Pray for the Nations - Bajau, West Coast in Brunei - Prayer ...

On your knees and pray! The role of religion in the development of a metal scene in the Caribbean...

Transcript of On your knees and pray! The role of religion in the development of a metal scene in the Caribbean...

243

IJCM 7 (2) pp. 243–257 Intellect Limited 2014

International Journal of Community Music Volume 7 Number 2

© 2014 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/ijcm.7.2.243_1

Keywords

communityheavy metalreligionChristianityPuerto RicoCaribbean

NelsoN Varas-díaz University of Puerto Rico

eliut riVera-segarra Ponce School of Medicine and Health Sciences

sigrid MeNdozaUniversity of Puerto Rico

osValdo goNzález-sepúlVedaPonce School of Medicine and Health Sciences

on your knees and pray!

the role of religion in the

development of a metal

scene in the Caribbean island

of puerto rico1

abstraCt

Heavy metal music is simultaneously reflective of, and reactive to, the cultural underpinnings of the spaces in which it is created. Wallach et al. have emphasized the need to understand metal music outside of Anglo-American contexts and culture. Although the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico seems like an unlikely scenario for the emergence of a metal scene, it has in fact existed via underground means for the past 25 years. Due to the Island’s strong Hispanic and Catholic roots, stemming from

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 243 9/3/14 12:32:48 PM

Nelson Varas-Díaz | Eliut Rivera-Segarra …

244

Spanish colonialism in the fifteenth century, religion has played a central role in the development of the local metal scene. The first systematic organization of a metal scene was structured by Christian metal groups under the name of ‘Metal Mission’ and served as a meeting space for social interaction based on metal music and reli-gion. The objective of this article is to document the role of Christian religion in the emergence and maintenance of a metal scene in Puerto Rico. We will present data from a larger study of the metal scene in Puerto Rico, which used a mixed methods approach including ethnographic observations (300 hours), qualitative interviews (n=50) and surveys (n=400) with members of Puerto Rico’s metal scene. Although metal music has roots in critical perspectives towards religion, our research shows how it has also helped shape the Island’s metal scene.

iNtroduCtioN

Communal actions and identities are important for heavy metal music. Although its lyrics might seem to encourage individual desire over societal demands, a closer examination of a metal concert immediately points to the importance of a collective community. Chanting, moshing, clothing styles and shared knowl-edge of a specific subject matter (such as bands, styles) are just some exam-ples of practices that only exist when individuals are joined by a phenomenon larger than themselves, in this case the music (Snell and Hodgetts 2007). But the admission of a communal perspective in metal music should not be taken at face value, and research should engage in an in-depth examination of the cultural phenomena that have facilitated and even shaped how metal communities are created in particular settings throughout the world (Wallach et al. 2011).

Engaging in research on Puerto Rico’s current metal scene needs to address two major aims. The first is to describe how that community is mani-fested today and the role it plays in the lives of those who participate and sustain it. The second, which we aim to address in this article, is to describe the historical development of that community in order to understand its crea-tion and maintenance over almost three decades. This second aim must take into account the cultural phenomena that have helped shape it, even when the evidence points to potentially unusual sources of inspiration for creating a metal community. We see this effort as a contribution to an agenda set forth by other metal scholars who have identified the importance of understanding metal scenes and communities throughout the world.

Wallach et al. (2011) highlight the importance of addressing the mani-festations of heavy metal music across the world through the lens of plurality, and not focusing exclusively on the commonalities of its expres-sions throughout the globe. Metal music, even when anchored in common definitions, is experienced differently and has diverse beginnings in varied settings. Therefore, the authors suggest that there is a need to expand research on metal scenes outside of Anglo-American contexts, in order to explore the nuances fostered by sociocultural forces in these different settings. That suggestion perfectly reflects the main objective of our article, which aims to explore the role of religion in the emergence of a metal scene in the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico.

religioN iN puerto riCaN soCiety

Highlighting the role of religion in the formation of a local metal scene might seem contradictory. After all, authors such as Marcus Moberg (2012) and Robert Walser (1993) have written on the subject emphasizing how the

1. A preliminary version of this article was presented at the Heavy Metal and Popular Culture Conference held in Bowling Green State University on 4–7 April 2013.

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 244 9/3/14 12:32:48 PM

On your knees and pray!

245

2. Marcus Moberg has documented spaces like Metal Mission in California, present since 1985. We are unaware of the existence of similar organizations in other metal scenes throughout the Caribbean.

‘Satanism charge’ against most metal music has been enduring. We would argue that in Puerto Rico, even today, metal music is perceived as a uniform activity of anti-Christian individuals even though a closer look at the scene would yield a different conclusion. Puerto Rico is still in the midst of a 1980s style moral panic in light of metal music in particular, but also encompass-ing popular music that is interpreted as a threat to traditional cultural values. Even today, local media has still generated uproar in light of the presence of international metal bands that are deemed as anti-Christian (Anon. 2013). This reaction to metal music as a threat to traditional cultural values needs to be understood in light of Puerto Rico’s history.

From 1493 to 1898 Puerto Rico lived under Spanish rule, which explains why its traditions are predominantly Hispanic and its everyday language is Spanish. Catholicism still holds a strong influence on cultural life and govern-ment, shaping world-views on issues related to health, human rights, traditional gender roles for women and national identities. In 1898 the Island became a non-incorporated territory of the United States at the end of the Spanish American War. This process gave way to the expansion of Protestantism, which today is more prevalent than ever in Puerto Rico. The Island’s history is deeply embedded in a process of colonization that has used religion, both Catholic and Protestant, as a mechanism to socialize the masses into what is deemed appropriate norms and values (Varas-Díaz et al. 2011, 2010).

Religion and metal music might seem unrelated to some readers and members of the Island’s metal scene. Unbeknown to most people, even those in the current metal scene, the initial organization of heavy metal music emerged in Puerto Rico from religious groups. We will highlight this phenom-enon using as an example a communal organization with specific and clear religious roots entitled ‘Metal Mission’.

Metal MissioN aNd the eMergeNCe of a struCtured Metal CoMMuNity

‘Metal Mission’ was a local grass-roots movement that emanated in 1986 through the collaboration of metal fans.2 ‘Metal Mission’ allowed its members to blend religion and metal music in the same space via systematic meetings in which youth prayed, listened to music and saw their local Christian bands perform. Throughout this process, important groups in Puerto Rico’s metal scene emerged including the bands Soul Hunter, Sion, Habakkuk, Deathless, Xacrosaint, Sekel and Elohim. These bands played music mostly within the Thrash Metal subgenre, sang in both Spanish and English and focused on original songwriting while also covering tunes from other secular metal bands. The lyrical content of their songs was highly important and reflected their religious orientation.

Through systematic participation of youth and evermore present formal-izations of its activities, ‘Metal Mission’ underwent changes throughout its almost ten years of existence going from informal meetings amongst friends to a more methodical organization with a delineated space and function within a burgeoning metal scene in Puerto Rico. While metal bands existed throughout Puerto Rico, ‘Metal Mission’ was the first systematic effort link-ing bands and fans with a common agenda within a specific physical space. It was in fact the beginning of an organized metal scene in the Island. In this article we present ‘Metal Mission’ through the voices of its members, in order to highlight how it provided a dispersed group of metal fans and musicians with essential elements that in hindsight became important for the creation of a metal scene and community.

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 245 9/3/14 12:32:48 PM

Nelson Varas-Díaz | Eliut Rivera-Segarra …

246

religioN as aN orgaNizatioNal CorNerstoNe

Religion might seem like an unlikely ally for the emergence of a metal scene due to the music’s historical link to anti-religious perspectives and mysticism (Moberg 2012). Still, a detailed view of research ventures from the field of sociology of religion can shed light on how religion can be a catalyst for the provision of social structure and communal identities. For example, litera-ture has shown how religious congregations possess specific organizational features that may be used as templates for other groups to adopt (Demerath and Farnsley 2007). Some of these features include: the provision of a specific physical space to convene, regular gatherings during the week, practices and rituals for worship and sense of membership and social support (Ammerman 1997; Demerath and Farnsley 2007; Roehlkepartain and Patel 2006). These congregational functions provide a structure that can potentially foster a sense of community within its members (Sosis and Alcorta 2003). Perhaps this is why congregations remain a vital socializing institution for many young people (Roehlkepartain and Patel 2006).

For example, in arguing for the positive implications of religion for youth, Smith (2005) has proposed that religious beliefs and participation in group activities provide youth with: moral order, learned competencies and social ties. Moral order imparts youth with directives on how to engage in daily life and make positive choices (i.e. self-control, virtuous actions). Learned compe-tencies acquired in religious settings can provide youth with skills to cope with social demands that can impact their well-being (e.g. peer pressure). Finally, social ties developed as part of religious participation can provide youth with resources of value in challenging moments in their lives (e.g. social support from elders, mutual guidance from peers). These three dimensions are more salient among youth who have high religiosity (i.e. consider religion as impor-tant in their lives), frequently engage in religious practices (i.e. attendance to services, prayer) and adhere to group religious beliefs (i.e. group doctrine or tenets) (Bartkowski 2007). In general, religion has the potential to provide participating youth with some sort of guidance in daily lives and, more impor-tant for community development, structure in a developmental stage in which their worlds seem to be in constant flux. Of course, the mechanisms that foster these positive implications are complex and not invariable and research has also documented the potential negative implications of religion on the daily lives of individuals, specifically on individual health beliefs and manipu-lation (Edington et al. 2002; Ismail et al. 2005; Sarstechi 2004; Zou et al. 2009). It is evident to social scientists that religion provides its members with social structure (Demerath and Farnsley 2007), which can impact individuals in both positive and negative manners depending on its use.

Interestingly, the contribution of religion to social structure and communal identities is echoed in recent literature on metal scene formation, even if done indirectly. For example, Wallach and Levine (2011) have identified four areas of importance in the development of local metal scenes, these include: (1) spaces for circulating metal sounds, (2) gathering places, (3) sites for local performance and (4) promotion of local artists within larger networks. When these criteria are present, the authors suggest that ‘scenic consciousness’ is created (Wallach and Levine 2011: 121). Interestingly, these four criteria echo what religion can do for youth as they also provide emerging spaces with structure, guidance (i.e. likes, dislikes, behaviours) and leadership. In the case of Puerto Rico’s metal scene, ‘Metal Mission’ encompassed the characteristics

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 246 9/3/14 12:32:48 PM

On your knees and pray!

247

exposed by researchers on the sociology of religion and metal scene formation almost seamlessly.

Method

In order to achieve the aim of our study, we implemented an ethnographic research design with both observational and in-depth qualitative inter-view techniques (Atkinson 2001). We also gathered from our interviewees documents that were related to the emergence of the local scene including fanzines, event flyers and pictures. We selected this design in order to become better acquainted with a sector of the population in Puerto Rico that mani-fests itself as an underground movement, almost completely out of the public eye. Furthermore, these qualitative techniques allowed us to become partici-patory agents within the community as part of our data gathering procedures (McIntyre 2008).

Our ethnographic outings were carried out from January to July of 2012 in venues at which the metal community usually meets in Puerto Rico throughout the year. These included mostly small clubs that are used as concert halls or meeting places for communal interaction (i.e. multiple concert events, a flea market specializing in metal merchandise, among other spaces). Our team totalled 300 hours of field observation throughout this period. All ethno-graphic outings were summarized through extensive notes, which were then shared and discussed among members of our team. Our discussions addressed commonalities in these observed experiences, while also exploring different interpretations of events in which team members expressed disagreement.

As part of the ethnographic component of our study, we also invited members of the community to engage in individual in-depth interviews. If they were interested in participating, their contact information was exchanged in order to establish a time and place for the interview that was to their liking. We provided participants with our phone numbers in case they had doubts about the study. Consent was acquired orally upon initiating the interview. Each interview lasted approximately one hour. A total of 50 individuals participated in our in-depth qualitative interviews. With this gathered data we engaged in our qualitative data analysis.

In order to ensure the quality of our analysis, we started with a super-vised transcription process to ensure fidelity. Team members were trained by the investigators on the appropriate way to transcribe an audio interview (Poland 2002). After transcriptions were carried out, the team read the trans-criptions while listening to the audiotapes in order to identify inconsistencies between them. The team met and corrected all errors in the transcriptions. Once this process was completed for each audiotape, the data analysis proce-dures began.

We carried out a discourse analysis procedure based on Potter and Wetherell’s (1987) framework (see also Potter 2004). The research team met on a weekly basis to identify themes or patterns that emerged from our tran-scriptions. The team developed a list of these themes to keep as a master list for the analysis. These themes continued to be modified throughout the read-ing of all the transcriptions. Once those general themes were identified for all the interviews, the team searched for texts that evidenced them in the trans-cription. All selected texts for each theme were discussed in weekly meetings by all members of the team. This step was carried out in order to ensure that the analysts agreed on the final interpretation of the coded passages and to

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 247 9/3/14 12:32:49 PM

Nelson Varas-Díaz | Eliut Rivera-Segarra …

248

avoid the inclusion of verbalizations that were unclear in their phrasing or overall meaning. This consensus-based dispute resolution procedure aimed to generate an inter-rater reliability of 100 per cent for the analysis (Miller 2001). The text selection and coding process was carried out with the use of qualita-tive analysis computer software HyperResearch (V.3.). Throughout the process three steps were taken in order to ensure the trustworthiness of the data. These included: (1) supervising the overall transcription process of the audio taped interviews and focus groups, (2) meeting with members of the research team to discuss the quality of these transcriptions and (3) establishing group discussions throughout the data collection and analysis process so that team members could discuss concerns and findings throughout the data analysis process. The results from this process are presented in the following section.

results aNd disCussioN

For the purpose of this article, we will present and discuss the results from three emerging themes from our qualitative data analysis. These include how ‘Metal Mission’ provided youth in Puerto Rico with: (1) structure, (2) agency and (3) a psychological sense of otherness. Let us examine each theme individually.

Structure: Providing a specific place and identity

One of the main contributions of ‘Metal Mission’ was providing an emerging scene with structure related to physical space, time and rules. This structure was not immediate, as it took time and effort to establish it, and participants in our interviews remembered the transition process within the group. Ionex Cruz, guitarist for the band Xacrosaint, explained it this way:

At the onset it was not really organized. I understand that it began in a garage with a group of friends sharing their faith, their music. From there they began to organize and started hosting activities with bands. I found out through college friends, although I was in high school. At that time it was simply a series of places where people got together to pray, study the Bible, and play with their bands. But it was a movement that became more organized each time to the point that in 1993 it almost turned into a church. I think that was what killed it. People saw it was such a systematic thing… they even asked for offerings. At that point, I think, ‘Metal Mission’ failed. But, I lived that ‘Metal Mission’ moment and it was excellent. You had other people with whom you could share your way of seeing life […]. We met every Saturday… that didn’t fail. It was our meeting point.

The formality of its structure became more apparent to members upon the existence of physical space, which also allowed for systematic scheduling of events throughout the week. The space was small, but it was theirs to do as they wanted. This allowed for more regular activities and people began to ‘know what to expect’ every time they went there. Unguel Cruz, guitarist for the band Deathless, mentioned the following:

‘Metal Mission’ acquired a space. That is when I joined. It was a small scene of bands that had a different message from other local bands. They had a Christian message. At the beginning it was informal with

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 248 9/3/14 12:32:49 PM

On your knees and pray!

249

about 10 bands. We met on Saturdays, two bands played, and there was always someone that preached for a while. Experiences, testimonies, something from the Bible. […]. In time more people came via word of mouth.

As it can be seen here, ‘Metal Mission’ provided not only physical structure to the emerging scene, but organization in terms of which types of activi-ties would be expected in every event. This was vital in a moment when few people had the opportunity to participate in a metal concert, much less be part of a metal scene. In the eyes of some, ‘Metal Mission’ became larger than all other sectors of the Island where metal music was being played. Its structure and physical location had allowed it to become the de facto scene in the mid- to late 1980s. Unguel Cruz described it in our interview:

Interviewer: Do you feel that at some point ‘Metal Mission’ was larger that the rest of the scene?

Unguel: Yes. ‘Metal Mission’ was well defined. With the rest of the bands it was everyone for themselves, a bunch of friends. A group of almost 10 bands that was organized and looking for places to play…. a phenomenon like that did not exist. It was exclusive to what was happening there [at ‘Metal Mission’].

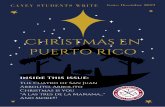

‘Metal Mission’ provided its participants with structure, while simultane-ously creating rules for modelled behaviour in a religious metal concert. It must have been difficult to think about how to behave in a space that was half concert hall and half a church. After all, some at ‘Metal Mission’ were trying to cognitively distance themselves from traditional metal concerts happening in other spaces in Puerto Rico. This may be the main reason why they modelled the traditional structure of the church in terms of leadership and arrangement of their space. As you can see in Figure 1, participants in

Figure 1: Participants in ‘Metal Mission’ attend a weekly concert.

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 249 9/3/14 12:32:49 PM

Nelson Varas-Díaz | Eliut Rivera-Segarra …

250

‘Metal Mission’ are attending a weekly concert. The band has a traditional arrangement in which they take the stage in front of the crowd. But a more detailed look at the audience reveals how the seating plan emulates that of a traditional church. Even though participants are engaging in a heavy metal concert, they see it fit to sit down in folding chairs structured in theatre-like rows. Of course, there were exceptions to this organization but they were minimal in nature.

Although seating arrangements might seem like a simple subject in the process of developing a metal scene, we believe they reflect the extent to which ‘Metal Mission’ provided structure in a moment where the metal scene had very little of it. Participants in ‘Metal Mission’ described the secular scene as somewhat disorganized, consisting of groups of friends playing together but with no specific places to do so or schedules. Other interviewees that did not participate in ‘Metal Mission’ in their formative years corroborated this fact. ‘Metal Mission’ had begun to provide shape to the local metal scene by emulating a somewhat traditional Protestant congregation, which could be found all around the Island.

A sense of agency: Bands had a different purpose

Another way in which ‘Metal Mission’ fostered the development of Puerto Rico’s heavy metal scene, was by providing participants with a sense of agency or purpose. As we know, heavy metal music can play multiple roles in the lives of individuals. Some of these include being critical of your envi-ronment and of course occupying times of leisure. For members of ‘Metal Mission’ heavy metal had a higher calling, it was not limited to entertain-ment. They perceived it as a way to extend the reach of Christian messages to other young people. A sense of urgency provided ‘Metal Mission’ with energy and outright desire to do something about what they perceived as the pro- blematic state of Puerto Rican youth. This sense of purpose was highlighted in every meeting they held on Saturdays and urged some bands to step outside ‘Metal Mission’. Our initial conversation with Unguel Cruz addressed this subject as he expressed how combining religion and metal music seemed natural as a young man.

I don’t know how to explain it really well. I can personally mix Christianity and Heavy Metal music and it’s really natural. Why am I a Christian and metal? Because those are two things that I liked and I mixed them. I’m not sure if there’s anything transcendental about that. I liked things and I mixed them, and that was my vehicle for spreading a good message. It was a way of doing things that I like and using it for something good. I don’t think it’s too profound.

Later during that same interview he elaborated on the role this combination had on him as a musician and a Christian. It was evident that this mixture of religion and metal was more complex than initially stated and in later years not taken lightly. What was once a simple blend of the things he liked as a young man, turned into more than entertainment. Unguel Cruz described it during our interview when talking about his band Deathless:

Deathless had a mission. It was not just playing to have a good time. We decided from the onset to share a Christian message of liberation. We

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 250 9/3/14 12:32:49 PM

On your knees and pray!

251

decided to play outside of churches. Our philosophy was not to play in churches. Christ was a revolutionary that went to bums and prostitutes. We decided to go to pubs where satanic bands were … that is where it was needed.

Other members of ‘Metal Mission’ shared this sentiment. One explained how ‘Metal Mission’ bands began to spread their message throughout the Island, developing metal concerts in local town squares and plazas (see Figure 2). This is significant, as local plazas in small rural towns are the central place of cultural activity, where most citizens would be keenly aware of their presence and bands would have an audience for their religious/musical message. He stated the following:

We wanted to spread the word through music. To our surprise there was a larger group of people wanting to do the same thing. When we found out there were five or six bands doing the same thing we were surprised. We joined immediately. ‘Metal Mission’ used to get bands together, take over the towns’ plazas and do a metal concert, bringing the word of God. That happened in many towns throughout the Island.

In light of this agenda, ‘Metal Mission’ and its bands were perceived as more needed than ever. ‘Metal Mission’ provided them with support and a place where like-minded individuals could be found, which was a vital aspect of creating communal identities. Nevertheless, bands like Deathless and Xacrosaint, which also participated in metal events outside of ‘Metal Mission’, found the process of spreading Christianity difficult within other spaces of the emerging metal scene.

Figure 2: ‘Deathless’ concert in town square.

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 251 9/3/14 12:32:50 PM

Nelson Varas-Díaz | Eliut Rivera-Segarra …

252

Psychological sense of permanent ‘Otherness’

A third contribution of religion to the development of a local metal scene in Puerto Rico has to do with the fostering of a psychological sense of perma-nent otherness. Heavy metal scholars have documented how individuals use metal music to cope with being perceived as outsiders in general culture, while simultaneously fostering that sense of individualism (Brown 2011; Hedge Olson 2011; Fellezs 2011). Participants in ‘Metal Mission’ echoed this sentiment of otherness, emanating from two distinct sources. On the one hand, they were perceived as ‘too metal’ to be part of any traditional Protestant congregation. This entailed being kicked out of several churches before ending up in ‘Metal Mission’. On the other hand, they were considered ‘too Christian’ for the emerging secular metal scene. Although they partici-pated in nonreligious concerts and interacted with nonreligious bands, they also explained sometimes feeling ostracized in the secular metal community. Ionex Cruz explained this duality:

Being a rocker and a Christian was not easy at that time … the end of the 1980s. When I started my band it was hard to find places to play if they were churches. We started playing at ‘Metal Mission’, and some people there did not like that ‘Metal Mission’ bands would play outside of ‘Metal Mission’. Three bands broke with that … Sekel, Deathless and Xacrosaint […]. That is where we needed to be. It was a struggle. Christian bands questioned it … and I must say, when I was 15 there were a bunch of crazy people in the scene. People there were irreverent and then you arrived with a Christian band. When I quoted the Bible people would shout ‘shut the fuck up!’ Good memories of conflicting times …

Another member of ‘Metal Mission’ at the time expressed a similar position, and elaborated on how ‘Metal Mission’ allowed for this feeling of otherness to be manifested:

We are Christians but we like rock. Back then … that did not fit well. ‘Metal Mission’ was an important door to become stronger. […] We were accepted just like we were. I remember the first time we went to Pastor Dennis Soto’s church (‘Metal Mission’ organizer). They accepted us like we were. Hairy, with short pants, dressed in black … He even told the people of his church to leave us be.

Although sometimes met with verbal violence, there was no going back. As a heavy metal fan individuals like Ionex found little open space within tradi-tional churches. Ionex went on to say ‘I’ll be honest, a lot of the churches that I have been to I don’t fit in… I don’t fit in’. When listening to Ionex’s explanation for this feeling of ostracism, it is understood that individuals at ‘Metal Mission’ had very different conceptions of Christianity, at least when compared to traditional churches. Ionex explained this when describing his view on the subject:

It’s the same thing that happens to metal music, it is stigmatized. It’s the same thing that happens to Christianity, it is stigmatized. I think people have no idea of who Jesus Christ is. They allow themselves to be influenced by all the mistakes carried out by the church throughout

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 252 9/3/14 12:32:50 PM

On your knees and pray!

253

history. We are all human beings, and the church is constituted by human beings. […] Jesus came here to break with everything. People have a hard time seeing that. They just see how some churches are pre-judiced and tell women not to shave their legs … that is just shit and has nothing to do with Jesus.

This critical perspective on what church leaders promote, won him no friends within established traditional religious circles. Ionex, and those at ‘Metal Mission’, were simultaneously pushing the boundaries of what churches were willing to accept as Christians, and what the rest of society was willing to accept as legitimate music. This critical positioning stemmed from metal music’s influence on him as a young man. He described it eloquently in one of our interviews:

Heavy Metal influenced my way of being. I started listening to this music when I was in the third grade because I had an older brother. […] It is something that just permeates you. The thing with faith (reli-gion) came much later. I lived metal before the Christian faith. When you come into faith you do so from a perspective that you bring with you. I already had what I learned from metal music, which was to ques-tion everything. Question the system. Some people are so traditional that they need metal and something to make them feel free. We need to use the reason provided by God to question things and metal music has always provided that for me.

This tension described by Ionex in our interview seems important, from a psychological perspective. It highlights how even when ‘Metal Mission’ provided a home for Christian metal bands, a sense of being on the fringes of society was ever present. Now living on two coexisting borders, those of the traditional Church and the emerging secular metal scene, these young musi-cians would incarnate a permanent space of cognitive otherness. Although this might seem problematic from a traditional psychological approach, it fuelled their fire to continue developing their own spaces of acceptance.

CoNClusioN

The emergence of a heavy metal scene in Puerto Rico, as one could expect, was initially unorganized and informal. This is no surprise, as young people gravitated towards the music and its culture while looking for spaces in which to reproduce what they listened to. Lack of funds and resources fostered the enactment of metal shows in informal spaces and small gather-ings. As our research shows, the materialization of a more formal structure in the metal scene can be traced in part to the influence of previous orga-nizational experiences via religion to which youth were exposed. Therefore, ‘Metal Mission’ became the place where the world of religion and metal music collided, and through which the later emulated the structure of the former. Although ironic and contradictory to some, religion helped shape, organize and sustain a community by providing it with structure and agency. Religion as an organizational catalyst for communal actions is not unusual in Latin American countries. For example, organizations around the theology of liberation rallied communal identities in Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s (Montero and Varas-Díaz 2007). Still, few people today make the same

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 253 9/3/14 12:32:50 PM

Nelson Varas-Díaz | Eliut Rivera-Segarra …

254

connection between religion’s capacity to provide structure and agency, and heavy metal music.

The findings from this study highlight the need for metal studies to pay close attention to the cultural backdrops in which metal scenes emerge throughout the world. These cultural practices, which will inevitably vary among countries and regions, are a vital aspect of the development of a deep understanding of these scenes, their emergence, and how their members inter-pret them. Furthermore, an in-depth exploration of how scenes are conceived and assigned functions in the social realm will help researchers explain how on some occasions heavy metal music is not exclusively used for entertainment purposes. For the lives of those embedded in these communities, the music also has the potential to influence world-views and ways of life. Even for those who feel like outcasts in most places, as mentioned by one participant in our study, heavy metal music can provided a place to be oneself without judgment. Such seems to have been the case of ‘Metal Mission’ in Puerto Rico.

It has been almost twenty years since ‘Metal Mission’ closed its doors. Although Christian metal bands can still be found immersed in the local metal scene, most of them have no awareness of the existence of ‘Metal Mission’ or have only heard about it in passing. Still, they all engage in a scene that has its organizational roots deeply embedded in this group of young musicians and bands. To someone outside the metal community, the link between religion and a scene that is now perceived as mostly anti-Christian might seem contra-dictory. For us, even those of us who are not religious, it further evidences the need to understand the complexities entailed in forming metal communities and scenes in light of the cultural and historical factors that have shaped our respective countries. Future studies addressing the link between religion and the emergence of metal communities should take into consideration some limitations faced by our research team. These include: scarce documentation of distant events in the origin of the scene and community, and reliance on recall of community members.

aCKNowledgeMeNts

We would like to thank Ionex Cruz and Unguel Cruz for their valuable input to this article in the form of historical narration and photos.

refereNCes

Ammerman, N. (1997), Congregation and Community, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Anon. (2013), ‘No somos del Diablo’/’We are not of the Devil’, Primera Hora, 25 February, p. 3A.

Atkinson, P. (2001), Handbook of Ethnography, Thousand Oaks: Sage.Bartkowski, J. (2007), ‘Connections and contradictions: exploring the complex

linkages between faith and family’, in N. Ammerman (ed.), Everyday Religion: Observing Modern Religious Lives, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 153–167.

Brown, A. (2011), ‘Heavy genealogy: Mapping the currents, contraflows and conflicts of the emergent field of metal studies 1978–2010’, Journal for Cultural Research, 15: 3, pp. 213–42.

Demerath III, N. and Farnsley, A. (2007), ‘Congregations resurgent’, in J. Beckford and N. Demerath III (eds), The SAGE Handbook of the Sociology of Religion, Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 193–204.

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 254 9/3/14 12:32:50 PM

On your knees and pray!

255

Edington, M. E., Sekatane, C. S. and Goldstein, S. J. (2002), ‘Patient’s beliefs: Do they affect tuberculosis control? A study in a rural district of South Africa’, International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 6: 12, pp. 1075–82.

Fellezs, K. (2011), ‘Black metal: Stone Vengeance sing the trash metal blues’, Popular Music History, 6: 1/2, pp. 180–97.

Hedge Olson, B. (2011), ‘Voice of our blood: National Socialist discourses in black metal’, Popular Music History, 6: 1/2, pp. 135–49.

Ismail, H., Wright, J., Rhodes, P. and Small, N. (2005), ‘Religious beliefs about causes and treatment of epilepsy’, British Journal of General Practice, 55: 510, pp. 26–31.

McIntyre, A. (2008), Participatory Action Research, Qualitative Research Methods Series, Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Miller, R. L. (2001), ‘Innovation in HIV prevention: Organizational and inter-vention characteristics affecting program adoption’, American Journal of Community Psychology, 29: 4, pp. 621–47.

Moberg, M. (2012), ‘Religion in popular music or popular music in religion? A critical review of scholarly writing on the place of religion in metal music culture’, Popular Music and Society, 35: 1, pp. 113–30.

Montero, M. and Varas-Díaz, N. (2007), ‘Latin American community psycho-logy: Development, implications, and challenges within a social change agenda’, in S. M. Reich, M. Riemer, I. Prilleltensky and M. Montero (eds), International Community Psychology: History and Theories, United States: Springer, pp. 63–97.

Poland, B. D. (2002), ‘Transcription quality’, in J. F. Gubrium and J. A. Holstein (eds), Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method, Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 629–649.

Potter, J. (2004), ‘Discourse analysis’, in M. Hardy and A. Bryman (eds), Handbook of Data Analysis, London: Sage, pp. 607–623.

Potter, J. and Wetherell, M. (1987), Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour, London: Sage.

Roehlkepartain, E. and Patel, E. (2006), ‘Congregations: Unexamined crucibles for spiritual development’, in E. Roehlkepartain, P. Ebstyne, L. Wagener and P. Benson (eds), The Handbook of Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence, Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 324–35.

Sarstechi, L. (2004), ‘Jehovah’s witnesses, blood transfusions and transplanta-tions’, Transplantations Proceedings, 36: 3, pp. 499–501.

Smith, C. (2005), Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers, New York: Oxford University Press.

Snell, D. and Hodgetts, D. (2007), ‘Heavy metal, identity and the social nego-tiation of a community of practice’, Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 17: 6, pp. 430–45.

Sosis, R. and Alcorta, C. (2003), ‘Signaling, solidarity, and the sacred: The evolution of religious behavior’, Evolutionary Anthropology, 12: 6, pp. 264–74.

Varas-Díaz, N., Marqués, D., Rodríguez-Madera, S., Burgos, O. and Martínez Taboas, A. (2011), La Religión Como Problema en Puerto Rico/Religion as a problem in Puerto Rico, San Juan: Terranova.

Varas-Díaz, N., Neilands, T. B., Malavé Rivera, S. and Betancourt, E. (2010), ‘Religion and HIV/AIDS stigma: Implications for health professionals in Puerto Rico’, Global Public Health, 5: 3, pp. 295–312.

Wallach, J. and Levine, A. (2011), ‘I want you to support local metal: A theory of metal scene formation’, Popular Music History, 6: 1, pp. 116–34.

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 255 9/3/14 12:32:50 PM

Nelson Varas-Díaz | Eliut Rivera-Segarra …

256

Wallach, J., Berger,H. and Greene, P. (2011), Metal Rules the Globe, New York: Duke University Press.

Walser, R. (1993), Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music, New Hampshire: University Press of New England.

Zou, J., Yamanaka, Y., John, M., Watt, M., Osterman, J. and Thielman, N. (2009), ‘Religion and HIV in Tanzania: influences of religious beliefs on HIV stigma, disclosure, and treatment attitudes’, BMC Public Health, 9: 75, pp. 75–87.

suggested CitatioN

Varas-Díaz, N., Rivera-Segarra, E., Mendoza, S. and González-Sepúlveda, O. (2014), ‘On your knees and pray! The role of religion in the development of a metal scene in the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico’, International Journal of Community Music 7: 2, pp. 243–257, doi: 10.1386/ijcm.7.2.243_1

CoNtributor details

Nelson Varas-Díaz (Ph.D.) is a Social Psychologist and Professor at the University of Puerto Rico. Varas-Díaz’s work on social stigma and communal identities has appeared in the Interamerican Journal of Psychology, Qualitative Health Research, American Journal of Community Psychology, AIDS Education & Prevention, Qualitative Report, and Global Public Health. His research has focused on the social stigmatization of disease (i.e. HIV/AIDS, addiction), marginalized groups (i.e. transgender individuals) and cultural practices (i.e. metal music, reli-gion). Dr Varas-Díaz is currently the principal investigator for the first system-atic study of the heavy metal scene in the Caribbean island of Puerto Rico.

Contact: University of Puerto Rico, Center for Social Research, Río Piedras Campus, P.O. Box 23345, San Juan, 00931-3345, Puerto Rico.E-mail: [email protected]

Eliut Rivera-Segarra is a Ph.D Clinical Psychology student at the Ponce School of Medicine & Health Sciences, Puerto Rico. His research interests include stigma theory, religion and heavy metal studies. Rivera-Segarra has presented his work on heavy metal studies at the Convention of the Puerto Rican Psychological Association and the EMP Pop Conference. His most recent publication is a chapter in the book Hardcore, Punk and Other Junk.

Contact: Ponce School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Clinical Psychology Program, P.O. Box 7004, Ponce, 00732-7004, Puerto Rico.E-mail: [email protected]

Sigrid Mendoza is a Ph.D. Social Community Psychology student at the University of Puerto Rico. She recently presented a paper in the Heavy Metal and Popular Culture Conference on traditional Latin American and Caribbean female norms and the heavy metal scene as a possible space to transgress these traditional norms. Her research interests include: gender dynamics and feminism, heavy metal studies, ethnography, social construction of sexuality and neo-tribal community theory.

Contact: University of Puerto Rico, Center for Social Research, Río Piedras Campus, P.O. Box 23345, San Juan, 00931-3345, Puerto Rico.E-mail: [email protected]

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 256 9/3/14 12:32:50 PM

On your knees and pray!

257

Osvaldo González-Sepúlveda is a Ph.D. Clinical Psychology student at the Ponce School of Medicine & Health Sciences, Puerto Rico. He has directed various movie projects, including No me visites/Do not visit me (2011), which was presented at the XXXIII Movie Festival in La Habana, Cuba.

Contact: Ponce School of Medicine and Health Sciences, c/o Calle Sol #39, Apartment 203, Ponce, 00730, Puerto Rico.E-mail: [email protected]

Nelson Varas-Díaz, Eliut Rivera-Segarra, Sigrid Mendoza and Osvaldo González-Sepúlveda have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work in the format that was submitted to Intellect Ltd.

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 257 9/3/14 12:32:50 PM

Intellect is an independent academic publisher of books and journals, to view our catalogue or order our titles visit www.intellectbooks.com or E-mail: [email protected]. Intellect, The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds, Bristol, UK, BS16 3JG.

Metal Music StudiesISSN 20523998 | Online ISSN 20524005

Metal Music Studies aims to be the focus for research and theory in metal music studies – a multidisciplinary (and interdisciplinary) subject field that engages with a range of parent disciplines, including sociology, musicology, humanities, cultural studies, geography, philosophy, psychology, history, natural sciences. The journal provides an intellectual hub for the International Society of Metal Music Studies and a vehicle to promote the development of

metal music studies

EditorKarl SpracklenLeeds Metropolitan University

intellectwww.intellectbooks.com

publishersof original

thinking

IJCM_7.2_Varas-Diazetal_243-257.indd 258 9/3/14 12:32:51 PM

Copyright of International Journal of Community Music is the property of Intellect Ltd. andits content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without thecopyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or emailarticles for individual use.