Oleas et al. - Molecular Systematics of Caribbean Threatened Species-Botanical-Review

Transcript of Oleas et al. - Molecular Systematics of Caribbean Threatened Species-Botanical-Review

1 23

The Botanical Review ISSN 0006-8101Volume 79Number 4 Bot. Rev. (2013) 79:528-541DOI 10.1007/s12229-013-9130-y

Molecular Systematics of Threatened SeedPlant Species Endemic in the CaribbeanIslands

Nora Oleas, Brett Jestrow, MichaelCalonje, Brígido Peguero, FranciscoJiménez, Rosa Rodríguez-Peña, RamonaOviedo, Eugenio Santiago-Valentín, etal.

1 23

Your article is protected by copyright and

all rights are held exclusively by The New

York Botanical Garden. This e-offprint is

for personal use only and shall not be self-

archived in electronic repositories. If you wish

to self-archive your article, please use the

accepted manuscript version for posting on

your own website. You may further deposit

the accepted manuscript version in any

repository, provided it is only made publicly

available 12 months after official publication

or later and provided acknowledgement is

given to the original source of publication

and a link is inserted to the published article

on Springer's website. The link must be

accompanied by the following text: "The final

publication is available at link.springer.com”.

Molecular Systematics of Threatened Seed Plant SpeciesEndemic in the Caribbean Islands

Nora Oleas1,2,3 & Brett Jestrow2&

Michael Calonje1,4 & Brígido Peguero5 &

Francisco Jiménez5 & Rosa Rodríguez-Peña1,2,5 &

Ramona Oviedo6 & Eugenio Santiago-Valentín7 &

Alan W. Meerow8& Melissa Abdo2 &

Michael Maunder1 & M. Patrick Griffith4 &

Javier Francisco-Ortega1,2,9

1 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, USA2 Kushlan Tropical Science Institute, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Coral Gables, Miami, FL 33156,USA

3 Current Address: Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, UniversidadTecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador

4Montgomery Botanical Center, Coral Gables, Miami, FL 33156, USA5 Departamento de Botánica, Jardín Botánico Nacional, Santo Domingo, República Dominicana6 Herbario, Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática, 10800 La Habana, Cuba7 Jardín Botánico de Puerto Rico, Universidad de Puerto Rico, San Juan, PR 00936, USA8 United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service, National Germplasm Repository,Miami, FL 33158, USA

9 Author for Correspondence; e-mail: [email protected]

Published online: 27 August 2013# The New York Botanical Garden 2013

Abstract A review of available Caribbean Island red-lists species (CR and EN categoriesbased on the IUCN guidelines from 2001, and E category established according to theIUCNguidelines from1980) is presented.A database of over 1,300 endemic species that areeither Critically Endangered or Endangered sensu IUCN was created. There are molecularsystematic studies available for 112 of them. Six of these species (in six genera) are the onlymembers of early divergent lineages that are sister to groups composed of a large number ofclades. Seven of the species (in seven genera) belong to clades that have a small number oftaxa but are sister to species/genus-rich clades. Ten of the species (in six genera) are sister totaxa restricted to South America or nested in clades endemic to this region. Fifty-seven ofthe species (in 35 genera) are sister to Caribbean Island endemic species. Erigeronbelliastroides, an Endangered (EN) Cuban endemic, is sister to the Galapagos genusDarwiniothamnus. The phylogenetic placement of four of the threatened species resultedin changes in their taxonomic placement; they belong to polyphyletic or paraphyletic genera.

Keywords Biodiversity hotspots . Tropical islands . Phylogenies . Spermatophyta .

IUCN . Red lists

Bot. Rev. (2013) 79:528–541DOI 10.1007/s12229-013-9130-y

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12229-013-9130-y)contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Author's personal copy

Introduction

Caribbean Island Endemic Red Lists

Revealing the phylogenetic and taxonomic placement of threatened species helps toestablish conservation priorities and to increase public awareness for conservation(Purvis et al., 2005). The Caribbean Islands are a major focus for conservation becausethey are one of the 34 biodiversity hotspots (Smith et al., 2004). These islands have beenseverely impacted by human activities, and in the last 500 years there has been adramatic reduction of the original vegetation cover primarily because of habitat loss(Maunder et al., 2008, 2011).

The Caribbean Islands harbor a native flora of approximately 12,000 species ofvascular plants, and over 8,000 of them are endemic to the region (Santiago-Valentín& Olmstead, 2004). There is no comprehensive red list for this endemic flora based onthe IUCN (2001) categories of threat. Available information on the conservation statusof these Caribbean endemics is primarily limited to the few taxa found in the Red List ofThreatened Species of the World Conservation Union (IUCN, 2011) and those listed in14 publications focusing on threatened plant species of Antigua, Barbuda, British VirginIslands, Cayman Islands, Cuba, Dominican Republic, French Lesser Antilles, Jamaica,and Puerto Rico (Borhidi & Muñiz, 1983; Kelly, 1988; Government of Jamaica, 2000;Rankin-Rodríguez & Areces-Berazaín, 2003; Gargominy, 2003; Pollard & Clubbe,2003; Berazaín-Iturralde et al., 2005; González-Torres et al., 2007; Burton, 2008; Pratt& Lindsay, 2008; Urquiola Cruz et al., 2010; Centro Nacional de Biodiversidad, 2011;Peguero & Jiménez, 2011; U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2011).

The most recent red lists are from Cayman Islands, Cuba and Dominican Republic(Rankin-Rodríguez & Areces-Berazaín, 2003; Berazaín-Iturralde et al., 2005; González-Torres et al., 2007; Burton, 2008; Centro Nacional de Biodiversidad, 2011; Peguero &Jiménez, 2011; U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2011), and these are the only ones thatfollow the latest conservation categories and criteria developed by theWorld ConservationUnion (IUCN, 2001). The remaining studies do not distinguish between the “CriticallyEndangered” and “Endangered” categories and they place those taxa belonging to thesetwo groups within the broad “Endangered” rank [as defined by IUCN (1980)]. In order todifferentiate between the “Endangered” category sensu IUCN (2001) or sensu IUCN(1980), in our paper the code “E”will be used when the “Endangered” conservation statuswas developed based on the criteria proposed by IUCN in 1980. We use the acronym“EN” when this category refers to the most recent guidelines established by IUCN in2001. It is noteworthy that the “Critically Endangered” category is not part of the threatranks delineated by IUCN in 1980.

In a previous review Torres-Santana et al. (2010) reported that approximately 1,553of the single-island-endemic vascular plant species belong to the Vulnerable (VU),Endangered (EN), or Critically Endangered (CR) IUCN categories.

Unique Molecular Phylogenetic Patterns Revealed in Our Studies—Review Aims

Because of the geographical location of our institutes and their research history,studies pertinent to plant biodiversity (including genetic diversity and molecularphylogenetics) of the Caribbean Islands have been a main focus of our teams (e.g.,

Caribbean Island Threatened Seed Plants 529

Author's personal copy

Bogler & Francisco-Ortega, 2004; Santiago-Valentín & Olmstead, 2004; Francisco-Ortega et al., 2007; Meerow et al., 2007, 2012; Santiago-Valentín & Francisco-Ortega, 2008; Maunder et al., 2008, 2011; Andrus et al., 2009; Namoff et al.,2010a). We found that previous molecular systematic research conducted in ourlaboratories demonstrated that at least six threatened species have: (1) unusualbiogeographical connections or (2) are part of early divergent lineages that are sisterto a large assemblage of genera or species. One of the most striking examples isprovided by Feddea cubensis. This is a Critically Endangered species endemic to theunique nickel-rich serpentine soil environments of eastern Cuba. This taxon is sisterto the Heliantheae, one of the largest clades of the family [ca. 482 genera and 5,700species, Cariaga et al. (2008)]. Based on both molecular and morphological data Cariagaet al. (2008) accommodated this genus in its own unigeneric tribe, the Feddeeae.

A similar pattern is followed by Microcycas, a Critically Endangered unispecificgenus, confined to a few “mogotes” of western Cuba, which is sister to Zamia (Bogler& Francisco-Ortega, 2004; Zgurski et al., 2008). The latter is the largest genus of theZamiaceae, and the second largest in the order Cycadales (Osborne et al., 2012).Zamia is found from Bolivia northward through tropical America to southeasternUnited States and the Caribbean Islands. The third example is provided by Erigeronbellidiastroides (Asteraceae), an Endangered (EN) herbaceous species confined toquartz sand areas of western Cuba which is sister to Darwiniothamnus (Asteraceae), agenus endemic to the Galápagos Islands that has a woody habit (Andrus et al., 2009).

The fourth example concerns the recently described genus endemic to Hispaniola:Garciadelia (Euphorbiaceae). This genus has four species, all of them are threatenedand it is sister to a clade composed of two Caribbean Island genera, Lasiocroton andLeucocroton (Euphorbiaceae). These two genera have over 30 species, the majority ofwhich are in Leucocroton and are endemic to serpentine areas of Cuba suggesting thatthe species growing on limestone areas to have the ancestral ecological conditions(Jestrow et al., 2008, 2010, 2011). Studies within this group showed the value ofmolecular data to address taxonomic questions.

The fifth study from our teams is for a Critically Endangered palm species endemic toHaiti. Attalea crassispatha is the only member of the genus to occur in the CaribbeanIslands, and a molecular phylogeny based on seven unlinked nuclear loci stronglysupports this species as sister to a clade that includes the Scheelea and Orbignya groups(Meerow et al., 2009). It is estimated that these two groups have over 45 species.

These molecular phylogenetic studies have identified a sixth case in which an assem-blage of four endemic genera [Coeloneurum (unispecific), Espadaea (unispecific),Goetzea (two species), and Henoonia (unispecific)] form a monophyletic group withinthe Solanaceae that is recognized as an important part of the subfamily Goetzeoideae(Olmstead et al., 2008). One of the species of this generic alliance, G. elegans, isEndangered (EN) (Caraballo-Ortiz & Santiago-Valentín, 2011), and it is sister to theHispaniolan endemic G. ekmanii O. E. Schulz (Olmstead et al., 2008).

In this study we provide a review of molecular phylogenies that have includedCaribbean Island endemics that are most threatened [E, EN and CR categories of theIUCN (1980, 2001) (Fig. 1)]. Our study aimed to: (1) evaluate to what extent these highconservation priority endemics have been the subject of molecular systematic studies,(2) to know if the phylogenetic patterns detected in our laboratories are also reported inother molecular systematic studies that included threatened species, and (3) to determine

530 N. Oleas et al.

Author's personal copy

the impact that molecular studies are having in our current understanding of thesystematic relationships of these taxa. We are aware that under the system establishedby IUCN (2001) the term “Threatened” applies to taxa belonging to three categories:Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN), and Critically Endangered (CR). However, in ourreview the concept of “Threatened” refers only to the Critically Endangered (CR) andEndangered (EN and E) categories as defined by IUCN (1980, 2011).

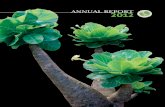

Fig. 1 Images of threatened Caribbean Islands endemics that have been the subject of molecular phylo-genetic studies: a Croton trigonocarpus (photo B. Van Ee); b Pereskia quisqueyana (photo R. Briones); cPhyllomelia coronata (photo J. Molina); d Rhytidophyllum grandiflorum (photo F. Jiménez); e Portlandiaalbiflora (by courtesy of Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, photo J. Valdés)

Caribbean Island Threatened Seed Plants 531

Author's personal copy

Methods

Using the available red lists for the Caribbean Islands (see above) we compiled a list ofthreatened endemic species. This initial list did not include the work of Borhidi andMuñiz(1983) as we found many inconsistencies between the conservation categories of thisstudy and those provided by most recent studies (i.e., Rankin-Rodríguez & Areces-Berazaín, 2003; Berazaín-Iturralde et al., 2005; González-Torres et al., 2007; UrquiolaCruz et al., 2010; Centro Nacional de Biodiversidad, 2011). Based on this list ofthreatened endemic species we conducted additional bibliographic searches to locatepublished molecular phylogenies and additional conservation information that includedthese Endangered/Critically Endangered taxa [sensu IUCN (1980, 2001)]. As primarydata base/bibliographic resources for these searches we used the ISI Web of Knowledge(Thomson Reuters, 2011), theGenBank NIH Genetic Sequence Data Base (Benson et al.,2011), the Kew Bibliographic Data Base (Royal Botanic Gardens – Kew, 2011), andrelevant conservation reviews, monographs and taxonomic treatments (e.g., Hágsater &Dumont, 1996; Oldfield, 1997; Donaldson, 2003; Zona et al., 2007; Jestrow et al., 2010).

These studies provided us with details concerning the phylogenetic position of theCaribbean Islands endemics. We looked into statistical support for relevant nodes,taxonomic sampling of these studies, number of DNA independent markers that wereutilized to generate the phylogenies, and the actual phylogenetic placement of thethreatened species.

Results of Review

Based on the list of threatened species that we prepared for this study we estimate thatthere are over 1,300 seed-plant species that are either Endangered or CriticallyEndangered [sensu IUCN (1980, 2001)] on the Caribbean Islands. This representsapproximately 16 % of the endemic flora of vascular plants. However, we believe thisto be a “conservative” value because our review did not include ferns and the availablered lists do not cover the complete Caribbean flora. For instance, 30 % of the Cubanflora still needs to be assessed (Leiva & González-Torres, 2010). We anticipate that thisfigure will increase once there are completed IUCN red lists for: (1) Haiti, the Bahamas,most of the Lesser Antilles and (2) the component of the endemic flora not included forthe other islands. The three genera with the highest number of threatened species areEugenia (Myrtaceae) (54 species), Lepanthes (Orchidaceae) (27 species), and Pilea(Urticaceae) (31 species).

Including studies from our research teams, there are molecular topologies availablefor 112 of the threatened species (ca. 1 % of the total endemic flora) [Appendices S1-S3(supplementary online material)]. However, molecular studies for four species [i.e.,Acidocroton trichophyllus (Euphorbiaceae), Brunfelsia portoricensis (Solanaceae),Synapsis ilicifolia (Bignoniaceae), and Zanthoxylum ekmanii (Rutaceae)] were notinformative for our research as these studies had the endemic species as outgroups orto test particular phylogenetic methods or to investigate the utility of DNA barcodemarkers in floristic studies (Appendix S3).

Molecular phylogenies for 57 of the threatened species are based on a single linkedDNA region, or have low statistical support for the relevant nodes. With few exceptions

532 N. Oleas et al.

Author's personal copy

(i.e., McDowell & Bremer, 1998; Lavin et al., 2003; Steinmann et al., 2007; Bécquer-Granados et al., 2008; Michelangeli et al., 2008; Roncal et al., 2008; Salazar & Nixon,2008; Schaefer et al., 2008; Van Ee et al., 2008; Graham, 2010) most of the reviewedstudies did not focus on molecular systematics of Caribbean groups but on developingphylogenies for particular genera or suprageneric taxa.

Molecular Phylogenies: Biogeographical Patterns

Our review of studies from other research groups found that a large proportion ofthe threatened endemics have sister relationships with other West Indies endemics(53 species in 33 genera: Acacia (Fabaceae), Calycogonium (Melastomataceae),Calyptranthes (Myrtaceae), Catesbaea (Rubiaceae), Cestrum (Solanaceae),Cinnamodendron (Canellaceae), Coccoloba (Polygonaceae), Croton (Euphorbiaceae),Elekmania (Asteraceae), Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae), Exostema (Rubiaceae), Gaussia(Arecaceae), Gesneria (Gesneriaceae), Ginoria (Lythraceae), Guettarda (Rubiaceae),Harnackia (Asteraceae), Henriettea (Melastomataceae), Isidorea (Rubiaceae),Lescaillea (Asteraceae), Matelea (Apocynaceae), Mecranium (Melastomataceae),Miconia (Melastomataceae), Pachyanthus (Melastomataceae), Pereskia (Cactaceae),Phialanthus (Rubiaceae), Phyllomelia (Rubiaceae), Poitea (Fabaceae), Portlandia(Rubiaceae), Rhytidophyllum (Gesneriaceae), Rondeletia (Rubiaceae), Scrophularia(Scrophulariaceae), Solanum (Solanaceae), and Tolumnia (Orchidaceae), seeAppendix S3). A few of the threatened endemics are nested inside clades restricted toSouth America or sister to lineages from this region (10 species in 6 genera: Crescentia(Bignoniaceae),Doerpfeldia (Rhamnaceae), Elekmania,Gesneria, Rhytidophyllum, andStyrax (Styracaceae), see Appendix S3). The rest of the threatened species had sisterrelationships with species/clades with a widespread distribution or restricted to North orCentral America.

Our review did not find any species that was sister to an Old World clade; however,the clade that includes of the Cuban monotypic genus Doerpfeldia and the SouthAmerican genus Ampelozizyphus (Rhamnaceae) (two species) was sister to a genusfrom Madagascar, Bathiorhamnus (Rhamnaceae) (seven species) (Richardson et al.,2000) (see below). The second case that showed a connection with the Old World wasfound inGinoria, the ITS phylogeny supports Tetrataxis (Lythraceae) (unispecific genusendemic to Mauritius Island, Indian Ocean) as part of a clade that has five of the speciesof Ginoria. The threatened G. jimenezii is sister to this clade (Graham, 2010).

Molecular Phylogenies: Sister Relationships

Our review was concordant with the results obtained in our laboratories and showed thatthree of the threatened species are sister to clades with a large number of species or genera.They included the recently described endemic and monotypic genus Linnaeosicyos(Cucurbitaceae), an Hispaniolan taxon that is sister to the Sicyueae clade (Cucurbitaceae),a group composed of 125 species in 16 genera (Schaefer et al., 2008). The Cubanunispecific genus Lepturidium (Poaceae) follows a similar pattern as it is sister to theMulhlenbergiinae (Poaceae) [~176 species in a single genus, Muhlenbergia (Poaceae)](Peterson et al., 2010). The third example is provided by Leptogonum (Polygonaceae), amonotypic Hispaniolan genus (Burke et al., 2010) that is sister to the six-tepaled clade of the

Caribbean Island Threatened Seed Plants 533

Author's personal copy

subfamily Eriogonoideae (Polygonaceae) (Burke et al., 2010). This group includes ninegenera (~300 species).

Six of the threatened species belong to monophyletic groups that have a small numberof taxa but are sister to species/genus-rich clades. For instance the Endangered (EN)Magnolia minor (Magnoliaceae) together with four other species of this genus form amonophyletic assemblage that is sister to the rest of the genus. Three species-poor palmgenera with threatened endemics appear to follow the same pattern. A phylogeneticanalyses based on morphological and molecular data supports Gaussia (five species,three of them endemic to the Caribbean Islands) as sister to Chamaedorea (77 species)(Cuenca et al., 2009). Likewise a molecular systematic study for the subfamilyCeroxyloideae shows Pseudophoenix (four species, three of them endemic to theCaribbean Islands) as sister to the tribes Ceroxyleae and Phytelepheae (Trénel et al.,2007). These two tribes encompass seven genera with 39 species. Within the subfamilyCoryophoideae, Colpothrinax (three species, one of them endemic to Cuba) is sister to aclade that includes of nine genera (36 species). Within the Rhamnaceae, the Cuban genusDoerpfeldia, Ampelozizyphus, and Bathiorhamnus (see above) form a lineage that is sisterto a clade composed of four tribes with 22 genera (Richardson et al., 2000). The lastexample is provided byDomingoa (Orchidaceae) (three species endemic in the CaribbeanIslands, including the Endangered (EN) D. nodosa), as this genus together withHomalopetalum (Orchidaceae) (seven species, genus found in Mexico, Central andSouth America, and Greater Antilles) form a monophyletic group (with ~12 species) thatis sister to a clade that has a great portion of the taxonomic diversity of the tribe Laeliinae(Orchidaceae), including large genera such as Cattleya (ca. 40 species) and Epidendrum(ca. 1,500 species) (Van Den Berg et al., 2009).

Two other examples concern threatened species that are sister to clades with fewcontinental species but that have unique morphological features. For instance Tillandsiaarizajuliae (Bromeliaceae) is sister to a clade that has the pseudobulbous taxa of thisgenus (12 species, none of them endemic to the Caribbean Islands) (Chew et al., 2010).A second case concerns Acacia anegadensis and A. roigii. These two CriticallyEndangered species form a monophyletic group that is sister to a clade with 13 species(Gómez-Acevedo et al., 2010). Ten of these species form a unique monophyletic groupknown as the “Myrmecophillous group.” This group has those New World species thatmaintain a symbiosis with several species of ants. TheMyrmecophillous species displaymorphological modifications associatedwith ant mutualism, such as domatia, extrafloralnectaries, and leaflet tips that provide food for the ants.

Among the threatened species belonging to endemic genera, the unispecific genusPhyllacanthus (Rubiaceae) is sister to a clade with four genera, two of them, Isidorea(Rubiaceae) and Portlandia, endemic to the Caribbean Islands (Motley et al., 2005).Also within the Rubiaceae, the endemic genus Phialanthus (18 species, two speciesincluded in the study) is part of a clade that include two additional endemic genera:Ceratopyxis (monotypic) and Schmidtottia (16 species, one included in the study)(Motley et al., 2005).

Molecular Phylogenies: Taxonomic Implications

Molecular phylogenies have had an impact on the current taxonomic placement ofsome of these threatened species. For instance, based on DNA and morphological

534 N. Oleas et al.

Author's personal copy

evidence the Critically Endangered species Trichosanthes amara (Cucurbitaceae)was transferred to Linnaeosicyos (Schaefer et al., 2008, see above). Likewise molecularand micro/macromorphological data led Jestrow et al. (2010) to describe Garciadelia(see Introduction above) to accommodate Leucocroton leprosus, a CriticallyEndangered species from Haiti known from only two herbarium collections from theearly 20th century. Jestrow et al. (2010) described three additional species in this genus;all of them are threatened.

Results from molecular systematic studies have resulted in taxonomic changes thathave been relevant in three additional genera. In the Euphorbiaceae, DNA phylogeniesclearly show that the Cuban genusMoacroton (Euphorbiaceae) is paraphyletic with fourspecies of Croton from the mainland (Van Ee et al., 2008); therefore, the CriticallyEndangeredM. trigonocarpus is currently named C. trigonocarpus. Molecular phylog-enies for subtribe Laeliinae (see above) reveal the Caribbean genus Domingoa asparaphyletic with Nageliella (Orchidaceae), the most recent taxonomic treatment forthis group merges both genera in a single one:Domingoa (Pridgeon et al., 2005). Withinthe Rubiaceae, Rova et al. (2009) reported Rondeletia (two threatened species) asparaphyletic with the Caribbean Island genus Stevensia (Rubiaceae) (11 species), thisresulted in the recent merging of the latter within Rondeletia (Borhidi, 2010).

There are molecular phylogenetic data for 14 threatened species belonging to theMelastomataceae. These species are placed in six genera within the tribes Miconieae orHenrietteeae. Only two of these genera (i.e., Henriettea and Mecranium) appear to bemonophyletic (Michelangeli et al., 2008; Penneys et al., 2010). In contrast,Calycogonium,Miconia, Pachyanthus, and Tetrazygia are polyphyletic (Michelangeli et al., 2008;Bécquer-Granados et al., 2008) and it is likely that some of the Caribbean endemicscurrently in these four genera will need new taxonomic placements (Michelangeli, pers.comm). Most of these genera have a large number of species and are taxonomically“difficult” to resolve.

Cinnamodendron provides another example of a polyphyletic genus with a CriticallyEndangered species (i.e., C. cubense). Molecular systematic studies conducted bySalazar and Nixon (2008) show that Caribbean Island species of Cinnamodendron willneed to be placed in a different genus. The generitype,C. axillare, is a Brazilian endemicthat belongs to a “South American” clade that does not have any of the Caribbean Islandendemics. Matelea (Cactaceae) [generitype: M. palustris (Farr et al., 1979)] andPereskia [generitype: P. aculeata (Leuenberger, 1986)] follow similar phylogeneticpatterns. Caribbean island endemics belonging to these polyphyletic genera are notplaced in the clades that have their generitypes. In contrast, West Indian threatenedendemics in the polyphyletic genera Elekmania [generitype: E. barahonensis(Nordenstam, 2006)], Guettarda [generitype: G. speciosa (Jarvis, 2007)], Mollugo(Molluginaceae) [generitype: M. verticillata (Jarvis, 2007)] belong to the clades thathave the types of these genera.

The phylogenetic patterns of three other genera with endemic species appear tohave taxonomic implications and we believe that will need to be addressed in thefuture. The placement of the Critically Endangered species Phyllomelia coronatawithin the Cuban genusMazaea (Rubiaceae), makes the latter paraphyletic (Manns &Bremer, 2010). Likewise, Basiphyllaea (Orchidaceae) [with the Endangered (EN)species B. carabiaiana] is paraphyletic with the North American genus Hexalectris(Orchidaceae) (Sosa, 2007). Ginoria (with three threatened species) is also

Caribbean Island Threatened Seed Plants 535

Author's personal copy

paraphyletic, as the clade that has all of the species of this genus also includesTetrataxis (Graham, 2010).

Discussion

Our review finds that a small proportion of the endemic threatened flora of the Caribbeanislands has been the subject of molecular systematic. The general finding was that mostrareWest Indian seed-plants have evolved from lineages largely or entirely confined to theCaribbean Basin. However, in this study we have also shown that several of the endemicspecies have unique phylogenetic patterns. These species have a high priority for conser-vation not only because of their Endangered or Critically Endangered status [sensu IUCN(1980, 2001)] but because of their phylogenetic placements.

Few of the molecular studies of the threatened species support links between theCaribbean Islands and the OldWorld. However; in a previous review we reported that atleast three endemic genera, Narvalina (Asteraceae), Selleophytum (Asteraceae), andSiemensia (Rubiaceae) are sister to different clades from Polynesia and the South Pacific(Namoff et al., 2010b) suggesting phytogeographical links with these remote regions.The Tropical Sea Way connected the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean until the latePliocene (ca. 4 mya; Coates, 1997). This dispersal route was enhanced by theCircumtropical Current, which ran from the coasts of Brazil to the Pacific (Collinset al., 1996). Once the Panama Isthmus was formed, this geographical connectiondisappeared and this current became an important part of the Gulf Stream.

The Caribbean Islands have had a complex environmental history and have beenseverely affected by eustatic/isostatic sea-level changes, climatic changes, volcanism,and migration of lithospheric plate boundaries (Iturralde-Vinent & MacPhee, 1999;Iturralde-Vinent, 2006). It is suggested that prior to the middle Eocene (~ 49 mya) theislands went through several waves of emergence and submergence, but it is only afterthis geological epoch that the Caribbean Islands started a period of “sustained emer-gence” (Graham, 2003a, 2003b). According to this model, the middle Eocene is consid-ered as the starting point for the current fauna and flora of the Antilles (Iturralde-Vinent&MacPhee, 1999; Graham, 2003a, 2003b). Thus, the flora of the Caribbean Islands isrelatively “recent” when compared with that of South and North America.

Despite this relative young age, our review shows that several of the threatenedspecies are part of lineages that are sister to groups with a large number of taxa andclades. They represent the only surviving elements of these early divergent lineages. Afull review concerning to what extent this phylogenetic pattern is followed by otherendemics is outside the scope of this study; however, a review focusing on the endemicgenera (Francisco-Ortega et al., 2007) found that Verhuellia, a genus with three speciesendemic in Cuba and Hispaniola, is sister to the rest of the Piperaceae (Wanke et al.,2006; Samain et al., 2008). The significance of this finding is that this family is one of theearly-branching species-poor groups of angiosperms (as defined by Soltis et al., 2005).Other endemic genera follow similar patterns, including the endemic legumesArcoa, andPictetia as they are the only representatives of early divergent lineages in theUmtiza andthe Ormocarpum clade, respectively (Lavin et al., 2001; Wojciechowski et al., 2004;Bruneau et al., 2008; Lavin & Beyra Matos, 2008). Likewise, two Antillean orchidgenera,Dilomilis andNeocogniauxia form a clade sister to the subtribe Pleurothallidinae

536 N. Oleas et al.

Author's personal copy

(Van Den Berg et al., 2009). Similarly the Caribbean genus Ekmanianthe (Bignoniaceae)is sister to Tabebuia (Bignoniaceae) (Grose & Olmstead, 2007) and the Caribbean genusBellonia (Gesneriaceae) is sister to the tribe Gesnerieae (Martén-Rodríguez et al., 2010).

Our review has shown that the results obtained by us regarding the unique phyloge-netic placement of some of the threatened endemic species of the Caribbean Islands arealso found in other studies. They stress the conservation relevance of the CaribbeanIsland Biodiversity Hotspot because of its: (1) high number of endemics, (2) high rate ofhabitat loss, and (3) unique branches of the tree of life.

Acknowledgments We dedicate this paper to Dr. Victoria Sosa in recognition for her contributions to theadvancement of molecular systematics in Latin America. Nora Oleas thanks Fairchild Tropical Garden andFlorida International University for their support to attend the “10th Congreso Latinoamericano deBotánica”. We are grateful to Dr. Fabián Michelangeli and Prof. Richard Olsmtead for their insightsconcerning taxonomy of the Melastomataceae and Bignoniaceae, respectively. Thanks are due Dr. LarryNoblick and Dr. Scott Zona for their help on the biogeography of Caribbean palms, and to Dr. Johan Rovafor helping in tracking taxonomic literature pertinent to Rondeletia. Dr. Brian Boom and an anonymousreferee critically reviewed the manuscript. This is contribution 209 from the Tropical Biology Program ofFlorida International University.

Literature Cited

Andrus, N., A. Tye, G. Nesom, D. Bogler, C. Lewis, R. Noyes, P. Jaramillo & J. Francisco-Ortega.2009. Phylogenetics of Darwiniothamnus (Asteraceae: Astereae)—Molecular evidence for multipleorigins in the endemic flora of the Galápagos Islands. J. Biogeogr. 36: 1055–1069.

Bécquer-Granados, E. R., K. M. Neubig, W. S. Judd, F. A. Michelangeli, J. R. Abbott & D. S.Penneys. 2008. Preliminary molecular phylogenetic studies in Pachyanthus (Miconieae,Melastomataceae). Bot. Rev. 74: 37–52.

Benson, D. A., I. Karsch-Mizrachi, D. J. Lipman, J. Ostell & E. W. Sayers. 2011. GenBank. NucleicAcids Res. 39: D32–D37.

Berazaín-Iturralde, R., F. Areces-Berazaín, J. C. Lazcano-Lara & L. R. González-Torres. 2005. Listaroja de la flora vascular cubana. Documentos 4. Jardín Botánico Atlántico de Gijón, Gijón.

Bogler, D. & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2004. Molecular systematic studies in cycads: evidence from trnLintron and ITS2 rDNA sequences. Bot. Rev. 70: 260–273.

Borhidi, A. & O. Muñiz. 1983. Catálogo de plantas cubanas amenazadas o extinguidas. EditorialAcademia, La Habana.

——— 2010. The inclusion of Stevensia Poit. (Rondeletieae, Rubiaceae) into Rondeletia L. Acta Bot.Hung. 53: 247–249.

Bruneau, A., M. Mercure, G. P. Lewis & P. S. Herendeen. 2008. Phylogenetic patterns and diversifi-cation in the caesalpinioid legumes. Botany 86: 697–718.

Burke, J. M., A. Sánchez, K. Kron & M. Luckow. 2010. Placing the woody tropical genera ofPolygonaceae: a hypothesis of character evolution and phylogeny. Amer. J. Bot. 97: 1377–1390.

Burton, F. J. 2008. Threatened plants of the Cayman Islands. The red list. Kew Publishing, London.Caraballo-Ortiz,M.A.&E. Santiago-Valentín. 2011. The breeding system and effectiveness of introduced and

native pollinators of the endangered tropical tree Goetzea elegans (Solanaceae). J. Pollin. Biol. 4: 26–33.Cariaga, K. A., J. F. Pruski, R. Oviedo, A. A. Anderberg, C. E. Lewis & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2008.

Phylogeny and systematic position of Feddea (Asteraceae: Feddeeae): a taxonomically enigmatic andcritically endangered genus endemic to Cuba. Syst. Bot. 33: 193–202.

CentroNacional de Biodiversidad. 2011. Categorías de amenazas para la flora cubana (ordenado según la últimaevaluación asignada por especialistas cubanos). CentroNacional de Biodiversidad (CeNBio), Cuba. Availablein the internet at: http://www.ecosis.cu/cenbio/biodiversidadcuba/varios/listarojaflora_cuba_amenaza.htm.

Chew, T., E. De Luna & D. González. 2010. Phylogenetic relationships of the pseudobulbous Tillandsiaspecies (Bromeliaceae) inferred from cladistic analyses of ITS 2, 5.8S ribosomal RNA gene, and ETSsequences. Syst. Bot. 35: 86–95.

Caribbean Island Threatened Seed Plants 537

Author's personal copy

Coates, A. G. 1997. The forging of Central America. Pp 1–37. In: A. G. Coates (ed). Central America: anatural and cultural history. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Collins, L. S., A. F. Budd & A. G. Coates. 1996. Earliest evolution associated with closure of the TropicalSeaway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93: 6069–6072.

Cuenca, A., J., Dransfield & C. B. Asmussen-Lange. 2009. Phylogeny and evolution of morphologicalcharacters in tribe Chamaedoreeae (Arecaceae). Taxon 58: 1092–1108.

Donaldson, J. (ed.). 2003. Status survey and conservation action plan. Cycads. IUCN, The WorldConservation Union, Gland, Switzerland. Available in the internet at: http://data.iucn.org/dbtw-wpd/edocs/2003-010.pdf.

Farr, E. R., J. A. Leussink & F. A. Stafleu (eds.). 1979. Index nominum genericorum (plantarum).Volume II Eprolithus—Peersia. Regnum Veg. 101: 631–1276.

Francisco-Ortega, J., E. Santiago-Valentín, P. Acevedo-Rodríguez, C. Lewis, J., III Pipoly, A. W.Meerow & M. Maunder. 2007. Seed plant genera endemic to the Caribbean Island biodiversityhotspot: a review and a molecular phylogenetic perspective. Bot. Rev. 73: 183–234.

Gargominy, O. 2003. Biodiversité et conservation dans les collectivités françaises d’outre-mer. CollectionPlanète Nature. Comité français pour l’UICN, Paris, France. Available in the internet at: http://www.uicn.fr/Biodiversite-outre-mer-2003.html.

Gómez-Acevedo, S., L. Rico-Arce, A. Delgado-Salinas, S. Magallón & L. E. Eguiarte. 2010.Neotropical mutualism between Acacia and Pseudomyrmex: phylogeny and divergence times.Molec. Phylogenet. Evol. 56: 393–408.

González-Torres, L. R., A. T. Leiva Sánchez, R. Rankin Rodríguez & A. Palmarola Bejerano. 2007.Categorización preliminar de taxones de la Flora de Cuba—2007. Jardín Botánico Nacional, La Habana.

Government of Jamaica. 2000. The endangered species (conservation and regulation of trade) act, 2000.Available in the internet at: http://www.moj.gov.jm/laws/statutes/The%20Endangered%20Species%20(Protection,%20etc.%20Act.pdf.

Graham, A. 2003a. Historical phytogeography of the Greater Antilles. Brittonia 55: 357–383.——— 2003b. Geohistorical models and Cenozoic paleoenvironments of the Caribbean region. Syst. Bot.

28: 378–386.Graham, S. A. 2010. Revision of the Caribbean genus Ginoria (Lythraceae), including Haitia from

Hispaniola. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 97: 34–90.Grose, S. O. & R. G. Olmstead. 2007. Taxonomic revisions in the polyphyletic genus Tabebuia s. l.

(Bignoniaceae). Syst. Bot. 32: 660–670.Hágsater, E. & V. Dumont (eds). 1996. Orchids: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN, Gland.Iturralde-Vinent, M. A. & R. D. E. MacPhee. 1999. Paleogeography of the Caribbean region: implica-

tions. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 238: 1–95.——— 2006. Meso-Cenozoic Caribbean paleogeography: implications for the historical biogeography of

the region. Int. Geol. Rev. 48: 791–827.IUCN. 1980. How to use the IUCN red data Book categories. Threatened Plants Unit and IUCN, Kew.____. 2001. IUCN red list categories and criteria: version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission. IUCN,

Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, England. Available in the internet at: http://www.redlist.org/info/categories_criteria2001.

———. 2011. 2011 IUCN red list of threatened species. Available in the internet at: http://www.redlist.org.Jarvis, C. 2007. Order out of chaos. Linnaen plant names and their types. The Linnean Society of London

& The Natural History Museum, London.Jestrow, B., G. Proctor & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2008. Lasiocroton trelawniensis (Euphorbiaceae), a

critically endangered species from the Cockpit Country of Jamaica, belongs to Bernardia(Euphorbiaceae). Bot. Rev. 74: 166–177.

———, F. Jiménez Rodríguez & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2010. Generic delimitation in the Antillean Adelieae(Euphorbiaceae) with description of the Hispaniolan endemic genus Garciadelia. Taxon 59: 1801–1814.

____, J. Gutiérrez Amaro & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2011. Islands within islands: a molecular phylogeneticstudy of the Leucocroton alliance (Euphorbiaceae) and within the serpentinite archipelago of Cuba. J.Biogeogr. 39: 452–464.

Kelly, D. L. 1988. The threatened flowering plants of Jamaica. Biol. Conservation 46: 201–216.Lavin, M. & A. Beyra Matos. 2008. The impact of ecology and biogeography on legume diversity,

endemism, and phylogeny in the Caribbean region: a new direction in historical biogeography. Bot.Rev. 74: 178–196.

———, M. F. Wojciechowski, A. Richman, J. Rotella, M. J. Sanderson & A. Beyra Matos. 2001.Identifying Tertiary radiations of Fabaceae in the Greater Antilles: alternatives to cladistic vicarianceanalysis. Int. J. Pl. Sci. 162: S53–S57.

538 N. Oleas et al.

Author's personal copy

———,———, P. Gasson, C. Hughes & E. Wheeler. 2003. Phylogeny of Robinioid legumes (Fabaceae)revisited: Coursetia and Gliricidia recircumscribed, and a biogeographical appraisal of the Caribbeanendemics. Syst. Bot. 28: 387–409.

Leiva, A. & L. R. González-Torres. 2010. Results of the annual meeting of the Cuban specialist group.Bissea 4(1): 2. Available in the internet at: http://www.uh.cu/centros/jbn/descargas/bissea/bissea%204(1)%20march%202010%20english.pdf.

Leuenberger, B. E. 1986. Pereskia (Cactaceae). Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 41: 1–141.Manns, U. & B. Bremer. 2010. Towards a better understanding of intertribal relationships and stable tribal

delimitations within Cinchonoideae s.s. (Rubiaceae). Molec. Phylogenet. Evol. 56: 21–39.Martén-Rodríguez, S., C. B. Fenster, I. Agnarsson, L. E. Skog & E. A. Zimmer. 2010. Evolutionary

breakdown of pollination specialization in a Caribbean plant radiation. New Phytol. 188: 403–417.Maunder, M., A. Leiva, E. Santiago-Valentín, D. W. Stevenson, P. Acevedo-Rodríguez, A. W.

Meerow, M. Mejía, C. Clubbe & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2008. Plant conservation in the CaribbeanIsland biodiversity hotspot. Bot. Rev. 74: 197–207.

———, M. Abdo, R. Berazain, C. Clubbe, F. Jiménez, A. Leiva, E. Santiago-Valentín & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2011. The plants of the Caribbean islands: a review of the biogeography, diversity andconservation of a storm-battered biodiversity hotspot. Pp 154–178. In: D. Bramwell & J. Caujapé-Castells (eds). The biology of island floras. Cambridge University Press, London.

McDowell, T. & B. Bremer. 1998. Phylogeny, diversity and distribution in Exostema (Rubiaceae):implications of morphological and molecular analyses. Pl. Syst. Evol. 212: 215–246.

Meerow, A. W., J. Francisco-Ortega, T. Ayala-Silva, D. Stevenson & K. Nakamura. 2012. Populationgenetics of Zamia in Puerto Rico, a study with ten SSR loci. Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 106: 204–223.

———, L. Noblick, J. W. Borrone, T. L. P. Couvreur, M. Mauro-Herrera, W. J. Hahn, D. N. Kuhn, K.Nakamura, N.H.Oleas&R. J. Schnel. 2009. Phylogenetic analysis of sevenWRKYgenes across the palmsubtribe Attaleinae (Arecaceae) identifies Syagrus as sister group of the coconut. PLoS ONE 4(10): e7353.

———, D. Stevenson, J. Moynihan & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2007. Unlocking the coontie conundrum:the potential of microsatellite DNA studies in the Caribbean Zamia pumila complex (Zamiaceae).Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 98: 484–518.

Michelangeli, F., W. S. Judd, D. S. Penneys, J. D., Jr. Skean, E. R. Bécquer-Granados, R. Goldenberg& C. V. Martin. 2008. Multiple events of dispersal and radiation of the tribe Miconieae(Melastomataceae) in the Caribbean. Bot. Rev. 74: 53–77.

Motley, T. J., K. J. Wurdack & P. G. Delprete. 2005. Molecular systematics of the Catesbaeeae-Chiococceae complex (Rubiaceae): flower and fruit evolution and biogeographic implications. Amer.J. Bot. 92: 316–329.

Namoff, S., C. E. Husby, J. Francisco-Ortega, L. R. Noblick, C. E. Lewis & M. P. Griffith. 2010a.How well does a botanical garden collection of a rare palm capture the genetic variation in a wildpopulation? Biol. Conservation 143: 1110–1117.

———, Q. Luke, F. Jiménez, A. Veloz, C. E. Lewis, V. Sosa, M. Maunder & J. Francisco-Ortega.2010b. Phylogenetic analyses of nucleotide sequences confirm a unique plant intercontinental disjunc-tion between tropical Africa, the Caribbean, and the Hawaiian Islands. J. Pl. Res. 123: 57–65.

Nordenstam, B. 2006. New genera and combinations in the Senecioneae of the Greater Antilles.Compositae Newslett. 44: 50–73.

Oldfield, S. (ed). 1997. Cactus and succulent plants: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN, Gland.Olmstead, R. G., L. Bohs, H. A. Migid, E. Santiago-Valentín, V. F. García & S. M. Collier. 2008. A

molecular phylogeny of the Solanaceae. Taxon 57: 1159–1181.Osborne, R., M. Calonje, K. D. Hill, L. Stanberg & D. W. Stevenson. 2012. The world list of Cycads/La

lista mundial de cícadas. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 106: 480–508.Peguero, B. & F. Jiménez. 2011. Inventario y estado de conservación de plantas exclusivas de la

República Dominicana. Moscosoa 17: 29–57.Penneys, D. S., F. A. Michelangeli, W. S. Judd & F. Almeda. 2010. Henrietteeae (Melastomataceae): a

new neotropical berry-fruited tribe. Syst. Bot. 35: 783–800.Peterson, P. M., K. Romaschenko & G. Johnson. 2010. A classification of the Chloridoideae (Poaceae)

based on multi-gene phylogenetic trees. Molec. Phylogenet. Evol. 55: 580–598.Pollard, B. J. & C. Clubbe. 2003. Status Report for the British Virgin Islands’ Plant Species Red List.

National Parks Trust, British Virgin Islands & Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available in the internetat: http://www.kew.org/science/directory/projects/annex/BVIStatusReport.pdf.

Pratt, C. & K. Lindsay. 2008. Red list of vascular plants of Antigua and Barbuda. EnvironmentalAwareness Group of Antigua & Barbuda 4: 1–24.

Caribbean Island Threatened Seed Plants 539

Author's personal copy

Pridgeon, A. M., P. J. Cribb, M. W. Chase & F. N. Rasmussen (eds). 2005. Genera Orchidacearum.Volumen 4 Epidendroideae (Part One). Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Purvis, A., J. L. Gittleman & T. Brooks. 2005. Phylogeny and conservation. Pp 1–16. In: A.Purvis, J. L. Gittleman & T. Brooks (eds). Phylogeny and conservation. Cambridge UniversityPress, Cambridge.

Rankin-Rodríguez, R. & F. Areces-Berazaín. 2003. Contribución a la actualización taxonómica ylocalización geográfica de especies amenazadas y endémicas en Cuba I. Rev. Jard. Bot. Nac. 24: 81–128.

Richardson, J. E., M. F. Fay, Q. C. B. Cronk, D. Bowman & M. W. Chase. 2000. A phylogeneticanalysis of Rhamnaceae using rbcL and trnL-F plastid DNA sequences. Amer. J. Bot. 87: 1309–1324.

Roncal, J., S. Zona & C. E. Lewis. 2008. Molecular phylogenetic studies of Caribbean palms (Arecaceae)and their relationships to biogeography and conservation. Bot. Rev. 74: 78–102.

Rova, J. H. E., P. G. Delprete & B. Bremer. 2009. The Rondeletia complex (Rubiaceae): an attempt to useITS, rps16, and trnL-F sequence data to delimit Guettardeae, Rondeletieae, and sections withinRondeletia. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 96: 182–193.

Royal Botanic Gardens – Kew. 2011. Kew bibliographic databases. Available in the internet at: http://kbd.kew.org/kbd/aboutpage.do.

Salazar, J. & K. Nixon. 2008. New discoveries in the Canellaceae in the Antilles: how phylogeny cansupport taxonomy. Bot. Rev. 74: 103–111.

Samain, M.-S., G. Mathieu, S. Wanke, C. Neinhuis & P. Goetghebeur. 2008. Verhuellia revisited—Unravelling its intricate taxonomic history and a new subfamilial classification of Piperaceae. Taxon57: 583–587.

——— & ———. 2004. Historical biogeography of Caribbean plants: introduction to current knowledgeand possibilities from a phylogenetic perspective. Taxon 53: 299–319.

——— & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2008. Plant evolution and biodiversity in the Caribbean Islands–Perspectives from molecular markers. Bot. Rev. 74: 1–4.

Schaefer, S., A. Kocyan & S. S. Renner. 2008. Linnaeosicyos (Cucurbitaceae): a new genus forTrichosanthes amara, the Caribbean sister species of all Sicyeae. Syst. Bot. 33: 349–355.

Smith, M. L., S. B. Hedges, W. Buck, A. Hemphill, S. Inchaustegui, M. A. Ivie, D. Martina, M.Maunder & J. Francisco-Ortega. 2004. Hotspots revisited: earth’s biologically richest and mostthreatened terrestrial ecoregions. Pp 112–118. In: R. A. Mittermeier, R. R. Gil, M. Hoffman, J. Pilgrim,T. Brooks, C. G. Mittermeier, J. Lamoreux & G. A. B. da Fonseca (eds). Hotspots revisited: earth’sbiologically richest and most threatened terrestrial ecoregions. CEMEX, Mexico.

Soltis, D. E., P. S. Soltis, P. K. Endress & M. W. Chase. 2005. Phylogeny and evolution of Angiosperms.Sinauer Associates, Sunderland.

Sosa, V. 2007. A molecular and morphological phylogenetic study of subtribe Bletiinae (Epidendreae,Orchidaceae). Syst. Bot. 32: 34–42.

Steinmann, V. W., B. Van Ee, P. E. Berry & J. Gutiérrez. 2007. The systematic position of Cubanthusand other shrubby endemic species of Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) in Cuba. Anal. Jard. Bot. Madrid 64:123–133.

Thomson Reuters. 2011. ISI web of knowledge. Available in the internet at: http://apps.isiknowledge.com.Torres-Santana, C. W., E. Santiago-Valentín, A. T. Leiva Sánchez, B. Peguero & Colin Clubbe. 2010.

Conservation status of plants in the Caribbean Island Biodiversity Hotspot. Proceedings of the 4thGlobal Botanic Gardens Congress, Dublin, Ireland, June 2010. Available in the internet at: http://www.bgci.org/files/Dublin2010/papers/Torres-Santana-Christian.pdf.

Trénel, P., M. H. Gustafsson, W. J. Baker, C. B. Asmussen-Lange, J. Dransfield & F. Borchsenius.2007. Mid-Tertiary dispersal, not Gondwanan vicariance explains distribution patterns in the wax palmsubfamily (Ceroxyloideae: Arecaceae). Molec. Phylog. Evol. 45: 272–288.

Urquiola Cruz, A., L. González-Oliva, R. Novo Carbo & Z. Acosta Ramos. 2010. Libro rojo de la floravascular de la provincia de Pinar del Río. Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante. Campus de SanVicente, Spain.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2011. Endangered species program. Threatened/endangered plants in theU.S. Species reports. Listed plants. Available in the internet at: http://ecos.fws.gov/tess_public/pub/listedPlants.jsp.

Van Den Berg, C., W. E. Higgins, R. L. Dressler, W. M. Whitten, M. A. Soto-Arenas, A. Culham&M.W. Chase. 2009. A phylogenetic study of Laeliinae (Orchidaceae) based on combined nuclear andplastid DNA sequences. An. Bot. 104: 417–430.

Van Ee, B. W., P. E. Berry, R. Riina & J. E. Gutiérrez Amaro. 2008. Molecular phylogenetics andbiogeography of the Caribbean-centered Croton subgenus Moacroton (Euphorbiaceae s.s.). Bot. Rev.74: 132–165.

540 N. Oleas et al.

Author's personal copy

Wanke, S., M.-S. Samain, L. Vanderschaeve, G. Mathieu, P. Goetghebeur & C. Neinhuis. 2006.Phylogeny of the genus Peperomia (Piperaceae) inferred from the trnK/matK region (cpDNA). Pl.Biol. 8: 93–102.

Wojciechowski, M. F., M. Lavin & M. J. Sanderson. 2004. A phylogeny of legumes (Leguminosae)based on analysis of the plastid matK gene resolves many well-supported subclades within the family.Amer. J. Bot. 91: 1846–1862.

Zgurski, J. M., H. S. Rai, Q. M. Fai, D. J. Bogler, J. Francisco-Ortega & S. W. Graham. 2008. Howwell do we understand the overall backbone of cycad phylogeny? New insights from a large, multigeneplastid data set. Molec. Phylog. Evol. 47: 1232–1237.

Zona, S., R. Verdecia, A. Leiva-Sánchez, C. E. Lewis & M. Maunder. 2007. Conservation status ofWest Indian palms (Arecaceae). Oryx 41: 300–305.

Caribbean Island Threatened Seed Plants 541

Author's personal copy