Early infantile manifestations of incontinentia pigmenti mimicking acute encephalopathy

Reporting public manifestations of religious beliefs: Sikhs, Muslims and Christians in the British...

Transcript of Reporting public manifestations of religious beliefs: Sikhs, Muslims and Christians in the British...

Inés

Olz

a, Ó

scar

Lou

reda

& M

anue

l Cas

ado-

Vela

rde

(eds

) • L

angu

age

Use

in t

he P

ublic

Sph

ere

This book comprises a range of general discus-sions on tradition and innovation in the method-ology used in discourse studies (Pragmatics, Discourse Analysis, Argumentation Theory, Rhetoric, Philosophy) and a number of empirical applications of such methodologies in the anal-ysis of actual instances of language use in the public sphere – in particular, discourses arising in the context of the debate on the presence of religious symbols in public places.

ISBN 978-3-0343-1286-8

Inés Olza is Post-Doctoral Research Fellow with GRADUN (Discourse Analysis Group, University of Navarra) in ICS (Institute for Culture and Society). She also works as a Lecturer in General and Spanish Linguistics at the Spanish National University for Distance Education (UNED, associ-ated center in Pamplona). Her research focuses on the semantic-pragmatic analysis of phraseol-ogy and metalanguage (of Spanish and other languages), on multimodality, and on the argu-mentative use of figurative language in public discourse.

Óscar Loureda is Chair Professor of Spanish Linguistics at the University of Heidelberg (Ger-many), and since 2011 he has been the director of the University’s Iberoamerika-Zentrum. He is also a member of the Research Group “Dis-course Particles and Cognition” in the Heidel-berg University Language and Cognition Lab (HULC LAB). His research interests center on Semantics and Lexicography of Spanish, and on general theory of discourse (Text Linguistics, Text Grammar, Discourse Analysis).

Manuel Casado-Velarde is Chair Professor of Spanish Linguistics at the University of Navarra (Spain), where he directs the interdisciplinary Research Project “Public Discourse: Persuasive and Interpretative Strategies” at the Institute for Culture and Society (ICS) and the Navarra Re-search Group on Discourse Analysis (GRADUN). He is a Corresponding Member of the Royal Spanish Academy. His research currently focuses on Text Linguistics and Discourse Analysis.

li170 li170 Studies in Language and CommunicationLinguistic Insights

Pete

r La

ng

Inés Olza, Óscar Loureda &Manuel Casado-Velarde (eds)

Language Use inthe Public Sphere

www.peterlang.com

li170

Methodological Perspectives andEmpirical Applications

PETER LANGBern • Berlin • Bruxelles • Frankfurt am Main • New York • Oxford • Wien

Language Use inthe Public Sphere

Methodological Perspectives andEmpirical Applications

Inés Olza, Óscar Loureda & Manuel Casado-Velarde (eds)

The publication of this book has been funded by the Research Project FFI2010-20416 of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (“Metodología deanálisis del discurso: propuesta de una lingüística del texto integral”); and bythe Project “Public Discourse” (GRADUN) of the Institute for Culture andSociety (ICS) of the University of Navarra.

ISSN 1424-8689 pb. ISSN 2235-6371 eBookISBN 978-3-0343-1286-8 pb. ISBN 978-3-0351-0526-1 eBook

© Peter Lang AG, International Academic Publishers, Bern 2014Hochfeldstrasse 32, CH-3012 Bern, [email protected], www.peterlang.com, www.peterlang.net

All rights reserved.All parts of this publication are protected by copyright. Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, withoutthe permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution.This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming,and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

Printed in Switzerland

Bibliographic information published by die Deutsche NationalbibliothekDie Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche National-bibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at ‹http://dnb.d-nb.de›.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: A catalogue record for this bookis available from The British Library, Great Britain

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Language use in the public sphere : methodological perspectives and empirical applications / Inés Olza, Óscar Loureda & Manuel Casado-Velarde (eds.).pages cm. – (Linguistic insights, studies in language and communication ; v. 170)Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 978-3-0343-1286-81. Discourse analysis–Political aspects. 2. Rhetoric–Political aspects.3. Mass media and language. 4. Public speaking. I. Casado Velarde, Manuel. editor of compilation. P301.5.P67L36 2014401‘.4–dc23

2014011797

Contents

INÉS OLZA, ÓSCAR LOUREDA & MANUEL CASADO-VELARDEPreface .................................................................................................. 9

Part I. Tradition and Innovation in the Methodology of Discourse Studies

TOMÁS ALBALADEJORhetoric and Discourse Analysis........................................................ 19

MANUEL CASADO-VELARDETrust and Suspicion as Principles of Discourse Analysis................... 53

LOURDES FLAMARIQUEMetaphor and Argumentative Logic – a Crossroads between Philosophy and the Language Sciences.............................................. 79

FRANK J. HARSLEM & KATRIN BERTYA ver, what do we have here? – Bueno, it’s no piece of cake. The Challenge of Translating Conversational Discourse Markers... 107

FERNANDO LÓPEZ-PANThe Epideictic Nature of Prestige Newspapers ................................ 145

ÓSCAR LOUREDANew Perspectives in Text Analysis: Introducing an Integrated Model of Text Linguistics. .............................................. 161

JOSÉ PORTOLÉS & JEAN YATESThe Theory of Argumentation within Language and its Application to Discourse Analysis ................................................... 201

6 Contents

JEF VERSCHUERENThe Pragmatics of Discourse in the Public Sphere........................... 225

ALEJANDRO G. VIGODiscourse, Coherence, Truth ............................................................ 237

Part II. Empirical Applications: Public Discourse Concerning the Presence of Religious Symbols in Public Spaces

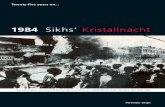

RUTH BREEZEReporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs:Sikhs, Muslims and Christians in the British press .......................... 271

DOLORES CONESAThe Dialectic of Identity-Difference ................................................ 309

DIEGO CONTRERASThe Crucifix and the Court in Strasbourg: Press Reaction in Italy to a European Court Decision...................... 327

PATRICK DUFFLEYCraving Face: the Debate over the Islamic Veil in Quebec as Reflected by the Discourse of the Three Major Political Parties............................................................ 351

ALBERTO GILPublic Discourse on the Internet:Interactive Control of the Integration Debate in German................. 375

RAMÓN GONZÁLEZ RUIZ & DÁMASO IZQUIERDO ALEGRÍAThe Debate about the Veil in the Spanish Press. Boosting Strategies and Interactional Metadiscourse in the Editorials of ABC and El País (2002–2010)........................... 397

Contents 7

SIRA HERNÁNDEZ CORCHETE & BEATRIZ GÓMEZ-BACEIREDOWho Tells the Story of “the War of Religious Symbols”? An Analysis of Genette’s Categories of Voice and Point of Viewin ABC, El Mundo and El País Reports on the Withdrawal of the Crucifix and the Prohibition of the Veil in Spain................... 445

CARMEN LLAMAS SAÍZ & CONCEPCIÓN MARTÍNEZ PASAMARVocabulary and Argumentation in the Spanish Press Discussion about Islamic Veil. Metaphorical Projections of Burqa ................... 481

ANDRÉS OLLEROReligious Symbols in Public Spaces: Ethical and Legal Argumentation ................................................................................. 503

INÉS OLZARepresentation in the Spanish Press of the Political Debate about Wearing Full Islamic Veils in Public Spaces ................................... 521

Notes on Contributors....................................................................... 557

RUTH BREEZE

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs: Sikhs, Muslims and Christians in the British Press1

In recent years, controversy has surrounded public manifestations of religion, particu-larly the wearing of specific items of dress or accessories which appear to come into conflict with safety regulations or social expectations. This chapter examines British newspaper reporting on this issue, by conducting an in-depth analysis of news and opinion articles about the wearing of symbolic items by members of three different religions (Sikhs, Muslims and Christians). We analysed one hundred articles pub-lished in the online versions of four UK newspapers (Guardian, Telegraph, Mirror and Sun) in the first six months of 2010. A multi-dimensional approach was adopted, taking into account the following aspects: analysis of issue framing, identifying fram-ing elements within the text; explicit evaluation of the main actors (religious groups, government, groups seeking to impose prohibition of religious symbols); lexical items and metaphors in the text associated with the different parties and with the banning of religious symbols. On the level of framing and explicit evaluation, the articles gener-ally voiced both sides of the controversy in sober, neutral tones. However, greater emotional content was perceptible in the metaphors and emotionally-charged lexical items used, particularly in the context of Islamic attire.

Keywords: Discourse analysis; Framing; Metaphor; Appraisal analysis.

Introduction

In the late 2000s, the public manifestation of religious identity through the wearing of specific symbolic items attracted a considerable

1 The research for this chapter was undertaken as part of the research projects “Public Discourse: Persuasive and Interpretative Strategies” (Gradun; Institute for Culture and Society, University of Navarra), and “Metadiscourse and Evaluative Language: Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Journalistic Discourse” (MINECO; ref. FFI2012-36309).

Ruth Breeze 272

amount of media attention. The reporting on these issues was interest-ing on various levels. First, many ideas were being aired, but these rarely seemed to consolidate into coherent arguments. A new issue culture appeared to be forming around this topic, but the notions were still confused. Second, the protagonists of the various incidents and test cases, who were often members of ethnic minorities, clearly felt that they had suffered discrimination. This aspect clearly calls into question the manner in which these cases were being presented in the media, with a particular focus on who was telling the story or who was allowed to express an opinion. Third, the debate surrounding these topics often became heated, perhaps because it touched the sensitive issues of religion, on the one hand, and immigration, on the other. It is important to attempt to gauge the emotivity aroused by these issues, and to assess how this affected the representation of the different groups involved. This chapter will adopt a multidimensional approach in order to explore the framing of the issue in ideational terms, the extent to which the actors were allowed to voice their own concerns, and the emotional temperature of the debate.

1. Historical background

In order to understand the context of this study, it is necessary to situ-ate the events which formed the subject of the newspaper articles against the historical background of Britain, a traditionally Christian country with a large immigrant population. This section will provide a brief overview of the three religious groups which form the object of this study, followed by a short account of the related issues that were in the public eye in early 2010.

1.1. Sikhs

There are around 20 million Sikhs in the world, most of whom live in the Punjab province of India. Sikhism is a monotheistic religion which was founded in the Punjab by Guru Nanak in the 15th century. Sikhs

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 273

are recognized by their “5 Ks”, which are: kesh (long hair), kara (a steel bangle), kirpan (a small knife or dagger), kashera (special un-derwear) and kanga (a comb worn under the turban). The first major Sikh migration to Britain was in the 1950s, consisting mainly of men from the Punjab seeking work in British industry, which had a short-age of unskilled labour. Most of the new arrivals worked in foundries and in textile factories. Subsequent waves of Sikh migration came via East Africa, as a result of the Africanisation programmes in the 1960s and 1970s. As these Sikhs had been living as an expatriate community in Africa for over 70 years they were used to being a highly visible minority, and to maintaining their own traditions with pride. They had the further advantage of being highly skilled and employable. The advent of the second wave of immigrants via East Africa strengthened the identity of the Sikh community in Britain, and encouraged many earlier migrants to return to the 5 Ks. The turban, which all male adult Sikhs are supposed to wear to cover their long hair, was an object of polemic in the 1960s. However, the present debate about Sikh dress tends to centre on the kirpan, worn by boys and men, and on the kara. The 2001 census recorded 336,000 Sikhs living in Britain, which means that they constitute a small minority amounting to 0.4% of the population.

1.2. Muslims

Muslims affirm the oneness of God, and believe in His prophets and angels, in the books that He has revealed, in the day of judgement and in life after death. They pray five times a day and observe the holy month of fasting and discipline, called Ramadan. Many Muslims also adopt distinctive styles of dress, including long prayer robes for men, and veils or burkas for women. Islam is now the second largest relig-ion in the United Kingdom, accounting for around 3.3% of the popula-tion in the 2001 census. As is the case with the Sikhs, Muslim migra-tion to Britain has its origins in colonial history, receiving a special impetus as a result of the displacement of large populations during the partition of India, and the Africanisation policies of newly-independent East African countries in the 1960s and 1970s. Most Brit-ish Muslims are of Pakistani, Bangladeshi or Indian origin, and the

Ruth Breeze 274

majority belong to the Sunni branch of Islam. The largest Muslim communities are in Greater London, the West Midlands, West York-shire, Lancashire and central Scotland.

1.3. Christians

Christians constitute the largest religious group in the United King-dom, which has been a Christian country since the sixth century. Ac-cording to the 2001 Census, 72% of the population is Christian. The Church of England is the Established Church, and around 21% of the population of Great Britain belong to it; in terms of numbers, it is followed by the Roman Catholic Church (9%), the Presbyterian Church of Scotland (2.8%) and the Methodist Church (1.9%). Al-though Christians are not obliged to adopt distinctive styles of dress, many Christians choose to wear a cross, crucifix or religious medal.

1.4. Events in 2010

In 2010, the issue of wearing particular items of dress or accessories for religious reasons was the focus of public debate. One particular test case, involving a Christian nurse, Shirley Chaplin, who had been removed from her post because she would not take off a crucifix that she had worn for over thirty years, hit the headlines early in the year, as did the final repercussions of a similar case that had passed through the courts the year before, involving British Airways worker Nadia Eweida. The Sikh custom of carrying the dagger known as a “kirpan” was also in the news, because a boy in London was refused admission to a state school unless he removed the item, and a well-known Sikh judge, Sir Mota Singh, made public statements in his favour. Finally, the issue of wearing Burkas was mainly reported in the media in the context of French and Belgian bills to prohibit face veils, but two cases in British politics involving similar ideas (statements by Con-servative MP Philip Hollobone and the United Kingdom Independ-ence Party in the weeks before the general election) also formed the subject of news and opinion stories during this period.

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 275

2. Methodology

In this section, the theoretical background to the methods used will be discussed, followed by an overview of the corpus of newspaper texts which formed the object of this study.

2.1. Theoretical background

In a discourse analytical perspective, newspaper reports and features are an extremely complex object of study. Comparison of news stories with most argumentative genres shows that it is relatively hard to identify coherent ideological positions in news reporting, even though we may sense that the texts are not neutral. One reason for this is that in reports, unlike leaders or columns, although ideas and arguments may be mentioned, they are often not fully worked out. To compound matters, such texts are characterised by a high degree of heteroglossia, since the journalist is often concerned to show the different points of view about a particular issue, or to allow the different participants in an event to state their own opinion, which means that the news writer’s own opinion is not overtly stated. On an initial reading, the fragmentary nature of the views expressed, their different attributions, and the absence of an explicit authorial voice makes analysis more challenging (Rojecki 2005; Breeze 2011). At the same time, journal-ists may often present a biased or partial view of a subject by leaving out a particular perspective, or by giving voice to one side more than to another, rather than by stating their own view (Fairclough 1995; van Leeuwen 1996; Bednarek 2006). Since bias often results from the omission of a particular protagonist or perspective, the task of analys-ing the text is made still harder, since omissions are of their nature invisible. Finally, a further level at which ideological concerns may colour news reports occurs in the area of lexical choices. When a writer chooses a specific verb to denote an action, or uses a specific adjective or noun to characterise an actor, this choice may colour the mental picture that readers build, and may affect what might be called the emotional temperature of the text (Fowler 1991; Fairclough 1995). However, it is particularly difficult to analyse the affective or emotive

Ruth Breeze 276

level of the text, since interpretation is particularly liable to be subjec-tive.

It would thus appear that in order to conduct a balanced analysis of news articles, a multidimensional approach should be adopted. To this end, a multiplicity of techniques and methods have evolved, from corpus linguistics to qualitative study of rhetorical organisation, in-cluding many approaches that can be loosely grouped together under the heading of critical discourse analysis. This study differs from much previous work in that it attempts to bring together three methods from very different areas, in order to gain a rounded view of the phe-nomenon under scrutiny across a sizeable corpus of texts, and to ob-tain insights into the way different methodologies provide contrasting results which can help analysts to triangulate their findings. The texts will be analysed on three levels. First, it seems clear that newspaper texts need to be investigated on the level of ideas, that is, by establish-ing what notions or arguments are found in the text, voiced either by participants in the events reported, or by those involved in the writing process. This may be termed the ideational level of the text (Hyland 2005). Secondly, once these ideas have been identified, it is important to address the question of who actually speaks in the text: since much journalism makes use of direct quotation, we should examine what participants or authorities are quoted as saying what. These two ap-proaches are somewhat different, since the former is most effectively achieved by using techniques from the cognitive tradition in media studies such as frame analysis, which allow researchers to identify the ideas in a text and even to quantify the contents of a range of articles, while the latter is better addressed through qualitative and quantitative study of the texts in question and investigation of the type and amount of voice attributed to each participant. Thirdly, since our interest cen-tres on the evaluative dimension of the text, the highly complex level of lexical choice must be tackled. Here, a framework will be applied to measure the contribution of particular lexical items to the force of the propositions made. The study of voice and the analysis of lexis clearly both reflect aspects of the interpersonal or interactional dimen-sion of the text (Hyland 2005). At this point it should be stated that use of this three-pronged approach does not imply that other methods would not also provide useful insights into the texts in question. Given the size of the corpus of texts, a detailed study on many different lev-

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 277

els would be impractical. The idea is simply to apply methods from different areas covering both the ideational and the interpersonal di-mensions of the text, in order to allow a more balanced view and fa-cilitate methodological comparison.

To identify and quantify the propositions in the text, the tech-niques of frame analysis provide a useful tool. This methodology originated in cognitive psychology in the 1970s, as a way of investi-gating the cognitive structures which guide the perception and repre-sentation of reality (Goffman 1974). In everyday life, frames are usu-ally not created consciously, but are generated in the course of com-municative interaction (Gitlin 1980). In the case of media texts, such interpretive frameworks are thought to be made up of elements that are commonly juxtaposed, or non-factual elements (arguments, ideas) which are frequently associated with specific phenomena, and which may shape the way in which readers come to think of a particular is-sue, that is, how they understand its causes, evaluate its status and envisage its outcome or solution (Entman 1993). Although the concept seems clear, it often proves difficult to identify and measure frames in practice (Maher 2001). In media texts, frames are often not fully worked out, in the sense that any given news story or television inter-view may be seen to frame some aspect of a given issue in a particular way, but may also contain some contradictory elements, which mean that no coherent frame emerges. Moreover, since frames consist of tacit rather than overt conjectures, it may be hard to define them clearly.

One problem that arises when analysing news articles from the perspective of framing is that such texts often contain elements that could form part of a frame, but rarely (except in leaders or columns) present the frame in a fully developed form (Rojecki 2005). Yet the interpretations and evaluations offered in the context of news stories may have an impact on public opinion, even where they are not pre-sented as fully reasoned arguments. It is also possible that the some-what inchoate assessments of particular recurring situations in the media reflect public opinion as it is emerging. For this reason, it would seem to be appropriate to conduct analysis of the framing ele-ments, occuring in isolation or as part of a developed argument in all types of article, rather than focusing on the small number of texts that contain all the components of a frame. The present study therefore

Ruth Breeze 278

builds on the methodology described by Rojecki (2005), which sets out from an identification of what could be termed “framing ele-ments”, such as evaluative statements, and quantifies their presence in the texts, before going on to assess the extent to which they form co-herent frames. This research also draws on the notion of the “issue culture”, that is, “the taken-for-granted knowledge around a given topic” (Rojecki 2005: 66), which is the set of common frames used to structure analysis of an issue.

On a second level, regarding participants and voices in the text, a dual approach will be adopted, consisting of quantitative measure-ment of the amount of direct speech attributed to the actors, and a qualitative exploration of the nature of these voices. On the issue of voice, several specific methodological difficulties again arise in the context of news. Some authors even go so far as to rule out considera-tion of attributed statements in the analysis of media texts, on the grounds that the very fact of their being attributed to someone other than the writer means that the writer takes no responsibility for them (Bednarek 2006: 61). However, there is a considerable body of schol-arship based on Bakhtinian perspectives which highlights the impor-tance of the voices in the text, since they potentially provide the most direct line of communication between the actors and the reader, and their presence or absence may have a decisive impact on the way the media tell a story (Bakhtin 1981; Ducrot 1984; Méndez García de Paredes 1991; Reyes 1993; Calsamiglia & López Ferrero 2003). The extent to which this process is controlled or manipulated by the writer is disputed. In Ducrot’s view (1984), although the discourse subject (the writer’s voice created in the text) calls up other voices (direct speech) in order to build a particular position, media texts remain es-sentially polyphonic, and are open to multiple interpretations. In the news event schema developed by van Dijk (1988), media stories start out as a series of events and comments, and citation is a key device for giving authority and legitimacy to what is said. For van Leeuwen (1996), writers are never neutral, and their choice of who is cited, what is cited and how this is represented determines the ideological colouring of the text. However, as Calsamiglia & López Ferrero point out (2003), the use of direct citation is conventional in the mass media as a whole, and is firmly consolidated as one of the newspaper jour-nalist’s most characteristic practices. Journalists may even compensate

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 279

for their “discursive insecurity” by relying on participants’ voices to tell the story (Moirand 1997). To this extent, the need to cite and the availability of sources would tend to influence what is published just as much as any desire to maintain ideological control. As Verschueren (2011) points out, to view citations in isolation from the pragmatic functions which they have in a particular text is likely to yield inaccu-rate results.

Previous studies have focused on quantitative and qualitative approaches to voice (Hunston & Thompson 2000; Calsamiglia & López Ferrero 2003). Although quantitative methods provide insights, the results may be misleading unless they are also complemented by qualitative analysis taking the pragmatic context into account. For example, a text which makes use of extensive direct quotations may be citing them approvingly, or may be quoting them in order to shock the reader, but this difference will not emerge in a corpus study. Moreover, as we have noted, direct citation is influenced by various factors involved in the production process. First, use of extensive quo-tation belongs to what many journalists consider to be “good prac-tice”, as it tends to create a direct, punchy style and adds to the impact of the story. Second, the fact that a specific agent is quoted may be simply due to availability: journalists have limited time at their dis-posal, and they may not have access to participants on both sides. One final problem concerning this particular study lies in the attempt to distinguish between wearers of symbolic items and those supporting the wearers, since one individual might hold both roles. In this case, the decision was made to maintain the distinction, by looking at the role being adopted in each instance.

The third aspect, that of lexical choice, offers a particularly rich field for the analyst, yet is notoriously difficult to classify fairly. Criti-cal discourse analysts have often been criticised for their “impression-istic” or “manipulative” accounts of media texts (Breeze 2011). In this, the framework offered by van Dijk (1995) offers less help than might be expected. For example, in his scheme, the lexicon is pre-sented as a single aspect to be investigated, while it is obviously ex-tremely complicated (specific use of nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.; grading of different lexical choices; persons to whom these words are attributed; positive and negative uses; connotations), and intrinsically subjective. In the discussion of evaluation in news by Bednarek

Ruth Breeze 280

(2006), she points out that even though it is quite clear that news texts may have “a specific ‘evaluative prosody’” (2006: 8) resulting from the combination of different evaluative features, this is hard to analyse because there is no clearly defined list of “evaluators”, in the way that there is a more or less finite list of, say, discourse markers. Various authors have attempted to define just how the evaluative dimension of a text is constituted. According to Conrad & Biber (2000), the writer’s evaluation, which in their scheme is termed “stance”, is made up of epistemic considerations, attitudes and styles, the latter two being complex to define. On the other hand, Martin & White (2005: 31) view the evaluative dimension of text as “appraisal”, and subdivide this into graduation (force or focus), attitude (affect, judgement and appreciation), and engagement (monogloss or heterogloss). However, as Bednarek points out (2006: 32-35) even though the contribution of appraisal theory to the study of evaluation is considerable, since it provides the only existing systematic, detailed framework of evalua-tive language, it poses many challenges to the analyst: many items cannot easily be categorised, not least because a word which connotes affect in one context may imply judgement in another. On the other hand, the even more ambitious parameter-based frameworks such as those proposed by Lemke (1998), Hunston & Thompson (2000), and Bednarek (2006) are still more complex to apply, and if implemented in their entirety to a large sample of texts, are likely to produce a con-siderable body of data, much of which is merely incidental, since what is gained in scope is often lost in precision. Moreover, these methods fail to solve the initial problem, which is the dependence on the ana-lyst’s subjective perception, and the danger of taking words out of context. What is “evaluative” in one text may be neutral in another. As Verschueren (2011) points out, a substantial part of the meaning de-pends on contextual pragmatic factors, and analysts have to take pains to read the text in context. This may work well for close analysis of small samples of text, but is less reliable over a large corpus.

In order to focus on the specific topic of this research, the analysis of vocabulary is here narrowed down to what is arguably the most significant or ideologically loaded aspect of lexical choice, namely the patterns of word choice relating to how people and events are categorised. As Verschueren (2011: 133) states, patterns of lexical choice are “basic linguistic tools for categorising people, institutions,

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 281

events, actions, practices, relationships, and hence for making sense of the social world”, and categorisation can enable us to describe differ-ent phenomena as though they were the same, or to give differential treatment to comparable phenomena. Moreover, writers use a range of resources such as metonymy, metaphor or overstatement to communi-cate added meaning, and these may contribute substantially to the ideological dimension of the text (Verschueren, 2011: 171). In the present study, the investigation of lexical choices was limited to those used to refer directly to the participants, to their symbolic items, and to the removal or prohibition of these items, paying special attention to their possible affective or emotional overtones. According to Bed-narek (2006), emotivity is concerned with the writer’s approval or disapproval. Thus if a journalist calls a politician’s performance “pol-ished”, positive emotions are evoked, whereas if she calls him “fanati-cal”, the connotations are negative. However, as Bednarek points out (2006: 46-47), emotive meaning is not easily objectively verifiable or recognisable, and any interpretation is particularly liable to be subjec-tive, and interpretations of emotive connotations often diverge. Since attempts to quantify expressions of emotivity seems to be fraught with difficulty, both because the judgements involved are essentially sub-jective, and because quantification cuts the words off from their pragmatic context and renders them opaque, the approach to analysing the “emotional temperature” of the texts in this sample will be essen-tially qualitative, and will consider emotivity as broadly as possible, taking in categories such as words with obvious positive or negative connotations, intensifiers or downtoners, used to denote actors or items of dress, and dramatisations of events.

2.2. Corpus of texts

Regarding the selection of newspapers used, the decision was made to take two “quality newspapers” and two “popular newspapers” (O’Driscoll, 2000). The Guardian and the Daily Telegraph are up-market publications with a middle-class readership, while the Sun and the Daily Mirror are classic tabloids catering for a popular market. The average daily circulation of these publications in 2010 according to the Audit Bureau of Circulations is shown in Table 1.

Ruth Breeze 282

Daily Telegraph Guardian Sun Daily Mirror CIRCULATION 691,128 302,283 3,006,565 1,218,425

Table 1. Average daily circulation of newspapers in 2010.

All the newspapers chosen for the study were competing for a con-tracting readership, since the advent of online publications had made considerable inroads into the traditionally large markets for national daily newspapers in Britain. In the first half of 2010, the circulation of Daily Telegraph was slowly declining from the stable position it held at over 1 million copies a day in the 1990s and early 2000s (Luft 2010). However, the Daily Telegraph was still the market leader among the quality newspapers, followed by the Times, the FinancialTimes, the Guardian and the Independent, in that order. The Sun had also experienced a drop in sales during the same period, from close to 4 million in the 1990s, as had the Mirror, whose readership had halved during the same time.

Regarding the political orientation of these newspapers, the Daily Telegraph and the Guardian both have a long and well-consolidated position as representatives of mainstream right and left. Known in the satirical press as the “Torygraph”, the Daily Telegraphmaintained its Conservative allegiance throughout the years of Labour rule, and was consistently critical of both Blair and Brown. The Guardian’s readership is split between Labour and Liberal Democrat voters, but generally favours what is often termed a “progressive” attitude on social issues, championing the rights of women and minor-ity groups. The Sun, which is owned by Rupert Murdoch, went from being one of Margaret Thatcher’s staunchest supporters to supporting Tony Blair at the 1997, 2001 and 2005 elections. However, it has been noted that the Sun’s attitude to Labour was mainly centred on Blair and that in the 2010 the Sun returned to its Conservative sympathies with renewed vigour, launching particularly negative personal attacks on Brown (Wring & Ward 2010). The Mirror remained loyal to the Labour party even during the Thatcher era, and campaigned for La-bour in 2010. Thus at the time of the study, these newspapers can be firmly situated as follows: one quality right-wing and one quality left-wing newspaper, and one downmarket right-wing and one downmar-ket left-wing newspaper.

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 283

Regarding the type of text included in the study, an attempt was made to take in all the articles that appeared in the online versions of these publications during the time period chosen, including news sto-ries, features or interviews, and opinion articles. The distribution of the articles across these categories is shown in table 2, while the length and distribution of the articles across religious groups are set out in table 3.

NEWS FEATURE/INTERVIEW

OPINIONFOR

OPINIONAGAINST

OPINIONNEUTRAL

Telegraph 18 0 4 0 1 Guardian 21 7 6 6 5

Sun 13 2 2 0 1 Mirror 11 0 3 0 0

Table 2. Types of article from each newspaper.

NEWSPAPER NO. OFWORDS

ARTICLES:SIKHS

ARTICLES:MUSLIMS

ARTICLES:CHRISTIANS

Daily Telegraph 11,568 4 13 6 Guardian 43,940 7 22 16

Sun 7,207 0 14 4 Mirror 2,208 1 9 4

Table 3. Distribution of articles by newspaper and religion.

3. Frame analysis

The framing elements that occurred most frequently in the corpus are set out below. In each case, a quotation is supplied as an example.

1. RS constitute a problem for safety or security: “women pose a potential security threat because their faces are completely shielded from view” (Daily Telegraph).

2. RS pose a threat to (mainstream) values: “the burka demeans women by preventing people from seeing their whole faces” (Daily Telegraph).

Ruth Breeze 284

3. People have the right to wear RS: “If women can choose towear as little as they like, it is UNACCEPTABLE that they can'twear as much as they like too” (Sun).

4. Different religions are being treated differently: “it’s one rulefor Christians and another for other faiths” (Mirror).

5. The state persecutes religious believers: “perceived clampdownon religious freedom” (Daily Telegraph).

6. Religious groups are provoking a conflict: “the Christian LegalCentre, backed the case of Nadia Eweida, the BA employeewho was prevented from wearing a small cross” (Guardian).

7. Bans on wearing RS cause tension: “Racial tensions have beengrowing as France - home to 5,000,000 Muslims - prepares tointroduce an outright ban on wearing the burka” (Sun).

8. A ban on wearing RS will harm women: “a ban may lead tofurther segregation of women… Muslims may keep them be-hind locked doors” (Daily Telegraph).

9. State must act to ban RS: “as a British Muslim woman, I abhorthe practice and am calling on the Government here to followthe lead of the French proposal and ban the burka in Britain”(Sun).

10. Muslim countries are intolerant: (in Pakistan) “women are oftenpressured into adopting Muslim headwear” (Daily Telegraph).

11. Wearing RS has absurd consequences: “bride is bearded andcross-eyed behind veil” (Daily Telegraph).

12. Britain has a tradition of tolerance: “France is an increasinglydifficult place to live in. People should be more open-minded,the way they are in Britain” (Sun).

13. Companies have the right to impose dress code: “BA should befree to ban the cross” (Guardian).

14. Other EU countries (France, Belgium) are intolerant: “Sorry,but where is the equality, the égalité, in targeting a tiny group ofMuslim women?” (Sun).

Table 4 shows the rank order of the most frequent framing elements for each religious group in each newspaper.

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 285

Daily Telegraph Guardian Sun Mirror SIKHS 3, 1, 5 12, 3, 4 — — MUSLIMS 14, 2, 1, 3, 7 14, 2, 7, 5, 9, 10, 3 3, 2, 14, 1 2, 1, 14 CHRISTIANS 3, 5, 4 6, 3, 4, 5 4, 3 3, 1

Table 4. Rank order of elements for each religion according to publication.

A brief examination of table 4 shows that element 3 (“people have the right to wear religious symbols”) was the most prominent element in most cases, and was more ubiquitous than elements 1 and 2, which together constituted the main reasons against wearing religious items. In the case of Muslim dress, the intolerance of other European coun-tries was also prominent, as were the notions that religious dress go against mainstream values, and that a ban on religious dress would cause social tension. The main framing elements employed in the case of each religious group are discussed in depth below.

3.1. Framing Sikhs

Both the Daily Telegraph and the Guardian carried news and opinion concerning Sikhs during this period which contained statements that had been identified as potential framing elements. The Daily Tele-graph had 4 such articles, while the Guardian had 7. The Mirror also contained one article, but it contained only a brief statement of facts and no framing elements, while the Sun had none.

The most frequent framing element found in the articles con-cerning Sikhs in the Daily Telegraph was the idea that people have the right to wear items that constituted an expression of religious adher-ence or belief (element 3). This idea was present in all the articles published in the Daily Telegraph. The idea that the Sikhs’ religious items constitute a threat to public safety was present in two of the articles (element 1), one of which made explicit reference to the 9-11 attacks, which appear to have sparked fear of different religious groups among some sectors of the population. However, it is notewor-thy that these same articles also link this issue to the notion that the state is trying to restrict religious expression and therefore religious freedom (element 5). Thus one article alludes explicitly to “a per-ceived clampdown on religious freedom in schools”. The other men-

Ruth Breeze 286

tions two previous cases involving Sikhs, in which two public entities were found to have infringed laws against discrimination, including the Human Rights Act, which “guarantees freedom of religion”, and alludes to parallel cases involving Muslims and Christians whose rights in this sense had also been threatened. Despite these references to an ongoing debate, the tone of the articles in this publication is light and somewhat humorous, with quotations from a Sikh judge who has been carrying his Kirpan everywhere he goes for some 40 years, in-cluding visits to Buckingham Palace. Another article, by humorist Terry Wogan, is amusing in tone, and positive about the Sikhs and their colourful customs: “Well, I’m all for the turban. I’m all for the Sikhs, who seem to find an excuse for a party or a festival every cou-ple of weeks”.

The Guardian took a slightly different stance on the issue of the Sikhs’ religious items, emphasizing Britain’s tradition of tolerance, yet also pointing to inconsistencies in public policy and practice. The most frequent framing element encountered here was element 22 (Britain is tolerant of different religious and ethnic groups), followed by element 3 (people have the right to express their religious beliefs) and element 4 (different religious groups are being treated differently). The tone of the articles on Sikhs in the Guardian is markedly different from that of the articles in the Daily Telegraph, since the emphasis centres on the difficulty of the debate, the problematic nature of the religious group in question, and the real threat posed by people who carry knives and other sharp instruments.

Far from representing the Sikhs as a harmless, colourful reli-gious group, the articles in the Guardian depict a much more complex scenario. One article focuses on Sikhs who have joined extreme right-wing parties, in protest against perceived “favouritism” that gives advantages to Muslims over other groups. Another article recalls the campaign waged by Sikh employees in the Wolverhampton bus com-pany in 1967, in which they won the right to wear turbans when on duty by threatening suicide. Other articles centre on a controversial play by a Sikh woman, which Sikh community leaders had tried to suppress, and the murder of a Sikh shopkeeper in Huddersfield.

The framing elements relevant to the present issue contained in the Guardian are diverse, but the most frequent element offered is a persistent allusion to Britain’s tradition of tolerance (element 22).

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 287

However, others include the intolerance of the ethnic group itself (element 20), the threat to public safety (element 1), state intolerance of religious groups (element 3), perceived inequality between reli-gious/ethnic groups (element 4) and fear of social tension that might be caused by banning religious items of dress (element 7). The report-ing on Sikh affairs is thus much more complex in the Guardian than in the Daily Telegraph, and focuses more heavily on controversial or negative aspects. One article that is unique in this series is entitled “Which sharply pointed objects can you legally carry?”, which points out that people charged with carrying an offensive weapon can bring the defence that it is being carried “for religious reasons”, naming the Sikh kirpan. Finally, there is also an opinion article in which a Sikh, Hardeep Singh Kohli, denounces the uniqueness of Sikhs in this re-spect: he begins “I'd like to concentrate on the fact that Sikhism is the only world religion that requires devotees to carry a dagger”, and situ-ates the position of Sikhs historically in an era when they were under threat from the Moghuls. He then reports sceptically on the pro-nouncements made by Sir Mota Singh, saying “Let me repeat that: he thinks it's OK for kids to take knives to class” and pointing to the anachronistic nature of this custom: “it’s not the Punjab in 1708”. Sikhs are also compared to their disadvantage with Muslims: “But it also feels like Sikhs in Britain remain remarkably unsophisticated in their approach to free speech. Muslims, in contrast, have had to learn the hard way.” In fact, in the Guardian reporting on Sikh affairs, relig-ion itself is constructed negatively, with remarks like “the quagmire that is religious belief”, and an emphasis on waning belief among the younger generation: “perhaps this anxiety is fuelling a sort of protec-tionism, an attempt to keep every tenet of the faith sacrosanct”.

3.2. Framing Muslims

All four newspapers carried articles about Muslim dress during the period of the study: the Daily Telegraph had 13, the Guardian 22, the Sun 14 and the Mirror 9.

In the Daily Telegraph, reporting centres on the proposed burka ban in France and Belgium, but also contains articles about other inci-dents related to the burka. The most frequently encountered framing

Ruth Breeze 288

elements here are the notion that other countries are intolerant (ele-ment 24), which was present in all the articles about continental moves to ban the burka, and the two elements which comprise the main arguments against the burka (element 1, wearing the burka con-stitutes a threat to public safety or security, and element 2, wearing the burka goes against mainstream values). It was noticeable that elements 1 and 2 were often found side by side in the same article, but no at-tempt was made to resolve which of the two could be considered the main argument, or to refine the arguments by defining exactly how this form of dress might threaten safety or values. These two elements were often, but not always, accompanied by references to people’s rights to wear religious symbols (element 3), and by warnings that a ban might cause social tension (element 7). Two arguments that were less frequently brought up were that a ban would specifically harm women (element 8), and the notion that Muslim cultures are intolerant (element 11). Although this array of ideas shows that no clear overall frame had emerged in this newspaper, it is important to point out that the vast majority of articles included references to either element 1, element 2, or both, and that these critical statements were usually bal-anced either by reference to the need for freedom of religious expres-sion (element 3), or by reference to intolerance on the European mainland (element 24).

The Guardian was the newspaper with the most extensive cov-erage of Muslim issues, and with the largest number of articles about the burka and niqab. In terms of framing, the most salient elements associated with these items of dress in the Guardian were element 24 (other European countries are intolerant), found in 14 cases, and ele-ment 2 (the burka represents a threat to our values), found in 13 arti-cles. After this, the next most frequent element was element 7 (a ban will cause tension). Interestingly, element 1 (the burka is a threat to safety or security), which was prominent in all the other newspapers, was found in only three of the Guardian articles. This aspect of the issue seems not to be particularly high on the Guardian’s agenda.

The Guardian provides a considerably more complex analysis of what the burka may signify: “not an atavistic hangover, but a very modern gesture of disaffection from and rejection of society”; “Those who have argued for a general ban on the burka and niqab have not managed to show that these garments in any way undermine democ-

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 289

racy, public safety, order or morals”; “Such bans are alien to European values”;“What I am arguing for are attitudes that allow for more nego-tiation and that accept that religious conviction should not be treated as simply opinion or the inconvenient relic of a superstitious age”. This author points to the fundamentally illiberal action of banning the veil, which is being done in the name of liberal values. Another au-thor, Thomas Hammarberg, discusses the topic in some depth, in a tone that is objective and balanced, and mainly free of emotive labels: “Some of the arguments have been clearly Islamophobic and have certainly not built bridges or encouraged dialogue”; “Those who have argued for a general ban on the burka and niqab have not managed to show that these garments in any way undermine democracy, public safety, order or morals”. He concludes that “Such bans are alien to European values. Instead, we should promote multicultural dialogue and respect for human rights”.

The Sun included 14 articles about the burka or niqab during the period of this study. In terms of framing, the most frequent elements were element 2 (wearing religious symbols poses a threat to safety), element 3 (people have the right to wear religious symbols), and ele-ment 24 (intolerance of other countries).

The French authorities come in for special criticism in the Sun.It is now “almost a crime to be a Muslim” in France. Muslim women in France are the victims of “hate-filled insults”. Elsewhere, the French authorities are again targeted for the seeming contradiction between the equality guaranteed by their constitution and their stance towards Muslims: “Sorry, but where is the equality, the égalité, in targeting a tiny group of Muslim women? Where is their liberty in not being able to choose what they want to wear? France pretends it is a bastion of equality. This shows it is anything but”. A long interview with Algerian footballer Madjid Bougherra provides ample compari-son between France and the United Kingdom, praising the “religious tolerance” found in Britain, and the fact that Muslim women can choose to wear what they like.

The Mirror provides fewer reports mentioning the issue of Muslim dress. Of the 9 articles found, most included element 2 (the burka is a threat to safety or security). Other frequent elements were 1 (the burka is a threat to values) and 24 (the intolerance of other coun-tries). The Mirror explicitly links the burka to issues related to terror-

Ruth Breeze 290

ism, but in order to draw a line and point to discrimination: “If you want to fight terrorists, then go for the men with bombs. Not the birds in Burkas”.

In general, it is noticeable that Muslim dress is generally ac-companied by elements that suggest a threat to mainstream values (element 2) or public safety (element 1), or both, in the Daily Tele-graph, the Sun and the Mirror, but that these elements do not seem to form a coherent interpretive frame, because they are usually offset by references to people’s right to self-expression and freedom of religion. The Guardian also uses these frames, but tends to embed them within discourses claiming social or political intolerance towards Muslims. Moreover, the Guardian’s reporting generally incorporates a larger number of elements to construct more complex analyses of the issue.

3.3. Framing Christians

In the Daily Telegraph, a total of 6 articles were devoted to specific cases in which Christians were banned from wearing a cross or cruci-fix. In 5 of these articles, the main framing elements were element 3 (people have the right to wear religious symbols), and element 5 (the state is engaged in the persecution of believers). A third framing ele-ment encountered in 4 articles was element 4 (different religions are being treated differently). These common framing elements appear to add up to a consistent view of the issue, which supports the individ-ual’s right to self-expression, which should be maintained for all reli-gious groups, but understands that this is being eroded by the state. However, it should be noted that there is a strong suggestion in these articles that Christians are receiving unfavourable treatment in com-parison with other groups such as Muslims and Sikhs, which suggests that state persecution of believers (element 5) is focused mainly on Christians.

The Guardian uses a very different range of framing elements in the 16 articles which describe or discuss the cases involving Chris-tians who wish to wear religious symbols at work. Here, the most frequently encountered framing element is element 6 (religious groups are provoking a conflict, present in 10 articles), followed by element 3 (people have the right to wear religious symbols) and element 4 (dif-

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 291

ferent religions are being treated differently), present in 8 and 5 arti-cles respectively. Although the elements do not seem to add up to a consistent view, the frequency of element 6 is noteworthy, since this element is not present in any of the other newspapers’ reporting, and is not present in the Guardian’s own handling of either of the other religions under scrutiny here. It is curious how the Guardian turns around the arguments about the burka in the context of Christianity:

A ban may be wrong. But Liberty's approach would mean a general right for women to be fully veiled at work, subject only to limited safeguards for safety and practicality. Employers, not just schools or the police but all organisations that want to promote equality, should be free to ban the full veil and religious symbols – at least those not clearly required by a religion.

The Guardian’s reporting frequently makes allusion to a Christian “conspiracy” to gain power which is “highly controversial” and is being greeted with “suspicion and fear”. The Guardian also includes some opinion articles which provide much more complex argumenta-tion concerning aspects of the crucifix issue. One of these argues that by campaigning as a pressure group, the Church of England has essen-tially conceded legitimacy to another body, while another recalls his-torical protestant debates over the presence of crucifixes. Here too, the Guardian’s reporting tends to greater complexity than that of the other newspapers, delving into areas of controversy which are not touched elsewhere.

The Sun provides three articles covering the issue of wearing crosses and crucifixes, all of which include the notion that people have the right to wear religious symbols (element 3), and that different re-ligions are being treated differently (element 4). Two of them also focus on the idea that the state is engaged in persecuting believers (element 5). The Mirror also gave prominence to element 3. Only one article included element 4, but this had the provocative headline “what country are we in?”, which clearly asserts priority rights for Christians over other groups.

Ruth Breeze 292

4. Analysis of voice

Table 5 shows the number of words attributed to members of three different categories: wearers of religious symbols, supporters of those who wear religious symbols, and people who are against the wearing of religious symbols. In a few cases, one person met the criteria for the first two categories, so an attempt was made in each instance to determine whether he or she was speaking personally as a wearer, or as a supporter of the right to wear this symbol in general. As will be seen, the number of words attributed to the different categories of speaker varies greatly across the four publications. However, as we shall see, the number of words is not necessarily indicative of the po-sition adopted in the article in question.

STATEMENTS BYWEARER OF RS

S. IN FAVOUR OFWEARING RS

S. AGAINST WEARING RS

TelegraphSikhs 187 407 0

Muslims 6 149 310 Christians 382 409 257

GuardianSikhs 79 160 0

Muslims 0 49 954 Christians 285 365 41

SunSikhs 0 0 0

Muslims 604 14 307 Christians 232 44 0

MirrorSikhs 0 7 0

Muslims 8 0 113 Christians 54 202 0

Table 5. Number of participants’ words quoted directly in articles.

4.1. Voice for Sikhs

In the Telegraph, voice is given to Sikh representatives, who state that “Sikhs are not arguing for British people to accept something new

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 293

– just for the country's traditions of religious freedom to be upheld andacknowledged”, as well as to Britain’s first Asian judge, Sir Mota Singh, who describes bans as “petty”, relates his own positive experi-ence of wearing turban and kirpan over 40 years, and calls for “sensi-tivity”.

The Guardian also gives voice to Sikhs, but in a very different way from the Daily Telegraph. In several articles, the Sikh spokes-man’s words are problematised: in one, he makes the reporter feel “uncomfortable”, and in another, Sir Mota Singh’s declaration in fa-vour of wearing the kirpan is glossed as “he thinks it’s ok for kids to take knives to school”. The longer article by Sikh journalist Hardeep Singh Kohli makes it clear that he sees himself as a “secular Sikh”, and questions the need for religious symbols to be worn.

4.2. Voice for Muslims

In terms of argumentation and attribution, as far as wearing the burka and the possibility of a ban are concerned, the Daily Telegraph tends to present the case neutrally, giving voice to both sides in the dispute. Opinions from the Muslim Council of Great Britain are quoted, as are the various parties to the proposals made in France and Belgium and the opinion issued by the Council of Europe. However, it is notable that this sample does not include any statements from British Muslim women, either for or against the burka. The continental spokespeople are usually referred to metonymically, as the organisation which they represent, or just as representatives, which means that the gender and religion of the speakers is often not clear. None of these speakers is specifically presented as a Muslim woman who wears the burka, and the only named female voice is that of Isabelle Praile, vice president of the Muslim Executive of Belgium, who warns that the ban will damage civil liberties.

Several of the Guardian’s articles on this issue are by Muslim women, and there is a special feature in which a Muslim woman, Mona Eltahawy, writes about why the veil should be banned, while a non-Muslim Asian woman, Stephanie Street, writes about why it should not be banned. In contrast to most of the Guardian’s reporting on this subject, Eltahawy’s article uses highly emotive discourse and

Ruth Breeze 294

many negative epithets: “I detest the niqab and the burka for their erasure of women”; “the ideologues who promote its covering are simply misogynists”; and the “bizarre political correctness” of those who allow the burka in the name of tolerance. On the other hand, Street provides balanced arguments in favour of allowing it: “in the west it is nearly always worn out of choice. It is an issue of how a person chooses to practise their faith, and in a democracy we cannot deny any human being that”; “this issue of modesty is sacrosanct”. On the other hand, the Guardian also gives extensive coverage to anti-burka statements made by politicians, but these are usually delegiti-mised by being linked to the concept of “Islamophobia”, a concept which appears frequently in the Guardian but is absent in the other three newspapers.

The Sun gives extensive coverage to the Conservative MP who likened the burka to “a paper bag” and called covering one’s face “in-timidating and offensive”. It gives his point of view against the “hypocritical” and “patronising” Northamptonshire Rights and Equal-ity Council for championing freedom of speech while attempting to have him prosecuted. The Sun also quotes a Belgian MP’s statement that: “It's also a question of human dignity. The full face veil turns a woman into a walking prison”. However, the Sun also features several articles by Muslim women, interviews with them, or both. Thus Anila Baig (a non-burka-wearing Muslim woman) interviews Kenza Drider, who is wearing the burka in defiance of the French ban. One woman states that she “felt liberated” when she put on a full face veil. Another woman, who only wears a headscarf, feels “angry” that she is labelled an extremist and “thought of as a terrorist”. In a different article, Anila Baig defends the right to wear burkas, setting out the issue as follows:

I don't understand those who choose to wear the burka. To me it represents a medieval, narrow-minded and harsh side of Islam. The problem is, I know women who choose to wear it and they are not medieval, narrow-minded or harsh. They are often intelligent, articulate and passionately believe they are serving God.

In the name of liberalism and tolerance, she concludes that “If women can choose to wear as little as they like, it is UNACCEPTABLE that they can't wear as much as they like too”. Her position is countered by

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 295

another Muslim woman, Saira Khan, who takes the position that “The burka is an imported Saudi Arabian tradition and the growing number of women veiling their faces in Britain is a sign of a creeping radicali-sation which is not just regressive but oppressive and dangerous”. Thus the Sun, like the Guardian, takes care to present the issue of the burka from the point of view of Muslim women, giving voice both to the women in favour and the women against, but with a burka-wearer expressing the former view.

Although the Mirror’s articles are the shortest in this sample, it is the Mirror which gives the longest quotation justifying the Belgian ban: “Centre-right MP Daniel Bacquelaine said: ‘The notion of recog-nising people in the street is essential to maintain public order. It's also a question of human dignity. The full-face veil turns a woman into a walking prison’”.

4.3 Voice for Christians

Both the nurse involved, Shirley Chaplin, and the chairman of the tribunal which heard the case, are quoted at length in the Daily Tele-graph, as are other commentators such as a representative of the Christian Legal Centre, six Anglican bishops who wrote to the press about the issue, and Shami Chakrabarti, the director of the human rights group Liberty. According to Chaplin, her religious beliefs were “violated”, and her superiors were trying to “humiliate” her. “This is a very bad day for Christianity [...] This is a blow not just for Christians working in hospitals but for all jobs and professions. I am not sur-prised at the result. It was one person taking on a Government”. She also explains the importance of the crucifix for her: “The crucifix is an exceptionally important expression of my faith and my belief in the Lord Jesus Christ. To deliberately remove or hide my crucifix or to treat it disrespectfully would violate my faith”. On the other hand, the chairman of the tribunal emphasises that the hospital had imposed the same rule on workers from other religions, and maintains that the damage to Chaplin is “slight”.

The Guardian quotes statements by Shirley Chaplin, and by Nadia Eweida, the two Christians who claimed to be victims of dis-crimination, as well as by their supporters and detractors. The former

Ruth Breeze 296

Archbishop of Canterbury is quoted as saying that the failure of Eweida’s case is “a sad blow”, and she has shown “courage and en-durance” which have “been an inspiration to so many of us”. How-ever, it is significant that in this particular article, the last word is given to Carla Revere, vice president of the National Secular Society, who stated:

At the moment, employers are walking on eggshells in many areas which involve religion at work. We hope that this judgment will help them feel more confident in setting their employment policies in relation to dress codes and other religious requirements.

In the Sun’s articles, Shirley Chaplin makes several lengthy direct statements, and her experience is dramatised in a first-person narra-tive, as in the following example: “She stood firm but added: ‘I was distressed and in fear of having to choose between my faith and my job’”. Despite the brevity of the reports in the Mirror, the narrative approach is similar, as in the following example: “she said: ‘I was asked to consider redeployment to a non-clinical role. I accepted it under protest for fear of losing my job. It violated my dignity as a Christian’”. These dramatisations, which are charateristic of the style of “human interest” reporting favoured by the popular press, may have the effect of encouraging reader identification. This is more notable in the Sun and Mirror than elsewhere, since only the protagonist and her supporters are cited.

5. Emotive lexis

5.1. Emotive lexis: Sikhs

Evaluative language associated with Sikhs and their religious items in the Daily Telegraph included several allusions to “colourful head-gear”, the “art” of the perfect turban, the “magnetic force” of headgear in general, the turban as a symbol of “honour and pride”. It is note-

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 297

worthy that the Kirpan is consistently referred to as a “ceremonial dagger”, and is only once described as having a “five-inch blade”.

In the Guardian, however, there is no reference to “colourful” customs. There is persistent use of inflammatory terms such as “un-ease”, “flare-up”, “row”, “furore”, “vociferous opinions”, “the free-dom to offend”, “bunker mentality”, “death threats”. The kirpan is here described as the “secreted, ceremonial dagger” or “the dagger”. On the other hand, the murdered Sikh shopkeeper was spoken of “with love and respect”, a “nice man”, “beloved by all, selfless, cheerful”. According to writer Hardeep Singh Kohli, Sikhs are “the best dancers in the world”, “defenders of freedom, guardians of religious inde-pendence, champions of tolerance”.

5.2. Emotive lexis: Muslims

Regarding lexical choices, the words associated with the burka in the Daily Telegraph have a higher emotional temperature than those which the same newspaper used to talk about Sikh affairs. The burka is a “sign of subservience”, a “symbol of subjugation”, or a “symbolic barrier”, but notably, these epithets are always presented in quotation marks. On another occasion, a burka-wearer is compared by one pro-tagonist to a “horror demon”, and a burka is a “walking prison” (quo-tation marks). A woman wearing a burka is reported to have been mistaken for a “terrorist or criminal in disguise” (no quotation marks), while the burka is a “preferred disguise of bandits”. Elsewhere, how-ever, the burka is described neutrally as a “culturally powerful piece of cloth” (no quotation marks), or a “private tent, a cloak of invisibil-ity” (no quotation marks). It is “part of religious culture” (assertion attributed to Muslims). Moreover, burka rage incidents are portrayed as violent, using descriptions such as “ripped off”, “tearing off”, “wrestling off” and “came to blows”. However, strong language is also used in the context of women being forced to wear a burka or veil: “burka bullying”, “verbally assaulted” and “crackdown on dress”.

Finally, regarding the ban, Sarkozy is described as “patronising and offensive” (in quotation marks), and the ban will lead to “resent-ment with an attendant sense of victimhood” (no quotation marks),

Ruth Breeze 298

and a “real problem” (no quotation marks) in the future. It is also “ab-surd” and “judicially unsafe”. The use of emotive vocabulary and controversial statements is frequent in Daily Telegraph reporting on the burka and niqab. Thus although the actual contents of the articles are mainly balanced, in terms of the frame elements used, the “tem-perature” of the texts is higher than was the case with the Sikhs.

The Guardian also works through a range of emotionally charged vocabulary on the topic of burkas and their possible ban. The possible ban on burkas, abroad or in the United Kingdom, is associ-ated with a wide range of negative lexis. Banning face veils is associ-ated with “bigotry”, “prejudice”, “negative attitudes and discrimina-tion”, “social vilification” and is part of a “worrying anti-Muslim trend”. A “rising tide of Islamophobia” is detected, which needs to be tackled with care. In France, Islamophobia reaches “a new pitch”. Sarkozy is said to be “playing with fire”, “pandering to racism”, and carrying out “shrill scapegoating of Muslims”. We are witnessing “a solid lump of malignity towards Muslims”, as evidenced by opinion polls, politicians’ speeches and general public opinion. A ban would be “an ill-advised invasion of individual privacy”. The issue is ex-pressed by the protagonists in combative terms: “we are determined to wage a controlled political battle against fundamentalism”.

A large proportion of the negatively-charged discourse in the Guardian centres on the figure of Sarkozy. Thus we are told that he “has continued to stigmatise France's five million-plus Muslim com-munity, galvanising all this prejudice into an ill-conceived national identity debate”, that he is trying to capture voters from Le Pen’s Front National by pursuing racist policies, or even that his policies on immigration are directly fuelling the Front National.

There are also some instances of negatively charged references to the burka or niqab. However, these are always given in quotation marks and attributed to a particular speaker, who is classified in politi-cal terms. The Guardian reports the words of a Conservative MP who says that the burka is “oppressive” and compares it to “a paper bag over your head” are reported neutrally, as is the fact that he is now being prosecuted for “inciting racial hatred”. A Belgian proponent of the anti-burka bill is quoted as saying: “Wearing the burqa in public is not compatible with an open, liberal, tolerant society”. A French communist MP is quoted as calling the burka “a walking prison” and

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 299

saying that “Behind the full veil hide scandalous practices that are contrary to our history”, while a Belgian Liberal MP is reported as saying that “Wearing the burqa in public is not compatible with an open, liberal, tolerant society”.

In the Sun, most of the emotive language is used to describe the proposed burka ban in France and Belgium. This is dramatised in graphic terms: “what are you going to do? Physically rip it off women as they walk down the street?”. However, in another article, the French ban is framed as follows: “It comes as the French parliament is set to consider a motion which describes burkas as an ‘affront to the nation's values’. The image of the burka in French society hasn't been helped by terrorists and criminals who some accuse of using the veil as a disguise”. Violent language is also used in reports on a burka-rage incident, in which a “lawyer compared the Muslim woman to a DE-MON and the face-off descended into a scrap at a French clothes store”, and the “shouting match descended into a full-blown brawl”.

On the other hand, the Sun also reports on various odd or un-pleasant burka-related incidents that are not reported in the other newspapers in this sample, such as that of a Saudi woman who beat up a religious police officer, the Australian case of a woman killed by her burka while go-karting, or the Saudi woman who appears on the local version of the X-factor wearing a burka.

In the Mirror, too, the burka ban is dramatised in emotive terms: “Women in France defying a proposed ban on burkas in public would be kicked off buses and trains”. The Belgian ban is a “spiteful little law”. In a different article, the Mirror adds emphasis to stress the absurdity of the Belgian ban: “Belgium last night agreed a complete ban on women wearing burkas. It means Muslim women face being JAILED for hiding their faces in public”.

However, it is notable that verbal humour is also used: an opin-ion article on the Belgian ban is titled “A bunch of burks”; and word play appears in the headline of the article about Conservative MP Philip Hollobone, who advocated a burka ban in Britain, which runs “You berk, Philip Hollobone”. It is interesting that the Mirror is the only newspaper in this sample which risks puns on this sensitive issue. In the Guardian, Sun and Mirror, the burka is also linked to “contro-versial” fashions, such as tattoos and piercing (Guardian), “fat, mid-

Ruth Breeze 300

dle-aged men wearing replica football shirts” (Mirror), and “people who wear socks with sandals” (Sun).

5.3. Emotive lexis: Christians

Regarding emotive lexical choices, the prohibition is described by the Daily Telegraph as “ridiculous”, “fundamentally illiberal”, having “no justifiable reason”. Christians are “persecuted” and “treated with dis-respect”, while Anglican bishops protest at “‘discrimination’ against churchgoers” which is “unacceptable in a civilised society”. Else-where, reference is made to “aggressive secularists” who want to “sweep religious faith from the public sphere”. One columnist states that people are now afraid to be Christians, and the moral of the story is that “Christians need to be as strident as Muslims”; “We should be more like Muslims, who are self confident, strident and constantly haranguing authorities if they suspect an anti-Muslim bias. No one dares mess with them”.

The Guardian also makes ample use of the term “persecuted Christians”, but here the phrase is always used in inverted commas, marked as ironic. One commentator spells out the newspaper’s atti-tude to this: “to protest about supposed persecution when the Church of England, of all religious groups in Britain, has such a privileged place in the institutions of the country is, frankly, pathetic”. Regarding other instances of emotive vocabulary, the term “religious privilege” is used three times, only in the context of Christians, but never in the context of other religions. The phrases “superior right” of Christianity and “special treatment” for Christians are also problematised, appear-ing with characteristic quotation marks to delegitimise the concept. Further delegitimation occurs by use of loaded phrases such as “secret Christian donors bankroll Tories”, and allegations that “growing” and “powerful” Christian groups are being viewed with “suspicion” and “fear”.

Regarding the Sun’s use of emotive language, Shirley Chaplin is consistently presented as “devout”, a “grandmother”, and “mum-of-two”, using the characteristic “human interest” approach to anchoring favoured by the popular press (Conboy 2001, Conboy 2003). Once she is thus identified, she is portrayed both as “courageous” and “brave”,

Reporting Public Manifestations of Religious Beliefs 301

and as “distressed” because her dignity is “violated”, in such a way that invites readers to identify with her. At the same time, the health and safety risks which were given as the reason for the ban are dis-missed as “negligible”. The tabloid’s system of emphasis using capi-tals is used here to bring out irony: “A Christian nurse told today how hospital bosses offered to let her wear her crucifix on duty - as long as it was pinned INSIDE her pocket”.

In the Mirror, the reports are much shorter and include fewer quotations. However, Chaplin is cited as saying that removing the crucifix would “violate her faith” and that this is “a bad day for Chris-tianity”. The Archbishop of Canterbury’s accusation of “wooden-headed bureaucratic silliness” is also quoted.

6. Discussion

The overall picture which emerges from this study is of considerable complexity. With a view to achieving clarity, the main results ob-tained through the three different analytical approaches will first be discussed. The relative merits of each approach will then be assessed. Finally, some conclusions will be drawn as to the way public manifes-tations of religious belief were being reported at the time of the study.

Regarding the analysis of framing elements, we may observe that although the panorama is extremely heterogeneous and no domi-nant overarching frames have yet emerged, there is a general trend in all four newspapers towards permitting people to wear items of reli-gious significance in a spirit of tolerance and freedom of expression. However, this is often placed in the context of an unresolved quan-drary: certain items of religious attire are regarded as undesirable by some groups, while other groups insist on the right to self-expression (Breeze, forthcoming). In the case of Muslims, there are allusions to “threats” posed by Muslim dress to mainstream society, either affect-ing security, or clashing with western “values”, a concept which is defined very loosely and lies open to rhetorical manipulation (Petley & Richardson 2011). It is also clear that there are major differences between the ways in which cases involving members of these three

Ruth Breeze 302