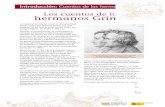

PUBLISHING On CultureBound Words in the Brothers’ Grimm Fairy Tales and Their Equivalents in

Transcript of PUBLISHING On CultureBound Words in the Brothers’ Grimm Fairy Tales and Their Equivalents in

Sociology Study ISSN 2159‐5526 December 2013, Volume 3, Number 12, 962‐973

On CultureBound Words in the Brothers’ Grimm Fairy Tales and Their Equivalents in English Translations

HansHarry Drößigera

Abstract

The aim of the article is to connect the model of cognitive metonymy with the model of types of denotative equivalence

highlighting the explanatory potential of the model of cognitive metonymy for describing and clarifying the use and

occurrence of word equivalents in the English translations of the Brothers’ Grimm fairy tales by Margaret Taylor (1914) and

Jack Zipes (1987). The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (GFT) can be seen in a wide sense as a source of the history of

culture and social life in the German speaking countries of the nineteenth century. Culture‐bound words refer to a special

cultural knowledge, which is in a historical sense not or not completely compatible with the structure of knowledge in our

present days, and refer to a common cultural knowledge of the community of German speaking countries as well. This article

describes the ways of using English equivalents in the translations of the GFT including lexical and cognitive procedures,

which stand behind the use of certain equivalents. This leads to the theoretical question: Is it possible to extend the model of

denotative equivalence using features of conceptual metonymy in rendering culture‐bound words in the target texts?

Investigating this, there can be established modifications in the theory of conceptual metonymy in the framework of cognitive

linguistics.

Keywords

Fairy tale, culture‐bound words, equivalence, German language, English language

The aim of the article is to connect the model of cognitive metonymy with the model of denotative equivalence types on word level highlighting the explanatory potential of the model of cognitive metonymy for describing and clarifying the use and occurrence of word equivalents in the English translations of the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm by Margaret Taylor (1914) and Jack Zipes (1987). Starting point of the descriptions is the complete collection of the fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm, published in German under the title “Kinder-und Hausmärchen” (Tales for Children and Home). This collection has been published since 1812 in different,

continuously revised and extended editions. For the intented research a new edition from 2010 was used, which is an unchanged edition of the version from 1857, in German called “Ausgabe letzter Hand mit den Originalanmerkungen der Brüder Grimm” (last authorized edition by the Brothers Grimm, including the original comments), containing the 200 canonized

aUniversity of Vilnius, Lithuania Correspondent Author: Hans‐Harry Drößiger, Verkiu‐st. 1‐6, LT‐08218 Vilnius, Lithuania E‐mail: [email protected]

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

Drößiger

963

fairy tales. In this way, the Complete Fairy Tales by the Brothers Grimm (GFT) is a closed corpus, representing a certain quality of its content and its linguistic features, strictlys bound to the nineteenth century. Considering this, the fairy tales can be seen in a wide sense as a source of the history of culture and social life in the German speaking countries of the nineteenth century. Both English translations have been made using the original edition from 1857, but there are differences between them. The translation by Margaret Taylor, first published in 1914 in Great Britain, is written in British English of the translator’s time. The translation by Jack Zipes, first published in 1987 in the United States, presents a more modern, but American English. In general, the two translations are complete editions of all the 200 fairy tales, following the canonized order of numbering, which makes it easy to quote the fairy tales or to refer to them.

Choosing the culture-bound words in the GFT as the subject of this article can be explained by the character of these special lexical units in the vocabulary of any language. Culture-bound words: (1) refer to a special cultural knowledge, which is in a historical sense not or not completely compatible with the knowledge of our present days; and (2) refer to a common cultural knowledge of the community of German speaking countries. Both (1) and (2) can be compared with specialized and with common cultural knowledge of other language communities of the Indo-European language family. The translations of the GFT show ways of handling of German culture-bound words. In this article, it can be demonstrated how the translators achieved a correct and appropriate understanding of the culture-bound words by choosing equivalents. Doing this, it should be possible to describe the ways of using English equivalents in the translations of the GFT and what semantic and cognitive procedures stand behind the use of certain equivalents. This leads to the theoretical question of how the model of types of equivalents

really works, and, whether it is possible to extend this model by more convenient features like semantics or conceptualizations.

THE METHODS OF THE ARTICLE

To achieve the aim of the research, the culture-bound vocabulary used in the fairy tales has to be identified by using modern and historical dictionaries of German language; among them, the onomasiological dictionary by Franz Dornseiff plays an essential role because of its ontologically referring structure to cultural knowledge in substance and scale1. By comparing the German original with the two English translations it is possible to work out if and how the culture-bound words of the original texts are rendered in the translations, according to D’hulst (2008: 224), who calls it “rendering cultural items”, and finally to inductively conclude how far the conceptual metonymy takes part in rendering of culture-bound words in the target texts. Investigating this, the theory of conceptual metonymy in the framework of cognitive linguistics can be further modified.

THEORETICAL BASIS

Fairy Tale

The fairy tale is an epic genre and can be characterized as fantastic, relieving of reality, and varying sort of storytelling. Fairy tales differ from myths by lack of the divine background, and from legends by lack of concrete historical and geographical information. The main features of fairy tales are spacelessness, timelessness, abolishing the laws of nature and the laws of causality as a natural matter of fact (e.g. transformations, talking plants, animals, and things), performance of mythical beings like giants, dwarfs, dragons (G. Schweikle and I. Schweikle 1990: 292). Nevertheless, there are certain

Sociology Study 3(12)

964

props in the fairy tales, which can often play an essential part of the plot, but these props always belong to the culture presented by the fairy tales, e.g., the culture of every day life, the culture of the society and the state, the courtly culture. In this way, the props and their names are a piece of evidence of historical authenticity, following the opinion about the fairy tales as a source of history in the fields of culture and social life (G. Schweikle and I. Schweikle 1990: 293). In this way, because of the occurrence of certain props, the GFT can be used to build up knowledge and to create an imagination about the middle ages. Many of the props, occurring in the fairy tales, are historical things of the culture the culture-bound words refer to. Furthermore, we have to consider that the GFT is an essential part of the common literary and linguistic heritage of the German language and culture community. In this sense, a large number of lexical units refer as culture-bound words to the European common cultural background.

Culture, Cultural Items, CultureBound Words

Haß-Zumkehr uses a newer, more extended understanding of the term culture, developed by Hansen2, and describes it in a wide sense, going beyond political and social aspects, and including values and orientational points of social environment as a constructive factor. Social groups not only practice cultural orientation, but also actively change and conventionalize it (Haß-Zumkehr 2001: 2).

Cavagnoli assesses in a similar way that language can be understood as a result of culture, and as a mirror and a media of culture and of cultural imaginations as well, so that in culture any schemes of behavior and any values and experiences of life are included (Cavagnoli 2005: 79-80). These “inclusions” refer to the socio-cultural background knowledge, which is essential for the shaping of a certain language and culture community. Thus, knowledge is not conceivable without culture. Moreover, knowledge transfer by language, esp. in the case of translation, is

in general always a transfer of culture3. Culture is a multiple-layer system of meaningful signs, which have to give orientation in the world. This orientation includes the essential basic values and pragmatic conventions of every day life as well (Haß-Zumkehr 2001: 15).

This means: (1) Culture brings orientation—we have to

orientate within a certain culture; (2) Cultural knowledge is conventionalized and

linguistically codified in a certain language and culture community;

(3) Culture as a mental space of knowledge consists of stable and also of interpretable components (Haß-Zumkehr 2001: 16-17).

In the sense of appropriation to things, the verbalization of the cultural background can be done in several ways: (1) by various definitions in a text (also in texts are for special purposes) or in bilingual or multilingual dictionaries for special purposes; (2) by translating a text using codified lexical equivalents; and (3) in the case of non-existing codified equivalents by creating actual, in some cases occasional, equivalents.

Assuming that such a broad understanding of culture should be used, it is possible to include not only concepts of things, activities, their characteristics, or properties, but also concepts of morality, aesthetics, intention, and usefulness as parts of a culture.

Such a broad understanding of culture leads logically to a broad understanding of the term “cultural things”, following the common definition of cultural things as culture specific items and actions (Nord 1993: 224) and as carriers of a national or ethnic identity as well (Snell-Hornby et al. 1999: 288). Thus, it seems clear that cultural things per se and de facto belong to the knowledge of a language and culture community. In this branch of knowledge, the cultural things and linguistic units referring to them are known by definition and are ready to use in monolingual communication. Because of the fact that

Drößiger

965

sometimes certain cultural things and their linguistic expressions exclusively belong to only one language and culture community, they can become a specific problem in any kind of language transfer (Drößiger 2010: 36-37).

In the case of need to handle culture-bound words, Nord suggested to practice an “explaining translation” and gave a sort of clue about the “cultural embodiment” of that culture-bound word in the source language (Nord 1993: 226).

However, from the point of view of cognitive linguistics, the presentation of a foreign language and culture community’s cultural knowledge for a target community is in focus, in order to communicate that foreign cultural knowledge, without modifying the conventionalized system of the cultural knowledge in the target community.

Notwithstanding that there are several models of classification of cultural things and their names4, it is possible, because of the simple structure of narration in fairy tales (Jens 1996: 916), to work out in an inductive way certain categories of cultural things, which correlate to the essential components of narration in the fairy tales like characters (cast), location, time, course of action, props of the characters (cast), of location and actions.

Using the term culture-bound words, it is possible to combine points of view of linguistics and translation theories. In several schools of linguistics and of translation theory, there are the following variants of this term in use: “foreign words” (H. Paul, W. Schmidt), “borrowings” (W. Schmidt), “exotic name” (T. Schippan, H. Glück), “typical cultural things of a country” (W. Fleischer), “exotisms” (Ch. Römer / B. Matzke), “culture-bound words” (E. Riesel, Ch. Nord)5. The term culture-bound word should be used in a common sense without the aspect of “unfamiliarity” (or “strangeness”), which is often used in lexicology or in stylistics. Doing this, the term and its understanding can be connected to the genealogic linguistics to highlight the similarities rather than the

differences between the Indo-European language and culture communities.

Types of Equivalence and Sorts of Metonymy

The system of types of denotative equivalence is created by Koller (2011: 230-243) grounds in relations between lexical units from two languages (Koller 2011: 230), and thus it is useful to work with it when handling culture-bound words. A sort of analogy (or mapping) can be stated between these types of equivalence and the sorts of metonymy to draw the conclusion that the potentials of cognitive metonymy (the mental space of contiguity) are very helpful in creating equivalents to words of a source language in a target language. Table 1 illustrates that analogy.

The uniqueness of certain cultural items and their names within one and only one language and culture community forces the translator to look for ways to handle culture-bound words in an appropriate way to things and to the addressee (Drößiger 2011: 7-8; Drößiger 2012: 8-9). This way of handling includes the potentials of metonymy, because the above-mentioned singled-out procedures of equivalence do not completely allow to theoretically depict all metonymical ways of handling, used in translated texts. The reason of this grounds in the nature of metonymy, because of the fact that metonymy (resp. contiguity) is also a process, which is a means for the speaker/writer to creatively modify the given knowledge (Drößiger 2007: 175).

However, sometimes the translator overshoots, which means that he/she pushes the metonymical shift within the space of contiguity too far, destroying the balance between the appropriation to things and to the addressee. This leads to phenomena beyond reasonable metonymical shifts (see the paragraph below about the metonymical distortion).

Sociology Study 3(12)

966

Table 1. Types of Equivalence and Sorts of Metonymy Type of equivalence (by Koller) Sorts of metonymy/Movements in the space of contiguity

One‐to‐one‐equivalent No metonymy possible or needed, because in source language and in target language we can find semantically equivalent units, including connotations and pragmatic markers, e.g., germ. Wicht > engl. wretch/scoundrel.6

One‐to‐many‐equivalent

In the target language several lexical units of the same space of contiguity can be used, while in the source language only one unit is in use, e.g., germ. Frau > engl. woman (basic meaning, opposite to man), wife (married woman), housewife (hostess), mistress (form of address).

Many‐to‐one‐equivalent A number of lexical units of the source language represent a certain part of the space of contiguity, while in the target language a hyperonym is used, e.g., germ. Kammer, Stube, Zimmer > engl. room.

One‐to‐zero‐equivalent

For a lexical unit of the source language an equivalent does not exist in the target language, but in the target language other procedures of naming can be used to refer to the meaning of the unit of the source language, e.g., in GFT 68 germ. Lehrgeld > engl. money for my services (Zipes); in GFT 156 germ. Polterabend > engl. the night before the wedding there was a party (Zipes). Some of the rendered units in English are occasional equivalent word combinations like in GFT 163 germ. Lappen > engl. bits of coloured stuff (Taylor).

One‐to‐part‐equivalent For a lexical unit of the source language a certain lexical unit of the target language can be used, but this unit refers only to a part of the meaning of the source language unit. In these cases the metonymical relation of WHOLE‐PART can be stated, e.g., germ. Treppe > engl. steps.

Note: Source: Author of the article.

CULTUREBOUND WORDS IN THE GFT: BETWEEN EQUIVALENCE AND METONYMY

The knowledge about the basis of every day life in social communities, the knowledge about the cultural, economic, intellectual, and social potentials of nature, the knowledge about the ways of mastering the existence while doing work and spiritual activities, can be expressed in language specific lexical items, but is in general a shared knowledge well known in large geographic regions. In this way, it can be asserted that every Indo-European language and culture community has created and developed—in a historical sense—its own vocabulary to name the common components of cultural background knowledge.

Full Equivalence—No Metonymy at All

Looking at the translations of the GFT into English and comparing them with the German originals, the hypothesis can be stated that both German and English languages have their own basic lexical items to name the things and objects of the common cultural background. These basic lexical items, consisting of

only one word stem, do not ground in a common Indo-European basic vocabulary they would come from. In every single Indo-European language we can find separately existing language specific word stems and basic items of the vocabulary, fulfilling the only function to refer to the common cultural background. In other words, no phonetic or phonological similarities can be found between these basic lexical items, not even in historical perspective. The results are completely equivalent lexical items, which can be easily used in translations from one language into another, because these completely equivalent lexical items are appropriate to things and to the addressee as well (see Table 2).

Some items in both German and English are of common Germanic origin, which can be easily stated in their phonetic and phonological form, and can be confirmed by information in monolingual dictionaries (see Table 3).

In addition, in both German and English there are items, which are borrowings from older Indo-European languages, so we can call them commonly shared Indo-European vocabulary (see Table 4).

Drößiger

967

Table 2. Completely Equivalent Culture‐bound Words German English German English Glocke bell Lumpen, Lappen rags Zwirn thread Besen broom Hof yard Jagd hunt Stiefel boot Boden loft freien to woo Hosen trousers Krug jug Klinke latch Note: Source: Author of the article.

Table 3. Words of Common Germanic Origin German English Gürtel girdle Herde herd Sack sack Brut brood Mähre mare Kresse cress Braut bride Note: Source: Author of the article.

Table 4. Indo‐European Vocabulary German English Kammer chamber Kessel kettle Krone crown Pfeife pipe Tochter daughter Tür door Zucker sugar Note: Source: Author of the article.

Only younger German culture-bound words, created in the middle ages or later, esp. generated by rules of word formation in the case of compound words, cause problems during translation. These problems can be solved if equivalent things or objects in the target culture, reflecting common features in cultural development (trades, forms of reign, things in every day life, construction, means of transport etc.) can be found in each language and culture community. To illustrate that, see the following GFT examples from the field of clothing (Table 5).

It is important to note that there is in the case of Bratenrock7 a lack of semantic features in the English

translation, because the English lexical items refer to “coat” in a very common, more neutral sense.

Metonymical Equivalence—Movements in the Space of Contiguity

The English translations of the GFT show that the meaning of the German culture-bound words is not always exactly rendered as full equivalent (apart from cases of wrong lexical items or missing words in the translations). This should be called metonymic equivalence, which occurs in certain cases of used English words, and is accompanied by a loss of cultural knowledge of the source language. The

Sociology Study 3(12)

968

Table 5. English Equivalents to German Compounded Words German (GFT #) English: Taylor English: Zipes Kaufmannskleider (6) dress of a merchant clothes of a merchant Pelzrock (13) dress of fur fur coat Holzschuh (21) wooden shoe wooden shoe Rockfalten (37) folds of the coat pleat of the coat Schnürriemen (53) stay‐laces staylaces Schäferrock (92) shepherd’s coat shepherd’s coat Bratenrock (114) company coat frock coat Note: Source: Author of the article.

Table 6. Metonymical Shift German (GFT #) English: Taylor English: Zipes Wanst (5) stomach belly Schlafgemach (62) bedroom bedroom Backofen (15) oven oven Pforte (35, 69, 167, 178) door gate Bratwurst (23) sausage sausage Note: Source: Author of the article.

occurring items are appropriate to the addressee, but not to the things. This metonymic equivalence can be divided into the following sorts.

Metonymical shift. This sort of metonymic equivalence occurs, for example, in germ. Bratenrock and the chosen equivalents in the English translations, because, instead of the more precise name with all its connotations, the translators have chosen a more common and more neutral name as a sort of hyperonym to refer to this special piece of clothing: company coat (Taylor), frock coat (Zipes).

By using hyperonyms in the English translations, a loss of connotations can be stated (e.g. the pejoration in the case of germ. Wanst) or a loss of certain references to very specific sorts of objects generated by the first immediate constituent in German compounded words. This sort of metonymical equivalence should be called metonymic shift, in which hyperonyms from the space of contiguity, which surrounds the original word, are used. Some more examples in the English translations of the GFT8 are in the Table 6.

Metonymical twist. The second sort of metonymic equivalence should be called metonymical twist. It includes the phenomena of movements in the space of contiguity described in the traditional theory on metonymy, like: OBJECT–ACTIVITY WITH AN OBJECT, CAUSE–EFFECT, WHOLE–OBJECTIVE FEATURES/PART

OF THE WHOLE and some more. The given examples, mostly as individual cases

from the GFT and their equivalents in the English translations, represent this metonymical twist, but sometimes it seems impossible to reconstruct or to explain the reason why the translator decided to use this sort of metonymical equivalence.

GFT 1: germ. “(...) so nahm sie eine goldene Kugel, warf sie in die Höhe und fieng sie wieder; und das war ihr liebstes Spielwerk”9 > engl. “(...) she would take her golden ball, throw it into the air, and catch it. More than anything else she loved playing with this ball”. (Zipes)—The metonymical twist occurs between OBJECT–ACTIVITY WITH AN OBJECT, because to play/playing are verb forms corresponding to the German verb spielen.

Drößiger

969

GFT 136: germ. “Und als sie an der Hochzeitstafel saßen (...)” > engl. “And as they were sitting at the marriage-feast (...)” (Taylor)—The metonymical twist occurs in the relation between OBJECT IN THE

EVENT–EVENT. GFT 180: germ. “(...) wer sollte (...) schmieden,

weben, zimmern, bauen, (...) schneiden und nähen?” > engl. “Who should be blacksmiths, weavers, carpenters, masons (...), tailors (...)?” (Taylor); “Who would be the blacksmiths, weavers, carpenters, bricklayers (...), and tailors?” (Zipes)—The metonymical twist occurs in the relation between ACTIVITY OF A PERSON (PROFESSION)–PERSON

(PROFESSIONAL). GFT 6: germ. “(...) das Feuergewehr, das in den

Halftern stecken muss, heraus nimmt (...)” > engl. “(...) and takes out the pistol which must be in its holster (...)” (Taylor); “(...) takes out the gun that’s bound to be in the saddle holster (...)” (Zipes).—In this case, the metonymical twist was made by moving from one co-hyponym to another co-hyponym belonging to the same hyperonym firearm10.

GFT 93: germ. “Und wie die Zeit kam, wo die Leute Lichter anstecken, sah er eins schimmern (...)” > engl. “And at the time when people light the candles, he saw one glimmering (...)” (Taylor); “When the hour came for people to light their lamps, he saw a light glimmering (...)” (Zipes)—The metonymical twist occurs between the TRAIT–CARRIER OF THE TRAIT.

Metonymical distortion. The third sort of metonymical equivalence should be called metonymical distortion, occurring whenever the movement in the space of contiguity was driven so far that essential semantic components of the original German lexical unit were eliminated. This causes a deletion of the appropriation to things, so that knowledge from the source culture cannot be provided into the target culture. Consequences are misunderstandings and misinterpretations. The translator’s decision choosing such distorting items

seems to be opaque, since truly equivalents exist in English as the target language. Some examples:

GFT 25: germ. “Ein Mann hatte sieben Söhne und immer noch kein Töchterchen, so sehr er sich’s auch wünschte; endlich gab ihm seine Frau wieder gute Hoffnung zu einem Kinde, und wie’s zur Welt kam war’s auch ein Mädchen. Die Freude war groß, aber das Kind war schmächtig und klein, und sollte wegen seiner Schwachheit die Nottaufe haben.” > engl. “There was once a man who had seven sons, and still he had no daughter, however much he wished for one. At length his wife again gave him hope of a child, and when it came into the world it was a girl. The joy was great, but the child was sickly and small, and had to be privately baptised on account of its weakness.” (Taylor)–Choosing the word combination to be privately baptised, essential components of the original meaning are deleted; a truly equivalent should be emergency baptism because of the extraordinary situation after a child’s birth when it seems that there is no time left to organise a regular baptism11.

The germ. Jungfrau (“virgin”, “maiden”) occurs in several fairy tales, but in GFT 65 and GFT 67 it was rendered by Zipes as woman (or in the plural form women). This is a case of distortion because of the loss of both semantic and cultural essential features, e.g., “virginity” and “unmarried status”. Furthermore, Zipes used other units for germ. Jungfrau, which also can be described as distortions: in GFT 92 princess and in GFT 198 maid. In all other cases, Zipes rendered the German lexical unit Jungfrau in a correct way—as maiden or virgin12.

Zero Equivalence—Incorporation of Foreign Words

Communicating cultural knowledge of a source language and culture community in a target community can often be performed by direct adoption of certain lexical units, if no equivalents as described above exist in the target language and culture. Nord says that “(...) adoptions often are the only way to

Sociology Study 3(12)

970

ensure that a translation ‘works’ in the target-culture situation it is produced for” (Nord 1994: 65). In the English translations of the GFT occur several germanisms, which were put into the text without any syntactic or semantic connections like explanation, paraphrase, footnotes, etc. Especially in the category of “Measure/Quantities/Coins”, which is in most cases definitely bound to only one culture, the culture-bound words occur as morphologically and phonetically-phonologically incorporated foreign words (see Table 7).

On the other hand, there is no stringent handling in the field of “Coins”, because not all German names of coins were adopted—the word Taler > thaler, taler seems to be an exception, due to its well-known status. Such a name for coins like germ. Batzen (GFT 15) was rendered as an appropriation to the addressee, because for native English speakers the item pennies (Taylor) is an analogue and a more natural item. In his translation, Zipes used a metonymical shift to render the original name by choosing the hyperonym coins. In the case of germ. Scheidemünze (GFT 7), both Taylor and Zipes used the metonymical shift to render the original name as a hyperonym, juxtaposed with a defining feature of the value of this sort of coins: small coins.

A specific case is the handling of germ. Heller, occurring in several GFT. A short overview of the different ways the name of this coin was used in the two English translations (see Table 8).

Only Zipes used the way of direct adoption, but in only two cases (GFT 4, 83). The dominating equivalent is farthing, with one exception in Taylor’s translation (GFT 78), and in three texts in Zipes’ translation (GFT 99, 110, 115). Because of its value, the English word farthing can be seen as an analogue item in language and culture to the German Heller. Another interesting case is the handling, resulting in English as halfpence (GFT 78, Taylor). According to Oxford Online Dictionary13, a contradiction between the value of a farthing (a quarter of a penny), Taylor’s

choice of halfpence, and Zipes’ choice of penny in three GFT can be stated, but with respect to the basic idea of translation, it is important to say that the translators’ work grounds in an appropriation to the addressee, making clear the low value of the coin. At last, in Zipes’ translation of GFT 84, again, the way of using metonymical shift by choosing the hyperonym coin can be stated.

CONCLUSIONS

The research involving recording and describing the culture-bound words in the GFT is a contribution to a better understanding of certain details in the fairy tales, it is also a contribution to the reconstruction of knowledge structures that reside with the fairy tales. The analysis of the culture-bound words in the GFT and their translations provides a possibility to get a deeper insight into social and cultural environment when the fairy tales were told, written down, and published. It also enables readers and listeners to compare it with the recent knowledge about every day life, social relations and community. In this sense, it seems important to talk about fairy tales as a source of the history of social and cultural life. As prerequisites, a broad understanding of culture and a broad definition of cultural things and their names as well should be starting points. This requires a thorough analysis of the GFT, focusing on the culture-bound words, which refer not only to cultural things differing from the modern life, but also to the culture-bound words referring to the basics of the common, in main parts, similar European culture that nations share. Toury calls this “introducing”, because:

(...) translation is basically designed to fulfill (...) the needs of the culture which would eventually host it. It does so by introducing into that culture a version of something which has already been in existence in another culture, making use of a different language, which—for one reason or another—is deemed worthy of introduction into it. (Toury 1995: 166)

Drößiger

971

Table 7. Borrowings of Foreign Words in English German English: Taylor English: Zipes Taler thaler taler Groschen groschen groschen Kreuzer kreuzer kreuzer Note: Source: Author of the article.

Table 8. Ways of Rendering of Germ. Heller Number of the GFT English: Taylor English: Zipes 4 farthing heller 71 farthing penny 78 halfpence penny 83 farthing heller 84 farthing coin 99 farthing farthing 110 farthing farthing 115 farthing farthing 154 farthing penny Note: Source: Author of the article.

Continuing this idea, he emphasizes: “The introduced entity itself, the way it is incorporated into the recipient culture, is never completely new, never alien to that culture on all possible accords” (Toury 1995: 166).

With regard to linguistics, it is appropriate to combine a vocabulary-based model of equivalence, as Koller worked out, with the ideas about metonymy in the terms of cognitive linguistics. The aim of this combination is a better recording and a more detailed description of ways how to handle certain parts of the vocabulary when performing translations. Following this idea of combination, changes in the theory can be stated, for example: a model of equivalence, created in the framework of translation theory and focusing on lexical items, can be limited to a model of only three types of equivalence: (1) full equivalence; (2) metonymical equivalence, represented by several sorts of movements in the space of contiguity; and (3) zero equivalence, which probably forces to adopt foreign lexical units.

As far as the cognitive linguistics is concerned in

the special field of cognitive metonymy, reviews and changes can be probably seen, because the distinction among metonymical shifts, twists, and distortions shows that processes in the mental space of contiguity have to be explored in a more detailed manner in order to get a better understanding of the processes, which occur in the human mind.

Notes

1. Following the systematics in Dornseiff’s dictionary, the ontological branches 2 “Life”, 4 “Size, Number, Quantity”, 8 “Location and Change of Location”, 11 “Thinking”, 14 “Arts and Culture”, 15 “Living Together”, 16 “Food and Drink”, 18 “Society”, 19 “Tools, Equipment, Technology”, 20 “Economics, Finances”, 21 “Law, Ethics”, 22 “Religion, Supernatural Things” have to be considered. 2. Bibliographical information about Hansen cf. Haß-Zumkehr (2001). 3. Dornseiff (1964: 305-306) called this “rendering of culture” as a “gratifying enrichment of the conventionalised knowledge” of a target language. 4. One of these models was created by Vlachov/Florin (2009: 49-72). But due to the limited space of this article, this model can only be mentioned. Other types of systematic presentations

Sociology Study 3(12)

972

of the vocabulary can be used, like the onomasiological dictionary by Dornseiff for German language. 5. More detailled explanations about the terms used in several branches of linguistics and translation theory cf. in Drößiger (2010: 36-52). The most of the terms came from German sources, but it is possible that in English sources similar differences of naming the same subject can be found as well. 6. All examples from GFT (German original and English translations). 7. A “Bratenrock” is a clothing worn by men at formal occasions, esp. in the nineteenth century. By DUW, the term Bratenrock includes the features “outdated” and “facetious”/“jesting”/“ironic”. 8. Some of these examples are only individual cases, but thereby they are of special interest for the distinction of sorts of metonymical equivalence. On the other hand, both Taylor and Zipes used in GFT 24 the equivalent baker’s oven to achieve a more authentic equivalence to the original, because baking was in the middle ages a more professional work of a baker in a bakery, but less an everyday work at home. 9. The orthography of the original German edition does not match the rules of orthography of modern German. Highlighting of the items of interest by the author of the article. 10. In the Oxford Online Dictionary about firearm can be found: “(...) a rifle, pistol, or other portable gun.” (http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/american_english/firearm?q=firearm) [11-18-2013]. 11. Cf. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergency_baptism [11- 28-2013]. 12. Cf. GFT 57, 60, 69, 76, 97, 111, 121, 122, 134, 165, 166, 197. 13. Cf. URL: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition /english/farthing?q=farthing [11-18-2013].

References

Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Retrieved (http://dictionary.cambridge.org/).

Cavagnoli, S. 2005. “Vom Paradigma zur Umsetzung: Das Bozner Modell (From Paradigm to Realization: The Bolzano Model).” Pp. 77-89 in Wissenstransfer durch Sprache als gesellschaftliches Problem (Transfer of Knowledge by Language as a Problem of Community), edited by G. Antos and S. Wichter. Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang.

D’hulst, L. 2008. “Cultural Translation. A Problematic Concept?” Pp. 221-232 in Beyond Descriptive Translation Studies. Investigations in Homage to Gideon Toury, edited by A. Pym, M. Shlesinger, and D. Simeoni. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Dornseiff, F. 1964. Sprache und Sprechender (Language and

Speaker). Edited by J. Werner. Leipzig: Koehler & Amelang.

——. 2004. Der Deutsche Wortschatz nach Sachgruppen (The German Vocabulary Sorted by Topics). 8th, completely revised edition. Edited by U. Quasthoff. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.

Drößiger, H. H. 2004. “Bemerkungen zur kommunikativen und kognitiven Charakteristik der Metonymie im Deutschen (Remarks on Communicative and Cognitive Characteristics of Metonymy in German).” Kalbų Studijos/Studies About Languages 5:30-40.

——. 2007. Metaphorik und Metonymie im Deutschen. Untersuchungen zum Diskurspotenzial Semantisch-kognitiver Räume (Metaphor and Metonymy in German. Investigations Into Discourse Potentials of Semantic-Cognitive Spaces). Hamburg: Dr. Kovač.

——. 2010. “Zum Begriff und zu Problemen der Realien und ihrer Bezeichnungen (On Term and Problems of Culture-specific Items and Their Linguistic Expressions).” Vertimo Studijos (Translation Studies) 3:36-52.

——. 2011. “Terminologie in Theorie und Praxis unter dem besonderen Aspekt der interkulturellen Kommunikation (Terminology in Theory and Practice From the Point of View of Intercultural Communication).” Inostrannye Yazyki v Vysshey Shkole (Foreign Languages in Higher Education) 2(17):5-13.

——. 2012. “Realien, ihre Bezeichnungen und Aspekte der Interkulturalität (Culture-specific Items, Their Linguistic Expressions and Aspects of Interculturalism).” Kalbų studijos/Studies about Languages 20:5-11.

Duden. 2005. Das Herkunftswörterbuch (Duden’s Etymological Dictionary). 3rd ed. Mannheim: Bibliographisches Institut & F. A. Brockhaus AG. [CD-ROM].

——. 2006. Deutsches Universalwörterbuch (Duden’s Universal Dictionary of German). 6th ed. Mannheim: Bibliographisches Institut & F. A. Brockhaus AG. [CD-ROM] [= DUW].

Duden-Oxford. 1999. Großwörterbuch Deutsch-Englisch; Englisch-Deutsch (The Oxford-Duden German Dictionary. German-English—English-German). Oxford University Press and Bibliographisches Institut & F. A. Brockhaus AG. [CD-ROM]

Grimm, J. and W. Grimm. 1998-2004. Deutsches Wörterbuch. (The German Dictionary) Retrieved (http://www.dwb.uni-trier.de/).

——. 2009. The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Trans. M. Taylor. Ware: Wordsworth Library Collection.

——. 2010. Kinder-und Hausmärchen. Ausgabe Letzter Hand mit den Originalanmerkungen der Brüder Grimm. Mit einem Anhang sämtlicher, nicht in allen Auflagen

Drößiger

973

veröffentlichter Märchen und Herkunftsnachweisen hrsg. von Heinz Rölleke (Fairy Tales for Children and Home). Vol.3. (Last authorized edition by the Brothers Grimm, including the original comments. With an appendix containing fairy tales not published in all editions and proof of origin of all fairy tales. Edited by Heinz Rölleke). Stuttgart: Reclam.

Haß-Zumkehr, U. 2001. Deutsche Wörterbücher—Brennpunkt von Sprach-und Kulturgeschichte (German Dictionaries—Focus of History of Language and Culture). Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.

Jens, W., ed. 1996. Kindlers neues Literatur-Lexikon (Kindler’s New Encyclopedia of Literature). Vol. 6. München: Kindler.

Koller, W. 2011. Einführung in die Übersetzungswissenschaft. (Introduction Into Translation Science). 8th ed. Tübingen: Francke.

Nord, C. 1993. Einführung in das Funktionale Übersetzen. (Introduction Into Functional Translation). Tübingen, Basel: Francke.

——. 1994. “Translation as a Process of Linguistic and Cultural Adaption.” Pp. 59-67 in Teaching Translation and Interpreting 2: Insights, Aims, Visions. Papers from the Second Language International Conference Elsinore, June 4-6, 1993, Denmark. Edited by C. Dollerup, and A.

Lindegaard. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: Benjamins. Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved

(http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/). Schweikle, G. and I. Schweikle, eds. 1990. Metzler Literatur

Lexikon (Metzler’s Encyclopedia of Literature). 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Metzler.

Snell-Hornby, M., H. G. Hönig, P. Kußmaul, and P. A. Schmitt, eds. 1999. Handbuch Translation (Handbook of Translation). 2nd ed. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

Zipes, J. (Translated and With an Introduction). 2003. The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. New York, Toronto, London, Sydney, Auckland: Bantam Books.

Toury, G. 1995. Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Vlachov, S. I. and S. P. Florin. 2009. Neperevodimoye v Perevode (The Untranslatable in Translations). Moscow: R. Valent.

Bio

Hans-Harry Drößiger, Ph.D. and habilitated doctor, university professor, faculty of the Humanities in Kaunas, University of Vilnius, Lithuania; research fields: cognitive linguistics, translation and intercultural studies.