Managing the protection of innovations in knowledge-intensive business services

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Managing the protection of innovations in knowledge-intensive business services

Research Policy 37 (2008) 1530–1547

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Research Policy

journa l homepage: www.e lsev ier .com/ locate / respol

Managing the protection of innovations in knowledge-intensivebusiness services

Nabil Amaraa,∗, Réjean Landrya,1, Namatié Traoréb,2

a Department of Management, Faculty of Business, Laval University, Québec City, QC, Canada G1V 0A6b Regulatory, Legislative and Economic Affairs Division, Programs and Policy Branch, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 59 Camelot Drive, Ottawa, ON,Canada K1A 0Y9

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Received 13 July 2007Received in revised form 10 June 2008Accepted 1 July 2008Available online 22 August 2008

Keywords:Protection methods of intellectual propertyKIBSCorrelation approachComplementarityMultivariate Probit regression

a b s t r a c t

How do knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) protect their inventions from imita-tion by rival firms when choosing among various protection mechanisms? Data from the2003 Statistics Canada Innovation Survey on services are used to investigate this issue bylooking into complementarities, substitution and independence among eight protectionmechanisms. A Multivariate Probit (MVP) model is estimated to take into account the factthat KIBS simultaneously consider many alternative intellectual property (IP) protectionmethods when they attempt to protect their innovations. Results show that patents, regis-tration of design patterns, trademarks, secrecy and lead-time advantages over competitorsconstitute legal and informal methods that are used jointly. These complementarities sug-gest that IP protection mechanisms that are interdependent and reinforce each other toprotect innovations from imitation by rival firms constitute a pattern on which firms rely

to protect their innovations from imitation. A second pattern is based on the fact that KIBSrely on patents and complexity of designs as substitutes, and tend to use registration ofdesign patterns and complexity of designs as substitutes in protecting their innovationsfrom imitation. A third emerging pattern concerns protection mechanisms that are inde-pendent from each other and exhibit no synergy, and do not reinforce each other to protectmitatio

innovations from i1. Introduction

Knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) provideservices based on professional knowledge. In that indus-

try, transactions consist of knowledge and outputs areoften intangible. Innovations result more often from newcombinations of knowledge rather than from new combi-nations of physical artefacts. Moreover, as pointed out by∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 418 656 2131x4382;fax: +1 418 656 2624.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (N. Amara),[email protected] (R. Landry), [email protected](N. Traoré).

1 Tel.: +1 418 656 2131x3523; fax: +1 418 656 2624.2 Tel: +1 613 221 3039; fax: +1 613 221 3056.

0048-7333/$ – see front matter © 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.07.001

n by other firms.© 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Blind et al. (2003), business services are heterogeneous,and the knowledge content of the services provided is verydiverse and often not easy to protect effectively with formalintellectual property protection methods such as patents.Intangibility is one of the attributes of service innovationsthat makes them easier to imitate. In such a context ofthreat of imitation, how can firms capture the value fromtheir innovative activities? More specifically, how do KIBSmanage the protection of their innovations from imitationwhen choosing among various intellectual property (IP)protection methods?

The aim of this paper is two-fold. First, complementar-ities and substitutions between various forms of legal andinformal IP protection mechanisms are studied in order tosee how KIBS mix IP protection mechanisms to protect theirinnovations. Second, heterogeneities in the determinants

ch Policy

oipdI

2

otmpLssaBteasm

otfpisttidtfiooar

nibfiaeTaciTPsKE(tsao

N. Amara et al. / Resear

f KIBS are explored in choosing among eight legal andnformal IP protection mechanisms. Studying these com-lementarities and substitutions in combination with theireterminants can provide insights into the use of mixes of

P protection mechanisms by KIBS.

. Contribution of the paper

Previous studies on IP protection methods have focussedn the use of patents and secrecy by large firms and high-ech manufacturing firms. The use of other IP protection

ethods and the question of how firms mix various IProtection methods have received much less attention.ikewise, studies on the use of IP protection methods byervice firms are still scanty. Lack of empirical evidence istill prevalent about IP protection of innovation across KIBSnd KIBS sectors (Miles et al., 2000; Miles and Boden, 2000;lind et al., 2003; Salter and Tether, 2006). This paper aimso fill this gap by looking at a sample of KIBS operating inngineering consulting services, computer system designnd management consulting services. The ultimate aim is tohed light on how they mix legal and informal IP protectionethods to protect their innovations from imitation.Prior studies usually focussed on particular inventions

r innovations as their unit of analysis, and thus attemptedo identify which protection method is the most efficientor a particular invention. This approach is only appro-riate if one assumes that firms have no more than one

nvention at any given point in time. The fact that firmsimultaneously develop multiple inventions induces themo rely concurrently on several protection methods in ordero appropriately protect different components of thesenventions (Levin et al., 1987; Arundel, 2001). This studyoes not attempt to match particular inventions to par-icular protection methods. Instead, it focusses on howrms combine several methods to protect their portfoliof inventions and innovations. The different combinationsn which firms rely represent different protection patternsbout how KIBS manage competition when imitation fromivals matters.

While prior studies have examined the determi-ants of the use of various IP protection mechanisms

n separate models, this paper uses a Multivariate Pro-it (MVP) model to reflect the fact that in practice,rms simultaneously consider the use of various mech-nisms. The Multivariate Probit model includes eightquations estimating eight IP protection mechanisms.he eight IP protection methods included in this studyre patents, registration of design patterns, trademarks,opyrights, confidentiality agreements, secrecy, complex-ty of designs, and lead-time advantages over competitors.he explanatory variables included in the Multivariaterobit model are the types of innovations, R&D inten-ity, knowledge-development strategies (KDSI), Externalnowledge-Sharing with Research Organizations (EKSRO),xternal Knowledge-Sharing With Market Organizations

EKSMO), internal knowledge-sharing (IKS), types of indus-ry, being a subsidiary, export and size of firms. Byimultaneously considering eight protection mechanismsnd their determinants, this paper contributes to shed lightn how KIBS combine different protection mechanisms into37 (2008) 1530–1547 1531

bundles likely to protect their innovations from imitationby rival firms.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. First arereviewed the arguments about the conditions under whichvarious protection mechanisms are efficient in protectinginnovations developed by KIBS. Second, information is pro-vided about the data and descriptive statistics. Third, theestimation results are discussed and the paper concludeswith a discussion of implications of the results for firm IPprotection patterns.

3. Why do KIBS attempt to protect their innovationsby using various methods?

The literature about the protection of innovations dealsmostly with the protection of technological innovationscommercialized by manufacturing firms. Inventions andtechnological innovations developed by firms are consid-ered valuable knowledge and intellectual property thatneed to be protected by various methods in order to cap-ture their benefits. This is an important issue for innovatingcompanies because the speed of imitation has a bearingupon the durability of a firm’s competitive advantage (Hilland Jones, 2001; Porter, 1996). Protecting these inventionsand innovations represents an important barrier to imita-tion as it makes it difficult for competitors to copy a firm’sdistinctive competencies. Therefore, the better the protec-tion, the greater the barriers to imitation, and the moresustainable a company’s competitive advantage (Reed andDeFillippi, 1990).

According to Howells et al. (2003), these argumentsdo not adequately explain the propensity of KIBS to pro-tect their innovations because the service sector operatesunder a larger variety of “knowledge regimes”. Their con-ceptual framework suggests that appropriability in servicesdepends upon two primary explanatory variables, namely,the degree of codification of knowledge and the degree oftangibility of service outputs. They hypothesise that patentsare better suited to capture the profits from service inno-vations when these services are characterized by a highdegree of knowledge codification and output tangibility(Miles, 2008). This would include Computer System DesignServices. The purpose of patent law is to promote techni-cal advances by protecting the profits that may result fromthe commercialization of patented inventions and techno-logical innovations (Blind et al., 2006; Encaoua et al., 2006;Hanel, 2006). In theory, patents provide the legal right toexclude other firms from making, using, selling, or import-ing an invention or innovation. However, the legal right toexclude does not automatically lead to exclusion (Walsh,2007). In fact, contrary to traffic regulation, the govern-ment does not get involved in enforcing exclusion rights.As a general rule, the protection of patents is left to the IPowners. Overall, the protection of inventions and innova-tions by using patents is more challenging for KIBS thanfor manufacturing firms. This is because (i) innovations are

more intangible in the service sector than in the manufac-turing industry, and (ii) it is more difficult to enforce thelegal right to exclude imitators in the former than in thelatter (Andersen and Howells, 2000). Therefore, one canhypothesise that:1532 N. Amara et al. / Research Policy 37 (2008) 1530–1547

priabili

Fig. 1. Knowledge regimes and approHypothesis 1. KIBS that provide service innovationsinvolving codified knowledge in combination with tangibleoutputs are more likely to complement the use of patentsby relying on other legal mechanisms such as copyrights,trademarks and confidentiality agreements (Fig. 1).

Conversely, Howells et al. (2003) hypothesise that forservices which are based on tacit knowledge, while intan-gible in form, the protection of innovations from imitationcan be obtained by protecting the firm’s trade nameand by relying on informal protection mechanisms suchas secrecy and confidentiality agreements. This wouldinclude Management Consulting Services. Therefore, onecan hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 2. KIBS that provide service innovationsinvolving tacit knowledge in combination with intangi-ble outputs are more likely to rely on informal protectionmechanisms such as secrecy, complexity of design, lead-time advantage on competitors as their primary protectionmechanisms, and they complement them by relying onconfidentiality agreements and trademarks.

Howells et al. (2003) also develop hypotheses for theother two intermediary cases. In the first intermediarycase where the services provided are embodied in cod-ified knowledge in combination with intangible outputs,they hypothesise that copyrights are the most applica-ble protection mechanism. Registration of design patternsand trademarks are also well suited to protect innovations

developed under this knowledge regime. This case wouldinclude Engineering Consulting Services when the servicesprovided are characterized by codified information in com-bination with outputs such as blueprints and technicalspecifications. Therefore, one can hypothesise that:ty of benefits of service innovations.

Hypothesis 3. KIBS that provide service innovationsinvolving codified knowledge in combination with intan-gible outputs are more likely to rely on copyrights thatare used as the primary protection mechanism, and tocomplement them with trademarks and confidentialityagreements.

Finally, Howells et al. (2003, p. 51) hypothesise thatwhen tacit knowledge is involved in combination with tan-gible outputs, “. . . no direct protection measures are used,as innovation activity and intellectual property generationare extremely low”. In such a knowledge regime, KIBS maybe induced to rely on lead-time advantages over competi-tors and complexity of designs instead of relying on legalmechanisms. For example, they may attempt to shorten theinnovation cycle by decreasing lead-times enough so thatby the time a rival firm attempts to imitate the innovation,it is too late (Andersen and Howells, 2000). Therefore, onecan hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 4. KIBS that provide service innovationsinvolving tacit knowledge in combination with tangibleoutputs are more likely to rely on informal protec-tion mechanisms such as secrecy, complexity of design,lead-time advantage on competitors, and to complementthem with the use of confidentiality agreements andtrademarks.

To sum up, given the knowledge regimes under whichservices are provided and the limitations of patents, KIBSmay be inclined to protect their innovations from imita-

tion through a combination of legal mechanisms, includingpatents, trademarks, registration of design patterns andcopyrights (Andersen and Howells, 2000). This rationalesuggests that legal mechanisms are not mutually exclu-sive (the substitution hypothesis), but are complementarych Policy

ai(eaploeKamspto

phcpnmthetan

bpiamt2qc(T

oeapifooslsp(tt

the

N. Amara et al. / Resear

nd mutually reinforce each other (the complementar-ty hypothesis). Similarly, as suggested by Howells et al.2003), informal protection mechanisms may be consid-red as supplementing the legal mechanisms used to covernd to strengthen the protection of innovations for com-onents not covered by legal mechanisms. For example,

icense agreements under patents usually include the usef knowledge protected by patents and the use of knowl-dge protected by trade secrets. According to Jorda andaeschke (2007, p. 64): “. . . licenses under patents withoutccess to associated or collateral know-how have little com-ercial value because patents rarely disclose the ultimate

caled-up commercial embodiments.” Therefore, informalrotection mechanisms may be considered as complemen-ary to legal mechanisms because they provide synergy andptimise the use of legal mechanisms.

Furthermore, the complementarity hypothesis com-etes with the substitution hypothesis. The substitutionypothesis rests on the idea that KIBS are resource-onstrained and therefore, investments of resources inrotecting their innovations through legal mechanisms,otably through patents, come at the expense of invest-ents in the use of informal mechanisms, more likely at

he expense of trade secrets and lead-times. Following thisypothesis, KIBS are expected to invest their resources andfforts on those mechanisms that provide the best pro-ection for their innovations. The substitution hypothesisssumes that protection mechanisms are separate and doot reinforce each other.

Studies dealing with manufacturing firms and science-ased firms have investigated complementarity betweenatents and secrecy (Arora, 1997). Those looking into var-

ous protection methods have focussed on the importancend the effectiveness of patents, compared to informalethods to protect inventions and technological innova-

ions (König and Licht, 1995; Levin et al., 1987; Arundel,001; Hanel, 2001). Very few studies have examined theuestion of how several protection methods are used inomplementarity to prevent imitation from competitorsCohen et al., 2000; Arundel, 2001; Hanel, 2001; Blind andhumm, 2004; Landry et al., 2006).

A pioneering study conducted by Miles et al. (2000)n the protection of innovation has independently consid-red the level of use of copyrights, design rights, patentsnd trademarks by KIBS. A factor analysis study of thereferences of 65 service firms from many sectors, includ-

ng business services, showed that service firms rely onour combinations of mechanisms, the first being a mixf patents, trademarks and copyrights; the second, a mixf secrecy, lead-time advantages and customer relation-hip management. A third combination concerns bundlingong-term labour contracts and exclusive contracts withuppliers; finally, a fourth mix concerns combining com-lex product design and embodying intangible productsBlind et al., 2003, p. 81). To the extent of our knowledge,his study is the first to specifically explore the complemen-

ary and substitution hypotheses regarding KIBS.To sum up, there is no definitive theoretical answer tohe complementarity and substitution issues. Thus, theyave to be addressed at the empirical level. As statedarlier, this study takes into account eight protection mech-

37 (2008) 1530–1547 1533

anisms that KIBS may use to protect their innovationsfrom imitation by rivals. These methods, which are thedependent variables in our study, are: patents, registrationof design patterns, trademarks, copyrights, confidentialityagreements, secrecy, complexity of designs, and lead-timeadvantages over competitors. They are all binary variablesequalling one if, between 2001 and 2003, the firm used themethod, and 0 otherwise.

Empirical evidence based on innovation surveys sug-gests that manufacturing firms tend to rely more frequentlyon secrecy than on patents to protect their inventions andinnovations (Levin et al., 1987; Rausch, 1995; Cohen et al.,1998; Arundel et al., 1995; Harabi, 1995; McLennan, 1995;Arundel, 2001; Cohen et al., 2000; Baldwin, 1997; Baldwinand Hanel, 2001; Hanel, 2001). By comparison to the con-ceptual framework developed by Howells et al. (2003),which explains the use of different protection methodswith the variables degree of knowledge codification and thedegree of output tangibility, the empirical literature dealingwith the manufacturing sector suggests that five categoriesof factors can be used to explain why firms rely on differ-ent protection methods. These are: (1) R&D intensity; (2)knowledge strategies; (3) types of innovations; (4) indus-tries; and (5) control variables such as being a subsidiary,export and firm size. In this study on KIBS, the variableknowledge will be taken into account by using indicatorsrelated to the knowledge strategies implemented by KIBS,while the variable output tangibility will be considered byincluding various sectors in the list of explanatory variables,as did Howells et al. (2003) in their conceptual framework.We will now review the link between this conceptual andempirical literature, and the explanatory variables includedin the regression models.

3.1. R&D intensity

Increasing R&D intensity likely contributes to augmentthe degree of codification of knowledge. Services that areassociated with more codified forms of knowledge pro-duction are more likely to rely on patents to protect theirinnovations (Howells et al., 2003). Furthermore, invest-ments in R&D could contribute to increase the number ofpatentable inventions (Arundel, 2001; Blind et al., 2006)and inventions that justify the registration of designs pat-terns (Arundel, 2000). These hypotheses are extended toKIBS.

Hypothesis 5. The higher the R&D intensity, the higherthe likelihood that KIBS rely on patents to protect theirinnovations from imitation by competitors.

Hypothesis 6. The higher the R&D intensity, the higherthe likelihood that KIBS rely on the registration of designpatterns to protect their innovations from imitation bycompetitors.

In this paper, a firm’s R&D intensity (SrRD) is measured

as the percentage of full-time employees in its business unitwho were involved in R&D activities in 2003. This variablewas matched with the normal distribution using a squareroot transformation. Such an operationalization is espe-cially appropriate for KIBS, given that in this type of firm,ch Policy

1534 N. Amara et al. / ResearR&D rests more on investments in knowledge employeesthan on equipment.

3.2. Firm’s knowledge-management strategies

Strategy refers to a set of decisions and actions thataim to give the firm a superior performance and ulti-mately a competitive advantage over rivals (Porter, 1996).Developing a strategy helps a firm to better understandwhat to do, what to become and how to plan to getthere. A strategy defines the scope of a firm’s intentions,in particular in relation to the protection of inventionsand technological innovations. Firms without strategy reactto short-term opportunities without achieving medium-and long-term goals (Miles and Snow, 1978). Knowl-edge is the most significant resource required in theproduction of knowledge-intensive-based services. There-fore, KIBS firms have to develop explicit strategies forthe management of their knowledge resources (Leiponen,2006). In this paper, we hypothesise that KIBS witha knowledge-management strategy react to competitivechallenges by investing in four categories of knowledge-management strategies: knowledge-development, Exter-nal Knowledge-Sharing with Research Organizations,External Knowledge-Sharing With Market Organizations,and internal knowledge-sharing. Such planned invest-ments could contribute to increase the pool of codifiedknowledge (Howells et al., 2003) and, as a conse-quence, the number of patentable inventions (Brouwerand Kleinknecht, 1999; Arundel, 2001). Therefore, one mayhypothesise that:

Hypothesis 7. The larger the investments in knowledge-development, External Knowledge-Sharing with ResearchOrganizations, External Knowledge-Sharing With MarketOrganizations, and internal knowledge-sharing strategiesare, the higher the likelihood that KIBS rely on patents toprotect their innovations from imitation by competitors.

Knowledge-development strategies refer to incen-tives provided by KIBS to encourage their employees toincrease their knowledge base. In this paper, knowledge-development strategies was measured by using a five-itemindex assessing the importance of the following factors forthe firm: (1) encouraging experienced workers to trans-fer their knowledge to new or less experienced workers;(2) encouraging workers to continue their education byreimbursing tuition fees for successfully completed work-related courses; (3) offering off-site training to workers inorder to keep skills current; (4) using teams which bringpeople with different skills together; and (5) encourag-ing risk-taking initiatives by employees. For each successfactor, the respondent was asked to rate its degree of impor-tance using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (low importance)to 5 (high importance). The sum of the response scoresfor the five factors, which initially ranged from 5 to 25,

was weighted in order to take into account “not rele-vant” answers. Thus, for each respondent, the sum of thescore was divided by the number of applicable items. Eventhough the initial index has integer values from 1 to 5, onceweighted, it can take on non-integer values.37 (2008) 1530–1547

In their search for new ideas, KIBS can rely, as wehave seen, on internally focussed knowledge-developmentstrategies that draw attention to the development of theiremployees’ knowledge base. Alternatively, as shown byLaursen and Salter (2004, 2006), innovative firms can lookfor new ideas by adopting open search strategies thatinvolve the use of external actors, and sources of ideasand information to develop or improve their products orprocesses. Laursen and Salter (2004, p. 1204) have charac-terized the openness of firms “by the number of differentsources of external knowledge that each firm draws upon inits innovative activities.” We hypothesise that KIBS that aremore open to external sources of ideas are more likely toincrease their pool of codified and tacit knowledge that mayincrease their capabilities to arrive at new combinations ofknowledge, and thus the generation of tangible and intan-gible innovations that need to be protected from imitationthrough the recourse to both legal and informal protec-tion mechanisms. In this paper, openness was measured byusing indicators of knowledge-sharing with two categoriesof external sources of ideas and information.

External Knowledge-Sharing with Research Organiza-tions was measured by using a four-item index regardingthe importance of the role played, between 2001 and 2003,by the following four research organizations as sources ofinformation needed for suggesting or contributing to thedevelopment of KIBS’ new or significantly improved prod-ucts or processes: (1) universities or other higher educationinstitutes; (2) federal government research laboratories;(3) Provincial/territorial government research laboratories;and (4) private non-profit research laboratories. For eachsource of information, the respondent was asked to rate itsdegree of importance using a 5-point scale ranging from1 (low importance) to 5 (high importance). The sum of theresponse scores for the four sources, which initially rangedfrom 4 to 20, was weighted in order to take into account“not relevant” answers. Thus, for each respondent, the sumof the score was divided by the number of applicable items.Even though the initial index has integer values from 1 to5, once weighted, it can take on non-integer values.

External search that involves research sources of ideasand information may help KIBS to exploit innovative oppor-tunities. Increasing the variety and importance of researchsources may increase the validation of exploitable inno-vation opportunities. On the other hand, external searchthat involves market sources of ideas and information mayhelp KIBS to explore innovative opportunities located intheir business environment. Similarly, increasing the vari-ety and importance of market sources may improve thevalidation of explorative innovation opportunities. ExternalKnowledge-Sharing With Market Organizations was mea-sured by using a four-item index regarding the importanceof the role played, between 2001 and 2003, by the follow-ing four market organizations as sources of informationneeded for the firm’s innovation activities: (1) suppliersof software, hardware, materials, or equipment; (2) clients

or customers; (3) consultancy firms; and (4) competitorsand other enterprises from the same industry. The estab-lishments were asked, in the Statistics Canada survey, torate the importance of these four sources of informationfor the firm’s innovation activities, using a 5-point scalech Policy

rAwi

tpiidroiic

bcrdifpLtET7iEt6owv

swtwfifn(0c

3

ttpeItptmi

N. Amara et al. / Resear

anging from 1 (low importance) to 5 (high importance).s for the previous index, the sum of the response scoresas weighted. Thus, the weighted index can take on non-

nteger values from 1 to 5.Internal knowledge-sharing was measured by using a

hree-item index regarding the importance of the rolelayed, between 2001 and 2003, by the following three

nternal sources of information needed for the firm’snnovation activities: (1) sales and marketing staff; (2) pro-uction staff; and (3) management staff. The firms were toate the importance of these three sources of informationn a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (low importance) to 5 (high

mportance). Based on the same logic as the previous twondices, the weighted index of internal knowledge-sharingan take on non-integer values from 1 to 5.

Mindful of the fact that the last four indices wereased on multiple-item scales, we conducted a Prin-ipal Components Factor Analysis (PCFA) with Varimaxotation (PCFA) on the construct scales to assess their uni-imensionality. For the knowledge-development strategies

ndex (KDSI), the results of the PCFA indicated that oneactor explained 66.92% of the original variance of thehenomenon studied, with an initial Eigenvalue of 2.36.ikewise, a PCFA was performed on the construct scaleso assess the unidimensionality of the index capturing thexternal Knowledge-Sharing with Research Organizations.he results of this PCFA indicated that one factor explained0.23% of the original variance of the phenomenon stud-ed with an initial Eigenvalue of 2.81. For the index of thexternal Knowledge-Sharing With Market Organizations,he results of the PCFA showed that one factor explained5.14% of the original variance with an initial Eigenvaluef 1.75. Finally, for the Internal Knowledge-Sharing Index,e found that one factor explained 59.24% of the original

ariance with an Eigenvalue of 1.75.Once the unidimensionality of the additive scales mea-

uring these four indices based on multiple-item scalesas established, the Chronbach’s Alpha was used to obtain

heir reliability coefficients. The Chronbach’s Alpha scoreas 0.71 for KDSI, 0.87 for EKSRO, 0.67 for IKS and 0.55

or EKSMO. These values of the Alpha coefficients are sat-sfactory for the first three indices and rather low at 0.55or EKSMO. It must be pointed out that although there iso strict threshold for high reliability, Ahire and Devaraj2001), and Nunally (1978) recommended the threshold of.50 for emerging construct scales and 0.70 for maturingonstructs (see Table A1 for more details).

.3. Product and process innovations

Product and process innovation may differ in rela-ion to their degree of knowledge codification and outputangibility. Inspired by Miles (2008), we assume thatroduct innovations may involve higher degrees of knowl-dge codification and tangibility than process innovations.f this assumption is correct, the logic of our concep-

ual framework suggests that legal mechanisms, especiallyatents, would be better suited to protect product innova-ions than process innovations, while informal protectionechanisms would be better suited to protect processnnovations. Based on this rationale, we hypothesise that:

37 (2008) 1530–1547 1535

Hypothesis 8. KIBS are more likely to attempt to pro-tect their product innovations through patents rather thaninformal protection mechanisms, and conversely, morelikely to protect their process innovations through informalrather than legal protection mechanisms.

In this paper, types of innovation were measured witha series of binary variables defined as follows: PRODU isa binary variable coded 1 if, between 2001 and 2003, thefirm introduced onto the market only new or significantlyimproved products and did not introduce new or signif-icantly improved processes, and 0 otherwise; PROCE is abinary variable coded 1 if, between 2001 and 2003, thefirm introduced onto the market only new or significantlyimproved processes and did not introduce new or signifi-cantly improved products, and 0 otherwise. Finally, SIMULTis a binary variable coded 1 if, between 2001 and 2003, thefirm simultaneously introduced onto the market new orsignificantly improved products and processes, and 0 oth-erwise. This last category of firms was used as the referencecategory in the regression model.

3.4. Industries

Survey research shows that a firm’s propensity to relyon legal protection mechanisms varies across industries(Cohen et al., 2000; Levin et al., 1987; Arundel, 2000, 2001;Somaya, 2004). Studies on innovation tend to suggest thatknowledge becomes highly idiosyncratic at the firm level,and that industries significantly differ with respect to theirknowledge base and knowledge absorptive capabilitiesand, therefore, their innovation capabilities. Industries thatrely heavily on professional knowledge, like KIBS, providea very fruitful terrain to test this hypothesis. Following, wehave differentiated the traditional professional service KIBSfrom the technology-based KIBS. The first group providesservices based on specialized knowledge of administrativesystems and social affairs, while the second group of firmsprovides services linked to technology, and the produc-tion and transfer of technological innovations. Innovationsdeveloped by technology-based KIBS involve more codi-fied knowledge and more tangible outputs that are likelyeasier to protect with legal protection mechanisms, espe-cially patents (Miles, 2008). Conversely, service innovationsproduced by traditional professional service KIBS involvedegrees of tacit knowledge and degrees of intangible out-puts that are more suited for the use of informal protectionmechanisms linked to secrecy and legal mechanisms suchas confidentiality agreements (Miles et al., 2000). There-fore, one may hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 9. Technology-based KIBS are more likely toattempt to protect their innovations by relying on patentsrather than on informal mechanisms, and conversely, tra-ditional professional service KIBS are more likely to protecttheir innovations by relying on informal rather than on legalprotection mechanisms.

To test these hypotheses, one type of traditional pro-fessional service KIBS (Management Consulting Services)and two types of new technology-based KIBS (EngineeringConsulting Services; Computer System Design Services) are

ch Policy

System Design Services (number of weighted observa-tions = 1514 establishments) and Management ConsultingServices (number of weighted observations = 484 estab-lishments). The dependent variable of the paper is based

1536 N. Amara et al. / Resear

considered in this study. Industries were measured with aseries of binary variables defined as follows: MANAGE isa binary variable coded 1 if the firm operates in Manage-ment Consulting Services, and 0 otherwise. ENGINEE is abinary variable coded 1 if the firm operates in EngineeringConsulting Services, and 0 otherwise; finally, COMPUT is abinary variable coded 1 if the firm operates in ComputerSystem Design Services, and 0 otherwise. This last categoryof firms was used as the reference category in the regressionmodel.

3.5. Control variables

3.5.1. LnSIZEAs of yet, there is no consensus on the relation between

firm size and protection methods. Arundel and Kabla foundthat large manufacturing firms are more likely to rely onpatents to protect their inventions and innovations thanSMEs. Traoré (2005) also found that larger biotech firmsrelied more on patents than their medium and small sizecounterparts to protect their innovations. Arundel (2001)has found that the relative importance of secrecy ver-sus patents decreases with firm size. Using the StatisticsCanada Innovation Survey of 1999, Hanel (2001) found thatsmall manufacturing firms rely less frequently than largefirms on protection methods, regardless of the method con-sidered. Moreover, the cost of applying for patents anddefending them in court would disproportionately dis-suade SMEs to rely on patents (Lerner, 1995; Cohen et al.,2000). We extend these hypotheses to KIBS. In this paper,firm’s size is measured by the total number of full-timeemployees in 2003. This variable was matched with thenormal distribution using a logarithmic transformation.Based on this rationale, we hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 10. Large KIBS are more likely to attempt toprotect their innovations by using legal mechanisms, espe-cially patents, rather than informal protection mechanisms.

3.5.2. ExportArundel (2000) found that patent protection is more

important to manufacturing firms exporting to the UnitedStates or Japan. In these markets, due diligence also appliesto the examination of the intellectual property rights uponwhich the innovations are based. We extend this hypothesisto KIBS to suggest that exporting KIBS are more likely thanothers to protect their innovations by using legal mecha-nisms, especially patents. In this paper, Export is a binaryvariable coded 1 if the firm generated revenues in 2003from the sale of products (goods and services) to clientsoutside Canada, and 0 if no revenues in 2003 came fromthe sale of products (goods and services) to clients outsideCanada. Thus, one may hypothesise that:

Hypothesis 11. KIBS are more likely to attempt to pro-tect their innovations by using legal mechanisms, especiallypatents, rather than informal protection mechanisms.

3.5.3. SubsidiaryFinally, as hypothesized by Arundel (2001), we might

expect that subsidiary firms could be induced to rely ontheir parent firms for the development of their innovations,

37 (2008) 1530–1547

and thus be inclined to rely more frequently on secrecy thanon patents. Despite the fact that he did not find firm statusto have a statistically significant effect on IP methods, wesuggest considering the impact of this factor on the choiceof protection methods. Therefore, we hypothesise that sub-sidiary firms are more likely to rely on informal than legalmethods, especially on secrecy rather than patents. In thispaper, SUBSIDIARY is a binary variable coded 1 if the firmdeclared that the operations of its business unit are part ofa larger firm, and 0 otherwise. Thus, one may hypothesisethat:

Hypothesis 12. Subsidiary KIBS are more likely to attemptto protect their innovations by using informal rather thanlegal protection mechanisms.

4. Methods

4.1. Data

The data used in this study are based on 2625weighted observations representing innovative serviceestablishments3 who responded to the 2003 StatisticsCanada Innovation Survey on services. This survey wascarried out by Statistics Canada following the guidelinesdeveloped in the OECD’S Oslo Manual (OECD, 1996). Thesurvey covered ICT service industries, selected naturalresource support services, selected transportation indus-tries and selected knowledge-based professional, scientificand technical services industries.

A key requirement of any Statistics Canada survey is aminimal respondent burden. As a result, firms with lessthan 15 employees and earning less than $250,000 inrevenues are considered small businesses and thereforeexcluded from surveys. Data representativeness and qual-ity are ensured by not only accounting for non-respondentsand applying multistage stratification techniques, but alsoby systematically applying, throughout the survey process,6 comprehensive dimensions of data quality (Traoré, 2004;Statistics Canada, 2003). Thus, the sample unit comprisesestablishments with at least 15 employees and at least$250,000 in revenues, and is representative of the survey’starget population.

The target respondents were the CEO or senior man-agers of the establishments. The survey was mailed outon September 15, 2003 and data collection closed on Jan-uary 30, 2004. The overall response rate was 70.5%, for atotal of 2123 completed questionnaires. Sample weights ofthe non-response population were accounted for by adjust-ing the sample weights of the respondent population. Thedata analyzed in this paper cover only innovative serviceestablishments operating in engineering services (numberof weighted observations = 627 establishments), Computer

3 The statistical unit of observation for the survey is the establishment.In the following sections, the establishment will be referred to by the term“firm”.

ch Policy

oemircais

4

ua(tomemcmtarosar

dhsCoamittFmmS

iafemtMidstSti

N. Amara et al. / Resear

n the question of IP protection methods which askedach respondent to indicate whether or not his establish-ent had used the following methods for protecting its

ntellectual property during the last three years: patents,egistration of design patterns, trademarks, copyrights,onfidentiality agreements, secrecy, complexity of designs,nd lead-time advantages on competitors. Methodologicalssues and the overall description of the survey are pre-ented in Lonmo (2005).

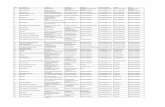

.2. Descriptive statistics

Overall, the IP protection methods most frequentlysed by establishments are respectively confidentialitygreements (77% of establishments), lead-time advantages60.1%), and secrecy (53.8%). At the other extreme, thehree least used IP protection methods are registrationf design patterns (11.8%), patents (15.7%), and trade-arks (34.5%) (Table 1). The results also suggest that

stablishments in Engineering Consulting Services relyore frequently on secrecy, lead-time advantages, and

onfidentiality agreements than on the other protectionethods. By comparison, establishments in Computer Sys-

em Design Services rely more frequently on confidentialitygreements, lead-time advantages, and secrecy than onegistration of design patterns, patents and complexityf designs. Finally, establishments in Management Con-ulting Services rely more frequently on confidentialitygreements, lead-time advantages, and copyrights than onegistration of design patterns, patents, and trademarks.

Table 1 also reports the Chi-square tests of indepen-ency comparing the proportion of establishments thatave used IP protection methods according to the type ofervice industry. Results indicate that establishments inomputer System Design Services rely more on registrationf design patterns, trademarks, copyrights, confidentialitygreements, and lead-time advantages than the establish-ents in the two other service industries. Establishments

n Engineering Consulting Services rely more on registra-ion of design patterns, secrecy, and complexity of designshan those operating in Management Consulting Services.inally, establishments in this latter service industry relyore on trademarks, copyrights, and confidentiality agree-ents than those operating in Engineering Consulting

ervices.Overall, establishments studied in the current paper,

rrespective of the industry, rely more on confidentialitygreements to protect their innovations than on any otherormal method. However, sectoral differences exist. In fact,stablishments in Computer System Design Services relyuch more on each and all formal protection methods than

heir counterparts in Engineering Consulting Services andanagement Consulting Services. As well, establishments

n Engineering Consulting Services rely much less on confi-entiality agreements than their counterparts in computer

ystem design and Management Consulting Services. Onhe other hand, establishments in Engineering Consultingervices rely more on secrecy and complexity of designshan the other establishments, whereas establishmentsn computer system design and Management Consulting37 (2008) 1530–1547 1537

Services rely more on lead-time advantages than establish-ments in Engineering Consulting Services.

These findings about the dependent variables, i.e., theprotection methods, have to be nuanced with regard toresults of prior studies in manufacturing industries (Levinet al., 1987; Cohen et al., 2000; Arundel, 2000; Hanel, 2001),as well as prior studies in service industries (Hanel, 2001)which showed that establishments rely more on informalrather than on formal methods in order to insure theirIP protection. In this study, we found that, overall, con-fidentiality agreements are used by a larger proportionof establishments and that copyrights are the third mostfrequently used protection method by establishments oper-ating in Management Consulting Services.

With regard to the explanatory variables (Table 2), in2003, the average establishment had 22.82% of its full-time employees involved in R&D activities; earned 25.8%of its total revenues from sales to clients outside of Canada;scored 3.60 out of a possible maximum of 5 on the index ofknowledge-development strategies; 1.60 and 3.21 out of apossible maximum of 5 on the External Knowledge-Sharingwith Research Organizations and with market organizationindices, respectively. Finally, the average firm scored 3.49out of a possible maximum of 5 on the index of internalknowledge-sharing.

Furthermore, Table 2 shows that 37.6% of the estab-lishments are part of a larger firm. Moreover, 17.5% of theestablishments have less than 20 employees, 45% of themhave between 20 and 49 employees, 20.5% between 50and 99 employees, and 17% of the establishments have 100employees or more. As for the innovation types, between2001 and 2003, 43.8% of the establishments surveyed intro-duced, onto the market, only new or significantly improvedproducts, 12.6% introduced, onto the market, only newor significantly improved processes, and 43.6% simulta-neously introduced, onto the market, new or significantlyimproved products and processes. Finally, slightly less thanone quarter of the establishments were in Engineering Con-sulting Services, 58% in Computer System Design Services,and 18% in Management Consulting Services.

4.3. Analytical plan

Previous empirical studies on complementaritiesbetween various variables have been based on threemain approaches, namely, the productivity approach,the reduced form exclusion restriction approach, andthe correlation approach. The first approach involvesmodelling a measurement of a firm’s objective functionwith parameters that specify the interactions betweenchoices. These parameters are interpreted as indicatorsof complementarity. In such a model, the distributionof interactions among choices is identified, and choicesmay be complementary for some firms, independent forsome others, and substitute for others (Athey and Stern,1998; Ichniowski et al., 1997; Mohnen and Röller, 2002;

Mancinelli and Massimiliano, 2007).In the second approach, the study of complementarityis carried out by focussing on the effects of two factors, andon their correlation (Arora, 1996; Athey and Stern, 1998).As mentioned by Galia and Legros (2004, p. 1192), the idea

1538 N. Amara et al. / Research Policy 37 (2008) 1530–1547

Table 1Distribution of the IP protection methods for the three selected services industries for the sub-population of innovative establishments

IP protection methods In % of innovative establishments that used the IP methods

All selectedindustries

Engineering ConsultingServices [a]

Management ConsultingServices [b]

Computer System DesignServices [c]

Legal methodsPatents 15.7 12.9=b−c 15.9=a=c 16.8+a=b

Registration of design patterns 11.8 10.7+b−c 5.6−a−c 14.3+a+b

Trademarks 34.5 18.6−b−c 27.2+a−c 43.4+a+b

Copyrights 41.0 28.6−b−c 37.6+a−c 47.1+a+b

Confidentiality agreements 77.0 49.4−b−c 73.3+a−c 89.5+a+b

Informal methodsSecrecy 53.8 53.2+b−c 31.1−a−c 61.4+a+b

Complexity of designs 37.6 39.8+b=c 33.0−a−c 38.1=a+b

Lead-time advantages 60.1 52.8=b−c 48.2=a−c 67.0+a+b

Note: The figures reported in columns 2, 3 and 4 are based on Statistics Canada estimates whereas column 1 and Chi-square tests were produced by theauthors. (a), (b) and (c) refer to the three selected services industries. The signs (+) and (−) indicate that, for each IP protection method considered in the

methoare testction m

rows, the proportion of establishments that have used this IP protectionconsidered in the columns than the other industries according to Chi-squindustries regarding the use or not by the establishment of this IP proterejected with significance levels of 10% or less.

is that “a factor which has an effect on one variable will notbe correlated with another variable unless the variables arecomplementary”. The major limitation of this approach isthat it cannot test for complementarity when more thantwo choice variables are simultaneously under study.

In the third approach, which is the one adopted inthis paper, variables under scrutiny are the dependent

elements of the empirical model (Laursen and Mahnke,2001; Galia and Legros, 2004; Schmidt, 2007). More specif-ically, this approach tests the correlation between two ormore dependent variables, conditional on a certain num-ber of explanatory variables. It carries out such a test byTable 2Descriptive statistics

Variables Type of variables

Continuous variablesR&D intensity [% of full-time employees involved inR&D activities in 2003]

Continuous num

Export [% of total revenues that came from sales toclients outside of Canada in 2003]

Continuous: num

Knowledge Development Strategies Index Weighted Index:External Knowledge Sharing with ResearchOrganizations

Weighted Index:

External Knowledge Sharing with MarketOrganizations

Weighted Index:

Internal knowledge sharing Weighted Index:

Categorical variables

Subsidiary firm • Percentagare part of l

Innovation types • Innovation• Innovatio• Innovation

Firm’s size [number of full-time employees in 2003] • Less than• 20–49 em• 50–99 em• 100 emplo

Services industries • Engineeri• Computer• Managem

Note: Based on Statistics Canada estimates (Survey of Innovation 2003).

d is statistically significantly (p < 0.1) greater or smaller for the industrys. The sign (=) indicates that no significant differences exist between theethod. The null hypothesis (independency between two variables) was

estimating a bivariate or Multivariate Probit model. Thecomplementarity arises if the null hypothesis of absenceof correlation between the residuals of two or more probitregression equations is rejected.

This last approach was chosen over the other twoapproaches for two main reasons. First, in contrast to thefirst approach, it does not require the specification of an

objective function. Instead, it uses the choice variables asdependents in the regression models and thus offers adirect test for complementarity between different IP pro-tection methods (Galia and Legros, 2004). Second, unlikethe second approach that cannot test for complementarityMean Standard deviation Cronbach’s ˛

ber 22.82 26.35 –

ber 25.87 34.99 –

5 items 3.60 0.73 0.714 items 1.60 0.82 0.81

4 items 3.21 0.82 0.55

3 items 3.49 0.86 0.67

e of firms that the operations of their business unitsarger firms

37.6%

in products only 43.8%n in processes only 12.6%

in products and processes 43.6%

20 employees 17.5%ployees 45.0%ployees 20.5%yees or more 17.0%

ng Services 23.9%System Design Services 57.7%

ent Consulting Services 18.4%

ch Policy

wccn8r

btsmabSibtPe

stiitFIdiso

mbimL

Y

w

Y

wae3i

to zero. The computed value of this index is much largerthan the critical value of the chi-squared statistic with 28degrees of freedom at the 1 percent level. This suggeststhat the null hypothesis, that all the correlation coeffi-

N. Amara et al. / Resear

hen more than two choice variables are under study, theorrelation approach offers a general solution to testingomplementarity among various IP protection methods, aso limit is set on the number of such variables. We studiedIP protection methods, and therefore could not use the

educed form exclusion restriction approach.To the extent of our knowledge, the Multivariate Pro-

it model approach to data analysis has never been usedo address the issue of how knowledge-intensive-basedervice establishments combine various IP protectionethods in preventing imitation from rivals. The multivari-

te probit specification allows for systematic correlationsetween choices for the different protection strategies.uch correlations may be due to complementarities (pos-tive correlation) or substitutions (negative correlation)etween strategies. In using the multivariate probit estima-ion method, the issue of inefficient estimates in separaterobit models is resolved, where significant correlationsxist among IP protection methods (Belderbos et al., 2004).

The Multivariate Probit model used in our study con-ists of eight binary choice equations. These choices are forhe IP protection strategies used by Canadian knowledge-ntensive service establishments operating in three servicendustries, namely: Engineering Services, Computer Sys-em Design Services and Management Consulting Services.ive IP protection strategies refer to formal or legalP protection methods and are: Patents, Registration ofesign patterns, Trademarks, Copyrights, and Confidential-

ty agreements. Three other IP protection methods refer totrategic or informal methods and are: Secrecy, Complexityf designs and Lead-time advantages over competitors.

The MVP model, an extension of the standard Probitodel, is used in estimating the following system of eight

inary dependent variables. It allows for jointly estimat-ng several equations while controlling for the existence of

utual correlations between their disturbances (Galia andegros, 2004; Belderbos et al., 2004).

The model is written as follows:

= ˇX + ˙

here:

=

⎛⎜⎜⎜⎜⎝

y1y2...y8

⎞⎟⎟⎟⎟⎠

; ˇ =

⎛⎜⎜⎜⎜⎝

b10 , b11 , b12 , . . . , b111b20 , b21 , b22 , . . . , b211. . .. . .. . .b80 , b81 , b82 , . . . , b811

⎞⎟⎟⎟⎟⎠

X =

⎛⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎜⎝

1x1x2...x11

⎞⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎟⎠

, and ˙ =

⎛⎜⎜⎜⎜⎝

ε1ε2...ε8

⎞⎟⎟⎟⎟⎠

ith Y being the vector of the eight binary dependent vari-bles and X the vector of the explanatory variables for theight equations. These are as previously defined (Section.2) and are the same for all eight dependent variables. ˇ

s the matrix of the coefficients to be estimated and ˙ rep-

37 (2008) 1530–1547 1539

resents the vector of the error terms of the eight estimatedequations. The MVP model also provides the estimates ofthe variance–covariance matrix of the equations’ distur-bances (Greene, 1995) that will serve to conclude to theexistence of substitution or complementary effects in thechoice of the different IP protection methods.

Table A1 provides results of the Principal Compo-nents Factor Analysis and internal reliability coefficients(Cronbach’s Alphas) for the explanatory variables with amultiple-item scale. These results indicate that, for each ofthese variables, the items loaded on a single factor whichassesses their unidimensionality. Moreover, the values ofCronbach’s ˛ indicate that the items forming each index arereliable. Finally, the correlation matrix between the contin-uous predictors used in the regression models (Table A2)indicates that the highest correlation coefficient betweenthe independent variables is 0.285 and corresponds to thatbetween the Internal Knowledge-Sharing Index and theExternal Knowledge Sharing with Market OrganizationsIndex. The second column of Table A2 also reports toler-ance statistic values for these predictors. Tolerance statisticvalues, which are the reciprocal of Variance Inflation Fac-tors (VIF), indicated whether a predictor has a strong linearrelationship with the other predictors. It can be seen that allthe tolerance statistic values are much higher than 0.2. Thisensures that there is no multicollinearity concern (Menard,1995; Field, 2006).

5. Regression results

The empirical results obtained from the MultivariateProbit model estimation are summarized in Table 3. Thegoodness of fit is first assessed using McFadden R2 (OudeLansink et al., 2003; Veall and Zimmermann, 1996).4 Avalue of 0.129 is found and remains reasonable for qual-itative dependent variable models.5 A second assessmentof the quality of the model fit is given by the first reportedLikelihood Ratio Index (LR index1) which compares the LogLikelihoods’ values related to the unrestricted model and tothe “naïve” model containing only an intercept for each ofthe eight equations. The computed value of this first index ismuch larger than the critical value of the chi-squared statis-tic with 96 degrees of freedom at the 1 percent level. Thissuggests that the null hypothesis, that all the parametercoefficients (except the intercepts) are all zeros, is stronglyrejected. Consequently, our model is significant at the 1percent level. The second reported Likelihood Ratio Index(LR index2) compares the Log Likelihoods’ values related tothe unrestricted model and to the model forcing the cor-relations between the equations’ disturbances to be equal

4 McFadden R2 is calculated as: 1 − [log L(�)/log L0] where log L0 is thevalue of log-likelihood function subject to the constraint that all coeffi-cients except the constant are zero, and log L(�) is the maximum value ofthe log-likelihood function without constraints.

5 According to Sonaka et al., McFadden R2 in the range of 0.2–0.4 aretypical for logit models.

1540N

.Am

araet

al./ResearchPolicy

37(2008)

1530–1547

Table 3Multivariate Probit regressions’ results

Independent variables Patents Registration of designpatterns

Trademarks Copyrights Confidentialityagreements

Secrecy Complexity of designs Lead-time advantages

Coefficient(ˇ)

P-value Coefficient(ˇ)

P-value Coefficient(ˇ)

P-value Coefficient(ˇ)

P-value Coefficient(ˇ)

P-value Coefficient(ˇ)

P-value Coefficient(ˇ)

P-value Coefficient(ˇ)

P-value

Intercept −2.545** 0.063 −2.855** 0.052 −1.957** 0.087 0.823** 0.079 −0.559** 0.060 1.068** 0.077 0.569** 0.055 0.649** 0.053

R&D investmentSrRDa 0.051** 0.038 −0.024 0.790 0.079** 0.075 0.070 0.203 0.064 0.226 0.107** 0.026 0.049** 0.085 0.063** 0.076

Knowledge variablesInternal knowledge

sharing0.120 0.583 0.102 0.744 0.167 0.358 0.244** 0.063 0.109** 0.081 0.061 0.965 0.225** 0.099 0.198* 0.159

External KnowledgeSharing with ResearchOrganizations

0.023 0.993 0.076 0.769 0.202* 0.139 0.356*** 0.009 0.013 0.947 0.247* 0.157 −0.070 0.685 0.082 0.591

External KnowledgeSharing with Market

0.105 0.570 −0.107 0.648 −0.167 0.357 −0.327** 0.059 −0.023 0.884 −0.078 0.606 −0.071 0.649 −0.331** 0.031

Knowledge developmentStrategies

−0.168 0.613 0.050 0.909 −0.157 0.484 −0.560*** 0.006 −0.203 0.232 −0.355** 0.090 −0.246* 0.114 −0.370** 0.053

Services (type services)Development of Productc −0.180 0.583 −0.494* 0.111 0.110 0.693 −0.684*** 0.009 −.072 0.823 −0.079 0.762 −0.381** 0.041 −0.029 0.914Development of Processc −0.702** 0.079 −0.673** 0.098 −0.906** 0.041 −0.814** 0.063 −0.369 0.362 −0.107 0.761 −0.759* 0.139 −0.069 0.854

Industry sectorsEngineering Servicesd −0.356** 0.056 −0.070** 0.076 −0.527** 0.057 −0.273*** 0.003 −0.119** 0.093 −0.276** 0.032 0.259 0.301 0.203 0.428Management Consulting

Servicesd−0.713** 0.067 −0.144** 0.034 −0.177** 0.061 0.315 0.859 −0.064*** 0.006 −0.228** 0.046 −0.555** 0.040 −0.341* 0.137

Control variablesSize LnSIZEb 0.306** 0.091 0.427* 0.112 0.315** 0.082 0.204 0.208 0.173 0.415 −0.042 0.765 −0.023 0.875 0.143 0.290Export 0.535 0.239 0.114 0.800 0.369 0.257 0.070 0.803 0.584** 0.031 0.644*** 0.010 0.070 0.797 0.584 0.015***

Subsidiary Firm 0.132 0.097** 0.182 0.319 0.216 0.427 0.208 0.417 0.251 0.409 0.169 0.517 −0.186 0.464 −0.059 0.985

Correlations between disturbances ε1 ε2 ε3 ε4 ε5 ε6 ε7

ε2 0.714*** 0.000ε3 0.508*** 0.004 0.556*** 0.010ε4 0.393** 0.049 0.442** 0.033 0.689*** 0.000ε5 0.358 0.370 −0.094 0.757 0.371** 0.066 0.391**0.057ε6 0.535*** 0.002 0.356* 0.139 0.118 0.492 0.249 0.235 0.345** 0.042ε7 −0.105** 0.032 −0.156** 0.078 −0.011 0.950 0.095 0.499 0.367** 0.036 0.077 0.612ε8 0.521*** 0.007 0.272 0.222 0.253 0.294 0.160 0.348 0.357** 0.021 0.596*** 0.0000.1050.499

Weighted number of observations 2625Log Likelihood −1125.560McFadden 0.129LR index1 �2 (96) −1293.59*** Compares the unrestricted model to the “naïve” model containing only the intercept for each of the eight equationsLR index2 �2 (28) −1251.30*** Compares the unrestricted model to the model forcing the correlations between the equations’ disturbances to be equal to zeroLR index3 �2 (84) −1242.62*** Compares the unrestricted model to the model forcing the regression coefficients for each of the 12 independent variables to be equal across the 8 equations

*, ** and *** indicate that the coefficient is significant, respectively, at the 10%, 5% and 1% thresholds.a Sr indicates a square root transformation.b Ln indicates a logarithmic transformation.c Reference category is Development of Product and Process.d Reference category is Computer System Design Services.

ch Policy

ciaifbttbrrtdcvdcce

ttapMbmTtApesi

dcpatdmfilt

taoptdceftd

i

N. Amara et al. / Resear

ients between the equations’ disturbances are all zeros,s strongly rejected. Consequently, the use of the Multivari-te Probit model to estimate our system of eight equationss appropriate. This last result provides evidence, at leastor our data, that the use of the separate standard Pro-it models is not adapted to estimate the determinant ofhe choice of the establishments’ protection tools. Indeed,he resulting estimators from the standard approach woulde inefficient. The last Likelihood Ratio Index (LR index3)eported in Table 3 compares the Log Likelihoods’ values,elated to the unrestricted model and to the model forcinghe regression coefficients for each of the twelve indepen-ent variables, to be equal across the eight equations. Theomputed value of this index is much larger than the criticalalue of the chi-squared statistic with 84 degrees of free-om at the 1 percent level. This suggests that the estimatedoefficients differ substantially across the equations, indi-ating the appropriateness of considering separately theight protection methods.6

Table 3 also reports the correlation coefficients ofhe error terms of the eight equations. We can seehat most of these correlation coefficients are significantnd positive, which supports the hypothesis of interde-endence between the different IP protection methods.ore specifically, the results suggest complementarities

etween patents, registration of design patterns, trade-arks, secrecy and lead-time advantages over competitors.

hese findings are consistent with those in the manufac-uring sector and for science-based firms (Arora, 1997;rundel, 2001; Cohen et al., 2000; Hussinger, 2005). Theyrovide further empirical support to the fact that somestablishments combine both formal legal and informaltrategic protection methods in order to “keep potentialmitators at bay” (Arora, 1997).

The results also suggest that the registration ofesign patterns is complementary to patents, trademarks,opyrights, and secrecy. Likewise, trademarks are com-lementary to patents, copyrights, and confidentialitygreements. Confidentiality agreements are complemen-ary to trademarks, copyrights, secrecy, complexity ofesigns, and lead-time advantages. Secrecy is comple-entary to patents, registration of design patterns, con-

dentiality agreements, and lead-time advantages. Finally,ead-time advantages over competitors are complementaryo patents, confidentiality agreements, and secrecy.

However, the results also suggest that there is substi-ution between patents and complexity of designs, as wells between registration of design patterns and complexityf designs. Furthermore, patents and registration of designatterns are independent from confidentiality agreements;rademarks are independent from secrecy, complexity ofesigns, and lead-time advantages, as indicated by theorresponding non-significant correlations between the

stimated disturbances. Copyrights are used independentlyrom secrecy, complexity of designs and lead-time advan-ages. Finally, secrecy is independent from complexity ofesign, and complexity of design is used independently6 Hence, for example, a same variable might exert a significant positivempact on some protection methods but not on all of them.

37 (2008) 1530–1547 1541

from lead-time advantages to protect KIBS from imitationby rival firms.

As for the extent to which dependent variables explainthe likelihood that the various IP protection methods areused by the establishments, results show that anywherefrom three to eight variables are significant at levels vary-ing from 1% to 10% in each of the eight equations. Moreprecisely, R&D intensity (SrR&D) is positive and significantin five equations, namely, patents, trademarks, complex-ity of designs, and lead-time advantages, with the highestcoefficient in the case of secrecy. These results are not inline with our expectations to the effect that R&D intensityis associated more with formal IP protection methods thanwith informal ones.

External Knowledge-Sharing with Research Organiza-tions is found to have a positive and significant effect on thelikelihood of choosing trademarks, copyrights, and secrecy,with the highest coefficient in the case of copyrights.Likewise, External Knowledge-Sharing With Market Orga-nizations is found to have a negative and significant effectonly for two IP protection methods, namely, copyrightsand lead-time advantages, with the highest coefficient forcopyrights. As mentioned previously, these two variablescapture the openness of the establishments or their willing-ness to look for external information to incorporate into thedevelopment or improvement of their products and pro-cesses. Second, internal knowledge-sharing is significantlyand positively related to copyrights, confidentiality agree-ments, lead-time advantages, and complexity of designequations, with the highest coefficient in this latter case.Third, knowledge-development strategies have a signifi-cant and negative influence on the likelihood of relying oncopyrights, secrecy, complexity of designs, and lead-timeadvantages, but have no significant impact on the likelihoodof relying on the other legal protection methods.

Concerning the types of innovation, establishments thatsimultaneously introduced new or significantly improvedproducts and processes onto the market, between 2001and 2003, are more likely to rely on registration of designpatterns, copyrights, and complexity of designs than estab-lishments that introduced, during the same period, onlynew or significantly improved products, or only new or sig-nificantly improved processes. Moreover, establishmentsthat introduced, between 2001 and 2003, onto the mar-ket, only new or significantly improved processes are lesslikely to rely on patents and trademarks than those thatsimultaneously introduced, during the same period, ontothe market, new or significantly improved products andprocesses.

With regard to industry effects, the results show thatestablishments operating in Computer System Design Ser-vices are more likely to rely on patents, registration ofdesign patterns, trademarks, confidentiality agreements,and secrecy than those in engineering services and Man-agement Consulting Services. Moreover, establishmentsoperating in Management Consulting Services are less

likely to rely on all the informal protection methods thantheir counterparts in Computer System Design Services.Finally, establishments in engineering services are lesslikely to rely on copyrights than those in Computer SystemDesign Services.1542 N. Amara et al. / Research Policy 37 (2008) 1530–1547

Table 4Summary table of the Multivariate Probit regressions’ results explaining the choice of the protection strategies

Independent variables Patents Registration ofdesign patterns

Trademarks Copyrights Confidentialityagreements

Secrecy Complexityof designs

Lead-timeadvantages

R&D investment• SrRD + NS + NS NS + + +

Knowledge variables• Internal knowledge sharing NS NS NS + + NS + +• External Knowledge Sharingwith Research Organizations

NS NS + + NS + NS NS

• External Knowledge Sharingwith Market

NS NS NS − NS NS NS NS

• Knowledge developmentStrategies

NS NS NS − NS − − −

Services (type services)• Development of Product NS − NS − NS NS − −• Development of Process − − − − NS NS − −

Industry sectors• Engineering Services − − − − − − NS NS• Management ConsultingServices

− − − NS − − − −

Control variables• Size LnSIZE + + + NS NS NS NS NS• Export NS NS NS NS + + NS NS• Subsidiary firm NS NS NS NS NS NS NS NS

Correlations betweendisturbances

ε1 ε2 ε3 ε4 ε5 ε6 ε7

ε2 +ε3 + +ε4 + + +ε5 NS NS + +ε6 + + NS NS +

s non-si

ε7 − − NSε8 + NS NS

(+) Indicates positive impact; (−) indicates negative impact; (NS) indicate

Firm size (LnSIZE) is positive and significant in all theequations for legal protection methods except copyrights,with the highest coefficient for registration of design pat-terns. However, firm size is not significant in the fourequations for informal protection methods. This result isconsistent with several prior studies stressing that firm sizeis an important determinant of the use of legal protectionmethods, especially for patents (Hall and Ham Ziedonis,2001; Hanel, 2001; Nesta and Saviotti, 2005). Finally, gen-erating revenues from export has a positive impact on thelikelihood to resort to three of the four informal meth-ods considered in this study: confidentiality agreements,secrecy, and lead-time advantages.

Table 4 summarizes the previous findings and thoseregarding the determinants of use of the different IP pro-tection methods.

6. Discussion and conclusion

The protection of the innovations commercialized byKIBS from imitation by rivals can rely on a large varietyof mechanisms, some formal or legal, while others arestrategic or informal. In comparison to prior studies that

have focussed on patents, this study considered severallegal and informal protection mechanisms, and investi-gated the question of how KIBS combine eight protectionmechanisms. Results show that 15.7% of KIBS relied onpatents, 11.8% on registration of design patterns, 34.5% onNS + NSNS + + NS

gnificant impact.

trademarks, 41.0% on copyrights, 77.0% on confidential-ity agreements, 53.8% on secrecy, 37.6% on complexity ofdesigns, and 60.1% on lead-time advantages over competi-tors. Overall, these descriptive findings are consistent withthe results of studies on the frequency and extent of use oflegal as well as informal protection methods in the manu-facturing industries.

Contrary to prior studies that have examined the useof protection mechanisms as separate mechanisms, thispaper estimated a Multivariate Probit model to take intoaccount the fact that KIBS simultaneously make use of var-ious alternative IP protection methods when protectingtheir innovations. Positive significant correlations betweenequations suggest that various IP protection methods areused by establishments as sets of complementary pro-tection methods. More specifically, the results show thatpatents, registration of design patterns and trademarksare three complementary legal methods on which KIBSrely. Furthermore, secrecy and lead-time advantages overcompetitors are two informal protection methods thatexhibit complementarities. Additionally, patents, registra-tion of design patterns, trademarks, secrecy and lead-timeadvantages over competitors constitute legal and informal

methods that are used jointly. These complementaritiessuggest that IP protection mechanisms that are interde-pendent and reinforce each other to protect innovationsfrom imitation by rival establishments constitute a pat-tern on which firms rely to protect their innovations fromch Policy

ibHowctlrwmfr

pwsfiodtpvmfmismKsf

saeifmciasaitlmsidopmc

ttops

N. Amara et al. / Resear

mitation. These results shed light on a much larger num-er of patterns of complementarities than predicted by theypotheses 1–4 derived from the conceptual frameworkf the paper. Contrary to expectations, there are patternshere only legal mechanisms are complementary, other

ases in which only informal mechanisms are complemen-ary, and finally, still other patterns where a combination ofegal and informal mechanisms are complementary. Theseesults suggest that patterns of complementarities uponhich KIBS firms rely are much more diversified and muchore complex than predicted by the existing conceptual

ramework. In itself, this result suggests that more elabo-ated conceptual frameworks will need to be developed.

A second way of approaching Hypotheses 1–4 on com-lementarities is to take into account a second patternhich is based on protection mechanisms that are used as

ubstitutes to protect innovations from imitation by otherrms. More specifically, this substitution pattern is basedn the fact that KIBS rely on patents and complexity ofesigns as substitutes, and use registration of design pat-erns and complexity of designs as substitutes in order torotect their innovations from imitation. Thus, there is aery limited number of substitution patterns. One infor-al mechanism and two formal mechanisms are substitute

or each other. In itself, this result suggests that protectionechanisms play different roles in the protection of service

nnovations from imitation, otherwise, a larger number ofubstitution patterns may have been found. These resultsight also suggest that the tacit and intangible nature of the

IBS induce them to rely on a combination rather than on aubstitution of protection mechanisms to prevent imitationrom rival firms.

Hypotheses 1–4 were also approached under the per-pective of a third category of patterns which is made up ofll the protection mechanisms that are independent fromach other and do not exhibit any synergy. This last patterns composed of various pairs of protection mechanisms. Inact, results show that patents and confidentiality agree-

ents are independent; registration of design patterns,onfidentiality agreements and lead-time advantages arendependent; trademarks, secrecy, complexity of designs,nd lead-time advantages are independent; copyrights,ecrecy, complexity of designs and lead-time advantagesre independent; secrecy and complexity of designs arendependent; and finally, complexity of designs and lead-ime advantages are independent. Thus, there is a ratherarge number of patterns in which different protection

echanisms are independent from each other. This resultuggests that different elements of service innovations arendependent from each other and need to be protected byifferent mechanisms that are also independent from eachther. Once more, these results suggest that managing therotection of inventions and innovations in KIBS firms isuch more complex than predicted by the current con-

eptual frameworks.The results of the Multivariate Probit model also suggest

hat these various patterns of complementarities, substi-ution and independence cannot be adequately explainednly with the degree of knowledge codification and out-ut tangibility. The results of the econometric modelshow important differences in the determinants of the

37 (2008) 1530–1547 1543

different methods of IP protection and their associated pat-terns. For example, the reliance on protection mechanismsthat are part of the complementary pattern tends to beexplained by a small number of common factors, namely,R&D investments, development of process innovation, sizeof establishments and the fact that establishments operatein Computer System Design Services. The reliance on theprotection mechanisms that make up the substitution pat-tern is explained by an even smaller number of commonfactors: R&D and process innovation for the substitutionbetween patents and complexity of designs, and productand process innovation in combination with the fact thatestablishments operate in Computer System Design Ser-vices for the substitution between registration of designpatterns and complexity of designs. Finally, the reliance onthe mechanisms included in the group of independent IPprotection mechanisms is explained by very heterogeneousfactors. In themselves, these results suggest that protectingservice innovations from imitation by rivals involves com-plex theoretical and empirical issues that call for additionalresearch.

Let us now review and discuss more precisely the extentto which the other hypotheses derived from the modifiedHowells et al. conceptual frameworks are supported bythe results of the statistical analyses. Hypotheses derivedfrom the conceptual framework predicted that increasingR&D intensity contributes to increase the reliance of KIBSfirms on patents (Hypothesis 5) and on the registration ofdesign patterns (Hypothesis 6). The results of this studyshow that as KIBS become more R&D intensive, they tendto rely not only on patents, but on the complementari-ties of a large variety of legal and informal mechanisms:patents, trademarks, complexity of designs, secrecy, andlead-time advantages over competitors. Therefore, R&Dintensity does not induce KIBS to rely on legal rather thaninformal protection mechanisms, but instead to rely on thecomplementarities derived from the use of a large varietyof legal and informal mechanisms. This unexpected findingmay be explained by the fact that R&D activities conductedby KIBS firms might generate outputs that are less codifiedand less tangible than predicted in the conceptual frame-work.

We hypothesized a positive relation between KIBSknowledge management strategies and patenting(Hypothesis 7). The results of the statistical analysesdid not support this hypothesis. Instead, they suggestthat different types of knowledge management strategiesare related to the use of different types of protectionmechanisms. Hence, External Knowledge-Sharing withResearch Organizations is related to the use of trademarks,copyrights and secrecy, while External Knowledge-SharingWith Market Organizations is related to the use of copy-rights and lead-time advantages over competitors. Thethird knowledge management strategy tested in thisstudy, KIBS internal knowledge-sharing, is related to theuse of copyrights, confidentiality agreements, lead-time

advantages and complexity of designs. Finally, KIBSknowledge-development strategies are negatively relatedto the use of copyrights, secrecy, complexity of designsand lead-time advantages. Once more, these unexpectedresults suggest that explaining the mechanisms uponch Policy

1544 N. Amara et al. / Researwhich KIBS firms rely to protect their inventions andinnovations is much more complex than predicted in thecurrent conceptual frameworks. The tacit and intangiblenature of knowledge and knowledge outputs might makethem more difficult to explain than predicted.