Reading Voices: Sign Language, a Mediator between Speech and Writing

Transcript of Reading Voices: Sign Language, a Mediator between Speech and Writing

DISCIPLINES

202

Chapter 17: Reading Voices: Sign Language, a

Mediator between Speech and Writing

Judie Cross Traditionally language and communication have been perceived according to a binary logic as either oral or written. This has inevitable resulted in the marginalisation of other forms, such as Sign. It is therefore the purpose of this paper to refocus mainstream attention so that sign languages, which are themselves forms of multimodal communication, can be included and as a result, more usefully perceived as mediators between speech and writing. Since research into sign languages is well developed, it is timely to reconsider the paradigms dominating thinking about language and communication, especially in this multimedia age where new forms of digital communication blur the boundaries between spoken and written language. The value of focussing on Sign as a critical mode of communication will be evidenced by a multimodal analysis and review of selected elements from the first part of Adam Hill’s videoed performance in Characterful: a bird’s eye view on how social semiotic systems can interrelate and impact on meaning.

Sign languages (such as Auslan and ASL) are visual-spatial languages. Their cinematic dimension can probably and mainly be attributed to their dynamic use of a signing space, which “extends from approximately just above the head to the waist, and in width from elbow to elbow when the arms are held loosely bent” (Brennan quoted in Johnston & Schembri 2007, 81). The embodied use of this space is capable of conveying extremely subtle differences in meaning, which are signified by sequences within and between signs as well as by movement, location and hand shape. Fully developed sign languages, as opposed to the semiotic of gesture, not only use space linguistically (lexically, grammatically and syntactically), but they also use it dynamically. Sign languages are, in fact, comparable to speech in terms of phonology, temporality and sequencing, as well as akin to writing since they can be read in much the same way as we read images or film; in other words, silently. Further, since the linguistic capabilities of signed languages are, “in every sense, as complete and sufficient as spoken and written languages” (Esmail 2011, 999), it is unfortunate that some of these

DISCIPLINES

203

need to be deposited with the Endangered Languages Archive (Arcadia 2013) and so more can yet been done as regards including sign languages in mainstream discussion of topics concerning language and communication, especially since we communicate in a multimodal environment where connections are made across communicative modes rooted in context and meanings are realized through composite structures (Johnston 2013).

Despite the fact that sign languages “are natural languages in the same sense as spoken languages seems now to be beyond any doubt” (Sandler & Lillo-Martin 2006, 3), while the structural similarity of sign and spoken languages reflects language universals, recognition of sign languages as equivalent languages and a form of standard communication has still not become mainstream (Branson & Miller 1993, 36-37; Morrisey & Way 2006). Nevertheless, people such as myself, for instance, who may not be able to sign owing to the shape and lack of functionality in their hands and fingers, could benefit greatly from participating in Sign by learning to read it.

It is argued here that it may only be possible to advance the traditional present and rather narrow understanding of what constitutes language and communication by venturing beyond a binary perspective, which looks through a lens confined to oral and written discourse. It is necessary to acknowledge, describe, analyse, interpret and synthesise each mode (such as text, image, animation and sound) that contributes to the overall meaning conveyed in everyday language and communication, which is, by and large, a combination of two or more modes and hence, multimodal. Sign languages can simplistically be described as another one of these modes, but they are even more important than this because they are fully blown languages and essentially multimodal in their structure, use and development (DCAL 2013). Giving this full recognition will give access to another layer of, or perspective on, meaning that is conveyed when a spoken language is not simply amplified by use of gesture, but simultaneously and spatially interpreted by a sign language, which uses a combination of signs, gestures and words and which can be systematically sequenced according to language internal principles.

Alexander Graham Bell, though not usually seen as a supporter of the Deaf, is quoted by Sacks (1991, 27) as saying that “no language will reach the mind like the language of signs”. Moreover, many native signers, who are often children of Deaf parents although not hearing impaired, attest to needing to resort to thinking in Sign when there is a complex intellectual problem they have to tackle (Sacks 1991, 34), while they often interpret gesture as the basis for “true meaning” (Davis 1995, p. 124). The uniqueness and richness of the Deaf perspective, evident in their proud visual language heritage, which can be seen in the many different sign languages still in active use around the world (DeafNation 2012), is a critical dimension to recognize, consider and, most importantly, include in mainstream discourse on, analysis, interpretation and evaluation of language and communication.

This inclusion of Sign in mainstream discourse is possible and, based on the evidence already collated and documented from Deaf communities, demonstrably desirable. For example, a form of hereditary deafness existed in

DISCIPLINES

204

the community of Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and, in response, both the hearing and the Deaf learned Sign:

there was free and complete intercourse between the hearing and the deaf. Indeed the deaf were scarcely seen as “deaf”, and certainly not seen as being at all “handicapped” . . . [but] often looked at as the most sagacious (Sacks 1991, 31-5).

Many people see this type of community, where everyone signs, as a utopia (Kusters 2009, 3).

Stokoe, back in the early sixties, was the first to analyze signs, proposing each sign had three independent parts: location, hand shape and movement, elements comparable to speech phonemes. He further argued each part had a “limited number of combinations” (Sacks 1991, 78); in other words, a systematic organization demonstrating a syntactic and lexical structure. However, the most significant feature of Sign is probably its “unique linguistic [and meaningful] use of space” (Sacks 1991, 88), together with its dynamic and “holding” flow of movements in time. The spatial dimension of sign languages is, according to Aronoff, Meir and Sandler (2005, 338) “uniquely suited to reflecting spatial cognitive categories and relations in a way that is iconically motivated”, whereas its temporal quality is also significant, especially when it pertains to context. As Liddell remarks: “One of the key articulatory differences between spoken and signed languages lies in the mobility and visibility of the hands” (66). Johnston and Schembri (2007, 41) also point out other unique features, which distinguish Sign from spoken language pidgins and identified by Brennan: finger spelling and mouthing. In fact, signed languages rarely use non-manual features alone to form signs (Johnston & Schembri 2007, 97) and so it can be seen there are several important and distinctive features of Sign.

Adam Hills has endorsed the value of Sign by including a signing interpreter in several of his mainstream comedy performances, such as Characterful. In Characterful, an Auslan interpreter from Queensland, Leanne Beer, signs his entire show for purposes I argue are beyond that of pure comedy. The live show has been recorded and is able to be watched, as well as read on DVD where subtitles, together with the sign interpreter in a simultaneous miniature frame, are available options. (Although this live performance can also be viewed on YouTube, this recording does not always include the sign interpreter, while the transcript is often unintelligible.)

Characterful begins with an entertaining segment where Hills introduces his interpreter, Leanne Beer, very early on in the show when the audience is informed about the very basics of Sign, as well as how to applaud a Deaf person. Hills then makes it explicit that Leanne will be signing in Auslan, incidentally explaining this is only one of the many contemporary sign languages in active use around the world. Interestingly, Hills next highlights how the audience may find themselves laughing twice during through the

DISCIPLINES

205

show: once when he tells a joke and once again as its signed translation and interpretation is demonstrated. In this manner, Hills implies it is not simply humour, but something more fascinating that can be gleaned from having his performances simultaneously translated and interpreted into Auslan: its inclusion allows another layer of, or perspective on, meaning to be added to his acted and spoken communication, which is of course already multimodal.

In order to demonstrate Sign is more than a mode, but a multimodal language essential to include and consider in mainstream language and communication discussion, I will analyze a few examples from Hills’ performance via an analytical and multimodal approach, which identifies Sign as a synthesis of text, image, movement and gesture. The extra laugh gained from the simultaneous translation and interpretation of a joke or comment into Auslan will be shown to be the result of an additional perspective gained from the unique lexical, grammatical, syntactical, spatial and/or temporal characteristics provided by the language of Sign.

Initially, I will briefly discuss how to applaud using Auslan; second, I will outline how one can heckle in Sign; next, I will compare the gesture of getting up “like an old man” with Leanne’s possibly regional translation and interpretation of it using sign language; then I will briefly consider bilingualism and accent as it arises in this performance; finally, I will touch on specific lexis such as “character” and its entertaining derivative term, “characterful”.

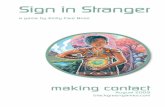

At the beginning of Characterful, Hills explains that when you applaud in Auslan, you do not clap, but raise your hands in the air, above your head, and “do this”. Written words are clearly insufficient to describe what “this” is: a dynamic, finger waving of a two-handed movement, both arms raised high, one on each side of the head, accompanied by animated and cheerful facial expression(s), and therefore, an image is helpful (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Deaf applause (musicfreak012 1:19 minutes)

DISCIPLINES

206

When a performance is highly appreciated, this hand waving and its accompanying facial expressions become more pronounced, paralleling the louder clapping engendered by great performances.

Interpreting these nuances necessitates a move beyond defining reading literacy as the decoding of written texts (Freebody 2007, iv) because:

Signed language writing systems come in two forms: glossing and notation. Glossing refers to the practice of using spoken language translations of signs, together with special symbols to represent the use of space and facial expression . . . Notation, in contrast, involves the use of special symbols to represent the physical features of signed language itself (Johnston & Schembri 2007, p. 21). Apart from this highly technical reading of signed language systems,

numerous individuals are literate in Sign without having ventured into these specialized and complex forms of transcription referred to above. Suffice it to say that a literate reading and appreciation of the Deaf applause must be witnessed rather than heard and its sincerity or intensity read rather than interpreted from its volume and length. Moreover, its import is at least equivalent to clapping, being the combined result of its iconic lexis, realized in the shape and high position of the hands and arms, its grammatical sequencing, the speed of its finger movements in time, the orientation of the head and the intensity of the facial expression(s).

Approximately two minutes into his performance of Characterful, Hills goes on to explain how members of the audience can attract Leanne’s attention and sign their “heckles” to her, so she can then communicate their import back to him. In other words, use of sign language enables a synchronous form of interactivity during the show, which would otherwise probably only be available via a form of written technology, such as tweeting or texting. Since Judy Moreo has often been quoted as saying: “Ask a heckler to identify himself and his company. They usually prefer to be anonymous”, signing a heckle will nonetheless allow anonymity to continue. It does, however, depend on an audience member having a rudimentary ability to sign; in short, an additional linguistic ability and mode of communication beyond the more ambiguous and less precise semiotic of gesture.

Admittedly, non-lexicalized pointing signs (such as ones indicating ‘I/me’ or ‘you/they/them’) in sign languages remain gestural in nature, just as these gestures do in the composite utterances of spoken languages; their difference in signed languages can probably be more appropriately described as one of “degree, not kind” (Johnston 2013) because they have been more highly systematized, glossed and annotated. Isadora Duncan, a famous American dancer at the turn of last century, has often been quoted for saying it took her years “of struggle, hard work and research to learn to make one simple gesture”. Further, she realized “it would take as many years of concentrated effort to write one simple, beautiful sentence”. She is quoted here in order to highlight what can be acknowledged as the popular or mainstream recognition

DISCIPLINES

207

accorded to the importance of gestures in context, words in sentences. It is argued this recognition indirectly implies the immense significance the various, systematic, sequential and multiple combinations of signing elements must therefore have: location, hand shape and movement of two hands in space, accompanied by body and head orientation, facial expression, mouthing and finger spelling.

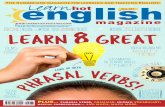

Compare, for instance, the “noise” (transcribed as “Aaargh”) Hills makes around seven minutes and forty seconds into Characterful when he gets up from sitting on the stage “like an old man”, exaggeratedly acting out the effort involved, while his interpreter Leanne simultaneously signs this act. Hills feels the need to repeat his action and amplify the original sound effects he made in order to ensure the audience actually registers what he has just done, whereas Leanne’s signing of this action and accompanying noise is much more concise (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Old man noise (musicfreak012 7:13 minutes)

The signing of both the old man movement and noise is depicted within

the upper region of the signer’s body by the awkward positioning and quick jagged movement of both hands and arms, together with a clenched and grim facial expression, adequately conveying the effort and sound effects required. The humour inherent in Hills’ movement is thus emphasized not simply by its protracted repeat performance, but also by its simultaneous silent and economic translation and interpretation into Sign.

Apart from its more economic and silent aspect, Sign is also subtle. Around eleven minutes into his performance, Hills begins to comment on the three reasons why he admires Canada: it is bilingual, it allows same sex marriage and it uses Braille on its dollar notes. In other words, Hills articulates the value he places on Canada’s mainstream acknowledgement of people with additional abilities, such as a second language or heightened sense. The humour that can be exploited from miming is demonstrated around a minute later when Leanne is required to translate and interpret Hills’ rendition of an

DISCIPLINES

208

English sentence said with a French accent. This sequence once again offers a second opportunity for the audience to laugh since it is not only the imitation of the sound of a French accent that provides amusement, but also the flow (sequence) of the body movements, combined with the accompanying head actions and facial expressions required by Auslan in order to translate and interpret Hills’ French accent uttering an English sentence accurately.

Sign is related to gesture and mime (Johnston & Schembri 2007, 24), but it is much more precise, economical and subtle because Sign is a fully-fledged systematized language; the signer can refer to past, present or future using the space around him/herself. As a consequence, it is not simply the Auslan translation and interpretation of isolated “naughty” concrete words (such as “lick it” at around nine minutes and forty seconds or “tampons” at around eighteen minutes in the recording), which Hills draws on heavily in order to enhance his show, but Hills proves there is another perspective to be gleaned from simultaneously viewing an event through a second language. He also demonstrates there is an alternative lens for appreciating language when he responds to many audience requests for Leanne to sign something for a second time because several audience members have missed seeing her original signing of it.

It is more than twenty minutes (just over half way into the recorded performance of Characterful) when Hills begins to elaborate on what he means by the more abstract term, “character”. This extended segment takes several minutes, but it is, I suggest, essential the audience simultaneously sees how this term is translated and interpreted into Auslan. Although not so clearly visible in the YouTube recording, the DVD does allow the viewer to observe the signing of this word: basically it involves Leanne moving the tips of her fingers and the palm of her right hand diagonally down towards her heart, while her other hand is placed horizontally to receive it, a gesture normally associated with integrity, truth and/or sincerity (see Figure 3).

DISCIPLINES

209

Figure 3: character (Johnston 2009 Sign 2612)

However, as a slight variation of the image for the “character” sign above, in Characterful where a derivative term is used to title the performance, Leanne signs this word a little differently: her right hand is seen by the audience from a side angle, rather than front on; the thumb reaches out and the shape of the hand is cupped, while the receiving hand is placed lower on Leanne’s body so it does not make contact with the one above. This is, nonetheless, not problematic within Auslan, nor for Australian English or for any language, since there are always recognized regional as well as individual differences. In Leanne’s case, moreover, she is not only a professional interpreter in Queensland where a slightly different dialect is used than is the case in other Australian states, but she is interpreting a term that has been coined as a deliberate variation of what is popularly understood by the term, “character”.

Language is, according to Vygotsky (Sacks 1991, p. 64): always, and at once, both social and intellectual in function [with intellect related to affect . . . and] all communication, all thought, is also emotional, reflecting “the personal needs and interests, the inclinations and impulses” of the individual .

The various parts of speech (adjective, verb and modifier), as combined in the noun, “character”, is the meaning or essence of what Hills is endeavouring to convey via his humorous stories and their synthesis in his unique coining of the term, Characterful. All of these parts of speech and their wide range of nuances can also be concisely and subtly emphasized, as well as effectively communicated, by their synchronous interpretation using signing. Signed narrative, moreover, can readily express this meaning alongside its spoken version as it is neither linear or prose-like: its essence is more akin to how an edited movie works: “the field of vision and angle of view are directed but variable” (Stokoe in Sacks 1991, 90).

This brief discussion of a few signing examples, taken from Characterful, have been selected to demonstrate the equivalence, value and additional lens that can be provided by including Sign in mainstream discourse on language and communication. Hills has found inclusion of a Sign interpreter in his shows not only allows the Deaf audience members to enjoy his material, but also provides a fascinating experience for the hearing members, some of whom now only book for signed shows (Di Fonzo 2007). In short, mainstreaming signed translations and interpretations is empowering in its provision of a valuable and an additional perspective on language and communication.

Although Australian ethnography may argue that landscape and locality are the foundations for cultural knowledge and social history, spatial orientation seems to hold the key to understanding myth, art, gesture and social life; in other words, “the spatialization of thought and language” is key to

DISCIPLINES

210

meaning (Levinson 1996, 377). Hence, rather than simply making sign languages the language of instruction for all Deaf students, the recognition of their evocative inclusion of visual-spatial signing into mainstream media needs to be attended to, covered adequately, acknowledged widely and valued; audiences do not only want more fully signed comedy shows performed by Adam Hills, but they need vital broadcasts to be fully signed, especially community information transmissions akin to the Premier’s reporting of the floods in Queensland in 2012 and 2013 where the cameramen and women did not always remember to include the Sign interpreter in the camera frame.

Space and time affect interpretation of language and communication because “communication is embodied and rooted in the context of utterance” (Johnston 2013, 60). It is therefore timely to consider the “triangulation of writing, sign and speech” (Esmail 2011, 1007). As more and more communication uses virtual and synchronous space:

we stand to advance our understanding of the phenomenon of human language by continuing to elaborate the description and analysis of [Sign] languages in each modality, without ever losing sight of the properties of mind that correspond between the two (Sandler & Lillo-Martin 2006, 493).

The whole is more than the sum of its parts. A multimodal perspective allows the reader/viewer to consider the relevance of each mode employed in a text and provides a tool whereby meaning can be synthesized though the connections made across communicative modes. By explicitly acknowledging Sign as a unique synthesis of traditional multimodal elements (text, image, animation and sound), and also a mediator between oral and written discourse, we do not simply empower its users but provide access to a more complete and deeper understanding of language and communication for the wider community.

During the London 2012 Summer Paralympics, Hills became part of the TV commentary team for UK Channel 4, for which he hosted a daily alternative review of each day's events, entitled The Last Leg with Adam Hills. With regard to his coverage of this event, Hills maintained: “If the Paralympics is covered well, it can change the way you look at and treat people with disabilities” (Gunn 2012). Mainstream recognition of Sign is not only more inclusive, but also offers a valuable additional lens for most of us regarding how we communicate and use language.

Owing to this necessarily being a relatively general and brief introduction to the benefits mainstream recognition and reading of Sign could provide, it has not touched on the extensive and current research regarding its usefulness for babies whose vocal chords have not yet been developed; nor has this paper addressed child sign language acquisition, development and its evidence-based assessment; further, the comparison of sign languages with each other or with spoken languages has not been a focus either. Finally, this paper has not even mentioned the potential benefits of Sign for marginalized

DISCIPLINES

211

communities, such as those suffering speech disorders or mental impairments. Rather, the main thrust of this chapter has been to encourage adoption of a wider lens for all when engaging in discourse on and discussion of issues relating to language and communication. References Arcadia, SOAS. n.d. Endangered Languages Archive. SOAS, London

http://elar.soas.ac.uk/search/apachesolr_search#q=auslan%3Ffilters%3D!type%3Afile.

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). 2008. Adam Hills Characterful and Joymonger (DVD). Australia: Roadshow Entertainment.

Branson, Jan, and Don Miller. 1993. “Sign Language, the Deaf and the epistemic violence of mainstreaming”. Language and Education, 7(1): 21-41.

Craig, Robert T., and Heidi L. Muller, eds. 2007. Theorizing Communication: Readings across Traditions. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi and Singapore: Sage.

Davis, Lennard. 1995. Enforcing normalcy: disability, deafness, and the body. Michigan: MPublishing, University of Michigan Library Ann Arbo.

DCAL. 2013. ESRC Deafness Cognition and Language Research Centre. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/dcal/research/themes-11-15/foundations_communication.

DeafNation. July 2012. We are Deaf (video). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BfiIMGDkzHg.

Di Fonzo, Benito. 17 May 2007. “Adam Hills: Joymonger”. The Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/news/arts-reviews/adam-hills-joymonger/2007/05/17/1178995307115.html.

Esmail, Jennifer. 2011. “I Listened With My Eyes: Writing Speech and Reading Deafness in the Fiction of Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins”. ELH, 78(4): 991-1020.

Freebody, Peter. 2007. Literacy Education in School: Research perspectives from the past, for the future. Camberweel, Victoria: ACER.

Johnston, Trevor. 2009. Auslan Signbank. Australia: Macquarie University. http://www.auslan.org.au/.

Johnston, Trevor, and Adam Schembri. 2007. Australian Sign Language (Auslan): An introduction to sign language linguistics. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Johnston, Trevor. 2013. “Degree, not kind: non-lexicalized points are symbolic indexicals regardless of whether they occur in the composite utterances of spoken languages or signed languages”. RC2013 Mode Text and Texture. Sydney: Macquarie University. http://www.annabellelukin.com/abstracts---plenary.html.

Kusters, Annelies. 2009. “Deaf Utopias? Reviewing the Sociocultural Literature on the World's ‘Martha's Vineyard Situations’”. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 15(1): 3-16.

DISCIPLINES

212

Levinson, Stephen C. 1996. “Language and Space: Reviewed Works”, Annual Review of Anthropology, 25: 353-38.

Liddell, Scott. 2003. Grammar, Gesture and Meaning in American Sign Language. New York: Cambridge Uni Press.

Morrissey, Sara and Andy Way. 2006. “Lost in Translation: the Problems of

Using Mainstream Evaluation Metrics for Sign Language Translation” SALTMIL 2006 - 5th SALTMIL Workshop on Minority Languages, 23 May 2006, Genoa, Italy. DORAS (online).http://doras.dcu.ie/15283/

musicfreak012. 2009. Adam Hills Characterful, Part 1 (online). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BtW-RtMJkwY.

Nunn, Gary. 6 September 2012. “Language, Laughter and Paralympics”.The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/mind-your-language/2012/sep/06/language-laughter-paralympics.

Sacks, Oliver. 1991. Seeing Voices. London: Pan Books Ltd. Sandler, Wendy and Diane Lillo-Martin. 2006. Sign Language and Linguistic Universals. USA: Cambridge University Press.