition equation but

not in the predefinition equation include alcohol consumption and whether a stu-

dent considers cheating to be periodic rather than only on occasion. This suggests

that these variables significantly affect whether a student cheats only if students

are enlightened when providing self-reported cheating data.10 The belief that

cheating occurs very often only significantly affects whether a student is a cheater

in the predefinition equation. Witnessing a student being caught for cheating was

the only demographic characteristic that did not significantly affect whether a stu-

dent is a cheater in either the pre- or postdefinition equations. This is consistent

with Mixon and Mixon (1996) and Bunn, Caudill, and Gropper (1992) although,

in our results, the signs for these parameters were in the direction predicted.11

We now consider variables representing perceptions about the certainty and

severity of punishment. Across both equations, there is no indication that students

who believed that the probability of being caught cheating was higher than 25

percent were less likely to cheat than students who believed that the probability

of detection was lower than 25 percent. On the other hand, uncertainty about the

likelihood of detection significantly reduced the probability that a student was a

cheater in both the pre- and postdefinition equations; this may indicate risk aver-

sion by students who did not know the likelihood of capture for cheating. This

result is consistent with the fact that students in our sample generally believed

that the probability of being caught was low. That is, because most students per-

ceived a low probability of getting caught cheating, those who were uncertain

may view the probability as higher, even though they could not give an actual esti-

mate of the probability of being caught.

Our most interesting finding was that the severity of punishment variables were

significant (with the correct signs) only after a definition of cheating was given.

This indicated that students who believed that the severity of punishment for

cheating was severe or moderate or students who were uncertain about the sever-

ity of punishment were less likely to be cheaters than students who believed that

punishment for cheating was mild if students reported informed cheating

responses.12 These results are important and are generated by the apparent fact

that some of the students who answered that the severity of punishment was mild

reported that they did not cheat before the definition of cheating was given but

answered that they did cheat after the definition was provided. In two of the four

models estimated by Mixon (1996), he found the severity of punishment to affect

significantly the likelihood that students were cheaters, although other

Winter 2007 13

researchers that formally quantify severity of punishment found no significant

impact (Bunn, Caudill, and Gropper 1992; Mixon and Mixon 1996).13 Perhaps

these researchers did not find that severity of punishment affects cheating because

students who believed that the severity of punishment was mild did not believe

that certain behaviors were, in fact, cheating. Researchers in prior studies may

also have understated the magnitude with which severity of punishment affects

cheating, even when severity of punishment was significant. Using likelihood

ratio tests, we rejected the null hypothesis that the coefficients, before and after a

definition of cheating was given, for SEVPUNISH and MODPUNISH were

equal. Because these coefficients were greater in absolute value in the postdefin-

ition equation, researchers that do not provide a definition of cheating may under-

estimate the role of severity of punishment on cheating.

Finally, the UR variable, which indicated the university with the publicized

honor code, was negative and insignificant in the predefinition regression and

negative and significant in the postdefinition regression. This indicated that stu-

dents were less likely to admit to cheating at this institution (or more likely to

cheat at UNCW), particularly if students were informed about the definition of

cheating. However, keep in mind that students at both institutions reported a

higher frequency of cheating after a definition was provided. An honor code

may reduce the probability that a particular student cheats, but, for those who

cheat nonetheless, the honor code may not reduce the frequency to which they

cheat.

CONCLUSIONS

In addition to identifying factors that contribute to the probability of cheating,

two general conclusions can be drawn from the results of this study. First, regard-

ing students’ understanding of which behaviors are regarded as cheating, both

direct results from the survey and comparison of pre- and postdefinition models

suggest that student definitions of cheating are, at best, incomplete. Similar to the

randomized response survey techniques of Kerkvliet (1994), the provision of a

definition of cheating elicits an increase in self-reported cheating behavior (with-

out reducing sample size). In fact, our results indicate that any survey of students

regarding cheating behavior that does not provide a clear definition of cheating

may still contain an inherent underreporting bias; the students in our survey were

more likely to be cheaters over the past 12 months after a definition of cheating

was provided. Because students attending both schools did not fully comprehend

what cheating is, it seems that an obvious first step toward combating cheating

would be to provide clear and consistent reminders of which behaviors are unac-

ceptable. Well-publicized honor codes may achieve this objective.

Second, our findings have implications for researchers seeking to understand

the specific student factors that contribute to cheating. Researchers’ purpose in

past studies was to identify student characteristics that significantly affect

cheating behavior so that cheating could be combated more effectively. Results of

our study which replicates a set of explanatory variables previously established in

the literature, generally supports prior research. In addition, we also find that

14 JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC EDUCATION

well-publicized honor codes may reduce the number of cheaters if students report

cheating after reading a clear definition of cheating.

Our primary contribution may be associated with student perceptions of the

severity of punishment for cheating. We find that students in our sample who

believe that the severity of punishment for cheating is relatively high are less

likely to cheat if cheating is defined when students report cheating behavior. We

also find that the magnitude with which cheating is reduced by increased percep-

tions of the severity of punishment is increased when students provide cheating

data after a definition of cheating is given.

Our results imply an area that is rich for further study. The analysis used here

should be extended to further investigate causes of the discrepancy between fac-

ulty-student and student-student definitions of cheating. There may be a set of

student characteristics that contribute to misinformation about acceptable aca-

demic behavior which are identifiable. Perhaps more important, if publicizing

formal definitions of acceptable and unacceptable academic behaviors lead to

reduced cheating incidences across all types of students, educators are faced with

the question of how to best accomplish that task.

NOTES

1. See Baird (1980); Gardner, Roper, and Gonzalez (1988); Bunn, Caudill, and Gropper (1992);Kerkvliet (1994); Genereux and McLeod (1995); McCabe and Bowers (1996); McCabe andTrevino (1997); and Kerkvliet and Sigmund (1999).

2. See Bunn, Caudill, and Gropper (1992); Genereux and McLeod (1995); McCabe and Bowers(1996); Mixon and Mixon (1996); Mixon (1996); McCabe and Trevino (1997); Whitley (1998);and Magnus et al. (2002).

3. A copy of the survey is available from the authors upon request.4. We removed four completed surveys because responses to frequency of cheating questions were

so large as to be obviously fictitious. 5. For more information on bivariate probit estimation, see Greene (2003). 6. Notable exceptions included studies by Kerkvliet (1994) and Nowell and Laufer (1997), the

results of which suggested that GPA did not significantly affect cheating.7. For the bivariate probit model, marginal effects for the continuous variables in the predefinition

equation are equal to the relevant partial derivatives of E[y1|y2 � 1] where y1 is the predefini-tion cheating response, and y2 is the postdefinition response and marginal effects for the dummyvariables are given by E[y1|y2 � 1, d � 1] � E[y1|y2 � 1, d � 0] where d is the dummy vari-able. For the postdefinition equation, marginal effects for GPA and ALCOHOL are the corre-sponding partial derivatives of E[y2|y1 � 1] and marginal effects for the dummy variables areE[y2|y1 � 1, d � 1] � E[y2|y1 � 1, d � 0].

8. Using the likelihood ratio test, the null hypothesis that all the parameters are zero was rejected aswas the null hypothesis that all the parameter values are equivalent.

9. We did not reject the null hypothesis that the magnitudes of the individual parameter estimatesfor these variables are equal in the pre- and postdefinition equations, except in the case of uni-versity athletes.

10. Again, we did not reject the null hypothesis that the magnitudes of the individual parameter esti-mates for these variables are equal in the pre- and postdefinition equations.

11. The coefficient estimates for witnessing a cheater being captured were positive but insignificantin Mixon and Mixon (1996) and Bunn, Caudill, and Gropper (1992). Mixon (1996), however,found that observing a capture significantly increases the probability that a student is a cheater.

12. The importance of these results is reinforced by the marginal effects that show that students whobelieved that the punishment for cheating was severe or moderate and students who did not knowthe severity of punishment were 21 percent, 30 percent, and 28 percent less likely to cheat, respec-tively, than students who thought that the severity of punishment for cheating was mild.

13. Mixon (1996) found that students who believed that the punishment for cheating was a one-lettergrade reduction and students who believed that punishment was a reprimand only were more

Winter 2007 15

likely to cheat than were students who believed that the punishment for cheating was suspensionfrom the university. These results were obtained in a model that did not include perceptions thatother students cheat and in a model that did not include both perceptions that other students cheatand GPA, respectively.

REFERENCES

Baird, J. S., Jr. 1980. Current trends in college cheating. Psychology in the Schools 17 (4): 515–22.Barnett, D. C., and J. C. Dalton. 1981. Why college students cheat. Journal of College Student

Personnel 22 (6): 545–51.Becker, G. 1968. Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy 76 (2):

168–217.Bunn, D. N., S. B. Caudill, and D. M. Gropper. 1992. Crime in the classroom: An economic analysis of

undergraduate student cheating behavior. Journal of Economic Education 23 (Summer): 197–207. Franklyn-Stokes, A., and S. E. Newstead. 1995. Undergraduate cheating: Who does what why?

Studies in Higher Education 20 (2):159–72.Gardner, W. M., T. Roper, and C. C. Gonzalez. 1988. Analysis of cheating on academic assignments.

Psychological Record 38 (Fall): 543–55.Genereux, R. L., and B. A. McLeod. 1995. Circumstances surrounding cheating: A questionnaire

study of college students. Research in Higher Education 36 (6): 687–704.Graham, M. A., J. Monday, K. O’Brien, and S. Steffen. 1994. Cheating at small colleges: An exami-

nation of student and faculty attitudes and behaviors. Journal of College Student Development 35(4): 255–60.

Greene, W. H. 2003. Econometric Analysis. 5th ed. New York: Macmillian.Hollinger, R. C., and L. Lanza-Kaduce. 1996. Academic dishonesty and the perceived effectiveness

of countermeasures: An empirical survey of cheating at a major public university. NASPA Journal33 (4): 292–306.

Houston, J. P. 1986. Classroom answer copying: Roles of acquaintanceship and free versus assignedseating. Journal of Educational Psychology 78 (June): 230–32.

Kerkvliet, J. 1994. Cheating by economics students: A comparison of survey results. Journal ofEconomic Education 27 (2): 121–33.

Kerkvliet, J., and C. L. Sigmund. 1999. Can we control cheating in the classroom? Journal of EconomicEducation, 30 (4): 195–200.

Magnus, J. R., V. M. Polterovich, D. L. Danilov, and A. V. Savvateev. 2002. Tolerance of cheating: Ananalysis across countries. Journal of Economic Education 33 (2): 125–35.

Meade, J. 1992. Cheating: Is academic dishonesty par for the course? Prism 1 (7): 30–32.McCabe, D. L., and W. J. Bowers. 1996. The relationship between student cheating and college fra-

ternity or sorority membership. NASPA Journal 33 (4): 280–91.McCabe, D. L., and L. K. Trevino. 1993. Academic dishonesty: Honor codes and other contextual

influences. Journal of Higher Education 64 (5): 522–38.———. 1997. Individual and contextual influences on academic dishonesty: A multicampus investi-

gation. Research in Higher Education 38 (3): 379–96.Mixon, F. G. Jr. 1996. Crime in the classroom: An extension. Journal of Economic Education 27 (3):

195–200.Mixon, F. G., Jr., and D. C. Mixon. 1996. The economics of illegitimate activities: Further evidence.

Journal of Socio-Economics 25 (3): 373–81.Nowell, C., and D. Laufer. 1997. Undergraduate student cheating in the fields of business and eco-

nomics. Journal of Economic Education 28 (1): 3–11.Singhal, A. C. 1982. Factors in students’ dishonesty. Psychological Reports 51(December): 775–80.Stern, E., and L. Havlicek. 1986. Academic misconduct: Results of faculty and undergraduate student

surveys. Journal of Allied Health 5 (2): 129–42.Stevens, G., and F. Stevens. 1987. Ethical inclinations of tomorrow’s managers revisited: How and

why students cheat. Journal of Education for Business 63 (1): 24–29.Whitley, B. E. Jr. 1998. Factors associated with cheating among college students: A review. Research

in Higher Education 39 (3): 235–74.Wright, J. C., and R. Kelly. 1974. Cheating: Student/faculty views and responsibilities. Improving

College and University Teaching 22 (1): 31.

16 JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC EDUCATION