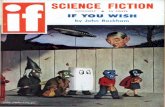

Minimalissimo: John Pawson and Modern Cistercian Architecture

Transcript of Minimalissimo: John Pawson and Modern Cistercian Architecture

Minimalissimo1: John Pawson and Modern Cistercian Architecture

Daniel L. Ledford

Yale Divinity SchoolProf. Karla Britton

1 This is a provocative term created by the online editorial platform, Minimalissimo, to describe extreme minimalism in art, architecture, fashion, andother mediums. It is used here as a deliberately loaded term to describe both the architecture of John Pawson and the Cistercians, while also touching on minimalism’s relationship with the arts industry of the 21st century. See Minimalissimo’s description of John Pawson’s Novy Dvur monastery here: http://minimalissimo.com/2010/09/novy-dvur-monastery-by-john-pawson/.

Ledford 2

Religion and Modern ArchitectureMay 8, 2014

At the onset of the modern movement in architecture, the

fashion industry played a major role in how architects approached

their designs. From Le Corbusier, who “identified color with

dress”2 and was influenced by the whitewashed surfaces of

Mediterranean architecture, to John Pawson, who spent several

years in Japan and was influenced by Cistercian abbeys, the

modern and modern revival movements have been intricately imbued

with aesthetic elements of fashion and minimalism. Finding

influence in the same structure, the Abbey of Le Thoronet, Le

Corbusier and Pawson have taken this “architecture of truth,

tranquility and strength” and blended its aesthetic principles of

light, simplicity, and functionalism in their own works of

contemporary sacred architecture.3 The long tradition of

2 Mark Wigley, White Walls, Designer Dresses: The Fashioning of Modern Archicture (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 314.

3 Le Corbusier, introduction to Architecture of Truth, Lucien Hervé (London: Phaidon, 2001), 7.

Ledford 3

Cistercian architecture, espoused by the architecture of Le

Thoronet, lends its aesthetic and formal principles to modern

Cistercian structures. For John Pawson, this is seen in his two

commissions for Cistercian abbeys: Novy Dvur and Sept-Fons. John

Pawson’s Cistercian structures reveal that extreme minimalist

architecture has created an inextricable bond between the

function and form of these sacred spaces.

A Brief History and Theology of Cistercian Architecture

In 1125, St. Bernard wrote his Apologia as a response to the

extravagant and grandiose features of the Benedictine abbey at

Cluny. In brief, St. Bernard asks, “What is gold doing in the

holy place?”4 St. Bernard was not averse to art, as many scholars

have interpreted. Rather, St. Bernard was speaking as an abbot of

a Cistercian monastery at Clairvaux, which was founded in 1115 as

a daughter house of Cîteaux and was already establishing its own

daughter houses by 1125.5 As an abbot of a Cistercian monastery,

which was different from its Benedictine ancestors in that a 4 St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Apologia (1125) quoted in Conrad Rudolph, The “Things of Greater Importance”: Bernard of Clairvaux’s Apologia and the Medieval Attitude Toward Art (Philadelphia: UPenn Press, 1990), 10.

5 Kristina Krüger, Monasteries and Monastic Orders (Salenstein, Switzerland: h.f.ullmann, 2010), 165.

Ledford 4

Cistercian abbey was generally more secluded, not connected to a

town, not a pilgrimage site, and not focused on the feeding of

the poor6, St. Bernard was speaking “from the two related and

basic elements of justification and function--claim and

reality.”7 Bernard believed that because of the above reasons,

which were central to the Cistercian Order, superfluous artworks

or embellishments were not needed or useful in the sanctuary.

This is in contrast to the copious inclusion of art and

embellishment by Abbot Suger at St.-Denis. St. Bernard wrote the

Apologia in 1125, which included the two chapters on the use of

art, and Abbot Suger wrote De Administratione in 1144-1145, which

included the expansion, embellishment, and dedications of St.-

Denis. Reading these two texts reveals the opposite opinion on

art in the sanctuary by both abbots. Erwin Panofsky claims:

Nothing, he [Suger] thought, would be a graver sin of omission than to withhold from the service of God and His saints what He had empowered nature to supply and man to perfect: vessels of gold or precious stone adorned with pearls and gems, golden candelabra and altar panels, sculpture and stained glass, mosaic and

6 Ibid., 169; Leroux-Dhuys, Cistercian Abbeys (Salenstein, Switzerland: h.f.ullmann, 1998), 46-48.

7 Conrad Rudolph, The “Things of Greater Importance,” 9.

Ledford 5

enamel work, lustrous vestments and tapestries.8

And although it is not explicit, Conrad Rudolph claims that Abbot

Suger was indirectly addressing St. Bernard’s Apologia in his De

Administratione.9 For the Cistercians, “No figural painting or

sculpture, except for wooden crucifixes, was tolerated; gems,

pearls, gold and silk were forbidden; the vestments had to be of

linen of fustian, the candlesticks and censers of iron; only the

chalices were permitted to be of silver or silver-gilt.”10

The strict observance of the Rule of St. Benedict is the

founding principle of Cistercian morality and this had to be

“translated into spatial terms.”11 The Cistercians did this by

“[eliminating] all ostentation and the superfluous, to choose

always the simplest solution, to strip bare as far as possible

any kind of artificial language of construction that was no more

than a concession to architectural fashion.”12 Thus, the 8 Erwin Panofsky, introduction to Abbot Suger on the Abbey church of St.-Denis and its Art Treasures (Princeton: Princeton U Press, 1946), 13.

9 Rudolph, The “Things of Greater of Importance,” 30-31.

10 Panofsky, introduction to Abbot Suger, 14.

11 Ibid. 25.

12 Ibid.

Ledford 6

architecture of the Cistercians in the 12th century was simple,

functional, and permanent. Meredith P. Lillich claims that

Cistercian architecture, as outlined by the plan of St. Bernard,

was not about the minimalist aesthetic first, but about ratios

and orthogonal function (Fig. 1). She notes, “But the emphasis is

on the permanence--I should prefer to say, the adequacy--of the

materials. The buildings are not grandiose but they are never

jerry-built and their functionalism expands our usual

understanding of that term.”13 This permanence of stone

structures of ideal proportions explains the functional aesthetic

of 12th century Cistercian architecture.

After the Bernardine period and the 12th century, Cistercian

architecture does not adhere to the strict building rules of St.

Bernard. During the prohibitions on art in the 12th century,

architectural features were the artistic expressions for

Cistercian abbeys. After the 12th century, regulations on art

decoration and visual enhancements in abbeys were relaxed and

13 Meredith P. Lillich, foreword (“The Common Thread”) to Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture, vol. 1, ed. Meredith P. Lillich (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1982), xi.

Ledford 7

almost non-existent after the end of the 13th century.14 This

does not mean that Cistercian architecture lost its essence.

Meredith Lillich claims:

After the Bernardine period Cistercian art changes in several chartable ways. It transforms the concept of ‘sufficient materials’ (that is, material sufficient unto the use thereof) into rather easier-to-apply aesthetic dictum of simplicity and puritanism of approach; and it softens the rigidity of, though it does not abandon, the early symbolic ratios.15

In the post-Bernardine period, Cistercian architecture

changes along with the periods of architectural history

(Romanesque, Gothic, Baroque, etc.), but in each case, remnants

of the plan of St. Bernardine plan can be found and the essence

of Cistercian architecture remains the same. Because of this,

Jean-François Leroux-Dhuys claims that Cistercian architecture

carries two inherent qualities, “freedom in architecture” and

“functional architecture,” which make Cistercian architectural

forms useful in modernity, i.e. the architecture of Le

Corbusier.16 On Le Corbusier’s design of the La Tourette

14 Krüger, Monasteries and Monastic Orders, 179-180.

15 Lillich, foreword to Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture, xiii.

16 Ibid., 116-117.

Ledford 8

monastery, Leroux-Dhuys claims, “This continuation of the image

of the Cistercian abbey, a symbol of extraordinary human

adventure, reveals the unchanging cultural posterity of the

Cistercians and that of the abbeys that they set up throughout

Europe.”17 Furthermore, the founding symbolic ratios of

Cistercian architecture are found in the works of Le Corbusier

and John Pawson as features of modernism and minimalism, such as

the use of ‘pure white,’ straight lines, and right angles.

Le Thoronet: From Le Corbusier to John Pawson

It is a striking coincidence that both Le Corbusier and John

Pawson were led to Le Thoronet by the suggestion of another

person. Before designing the monastery at La Tourette, Le

Corbusier visited Le Thoronet upon the suggestion of Marie-Alain

Cotourier. John Pawson visited Le Thoronet upon the suggestion of

the author Bruce Chatwin. In both cases, Le Corbusier and

Pawson’s architectural outlook was heavily influenced by the

forms extant in the Abbey of Le Thoronet. Furthermore, a great

corpus of religious buildings resulted from both architects’

visits to Le Thoronet. But what is each architect extracting from17 Ibid., 137.

Ledford 9

Le Thoronet?

For Le Corbusier, permanence of the stone and the effects of

light and shadow in the abbey were key in his design of the

monastery at La Tourette.18 John Pawson was similarly influenced

by the play of light and shadow in the abbey, even creating an

installation at the abbey in 2006 entitled Leçons du Thoronet. This

installation was, in essence, a look at the the Abbey of Le

Thoronet through the curatorial eyes of John Pawson. Setting up

fourteen benches to frame iconic views of the abbey, the

installation focused on fourteen ‘core themes,’ not in the

‘details’ of the abbey, but of ‘the bigger truths of

architecture’ found in the abbey.19 The fourteen themes were

context, mass, junction, surface, repetition, rhythm, geometry,

vista, scale, and proportion. In thinking about John Pawson’s

design of the Abbey of Our Lady of Novy Dvur in Bohemia, we can

see several of these fourteen themes from Le Thoronet as being

present at Novy Dvur.

John Pawson and Cistercian Architecture: Case Studies

18 Karla Britton, “Sacred Modern Architecture and the Abbey of Le Thoronet,” A+U 4 (2008): 32.

19 Alison Morris, John Pawson: Plain Space (London: Phaidon, 2010), 191.

Ledford 10

The message of the nascent Cistercian Order was thelove of

solitude, simplicity, poverty, and asceticism. Eloquentmasters

of words, as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, have enrichedus with

the experiences of the monk’s work, prayer, andmeditation. But

the immediacy of Cistercian art remains indispensablefor the full

appreciation of what activated the minds and hearts ofthose who

built Fontenay…20

Abbey of Our Lady of Nový Dvůr (Fig. 5)

This abbey is a daughter house of the Abbey of Sept-Fons,

thus its lineage can be easily traced back to the first

Cistercian abbey at Cîteaux.21 Built on a 247-acre estate in

Touzim, Czech Republic, the abbey church and adjoining corridors

were designed by John Pawson, and the restoration of the baroque

manor and outlying buildings was completed by the Czech Atelier

Soukup. John Pawson was commissioned to complete the design for

the abbey when the abbot of Sept-Fons saw photographs of Pawson’s

20 Louis J. Lekai, O.Cist., preface to Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture, vol. 1,ed. Meredith P. Lillich (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1982), x.

21 Cîteaux (1098) → Clairvaux (1115) → Fontenay (1119) → Sept-Fons (1132) → Novy Dvur (2002).

Ledford 11

Calvin Klein store in New York City. Pawson claims that the monks

saw a photo of the Calvin Klein store from the second floor,

looking down into the first floor where two tables looked like

they could be altars.22

The three wings and the abbey church create a 60,000 square-

foot site plan with a central cloister. Because of the sloping

topography of the site and the harsh Czech winters, the cloister

is not on the ground level and is enclosed with large glass

panels. In plan, the cloister of the western wing of the abbey

does not follow the interior wall of the structure because it

houses rooms that look out into the cloister garden and also

gives ground level access to the garden. The primary materials

used were white plaster, concrete, wood, and glass. The abbey can

house up to 34 monks and contains all the rooms that are

essential to sustaining a monastery, such as a refectory,

scriptorium, church, and dormitory. The church measures 47.1 x

10.5 x 13.6 meters (154.5 x 34.5 x 44.6 feet), which is a very

long and tall structure to connect the “square plan” and enclose

22 Matt Tyrnauer, “O Brother, Where Art Thou?,” Vanity Fair, August 2006, http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2006/08/minimalist-monastery-200608.

Ledford 12

the cloister (Fig. 6).

The cantilevered barrel vaults used in the structure, most

notably in the cloister corridor, recall the barrel vaults of the

Cistercian Abbey of Le Thoronet.23 Before designing the

monastery, Pawson was invited to Sept-Fons in Burgundy to live

for a few days and take in the daily life of the monks.24 When

asked about the minimalist features of the Novy Dvur (meaning

“New Yard”) monastery, he responded, “An absence of visual and

functional distraction supports the goal of monastic life:

concentration on God.”25 The description of the project on the

architect’s website claims, “The design draws on St. Bernard of

Clairvaux’s twelfth-century blueprint for Cistercian

architecture, with its emphasis on light, simplicity of

proportion and clarity of space.”26

23 Rudolf Stegers, Sacred Buildings: A Design Manual (Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag AG, 2008), 187.

24 Rob Gregory, Key Contemporary Buildings: Plans, Sections, and Elevations (New York: Norton, 2008), 148.

25 Joann Gonchar, “Monastery of Our Lady of Novy Dvur,” Architectural Record, September 2007, http://archrecord.construction.com/projects/interiors/archives/07_Monastery/.

26 “Abbey of Our Lady of Novy Dvur,” John Pawson: Works, accessed March 22, 2014,http://www.johnpawson.com/works/abbey-of-our-lady-of-novy-dvur/.

Ledford 13

In the Novy Dvur abbey, minimalist architect was matched

with a minimalist-minded clientele. This example of modern

Cistercian architecture seamlessly connects St. Bernard’s plan of

the 12th century with the minimalist contemporary design of the

21st century, to which Phaidon Atlas notes, “This twenty-first

century monastery seems an effortlessly respectful manifestation

of medieval values.”27

Abbey of Our Lady of Sept-Fons

After the first phase of construction was complete and the

abbey church at Novy Dvur was consecrated in 2004, the monks of

Sept-Fons commissioned Pawson to update and consolidate the 18th-

20th century buildings at Sept-Fons. The large expanse of these

buildings did not lend to the functionality of the monastery for

everyday use. Therefore, Pawson was invited to build new

structures while also renovated and redesigning the layout of

existing structures to improve the functionality of the site.

One of the main redesigns of the site involves the church,

sacristy, and chapels of the cloister (Fig. 7). In this instance,

27 “Abbey of Our Lady of Nový Dvůr,” Phaidon Atlas, accessed February 20, 2014,

http://phaidonatlas.com/building/abbey-our-lady-novy-dvur/1043.

Ledford 14

a cloister was not necessary for the plan because only three

wings existed; in fact, the cloister created an unnecessary

circulation space that disjoined the wings of the church and

other buildings. Pawson decided to create one corridor on the

interior of the central wing that would connect the sacristy,

side chapels, and the other two wings from one central space

(Fig. 8). This was also more functional because it allowed an

entry point for the public when entering the church from the

courtyard. Upon entering from the courtyard, the visitors find

themselves in an austere space with only a central plinth and

stoup, with a linear sliver of light leading them to the central

corridor and further into the church.28 It is in this Cistercian

work by John Pawson that the functionality of the space

superseded tradition, thus allowing its new ‘lateral’ form to

reinforce its function.

In this second example of John Pawson’s minimalist design

for Cistercian sacred spaces, we see an alternative approach at

minimalism: reduction. At Novy Dvur, Pawson was able to design

from the ground up since a church did not exist on the grounds,

28 Morris, Plain Space, 98-107.

Ledford 15

whereas at Sept-Fons, Pawson was presented with the challenge of

structurally reorganizing an established community and their

habits of movement. However, Alison Morris claims that this is an

alternate way to look at architecture and minimalism: “…the

unfolding narrative of revelation through reduction might be seen

to uncover wider truths about architecture of this type – about

what it is that you make space for, when you embark on the

process of clearing away.”29

The Case for Form and Function: Fashion, Modernity, and Minimalism

What is left of built work, a sort ofinevitable and insuppressible limit,also of an ontological nature, has thesole purpose of exalting the miracle ofexistence, nature, objects, and phenomena.30

In the 1995 monograph White Walls, Designer Dresses: The Fashioning of

Modern Architecture, Mark Wigley attempts to place the emergence of

the modern architectural era and the fashion industry in a single

scope. What interests us most here is the discussion of

‘whitewash’ as it pertains to Le Corbusier and to John Pawson’s

29 Ibid., 74.

30 Franco Bertoni, Minimalist Architecture, trans. Lucinda Byatt (Basel: Birkhäuser,2002), 58.

Ledford 16

minimalist Cistercian architecture. Going against Le Corbusier’s

idea of architectural “dress,” Wigley claims, “No matter how many

surfaces of particular buildings are white, and how many appear

to faithfully exhibit the materials of construction, the fragile

coat of white that dissimulates its material prop continues to

act as the device for exposing which materials are covered and

which are not.”31 Wigley argues that the idea of architectural

‘dress’ of modern architecture cannot be upheld since it goes

against the forms of ‘modern technology’ and ‘functional

rationalization.’ What is important from Wigley’s book is the

connection of Le Corbusier and this language of fashion: “For Le

Corbusier, it is not the fit that counts but the space defined by

the shape of the clothing.”32 Le Corbusier rejected fashion, as

did many other architects of the modern period, but Le Corbusier

still espoused a ‘fashionable’ theory – that design is the

essence of architecture.

As we have seen above, John Pawson’s built Cistercian

structures are owed in part to Calvin Klein, a premier minimalist31 Wigley, White Walls, 362.

32 Ibid., 316.

Ledford 17

fashion designer. It was the Calvin Klein store on Madison Avenue

in New York City that the monks at Sept-Fons discovered through

Pawson’s book, Minimum, resulting in their decision to

commission him for designing Novy Dvur, and later the renovation

of Sept-Fons. The Calvin Klein store resembles an art gallery

because it is meant to showcase the design ideologies of Calvin

Klein, not to act solely as a retail store (Fig. 9). The store

was designed so that “…the visitor is invited to stroll through a

space in which personal ideas about elegance and luxury are

expressed.”33 So, John Pawson’s design for the Calvin Klein store

was more of a museum-type than simply a retail store, even though

this design cannot be fully separated from the issues of

architecture of retail and capitalism. Furthermore, John Pawson

designed an apartment for Calvin Klein and worked closely with

him on the New York High Line pavilion, so these connections are

not superfluous.

Just like the work of Le Corbusier, John Pawson’s work as a

whole, including his Cistercian buildings, has been scrutinized

and related to the fashion industry. For Pawson, this is more of

33 Francisco Asensio Cerver, Architecture of Minimalism (New York: Arco, 1997), 170.

Ledford 18

a direct relation because he has designed spaces for fashion and

for the fashionable elite; however, we must not let this view of

Pawson’s minimalist architecture define the essence of his

architecture. The design, according to Le Corbusier, is the

essence of architecture, and for Pawson, the design of his

Cistercian buildings might espouse a ‘fashionable’ form but its

formal relationship to its function inextricably ties these two

elements of his architecture together. To better understand this

relationship, let us look at an example by Luis Barragan.

Barragan designed a white wall as a component of the Drinking

Trough Fountain in Las Arboledas (Fig. 10). The form of the wall

is simple – a plain white surface. The function of the wall is

also simple, yet metaphysically complex – a screen to display the

changing light and shadows of the surrounding trees.34 This

simple white wall by Barragan has simple formal qualities but

functions as a deeper understanding of the locus – a reflection

of the non-manmade landscape.

We find a similar form-function relationship in John

Pawson’s Cistercian buildings. The cloister at Novy Dvur is the

34 Bertoni, Minimalist Architecture, 31-32.

Ledford 19

clearest example. The cloister carries an inherent history and

tradition that includes not only Cistercian architecture as a

whole, but also Le Thoronet’s barrel vaults. Furthermore, the

cloister design at Novy Dvur resists the criticisms of breaking

tradition in its enclosed, glass form because of practical and

functional concerns – weather and topography. Yet, in the design,

Pawson takes the liberty to introduce a metaphysical quality in

the cloister like Barragan does in Las Arboledas. Influenced by

the minimalist light installations of James Turrell, the end of

the corridors at Novy Dvur recall a Turrell-like deceptive

quality (Fig. 11). This is due to the ‘whitewashed’ walls, the

barrel vault, and the natural and manipulated light sources,

common qualities of Pawson’s minimalist design. The result is an

inextricable relationship between form and function. The cloister

form is necessary for the monastery and the ambulation of its

monks, and it functions as such, but the architectural detail in

design by Pawson raises the symbolism of light and space. This

follows the necessary unorthodox form of an enclosed cloister,

thus realizing that form and function are necessary benefactors

of each other in this case and throughout the design of the

Ledford 20

monastery.

The minimalist design of John Pawson and other architects of

minimalism regularly include spaces like Barragan’s ‘white wall.’

These are spaces that have been stripped to their bare minimum

and allow for reflection. What is reflected in each case is

different, but for Pawson’s Cistercian buildings, we can estimate

the reflections going on in these spaces. For in minimalist

architecture, “Physicality and spirituality, concreteness and

abstraction blend in minimal simplicity through the acquisition

of few, elemental, basic principles that, before being translated

into stone, were assimilated through an emotional, philosophical,

or religious route.”35 For the Cistercians, this minimalism was

established in stone in the 12th century and has been continued

today in the works of John Pawson. An anecdote from Pawson

concerning the design of Novy Dvur is relevant here: “I tried to

hide the cemetery at first, but when the monks noticed that, they

were unhappy and asked to have it put where they could see it

from the cloister. For them, that is the best part: they get to

35 Ibid., 58.

Ledford 21

go to heaven.”36

The theological functions of these Cistercian sacred spaces

have been included into the design of the space itself. Similarly

at Sept-Fons, the entrance room from the courtyard subtly guides

the visitor from a transitory space into the heart of the

building, the ‘lateral’ corridor leading into the church. In both

reduction, renovation, addition, and complete construction,

minimalist architecture has proved successful for both of these

Cistercian communities. This was not easy, as Pawson has said in

interviews. He had to change many things, like the cemetery view

above, to follow the theological functions of the space, but this

does not necessarily conclude that form follows function. In

these Cistercian abbeys, form and function are both ingrained

with theological and sacred details, working together in one

common space to house monks and allow for interaction with the

divine on a daily, routine basis, whether in the cloister,

refectory, scriptorium, or sanctuary.

Conclusion

36 Tyrnauer, “O Brother, Where Art Thou?,” http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2006/08/minimalist-monastery-200608.

Ledford 22

Set up by St. Bernard in the 12th century, the schema for

building Cistercian monasteries has evolved and been reformed by

the modern era. However, the changes to typical Cistercian

architectural norms are for practical reasons, whether

manipulating form for function or function for form. As we have

seen, the Cistercian buildings of John Pawson have been designed

in the minimalist style, resulting partly from his influential

visits and installation at Le Thoronet. From Pawson’s much

publicized relationship to commercialism and Calvin Klein we were

able to extract the meaning of such a relationship as it relates

to Novy Dvur and Sept Fons through the work of Mark Wigley and

‘fashionable’ modernism; however, it was Le Corbusier’s opinion

that design is the essence of architecture that led us to analyze

the form-function relationship in the cloister at Novy Dvur and

to argue for their inextricability. Thus, through Barragan’s

‘white wall’ we are able to reflect on minimalissimo and

contemporary sacred architecture.

Ledford 23

Bibliography

Bertoni, Franco. Minimalist Architecture. Translated by Lucinda Byatt.Basel: Birkhäuser, 2002.

Britton, Karla. “Sacred Modern Architecture and the Abbey of Le Thoronet.” A+U 4 (2008): 31

36.

Cerver, Francisco Asensio. Architecture of Minimalism. New York: Arco, 1997.

Gonchar, Joann. “Monastery of Our Lady of Novy Dvur.” Architectural Record. September 2007.

Ledford 24

http://archrecord.construction.com/projects/interiors/archives/07_Monastery/.

Gregory, Rob. Key Contemporary Buildings: Plans, Sections, and Elevations. New York: Norton,

2008.

Krüger, Kristina. Monasteries and Monastic Orders. Salenstein, Switzerland: h.f.ullmann, 2010.

Le Corbusier. Introduction to Architecture of Truth, Lucien Hervé. London: Phaidon, 2001.

Lekai, Louis J., O.Cist. Preface to Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture, Volume 1, Edited

by Meredith P. Lillich. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1982.

Leroux-Dhuys, Jean-François. Cistercian Abbeys: History and Architecture. Salenstein,

Switzerland: h.f.ullmann, 1998.

Lillich, Meredith P. Foreword (“The Common Thread”) to Studies in Cistercian Art and

Architecture, Volume 1, Edited by Meredith P. Lillich. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1982.

Morris, Alison. John Pawson: Plain Space. London: Phaidon, 2010.

Panofsky, Erwin. Introduction to Abbot Suger on the Abbey church of St.-Denis and its Art

Treasures, Edited by Erwin Panofsky. Princeton: Princeton U Press, 1946.

Pawson, John. Afterword to Architecture of Truth, Lucien Hervé. London: Phaidon, 2001.

Rudolph, Conrad. The “Things of Greater Importance”: Bernard of Clairvaux’s Apologia and

Ledford 25

the Medieval Attitude Toward Art. Philadelphia: UPenn Press, 1990.

Stegers, Rudolf. Sacred Buildings: A Design Manual. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag AG, 2008.

Stiegman, Emero. “Saint Bernard: The Aesthetics of Authenticity.”In Studies in Cistercian Art

and Architecture, Volume 2, Edited by Meredith P. Lillich. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1984.

Tyrnauer, Matt. “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” Vanity Fair. August 2006.

http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2006/08/minimalist-monastery-200608.

Wigley, Mark. White Walls, Designer Dresses: The Fashioning of Modern Archicture.

Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995.

-------“Abbey of Our Lady of Novy Dvur.” John Pawson: Works. Accessed March 22, 2014.

http://www.johnpawson.com/works/abbey-of-our-lady-of-novy-dvur/.

-------“Abbey of Our Lady of Nový Dvůr.” Phaidon Atlas. Accessed February 20, 2014.

http://phaidonatlas.com/building/abbey-our-lady-novy-dvur/1043.