Photojournalists' Role Expands At Most Daily U.S. Newspapers

Transcript of Photojournalists' Role Expands At Most Daily U.S. Newspapers

74 - Newspaper Researeh Jottrnal • Vol. 34. No. 1 • Winter 2013

Photojournalists' Role ExpandsAt Most Daily U.S. Newspapersby Arthur D. Santana and John Russial

A majority of photo editors from U.S. newspapers ofmore than 30,000 report photo staff members now shootand edit video as weii as provide photo gaiieries andsiideshows; yet most have accepted their expanded roie.

X hotographers have traditionally been defined as a profession by theequipment they carry. Newspaper photojournalists carry cameras. But whatof the news photographer who, in addition to a still camera, carries a videocamera, a tripod, a microphone, a digital recorder and a pack filled with a hostof ancillary equipment, including a laptop, lights, videotapes and cords? Muchhas been written about news reporters, the "backpack journalists" on the frontlines of the new digital age of convergence. Less consideration has been givento photojournalists, who have assumed the lead role in shooting news video.^

Newsrooms across the country have assumed video to be a natural pro-gression of the jobs photojournalists already do—capturing compelling imageswith a trained eye is at the root of the skill photographers bring to the news-room. The new reality of online journalism makes photojournalists a uniquehybrid—tethered to more electronic equipment than any other member of thenewsroom. As Bock put it: "It is this blending of body and machine that setsphotographicnewswork apart from other forms of journalism."- Whether a newphotographer or a retrained one, these news workers have been newly dubbed"broadband journalists"—photographers who work directly on the Internet,whether with video for newspapers, stills for Internet sites or other variations.'

And photojournalists find themselves bearing these news responsibili-ties in an era of significant journalism turmoil. Cutbacks, layoffs and buyouts

Santana is an assistant professor in the Jack J. Valenti School of Communication at theUniversity of Houston. Russial is an associate professor in the School of Journalism

and Communication at the University of Oregon.

Sautana and Russial: Photojoimialists'Role Expands - 75

have become commonplace. The latest figures show that roughly 15,000 full-time newsroom jobs disappeared in the past three years, the total falling from55,000 to roughly 40,000, according to Rick Edmonds of the Poynter Institute."Translation: newsrooms have slirunk by 27 percent in three years. According tothe American Society of Newspaper Editors Newsroom Employment Census,^the category "photographer/artist/videographer" in U.S. daily newspapersdeclined from 5,566 in 2008 to 4,895 in 2009, a drop of 12 percent.

Still, new technical demands are being hefted onto these journalists. With newresponsibilities comes new training and new demands of the photojournalists'time—time out of the field. The added workload, however, might not translateinto a less-rewarding job. Photojournalists have proven to be resilient, opento changes and technological transformations. Economic forces have meant asteady drumbeat of news stories lamenting the death of photojournalism. Thoseeconomic forces are spurred, in part, by the new reality of the immediacy ofthe Internet. Jolly wrote:

Pictures and video snapped by amateurs on cellphones are posted towebsites minutes after events have occurred. Photographers tryingto make a living from shooting the news call it a crisis.^

Indeed, the sheer ubiquity of cameras today, embedded in cell phones, forexample, has drasfically altered the landscape of photojournalism, democratiz-ing it on one hand while deprofessionalizing it on the other. The Internet hasmade amateurs into instant journalists, reinforcing, perhaps, the importance ofprofessional photojournalists in the digital age. As Newton points out:

the view that anyone can be a.. .photojournalist speaks to the under-lying assumptions...that there is a fact-based truth to be discovered. . . and . . . ignores the probability that a trained observer may seemore and gather and recall more than someone who does not 'practice'observation as a core method of everyday life....'

The real workaday world of these broadband journalists creates scenariosnever before experienced by journalists. A photojournalist who has a still cameraslung over one shoulder and a video camera over the over, must decide in aninstant—in what Henri Cartier-Bresson called the "decisive moment"—whichto use. Tim Hetherington, photographer and filmmaker, said the decision isessenfially "intuifive" based on the immediate circumstances.** These momentsare happening more and more, as photojournalists embark on new assignmentsevery day.

This study, based on a national survey of newspaper photo editors, ex-plores the changing nature of the role of newspaper photojournalists and theirjob satisfaction in a newsroom atmosphere of convergence and cutbacks. Thisresearch addresses assumptions—held by new and future journalists as well

76 - Nezospaper Research Journal • Vol. 34. No. 1 • Winter 2013

as the researchers who study them and the instructors who teach them—aboutwho in the newsroom is doing the added work of multimedia production. Italso addresses an area not thoroughly explored in the scholarly literature: howthat added work relates to job satisfaction.

Literature ReviewThe transformation occurring

in newspaper photo departmentsacross the country has beenexplored very little in scholarlyliterature; anecdotal evidence offhe impact of technology on pho-tojournalism is most often foundin trade journals.

Convergent Internet technol-ogy has compelled newspaperphotographers around the coun-try to add to their growing list ofjob skills. They now need to beproficient in new areas, includingvideo shooting and editing andaudio. Bock explains:

Wliilephotojonrnalistsliavelong been exhorted to be'storytellers,' broadbandjournalism is forcing theimage-makers to actuallyuse words in that storytell-ing.' •

Photographers speakof work-ing collaboratively with reporters. Melissa Lyttle, of her experience with a St.Petersburg Times reporter, wrote:

With our close collaboration, I felt for the first time as a photographerthat I was xmrking with a luriter who really wanted to hear what Ithought about the story.'"

The importance of photographs as sources of informafion had already beenrealized in the mid-1850s when documentary photographers set out to visuallyexplore the Western frontier or capture images, as photographer Mathew Brady

About 42 percent of thephoto editors reportedthat their papers had staffvideographers. Largerpapers were more likely tohave videographers thanmid-size or smaller papers.Photographers also handledmost of the video editing,according to the photoeditors.

Santana and Russial: Photojournalists'Role Expands - 77

famously did, of the Civil War from a social reportage point of view." Fromthose early beginnings, photojournalists have constructed people and eventsin their pictures. Those still images are "reminders of shared experiences thatcontribute to a sense of national identity."*^ Still, photojournalists have notalways enjoyed equal status among reporters.

During the 1920s and 1930s—^during a time when technological changesallowed the dissemination of news on a scale that had never been available—reporters generally harbored unflattering opinions about photographers. Theywere mistrustful of photographers and threatened by how they were alteringthe reporting process. When reporters themselves took it upon themselves topick up a camera,

. . . professional practice was affected, as it lias been with every tech-nological change in the newsroom since the telegraph and telephone.^^

Through the decades, as photographs became a more important source ofnews reporting, photographers and the job they did were more appreciated,and with each passing decade so too came new technological advances in pho-tojournalism. The introduction of flash photography in the 1920s, for example,allowed for images of interiors. The handheld Speed Graphic camera offeredportability, and the 35mm camera offered greater speed and flexibility." Onthe horizon were TLRs and SLRs of the 1950s and instant cameras of the 1960s.Trade journals of just 12 years ago speak of how the impact of convergence wasjust starting to be felt and how many staff photojournalists were not requiredto shoot video. '

News photographers have traditionally been charged with a host of dutiesrevolving around the making of photographs. Imaging functions, such as scaling,cropping and image adjustments, have usually fallen to members of the photoor graphics department—duties that photo editors have said has taken timeaway from the task of shooting or planning coverage."' Historically, newspapershave found it difficult to have photographers concentrate solely on makingpictures. Photo editors know that it is the unencumbered photographer whospends the majority of his or her time in the field. At the same time, advancesin technology and the ever-changing dynamic of a Web 2.0 newsroom haveplaced new demands on the news photographer.

Fourteen years ago, research from a national survey concluded that photoeditors considered video skills relatively unimportant and foresaw them asbeing only slightly more important for the near future. ^ They found that whilephoto editors placed a heavy emphasis on the need for new photojournaliststo know how to shoot, edit photos and provide accurate capfion information,they placed much less emphasis on the need for video skills both then and fiveyears hence. *

In 2008, the vast majority of newspaper websites featured video, accordingto an online survey of Newspaper Association of America member newspapers.

78 - Nexuspaper Research Journal • Vol. 34. No. 1 • Winter 2023

Photographers were most responsible for shooting video and heavily respon-sible for editing video."

While added duties are par for the course in the new digital age of journal-ism, photographers have generally accepted the changes. When asked in 2000if they felt that digital imaging—which included working on a computer—increased their workload, photojournalists agreed that it had but that it hadnot overly hindered the quality of their work. " But the increasing demand forphotojournalists to learn how to shoot video has not been without its share ofhand wringing. "It's not that I don't want to shoot video," said James DeCamp,staff photographer with The Columbus Dispatch in 2000, "but still photographywill be compromised."-^ It can cut both ways; online journalist Ken Sands men-tions that some videographers at newspapers complain about being requiredto shoot still photos for the paper.--

The increased workload has also long been on the minds of photo editors,who fear that photojournalists who must adapt to changing technologies mightbe stretched too thin. Previous research has concluded that while there had beena shift in work and increase in workload, there was less staff to support theextra work—essentially, photojournalists were among those most often askedto do more with less.'^ Even the advent of digital photography, which is lessexpensive and less labor-intensive to produce, nevertheless engenders, somesay, an emphasis on productivity instead of quality. "Content and quality aresuffering so that we can feed the beast," said Joe Elbert, assistant managingeditor of photography of The Washington Post.'^*

Coupled with the pressure to learn a new skill, experienced journalists fearthey will be out of a job if they do not learn the latest software. Photographytrade journals of 12 years ago speak bluntly of ways in which future journalistswill be successful: by learning the new forms of technology.^' Research in 2007exploring what photo editors and managers want photo students to learn asthey leave college and enter digitized newsrooms concluded that a proficiencyof the fundamentals—including photo editing, writing, critical thinking skillsand how to conceive and tell a story—still apply. " Editors also spoke of a needfor new photojournalists to grasp technological skills, stressing, for example,multi-platform convergence such as still, video and multimedia technologies.^^That si udy, based on a national survey, further concluded:

. . . the modern visual jotirnalism graduate would benefit from aneducation that exposes students to. ..desktop pnblisliing, multimediaauthoring and design, loeb page design and layout, video editing,database management, photo editing, scanning and optimizingmultimedia ^^

For photojournalists, video editing might present a greater burden thanshooting, given the complexity of video editing software and the time involved.

Santana and Rttssial: Photojonrnalists'Role Expands - 79

Several surveys have found that online staff members, including producers,have significant responsibility for editing video.^'

Jobs and Job Satisfaction

Employees can view the addition of tasks as either a positive or negativeexperience depending on the nature of the tasks and workplace conditions.The tasks may be seen as simply extra work (job-enlarging) or more rewarding(job-enriching). Studies of job satisfacfion dating to sociologist Blauner's studyof the printing industry"*" and Herzberg's work-" have looked at the concept as acombination of different types of factors. Intrinsic factors, according to Blauner,are related to the nature of the work itself. Whether a job is challenging and of-fers variety and new opportunities are intrinsic factors. Extrinsic factors, whichHerzberg called "environmental," have more to do with conditions of work,such as wages and job security. Theorists have disagreed about how to concep-tualize the interplay of these factors, ^ but in general both types are important,and for skilled and creative workers, intrinsic factors can be very important.In a study of photojournalists' satisfaction in the early days of digital shooting,Roehl and Moreno found a mix of extrinsic and intrinsic factors were relatedto job satisfaction.^' The opportunity to learn new things was a key intrinsicfactor. Yaschur found that job satisfacfion among photojournalists was relatedto autonomy and a sense that the quality of their work was improving.'^

Studies of U.S. journalists have historically found fairly high job safisfac-tion, although the trend has been somewhat downward since the first majornational study was done in 1971.'^ The latest study in the American Journalistseries in 2002 found that a variety of factors predicted higher satisfaction. Paywas one factor, but others were intrinsic factors such as perception of autonomyand infiuence as well as a belief that the quality of journalism was increasing attheir organizations.'*" Recent studies have indicated relatively low job satisfac-tion among copy editors, especially at smaller papers'^ and among city editors.'^

Research Questions

One can expect that extrinsic factors, including the impact of staff cutbacks,will have had a depressing effect on job safisfaction for most journalists. Eorphotojournalists, who are major contributors to newspapers' online future,it is worth examining whether intrinsic factors remain important or whetherconditions of work and workload are changing that equation.

This study will examine the following questions:

RQl:How extensive are the new responsibilities of newspaper photographers?

80 - Ne^vspaper Research Journal • Vol. 34. No. 1 • Winter 2013

RQ2:Do photo editors feel that photo staff workload has increased?

RQ3:To what extent are photographers satisfied in their jobs?

RQ4:How do video duties relate to job satisfaction?

RQ5:What intrinsic aspects of the job relate to job satisfaction?

MethodPhoto editors from U.S. newspapers of more than 30,000 circulation were

sampled and surveyed by mail as part of a wider study of newsroom depart-ments and skills in the online era.^' The sample was drawn from newspaperslisted in Editor & Publisher Yearbook.*" The papers were divided into threecirculation groups: more than 100,000,50,000 to 100,000 and 30,000 to 50,000; 70papers were randomly selected from each group to allow for size comparisons.More than half of daily newspaper circulation is represented by papers greaterthan 30,000 circulation.

Names and titles were gathered from online staff lists, which many news-papers publish, and by phone, when the information was not available online.Staff members who function as photo editors are known by different tides atsome papers, for example as visual editor, chief photographer or director ofvisuals. The first mailing was sent in late summer 2009; a second was sent abouta month later. The response rate from the two mailings was 53.8 percent—atotal of 113 photo editors. The responses were balanced across groups, with thesmall-newspaper category slightly underrepresented at 31.5 percent.

The photo editors were asked quesfions about video work at their papers,including whether photographers shot video as well as stills, whether the paperhad videographers on staff and which department was most responsible forvideo. Other quesfions asked about photographers' workload and job safisfac-tion and whether photo jobs had been cut. To address various characterisfics ofhow the job has changed, respondents were asked to what degree they agreedwith a set of statements adapted from a list used in a study of photographerworkload and satisfaction in 2000."" That study examined intrinsic motivationsof photojournalists before most papers were shooting digitally or producingvideo. The list was updated to reflect changes that have occurred since thatfime, and responses were recorded on a 5-point scale from "strongly agree" to"strongly disagree."

• Photo deadlines have improved• Reporters shoot good video

Santana and Russial: Photojournalists'Role Expands - 81

Photographers have less control of their workPhotographers have more opportunitiesPhoto work is more routineVideo duties limit the time available for still photographyProduction is a higher priorityPhotographers must work harderQuality of visuals has improvedPhotographers have more flexibilityPhotographers face more limitsDesk editors have more control of visualsVideo duties have made the job more interestingPhotographers have more autonomyComputer problems take more timePhotos are presented well onlinePhotographers switch easily between video and still work

Photo editors were also asked how much video their newspaper did basedon a five-point scale of "not at all," "mostly on special reports or major projects,""on a few stories each week," "on a few stories each day" or "on many stories."They also were asked who edited video and audio clips.

Findings

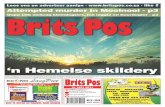

How extensive are ptiotograptiers' new responsibiiities?The answer to the first research question is that they are considerable. Sixty

percent of photo editors reported that all photographers at their papers shootvideo. [See Figure 1] An additional 36 percent said that some photographers at

Figure 1Primary Responsibility for Video Work at Newspapers

Who does most video work at your paper?

Photographers ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ H ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ l

staff videographers ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ H

MM reporters ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ H

Print reporters ^ ^ ^ ^ H 1

Other oniine staff ^ ^ ^ H

•IM

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Percentage of papers

82 - Neiospaper Research Journal • Vol. 34. No. 1 • Winter 2013

Figure 2Video Editing Responsibilities at Newspapers

Who usually edits video at your paper?

photographers

Staff videographers

10 20 30 40 50 60 70

Vo of papers [multiple responses allowed)

their papers do. Only four out of 111 photo editors responding to the questionsaid staff photographers did not shoot video. In responding to a question ask-ing who shot the most video at the paper, nearly half said photographers did,followed by staff videographers, multimedia reporters, "other online staff" andreporters. About 42 percent of the photo editors reported that their papers hadstaff videographers. Larger papers were more likely to have videograpliers thanmid-size or smaller papers (x-=8.56, p=.O14). Photographers also handled mostof the video editing, according to the photo editors. [See Figure 2] Sixty-eightpercent of the respondents said photographers edited video. Videographers (27percent), online producers (25 percent) and multimedia reporters (24 percent)followed. These results are somewhat different from the NAA's study in 2008,^which reported the top two categories as online staff (72 percent) and photogra-phers (59.8 percent). Category definitions and other methodological differencesmight explain the discrepancy with the findings of this study*^

In addition, photo staff members are largely responsible for photo galleriesand siideshows with audio. Almost 70 percent of photo editors said siideshowswere the exclusive responsibility of photo staff. The next highest category (at 16percent) said photo staff and online staff were both responsible for siideshows.All of these responsibilities are new, meaning they did not exist before onlinejournalism.

On RQ2, 83 percent said woricioad had increased, 10 percent said it had stayed thesame, and ahout 6 percent said it decreased.

Some of the workload increase is likely related to staff cutbacks and someto added responsibilities. Eighty percent of photo editors reported that photo

Santana and Russial: Photojoimtalists'Role Expands - 83

Table 1

Job Considerations Correlated with Job Satisfaction

Job factors

Photographers have more flexibilityQuality of visuals has improvedPhotographers have more opportunitiesPhotographers face more limitsPhoto work is more routinePhotographers switch easily between video and stillsProduction is a higher priorityVideo duties limit the time available for still photographyDeadlines have improvedDesk editors have more control of visualsPhotographers have more autonomyVideo duties have made the job more interesting

.450

.417

.404-.324-.303.290-.271-.229.226-.216.202.179

<.OO1<.OO1<.OO1.001.001.002.004.018.019.023.033.062

staff had been cut compared with 95 percent who said reporters had been cut,and 84.5 percent who said copy editors had been cut.

RQ3 asked: How satisfied are piioto staff members? Overait, ttiey are somewfiatdissatisfied witli tiie Job.

On a 5-point scale with 1 being very dissatisfied and 5 being very satisfied,the mean was 2.5—halfway between "somewhat dissatisfied" and "neutral."Photo staff members at smaller papers are less satisfied than their counterpartsat larger ones. A correlation between circulation and satisfaction returned aPearson r coefficient of .242, (p=.Oll).

R4 found tbere also is a moderate, significant correiation between job satisfactionand tbe amount of video done by a newspaper (r=.327, p=.OÛ1).

The correlation is posifive, meaning that the more video a paper produces,the more satisfied the photo staff. A partial correlation controlling for circulationreduced the correlation to .280, but it is still significant (p=.004). To examine thepossibility that this relationship might be related to the presence of videogra-phers on staff, a multiple regression analysis using existence of videographers

Table 2

Job Factors and Job Satisfaction—Stepwise Regression

Job consideration beta

Photographers have more flexibilityQuality of visuals has improvedPhotographers switch easily between video and stills

.304

.293

.212

.001

.002

.019

84 - Neiospaper Research journal • Vol. 34. No. 1 • Winter 2013

on staff as a dummy variable along with the amount of video produced andworkload showed only one significant beta—the amount of video produced(beta= .334, p=.OOl).

RQ5 found a number of intrinsic factors correiate significantly witb satisfaction.[See Tabie 1]

A positive correlation indicates that those who agreed with the statementreported higher job satisfacfion. A stepwise multiple regression analysis ofthe preceding variables found that several were significant predictors of jobsafisfacfion—flexibility, quality and switching easily between still and video(F (1, 90)= 15.6, p<.001, R-=.337, Adjusted R =.316). [See Table 2] The small N(93) on these items is problemafic and limits further analysis. Other variablesmight have been predictors if sample size had been larger.

Discussion and Conclusion

The growing emphasis on the online product has brought considerablechange to newspaper newsrooms. Enfirely new posifions have appeared,including online producers, multimedia reporters and videographers. Of thetraditional job categories at dailies, the position of photographer has changedthe most. Reporters now regularly write online-only stories and news updatesand some shoot video. But photo staff members have been asked fo take onthe bulk of video work, shoofing and much of the editing** and now have newresponsibilities for galleries and siideshows. Some also produce photo blogs,such as The Neio York Times lens blog.'' ^ All of fhis lands at a time when staff cut-backs in many positions, including photo, have added new workload pressures.

From these data, it appears photographers have generally accepted theirnew roles, and the new technical demands much as they accepted digital imag-ing and digital shooting a decade or more previously. The relationship betweenthe intrinsic factors and job satisfaction suggest that many photographers donot see video as job enlarging—as simply extra work. Respondents did indicatethat shooting video does limit the time available for shooting stills, but thosewho see video responsibilities as offering new opportunities and flexibilityin their jobs tend to be more satisfied. The finding that more producfion ofvideo at newspapers is related to greater satisfacfion among photojournalistsperhaps offers additional support for a conclusion fhat video work is mostlyseen as positive. Common sense might suggest that anything that contributeclto increased workload would lead to dissafisfaction. This research has found,however, that the addition of video fasks, even though it represents additionalwork, does not appear to make the job less safisfying. In facf, it appears that themore video done, the greater the safisfaction. This finding is worthy of note,given that newsroom tasks added through technological change have sometimesled to burnout and other deleterious impacts.

It is important to note that satisfaction among photojournalists overall is

Santana and Russial: Photojournalists'Role Expands - 85

not high. A decade ago, when newsroom staffing levels were near their peak, asurvey found photo editors somewhat satisfied.""* Perhaps it is no surprise thatphoto editors now report that staff members have shifted over to the unsatis-fied side of the scale. Buyouts, layoffs and givebacks are extrinsic factors thatno doubt depress job satisfaction in a number of ways, not the least of which isthrough an increase in workload. Photo staffs are small to start with, about 10percent of newsroom positions, according to ASNE annual surveys,*^ so even aloss of one photo job can have a big impact on those who remain. This impactis especially true at smaller papers, which reported lower satisfacfion over-all. A substantial majority of photo editors responding to this survey noted anincrease in workload. In fact, the percentage was so lopsided it made statisticalcomparison with satisfacfion moot. The scale used in this study was 3-point.Future researchers might consider creating a workload scale that allows formore nuance in reporting, such as 5- or 7-point.

The intrinsic factors matter as well. For creative professionals, the job isoften about more than pay and job security.*^ Intrinsic characteristics, such asautonomy, flexibility, control of the work process, new opportunities and theimportance of quality are vital. The results of this study show that intrinsicfactors such as autonomy are indeed important to photojournalists, as they arefor other journalists.'"

Limitations and SuggestionsThe 113 photo editors who responded were part of a much larger sample

of newsroom employees that focused on a variety of job characteristics acrossnewsroom positions and included other departments. A more extensive sampleof newspaper photo editors would allow for potentially more illuminatingmultivariate analysis. Subsequent studies could examine extrinsic factors suchas pay, job security and workplace conditions in combination with intrinsicfactors. It is more efficient to survey photo editors, who tend to be identifiedin sourcebooks such as The Editor & Publisher International Yearbook and inonline staff lists, and they ostensibly have a good idea what work is like at theirpapers, yet there could be differences among the rank and file. Surveying rankand file photojournalists would be a valuable next step.

It also would be useful to examine how video work is organized at news-papers that have videographers and whether the existence of videographers onstaff is viewed positively or negatively by photographers. One can speculatethat having video specialists would provide a level of in-house training tophotographers who have little or no experience with video, raising the qual-ity of the video done overall. Or it is possible that newspapers that have staffvideographers tend to create specializations within the visual arena—photog-raphers mostly shooting stills and videographers capturing the moving images.If so, photographers might see that specialization as a good way to organizework, or not, if it limited their opportunities and created a less-challenging

86 - Newspaper Research Journal • Vol. 34. No. 1 » Winter 2013

work environment. Whether newspapers offer video fraining or re-fraining tophotographers, especially during a period of financial cutbacks, is also worthexamining.

In anecdotal accounts, some photojournalists say they have willinglyembraced video and now consider it a part of fhe job. Others have raised con-cerns. This study suggests that for photojournalists, job enlargement and jobenrichment are both facets of fhe online world of work. Photo editors clearlyfeel fhat workload has increased, and at least some of fhaf increase is the resultof added tasks, particularly video. Some, too, is most likely the result of sfaffcuts. But despite the added burden, it appears that photojournalists by and largehave not only accepted new video duties but view them as enriching their job.

Notes1. Beth Lawton, Digital Edge Report: Newspapers'Online Video, an NAA Report on Current Practices

(Arlington, V.A.: Newspaper Association of America, 2008).2. Mary A. Bock, "Together in the Scrum," Visual Communication Qunrterh/15, no. 3 (August

2008): 174.3. Bock, "Together in the Scrum," 174.4. Rick Edmonds, "Newspapers, Summary Essay," stateoftliemedia.org, March 2010, <http;/ /

stateofthemedia.org/2010/newspapers-summary-essay/> (March 25, 2010).5. ASNE, "Newsroom Employment Census (2009a)," asne.org, 2010, <http://asne.org/

key_iniüatives/diversity/newsroom_census/table_c.aspx> (April 14, 2010).6. David Jolly, "Downturn in Print Media Hurting Photojournalists," Tlie Neir York Times,

Aug. 11,2009, sect. B., p. 3.7. Julianne H. Newton, "Photojournalism," Journalism Practice 3, no. 2 (February 2009): 237.8. Geneviève Long, "The Rebirth of photojournalism," QiiiV/98, no. l,Oanuary/February 2010).9. Bock, "Together in the Scrum," 176.10. Melissa Lyttle, "PartnershipofPhotojoumalist and Writer," Nieinan Reports, Visual Journalism

64, no. 1 (spring 2010): 43.11. Bonnie Brennen and Hanno Hardt, Picturing the Past: Media, Histoiy, and Photography

(Urbana, I.L.: University of Illinois Press, 1999).12. Brennen and Hardt, Picturing the Past: Media, Histon/, and Photography, 15.13. Brennen and Hardt, Picturing the Past: Media, History, and Photography, 19.14. Brennen and Hardt, Picturing the Past: Media, History, and Photography.15. Michelle Lieberman, "Convergence: Talk of Conference," Neii'S Photographer 55, no. 9

(September 2000): 17.16. Lieberman, "Convergence: Talk of Conference."17. John Russial and Wayne Wanta, "Digital Imaging Skills and the Hiring and Training of

Photojournalists," Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 75, no. 3 (autumn 1988).18. Russial and Wanta, "Digital Imaging Skills and theHiring and Training of Photojournalists."19. Lawton, "Digital Edge Report: Newspapers' Online Video, an NAA Report on Current

Practices."20. John Russial, "How Digi tal ImagingChanges Work of Photojournalists," Newspaper Resenrc/i

Journal 21, no. 2 (spring 2000).21. Lieberman, "Convergence: Talk of Conference," 16.22. Ken Sands, "Vegas newspaper pulls plug on 7O2.tv after four months," Poynter.org, Oct. 15,

2009, <http://www.poynter.org/column.asp?id=31&aid=171773> (April 1,2010).23. Russial and Wanta, "Digital ImagingSkills and the Hiring and Trainingof Photojournalists."24. Lieberman, "Convergence: Talk of Conference," 16.

Santana and Russial: Photojournalists'Role Expands - 87

25. Lieberman, "Convergence: Talk of Conference," 16.26. Michelle I. Seeling, "What Photo Editors/Managers Want Photo Students to Learn,"

Neiospaper Researcli ]otirjial 28, no. 1 (ivinter 2007).27. Seeling, "What Photo Editors/Managers Want Photo Students to Learn."28. Seeling, "What Photo Editors/Managers Want Photo Students to Leam."29. Lawton, "Digital Edge Report: Newspapers' Online Video, an NAA Report on Current

Practi ces;" John Russial, "Growth ot'Multimedia Not Extensive at Newspapers," NfícsfínpcrRt'scíirc/iJournal 30, no. 3 (summer 2009); John Russial and Arthur D. Santana, "Specialization Still Favoredin Most Newspaper Jobs," Newspaper Research journal 32, no. 3 (summer 2011).

30. Robert Blauner, Alienation ana freedom (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1964).31.FrederickHerzberg, WorkaniifheNatiireofMaii (Cleveland, OH: World PublisliingCo., 1966).32. Susan Keith, "Copy editor job satisfaction lowest at small newspapers," Newspaper Research

journal 26, no. 2 (spring 2005).33. Janet E. Roehl and Carlos Moreno, "Digital photography and itsimpact on photojournalists'

job satisfaction," (paper presented at AEJMC Visual Communication Division, Phoenix, AZ, 2000).34. Carolyn Yaschur, "Photojournalists' Changing Job Responsibilities and Satisfaction: The

Impact of Range of Affect," (paper presented to the AEJMC Visual Communication Division,Denver, CO, 2010).

35. David H. Weaver, Randal A. Beam, Bonnie J. Brownlee, Paul S. Voakes and G. ClevelandWilhoit, Tlie American journalist in the 21st Ceiituri/: U. S. Nezus People at the Daivn of a Neiv Millennium,Lea's Communication Series (Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, 2007).

36. Weaver et al., Tlie American journalist in the 21st Century: U.S. News People at the Dim'ii of aNew Millennium, 113.

37. Keith, "Copy editor job satisfaction lowest at small newspapers."38. Charles St. Cyr, "Study of city editors raises concern for job satisfaction," Newspaper Research

journal 29, no. 1 (winter 2008).39. Photo editors were chosen rather than photographers because photo department managers

typically are listed in directories and online staff lists whereas other photo staff members oftenare not. At many papers, especially small and midsize papers, there is little functional differencebetween a photo editor and a photographer, unlike, say, the difference between a city editor and cityside reporters. Photo editors often shoot and edit photos as well as make assignments and manage.

40. David Maddux, ed., Editor & Publisher International Yearbook 2006, 86th ed. (New York:Editor & Publisher, 2006).

41. Russial, "How Digital Imaging Changes Work of Photojoumalists."42. Lawton, "Digital Edge Report: Newspapers' Online Video, an NAA Report on Current

Practices."43. The NAA's 2008 survey found that photographers were most responsible for shooting

video (86.2 percent), followed by reporters (73.5 percent) and online staff (64.6 percent; Lawton,2008). Most video editing was done by online staff (72 percent), followed by photographers (59.8percent). The NAA did an online survey of the "top digital contact," at 1,117 member dailies andhad a response rate of 19 percent. Slightly more than half of the N AArespondents were in the 50,000and under circulation category. The survey reported in this paper randomly sampled photo editorsof newspapers greater than 30,000 circulation. The NAA survey lists "reporters" as a category; itdid not break out print reporters and multimedia reporters as separate categories. Multimediareporters, who have significant responsibility for video editing, might also have been combinedinto the NAA "online staff" category.

44. Russial, "Growth of Multimedia Not Extensive at Ne\vspapers."45. See http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/46. Russial, "How Digital Imaging Changes Work of Photo Journalists."47. ASNE, "Newsroom Employment Census (1978-2011)," asne.org, (April 7, 2011) <http://

asne.org/key_initiatives/diversity/newsroom_census/table_d.aspx> (May 12, 2011).

88 - Newspaper Research Journal • Vol. 34. No. 1 • Winter 2013

48. Teresa Amabile of the Harvard Business School is one of many scholars who have studiedcreativity and intrinsic motivation in the workplace. See, for example, Teresa M. Amabile, Creativityin Context: Update to the Social Ps\jcliotog\/ ofCreatiinty (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996).

49. Weaver et al., Tlie American Jonrnalist in the 23sf Century: U.S. Nm's People at Dmtni of aNeiP Millenninm.

Copyright of Newspaper Research Journal is the property of Newspaper Research Journal and its content may

not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.