Orthodox Christianity and Gender : Dynamics of Tradition ...

Right Singing in Estonian Orthodox Christianity: A Study of Music, Theology, and Religious Ideology

Transcript of Right Singing in Estonian Orthodox Christianity: A Study of Music, Theology, and Religious Ideology

)lOgy, Inc.e the advancement of research and)se all interested persons, regardlesso become members. Its aims includehe dissemination of knowledge conIcorporated in the United States, has

ept. of Music, University of California,L, Vice-Principal Academic and Dean,.N.,3125 SB,Mississauga,ONL5L 1C5IRANcO, Universidade Nova de Usboa,erna 26C, 1069-061 Lisbon, Portugal;jt of Music, University ofWashington,•f Music, University of Arizona, 1017FLANDREAU, Center for Black Musicgo, II 60605; Members-at-Large: TONG4 N. Decatur Rd., Atlanta GA 30322-olytechnic Institute, 110 8th St,Troy

UM, PAUL AUSTERLITZ, VICKI BRENNAN,IA GRAHAM, JEAN KIDULA, DONNA LEE*.NG, JESSE SAMBA WHEELER. Term end-‘EVELYN, SHANNON DUDLEY, KENNETHRCUS, REBEcCA MILLER, DAVID SANJEK,UM, SIU-WAH Yu. Term ending 2011:AGEDORN, MONICA HAIRSTON, JUNIPERNA K. RAMNARINE, HIR0MI LORRAINEHILLIP YAMPOLSKY.

the Society for Etlmomusicology, is a‘ersity of Illinois Press, 1325 SOak St.,I publishes original articles in the fieldiously published articles are generallye Society.The views expressed are theIfficers. Articles and communicationslooks and recordings for review andappropriate editor or bibliographer.EM Newstette, which functions as aReaders’ contributions are welcomednries pertaining to advertising in therslcner; for advertising in the journal,Illinois Press.OLEY, Dept. of Music, University [email protected]); Incoming

I Clarice Smith Center, University of)[email protected]); Book Review Edi)rbett Rd., Cardiff University, Cardiffik); Recording Review Editor: PAULy Mill Rd., Media, PA 19063 (pdg4@REBECCA S. MILLER, Music Program,002 ([email protected]); Curlanchester, MI 48159 (rbaier@emichouthern Dr., Bloomington, IN 47401HENDERSON, Music Dept., St. Lawrences and Dissertations: JENNIFER C. POST,[email protected]; SEM Newsletter Editor:uclds Ave., Davis, CA 95616 (hjspiller@son Hall 005, Indiana University, 1165na.edu).EMPFLE ([email protected]) andlorrison Hall 005, Indiana University,(812) 855-6672.

ETHNOMU$ICOLOGVJournal of the Society for Fthnomusicology

Vol. 53, No. 1 Winter 2009

Editor: TimothyJ. CooleyIncoming Editor: J. Lawrence WitzlebenAssistant Editor: Barbara I. Taylor

Book Review Editon John Morgan O’ConnellRecording Review Editon Paul Greene

film, Video, and Multimedia Reviews: Rebecca S. MiflerEditorial Board: Stephen Blum

Naila Ceribasic Beverly DiamondVeit Erlmann Michael frishkopfTravisA.Jackson Helen ReesTimothy Rice Ricardo D.Trimillos

CONTENTSfrom the Editor

Notes on Contributing Authors

Articles

1 What Do Ethnomusicologists Do? An Old Question for aNew Century ADEIAIDA REYES

18 Ethnomusicology and theTwenty-First Century Music Scene Bni Ivev

32 Right Singing in Estonian Orthodox Christianity: A Study ofMusic, Theology, and Religious Ideology JEFFERS ENGELHARDT

58 Poetics and the Performance ofViolence in Israel/PalestineDAVID A. MCDONALD

86 Rebellious Pedagogy Ideological Transformation, and CreativeFreedom in Finnish Contemporary Folk Music JUNiPER HWL

115 RadicalTradition: Balinese Musik Kontemporer ANDIthw MCGRAw

Book Reviews

142 Theodore Levin, Where Rivers and Mountains Sing:Sound, Music, and Nomadism in Tuva and Beyond RACHEL HARRIS

144 Tejaswini Niranjana,Mobilizing India: Women, Music,andMigration between India and Trinidad PUrER MAMJEL

146 William H. Chapman Nyaho, ed., Piano Music ofAfrica and theAfrican Diaspora, Vol. 1; Piano Music ofAfrica and the AfricanDiaspora, Vol.2; Piano Music ofAfrica and theAfrican Diaspora,Vol.3 CAROLINE RAE

omusicology

ii ftbnomusicotogy, Winter 2009

152 Mi Jthad Racy, Music Making in the Arab World.’The Culture andArtistiy ofTarab

156 frederick Lau, Music in China: Experiencing Music,Expressing Culture

ANNE K. RASMUSSEN

JONATHAN P. J. STOCK

Information fMANUSCRIPT SUBMISSION

Note: Article manuscripts shoben, School ofMusic, 2110 CMD 20742-1620.1. Submit three copies of al

and an abstract of no moistandard size paper. Authmaterial under copyrightis first sent to the editor.harmless against copyng

2. Manuscripts must be typreferences cited, indenteline or one and a half liiwith only the left-hand n

3. Do not submit originalsubmit copies. Originalwhich case it must be of

4. All tables and figures, mifiustrative material shouwith notations made as Iin the body of the text a

5. References cited are caredouble-spaced on a sepaiauthor. fig. 16.2, p. 648,of Chicago Press, 1993)

6. Acknowledgments are toof the text, preceding ento give their email addrn

7. Manuscripts submittednor should they shnultarjjournal or in a book. Fu:based on material closel)the author should expla

8. Manuscripts must be in Iand punctuation. This jcthe editors thus requesiguidelines developed b3Society for Ethnomusicc

9. Book, record, and film nfrom whom authors wi]body of the review and Iously on hard copy and

10. In order to preserve ancheaders or footers that iielectronically as e-mail a

Recording Reviews159 Bissa du Burkina faso: Musique vocate et instrumentate;

Choeurs royaux du Benin: Fon-Gbe dAbomey;Mossi duBurkina faso: Musiques de coeur et de village; Yoruba du Benin:Sakara & Gelede;Asante Kete Drumming.’ Music of Ghana;Niger.’ Musique des Touaregs, vol. 1.’ Azawagh JAatES Buars

166 Sidi Goma: Live In India!; D’Bhuyaa Saaj’ Live in India!;The Rivers ofBabylon: Live in India! ALISON ARNOLD

171 Man Lomax, Gaticia;Aragon y Valencia;Extremadura;Basque Country. Biscay and Gulpüzcoa;Basque Country: Navarre JEsUs A. RAasos-ICirritaa

176 Black Mirror.’ Reflections in Global Musics Jeaissv WAU.AcH

film, Video, and Multimedia Reviews179 The Singing Revolution JEFFERS ENGELHARDT

181 From Mambo to Hi Hop: A Bronx Tale JuAN Fcoars

The current bibliography, discography, filmography and videography, and dissertationsand theses, compiled by Randall Baier, Ronda L. Sewa]d, David Henderson, and Jennifer C. Post, respectively, are located in the Publications area of the SEM website athttp://wwwethnomusicology.org.The current bibliography, discography, filmographyand videography, and dissertations and theses, compiled by Randall Baler, Karen Peters,David Henderson, and Jemer Post, respectively, are located in the Publications areaof the SEM website at http://www.ethnomusicology.org.

Right Singing in Estonian OrthodoxChristianity: A Study ofMusic, Theology,and Religious Ideology

JEFFERS ENGELHARDT / Amherst College

S cholars interested in religious musics (e.g., al Faruqi 1983; Beck 2006;Sullivan 1997), sonic theologies (Beck 1993), and the efficacy of sacred

sounds (e.g., Becker 2004) often describe how musical practices are “right” inthe context of ritual and ceremony or in terms of aesthetic ideals and religiousideologies. Right sounds happen at the “right time,” in the “right place,” andin the “right company” (Lewisohn 1997). They are performed “in the rightsequence and with the right intonation” (Slawek 1988:83), and the right kindof “religious sounding” (Greene andWei 2004:1) both creates and expresses atrue reality (e.g., Chen 2001). There are a wealth of ethnographies that showhow knowing about the propriety of sounds (e.g., Nasr 1997; Nelson [1985]2001; Shiloah 1995; Summit 2000) and how “to engage correctly the divinepotential of the ceremony” (Hagedorn 2001:76) is tantamount to knowingabout the right way of being in the world and relating to God, deities, spirits,or ancestors.With the right sounds, one can be in cornmtmion with, channelpower and seek intervention from, or be a surrogate for the divine “simplyby getting the symbolism right” (Mabbett 1993-94:19). The wrong sounds,however, can defile religious doctrine, alienate humanity from itself and thedivine, and violate moral order (e.g., Mazo 2006:94; Rommen 2002).

But what makes sounds right? How does “the sound of sound” (Taussig1993:80) convey religious orthodoxy, charisma, revealed truth, and soteriological potential? What do musical change and religious renewal revealabout the dynamic interrelationship of theologies and musical styles? Howare orthodoxy and orthopraxy established musically? How do local histories condition the possibility of current and future practices? To addressthese questions, I offer an intimate musical ethnography of how EstonianOrthodox Christians at a small parish in Tallinn are making their liturgical

singing “right” (aige). I suan emergent moral orderontology conflate hi notioof right singing I describecanonicity, sense of Estoni:the concept of right singining more generally “the id<(Lange 2003:6).

My ethnography is badim of Saint Simeon and tEstonia, Finland, and Russi2004-7,1 was able to obsspiritual renewal of the pinnumerable conversatiolmembers, parish priests, aiand forming a number of 1:Christian and non-Orthocchurches because, traditioest stratum of the Orthodwelcomed into the choir IMattias Palli, Father MeletkEstonia. I mention this notchameleon, but to say sonSaint Simeon and the Profmy ethnography.

My elaboration of a coanity is meant to enrich thof Christianity more geneexplores “the way Christicultures with which it ccclose dialogue with the w(1991, 1997), Engellce (20Robbins (2003a, 2003b, 21and others in the anthropcand anthropology of Chricomparative project” (Rotand practices from a nun(2003) andliton (1988) ein Baptist and Pentecostacia (1998), Spinney (2005processes of conversion a

Voc. 53,No. ETHNOMUSICOLOGY WINTER 2009 Engetba:

© 2009 by the Society for Ethnomusicology

WINTER 2009 Engethardt: Right Singing and Religious Ideology 33

rthodoxIc, Theology,

faruqi 1983; Beck 2006;md the efficacy of sacred;ical practices are “right” insthetic ideals and religiousin the “right place,” and

•e performed “in the right?88:83), and the right kind)th creates and expresses af ethnographies that showNasr 1997; Nelson [1985]igage correctly the divineis tantamount to knowingting to God, deities, spirits,communion with, channel;ate for the divine “simpLyp4:19). The wrong sounds,manity from itself and the‘4; Rommen 2002).sound of Sound” (Taussigrevealed trtith, and soted religious renewal reveals and musical styles? Howcally? How do local histocure practices? To address‘ography of how Estonianare making their liturgical

singing “right” (oige). I suggest that the “rightness” of their singing registers

an emergent moral order and reveals how religious ideology and musical

ontology conflate in notions of musico-religious orthodoxy. While the kind

of right singing I describe relates to a specific understanding of Orthodox

canomcity sense of Estonianness, and engagement in post-Soviet “transition,”

the concept of right singing I develop is translatable; it relates to understand

ing more generally “the ideology of how divinity manifests in musical sound”

(Lange 2003:6).My ethnography is based on fieldwork from 2002 to 2007 at the Cathe

dral of Saint Simeon and the Prophetess Hanna in Tallinn and elsewhere in

Estonia, Finland, and Russia. In 2002-3 and for several months each year in

2004-7, I was able to observe and participate in the musical, physical, and

spiritual renewal of the parish by singing regularly in the choir, engaging in

innumerable conversations and conducting formal interviews with choir

members, parish priests, and congregants, recording services and rehearsals,

and forming a number of lasting friendships. Although I am not an Orthodox

Christian and non-Orthodox are often not permitted to sing in Orthodox

churches because, traditionally, male singers are ordained and form the low

est stratum of the Orthodox clergy (see Seppala 2005:9), I was nevertheless

welcomed into the choir byTerje Palli, the choir leader at the church, Father

Mattias Path, Father Meletios Ulm, and Stefanus,Metropolitan of Tallinn andMl

Estonia. I mention this not to suggest that I am a desirable singer or religious

chameleon, but to say something about how Orthodoxy is practiced at the

Saint Simeon and the Prophetess Hanna parish and the dynamics that shape

my ethnograpliy.My elaboration of a concept of right singing in Estonian Orthodox Christi

anity is meant to enrich the scope and critical lexicon of the ethnomusicology

of Christianity more generally. Through sound, this branch of the discipline

explores “the way Christianity becomes local and forms relations with the

cultures with which it comes into contact” (Robbins 2003a:196) and is in

close dialogue with the work of Cannell (1999,2006), Comaroff and Comaroff

(1991, 1997), Engeilce (2007), Engeilce andTomlinson (2006), Keane (2007),

Robbins (2003a, 2003b, 2004a, 2004b, 2007), Smilde (2007),Wanner (2007),

and others in the anthropology ofChristianity Together, the ethnomusicology

and anthropology of Christianity form an emergent kind of “self-conscious,

comparative project” (Robbins 2003a: 191) that interrogates Christian beliefs

and practices from a number of different perspectives. For instance, Lange

(2003) and Titon (1988) explore the role of language and spiritual charisma

in Baptist and Pentecostal musical practices. Engethardt (forthcoming), Gar

cia (1998), Spinnev (2005), and Vaffier (2003) examine the place of music in

processes of conversion and missionization. Rappoport (2004) and Shenruan

34 Ethnomusicotogy, Winter 2009 Engel

(2002,2005,2007) situate Christian musics within processes of social and religious transformation. Romanowsld (2000) and Rommen (2002,2006,2007)connect the production of popular music to Christian ethics. Mendoza (2000),Reily (2002), and Scniggs (2005) look at syncretism, indigenization, and ritualin South America. Barz (2003), Muller (1999, 2005), and Sanga (2006, 2007)engage performance, gender, and musical creativity inAfrican Christianities.A host of scholars, including Barz (2005), Gray (1995), Lassiter (2001), Lassiter, Ellis, and Kotay (2002), Lind (2003), Palackal (2004), and Stifiman (1993)have set out ways of approaching Christian hymnody, composition, and chant.finally, Bohiman (2002), Chow (2006), and Mazo (2006) have articulatedthe role of Christian musics in migration and the construction of diasporicidentities. Right singing in Estonian Orthodox Christianity re-echoes thesethemes, presenting new comparative possibilities in the process. It also offersnew ways of approaching the relationship of Christianity and sound throughreligious ideology; the making of religious imaginaries, affect, and multiplekinds of translation.

Estonian Orthodoxy and Orthodoxy in EstoniaEstonian Orthodoxy has its historical roots in the conversions of Estonian

peasants in the Baltic provinces of Uvland (in the 1840s) and Estland (in the1880s),which were shaped by tsarist Russification policies and politics of confession and conversion.While these conversion movements were motivatedas much by rumors of economic and social gain as by religious conviction(Ryan 2004), they nevertheless established a critical mass of Orthodox Estomans.By the end of the nineteenth century almost one-quarter of the Estomanpopulation of Liviand and Estland was Orthodox (Raun 2001:80), althoughProtestantism was by far the dominant form of Estonian Christianity.

As part of the Estoman national movement that began in the 1860s andin response to the revolutionary events of 1905 and the advent of an independent Estonian nation-state in 1918-20, Orthodox Estonians increasinglyasserted their administrative and spiritual autonomy from the Russian Orthodox“Mother Church.” In 1923 an autonomous Orthodox Church of Estoma (OCE)was established under the jurisdiction of the Patharchate of Constantinople.

With the Soviet annexation of Estonia in 1941 and again in 1944, theecciesial autonomy of the OCE was revoked and Orthodox churches in Estoma were placed under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate ofMoscow (Sötov2002). Official, and at times militant, Soviet atheism meant that dozens ofOrthodox churches were closed, clergy were forced from their positionsand taxed at high rates, ritual was suppressed, religious education was proscribed, and worshipers faced discrimination at school, in the workplace,and in securing certain social benefits.

The marked declinduring the Soviet perioand spiritual renewal ocal treatment of Orthothe Estonian state lega]within the Republic ofout Estonia chose to uior the Patriarchate of 1Malong ethnolinguistic hiformally renewed theessentially a schism bePatriarchate of Constarthe Patriarchate of Mo:over church propertiessituation, the current Pties to Estonia, where hibeing elevated to PatrllOrthodox Christians ina personal connectionof his cooperation withof the OCE have made Iimperialist interventior

While the Estoniannational Church today (ilarge number of Russianwho came to Estonia dithird-generation descersocial and religious lancin the ethnolinguistic idshape Estonian society.mg the removal of a Sodebates in Estonia andlanguage policies, cultuFederation. The involve:is as pronounced as it is

The Ideal of Right SOh Kristus, Sa valgust:köik maailma otsad.VSinust oigel vllsil laula

Oh Christ,You fflumm

Engetbardt: Right Singing and Religious Ideology 35

The marked decline in religious education and public ritual expressionduring the Soviet period forms the backdrop of the post-Soviet institutionaland spiritual renewal of Estonian Orthodoxy (for a more complete historical treatment of Orthodoxy in Estonia, see Engelhardt 2005:9-16). In 1993the Estonian state legally recognized the OCE and its rights to propertieswithin the Republic of Estonia. In 1996, Orthodox congregations throughout Estonia chose to unite with either the Patriarchate of Constantinopleor the Patriarchate of Moscow, which happened almost without exceptionalong ethnolinguistic lines. Also in 1996, the Patnarchate of Constantinopleformally renewed the ecdesial autonomy of the OCE, prompting what isessentially a schism between the predominantly Estonian Church of thePatriarchate of Constantinople and the predominantly Russian Church ofthe Patriarchate of Moscow. This touched off an ongoing public disputeover church properties and canonical authority. To further complicate thesituation, the current Patriarch of Moscow andAll RussiaAlexei has strongties to Estonia,where he was born in 1929 and served as Metropolitan untilbeing elevated to Patriarch of Moscow and MI Russia in 1990. Thus, manyOrthodox Christians in Estonia, Russian-speaking and Estonian alike, havea personal connection to PatriarchMexei. However, for others, allegationsof his cooperation with the KGB and his firm stance against the autonomyof the OCE have made PatriarchMexei a symbol of illegitimacy and Russianimperialist intervention.

While the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church remains the de factonational Church today (albeit within a markedly secular Estonian society), thelarge number of Russian-speaking industrial laborers and military personnelwho came to Estonia during the Soviet period (and now their second- andthird-generation descendants) have profoundly transformed the Estomansocial and religious landscape. Orthodoxy, therefore, is perforce implicatedin the ethnolinguistic ideologies and geopolitical struggles that continue toshape Estonian society The violent demonstrations in April 2007 surrounding the removal of a Soviet World War II memorial, for instance, intensifieddebates in Estonia and throughout the European Union about citizenship,language policies, cultural rights, and economic relations with the RussianFederation. The involvement of Orthodox Christianity in these phenomenais as pronounced as it is complex and contradictory.

i processes of social and reommen (2002,2006,2007)dan ethics.Mendoza (2000),m, indigenization, and ritual‘5), and Sanga (2006,2007)ity inAfrican Christianities.1995), Lassiter (2001), Las-(2004), and Stifiman (1993)dy, composition, and chant.o (2006) have articulatedconstruction of diasponcchristianity re-echoes thesein the process. It also offersistianity and sound throughtharies, affect, and multiple

Estonia

the conversions of Estoniane 1840s) and Estland (in thei policies and politics of contnovements were motivated-i as by religious convictionical mass of Orthodox Estot one-quarter of the Estonianx (Raun 2001:80), althoughstonian Christianity.that began in the 1860s andand the advent of an indeodox Estonians increasingly.y from the Russian Orthodoxlox Church of Estonia (OCE)riarchate of Constantinople.941 and again in 1944, theOrthodox churches in Estoriarchate ofMoscow (Sötovieism meant that dozens offorced from their positionseligious education was prott school, in the workplace,

The Ideal of Right SingingOh Kristus, Sa valgustasid oma tulemise hiligusega ja röömustasid oma ristigaköik maailma otsad.Valgusta oma tundmise valgusega nende südameid, kesSinust oigel vusil laulavad.

Oh Christ,You illumined with the radiance ofYour coming and gladdened

with Your cross all the ends of the earth. Illumine with the light ofYourknowledge the hearts of those who sing ofYou in the right way.—(Canon for Sunday Orthros, first mode, fifth ode irmos from the service books ofthe Orthodox Church of Estoma)

Among the practices and processes animating Estonia’s post-Soviet transition, religious renewal in mainstream Protestant and Orthodox Christianities,more marginal evangelical, Pentecostal, and charismatic Christianities, andneotraditional religious movements merit special attention. These processesof renewal are significant because, in different ways, they both recognize andresist conventional aspects of the modernity mythologized in post-Soviet andpostsocialist transition and ostensibly figured in the European Union: democracy, liberal pluralism, secularism, free markets, cosmopolitanism, universalhuman rights, consumerism, individualism,”normalc” and benign nationalism(Asad 2003;Berdaffl, Bunzl, and Lampland 2000; Buchanan 2005;Hann 2002;Rausing 2004; Slobin 1996; Szaek 2006;Verdery 1996, 1999).

For the faithful of the OCE, religious renewal is a process of investingtheir lives in the post-Soviet order with a particular morality and soteriologI believe that this process is fundamentally about singing; it is a musico-religious poetics whereby Orthodox Christians are transforming understandingsof personhood, human ecology, and secularism in Estonian society throughsonic ideals that have decided moral and ideological dimensions (Rommen2002:53-57,2007). At the same time, being both Estonian and Orthodox iscontradictory; it goes against the ethnoreligious“essentialism in everyday life”(Herzfeld 1997:31) that casts Orthodoxy as the “Russian faith” (vene usk) incolloquial Estonian speech. Furthermore, the schism between the OCE,whosemembership of around 20,000 is almost exclusively ethnic Estonian, and theEstonian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate,whose membershipof around 150,000 is almost exclusively Russian-speaking, reveals the divisive ethnollnguistic, geopolitical, and religious ideologies shaping OrthodoxChristianity in Estoma today. Thus, the musical and liturgical practices, congregational life, and institutional affiliations of local Orthodox communities inEstoma bring together a host of aesthetic, theological, social, and ideologicalconcerns.

Mi of these concerns coalesce in the ideal of right singing.As I understandit, the ideal of right singing expresses beliefs about the efficacy of sound andstyle that are also beliefs about religious truth, confessional differences, anda right way of being in the world. As the epigraph above makes clear, rightsinging is a conduit of ifiumination and transforms individual and corporatebodies into Orthodox bodies of Christ. Right singing creates the correctunity of doxa (belief) and praxis (practice) that is the conservative essenceof Orthodox Christianity. This correct unity is inherent in the literal meaning

36 Ethnomusicotogy, Winter 2009 Engethar

of Orthodoxy as “right belmg how tensions betweenpotentially ambivalent outvparticipation are managed ii395-96). Debates over theaige(austamise)usk (rightgest how important the dua(Kaljukosk 1997, 1998; Palltruths and refines the sens(Hirschkind 2006:10,37). Uthat singing is right; if the 5<in that belief are right.

The seeming fallacy oflogic is what it is not—is imusical change in the OCIgets at things that are hardnuminous, and apophatic’through the positive statemfor non-Orthodox ethnogracorrect unity that makes siiin the visual realm: appreheicon not just an icon’s likerand pedagogical functions,prototypical form and makfor intercession or miraculchallenge is to hear and thprocesses of religious renestitutional, national, and Euitransition are mediated thiOrthodox chants and hymr

There is another aspectof its correct unity of doxaorthodox; it highlights the faorthopraxy (correct practitianity, singing is believing ‘is about singing the right ‘

ideal of right singing positssinging as well (Rappaportwrites Bourdieu, disclosesof different or antagonistic]primal state of innocence 0:tion ofmodern Christian rn

I

Engethardt: Right Singing and Religious Ideology 37

e with the light ofYourn the right way.os from the service books of

g Estonia’s post-Soviet transiand Orthodox Christianities,arismatic Christianities, andti attention. These processesays, they both recognize and:hologized in post-Soviet andthe European Union: democcosmopolitanism, universal[alcy,” and benign nationalismBuchanan 2005;Hann 2002;y 1996, 1999).val is a process of investingflar morality and soteriology.Lit singing; it is a musico-relitransforming understandingsin Estonian society through)gical dimensions (Rommenth Estonian and Orthodox is‘essentialism in everyday life”“Russian faith” (vene usk) inism between the OCE,whosevely ethnic Estonian, and thearchate,whose membershiptn-speaking, reveals the dlvideologies shaping Orthodoxand liturgical practices, con:al Orthodox communities inogical, social, and ideological

right singing.As I understandout the efficacy of sound andconfessional differences, andaph above makes clear, rightrms individual and corporatesinging creates the correctt is the conservative essencetherent in the literal meaning

of Orthodoxy as “right belief” and “right glory” or “right worship,” suggesting how tensions between the impenetrable inwardness of belief and thepotentially ambivalent outward acceptance of religious order through ritualparticipation are managed in Orthodox Christianity (Rappaport 1999:119-24,395-96). Debates over the use of the Estonian terms aigeusk (right belief),Oige(austamise)usk (right [worship] belief), and ortodoks (Orthodox) suggest how important the dual meaning of Orthodoxy is to Orthodox Estonians(Kaljukosk 1997, 1998; Paffi 1996). Thus, right singing confirms Orthodoxtruths and refines the sensibilities that aspire to right action in the world(Hirschkind 2006:10,37). II the singing is right, then the belief expressed inthat singing is right; if the belief is right, then the musical practices groundedin that belief are right.

The seeming fallacy of this self-referential musico-religious logic—andlogic is what it is not—is precisely what I want to use here in examiningmusical change in the OCE since the mid-1990s. The ideal of right singinggets at things that are hard for ethnomusicologists to get at: belief, faith, thenuminous, and apophatic ways of knowing through negation rather thanthrough the positive statements of modem scholarly practice. The challengefor non-Orthodox ethnographers like myself, then, is to apprehend at all thecorrect unity that makes singmg right. One can imagine a similar challengein the visual realm: apprehending according to the Orthodox theology of theicon not just an icon’s likeness, but something of its presence (its narrativeand pedagogical functions, the meaning and religious truth it preserves inprototypical form and makes accessible through veneration, and its potentialfor intercession or miraculous intervention). In the pages that follow, mychallenge is to hear and think beyond sound and style to show how localprocesses of religious renewal, understandings of Orthodox canonicity, institutional, national, and European identities, and experiences of post-Soviettransition are mediated through the “apt performance” (Asad 1993:62) ofOrthodox chants and hymns.

There is another aspect of right singing to consider here as well. By virtueof its correct unity of doxa and praxis, right singing helps make Orthodoxyorthodox; it highlights the fact that, in this case, orthodoxy (correct belief) andorthopraxy (correct practice) are interdependent. Within Orthodox Christianity, singing is believing when what matters is doxa, and being Orthodoxis about singing the right way when what matters is praxis. However, theideal of right singing posits the possibility of another (or heterodox) kind ofsinging as well (Rappaport 1999:438-39). “Orthodox or heterodox belief,’writes Bourdieu, discloses an “awareness and recognition of the possibilityof different or antagonistic beliefs” (1977:164). With right singing, then,”theprimal state of innocence of doxa” (ibid.: 169) is transformed by the recognition of modern Christian musical practices that give voice to other religious

38 Etbnomusicotogy Winter 2009 Engetbar

truths.Authenticity; canonicity and catholicity; at issue since at least the timeof the Ecumenical Councils, fe-emerge as deeply historical ideologies, andthe “authorizing processes” (Asad 1993:37) that create “truthful utterancesand practices” (ibid. :45) become increasingly sensible through sound. Thus,as I document below in the case of the Cathedral of Saint Simeon and theProphetess Hanna inTaliinn, right singing is as much about the practicalities ofOrthodox liturgy as it is about claiming the right history (a European history),responding in the right way to changing social and economic conditions,and imagining oneself in the right Orthodox world (a world that is distinctfrom, but not alien to Russian Orthodoxy). Making Estonian Orthodox singing right is a kind of post-Soviet religious renewal charged with emotions,hill of ideological significance, and of great value for the ethnomusicologyof Christianity and other religious traditions.

The Sound of Transitions

The transitional nature of right singing I emphasize here involves responding to, drawing on, disavowing, and transforming aspects of the post-Soviet transition that continues to reshape the lives of Orthodox Estonians.It also involves transitions toward an ever more ideal practice of Orthodoxy,transitions with a profound sotenological trajectory.While these transitionalaspects of right singing merge through Orthodox Estonians’ everyday engagement with the world, they are particularly audible in moments invested withexceptional meaning, and also in humorous moments.

One such moment that sticks out in my mind happened during a regular Tuesday night choir rehearsal at the Cathedral of Saint Simeon and theProphetess Hanna in January 2006. Terje Palli, the choir leader and wifeof the parish priest, was introducing us to a special new litany for use inan upcoming liturgy. This liturgy was significant because a member of theparish and choir was to be consecrated as a deacon (the first step in becoming an Orthodox priest). Usually, the choir would sing simply harmonizedEstonian litanies of “Issand, heida armu” (Lord, have mercy) adapted fromthe Russian Obikbod (see figure 1). Briefly, an Obilthod (from the Russianword for “common”) is a collection of chant formulae and liturgical hymns.The Russian Obilthod currently in widespread use took shape through thework ofMeksey L’vov (1798-1870) and others at the Imperial Capella in SaintPetersburg in the nineteenth century. Strongly influenced by secular Italianand German styles, the L’vov Obilthod was published in 1848, later revisedby Nikolai Bakhmetev (1807-91), and became the official service book forall Orthodox churches in the Russian Empire (von Gardner 1980:110; Harri2007; Morosan 1994:78-83).

figurer. Obilthod litany in

(l

Issand, heida armu Issand, heida arm

b‘l

What Terje introducedByzantine litanies sung in Císon (drone) (see Figure 2),listically recognizable aspeci2006:149).

There are a number oftByzantine litanies sung in Gand parishioners at the Cathinvest Byzantine chant andgraphically distant with spebecause they sound the nghimaginary; they distinguish EOrthodox Obilthod-inspiredher forties, Byzantine sound:“more monastic” than the fsian Orthodox and Protestaworshipers to the “right 1evtranslator in her thirties wh

figure 2. Byzantine litany Iinian and Greek)

4 ,—---Ta- sand, hci-da

:: ----[•- Jfl J

Is - sand,Ky - Ti

heiC

Engethardt: Right Singing and Religious Ideology 39

.t issue since at least the time)ly historical ideologies, andt create ‘truthful utterancesmsible through sound. Thus,iral of Saint Simeon and theich about the practicalities ofhistory (a European history),il and economic conditions,rorld (a world that is distincting Estonian Orthodox singwal charged with emotions,tue for the ethnomusicology

emphasize here involves resforming aspects of the post-lives of Orthodox Estonians.ideal practice of Orthodoxy,:toryWhile these transitionalx Estonians’ everyday engageble in moments invested withoments.tind happened during a regudral of Saint Simeon and the‘Ii, the choir leader and wifespecial new litany for use inmt because a member of theacon (the first step in becomuld sing simpiy harmonizedd, have mercy) adapted froma Obilchod (from the Russian)rmulae and liturgical hymns.I use took shape through theat the Imperial Capella in Sainti influenced by secular Italianiblished in 1848, later revisede the official service book for(von Gardner 1980:110;Harri

fIgure 1. Obilthod litany In Estonian adapted by Terje Palli

tJ “Issand, helda armu Issand, heida annu Is - sand, hal - da ar - mub .t .IL5) t t t t r II

What Terje introduced us to instead were monophonic, modal, moreByzantine litanies sung in Greek (“Kyrie eleison”) and accompanied by an(son (drone) (see Figure 2), one of the most theologically symbolic and stylistically recognizable aspects of Byzantine chant (Lind 2003:196-203; Ungas2006:149).

There are a number of reasons whyTerje and the choir would use theseByzantine litanies sung in Greek to make this liturgy special. Singers, priests,and parishioners at the Cathedral of Saint Simeon and the Prophetess Hannainvest Byzantine chant and styles of singing perceived as temporally or geographically distant with special significance. These ways of singing are rightbecause they sound the right religious ideology and create the right religiousimaginary; they distinguish Estonian Orthodoxmusical practices from RussianOrthodox Obilthod-inspired practices. forAnu, a graphic and textile artist inher forties, Byzantine sounds are “right” because they are “more archaic” and“more monastic” than the Estonian Orthodox traditions with marked Russian Orthodox and Protestant Lutheran influences; Byzantine sounds bringworshipers to the “right level” (interview, 28 July 2004, Tauinn). For Llisi, atranslator in her thirties who shares the “same taste” in Orthodox singing as

FIgure 2. ByzantIne litany In the first mode adapted by Terje Pa]li (In Estonian and Greek)

. ----..

] j ] ]‘“Is - sand, hei - da ar - mu Is - sand, has daKy-si - a a- Id - lou Ky-n - a a -

J —] TrJ ]ar - - - - - - -

- mu1e - - - - -

- - son,- Th

Is - sand, hal - daKy - ri - a a

ar - - muIn - I - so

40 Ethnomusicotogy, Winter 2009

Terje, Byzantine ways of singing are “more ascetic” and evoke the “feeling”that is such an important part of Orthodox Christian experience (interview,11 July 2004, Taffinn). For Reimo and Helina, both professionals in their fifties, Byzantine ways of singing bring them “to the source” of the Christiantradition, to the “unison” revealing that “everything is blessed” (interview, 8August 2004, Tallinn).

But at that Tuesday night rehearsal, making singing right meant thatsome men struggled with the Ison, and particularly with finding the ascending perfect fourth at the second “Kyrie eleison.” Pausing to drill those of ussinging the íson, Terje reiterated the interval a number of times and then,perhaps in a flashback to her childhood music lessons, segued seamlesslyinto the opening bars of “Unbreakable Union,” the anthem of the formerSoviet Union and melody of the current anthem of the Russian Federation(Daughtry 2003) that begins with a prominent ascending perfect fourth.ForTerje’s generation, this was the ideologically appropriate melody taughtfor aural skills in Soviet music schools. The laughter that ensued, then,sprang from the humorous out-of-placeness, but also the utility, of Terje’slighthearted invocation of shared childhood experience. The multilayeredsignificance and paradox of Orthodox Estonians using “Unbreakable Union”to sing the Ison of a Byzantine litany the right way thus encapsulates thetransitional nature of right singing and the nested musical, soteriological,and post-Soviet trajectories that shape its temporality.

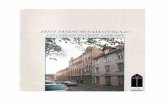

The Cathedral of Saint Simeon and the Prophetess Hanna

The Cathedral of Saint Simeon and the Prophetess Hanna is situated amongthe many new commercial and residential buildings nearTaflinn’s Baltic harborthat have sprung up during the Estonian economic boom that began in the late1990s. Its history bears witness to the turbulent dynamics of religion, nation,and ideology in Estonia from tsarist times to post-Soviet transition. Accordingto legend, the church stands where sailors in the Russian navy built a chapelfrom the rubble of a shipwreck in 1752-55. In 1827 and again in 1870, thechurch was enlarged into the shape of a cross and elaborated with a centralonion-shaped cupola, a bell tower, and decorative wooden trim in the traditional Russian style. With the advent of an autonomous OCE and a nationalizing Estonian state in 1918-19, the church was turned over to an Estoniancongregation served byAnton Liar (1885-1933).During the interwar Republicof Estonia, the congregation grew to include nearly 450 Estonian Orthodoxbelievers and was served for almost two decades by Nikolai Pats (1871-1940),the brother ofEstonian head of state Konstantin Pats (1874-1956).In the 1920sand 1930s, congregational life at the parish was nurtured through the choralsociety Helila and a number of dramatic societies.

Engeth

During Soviet occuption was subject to intenpriest at the church in tlifaithful to the ecclesial othe Soviet-backed authoriAs a result of the increaKrushchev, the church wtower and onion-shapedfacts removed. In the 1 9•hail. With the advent ofgation began using the 1until 1999, when the citownership reforms and t

In 2000, Patriarch oftion of the Cathedral ofthodox Estonians began’made up of icon paintenofficers, former member:pensioners, and schoolchPart occasionally worshijgregation is young, well-cnumber of converts (EnIthedral of Saint Simeonthe church’s 250th anni’autonomy of the OCE anment to the myths and idclaims and claims about hserves as the episcopalleader of the OCE.

The Cathedral of Sambuilt environment it is pasition. This kind of transitthe temporal lag implicitand regimes of this kindor “European integration,’right (Kennedy 2002). Asits congregation are partists, consumers, capital, idness,Westernness, and “nOrthodox Estonians, the tiof this kind of transition Uthey imagine leading. Th

I

Engethardt: Right Singing and Religious Ideology 41

:etic” and evoke the “feeling”-istian experience (interview,oth professionals in their fifthe source” of the Christianhing is blessed” (interview, 8

ng singing right meant thatlarly with finding the ascendt.” Pausing to drill those of usa number of times and then,c Lessons, segued seamlessly,“ the anthem of the formerm of the Russian Federationnt ascending perfect fourth.Ly appropriate melody taughtlaughter that ensued, then,but also the utility, of Terje’sxperience. The multilayeredis using”Unbreakable Union”it way thus encapsulates theested musical, soteriological,iporality.

e Prophetess Hanna

ietess Hanna is situated amongngs nearTallinn’s Baltic harboruc boom that began in the late.t dynamics of religion, nation,st-Soviet transition. Accordingae Russian navy built a chapel11827 and again in 1870,theand elaborated with a centralLive wooden trim in the tradi)nomous OCE and a national-as turned over to an Estonian‘.During the interwar RepublicLearly 450 Estonian Orthodoxs by Nikolai Pats (1871-1940),Pats (1874-1956).In the 1920ss nurtured through the chorales.

During Soviet occupation,’ the ritual and spiritual life of the congregation was subject to intensifying suppression. Pavel Kalinldn (1880-1961), apriest at the church in the mid-1940s, was defrocked in 1948 for remainingfaithful to the ecciesial order of the interwar OCE and failing to recognizethe Soviet-backed authority of the Patnarchate ofMoscow (Sötov 2004:175).As a result of the increasingly militant atheism of the Soviet regime underKrushchev, the church was closed in 1963, its property nationalized, its belltower and onion-shaped cupola dismantled, and its icons and liturgical artifacts removed. In the 1970s the building was converted for use as a sportshail. With the advent of perestroika in 1987, however, a Pentecostal congregation began using the building for worship and ran a soup kitchen thereuntil 1999, when the church was returned to the OCE through post-Sovietownership reforms and the intervention of the Estonian state.

In 2000, Patriarch of Constantinople Bartholomew blessed the restoration of the Cathedral of Saint Simeon and the Prophetess Hanna, and Orthodox Estonians began worshiping there anew. Today, the congregation ismade up of icon painters, graphic designers, architects, musicians, militaryofficers, former members of the Estonian parliament, students, translatofs,pensioners, and schoolchildren, for instance. The renowned composerArvoPart occasionally worships there when he is inTallinn. In general, the congregation is young, well-educated, cosmopolitan, and includes a significantnumber of converts (Engelhardt forthcoming). The restoration of the Cathedral of Saint Simeon and the Prophetess Hanna, completed in time forthe church’s 250th anniversary in 2005, is a tangible sign of the restoredautonomy of the OCE and the restored Estoman state; it is a physical monument to the myths and ideologies of restoration and to anachronistic moralclaims and claims about historical justice (Bohlman 2000). Today, the churchserves as the episcopal seat of Metropolitan Stefanus, the Greek Cypriotleader of the OCE.

The Cathedral of Saint Simeon and the Prophetess Hanna and the newlybuilt environment it is part of epitomize a particular kind of post-Soviet transition. This kind of transition redresses what, from a Western perspective, isthe temporal lag implicit in the term “post-Soviet.” The practices, processes,and regimes of this kind of transition, commonly glossed as “globalization”or “European integration,” are a transnational cultural formation in their ownright (Kennedy 2002). As part of this transition culture, then, the church andits congregation are part of an ever-intensifying circulation of travelers, tourists, conswners, capital, ideas, and sounds and stand at a frontier of Europeanness,Westernness, and “normalcy” (Asad 2003:171;Wallerstem 2006).Yet forOrthodox Estomans, the trajectories, geopolitics, ideologies, and moral normsof this kind of transition do not correspond entirety with the Orthodox livesthey imagine leading. There is “friction” (Tsing 2005) in the globalism and

42 Ethnomusicotogy, Winter 2009 Engetbt

“engaged universality” (ibid. :6-11) of transition; for Orthodox Estonians, someaspects of transition are not entirely right.

The Theology and Efficacy of Right Singing

By virtue of being theologically correct, affective, sensate, and ethical,singing as it happens at the Cathedral of Saint Simeon and the ProphetessHanna is right. Recalling the literal meaning of Orthodoxy as “right belief”and “right glory” or “right worship,” right singing is an ideal fashioned byOrthodox Estonians that guides them in righteous living. Right singing putsinto everyday practice the intimate relationship within Orthodox Christianity of beauty and truth, aesthetics and veracity. It is inseparable from thesynesthetic reality of Orthodox liturgy that incorporates hymnody and chant;the broadly cast pealing of bells; the mystical presence of the Eucharist; theacoustics and architectural symbolism of the church building; interlockingcycles of liturgical and secular time; sacred texts articulated through theheightened speech of priests, deacons, and readers; the sanctifying smell ofincense which lifts human prayers to God; the presence of icons whose prototypical, true images instruct and are conduits for devotion and intercession;the ritual gestures, clothing, and liturgical instruments used by the clergy;and the tastes and anointing touches worshipers experience. Right singingis equally inseparable from transformative experiences of conversion andrenewal and individual disciplines involving dress and comportment, fasting, efforts to attend services on workdays, and “the honing of an ethicallyresponsive sensorium” (Hirschldnd 2006:10).

Right singing echoes theological and liturgical imperatives codifiedby the Church fathers and the Ecumenical Councils in the first centuriesof Christianity as well. Traditionally, musical instruments are proscribed inOrthodoxy because of their artificiality as human creations, their association with worldly activities like dance and work, and their alienation fromlanguage,which renders them incapable of prayer.2 The human voice is theideal source of Orthodox sound because of its nature as a creation of God,its intimate connection to language and efficacy in prayer, and the way itenhances audition and affective experience. Thus, right singing is exclusively vocal. Following certain Neoplatomc strands of Orthodox thought,right singing is the re-sounding of divine musical prototypes (much like theway in which icons are the re-presentations of prototypical images) and itunites the earthly worship of humans, the heavenly worship of angels, andthe choirs of saints in a sacred hierarchy.

The essence of right singing is the system of eight modes or chant formulae known in Estonian as tautuviisid or just vilsid (oktoëchos in Greek,oktoicb in Russian). The Estonian word viis (plural viisid) comes from the

German weise, which ca:significant for the ideal oright melody, and to wor:for instance, in the Canotranslate “kes Sinust oigelFor Orthodox Estonians,the right way” and “who sconfirmed this by askingtexts where the meaninlto preserve both meaninEstonian word for the nu:onym with the word vils

These modes are oiendar in seven-day cyclafter Holy Pascha [Easteliturgical seasons, the cyone week, second mode(celebrated on Saturdaymoves from darkness into the liturgical year, the:Christ rose from the deweek of the Old Testamday. Orthodox Estoniansthe fifth mode:

Oh seda suurt imet! llmthuiLooja, kes armastusest inimliha poolest kannatas, töusi:surematu surnuist üles. Tulrahva suguharud, kummardTeda, sest meie, kesTema aioleme eksitusest päästetudoppthud laulmaMnujumahkolmes Palges.

(Stichera for Sunday yesthodox Church of Eston

In any given servicchoir using the eight mlauluvilsid adapted fromternalized these modessigns showing how to siiare hardly mute, howeve

Engethardt: Right Singing and Religious Ideology 43

for Orthodox Estonians, some

nging

iffective, sensate, and ethical,t Simeon and the Prophetess)f Orthodoxy as “right belief”gmg is an ideal fashioned byous living. Right singing putsp within Orthodox Christianity It is inseparable from therporates hymnody and chant;presence of the Eucharist; thechurch building; interlocking:exts articulated through theaders; the sanctifying smell ofpresence of icons whose pro-for devotion and intercession;;truments used by the clergy;ers experience. Right singing:periences of conversion anddress and comportment, fastd “the honing of an ethically

:urgical imperatives codifiedouncils in the first centuriesnstruments are proscribed iniman creations, their associaork, and their alienation fromtayer.2The human voice is the:s nature as a creation of God,:acy in prayer, and the way itThus, right singing is exclu;trands of Orthodox thought,cal prototypes (much like the)f prototypical images) and itavenly worship of angels, and

i of eight modes or chant for-st viisid (oktoëcbos in Greek,plural viisid) comes from the

German welse, which can mean both “way” and “melody.” This polysemy issignificant for the ideal of right singing: to sing the right way is to sing theright melody, and to worship the right way is to use the right melodies. So,for instance, in the Canon for Sunday Orthros on pages 25-26, I chose totranslate “kes Sinust oigel vilsil laulavad” as “who sing of You in the right way.”for Orthodox Estonians, however, this can mean both “who sing ofYou inthe right way” and “who sing ofYou with the right melody.” Informally, I haveconfirmed this by asking Orthodox Estonian friends to translate hymns andtexts where the meaning of vhs is ambiguous. In many cases, they soughtto preserve both meanings in their translations. Incidentally, vhs is also theEstoman word for the numberS. Unsurprisingly, no one associates this homonym with the word vhs meaning “way” or “melody.”

These modes are ordered according to the Orthodox liturgical calendar in seven-day cycles commencing on Thomas Sunday (the Sundayafter Holy Pascha [Easter]). With a few exceptions for special feasts andliturgical seasons, the cycles progress sequentially each week (first modeone week, second mode the next, and so on) at the SundayVespers service(celebrated on Saturday evening), the beginning of the Orthodox day thatmoves from darkness into light. In addition to giving musical expressionto the liturgical year, these eight modes are theologically significant in thatChrist rose from the dead on the eighth day, thus uniting the seven-dayweek of the Old Testament with the redeemed time of this eternal eighthday. Orthodox Estonians sing about this at Sunday Vespers in the week ofthe fifth mode:

Oh seda suurt imet! llmthuta vägedeLooja, kes armastusest inimeste vastuliha poolest kannatas, töusis kuisuremam surnuist üles. Tulge köikrahva suguharud, kummardagemTeda, sest meic, kes Tema armu läbioleme eksitusest päastetud, olemeoppinud laulmaMnujumalastkolmes Palges.

Oh what great wonder! The unincarnateCreator of all powers, who, out oflove for humanity, suffered of the fleshand rose immortally from the dead.Come all nations and worship Him,for we who are saved from sin throughHis love have been taught to singof the One God in Three Persons.

(Stichera for Sunday Vespers, fifth mode, from the service books of the Orthodox Church of Estonia)

In any given service, the bulk of texts like this are performed by thechoir using the eight modes. Orthodox Estonians use simply harmonizedlauluvilsid adapted from the Russian Obilchod. Most choir members have internalized these modes and sing from service books that have only texts andsigns showing how to sing the flexible chant formulae. These service booksare hardly mute, however. Experienced singers who understand the relation-

44 Ethnomusicotogy, Winter 2009 Engell

ship of the lauluvilsid and the liturgical calendar understand the intimaterelationship of certain fixed texts and their corresponding modes. However,for the ethnomusicologist to hear and interpret this aspect of right singing assomething primarily musical would misrepresent the ontology of Orthodoxsound. Estonian words like teenima (to serve) or tugema (to read), used todescribe sung participation in Orthodox liturgy suggest that, in importantways, right singing may not be singing at all. Rather, it can be understood asthe efficacious sound of heightened speech, sacralized language, and divineprototypes. In terms of Orthodox theology, it is the sounding beauty of theword that is the essential complement to and vessel of its semantic meaningand truth claims.

Right singing is also how Orthodox Estomans situate themselves withina global religious imaginary that embraces Orthodox Christians under thejurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople (including Mount Athos,the Orthodox Churches of Finland and England, and the Greek OrthodoxArchdiocese ofAmerica) and the Church of Greece. While different usesof Byzantine musical style reveal the geography and temporality of thisimaginary, it also involves particular circulations of people, sounds, ideas,knowledge, and capital. Terje Path and the parish priests at the Cathedral ofSaint Simeon and the Prophetess Hanna have spent years studying in Greeceand Finland; choir members and parishioners make frequent pilgrimagesto Greece and Cyprus, for instance; and the church has received Byzantineicons from museums in Greece. Then there is Metropolitan Stefanus, theGreek Cypriot leader of the OCE who has served in African missions andas a bishop in southern France. He was appointed by the Patriarch of Constantinople and enthroned as Metropolitan ofTallinn andMl Estonia in 1999.His presence in Estonia owes to the fact that after the OCE’s autonomywas restored, there were no suitable candidates to lead the Church. This isone of the legacies of the Soviet period, when being a celibate priest andacquiring the advanced theological training needed to become an Orthodoxbishop were nearly impossible for Estonians (although more possible forRussian speakers). Metropolitan Stefanus is a gifted singer and has beeninstrumental in creating a Byzantine trajectory in Estoman Orthodox musical practices through his words and deeds (see Stefanus’ recent articles onByzantine music [2006a, 2006b]).

So, since the 1990s, being part of this Byzantine imaginary has enabledreligious renewal and, in the process, established alternative, Orthodox perspectives on the modernity being fashioned through post-Soviet transition,refraining its liberal ideologies and doctrine of secularism. The Byzantineaspects of right singing, in other words, create a form of “morally inflectedcosmopolitanism” (Hirschkind 2006:121) that is given voice through liturgical practice at the Cathedral of Saint Simeon and the Prophetess Hanna.

The Sound of Right

To the extent that elthe ProphetesS Hanna iObilthod, it is part of acal practices emerge inas part of Russian Orthc(Kan 1999; Geraci andStark 2002; Stokoe 199in terms of right singingthese practices are non-they are everywhere lo

In terms of the cbsOrthodoxies, local Obi(mythic) associationWitStories about the comirand Finland and the imaemphasize the Byzantinbringing closure to thcentury mission of SainEngethafdt 2005;PajamHilkka Seppälä, for instsounds similar to man)earliest church singingby one of the foundingthe twelfth century)” (my experience,the Byz;practices, particularly iiLmtula Convent, is bec(in a more thoroughgoinparishes (Olldnuora an

Glancing through 9EstonianiZed versionselia (the locus of the Imonly called the “NortMonastery in the Ka1uPskov region of Russiahome to one barely sudesignated as being fras being “Coptic” or “Brestrained, word-centelperceive as the operat

Engetbardt: Right Singing and Religious Ideology 45

dar understand the intimateresponding modes. However,this aspect of right singing as:nt the ontology of Orthodoxor lugema (to read), used toy suggest that, in importantither, it can be understood ascralized language, and divines the sounding beauty of theessel of its semantic meaning

ins situate themselves withinthodox Christians under the‘pie (including Mount Atlios,iid, and the Greek Orthodoxireece. While different usesphy and temporality of thisrns of people, sounds, ideas,sh priests at the Cathedral of)ent years studying in Greecemake frequent pilgrimagesurch has received Byzantines Metropolitan Stefanus, theved in African missions andtted by the Patriarch of Conaffinn andAfi Estonia in 1999.t after the OCE’s autonomys to lead the Church. This is1 being a celibate priest andded to become an Orthodoxalthough more possible forgifted singer and has beenin Estoman Orthodox musiStefanus’ recent articles on

ntme imaginary has enabledd alternative, Orthodox per-rough post-Soviet transition,f secularism. The Byzantinea form of “morally inflecteds given voice through liturgitd the Prophetess Hanna.

The Sound of Right SingingTo the extent that everyday singing at the Cathedral of Saint Simeon and

the Prophetess Hanna is based on an Estomanized version of the RussianObildiod, it is part of a global phenomenon whereby local Orthodox musical practices emerge in the Finno-Ugi-ic world, NorthAmerica, and East Asiaas part of Russian Orthodox missiomzation and Russian imperial expansion(Kan 1999; Geraci and Khodarkhovsky 2001; Kivelson and Greene 2003;Stark 2002; Stokoe 1995; Werth 2002; Znamenski 1999). What is importantin terms of right singing, however, is that through habit, language, and abilitythese practices are non-derivative, non-syncretic, integral, and untranslatable;they are everywhere local (Engethardt 2006).

In terms of the closely related musical practices of Estonian and FinnishOrthodoxies, local Obildiod-inspired ways of singing are valued for their(mythic) associationwith the canomcal prototype of the Byzantine oktoëchos.Stones about the communication of Orthodoxy to Finno-Ugrians in Estoniaand Finland and the imaginative dimensions those Orthodoxies assume todayemphasize the Byzantine origins that shape the present and future, in a sensebringing closure to the religious transmission that began with the ninth-century mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius (Ambrosius and Haapio 1979;Engethardt 2005; Pajamo andThpputamen 2004; Papathomas and Palli 2002).Hilkka Seppala, for instance, stresses that although Finnish Orthodox musicsounds similar to many Slavic Orthodox traditions, “it is believed that theearliest church singing was directly connected with the Byzantine traditionby one of the-founding fathers of the oldest Karelian monastery (from aboutthe twelfth century)” (1 999:162-63; also see Seppala 1981, 1982, 1996). Inmy experience, the Byzantine orientation of some Finnish Orthodox musicalpractices, particularly in Karelian parishes and at theValamo Monastery andLintula Convent, is becoming increasingly pronounced and echoes, perhapsin a more thoroughgoing fashion, similar changes happening in some Estonianparishes (Olldnuora and Seppäla 2007).

Glancing throughTerje Paffi’s handwritten service notebooks, one findsEstonianized versions of hymns from the Valamo Monastery in Russian Karella (the locus of the Byzantine translation Seppala describes above, commonly called the “Northern Athos”),3 the Kiev Caves Monastery the OptmaMonastery in the Kaluga region of Russia, and the Petsen Monastery in thePskov region of Russia (situated a few kilometers from the border and stifihome to one barely surviving Estoman congregation).4 Other melodies aredesignated as being from Greece, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Moscow, and Finland, oras being “Coptic” or “Byzantine.” Terje also cultivates an ascetic, vibratoless,restrained, word-centered vocal technique in contradistinction to what someperceive as the operatic excesses and purely aesthetic concerns of certain

46 Ethnomusicotogy, Winter 2009 Engelbard

Christos anesti ek nekron,thanato, thanaton patisas,kai tois en tots mnimasi zomcharisamenos.

Christ is risen from the dead,trampling down death by death,and upon those in the tombs bestowinglife.

powerful and palpable waysized “by non-Greeks as an ai2004, Teqe Paffi introducedthe Liturgy of Saint John CliFigure 4). Her new settingquite clearly what the Byza:of theology, aesthetics, affec

Issand, mötle mete peale, omaskuningrilgis.

Ondsad on need, kes vaimus vasest nende päralt on taevanilc.Ondsad on need, kes kurvad o;sest nemad peavad röömustudOndsad on tasased,sest nemad peavad maad pärinOndsad on need, kel nalg ja jaröiguse järele,

sest nemad peavad täis saama.Ondsad on armulised,sest nemad peavad armu saam:Ondsad on need, kes puhtad Sisest nemad peavad Jumalat natÔndsad on rahunöudjad,sest neid peab Jumala lapsilcs lOndsad on need, keda tagalduöiguse pärast,

sest nende pkult on taevarlik.öndsad olete teie, kui inimeseminu parast laimavad ja taga

ja köiksugu kurja teie peale räkui nemad valetavad.

Roomustage ja olge väga röömsest teie palk on suur taevas.

Teije first uniin Heinävesi, Finland, wheremonastery’s choir. The me]Russian znamenny chant,thirteenth century whose nthe Russian word for sign (notation of Byzantine chanithe introduction of “polyphi2000:251;alSo see Swan 19Russian Orthodox musical psound connects to a distanihad not yet been transform’

urban Slavic styles. In general, then, what is sung at the Cathedral of SaintSimeon and the Prophetess Hanna, and, just as important, how it is sung,localizes temporally and geographically distant Orthodox sounds in order tomake singing right. In this way, the Byzantine orientation of musical changeat the parish makes immanent sense; Byzantine is a chronotope (a temporaland spatial field of action) incorporating aspects of musical style, theology,and religious imagination that captures what singers sense as the archaic,originary, and more authentic qualities of their way of singing. Negotiating thiskind of proximity (Rommen 2002,2007; Palackal 2004:248) within a globalByzantine imaginary as part of the ongoing renewal of Estoman Orthodoxyand amidst ongoing social, economic, and ideological transformation, then,is a process of making singing right.

I can recall a number ofmoments when the Byzantine orientation of rightsinging was particularly audible. One was at an ecumenical song festival inthe coastal village of Häademeeste near the Latvian border. There, we sang“Hristos Anesti” (Christ is risen), the troparion (a short hymn specific to agiven date, feast, or saint) for Holy Pascha. The choir sang this troparion notonly because it was the Paschal season, but also to recognize and celebrate,asTerje Palli explained,”our archpastor Metropolitan’s country of origin [Cyprus] .“ In addition to being sung in Greek, this troparion is rife with Byzantinesignifiers, most notably its mode (first mode,pentafonos) and the presenceof the json drone (see Figure 3).

As part of everyday liturgical practice at the Cathedral of Saint Simeonand the Prophetess Hanna, the Byzantine chronotope is present in no less

FIgure 3. “Hristos Anesti,” transcribed and arranged by Terje Paffi

______________-

‘— I,

V

Chris- ma a - ens - ti ek nek - ran, lisa - en - to tha - na- ton pa -

i ‘] i ]:i It) Ls

Ii - - sas, kai tom en tois miii - ma -

4cI ]‘fl j j j IIsi zo - in cha - ri - sa - - me -

Engetbardt Right Singing and Religious Ideology 47

ing at the Cathedral of SaintIs important, how it is sung,Orthodox sounds in order torientation of musical changeis a chronotope (a temporalts of musical style, theology,singers sense as the archaic,-ay of singing. Negotiating thisat 2004:248) within a globaltewal of Estonian Orthodoxy)logical transformation, then,

Byzantine orientation of right; ecumenical song festival intvian border. There, we sang(a short hymn specific to achoir sang this troparion notJ to recognize and celebrate,)litan’s country of origin [Cy)parion is rife with Byzantine?ntafonos) and the presence

from the dead,‘n death by death,•e in the tombs bestowing

ie Cathedral of Saint Simeonnotope is present in no less

tnged by Terje PaUl

ftno - to, Usa - no- ton pa -

]Ien tots mni - ma

] I- (i.. IIme -

Issand, mOtle meie peale, omaskuningrilgis.

Ondsad on need, kes vaimus vaesed,sest nende paralt on taevarlik.Ondsad on need, kes kurvad on,sest nemad peavad rOömustud saama.Ondsad on tasased,sest nemad peavad maad pänma.Ondsad on need, kel nälg ja janu onoiguse järele,

sest nemad peavad tais saama.Ondsad on armulised,sest nemad peavad armu saama.Ondsad on need, kes puhtad südamest,sest nemad peavad Jumalat nagema.Ôndsad on rahunöudjad,sest neid peab Jumala lapsilcs hüütama.Ondsad on need, keda tagakiusatakseöiguse pärast,

sest nende paralt on taevarilk.Ondsad olete teie, kui inimesed teidminu pärast laimavad ja tagaldusavad,

ja köilcsugu kurja teie peale raagivad,kui nemad valetavad.

Röomustage ja olge väga röömsad,sest teie palk on suur taevas.

Lord, remember us in Yourkingdom.

Blessed are the poor in spirit,for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.Blessed are those who mourn,for they shall be comforted.Blessed are the meek,for they shall inherit the earth.Blessed are those who hunger andthirst after righteousness,

for they shall be filled.Blessed are the merciful,for they shall receive mercy.Blessed are the pure in heart,for they shall see God.Blessed are the peacemakers,for they shall be called the sons of God.Blessed are those who are persecutedfor righteousness’ sake,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.Blessed arc you when men shall revileyou and persecute you,

and shall say all manner of evil againstyou falsely for My sake.

Rejoice and be exceedingly glad,for great is your reward in heaven.5

powerful and palpable ways that show how its “sonic attributes” can be localized “by non-Greeks as an aural badge of Orthodoxy” (Lingas 2006:149). In2004, Terje Paffi introduced a new arrangement of the third antiphon fromthe Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom into the Sunday morning liturgy (seeFigure 4). Her new setting ofThe Beatitudes (Matthew 5:3-12) representsquite clearly what the Byzantine chronotope means at the parish in termsof theology, aesthetics, affect, and ideology.

Terje first encountered this melody in the 1990s at theValamo Monasteryin Heinävesi, Finland, where she transcribed it from photocopies used by themonastery’s choir. The melody Terje transcribed and arranged comes fromRussian znamenny chant, the body of monophonic chant dating from thethirteenth century whose name, owing to the way it is notated, derives fromthe Russian word for sign (znamya) and suggests a direct connection to thenotation of Byzantine chant. Znamenny chant predates by several centuriesthe introduction of “polyphonic singing in the Western manner” (von Gardner2000:251; also see Swan 1940a, 1940b, 1940c; Takala-Roszczenko 2007) intoRussian Orthodox musical practices.What Orthodox Estonians call its “archaic”sound connects to a distant past when Russian Orthodox musical practiceshad not yet been transformed by the Western staff notation, triadic harmony,

Engetbardt

and conventional tonality arrborderlands in the mid-sevenihas long figured into the imalOrthodoxy that claims and bnotably in the singing of Oldto accept the musical and litim 1652.

Drawing on the Byzantis1996:169-75), Teije added ato me, she commented that ijokingly, “besides, what else.arrangement for a Finnish tnadapted it to Estonian. Shespirit (meeteotu) than the Ssyllables must be sung at thtand the tapering sound thatalso worth noting that in ordeparted from the official tnby her husband, Father Mattireads,”Ondsad on need, kes 1’(Blessed are those who are sOCE service book reads “Onare the sorrowful, for they si

The Byzantine chronotmade present and affectivethe monophonic znamennyacterizes as having a “low s&ascetic manner of singing.for instance, creates an impiand conventional tonalitiesEstonian Orthodox musicalthe Prophetess Hanna andparishes like the Church 01Tartu, the Byzantine chrornnewal, new iterations of reliright. For some Orthodox 1are not enough. Their relattoo obscure and not adequof sound. Furthermore, thetices with nationalist, seculreligious values, in other wThese Orthodox Estonians

Figure 4. “Ondsuse salmid (The Beatitudes),” znamenny melody with isonarranged by Terje Palli

4 ]J]jIs - sand, mgt - In mel - e pea - In, o - man ku - fling - eli - gin.

4j ] ]Ond - sad on need, ken vai - inns van - ned, sent nen - de pls - ralt on

II ] Jtae - - - -

- va-ndc. Ond-sad on need,ken kur-vad on,

4 TJ ]T j llj,jnest ne-mad pea-vad rOO mns-thd san - - - ma. Ond-sad on Ia - ta-ned,

jfl J]]J]nest ne- mad pea - vad maad pg - - ri-ma. Ond.sad on need,kel nlg ja

] JJja - nu on öi - gu-se j - in- Ic, sent ne- mad pea.vad tam san - - ma.

j J j I j ] JOnd.sad on ar-mu-li-ned, nest ne- mad pca-vad ar-mu san - - - ma.

J]- J J JOnd-sad on nced,kes puh-tad sIt - da-mest, sent ne- mad pea-vad Ju - ma - Jet nIt -

‘ U t ] I jj- ge-ma. Ond.sad on ra - hu- nItud - jail, nest neid peals

4—Ju - ma - Ia lap - aiks hUg - - - -

- Ia - ma.

4—Ond - sad on need, ke - da Ia - ga - kin - sa - tak - Se UI - gu - se pA - rant,

4 J J r IIScSI nen - de pA - mit on tan -

‘___ ç_,.ì S.’

-- va-riik.

Engetbardt Right Singing and Religious Ideology 49

and conventional tonality arriving from the lithuanian, Polish, and Ukrainianborderlands in the mid-seventeenth century. For this reason, znamenny chanthas long figured into the imagination of and struggle for an authentic RussianOrthodoxy that claims and bears musical witness to Byzantine origins, mostnotably in the singing of Old Believers, the Orthodox Russians who refusedto accept the musical and liturgical reforms implemented by Patriarch Nikonin 1652.

Drawing on the Byzantine sound of theValamo tradition (Seppäla 1981,1996:169-75), Terje added an ison to the znamenny melody. Explaining thisto me, she commented that it “gives depth” to the antiphon and then addedjokingly, “besides, what else should the basses do?” Teije initially made thisarrangement for a Finnish translation of the Slavonic original, and only lateradapted it to Estoman. She feels that the Estonian variant has a differentspirit (meeleolu) than the Slavonic original due to the fact that additionalsyllables must be sung at the ends of phrases, disturbing singers’ expirationand the tapering sound that naturally occurs when singing in Slavonic. It isalso worth noting that in order to work with the znamenny melody, Teqedeparted from the official translation found in the OCE service book editedby her husband, Father Mattias Paffi. For example,whereTeije’s arrangementreads,”Ondsad on need, kes kurvad on, sest nemad peavad röömustud saama”(Blessed are those who are sorrowful, for they shall become gladdened), theOCE service book reads “Ondsad on kurvad, sest neid lohutatakse” (Blessedare the sorrowful, for they shall be consoled) (Aposttik-öigeusu 2003:46).

The Byzantine chronotope so valued by some Orthodox Estonians ismade present and affective in this antiphon through the limited ambit ofthe monophonic znamenny melody; its particular modalitywfflchTerje characterizes as having a “low seventh” (väike septim); the Ison; and the choir’sascetic manner of singing. Terje’s emphasis on its distinctive low seventh,for instance, creates an implicit distinction relative to the triadic harmoniesand conventional tonalities that characterize mainstream, Obilthod-inspiredEstonian Orthodox musical practices. At the Cathedral of Saint Simeon andthe Prophetess Haima and other younger, more urban, more cosmopolitanparishes like the Church ofAll Saints Alexander in the university town ofTartu, the Byzantine chronotope creates new possibilities for religious renewal, new iterations of religious ideologies, and newways ofmaking singingright. For some Orthodox Estonians, localized, Obilthod-inspired practicesare not enough. Their relation to the prototypical Byzantine oktoëchos istoo obscure and not adequately rooted in an authentic Orthodox theologyof sound. Furthermore, the lingering association of Obikhod-inspired practices with nationalist, secular, Slavic aesthetics (musical values rather thanreligious values, in other words) is deemed improper (Seppälä 1999:165).These Orthodox Estomans want to worship and live Orthodox lives using

znamenny melody with Ison

J J ] Ii IInun ku - ning - ru - gin.

J.,J :L “sent nen - Un pa - mit on

I jj J J ] IOnd-sad on need,kes kur-vad on,

, II]JJ]J T- ma. Ond-sad on ta - sn-ted,

ii.. II I ]] J ] Jönd.sad on nned.kel n5g ja

Saa - - ma.

‘.—‘mu saa - -

- ma.

;iI ipea-vad Ju - ma - at ad -

t J. adud- jad, sent neid peab

.ma.

]Se öi - gu-ne pg - rust,

II-

- va-milk.

50 Ftbnomusicotogy, Winter 2009 Engetbardt

originary, authentic, true Orthodox sounds, sounds that are “revered for soundmg canonical” (Qureshi 2006:28; also see Rappaport 1999:342) and ensurethat their singing is right.

ConclusionA number of questions remain: Why does the Byzantine chronotope

play such an important role in making Estonian Orthodox singing right?Why do some Orthodox Estonians work so hard to establish themselvesmusically within a global Byzantine Orthodox imaginary? What kind ofworldare they making when they align processes of musico-religious renewal andtrajectories of post-Soviet transition? Here, and by way of conclusion, I willsuggest some possible answers to these questions and return to the generaldisciplinary concerns with which I began.

The ideal of right singing gives voice to eternal religious truths thatempower Orthodox Estonians to live faithfully and in relation to God, oneanother, and a global religious community The soteriological, ethical, andaffective dimensions of right singing are profound, and by singing the rightway, Orthodox Estonians realize their full humanity through the unity ofbeauty and truth, aesthetics and veracity Timothy Ware (Bishop Kaffistos ofDiokleia), one of the most influential theologians in the Orthodox world ofthe Patriarchate ofConstantinople, addresses this with regard to the Orthodoxtheology of the icon:

The image denotes the powers with which each one of us is endowed by Godfrom the first moment of our existence;the likeness is not an endowment whichwe possess from the stan, but a goal at which we must aim, something whichwe can only acquire by degrees. However sinful we may be, we never lose theimage; but the likeness depends upon our moral choice, upon our “virtue:’ andso is destroyed by sin .. . Humans at their first creation were therefore perfect,not so much in an actual as a potential sense. Endowed with the image from thestart, they were called to acquire the likeness by their own efforts (assisted ofcourse by the grace of God). (1997:219)

By endeavoring to sing the right way, then, Orthodox Estonians work at incrementally transforming themselves, their Church, and their world into thislikeness. Musical practice, in other words, is an agentive means of religioustransformation as it shapes individual and communal disciplines, sensibilities,and moral actions.

As a time-bound expression of Orthodox Christianity, the ideal of rightsinging is a thoroughly sociohistorical and ideological phenomenon as well.Orthodox Estomans are making choices about how to sing the right waybased on their own musico-religious sensibilities, their experiences of preSoviet national independence, Soviet life, and post-Soviet transition, and the

imaginative horizons unfoldieconomic integration. Therearbitrary, nor is it ideologicaL

The temporal and geograthe ways Orthodox Estoniansnumber of reasons. Crucially,geopolitics, social struggle anand the stereotypical conflatiEstonia (Orthodoxy being thcase of the Valamo znamenn’dible debt to Byzantine traditown, Orthodox Estonians areRussian traditions without eLutheran, the mainstream Esition with Baltic German hegcReptiblican-era Estonian OrtJ(Engethardt 2005:108-209).

What the Byzantine chrOrthodox Estonians to the cinary Christianity. That this ctrajectory of Estoman post-Schronotope, I suggest, is righand geographies that mergegration and figured in the Euisinging is transforming quotia markedly secular post-SoviNömmik 2004), right singingseem to be shaping the moc2006). And as evidence of ccsinging also challenges cony’Union as a godless spiritual ‘

Because Orthodox Estonitheir “ strong religion” (Mmonof ideological struggles and aand the status of ChristiamtethnomusicologistS and anthright singing necessitates hesocial processes that are not

Beyond these conclusiortonians is right (conclusions Ione verges on matters of beliethat reveal the limits of how a

Engethardt: Right Singing and Religious Ideology 51

LfldS that are “revered for soundpaport 1999:342) and ensure

es the Byzantine chronotopenian Orthodox singing right?hard to establish themselvesimaginary? What kind ofworldmusico-religious renewal andLd by way of conclusion, I willions and return to the general

eternal religious truths thatly and in relation to God, onehe soteriological, ethical, andjund, and by singing the rightimanity through the unity of)thyWare (Bishop Kaffistos ofans in the Orthodox world ofis with regard to the Orthodox

ch one of us is endowed by God:ness is not an endowment which1 we must aim, something which‘ui we may be, we never lose thetal choice, upon our “virtue,” andcreation were therefore perfect,ndowed with the image from theby their own efforts (assisted of

ihodox Estonians work at inurch, and their world into thisn agentive means of religiousuunal disciplines, sensibilities,

Christianity, the ideal of rightlogical phenomenon as well.it how to sing the right wayties, their experiences of preost-Soviet transition, and the

imaginative horizons unfolding before them through European and globaleconomic integration. Therefore, the Byzantine chronotope is anything butarbitrary, nor is it ideologically neutral or precise in terms of musical style.