Protecting Chinese Investment under BITs and ICSID Arbitration

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Protecting Chinese Investment under BITs and ICSID Arbitration

1

Protecting Chinese Investment under BITs and

ICSID Arbitration

Author: Yuxin Fan

ANR: 616895

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. E.P.M. Vermeulen

Jing Li Mphil

Program: LLM International Business Law

2

Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3

Chapter I China BITs Regime ......................................................................................................................... 7

1.1 Overviews of BITs ................................................................................................................................ 7

1.2 Chinese BITs regime ............................................................................................................................ 8

1.3 Clause analysis of China BITs – from vertical and horizontal perspective ......................................... 10

1.3.1 Preamble .................................................................................................................................... 10

1.3.2 Definitions .................................................................................................................................. 11

1.3.3 Fair and equitable treatment ..................................................................................................... 15

1.3.4 Most favored nation treatment ................................................................................................. 15

1.3.5 Expropriation .............................................................................................................................. 16

1.3.6 Umbrella clause .......................................................................................................................... 18

1.3.7 Compensation for damages and losses ...................................................................................... 19

1.4 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................... 20

Chapter II Dispute Resolution and ICSID Arbitration .................................................................................. 20

2.1 Overview of dispute resolution mechanism in China first and second generation BITs ................... 20

2.2 ICSID arbitration ................................................................................................................................ 22

2.2.1 Access to international arbitration ............................................................................................ 22

2.2.2 ICSID and ICSID Convention ....................................................................................................... 23

Jurisdiction of ICSID ............................................................................................................................. 24

Arbitration mechanism ....................................................................................................................... 30

2.2.3 The Ping an case ............................................................................................................................. 32

Chapter III Protecting Chinese investment under BITs regime ................................................................... 35

3.1 Chinese investors and ICSID arbitration ............................................................................................ 35

3.2 Business restructuring ....................................................................................................................... 38

3.2.1 Timing of corporate restructuring .............................................................................................. 39

3.2.2 Denial of benefits ....................................................................................................................... 41

3.2.3 Restructuring in good faith ........................................................................................................ 42

3.3 What Chinese investors and government shall do? .......................................................................... 43

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 45

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................ 46

3

Introduction

Background of Chinese overseas investment and BITs In 1999, China launched Go Aboard Policy aiming to encourage Chinese individuals and enterprises to

invest overseas. By the end of 2013, China’s GDP was the second largest only behind the United States in

the world with total amount of USD 9.240 trillion.1 In light of continuously strong performance of economy

and foregoing Policy, Chinese overseas investments, by means of foreign direct investment (FDI), have

been booming in the past three decades. By the end of 2012, China ranked the third among the countries

that made the most FDI in the world, with total amount of stock FDI of USD 531.94 billion, and approximate

16,000 Chinese investors established 22,000 companies or enterprises in 179 countries and regions all

over the world.2 It is also expected that Chinese overseas investment will continue to grow.

However, impressive Chinese overseas investments have given rise to investment disputes against the host

state when it comes to inappropriate expropriation of investments, unfair treatment or wars in the host

state. For instance, during Libya Civil War from February to October in 2011 Chinese enterprises incurred

tremendous losses in existing investments as well as the business opportunities. In Myanmar, Myitsone

Dam Project, as a BOT project, was approved by Myanmar government in March 2009 when China and

Myanmar concluded The Framework Agreement on Cooperation in Developing Hydroelectric Resources in

Myanmar, and also obtained all necessary approvals from Myanmar government before construction.

Myitsone Dam Project was financed and led by China Power Investment Corporation. In September 2011,

Myanmar government unilaterally suspended the undergoing Myitsone Dam Project due to its domestic

political pressure arising from the local inhabitants, resulting in huge damages to Chinese investor. 3

The examples abovementioned show that it is necessary for Chinese government to adopt all means of

protection mechanisms to protect Chinese overseas investments. In addition to the efforts made through

consultation and diplomatic channel, Chinese government has always endeavored to conclude bilateral

investment treaties (BITs) with other countries aiming to utilize the BITs and in which the dispute resolution

approach is included, to protect the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese international investments

from expropriation or other hazard treatments by the host states. Until June 2014, China has concluded

1 World Bank, World Development Indicators Databases, Total GDP 2013, available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD/countries/CN?display=graph . 2 Ministry of Commerce of People's Republic of China, Guideline on Investment and Cooperation in Foreign Countries and Regions(2013), available at : http://fec.mofcom.gov.cn/gbzn/gobiezhinan.shtml . 3 Report on Development and Cooperation of China's Outward Investment and Economic Cooperation, 2011-2012, 100.

4

130 BITs all around the world,4 majority of which are in force at present. It is convincing to conclude that

China has established an integrated BITs regime covering most countries in the world. Compared to

impressive amount of BITs concluded by Chinese government, the dispute resolution approach stipulated

in BITs, however, has been seldom directly invoked by Chinese investors to claim against the host states

for compensation when their investments and legitimate rights and interests have been expropriated,

impaired by the host states or other entities due to host states’ failure of fulfilled performance of their

obligations contemplated in such BITs. Similarly, there are only two BIT-based cases in which Chinese

government acts as a respondent regarding the disputes arising out of or in connection with the

transnational investments.

The reasons for the gap abovementioned come from several perspectives. Firstly, Chinese investors have

not been aware of the function of the BITs and the dispute resolution included in. Historically, they used

to rely on Chinese government to settle the dispute on behalf of them through diplomatic channels.

Secondly, investors as well as the practitioners may find it difficult to apply the incumbent BITs regime to

settle investment disputes against the host states due to the inherent drawbacks existing in the BITs and

also the reservations in the some international conventions made by Chinese government when ratifying

them. Thirdly, dispute resolution, namely, arbitration or conciliation before ICSID, other arbitration bodies

or ad hoc tribunals, is still a new approach to settle the disputes for Chinese investors even for domestic

Chinese practitioners. It can be foreseeable that the disputes will increase with the climbing amount of

investments in different jurisdictions. Therefore, the BITs concluded by Chinese government and the

dispute resolution included in need to be reviewed and adjusted in order to provide both procedural and

substantive protections towards Chinese overseas investments.

Research questions

In light of the background abovementioned regarding Chinese overseas investments and China BITs, for

my thesis, I would like to discuss the protection mechanism for Chinese overseas investments under China

BITs regime to bridge the gap between increasing transnational investments and insufficient protection

mechanism.

In order to provide optimal protection for Chinese overseas investments, it is necessary to analyze the BITs

that have been concluded by Chinese government to find the inherent problems in the contexts of these

BITs which may actually block the claims of Chinese investors against the host states and also discuss the

4 See UNCTAD IIA Database, available at: http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/IIA .

5

recent evolutions in BITs, especially the new developments of dispute resolution mechanism. In order to

analyze these problems, a comparison between Chinese BITs and BITs concluded by other countries, for

example Dutch Model BIT and American Model BIT, will definitely enlighten investors in term of the

understanding of identification of aforesaid problems, thereby making it easy to answer the research

question so as to the mechanism that shall be embodied in the Chinese BITs to improve its applicability.

With respect to the dispute resolution mechanism, both procedural and substantive issues need to be

taken into account for the purpose of analyzing the gap aforesaid. It is widely accepted that arbitration

initiated by investors directly against the host state before ICSID has been an effective method to settle

the investment disputes, where such investment has been treated unfairly or harmed by host countries.

Given the reality that there are only two cases initiated by Chinese investors based on the BITs of which

China serves as one Contracting Party and such status does not match the scale of Chinese overseas

investment and the huge amount of BITs concluded by Chinese government at all, it is necessary to analyze

the inherent problems of dispute resolution mechanism included in Chinese BITs and the procedural issues

under the ICSID convention.

Case study could be the most direct approach for Chinese investors to understand the characteristics of

such resolution mechanism. Relevant cases will be discussed in respect of both procedure and substantive

issues, including the Tza Yap Shum v. Republic of Peru5 and Ping An Life Insurance Company of China,

Limited and Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China, Limited v. Kingdom of Belgium (Ping An v.

Belgium Case)6. Ping An v. Belgium Case, as the first case filed by Chinese company originally from the

Mainland China before ICSID, has drawn so much attention to Chinese legislatures, Chinese legal

practitioners as well as the media since its registration. This case, especially its outcome, probably will

open a window for Chinese investors to adopt the BITs and its dispute resolutions in settling investment

disputes.

Assuming that the inherent problems in Chinese BITs have been identified by Chinese government, it still

has a long way to go to re-open the negotiation process with other contracting party to revise the context

of BITs or to conclude the updated BITs. Therefore, the question is how to protect Chinese overseas

investment under the incumbent BITs regime. A strategic approach to protect the Chinese overseas

investment can be derived from case study. Generally speaking, it is possible to adopt BITs of other

5Tza Yap Shum v. Republic of Peru, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/6. 6 Ping An Life Insurance Company of China, Limited and Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China, Limited v. Kingdom of Belgium, ICSID Case No. ARB/12/29.

6

countries, for instance Dutch BITs, to protect Chinese overseas investments through strategically

restructuring the business in such countries of which the BITs the investors intend to invoke. This method

has been proved by the ICSID arbitration award in ConocoPhillips Petrozuata B.V., ConocoPhillips Hamaca

B.V. and ConocoPhillips Gulf of Paria B.V. v. Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (ConocoPhilips v. Venezuela

Case )7 that it is acceptable if such business restructuring complies with some certain principles in order

to use BIT between the host state and a third country rather than the BIT between the host country and

the country which the investors originally and ultimately come from. Therefore, it is meaningful for

Chinese investors to take such mechanism into account as an alternative way to protect their investments

where there could be potential investment disputes on the condition that, compared with the BIT

concluded between the host state and the third country, the BIT between China and the host state cannot

be expected to fully protect the Chinese investment or cannot cover the damages or loss of profit

foreseeable at the time of making the investment, or no BIT has been concluded between China and the

host state at the time when Chinese investors are willing to settle the dispute through arbitration against

the host state directly.

Structure of thesis

The thesis consists of four chapters. Chapter one provides the background information of China BITs and

analyzes the main provisions included in China BITs, with the aim of giving further discussion on the

possible improvement and revision of the context of Chinese BITs. In addition, comparison of China BITs

and other BITs will be deeply discussed in chapter one. Chapter two discusses the dispute resolution

mechanisms stipulated in China BITs and analyzes the arbitration before ICSID. In this chapter, Ping An v.

Belgium Case, still in the arbitration proceedings before ICSID, will be discussed. Chapter three interprets

business restructuring issue for the purpose of strategic adoption of BITs rather than China BITs to protect

the Chinese overseas investments. In this chapter, the ConocoPhilips Case will be discussed to enlighten

Chinese investors to think alternatively with regards to the protection approach of investment in an

efficient way. In conclusion part, I would like to make a summary of all the discussions and propose an

appropriate approach to protect Chinese overseas investments within the BITs regime.

7 ICSID Case No. ARB/07/30.

7

Chapter I China BITs Regime

1.1 Overviews of BITs

BITs are international treaties based on public international law concluded between two states for the

purpose of promoting and protecting investments of investors having the nationality of one of the two

contracting parties.8 The conclusion of BITs originated as a reaction of the developed countries’ investors

to the nationalization movements in developing countries, as well as to the appeals of these countries in

the Charter of Economic and Social Rights and Duties of the States.9 Sovereigns purportedly promulgate

these investment treaties as a means to satisfy the need to promote and protect foreign investment and

with a view to enhancing the legal framework under which foreign investment operates.10 Countries all

over the world have been highly motivated to conclude BITs since the first BIT was concluded between

Germany and Pakistan in 1959, with various incentives, for instance, of attracting more foreign investment

to mitigate the gap of shortage of capital, or of protecting the investments made by nationalities of their

countries against the host states. Accordingly, the contents of BITs are affected, more or less, by the

development stages and the main purposes of the contracting parties at the time of the specific BIT was

concluded. This phenomena is obvious especially for emerging countries, such as China, even though there

is a considerable degree of convergence has emerged in terms of the main contents of BITs.

Bilateral parties are able to negotiate with each other considering the specific interests and necessities in

common that can be reflected in the provisions of BIT. In other words, every BIT has been tailored by the

contracting parties to maximize their best interests aiming to meet the needs of contracting countries as

well as their investors. On one hand, it is easy and efficient to reach an agreement in forms of BITs and

other investment treaties between two specific contracting parties, thereby encouraging capital flows

safely to stimulate the foreign investments shortly; on the other hand, this specially tailored BITs lack of

the uniformity thus may increase the concerns of uncertainty of the arbitration awards when it comes to

the similar or even identical investment disputes that need to be settled based on BITs with different

tailored contents when the BITs invoked were concluded by the same responded host state.

8 Lavranos, Nikos, Bilateral Investment Treaty (BITS) and EU Law (September 27, 2010). ESIL Conference 2010. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1683348. 9 Dan Wei, Bilateral investment treaties: an empirical analysis of the practices of Brazil and China, European Journal of Law and Economics, 33, no. 3 (2012): 663-690, 664. 10 Franck, Susan D., Foreign Direct Investment, Investment Treaty Arbitration and the Rule of Law. McGeorge Global Business and Development Law Journal, Vol. 19, p. 337, 2007. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=882443.

8

From the foreign investors’ standpoint, BITs contain attractive substantive provisions whose effects are

amplified by the MFN and NT clauses, 11 which, to large extent, would substantially protect foreign

investors’ interests on the assumption that the sovereign will perform its obligations created by the clauses

thereon. In the context of BITs, investors are allowed to initiate arbitrations against the host state directly

invoking the dispute resolution under the BIT rather than the investment contracts. BIT claims are not

based on contract but are made pursuant to the terms of a BIT irrespective of whether there is otherwise

a relevant contractual relationship.12 Such dispute resolution mechanism empowers investor the direct

access to arbitral tribunals to settle the investment disputes against the host state, thereby ensuring the

procedural rights of protection sought by investors and overcoming the drawbacks of domestic court

litigation as well as diplomatic protection.

1.2 Chinese BITs regime

In 1982, China entered into its first BIT with Sweden. The past three decades have witnessed China’s active

participation in the development of global BITs regime. Until June 2014, China has concluded 130 BITs all

around the world, of which 105 BITs are in force.

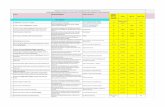

Source: UNCTAD IIA Database, China

The chart above shows geographical distribution of 105 Chinese BITs which are in force. As illustrated from

the chart, China BITs in force cover most countries in Europe and Asia; however, in North America, there

11 Gazzini, Tarcisio, Bilateral Investment Treaties (March 29, 2012). INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT LAW: THE SOURCES OF RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS, T. Gazzini, E. De Brabandere, eds., The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 2012, Forthcoming. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2030872. 12 Kim M. Rooney, ICSID and BIT Arbitrations and China, Journal of International Arbitration, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2007, Volume 24 Issue 6) pp. 689 – 712, 691.

38

37

16

74 3

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF 105 VALID CHINESE BITS

Asia Europe Africa South Ameirca North Ameirca Oceania

9

is no valid BITs between China and the United States, which definitely weakens the Chinese investment

protection in United States, vice versa. It is noticeable that China-Canada BIT just came into force on

October 1 2014. Among the 105 Chinese BITs in force, 17 BITs were concluded in the 1980s and 59 BITs

were made in 1990s which cover more than 50 per cent of the incumbent valid BITs, the rest 29 were

signed or renewed in or after year 2000.13

According to Kim M. Rooney, Chinese BITs fall broadly into two generations of treaties: (a) the first

generation falling roughly into the period from 1982 to the late 1990s; and (b) the second generation from

the late 1990s to the present.14 Won Kidane and Weidong Zhu adopted the “three generations” argument

based on the professor Gallagher & Shan research on Chinese investment history; they divided Chinese

BITs into three generations: the first generation signed from 1982 to 1989 (period of launching of the BIT

program); the second generation from 1990 to 1997 (China’s accession to ICSID); and the third generation

from 1998 to the present. 15 Technically, it is hard to find the manifest boundary between different

generations. The evolution of Chinese BITs reflects the development stages of economy in China and also

the extent that China’s activities the international conventions regarding the foreign investment protection.

It is noticeable that there are some key elements driving the evolution of terms in BITs that China entered

into. One of these cornerstones was China’s accession to the ICSID Convention in 1993 broadening the

dispute resolution mechanism so that Chinese investors are able to get access to international arbitration

directly against the host state before ICSID; however, the dispute is only limited to dispute of quantum of

compensation for expropriation or nationalization. Accession to ICSID also called for modernization of BITs

as to the dispute resolution clause that China would adopt on China’s post ICSID era. In 2001, the year of

China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (“WTO”)16 accelerated the alteration of terms of China

BITs. From China’s access to WTO up to now, revision of BITs has been more active than ever before. More

than 12 per cent of the China BITs that are in force have been replaced by new BITs since the new

millennium17, and such renewal de facto improves the modernization level of China BITs regime, and to

13 See UNCTAD IIA Database, available at: http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/IIA. 14 Kim M. Rooney, ICSID and BIT Arbitrations and China, Journal of International Arbitration, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2007, Volume 24 Issue 6) pp. 689 – 712, 701. 15 Kidane, Won and Zhu, Weidong, China-African Investment Treaties: Old Rules, New Challenges (July 18, 2014). Fordham International Law Journal, Vol. 37, 2014, 1052-1055. 16 Kidane, Won and Zhu, Weidong, China-African Investment Treaties: Old Rules, New Challenges (July 18, 2014). Fordham International Law Journal, Vol. 37, 2014, 1053. 17 See UNCTAD IIA Database, China.

10

some extent, overcomes the inherent problem with the terms of China BITs. Such modernization will be

discussed in next part.

1.3 Clause analysis of China BITs – from vertical and horizontal perspective

As discussed above, China BITs have been and still are experiencing a significant evolution regarding the

terms and also the methodologies behind it. It is necessary to analyze the main provisions of BITs from

vertical perspective to identify evolution of terms of BITs. For vertical perspective, selection of BITs of

which China entered into with the same countries in different periods will be the clearest way to review

the clauses and the logics behind them. In respect of horizontal perspective, comparable research

between China BITs and the BITs entered into by other countries in the same period would show the

differences in between, thus may enlighten the revision process as to terms of China BITs.

1.3.1 Preamble

Most BITs are prefaced with a preamble, in which the contracting parties state their intentions and

objectives when concluding the agreement.18 Quite often, given that it does not create legal relationships

that are binding, preamble dose not draw much attention as the substantive and procedural provisions

incorporated in BITs. As provided for by Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties19 preamble constitutes

part of the agreement and is meaningful in interpretation of the purpose and the objectives of the

agreement.

China BIT adopted this preamble approach in most of BITs, for instance, China-Italy BIT states that: 20

“Desiring to intensity economic cooperation between both countries, Intending to

create favorable conditions for investments by nationals and companies of either

country in the territory of the other country and Recognizing that encouragement

and protection of such investments will benefit the economic prosperity of both

countries,”

This preamble focuses on the importance of fostering economic cooperation among the contracting

parties, promoting favorable conditions for reciprocal investments and recognizing the impact that such

18 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Bilateral Investment Treaties 1995-2006 : Trends in Investment Rulemaking, United Nations, 2007, 3. 19 See Article 31 of Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. 20 See Agreement between the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Government of the Italy concerning the Encouragement and Reciprocal Protection of Investments.

11

investment may have in generating prosperity in the host country.21 The similar preamble clauses exist in

many China BITs that concluded in 1980s and 1990s, such as BITs with Poland, Bulgaria, Norway, Singapore,

Croatia, Belgian-Luxembourg, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. 22

A significant change of China BITs during the BIT renewal process is that some China BITs included

additional elements, such as technology issues. China and the Netherlands entered into new BIT in 2004,

in which it emphasized the importance of stimulation of flow of capital and technology and such issues

had not been incorporated in the replaced BIT between the two countries23, and the same clause can also

be found in China-Djibouti BIT24. The change in preamble reflects the transition that China is focusing more

on technology exchange than ever before rather than simply emphasizing the capital imported into China

as in the early 1980s.

An increasing number of preambles indicate that BITs do not purport to promote and protect investment

at the expense of other key values such as health, safety, labor protection and the environment. 25 China-

Korea-Japan Investment Agreement adopted this trend in its preamble, which stipulates,”…Recognizing

that these objectives can be achieved without relaxing health, safety and environmental measure…”26 It is

worthy to notice that China-Korea-Japan Investment Agreement was concluded in 2012 and came into

force in May 17, 2014, which, to some extent, is representing the latest strategies that adopted by Chinese

government in negotiating the terms of BITs.

1.3.2 Definitions

Definitions in BITs refer to the interpretation of two key elements: investments and investors. With respect

to investment, most BITs of the last 10 years have continued to adopt a broad asset-based definition of

investment, the scope of which goes beyond covering only foreign directive investment.27 The definition

21 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Bilateral Investment Treaties 1995-2006 : Trends in Investment Rulemaking, United Nations, 2007, 3. 22 BITs China entered into with Belgian-Luxembourg, Switzerland, and the Netherlands have been replaced by the new BITs. 23 See Agreement on Reciprocal Encouragement and Protection of Investments Between the People's Republic of China and the Kingdom of the Netherlands 24 See Agreement Between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of Djibouti on the Promotion and Protection of Investments 25 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Bilateral Investment Treaties 1995-2006 : Trends in Investment Rulemaking, United Nations, 2007, 4. 26 See Agreement Among the Government of the People's Republic of China, the Government of Japan and the Government of the Republic of Korea for the Promotion, Facilitation and Protection of Investment. 27United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Bilateral Investment Treaties 1995-2006 : Trends in Investment Rulemaking, United Nations, 2007, 8.

12

covers every kind of assets or any kind of assets, accompanies by a list of examples.28 Apparently, China

has been always following such approach to define what kinds of investments shall fall into the BITs. In

China-Switzerland BIT, the investment is defined as follows,

The term ‘investment shall include every kind of asset, and in particular: (a) movable

and immovable property as well as any other rights in rem, such as servitudes,

mortgages, liens, pledges and usufructs; (b) shares, parts or any other kind of

participation in companies; (c) claims to money or to any performance having an

economic value; (d) copyrights, industrial property rights (such as patents, utility

models, industrial designs or models, trade or service marks, trade names, indications

of origin), know-how and goodwill; (e) business concessions under public law, including

concessions to search for, extract or exploit natural resources as well as all other rights

given by law, by contract or by decision of the authority in accordance with the law.29

Dutch Model BITs adopted the same approach as well, while the United States takes different approach in

respect of defining investment. According to the United States Model BITs published in 2012, investment

is defined in form of combination of circular definition and close-lists definition. 30 The significant influence

with adoption of this approach is that it may, to some extent, address the jurisdiction problem where

investment in one contracting party made by a company which was incorporated in the non-contacting

party but is directly controlled by an investor from the other contracting party. In this case, the American

investor can initiate arbitration against the host state based on U.S. BIT to protect his investment

irrespective of the fact that the investment was made directly by an entity in the third non-contracting

state, if the investor could prove the investment is directly or indirectly controlled by him or her. China has

taken this flaw into account when it comes to the non-contracting party by means of extending the

28 Ibid 29 See Agreement Between the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Government of the Confederation of Switzerland on the Reciprocal Promotion and Protection of Investments. 30 See Article 1, Section A of 2012 U.S. Model Bilateral Investment Treaty: “investment” means every asset that an investor owns or controls, directly or indirectly, that has the characteristics of an investment, including such characteristics as the commitment of capital or other resources, the expectation of gain or profit, or the assumption of risk. Forms that an investment may take include: (a) an enterprise; (b) shares, stock, and other forms of equity participation in an enterprise; (c) bonds, debentures, other debt instruments, and loans; (d) futures, options, and other derivatives; (e) turnkey, construction, management, production, concession, revenue-sharing, and other similar contracts; (f) intellectual property rights; (g) licenses, authorizations, permits, and similar rights conferred pursuant to domestic law; and other tangible or intangible, movable or immovable property, and related property rights, such as leases, mortgages, liens, and pledges.

13

definition of investor. China- Uzbekistan BIT31, concluded in 2011, provides that legal entities constituted

under the laws of an nоn-contracting Party but directly owned or controlled by nationals in paragraph (a)

or enterprises in Paragraph (b)32 is a qualified investor falling the scope of BIT.

A number of China BITs have been embedded with limitations regarding the investment. BIT between

China and Belgium-Luxemburg Economic Union defines investment as follows,

“ Investment means every kind of asset invested by investors of one contracting party

in accordance with the laws and regulations of the other contracting party in the

territory of the latter, and in particular[…].’’33

This limitation indicates that investment covered by BITs shall comply with laws and regulations of the host

state, otherwise such investment may be precluded from the scope of investment defined in the BITs.

Therefore, such investment cannot be covered by the protection mechanism concluded in the foregoing

BITs.

The basic premise of a BIT is that only a national of one of the two contracting states may bring a claim

under it. The definition of a national is usually in two parts, dealing with natural persons on the one hand

and legal persons on the other.34 With respect to natural persons, a typical BIT protects the natural persons

who have the nationality of one of the contracting parties. Thus, in China-Netherlands BIT, investor as to

natural person is that who have nationality of either contracting party in accordance with the laws of that

contracting party.

Nationality of a natural person may give rise to dispute when it comes to dual nationality. In Soufraki v.

United Arab Emirates Case, 35 Mr. Soufraki, as claimant, claimed under BIT between Italy and the United

Arab Emirates based on his Italian nationality so as to an investor under the BIT thereon, however, Mr.

31 Agreement between the Government of the People's Republic Of China and the Government of the Republic of Uzbekistan on the Promotion and Protection of Investments. 32 Paragraph (a) and paragraph (b) of Article 2 (2) China- Uzbekistan BIT stipulate that: the term “national” means natural persons who have nationality of either Contracting Party in accordance with the applicable laws of that Contracting Party; “enterprise” means any entities, including companies, firms, associations, partnerships and other organizations incorporated or constituted under the applicable laws and regulations of either Contracting Party and have their seats and substantial business activities in that Contracting Party, irrespective of whether or not for profit and whether it is owned or controlled by private person or government or not. 33 See article 1 paragraph 2 of Agreement between the Government of The People’s Republic of China and the Belgium-Luxemburg Economic Union on the Reciprocal Promotion and Protection of Investments. 34 Peter J. Turner, Chapter 10 Investor State Arbitration in Michael J. Moser (ed), Managing Business Disputes in Today's China: Duelling with Dragons, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2007) pp. 233 – 258, 236. 35 Soufraki v. United Arab Emirates, ICSID Case No. ARB/02/7.

14

Soufraki held the nationality of Canada at the same time. The UAE challenged his right to bring the claim

on two grounds. First, it asserted that Mr. Soufraki no longer held Italian citizenship as a result of having

obtained Canadian citizenship, and, secondly, that his Canadian citizenship was his dominant or ‘effective’

nationality and that he could thus not rely on his Italian nationality in order to bring him within the

definition of an ‘investor’ under the BIT. 36The Tribunal found that it lacked jurisdiction to hear the dispute,

and, therefore, declined to decide the case on its merits. As the Tribunal came to the conclusion that the

Claimant did not have Italian nationality, it did not need to rule on the effectiveness of that nationality.37

The tribunal also held that its competence to examine whether, as matter of fact, Mr. Soufraki was still a

qualified Italian citizen under the Italian law after he has lost the citizenship before and thereby making

its own decision on such issue, irrespective of the certificate of his Italian citizenship issued by Italian

authorities. As to the legislation in China regarding to the nationality, dual nationality is not allowed in

accordance with Article 9 of Nationality Law of China came into force in 1980.38 In reality, there are indeed

a huge number of Chinese de facto processing dual nationality. As interpreted by the tribunal in In Soufraki

v. United Arab Emirates case, it may be problematic when Chinese people who hold the dual nationality

intend to initiate an arbitration on the basis of China BITs. If the tribunal examines the laws of China to

determine the nationality issue, and it does have the power to do it according to the Soufraki Case, it

would conclude that it has no jurisdiction regarding the issue based on the fact that the claimant is not a

qualified investor defined in China BITs, since the claimant has been not a citizen of China any more under

the laws of China.

As to legal persons, it is clear that China BITs define legal person as to investor by means of two criteria

referring to the place of incorporation and the seat of the company. Very often, investments are made

indirectly, through one or more interposed corporate vehicles. This gives rise to several issues for the

purposes of determining whether or not a given legal person qualifies as an investor under a given BIT.39

The point is the definition of investor contained in the BITs. As aforesaid China- Uzbekistan BIT allows legal

persons who indirectly control the investment to be covered by BIT. In case of no specific provisions in BIT

that the investments could be held indirectly, ICSID cases show that BITs are still applicable to indirect

investments made by investors. Despite the treaty's not specifying that investments could be held

36 Supra note 33, at 236. 37 ICSID Case No. ARB/02/7, Decision of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Application for Annulment Of Mr. Soufraki, 8 37 Article 9 of Nationality Law of China provides that: any Chinese national who has settled abroad and who has been naturalized as a foreign national or has acquired foreign nationality of his own free will shall automatically lose Chinese nationality. 39 Supra note 33, at 238.

15

indirectly, the tribunal came to the conclusion that it did support indirect investments as neither a literal

nor systematic interpretation demanded a different outcome.40

1.3.3 Fair and equitable treatment

With respect to fair and equitable treatment, Article 2(1) of China-Sweden BIT articulates as follows, “Each

Contracting State shall at all-time ensure fair and equitable treatment to the investments by investors of

the other Contracting State.” Nearly all the China BITs follow this approach to define this treatment.

However, fair and equitable treatment give rise to problems when it comes to the standard that shall be

adopted in interpretation of this treatment. It may be subject to the principles of international law,

national laws and regulations or customary international law. For instance, BIT between France and

Uganda states fair and equitable treatment shall be subject to the principles of international law.41 Linking

the fair and equitable treatment standard to the principles of international law removes the possibility of

interpreting the provision using the semantic approach.42 BIT between the countries of the Caribbean

common market and Cuba adopted the national laws and regulation approach. 43 It is clear that China

adopts the plain fairness standard in regard of interpretation of fair and equitable treatment, depending

on the tribunal to delineate the inherent and intrinsic meaning when it comes to disputes arising out of

fair and equitable treatment, as a consequence, the uncertainty of the interpretation of fair and equitable

treatment may result in the uncertainty of the outcome of the tribunal decisions.

1.3.4 Most favored nation treatment

A BIT also may provide for most favored nation treatment (MFN treatment), which means that a host

country may not treat an investor or investment form a BIT partner any less favorably than it treats

investors or investment in like circumstances from any other country.44 When states enter into a treaty

containing the MFN clause, they agree to accord each other the same treatment they grant to any nation.45

MFN clause has been embodied in China BITs since the conclusion of China’s first BIT with Sweden. China-

40 Siemens A.G. v. The Argentine Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/02/8, Decision on Jurisdiction dated 3 August 2004, 44 ILM 138 (2005). 41 See Article 3 of Agreement Between the Government of the Republic Of France and the Government of the Republic of Uganda on the Reciprocal Promotion and Protection of Investments. 42 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Bilateral Investment Treaties 1995-2006 : Trends in Investment Rulemaking, United Nations, 2007, 31 43 See Article IV of BIT between CARICOM and Cuba. 44 Kim M. Rooney, ICSID and BIT Arbitrations and China, Journal of International Arbitration, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2007, Volume 24 Issue 6) pp. 689 – 712, 695. 45 Scott Vesel, clearing a path though a tangled jurisprudence: Most-favored-nation clauses and dispute settlement provisions in bilateral investment treaties, 32 YALE J. INT’L L.126, (2007).

16

Germany BIT contemplates that “(N)either Contracting Party shall subject investments and activities

associated with such investments by the investors of the other Contracting Party to treatment less

favorable than that accorded to the investments and associated activities by the investors of any third

State.”46

The problem arising from the MFN treatment is that, for instance, whether a Chinese investor is allowed,

relying on the MFN clause that contained in China–Germany BIT to initiate an arbitration against a third

country who entered a BIT with Germany. There has been some debate regarding whether, as a matter of

principle, a MFN clause should also have effect on procedural of importing procedural rights.47 The tribunal

adopted different approaches to solve this problem. In Maffezini v. Spain case, 48 the tribunal held the view

that provisions regarding international arbitration and the other dispute resolution are so essential for

protection of investment under the BIT that these rights must be part of the treatment covered By a MFN

clause. Following this broad interpretation adopted by the tribunal it is possible for Chinese investor to

claim under the example listed above. The tribunal in Plama case, 49on the other hand, argued in favor of

a presumptively narrow interpretation of MFN clause, 50based on various reasons such as treaty-shopping

and the intention of the parties. The approaches adopted by the tribunals in solving the problem listed in

the beginning of this paragraph will result in uncertain outcomes of the cases. Given the absence of dispute

resolution in some China’s first generation BITs and the limitation of scope applicable before ISCID

arbitrations, the prevalence of Maffezini approach in ICSID arbitration will be essential for Chinese

investors to protect their investments.

1.3.5 Expropriation

Historically, one of the main drivers of BITs has been foreign investors’ concern to protect their investments

against the risk of unlawful expropriation. 51 Generally, BITs allow host states to expropriate foreign

investment on certain conditions for public interests and under due process. Article 3 of China-Sweden BIT

provides that “(N)either Contracting State shall expropriate or nationalize, or take any other similar

46 Article 3 (3) of Agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany and the People's Republic of China on the Encouragement and Reciprocal Protection of Investments. 47 Kim M. Rooney, ICSID and BIT Arbitrations and China, Journal of International Arbitration, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2007, Volume 24 Issue 6) pp. 689 – 712, 706. 48 Emilio Agustín Maffezini v. Kingdom of Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/97/7. 49 Plama Consortium Limited v. Republic of Bulgaria, ICSID Case No. ARB/03/24. 50 Aaron M. chandler, BITs, MFN, Treatment and the PRC: the impact of China’s ever-evolving Bilateral investment treaty practice, 43 INT’L LAW 1303, (2009). 51 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Bilateral Investment Treaties 1995-2006: Trends in Investment Rulemaking, United Nations, 2007, 44.

17

measure in regard to, an investment made in its territory by an investor of the order Contracting State,

except in the public interest, under due process of law and against compensation, the purpose of which

shall be to place the investor in the same financial position as that in which the investor would have been

if the expropriation or nationalization had not taken place.” It is obvious that expropriation in China BITs

has been defined very broadly, including expropriation, nationalization and any measures that have the

similar effects as expropriation and nationalization. The languages used in China BITs regarding

expropriation are various. For instance, China-Dutch BIT does not include a specific reference to indirect

expropriation or nationalization, comparably, China-Germany BIT explicitly prohibits the host countries

from directly or indirectly expropriating or nationalizing foreign investment. The linguistic difference

indicates the different concerns as to the expropriation clauses. For China BITs concluded with similar

expropriation provisions as those in China-Sweden BIT, problem may arise that whether Chinese investors

are able to invoke expropriation provisions to protect their investments in case of indirect expropriation.

For China-Germany BIT, the questions arises as to whether, in addition to direct or indirect expropriation,

the clause recognizes a third category of measures as covered by the expropriation provision,52 and the

potential effects are yet to be explored.53 In order to avoid the question that may arise as discussed above,

the expropriation provisions shall include the direct and indirect expropriation and nationalization as well

as measure taken have the equivalent effects with expropriation and nationalization, and provide the

relevant guidance with respect to the criteria that can be referred to in determining the indirect

expropriation and the equivalent effects. Such approach has been adopted in China-Switzerland BIT.54

As mentioned in preceding paragraph, BITs allow the host countries to expropriate foreign investors under

certain conditions. Generally, host countries are allowed to expropriate investment provided that the

expropriation is done in the public interest, under due process of law, on a non-discriminatory basis and

based on the payment of reasonable compensation. A survey of the BITs concluded since 1995 reveals a

remarkable degree of convergence with respect to the conditions required to make expropriations

lawful.55 With respect to the due process of law, China BITs require that the legality of expropriation shall

be subject to domestic legislation. Examples can be found in China BITs came into force after 2000, such

52 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Bilateral Investment Treaties 1995-2006: Trends in Investment Rulemaking, United Nations, 2007, 44. 53 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Bilateral Investment Treaties 1995-2006: Trends in Investment Rulemaking, United Nations, 2007, 44. 54 See Article 6 of China-Switzerland BIT. 55 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Bilateral Investment Treaties 1995-2006 : Trends in Investment Rulemaking, United Nations, 2007, 44

18

as BITs with the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland. It is worthy to notice that some China BITs

concluded in 1980s require the judicial review by the competent court of the contracting parties to

determine the legality of the expropriation. An example is China-Thailand BIT, which contemplates that,

“(T)he legality of any expropriation, nationalization or similar measures mentioned above shall be subject

to review by the competent court of the Contracting Party taking the expropriatory measures56”, however,

such review by domestic court has been removed in BITs China entered into after 2000, thereby

empowering the tribunal to determine the legality of expropriation in accordance with the domestic

legislation of the contracting party. In respect of compensation for expropriation, China BITs do not fully

adopt the so called “Hull Rules” advocated by the western countries, 57 under which the compensation

shall be prompt, adequate and effective. China-Dutch BIT provides that the compensation shall be

equivalent to fair market value of the expropriated investment immediately before the expropriation

measures were taken.58 The newly signed China BITS has accepted the rule of effective and prompt, but

are still in controversy regarding the requirement of adequate.

1.3.6 Umbrella clause

Article 3(4) of China-Netherlands BIT states: “Each Contracting Party shall observe any commitments it

may have entered into with the investors of the other Contracting Party with regard to their investments.’’

Such clauses are designed to cover any commitment or undertaking made by the host state with respect

to the investor in relation to his investment.59 It should be recalled as well that an umbrella clause or

widely drafted dispute resolution clause would only protect the investor if the contract is with the state or

an emanation of the state for which the state has responsibility in the eyes of international law.60 Umbrella

clause indicates that Contracting State to observe all investment obligations contained not only in BITs and

other investment treaties, but also in investment contracts. The significance of such an application is that

the international arbitration tribunal constituted under the BIT would thereby have jurisdiction over

breach-of-contract claims since a breach of the investment contract is also a breach of the umbrella

56 See Article 5 (1)(b) of China-Thailand BIT; also see Article 6(2) of China-Singapore BIT, Article 6(2) of China- Sri Lanka. 57 Jinxin Qiu and Yingmao Tang, BITs and foreign investments of Chinese enterprises, China law journal, October, 2010. 58 See Article 5(1)(c) of China-Netherlands BIT 59 Peter J. Turner, Chapter 10 Investor State Arbitration in Michael J. Moser (ed), Managing Business Disputes in Today's China: Duelling with Dragons, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2007) pp. 233 – 258, 247. 60 Ibid

19

clause.61 The tribunal in SGS v. Philippines held that it has jurisdiction over such a dispute, however, it

should not exercise such jurisdiction if the contract embedded with an exclusive jurisdiction clause

referring the dispute to a different forum rather than an international arbitration tribunal.62 To the contrary,

the Tribunal of SGS v. Pakistan concluded that the umbrella clause did not entitle the claimant to bring an

arbitration based on BIT.63 The outcomes of the two arbitration result in uncertainty of application of

umbrella clause under BITs in term of its applicability.

Although some argues that the better interpretation is that an umbrella clause enables a BIT tribunal to

exercise jurisdiction over claims concerning such breaches of contract, which are also BIT violations under

the clause, and further permits the tribunal to do so notwithstanding an exclusive forum selection clause

in the contract. Indeed, as detailed below, any other interpretation of the umbrella clause, including those

advanced by the SGS decisions, effectively eviscerates the umbrella clause, and is at odds with the clear

language and purpose of the clause as reflected in its history.64 Whether the umbrella clause is applicable

depends on languages used in BITs as well as the interpretation by tribunals case by case. Thus, following

the decisions made by tribunal, from practical perspective the prudent and realistic choice for investors is

to apply the umbrella clause in an investor-state arbitration where there is absence of exclusive jurisdiction

clause concluded in the investment contract between an investor and the host state.

1.3.7 Compensation for damages and losses

China BITs, as many traditional BITs, include the clause for compensation for damages and losses due to

the war, national emergency, riot and other similar events in order to make sure the equitable treatment

regarding to indemnification, compensation and other settlements. Such clause may be crucial to Chinese

investors since the wars and riots in many politically unstable countries have resulted in huge loss for

investors there. As mentioned in introduction part, Libya war caused tremendous losses for Chinese

investments and business opportunities, therefore, it is possible foe Chinese investors to claim against the

Libya government bases on such clauses together with other clauses under BITs for compensation.

Unfortunately, China-Libya BIT has not been entered into force until now.

61 Wong, Jarrod, Umbrella Clauses in Bilateral Investment Treaties: Of Breaches of Contract, Treaty Violations, and the Divide between Developing and Developed Countries in Foreign Investment Disputes (August 29, 2008). George Mason Law Review, Vol. 14, 2006. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1260897. 62 See SGS Société Générale de Surveillance S.A. v. Republic of the Philippines, ICSID Case No. ARB/02/6. 63 See SGS Société Générale de Surveillance S.A. v. Islamic Republic of Pakistan, ICSID Case No. ARB/01/13. 64 Wong, Jarrod, Umbrella Clauses in Bilateral Investment Treaties: Of Breaches of Contract, Treaty Violations, and the Divide between Developing and Developed Countries in Foreign Investment Disputes (August 29, 2008). George Mason Law Review, Vol. 14, 2006. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1260897.

20

1.4 Conclusion It is obvious that China BITs regime not only covers most jurisdictions in the world, but also arguably

provides for substantive protections considering the recent development in evolution of clauses.

Meanwhile, it is still uncertain that whether Chinese overseas investments can be truly protected due to

the limitations contained in the first generation China BITs. Discussions in this chapter are only referred to

the substantive protection clauses in BIT, dispute resolution, as cornerstone clause in BIT, will be analyzed

in next chapter in order to give better understanding of BIT and its function.

Chapter II Dispute Resolution and ICSID Arbitration

Historically, a foreign investor deprived of its property had to rely on its own government's willingness to

take up a claim on its behalf and then only if it spent further time and money exhausting local remedies.65

Such resolution mechanism has been altered since BITs are introduced to protect the investors. According

to the survey with respect to dispute resolution provisions in international investment agreement, 93% of

the selected samples of BITs contain language on investor-state dispute resolution66 , under which the

investors are entitled to claim directly against host states from both procedural and substantive

perspectives. Consequently, the investor-state arbitration cases before ICSID have witnessed a dramatic

increasing since Holiday Inns S.A. against Morocco, as the first case before ICSID, in 1972. 67

2.1 Overview of dispute resolution mechanism in China first and second generation BITs

For a long time, China was reluctant to trust international adjudication and kept a very cautious attitude

towards ICSID investor-state arbitration by only allowing for disputes relating to the compensation

amounts of expropriation to be submitted to international arbitral tribunal. 68 Actually, there is no

provisions regarding investor-state dispute resolution in China first BIT with Sweden in 1982. An attached

letter between China and Sweden stated that upon China’s accession to the Washington convention, the

BIT would be supplemented with a supplementary agreement on a binding system for the settlement of

65 Kim M. Rooney, ICSID and BIT Arbitrations and China, Journal of International Arbitration, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2007, Volume 24 Issue 6) pp. 689 – 712, 691. 66 See Pohl, Joachim and Mashigo, Kekeletso L. and Nohen, Alexis, Dispute Settlement Provisions in International Investment Agreements: A Large Sample Survey (November 1, 2012). OECD International Investment Working Paper No. 2012/2. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2187254. 67 See ICSID Caseload-Statistics, Issue 2012-2, p. 7. Available at: http://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet?requestType=ICSIDDocRH&actionVal=ShowDocument&CaseLoadStatistics=True&language=English31. 68 Qi, Tong, How Exactly Does China Consent to Investor-State Arbitration: On the First ICSID Case against China (2012). Contemporary Asia Arbitration Journal, Volume 5, Issue 2, pp. 265-291, November 2012. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2181451.

21

disputes with the ICSID framework. 69 Such similar provisions were included in many early or so-called first

generation of China BITs. 70 Under first generation of China BITs, disputes between an investor and the

host state could be resolved through administrative review in host state or local court that has jurisdiction

over the host state that accepted the foreign investments. . Furthermore, only after that authorities had

determined the existence of the expropriation by the government could the foreign investor commence

arbitration under the relevant BIT to determine the amount of the compensation. 71 As a consequence,

for the first generation China BITs investor-state dispute resolution has been strictly limited within the

scope of local remedies rather than widely accepted international arbitration whilst only the dispute

concerning the amount of compensation for expropriation can be referred to an ad hoc arbitral tribunal

in line with Arbitration Rules of UNCITRAL.72

Despite the linguistic variation of dispute resolution clauses, investor-state dispute resolution mechanism

adopted in China first generation BITs usually contained following items73:

Any dispute concerning investment between investors of one Contracting Party and

other Contracting Party shall be settled amicably as far as possible by the two parties

concerned.

If the dispute cannot be settled within six months from the date on which either related

party files a request for settlement it shall be resolved by either one of the following

procedures chosen by the investors: (a) filing a complaint with the competent

administrative authority of the Contracting Party which accepts the investment; (b)

filing a complaint with the court of justice that has jurisdiction over the Contracting

Party which accepts the investment.

A dispute arising from disagreement on the amount of compensation payments can be

resolved by ad hoc arbitral tribunal, pursuant to the period in which the court made the

decision if the parties concerned has resorted to local remedies approach.

Different tribunals may hear the dispute concerning amount of compensation for expropriation, such as

ad hoc tribunal established under the UNCTRAL arbitration rules, established according to clauses in the

69 Letter attached to agreement on the mutual protection of investment, March 29,1982 from ambassador of Sweden to vice minister for economic affairs, Beijing, available at : www.unctadxi.org. 70 See China-Turkey BIT (1988) and China- Republic of Korea BIT (1992). 71 Kim M. Rooney, ICSID and BIT Arbitrations and China, Journal of International Arbitration, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2007, Volume 24 Issue 6) pp. 689 – 712, 702. 72 See Protocol of China- France BIT(1984). 73 See China-France BIT and its Protocol (1984).

22

BITs, or set up by agreement of the contracting parties of the BITs. As mentioned above, after China

accession to Washington convention, such dispute can be submitted to ICSID, provided that both BIT

contracting parties entered into supplementary agreement for such submitting.

In 2000 China concluded BIT with Botswana, as a milestone for China BITs in term of dispute resolution

mechanism, in which China unconditionally consented to submit all dispute between investor and host

state to be settled before ICSID. 74 However, such unconditional consent to arbitration before ICISD does

not constitute the exclusive dispute resolution mechanism in China BITs. For instance, either of the party

to the dispute is entitle to submit the dispute to domestic court in the territory of the contracting party

accepting the investments under China-Botswana BIT. Such approach is followed by China-Netherlands

BIT and China-Germany BIT, but China-Netherlands BIT adopts the different method to solve the conflict

between international arbitration and domestic court as to fora.

2.2 ICSID arbitration

2.2.1 Access to international arbitration

Various institutions offer arbitration services, and the BITs also refer to different arbitration bodies as

choices of forum, for instance, the tribunal under ICSID, the ad hoc tribunal under UNCITRAL rules, the ICC

and also the ad hoc tribunal specifically established according to the provisions under the relevant BIT.

ICSID as well as ad hoc tribunal established according to UNCITRAL rules are by far the most often

mentioned as possible fora for investor-state resolution mechanism, while the ICC comes a distant third.75

Other fora, including treaty-designed ad hoc tribunals and regional tribunals in Stockholm, Cairo, Bogota,

etc. are mentioned infrequently.76

As abovementioned, China first generation BITs provide for various forums for investor to choose when it

comes to the dispute arising from the amount of compensation for expropriation. There are some

significant alterations regarding the international arbitration contained in China second generation BITs.

Firstly, China extended the scope of dispute that can be submitted to the international arbitration for

settlement from only the dispute of amount of compensation for expropriation to all disputes or any

dispute,77 That is to say Chinese investor is entitled to initiate arbitration against the host state for any

74 See Article 9 of China- Botswana BIT(2000) 75 Pohl, Joachim and Mashigo, Kekeletso L. and Nohen, Alexis, Dispute Settlement Provisions in International Investment Agreements: A Large Sample Survey (November 1, 2012). OECD International Investment Working Paper No. 2012/2. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2187254 76 Ibid 77 See China-Netherlands BIT, China-Germany BIT, China-Canada BIT, China-Russia BIT and China-Latvia BIT.

23

dispute arising from or in connection with the host state’s activities where such activities violate the

substantive protections under the relevant BITs. Secondly, China is starting to give unconditional consent

to the submission of a dispute to international arbitration, which complies with the “written consent”

requirement of the ICSID Convention.78

Choices of international arbitration forum contained in China BITs fall, despite the variation of languages,

into the three categories: tribunal established under ICSID, ad hoc tribunal under UNCITRAL rules and the

tribunal designed by the relevant BIT or parties. Such approach follows the normal way as to choice of

forum worldwide. ICSID arbitration will be further discussed below.

2.2.2 ICSID and ICSID Convention International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (the Center) was created by the Convention

on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States 1965 (the

Convention) entered into force in October 1966 and has been ratified by 150 states,79 which has covered

most States all over the world. ICSID Convention provides an autonomous regime for submitting disputes

to arbitration or conciliation, 80and acts as forum to settle the legal investment dispute between investors

and the host state. The World Bank group, which facilitated drafting of the ICSID convention, was

appropriately positioned to serve as a core of the newly created international dispute resolution

mechanism.81 ICSID can be an adequate mechanism to solve investment dispute between a state and an

investor using arbitration or conciliation, provided that both the host state and the home state have

ratified the Convention-

In accordance with the Convention, ICSID was established with a simple structure, the Administrative

Council and Secretariat. The Administrative Council is the governing body of the ICSID, comprised of one

representative of each of ICSID contracting states. Principal functions of the Administrative Council include

the election of the Secretary-General and the Deputy Secretary-General, the adoption of regulations and

rules for the institution and conduct of ICSID proceedings, the adoption of the ICSID budget, and the

78 See China-Netherlands BIT, China-Germany BIT, China-Mexico BIT. 79 There are currently 159 signatory states to the ICSID Convention. See: https://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet?requestType=CasesRH&actionVal=ShowHome&pageName=MemberStates_Home 80Julian D.M. lew: ICSID Arbitration: special Feature and recent Developments, Arbitrating foreign investment disputes Arbitrating foreign Investment Disputes / ed. by Norbert Horn, Kluwer Law International, 2004., P. 267-282, 269 81 Kryvoi, Yaraslau. ‘International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID)’. In International Encyclopedia of Laws: Intergovernmental Organizations, edited by Jack Wouters. Alphen aan den Rijn, NL: Kluwer Law International, 2013.

24

approval of the Annual Report on the operation of ICSID.82 The Secretariat consists of a Secretary-General

and his or her deputies. The Secretary-General also acts as the registrar with the authority to decide at the

initial stage whether a claim is manifestly outside the jurisdiction of the Centre in accordance with Article

36(3) of the Convention.83

Prior to 1997, there were mere cases filed to ICSID with less than 1 case per year on average. In fact in

ICSID’s first six years no case was filed. From 1997, the registered cases in ICSID have been increasing

dramatically. Up to June 30, 2014, there are 473 cases registered under the convention, of which 420 are

arbitration cases; 63.7 per cent of the ICSID registered cases are based on the consent invoked from BITs

to establish ICSID jurisdiction.84 Such phenomena implies, to some extent, the tied relationship between

the BITs and the popularity of the ICSID’s jurisdiction.

The Chinese government ratified the convention in 1993 and the ICSID convention entered into force for

China on February 06, 1993. In the notification to ICSID, the Chinese Government would only consider

submitting the jurisdiction of ICSID over the compensation resulting from expropriation and

nationalization. 85 As discussed above, many Chinese first BITs state that only the disputes of the amount

of compensation for expropriation are allowed to be submitted to ICSID for arbitration following the

reservation made by Chinese government in ratification of the Convention.

Jurisdiction of ICSID

The jurisdiction issue in an arbitration case has always been essential as a preliminary problem to be solved

by the arbitral tribunal. For the fiscal year 2013, 31 per cent finds of the ICSID declined the jurisdiction of

ICISD.86 The ICSID Convention stipulates the extent of its jurisdiction in details. Article 25 (1) of the

convention contemplates the jurisdiction of the Center that the Center has the jurisdiction over a dispute

on conditions as follows: 87

(1) any legal dispute;

82See: https://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/Index.jsp. 83 Kryvoi, Yaraslau. ‘International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID)’. In International Encyclopaedia of Laws: Intergovernmental Organizations, edited by JackWouters. Alphen aan den Rijn, NL: Kluwer Law International, 2013. 84 THE ICSID CASELOAD – STATISTICS (ISSUE 2014-2), available at: https://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet?requestType=ICSIDDocRH&actionVal=ShowDocument&CaseLoadStatistics=True&language=English52. 85 See https://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet 86 See ICSID Annual Report 2013, at 27. 87 See Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention.

25

(2) directly out of an investment;

(3) between a contracting state and a national of another contracting state;

(4) the parties to the dispute consent in writing to submit to the Center.

Given the nature of the foreign investments and the concerns of the substantive outcome of the case

before the Center, it is common for the Respondent involved in disputes, usually the host state, to

challenge the tribunal on its jurisdiction over the case. Arbitral tribunal therefore has to review the

particular case at issue to decide whether it falls in the jurisdiction of the Center. Take the term

“investment” as an example, ICSID convention itself does not provide the definition of investment. The

tribunal usually refer such definition to BITs in order to decide the jurisdiction issue. . From Chinese

investors’ perspective, the following aspects at issue may come into trouble when the arbitral tribunal

considering the jurisdiction challenged by the host state.

Locally incorporate companies

As mentioned above, by the end of the 2013, approximately 16,000 Chinese investors have established

22,000 companies or enterprises in 179 countries and regions all over the world. Therefore, the company

is the most commonly used legal form when it comes to foreign investment. The term of investor in China

BITs usually defined according to the place of the incorporation and seat of the company. The question

arises that whether the company locally incorporated with native investors can be treated as a national of

the other contracting parties under the BITs regime and the Convention. Article 25 (2) b does provide that

the legal entity through which the investment was made may be considered to be a national of anther

contracting state when it is subject to foreign control. 88In the Amco v. Indonesia Case, the tribunal held

that PT Amco, registered in the Indonesia was an Indonesian company under foreign control because it

was clear from the documents in which the consent to arbitration was made.89 With respect to the extent

of foreign control, the tribunal in Vacuum V. Ghana Case determined that the foreign control does not

require, or imply, any particular percentage ownership. It found that only 20 per cent of the shares of

Vacuum were in foreign hands and 80 per cent in local hand and the same situation was somehow

reflected in company’s management. 90 Therefore the tribunal concluded that ICSID did not have

88 Julian D.M. lew: ICSID Arbitration: special Feature and recent Developments, Arbitrating foreign investment disputes Arbitrating foreign Investment Disputes / ed. by Norbert Horn, Kluwer Law International, 2004., P. 267-282, 270. 89 Amco Asia Corporation and Others V. Republic of Indonesia, ICSID Case No. ARB/81/1. 90 Omar E.GARCIA-BOLIVAR, Foreign Investment Dispute under ICSID, A Review of Its Decisions on Jurisdiction, 5 J. World Investment & Trade 187, 2004.

26

jurisdiction. The decisions may be enlightening for Chinese investors to take the factor of foreign control

into account when they are planning to establish a joint venture with the local entities in the host state,

assessing to what extent that the investment could be covered by the BITs and ICSID regime.

Consent

In accordance with Article 25 of the Convention, ICSID has jurisdiction over the dispute only the parties to

the dispute consent to submit such dispute to the Center for settlement. Consent of the parties is the

cornerstone of the jurisdiction of the Centre. 91 In certain circumstances, a state consents in advance to

submit dispute to ICSID arbitration, this consent is not complete until the investor has accepted.92 In BIT

regime, the contracting states usually articulate that both contracting parties unconditionally and explicitly

consent to submit the investor-state dispute to arbitration including ICSID. Since China-Botswana BIT, the

unconditional consent has been concluded in many following BITs, therefore the host states under such

BITs have given unconditional consent to submit the dispute to ICSID in accordance with Article 25 of the

Convention. The question arises when it comes to some China BITs in which unconditional and explicit

consent has not been concluded. Further discuss regarding applicability of BIT will be provided in next

chapter.

Waiting periods

Almost 90% of the treaties with investor-state dispute resolution provisions require that the investor

respect a cooling-off periods before bringing a claim,93 and such claim includes both claim before a

competent domestic court and the international arbitration institution. Nearly all China BITs adopt the

waiting period with six months in order to set out a waiting period for disputing partiesto negotiate

amicably aiming to reach a settlement agreement. Waiting periods gives rise to issue that whether a

claimant is barred from the international arbitration jurisdiction where the claim has been made within

the waiting period. In accordance with Article 21. 2 (b) of China-Canada BIT, a disputing investor may

submit a claim to arbitration only if at least six months have elapsed since the events giving rise to the

claim, thereby establishing a condition for submission a claim to arbitration. That is to say the phrase “only

if” refers to a mandatory period barring disputing investor’s access to arbitration. However, the tribunal in

Lauder v. Czech held that six month waiting period is not a jurisdictional provision and in the circumstances

91 Report of the Executive Directors on the Convention 92Omar E.GARCIA-BOLIVAR, Foreign Investment Dispute under ICSID, A Review of Its Decisions on Jurisdiction, 5 J. world Investment & Trade 187, 2004. 93 Pohl, Joachim and Mashigo, Kekeletso L. and Nohen, Alexis, Dispute Settlement Provisions in International Investment Agreements: A Large Sample Survey (November 1, 2012). OECD International Investment Working Paper No. 2012/2. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2187254

27

of this case, six months amount to an unnecessary, overly formalistic approach which would not serve to

protect any legitimate interests of the Parties. 94 From the investors’ perspective, it is not an optimal option

to directly ignore the cooling-off period because the specific circumstances as mentioned in the Lauder v.

Czech decision are too broad to define from case to case. As stipulated in China-Netherlands BIT, the six