Memory and the everyday landscape of violence in post-genocide Cambodia

Transcript of Memory and the everyday landscape of violence in post-genocide Cambodia

This article was downloaded by: [KSU Kent State University]On: 31 October 2012, At: 08:42Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office:Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Social & Cultural GeographyPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscriptioninformation:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rscg20

Memory and the everyday landscape ofviolence in post-genocide CambodiaJames A. Tyner a , Gabriela Brindis Alvarez a & Alex R. Colucci aa Department of Geography, Kent State University, USAVersion of record first published: 31 Oct 2012.

To cite this article: James A. Tyner, Gabriela Brindis Alvarez & Alex R. Colucci (2012): Memoryand the everyday landscape of violence in post-genocide Cambodia, Social & Cultural Geography,DOI:10.1080/14649365.2012.734847

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2012.734847

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantialor systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that thecontents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae,and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall notbe liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of thismaterial.

Memory and the everyday landscape of violencein post-genocide Cambodia

James A. Tyner, Gabriela Brindis Alvarez & Alex R. ColucciDepartment of Geography, Kent State University, USA, [email protected]; [email protected];

This paper addresses the politics of memory in post-genocide Cambodia. Since 1979genocide has been selectively memorialized in the country, with two sites receiving officialcommemoration: the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide Crimes and the killing fields atChoeung Ek. However, the Cambodian genocide was not limited to these two sites.Through a case study of two unmarked sites—the Sre Lieu mass grave at Koh Sla Damand the Kampong Chhnang Airfield—we highlight the salience, and significance, of takingseriously those sites of violence that have not received official commemoration. We arguethat the history of Cambodia’s genocide, as well as attempts to promote transitionaljustice, must remain cognizant of how memories and memorials become politicalresources. In particular, we contend that a focus on the unremarked sites of past violenceprovides critical insight into our contemporary understandings of the politics ofremembering and of forgetting.

Key words: landscape, memory, memorialization, violence, Cambodia.

Introduction

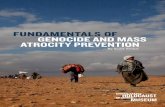

Some 60 km south of Phnom Penh, nestled

among the rolling hills of Kampot province,

sits an altogether unremarkable earthen

structure. Spanning nearly 12 km in length,

15m high, and 20mwide, what remains of the

Koh Sla Dam seems at peace among the short

grass and scrub, its flanks crisscrossed by

narrow footpaths connecting the stilt houses

that dot the scene. The villagers who tend the

rice fields and fish in the surrounding ponds

anchor Koh Sla in the seemingly timeless

landscape of rural Cambodia (Figure 1).

But the tranquil repose of this earthwork in

such a halcyon setting conceals a darker past.

Under the vegetation that covers its canted

bulk—beneath the sediment of intervening

years—lingers a history of starvation, disease,

exposure, and execution. Nine thousand men,

women, and children perished here, killed, or

left to die at the hands of the Khmer Rouge.

Unlike other sites of brutality and mass

violence, the landscape of Koh Sla bears no

consecration. No signs give voice to its past.

No structure marks the graves of its builders:

their forced labor and mass murder remain

absent from the popular narratives of geno-

cide. No tour buses idle nearby while curious

Social & Cultural Geography, iFirst article, 2012

ISSN 1464-9365 print/ISSN 1470-1197 online/12/000001-19 q 2012 Taylor & Francis

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2012.734847

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

tourists snap photos. In a country that has

sought to ostensibly illuminate, explain, and at

times commodify its past, Koh Sla’s history is

remarkable precisely for being so unremarked.

In Cambodia, genocidal violence is inscribed

in the everyday landscape—such as Koh Sla.

But the memorialization of violence is circum-

scribed. Violence is most visible at but a few

selected sites of ‘remembrance’, notably the

Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide Crimes and

the killing fields at Choeung Ek. However, it is

our contention that these highly visible and

officially commemorated sites serve to obfus-

cate other, more mundane sites (and practices)

of violence. Through a case study of two

unmarked sites, the Koh Sla Dam and an

abandoned airfield, we draw attention to the

existence of landscapes of violence that have

not been placed within their geographical or

historical contexts; places that remain

unmarked and unremarked and yet continue

to have an impact. In this paper, we consider

those landscapes and legacies of violence that

are ‘hidden in plain sight’: those places that are

not commemorated through official channels

but are in fact experienced on a day-to-day

basis. It is our contention that these sites, more

than the politicized and commodified memor-

ial sites of violence, function as crucial

elements as Cambodians attempt to reconcile

their tragic past anduncertain future (Figure 2).

The remainder of this paper consists of five

main sections. In the first, we provide a

theoretical overviewof violence and thepolitics

ofmemory.This is followedby abrief reflection

on our methodology; an overview of the

Cambodian genocide; a discussion of ongoing

attempts to memorialize the genocide; and an

examination of two unmarked and unre-

marked sites of genocidal violence. We con-

clude with a plea that the future research on

landscapes of memorialization will focus not

Figure 1 Landscape around Koh Sla Dam, Kampot Province, Cambodia.

2 James A. Tyner et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

only on official, popular, or otherwise

remarked sites, but also on those sites that are

hidden on the everyday landscape.

Violence and the politics of memory

The past—that which we memorialize—never

remains the same but instead ‘is constantly

selected, filtered and restructured in terms set

by the questions and necessities of the present’

(Jedlowski 2001: 30). Geographers and other

social scientists have written extensively on

landscapes of memory and specifically the

memorialization of violence (Charlesworth

1994; Foote 1997; Forest, Johnson, and Till

2004; Johnson 1995; Till 2005). This work is

significant, in that it demonstrates the primacy

of ‘landscape’ to our everyday experiences—

including those of violence. There are traces of

violence and death that ‘monumental work’

effaces, to be replaced with a certainty that

itself constitutes a form of violence. Monu-

mentality is a way to transcend death due to its

durability; monumentality may create a

material appearance whereby the brutal lega-

cies of violent practices may be ignored or

transformed as a political power (Lefebvre

1991: 221).

Memory, as Pierre Nora (1989: 9) writes,

‘takes root in the concrete, in spaces, gestures,

images, and objects.’ In short, memory is

‘spatially constituted’; it is ‘attached to “sites”

that are concrete and physical—the burial

places, cathedrals, battlefields, prisons that

embody tangible notions of the past—aswell as

to “sites” that are nonmaterial—the celebra-

tions, spectacles and rituals that provide an

aura of the past’ (Hoelscher and Alderman

Figure 2 Cambodia.

Everyday landscape of violence 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

2004: 349). However, as the work of Owen

Dwyer,DerekAlderman, and StevenHoelscher

(among others) has made clear: memorials and

monuments are political. As Dwyer (2004:

425) explains, memorials and monuments ‘are

inextricably entwined in the production of the

past’; however, these ‘landscapes seek to

present in tangible form the past itself, not the

processes through which the “past” is pro-

duced.’ In short, landscapes are neither neutral

nor static. They represent, and are represented

by, political processes: a politics of memory.

A politics of memory highlights the fact that

‘what is commemorated is not synonymous

with what has happened in the past’ (Dwyer

and Alderman 2008: 167). Commemoration is

often used as a tool to create, erase, or reinvent

an official history and collective memory, and

thereby utilized to justify present forms of

social representation and political presence.

Hence, apart from their material form, and

their aesthetic experience, memorials hide a

historical and political interpretation. Official

memorials, therefore, do not simply testify a

‘real’ history, but rather represent what some

want to believe, or what some want others to

believe, in the monument. Thus, memorials

‘narrate history in selective and controlled

ways—hiding as much as they reveal’ (Dwyer

and Alderman 2008: 168). Memories serve as

a way for society to conceive or forget its past;

but memorials may also project the past

according to a variety of national myths,

ideals, and political needs.

Dwyer and Alderman (2008: 167) explain

also that memorials are important symbolic

conduits not only for expressing a version of

history, but also for casting legitimacy upon it.

Some memorials, for example, attempt to

provide a sense of community and to relate to

past atrocities. Thus, while the principal aim

of memories and memorials is, arguably, to

educate future generations and to shape a

sense of shared experience, other memorials

are conceived as means of absolving guilt.

However, there is often an uneasy tension

between ‘remembering’ and ‘forgetting.’ As

Ernest Renan ([1882] 1995) remarked long

ago, a duality between the ‘will’ to remember

and a ‘duty’ to forget appears crucial for the

creation of a shared nationhood and, by

extension, the establishment of a cohesive

national identity. In other words, it is import-

ant that certain events—while not entirely

erased—should not be commemorated; these

events, rather, may be forgotten. Other writers,

however, remain unconvinced. Paul Ricoeur

(2000) explains that abuses of ‘memory,’

coupled with abuses of ‘forgetting’ will remain

politically contentious issues and thus subject

to manipulation. In so doing, Ricoeur suggests

that the promotion of a ‘just memory’ is to be

achieved through a ‘duty to remember.’

Ultimately, as Hoelscher and Alderman

(2004: 349) argue, the ‘study of social memory

inevitably comes around to questions of

domination and the uneven access to asociety’s

political and economic resources.’ There is

never simply onememory, nor is there only one

way to remember. Different memories contest

for the monopoly of the conservation and

preservation of the past. In the process, not all

sites are memorialized—although they may be

remembered and decidedly not forgotten.

Consequently, it is important to consider

seriously those unmarked but not forgotten

sites, for these sites speak loudly to the ongoing

contestation of the inscription of memory and

remembrance on the landscape.

A note on methodology

Our paper is positioned within a long tradition

of ethnographical investigation; however,

there are certain salient issues related to the

4 James A. Tyner et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

study of unremarked or ‘forgotten’ sites of

memorialization. We begin by acknowledging

that any forwarding of commemorative sites

will always be partial and incomplete; indeed,

in Cambodia there are literally hundreds of

potential sites that hold significance in the

everyday lives of everyday Cambodians.

Throughout the genocidal years—as detailed

below—the Khmer Rouge initiated several

infrastructural projects: dams, reservoirs, and

airfields. These projects invariably utilized

forced labor and, invariably, these were—and

remain—sites of mass violence.

Over the course of ten years, the lead author

(Tyner) has made seven trips to Cambodia

and, in the process, has traveled throughout all

provinces of the country. As part of a larger

project designed to provide a reconstruction of

the ‘geography’ of Democratic Kampuchea,

Tyner has made repeated visits to both well-

known and lesser-known sites associated with

the genocide, including, for example, visits to

numerous sites of former security centers—

which, today, are often nothing more than rice

fields—as well as dozens of mass graves sites.

He has also conducted interviews with both

‘victims’ and perpetrators’ who continue to

live and work in the environs surrounding

these sites. Moreover, Tyner has worked

closely with researchers at the Documentation

Center of Cambodia in an attempt to identify

other unmarked sites of atrocity.

Most sites—apart from selected, and state-

sanctioned, venues—exhibit no visual remin-

ders of their previous existence. The Kanseng

Security Center, which was located in Rata-

nakiri Province, for example, no longer exists.

Neither do any structures associated with the

Kok Kduouch Security Center, once situated in

Kratie Province. Local residents, however, well

remember these institutions—both of which

witnessed the deaths of thousands of people.

During the course of his fieldwork, Tyner—

with the assistance of local guides and

translators—has attempted to recover the

stories of these people. And for many of

these individuals, they comment upon the

overall ignorance of the younger generations.

The genocide as a whole goes largely

unremarked; the ongoing tribunal has amelio-

rated this somewhat, but only very selectively.

Those who lived through the genocide com-

ment that there is a disconnect between the

official narrative of genocide and the lived

reality of violence—a reality that they relive

daily as they utilized the dams, the reservoirs,

and the roads constructed during the Khmer

Rouge years. For these individuals, they speak

mostly out of a perceived duty to not forget as

opposed to an obligation to remember. In

other words, for many survivors—and we

certainly do not wish to generalize—it is far

more important to not forget what happened,

rather than to actively memorialize the land-

scape. And while the construction of temples

dedicated to those who died is certainly

important, there is a recognition that no

amount of commemoration will return their

loved ones; no amount of memorializing will

replace their sense of loss.

From genocide to post-genocide

When considering post-conflict landscapes, it

is imperative to understand that the ‘post’ does

not mean ‘after’ but rather ‘beyond.’ And here,

the latter term ‘beyond’ refers to moving

beyond the immediacy of war and to consider

the enduring legacies of violence—both

material and symbolic—that remain a part of

the landscape (Tyner 2010: 27). In the

following section, we provide an overview of

the genocide—while remaining cognizant that

for many individuals in Cambodia, the

violence has never completely ended.

Everyday landscape of violence 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

Cambodia’s contemporary landscape

reflects its recent, violent past. Between 1970

and 1975, the country was engulfed in a

devastating civil war—itself a ‘sideshow’ of the

Vietnam War (cf. Shawcross 2002). Then, on

17 April 1975, the armed forces of the

Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK; better

known as the ‘Khmer Rouge’) entered Phnom

Penh, Cambodia’s capital city, effectively end-

ing the civil war but setting in motion a

genocide that would ultimately claim the lives

of nearly one-quarter of the country’s

population.

To achieve their political and economic

goals, the Khmer Rouge embarked on a

massive program of social and spatial engin-

eering. Both in theory and practice, CPK

leaders drew on the radical extremes of Mao

Zedong’s 1956–1958 ‘Great Leap Forward’ in

an attempt to bring about a complete and rapid

transformation of the Cambodian political and

economic society. Once transformed, the

Khmer Rouge envisioned a state that would,

in principle, but not in actuality, be entirely self-

sufficient and free from foreign domination

(Tyner 2008).

In theweeks andmonths following the fall of

PhnomPenh, the cities and towns of Cambodia

were evacuated, their inhabitants forced onto

agricultural collectives, and labor camps dis-

tributed throughout the countryside. Hospi-

tals, factories, and schools were literally

demolished; money and wages abolished;

monasteries and temples destroyed or con-

verted into storehouses or prisons (Chandler

1991, 2000; Kiernan 1985, 1996; Quinn 1989;

Tyner 2008). Indeed, in their desire to make a

‘super great leap forward’ into communism,

theKhmerRouge justified their brutal practices

of forced evacuations and resettlement

schemes. Their goal was to construct, immedi-

ately, a homogenous, egalitarian society. This

entailed a literal wiping clean of the slate that

was Cambodia. In a blunt and violent manner,

the Khmer Rouge leadership spoke of ‘cleaning

up’ the country. As McIntyre (1996: 758)

concludes, ‘In the swidden politics of the

Khmer Rouge, Phnom Penh . . . and other

cities and towns were slashed and sometimes

burned to clear the brush for the new growth of

Cambodian society.’

Cambodia, metaphorically speaking, ceased

to exist, replaced and renamed by Democratic

Kampuchea.1 And for many leaders of the

Khmer Rouge regime, in accordance with their

understanding of ‘total revolution,’ it was not

acceptable to simply build on earlier foun-

dations. Rather, the Khmer Rouge explicitly

sought to erase both time and space to create

(in their minds) a pure utopian society. The

project of state building, of forging Demo-

cratic Kampuchea, consequently, was not—

contrary to the claims of some scholars—an

attempt to refashion a past empire; it was not

to be a return to a golden era of Cambodian

history. Thus, while it often holds that new

governments create ‘material landscapes as

stages to display a distinctive national past’

(Till 2004: 351), this was not the case with the

Khmer Rouge. The motivation of the Khmer

Rouge leadership was not to recreate the

indigenous spaces of the Angkorian kingdom

(c. ninth to fourteenth centuries) but instead to

create an entirely new, modern, productive

communal society. The transformation of

Cambodia into Democratic Kampuchea was

to be complete. Not only did 17 April 1975

mark, in the words of the Khmer Rouge, ‘Year

Zero,’ it also marked ‘Ground Zero.’

As a state, Democratic Kampuchea lasted

just under four years. But in that brief period,

approximately two million people—most of

whom were Khmer—perished as a result of

mass starvation, disease, and execution.

Debate remains as to the proportion of

deaths—of thosewho died fromdirect violence

6 James A. Tyner et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

(i.e., execution) and those who died from

indirect means (e.g., starvation, disease,

exhaustion, and exposure). A consensus is

developing, however, that deaths were roughly

proportional, that is, approximately 50 per

cent of people died due to direct violence

while the remainder died from other causes

(De Walque 2005; Etcheson 2005; Heuveline

1998).

On 25 December 1978, Vietnamese forces

totaling over 100,000 surged into Democratic

Kampuchea. They were joined by approxi-

mately 20,000 Cambodians, most of whom

were former Khmer Rouge cadre who had

established a government-in-exile known as

the National Salvation Front (NSF). After

years of escalating tension and sporadic

fighting, the move by Vietnam was portrayed

(by themselves) as an act of liberation: to bring

an end to nearly four years of genocide. For

many other states—including both Demo-

cratic Kampuchea and the USA, Vietnam’s

intervention was represented as an illegal

invasion by one sovereign state into another.

The disorganized forces of the Khmer Rouge

were unable to withstand the Vietnamese

onslaught and, on 7 January 1978, Phnom

Penh once again fell. Soon thereafter, the

leaders of the Hanoi-backed NSF declared the

People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK).

However, unlike Cambodia, which was lit-

erally erased by the Khmer Rouge, Democratic

Kampuchea was not to be erased, but rather

memorialized in an attempt to provide legiti-

macy to the PRK.

As Chandler (2008: 357) explains, the

fledgling People’s Republic of Kampuchea

and its Vietnamese advisors faced enormous

economic, organizational, and social pro-

blems. Of paramount importance, however,

was how Democratic Kampuchea was to be

remembered. Politically, the People’s Republic

of Kampuchea consisted largely of former

Khmer Rouge cadre: Hun Sen, Heng Samrin,

and Chea Sim, among others. Furthermore,

the ostensibly social PRK faced the problem of

how the socialist Democratic Kampuchean

period should be regarded (Chandler 2008:

357). Faced with both internal and external

difficulties, geopolitical opposition, the PRK

(and its Vietnamese backers) was impelled to

represent their actions—as well as those of the

Khmer Rouge—through a politics of memory.

Placing genocide in post-genocideCambodia

Since landscape is important to the working of

ideology and political order, it is not uncom-

mon that changes in political regimes will

often be accompanied by efforts to remake

official public landscapes (Light and Young

2010: 1454). This is readily seen in following

the defeat of the Khmer Rouge and the

establishment of the People’s Republic of

Kampuchea. From the outset, PRK officials

and their Vietnamese advisors labeled the

Khmer Rouge ‘genocidal’ and ‘fascist’ to

encourage comparisons with Hitler’s Germany

and to downplay the Khmer Rouge’s socialist

credentials (Chandler 2008: 360). To facilitate

this political maneuver, two sites were quickly

transformed into internationally visible places

of genocide remembrance. The first was the

conversion of a former ‘security center’ into a

museum of genocidal crimes and the second

was the establishment of a mass grave site into

a memorial site.

Located in Phnom Penh, Tuol Sleng had

once been to a high school.2 Under the Khmer

Rouge, the site was converted into the state’s

central ‘security center,’ designated as ‘S-21.’3

Throughout its brief existence (c. 1976–

1979), the facility ‘processed’ approximately

13,000 prisoners. Once arrested at detained,

Everyday landscape of violence 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

prisoners were subject to brutal conditions,

including torture, starvation, and, ultimately,

execution. Less than 300 people are known to

have survived Tuol Sleng.4

Leadership of the PRK saw a political

opportunity at S-21. According to Hughes

(2003: 26), the long-term ‘national and

international legitimacy of the People’s Repub-

lic of Kampuchea hinged on the exposure of the

violent excesses of Pol Pot . . . and the

continued production of a coherent memory

of that past, that is, of liberation and

reconstruction at the hands of a benevolent

fraternal state.’ Under the direction of Mai

Lam, a Vietnamese colonel who had extensive

experience in legal studies and museology, the

site was transformed into an internationally

known Museum of Genocide Crimes

(Chandler 1999: 4). Indeed, by 25 January

1979—just two weeks after Vietnam’s victory

over the Khmer Rouge—the museum was

opened to a group of journalists from socialist

countries. The Museum was officially opened

to the public in July 1980.

As a museum, S-21 was kept largely intact,

with only minor modifications to the com-

pound made. Very little interpretative material

is provided; the exhibits consist largely of

instruments of detainment (i.e., shackles) and

torture. Such a Spartan design was deliberate

in that it served the political objectives of both

the PRK and Vietnam. Indeed, the symbolic

import of the museum was to provide neither

conceptual nor contextual understanding of

either the prison itself or the genocide more

broadly; rather, the purpose was to affect a

separation between the crimes of the Khmer

Rouge and the newly installed government of

the PRK—itself dominated by former Khmer

Rouge members. As Sion (2011: 3) states

bluntly: the display of ‘physical horrors’—the

shackles, instruments of torture, and skulls—

served (and continue to serve) political goals:

the legitimacy of political rule in the country.

The Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide

Crimes is linked—symbolically and in histori-

cal practice—to another memorial site: the

killing fields at Choeung Ek. In the early

1980s, forensic teams of the PRK excavated a

mass grave site located 15 kilometers south of

Phnom Penh. Once an orchard and later a

Chinese cemetery, the site was utilized by the

Khmer Rouge for mass executions—most of

whom were former detainees at Tuol Sleng. In

total, an estimated 9,000 victims were killed

and buried at the site.

In 1989, the site was opened to the public,

dominated by the erection of a monumental

stupa, filled with skulls and other bones visible

through windows on all four sides. Although

stylistically the stupa is inspired by Khmer

religious motifs, it is wholly antithetical to

Khmer religious practice. As both Hughes

(2008) and Sion (2011) explain, the entire

memorial is geared toward international

tourists and, consequently, toward the pro-

motion of both politicalmessage and economic

profit. As with Tuol Sleng, little historical

background is given on how the Khmer Rouge

came to power, what drove their ideology, how

they implemented their genocidal policy, and

how they were later defeated (Sion 2011: 8).

The killing fields at Choeung Ek have

undergone significant, albeit superficial, reno-

vation. Throughout the 1990s and into the

twenty-first century, the site remained largely

undisturbed since the initial excavations. A

simple dirt road led to simple entrance; a small

‘gift’ store sat forlornly to the side. In 2005,

however, a Japanese corporation, JC Royal,

obtained from the Cambodian government a

thirty-year license to operate the site. In return,

JC Royal pays an annual fee of US$15,000 and

awards an undisclosed number of scholarships

to Cambodian students (Sion 2011). Now,

8 James A. Tyner et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

visitors to Choeung Ek—the overwhelming

majority of whom are foreign—are confronted

with an elaborate gated entrance, a ticket

counter, public toilets, a renovated gift shop,

and an air-conditioned screening room show-

ing a brief documentary of the genocide. The

once-dirt road has been replaced by tarmac,

and a series of cafes dot the journey.

Tim Edensor (2005: 831) writes that

museums and other memorialized sites often

work to ‘banish ambiguity.’ He explains,

rather, that these sites often forward a

particular narrative that potentially limits

interpretations. The ongoing memorialization

of Cheoung Ek provides little interpretive

understanding for visitors. The site is more of

a profit-making venture than it is a site to reflect

upon genocide. The physical remains of

victims—from the show-cased skulls in the

stupa to the incomplete excavation of bodies

throughout the site—have become commod-

ities that, once publicly exhibited, cover up the

involvement of former Khmer Rouge still

active in public affairs and still enjoying

complete impunity (Sion 2011: 17).

Most studies of the memorialization of the

Cambodian genocide, quite properly, focus on

the political meanings associated with Tuol

Sleng and Choeung Ek (Chandler 2008;

Hughes 2003, 2008; Sion 2011). These are

the two most visited sites of genocide in

Cambodia—at least, by foreign tourists. And

yet, in many respects, these sites continue to

represent the ‘historical erasure’ of Cambodia’s

victims. As Williams (2004: 250) concludes,

‘Tuol Sleng and Choeung Ek are alienating

because their lack of any personal accounts or

stories of lost lives.’ This alienation, moreover,

is deliberate.

In a 1998 press conference, Prime Minister

Hun Sen5 enjoined people to ‘dig a hole and

bury the past’ (Chandler 2008: 356). His

statement was, and is, indicative of the

government’s position on the memorialization

of the genocide. Indeed, Chandler (2008: 356)

writes of an ‘officially enforced amnesia’ that

coexists uneasily with the ongoing efforts of

scholars and activists to document and

remember the broader context of the genocide.

In recognition of these efforts,wemaintain that

attention should be directed to other sites of

tragedy: those genocidal places that remain

unmarked and largely unnoticed by the legions

of foreign visitors, but remain all-too-present

for the people of Cambodia as they go about

their everyday lives.

The unmarked memorials of theCambodian genocide

The killing fields at Choeung Ek have become

iconic. The site, however, is far fromunique. As

of 2010, an estimated 300 mass grave sites (or

19,000 grave pits) have been discovered. New

sites are found on a near-annual basis; the vast

majority of these sites remain unmarked.

Likewise, Tuol Sleng was neither the only nor

themost ‘deadly’ of security centers. Andwhile

the exact number of prisons remains unknown,

scholars at the Documentation Center of

Cambodia estimate that there were approxi-

mately 300 security centers in operation.

Approximately 50 km north of Phnom Penh

was the Bati District Reeducation Center.

During the Khmer Rouge period, a Buddhist

temple (Wat Kokoh) was converted into a

prison and execution site. An estimated 60,000

people were killed at this temple (Ea 2005: 60).

The ‘privileging’ of Tuol Sleng and Choeung

Ek belies the near ubiquity of these mass grave

sites and security centers. Indeed, it is our

contention that the over emphasis on these two

sites serves to spatially and temporally frame

the Cambodian genocide, thereby contributing

to the political uses of memory evinced by the

Everyday landscape of violence 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

government. The genocide is rendered spatially

to the Tuol Sleng–Choeung Ek nexus,

suggesting that the violence was confined

geographically. Likewise, the genocide is

temporally circumscribed, restricted to those

events that transpired at these locations. Of

significance, this spatial and temporal bound-

ing of the genocide is reflected in the ongoing

international tribunal: the Extraordinary

Chambers of the Cambodian Courts (ECCC).

The ECCC was established in 2003—thirty

years after the genocide took place.6 The

political machinations, both domestically in

Cambodian and internationally, have received

considerable attention and justified criticism.

In large part, the ECCC has been widely

criticized because of the restrictive jurisdic-

tional bounds established.On the onehand, the

tribunal’s personal jurisdiction limits those to

be held accountable. Following intense nego-

tiations between the Cambodian government

and the United Nations, all parties agreed to

focus on a limited universe of defendants

(Ciorciari 2009: 72). Consequently, in the first

trial, conducted in 2009, the former comman-

der ofTuol Sleng,KaingGuekEav (aliasDuch),

was convicted ofwar crimes and crimes against

humanity.7 In 2011, a second trial was set to

begin. Defendants were to include Nuon Chea,

Deputy Secretary-General and President of

the Representative Assembly of Democratic

Kampuchea; Ieng Sary, Deputy Prime Minister

in charge of Foreign Affairs; Khieu Samphan,

President of Democratic Kampuchea; and Ieng

Thirith,Minister of SocialAffairs andActionof

Democratic Kampuchea. The current govern-

ment has made its position known: if this latter

trial occurs, itwill be the last trial and thereafter

the ECCC will subsequently be abolished. In

line with the attitude to ‘dig a hole and bury the

past’ attempts to obtain either restorative or

retributive justice will be blocked.

On the other hand, the tribunal has also

been restrictive vis-a-vis its temporal jurisdic-

tion. Again, after heated discussion, both the

United Nations and the Cambodian govern-

ment agreed that the tribunal would hear cases

for alleged crimes that occurred only between

17 April 1975 and 6 January 1979. For all

parties concerned, this decision was politically

motivated, in that it will prevent any discus-

sion of the broader geopolitical events prior to

and following the genocide (cf. Bonacker,

Form, and Pfeiffer 2011).

We argue that both the personal and

temporal jurisdictional bounds entail a spatial

component, one that is directly manifest in the

ongoing memorialization of the genocide.

Because memorials (such as Tuol Sleng)

typically reflect the values and objectives of

government leaders, they tend to exclude those

histories that fail to conform to official

narratives (cf. Dwyer and Alderman 2008).

Accordingly, the memorialization of the

genocide becomes part and parcel of a specific

and judicious representation that conforms to

the politically negotiated tribunal.

As Chandler (2008: 365–366) acknowl-

edges, everyone in Cambodia over 40 years of

age is aware of what happened; however, the

selective memorialization and bounding of the

genocide will do nothing to inform young

Cambodians about either Democratic

Kampuchea or of the genocide. Indeed, as

Munyas (2008: 414) finds, ‘in the absence of

adequate education on the history of the Khmer

Rouge period, the prevalent exposure to the

horrors of the genocide at homes, schools,

museumsandmemorials hasworked toproduce

fear, anger, disbelief or denial in many Cambo-

dian youth, sustained their myths and has left

themwith several compelling questions, such as

“why did Khmer kill Khmer?”’

In this penultimate section, followingDwyer

and Alderman’s (2008: 172) contention that

10 James A. Tyner et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

‘public remembrance of atrocity is necessary as

a tool for facilitating social compensation to

victimized groups, moral reflection among the

larger society, and public education, we high-

light two unmarked sites of violence associated

with the Cambodian genocide. We argue that

as scholars of memories and memorialization,

it is imperative to bring to light those as-yet-

unmarked sites of violence—sites that are

experienced daily by (and thus serve as an ever-

present reminder to) survivors of atrocities.

The Sre Lieu mass grave

Throughout the Cambodian CivilWar, as parts

of the country were ‘liberated’ by the Khmer

Rouge, villagers were gradually subsumed into

various collectives and work brigades. Collec-

tivized labor was a stalwart of Khmer Rouge

policy. Modeled after the Khmer Rouge armed

forces (‘the People’s National Liberation

Army), Cambodian citizens were assembled

into various ‘fighting forces.’ Operationally,

peoplewere divided intowork ‘forces’ basedon

age and sex. Adults, those aged between 14 and

50, were forced into mobile work brigades

termed kong chalet. Males belonged to kong

boroh and females to kong neary. The heaviest

and most arduous work was performed by

these two groups: plowing fields, planting and

transplanting rice, cutting timber, and digging

and transporting dirt for irrigation projects.

Those who were younger and unmarried

usually traveled great distances from their

collectives to the work site (Mam 2004: 134).

In 1973, Khmer Rouge cadre began work on

a massive infrastructure project near Sre Lieu

village in the recently liberated Kampot

Province. Thousands of Cambodians were

forcibly relocated to the site to construct the

Koh Sla Dam. Conditions were deplorable,

with many people dying of starvation,

exposure, and disease. Indeed, so high was

the mortality that the Khmer Rouge actually

established a mobile hospital (designated as

Zone 35 Hospital) at the site. However,

because of inadequate medical personnel and

of proper medicines, few patients actually

received adequate care. In fact, as survivors

recall, patients were just as likely to die of

improper medicines as they were from disease.

Construction was slow and, after 17 April

1975, local Khmer Rouge officials redoubled

their efforts. Additional work brigades were

deployed to the site and work continued

through 1977. Laborers continued to suffer.

Malaria and cholera was rampant, and many

others died from injuries. Srey Neth, a

survivor, was assigned to bury the members

of her unit who died. She recalls: ‘I was

forbidden by [the Khmer Rouge] from telling

others about the number of deaths.’ She

explains that ‘Sometimes they [the Khmer

Rouge] woke me up in the middle of the night

and ordered me to take bodies to be buried . . .

The number of bodies I buried ranged from

two to six per night.’8 Nget Chanthy was only

16-year old when she was forced to labor at

the site. Her duties included the clearing of

forests and the transport of dirt to build the

earthen dam. Food was inadequate and people

worked in constant fear of the Khmer Rouge.9

Prum (2006) writes first hand of the dying

associated with the Koh Sla Dam. Throughout

the genocide, Samon lost over thirteen

immediate family members, including his

grandfather, father, three brothers, a sister,

and numerous aunts, uncles, and cousins. One

of those relatives who perished was a cousin,

Heat, who labored at Koh Sla. Heat was 17-

year old when she was assigned to a woman’s

mobile unit at the site. One day, Prum recalls,

Heat ‘was very hungry, so she picked an ear of

corn and cooked it. Before the corn was ready

to eat, the unit chief caught her and gathered

Everyday landscape of violence 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

people around for a meeting. The unit chief

tied her arms in back of her, grabbed the hot

corn from the fire, and put it into her mouth,

burning her. He then declared that Heat had

betrayed theAngkar10 and cooperative. Every-

body at the meeting was threatened to not

follow in her footsteps.’11 Although Heat was

not executed for her ‘crime,’ she would later

become seriously ill and die of starvation.

Since its completion in 1977, the dam and

abutting reservoir continue to be utilized. Long

after the collapse of the Khmer Rouge,

residents have moved to the site; many

newcomers were (and remain) aware of the

tragedy surrounding the dam. And for three

decades the mass grave sites remained unre-

marked, overgrownwith trees and bushes. The

stories of forced work, malnutrition, star-

vation, and executions are mute on the land-

scape—and yet remain vivid in thememories of

those who continue to occupy and work at the

site. The ongoing significance of the site is that

it reveals the everydayness of violence. Most

deaths attributed to this site—and quite

literally thousands of other work sites through-

out the country—were not ‘spectacular’ in the

sense of mass executions. Rather, these deaths

reflected, in Hannah Arendt’s well-worn

phrase, the ‘banality of evil.’ The physical and

social erasure of Koh Sla is testimony to the

contestation ofmemorywithinCambodia. The

lack of commemoration at the Koh Sla site,

accordingly, provides an unmarked memory of

the day-to-day violence that permeated Demo-

cratic Kampuchea; the site is a silent testimony

to the dis-allowal of life that epitomizedKhmer

Rouge rule (Tyner 2012).

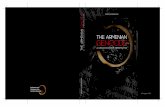

The Kampong Chhnang Airfield

Located near Patlang Village, 60 km north-

west of Phnom Penh, amid sprawling rice

fields and sugar palms is the Kampong

Chhnang Airfield. Covering approximately

300 hectares, the long-abandoned and never-

completed airfield consists of two 2,400m

long runways, a crumbling control tower, and

an administration building (Figure 3).

Plans for the airfield began in late 1975 with

considerable assistance from Chinese advisors

and engineers. The actual construction of the

project, subsequently, began in early 1976.

Forced labor, similar to other projects initiated

by the Khmer Rouge, was to be used. Here,

though, labor consisted of conscripted mem-

bers of the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea

(RAK): actual Khmer Rouge soldiers. It was

determined that suspected ‘bad elements’

within the Khmer Rouge would be forced to

labor at the site. Survivors have testified that

workers were sent there ‘for tempering or

refashioning because of their perceived bad

biographies or supposed links with traitorous

networks.’12

The number of workers varied over time,

ranging from a few hundred in 1976 to more

than 10,000 by 1977. Conditions were

horrendous—not surprising, given that

Khmer Rouge officials intended the workers

to literally work themselves to death. Laborers

worked without any days off; usually for 12-

hour shifts. Food rations andmedical carewere

insufficient. Howmany died at the site remains

unknown. Villagers, however, say that the

stench of decomposing bodies remained for

years after the site was abandoned (Pringle

2011).

There is no placard, no memorial at the site.

There is nothing to explain why an unfinished

airfield lies abandoned in the middle of

farmland. The need for remembrance and

memorialization of the Kampong Chhnang

Airfield, however, is significant, in that it serves

to refute the longstanding historical narrative

of both Democratic Kampuchea and the

12 James A. Tyner et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

Cambodian genocide more broadly. Simply

put, the airfield—concretely—belies the spatial

and temporal bounding of the genocide.

The airfield likewise provides a material

critique of another longstanding mythology of

the Cambodian genocide, namely that the

Khmer Rouge attempted to ‘turn back history’

and recreate a society based on the Angkorian

Empire. Ian Brown (2000: 24), for example, in

an otherwise highly informative book, writes

that the ‘clock was to be turned back to an age

without money, organized education, religion,

and books.’ This is patently wrong. The

Khmer Rouge, in fact, produced their own

currency (though never put into circulation),

imported medicinal supplies from foreign

countries, and published textbooks—includ-

ing two geography texts—to be used through-

out the country (Tyner 2008, 2011, 2012).

This is not to ‘justify’ the actions of the Khmer

Rouge, but rather to emphasize that the goals

and objectives of the Khmer Rouge were to

construct a highly modernized, forward-look-

ing country. A remembrance of the airfield

(and dam site), accordingly, complicates the

standard narrative of the Khmer Rouge regime

as a movement rooted in an anti-modern,

agrarian ideology. It is therefore salient to

consider more in depth the ideological basis of

the Khmer Rouge, in that such an ideology

significantly informs the ongoing ‘will to

remember’ and ‘duty to forget’ approach of

the current government.

The ideological impetus for theKhmerRouge

is detailed in various (albeit frustratingly few)

writings and, indeed, doctoral dissertations of

many of the highest ranking CPK

leadership. Khieu Samphan’s dissertation, for

example, provides a thorough, though slightly

erroneous, exposition of Cambodia’s political

economy.13 Entitled Cambodia’s Economy and

Industrial Development, Khieu Samphan’s

Figure 3 Kampong Chhnang Airfield, Kampong Chhnang Province, Cambodia.

Everyday landscape of violence 13

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

dissertation—although not a template—would

prove highly influential in the subsequent

policies of Democratic Kampuchea. In this

document, Khieu forwarded a series of inter-

related theses. He stated that Cambodia’s

economy was backward, locked in a feudal

and precapitalist mode of production. This

condition, he maintained, resulted from Cam-

bodia’s unequal and dependent integration into

the French colonial economy and the continu-

ance of unfair trade relations. Liberation for

Cambodia’s economy could only occur through

autonomous development, namely a withdra-

wal from the international economy. Lastly, it

was imperative for Cambodia to confront the

existent structural inequity between what he

perceived to be a productive countryside and an

unproductive city (Tyner 2009: 128) .

The Khmer Rouge leadership, in principle,

held that most, if not all, of Cambodia’s

problems were derived from its subordinate

position in an international economic system

thatwas dominated by, among others, theUSA,

China, and France. Consequently, having

violently wrested control of the country, the

CPK leadership sought, rhetorically, to achieve

both total independence and self-reliance for

their fledgling government (Tyner 2009: 128).

In practice, however, Democratic Kampuchea

was far from self-sufficient. Throughout its

existence, the government of Democratic

Kampuchea sought—and achieved—a number

of significant international linkages. Through-

out 1975 and 1976, for example, international

trade flourished between Democratic Kampu-

chea and Thailand: axes, knives, sickles,

plough-tips, and sugar, among other commod-

ities, were all imported under the auspices of

the Khmer Rouge (Kiernan 1996). The Khmer

Rouge also imported sizeable amounts of

medical supplies. Indeed, in late 1976, the

CPK established a trading company, the Hong

Kong-based Ren Fung Company, which facili-

tated the importation of quinine and vitamins

intoDemocraticKampuchea. Furthermore, the

CPK accepted ‘gifts’ from abroad; in 1976, as a

case in point, the Khmer Rouge received

US$12,000 worth of anti-malarial drugs sent

by the American Friends Service Committee—

with Washington’s approval—via China

(Kiernan 1996: 145–146).

As part of decades-long attempt to separate

the genocidal regime of the Khmer Rouge from

both subsequent governments (i.e., the People’s

Republic of Kampuchea) and from other

government involvement and acquiescence, a

public acknowledgment of the Kampong

Chhnang Airfield would cement in place the

role provided by China during the genocide.

More broadly, such an acknowledgmentwould

shatter the longstanding myth that the Khmer

Rouge acted alone. In short, any memorializa-

tion of the airfield would be at odds with the

officially commemoratedTuol Sleng–Choeung

Ek axis.

Ironically, the claims of the CPK leader-

shipmade during the genocide—of promoting a

self-sufficient and isolated government—serve

the present-day interests of China, Vietnam,

and a host of other states (including the USA).

Very few governments have been overly

supportive of the ongoing tribunal—in large

part because few governments want certain

historical ‘facts’ to be made public (Etcheson

2005). Consequently, the international com-

munity is seemingly content to spatially and

temporally restrict the events of the genocide.

And places such as the Kampong Chhnang

Airfield will continue to go unremarked.

Conclusions

Cambodia’s recent history is not determined

by civil war and genocide but rather must be

understood as the result of an ongoing series of

14 James A. Tyner et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

political practices and processes: the commo-

dification of memory; the remembrance of a

violent past; the use of bodies, bones, and

photographs—and a denial of their individual

existence. We see in Cambodia a politics of

memory and an erasure of responsibility; a

situation wherein those responsible are like-

wise rendered unremarked in the name of an

imaginary reconciliation and forgiveness.

As David Chandler (2008: 363) writes,

‘Cambodia seems to have entered a phase of

its history where officially sponsored historio-

graphy of the recent past has become

intrinsically unimportant and irrelevant to

those in power.’

Aside from the pursuit of justice, inter-

national tribunals—as in Cambodia—are

concerned with shaping and reshaping local,

national, and global politics (McCargo 2011:

613). When the government attempts to ‘dig a

hole and bury the past,’ it does so through the

neglect of other buried pits—those containing

the remains of countless victims of mass

violence. The ongoing tribunal, and the

physical manifestation of guilt and innocence

that is displayed in ‘official’ memorials, creates

an illusionary justice that operates through the

simultaneous selling and silencing of genocide.

Howwe remember (or forget) genocide may

serve to eradicate any serious discussion of

responsibility. Officially sanctioned sites, such

as Tuol Sleng and Choeung Ek, solidify

particular narratives of political legitimacy;

they are not directed to locals who have a

personal connection to memory but to the

international travelers who develop a myopic

understanding of the genocide (Sion 2011: 19).

Williams (2004: 248), likewise, cautions that

‘when Tuol Sleng and Choeung Ek are made to

stand for genocide, the focus on killing means

thatwe learn less aboutwhatwas lost. The sites

can hardly communicate a nation whose

educational system, religious and cultural

traditions, economy, social formations, and

family structures were leveled.’

Likewise, we must acknowledge that how

governments choose to remember (or forget)

Cambodia’s genocide has a bearing on our

understanding of contemporary violence in the

country today. As Simon Springer (2009a,

2009b, 2010, forthcoming) cogently argues,

violence—albeit largely of a structural

nature—remains pervasive throughout Cam-

bodia. This is seen, for example, in repeated

forced evictions, homelessness and landless-

ness, HIV/AIDS, and the increased criminali-

zation and incarceration of the poor. However,

as Springer (2009a: 312) explains, many

commentators on contemporary Cambodia

frequently allude to the existence of a ‘culture

of violence’ and premise that violence itself ‘is

considered as forming the very core of the

Cambodian psyche.’ This has profound impli-

cations for a politics of memory, in that

ongoing attempts to commemorate past

violence will reverberate with—and perhaps

obfuscate—violence in the present moment.14

In this paper, we have sought to ‘uncover,’ to

‘make visible,’ other places to counter-balance

the official, state-sanctioned collective mem-

ory of genocide. Neither the reservoir nor the

airfield is explicitly marked or designated on

the landscape; neither site is attributed to the

violence that transpired during the Cambo-

dian genocide. The dam and reservoir are still

in use today; but they remain fixed as sites of

memory for local Cambodians—while unno-

ticed by foreign visitors. The abandoned

airfield likewise serves as an ever-present

symbol of the violence that was perpetrated

so many years ago. But it too is devoid of

public memorialization. It remains, however,

in the collective memory of those who

continue to live and work in the region.

The recovery of unmarked and remarked

sites provides a temporal as well as spatial

Everyday landscape of violence 15

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

corrective to the ongoing narration of the

Cambodian genocide. As evidenced by the Koh

Sla Dam, many infrastructure projects were

initiated in the years leading up to the 17 April

1975 victory of the Khmer Rouge. However,

the ECCC has steadfastly held to an artificial

bounding of the genocide to those events that

transpired between 1975 and 1979. Conse-

quently, those practices of forced labor and

mass death that occurred outside of this time

frame may not necessarily be considered.

We maintain that the absence of designation

or acknowledgment denies the life—and

death—that produced these landscapes. This

systematic process of officially forgetting—or

of burying—the past denies the memories of

millions of Cambodians who, every day, go

about their quotidian lives within these land-

scapes. Both the Sre Lieu mass grave site and

the airfield, along with literally thousands of

other sites, are active memorials; these are sites

of ongoing life and death, as opposed to the

hermetically sealed museum of Tuol Sleng and

the increasingly ‘Disney-fied’ killing fields at

Choeung Ek. Just as Sre Lieu and Kampong

Chhnang have remained hidden in plain sight,

so too has the banal yet far-reaching influence

of the Khmer Rouge—and the global commu-

nity—remained unaddressed. In the process,

such a selective memorialization of the past

continues to dictate the spatial experiences of

millions of Cambodians’ everyday lives.

Notes

1. As one anonymous reviewer correctly notes,

Cambodia was not entirely erased, as it persisted in

the imaginations of many Khmer throughout the

genocide. Conceptually, however, it was imperative

for the Khmer Rouge—from their perspective—to

destroy rather than transform previous institutions

and infrastructures. The reviewer explains, further-

more, that this was ‘the image they [the Khmer Rouge]

attempted to make of themselves, and we do well not

to repeat it.’ We agree in part. While we, in our

writings, should endeavor to not represent the

individual experiences of Cambodians throughout

the genocide (and beyond) as monolithic, we must also

tease apart the particularities of the Khmer Rouge to

understand why certain policies and practices were

pursued. Too often scholars of genocide and mass

violence forward overly simplistic accounts (i.e., Pol

Pot was evil) that render the Khmer Rouge regime

itself as a monolithic entity.

2. When first opened in 1962, the school was called Chao

Ponhea Yat High School. In 1970, it was renamed

Tuol Svay Prey (meaning ‘hillock of the wild mango’).

It was located next to an adjoining primary school,

Tuol Sleng (‘hillock of the sleng tree’). This name was

used to designate the entire compound when it was

converted to the Museum of Genocide Crimes,

perhaps, as Chandler (1999: 4) suggests, because the

sleng tree bears poisonous fruit.

3. Security centers in Democratic Kampuchea were

spatially organized into five levels: subdistrict, district,

regional, zone, and central. It is unknown exactly how

many security centers were in operation; most scholars

estimate the existence of approximately 200 districts,

regional and zonal centers were established. Tuol Sleng

is the only known ‘central’ or highest-level facility.

4. Most accounts continue to claim that 14,000 prison-

ers were killed at S-21, with only seven survivors.

Some estimates continue to place the death toll at over

20,000. However, as the meticulous research of the

Documentation Center of Cambodia (DCCAM) has

detailed, these numbers are in error. The figure of

12,273 is derived from documentation presented at

the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of

Cambodia (ECCC; better known as the ‘Cambodian

tribunal’). Likewise, the purported seven survivors

have been shown to be wrong; archivists at DCCAM

have documented the existence of at least 179

survivors. Interestingly, there is speculation that the

number of seven survivors was promoted by the

Vietnamese to parallel the 7th day of January—the

‘day of victory’ (see Documentation Center of

Cambodia 2011).

5. As of this writing, Hun Sen remains prime minister—a

position he has held since 1985.

6. For a detailed overview of the tribunal (see Ciorciari

and Heindel 2009).

7. His initial sentence of thirty-five years was reduced to

just nineteen years because of time served. In other

16 James A. Tyner et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

words, his sentence was less than one-half a day for

each of the 12,000 deaths associated with Tuol Sleng.

8. Quoted in Rasy (2007); at 18.

9. Interview with lead author, 9 October 2011.

10. Angkar (literally, ‘organization’) refers to the Central

Committee of the Communist Party of Kampuchea

(CPK), the ruling body of the Khmer Rouge.

11. Quoted in Prum (2006); at 45.

12. Cited in Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (2007),

p. 101.

13. Khieu Samphan studied politics and economics at the

University of Sorbonne. He earned his doctoral in

1959.

14. We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for

bringing this important connection to our attention.

It is well-worth pursuing how the unremarking of past

atrocities—the hidden landscapes of violence of which

we write—parallel the unremarking of contemporary

landscapes of violence. Indeed, as the reviewer

suggests it may be that the selective remembrance of

the Cambodia genocide as an apex of violence serves

to render mundane current violent practices. In other

words, how ‘bad’ can the present levels of violence be

when compared to the genocidal violence of the

previous years?

References

Bonacker, T., Form,W. and Pfeiffer, D. (2011) Transitional

justice and victim participation in Cambodia: a world

polity perspective, Global Society 25: 113–136.

Brown, I. (2000) Cambodia. Herndon, VA: Stylus

Publishing.

Chandler, D. (1991) The Tragedy of Cambodian History:

Politics, War, and Revolution since 1945. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press.

Chandler, D. (1999) Voices from S-21: Terror and History

in Pol Pot’s Secret Prison. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Chandler, D. (2000) A History of Cambodia, 3rd ed.

Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Chandler, D. (2008) Cambodia deals with its past:

collective memory, demonization and induced amnesia,

Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 9:

355–369.

Charlesworth, A. (1994) Contesting places of memory: the

case of Auschwitz, Environment and Planning D:

Society and Space 12: 579–593.

Ciorciari, J.D. (2009) History and politics behind the

Khmer Rouge trials, in Ciorciari, J.D. and Heindel, A.

(eds) On Trial: The Khmer Rouge Accountability

Process. Phnom Penh: Documentation Center of

Cambodia, pp. 33–84.

Ciorciari, J.D. and Heindel, A. (2009) On Trial: The

Khmer Rouge Accountability Process. Phnom Penh:

Documentation Center of Cambodia.

De Walque, D. (2005) Selective mortality during the

Khmer Rouge period in Cambodia, Population and

Development Review 31: 351–368.

Documentation Center of Cambodia (2011) Fact Sheet:

Pol Pot and His Prisoners at Secret Prison S-21. Phnom

Penh: Documentation Center of Cambodia.

Dwyer, O.J. (2004) Symbolic accretion and commemora-

tion, Social & Cultural Geography 5: 419–435.

Dwyer, O.J. and Alderman, D.H. (2008) Memorial

landscapes: analytic questions and metaphors, Geo-

Journal 73: 165–178.

Ea, M.-T. (2005) The Chain of Terror: The Khmer Rouge

Southwest Zone Security System. Phnom Penh: Docu-

mentation Center of Cambodia.

Edensor, T. (2005) The ghosts of industrial ruins: ordering

and disordering memory in excessive space, Environ-

ment and Planning D: Society and Space 23: 829–849.

Etcheson, C. (2005) After the Killing Fields: Lessons from

the Cambodian Genocide. Lubbock: Texas Tech

University.

Foote, K. (1997) Shadowed Ground: America’s Land-

scapes of Violence and Tragedy. Austin: University of

Texas Press.

Forest, B., Johnson, J. and Till, K.E. (2004) Post-

totalitarian national identity: public memory in

Germany and Russia, Social & Cultural Geography 5:

357–380.

Heuveline, P. (1998) ‘Between one and three million’:

towards the demographic reconstruction of a decade of

Cambodian history (1970–1979), Population Studies

52: 49–65.

Hoelscher, S. and Alderman, D.H. (2004) Memory and

place: geographies of a critical relationship, Social &

Cultural Geography 5: 347–355.

Hughes, R. (2003) The abject artefacts of memory:

photographs from Cambodia’s genocide, Media,

Culture and Society 25: 23–44.

Hughes, R. (2008) Dutiful tourism: encountering the

Cambodian genocide, Asia Pacific Viewpoint 49:

318–330.

Jedlowski, P. (2001) Memory and sociology: themes and

issues, Time and Society 10: 29–44.

Everyday landscape of violence 17

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

Johnson, N. (1995) Cast in stone: monuments, geography,

and nationalism, Environment and Planning D: Society

and Space 13: 51–65.

Kiernan, B. (1985) How Pol Pot Came to Power: A

History of Communism in Kampuchea, 1930–1975.

London: Verso.

Kiernan, B. (1996) The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and

Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975–

1979. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The Production of Space (translated

by D. Nicholson-Smith). Oxford: Blackwell.

Light, D. and Young, C. (2010) Political identity, public

memory and urban space: a case study of Parcul Carol,

Bucharest from 1906 to the present, Europe-Asia

Studies 62: 1453–1478.

Mam, K. (2004) The endurance of the Cambodian family

under the Khmer Rouge regime: an oral history, in

Cook, S.E. (ed.) Genocide in Cambodia and Rwanda:

New Perspectives. New Haven, CT: Yale Center for

International and Area Studies, pp. 127–171.

McCargo, D. (2011) Politics by other means? The virtual

trials of the Khmer Rouge tribunal, International Affairs

87: 613–627.

McIntyre, K. (1996) Geography as destiny: cities, villages

and Khmer Rouge Orientalism, Comparative Studies in

Society and History 38: 730–758.

Munyas, B. (2008) Genocide in the minds of Cambodian

youth: transmitting (hi)stories of genocide to second and

third generations in Cambodia, Journal of Genocide

Research 10: 413–439.

Nora, P. (1989) Between memory and history: les lieux de

memoire, Representations 26: 7–25.

Office of the Co-Investigating Judges (2007) Closing

Order, Case File No.: 002/19-09-20007-ECCC-OCIJ.

Phnom Penh: Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of

Cambodia.

Pringle, J. (2011) Pol Pot’s abandoned airport, Asia

Sentinel, www.asiasentinel.com (accessed 5 January

2012).

Prum, S. (2006) A wish to see the Khmer Rouge tribunal,

Searching for the Truth 3rd Quarter: 44–47.

Quinn, K.M. (1989) The pattern and scope of violence, in

Jackson, K.D. (ed.) Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous

with Death. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press,

pp. 179–208.

Rasy, P. (2007) Discovery of the Sre Lieu mass grave,

Searching for the Truth (Second Quarter): 17–19.

Renan, E. ([1882] 1995) What is a nation, in Dahbour, O.

and Ishay, M.R. (eds) The Nationalism Reader. Atlantic

Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, pp. 143–155.

Ricoeur, P. (2000) LaMemoire, L’Historie L’Oublie. Paris:

Seuil.

Shawcross, W. (2002) Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon, and the

Destruction of Cambodia, rev. ed. New York: Cooper

Square Press.

Sion, B. (2011) Conflicting sites of memory in post-

genocide Cambodia, Humanity: An International

Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and

Development 2(1): 1–21.

Springer, S. (2009a) Culture of violence or violent

Orientalism? Neoliberalisation and imagining the

‘savage other’ in post-transitional Cambodia, Trans-

actions of the Institute of British Geographers 34:

305–319.

Springer, S. (2009b) Violence, democracy, and the

neoliberal ‘order’: the contestation of public space in

posttransitional Cambodia,Annals of the Association of

American Geographers 99: 138–162.

Springer, S. (2010) Neoliberal discursive formations: on

the contours of subjectivation, good governance, and

symbolic violence in posttransitional Cambodia,

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28:

931–950.

Springer, S. (forthcoming) Violent accumulation: a

postanarchist critique of property, dispossession, and

the state of exception in neoliberalizing Cambodia,

Annals of the Association of American Geographers.

Till, K.E. (2004) Political landscapes, in Duncan, J.S.,

Johnson, N.C. and Schein, R.H. (eds) A Companion to

Cultural Geography. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 347–364.

Till, K.E. (2005) The New Berlin: Memory, Politics, Place.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Tyner, J.A. (2008) The Killing of Cambodia: Geography,

Genocide and the Unmaking of Space. Aldershot:

Ashgate.

Tyner, J.A. (2009)War, Violence, and Population: Making

the Body Count. New York: The Guilford Press.

Tyner, J.A. (2010) Military Legacies: A World Made by

War. New York: Routledge.

Tyner, J.A. (2011) Genocide as reconstruction: the

political geography of Democratic Kampuchea, in

Kirsch, S. and Flint, C. (eds) Reconstructing Conflict:

Integrating War and Post-War Geographies. Aldershot:

Ashgate, pp. 49–66.

Tyner, J.A. (2012) Genocide and the Geographical

Imagination: Life and Death in Germany, China, and

Cambodia. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield.

Williams, P. (2004) Witnessing genocide: vigilance and

remembrance at Tuol Sleng and Choeung Ek,Holocaust

and Genocide Studies 18: 234–254.

18 James A. Tyner et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012

Abstract translations

La memoire et le paysage quotidien de la violenceau Cambodge apres le genocide

Cet article aborde la politique de la memoire auCambodge apres le genocide. Au pays le genocidefut commemore de maniere selective depuis 1979,avec deux sites qui recoivent une commemorationofficielle: le Musee des Crimes Genocidaires de TuolSleng et les terrains d’execution a Choeung Ek. Legenocide n’a pas pourtant ete limite a ces deux sites.A partir d’une etude de cas de deux sites nonmarques – la fosse commune Sre Lieu a Koh SlaDam et l’aerodrome Kampong Chhanang – noussoulignons l’importance primaire de prendre auserieux les sites de violence qui n’ont pas encorerecu une commemoration officielle. Nous affirmonsque l’histoire du genocide du Cambodge, ainsi queles tentatives de promouvoir la justice transition-nelle, devraient rester conscientes du processus parlequel les memoires et les memoriels se transfor-ment en ressources politiques. Nous proposons enparticuliere que les sites non marques de la violencedu passe puissent fournir un apercu critique sur noscomprehensions contemporaines de la politique dusouvenir et de l’oubli.

Mots-clefs: paysage, memoire, commemoration,violence, Cambodge.

Memoria y el Paisaje Cotidiano de Violencia en

Camboya despues del Genocidio

Este artıculo se trata a la polıtica de memoria en

Camboya despues del genocidio. Desde 1979

genocidio ha sido conmemorado selectivamente en

el paıs, con dos sitios recibiendo conmemoracion

oficial: el Museo Tuol Sleng de Crimenes de

Genocidio y los campos de matanza de Choeung

Ek. Sin embargo, el genocidio de Camboya no fue

limitado a estos dos sitios. A traves un caso practico

de dos sitios sin nombre – la fosa comun de Sre Lieu

en Koh Sla Dam y el Aerodromo de Kampong

Chhnang – destacamos la prominencia, y significa-

tivo, de tomar en cuenta estos sitios de violencia que

no han recibido conmemoracion oficial. Discutimos

que la historia del genocidio en Camboya, tambien

como intentos promover justicia transnacional,

deben pertenezcan conscientes de como las memor-

ias y conmemorativos llegan a ser recursos polıticos.

Particularmente, sostenemos que un enfoque en los

sitios sin nombre de violencia del pasado proveen

una perspicacia critica a nuestros entendimientos

contemporaneos de la polıtica de recordar y olvidar.

Palabras claves: paisaje, memoria, conmemoracion,

violencia, Camboya.

Everyday landscape of violence 19

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

KSU

Ken

t Sta

te U

nive

rsity

] at

08:

42 3

1 O

ctob

er 2

012