Ongoing relationships with a personal focus: mothers' perceptions of birth centre versus hospital...

Transcript of Ongoing relationships with a personal focus: mothers' perceptions of birth centre versus hospital...

Karen L.Coyle RN, RM,BHlthSc(Nur), MN, FamilyBirth Centre, King EdwardMemorial Hospital, BagotRoad, Subiaco,WA,Australia 6008

Yvonne Hauck BScN,MSc, PhD, RM, EdithCowan University, Schoolof Nursing & Public Health,Pearson Street,Churchlands,WA,Australia 6018E-mail:[email protected]

Patricia Percival PhD,FRCNA, RN, RM

Linda J.KristjansonMN,PhD, RN, BN, Professor,Faculty ofCommunications, Healthand Science, Edith CowanUniversity, Pearson St,Churchlands,WA,Australia 6018

(Correspondence to KC)

Received 31May 2000Revised 6 October 2000Accepted 22 February2001Published online 31May2001

Ongoing relationshipswitha personal focus: mothers’perceptions of birth centreversus hospital care

Karen Coyle,YvonneHauck,Patricia Percival andLinda Kristjanson

Objective: to describewomen’s perceptions of care inWestern Australian birth centresfollowing a previous hospital birth.

Design, setting and participants: an exploratory study was undertaken to examine the careexperiences of women fromthreeWestern Australian birth centres.Datawere obtainedfrom17 womenwhose interviewswere audio-recorded and transcribed.The researchfocused uponwomen’s perceptions of their recent birth centre care as compared toprevious hospital care during childbirth.

Findings: four key themes emerged fromthe analysis: ‘beliefs about pregnancy andbirth’,‘nature ofthe carerelationship’, ‘care interactions’and ‘care structures’. The themesof ‘careinteractions’and ‘care structures’ will be presented in this paper.Care interactions refer towomen’s opportunities to develop rapport with their carers.Care structures involved theorganisational framework inwhich carewas delivered. The ¢rst two themes of ‘beliefsabout pregnancy andbirth’and the ‘nature of the care relationship’ were discussed in aprevious paper.

Keyconclusions and implications for practice: di¡erences in opportunities for careinteractions and care structureswere revealedbetween birth centre andhospital settings.Ongoing, cumulative contactswithmidwives in the birth-centre setting were stronglysupported by women as encouraging the development of rapport andperception of ‘beingknown’as an individual. Additionally, care structures tailored towomenwere advocatedover the systematised, fragmented care found in hospital settings. & 2001HarcourtPublishers Ltd

INTRODUCTION

During the 1990s Australian maternity services

followed trends in the UK and developed models

of care which provided women with continuity of

midwifery care (Brown & Lumley 1998). In the

UK, the Changing Childbirth Report has pro-

vided clear direction for the modification of

maternity services, one of the key elements being

continuity of carer (DoH 1993). These and other

recommendations have resulted in many inno-

vative models of maternity care being developed

throughout the UK (Shields et al. 1998). In

Australia, the major models developed to

Midwifery (2001) 17, 171^181 & 2001Harcourt Publishers Ltddoi:10.1054/midw.2001.0258, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on

address the fragmented maternity services of-

fered to women in the public health system have

been birth-centre care and team midwifery

(Brown & Lumley 1998, Waldenstrom & Lawson

1998). Both of these models incorporate mid-

wifery care across the childbearing continuum,

although they do not necessarily provide con-

tinuity of carer.

Continuity of ‘care’ versus continuity of ’carer’

is not clearly defined in the literature and has

caused some confusion when assessing alterna-

tive models of care. A systematic review to assess

efficacy of alternative models of maternity care

characterised by continuity of midwifery care

172 Midwifery

was recently undertaken by Waldenstrom and

Turnbull (1998). Seven randomised control trials

were included in this review (Flint et al. 1989,

MacVicar et al. 1993, Kenny et al. 1994, Rowley

et al. 1995, Harvey et al. 1996, Turnbull et al.

1996, Waldenstrom & Nilsson 1997). The review

highlighted the benefits of models that offer

continuity of midwifery care as reduced labour

interventions and increased levels of satisfaction

with care (Waldenstrom & Turnbull 1998).

Many of the trials do not indicate whether

women received care in labour from a known

midwife carer, so the findings may not necessa-

rily reflect continuity of carer, but rather a

continuity of philosophy of care.

In Australia, the birth-centre model is used by

about 5% of childbearing women (Waldenstrom

& Lawson 1998). Booking numbers in some

centres are nearing capacity and with the

increase in client numbers, midwife numbers

have also been increased proportionately. With a

focus on continuity of carer, some birth centres

are refining the model of care being offered by

modifying midwives’ work practices to minimise

the number of carers each client is exposed to

and guaranteeing a known carer at crucial times

such as during labour (Coyle 1997). This

refinement within the birth-centre context has

had limited evaluation, particularly from the

client’s perspective.

Consequently, the purpose of this study was to

address this issue and explore women’s percep-

tions of their experiences of care in the current

Western Australian birth-centre setting following

a previous hospital birth.

METHOD

The methods have been outlined in a previous

publication (Coyle et al. 2001). An exploratory

design guided by a modified grounded theory

approach involving the constant comparison

technique, was chosen to enable the principal

investigator to explore women’s perceptions of

the care they experienced in both birth-centre

and hospital settings (Strauss & Corbin 1998).

Women who had received care in three Western

Australian birth centres were interviewed. Data

collection involved face-to-face interviews with

seventeen women in their homes. The focus of

the interview was on women’s perceptions of the

care they received, not on their actual birth

experience. The interviewer explored women’s

perceptions of both their most recent care

experiences and previous hospital experiences.

Data were analysed from written narrative

communication transcribed from interviews.

Significant meanings of phrases, sentences and

paragraphs were coded and categorised into

groups allowing for the underlying meanings

within the communication to be identified within

the context of the entire interview (Field &

Morse 1990, Strauss & Corbin 1998).

Ethical approval for the study was given by

the university and hospital ethics committees.

FINDINGS ANDDISCUSSION

All seventeen participants in this study had

experienced at least one of their previous

pregnancies within a hospital setting, with one

participant also undergoing a previous home-

birth. All but one participant had achieved a

normal vaginal birth in their previous hospital

experience. Sixteen women were of Caucasian

background and one woman was of Maori

background. All participants had a current

partner. Participants’ ages ranged from 22 to

34 years with the number of children varying

from two to five. The socio-economic level of the

families varied across an income level of less than

$20 000 to greater than $50 000. The participants

represented a broad range of income levels as the

1996 census for Western Australia revealed that

the median household income was $34 000

(Australian Bureau of Statistics 2000). Eight

women had completed high-school requirements

and the remaining nine had achieved a post-

secondary qualification. Seven women described

their occupation as being in the service industry,

five as professionals and a further five solely

involved with home duties.

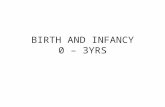

Participants shared their experiences of care in

both the hospital and birth-centre settings

providing a wealth of data about these two

different models of care. Final analysis of the

data resulted in the identification of four key

themes: ‘beliefs about pregnancy and birth’,

‘nature of the care relationship’, ‘care interac-

tions’ and ‘care structures’. Each of these themes

was comprised of two dimensions at either end of

a continuum, as outlined in Figure 1. The themes

‘beliefs about pregnancy and birth’ and ‘the

nature of the care relationship’ were presented in

a previous paper (Coyle et al. 2001). Care

interactions and care structures will be discussed

in this paper. Participant quotes will be utilised

to support the findings. A pseudo name is

presented following each quote and information

is given regarding parity, for example, [Ann, 2nd

baby].

Care interactions

The theme of ‘care interactions’ was defined as

opportunities that women have to develop

rapport with their carers. Interactions with

health-care providers were determined as either:

(a) cumulative interactions or (b) non-cumulative

interactions. Box 1 provides an exemplar of this

theme.

Fig. 1 Women’s perceptions of birth centre versus hospitalcare; ‘care interactions’ and ‘care structures’ addressed in thispaper

Ongoing relationships with a personal focus 173

Cumulative interactions

Cumulative interactions involved women having

the opportunity to develop an ongoing relation-

ship with their midwife. Participants were all

given the opportunity to be cared for by the same

midwife, or group of midwives, during their

pregnancy and birth. The cumulative contact

resulted in: (a) women comfortable with carers

and (b) women being known.

Women comfortable with carers – This feature

was defined as women feeling at ease with carers

with whom they had the opportunity to become

familiar. In the birth-centre model of care,

multiple exposure to the same midwives enabled

rapport to develop between women and their

carers. Many participants felt that the degree of

comfort they perceived was directly linked to the

number of contacts they had with the midwife:

The first [contact with one midwife] I was

nervous. The second time I was a lot more

relaxed and then the third time it was like, ‘hi

how are you going?’. It was a lot more

comfortable and I was able to open up a lot

more to her. [Lena, 2nd baby]

Communication was facilitated as a result of

being cared for by a familiar midwife; when

women developed rapport with the midwife they

were more likely to disclose information and

discuss concerns:

You feel a lot more relaxed and comfortable

and I think if you had things you want to talk

about at that time you can speak more about

what you want to or you feel more

comfortable than just meeting a stranger

walking in. [Diane, 5th baby]

Care provision by a ‘known’ midwife also

resulted in participants being able to focus their

attention and energy on the birth process,

instead of having to spend time developing a

relationship with an unknown carer:

. . .with the last two babies I knew the

midwives and all I had to do was

concentrate on myself and the labour. I

think that is what causes a lot of pain

during labour, your mind is elsewhere

thinking about other things rather than what

you are actually doing. [Maxine, 4th baby]

Moreover, women were more likely to trust and

listen to familiar midwives. Many participants

also described the development of closeness in

their relationship with known carers. This

relationship had a positive impact on the

woman’s birth experiences:

So I just think that besides having your mum

and your husband there who you can lean on,

you also feel like a closeness with the midwife

as well. It is a bond. You can’t explain what

that feels like. I really like it I think that is the

way it should be comparing with the other

births. [Diane, 5th baby]

Overall, the cumulative interactions experienced

by women in the birth-centre setting had a

positive effect on women’s care experiences.

These findings support those of other researchers

who have found that women develop such ‘closer

relationships’ when they have the opportunity to

know carers through continuous contact. In

particular, evaluations of other midwife-led

schemes confirm the importance of the relation-

ship that develops between women and midwife.

Creasy (1997) identified that continuity enhanced

women’s experiences in a number of ways. When

carers knew the women they were able to tailor

explanations to meet the woman’s needs. As in

the present research, women also reported that

they trusted the familiar carer above others.

Similarly, women in Morison et al.’s (1999) study

valued the rapport and trust they built up with

known carers during their home-birth experi-

ence. As well, most of the midwives in Harding’s

(2000) research felt their clients trusted them

when they worked together in a community

continuity of care scheme.

The existence of a ‘closer relationship’ with

known carers in the present research was also

174 Midwifery

confirmed by Sandall (1997). One of the critical

factors in midwives’ satisfaction with continuity

of carer schemes was this special relationship

with women. Moreoever, both women and

midwives in Pairman’s (1998) New Zealand

study felt they became ‘friends’ and ‘partners’

with each other when a relationship was devel-

oped through continuous contact. Finally, eva-

luation of the One-To-One Scheme in the UK

suggested that the role of the midwife in

continuity of carer schemes may have extended

past conventional boundaries (McCourt & Page

1996). In particular, midwives were perceived to

be providing women with more generalised

pregnancy support. Women also reported feeling

closer to their ‘named’ midwife than to other

health professionals.

Women being known – This second feature of

the dimension of ‘cumulative interations’ re-

ferred to as being known was described as

women’s perceptions that they felt understood by

the midwife. Their preferences and past experi-

ences were considered in the care relationship.

All participants had experienced continuity of

carer in the birth-centre setting; being cared for

in labour by a midwife they had met at least

twice during their pregnancy. Women found it

beneficial to be cared for by someone who knew

their history and past experiences:

She [midwife] knew what I had been going

through with the first pregnancy and the

birth. She knew everything, what I was scared

of and all of those things. She knew exactly

what I wanted, I didn’t have to tell her. [Teri,

2nd baby]

Discussion of birth preferences before the birth

allowed women an opportunity to inform the

attending midwife of their wishes:

. . . she [midwife] knew exactly what I wanted

before I even went in there, so when I was in

labour she knew exactly what I wanted.

[Ruth, 2nd baby]

. . . and she [midwife] knew how we felt about

intervention and drugs . . . that was a direct

benefit of her having had so much interaction

with us along the way. [Carol, 2nd baby]

Box 1 Exemplar of theme: care interactions

Care interactions

The opportunities women have to develop a rapport with carers

Dimensions: cumulative interactions

Women provided opportunity to develop an ongoing relationshipwith themidwife

Features Def|nition Exemplar

1. Women comfortablewith carers

Women feeling at easewith carers they have hadthe opportunity tobecome familiar

. . . it was important to have someone I kneweven though she [midwife] wasn’t a close friend.It was someone forme tomake contact with andfeel comfortablewith. [Ann, 2nd baby]

2. Women beingknown

Women’s perceptions ofbeing understood by themidwife and that theirpreferences and pastexperiences wereconsidered.

It was someonewho knewme, knewmyprevious experience.When I was delivering insecond stage, she [midwife] kept saying it is notgoing to be the same as the last one because sheknew howmuch that botheredme.[Mary, 2nd baby]

Dimension: non cumulative interactions

Interactions with carers which do not result in an ongoing relationship

Features Def|nition Exemplar

1. Lack of rapportwith carers

Women being unable tofeel at easewithunfamiliar carers.

. . . then therewould be a di¡erent one (midwife).And shewould do something di¡erent as well.And just as I would try to get used to onewayanother onewould come in and of course shewould have di¡erentmethods and di¡erentways.[ Jodi, 2nd baby]

2. Women beingunknown

Carer’s lack of knowledgeabout women’s pastexperiences and birthpreferences.

I hadwritten a birthplan for whenmybaby wasborn and quite a few things I hadwritten on thebirthplanweren’t even really looked at. . .and therewere little things thatmaybewould have rundi¡erently with the birth. . . [Kathy, 4th baby]

Ongoing relationships with a personal focus 175

Many participants were eager to have their

‘named’ midwife carer present at the birth. As

one client outlined: ‘I really did want my own

midwife to be there because she knew me and she

knew how I wanted to give birth.’ [Maxine, 4th

baby]. Known midwives were also able to

determine how much support individual women

needed. Some women required minimal physical

input from the midwife: ‘The midwife very much

played the outer circle but came in as required.

But, not like doing lots of encouragement, I had

people for that and really appreciated that’

[Vivian, 3rd baby].

Other women needed a large amount of

physical and psychological support from the

midwife. Another participant described how the

birth-centre midwife provided individualised

support for her needs:

. . . she [midwife] was talking me through and

very often during the contractions I had to

hug her, to hold her, and she would look right

at me and say ‘you can do it, you can get

through it’. . . . she was like my tower, when I

look back on the birth, that was where my

strength was. My husband was not able to

provide that for me. He knew that. [Mary,

2nd baby]

Being known by the midwife also facilitated

participants’ perception of their ability to be in

control of their birth experience:

Having met her [midwife] before and

discussing what we would like to have

happen and the feeling that she was putting

me back in control, that really made a big

difference. Rather than the doctor being in

charge. [Ann, 2nd baby]

Overall, women perceived many positive benefits

when they had the opportunity to be cared for

throughout pregnancy and birth by a familiar

midwife. In particular, having the opportunity to

be cared for by a known carer throughout labour

was highly valued by those who experienced it.

These positive benefits of continuity of carer,

particularly during the birthing period, added

further evidence to the findings of a recent

Australian population-based survey undertaken

in Victoria (Brown & Lumley 1998). The research-

ers reported a strong correlation between satisfac-

tion and knowing the midwife prior to labour. In

another Australian study (Morison et al. 1999),

couples who birthed at home felt the ongoing care

from one midwife throughout the pregnancy, birth

and postnatal period was critical.

Other researchers have also emphasised the

benefits experienced by women who are able to

‘get to know’ the midwife/carer. For example, a

British grounded theory study of midwife-led

care by Walker et al. (1995) identified that

perceptions of support were enhanced when the

woman received care from a known carer;

someone they trusted and had confidence in.

Similarly, McCourt and Page (1996) identified

that being cared for throughout pregnancy and

birth by a familiar midwife resulted in the

midwife understanding the women’s individual

needs. British women in both this latter study

and in Garcia et al.’s (1998) research, felt more

confident and supported when they knew the

midwife. An interesting finding in Brown et al.’s

(1994) Australian survey was that women who

saw a private obstetrician throughout the an-

tenatal period were more satisfied than women in

the public hospital system who saw different

carers. However, this satisfaction did not extend

to the birth. Additionally, a comparative study

examining an English team midwifery scheme

found that women cared for under a traditional

model of care were more satisfied with antenatal

care (Farquhar et al. 2000). Again, these women

reported achieving a relationship with their

midwives due to greater exposure to named

midwives and higher continuity of carer.

Continuity of carer throughout the childbirth

cycle may also offer women other advantages.

For example, in a grounded theory study that

considered women’s experiences of transfer from

community-based to consultant-based commu-

nity care, the negative impact of transfer on

women’s experiences was reduced by the main-

tenance of midwife continuity from one care

setting to another (Creasy 1997). As well,

McCourt and Page (1996) found that the amount

of information given to women was increased

with known carers. In their evaluation, control

group women were more likely to feel they had

insufficient information. Moreoever, women in

the One-To-One Scheme felt more confident with

their knowledge level (McCourt & Page 1996).

Certainly, participants in the current research felt

communication was facilitated with known

carers.

As well as being of benefit to women, systems

allowing continuity of carer also have a number

of advantages for midwives. For example, as we

have previously discussed the ‘close relation-

ships’ or friendships and partnerships that can

develop also benefit midwives (Sandall 1997,

Fleming 1998, Pairman 1998, Walsh 1999).

Indeed, Sandall (1997) suggested that such

meaningful relationships can protect midwives

against burn-out. Other researchers have simply

concluded that it is easier, as well as more

satisfying, to know the person one is caring for.

However, some authors have cautioned against

midwives fostering over-dependency within such

relationships (Downe 1997, Leap 1997, Sandall

1997).

However, other researchers have disputed the

benefits of known carers. For example, Walden-

strom (1998) concluded that the philosophy of

176 Midwifery

carers may be more important than the indivi-

dual relationship with a particular midwife. The

satisfaction scores of birth-centre women, in the

Stockholm birth-centre trial, who received care

from a known versus unknown midwife carer

during the birth period were very high in both

groups. Care by a known midwife had no impact

on satisfaction rating. The birth-centre team was

comprised of ten midwives and the number of

contacts prior to labour with the known midwife

was not reported. Green et al. (1998) also argued

that the presence of a competent caring profes-

sional was more important to women during

labour than a known carer. Additionally, in the

research trails reviewed by Enkin et al. (1995)

and Hodnett (1998), in many instances the

positive outcomes were linked to a continuous

professional support from caregivers with whom

women had no previous social bond.

We feel, as do others, that there are certainly

difficulties in evaluating the positive effects of a

known carer across the childbearing continuum,

particularly using a quantitative approach. In

their evaluation of one-to-one practice, McCourt

et al. (1998) emphasised the difficulties of

assessing satisfaction using broad satisfaction

measures. The methods adopted in this study

produced data that provided greater insight into

the concept of continuity of carer from the

perspective of the care recipients, namely

mothers.

Non-cumulative interactions

Non-cumulative interactions were defined as

interactions with carers throughout pregnancy

which do not result in an ongoing relationship.

With previous births in the hospital system,

many women described meeting different carers

at each antenatal visit and during their birthing

experience. These non-cumulative contacts re-

sulted in: (a) lack of rapport and (b) women

being unknown.

Lack of rapport – The lack of rapport, as a

result of non-cumulative interactions, was de-

fined as women being unable to feel at ease with

unfamiliar carers. Having care provided by many

different carers throughout pregnancy and birth

culminated in the woman not having the

opportunity to develop rapport with carers.

Women felt a lot of time was spent covering

old ground:

I seem to remember, when you see different

people you always have to start the whole

story. You always have to talk your medical

history. And then they ask about the previous

deliveries, were they normal? You end up

doing that a lot. [Vivian, 3rd baby]

Many participants received care throughout

labour from unfamiliar carers during their

previous hospital experiences. Not being able to

develop rapport resulted in participants not

relating to carers:

. . . there seemed to be two people [staff]

around. I wasn’t that interested in looking

to be honest. But there seemed to be people

around but I couldn’t identify with anybody.

[Jodi, 2nd baby]

Some women also described carers they did not

know as strangers whose presence was a source

of anxiety:

It would have been nice to have everyone

around you that you knew, not just your

family. . .rather than all these strangers

around and then they change and you get

more strangers coming in. It’s a bit scary . . .

[Nicole, 2nd baby]

Experiencing a lack of trust was also mentioned

by some participants when care was provided by

unfamiliar carers:

. . . with the main hospital, when I had my first

baby and the people I didn’t know, I was

thinking to myself: ‘Did I really want to listen

to them?’ I wanted to do my own thing but

then again they were saying ‘no, no, no, you

have to do this’ and I really didn’t want to do

that. . . [Lena, 2nd baby]

For many women, control over the birth

experience was directly linked to the presence

of known carers. One participant described her

feelings when she was facing transfer to the main

hospital for induction of labour after having all

her pregnancy care in the birth centre:

. . . it was an absolutely enormous issue for me

that I would be transferred out...I would lose

control . . . [being cared for by] people I hadn’t

met and didn’t know [Kathy, 4th baby].

Overall, women described a lack of rapport with

unfamiliar carers as having a negative impact

upon their care experiences. This included feeling

ill at ease with carers and anxious about

constantly repeating information. More than

one-third of the 790 women in an Australian

survey by Brown et al. (1994) complained of

seeing different caregivers at each antenatal visit.

As in the present study, this prevented them

developing a rapport with caregivers. One

woman actually stated, ‘I felt we were being

treated like cattle’ (Brown et al. 1994, p. 37).

Moreoever, women often mentioned their con-

cern at having to frequently remind staff of their

needs and problems. Too many people at the

birth was also a recurring theme in Brown et al.’s

research (1994). As well, in the UK, Garcia et al.

(1998) found it was difficult for women to

constantly repeat the same information to

Ongoing relationships with a personal focus 177

different caregivers. Clients also felt their care

might suffer because of too many caregivers.

Woman being unknown – Being unknown was

defined as carer’s lack of knowledge about

women’s previous history and birth preferences.

As previously discussed, in the hospital system

women were exposed to multiple carers through-

out pregnancy and birth. When reflecting on

previous hospital experiences, many participants

said they felt unknown by carers. For one

participant, different carers at every antenatal

visit resulted in a failure to recognise her anxiety

related to a loss in her prior pregnancy:

It was seven months last time and I hadn’t got

one thing ready for the baby. . . it was like I

didn’t want to believe I was going to have a

baby. . .that is how I felt during the

pregnancy. . . I think if I had someone to

reassure me that nothing is wrong, they said

to me that things were fine, but that was

different people every time. . .I think I needed

someone to talk to. [Teri, 2nd baby]

In the hospital system, participants were often

encouraged to write a birth plan, but in many

cases that was not used. The written birth plan

seemed to have minimal impact as a tool to assist

women inform unfamiliar carers of their birth

preferences:

Actually, they sent out a questionnaire to

your home and you filled it out and that

allowed you to list all the choices and

preferences you wanted. But when I actually

went in it was never referred to and I

remember thinking later, I can’t remember

specifically what happened, but I remember

going home and thinking that they didn’t even

look at the care plan that I had written.

[Kathy, 4th baby]

These findings support those of other researchers

who have found that women are disadvantaged

by not being known by their carers. McCourt et

al. (1998) found that many women not able to

have a carer who knew them expressed a need for

this service throughout the childbearing cycle. As

in the present study, some women in Garcia et

al.’s (1998) research, also compared present birth

experiences where they had continuity of carer

with previous births with unknown midwives:

women found the presence of strangers upsetting

particularly during the birth, but mentioned that

this did not happen when they knew their

midwife. Moreoever, in the present research a

critical pre-requisite for women feeling their care

was individual and personalised was knowing

their carer (discussed in greater detail in a

previous article Coyle et al. 2001). However, it

must be noted that other researchers have found

that continuity of carer models across the child-

bearing continuum do not always result in

increased maternal satisfaction with care (Wal-

denstrom 1998, Farquhar et al. 2000). Compar-

isons between studies continue to be problematic

due to inconsistent definitions regarding continu-

ity and the variety of research methods adopted.

Care Structures

The final theme of care structures was defined as

the organisational framework through which

care was delivered. Two dimensions of maternity

care were identified: (1) woman-tailored care and

(2) institution-oriented care. Women’s experi-

ences revealed that birth-centre care was more

likely to be woman tailored, while hospital care

was institution oriented. An exemplar of this

theme is presented in Box 2.

Woman-tailored care

Woman-tailored care was defined as the assis-

tance and attention provided to women during

their pregnancy and birth that focused on their

unique concerns, preferences and needs. This

dimension was characterised by three features:

(a) personalised care, (b) genuine caring and (c)

seeing-me-through.

Personalised care – Personalised care was

defined as attention and assistance provided by

midwives that revolved around women. When

women perceived they were the focus of care,

they felt they had received individualised care.

Care delivery in the birth centre was perceived as

woman focused:

But when they [midwives] talk to you, they

talk to you, not talk to you about something

else or someone else or what someone else did,

it was always your experience and what you

want and if you aren’t happy with that then

they change it because as far as they are

concerned you are the one having the baby

not them. . . [Ruth, 2nd baby]

Many participants described how they felt their

care was adjusted to suit them individually:

Everything went at its own pace. I didn’t feel

things were pushed on us. . .it was very very

nurturing care. . .there was no such thing as

the system taking over. [Vivian, 3rd baby].

Women’s birth centre experiences revealed that

preferences were accommodated by the midwives

caring for them. Midwives were perceived as

supporting women’s choices:

Everyone left me alone. left me to it which is

great, you know. It was really what I wanted

. . .I didn’t want to be poked and bothered,

and told to lay here and do this. [Sarah, 2nd

baby]

178 Midwifery

Genuine caring – Genuine caring is defined as

women’s perceptions that midwives provided

attention and assistance regarded as sincere.

The birth-centre setting allowed women to be

cared for by midwives with whom they had

developed a relationship. The nature of this care

relationship was perceived as very genuine. As

one participant outlined: ‘I was wondering

maybe they do care a different way when they

know someone’ [Bridgit, 2nd baby]. Birth-centre

midwives were also seen to spend more time with

women. This equated to caring: ‘. . .while they

[midwives] were here, that was your time. It

wasn’t looking at the watch all the time..’ [Ruth,

2nd baby].

Overall, when women felt their specific needs

were being met, they interpreted their care as

being personalised. Within the birth-centre

structure, midwives had the time to interact with

women without being rushed. This time invest-

ment made women feel carers were genuinely

interested in them as individuals.

Other researchers have also emphasised the

importance of woman-centred or personalised

care. Page et al. (2000) argue that for more than

two decades some hospitals have tried to provide

such woman-centred care. Moreover, a major

emphasis of the Changing Childbirth report

(DoH 1993) was that women must be the focus

of maternity care; that is their care should be

individual and personalised. Similarly, in Aus-

tralia a number of ministerial reviews have

emphasised the need for personalised and

individualised care during pregnancy and birth

(Health Department of Victoria 1990, Health

Department of Western Australia 1990, National

Health & Medical Research Council 1996).

Seeing-me-through – This third sub theme,

seeing-me-through, was defined as an assurance

Box 2 Exemplar of theme: care structures

Care structures

Def|ned as the organisational framework throughwhichmaternity care is delivered

Dimension: woman-tailored care

Assistance and attention provided towomen during their pregnancy and birth that focuses on their unique concerns,preferences and needs

Features Def|nition Exemplar

1. Personalised care The attention andassistance providedbymidwives that revolvesaroundwomen.

I felt at least they (midwives) tookmymeasureand letme bewhat I needed to be, does thatmakesense rather than treating people routinely.Or Ineed to tell you this because that’s the policy.[V|vian, 3rd baby]

2. Genuine caring Women’s perceptions thatmidwives provideattention and assistancethat was regarded assincere.

I was wonderingmaybe they do care a di¡erentway when they know someone. [Bridgit, 2nd baby]

3. Seeing-me-through An assurance that thesamemidwifewouldprovide all carethroughout labour andbirth.

. . . that was what she [midwife] said to me atmyvisits ‘‘whoever is with youwill bewith you thatentire time.We are not going to leave you, therewill be that same person there thewhole time’’.Like I say, when I look at it thatmade all thedi¡erence in being able to concentrate. . .[Mary, 2nd baby]

Dimension: institution-oriented care

Assistance and attention provided towomen during pregnancy and birth that focuses on the requirementsof the care setting.

Features Def|nition Exemplar

1. Systemised care The attention and assistanceprovided towomen by carerswhich revolves around theroutines and usual practices ofthe care setting.

I know withmy f|rst two sons [hospital births]therewere somany people popping in and out,and students, and all that stu¡ and you are a slabon that table and you are bringing a life intothis world. . . [Maxine, 4th baby]

2. Fragmented labour care The inability of the caresetting to assure one carer forwomen throughout labour.

But I think themain thing was I had likef|ve di¡erent people looking afterme all atonce. . . [Teri, 2nd baby]

Ongoing relationships with a personal focus 179

that the same midwife provided all care through-

out labour and birth. Labour was identified as an

important time for most participants, the birth-

centre model was able to accommodate one

midwife carer for the duration of labour. Many

participants felt this had a positive effect on their

care experiences: ‘if you had just one midwife

throughout that just makes a huge difference, it

really does’ [Bridgit, 2nd baby]. Women felt

positive about the assurance of one carer during

labour:

. . . that was what she [midwife] said to me at

my visits ‘whoever is with you will be with you

that entire time. We are not going to leave

you, there will be that same person there the

whole time’. Like I say, when I look at it that

made all the difference in being able to

concentrate. . . [Mary, 2nd baby]

The findings from the current study highlighted

not only the positive benefits of continuity of

carer throughout the child-bearing cycle, but also

emphasised the impact of having a single mid-

wife carer throughout the birth experience. Birth-

centre care in the present research allowed an

assurance of one carer being available for the

duration of the birth experience. This assurance

of one carer during labour was highly valued by

women, and positively affected their care experi-

ences.

The positive effects of providing continuous

trained support during labour have been well

documented by other researchers (Enkin et al.

1995, Hodnett 1998). In their review of social

and professional support in childbirth, it was

concluded that a critical feature of such support

is the promise or assurance that women in labour

will not be left alone. A consistent finding of the

trials reviewed by Enkin et al. (1995) and

Hodnett (1998) was that the continuous presence

of a trained support person led to a reduction in

pain relief medication, operative deliveries (both

vaginal and caesarean), and an Apgar score of

more than seven at five minutes.

However, as in the present research, continuity

of carer may well be an important pre-requisite

in assuring women of a constant presence during

labour. For example, in McCourt and Page’s

(1996) study, almost all the women with a known

midwife had continuous professional support

during labour compared to only half of the

control group. In the present research the effects

of a ‘known carer’ versus a continuous profes-

sional presence (with no previous social relation-

ship with the women) cannot be separated, as

women in the birth centres had all met their

midwife before labour.

Institution-oriented care

Institution-oriented care was defined as the

assistance and attention provided to women

during pregnancy and birth that focused on the

requirements of the institution. Care delivery in

the hospital was experienced as institution

oriented by many participants in this study. This

dimension was characterised by two features: (a)

systemised care and (b) fragmented labour care.

Systemised care – Systemised care was defined

as the attention and assistance provided to

women by carers that revolved around the

routines and usual practices of the care setting.

Many women perceived that the organisational

structure of the hospital setting dictated the type

of care they received; they felt they were ’just a

number’ in a large system. As one participant

described: ‘I was sitting there . . . no one to talk

to, no-one really cares, you are just a patient’

[Ruth, 2nd baby]. The hospital system did not

allow women to become familiar with carers.

Having intimate procedures performed by un-

known carers resulted in a perception of

impersonal care: ‘. . . the doctor who actually

examined me [vaginal examination] . . . I had

never met him. I found it very impersonal’

[Sharon, 2nd baby].

Hospital care often involved a doctor being

called in for the birth of the baby. One

participant described how she felt when her

doctor attended the birth of her first child. The

doctor’s lack of involvement in labour care made

the woman feel he did not have any under-

standing of what she had been through up to that

point. The conversations going on around the

woman resulted in her feeling that she was

unimportant:

I thought, well you haven’t been with me the

past 20 hours... he [doctor] just walks in and I

remember him talking to one of the nurses

and she asked what he had been doing and he

said he had just had some friends for dinner

and his dinner party had been interrupted or

something and that has stayed on my mind. It

seemed he was feeling oh she is just another

woman in labour, she’s in another world, she

doesn’t really know what’s going on. [Ann,

2nd baby]

The hospital’s inability to offer choices resulted

in women perceiving care as inflexible and

impersonal:

With my first child that is what I had. This is

what we’ve got, this is what you get. I didn’t

like that because I didn’t have a choice. I just

turned up for the experience. [Ruth, 2nd

baby]

Women were also expected to endure long waits

prior to being seen in hospital antenatal clinics,

and carers often had little time available to

discuss concerns with the women.

180 Midwifery

At the hospital I was sitting there waiting for

2 or 3 hours and never saw the same doctor

twice. . .I felt like no one really cared. . . they

didn’t have time to talk. . . you waited 3 hours

and then you were given 10minutes and then

you were out. [Diane, 5th baby]

The hospital structure, where women had pre-

viously birthed, allowed little time for carers to

address individual concerns. This resulted in

women perceiving that carers were lacking in

empathy and that care was system focused rather

than woman centred. These findings suggest, that

despite an increasing emphasis on woman-

centred care, in practice care often remains

depersonalised. Many respondents in Brown

et al.’s (1994) Australian survey of 790 women

also felt they were not treated as individuals by

those working in antenatal, labour and postnatal

settings.

Fragmented labour care – The second sub theme

of fragmented labour care was defined as the

inability of the care setting to assure one carer

for women throughout labour. The hospital shift

system often resulted in women being exposed to

multiple carers within a short time frame. A

woman would often become familiar with her

carers and then a shift change would mean new

staff would appear:

I liked the first lot and I was just starting to

get used to them and then all of a sudden, I

had an epidural, went to sleep a bit, woke up

and I had different ones, and it was like, oh

OK. [Nicole, 2nd baby]

Women were aware that midwives were due off

shift, and this caused them anxiety. Some

participants did not feel it was appropriate for

carers to leave them halfway through labour:

I think, me myself if I was a midwife and I

came in to somebody who was going into

labour I would stay with them through to the

end instead of OK I have to clock off now,

run out and another lady come in and it is OK

right what are we doing. For myself I would

want to see it through to the end and that is

what I felt they should have done instead of

half way through. [Lena, 2nd baby]

Overall, a lack of continuity of carer throughout

labour within hospital settings was perceived to

have a negative impact on many women’s birth

experiences. Too many carers during this crucial

time was a source of anxiety for many women. In

the hospital context, organisational constraints

such as rigid shift work systems, meant women

could not be assured of continuity of carer

throughout labour. These finding support those

of a large Australian survey (Brown & Lumley

1998) that found women experienced fragmented

care during their birth. A UK survey (Garcia et

al. 1998) also found that women giving birth in

hospital were more likely to receive fragmented

care. As in the present study, this fragmented

care was upsetting for women.

The findings of the present research to some

extent support Page et al’s (2000) contention that

the place of care is the most important determi-

nant of the way a midwife practices. As we have

discussed, women in the present study certainly

felt their most recent care in birth centres was

quite different from their previous hospital-care

experiences. The underlying philosophy of the

midwives giving this care is perhaps best summed

up by Brodie (1997) when she discusses the

differences between allegiance to institutions

rather than to women. Systems of care that

encourage a continuous relationship between the

woman and her carer (such as that found in birth

centres in the present research) alter the mid-

wives’ allegiance from the institution to the

individual woman.

CONCLUSION

In summary, in the current study we have been

able to provide a detailed description of how

women perceive continuity of midwife carer, in

the birth-centre context. The benefits of con-

tinuity of carer identified by women in this study

are well supported by other empirical findings. In

the birth-centre setting, cumulative interactions

with a consistent midwife provided women with

the opportunity to develop rapport with their

carer and feel truly known as an individual.

Woman-tailored care also ensured that women

received personalised, genuine care that trans-

cended the entire childbearing continuum. The

perceived success of this model has been the

removal of the organisation barriers, which in

the traditional medical model, have inhibited

continuity of carer due to systemised fragmented

care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the generous

financial assistance provided by the Nurses Board of

Western Australia, Edith Cowan University and the Olive

Anstey Nursing Fund who supported this study.

REFERENCES

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2000 1996 Census of

population and housing. Online. Available: http://

www.abs.gov.au

Brodie P 1997 Being with women: the experiences of

Australian team midwives. Inpublished thesis. Uni-

versity of Technology Sydney

Brown S, Lumley J, Small R et al. 1994 Missing voices the

experience of motherhood. Oxford University Press,

Melbourne Victoria

Ongoing relationships with a personal focus 181

Brown S, Lumley J 1998 Changing childbirth: lessons

from an Australian survey of 1336 women. British

Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 105: 143–155

Coyle KL 1997 Report on the clinical audit used to

evaluate the group practice model of care at the

Family Birth Centre – King Edward Memorial

Hospital. Unpublished report. King Edward Memor-

ial Hospital. Perth. Western Australia

Coyle K, Hauck Y, Percival P et al. 2001 Normality and

collaboration: mothers’ perceptions of birth centre

versus hospital care. Midwifery doi: 10.1054/

midw.2001.0256

Creasy J 1997 Women’s experience of transfer from

community-based to consultant-based maternity care.

Midwifery 13: 32–39

Department of Health 1993 Changing childbirth. Part 1:

Report of the expert maternity group. OHMS,

London

Downe S 1997 The less we do, the more we give. British

Journal of Midwifery 5: 43

Enkin M, Keirse M, Renfrew M et al. 1995 A guide to

effective care in pregnancy and childbirth 2nd ed.

Oxford University Press, New York

Farquhar M, Camilleri-Ferrante C, Todd C 2000 Con-

tinuity of care in maternity services: women’s views of

one team midwifery scheme. Midwifery 16: 35–47

Fleming VE 1998 Women-with-midwives-with-women: a

model of interdependence. Midwifery 14: 137–143

Field PA, Morse JM 1990 Nursing research: The

application of qualitative approaches. Chapman and

Hall, New York

Flint C, Poulengeris P, Grant A 1989 The ‘Know Your

Midwife’ scheme: A randomised trial of continuity of

care by a team of midwives. Midwifery 5: 11–16

Garcia J, Redshaw M, Fitzsimmons B et al. 1998 First

class delivery: a national survey of women’s views on

maternity care. Audit Commission, London

Green J, Curtis P, Price H et al. 1998 Continuing to care.

The organisation of midwifery services in the UK:

a structured review of the evidence. Books for

Midwives Press, Hale

Harding D 2000 Making choices in childbirth. In: Page L

(Ed.) The new midwifery science and sensitivity in

practice. Churchill Livingstone, London

Harvey S, Jarrell J, Brant R et al. 1996 A randomised

controlled trial of Nurse-Midwifery care. Birth 23:

128–135

Health Department of Victoria 1990 Having a Baby in

Victoria. Final Report of the Ministerial Review of

Birthing Services in Victoria, Melbourne

Health Department of Western Australia 1990 Report of

the Ministerial Task Force to Review Obstetric

Neonatal and Gynaecological Services in Western

Australia. Volume 1. Summary and Recommenda-

tions

Hodnett E 1998 Continuity of caregivers during preg-

nancy and childbirth. Cochrane Review, Cochrane

Library Issue 3 Update Software, Oxford

Kenny P, Brodie P, Eckerman S et al. 1994 Westmead

hospital team midwifery project evaluation. Centre

for health economics research and evaluation West-

mead Hospital, Westmead, New South Wales,

Australia

Leap N 1997 Caseload practice that works. MIDIRS

Midwifery Digest 7: 416–418

MacVicar J, Dobbie G, Owen Johnstone L et al. 1993

Simulated home delivery in hospital: a randomised

controlled trial. British Journal of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology 100: 316–323

McCourt C, Page L (Eds) 1996 Report on the evaluation

of One-to-One midwifery. Thames Valley University,

London

McCourt C, Page L, Hewison J et al. 1998 Evaluation of

one-to-one midwifery: women’s responses to care.

Birth 25: 73–80

Morison S, Percival P, Hauck Y et al. 1999 Birthing at

home: the resolution of expectations. Midwifery 15:

32–39

National Health and Medical Research Council 1996

Options for Effective Care in Childbirth for effective

care in childbirth. Australian Government Publishing

Service, Canberra

Page L, Cooke P, Percival P 2000 Providing one to one

practice and enjoying it. In: Page L (Ed.) The new

midwifery science and sensitivity in practice. Church-

ill Livingstone, London

Pairman S 1998 The midwifery partnership: an explora-

tion of the midwife/women relationship. Unpublished

thesis University of Wellington, New Zealand

Rowley MJ, Hensely MJ, Brinstead MW et al. 1995

Continuity of care by a midwife team versus routine

care during pregnancy and birth: A randomised trial.

The Medical Journal of Australia 163: 289–293

Sandall J 1997 Midwives’ burnout and continuity of care.

British Journal of Midwifery 5: 106–11

Shields N, Turnbull D, Reid M et al. 1998 Satisfaction

with midwife-managed care in different time periods:

a randomised controlled trial of 1299 women.

Midwifery 14: 85–93

Strauss A, Corbin J 1998 Basics of qualitative research:

techniques and procedures for developing grounded

theory. Sage Publications, London

Turnbull D, Holmes A, Shields N et al. 1996 Randomised

controlled trial of efficacy of midwife managed care.

The Lancet 348: 213–218

Waldenstrom U 1998 Continuity of carer and satisfaction.

Midwifery 14: 207–213

Waldenstrom U, Nilsson C 1997 A randomised controlled

trial of birth centre care versus standard maternity

care: effects on women’s health. Birth 24: 17–26

Waldenstrom U, Lawson J 1998 Birth Centre Practices in

Australia. Australian & NZ Journal of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology 38: 42–50

Waldenstrom U, Turnbull D 1998 A systematic review

comparing continuity of midwifery care with standard

maternity services. British Journal of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology 105: 1160–1170

Walker JM, Hall S, Thomas M 1995 The experience of

labour: a perspective from those receiving care in a

midwife-led unit. Midwifery 11: 120–129

Walsh D 1999 An ethnographic study of women’s

experience of partnership caseload midwifery prac-

tice: the professional as a friend. Midwifery 15:

165–176