The Political Economy of Statebuilding: Rents, Taxes, and Perpetual Dependency,

Natural resource rents and elite bargains in Africa: Exploring avenues for future research

Transcript of Natural resource rents and elite bargains in Africa: Exploring avenues for future research

This article was downloaded by: [University of Cape Town Libraries]On: 28 August 2014, At: 01:35Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

South African Journal of InternationalAffairsPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsaj20

Natural resource rents and elitebargains in Africa: Exploring avenuesfor future researchRoss Harveya

a South African Institute of International Affairs, Johannesburgand University of Cape Town, South AfricaPublished online: 30 Jul 2014.

To cite this article: Ross Harvey (2014): Natural resource rents and elite bargains in Africa:Exploring avenues for future research, South African Journal of International Affairs, DOI:10.1080/10220461.2014.941001

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2014.941001

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Natural resource rents and elite bargains in Africa: Exploring avenuesfor future research

Ross Harvey*

South African Institute of International Affairs, Johannesburg and University of Cape Town,South Africa

This article explores the recent debate over the quality of Africa’s growth episode ofthe past decade, specifically insofar as it pertains to the pitfalls of commodity-dependent growth and the hypothesised ‘resource curse’. In addition, the articlefocuses on why political and economic institutions are important, and why they areindicators for the likely development impacts of Africa’s evident mineral andhydrocarbon wealth. Third, it suggests a useful theoretical framework for understand-ing these indicators, especially with regard to the differing constraints under whichforeign investors operate and interact with host countries. Developing on the latterpoints, the article looks at the nature of Chinese foreign investment in Africa’sextractive industries. Finally, the article suggests an agenda for future research thatcould better inform development policy for the purpose of promoting high-qualitygrowth in Africa.

Keywords: Africa; quality growth; natural resource curse; new institutional econom-ics; China in Africa; elite bargain

Introduction

On 11 May 2000, The Economist ran a cover of Africa depicted as the ‘HopelessContinent’.1 Over a decade later, the newspaper publicly regretted the label it hadunceremoniously dumped on the continent. In belated penance, on 28 February 2013, itscover was headlined ‘Africa Rising’.2 In the space of a decade, analytical sentimentregarding Africa’s development prospects had shifted. Shortly after The Economistreleased its special report, Martinez and Mlachila of the International Monetary Fund(IMF) released a paper asserting that ‘the quality of growth in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)has unambiguously improved, although progress in social indicators has been uneven’.3

That report does note, however, that there is still considerable debate as to whether therecent episode of high growth is inclusive and sustainable; according to Acemoglu andRobinson, inclusivity is important because broad-based political institutions are aprerequisite for building the kind of economic institutions from which growth cantranslate into sustainable development.4

It is therefore important to ascertain the extent to which SSA’s continued commodity-concentrated growth from a low base is likely to encourage inclusivity in politicalinstitutions. Part of the debate noted above centres around the problem of commodity-concentrated growth. A number of mineral-dependent countries were, for instance,

*Email: [email protected]

South African Journal of International Affairs, 2014http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2014.941001

© 2014 The South African Institute of International Affairs

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

excluded from the IMF study, most likely skewing the results considerably. Martinez andMlachila readily admit that statistical and methodological difficulties plague the results.Most importantly, ‘deeper analysis is needed to dig into the interrelations between variousaspects of growth and inter-linkages with socially desirable outcomes’.5 Mineral andhydrocarbon abundance would seem to be a favourable natural endowment fordevelopment purposes. However, in the context of weak political and economicinstitutions, these endowments appear to encourage unproductive rent-seeking,6 resultingin unintended development outcomes. Several theories exist to explain this observation.

In order for minerals and hydrocarbons to be useful for development, they must beextracted and sold. In African and other non-Organisation for Economic Co-operationand Development (OECD) economies, this invariably this requires foreign investment, ascapital availability in African and other non-OECD economies is insufficient. Theconstraints under which these foreign players operate and interact with domestic elites isthus important for understanding the likely impact of resource-extraction on host-countryinstitutions in Africa. At the same time, the nature and structure of demand for mineralsand hydrocarbons is shifting rapidly. The ‘shale gas’ revolution in the US7 and thatcountry’s impending energy self-sufficiency are likely to result in changes to thecomposition of global hydrocarbon demand. Demand levels appear likely to remainsteady, but shift towards the East, with China being the most important player.8 Despitethe shifting structure of China’s economy away from export-led manufacturing towardsinternal consumption, the demand for fossil fuels and minerals is likely to remain strongat least over the next decade and beyond, especially as its energy-intensive growthcontinues at comparatively high rates. China’s twelfth five-year plan envisages thecompletion of industrialisation by 2020, which may indicate attenuation of demand forminerals such as iron-ore and copper thereafter. However, continued growth of theChinese middle class suggests that demand for minerals such as bauxite (a crucial smart-phone ingredient) will continue to grow substantially beyond 2020, again indicatingchanges in the composition of global mineral demand, but not necessarily in overalllevels.

This article begins by examining the debate to which Martinez and Mlachila refer.The major objections to their position can be traced to the literature pertaining to thehypothesised ‘resource curse’,9 which is discussed at length. Second, the article focuseson why political and economic institutions are important, and why they are indicators forthe likely development impacts of Africa’s evident mineral and hydrocarbon wealth.Third, it suggests a useful theoretical framework for understanding these indicators,especially with regard to the differing constraints under which foreign investors operateand interact with host countries. In this vein, the article looks at the nature of Chineseforeign investment in Africa’s extractive industries, and discusses why this is specificallyimportant, drawing on some of the relevant ‘China in Africa’ literature to do so. Finally,the article suggests an agenda for future research that could better inform developmentpolicy for the purpose of promoting high-quality growth in Africa.

Quality growth and resource dependence

Between 1995 and 2011 real gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 4.3% acrossSSA, real per capita GDP growth averaged 1.83% and final household consumptionexpenditure per capita growth averaged 1.59%.10 While this growth episode is formidableon these counts, it remains unclear whether it is of a sufficient quality to be translated intodevelopment benefit. Martinez and Mlachila define quality growth as ‘strong, stable,

2 Ross Harvey

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

sustainable, increases in productivity [that] lead to socially desirable outcomes likeimproved standards of living, especially in the reduction of poverty’.11 They argue thatcountries that have experienced high-growth episodes achieved macroeconomic stability,pursued sound economic policies and ‘reinforced their institutions’.12 Their four mainfindings are as follows: first, the 1995–2011 high-growth episode in SSA is characterisedby a strong real GDP per capita growth rate and is geographically broad-based. Second,the growth has been less volatile than in the prior 15-year period. On the first finding,geographic distribution of wealth creation does not necessarily tell the reader anythinguseful about the distribution of income across classes, which would be a more interestingfinding. Regarding the second finding, while lower growth volatility is evident onaverage, the volatility in mineral-wealthy countries has been more pronounced whencompared with non-mineral-wealthy countries. Third, total factor productivity hasimproved. There does appear to be a relative consensus that this bodes well for sustainedgrowth. Finally, they find an overall shift toward more export-orientated growth,accompanied by increases in gross investment.

Social indicators are included in Martinez and Mlachila’s definition of quality growth.However, their conclusion that growth quality has improved ‘unambiguously’ iscontradicted by their admission that improvement in social indicators has been unevenand is generally higher in low-income and fragile countries, albeit from a low level.Indeed, there is little to suggest that these improvements are a function of growth per se.They could be attributable to exogenous improvements in, and availability of, globalhealth technology, for instance. They admit that the quality of data itself is poor and ‘thepaper does not analyse in detail the interrelation between growth and various socialindicators’.13 There are significant improvements in indicators such as child mortality andsecondary school enrolment levels, but life expectancy at birth and primary schoolenrolment remains relatively unchanged.

In a contribution to the debate that is contrary to Martinez and Mlachila’s conclusions,World Bank authors Arbache and Page contend that:

[G]overnance indicators have declined since 1996 for the region as a whole and forthe resource-rich economies compared with non-resource-rich economies during growthaccelerations … suggesting the possibility that in mineral-rich economies booms areaccompanied by adverse governance outcomes that may eventually reduce furthergrowth. … The concentration of good economic times in the resource-rich economies raisesthe possibility that growth is vulnerable to declines in commodity prices and to the naturalresource ‘curse’.14

They find that Africa’s growth accelerations have generally not been accompanied byimprovements in variables often correlated with long-run growth. Resource-richeconomies had a significantly higher frequency of growth accelerations than non-resource-rich economies. Most importantly, they conclude that the evidence does notsupport the view that policy and governance improvements were associated with post-1995 accelerations. Africa’s growth recovery therefore remains fragile.15

One of the overarching concerns of extractive-industry-based growth is thatcommodities are subject to demand fluctuations. Consequently, producers in politicallyvolatile contexts may have an incentive to extract the resource inefficiently. Unstable orvolatile political contexts increase uncertainty for investors pertaining to security oftenure (among other things) and therefore tend to result in steeper discount functions formining companies, increasing the rates of extraction and leaving a higher proportion of

South African Journal of International Affairs 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

the ore body untapped, reducing the life of the mine and its associated employmentpotential. This is exacerbated by the volatility of commodity prices over time.

Moreover, resource riches raise the value of being in power (in the context of accessto the public purse or being able to pursue conflicts of interest, or a combination, on thepart of politicians), and induce politicians to expand their patronage networks by bloatingthe public service (to improve re-election probability), thus creating inefficiency andoverall loss of national income.16 Windfall natural resource wealth may thus encouragedirectly unproductive rent-seeking among elites, with a resultant negative effect onpolitical institutions, such as creating incentives to undermine transparency andaccountability. Further, the extractive process itself typically leads to negative external-ities or spillover costs.17 Examples of these may be the social cost of polluting a rivernear a coalmine or destroying irreplaceable water supplies through hydraulic fracturing(for gas extraction). These costs occur outside of formally traded sectors and producesocial inefficiency. Market signals therefore convey imperfect information, a kind ofmarket failure. Less powerful communities often disproportionately bear the impact ofthese externalities, while political and corporate elites reap the benefits of offloadingthem.18

The ‘resource-curse’ literature suggests a number of channels through which highlevels of natural resource wealth could have an adverse impact on development. Eachpotential ‘channel’ can be operationalised as a measurable explanatory variable whoseimpact researchers try to isolate in order to determine possible causal relationships. VanDer Ploeg examines no less than eight in his 2011 review of the literature,19 but a relativeconsensus is emerging that institutions are preeminent among them. Sarr and Swansonprovide an instructive contribution in this respect by employing a ‘dictator model’ thatprovides the link between the political economy literature that explores corruption, andthe resource curse literature that examines how macro-economic outcomes are linked toresource endowments and institutions. They argue that corruption is primarily aneconomic phenomenon, and that it should be understood as a crucial component inexplaining poor governance indicators associated with resource wealth:

Poor institutional quality is one of the main drivers of economic [under]development, and ofresource-rich economies in particular. Resource-rich countries are also particularly prone tocorruption. In our model, a dictator makes a choice between staying and looting. Theincentives for staying result from the opportunity to take advantage of the country’s potentialproductivity while remaining in power. Looting involves the immediate translation ofpolitical control into maximum appropriable gain. It is the essence of the sort of corruptionthat renders resource-rich countries subject to the curse … The problem with such politicalinstability and looting is that it is dynamically attractive. Once a choice to loot isimplemented, the incentives to loot are enhanced for every succeeding administration. Thisis a consequence of the autocrat’s ability to commit all of the state’s resources – during thelength of its tenure – and the fact that this commitment will outlive the autocrat’s tenure. Thismeans that succeeding administrations start from an initial condition that is more indebted,and hence more prone to looting than previous ones.20

The trajectory toward a consensus around the importance of institutions follows in thetradition of work begun by Douglass North in the 1970s, referred to as the NewInstitutional Economics.21

4 Ross Harvey

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

The debate: are political and economic institutions important to economic growth?

In 2001, Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (AJR) attempted to empirically establish thefundamental causes of large cross-country differences in income per capita. Although onone level it was self-evident that countries with better institutions perform bettereconomically owing to higher levels of investment in human and physical capital,supporting statistical estimates were lacking. Particularly, it was possible to argue reversecausality – wealthier countries could simply afford better institutions.22 The methodolo-gical difficulty was to find a source of exogenous variation in institutions, without whichcausation could not reliably be established. Using ‘mortality rates expected by the firstEuropean settlers in the colonies as an instrument for current institutions in thesecountries’,23 they found that ‘colonies where Europeans faced higher mortality rates aretoday substantially poorer than colonies that were healthy for Europeans’.24 Mortalityrates were employed as an instrumental variable to establish exogenous variation ininstitutional formation. Lower mortality rates led to higher settlement rates, which led tobetter institutions, exemplified primarily in lower risk of property expropriation. Theyfound a strong correlation between the quality of early institutions and institutions today,suggesting a high degree of persistence. ‘Mortality rates faced by the settlers more than100 years ago explain over 25 percent of the variation in current institutions’.25

The historical record substantiates the empirical work by AJR. Settlers in places withlower mortality (such as the US, Australia and New Zealand) adopted institutions thatprotected property rights, enforced the rule of law and encouraged investment. Settlers inplaces with higher mortality, such as Congo or Ghana, established ‘extractive’institutions, ‘with the intention of transferring resources rapidly to the metropole. Theseinstitutions were detrimental to investment and economic progress’.26 AJR might alsohave mentioned that regions with higher mortality rates were also endowed withextensive mineral and hydrocarbon resources. Discount rates27 tended to be higher forelites in these regions, hence the increased likelihood of extractive institutions. Incontrast, colonising elites incentivised to settle in places with lower mortality were morelikely to invest in establishing institutions that enhanced long-run economic performance.Rates of extraction in the extractive industries would be likely to be more efficient inthose contexts, enabling the use of that wealth to diversify economies.

Explaining the formation and persistence of extractive institutions in Africa isparticularly important for understanding the apparent negative correlation betweenresource wealth and governance performance on the continent today.

AJR hypothesise three mechanisms by which extractive institutions persist. First,establishing institutions that limit government power and respect property rights is costly.Acemoglu and Verdier show that:

[S]ince preventing corruption and enforcing property rights is costly, the socially optimalresource allocation often involves less than full enforcement of property rights, and possiblysome corruption … Too much corruption would destroy property rights and investmentincentives, but preventing all corruption may be excessively costly.28

AJR suggest that ‘If these costs have been sunk by the colonial powers, then it may notpay the elites at independence to switch from this set of institutions to extractiveinstitutions’.29 In contrast, establishing or maintaining extractive institutions requires fewcosts for elites. New elites, inheriting these institutions at independence (from 1957onwards in Africa), may not be willing to incur the cost of establishing better institutionsand ‘may instead prefer to exploit the existing extractive institutions for their own

South African Journal of International Affairs 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

benefits’.30 This appears to be the case especially when natural resource wealth isavailable. Mineral and hydrocarbon wealth in particular is finite, and the pre-existence ofextractive institutions may simply aid elite rent-acquisition from those resources to eithershore up wealth for retirement (in exile) or to improve the probability of staying in powerthrough either elections or repression. Second, small elite groups may have a greaterincentive than large elite groups to employ an extractive strategy, as the rent returns percapita are higher in a small group. Third, if investments have been made in physical andhuman capital, elites are more likely to support institutions that ensure economic returns.Unfortunately the converse is also true.

In a critique of AJR, Glaeser, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer criticised theuse of settler mortality as an instrumental variable, arguing that ‘at least part of whatsettler mortality captures is the modern disease environment’.31 They express concernthat the instrument may be correlated with human capital, reflecting the knowledge thatsettlers brought with them to the colonies, rather than constraints on the executive (apolitical institution) per se. ‘The effects of colonial settlement work through manychannels, and the instruments used in the literature do not tell us which channel matters… The instrumental variable approach does not tell us what causes growth’.32 They donot doubt that institutions are important, but argue that the limitation of econometrictechniques does not allow AJR the conceptual or empirical means required to show thatpolitical institutions necessarily precede and fuel human capital formation. Concurringwith Djankov and others,33 Glaeser et al. argue that ‘the existing research does not showthat political institutions rather than human capital have a causal effect on economicgrowth. Indeed, much evidence points to the primacy of human capital for both growthand democratisation’.34 Essentially, institutional choices are determined by the levels ofhuman and social capital available to a community at a particular point in time. Lowersettler mortality may simply indicate more available levels of these types of capital,leading to better institutional choices. ‘Our results do not support the view that, from theperspective of security of property and economic development, democratization andconstraints on government must come first’.35

In the same edition of the Journal of Economic Growth, however, Rodrik,Subramanian and Trebbi ‘find that the quality of institutions trumps everything else’36

in determining whether geography, trade integration or institutions can best account forcross-country variation in national income levels. Institutional quality has a positive effecton trade integration, and geography exerts a significant effect on the quality ofinstitutions, which corresponds with the AJR findings. By controlling for tradeintegration, something absent from the original AJR model, their findings strengthenthe AJR conclusion, but with some important qualifications. Their primary criticism ofthe 2001 AJR paper is that it does not sufficiently differentiate between ‘using aninstrument to identify an exogenous source of variation in the independent variable ofinterest and laying out a full theory of cause and effect’.37 They are however convincedthat the settler mortality instrument is valid as a means of identifying exogenous variationin institutions, and not (as Easterly and Levine would have it) as a geographicaldeterminant of institutions. Emphasising this distinction, Rodrik et al. caution againsteither a colonial view of development or a geography-based theory of development. By2012, in their treatise Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu and Robinson clearly favoured thecolonial view, especially as it pertains to explaining Africa’s development:

[T]he structures of colonial rule left Africa with a more complex and pernicious institutionallegacy in the 1960s than at the start of the colonial period. The development of the political

6 Ross Harvey

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

and economic institutions in many African colonies meant that rather than creating a criticaljuncture for improvements in their institutions, independence created an opening forunscrupulous leaders to take over and intensify the extraction that European colonialistspresided over. The political incentives these structures created led to a style of politics thatreproduced the historical patterns of insecure and inefficient property rights under states withstrong absolutist tendencies but nonetheless lacking any centralized authority over theirterritories.38

The relationship between institutions, human capital and development

In early 2014, Acemoglu, Gallego and Robinson (AGR) revisited the relationshipbetween institutions, human capital and development. They addressed the 2004 debateand the Glaeser critique in particular, which accused AJR of ‘putting the institutional cartbefore the human capital horse’.39 First, AGR provide a historical survey of humancapital endowments taken to the American colonies, and show that ‘Europeans appear tohave brought more human capital per person to their extractive colonies than their settlercolonies with inclusive institutions’.40 Higher rates of education in the US today, forinstance, appear to be a function of early institutions that incentivised mass schooling,institutions which were never established in Peru or Mexico. This refutes the view thatlower mortality rates are inadvertently capturing higher levels of human capital.

The second major finding is that human capital, proxied by average years ofschooling (exogenous if regressed by itself) or instrumented by Protestant missionaryactivity in the early 20th century (missionaries established schools to encourage reading ofthe Bible), appears to be a significant determinant of long-run development (returns in therange of 25–35% of one more year of schooling to GDP per capita today). However, thiscalls for a direct comparison with studies that identify the contribution of one more yearof individual schooling on individual earnings, typically estimated in the range of 6–10%return. ‘In theory and reality, these two numbers should be more tightly linked’.41 Thediscrepancy could be explained if there were evidence for large human capitalexternalities, but AGR show that the existing evidence does not support this view.Regarding Glaeser et al.’s critique specifically,

[T]here is a prima facie case for a severe omitted variable bias in [their] regressions … Eitherhuman capital is proxying for something else or it is capturing some of the effects ofinstitutions … Once we control for the historical determinants of institutions and humancapital, or simultaneously treat both variables as endogenous, the estimates of the effect ofhuman capital on long-run development decline significantly … In contrast, the impact ofinstitutions on long-run development remains qualitatively and quantitatively robust towhether human capital is included in the regression (and treated endogenously) or historicaldeterminants of education are directly controlled for.42

AGR therefore confirm the original AJR finding that institutions are the fundamentalcause of long-run development, working through human capital in addition to total factorproductivity. Future research, they suggest, should carefully examine the interactionbetween institutions and human capital formation.

Recent work by Bates, Block, Fayad and Hoeffler43 also directly confronts theGlaeser et al. position, which ‘does not support the view that from the perspective ofsecurity of property and economic development, democratization and constraints ongovernment must come first’.44 Bates et al. do not argue that it must come first, but showempirically that, in Africa, political reform in the direction of democracy precedes (and

South African Journal of International Affairs 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

causes) increases in GDP per capita. Changes in Africa’s political institutions in the late20th century provided a natural experiment by which to test institutional arguments asposited by the likes of AJR and Douglass North. ‘At the macro level, political reform is(Granger)45 causally related to economic growth, and at the micro level, positively andsignificantly related to TFP [total factor productivity] growth in agriculture?’46 The latteris particularly significant, as it shows how reforms in the direction of democracy changedpolitical incentives. Farmers became the electoral majority, thus pressurising politicians tochoose policies that favoured agricultural producers over consumers. Previously, urban(elite) consumers had been favoured at the expense of rural producers. Incentive changesprovoked policy changes, supporting the general view of New Institutional Economicsthat ‘the structure of political institutions influences the performance of economies’.47

With regard to the impact of natural resource endowments specifically on economicperformance, two influential papers48 also contest the idea that geography has someinnate effect on countries’ economic growth trajectories. Rather, institutions play thedetermining role: if institutions promote rent capture by a narrow elite, natural resourcewealth tends to drive aggregate income down; if they are ‘producer-friendly’, they arelikely to raise aggregate income. These effects are also amplified by the quality of theinstitutions at the time of discovering resource wealth. The arguments that initialinstitutional quality is decisive in explaining development outcomes are substantivelydifferent from Sachs and Warner’s original contribution in 1995,49 which found that asubstantial natural resource endowment could be suboptimal for growth prospects aftercontrolling for trade policies and initial income levels. This work argued explicitly thatthe effect of institutional quality was insignificant.

Luong and Weinthal,50 along with Quinn and Conway,51 however, proffer thatownership52 of the resources is a crucial determinant of their likely developmentoutcome. The latter find that majority state ownership of the mining industry in Africaresults in inward-oriented economic policies leading to lower economic growth and fewerpolitical and civil rights.

Robinson, Torvik and Verdier53 complement their ‘rational actor’ explanations with‘institutionalist’ ones insofar as the ‘overall impact of resource booms on the economydepends critically on institutions – [that promote accountability and thus mitigateperverse political incentives that may otherwise persist] – since these determine the extentto which political incentives map into policy outcomes’.54 Leong and Mohaddes continuein this tradition with a paper that studies the impact of resource rents and their volatilityon economic growth under varying institutional quality. They do find evidence for a cursebut attribute the cause to volatility, not abundance. Tellingly, ‘higher institutional qualitycan help offset some of the negative volatility effects of resource rents. Therefore,resource abundance can be a blessing provided that growth and welfare enhancingpolicies and institutions are adopted’.55 They advocate the use of sovereign wealth andstabilisation funds to smooth the reasonably foreseeable volatility that arises from rentvolatility. These funds can also be used to ‘increase the complementarities of physical andhuman capital, such as improving the judicial system, property rights, and human capital.This would increase the returns on investment with positive effects on capitalaccumulation and growth’.56

A silver bullet?

In light of the above, a future research agenda should include studies on how naturalresource wealth could be harnessed to build better institutions and produce stronger

8 Ross Harvey

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

development outcomes, especially when the existing political settlements are charac-terised by extractive institutions. In a narrower sense, as a starting point, scholars shouldattempt to understand how foreign investment (especially from players like China), inmineral and petroleum sectors specifically, is likely to affect the dynamics of politicalinstitutions in host countries where such resources are abundant. Absent this understand-ing, development policy recommendations are unlikely to gain traction.

Traditionally, the consensus view among economists has been that public policyshould be designed as an attempt to reduce or remove market failure and policydistortions. However, as Acemoglu and Robinson note in a 2013 paper, existing politicalsettlements ‘may crucially depend on the presence of market failure. Economic reformsimplemented without an understanding of their political consequences, rather thanpromoting economic efficiency, can significantly reduce it’.57 Therefore, economic policyadvice should explicitly factor in the impact the consequent distribution of rents will haveon future political equilibria. If rents are likely to accumulate in a way that simplystrengthens already dominant groups, for instance, the advice should be reconsidered.This work is particularly important for understanding the political consequences ofmineral rents. It compares Australia with Sierra Leone and shows how the initialinstitutions chosen to govern mining had a large effect on the nature of investors itattracted, which had subsequent effects not only on the structure of the industry but alsoon the dynamics of political bargains:

That the political consequences of the economic organisation of mineral extraction may bemore important than their direct economic consequences is illustrated by the contrast of theAustralian and Sierra Leonean histories. The Australian case suggests that when a largenumber of independent, small-scale miners are doing the extraction and realise their rentsmay be dissipated, this encourages their political organisation as a group, ultimately creatinga more balanced political landscape and contributing to the development of democraticpolitics. On the other side, Sierra Leone’s experience showcases how the prevalence of largeand very profitable mining interests often has negative and non-democratic implications forthe distribution of political power.58

Resource rents tend to become available through two channels: from the direct sale ofcommodities or through corporate revenues handed to the state, or some combinationthereof. This highlights the importance of understanding the nature of corporations in theextractive industries, as their extractive and selling operations necessarily contribute tothe development impact of resource wealth through affecting future political equilibria.Much of the literature either avoids or overlooks this fact.

Confirming that institutional quality is the most important channel through whichresource rents impact development does not mean that policymakers now have a silverbullet. Most economists who recognise the supremacy of institutions as an explanatoryvariable are quick to note that little is yet known about how best to strategically influenceinstitutional formation. They are also often the first to recognise that merely writing goodrules on paper is likely to be ineffectual, especially if those rules are incongruent with theinformal norms that characterise a particular elite bargain. In reflecting on a newgeneration of mining codes from across the continent, Besada and Martin observe anapparent effort to formulate policy that coheres with the African Mining Vision59 onpaper. In reality, however, they find that many contracts are secretly negotiated on termsthat do not fit the relevant code:

South African Journal of International Affairs 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

Corruption and patronage in the contracting and licensing of mining concessions impedeefficient tax administration and undermine the popular legitimacy of foreign-owned miningoperations. Yet even policy mechanisms like the [Extractive Industries TransparencyInitiative] EITI, which explicitly target transparency, are unlikely to reduce rent-seekingbehaviour without more fundamental institutional changes in African countries, includingrespect for the rule-of-law, independent judiciary and legal systems, and an informed andengaged citizenry.60

Both institutional change and institutional persistence are equilibrium outcomes of theinteraction between beliefs, culture, norms and historical path-dependence. Corruptionand patronage will therefore not disappear overnight because a new mining code has beendeveloped. This is not an argument against robust laws on paper, but a policy lesson thatmore research is required to understand country-specific institutional arrangements andthe incentives they generate. Better research may increase the likelihood of formulating,for instance, mining legislation (one of the most critical institutions for Africa) that isincentive-compatible with the distribution of political power and therefore credibly buildsinclusive development. The external imposition of best-practise governance initiativeswithout credible cooperation between all stakeholders at country level is likely to fail.

An integrated theoretical framework

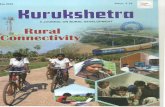

To frame this suggested research, it is beneficial to consider the work of North, Wallisand Weingast.61 Their 2009 book, Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Frameworkfor Interpreting Recorded Human History, provides the most appropriate theoreticalframework with which to examine how mineral and petroleum rents affect the politicalequilibrium, which ultimately affects development outcomes. The framework is designedto understand the dynamic interaction of political, economic and social forces indeveloping countries. It begins with the recognition that all societies must address thecentral problem of violence, which is to be restrained if development is to occur. Violenceis limited through manipulating economic interests by the political system to create rentsthat induce powerful groups and individuals to value cooperation over violence for thesake of maintaining present and future rent streams. Organising society in this way iscalled a Limited Access Order (LAO). A hallmark of an LAO is that political andeconomic elites strike personalised bargains in which they agree to limit access toavailable rents and rent-seeking opportunities by limiting the possibilities for outsiders tostart rival organisations. These elites form a dominant coalition to protect their rent streamthrough providing credible third-party enforcement of rent-sharing arrangements for eachof the member organisations. The dominant coalition in LAOs is held together by thiselite bargain, where elites agree to a particular set of political and economic institutions togenerate and distribute rents at the lowest possible cost and maximum benefit tothemselves:

The ability of elites to organise cooperative behaviour under the aegis of the state enhancesthe elite return from society’s productive resources – land, labour, capital andorganisations.62

Embedded incentives in this arrangement create ‘a double balance: correspondencebetween the distribution and organisation of violence potential and political power on theone hand, and the distribution of and organisation of economic power on the otherhand’.63 If society is to remain stable, then the political, economic, cultural, social and

10 Ross Harvey

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

military systems must contain compatible incentive structures, such that elites have noincentive to defect from cooperation. Figure 1 demonstrates the elite bargain and itsdouble balance.

The framework proposes a spectrum of LAO’s ranging from fragile to basic tomature. ‘As LAOs mature, a two-way interaction occurs between increasing thesophistication and differentiation of government organisation and the parallel develop-ment of (nonviolent) private organisations outside the state’.64 Generally, mature LAOsare more adaptively efficient and resilient to shocks than fragile or basic LAOs. OpenAccess Orders (OAOs), on the other hand, are characterised by open access to politicaland economic opportunity by any organisation. Only in these relatively few countries(basically the OECD states) does the state have a monopoly on violence (of the typicalWeberian conception). For an economy to transition from an LAO to an OAO, it has todevelop institutional arrangements that enable impersonal exchange among elites.Transition is catalysed when individual members of the dominant coalition have anincentive to expand this impersonal exchange to non-elites, causing the system toincrementally switch from the logic of limited access rent-creation to open access entry.

Brian Levy argues, in his chapter of the 2012 book65 that applies, refines and extendsthe 2009 North, Wallis and Weingast framework, that too many contemporary policyprescriptions assume an OAO; it is therefore not surprising that the policies do notsucceed, as they are incompatible with the elite bargain that characterises LAOs. Afteroffering a number of hypotheses worth pursuing in future work, Levy proposes that: ‘Onefinal layer of complexity, not adequately captured within the LAO framework …comprises the ways in which globalised engagement – with foreign investors and withdonors, as well as via global and regional geopolitics – influences interactions amongelites and between elites and non-elites’.66 Future research that aims to identify the likely

Figure 1. The elite bargain animating society’s double balance.Source: Author compilation.

South African Journal of International Affairs 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

development outcomes of natural resource endowments in Africa should thereforeendeavour to understand the nature of foreign investment in the extractive industries andits impact on the dynamics of the elite bargain in host countries.

Why China is important for understanding African development

Competition between Chinese and other foreign investors in mineral and hydrocarbon-wealthy African countries provides an instructive lens through which to explore Levy’sproposition. Incorporating this particular complexity, the LAO approach offers newinsights as to which governance and economic policy reforms would add value acrossdifferent country settings. The framework further provides a useful tool for exploring howforeign investment in the extractive industries affects the nature of the elite bargain in anygiven host country, conditioned on the pre-existing political settlement. Only once this isunderstood can policy reforms be initiated to ensure that commodities drive developmentrather than entrench ‘extractive’ elite interests at the expense of building inclusiveinstitutions.

Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) is of particular interest because Chinesecompanies operating abroad are not constrained by security-exchange listing rules andshareholder scrutiny.67 Also, to be rightly understood, ‘Chinese investment has to bedifferentiated into four different types, and its distinctive character unpacked – i.e., thebundling together of aid, trade and FDI’.68 Chinese state-owned entities are more subjectto the Chinese Communist Party’s ‘Going Out’ policy69 than to domestic law per se.Transparency and accountability are therefore potential casualties on the future resource-extraction path in SSA, in direct contrast to prescribed ‘best practice’ by initiatives suchas the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. Western companies, on the otherhand, are increasingly subject to domestic scrutiny, shareholder activism and ‘triple-bottom-line accounting’ in which social and environmental effects are measuredalongside financial profits. The London-based International Council on Mining andMinerals, for instance, relies on adherence to the Natural Resources Charter70 forassociated companies and a reputation effect to encourage transparent and accountableresource extraction abroad. Detailed below is a proliferation of recent research that aimsto understand the impact of specifically Chinese economic activity in Africa as it pertainsto natural resource acquisition.

China in Africa: resource acquisition

Alden and Alves write that ‘China’s energy concerns have been playing an increasinglycrucial role in its foreign policymaking in the new century’.71 These concerns are nowdominated by a demand for external oil. Having once been the leading Asian oil exporter,China is now the second largest global consumer and the third largest global importer ofoil. Imports of other minerals have also grown sharply in recent years. ‘China is theworld’s largest consumer and producer of aluminium, iron ore, lead and zinc, and holdssignificant shares in all other minerals supply and demand markets’.72 Contrary to TheEconomist’s account of ‘tied aid’ characterising trade between China and Africa, Aldenshows that the ‘infrastructure for resources’ approach carries no conditions. Alves’s paperon ‘resource for infrastructure’ contracts examines whether ‘this instrument is actuallypromoting African development or fuelling instead China’s growth at the expense ofAfrican economies’.73 Unsurprisingly, she concludes that the results are mixed (althoughclearly positive in terms of immediate infrastructure provision) and the extent of impact

12 Ross Harvey

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

cannot yet be fully established. Alves finds that most of the problems diagnosed in herstudy reflect institutional constraints within African countries.

Zweig and Jianhai indicate that China’s continued economic growth is dependent onsecuring natural resource supplies. They recognise that social stability, and therefore thesurvival of the Chinese Communist Party, are in turn contingent on this economicgrowth.74 While China’s social contract is characterised by social peace in exchange forcontinued employment opportunities, many analyses have been built on the assumption ofa continuation of China’s export-led growth model. However, the analytic emphasis mustshift in light of the Chinese Communist Party’s newly enacted twelfth five-year plan,which places a stronger emphasis on services and increased local consumption as pivotalaspects of China’s structural transformation away from manufacturing export-led growth.It foresees the completion of its industrialisation phase by 2020.75 In the short run,however, industrialisation in China continues apace, and – global recession notwithstand-ing – the demand for Africa’s minerals and hydrocarbons has continued to rise.76

For this reason, China’s search for resource security will remain a strong componentof its foreign policy.77 Africa possesses the world’s third largest oil reserves, boastingthe fastest growth rate in identified or ‘proven’ reserves. Non-fuel minerals are alsoabundant – South Africa is the leading producer of platinum and manganese, and theworld’s second largest gold producer; the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africaand Botswana together account for over half of global diamond-mining output and 60%of known deposits.78

China has contributed substantially towards addressing Africa’s ‘hard infrastructure’backlog – US$7 billion in 2006 alone.79 Its direct investment in natural resources andinfrastructure combined now stands at a value of at least $112 billion (includingcontracts) in Sub-Saharan Africa.80 This figure represents annual average growth of596%, from $512 million in 2005 to $28 billion in 2013 alone. However, Alden andAlves also make it clear that governance concerns are legitimate. ‘The arrival of China asan explicit alternative to the West has emboldened [African] regimes to pursue policiesthat might otherwise be subject to counteraction by the donor community andinternational financial institutions’.81 They also recognise that the exchange of rawmaterial exports for finished manufactured goods replicates Africa’s traditional tradepatterns with the industrialised West. Writing in 2009, they note that ‘[t]he recent fall incommodity prices highlights the dangers of reliance on this sole source of revenue andthe need for diversification’.82

Maswana obtains evidence that it is technology-embodied capital good importsfrom – and not exports to – China that appear to have had a positive effect on growth inAfrica.83 His findings suggest that gains from global trade depend less on the mere effectsof trading than on the ability of countries to appropriately position themselves along theglobal value chain. Such positioning ‘requires that African economic structures beadapted accordingly. Ultimately, the need to gradually curtail the export of raw materialsand focus on the processing or conversion of such materials before export has become alltoo obvious’.84 Historical attempts at downstream beneficiation suggest that such‘processing’ is not, however, the panacea to development challenges. Rather, these‘technology-embodied capital good imports’ should be employed to achieve dynamicallyefficient diversification that is more consistent with existing comparative advantage.

Consistent with Maswana, Baliamoune-Lutz finds ‘that [after having controlled forthe quality of institutions and the quality of government] there is a significant positivelinear effect from importing from China and it works (at least partly) through investment(and investment aiding goods)’.85 Moreover, the evidence indicates that only countries

South African Journal of International Affairs 13

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

with highly concentrated exports appear to benefit from exporting to China. Thiscontrasts with the prevailing view that resource-wealthy countries should generally aim todiversify their exports in order to escape Dutch-disease-type effects. Ackah, Kankam andAppiah-Adu produce evidence, for instance, that mineral resource abundance slowsgrowth in industrial output. They recommend that mineral revenues should be invested incapital and alternative energy sources to boost aggregate and industrial growth.86

However, for as long as China remains the primary driver of demand for raw materialexports, the benefits of export-concentration appear likely to continue until skillsshortages and infrastructure constraints – necessary for industrialisation – are alleviated.

The provision of hard infrastructure from China may partially contribute to thisalleviation: ‘The widely held claim that trade with (and FDI from) China may beexacerbating the poor levels of institutional quality and governance in Africa seems tomiss a crucial point: Africa seriously needs to develop its infrastructure and China seemswilling (in exchange for trade relations) to provide significant contribution [sic] in thisarea’.87 It is however unclear that infrastructure provision is sufficient to overcomeinstitutional concerns, especially in light of the long-run considerations of the impact ofpoor institutional quality on developing human and social capital.

Deborah Brautigam argues that China’s developmental involvement in Africa is likelyto be beneficial. She avoids patronising portrayals of African governments as helplessrecipients of predatory aid – China’s ventures into Africa are business deals.88 Brautigamis not naive about the potential production of negative political and economicexternalities, but brings perspective to the trends common in Western media andacademic thought.

In contrast, Kolstad and Wiig, along with Qian, Yu, de Haan and Cheung, challengeBrautigam and suggest that Chinese investors are innately attracted to resources located inpoorly governed countries,89 but this interpretation seems to overlook the simple fact thatglobal competition for resources is strong – many markets are already crowded andsupply-side scarcity may therefore force China to do business in poorly governedcountries. Moreover, recent media articles document a more risk-averse approach towardsAfrica by China, especially in the wake of a number of lost investments.90

Despite this already extensive academic literature, the question of how new mineraland hydrocarbon rents – generated by Chinese investment – will affect elite bargains andtheir associated ‘double balance’ in host countries remains unanswered. The question isparticularly important in light of anecdotal evidence which suggests that Chineseinvestment in Africa is eroding social and human capital on which Africa’s future well-being depends. Chinese companies involved in resource extraction operate under differentoperational constraints than companies bound by Western security-exchange listing rulesand regulations such as the Dodd–Frank Act, which penalises corruption. Examiningthese differing constraints is crucial to understanding the likely impact of resource wealthon development outcomes.

China in Africa: anecdotal evidence

Concerns have been raised that China has employed poor business practices on thecontinent in some cases.91 Chinese construction work, for instance, is alleged to beunreliable. A hospital in Luanda, Angola, developed ‘significant cracks’ that caused it toclose for repairs a few years after opening; also, rains washed away a large section of aChinese-built road from Lusaka to Chirundu in Zambia.92 In examples that reflect threatsto the natural environment, and thus to those that rely upon it for their livelihood,

14 Ross Harvey

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

Sinopec, a Chinese oil firm, was granted exploration permission rights in a Gabonesenational park, and a Chinese state oil company reportedly spilled crude in Sudan.93

Second, Chinese companies’ purchasing activities have been fingered for fuellingautocracy,94 which is generally undesirable for improving economic performance. In2011, diamonds from Zimbabwe’s Marange field were sold for the first time since theinternational ban on the country’s ‘blood diamonds’ was lifted: gem sales (worth £103million) were held on behalf of Anjin investments, a joint venture between a Chinesestate corporation and the Zimbabwean Army. One of the Zimbabwean directors of Anjinis Brigadier-General Charles Tarumbwa, a serving army officer who is barred bysanctions from travelling to or investing in Western countries.95 There are other examplesfrom Angola and Mozambique.

Third, bribery threatens to undermine institutions, reducing bureaucratic effectiveness.The World Bank has banned some Chinese companies from bidding for Bank-financedtenders in Africa for this reason.96 The Economist may be accused of selective reading,however, as Canadian and Swedish companies also appear on the list of debarred firms.97

Although Alden refutes the view, The Economist argues that many loans to Africangovernments are tied in so that the beneficiaries are required to purchase exclusively fromChinese companies.98 While not a practice unique to China, tied aid underminescompetition and constrains markets from punishing suboptimal work by donor firms,undermining incentives for delivering quality goods and workmanship. It may also createinformation asymmetry through overpricing, which can lead to creditors and donorssetting the wrong developmental priorities.

Fourth, financial deals between China and Africa may undermine governance effortstowards achieving revenue transparency. China Exim Bank and China DevelopmentBank, the main lenders to the continent, publish no figures about their loans to poorcountries.99 The ‘Queensway Syndicate’, officially known as the China InternationalFund or China Sonangol, perhaps best exemplifies these concerns: ‘Over the past sevenyears it has signed contracts worth billions of dollars for oil, minerals and diamonds fromAfrica … with regimes in strife-torn places, such as Zimbabwe and Guinea.100 Thesyndicate is the creation of Xu Jinghua,101 and thought by some to be an arm of theChinese state. Sources indicate that most of China’s imports of Angolan oil – worth morethan $20 billion in 2010 – come from China Sonangol.102

China is not alone among resource-hungry players operating under few constraints inAfrica. A report into the origins and activities of Glencore,103 for instance, suggests thatChinese activities should not be studied in isolation. Chinese investment interactions withother players’ interests on the continent would therefore be a further item for futureresearch.

Conclusion

Given continued commodity-dependent growth in SSA, increasing Chinese investmentpresence in the extractive industries, and the availability of a robust institutionalisttheoretical framework through which to examine the problem, future research shouldattempt to answer the following questions:

. How do mineral and hydrocarbon rents generated from Chinese investmentinfluence the dynamics of the elite bargain in respective host countries in SSA?

. Are rents generated from ‘resource-for-infrastructure’ contracts with China likely tochange the elite bargain in such a way as to disrupt the existing double-balance

South African Journal of International Affairs 15

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

equilibrium? Is the impact of these contracts likely to be different from other typesof investment?

. To what extent does the influence on the elite bargain depend on the type of pre-existing LAO settlement and how might this settlement alter as a consequence of ashifting elite bargain?

. What kind of incremental incentive-compatible institutional reforms could crediblybe employed in respective LAO settings to ensure more optimal developmentoutcomes from Chinese investment in the extractive industries?

In order to answer these questions, research must first examine who the principaldomestic elite groups are, how they relate to each other and international actors, and whatthreat disaffected elites pose to the dominant coalition. Existing formal and informalpolitical institutions that govern relationships between elites must also be examined,along with the ‘economic institutions that govern relationships between producers,consumers and factors of production’.104

Such a project should accomplish two things. First, it should accurately identify howinvestment in the extractive industries can affect the nature of the elite bargain in the hostcountry, given the importance of institutions for determining development outcomes fromresource dependence, and the fact that they have not yet been explored within a unifyingtheoretical framework. An accurate understanding in this respect is likely to lead to policyinitiatives that gain traction because they are incentive-compatible with the doublebalance between political and economic institutions and the elite bargain. Second, itshould contribute to the ‘New Institutional Economics’, ‘China in Africa’ and ‘resourcecurse’ literatures by addressing the respective gaps in these literatures and bridging themwhere relevant.

Note on Contributor

Ross Harvey holds an M.Phil in Public Policy from the University of Cape Town, and is aPhD student at the School of Economics, UCT. He works at the South African Institute ofInternational Affairs for the Governance of Africa’s Resources Programme as a visitingresearch fellow. His research interests include the political economy of mining in SouthAfrica, and mining’s contribution to development more generally across the Africancontinent.

Notes1. The Economist, ‘Hopeless Africa’, 11 May 2000, <http://www.economist.com/node/

333429>.2. August O, ‘A hopeful continent’, The Economist, 28 February 2013, <http://www.economist.

com/news/special-report/21572377-african-lives-have-already-greatly-improved-over-past-decade-says-oliver-august>.

3. Martinez M & M Mlachila, ‘The quality of the recent high-growth episode in Sub-SaharanAfrica, 2013’, International Monetary Fund (IMF) Working Paper, WP/13/53.

4. Acemoglu D & JA Robinson, Why Nations Fail, New York: Crown Publishers, 2012.5. Martinez M & M Mlachila, ‘The quality of the recent high-growth episode in Sub-Saharan

Africa, 2013’, IMF Working Paper, WP/13/53.6. The term ‘unproductive rent-seeking’ is used to distinguish it from its potentially productive

counterpart. The political economy literature tends to define ‘rent-seeking’ as inherentlypernicious – political insiders capturing revenue streams at the expense of the public good.See Olson M, Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965.

16 Ross Harvey

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

However, even societies with strong institutions have politicians who attempt to generaterents. The difference is that these societies tend to impose binding constraints ofaccountability and transparency, which limit the potential pernicious effects on the commongood.

7. Yergin D, ‘The global impact of US shale’, Project Syndicate, 8 January 2014, <http://www.project-<syndicate.org/commentary/daniel-yergin-traces-the-effects-of-america-s-shale-energy-revolution-on-the-balance-of-global-economic-and-political-power>.

8. Roach S, ‘China’s growth puzzle’, Project Syndicate, 27 February 2014, <http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/stephen-s–roach-says-that-china-s-economic-slowdown–unlike-that-in-other-emerging-countries–should-be-welcomed>.

9. There is an extensive literature on this hypothesis now, although it has yet to be understoodwithin a unified theory. A relative consensus appears to be emerging that institutional qualityat the time of discovering an exploitable mineral or hydrocarbon deposit is primarilydeterminative of the likely development outcome of that wealth. For the best recentoverview, see Van der Ploeg F, ‘Natural resources: Curse or blessing?’, Journal of EconomicLiterature, 49.2, 2011, pp. 366–420.

10. The World Bank, World DataBank, World Development Indicators, <http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx> (accessed 26 March 2014).

11. Martinez M & M Mlachila, ‘The quality of the recent high-growth episode in Sub-SaharanAfrica, 2013’, IMF Working Paper, WP/13/53, p. 3.

12. Ibid.13. Ibid., p. 4.14. Arbache JS & J Page, ‘How fragile is Africa’s recent growth?’, Journal of African

Economies, 19.1, 2009, p. 21.15. Ibid.16. Robinson JA, R Torvik & T Verdier, ‘Political foundations of the resource curse’, Journal of

Development Economics, 79.2, 2006, pp. 447–68.17. These terms are largely interchangeable in the literature, and refer to the divergence between

social costs and private returns. Externalities are those costs or benefits produced by a firmbut not taken into account by market prices. See Scheffer M, F Westley & W Brock, ‘Slowresponses of societies to new problems: Causes and costs’, Ecosystems, 6, 2003, pp.493–502.

18. Aghalino SO, ‘Gas flaring, environmental pollution and abatement measures in Nigeria,1969–2001’, Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 11.4, 2009, pp. 219–38.

19. Van der Ploeg F, ‘Natural resources: Curse or blessing?’, Journal of Economic Literature,49.2, 2011, pp. 366–420.

20. Sarr M & T Swanson, ‘Corruption and the resource curse: The dictator model’, January 2012,<http://www.cer.ethz.ch/sured_2012/programme/SURED-12_073_Sarr_Swanson.pdf>.

21. North D, ‘The New Institutional Economics’, Journal of Institutional and TheoreticalEconomics, 142.1, March 1986, pp. 230–7.

22. Some authors still hold this view, even though it has been consistently debunked. See, forinstance, Chang HJ, ‘Institutions and economic development: Theory, policy and history’,Journal of Institutional Economics, 7.4, 2011, pp. 473–98. His critique was successfullyrefuted (in the same volume) by Keefer P, ‘Institutions really don’t matter for development?A response to Chang’, Journal of Institutional Economics, 7.4, 2011, pp. 543–7.

23. Acemoglu D & JA Robinson, ‘The colonial origins of comparative development: Anempirical investigation’, The American Economic Review, 2001, p. 1370.

24. Ibid.25. Ibid., p. 1371.26. Ibid., p. 1395.27. ‘Discount rates’ are the rates at which people discount the future. In other words, they reflect

the value tht one places on that future. If the future is uncertain (or one expects negativeutility from it), for instance, one may wish to cash in one’s investments in the present, asopposed to waiting for the value of that investment to grow over time. That would constitutea high discount rate. For politicians in volatile contexts, the future is often uncertain,increasing the incentive to amass wealth in the present (or while access to wealth through theexercise of political power is available). See Becker G & CB Mulligan, ‘The endogenous

South African Journal of International Affairs 17

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

determination of time preference’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112.3, pp. 729–58.The explanation on p. 741 is especially helpful.

28. Acemoglu D & T Verdier, ‘Property rights, corruption and the allocation of talent: A generalequilibrium approach’, The Economic Journal, 108, 1998, pp. 1382–95.

29. Acemoglu D & JA Robinson, ‘The colonial origins of comparative development: Anempirical investigation’, The American Economic Review, 2001, p. 1376.

30. Ibid., p. 1376.31. Glaeser EL, RL Porta, F Lopez-de-Silanes & A Shleifer, ‘Do institutions cause growth?’,

Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 2004, p. 290.32. Ibid., p. 296.33. Djankov S, R La Porta, F Lopez-de-Silanes & A Shleifer, ‘The new comparative

economics’, Journal of Comparative Economics, 31.4, 2003, pp. 595–619.34. Glaeser EL, RL Porta, F Lopez-de-Silanes & A Shleifer, ‘Do institutions cause growth?’,

Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 2004, p. 297.35. Ibid., p. 298.36. Rodrik R, ‘Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography and integration in

economic development’, Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 2004, p. 135.37. Ibid., p. 154.38. Acemoglu D & JA Robinson, Why Nations Fail. New York: Crown, 2012, p. 377.39. Acemoglu D, FA Gallego & JA Robinson, ‘Institutions, human capital and development’,

prepared for the Annual Review of Economics, available at <http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/jrobinson/files/acemoglu_gallego_robinson_final_jan_31_2014.pdf>.

40. Ibid., p. 5.41. Ibid., p. 6.42. Ibid.43. Bates RH, SA Block, G Fayad & A Hoeffler, ‘The new institutionalism and Africa’, Journal

of African Economies, 22.4, pp. 499–522. See also a working paper by Acemoglu D, SNaidu, P Restrepo & JA Robinson, ‘Democracy does cause growth’, National Bureau ofEconomic Research, Working Paper 20004, March 2014, NBER: Massachusetts. Availableat <http://www.nber.org/papers/w20004>.

44. Glaeser EL, RL Porta, F Lopez-de-Silanes & A Shleifer, ‘Do institutions cause growth?’,Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 2004, p. 297.

45. Granger causality is different from other types of causation, and was specifically designed tocapture time sequence – yt occurs before xt+1 and therefore may suggest a causal relationshipbetween the two – and y contains useful information for forecasting what xt+1 might looklike. For further information, see <http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Granger_causality>.

46. Ibid., p. 519.47. Ibid.48. Mehlum H, KO Moene & R Torvik, ‘Institutions and the resource curse’, Economic Journal,

116.508, 2006, pp. 1–20. See also Mehlum H, KO Moene & R Torvik, ‘Cursed by resourcesor institutions?’, The World Economy, 29.8, 2006, pp. 1117–31.

49. Sachs J & A Warner, ‘Natural resources abundance and economic growth’ in Meier G & JRauch (eds), Leading Issues in Economic Development. New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 1995.

50. Luong PJ & E Weinthal, ‘Rethinking the resource curse: Ownership structure, institutionalcapacity, and domestic constraints’, Annual Review of Political Science, 9, pp. 241–63.

51. Quinn JJ & RT Conway, ‘The mineral resource curse in Africa: What role does majority stateownership play?’, The Center for the Study of African Economies Conference 2008: AfricanEconomic Development, St Catherine’s College, Oxford, 16–18 March 2008.

52. Ownership of a resource is fundamentally an institutional question, as one of the mostimportant institutions for economic growth is the protection of private property rights.

53. Robinson JA, R Torvik & T Verdier, ‘Political foundations of the resource curse’, Journal ofDevelopment Economics, 79.2, 2006, pp. 447–68.

54. Ibid., p. 450.55. Leong W & K Mohaddes, ‘Institutions and the volatility curse’, CWPE 1145, 2011.56. Ibid., p. 9.57. Acemoglu D & J Robinson, ‘Economics versus politics: Pitfalls of policy advice’, National

Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper w18921, p. 21.

18 Ross Harvey

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

58. Ibid., pp. 8–9.59. The African Mining Vision was designed by the African Union as a continent-level vision,

which would subsequently inform country-level visions. Further information can be found at<http://www.africaminingvision.org/index.htm>.

60. Besada H & P Martin, ‘Mining codes in Africa: Emergence of a “4th generation”?’, TheNorth–South Institute Research Report, May 2013, <http://www.nsi-ins.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Mining-Codes-in-Africa-Report-Hany.pdf>.

61. North DC, JJ Wallis & BRWeingast, Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Frameworkfor Interpreting Recorded Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

62. Ibid., p. 20.63. Ibid.64. North DC, JJ Wallis, S Webb & BR Weingast (eds), In The Shadow of Violence: Politics,

Economics, and the Problems of Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.65. Ibid.66. Levy B, ‘Seeking the elusive developmental knife edge: Zambia and Mozambique—A tale

of two countries’, in North DC, JJ Wallis, S Webb & BR Weingast (eds), In The Shadow ofViolence: Politics, Economics, and the Problems of Development. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press, 2012, p. 112.

67. For a good example of how security exchange listings and associated laws can constrain acompany’s actions, refer to the case of Gold Fields, a major mining firm. It was found guilty ofbribery in South Africa by an independent investigation that the firm itself commissioned. TheUS Securities Exchange Commission now seems likely to investigate the company. SeeHolmes T, ‘Gold Fields vice-president resignation unlikely to affect BEE investigation’,Mail &Guardian, 24 January 2014, <http://mg.co.za/article/2014-01-24-gold-fields-vice-president-resignation-unlikely-to-affect-bee-investigation>.

68. Kaplinsky R & M Morris, ‘The policy challenge for Sub-Saharan Africa of large-scaleChinese FDI’, Real Instituto Elcano ARI Working Paper, 169, 2010, p. 1.

69. Shambaugh D, China Goes Global: The Partial Power. New York: Oxford University Press,2013. For a brief review, see <http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2013/07/08/book-review-china-goes-global-the-partial-power/>.

70. See Precept 12 for specific reference to how firms are expected to behave in foreigncountries, <http://naturalresourcecharter.org/content/precept-12>.

71. Alden C & AC Alves, ‘China and Africa’s natural resources: The challenges andimplications for development and governance’, Occasional Paper, 41. Johannesburg: SouthAfrican Institute of International Affairs, September 2009, p. 4.

72. Ibid., p. 5.73. Alves AC, ‘China’s “win–win” cooperation: Unpacking the impact of infrastructure-for-

resources deals in Africa’, South African Journal of International Affairs, 20.2, 2013, pp.207–26.

74. Zweig D & B Jianhai, ‘China’s global hunt for energy’, Foreign Affairs, 84, 2005, pp.25–38.

75. Roach S, ‘China’s turning point’, Project Syndicate, 24 February 2011, <http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-s-turning-point>.

76. See Cheung YW & J De Haan, (eds), The Evolving Role of China in the Global Economy.Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012. For a brief review, see <http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2013/04/15/book-review-the-evolving-role-of-china-in-the-global-economy/>.

77. Shambaugh D, China Goes Global: The Partial Power. New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 2013.

78. All figures are for 2007 and are based on data from US Geological Survey, MineralCommodity Summaries 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of the Interior, USGeological Survey, 2008.

79. World Bank/Public–Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility, Building Bridges: China’sGrowing Role as Infrastructure Financier for Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: WorldBank, 2009, p. 29, <https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/2614/480910PUB0Buil101OFFICIAL0USE0ONLY1.pdf?sequence=1>.

80. Data is extracted from a database constructed by the Heritage Foundation and the AmericanEnterprise Institute, available at <http://www.heritage.org/research/projects/china-global-investment-tracker-interactive-map>, which Brautigam recommends as the most reliable

South African Journal of International Affairs 19

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f C

ape

Tow

n L

ibra

ries

] at

01:

35 2

8 A

ugus

t 201

4

database tracking Chinese FDI worldwide. I filtered only sub-Saharan African countries inthe transport, energy and metals sectors from 2005 to 2014.

81. Alden C & AC Alves, ‘China and Africa’s natural resources: The challenges andimplications for development and governance’, Occasional Paper 41. Johannesburg: SouthAfrican Institute of International Affairs, September 2009, p. 18.

82. Ibid.83. Maswana J, ‘Can China trigger economic growth in Africa: An empirical investigation based

on the economic interdependence hypothesis’, The Chinese Economy, 42.2, 2009, pp.91–105.

84. Ibid., p. 103.85. Baliamoune-Lutz M, ‘Growth by destination (where you export matters): Trade with China

and growth in African countries’, International Center for Economic Research, WorkingPaper 22, 2010, p. 12.

86. Ackah I, D Kankam & K Appiah-Adu, ‘Does a windfall lead to a downfall? A study ofmineral rents and genuine growth in selected African countries’, Journal of Energy andNatural Resources, 3.1, pp. 6–10.

87. Ibid., p. 14.88. Brautigam D, The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2009.89. Kolstad I & A Wiig, ‘Better the devil you know? Chinese foreign direct investment in

Africa’, Journal of African Business, 12.1, 2011, pp. 45–6, and Cheung YW, Jde Haan,X Qian & S Yu, ‘China’s Investments in Africa’, in Cheung YW & J De Haan, (eds), TheEvolving Role of China in the Global Economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

90. Wild F, ‘China learns from errors and tones down in Africa’, Business Report, 4 June 2014,<http://www.iol.co.za/business/news/analysis-china-learns-from-errors-and-tones-down-in-africa-1.1698204#.U5F_MRb6pc8>.