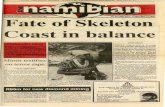

TOPOGRAPHIES OF TERROR - READING REMNANTS AND TRACES ON THE GESTAPO GELÄNDE

Robespierre and the Terror

Transcript of Robespierre and the Terror

AUGUST 2006 HISTORY TODAY

AXIMILIEN ROBESPIERRE hasalways provoked strong feel-ings. For the English he is the

‘sea-green incorruptible’ portrayed byCarlyle, the repellent figure at thehead of the Revolution, who sentthousands of people to their deathunder the guillotine. The French, forthe most part, dislike his memory stillmore. There is no national monu-ment to him, though many of the rev-olutionaries have had statues raised tothem. Robespierre is still consideredbeyond the pale; only one rathershabby metro station in a poorer sub-urb of Paris bears his name.

Although Robespierre, like mostof the revolutionaries, was a bour-geois, he identified with the cause ofthe urban workers, the sans-culottes asthey came to be known, and became

a spokesman for them. It is for thisreason that he came to dominate theRevolution in its most radical phase.This was the period of the Jacobingovernment, which lasted from June1793 to Robespierre’s overthrow inJuly 1794; the months when the com-mon people became briefly the mas-ters of the first French republic,which had been proclaimed inSeptember 1792. It is also known,more ominously, as the Terror.

The enigmatic figure of Robe-spierre takes us to the heart of the

Revolution,and throws light both on its ideals,and on the violence that indeliblyscarred it.

Born in Arras in 1758, Robe-spierre suffered loss early in his life.His mother died when he was six,and soon after, his father abandonedthe family. The children werebrought up by elderly relatives whocontinually reminded them of theirdependent situation and theirfather’s irresponsibility. Maximilienwas the eldest, a conscientious, hard-working scholarship boy. As soon ashe was able he shouldered the bur-

23

Marisa Linton reviews the life and career of one of the mostvilified men in history.

‘That young man believes what hesays: he will go far,’ Mirabeau. Portraitof Robespierre by Joseph Boze.

‘Hell Broke Loose’: an English commenton the execution of Louis XVI, 1793.

ROBESPIERREAND THE TERROR

M

ROBESPIERRE AND THE TERROR

HISTORY TODAY AUGUST 2006

den of caring for his younger sib-lings. He became a lawyer, leading aquiet and blameless life in his nativetown. He was best known for defend-ing the poor, and for some ratherlengthy and tedious speeches at thelocal academy.

In 1789, when he was in his earlythirties, the Revolution transformedhis destiny. He launched himself intothe political maelstrom that wouldimmerse him for the rest of his life.He was elected as a deputy for theThird Estate in the Estates Generalin May, and he witnessed the onsetof the Revolution that broke thepower of the absolute monarchy twomonths later. Painstakingly, heworked to forge a reputation forhimself as a public speaker in theAssembly. He had his power-base inthe Jacobin Club, the most impor-tant of the revolutionary clubs wherepeople debated events.

From the first, Robespierre was aradical and a democrat, defendingthe principle that the ‘rights of man’should extend to all men – includingthe poor, and the slaves in thecolonies. This stance won him a rep-utation among the sans-culottes andthe radical left, but the earlier yearsof the Revolution were dominated bymen who had no wish to see powerin the hands of the propertyless.Robespierre was undaunted. As aspokesman for the opposition and

critic of government, he was tirelessand consistent. He was also for along time a vehement opponent ofthe death penalty. Why did he laterchange his mind and become anadvocate of Terror? Part of theanswer to this question lies in thedeterioration of the political situa-tion between 1789 and 1792, and thefailure of the attempt to set up aworkable constitutional monarchy,under Louis XVI.

From the spring of 1792 onwardsFrance was involved in a spiral ofwar, revolt and civil war. Counter-revolutionaries were plotting therestoration of the absolute monarchywith the support of the Holy RomanEmperor Leopold II (succeeded inMarch by Francis II). The Girondins,then the dominant revolutionary fac-tion in the Legislative Assembly,

spearheaded the drive for an aggres-sive war with the Empire, declaringwar in April 1792. The avowed inten-tion of their leader, Jacques-PierreBrissot, was to polarize French poli-tics, oblige the counter-revolutionar-ies to emerge into open opposition,and force the monarchy either tocapitulate to the revolutionaries orto face its own destruction. In thesecircumstances, political views hard-ened, suspicion and fear increased,and the early optimism of the Revo-lution vanished.

Robespierre himself had longwarned of the dangers of provokingcounter-revolution. He had tried tooppose the war, because he thoughtit would divide France and rally sup-port for the counter-revolutionaries.Nor did he believe, as Brissot did,that the ordinary people of Europewould welcome an invading Frencharmy, even one that claimed to deliv-er liberty and equality. ‘No one,’ saidRobespierre, ‘welcomes armed liber-ators.’ He stuck doggedly to thisposition, though it was deeplyunpopular and he became politicallyisolated.

By the summer of 1792, his worstfears were realized. The Frencharmy, far from being victorious, wason the verge of defeat and sufferedfrom disorganization and raw andinexperienced troops. Many peoplethought (not without reason) thatLouis was secretly on the side of theAustrian and Prussian armies, whichwere now threatening Paris itself.Many people now felt that Robe-

24

The storming of the Bastille, July 14th,1789.

The citizens of Paris give their jewelsto the National Assembly, September1789; painting by the Le Sueurbrothers c. 1795.

AUGUST 2006 HISTORY TODAY

spierre spoke for them when hedeclared that the aristocrats wereplotting a conspiracy to destroy theRevolution. In August the monarchywas overthrown in a pitched battle atthe Tuileries palace. A new govern-ment, the National Convention, wasformed in September 1792, whichpromptly declared France to be arepublic. By now Robespierre’sascendancy in the Jacobin club wasunrivalled. The Jacobins identifiedthemselves with the popular move-ment and the sans-culottes, who inturn saw popular violence as a politi-cal right.

The most notorious instance ofthe crowd’s rough justice was theprison massacres of September 1792,when around 2,000 people, includ-ing priests and nuns, were draggedfrom their prison cells, and subject-ed to summary ‘justice’. The Con-vention was determined to avoid arepeat of these brutal scenes, butthat meant taking violence into theirown hands as an instrument of gov-ernment.

When the Convention debatedthe fate of Louis XVI, now a prisonerof the revolutionaries,Robespierre and hisyouthful colleague,Saint-Just (1767-94) – also oncean opponentof the deathpenalty –led the wayin claim-ing that‘ L o u i smust die inorder forthe Revolu-tion to live’.Robespierre hadnot abandoned hislibertarian convic-tions, but he was coming tothe conclusion that the ends justifiedthe means, and that in order todefend the Revolution against thosewho would destroy it, the sheddingof blood was justified.

In June 1793, the sans-culottes,exasperated by the inadequacies ofthe government, invaded the Con-vention and overthrew the Giron-dins. In their place they endorsedthe political ascendancy of theJacobins. Thus Robespierre came topower on the back of popular streetviolence. Though the Girondins and

the Jacobins were both on theextreme left, and shared many of thesame radical republican convictionsof the Girondins, the Jacobins weremuch more brutally efficient in set-ting up a war government. A Com-mittee of Public Safety was estab-lished to act as a war cabinet. Itbecame the chief executive power,with Robespierre – now moving fromopposition to government for thefirst time – one of its twelve mem-bers. Like so many politicians mak-ing such a move, Robespierre’s atti-tude to political power was to changedramatically from this moment. InJune the Jacobins drafted a new con-stitution, the most libertarian and

egalitarian the world hadyet seen. Yet for some

months they hesitated to imple-ment it, as the pressures of war withAustria and Prussia, and of full-blown civil war in the Vendée in thewest were compounded by revoltsacross the country by départementsrejecting the authority of the radicalgovernment in Paris.

In September 1793, impatient, thesans-culottes, once again invaded theConvention to exert pressure on thedeputies. They wanted economicmeasures to ensure their food sup-plies, and the government to dealwith counter-revolutionaries. A dele-

gation of the forty-eight sections ofsans-culottes urged the Convention to‘make Terror the order of the day!’The Jacobins responded: the Law ofSuspects was passed on September17th, 1793, giving wide powers ofarrest to the ruling Committees, anddefining ‘suspects’ in broad terms.In October the Convention passedthe Decree on Emergency Govern-ment. This authorized the revolu-tionary government to pass beyondaccepted limits. Saint-Just decreedthat the government ‘would be revo-lutionary until the peace’. The con-stitution was shelved: the libertarianideals of the Revolution were sus-pended, indefinitely. Sans-culottes

formed armed militias to go out intothe provinces to requisition suppliesfor the armies and the urban popu-lace and to root out counter-revolu-tionaries. In October Brissot andother Girondin leaders, as well asMarie-Antoinette went to the guillo-tine.

For the first time in history terrorbecame an official government poli-cy, with the stated aim to use vio-lence in order to achieve a higherpolitical goal. Unlike the later mean-ing of ‘terrorists’ as people who useviolence against a government, theterrorists of the French Revolutionwere the government. The Terror waslegal, having been voted for by theConvention.

Robespierre, like a number of theJacobin government, had been alawyer. He clung to the form of lawpartly in order to prevent the sans-culottes taking the law into their ownhands through mob violence. As fel-

25

ROBESPIERRE AND THE TERROR

‘Live free or die’: aRevolutionaryplate of 1792 (left),and, above a

cartoon of ‘TheRevolution Failed’,

1792.

ROBESPIERRE AND THE TERROR

HISTORY TODAY AUGUST 2006

low revolutionary Danton said, ‘let usbe terrible in order to stop the peo-ple from being so’. The resort to Ter-ror also emerged out of relativeweakness and fear. The Jacobins hadonly a shaky legitimacy and innumer-able opponents throughout France,ranging from intransigent royalists tomore moderate revolutionaries whohad seen power centralized and theirideas superseded. Many people inFrance were already indifferent, ifnot openly hostile, to the Revolution.For many the Revolution now meantrequisitioning of supplies, militaryconscription and the constant threatto their traditional ways of life,churches, even time – for the revolu-tionaries had even invented a newcalendar. Throughout the year ofJacobin rule, it was the sans-culotteswho kept them in power. But theprice of that support was the blood-letting.

The number of death sentences inParis was 2,639, while the total num-ber during the Terror in the wholeof France (including Paris) was16,594. With the exception of Paris(where many of the more importantprisoners were transferred to appearbefore the Revolutionary Tribunal)most of the executions were carriedout in regions of revolt such as theVendée, Lyon and Marseilles. Therewere wide regional variations.Because on the whole the Jacobinswere meticulous in maintaining alegal structure for the Terror clearrecords exist for official death sen-tences. But many more people weremurdered without formal sentences

imposed in a court of law. Some diedin overcrowded and unsanitary pris-ons awaiting trial, while others diedin the civil wars and federalistrevolts, their deaths unrecorded.The historian Jean-Clément Martin,suggests that up to 250,000 insur-gents and 200,000 republicans mettheir deaths in the Vendée, a warwhich lasted from 1793-96 in whichboth sides suffered appalling atroci-ties.

Today the civil war in the Vendéeis largely forgotten except by special-ists. It is of the guillotine that mostpeople think when they hear aboutthe Terror. After so many bloodlet-tings of the twentieth century, whydoes that image still have the powerto shock us? The historianLord Acton once famous-ly said that in terms ofthe time, the deathsunder the Terrorwere relatively fewin number (hewas thinking ofthe officialdeath sen-tences). AsActon pointedout, many mil-lions were todie inN a p o l e o n ’ swars for no bet-ter reason thanhis own glory. Yetthe aura of the herostill clings toNapoleon, while Robe-spierre’s name is synony-

mous with violence and horror. Perhaps it is because of the stark

contrast between Robespierre’s ide-als and what he became that thequestion of the Terror remainsshocking. In the mind of Robe-spierre and many of his colleagues,the Terror had a deeper moral pur-pose beyond winning the civil war: tobring about a ‘republic of virtue’. Bythis he meant a society in which peo-ple sought the happiness of their fel-low humans rather than their ownmaterial benefit. France must beregenerated on moral lines. ‘What isour aim?’ he asked in a speech ofFebruary 1794.

The peaceful enjoyment of libertyand equality; the reign of that eternaljustice whose laws are written, not onmarble or stone, but in the hearts ofall men, even in that of the slave whoforgets them and of the tyrant whodenies them.

He came to the conclusion that inorder to establish this ideal republicone had to be prepared to eliminateopponents of the Revolution. Theirony of this idea rings through inthe same speech, when he justifiedthe Terror. He said:

If the basis of popular government inpeacetime is virtue, the basis ofpopular government during arevolution is both virtue and terror;

virtue, without which terror isbaneful; terror, without which

virtue is powerless. Terroris nothing more than

speedy, severe andinflexible justice; it isthus an emanationof virtue; it is less aprinciple in itself,than aconsequence ofthe generalprinciple ofdemocracy,applied to themost pressing

needs of the patrie.

26

An aristocrat denounced before aRevolutionary Committee.

Louis de Saint-Just(1767-94), associate of

Robespierre on theCommittee of Public Safety.

AUGUST 2006 HISTORY TODAY

Throughout his time in govern-ment Robespierre conducted his pri-vate life as a man of virtue. Far fromliving in palaces, amassing treasure,or allying himself with royalty, asNapoleon was to do, Robespierrelived a celebate life as a lodger, occu-pying simple rooms in the house of amaster carpenter. He was known as‘the Incorruptible’ for, unlike manypoliticians, he refused to use a publicposition for private gain and self-advancement. He lived simply on hisdeputy’s salary. He walked every-where, never taking a carriage. Heenjoyed walks in the country andmusical soirées with his landlord’sfamily.

Yet the other side of this benign, ifdull, domestic life, was the public

role he undertook as a spokesmanfor the Committee of Public Safetyand the guiding hand on the policyof Terror. He had become an astutepolitical tactician, and he used thesemeans to finally achieve politicalpower. He could be accused, justly,of political ambition, but he himselfdid not see this as inconsistent withhis dedication to the Revolution. Hehad an unshakable belief that hisown aims coincided with what wasbest for the Revolution. He was aman of painful sincerity. He was nota hypocrite. He really did believethat the Terror could sustain therepublic of virtue. But he was natu-rally self-righteous, suspicious and

unforgiving. All these quali-ties came to the fore as itbecame evident that whilethe Terror played a keypart in winning the warand quelling the counter-revolution, it was having thereverse effect as far asinstalling the republic of virtuewas concerned, undermining anygenuine enthusiasm for the Revolu-tion. Even Saint-Just, Robespierre’smost loyal friend on the Committeeof Public Safety, could not be blindto the way the Terror, with its neigh-bourhood surveillance committeesand denunciations, encouraged anatmosphere of duplicity, cynicismand fear, even among the Revolu-tion’s most fervent supporters, theJacobins. ‘The Revolution is frozen’,he wrote dispairingly in a privatenote in 1794.

Some of the victims of the lastmonths of the Terror were Robe-spierre’s former friends and col-leagues, stalwarts of the JacobinClub. They included CamilleDesmoulins, Robespierre’s comradefrom his schooldays. Desmoulins hadtaken the fateful step of supportingGeorges Danton, another formerfriend of Robespierre, in his call thatthe Terror be wound down, and the

power of the Committee of PublicSafety broken. In December 1793 helaunched a journal, Le Vieux Cordelier,arguing that the Revolution shouldreturn to its original ideals. Up to apoint Robespierre had supportedDesmoulins and his campaignagainst the more violent extremismof the sans-culottes, led by the journal-ist, Hébert. Robespierre read, andapproved, the first two issues of LeVieux Cordelier in proof. But in thethird issue of the journal,Desmoulins parodied the notoriousLaw of Suspects and its wide range ofpeople who could be considered‘counter-revolutionary’. Under the

27

‘Something for crowned jokers to thinkabout: how impure blood can enrichour furrows’. From a graphic of 1793which included a quotation from LaMarseillaise, the French anthem.

Les tricoteuses of Year II, kntting by theguillotine; and (right) a Frenchcaricature of ‘Robespierre and theJacobins’ Purifying Pan’.

ROBESPIERRE AND THE TERROR

HISTORY TODAY AUGUST 2006

Roman Empire, he said, paraphras-ing Tacitus, people could be con-demned as counter-revolutionary forbeing ‘too rich… or too poor… toomelancholy... or too self-indulgent’.Robespierre saw this satire – rightly –as a veiled attack on the Committeeof Public Safety itself. Robespierretried to persuade Desmoulins toburn the journal publicly in theJacobin Club. Desmoulins refused,recklessly citing the words of Robe-spierre’s hero, Jean-JacquesRousseau, against him, ‘burning isnot an answer’. Robespierre wasstung, and stopped trying to help hisfriend. When the Committees decid-ed to arrest Danton and Desmoulinsin March 1794, Robespierre used hispersonal knowledge of the two mento supplement his notes for the offi-cial indictment against them.Desmoulins’ wife, Lucille, tried toagitate for his release but she too wasaccused of conspiracy against theRevolution and followed her hus-band to the guillotine in April. Theletter from her heart-broken motherto Robespierre, begging for his inter-vention to save her daughter, wentunanswered. Robespierre had said

that a man of virtue must put thegood of la patrie before private loyal-ty, even to his friends. Never had hisown virtue seemed so appalling andinhuman as at that moment.

Perhaps he thought so too, andthe strain of what he had becomewas beginning to tell. In the last fewweeks of his life he shut himself inhis rooms, and did not attend themeetings of the Committee or theConvention. He was losing his grip,both on himself and on power. In hisabsence it is notable that it was ‘busi-ness as usual’ for the Terror: in Paristhe executions intensified, based onthe notorious Law of 22nd Prairial

(June 10th 1794) which, by depriv-ing the accused of counsel andremoving the need for witnesses tosubstantiate accusations, removedthe vestige of justice from the Tri-bunal.

Robespierre was never the head ofthe government, nor the only terror-ist: he was one man on the Commit-tee – albeit its most high-profilemember. Other members of theCommittee, together with membersof the Committee of General Securi-ty (responsible for the police, pris-ons and most of the arrests), were asmuch responsible for the running ofthe Terror as Robespierre. Some ofhis colleagues were hard, ambitiousmen, not averse to political corrup-tion unlike Robespierre, and scorn-ful of his dream of a virtuous repub-lic. There were aspects of the Terrorwith which Robespierre disagreed.He was an opponent of dechristian-ization – a policy carried out by somemilitant sans-culottes of forcibly clos-ing churches and preventing anykind of religious activity. In June1794 he organized the festival of theSupreme Being, based on Enlighten-ment deist beliefs, intended to unify

28

The festival of the Supreme Being heldat Robespierre’s instigation on June 8th,1794.

Georges Danton on the way to hisexecution, April 5th, 1794. Sketch byPierre Wille.

AUGUST 2006 HISTORY TODAY

the people around broadly moraland vaguely religious principles. Itmade him a laughing stock with theatheists among the deputies andfailed to conciliate devout Catholics,long since alienated from the Revo-lution by its anti-clericalism.

Robespierre also deplored the vio-lent excesses of some of the Jacobindeputies sent out ‘on mission’ fromthe Convention to oversee the imple-mentation of policy in the provincesand with the armies. While many ofthe deputies on mission were consci-entious and restrained, others mis-used their powers to arrest, intimi-date and execute local populations.Robespierre had some of thesedeputies, including Tallien, Fouché,Fréron, Barras and Collot d’Herbois,in his sights when he went to theConvention for the first time inmore than four weeks on the July26th (8 Thermidor by the revolution-ary calendar). It was the turningpoint. He had already quarrelledwith men on both the ruling Com-mittees, and, having rejected the rec-onciliation which Saint-Just tried tobroker, he was left with little alterna-tive but to try to destroy his enemiesbefore they could do the same tohim. He made a long speech inwhich he sought to justify the standhe had taken as a defender of virtue.But he also took the opportunity todemand another purge of suspectdeputies. In a fatal miscalculation,he failed to name these men. Notunnaturally, many of the fearfuldeputies thought he might meanthem. ‘The names!’ they shouted.

But he refused. His enemies amongthe Jacobins spent that night in orga-nizing their conspiracy. The next daySaint-Just was shouted down when hetried to speak in his friend’s defence.Robespierre and his closest associ-ates were arrested and, after a futileattempt to rally the sans-culottes todefend them at the town hall, theywere executed the following day.

The men who overthrew Robe-spierre were more ruthless and cyni-cal terrorists than he. They includedVadier, Elie Lacoste, Billaud-Varenneand Collot d’Herbois on the Com-mittees, as well as the deputies whohad carried out atrocities whilst ‘onmission’. Initially they wanted theTerror to continue. But it rapidlybecame clear that the public hadsickened of it. Since the overwhelm-ing victory over the Austrians in theLow Countries at Fleurus on June26th, the military justification for ithad also diminished. In the reactionafter Thermidor, as the coup isknown, terrorist politicians rapidlyrestyled themselves. Members of theCommittees now claimed that theyhad concerned themselves exclusive-ly with the war: it was only the Robe-spierrists who had been terrorists. Inthe popular imagination Robe-spierre the enigma rapidly becamethe embodiment of the Terror. Yethe would never have been so influen-tial had he not spoken for a wideswathe of society and government.

When he spoke of conspiraciesagainst the Revolution, of the threatsto ‘the patrie in danger’, and theneed for extreme measures, hevoiced the fears of many at that timethat France was about to be over-whelmed by foreign and internalenemies. The policies of the JacobinCommittees had, after all, beenendorsed by the deputies of the Con-vention. Perhaps this is why he hasbeen so vilified: in holding one indi-vidual culpable for the ills of the Ter-ror, French society was able to avoidlooking into its own dark heart atthat traumatic moment. Robespierre,you might say, took the rap.

FFOORR FFUURRTTHHEERR RREEAADDIINNGGJ. M.Thompson, Robespierre (Blackwell, 1988);Norman Hampson, The Life and Opinions ofMaximilien Robespierre (Duckworth, 1974);William Doyle and Colin Haydon (eds),Robespierre (Cambridge University Press, 1999)John Hardman, Robespierre (Pearson Education,1999); Ruth Scurr, Fatal Purity: Robespierre and theFrench Revolution (Chatto and Windus, 2006);David P. Jordan, The Revolutionary Career ofMaximilien Robespierre (The Free Press, 1985);David Andress, The Terror: Civil War in the FrenchRevolution (Little, Brown, 2005); R.R. Palmer,Twelve Who Ruled: the Year of the Terror in the FrenchRevolution (Princeton University Press, 1969).See page 57 for related articles on this subject inthe History Today archive and details of specialoffers at www.historytoday.com

MMaarriissaa LLiinnttoonn iiss SSeenniioorr LLeeccttuurreerr iinn HHiissttoorryy aattKKiinnggssttoonn UUnniivveerrssiittyy aanndd tthhee aauutthhoorr ooff TThhee PPoolliittiiccssooff VViirrttuuee iinn EEnnlliigghhtteennmmeenntt FFrraannccee ((PPaallggrraavvee,, 22000011))..

29

TITLE

‘Having executed everyone else,Robespierre executes the executioner’:satirical print of 1794.

The arrest of Robespierre, 9-10thThermidor, Year II (July 27th, 1794).Jean-Jacques Tassaert.