Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

Transcript of Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

81

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

Zuzana Husárová

Abstract: The paper focuses on the mobile applications created for tablets that could be assigned significant literary values. It studies a variety of literary applications and proposes their categorization: interactive stories applications oriented at children (remediated or digital born), applications supporting creative writing, applications remediating print literary works, applications on multiple digital platforms, interactive narrative applications, interactive poetic ap-plications. For each of the categories, several examples are intro-duced and analyzed. The main focus is on those applications that use the touch gesture in an innovative and semantically meaning-ful way and thus support users’ interactivity, creativity and playful potential.

1 Introduction You will rememberwe did these things

in our youth,many and beautiful things. […]

Sappho, Time of Youth.

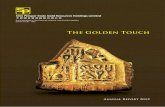

A young woman (maybe the great lyric poetess Sappho of Lesbos, may-be someone else) is on the Pompeiian fresco (Figure 1), dating from 1st

century AD, depicted with a stylus and four wax tablets. Wax tablet is, simply said, “a piece of wood with a wax-filled recess; using a metal-tipped implement, one writes on the tablet by scratching the surface of the wax, which is darkened for greater contrast. In effect, it is a renewa-ble scratch pad.“1 Wax tablets (in Latin tabulae) were from the ancient times until the Middle Ages used mostly as a writing tool for notes, drafts, correspondence, teaching, for recording speeches and various other types of information, like business accounts, for calculating. Besi-des all other purposes, they were used also for writing literature. Con-temporary era has seen the rise of tablets, but not of those made of wax

1 Priest-Dorman and Priest-Dorman 1999.

82

Z. Husárová

any more, but rather of the technological gadgets – mobile computers with touch screen, usually controlled by finger gestures. What links are responsible for naming these different things with the same term? Be-sides having a similar rectangular shape, also manually manipulating with the tablet area (either by scratching with stylus anywhere on wax tablets or by pressing a finger on an active spot on mobile tablets) has an effect on the “display”. These new tablets, running on mobile opera-ting systems (mainly iOS or Android2) offer their users also the writing and reading functions, as their wax predecessors did. Moreover, these new digital media devices are enriched with the multimedia dimen-sion, Internet connectivity that offers possibilities for generating con-tent as well as multiple opportunities for both work and leisure. This

2 other mobile platforms are Blackberry OS, Windows Phone.

Figure 1. Depiction of a girl with a stylus and wax tablets on a Pompeiian fresco (often called Sappho)

83

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

paper will look at various approaches towards the implementation of literary expression into the mobile tablets.

A Polish theoretician of electronic literature, Mariusz Pisarski, de-fines the literature on mobile devices in his entry in Słownik Gatunków Literatury Cyfrowej as:

“a literary work designed for systems, interfaces and reading habits typical for smartphones, mobile devices, which, by their technolog-ical advancement and type of use – situate themselves between sys-tems, interfaces and reading habits typical for PCs and laptops and those known from traditional mobile phones. The distinguishing traits for this genre are the particular material placement of the text, specific composition, adapted to the limitations of the device (divid-ing the text into chunks, discontinuous reading, a small screen) and an above-platform manner of distribution.”3

The mobile platform offers new characteristics for the literary expres-sion – multimedia dimension, interactivity, kinetic textuality and inter-active design, new forms of manipulation with the text (responsiveness to touch, movement of the whole device, even voice responsiveness). However one has to be aware that very long texts are difficult to read on mobile devices, and therefore the author should consider the char-acteristics of the mobile devices prior to writing the text – to be able to structure the story/poem based on the platform features, taking into account its strengths and weaknesses. Besides the poets/designers/pro-grammers in one person (who should be aware of all the before-men-tioned technical characteristics), common are also collaborations bet-ween writers and interactive designers or programmers, or in some cases even the whole production team, where the use of the technical parameters can be the task of the designers.

Due to the emergence of tablets, new market has grown – the market of applications. Mobile products for Apple devices can be download-ed from App Store, products running on the Android platform, can be found on Google Play. According to Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism report from 26th October 20114, 17 per cent of

3 Pisarski 2013.4 Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism report The Tablet

Revolution and the Future of News 2011.

84

Z. Husárová

tablet users read books on their tablets daily5. The report does not state what types of books the users read, whether regular e-books or some interactive applications. However, the percentage shows that people do read literature on their mobile devices, which can be fruitful for authors of electronic literature – those authors that go beyond mere transpos-ing of print content into the media realm (characteristic for e-books), but rather focus on the innovative possibilities that oral and written textuality and even intermedial projects can bring into the digital, mo-bile environment. Scott Rettberg (2011) even writes in connection with iPad literature about a “transitional moment” for the field of electronic literature:

“The interactive book, the literary artifact that is also a computa-tional artifact, is no longer a concept completely divergent from the path of mainstream publishing. E-Books are a fast growing sector of the publishing market. And from the launch the iPad, a number of writers, artists, publishers, and media makers have conceived of the tablet computer as an opportunity for reading experiences that don’t simply mimic the operation of the print book.“6

This paper will introduce and study only mobile applications, neither eBooks (on e-pub or other formats), interactive pdfs, nor audiobooks. It will also deal only with those applications that can be attributed as lit-erary: both narrative and poetic. Only those applications will be looked into, that can be downloaded from two biggest application markets: App Store and Google Play. Different categories of poetic applications will be introduced and analyzed, according to their innovative ap-proach to textual material, textual expression and poetics, according to their intermediality, aesthetics and use of touch gesture. The key focus will be on those applications that approach the user as having a creative potential and allow her in her activity to do “these things […] many and beautiful things.”7

5 According to this report, the percentage shows the percent of tablet users who do these activities on tablet daily: Email 54%, Get News 53%, Use Social Networks 39%, Play Games 30%, Read Books 17%, Watch Video 13%.

6 Rettberg 2011.7 Sappho in Barnstone 2009, p. 26.

85

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

The aim of this paper is to look into various ways how the literary content was remediated from the original print page into the multime-dia mobile format, as well as study the characteristics of the “digital born“8 literature (Hayles 2007) running on the interactive mobile plat-forms. The initial research was partially based on the research collec-tion iPhone and iPad E-Lit in ELMCIP Knowledge Base9, collected by Lori Emerson and Scott Rettberg.

The main questions are: What new functionalities do the interactive stories or poems provide for the reader? How do these functionalities enrich the poetic or narrative content? Do the aesthetic, poetic content and reader´s gestures when performing the work mutually influence each other? What is the purpose and potential use of these apps?

In the study dealing with the literary works on mobile platforms from the perspective of electronic literature, the following innovative meth-odological cornerstones and approaches could be applied: different modes of digital text performance (the topic of the ELMCIP Seminar on Digital Textuality with/in Performance10), platform studies (Ian Bogost and Nick Montfort11), critical code studies (Mark C. Marino12), software studies (Lev Manovich13), digital poetics and aesthetics, interface poet-ics and aesthetics, and many others. However, the aim of this paper is not to deeply analyze particular chosen works from any of those tempt-ing approaches, neither from the perspectives of narrative and poetic structures, but rather to highlight a diversity of mobile literary apps through a “media-specific analysis”. N. Katherine Hayles defines the “media-specific analysis” as: “a mode of critical attention which recog-nizes that all texts are instantiated and that the nature of the medium in which they are instantiated matters.”14 In this case, the referred me-dium is the mobile application. Also Hayles´s concept of “technotext”

8 Hayles 2007. By “digital born“ literature, Hayles means: “a first-generation digital object created on a computer and (usually) meant to be read on a computer.“

9 Emerson/Rettberg 2012.10 ELMCIP Seminar on Digital Textuality with/in Performance 2012.11 Bogost and Montfort, online.12 Marino 2006.13 Manovich, online.14 Hayles 2004, p. 67.

86

Z. Husárová

will be referenced in the paper. Hayles states that “the physical form of the literary artefact always affects what the words and other semiotic components mean.”15 She considers physical and semiotic layers of the work as cooperative elements. By the term “technotext”, she refers to those literary works, where the material and semantic layers appear in a substantial dialogue: “When a literary work interrogates the inscrip-tion technology that produces it, it mobilizes reflexive loops between its imaginative world and the material apparatus embodying that crea-tion as a physical presence.”16

Through a proposal of different categories of literary applications as well as through the use of “media-specific analysis” that should stress the characteristics of literary mobile platforms and define the specifics of each category, the paper aims to show that the literary applications create a fast-growing and quite an engaging field (as well as a cultural business market). Moreover, the paper wants to point out that in this field arose many works with high quality content, attractive interactive design and sophisticated semantics that are worthy of notice by literary communities. For each of those categories, a number of examples are provided. A rapidly growing number of applications made the selec-tion process quite demanding. The choice is based on subjective prefer-ences and limited by the number of pages of this paper.

The following main categories of the mobile interactive literary appli-cations are proposed:

• interactive stories applications oriented at children (remediated or digital born)

• applications supporting creative writing• applications remediating print literary works • applications on multiple digital platforms• interactive narrative applications • interactive poetic applications

15 Hayles 2003, p. 25.16 Ibid.

87

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

2 Interactive stories applications oriented at children (remediated or digital born)

Stories are designed to promote a reading experience that is both fun and educational for children.

PlayTales17

Interactive literary applications for children and young readers are the result of rise of quite a big and attractive application market for chil-dren and young readers. There are whole libraries of these interactive tales for iPads and iPhones, like Interactive Touch Books by Interactive Touch, Story Time for Kids by Teknowledge Software, Grimm’s Fairy Tales – 3D Classic Literature plus other tales by StoryToys Entertainment Limited and many others. The Android based collections of interac-tive stories applications include among many others Doll Play Books by Swan Media, Russian fairy tales called Fairy tales and storybooks by Whisper Arts, StoryBooks by Joe Raj. There are also collections running on both platforms like iStoryBooks by iMarvel, Read Unlimitedly! Kids’n Books by SMART EDUCATION, LTD, PlayTales by Genera Mobile and many others. These applications are mostly of a multimedia character, several of them aimed already at children from 2 years up. These stories very often incorporate spoken and/or written text, colourful animations or images and music, some of them can render pages in 3D, some offer multi-language editions. For example PlayTales offer eight languages: English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Chinese (Man-darin), and Japanese.

Children are supposed to navigate through the story by clicking on the assigned buttons or by virtually “thumbing” through the con-tent. Childrens´ little fingers can touch various (predominantly visual) pop-up media elements. Children are supposed to interact, in order to “trigger“ the story to appear. But in comparison to other kinds of digital fiction, like hypertext literature or computer games, the aim is not to find one´s own way through the story. These stories are tradi-tionally mono-sequential, there is only one prepared way how to en-gage with them. The form of these interactive tales for children is often

17 PlayTales, Apps. See: http://www.playtales.com/en/apps

88

Z. Husárová

reminiscent of the pop-up books format, transposed into digital me-dium (when concentrating on the aspects of interactivity by touching and thumbing). From another perspective, they could be considered as transpositions of the animated fairy-tales (when focusing on the com-bination of multimedia elements and oral narration).

Figure 2. Screenshot from Goblin Forest app by Emilio Villalba and PlayTales

89

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

Figure 3. Screenshot from Pinocchio app by PlayTales

The young reader can meet with two basic types, according to the con-text and content of the story: the well-known fairy-tales and stories repurposed for the touch mobile devices or the newly created fairy-tales and stories. There are still text-based stories, however, much more attractive for younger readers are those that do not privilege written text over visuals. Many of the stories are orally narrated and the styl-ized and sophisticated visuals also bear the semantic function. There-fore, these multimedia remediations18 of traditional fairy-tales work with shorter textual fragments and the semantics of the story is embed-ded in the media elements and their combinations.

18 the term “remediation” defines, according to the theory by J.D. Bolter and R. Grusin expressed in their book Remediation: Understanding New Media, a process of refashioning earlier media into new media and vice versa. In Bolter and Grusin 2000.

90

Z. Husárová

One of the most famous apps is Alice for the iPad (a remediation of Lewis Carroll´s Alice in Wonderland) with both the abridged and full versions of the classic story. The app is available besides English, also in German, French and Korean. The company that created this app – Atomic Antelope – also issued its successor entitled Alice in New York in 2011. This app was praised as one of the first with really attractive interactive e-book design. Apart from tapping the visuals, the reader can also make some elements of the classic-style illustrations “alive“ by moving the iPad. When the child tilts the iPad, the clock swings, bottle and jar fall, Alice shrinks and grows. When the reader shakes the iPad, mushrooms, pills and cards fall, Mad Hatter’s head bobbles. The design reminds us of the illustrated books design, rather than the design of pop-up books or animations – illustrations accompany the text in the centre of the page-like looking screen.

With most apps, children can choose whether they want to hear the recorded oral narration or they want to read it themselves. The London based app and retailer company Me Books allows the readers to tap on particular artwork and hear characters speak, plus it allows the readers to customise their apps by recording their own voice when reading the stories. By proposing to children to use their creativity, the apps can contribute to the informal education, where children learn to work with their voice without even realizing it.

In the paper Electronic books: children’s reading and comprehension, where Shirley Grimsaw et al describe their research on childrens’ reading and comprehension of a story in print version and in electron-ic version, they write that “the main benefits to children’s reading of electronic storybooks, compared to printed ones, were the provision of narration, accompanied by animated pictures and sound effects that related directly to the storyline.“19 Even though this team did not study the electronic books on mobile devices, but on the computer, it could be deduced that the benefits of the multimedia features make the interac-tive stories apps successful for the young readers. And the multimedia build-up is exactly what the attractive and successful stories apps for children have. The positives of these apps lie in bringing the stories

19 Grishaw et. al. 2007, p. 598.

91

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

into the attractive media environment and thus in childrens´ motiva-tion towards reading and engaging with literature and stories. One of the possible ways how to use several of these stories, could be, due to their multilingual versions, also in foreign language teaching.

3 Applications supporting creative writingThere exist applications, whose aim is to support user´s creativity by the means of creative writing. Many apps are used for recording ideas in form of quick notes (either by typing or even handwriting), but the focus of this paper is on those that are listed among poetry and creative writing apps. These apps can on one hand be oriented at younger users, like an app A Story Before Bed. This app lets the user “record a children’s book online with audio and video.“20 Thanks to this app, children can also play back and listen or watch their recordings on their digital de-vices. On the other hand, there exist the apps for adults that try to en-hance their creativity by enabling them to write and share their poetry or prose and get some comments or feedback from other users of these apps. Among them are apps like Poet’s Corner by Wild Notion Labs. These apps follow the tradition of web-based literary servers, where the feedback depends on the quality of the piece but the percentage of responsiveness is influenced by the number of pieces on the server.

An interesting app that presents creating poetry with formal restric-tions, is Refrigerator Poetry by WBPhoto, a remediation of poetry mag-nets – magnets with text that one should organize into a poem and place them, most commonly, on a refrigerator (hence the term). But besides choosing from the “pre-made” words (as is the case with tradi-tional poetry magnets), in this app one can also add her own words or phrases by typing, or through voice (via Android’s voice recognition). Applications for creating fridge poetry exist also for Apple devices, like the app Poetry Magnets by King Software Design.

20 A Story Before Bed, online.

93

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

Apart from the main aim of apps for creative writing, which is offer-ing the novice and amateur writers a virtual space for presentation and quick and instant feedback, they also tend to create a community that could help writers write more and better, or even to have more fun. There are also many apps that should help with the creative writing process, like apps for constructing a better meter, for rhyming, diction-aries and so on.

4 Applications remediating print literary works Application markets list a great number of applications that remediate the print literary works. These are mostly applications bringing some canonical poems or short stories. The function of these apps is very often to bring literature to the contemporary reader, reading while us-ing all kinds of transportation and in all types of situations. One can find among these an app called Poetry from the Poetry Foundation (that also allows the readers to create their own poems), The Poetry App by Josephine Hart Poetry Foundation lists over a hundred poems by six-teen well-known poets. Here the poems are accompanied by video and audio narrations from actors. There are also apps Poetry Series: Robert Frost, Poetry Series: Walt Whitman. Furthermore, the works of Shake-speare can be downloaded as well.

Literary applications concentrate besides poetry also on short stories, like the app A story a day, where the reader finds the stories by the Anglophone authors Oscar Wilde, Virginia Woolf, Sherwood Ander-son, Nathaniel Hawthorne, W. W. Jacobs and O. Henry. Among many others, there are apps for reading fictions by Charles Dickens, E.A. Poe, Anton Chekhov, Ambrose Bierce. The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Arabian Nights also exist in mobile literary forms. Application IPoe pre-sents different stories of Edgar Allan Poe plus Poe’s biography, where the reader can choose the language of the stories to be English, Spanish, or French.

A very interesting example is Dave Morris’ adaptation of Mary Shel-ley’s Frankenstein. Morris’ interactive novel Frankenstein was designed and developed for iOS by inkle and published by Profile Books in 2012. This version of Frankenstein is written in small fragments accompanied by drawn-like illustrations. After each fragment, the reader has a sim-

94

Z. Husárová

ple choice, she should make “decisions that don’t interfere with the reading flow, but over time will shape and mould the way the story is told.“21 The reader is presented with two or three small titles (some-times sentences or questions) that when clicked on, contain some extra information about the particular narrative fragment.

Beside the entertainment function, these poetry and prose apps can also have an educational purpose – to educate the reader in poetry or prose and bring the older works (thanks to the multimedia elements and interactive design) closer to the contemporary reader. As is written in the info about The Poetry App, these apps are for “the poetry nov-ice - explore the power of poetry through the narrations of world-class actors“22. It seems that the purpose of remediation of print based, older literary works into mobile platforms is to keep the reader “literate“ in the literary field, to provide an easy and cheap access to (even whole collections of) literary works and also to send a message that even the older literature can be still considered “cool“ and up-to-date, if you use the new medium and aim at the suitable target-group.

Some different examples of how print literature can be remediated, provide the following literary apps: Composition No. 1, Humument and Obvia Gaude. Composition No.1, originally a piece of shuffle literature by a French author Marc Saporta from 1962, was in 2011 reedited by Visual Editions, who released it, based on the original, in a format of loose leaves plus on the iPad. To bring the reader an experience of shuffling through loose pages on the mobile device, Visual Editions decided to present the reader with pages that constantly run on the screen, one after the other, in extremely fast tempo. In order to stop this instant flow and be able to actually read the text, one has to hold a finger on the screen. Tom Phillips, an author of artist´s book Humument (which is an alteration of a Victorian novel A Human Document by W.H. Mallock, in which Phillips treated every page either by painting, collage and/or cut-up techniques), decided to create an iPad version of Humument, for which he created 52 new pages and added them to the previous-

21 Frankenstein, online.22 The Poetry App, online.

95

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

ly print-published 367 pages. This app has also an “interactive oracle function“, which “casts two pages to be read in tandem.“23

Figure 5. Humument by Tom Phillips

Both of these works use combinatory functions to add the random ef-fect to the stable number of pages. The random choice of certain com-binations can produce amusement, but usually does not change the overall narrative24.

App Obvia Gaude by Ľubomír Panák, in collaboration with Zuzana Husárová, remediates a Slovak Baroque literary text in Latin – a wed-ding wish in the form of a pattern poem “Decagrammaton” by a Slovak

23 Humument, online.24 For more on Shuffle literature, see Husárová/Montfort 2012.

96

Z. Husárová

poet Matej Gažúr from 1649. This remediation enables people to use it as their own wedding wishes: to change the original names of the newlyweds (Evula, Paulo) and add there the names of their friends or family. The touch gesture rotates, twists and turns the black and red letters in 3D space (there are 4 distinctive screen areas) and triggers dif-ferent combinations of digitalized Baroque music samples. By shaking the mobile device, the letters start flying and disperse.

It seems obvious that the mobile market found its custom-base also with the reading users. The combination of the print and mobile is on the rise, as prove the projects like Brief by Alexandra Chasin published by Jaded Ibis Productions, where the print book and an app were re-leased simultaneously. In cases like this, it is important that the authors and publishers think about how to incorporate the platform possibili-ties into the version. Brief could serve as one of the playful examples: by the shake of the mobile device, the algorithm in the app chooses some of more than 700 pictures, randomly locates them on the page and wraps the text around them. This concept of randomization of pic-tures is not arbitrary, it corresponds with the story-line.

5 Applications on multiple digital platformsThere are several apps, where it is not clear what came first, whether the online version or the mobile device app – maybe they were even released simultaneously. Therefore, we will not treat them as typical remediations. However, the remediating character can be very often attributed to the use of touch – touch is often incorporated in the very same principle as the mouse-click in digital interactivity – to make something happen, to trigger the action. Touch gesture in those cases does not have a semantic potential, but is merely a button-trigger. One of the examples of these is a provoking audible experience The Use by Chris Mann25 (also in web format), where the reader activates Mann´s readings of texts and his video recordings by clicking on any of the presented dots and thus gets a phonic “noise-scape”.

25 For more on this app, read the blog post “The Use” by Chris Mann by Leonardo Flores, 2012.

97

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

Quite an interesting example of the use of more platforms for sto-ry-telling, is the project Immobilité by Mark Amerika. Immobilité is the name of the film (that was displayed also in the gallery environment) plus mobile versions. According to the information about the applica-tion: “Immobilité is a remix of stills, subtitles, and original audio from the film Immobilité, generally considered the first-ever feature length art-house film shot entirely on mobile phone.“26 This piece was filmed in Cornwall and belongs to Mark America´s Foreign Film Series. The music was composed by Chad Mossholder, who created also the audio remixes. In the mobile application, the textual screens are followed by the photographic ones, and the touch triggers new screen. It thus cre-ates a dialogue between the black and white textual screens (sentences in white colour on black screen) and the colourful visual, photograph-ic material. Mark America works here with his concept of “remixolo-gy”, stating that “we are all born to remix. What are dreams and active memories if not personally rendered remixes of multi-media source material?“27 Application is thus one of the remixed versions of the film, the other versions are called Mobile Remixes. So far, these six video and audio remixes were created: Trail(er) Mix and An Image Coming (Spatial Remix) by Mark Amerika and Chad Mossholder, Audiologues (5) and An Image Coming (Spatial Remix II) by Chad Mossholder, Deep Interior (Unconscious Remix) by Rick Silva and Hauntological (A Digital Remix) by DJ RABBI. According to the website, these remixes are “extensions of the dreamlike source material that keeps circulating throughout the various iterations of the project.“28

Andreas Müller´s For All Seasons, initially programmed for Windows PC, now running also on iOS, uses reader´s movement to correspond with the meaning of the displayed text. This work presents author´s memories connected with four seasons. At the beginning of each season, the reader gets a one-page narrative that vanishes or leans down and its semantic content materializes itself into a graphic form. In Spring, ani-mated dandelions spring from the ground with flowers made of text, in Summer, animated text-fish swim on the screen, in Autumn, text-leaves

26 Immobilité, online.27 Immobilité, Remixes. online. 28 Ibid.

98

Z. Husárová

make a whirl and in Winter, it snows text-flakes. The touch gesture on the mobile devices works very similarly as the mouse movement on the PC – animations change to some degree based on reader´s input. Dan-delions turn according to dragged trajectory, text-fish and text-whirl disperse, text-flakes fall quicker on the place assigned by touching a circle.

P.o.E.M.M. (The Poemms for Excitable Media Poetry for Excitable [Mobile] Media) Cycle is a project by Jason Edward Lewis and Bruno Nadeau that consists of 8 multi-platform poems projects (the final number will be 10), each of which is playable as mobile app and as installation on big screens, some have also big print components. Until now, there are 5 poems that have both the installation version and the mobile version: What They Speak When They Speak to Me (app called Speak), Buzz Aldrin Doesn’t Know Any Better (app called Know), The Great Migration (app called Migration), Smooth Second Bastard (app called Bastard), No Choice About the Terminology (app called No Choice About the Terminology). The other three poems (The Summer the Rattlesnakes Came, The World Was White, The World That Surrounds You Wants Your Death) are now only in the installation versions.

The text in all of the poems reacts to touch gesture with two hands, and the principle of interaction as well as the whole poetics and aes-thetics are the same in apps and in versions for installations. Touch-ing of the screen (looking like a lake of white letters in black water) in What They Speak When They Speak to Me activates at first one letter, then other letters and words that gradually form a chain – a line of poetry. Touching the screen of Buzz Aldrin Doesn’t Know Any Better, highlights the touched words from the white textual cloud. The text of this work brings a conversation with Pretty Jesus about the contents of the pawn shop display in San Francisco. The Great Migration brings the migration of several visual/textual creatures, looking a bit like sperms but with several tails made of poetry lines, that when touched, release the text on the screen. Smooth Second Bastard uses the concept of blank canvas that when touched, visualize the text in the point of the touch. No Choice About the Terminology presents the text in several moving lines (some to the right, some to the left), covering the screen from top to bottom, from left to right. In order to interact with the text, the user must touch

99

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

a letter of one of the lines, which changes its colour and the line gets bigger. The longer one holds the letter, the bigger it gets – transparently covering the rest of the screen.

Figure 6. Speak by Jason Lewis

The idea that connects these 5 poems is questioning one´s identity and ontology, questioning where one comes from, his/her roots and migra-tory routes. The poems of the project also interrogate human commu-nication and epistemological thinking. All of these poems were written by Jason Lewis, who poeticized his own pondering about these themes. He used his individual experience, into which his individual (hi)sto-ry, ontology, understanding and self-concept were inscribed. But these apps offer more than the poems categorized as Version 1:: Mobile and presented also as installations (Version 0). When interacting with these apps, the reader can choose one of the five listed poems in the menu (Version 2:: Anthology), written by five poets, and a different text ap-pears. One can also write her own text or choose a Twitter feed for a customized version of the app (Version 3:: Platform). The user can also share her creation with other owners of the app (Version 4 :: Share) and the work is released under an open source licence (Version 5 :: Open).

100

Z. Husárová

P.o.E.M.M. Cycle uses the gesture of touch as a connecting mecha-nism between the poem and the reader. This mechanism lets the reader grasp the poem, in both physical and cognitive sense. The textual and visual semantics function as mutually cooperating content vehicles, and the semantics of touch gesture (different in each poem and always corresponding to the overall meaning) even contributes to user´s im-mersive poetic experience.

The principle of publishing works on multiple platforms seems to be reaching beside the artistic community also the broader marketing interests. One of the examples of marketing strategies is a serial nov-el Apocalypsis by Mario Giordano, published in weekly instalments, always as an app, an e-book and for audio download. This, so called “diginovel“ (the description as it was promoted) with crime theme, consists of electronic text pages, as in e-books, where the user virtually “thumbs through them.” The project consists also of multimedia con-tent – short non-interactive videos that demonstrate the textual content, plus the reader receives pop-up messages. However, the user´s interac-tivity is very limited – she just goes through the content.

6 Interactive narrative applicationsIt is an interactive toy... or rather poem... or artwork...

Andrew Plotkin29

With the rise of the application market, several authors started to think about how to create innovative ways of story-reading experience. Here will be discussed the interactive novels, in which the authors wrote the piece directly and only for the mobile media. Thus can be considered as “mobile digital born“ stories.

Several authors saw in the mobile platforms an opportunity how to bring the genre of interactive fiction (or IF, traditionally text-based games called also text adventures) into new environment and how to reach new audiences. There are even several apps that bring the works of modern IF authors to mobile devices, e.g.: Z-Machine Preservation Project (ZMPP), JFrotz. A well-know interactive fiction author, Andrew Plotkin, says that “if there is actually an audience [on the App Store]

29 My Secret Hideout, online.

101

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

outside of people who are gamers, then it will be people who are inter-ested in interesting stories.“30 Andrew Plotkin´s IF games, programmed originally for computers: Shade, The Dreamhold, Hoist Sail for the Helio-pause and Home can be now found in the App Store. Besides these reme-diations, he also created for mobile market “an interactive textual art generator set in a treehouse“31 – My Secret Hideout. This app, in which the reader “grows” a hideout tree from the building icons, adds to every change of a tree shape a short narrative that describes “my secret hideout”. This narrative is based on the combinatory principle – with every newly added icon, some sentence changes.

Michael Berlyn is along with Plotkin another “heir of Infocom“32, author of many interactive fictions (the most famous are Zork, Infidel, Cutthroat) that now creates interactive stories for iPads and iPhones. His works The Art of Murder, Carnival of Death: Grok the Monkey and Reconstructing Remy: An Interactive Novel (that he names “Flexible Tales – Creators of re-imagined storytelling”33 and on which he collaborates with Muffy Berlyn) are available from App Store and Windows Store. They all combine multimedia elements with strong emphasis on the story development. Reader´s interaction with the story is based on tap-ping or clicking on the screen. In The Art of Murder, the reader is sup-posed to adopt the role of a detective: to solve the murder mystery of a young woman Lola by questioning the characters and investigating into the whole case. Carnival of Death: Grok the Monkey also plays upon the theme of murder and investigation – in this case with the back-ground of circus setting. Their newest product, Reconstructing Remy, is based on the story of Remy´s disappearance and the reader should find out about what happened through interacting with the elements on the screen. In Berlyns´ mobile application stories, the reader´s function is different from the function of “interactor” in IF. In the mobile apps, the reader usually taps on the objects, in IF, she usually types commands and the programme accepts the interactor´s natural-language input. Nick Montfort defines the processes in IF as:

30 Andrew Plotkin in Alexander 2013.31 My Secret Hideout, online.32 Reimer 2013.33 For more information, see the website: http://www.flexibletales.com/index.html

102

Z. Husárová

“In response to this input, usually a command to the main character in the story, actions and events transpire in a simulated world and text is produced to indicate what has happened. Then, unless the character has progressed to some conclusion of the story, the operator is allowed to provide more input and the cycle continues.“34

However, there are some similarities between the mobile apps and IF by Berlyns. In the Berlyns´ apps, the reader is often presented with a place (e.g. a room), where several objects are to be touched, through which the reader should gradually learn/inquire the story. The rea-der plays a detective role, trying to solve the mystery. This exploratory principle is sometimes similar to the interactor´s function when playing IF. However, as stated above, the interaction (typing natural language input in IF vs. tapping/clicking in apps) is different.

In comparison to Berlyns´ exploratory use of interactive objects and text, the watermarks in Amanda Havard´s interactive book The Survi-vors (she calls her edition “Immersedition”) function to provide addi-tional visual or textual material about the characters, places, etc. This interactive book resembles the traditional e-book format, only with the extended, hypertext-like, use of text to provide additional information. The function of tapping on the text is here of a metatextual nature: the reader can read snippets from “author’s and character’s mind.“35

The difference between these formats is embedded already in their titles/descriptions. Reconstructing Remy is referred to as an interactive novel, while The Survivors as an interactive book. It seems that the term “book“ used in connection with “interactive” or “e-“, evokes the incli-nation towards a traditional codex format – the readers thumb through the virtual pages, the text is written in a similar way as in the print for-mat – and does not distinguish the genre. When considering the term “interactive novel“, we could think of an interactive literary genre that tries to keep faithful to some characteristics of the genre of novel: if not the length of the text, then the developed plot structure, number of characters, function of a narrator, perspective, temporal and spatial di-mension. Even though a generally more strict differentiation of formats

34 Montfort 2001.35 The Survivors, online.

103

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

could be suitable for a more synoptic and organized users’ search for kinds of interactive stories forms, it seems that in reality the difference between interactive books and interactive novels (due to a lack of prop-er categorization) is solely based on the author´s choice or preference.

Another example of the use of interactive platform for story-telling is Jeff Gomez´s interactive novel Beside Myself. Beside Myself presents the readers with three different Jeff Gomezes: a single one, a married one and one with a family. All three doppelgangers discover one another and start to communicate. The content of the story is formed by longer text passages accompanied by music, communication through email by characters or author, integration of social media, photos and interactive menus. The creators of this story (Jeff Gomez is responsible for text and design, Rolando Garcia did the programming and app development) intertwined the content of the story with the technological possibilities (N. Katherine Hayles´s idea of a technotext):

“The contents of Beside Myself can be shuffled, chapters can be programmed like a playlist, or the reader can follow one Jeff at a time throughout the story (with the ability to read the story again from the point of view of a different Jeff, seeing the novel’s events from another perspective as well as being served up an alternate ending).“36

Having based the interactive novel on the doppelganger story (simi-lar story idea can be found also in hypertextual fiction Subway Story37 by David M. Yun), where the reader can shuffle the story and choo-se different perspectives (multi-sequential element), even use email and social networks, was a choice that could not be that smoothly and sophistically done in the print format. The creators were thus able to develop a story that suits a digital format and uses its potential. The question connected with interactive novels in general, is why the aut-hors have not created the stories in the hypertext/hypermedia format? Is it because hypertext fictions have not reached a broader readership beyond the university milieu? Is it because this platform was not attrac-tive enough? Is it because it did not provide enough flexibility, touch

36 Beside Myself, online.37 Subway Story, online.

105

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

gesture and moveability? Is it because the mobile apps markets are now so wide-spread that authors want to be part of this paradigm?

It is too early now to be able to answer these questions. Whatever the general reasons of moving to the mobile platforms are, it seems that the electronic literature on the tablets has its future. And according to the contemporary trends, it seems that the future of interactive novels might be much brighter than the future of hypertext fictions.

7 Interactive poetic applicationsare you the directlr[tv]uees? just do x,y,z! smarter zzzz...! forever mracn!

cerna that make the rgse! you ubik poor bastard! it is about rudopcnetwork not arius! lighten laziikly! iveta would taste to ispernetvdpib!

and-or (René Bauer, Beat Suter and Mirjam Weder): andorDada

The field of interactive mobile applications whose content is poetic, is formed also by those authors who created in the area of innovative poetics even before the rise of mobile market. Many of the authors in this field engaged themselves with various modes of digital poetry or digital writing (Jörg Piringer, Andy Campbell, Mez Breeze, Eric Loyer, Jason Lewis and Bruno Nadeau, Beat Suter, René Bauer, Mirjam Weder, Johannes Auer, Aya Karpińska). This fact contributed to the quality and status of the interactive poetry apps. Many of the poetic applications combine different media and use the touch gesture in a new way. Ho-wever, there are still those that use the touch gesture only to trigger new screen.

Here we will discuss the mobile born digital poetic applications, where the reader interacts with the kinetic digital text in various ges-tural forms that go beyond the gestures of touch and tap. We focus only on those that were created only for the mobile market and are neither remediations of print formats, nor remediations of digital works, origi-nally created for PCs or Mac computers. The aim is to look into specifics of mobile poetics, which can be different from the web-based pieces that do not work with touch gesture. Those apps will be introduced and shortly analyzed, whose authors contextually work even with the gestural semantics and make the process of reader´s touch relevant to the concept of the whole piece. Another studied group of the poetic apps consists of those works that make use of the generative textuality/

106

Z. Husárová

visuality/musicality for poetic purposes and those that also make use of the performative poetics – but all of them still stress the gestural poetics and can thus be regarded as technotexts.

7.1 Apps with Generative Poetics The principle of generative poetics has been connected with digital poetry, therefore it is quite understandable that it appears also in the mobile applications. The generative principle can work on different levels – from having the results of the generative processes be the final product (as is the case in the work Spine Sonnets by Jody Zellen, where the app generates a poem from the book titles), to the projects that use the results of real-time processuality as a material for further develop-ment. The Swiss, Zurich-based artgroup “and-or” consists of René Bau-er, Beat Suter and Mirjam Weder. In their three locative mobile apps: andorDada, sniff_jazzbox.audible city, wardive, they transform the imme-diate “wlan waves environment“ into the poetic medium. Their apps capture the names of the wlan waves and according to different prin-ciples use them to make generative poems. The app andorDada allows the user to initially choose between four modes: clear, copypaste, story, instant poem. At the bottom of the screen, the user sees a list of the actual hotspots around her, which the app takes and uses as one of the source texts for the poems. The reader gets a poem of generated sen-tences, while a female voice synthesizer “utters” the text. Very amusing is the fact that also the reader´s clicks on any of the modes are orally presented. This dadaistic poetic app writes and speaks to the reader in a multilingual way, where the names of the hotspots “enliven” and get performed as poetic elements in different syntactic positions.

Sniff_jazzbox, created in collaboration with Johannes Auer, transforms the titles of the hotspots into music. After opening the app, the user sees a playing musical score with the titles of hotspots under the score. The programme recognizes the letters of the hotspot titles and transforms them into playable tones of the musical notation system. One of seven different themes can be chosen as the underlying component: waiting, walk, riding a bus, classic, jazz, trance, random. Besides this, the user can choose one of the playing instruments at a time: organ, drums,

107

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

bass, piano, flute, string, singleton, penta. At the bottom, a flickering list of the hotspots appears.

The app wardive asks the user to play a game: to protect a crystal from the attack of the hotspots that appear in the vicinity of the mobile device. The hotspots materialize in the form of triangles that fall from

Figure 8. andorDada by and-or.ch

108

Z. Husárová

various corners of the screen and try to reach the crystal in the centre of the screen. All these three apps are on the authors´ website categorized as “adaptive games with locative levels“38. All three were first released for Apple customers, but after Apple rejected the used IPA, authors decided to place them on Google Play market for free. All these apps approach the hotspot names as a “subconscious expression of the pres-ently existing communication networks.“39 By generating the hotspot titles into poetry/audio/game elements, they approach this information as a source of artistic expression. They poeticize/musicalize/gamify the hotspot titles, for the users not only to realize their presence, but also to think about their potence/potential. The titles do not refer just to the occurence of wlan waves, and thus to the presence of Internet signal, but here, decontextualized, they become signifiers of a different reality: of the people that stand behind those names, of the places that stand behind those descriptions, of other relations. The Situationist effect can be applied here, as dérive – in the sense of creating a new and authentic experience from walking the everyday routine, as well as in the sense of placing the actual descriptive information into a new artistic context.

7.2 Apps with Gestural PoeticsNotice me, notice me

Eric Loyer40

The concept of coded language that creates a texture around us is present also in the application #Carnivast by Mez Breeze and Andy Campbell. Here, however, the text is not generated, but is created by “textscaped micro-environments (or immersive 3D Segments)41” that respond to one´s touching any point on the screen, as well as to a zoom gesture. Text is written in Mez Breeze´s “Mezangelle”, which is a code poetry language, a creolized language that combines human language and programming language terminology. When the reader clicks on the symbol “[]“, she gets a hexagonal text room, where the whole nar-

38 For more information, see the website by and-or.ch , 2012.39 sniff_jazzbox.audible city, online.40 Strange Rain, text from the piece.41 #Carnivast, information about the downloaded piece.

109

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

rative can be read in Mezangelle and also in English. The whole screen is interactive – touching the screen on a particular place triggers a re-sponse corresponding to that place, zooming into a particular textual part, word or letter.

The whole work consists of three different segments, “landscapes” or “nests”: 1.1, 1.2, 1.3. Each of the segments is differently coloured (yel-low/orange, yellow/light green, red) and creates different geometric 3D shapes. By touching the visual-textual sphere, composed, in each segment, of several layers of the same textual material, one gets deep-er and deeper into the metaphorical core of the textual “space.” The text rotates, expands and shrinks, depending on reader´s interactivity. Atmospheric music accompanies the textual-visual experience as well. According to instructions, one can “touchswipe to swivel around and pinch to zoom in and out”42. The visualized text of each part tells one fragment of a story. In the first part, 1.1: # [Parent – Primary 1st Layer Nest = Miss N. Abyme], one gets to know the main character Miss N. Abyme, who, during her party, received as gifts “all engineered state – o´– the – art geophysical objects“. This “nest” is created by mild yellow/orange background and yellow and black textual patterns. The second “nest” 1.2 consists of yellow/light green background and black text forming flying cubes and textual “walls”. The third “nest” 1.3 is red with black text and creates a shape of a ball with a darker shadow. The fragmented text tells a story about Parent Miss N. Abyme (in 1.1) and her two children: # [C(LoneC)hild1 – 2nd Layer Nesting = Txt]: (in 1.2) and [C(LoneC)hild2 – 3rd Layer Nesting = I#Mage]: (in 1.3). Text about each of the “characters” creates one “nest”. The authors interestingly play here with polysemantics of the expres-sions “parent” and “child” (in the semantic context denotating family relations, but as object superordinate to another subordinate object in the programming languages). Miss N. Abyme is obviously a language play on mise en abyme, a formal technique, where a recursive sequence occurs, or where an image contains a smaller copy of itself, or is a ref-erence to intertextuality of language. The recursivity of the text hap-pens in each of the parts – the reader gets deeper and deeper and gets

42 Ibid.

110

Z. Husárová

still the same text, only zoomed in. The concept of an element contain-ing a smaller copy of itself is referenced by the duality of parent and children and expressed in this sentence at the end of 1.3: “Mise_en_aby#me_mirrored back in glorious st#Amplified genecode.” The inter-textuality is here approached by the mutual influence of human lan-guage and code in mezangelle.

Considering the title Carnivast, several interpretational possibilities could be applied. If we think about “carnival + vast”, the story about the parent, clone child1 called text and clone child2 called image, Carnivast could be understood as their vast party, where they take on masks that shade their true identity (the story even opens with Miss N. Abyme´s party). If we think about “carnivore + vast”, we could have a story, where the parent plundered the nests of clone children (and maybe ate them) to gain their qualities. And maybe the reader is a “carnivore”, who “consumes” the living text and image to satisfy her hunger for experience.

The reading and interacting with Aya Karpińska´s app Shadows Nev-er Sleep, “a zoom narrative”, as she subtitles it, is also based on the

Figure 9. #Carnivast, 1.3 by Mez Breeze and Andy Campbell

111

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

zoom gesture. But in this case, zooming is not the way how to “travel through” 3D textscapes, but rather the way of navigating through the app. The work consists of three sequences – the first one with author´s photo when lying with a shadow above her and visual text saying: “We go to bed we close our eyes but shadows never sleep/Up they go, and out they go/Shadows never sleep...”43 The zooming function gets the reader to a grid consisting of 3x3 squares with the blank central square. Each square combines a white female figure (a personalization of Shad-ow) with a text. After using the zoom gesture again, each of the pre-vious squares turns into nine squares with a blank one in the centre. Since the very central one is blank, the reader gets 64 black squares with variously opaque white visual text. Small visual textual parts are based on the theme of shadows, some of them are written in interrogative or exclamatory form. The black and white aesthetics of the grid reminds one of a (board) game, but in this app, there is no assigned way how to “traverse” through the space of the visual-textual field. The use of children-stylized language, the visual style of both text and the drawn figures, reminds one, due to its repetitive structure and the formal sim-plicity, of bedtime stories or nursery rhymes and creates the feeling of easily approachable narrative poems or prose poetry. The zoom gesture corresponds with the overall poetics – reminding the reader of zooming into the dreams, into the unconscious and unknown, of get-ting deeper inside.

Eric Loyer´s app Strange Rain is playable in three modes: wordless, whispers and story, each of them with soothing, atmospheric music. Since this part of the paper deals with poetry applications, only the story mode will be looked at44. The screen presents a hand-held cam-era-like perspective showing an imaginary sky with raindrops falling on the “glass”. The touch of the finger on raindrops activates the text – the thoughts of a narrator going through a family crisis (his sister´s accident), standing in the rain, thinking in his backyard, not wanting to return back inside. The text is either black or white, and as the reader

43 Shadows Never Sleep, online.44 “Wordless” mode presents falling rain with atmospheric music and “whispers”

presents the same perspective but when one touches the raindrops, the words “fall“ or “drop“ appear.

112

Z. Husárová

touches more and more thoughts, she uncovers other layers that are present in the sky. There is also an airplane flying and the more the user touches the raindrops, the more explanations about what hap-pened and what the narrator ponders about, the user gets. The touch momentum in this app is not aimed just at moving new parts of the sto-ry forward (as one can traditionally see in the apps that use an arrow, a gesture in the mobile devices that replaces the mouse-click), but be-sides revealing new sentences, it works also as touching in the sense of familiarizing – familiarizing with narrator´s cognition, with the nature of this sky and its layers. Also, the touch never reveals the same text at the same place of touch. The touch gesture works generatively, maybe wanting to bring the idea of associative mind processes. Raindrops that fall from the sky carry narrator´s thoughts – but they need a reader to get to know them by her touch. Otherwise, the story is but poten-tial. Each “stage” of the app brings new words and sentences when the raindrops are touched. At the final stages, the reader seems to get into the narrator´s mind – the sky layers flash and the airplane flies in the middle. He talks to a God-like being, pleading: “Notice me, notice me”. And also two lines of thoughts appear in the app: “The strange becomes familiar,” “and the familiar, strange”. It could be deduced that the narrator´s standing in this Strange Rain can be an attempt to under-stand how to deal with his sister´s amnesia after the accident. As the tool of this understanding, he chose his complete soaking in the rain. Therefore, raindrops here represent not only the magical elements of his thoughts, but since they fall from the sky, they can be interpreted also as metaphysical media that should help the narrator in his difficult situation. The search for soothing is thus both physical, emotional and intellectual (“I am going to need an explanation”).

7.3 Apps with Performative PoeticsTwo lettrist-like applications by an Austrian sound and media artist Jörg Piringer, abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz and konsonant, explore the qualities of letters, their visual and sonic presentations and accent the artistic potential of letter combinations. Jörg Piringer is also known as a performer, video, sound, software and hardware artist, one of whose main domains is a concrete sound/visual performativeness of letters.

113

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

The performative aspect of letter concretization is the main drive be-hind both, his performances and his applications. In abcdefghijklm-nopqrstuvwxyz (2010), the reader meets with “tiny sound-creatures in the shape of letters“45 that travel through the screen and turn it into the soundscape and textscape. The choice of each letter sets off its sonic presentation and the combination of the letters on the screen sparks off a concrete lettrist noise “concerto”. The user can switch between four sound modes: gravity (constantly sounding letters bump into the borders of the screen), crickets (letters “speak” only in the clusters with other letters), vehicles (sounds and visuals of letters remind one of the characteristics of transport machines), birds (letters’ visual and sound features remind one of the bird sounds and their flight lines). In all of these modes, the reader can switch the bomb icon to blow the letters out. The letters in all the modes create a distinctive visual trajectory that maps their movement on the screen by leaving behind a shadow of their trajectory.

Figure 10. konsonant by Jörg Piringer.

konsonant is similar to the previous app in the way how the letters (through implementation of their articulation/sonification) become lit-tle but powerful sound machines that produce resonating noise effects.

45 abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz, online.

114

Z. Husárová

In konsonant, not the whole alphabet is at stake, but the focus is on the consonants (even though some vowels are present). There is also a choice of one of four modes/games that define the consonant´s be-haviour: “sound organisms” (M,N,O) follow user´s drawn line, in the other game, the user can “control the letter cloud” (the red flash-ing letters are H, X, Z), the letters from the “R” group, with different accents on R move on a grid according to user´s decisions. In the last game, one can “build machines” from big letters (by touching a screen at any point), control their movement and the little letters, falling from an opening, then sit on the “statues” made of bigger letters. When one shakes the device, they disperse on the screen.

The poetic and aesthetic current of both Piringer´s apps is embed-ded in the bodies of the letters and their performative dimension. Piringer makes the letters and their combinations speak (by artic-ulating their sounds) and makes the letters visually present and in motion by the interactive design (incorporating mostly just the ty-pography). The influence of sound poetry, concrete, visual, kinet-ic and digital poetry is felt in these apps, and Piringer created an exquisite example of how nothing but the concrete representation of the letter-bodies can bring the aesthetic, playful and poetic experi-ence that is always responsive to user´s choice of letters. Besides this performative poetics, his apps are a wonderful example of gestural poetics – the concept of touching the words and thus turning them into active “bodies”, is the core principle of all the literary mobile applications. But in comparison with other mobile apps, where peo-ple touch the electronic pages or arrows that allow the readers read bigger text amount but not individual letters, Piringer´s apps work with macro-poetics and force the readers to concentrate on the spec-ificity of each sign. Maybe, after understanding the features of each particular letter (by playing with it), the readers would be able to treat the words, sentences and pages with different criteria.

115

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

8 ConclusionWe believe that significant, sustained investigation of the writing and design possibilities of such devices will lead to new forms of electronic literature that

will be compelling, provocative and delightful.Jason Edward Lewis and Bruno Nadeau46

This belief, articulated by Jason Lewis and Bruno Nadeau, has already come true, mostly with those poetically gifted media poets and artists in the creative mobile apps industry that both make a research into in-teractive poetics and design and are familiar with the principles and characteristics of electronic literature. It seems that those authors who are consciously aware of the influence the experimental poetics (digi-tal poetry, concrete poetry, kinetic poetry, sound poetry, visual poetry) has on their works and who are able to shift the experimentations into new dimensions based on the contemporary technology and media, can bring into the field of mobile apps new and fresh air, enrich the poetic and aesthetic criteria and treat the work as a whole. Every com-ponent of their work has its specific position in the semantic complex.

This paper proposes a categorization of mobile literary applications, based on the differences in genre (poetry and narrative), in the source text (remediations or digital born), in the target group (apps for chil-dren), in the purpose (creative writing apps), and in the number of digi-tal platforms (multi-platform apps). This categorization is far from per-fect and even further from being finite. Its aim was rather to pinpoint a variety of literary mobile apps in the time when the paper was written, to sum up their specifics and to mention several examples. Regarding the used methodology, the paper leans on the media-specific analysis (proposed by N. Katherine Hayles), gestural features in connection with text and other media, on the aspect of intermediality and the as-pect of “technotext”. It is now too early to talk about genre analysis in connections with mobile apps, but perhaps in the future, even mobile apps will form specific and generally accepted genres.

The market of applications running on iOS and/or Android is on the rise – and the situation with the literary apps has not contradicted

46 P.o.E.M.M., online.

116

Z. Husárová

this trend. Although the number of literary apps is far smaller than the number of apps bringing quick and easy entertainment and simple games, the tendencies of bringing literature into the mobile market are becoming more and more present (both in the amateur creative poet-ry and in the “professional” apps). Several artists and publishers have decided to issue their works on multiple platforms – whether as print books and mobile apps or as web-based projects and mobile apps.

The paper shows that even though many of the applications provide interesting content with attractive visual design and profound poet-ics, not that many really concentrate on the innovative use of user´s gestures. The ways of interacting with the work should stem from the content of the work and the gestures should co-create the poetics of the piece. Only then one can talk about the “technotext” as N. Kather-ine Hayles defined it. Regarding the studied examples and categories, the paper shows that the apps on multiple digital platforms (mostly those by Jason Lewis and Bruno Nadeau) and interactive poetic apps (either with gestural poetics, generative poetics or performative poet-ics) are able to make the best use of the interactive gestures and thus use those elements that cannot be implemented into any other poetic form. According to the contemporary situation in the field of mobile literary apps, it seems that the authors of poetic mobile apps use kinet-ics and playful potential of digital text to a more innovative extent and use them to create “technotexts” more frequently than the authors do with interactive novels. This is quite understandable, regarding the fact that poems are much shorter than the developed narrative, and therefore the author´s task of keeping the reader “entertained”, could be easier, since the extent of poems allows only small, but an intensive number of interactive ways. However, with bigger formats, when read-ers know that the piece offers interactivity (and also regarding their experience with playing interactively-intense digital games), they often require more than just scrolling and thumbing through the pages, or simple video inclusion. The situation is different with publications, e.g. for Kindle. These publications do not state that they offer an enhanced reading experience based on interactivity, the focus is on the text itself, they are remediations of classic books.

117

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

Compared to the other senses, touch is the only sense that needs the person to be in physical contact with a thing or another person. Touch as the interhuman gesture creates a physical bond between peo-ple, a momentum of non-linguistic communication. Sensing the books through touch has been one of the reasons that people stated in the 1990s (the others were: I cannot take a computer to bed or to the beach), when talking about the positives of print books against the electronic literature. Now even the electronic literature can be touched – and un-like with the print text, the text on mobile devices can react accordingly.

The ancient Greek poetess Sappho wrote that you will remember those “many and beautiful things” we did in our youth. Now, the mo-bile literary apps have not even reached their metaphorical youth – it could be said that they are now in their infants phase. However, the mind of the contemporary Zeitgeist will probably remember them, thanks to its recording mechanisms. And it will definitely remember the more “beautiful” ones, the apps that touch both the artistic commu-nities and the general public.

Key-words: literary application, poetic application, interactive novel, interactive poetry, tablet, Android, iPad, iPhone, electronic literature, electronic books, sound poetry, visual poetry, concrete poetry, digital poetry, digital poetics

AcknowledgementsThis paper was written within a Grant UK by Zuzana Husárová 106/2013 “Transmedia approach to creative practice.”

BibliographyALEXANDER, L. (2013): Shade, and the future of interactive fiction on the

App Store. 12.2.2013. [cit. 2013-07-01]. Available at: <http://gamasutra.com/view/news/186263/Shade_and_the_future_of_interactive_fiction_on_the_App_Store.php>.

AND-OR.CH. shows, presentations, participations, speeches. 13.9.2012. [cit. 2013-07-01]. Available at: <http://www.and-or.ch/news.php>.

118

Z. Husárová

BARNSTONE, W. (2009): The Complete Poems of Sappho. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

BOGOST, I./MONTFORT, N. Platform Studies. [cit. 2013-07-01]. Available at: <http://platformstudies.com/>.

BOLTER, J.D./GRUSIN, R. (2000): Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

ELMCIP Seminar on Digital Textuality with/in Performance (2012). 3.5.2012 - 4.5.2012. [cit. 2013-07-01]. Available at: <http://elmcip.net/event/elmcip-seminar-digital-textuality-within-performance>.

EMERSON, L./RETTBERG, S (2012): iPhone and iPad E-Lit. In: ELMCIP Knowledge Base. 7.10.2012. [cit. 2013-05-10]. Available at: <http://elmcip.net/research-collection/iphone-and-ipad-e-lit>.

FLORES, L. (2012): “The Use” by Chris Mann. 24.7.2012. [cit. 2013-07-02]. Available at: <http://iloveepoetry.com/?p=295>.

GRIMSHAW, et. al. (2007): Electronic books: children’s reading and comprehension. In: British Journal of Educational Technology Volume 38, Issue 4, pages 583–599.

HAYLES, N. K. (2007): Electronic Literature: What is it? 1.2.2007. [cit. 2013-07-01]. Available at: < http://eliterature.org/pad/elp.html>.

HAYLES, N. K. (2004): Print Is Flat, Code Is Deep: The Importance of MediaSpecific Analysis. In Poetics Today Spring 2004. No. 1, Vol. 25, pp. 67-90.

HAYLES, N. K. (2003): Writing Machines. Cambridge, US: The MIT Press.HUSÁROVÁ, Z./MONTFORT, N. (2012): Shuffle Literature and the

Hand of Fate. In: Electronic Book Review. 05.08.2012. [cit. 2013-07-01]. Available at: <http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/shuffled>.

MANOVICH, L. Software Studies Initiative. [cit. 2013-07-02]. Available at: < http://lab.softwarestudies.com/>.

MARINO, M. C. (2006): Critical Code Studies. In: Electronic book review. 12.4.2006. [cit. 2013-07-02]. Available at: <http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/codology>.

MONTFORT, N. (2001): Cybertext Killed the Hypertext Star. In: Electronic book review. January 2001. [cit. 2013-07-02]. Available at: <http://www.altx.com/ebr/ebr11/11mon/index.html>.

119

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism report The Tablet Revolution and the Future of News. 26.10.2011. [cit. 2013-06-22]. Available at: <http://features.journalism.org/2011/10/25/tablet-revolution/>.

PISARSKI, M. (2013): Słownik Gatunków Literatury Cyfrowej - Powieść na smartfona. In: Husárová, Z./Marecki, P.: Digital literature of V4 Countries (presentation). 10.07.2013. [cit. 2013-07-08]. Available at: < http://prezi.com/wxkir63njmle/digital-literature-of-v4-countries/>.

PRIEST-DORMAN, G./PRIEST-DORMAN, C. (1999): Making and Using Waxed Tablets: Some Highlights in the History of Waxed Tablets. 1999. [cit. 2013-07-09]. Available at: <http://www.cs.vassar.edu/~capriest/tablets.html>.

REIMER, J. (2013): Heirs of Infocom: Where interactive fiction authors and games stand today. 23.6.2013. [cit. 2013-07-01]. Available at: <http://arstechnica.com/gaming/2013/06/heirs-of-infocom-where-interactive-fiction-authors-and-games-stand-today/>.

RETTBERG, S. (2011): To Read with Your Fingers: E-Lit for the iPad. 2011. [cit. 2013-07-09]. Available at: <http://elmcip.net/sites/default/files/files/attachments/criticalwriting/ipad_lit.pdf>.

SAMPLE, M. (2012): Strange Rain and the Poetics of Motion and Touch. 5.2.2012. [cit. 2013-07-01]. Available at: <http://www.samplereality.com/2012/02/05/strange-rain-and-the-poetics-of-motion-and-touch/>.

Creative Works Referenced:#Carnivast. Mez Breeze and Andy Campbell. Available at: <http://www.

dreamingmethods.com/store.html>.abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz. Jörg Piringer. Available at: <http://joerg.

piringer.net/index.php?href=abcdefg/abcdefg.xml&mtitle=projects>.Alice in New York. Atomic Antelope. Available at: <https://itunes.apple.

com/us/app/alice-in-new-york/id422073519>.Alice for the iPad. Atomic Antelope. Available at: <http://www.

atomicantelope.com/alice/>.andorDada. and-or.ch. Available at: <http://www.and-or.ch/andordada/>.Apocalypsis. Mario Giordano. Available at: <http://www.mariogiordano.

de/giopage/Apocalypsis.html>.

120

Z. Husárová

A Story Before Bed. A Jackson Fish Market Experience. Available at: <http://www.astorybeforebed.com/>.

Beside Myself. Jeff Gomez. Available at: <http://www.besidemyself.com/>.Brief. Alexandra Chasin, Jaded Ibis Productions. Available at: <http://

jadedibisproductions.com/alexandra-chasin/>.Carnival of Death: Grok the Monkey. Michael and Muffy Berlyn.

Available at: <http://www.flexibletales.com/index.html>.Composition No. 1. Visual Editions. Available at: <http://www.visual-

editions.com/our-books/composition-no-1>.Doll Play Books. Swan Media. Available at: <https://play.google.com/

store/apps/developer?id=Swan+Media&hl=en>.Hoist Sail for the Heliopause and Home. Andrew Plotkin. Available at:

<http://zarfhome.com/if.html#heliopause>.Fairy tales and storybooks. Whisper Arts. Available at: <https://play.

google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.whisperarts.tales>.For All Seasons. Andreas Müller. Available at: <http://www.hahakid.net/

forallseasons/forallseasons.html>.Frankenstein. Dave Morris, Inkle Studios, Profile Books. Available at:

<http://www.inklestudios.com/frankenstein>.Grimm’s Fairy Tales – 3D Classic Literature. StoryToys Entertainment

Limited. Available at: <https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/grimms-fairy-tales-3d-classic/id395323598>.

Humument. Tom Phillips. Available at: <http://tomphillipshumument.tumblr.com/>.

Immobilité. Mark Amerika. Available at: <https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/immobilite/id310425679?mt=8>.

Interactive Touch Books. Interactive Touch, Inc. Available at: <http://www.interactivetouchbooks.com/>.

iStoryBooks. iMarvel. Available at: <https://www.istorybooks.co/imarvel.html>.

JFrotz. ZaxMidlet. Available at: <http://sourceforge.net/projects/jfrotz/>.konsonant. Jörg Piringer. Available at: <http://joerg.piringer.net/index.

php?href=cds/konsonant.xml&mtitle=projects>.

121

Literature on Tablets: Poetics of Touch

My Secret Hideout. Andrew Plotkin. Available at: <http://zarfhome.com/hideout/>.

Obvia Gaude. Ľubomír Panák and Zuzana Husárová. Available at: <https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=net.delezu.obviagaudefinal>.

PlayTales. Genera Kids. Available at: <http://www.playtales.com/en/>.P.o.E.M.M. Jason E. Lewis and Bruno Nadeau. Available at: <http://www.

poemm.net/about/research.html>.The Poetry App. Josephine Hart Poetry Foundation. Available at: <https://

itunes.apple.com/us/app/the-poetry-app/id501967950?mt=8>.Poetry. Poetry Foundation. Available at: <http://www.poetryfoundation.

org/mobile/>.Poetry Magnets. King Software Design. Available at: <https://itunes.apple.

com/us/app/poetry-magnets/id369944301?mt=8>.Poet’s Corner. Wild Notion Labs. Available at: <https://play.google.com/

store/apps/details?id=com.wildnotion.poetscorner>.Read Unlimitedly! Kids’n Books SMARTEDUCATION, LTD. Available at:

<http://www.appszoom.com/android_applications/education/read-unlimitedly-kidsn-books_cmpna.html>.

Reconstructing Remy. Michael and Muffy Berlyn. Available at: <http://www.flexibletales.com/index.html>.

Refrigerator Poetry. WBPhoto. Available at: <http://www.appbrain.com/app/refrigerator-poetry-free/refrigerator.poetry.whiteboard.graphics.com>.

Sappho on a Pompeiian fresco. Via Wikimedia Commons. Available at: <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pompei_-_Sappho_-_MAN.jpg>.

Shade. Andrew Plotkin. Available at: <http://zarfhome.com/if.html#shade>.

Shadows Never Sleep. Aya Karpińska. Available at: <http://www.technekai.com/shadow/shadow.html>.

sniff_jazzbox. Audible city. and-or.ch & johannes auer. Available at: <http://www.and-or.ch/sniff_jazzbox_audible_city/>.

122

Z. Husárová

Spine Sonnets. Jody Zellen. Available at: <http://www.jodyzellen.com/apps/spine.html>.

StoryBooks. Joe Raj. Available at: <https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.storytell.fairylite>.

Story Time for Kids. Teknowledge Software. Available at: <http://www.storytimeforkids.info/app/>.

Strange Rain. Eric Loyer. Available at: <http://erikloyer.com/index.php/projects/detail/strange_rain/>.

Subway Story. D. M. Yun. Available at: <http://www.cyberartsweb.org/cpace/ht/dmyunfinal/frames.html>.

The Art of Murder. Michael and Muffy Berlyn. Available at: <http://www.flexibletales.com/index.html>.

The Dreamhold. Andrew Plotkin. Available at: <http://zarfhome.com/dreamhold/>.

The Survivors. Amanda Havard. Available at: <http://amandahavard.com/immersedition/>.

wardive. and-or.ch. Available at: <http://www.and-or.ch/wardive_android/>.

ZMPP: Z-Machine Preservation Project. Wei-ju Wu. Available at: <https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.boxofrats.zmpp4droid&hl=en>.