The Gothic Tradition in "Supernatural": Essays on the Television Series

“Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Supernatural: A Taxonomy of Zwischenwesen.” Archiv für...

Transcript of “Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Supernatural: A Taxonomy of Zwischenwesen.” Archiv für...

Karen Sonik

Mesopotamian Conceptions of theSupernatural: A Taxonomy of Zwischenwesen*

Abstract: The monsters and daimons (demons) of Mesopotamia belonged to a con-stellation of Zwischenwesen – interstitial beings with supernatural qualities or ca-pacities – that occupied the space between humans and their gods. As the“Other,” if not always the enemy, their alterity was not only inscribed in their bodiesbut also reflected in their social alienation and geographical isolation. Strikingly im-agined,where depicted or described, as morphologically anomalous or miscegenated(Mischwesen), the monsters and daimons lacked the kinship affiliations of both city-dwelling humans and their gods and properly dwelt at the wild and inhospitablemargins of the known world. This study explores their definition, functioning, andclassification in a cosmos in which the overarching conflict was between orderand chaos rather than good and evil, in which divinely organized and guarded civ-ilization was ever threatened by the pressing and savage forces gathered in the wil-derness beyond the city walls.

In the gulf between humans and their gods exists an “other” world, an extraordinarysupernatural landscape populated by all manner of “in-between” beings or Zwi-schenwesen. While alike in their transgressing of those borders and boundariesthat delineate civilized human and divine lives and behaviors (as well as in their su-pernatural origins, qualities, or abilities), Zwischenwesen may be divided into anarray of sub-groups that fulfill a range of (sometimes overlapping) cultural and reli-gious roles.¹

In ancient Mesopotamia, a number of native terms for distinct types of Zwischen-wesen are apparent in the extant textual corpora, so that gidim / eṭemmu (Sumerian /

* Portions of this research were presented at the Center for the Study of Religion at the University ofCalifornia, Los Angeles, and at a conference on Mesopotamian and Egyptian Demonology at theInstitute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University. Thanks are due to a New FacultyFellows award from the American Council of Learned Societies, funded by The Andrew W. MellonFoundation, which allowed the completion of this work. All Sumerian is in small capitals, Akkadianin italics. The term Zwischenwesen is defined as inclusive of ghosts, demons, angels, devils, nymphs, heroes,gnomes and other such figures that cannot be defined as either humans or gods, see Lang 2001, 414–15. For the discussion of similarly interstitial figures in the context of more familiar Renaissancedemonology, see Febvre 1982, 446–450: “Deus quidem homini non miscetur, sed per id medium,commercium omne atque colloquium inter Deos hominesque conficitur, et vigilantibus nobis atquedormientibus,” translated in n. 55: “Indeed God does not mingle with man, but it is through thismedium [angels, demons, heroes, etc.] that all intercourse and conversation between Gods and menis accomplished, when we are awake as well as when we are asleep.”

10.1515/arege-2012-0007 Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

Sonik, Karen. “Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Supernatural: A Taxonomy of Zwischenwesen.” Archiv für Religionsgeschichte 14 (2013): 103-116.

Akkadian) identified spirits of dead humans or ghosts, mašmaš / kaššāp(t)u referredto a sorcerer or sorceress, nun.me or abgal / apkallu identified the mythologicalsages, and sukkal / sukkallu identified the divine viziers, gods proper that neverthe-less evinced an interstitial nature in their service as messengers, capable of navigat-ing in this capacity those borders and boundaries between realms that were impass-able even to the great gods. Subsumed under the broader category of Zwischenwesenthere existed also, however, a number of other interstitial beings that, despite theiralienation from the ranks of both gods and humans and their possession of distinctsupernatural powers or abilities, are not so easily encapsulated or defined using thenative Sumerian or Akkadian terminology. Here discussed under the rubric of mon-sters and daimons, divided and defined by the types of “cultural work” they perform,these lattermost Zwischenwesen comprise the primary focus of this work. What istheir role in the Mesopotamian cosmos? And how are the terms monster and daimon,in the absence of equivalent native terminology, properly defined and mapped ontoMesopotamia’s supernatural landscape as it is delineated in the various extant visualand textual sources?

The Sumerian and Akkadian TerminologyIf no definitively equivalent terms exist for monster or daimon in either Sumerian or Ak-kadian, the Sumerian term ursag̃may in some periods and textual genres be associatedwith the former type of being and a range of Sumerian and Akkadian terms, maškimand rābiṣu, udug and utukku, galla and gallû among them, with the latter.

The Sumerian mythological narratives in particular are teeming with figures ge-nerically described by modern scholars as monsters or daimons – or, more frequent-ly, demons. Distinct in appearance or physical composition but united in commonpurpose as frequent challengers, servants, or defeated enemies of the gods, variousof these figures might be attributed with individual names (such as Anzud, Gypsum,Strong Copper, or Bison). Of especial interest here, however, are those terms appliedto these figures when they are grouped together as a collective. Key amongst theseterms – and applied especially to those monstrous enemies defeated by the hero-god Ninurta in the Sumerian compositions Lugale and Angim – is ursag̃, “hero orwarrior” (and particularly ur-sag̃-ug₅-ga, referring to these figures in their defeat as“slain heroes”).² This term, notably, is also specifically applied in one passage of Lu-gale to a single of the larger (eleven member) collective, the Six-Headed Ram:

Ninurta, let the names of your slain heroes be invoked!Kulianna, the Dragon, GypsumStrong Copper, the hero Six-Headed Wild Ram,Magilum, Lord Samananna

For a discussion of the Slain Heroes specifically, see Black 1988.

104 Karen Sonik

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

The Bison, King Date Palm,Anzud, the Seven-Headed Serpent ––Ninurta, you indeed have slain (them) in the mountains³

What is perhaps most remarkable about the application of the term ursag̃ in thesecontexts is not simply its non-pejorative, even potentially complimentary, connotations(translating as “hero” or “warrior”) but that it is applied as well to Ninurta, the heroicchampion of the gods against the monsters, as it is to the monsters themselves. Thisshared appellation suggests the common martial aspect of both the deity and his mon-strous opponents, underscoring the remarkable nature of Ninurta’s accomplishment indefeating so lofty a set of enemies. The status of the monsters is likewise reiterated inAngim, in which Ninurta returns to Nippur with his monster trophies and identifies hisbeaten enemies not only as his “captured heroes” but also, strikingly, as his “capturedkings.”⁴ It is in Angim also that another means of referencing a monstrous collective isemployed the entire group of the disparate monsters defeated by Ninurta is jointly des-ignated the “captive wild bulls” and “captive wild cows” (Angim 102–103), terms thatare used in the same text to specifically identify two of the eleven monsters in the col-lective.

Unfortunately, while these referential strategies and collective identificationsoffer some insight into how the individual monstrous figures to which they refermight have been perceived, they neither find clear correlates in the Akkadian literarytexts nor are specific enough to the monsters alone to be used as classificatory terms.They thus serve more to reiterate the absence of any single Sumerian or Akkadianterm defining the monsters as a distinct category than to delineate any particularsub-classification of Zwischenwesen.

Similar strategies to those used for identifying monstrous collectives are em-ployed in referencing those entities typically defined in English as daimons (or, fre-quently, demons). The genericization of terms specifically identifying individual dai-mons (or subclasses of daimons) is particularly evident in the usage of maškim andrābiṣu, udug or utukku, ala or alû, and galla or gallû, all of which terms appear inincantations against specific daimonic forces or influences: “Be adjured by Ningirsu,lord of the weapon. / Harmful utukku, harmful alû, harmful ghost, harmful gallû,harmful god, and harmful rabiṣu / may harmful ones not approach my body.”⁵

The generic usage of these specific terms is evident in several mythological andnarrative texts, among these the Standard Babylonian Cuthaean Legend and the Bab-ylonian Enūma eliš. In the former text, for example, the besieged legendary kingNaram-Sin despatches a scout with instructions to prick the terrifying enemy

Lugale ll. 128– 134; translation (adapted) from Cooper 1978, 144– 145, and Jacobsen 1987, 242–243. Angim ll. 158–159, see Cooper 1978, 86–87. Utukkū Lemnūtu III ll. 71–73, translation (modified) from Geller 2007, 199. While the maškim andrābiṣu are generally equated, Geller has argued for certain “culturally specific differences” betweenthe Sumerian and the Akkadian entities.

Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Supernatural 105

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

horde and see if they bleed, a test that will define his terrible opponents either asmortals that might be faced and overcome or as true supernatural challengersthat, presumably, don’t have blood in the manner of ordinary human beings:[šumma dāmū la uṣû]ni šēdū namtarū / [utuk]kū rābiṣū lemnūte šipir Enlil šunu, “[Ifblood does not come out], they are (evil) spirits, messengers of Death, / “[fie]nds, ma-levolent demons, creatures of Enlil.”⁶ In this particular case, it is not only utukku,translated by Westenholz as “fiends,” but also rābiṣu, given as “malevolent de-mons,” that functions generically. A similar appropriation and genericization of aterm denoting a specific type or class of daimon occurs in Enūma eliš Tablet IV. Tiā-mat’s monstrous progeny,while differing starkly in both function and sphere of agen-cy from the daimonic gallû, are nevertheless collectively identified here as gallû(translated by Lambert as “devils”): ù is-tin-eš-ret nab-né-ti šu-ut pul-ha-ti za-ʾi-nu /mi-il-la gal-le-e a-li-ku ka-lu im-ni-šá, “The eleven creatures who were laden with fear-fulness, / The throng of devils who went as grooms at her right hand.”⁷

The generic usage of these specific terms in such contexts, as well as their group-ing into collectives in a range of textual genres (including the incantations andmythological narratives), simultaneously demonstrates the native recognition of acertain commonality between the various types of interstitial entity that inhabitedthe Mesopotamian supernatural landscape and underscores the taxonomic gapthat hampers modern attempts to analyze these figures in any close detail or acrossthe various visual and textual corpora in which they appear.

The paucity of native Sumerian or Akkadian terms for the types of “in-between”entity with which this discussion is concerned, means that a single interstitial figuremight, in the modern scholarship, be diversely described as a Mischwesen, a mon-ster, a demon, a genius, or with any one of a similar series of terms depending oncontext and individual preference – and in the absence of any clear discussion ofhow these terms are to be defined. The taxonomic model developed below, in map-ping the terms monster and daimon onto the Mesopotamian supernatural landscape,is not intended to create hard and fast divisions that were likely ever recognized orarticulated in so concrete a form by the inhabitants of Mesopotamia themselves;rather, it is meant to reflect inherent (if only implicit) similarities and differences– evident in both the visual and textual sources – between the numerous and variedtypes of Zwischenwesen.

Standard Babylonian Cuthaean Legend ll. 67–68; translation from Westenholz 1997, 314–315. Bloodis presumably to be understood in this context as signifying human unity, its absence a clear sign of“Other”-ness. Enūma eliš IV ll. 115– 116, transliteration from Talon 2001, 55; translated in Lambert 2008, 47.

106 Karen Sonik

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

Delineating Mesopotamian Monsters

Monsters (Latin monstrum, “omen,” from the root monere, “to warn”) were often readas signs from the gods in the ancient world, constantly on the lookout as it was forsigns and symbols through which the will of the gods might be divined. An earlier ifnow discounted etymology derived monster not from monere but from monstrare, “toshow,” underscoring the role of the monster as potential revelation, visually encod-ing the will of the gods.⁸

Unreal monsters, as natural monstrosities, are frequently immediately recogniz-able, their bodies (typically) diverging significantly from the norm in their miscege-nation, their remarkable size, or in distortions or anomalies in specific of their fea-tures. The tendency to characterize all Mesopotamian monsters (and all daimonsas well, for that matter) as Mischwesen, “mixed beings,” is, then, an inapt one asit is less hybridity than general anomaly that is the physical determinant of mon-strosity and that functions as the outward manifestation of the chaotic forces andfeatures, dangerous to civilized life, that the monsters embody.⁹

Beyond physical form, the monsters of Mesopotamia, as the monsters of otherspatiotemporal zones, are characterized by their geographical alienation, relegatedsometimes to the true and far distant wilderness but as often to the bare marginsof the ordered world where, though beyond its borders, they are yet capable of rec-ognizing, coveting, or being plagued by the noise and light and life of civilizationand of creation. In the Sumerian composition Lugale, for example, the monsterAzag is rendered particularly threatening by his imitation of the gods, first takingon the kingship of the mountains and the rebel lands and, swelling with power, ul-timately seeking to usurp the authority and rulership of the great gods of Mesopota-mia itself. In the Akkadian Anzû Epic, the monstrous and mountain born Anzud isadopted into the civilized divine realm as a servant of great god Enlil but, as subse-quent events make clear, never fully integrated into its order. Perpetually in the com-pany of the king of the gods, the monster begins with coveting Enlil’s authority andends by stealing the great god’s Tablet of Destinies, fleeing with this emblem of di-vine rulership back into the chaotic mountains where he is properly at home.You cantake the monster out of chaos, but you cannot take the chaos out of the monster.¹⁰

The interstitial and “in-between” nature of the monsters, then, is reflected notonly in their anomalous and striking physical forms but also in their habitats, sothat they occupy in both respects the spaces between conceptual and cognitive cat-egories, and find their proper homes in those precarious and mutable zones wherethe ordered world confronts the chaotic one.

See Huet 1993, 6. In the context of Mesopotamia, this observation is particularly important when discussing po-tentially anthropomorphic monsters such as Huwawa or the lahmu, as well as animate but seeminglyinorganic figures such as Strong Copper. On the Tablet of Destinies, see further Sonik 2012.

Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Supernatural 107

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

In addition to their physical and geographical alienation, the monsters of Mesopo-tamia (again in keeping with the monsters of other regions and periods),¹¹ are charac-teristically also social exiles, in kinship and in custom irrevocably sundered from civi-lized humans and their gods. The inhabitants of Mesopotamia defined the humanproper as one who participated fully in civilization and its conventions, establishingthose behaviors, customs, and possessions that distinguished the civilized man (orcivilized god) from his still savage or wild counterparts in narratives such as theEpic of Gilgameš and The Marriage of Martu. In the former compositions, as recordedin the Old Babylonian Pennsylvania Tablet as well as the Standard Babylonian Epic(Tablets I and II), the wild man Enkidu undergoes a multi-step process of initiationinto civilization from his original state of near-bestiality. Beginning this initiationwith his mating with the prostitute Šamhat, he goes on to learn to wear clothing, toconsume civilized comestibles (bread and beer), to protect domesticates against wildanimals, to enter the city of Uruk and accept Gilgameš as his king, and, in the StandardBabylonian version at least, he completes the process with his adoption by Gilgameš’mother Ninsun, so acquiring a kinship network of his very own.¹² The Sumerian com-position The Marriage of Martu similarly highlights those qualities that distinguish thecivilized man from the savage, as it reviews some of those characteristics and behav-iors that apparently separate the nomadic Amorites from proper city-bred human be-ings: “Lo, their [the Amorites’] hands are destructive, (their) features are (those) [ofmonkeys]…A tent-dweller, [buffeted] by wind and rain, [who offers no] prayer… Heeats uncooked meat, / In his lifetime has no house. / When he dies, he will not beburied.”¹³

True human beings in the context of ancient Mesopotamia, then, were defined notonly by their regular anthropomorphic forms but also by their habitation within andparticipation in the customs of the cities (these ordered and protected by the gods),and by their integration into networks of kinship and community. Similar conventionsdefined alike the gods of Mesopotamia, who frequently adopted an anthropomorphicform, inhabited the great temples in the cities of which they were patrons, and werelinked by ties of blood and marriage to the other great gods of the Mesopotamian pan-theon. In their physical alterity, their geographical exile, and their social alienation,

For the Anglo-Saxons, as for the inhabitants of Mesopotamia, monsters likewise stood outside ofphysical, geographical, and social boundaries, see Neville 2001, 117. George understands this adoption as aetiological, serving as precedent for the adoption of or-phans or foundlings by the temple of Uruk, see George 2003, 462. As the final step in Enkidu’s rite ofinitiation into the civilized world inhabited by Gilgameš, however, it is a significant act in its ownright, the possession of kinship networks being one of the key differences between humans (andgods) of the civilized world and the monsters and daimons of the margins. The Marriage of Martu ll. 127, 133, 136–138; translated in Klein 1997, 115– 116. The subject of the“Other” in Mesopotamia was penetratingly treated in earlier studies by Pongratz-Leisten 2001 andWiggermann 1996.

108 Karen Sonik

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

the monsters of Mesopotamia are thus at once established as “Other” and bound to-gether as a common group of outsiders.

Of Demons and DaimonsThe term demon is a pervasive one in modern scholarship on the Mesopotamian Zwi-schenwesen, and has frequently been used as if interchangeable or equivalent withthe term monster. In those cases where scholars have attempted to define the twoterms as signifying distinct categories of Zwischenwesen, the results have been prob-lematic at best. Edith Porada, for example, in her brief but influential introduction toa 1989 compilation of essays in her honor (Monsters and Demons in the Ancient andMedieval Worlds) noted the existence of an art historical convention according towhich “in descriptions of Mesopotamian art, creatures which seem to belong tothe animal world because they walk on all fours, are called monsters, whereasthose which walk on two legs with a human gait are called demons, a terminologynot necessarily used in the iconography of other regions.”¹⁴ While attempts have oc-casionally been made to extrapolate this division beyond strictly visual contexts, anydistinction based on physical form is, in light of the fact that many of the Mesopo-tamian Zwischenwesen were never depicted or described in any detail, at best im-practical and at worst reductionist, diminishing these figures – complex and multi-faceted cultural constructs in their own right – to the status of merely visual fancies.The following section, then, is dedicated to examining the term demon as distinctfrom monster and to considering the manner in which it might be productively map-ped onto the Mesopotamian supernatural landscape.

Carrying with it the weight of nearly two millennia of Christian connotations, ac-cording to which a demon both physically embodies and represents evil, “that whichis morally reprehensible, wicked, or sinful and leads to pain and suffering in theworld,”¹⁵ demon is something of a loaded term, as well as a culturally specificone. The associations it has accumulated through the centuries of its use in the West-ern world locate it, among other things, in opposition to legitimate divine rule, aproblematic association when the term is applied in non-Western contexts inwhich even harmful or destructive entities might act as legitimate divine agents.Given the ubiquity of the term demon in the scholarship treating the specific typesof Zwischenwesen considered here, however, simply dispensing with it is an imprac-tical proposition: monsters and demons inevitably march hand in hand. I would sug-gest instead, then, that the somewhat pejorative term demon be very narrowly delim-ited as a secondary category of interstitial entity rather than completely abandoned

Porada 1987, 1. Merriam-Webster 1999, s.v. Good and Evil. The task of clearly or consistently defining evil is, asmany scholars have observed, an extremely difficult – perhaps even impossible – one; see, forexample, Neiman 2002; Bennett et al. 2008, 21.

Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Supernatural 109

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

(discussed further below). As the partner term for monster, and taking the place ofdemon as a primary subcategory of Zwischenwesen, the comparatively neutral (atleast in Western contexts) Greek term daimon is far preferable, severed as it isfrom the pejorative moral connotations associated with demon.¹⁶

The meaning of daimon in ancient Greece contexts is perhaps as ambiguous, andas difficult to strictly delimit, as terms such as maškim or rābiṣu in Mesopotamiancontexts. While folk etymologies record its derivation from daiomai, “to distribute,”in reference to “the forces that dispensed fortunes to men,”¹⁷ the term occurs in arange of contexts in Homer’s Iliad, applied to gods – though it seems never to beused interchangeably with theoi – as well as to heroes – who might be characterizedas acting like daimons. Burkert concluded intriguingly that daimon might, then, bebest understood less as defining a specific class of supernatural being and moreas a particular mode of action: “Daimon is occult power, a force that drives man for-ward where no agent can be named…Daimon is the veiled countenance of divine ac-tivity.”¹⁸ Outside of Homer, the term takes on additional dimensions so that Hesiodallotted a particular place for common daimons, men of the Golden Age transformedinto invisible guardians of human beings, and so that Plato and Xenocrates influ-enced the better known conception of daimons as lowly supernatural entities of a pri-marily, if not exclusively, dangerous and threatening aspect.¹⁹

In attempting to locate daimons in the Mesopotamian cosmos, then, there are anumber of considerations to take into account. These considerations, significantly,offer potential entry points or insights into various nuances of the Mesopotamiandaimonic landscape, which appears to encompass as much Burkert’s “veiled counte-nance of divine activity” (a type of force rather than a distinct class of entity) as thedistinct malevolent (or benevolent) second-order supernatural figures of Plato orXenocrates. While some of these latter Mesopotamian daimons were endowed withrelatively well-developed features and functions, many others were neither individu-ally described nor delineated, some apparently acting at the behest of the gods andothers on personal whim or on the impetus of fundamental nature.

Within the primary category of daimon, adopted here as the partner term formonster in distinguishing the various classes of Mesopotamian Zwischenwesen, atleast two subgroups might be distinguished: those that were destructive or hostiletowards humans, here sub-classified as demons,²⁰ and those that were protective

The practice of substituting daimon for demon has been occasionally adopted, as in Black/Green1992 and Cunningham 1997. It has by no means, however, been universally employed in the scho-larship on Mesopotamian Zwischenwesen. Blakely 2006, 23. Burkert 1985, 180. On ancient Greek daimons, see also the detailed discussions in Blakely 2006,ch. 1; and Ferguson 2003, 236. Burkert 1985, 179. Given that daimon (or daemon) and demon are sometimes treated as synonyms, the utilization ofboth within a single taxonomic construct might seem somewhat surprising. The weight of connota-

110 Karen Sonik

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

or beneficent, here sub-classified as genii. The latter of these is another term deeplyembedded in the modern scholarship on the Mesopotamian Zwischenwesen, if hith-erto often applied broadly and without clear constraints on the types of interstitialentities to which it specifically refers.²¹ The term “angel,” which so frequently part-ners the term demon in Western conceptions of the supernatural, has been deliber-ately eschewed in this context to preclude the mapping of the dualistic polarizationof good and evil forces characteristic of Christianity and other monotheistic religionsonto the polytheistic Mesopotamian religious system.²²

In distinguishing between these two categories of daimon, action rather than fun-damental nature is the defining factor: the genii are helpful to or protective of humans,essentially beneficent in deed; the demons, in contrast, are those that attack humanbeings and, in rare cases, also the gods themselves, inflicting tangible suffering or mis-fortune even until death.²³ That a single class of daimon might include both helpfuland harmful types – “May the harmful [udug who seized] her stand aside, / andmay the [good udug and] good [lamma spirits] be present”²⁴ – and that a specific dai-monmight shift between these types depending on context suggests that the individualnatures of these entities were not fixed across, or even within, specific media or timeperiods.²⁵

tions accumulated by each of these terms in the English language at least, so that daimon retains aneutrality that the rather more pejorative demon lacks, is sufficient in my view to maintain the finedistinction drawn here. The term genius or genii is sometimes used interchangeably with daimon (Speziale-Bagliacca/Budd 2004, 121) though I have here defined it specifically as a subcategory of the larger group ofdaimons. The category of the genius or genii is not here extended to include the apkallu or my-thological sages as they appear in their hybrid or animal-skin clad forms particularly on the walls ofthe Neo-Assyrian palaces, though the current scholarship on the subject often does not observe thisdistinction. For the distinction between good and evil in Christianity and other monotheistic religions, incontrast to the rather more ambiguous context of polytheistic religions, see Ahn 1997, esp. 1–9, 21; fora consideration of the term “angel” in the context of the Mesopotamian Zwischenwesen, see Dietrich1997. The angel-demon model might be potentially useful as a starting point for comparisons betweenreligious systems but should not be carried beyond this initial point (see Ahn 1997, 39–41), especiallyin reference to the Mesopotamian religious system. Cunningham explored the question of whether evil in the context of the early incantations servedas “divine punishment of human transgression, or as a motiveless force operating independently ofthe senior deities,” and concluded that, as disease-bringing agents act on divine order from theearliest periods, they might best be identified as daemons, see Cunningham 1998, 46. Forerunners to Udug-hul V ll. 465–466; translation (modified) from Geller 1985, 47. See also the discussion in Green 1984. Human ingenuity, notably, might also function to turnharmful figures to protective service, as in the case of Pazuzu, so-called “king of the evil daimons,”who functions protectively against the demon-goddess Lamaštu. In more sinister examples, humaningenuity might also turn helpful daimons to harmful ones – as when sorcerers or witches turningprotective genii against their innocent human charges through lies or slanders levied against thosesame innocent victims.

Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Supernatural 111

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

The re-introduction of the term demon here (despite its pejorative connotations)to define specifically those daimons inimical or hostile to human beings, is impelledin part by the entrenchment of the term in modern scholarship on the Zwischenwesenand in part by the fact that those Mesopotamian daimons that are harmful or destruc-tive to humans, inflicting disease, misfortune, and even death on their victims, bearmore than a shadow of a resemblance to demons as traditionally understood in theWestern world.²⁶ If the Mesopotamian variety might at times be agents of rather thanrebels against the gods, and if they offer not moral temptation in the manner of Sa-tan’s minions but rather distinctly corporeal harm, they yet resemble the Westernconception of demons in the threat they posed to the ordered and civilized worldand to individual human well-being.²⁷

Given their malevolence and dangerous natures, it is perhaps not surprising thatdemons were not a popular subject of representation in the visual arts of Mesopota-mia, and that even written references to or descriptions of their physical forms wereoften vague or amorphous in nature. In those cases where they were treated in anydetail, the demons as a group were notably marked, as the monsters, by physical,geographical, and social deviations from the norms established by civilized humansand their gods. Lacking, in some characterizations, the capacity to even distinguishbetween doing good and doing harm, the galla daimons in the Sumerian composi-tion Dumuzid and G̃eštinana are characterized as “never kind, they do not know goodfrom evil.”²⁸ This characterization of them is mirrored in the utukkū lemnūtu incan-tations, in which they are described not only as “hav[ing] no shame, / know[ing] nothow to act kindly,”²⁹ but also as being bereft of kinship relations of their own:“galla have no mother; they have no father or mother, sister or brother, wife or chil-dren.”³⁰ It is no surprise, then, to find that daimons have little sympathy for the socialor blood ties of ordinary mortals: “They take the wife (from) the lap [of her husband],/ they remove the children [from the la]p? [of their father]?.”³¹

Heeßel suggested in his treatment of Pazuzu the peculiar applicability of the most negativeconnotations of the term “demon” to figures such as Pazuzu and Lamaštu, Heeßel 2002, 6. For an analysis of demons as renegade agents acting independently of the gods, see Geller’scharacterization of some of these figures as potentially “represent[ing] a misuse of authority,” Geller2007, xiii; see also the contrasting of renegade versus subordinate demons (those that obey the gods)in van der Toorn 1985, esp. 70–71. The apparent absence of moral dualism in Mesopotamian religiousbeliefs, contrasting sharply with the Judeo-Christian religious model, has occasionally led to itscharacterization as monistic: “monism posits one divine principle…The God is a coincidence ofopposites, responsible for both good and evil,” see Russell 1987, 251. While this vision of the Meso-potamian cosmos is somewhat simplistic, it explains why the Mesopotamian demons cannot beeasily read, as traditional Western demons, as representatives of a monolithic evil striving against theforces of good. Dumuzid and G̃eštinana ll. 52; translation (adapted) from Sladek 1974, 229, 234. Utukkū Lemnūtu V ll. 129– 130; translation from Geller 2007, 212. Dumuzid and G̃eštinana ll. 49; translated (modified) from Sladek 1974, 234. Forerunners to Udug-hul V ll. 475–476; translation (modified) from Geller 1985, 46–47.

112 Karen Sonik

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

With this alienation from social networks or kinship relations, the demons arelikewise physically sundered from civilization, being properly at home (as the mon-sters) in the margins of the world, the mountains, the deserts, the steppes, and theseas: “The harmful udug [daimon] is present in the steppe, the ala [daimon] envel-ops (its victim) in the steppe.”³²

The social and geographical alienation of the demons is reflected or inscribed intheir physical forms, on those rare occasions where they possess such, so that they areendowed with similarly hybrid or anomalous bodies as the monsters, these comprisinga range of theriomorphic and occasionally also anthropomorphic features: “Samana,mouth of a lion, / teeth of an ušumgal, / claws of an eagle, tail of a crab, / fearsomedog of Enlil.”³³ While the deviant forms of demons were in the Middle Ages read as“bestial perversion[s] of God’s image,”³⁴ being visually very much in keeping withthe theological association between beasts and sin, the demons of Mesopotamiashould not be read in this manner: their anomalous bodies, where described or depict-ed, signal instead their fundamental alterity, their binding to the savage wildernessand their severance from the civilized world and its norms.

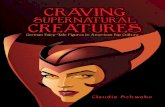

Spheres of Action and Agency: DistinguishingMonsters from Daimons in MesopotamiaIn constructing a taxonomy of the Mesopotamian Zwischenwesen, then, the mappingof the categories of monster and daimon onto the supernatural landscape offers auseful means of organizing and assessing its inhabitants (Figure 1). If the importingof foreign terms into the discourse on these entities introduces its own lingering am-biguities, it yet permits the explication of important if implicit characteristics thatunite individual Zwischenwesen with others that are “like” – and that differentiatethem from other sub-categories of interstitial being such as ghosts, witches, andsages. In the context of this discussion, both those Zwischenwesen defined as mon-sters and those defined as daimons have in common several of the key features thatfunction to distinguish them from other of the “in-between” beings occupying Mes-opotamia’s supernatural landscape: their anomalous physical bodies, their geo-graphical exile, and their social alienation. Where these two types of being divergeis in the exact nature of the “cultural work” they perform, and in their proper spheresof action and agency.

Monsters, diverging not only in habitat but also in anti-social behavior from civi-lized humans and their gods, their “Other”-ness manifested in physical forms, thatare strange, miscegenated, or otherwise anomalous, operate in the divine sphere, in-

Forerunners to Udug-hul ll. 797–9, translation (modified) from van Dijk/Geller 2003, 56. Text 71 ll. 2–6; translated in Cunningham 1997, 91. Strickland 2003, 65.

Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Supernatural 113

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

teracting primarily with the gods and, on rare occasions, with legendary heroes.³⁵Recognizable cross-culturally by their bodily, behavioral, and other transgressions,monsters are yet fundamentally cultural constructs deeply rooted in the contextsin which they developed. Their threat is cosmic, prodigious, and their actions capa-ble of threatening, even altogether overturning, the entirety of the divine order—andyet the danger they pose to ordinary humans remains because of this also somewhatabstract and distant.

Daimons, while sharing many of the key features of the monsters, are specificallymarked in Mesopotamia (as they are also in Greece) by “the intimacy of [their] con-nection to men,” as well as by their capacity to function as intermediaries betweenthe divine and the human realms, and to act either for the benefit or harm of indi-vidual human beings.³⁶ If some among their number might be dispatched by thegods, visiting divinely conceived punishment on mortals, others may as well act

Fig.1: Taxonomy of Mesopotamian Zwischenwesen

The definition presented here is markedly different from that suggested by Wiggermann in hiscomparison of Mesopotamian monsters and gods, in which he defined monsters as intervening inhuman affairs, Wiggermann 1992, 158. He suggested that the former were to be distinguished bothfrom the gods, being only occasionally given the divine determinative, and from both the demons,which he defined as “lower gods in a variety of functions, acting on behalf of the great gods or bythemselves) and [from] the spirits of the dead (eṭemmū): they never cause disease. They do not appearin the diagnostic omens, and no incantations exist against them,” Wiggermann 1992, 164. In aseminal later work, he defined monsters as “sometimes act[ing] destructively under the orders of thegods,” Wiggermann 1996, 211, n. 50, and demons as “personifications of diseases and representationsof the plague as an enemy army,” Wiggermann 1996, 211, n. 49. I believe the delimitation of the propersphere in which each functions as an active agent offers, however, a more useful means of di-stinguishing between these two types of Zwischenwesen. Blakely 2006, 22.

114 Karen Sonik

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

on instinct or personal whim in attacking or protecting individual humans. In almostall cases, however, the daimons confine their actual operations primarily to the nat-ural world, focusing their energies and attentions on ordinary mortals.³⁷ If the dai-mons resemble the monsters in their social, geographical, and physical alterityand alienation, it is in the nature of their threat that they are differentiated: the dan-ger they pose is not cosmic but personal, and is because of this considerably moreexigent for the ordinary human inhabitants of Mesopotamia than any monster’s cos-mic menacing.

Bibliography

Ahn, Gregor (1997), “Grenzgängerkonzepte in der Religionsgeschichte: Von Engeln, Dämonen,Götterboten und anderen Mittlerwesen”, in: Gregor Ahn / Manfried Dietrich (eds.), Engel undDämonen: Theologische, Anthropologische und Religionsgeschichtliche Aspekte des Gutenund Bösen, Münster, 1–48.

Bennett, Gaymon / Hewlett, Martinez J. / Peters, Ted / Russell, Robert J. (eds.) (2008), TheEvolution of Evil, Göttingen.

Black, Jeremy A. (1988), “The Slain Heroes – Some Monsters of Ancient Mesopotamia”,SMSBulletin 15, 19–25.

Black, Jeremy A. / Cunningham, Graham / Robson, Eleanor (2006), The Literature of AncientSumer, Oxford.

Black, Jeremy A. / Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons, and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia:An Illustrated Dictionary, Austin.

Blakely, Sandra (2006), Myth, Ritual, and Metallurgy in Ancient Greece and Recent Africa,Cambridge.

Burkert, Walter (1985), Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical (John Raffan, trans.), Cambridge.Cooper, Jerrold S. (1978), The Return of Ninurta to Nippur: an-gim dím-ma, Rome.Cunningham, Graham (1997), Deliver Me from Evil: Mesopotamian Incantations, 2500–1500 BC,

Rome.Cunningham, Graham (1998), “Summoning the Sacred in Sumerian Incantations”, Studi epigrafici

e linguistici sul Vicino Oriente antico 15, 41–48.Dietrich, Manfried (1997), “Sukkallu – der mesopotamische Götterbote. Ein Studie zur

‘Angelologie’ im Alten Orient”, in: Gregor Ahn / Manfried Dietrich (eds.), Engel undDämonen: Theologische, Anthropologische und Religionsgeschichtliche Aspekte des Gutenund Bösen, Münster, 49–74.

Febvre, Lucien (1982), The Problem of Unbelief in the Sixteenth Century: The Religion of Rabelais(Beatrice Gottlieb, trans.), Cambridge.

Ferguson, Everett (2003), Backgrounds of Early Christianity, Grand Rapids.Geller, Markham J. (1985), Forerunners to Udug-hul: Sumerian Exoricistic Incantations, Stuttgart.Geller, Markham J. (2007), Evil Demons: Canonical Utukkū Lemnūtu Incantations, Helsinki.

Two rare instances in which demons appear to menace the gods are discussed in van Dijk/Geller2003, 2: HS 1555+1587, in which “Enlil experienced (Samana-disease) / on his neck,” and HS 1588+1596, in which “Namtar inflicts headache…[and] the gods of heaven were afraid, they came down(lit. ‘in’) heaven, / the gods of the earth were afraid, and were standing around the grave. / The greatgods themselves made (funerary) offerings,” van Dijk/Geller 2003, 39–40.

Mesopotamian Conceptions of the Supernatural 115

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM

George, Andrew R. (2003), The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition andCuneiform Texts, Oxford.

Green, Anthony (1984), “Beneficent Spirits and Malevolent Demons: The Iconography of Good andEvil in Ancient Assyria and Babylonia”, Visible Religion 3, 80–105.

Heeßel, Nils P. (2002), Pazuzu: archäologische und philologische Studien zu einemaltorientalischen Dämon, Leiden.

Huet, Marie-Hélène (1993), Monstrous Imagination, Cambridge.Jacobsen, Thorkild (1987), The Harps that Once–: Sumerian Poetry in Translation, New Haven.Klein, Jacob (1997), “The God Martu in Sumerian Literature”, in: I. L. Finkel / Markham J. Geller

(eds.), Sumerian Gods and their Representations, Groningen, 99–116.Lambert, W. G. (2008), “Mesopotamian Creation Stories”, in: Markham Geller / Mineke Schipper

(eds.), Imagining Creation, Leiden: 15–60.Lang, Bernhard (2001), “Zwischenwesen”, in: Hubert Cancik / Burkhard Gladigow / Matthias

Laubscher (eds.), Handbuch religionswissenschaftlicher Grundbegriffe Vol. 5, Stuttgart.Merriam-Webster, Inc. (1999), Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of World Religions, Springfield.Neiman, Susan (2002), Evil in Modern Thought: An Alternative History of Philosophy, Princeton.Neville, Jennifer (2001), “Monsters and Criminals: Defining Humanity in Old English Poetry”, in:

Karin E. Olsen and L. A. J. R. Houwen (eds.), Monsters and the Monstrous in MedievalNorthwest Europe, Leuven, 103–122.

Pongratz-Leisten, Beate (2001), “The Other and the Enemy in the Mesopotamian Conception of theWorld”, in Robert M. Whiting (ed.), Mythology and Mythologies: Methodological Approachesto Intercultural Influences. Proceedings of the Second Annual Symposium of the Assyrian andBabylonian Intellectual Heritage Project. Held in Paris, France, October 4–7, 1999, Helsinki,195–231.

Porada, Edith (1987), “Introduction”, in: Ann E. Farkas, Prudence O. Harper and Evelyn B. Harrison(eds.), Monsters and Demons in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: Papers Presented in Honorof Edith Porada, Mainz am Rhein, 1–11.

Russell, Jeffery Burton (1987), The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity,Ithaca.

Sladek, William R. (1974), Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld, PhD Dissertation, The JohnsHopkins University, Baltimore.

Sonik, Karen (2012), “The Tablet of Destinies and the Transmission of Power in Enūma eliš”, in:Gernot Wilhelm (ed.), Organization, Representation, and Symbols of Power in the AncientNear East: Proceedings of the 54th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Würzburg20–25 July 2008, Winona Lake, 387–396.

Speziale-Bagliacca, Roberto / Budd, Susan (2004), Guilt: Revenge, Remorse, and Responsibilityafter Freud, New York.

Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003), Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art,Princeton.

Talon, Philippe (2001), “Enūma eliš and the Transmission of Babylonian Cosmology to the West”,in: Robert M. Whiting (ed.), Mythology and Mythologies. Methodological Approaches toIntercultural Influences, Helsinki, 265–277.

van der Toorn, Karel (1985), Sin and Sanction in Israel and Mesopotamia: A Comparative Study,Assen.

van Dijk, Johannes J. A. / Geller, Markham J. (2003), Ur III Incantations from the Frau ProfessorHilprecht-Collection, Jena, Wiesbaden.

Westenholz, Joan Goodnick (1997), Legends of the Kings of Akkade, Winona Lake.Wiggermann, F. A. M. (1992), Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts, Groningen.Wiggermann, F. A. M. (1996), “Scenes from the Shadow Side”, in: M. Vogelzang and H. L. J.

Vanstiphout, Mesopotamian Poetic Language: Sumerian and Akkadian, Groningen, 207–230.

116 Karen Sonik

Brought to you by | Brown University Rockefeller LibraryAuthenticated | 128.148.231.12

Download Date | 10/26/13 7:15 PM