Murder on Grimm Isle: The impact of game narrative design in an educational game-based learning...

Transcript of Murder on Grimm Isle: The impact of game narrative design in an educational game-based learning...

Murder on Grimm Isle: The impact of game narrativedesign in an educational game-based learning environment_

1032 456..469456..469

Michele D. Dickey

Michele Dickey is an associate professor at Miami University with a joint appointment in InstructionalDesign and Technology and Interactive Media Studies. Her current areas of research include interactivemedia and the use of emerging technologies for education. Address for correspondence: Dr MicheleDickey, Department of Educational Psychology, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056, USA. Tel:513-529-3741; email: [email protected]

AbstractThe purpose of this research is to investigate the impact of narrative design ina game-based learning environment. Specifically, this investigation focuses thenarrative design in an adventure-styled, game-based learning environment forfostering argumentation writing by looking at how the game narrativeimpacted player/learner (1) intrinsic motivation, (2) curiosity, (3) plausibilityand (4) transference of game-based experiences into prewriting activities. Themethodological framework for this qualitative investigation is a case studywith grounded theory methodology. The setting is an educational, three-dimensional, immersive game-based learning environment titled Murder onGrimm Isle, used to foster argumentation and persuasion writing for Grades9–14. The participants included 20 college students. The findings of the inves-tigation reveal that intrinsic motivation, curiosity and plausibility were firstsupported by the game-like environment, and then sustained through thenarrative and the environment. Additionally, game-based experiences weretransferred into prewriting activities. Unanticipated findings revealed somestudent resistance. The goal of this research is to gain a better understandingof narrative design for game-based learning environments.

IntroductionNarrative structure is a pervasive part of human cognition; it is the means by whichhumans frame and recount daily experiences (Bruner, 1990; Polkinghorne, 1988). Yet,despite the ubiquitous nature of narrative, relatively little research has been conductedabout the design of compelling narratives for education. Within educational materials,narrative has often been based upon a linear timeline. This likely can be attributed to thefact that books, films and videos often serve as the primary medium for educational

British Journal of Educational Technology Vol 42 No 3 2011 456–469doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01032.x

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta. Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 GarsingtonRoad, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

media. However, with the onset and growing interest in game-based learning, digitalgaming environments illustrate how space and architecture can be used as compellinginfrastructures for narrative, based on spatial relationships, rather than timelines.Digital games are narrative spaces that foster imagination and play (Jenkins, 2002;Thomas & Brown, 2007). These narrative spaces allow players to interact with otherplayers, nonplayer characters and the environment. Virtual environments, such asthose found in three-dimensional (3D) games, allow players to experience a storythrough an imagined physical space (Carson, 2000).

The design of digital games is a rich topic of study for educational researchers andinstructional designers studying ways in which game design can be appropriated, bor-rowed and re-purposed for the design of educational materials (Bowman, 1982; Dickey,2005b, 2006, 2007; Gee, 2003; Malone, 1981; Prensky, 2001; Provenzo, 1991;Rieber, 1996; Squire, 2003). Although the field of digital games is very broad, the areaof game narrative is a compelling area of study ripe with research opportunitiesfor investigating how environmental narratives can be harnessed for teaching andlearning.

The purpose of this research is to investigate the impact of narrative design in a game-based learning environment. Specifically, this investigation focuses the narrative designin an adventure-styled, game-based learning environment for fostering argumentationwriting by looking at how the game narrative impacted player/learner (1) intrinsicmotivation, (2) curiosity, (3) plausibility and (4) transference of game-based experi-ences into prewriting activities. The goal of this research is to gain a better understand-ing of narrative design for game-based learning environments.

Literature reviewWithin the literature of games and learning, Malone’s (1981) seminal investigation ofgames is one of the most often cited analysis of the types of game elements that appealto players. Malone identified fantasy as being one of the key elements of games thatsupported intrinsic motivation. The element of fantasy, first identified by Malone andlater used in respective works by Provenzo (1991) and Rieber (1996), is of significantimportance in investigating the role of narrative in game-based learning. Malone char-acterised fantasy as being either extrinsic or intrinsic to gameplay. Malone argued thatintrinsic fantasy is more interesting and potentially more instructional because it mayindicate how a skill might be used in a real-world setting, and provides metaphors oranalogies to aid in understanding.

Rieber (1996) similarly characterised fantasy in games as either exogenous or endog-enous to the context of a game. Like Malone’s (1981) characterization of extrinsic andintrinsic fantasy, Rieber argued that exogenous (extrinsic) fantasy is frivolous and extra-neous, and has no impact on gameplay (p. 49). Endogenous fantasy (intrinsic), incontrast, is integral to the content of the game and is more suited to educational gamesbecause it may potentially motivate learners interested in the fantasy.

MOGI: Impact of game narrative 457

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

Within the field of game design, the element of fantasy, such as that noted by Malone(1981), Provenzo (1991), Rieber (1996), and more recently, Gee (2003), is a type offictional narrative. Narrative is ubiquitous in human reasoning and allows humans toassign meaning to their experiences (Bruner, 1990). Humans use narrative not only toframe thought, but also to guide actions (Polkinghorne, 1988). According to Robinsonand Hawpe (1986), narrative is a type of causal thinking in which the narrative (cogni-tive) schema identifies categories (protagonist, situation, conflict, outcome, etc) andrelevant types of relationships (temporal, motivational and procedural). Thinkingwithin a narrative framework requires one to integrate experiences (which do notnecessarily occur in narrative form) into a plausible storyline (Robinson & Hawpe,1986).

Plausibility in a game narrative is established through the interplay between charac-ters, events and the environment. The context and setting, in the form of the narrativebackstory, establish boundaries of what is plausible by outlining the parameters forwhat is plausible within the context of the game. Players make conjectures aboutovercoming obstacles and solving problems based upon what is plausible within theseboundaries. Discovery and trial and error play a role in this process; however, thenarrative provides a cognitive framework for problem solving by establishing what isplausible for constructing causal relationships.

It is within the framework of narrative plausibility where curiosity is initiated. Accord-ing to Berlyne (1960), curiosity is a necessary precondition for exploration. Becauseexploration is a key aspect of many genres of contemporary games, design that fosterscuriosity is an important aspect of game design.

The notion of ‘game’ is an ambiguous term used to describe structured recreationalactivities. Typically, components of games include goals, rules, challenges and someform of interaction (Avedon & Sutton-Smith, 1971; Caillois, 2001; Crawford, 2003;Rollings & Adams, 2003; Salen & Zimmerman, 2003). While individual definitions mayvary, games are primarily recreational, including challenges or some form of stimula-tion, and typically, in varying degrees, have some type of victory/loss conditions. Incontrast, serious games are games designed with a purpose beyond that of recreation orentertainment. Serious games encompass games designed to educate, train, inciteactivism, inform, persuade, express, recruit or indoctrinate (Bergeron, 2006; Michael &Chen, 2005). Within this continuum are game-based learning environments. Game-based learning leverages many of the intrinsic motivational aspects of play along withcommon components of games (rules, narrative, challenge and interaction) for thepurposes of formal and informal learning. Typically, game-based learning also includesinstructional components such as learning objectives and/or outcomes. Game-basedlearning may be manifested in many different forms, including the use of entertain-ment games for education (Squire, 2003), the design of immersive learning environ-ments (Barab, Thomas, Dodge, Carteaux & Tuzun, 2005; Ketelhut, Dede, Clarke, Nelson& Bowman, 2008) and the use of virtual worlds for learning (Bailey & Moar, 2001,2002; Barab, Hay, Barnett & Squire, 2001; Bers, 1999; Bers & Cassell, 1999;

458 British Journal of Educational Technology Vol 42 No 3 2011

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

Bruckman, 1997; Corbit & DeVarco, 2000; Dickey, 2005a). The purpose of game-basedlearning is to leverage the motivational and design affordances of games and play withpedagogy.

MethodsThe methodological framework for this qualitative investigation is a case study. Thereason for choosing qualitative methodology for this study is not to provide judgementabout the impact or design of a game-based narrative for teaching and learning,but rather to gain a better understanding of how to design compelling learningenvironments.

Embedded within this case study framework is grounded theory methodology (Glaser &Strauss, 1992; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Grounded theory methodology may be char-acterised as a method of data collection and analysis in which theory emerges from datagathered rather than being identified a priori.

The setting for this investigation is an educational game-based learning environmenttitled Murder on Grimm Isle (MOGI). MOGI is an immersive 3D gaming environmentused to foster argumentation and persuasion writing for Grades 9–14. The participantsin this investigation were 20 undergraduate students at a midsized state university inthe Midwest of the USA. All of the participants characterised themselves as digitalgameplayers.

Data collection included observations of student interaction, including chat logs of chatwithin the game, observations of student activity within the computer laboratorysetting, questionnaires about the use of MOGI and informal interviews. Additionally,peer debriefing, members’ check, negative case samples and an audit trail were part ofthe qualitative methodology as recommended by Glaser and Strauss (1967) andLincoln and Guba (1985). Peer debriefing consisted of both formal reviews of the datawith a colleague in the field of technology as well as informal reviews with differentcolleagues. Member checks were conducted informally during the process of data col-lection. Negative case analysis was conducted by re-examining the data to identifysamples that displayed variation or contradicted the overall interpretations. Addition-ally, an audit trail was collected based on Lincoln and Guba’s six categories of informa-tion (p. 319). Within this study, these sources included observation notes, screencaptures, chat logs, student work, email interactions and instruments. This triangula-tion of multiple-data collection and methods was designed to support trustworthiness(Erickson, 1986); however, it should be noted that the interpretation of data was stillsubjective (Fine, 1994; Peshkin, 1988).

In keeping with grounded theory methods, data analysis was part of an iterativeprocess. Data gathered from the participants’ experiences in the game-based learningenvironment were used to help shape and guide subsequent iterations of interviews.Additionally, Miles and Huberman’s (1994) variable-oriented and pattern-clarificationstrategies for identifying themes and patterns were used in the iterative process. During

MOGI: Impact of game narrative 459

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

the ‘open-coding’ process, potential themes were initially identified based on data col-lected during in-game experiences. During that time, emergent themes were identified(Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

No qualitative data software tools were used. Because the majority of materials con-sisted of either observations, notes or in digital format, the researcher has developedmethods for data management and analysis. Mind Manager Pro (Mind Mapper Pro.SimTech Systems. Lewisville, TX. USA) was used as a concept-mapping tool to identifyrelationships between emerging themes.

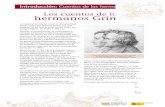

Narrative overview: MOGIMOGI is a game-based learning environment designed to foster argumentation writingskills for Grades 9–14 language arts students. The setting for MOGI is a multi-user 3Dinteractive environment in which learners are able to move through an environment tocollect evidence.

The narrative storyline of MOGI focuses on a wealthy attorney and environmentalist,Robson Wolfe, who has been found dead in the Wolfe mansion. There are three mainsuspects for the crime (Scarlett Ryding-Hood, her stepgrandmother Mimi Ryding-Hoodand the Ryding-Hood Estate’s handyman Mark Woodsman). Learners are cast in therole of investigators sent to Grimm Isle to gather evidence and determine a culprit.Because of an impending hurricane, all of the citizens of Grimm Isle have been evacu-ated, and investigators have a short time to collect evidence. None of the characters ispresent in the environment, rather, learners develop a sense and understanding of thecharacters based on the evidence encountered in each character’s home. The evidenceis in the form of artefacts (footprint, bottle, glasses, etc), documents (last will andtestament, books, messages, etc) and voicemail messages. Learners may click upon anevidence and examine it as well as save it to review after they leave the island. Learnersdetermine the culprit based on the evidence they gather, and use the evidence tosupport their argument.

The narrative environment of MOGI is loosely based on the adventure game genre asfound in Myst, Syberia and the Nancy Drew series, but with the type of 3D exploratoryenvironment similar to massively multiple online role-playing games. While MOGI isbased on the adventure game genre, MOGI was not designed for entertainment; it wasdesigned expressly to foster argumentation/persuasion writing skills. To this end, thereis no one single narrative to uncover. The goal is not to ‘win the game’, rather, the goalis to construct a cohesive argument. The purpose for creating MOGI was (1) to fostermotivation by leveraging game-like components of narrative and exploration, (2) toallow learners to construct arguments based on a combination of artefacts and text (asopposed to text-based methods of teaching argumentation), and (3) to allow learners toconstruct an understanding of argumentation/persuasion based on first-person non-symbolic experiences as opposed to ‘third-person symbolic experiences’ (Winn, 1993),as is often typified in traditional argumentation/persuasion writing. Within MOGI,there is no one single narrative to uncover, rather, the narrative differs depending upon

460 British Journal of Educational Technology Vol 42 No 3 2011

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

which homes a learner visits and the evidence he/she discovers. In effect, each learnerco-constructs the narrative based on his/her experience in the environment.

FindingsIn keeping with the qualitative methods of this study, the findings include first theobservations of students’ interactions within the laboratory and in the game-basedenvironments. The observations are then followed by the students’ reports, includingdata gathered from informal interviews, student work and class discussions.

Intrinsic motivationUpon entering MOGI, learners land outside of a gate facing the Wolfe mansion. Withinthe main room of the Wolfe mansion is a chalk outline of the deceased with whatappears to be a wine glass near the extended hand of the outline (see Figure 1).However, there is no single path through the environment; learners are free to moveand explore wherever they choose.

ObservationsAll of the participants in this investigation initially travelled into the mansion to begintheir exploration. All of the participants began by selecting the wine glass, which is akey piece of evidence because it reveals the cause of death. After selecting the wineglass, most participants began exploring the surrounding area or other parts of theroom.

Figure 1: The crime scene

MOGI: Impact of game narrative 461

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

Five participants spent limited time in the room and instead chose to search for anothercharacter’s home. Twelve remained in the room and began to speculate aloud, based onthe limited information they had collected, while three other participants began tocarefully scrutinise the outside grounds surrounding the mansion. When several stu-dents found a piece of evidence, they often announced it aloud.

I found a note near the deskYeah, I found that one already

Click on the bottle on the floorWhich one?There’s only one

As the participants began to read and view encountered pieces of evidence, theybecame noticeably quieter. Five students continued to share evidence with one anotherboth aloud and using the text chat. As participants began accumulating evidence, theybegan to make connections between the pieces of evidence. Although projective at best,it seemed as though the dynamics of the group began to shift as participants began tofocus more upon the evidence and less upon informing their classmates of their success.

ReportsDuring informal interviews, six participants indicated they initially thought that MOGIwas ‘going to be like Clue’ and that their role was to uncover the correct evidence to findthe culprit. Nine participants reported confusion because the game did not follow theirexpectations.

I thought I could collect evidence and find the murderer

The evidence wasn’t what I expected

I was confused when I saw a picture of the wine bottle, but when I read the label, I kindawondered about why there was a wine bottle from that winery

When I found that book, I started to think that maybe Scarlett might have been a little crazy

I remembered seeing those two valentine cards and both were from Mark. I wondered if he was aplaying both of them.

DiscussionIn the initial introduction of MOGI, participants were informed that this was a ‘game-based learning environment’ and not a game per se. Nevertheless, it initially appearedas though many students found the notion of ‘a game’ to be intrinsically motivatingand began to approach MOGI as a ‘game’ inherent with competition. Many participantswanted to know how many pieces of evidence were in the environment and how muchtime they had to find them. The instructor answered each question with ‘I don’t know.I haven’t investigated’.

462 British Journal of Educational Technology Vol 42 No 3 2011

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

Overall, the participants seemed initially to be intrinsically motivated by the notion of a‘game’, and immediately looked for game-like patterns and mechanics. All of the stu-dents were familiar with adventure-style games and immediately looked for patterns tomatch their schema for how MOGI should work. As they began identifying components(evidence), they began looking at the components as clues for uncovering the narrative.This is how one plays an adventure-style game. However, the disjuncture occurredwhen the evidence indeed was not a ‘clue’ and did not unlock or reveal a section ofnarrative. This was disconcerting for several students until they became acclimated tothe fact that this was not an adventure-style game, but rather a narrative environmentthat allowed them to make conjectures and construct their interpretation of the eventsthat resulted in the death of Robson Wolfe. The instructor stressed this was not a game,but a game-based learning environment; however, the majority of participants seemedto focus on the notion of ‘game’.

All of the students quickly became acclimated to the shift between their expectations of‘the game’ and the delivery of the game-based learning environment. One aspect thatfostered this transition between expectations and their experiences was curiosity. Theevidence and the environment fostered curiosity, which motivated the students to con-tinue with the experience rather than abandoning it when the environment did notsupport their pre-existing schema.

CuriosityBoth Malone (1981) and Provenzo (1991) note the importance of curiosity in gamedesign as an element that promotes user engagement. In addition to being a componentthat helped in the transition between the learners’ schema of an ‘adventure game’ andtheir experience in a game-based learning environment, in varying degrees, curiosityalso played a key role in participants’ perception and engagement in MOGI.

ObservationsWhile some of the participants continued to explore the Wolfe mansion, others beganexploring other locations. Three visited Scarlett’s cottage while the majority moved tothe Ryding-Hood Estate. As the dynamics of the group shifted, there was noticeably lessstudent-to-student interaction in terms of reporting evidence. Instead, dynamicsshifted to a type of ‘think aloud’ verbalizing.

Why is the wine bottle from the Ryding-Hoods? Ohh. ...

This is the same valentine as in the other house? Mark sent them both?

Who wrote that message?

Where does the boot print come from?

Did you read Scarlett’s message? I think she might have been stalking him, right?

MOGI: Impact of game narrative 463

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

ReportsIn informal interviews, several participants each noted different pieces of evidence thatseemed to pique their curiosity and engage their interest. Four students reported theircuriosity was not piqued by any one piece of evidence, but rather by their curiosity toexplore the environment.

DiscussionCuriosity played a significant role in the dynamics of MOGI. The environment andevidence were purposefully designed to suggest several narrative themes; however,there is no one single narrative storyline. As students began to move through the othercharacters’ homes, the group dynamics shifted more towards introspection, with someparticipants thinking aloud as they began to make connections between the pieces ofevidence they had collected.

PlausibilityPlausibility is the result of the interplay between the narrative storyline and the affor-dances of a game environment. The narrative outlines the parameters of plausibility,but the environment must provide affordances that are consistent with the narrative.

ObservationsAs the session continued and participants encountered more evidence, several began toco-construct narratives based on what they had encountered. Several speculated aloudto the group to test their hypothesis, while others asked the professor if they hadcorrectly identified the culprit.

I think Mimi did it cause she wanted the money, right?

Scarlett did it, but I don’t think she meant to, right?

One interesting note was that three participants attempted to interweave aspects of theenvironment into their narrative, which was not intended. Although MOGI includedthe four homes of the characters, it also included a small town. Although initially thetown was designed to also include evidence, this was abandoned because of issues oftime and project scale. The town was left in place to give the sense of a complete islandenvironment. Most participants explored the town, but most moved to other locationswhen they did not uncover any evidence; however, three students remained in the townarea looking for evidence. Although they did not uncover any, they attempted to inter-weave the town into their narratives, including constructing speculations of conflicts inthe town between non-existent citizens and the main characters.

ReportsEighteen of the 20 participants provided speculations about what they thought hap-pened, and identified a culprit. Speculations focused primarily on themes of love orgreed, or a combination of both.

TransferenceThe purpose for creating MOGI was (1) to foster motivation by leveraging game-likecomponents of narrative and exploration, and (2) to allow learners to construct an

464 British Journal of Educational Technology Vol 42 No 3 2011

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

understanding of argumentation/persuasion based on first-person nonsymbolic expe-riences as opposed to ‘third-person symbolic experiences’ (text). The intended learningoutcome of this class activity was for learners to construct and support an argumentboth by identifying a culprit and by using the evidence they had uncovered to supporttheir arguments.

Towards the end of the session, participants were asked to participate in argumentationprewriting activities by identifying the culprit and providing three pieces of evidence tosupport their allegations. This also included a paragraph synopsis of what they thoughtoccurred. Nearly 80% of students listed either Scarlett or Mimi (40% each), and only20% listed Mark Woodsman as the culprit. One notable observation during the sessionrevealed that Mark’s home was visited the least despite being clearly marked on the mapprovided. Eighteen students identified a culprit and provided at least three pieces ofevidence to support their allegations. It should be noted that the focus of this investi-gation was on formative aspects of the design, rather than on a summative report of theeffectiveness of the game-based learning environment; however, 18 of the studentscompleted the task of identifying a culprit and provided suitable evidence to supporttheir allegations.

The allegations were presented by the students in narrative format and varied in boththe identification of the culprit and the evidence presented. For example, narratives thatincluded various versions of Scarlett as the culprit included some accounts of Scarlettinnocently murdering Wolfe (‘she poisoned him by accident’) to various themes ofrejection (‘she was mad because he rejected her’ and ‘she was stalking him’). Interest-ingly, many of the differing accounts relied on much of the same evidence to supportallegations (access to the poison, the wine bottle and the messages Scarlett left onWolfe’s voicemail). A similar range was presented for allegations against the other twocharacters, including two accounts of one character attempting to ‘frame’ another. It isclear that students were relying upon previous schema of detective/crime investigationnarratives within this activity.

After participants finished with the short prewriting activities, a short discussionensued about the experience. Most noted they did not like writing or writing papers;however, most agreed that they found MOGI an enjoyable experience for framing argu-mentation writing. The majority of participants speculated about whether a differentgame genre could make it ‘more interactive’. Five participants suggested it would beenhanced by having characters available, such as a caretaker who might help providericher backgrounds for the characters. At the end of the session, all of the participantsasked for the identity of ‘the culprit’. No answer was provided because, indeed, noneexisted outside of the learners’ experiences.

Negative samplingTwo participants spent the majority of time not participating in the mystery, but insteadfocused on deconstructing the environment. One chose to identify errors in the designwhile the other focused much energy on trying to pass through boundaries. Both were

MOGI: Impact of game narrative 465

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

gamers and expressed interest in the physical design of the environment. Both alsoexpressed more interest in genres such as action games, as opposed to adventure-stylegames. In informal discussions, they reported being critical consumers of games andapproached this environment as they would a game.

DiscussionThe scope of this qualitative case study is by no means comprehensive, but ratherintended to examine how the narrative in the game-based learning environment,MOGI, impacted the participants’ (1) intrinsic motivation, (2) curiosity, (3) plausibilityand (4) ability to manifest the experience into prewriting activities. The focus of thisinvestigation is on formative aspects of the design, rather than on a summative reportof the effectiveness of the game-based learning environment. The findings of this studyare not a prescription of the design of a game-based learning environment, nor do theyexplain the depth of intrinsic motivation, curiosity and plausible reasoning. The appli-cability of these findings for designers and practitioners can only be determined basedon the context for designing a game-based learning environment.

The findings of the investigation reveal that participants initially approached MOGI asa game. They looked for game mechanics to match their expectations, and when noneexisted, attempted to construct them. This has some implications in terms of howeducational games are perceived by students. While the idea of a ‘game’ mightbe intrinsically motivating to some students, existing schema of different game genresmay prove counterproductive to the types of values being fostered in a learningenvironment.

Although participants reported curiosity, some reported their curiosity was piqued bythe loose narrative, while others were intrigued by the environment. Berlyne (1960)asserts there are two types of curiosity: perceptual and epistemic. While perceptual isfostered by novelty, epistemic is fostered by the drive to answer an intriguing question.According to Berlyne, epistemic curiosity is only satiated when an acceptable answer ispresented. This investigation did not attempt to address which or to what degree thenarrative fostered either perceptual or epistemic curiosity. Although projective at best, itis likely both played a part as the experience was both novel, yet designed to piquecuriosity.

The findings of this investigation reveal that although the majority of participantsconstructed a plausible story from the narrative elements and were able to transfer theirexperiences into prewriting activities, unanticipated findings revealed how aspects ofthe environment design and narrative contributed to alternative narratives and unan-ticipated constructed narratives. Several participants in this study imposed relation-ships where none actually existed. This is somewhat consistent with Michotte’s (1963)findings in which subjects imposed narrative to describe action. Additionally, moreresearch needs to be conducted into narrative schema and how this might be leveragedfor learning.

466 British Journal of Educational Technology Vol 42 No 3 2011

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

While the findings of this investigation are informative for the formative design of thisgame-based learning environment, it is important to note that this investigation islimited, and further research should be conducted into learner perspectives of gamesand play for learning. Additionally, more research needs to be conducted about therelationship between narrative and both procedural and epistemic curiosity, along withcultural considerations in plausibility reasoning.

ConclusionWhat was interesting about this study is that it provided insight into how small ele-ments of narrative (evidence) evoked students’ existing narrative schemas. The storiesof ‘who done it’ were constructed by the students. There was no single narrative touncover, but based on students’ existing knowledge of mysteries, stories emerged.Equally of interest was the process in which these narratives were constructed, bothwith initial hypotheses and with how new evidence was accommodated.

Narrative environments such as those found in games and game-based learning envi-ronments provide researchers with ripe environments for gaining more insight intohow learners (and gamers) construct knowledge, both by evoking existing schema andby accommodating new knowledge. However, much more research needs to be con-ducted to uncover and provide greater insight into how the design of game-basedlearning environments can foster curiosity and intrinsic motivation as well as hownarrative environments (both realistic and fantasy) can maintain integrity and plausi-bility. Ultimately, the goal of any learning environment (game-based, classroomor informal) is the transference of knowledge into real-world settings, activities andsituations.

ReferencesAvedon, E. & Sutton-Smith, B. (1971). The study of games. New York: J. Wiley.Bailey, F. & Moar, M. (2001). Walking with avatars. Paper presented at CADE 2001 (Computers in

Art and Design Education), Glasgow School of Art, April 9–11. Glasgow, Scotland.Bailey, F. & Moar, M. (2002). The Vertex project: exploring the creative use of shared 3D virtual worlds

in the primary (K-12) classroom. Paper presented at SIGGRAPH 2002, San Antonio, TX. Pub-lished in ACM SIGGRAPH 2002 Conference Abstracts and Applications, pp. 52–54.

Barab, S. A., Hay, K. E., Barnett, M. G. & Squire, K. (2001). Constructing virtual worlds: tracingthe historical development of learner practices/understandings. Cognition and Instruction, 19,1, 47–94.

Barab, S. A., Thomas, M., Dodge, T., Carteaux, R. & Tuzun, H. (2005). Making learning fun: QuestAtlantis, a game without guns. Educational Technology Research and Development, 53, 1,86–107.

Bergeron, B. (2006). Developing serious games. Hingham, MA: Charles River Media.Berlyne, D. E. (1960). Conflict, arousal and curiosity. New York: McGraw Hill.Bers, M. (1999) Zora: a graphical multi-user environment to share stories about the self. In Proceed-

ings of Computer Support for Collaborative Learning (CSCL’99), Palo Alto, CA, pp. 33–40.Bers, M. & Cassell, J. (1999). Interactive storytelling systems for children: using technology to

explore language and identity. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 9, 2, 603–609.Bowman, R. F. (1982). A ‘Pac-Man’ theory of motivation: tactile implications for classroom

instruction. Educational Technology, 22, 9, 14–17.

MOGI: Impact of game narrative 467

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

Bruckman, A. (1997). MOOSE crossing: construction, community, and learning in a networkedvirtual world for kids. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute ofTechnology).

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Caillois, R. (2001). Man, play and games. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.Carson, D. (2000). Environmental storytelling: creating immersive 3D worlds using lessons

learned from the theme park industry. Gamasutra. Retrieved March 3, 2004, http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3186/environmental_storytelling_.php

Corbit, M. & DeVarco, B. (2000). SciCentr and BioLearn: Two 3-D implementations of CVEscience museums. In E. Churchill & M. Reddy (Eds), Proceedings of the third international confer-ence on collaborative virtual environments (pp. 65–71). New York: Association for ComputingMachinery.

Crawford, C. (2003). Chris Crawford on game design. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders Press.Dickey, M. D. (2005a). Three-dimensional virtual worlds and distance learning: two case studies

of Active Worlds as a medium for distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology,36, 3, 439–461.

Dickey, M. D. (2005b). Engaging by design: how engagement strategies in popular computer andvideo games can inform instructional design. Educational Technology Research and Development,53, 2, 67–83.

Dickey, M. D. (2006). Game design narrative for learning: appropriating adventure game designnarrative devices and techniques for the design of interactive learning environments. Educa-tional Technology Research and Development, 54, 3, 245–263.

Dickey, M. D. (2007). Game design and learning: a conjectural analysis of how massively multipleonline role-playing games (MMORPGs) foster intrinsic motivation. Educational TechnologyResearch and Development, 55, 3, 253–272.

Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Hand-book of research on teaching (3rd ed.) (pp. 119–161). New York: MacMillan Press.

Fine, M. (1994). Working the hyphens: reinventing self and others in qualitative research. In N.K. Denizen & Y. Lincoln (Eds), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 170–182.). Thousand Oaks,CA: Sage Publications.

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave.Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research.

New York: Aldine.Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.Jenkins, H. (2002). Game design as narrative architecture. Retrieved October 22, 2004, from http://

web.mit.edu/cms/People/henry3/games&narrative.htmlKetelhut, D. J., Dede, C., Clarke, J., Nelson, B. & Bowman, C. (2008). Studying situated learning in

a multi-user virtual environment. In E. Baker, J. Dickieson, W. Wulfeck & H. O’Neil (Eds),Assessment of problem solving using simulations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lincoln, Y. & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.Malone, T. W. (1981). Toward a theory of intrinsically motivating instruction. Cognitive Science,

4, 333–369.Michael, D. R. & Chen, S. (2005). Serious games: games that educate, train, and inform. Boston, MA:

Thomson Course Technology.Michotte, A. (1963). The perception of causality. New York: Basic Books.Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.).

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Mind Mapper Pro. SimTech Systems. Lewisville, TX. USA.Peshkin, A. (1988). In search of subjectivity—one’s own. Educational Researcher, 17, 7,

17–22.Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany: State University of

New York Press.Prensky, M. (2001). Digital game-based learning. New York: McGraw-Hill.

468 British Journal of Educational Technology Vol 42 No 3 2011

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.

Provenzo, E. F. (1991). Video kids: making sense of Nintendo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UniversityPress.

Rieber, L. P. (1996). Seriously considering play: designing interactive learning environmentsbased on the blending of microworlds, simulations, and games. Educational Technology Researchand Development, 44, 2, 43–58.

Robinson, J. A. & Hawpe, L. (1986). Narrative thinking as a heuristic process. In T. R. Sarbin (Ed.),Narrative psychology: the storied nature of human conduct (pp. 3–21). New York: Praeger.

Rollings, A. & Adams, E. (2003). On game design. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders Press.Salen, K. & Zimmerman, E. (2003). Rules of play: game design fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: The

MIT Press.Squire, K. (2003). Cultural framing of computer/video games. Game Studies: The International

Journal of Computer Game Research. Retrieved May 24, 2004, from http://www.gamestudies.org/0102/squire/

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: technique and procedures for developinggrounded theory (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Thomas, D. & Brown, J. S. (2007). The play of imagination: extending the literary mind. Gamesand Culture, 2, 2, 149–177.

Winn, W. D. (1993). A conceptual basis for educational applications of virtual reality (HITL Report No.R-93-9). Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Human Interface Technology Laboratory.

MOGI: Impact of game narrative 469

© 2010 The Author. British Journal of Educational Technology © 2010 Becta.