No flesh, no gods; atheist-vegetarian worldviews, and the hegemony of meat.

Transcript of No flesh, no gods; atheist-vegetarian worldviews, and the hegemony of meat.

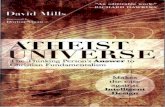

Image 1.

Title: ‘No flesh, no gods; atheist-vegetarianworldviews, and the hegemony of meat.’

Student: 586407

MA Anthropology of Food

University of London – SOAS

Supervisor: Dr Jakob Klein

Word Count: 9990

I have read and understood regulation 17.9 (Regulations for Students

of SOAS) concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all material

presented for examination is my own work and has not been written

for me, in whole or in part, by any other person(s). I also

undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or

unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the

work which I present for examination. I give permission for a copy

2

of my dissertation to be held at the School’s discretion, following

final examination, to be made available for reference.

Signed………………………………………………

Date…………………………………………………

“We must respect the other fellow's religion, but only in the sense and to the extent

that we respect his theory that his wife is beautiful and his children smart.” -

H.L. Mencken

3

“You have just dined, and however scrupulously the slaughterhouse is concealed in

the graceful distance of miles, there is complicity.” - Ralph Waldo Emerson

Abstract

This dissertation focuses upon a group of vegetarians which are

members of an English-speaking, online atheist community, an

investigation of their Weltanschauug (worldview) for meat-avoidance,

and the subsequent discourse analysis undertaken for this study. One

aim of this study is achieved by an ‘online ethnography’ that

discusses the views of atheist-vegetarians towards the question; “Is

there a link between atheism/vegetarianism?”. This method

understands that analysing text can overcome context and time

constraints in consideration of transcendent perspectives such as

worldviews. Furthermore, a consideration of atheist and vegetarian

literature is explored to complement the nature of the ethnography;

4

‘Atheist-vegetarianism’, human and animal relationships, and the

cultural politics of meat were chosen. This work highlights the role

of speciesism within theistic/atheist and vegetarian discourse, and

the construction of morality through sources of science, rationality

and consumption ideals. Furthermore, this work hopes to highlight

the subtle hegemonic ways in which contemporary meat consumption is

maintained, not only by traditional consumption rituals, but by a

non-exclusive list of economic, anthropocentric, nutritional, and

philosophical paradigms. If we use Heidegger’s school of

postmodernist thought to treat meat-free lifestyles as autonomous

worldviews, we can similarly compare these perceptions with wider

socio-political/economic ‘meat practices’ which maintain meat

consumption in order for atheist-vegetarianism to potentially

provide a new form of moral theory. This ‘moral theory’, akin to

Carole Adams’ (1990) feminist-vegetarian writings, would provide a

new look at how moral vegetarianism could highlight the

presupposition that religious discourse holds over the consumption

of meat, and of man’s anthropocentrism towards animals.

5

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Professor Harry West, Dr Jakob Klein,

and the staff of SOAS for their expertise in orchestrating such a

stimulating MA course. It has provided at times much anxiety, food

for thought, and joy in learning unique concepts.

6

Contents

Abstract...........................................................4

Acknowledgements...................................................5

Contents...........................................................6

1. Introduction...................................................7

1.1 Research Rationale...........................................8

1.2 Aims.........................................................9

1.3 Hypothesis...................................................9

1.4 Hypothesis Statement:.......................................10

1.5 Context.....................................................10

2. Literature Review.............................................13

2.1 The ‘isms’ as valuable worldviews...........................14

2.2 Human-Animal Relationships..................................17

2.3 Atheist-vegetarianism?......................................19

2.4 The Cultural Politics of Meat...............................21

3. Methodology and Ethics........................................24

7

3.1 ‘The Field Site’............................................26

4. Ethnographic Discussion.......................................30

5. Conclusion....................................................35

6. References....................................................37

7. Appendix......................................................47

8

1. Introduction

Just as the fish of the sea cannot understand the ecological

relationship of the water that surrounds them or how it comes to

define their existence; neither can we as humans fully understand

the ‘social and ideological’ which presupposes ‘being’ (Smith, 1996)

and that which we consume. In the context of this dissertation I

thus refer to alternative ‘worldviews’ pertaining religious belief

and eating practises; which are atheist and vegetarian.

These ‘alternative lifestyle paradigms’ and the discourses which

define them are interesting to study in relation to what we perceive

to be ‘normal’, and are often thought of as ‘lifestyles ‘in the non-

political sense. One example of this has been vegetarianism in the

latter half of the 20th century which has gained support not only

from the individual and collective alike in terms of a

health/ethical standpoint, but academically as a legitimate solution

to some of the world’s food chain issues; such as sustainability

(European Vegetarian Union, 2009). Interestingly, this ‘bloodless

revolution’ (Stuart, 2006) did not singularly occur in the

‘politically free’ ‘Tocquevillian’ (1893) sense (civil societies),

9

even as some (Jabs, Devine and Sobal, 1998) have noted that over 7%

of the United States populace (as of 1998) adopted a vegetarian

diet; this holds in stark contrast to that of India where an

estimated majority abstain from meat (Vegetarians.NZ, 2013). In this

way it appears that the ‘motivations’ of vegetarians cross a

spectrum of political, ethical and religious teleological ‘ends’,

both intrinsic and extrinsic. Most concurrently, vegetarianism and

atheism as perceived ‘minority cultures’ have only really been

investigated as food choice paradigms, and have not been considered

for their moral value in light of the nihilism surrounding the

values of consumption in the postmodern age. I believe this is in

line with how Shultz (2012: 222) perceives the separation of people

and food from nature in respect of how ‘globalisation’ has rendered

food ‘unrecognisable’; so have our morals dislodged with regards to

the eating /slaughtering of animals for food.

1.1 Research Rationale

Attempting to answer questions which surround the notion of

identity, morality and consumption can provide us with an

extremely valuable understanding of how we as humans define

‘the self’ in relation to animals, and towards each other as

10

harbourers of culture. I firstly position religious belief,

eating practises, and the current ‘productivist’culture of our

food chains as “historicised” narratives (Heidegger’s

‘hegemonic habits’); these are treated as legitimate

paradigmatic influences which dictate our behaviour). To this

point I also treat worldviews as ‘man’s existential

homogeneous perspective’, which as Heidegger suggests can

introduce a narrative which extends into the future, this can

take the form of discourses such as ‘Slow Food’ which

incorporate a temporal consideration as a rationale to elude

the negative effects of current ‘Fast Food’ industries. These

narratives manifest themselves as positions on a spectrum of

teleological ‘ends’ or assumptions about the origins, meanings

and ‘purpose’ of life. Therefore, atheism and vegetarianism

can be used as platforms to similarly transcend traditional

notions of consumption. In this way, this discussion will add

to the relevant literature on alternative food philosophy,

secular scholarship, and to challenge the mainstream view of

atheism/vegetarianism as ‘anti’ constructs which seek to

destroy ‘the norm’; but ones which have valid solutions to

breaking ‘habits’. This form of study, ‘philosophy, ideology

and practice’, are greatly beneficial in synthesising in an

11

anthropological manner - the lifestyle paradigms under

‘observation’.

1.2 Aims

Three aims are set to bring to light specific considerations inside

the literature and ‘online ethnography’; they are constructed in

order to bring new discursive and theoretical focus on any

links/barriers between the fields of atheism and vegetarianism.

1. How do atheist-vegetarians construct their identity in

relation to those they label as ‘believers’ or ‘non-

vegetarians’.

2. How do atheist-vegetarians negotiate their sense of morality

and consumption ethic without religion with regards to

postmodern thought?

3. Does atheism-vegetarianism provide a new moral theory for

meat-free consumption?

12

1.3 Hypothesis

The following hypothesis is not provided to force a ‘Weberian’ ideal

type (Brunn and Whimster, 2012) of what constitutes atheist-

vegetarian worldviews, but to understand those who hold such beliefs

against classical stereotypes and contemporary definitions, such as

‘The New Atheists’ (Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens and Sam

Harris). Such mainstream representations of atheists/vegetarians

show how collective manifestations of theology, meat-resistance

avoidance (mainly through modern media and individual experience)

avoid the voice of living communities to perpetrate existing

hegemonic paradigms This misrepresentation allures itself to the age

old debate of theism vs. atheism which is at this time of writing

still subjected to narratives formed in the Medieval and

Enlightenment eras (I.E - What is good, evil, right or wrong).

1.4 Hypothesis Statement:

“Atheist-vegetarian practices, ideology and representation

through online media highlight an omission of representation

13

within previous literature and media on the subject of ‘moral’

vegetarianism. Atheist-vegetarianism can negate traditional

stereotypes as a worldview towards a new moral theory; this

theory is designed to transcend (temporally) the restrictive

elements of the current ‘productivist’ paradigm which enforces

meat as a hegemonic device”.

1.5 Context

The year 2004 saw the release of Sam Harris’s The End of Faith: Religion,

Terror and the Future of Reason, whilst this was to be the start of a time

that ‘New Atheist’ literature would emerge, Harris (and his peers

Dawkins and Hitchens) were motivated by the terrorist attack on the

world trade centre in New York September 11th 2001, and of a growing

concern for religion as a fundamentalist pursuit. Situated around

this time, English populations describing themselves as ‘non-

religious’ or atheist almost double in the period between 2001 and

2011. At a growth of 18.9% of its total, the ‘non-religious’ have

contrasted sharply to the largest religious group - ‘Christian’,

which fell by 13% of its total to around 59% of the overall

population (Office for National Statistics, 2011). Though these

14

observations come at a fairly recent time we can be sure that they

do correlate to global political interventions, such as the wars in

the Middle East, tougher international migration laws (termed as

‘security issues’ (Humphrey, 2013) and a growing facet of

scholarship/media devoted to tackling, and interpreting religious

extremism (Miller, 2013). Whilst ‘correlation does not imply

causation’, how the above links with vegetarianism within atheistic

rhetoric, is not the aims of this study, but I will argue that

contemporary atheist/-vegetarians have specific constructions of

morality and discourse which reflect a deeper understanding of how

morality can be constructed in the post-modern sense through

consumption.

Similarly, vegetarianism in its own right has seen a massive

reaction to its popularity within the global media, not singularly

in its ‘Eastern’ forms (Hinduism, Buddhism etc.) or as a culinary

genre; but as a ‘secular activist lifestyle’ which has legitimate

solutions to environmental food production issues, and similarly as

a dietary choice which has required constant reflection from one’s

own ‘inherited culture’ (Beardsworth and Keil, 1992: 254).The recent

‘self-definition’ of atheism (Dawkins etc.) does not appear to have

manifested itself into rigorous discussion within anthropological

circles, it has been the philosophy of religion, and those not

traditionally for or against the eternal theism vs atheism debate

15

(Markham, 2010) which have perhaps contributed the most. This is

meant in the sense that some have analysed a history of atheism (the

subsequent progression of its discourse) and used this as context

for the ‘New Atheist’s’ argument, which Dawkins as the main

advocator of ‘New Atheism’ fails to do, as he enters the realm of

philosophy from the “armchair of the natural sciences”. For example,

Hyman (2010: 3 - 5) in his work ‘A Short History of Atheism’ relays that

atheism first gained recognition as discourse in England circa 1540

from Sir John Cheke in his translation of Plutarch’s ‘On Suspicion’, at

this time atheism was a direct response to religious doctrine, but

also became a fearful association with mass heresy, left-wing

politics, vegetarianism, and a construction of a dangerous ‘other’.

Furthermore, as Hyman (2010: 4) states, In France it was groups of

“…‘libertines’, erudites and skeptics, which faded away circa 1630 to return in

1655 as recognisable ‘atheists’, those which did not just question

deities but shared agnostic rhetoric - that one could disbelieve but

also reproduce a kind of beneficial ‘spirituality’ amongst others in

society whilst maintaining an ‘enlightened’ manner of scientific

investigation. What this information provides to the anthropologist

(Markham, 2010: 7 – 27), is that ‘fundamentalist-political’ atheism

in the modern sense now represents a reflection of a modern

‘secular/scientific society’, one of linear progression (a

teleological end) which states that reason, evidence and

16

experimental understanding trumps human interpretation; it is

essentially a materialist construction of the world, it does not

escape the dialectic of theism/atheism as they both are mutually

exclusive (one gives existence to the other). What is most

interesting is how New Atheists consider morality in light of

postmodernism, and even more so towards non-human animals as

advocators of natural science; such as speciesism. This idea

similarly manifests itself in atheist-vegetarian discussions in the

forms of ethics, neoliberalism (Miljkovic, Brester and March, 2003),

and the politics of eating as hegemonic practice. These rationales

are sufficient to wade through the complexity of online atheist-

vegetarian communities, the central lynchpin of which being that

these particular ‘peoples’ do not attend physical meetings; and so

online debates can often gain a wide array of transcendental

discussion.

17

2. Literature Review

The first obstacle which eludes a study of discourse is defining the

terms of its study and the context in which it is situated; it is

the task which all analytical studies undertake and is crucial to

determining exactly what is to be considered relevant. Not only does

this method highlight an authenticating process, it similarly

situates the study into a field of knowledge in which comparison,

analysis and interpretation can be made to gain legitimate

anthropological value as methodology. The validation of

interpretation within ‘social life’ is the main paradigmatic

challenge of postmodern anthropology (Dilley, 2002), this can be

achieved by Heidegger’s method of ‘stepping outside oneself’ to

perceive how habits and subjects relate to ‘being’.

This section will be devoted to a discussion of atheist and

vegetarian literature, specifically, attention will be paid to

ethnographic sources, yet the nature of the subject in question will

have influx from philosophical thought, and theological discussion.

18

This is crucial as the research methods of this dissertation have an

innate focus on ‘participant opinion’ or rhetoric – they do not

reveal ‘observable’ behaviours in a physical context as ‘practice’,

this means that the focus of ethnographic attention must link the

themes of participant discourse in a manner of transcendental

argument, but most importantly link to the social schema which

define the rhetoric of atheism and vegetarianism. Similarly, this

section begins with how atheism and vegetarianism can bring value to

anthropology to uncover the hegemony of meat through their

respective world views; this is not to suggest that for academic

purposes there are specific contexts or geographical locations of

particular interest. Often, in vegetarian lifestyle ‘encyclopaedias’

(Puskar-Pasewicz, 2010), and indeed in the field of modern

vegetarian media, it is often perceived that meat-avoidance has

never been anything other than a contemporary social, political or

health movement (Spencer, 1996). Much focus has been given to the

origins of The Vegetarian Society as a ‘lifestyle movement’, or even

the term itself which originated around the time of the 1840’s; this

was certainly the place where (as a health choice) vegetarianism

blossomed into the Western world and essentially was cross-

pollenated by a vast mixture of East-West philosophies, including

many religious and secular ideologies.

19

We can begin to perceive that vegetarianism and atheism are not

simply ‘anti’ movements seeking to destroy their philosophical

opposite; they harbour key ideas, often political, social or

ethical, which have a global agenda. Aside from speculating where

and when these ideals emerged, it is not the aim of this

dissertation to discuss an accurate ‘history’ of vegetarianism or to

create a discussion on the philosophies of meat consumption to reach

a proposed teleological end; it is to investigate an online society

that harbours a specific conception of vegetarianism through

atheism. Pairing this discussion with a short ‘online ethnography’,

and anthropological works surrounding the subjects of ‘worldviews’,

human-animal relationships, ‘atheist-vegetarianism’ and the cultural

politics of meat, this should introduce a different discursive

perspective on the origins of (moral, social or political)

vegetarianism but similarly how atheism is morally productive.

2.1 The ‘isms’ as valuable worldviews

Vegetarians have often been misrepresented in the west as a minority

culture, but overall, they have been stigmatised only slightly less

when compared to those with less discerning consumption habits; such

as smoking (Swanson, Rudman and Greenwald, 2001). Perhaps this has

20

been due to vegetarianisms’ historical representation as a

beneficial ethical/health movement which has entered into the realms

of popular media, science and philosophy (Saul, 2014) (Singer,

1980); even more so in the realms of masculinity and social dining

convention, where vegetarians have been portrayed as ‘non-normal’

and distinctly tricky diners (Curtis, 2011). These ‘omnivorous

legitimisations’ have often become part-focus for meat advocators to

argue for the continued slaughtering of animals as ‘normal

practice’, and so vegetarianism has been ideologically/politically

pigeon-holed as a left-wing movement, and as a pseudo-religion in

its own right. Similarly, atheists (a supposed ‘minority’) who are

estimated to stand at 13% of the world’s population (Win-Gallup

International, 2012) are subject to mistrust against the religious

majority. Like with vegetarianism, there has been much change

within the global perception of atheism as an ‘anti’ force, this can

be linked to the nature of the ‘New Atheists’ literature as

purveyors of science, philosophy and logic (Dawkins, 2006) (Harris,

2004) (Hitchens, 2007). What these ‘minority’ worldviews come to

represent anthropologically, are not generalised representations in

a spectrum of social movements, but collections of structures,

formations, and ideologies which come to define ‘buzzwords’

(Cornwall, 2007) like atheism and vegetarianism in the present era.

21

Why understanding the ‘isms’ as worldviews is an important pursuit,

lies in the notion that conflicting food choices have the ability to

reveal that what we perceive as ideologically ‘normal’ is often

harmful when unquestioned, this is especially relevant towards

agriculture, health, environment or food policy (Romo and Donovan-

Kicken, 2012: 406). The themes of identity, exclusion and inclusion

within the anthropology of food has been discussed at length, works

such as Maurice Bloch’s Commensality and Poisoning (1999: 135) highlighting

the ‘social conductivity’ and contestation of specific foods and

their transference of mimetic meaning. These ‘layered’

interpretations of social interaction (and even the ingredients

which constitute food (Belasco, 2005: 217 – 220)) are ‘flashpoints,’

of which link consumption practises to the ‘wider world’ which

consists of production, policy, cultural politics etc. Studies which

go beyond the focus on Western societies and traditional omnivorous

worldviews such as meat-eating as a diet (Ruby, 2011) are beginning

not only to question the natural sciences fixation with the

classification of diet, but the pre-existing paradigms of knowledge

which hold them (Sabate, 2003). These ‘ideal types’ (Bruun and

Whimster, 2012: xxiv) of diets as we know are just as ideologically

formed as any popular scripture on the subject of food, and often

relate to certain time periods, writings or popularised reactions -

cookbooks are a good example (Knight, 2011).

22

As pre-existing paradigms exist to perpetuate the label of

vegetarianism and atheism as a ‘minority’, ‘reactionary’ or ‘self-

indulgent’, we must consider like Jackson (2013: 3- 5), the ‘school

of suspicion’ (Marx, Nietzsche and Freud) to create a new moral

focus outside of the anthropocentrised platform of the religious, to

consider the overarching economic and political forces which

maintain consumption culture. It is for the purposes of this study

like many current sociological and anthropological enquiries around

the subject of vegetarianism and consumption, helpful to unsubscribe

from the trend of categorised ‘Multiple-Goals Perspectives’ (Romo

and Donovan-Kicken, 2012: 407), towards a form of Weltanschauug

(worldview) interpretation; that of Heidegger or Wilhelm Dilthey’s

Hermeneutic tradition (Naugle, 2002). This is to understand that the

communicatory interactions between those negotiating a ‘social

belonging’ with their ‘lifestyle agendas’ (vegetarianism/atheism) go

beyond traditional classifications that one’s ‘motivations’ may be

purely ‘moral’, ‘experience’ or ‘health’ based (Jabs, Devine and

Sobal, J. 1998), there is much to understand surrounding personal

lifestyle situations that ‘motivation’ studies leave behind. Other

main considerations to arise out of contemporary literature on

vegetarianism, are not only that meat-abstinence is a dynamic

practice constantly justified with ‘the creation/breaking down of

motivational goals’ (Ruby, 2011: 142), but the existence of barriers

23

to such consumption practice (sensory stimuli, habit and ‘social

networks’). Such studies as these are important as they do not

solely focus on macro fields such as ‘food safety, ‘artisan

production’, ‘food security’ or ‘food policy’, but synthesise these

factors in relation to the ground level practices of these ‘deviant

groups’ in the same manner that Belasco does with his Politics of Bread

(2005). Such focus on deviance is reflected in studies such as

Sneijder and Molder’s (2006) study: ‘Normalizing ideological food choice and

eating practices. Identity work in online discussions on veganism’. Like Sneijder and

Molder (2006) this dissertation takes the view that categorisation

distorts the value of ethnography in the sense that food choice,

class, gender etc. abstract the cultural value of investigation;

they are in themselves formations of a specific paradigmatic period.

On a similar level, it would be wrong to assume that the wider

societal factors which constitute vegetarianism somehow appeared in

a vacuum, that all identity is somehow a strict dichotomous

negotiation between ‘self’ interest (Turner, 1987) or ‘group’

identity (Tajfel, 1982) - as this is in Sneijder and Molder’s (2006)

study. What can be communicated from one participant to another (and

analysed for discursive meaning) is somewhat only partially

representative of a ‘structure’ or indeed of a ‘function’, this is

why further arguments will be investigated to understand ‘non-

traditional motivations’ such as the human relationship to animals,

24

environmentalism, and furthermore, to understand the relevance of

studying ‘deviant groups’. Ultimately, an ethnographic understanding

of such subcultures (be them atheist or vegetarian) would provide an

alternate method of unpicking the potential of worldviews, not in

terms of what constitutes their practice but a source of enquiry

which can reconceptualise how we perceive the hegemony of meat-

eating.

2.2 Human-Animal Relationships

In the study of food in ‘Western societies’, there exists a

consistent dichotomy of how humans and nature may relate and come to

define one other, especially in the structural-functionalist and

materialist paradigms (Mintz and Du Bois, 2002). As Ritvo (1987:3)

shows, the human/animal relationship after the period of

enlightenment in Europe revealed an exposed worldview that science

could make nature vulnerable; it renewed the nostalgia (with the

religious) and care that was ‘once apparent’ in earlier times such

as Medieval Europe. This is why Mullin (1999: 204) suggests

Christianity was interested in maintaining the taboo of bestiality,

and furthermore the hierarchy of certain ‘pet’ animals (such as dogs

25

for hunting) was to maintain the scale of human/animal divide and to

situate humans in the ‘food chain’ as closer to a divine creator.

Through this school of thought we begin to see through classical

ethnography that the human relationship with animals is one onto

which human’s project their agendas through thoughts and value

systems. This relationship is also one in which animals serve a

physiological purpose as food, what this can do for modern day

anthropology is to reflect the activities of societies large and

small (Palsson, 1996) and their definition of morality in relation

to meat consumption - it appears like Levi Strauss said; that

animals are becoming more and more as ‘things to think with’ rather

than just to eat. A prime example of this has been the hunters of

the Huaulu as portrayed in Valeri’s (2000) The Forest of Taboos. As a

hunter, after killing or trapping an animal, one would not begin

butchering a carcass in the immediate vicinity, this task would be

given to ‘an-other’ or a hunter, this is due to the ‘unbalancing’ of

nature which has occurred by taking the animals life. Here, the

sense of taboo does not lie within (albeit strict) choices of animal

flesh – but emphasis is placed upon the paradox of animal

consumption vs. the need to kill to survive (the process itself);

the greater the anguish which has been attached to a practice the

more we crave, yet despair the killing process, thus the need for

detachment (from nature). This is a common theme within the modern

26

world and its media (Stevens, 2014) as many observe the growing

reaction and detachment some meat-eaters face with their diet, and

although some traditional ‘artisan’ production methods seek to bring

back what was a ‘natural’ method of slaughter, most major

supermarkets, retailers and food conglomerates still distance the

consumer from the imagery of animals (in the form of semiotic

information).

The transformation of human-animal relationships has indeed been

defined by the act of slaughter, and as comparable to Valeri’s

(2000) case with the Huaulu, Fitzgerald (2010) makes the analysis

that ‘domestic’ societies rapidly became ‘post-domestic’ after the

industrial-evolution of the slaughterhouse. This post-domestication

is defined and maintained by the moral distancing that

slaughterhouses provide, this is on a similar level of how the

organisation of labour and physical location of institutionalised

slaughter has severe negative influences on social, health and

environmental welfare, such as drug/violence related crime, and

surges of bacteria related illness (Marcus, 2005). By the terms of

industrialised agriculture and technological progress in the 19th

century, human-animal relations and meat eating are thus an

extension and abstraction of violence/ product of utilitarian-based

philosophy; which notably arises in the 18th century (Mill, 1870).

The task of slaughtering and butchering an animal is now intertwined

27

with the human notion of efficiency (sterility) (Nietzsche’s

‘apollonian’ culture, (Whiteside and Tanner, 2003), this further

cements the human dominance over nature with an array of subtly, and

harms the use of ethical concerns to influence discourse on the

benefits to human nutrition (The Animal Studies Group, 2006); or

even the reinforcement of our genders. This is a cornerstone of the

vegetarian reaction which seeks to politicise animals ‘as level with

humans in nature’ as sapient beings. What the hidden world of

slaughter (and furthermore its exposure) provides, is a reflection

of ‘the post-modern world’ and its paradoxical role in shaping new

attitudes to ethical concerns such as human-animal relations. This

argument surrounds the ‘consumer confusion’, or Heidegger’s ‘habits

of Das Man’ (Smith, 1996: 175) which is perpetuated by

‘Technologisation’, this further conceptualises animals into

commodity terms which has benefits for meat-businesses (Wrenn,

2011). Again, the ignorance for vegetarianism as a minority movement

is representative of the ‘function’ of animals as ‘the

quintessential modern commodity’ (Torres, 2007), there are few

better sources for economic or cultural investment as one can find

within the trade of animals and their slaughter (produce, labour,

drug markets, animal testing etc.), the list is limitless. Indeed,

the problem of an anthropocentric worldview is similarly not

restricted to prosperous economic societies; it is the view of most

28

natural sciences that animals do not undergo the same none

‘biological-essentialism’ as given to the description of human

cultures and social interactions. This is why in a similar vein to

that of Adams (1990) feminist-vegetarian theory that closer

consideration should be given towards ‘anthro-sceptical’ social

sciences, or atheist-vegetarian arguments.

2.3 Atheist-vegetarianism?

Terms such as atheist-vegetarianism infer a partial metaphysical

conjunction of two social concepts; this should be looked upon as a

unique perspective in itself which has its own rhetoric and defining

‘culture’ as a worldviews, but one which must not be pigeon-holed as

a fixed point of opinion. I state this in relation to historic

arguments surrounding the religious/non-religious acceptance of

vegetarianism and the analysis in which acceptance has been studied

within the Anthropology of Food. One prime example has been Feeley-

Harnik’s (1981) work on The Meaning of Food in Early Judaism and Christianity, in

which she investigates scriptures which instil consumption practices

on the Abrahamic religions. What is apparent here is that although

major religions such as Judaism and Christianity have persuaded

followers to consume certain animals with divine rhetoric (and a

29

strong anthropocentric philosophical rationale), not all have

adhered to these historic ideologies, and a small number of reformed

Christians use the ‘man in gods image’ (as a reflection of his

ideology) argument to similarly state the basis of moral arguments

for meat abstinence (Largen, 2009). This is why some anthropologists

such as Harris (1985), have sought to understand religious doctrine

for the consumption of taboo animals using such examples as pigs in

Islam and beef in Hinduism. The conclusions that Harris makes, all

be them strictly of a Marxist fashion, is that historic religious

doctrine on meat consumption is the result of rational, contextual

economic/ecological arguments, such as the overbearing cost of

grains that rearing meat requires, this is then reaffirmed as

scripture and accepted in future recitals. Although many production

arguments such as these has been made, this materialist position

cannot tell us is why food taboos (if strictly ecological and

economic) continue to elude efforts to shake up the efficiency of

food production. Alternatively, one possible explanation could be

that the ‘social view’ of meat is bound up in the omnivores’

rhetoric of production as an elite human ability (as ‘progression’)

this could mean that as Murdoch and Miele (1999) suggest, that a

return to ‘nature’ needs to be construed as a future narrative lest it

be doomed to preconceptions of a return to primitivism.

30

Defining ‘atheist-vegetarianism’ can in this instance be thought of

as ‘an amoral resistance of anthropocentrism’ (Nietzsche, Clark and

Swensen, 1998) through non-belief, but also as a form of political

resistance through consumption. This suffices as an initial

‘motivation’ for the acceptance of a scientific nature within New

Atheism (mainly the theory of evolution) (DeLeeuw, Galen, Aebersold

and Stanton, 2007), but what we do know is, that “a lack of

perspective” does not imply ‘more of something else’, meaning one

could be a principled atheist-vegetarian because one is simply non-

religious and avoids meat for health reasons. What begins to emerge

here, is an understanding that the nominal labelling of a specific

worldview arises when it is required to show it’s ‘working’,

‘philosophy’ or ‘frame of measurement’ in order to justify itself as

a social movement. For example, theism is stereotypically fuelled by

belief, atheism by non-belief, agnosticism by principled

uncertainty, but in actual fact all three fundamentals (as their

stereotypes by scope cannot take into consideration those actually

‘practising’) are arguably shared by a multitude of rationales;

philosophies, beliefs, principles and social impact. From this, with

reference to ‘New Atheism’ we can begin to ask how and why ‘science’

is becoming a discursive ‘buzzword’ within the online atheist

community, in this manner ‘science’ changes from its dictionary

definition (as a spectrum of naturalistic and social investigations)

31

and becomes a homogenous way to describe and legitimise moral

principle (Thomas, 2010). Furthermore, we can begin to ask the same

questions of vegetarianism, in the way that it is partially upheld

within atheism (within this ethnography) to politically and

‘spiritually’ legitimise amoral worldviews with regards to

maintaining an atheist identity.

To conclude, atheism and vegetarianism in the present sense

(political, scientific, ‘New Atheist’) are reflections of ‘the

secular contemporary society’ (Hyman, 2010: 19 - 23), but they are

also a contestation of the ‘postmodern philosophy of this era’;

‘postmodernism’ and subsequently ‘atheist-vegetarianism’ are thus

not simply nihilistic by nature, but can be described as effective

tools to uncover and change modes of biased moral and situational

hegemony.

2.4 The Cultural Politics of Meat

Vegetarianism is a worldview that is more commonly being facilitated

to bring change to issues surrounding nutrition (McEvoy, Temple and

Woodside, 2012), food safety, food security (Helms, 2004),

environmentalism (Leitzmann, 2003), and the philosophy of

32

consumption. We can expand on what is debated within the literature

to how vegetarianism can be coupled with ‘theoretical arguments’

towards a consideration of the cultural politics of meat. The main

driving force behind the power of vegetarianism as opposed to say -

Organic, is the fact that although vegetarian philosophy has been

integrated in business circles to sell food to ‘conscious’

consumers, it’s rhetoric has yet to be restricted to certain ‘close-

ended definitions’, for example - branding legislation (Hahn and

Bruner, 2013: 45 – 47). This means that as vegetarianism can

encapsulate many legitimising paradigms to support itself as a

social movement, however, what remains against this argument is the

lingering moral rhetoric of ‘Western’ religions (that animals eat

animals – so can we as humans) which some argue against, suggesting

that nature is amoral; arguing for a secular approach (Soddard,

2014).

If we focus upon the cultural politics of meat, and accept the small

nuances of the above arguments, it can be suggested that as

described (Torres, 2007) political-economic forces have to date,

managed to ensure consumers are eating meat due to the economic

viability of animals; but is this the central issue when it comes to

reaffirming meat as ‘the dominant food’? As Adams (1990: 49)

suggests in The Sexual Politics of Meat, meat eating is reaffirmed by means

of mainstream patriarchal values and subtle marketing agenda, these

33

acts force meat eating to be an act of consumption which entails

‘what is politically right’, ‘what it means to be a man; a provider,

strong and supportive’ and ultimately, what it means to be an

omnivore. This cultural-political association does much not only to

ensure vegetarianism maintains its public perception as a ‘minority

culture’, but one which is strictly placed within a collectively

‘weak’ feminine identity. Similarly, biblical examples have

classically reaffirmed this subordination of women through meat, for

example through Leviticus 6 women are not permitted to eat the holy

meat prepared by the priests of Aaron; they are perpetuated below

god and man alike (Stanton, 2002), this essentially ideologically

places women only slightly higher than animals.

Aside from constructing self-identity, meat also has great sway in

the cultural politics of the collective; one contemporary example

was identified in the year 2013 which saw horsemeat being contained

within frozen beef products supplied by supermarkets from mainland

Europe to the United Kingdom and Ireland (Quinn, 2013). It was

through such headlines that much revulsion against horse meat was

accredited to the media frenzy which perpetrated how horsemeat was a

taboo, it was seemingly only a secondary consideration that it was a

product containing a foreign body (‘other meat’) that was at fault;

this is something which highlights the crude totenism and

inconsistency of consumption which arises through the celebration of

34

animals as pets. To this point, Herzog (2011) highlights that the

illogical nature of animals celebrated for their utilitarian value

further reflects humanities’ confused ideology over animals, yet he

also suggests a kind of value projection may exist in that pet

animals provide a structuring of our day with regards to feeding,

nursing and leisure activities. It is not conclusive, but this may

certainly be the case with animals such as horses that have a long

tradition as pets, workers and cultural idioms within Britain. This

‘anthrozoological’ approach suggests that ‘anthropocentrism’,

legitimised by social convention, religion and science, which has

central place within producing the cultural and orthodox politics of

meat. It is through these inconsistencies that meat industries take

advantage of embedded meat cuisines especially when appearing to

provide the consumer with ‘the ideal diet’, but similarly, meat

consumption is still often the means of pricing factors rather than

culture; the United States now consumes more chicken as of January

2012 partly due to beef prices rising to $5.02, up from $3.32 per

pound in 2002 (Earth Policy Institute, 2012).

To conclude, taking a ‘worldview’ approach to understanding the

cultural politics of meat moves beyond traditional

superstructure/base or structural-functional arguments, it takes the

‘power flow’ observations of Foucault’s (1965) notion of discourse

(in this case - hegemonic consumption) and applies it to a relevant

35

homogenous perspective. This can be thought of in the same way that

West (2013) relates the ecological principles of bacteria cultures

within cheese (“thinking like a cheese”), essentially we need to

“think like humans” in the same way that our dietary preferences

should reflect the ecological relationship ‘that we would have’

without the standardised production of meat and its affiliation with

‘The Ideal Diet’.

3. Methodology and Ethics

As mentioned in the context section, the type of the discussion of

which I intend to investigate for a ‘thick description’ (in this

case online analysis) (Geertz, 1973: 3) negates that geographical

location, and time concerns are non-critical to the nature of what

can be known by this methodology. This is to say that the form of

ontological investigation within this study’s aim seeks to

36

understand the paradigmatic nature of online atheist-vegetarian

communities, their choice of language, discussion and practice which

then can be used in a transcendent consideration of atheist-

vegetarianism as worldviews. The conception of ‘how we can know’

relates primarily to how atheists/vegetarians have come to be

defined, thus this is in part related to how internet forum sites

have facilitated these terms into defining identity markers for

community groups. McAlexander, Schouten and Koenig (2002: 856) as

they understand online forums in a product marketing context (as a

manifestation of ‘community’, ‘flow experiences’, and an area for

‘image management’), highlight some interesting thoughts of how

meta-level discussion centres and organises an environment of

identities, agendas, and participation modes which shape the topic

under discussion. This is the central strength that undertaking an

online study can provide when the researcher is a ‘participant

observer’ and also wishes to see how community members create,

change and maintain their online identities. Thus, as online forums

are a reflection of what members wish to divulge or express around a

specific topic, this means that knowledge formation is a ritual

process wherein members raise an issue for discussion, and then

return full swing to a self-replicating ‘social schematic cycle’

(Ortner, 1990). This ‘cycle’ is vastly beneficial when the

ethnographer wishes to “stick to the point”, notice nuanced

37

differences between ‘stories’, or focus down on a specific topical

discussion, ‘what can be known’ is different from the ‘traditional

field site’ when face-to-face interaction is removed; focus is drawn

upon discourse/ the structuring of text (Webster and da Silva, 2013:

125).

This methodology is beneficial for a study which seeks to understand

discussions which centre on nominal fields such as

atheism/vegetarianism, this is why a different set of knowledge

creation occurs from that of analysing traditional anthropological

literature. The question of “Is there a link between atheist and vegetarianism?”

can now be construed as a rationale as to why this study does not

solely rely upon a polemic discussion of atheist/vegetarian

literature; it takes into account that performing ‘focussed

ethnography’ (Knoblauch, 2005) is reliant upon the nature of the

questions asked, and a sufficient consideration of the relevant literature

that form these questions. There is similarly a certain nuance of

doubt in the way that the literary debates of adopting vegetarianism

as an atheist could potentially be ‘fetishized’, or portrayed with

higher valuable against this ethnography when arriving at the

discussion section of this study; this due to the environments

‘function’ as an atheist media site. It is also that online forums

of this magnitude (population of site and participatory members) can

only defined within a semi-public sphere, (that of the site itself)

38

that is to say, one only has to list a few account details and can

find him/herself as a part of the community; it is this question

that makes it important for us to define the value of knowledge in

respect of the form of Weltanschauug.

As above, the main consideration with ‘online ethnography’ surfaces

within the assumptions of what can be gained from platforms such as

forums. Driscoll and Gregg (2010: 17) place this understanding best

when suggesting that it is how one thinks of online communities and

if they can immerse the researcher into a community of practice,

otherwise this appears as a series of anonymous responses which can

be meaningless if one does not provide the context of discussion

into a larger investigation (which this study does). I would go

further to suggest when arguing against the notion that online

ethnography is somehow a partial perspective and ‘not a true field

site’, that the structure of ‘what is a forum’ or chat room rests on

the very principles that space and time are irrelevant to

participation, and that autonomy is granted in the form of what one

wishes to divulge. Such vast ‘catch-all’ phrases such as atheism or

vegetarianism are a part and parcel to this understanding, one could

theoretically immerse oneself in an atheist or vegetarian society by

means of a physical local community, but this would distort the

nature of the worldview concept by other dominant cultural strata of

the country in question (in terms of atheism or vegetarianism is

39

applicable in a respective country) or the limitations on time due

to life commitments such as work or personal circumstances. In this

way online ethnography has great benefits to epistemology, as

discussions of philosophy, ethics and consumption can be observed

for their content, style and delivery, one can also observe the

discourse of the participant against the contextual rhetoric of the

‘thread’ and topic. These ideas are mirrored (Crichton and Kinash,

2003) by a rising literature on online ethnography which supports

textual based interaction as more reflexive in terms of response and

content between ‘participant’ and observer. This idea also suggests

that web forums (as holistic entities) have little influence or sway

over the delivery of a topic (as opposed to a physical context would

restrict certain conversations due to social convention), the topics

as a discussion platforms indeed have their own social conventions;

but these are not so strict as participation stretches globally.

There are of course, weaknesses to reaching participants online and

within the kinds of information which are reviewed here; the

physical context of practice (especially consumption) is not at all

an ‘observable’ act. But is this truly a disadvantage? If

participants facilitate [a]synchronic social platforms, discussions

- which involve overarching themes can still be ‘grounded’ within

the subjective assertions of the particular argument, and also the

over-arching principles of the ‘master group’ (in this case the

40

subjective and literary term of atheism). This is something

considered by (Preece, Abras and Maloney-Krichmar, 2004: 3) as ‘the

nature and terms of the online community’. As the atheist community

website I will be referring to (AtheistNexus.org) is an interest

based platform (as opposed to professional), there is a large

element of personal ‘life experience’, philosophy, news articles and

scientific discussion. These principles of analysing nominal themes

complement the worldview as a transcendent methodology, but this

does not provide is the picture of a structure or a materialist

rationale for the behaviour of the community which a ‘traditional’

form of ethnography would provide.

3.1 ‘The Field Site’

AtheistNexus.Org, regarded by itself as the largest gathering of

online atheists is particularly unique in the sense it harbours a

facet of activism and association with global political/secular

societies such as Atheist Alliance International. This makes the

community somewhat mediated by personal narratives, news articles

from English-speaking media, and activist organisations which are

chosen by the administration of the site, and less so by its

41

members. Topics can be raised by any registered member (one that

that has created a personal account and ‘profile’ page with name,

email address and has ticked the ‘I am a non-Theist’ box) making the

site semi-private to outsiders. One example of a topic which I

observed due to the similar vein of structuring to the questions

posed in my study, was entitled: ‘Why Atheists can’t be Republicans’. This

particular discussion centred on a discussion of a book entitled

Atheists can’t be Republicans by CJ Werleman, the photograph of the book

(adorned in the red, white and blue of the United States flag) was

used as the header for the thread alongside a paragraph which

discussed the main themes and ethos of the book. What follows this

initial setting is a turn-by-turn response by members to post

replies in response to the ‘main post’ or as a reply to one another,

this means that topics follow a chronological ‘flow’ which can offer

new points of approach to a topic; it does not offer a function

which allows users to rate how influential a response is. In this

particular case many responses were generally in favour of

suggesting that atheist identity does not specifically develop one

with an anti-republic agenda in relation to the heavy religious

ideals that are incorporated into political agenda. Similarly the

‘opposition’ retorted this suggestion stating that those who are

‘informed’ atheists (aware of the philosophical and political

nuances between the traditionally religious part of conservative US

42

politics and the ‘enlightened and rational’ reasoning of the left-

wing atheist) should easily find justification to be anti-

republican. What this form of delivery by participants presents

(albeit the outcomes generalised into two camps for this

methodological example), is that a ‘spectrum’ of opinion, approach

and discourse coupled with underpinnings of a topical context, can

reveal the kinds of multi-layered information that is complimentary

to the nature of how the ‘isms’ of vegetarianism and atheism are

thus spoken and utilised in that particular community. Topics by

theme however do not have to strictly adhere to an atheist focus;

they can indeed take the shape of day-to-day interests such as

hobbies.

The ‘method’ of ethnography in this study, as written above, is

focussed towards asking participants in the online community of

AtheistNexus.Org a specific topical question in order to draw

relevant responses and reflection. The question that was provided

was as follows, “Is there a link between atheism and Vegetarianism?”, although

this sentencing structure initially creates dichotomous divides with

regards to phrasing, words such as ‘link’, ‘atheism’ and

‘vegetarianism’ as separate entities provides a breaking of the

frame of the question so that open ended responses can be based

around these specific semantic fields. This framing (both in

question and topic) is important in the manner that it both keeps

43

users focussed towards responding with social schema (experiences,

observations, education, external influences) in order to give

justification to an opinion, but also attracts those who have vested

interest with the subject of enquiry. This method does not guarantee

one has to be atheist or vegetarian to enter into the discussion

(although one must ‘tick’ an atheist ‘disclaimer’ when joining the

site), but does aptly investigate a spectrum of participants’

discourse from those who would not be conversing without the

engagement of an asynchronous multi-national platform. These

phrasing concerns both reflect the nature of the literature of

atheism and vegetarianism as two self-evidential social fields, but

also as two themes trapped by the language in terms of ‘day-to-day’,

and academic representation. There were 199 views of the topic, and

27 replies (including my own) in respect that many of the other

popular topics reached between 500 – 1000 views and between 30 – 80

replies. This gives partial understanding that there was, or is,

little interest in my question of a perceived link between atheism

and vegetarianism from the ‘orthodox atheist’ community, but

similarly I discovered a group entitled Vegetarian/Vegan Atheists in

which there had been little activity over its 11 month existence.

This observation implies further benefits to the ‘light’ method of

creating one topical thread in respect of accessibility and

interest, furthermore this form of ethnography provides benefits to

44

the constraints on time as a form of assessment; this also provides

flexibility towards allotting a balance between literary review and

primary enquiry.

As above, the main ethical consideration for conducting the

ethnography resides in the informed consent of the participants,

this was achieved by notifying them of my intentions to use their

‘online data’, text and profile information, furthermore, they were

made aware of SOAS’s code of conduct and also agreed that by

participating in this thread they would be responding to my study

(see appendix – image 3). As mentioned in the methodology section,

one other concern with regards to protecting participants was how

their responses would be used and represented in the manner of

research and analysis. As stated in the introduction, one of the

main aims of this study is to represent the nature of atheism and

vegetarianism as worldviews which can benefit anthropological

enquiry, this means that through epistemology one comes to represent

and direct the face of ‘who and what’ is involved (Rabinow, 1984:

239). Concern may arise from this issue if a researcher wishes to

advocate what has been produced by the people under study and to

align oneself with a social cause, in the case of this study, that

is not a consideration or a goal; the subsequent ethnographic data

collected here will be for the specific purpose of value creation

from the concept of worldview, and is only a used as a development

45

in the nature of representing what are perceived as ‘minority

views’.

4. Ethnographic Discussion

To begin a discussion of the atheist/vegetarian ethnography, I

firstly begin by highlighting the reply I received towards the

framing of my question (is there a ‘link’ between

atheism/Vegetarianism) from ‘Jillian’ - Wilmington, NC. For

reference the full transcription can be viewed at:

46

http://www.atheistnexus.org/forum/topics/atheism-vegetarianism-what-

is-the-link-are-you-vegetarian-help?xg_source=activity.

“Even though I'm a vegetarian I don't see a strong link between atheism and vegetarianism. Even

though atheists reject the notion that humans are specially created, many arguments for eating

meat, if not most of the ones I've heard, are made using biology rather than religion.”

This reply supports my initial philosophical focus by Peter Singer

and his range of secular anti-utilitarian based philosophy (Singer,

1975) (of whom ‘Jillian’ Mentions) that without religion, Darwinism

would fill the void of anthropocentrism, to instil onto man that

humans are ‘level’ to animals. This was interestingly refuted in a

nuanced way by ‘Christine’ (a female from New York and also a

vegetarian) who suggested that there is something so ‘Republican’

and therefore (by her association) ‘Christian’ around meat-eating

and its “entitlement mentality”. Whilst by suggesting atheists are

free of the entitlement of the Christian/Republican community,

‘Christine’ also contemplates the preparation of vegetables as a

“thoughtful”, and value-ridden procedure in relation to cooking

different ingredients at different stages.

…“meat can just be slapped on a grill or in a pan, flip, and done.…Religion is one of those things that

requires almost zero thought- slap a label on yourself, and there you go- instant acceptance, social

network, respect, forgiveness- all for reciting words that the pastor dishes out”.

47

This certainly falls in line with the focus of Fitzgerald (2010) of

how normalised slaughter and meat eating has become, not just in

respect of mainstream morality and the awareness of the ‘meat

industry’s’ agenda, but in terms of the ‘effort’ or ‘deviance’ that

the act of vegetarianism requires translates into a political

lifestyle action. Christine also continues on to state:

“Atheists are more grounded in reality by nature, and can't absolve themselves of guilt by a mere

confession or expectation of forgiveness. They want to make real, positive, tangible changes during

their stay here on the planet”…”My husband is also an atheist, but eats loads of meat, and is a bit of a

republican but not horrifically so :-p” .

What begins to emerge here, is that contemporary atheism and

vegetarianism are both overlapping as social schema in respect that

they are in-part ‘interchangeable moral canvases’, ahistorical, and

‘open-ended’ in terms of Heidegger’s ‘return to nature’. The latter

quote from Christine is an interesting example of how atheism, and

respectively how vegetarianism can be used as identity constructs

between genders - but also how typically ‘one can trump the other’

as here, atheism typically appears to be the higher valued ideology.

What is even more interesting is how Christine identifies meat

eating and ‘Republicanism’ as harmful fundamental themes; but

partially accepts her husband’s political views with a ‘tongue in

cheek response’ denoting that this is what reflects, and highlights

the importance/dichotomy of her vegetarianism as her identity.

48

We must not forget that vegetarianism has its own stereotypical

socially embedded ‘history’ which has been utilised as a subordinate

female trait - but now could similarly be reversed to identify women

as morally and nutritionally ‘equal’; the former has been a common

praxis in the history of patriarchal meat centred societies (Adams,

1990: 35- 40). In this way, atheism is also facilitated as a kind of

‘liminal’ secular space (in the style of Edmund Leach) for the

‘moral neophyte’ as we see with Christine’s husband’s worldview as

an atheist-Republican. In the same way as Leach (Holden, 2001)

observes rebellions which enforce structural societies, here I argue

a similar point that atheists (although providing a rhetoric towards

a collective empathy) similarly ‘rebel’ against traditional

philosophical constructions of ‘good and evil’ to be “more grounded in

reality by nature”, but yet are similarly trapped by those same constructs

of discourse towards a nuanced appropriation of science (‘nature’ is

not defined here as an ecological principle, but exists without

dogma). Another example of this was provided by a view from ‘Čenek

Sekavec’ (a male in his late 20’s from Hutchinson, KS), as he used

an argument pertaining ‘the savagery of nature’, ‘the ability to

communicate’, and ‘humanity’s’ ‘artificial ethical standards’ as

justifiers for the consumption of animals. This appears to be in

conflict with the majority of atheist-vegetarian arguments involved

in this study for animals as sentient beings; but similarly this

49

does relate to previous discussions around the anthropocentric

nature of natural science.

“If we someday find the ability to communicate with animals a drastic re-evaluation would be

necessary, most notably that animals would become responsible for their actions... What this tells me

is that it is the higher brain functions that define when morality can apply. We judge this based on

communication. If you won't charge a cow with assault because it rams you then you can't claim it

has sapience. There is a rule of universality that must apply regarding morality”.

What can be noticed here is that Čenek’s opinion suggests that the

‘responsibility’ and ‘morality’ of being a sapient being rests on

the ability of a ‘higher brain function’ (communication in this

case). What this tells us is that although ‘speciesism’ or

materialistic conceptions of nature, pigeon-hole humans as ‘the

thinking ape’ (Byrne, 1995) as part of a grand ecology, they do not

necessarily include arguments which take into account the relativity

of the animal experience or specifically negate a lack of belief in

a god. This is why if we look at scientific works which seek to

synthesise knowledge of modern consumption habits (in relation to

the Palaeolithic and Neolithic diets) as does anthropology, we can

see for example how modern animal husbandry practises (which treat

animals as ‘cash’ or ‘meat cows’ by providing little exercise for

the livestock) maintain an abundance of saturated fats within meat;

this is due to the animal being unable to act out its yearly cycle

of shedding extra fatty tissue (Cordain et al, 2005: 345). This

50

process is in-part maintained by economic determinants such as the

amount and quality of silage eaten by animals (relative to cost)

(Dairygold, 2014).

Much of the same focus on cognitive mentality (although applied to

humans) was classically revealed by Evans-Pritchard with Witchcraft,

Oracles and Magic among the Azante (Middleton and Winter, 2009) and Levy-

Bruhl’s (1923) considerations of Primitive Mentality. Should the same

focus on cognitive relativity (and animal rights) be extended (Mika,

2006) to non- human animals in light of biological enquiry into

sensory experience? What makes this issue even more complicated is

how humans as ‘intelligent beings’ can value and perceive the

intelligence of non-human animals. What these observations provide

for us, if taken against the considerations that animals have been

long thought of as materialist/functional concepts in lieu of

agricultural societies, is that more interpretive and discursive

investigations need to emerge in the style of ‘Anthrozoology’

(Herzog, 2011) or for humans to be thought of as ecological

principles by their own existential nature. To observe how the

rhetoric of science, consumption and religion legitimise the

superiority of man over animal; should we ‘do away’ with the word

animal as scientific discourse entirely? Although non-human animals

share legitimate utilitarian relationships with humans (I count pets

in this way) it appears that ‘animals as things to think with’ (to

51

be thought of as part of a grand ecology), are not theoretical

constructs which can be detached from the conception of animals as

food, it appears that this is a deeper lying reasoning behind the

inability for animal rights to emerge as a self-evident field.

To a similar point regarding vegetarianism and atheism ‘self-

evidential’ world views, “Sentient Bipod” (a male in his 50’s from

Vancouver, WA) suggested that just like atheism, vegetarianism was a

kind of "second nature in itself" and indeed required some ‘thought’

about the nutritional value of his diet; but for him there was a

small ideological overlap between his atheism and vegetarianism:

“Eating well requires learning about nutrition regardless of vegetarian or omnivore. I think for me it

is second nature. I never think about what to eat instead of meat. It would be like asking an atheist,

what do they do instead of going to church? Most of us never think about that, either. “

This coincides with the considerations of how atheism and

vegetarianism can be ‘conscious-raising’ or ‘habit breaking’ (in

reference to Heidegger), and that nominally labelled ‘forms of

practice’ such as health or ethical based vegetarianism, break down

these terms as natural-holistic or representative principles. This

form of description is a ‘watering down’ or reduction of principle

by rhetoric, and the forms of which elude themselves to the social

sciences in particular; an earlier example of this was the changing

definitions of Organic from a social movement to a semiotic device

52

for food products. Once a term has ‘succeeded’ I.e. been adopted by

Heidegger’s “They” (industry etc.), it becomes an ‘authentic’

victory in the sense that the values have been mimetically adopted

and normalised. For vegetarianism this is an even greater

possibility as the term as a semantic field has a wider generalised

meaning to be ‘open-ended’ with regards to one’s own conception of

vegetarianism.

53

5. Conclusion

Through the nature of this dissertation which has reviewed a

discussion of the atheist-vegetarian literature, the concept of

Heidegger’s Weltanschauug, and in lieu of a “cross-context” approach to

“online ethnography”, I have shown how synthesising unfamiliar

philosophical concepts with the anthropology of vegetarianism can

highlight how those who define themselves as atheist-vegetarians

have been misrepresented as having ‘extreme minority views’. This

dissertation has taken a small step (with regards to time and word

constraints) in utilising the concept of ‘worldviews’ over the more

popular analytical trends which focus upon a neoliberal

superstructure (Guthman, 2008), or a ‘Focaultian’ style analysis of

agri-business power relationships (Tansey, 2002). Atheism and

vegetarianism have been shown as examples of permeable worldviews

which hold the power to transcend (temporally) the limited power of

market-based ethical food movements (Schultz, 2013) (Parkins and

Craig, 2011: 192) such as Organic, or furthermore (in relation to

54

speciesism) shown how ‘conscious thinking’ towards consumption can

highlight the anthropocentric/contradictory relationship over

animals in relation to our food chain (taboos). What can be learnt

from this investigation into how atheism-vegetarianism reflects ‘the

modern moral society’ is that even through atheist-vegetarian

worldviews, it is not always the conception of Speciesism or

Darwinism that is an overarching rationale for vegetarianism; nor so

is the atheist-vegetarian moral worldview explicitly strictly

informed by natural science. These worldviews can often be the

result of a mixed collection of emotional responses to the ending of

life (note Valeri’s Forest of Taboos (2000) mentioned earlier), the

separation from man from ‘nature’, or indeed the avocation of

animals as sapient beings through the extension of rights to

animals.

It is the hegemony of meat, identified through the ‘worldview’

(Innes, 2014) in which moral vegetarianism is beneficial, even as it

may be trapped by lingering religious anthropocentrism, gender

stereotypes (Adams, 1990), harmful nutritional paradigms, and

utilitarian attitudes to animals as commodities (which are in fact

essential to vegetarianism’s existence). In response to this

perspective of worldviews to complement the nature of

anthropological enquiry, it is interesting to perceive how the act

of meat consumption is depoliticised as ‘a normal diet’ as an ideal

55

omnivorous activity. Further beneficial study should focus upon how

the dichotomy of deviance with regards to ‘minority groups’ is both

essential to their success in social activism, but ultimately

creates stigmatism or resistance by what is perceived as ‘normal’.

56

6. References

Adams, C. 1990. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory,

London: The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

The Animal Studies Group. 2006. Killing Animals, Illinois: The Universityof Illinois.

Beardsworth, A, and Keil, T. 1992. ‘The Vegetarian option:

varieties, conversions, motives and careers’, The Sociological Review, (40),

2. pp 253 – 293.

Belasco, W. 2005. Food and The Counterculture a Story of Bread and Politics, in The

Cultural Politics of Food and Eating: a reader. Ed by James Watson

and Melisa Caldwell.

Bloch, M. 1999. ‘Commensality and Poisoning’, Social Research, (66), 1. pp133 – 149.

Brunn, H, and Whimster, S. 2012. Max Weber: Collected Methodological Writings.Oxon: Routledge.

57

Byrne, R. 1995. The Thinking Ape: Evolutionary Origins of Intelligence, New York:

Oxford University.

Cordain, L, Eaton, S, Sebastian, A, Mann, N, Lindeberg, S, Watkins,

B, O’Keefe, J and Brand-Miller, J .2005. ‘Origins and evolution of

the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century’, American

Society for Clinical Nutrition, 81, pp 341 – 54.

Cornwall, A. 2007. ‘Buzzwords and fuzzwords: deconstructing

development discourse’, Development in Practice, (17), 4- 5. pp 471 – 484.

Crichton, S and Kinash, S. 2003. ‘Virtual ethnogaphy: Interactive

Interviewing Online as Method’, Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology,

(29) 2.

Curtis, M. 2011. Vegetarian Etiquette, [Online] The Practical Vegetarian.

(Available at:

http://thepracticalvegetarian.com/vegetarianetiquette.html.

(Accessed 26th July 2014)

Dailygold. 2014. Cull Cows-Sell Now or Feed and Fatten?, [Online] Dairygold.

Available at: http://www.agritrading.ie/Cull-CowsSell-Now-or-Feed-

and-Fatten. (Accessed: 17th July 2014)

58

Dawkins, R. 2006. The God Delusion, London: Transworld Publishers.

DeLeeuw, J, Galen, L, Aebersold, C and Stanton, V. 2007. ‘Support

for Animal Rights as a Function of Belief in Evolution, Religious

Fundamentalism, and Religious Denomination’, Society and Animals, 15. pp

353 – 363.

Dilley, R. 2002. ‘The Problem of Context in Social and Cultural

Anthropology’, Lanugage and Communication, (22). pp 437 456.

Driscoll, C and Gregg, M. 2010. ‘My profile: The ethics of virtual

ethnography’, Emotion, Space and Society. 3. pp 15 – 20.

Earth Policy Institute, 2012. Peak Meat U.S meat consumption by Person by

Type, [Online] Available at:

http://www.earth-policy.org/data_highlights/2012/highlights25.

(Accessed 25th July 2014).

European Vegetarian Union. 2009. ‘Vegetarian Solutions for a

Sustainable Environment’, Journal of the European Vegetarian Union, 2. pp 1 -

16

59

Fitzgerald, A. 2010. ‘A Social History of the Slaughterhouse: From

Inception to Contemporary Implications’, Human Ecology Review, (17), 1. pp

58 – 69.

Foucault, M. 1965. Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of

Reason, New York: Random House Inc.

Hahn, L and Bruner, M. 2013. ‘Politics on Your Plate: Building and

Burning Bridges across Organic, Vegetarian, and Vegan Discourse’, in

The Rhetoric of Food: Discourse, Materiality, and Power. Ed by Frye,

J and Bruner, M. Oxon: Routledge.

Geertz, C. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays by Clifford Geertz, New

York: Basic Books.

Guthman, J. 2008. ‘Neoliberalism and the making of food politics in

California, Rethinking Economy, 39, (3). pp 1171 – 1183.

Harris, M. 1985. Good to Eat: Riddles of Food and Culture, Illinois: Waveland

Press Inc.

Harris, S. 2004. The End of Faith, Religion, Terror, and The Future of Reason,

London: The Free Press.

60

Helms, M. 2004. ‘Food sustainability, food security and the

environment’, British Food Journal, (106), 5, pp 380 – 387.

Herzog, H. 2011. Some we love, some we hate, some we eat: Why it’s so hard to think

straight about animals, New York: Harper Collins.

Hitchens, C. 2007. God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, New York:

Hachette Book Group.

Holden, L. 2001. Taboos: Structure and Rebellion, From monograph series 41.

London: The Institute for Cultural Research.

Humphrey, M. 2013. ‘Rethinking Migration and Diversity in

Australia’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, (34) 2. pp 178 – 295.

Hyman, G. 2010. A Short History of Atheism, London: I.B Tauris & Co Ltd.

Innes, E. 2014. Vegetarians are 'less healthy' and have a poorer

quality of life than meat-eaters, [Online] Daily Mail. Available at:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2596012/Vegetarians-

healthy-poorer-quality-life-meat-eaters.html.

(Accessed: 17th June 2014)

61

Jabs, J, Devine, C and Sobal, J. 1998. ‘Model of the Process of

Adopting Vegetarian Diets: Health Vegetarians and Ethical

Vegetarians’, Journal of Nutrition Education, 30. pp 196 – 202.

Jabs, J, Devine, C and Sobal, J. 2000. ‘Managing vegetarianism,

Identites Norms and Interactions. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 39, pp 375 –

394.

Jackson, M. 2013. Lifeworlds: Essays In Existential Anthropology, Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Knight, C. 2011. 'If You're Not Allowed to Have Rice, What Do You

Have with Your Curry?': Nostalgia and Tradition in Low-Carbohydrate

Diet Discourse and Practice’ Sociological Research Online, (16), 8.

Knoblauch, H. 2005. ‘Focussed Ethnography’, Forum: Qualitative Social

Research. (6), 3. Art 44.

Largen, K. 2009. ‘A Christian Rationale for Vegetarianism’, Dialog, 42,

(2). pp 147 – 157.

Leitzmann, C. 2003. ‘Nutrition Ecology: The Contribution of