Literature in "Mind": H.G. Wells and the Evolution of the Mad Scientist

Transcript of Literature in "Mind": H.G. Wells and the Evolution of the Mad Scientist

Literature in "Mind": H. G. Wells and the Evolution of the Mad ScientistAuthor(s): Anne StilesSource: Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Apr., 2009), pp. 317-339Published by: University of Pennsylvania PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40208106 .

Accessed: 10/07/2014 19:01

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

University of Pennsylvania Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access toJournal of the History of Ideas.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Literature in Mind: H. G. Wells and the Evolution of the Mad Scientist

Anne Stiles

In 1893, H. G. Wells's article "Man of the Year Million" dramatically pre- dicted the distant evolutionary future of mankind:1

The descendents of man will nourish themselves by immersion in nutritive fluid. They will have enormous brains, liquid, soulful

eyes, and large hands, on which they will hop. No craggy nose will

they have, no vestigial ears; their mouths will be a small, perfectly round aperture, unanimal, like the evening star. Their whole mus- cular system will be shriveled to nothing, a dangling pendant to their minds.2

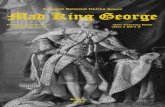

The editors at Punch evidently found this prediction hilarious, publishing a

poem and accompanying sketch ridiculing Wells's lopsided future humans

(Figure 1, p. 318). But not everyone was laughing. As ridiculous as Wells's bodiless, large-headed "human tadpoles" may

seem, they were based on the most rigorous evolutionary science of their

day. Wells, a lower-middle-class academic prodigy, received a prestigious

1 1 am grateful to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and to the University of California Humanities Research Institute for grants that enabled me to conduct the re- search presented here. Thanks are also due to my colleagues at the American Academy, Washington State University, and UCLA for their insightful feedback on early drafts. 2 Wells, "Man of the Year Million," paraphrased in Punch, "1,000,000 A.D." (Novem- ber 25, 1893), 250.

Copyright €> by Journal of the History of Ideas, Volume 70, Number 2 (April 2009)

317

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

FIGURE 1: "1,000,000 A.D.," Punch, or the London Charivari, 25 November 1893, 250.

318

1,000,000 A.D. ["The descendants of man will nourish themselves by immersion in nutritive

fluid. They will have enormous brains, liquid, soulful eyes, and large hands, on which they will hop. No craggy nose will they have, no vestigial ears ; their mouths will be a small, perfectly round aperture, unanimal, like the evening star. Their whole muscular system will be shrivelled to nothing, a dangling pendant to their minds.*'-- Pall Mall Gazette, abridged.]

^^^ { , r x What, a lnillion years hence,

m- \ i'i '' ' m la\ will become of the Genus m- ^few

\ i'i '• ' wm* m

ill) la\

Humanum, is truly a - ~ __5sill

wm* tiffi^im/ question vexed ;

• g£2sw S*. >Z^^SKL^ - _ . At that epoch, however, one _^=ziser^^r^^g^^^

_ ./ .

prophet has seen us }r~£ sS?^r^'"^3i^w^^^B. Resemble the sketch

^Si^&lw^^^'^^ ^Sfi ^s For as Man undergoes ^^^®§^^^?fL^9fejw v u . Evolution ruthless,

^9^rfljr^^^\ f His skull willgrow**dome- " - ZL-- ~' • -t~ like, bald, terete " ; And his mouth will be jawless, gutnless, toothless-

No more will he drink or eat !

He will soak in a crystalline bath of pepsine, (No Robbbt will then have survived, to wait,)

And he JU hop on his hands as his food he steps in- & quasi-cherubic gait !

No longer the land or Ihe sea he'll furrow ; The world will be withered, ice-cold, dead

As the chill of Eternitv grows, he '11 burrow Far down underground instead.

If the Pall Mall Gazette has thus been giving A forecast correct of this change immense,

Our stars we may thank, then, tnat toe shan't be living A million years from henoe !

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

government scholarship to attend the Normal School of Science in South

Kensington (later absorbed into the University of London). Though Wells left South Kensington in 1887 without earning his degree, he was greatly inspired by his biology teacher, famed physiologist Thomas Huxley. Wells absorbed Huxley's pessimistic take on late- Victorian evolutionary theory, particularly his emphasis on the inherent brutality of natural selection.

Huxley's pessimism surfaces in Wells's dystopian scientific romances, which imaginatively probe the consequences of evolutionary theory run amok.3 Beginning with the eponymous mad-scientist villain of The Island

of Dr. Moreau (1896) and continuing with alien invasion narratives like The War of the Worlds (1897-98) and The First Men in the Moon (1901), Wells depicts brains becoming steadily larger and more powerful as bodies

grow smaller and more useless, emotions increasingly muted, and con- science all but silenced. Wells's nightmarish vision of the massively over- evolved brain unites these three works, as the ruthlessly intellectual biolo-

gist Moreau morphs into the amoral, top-heavy Martians and lunar inhabi- tants.

Wells's malevolent mad scientists and extraterrestrials owe an intellec- tual debt not only to Huxley, but also to discussions of genius and insanity in late- Victorian issues of Mind (1876-present).4 The now-familiar trope of the mad scientist in fact traces its roots to the clinical association between

genius and insanity that developed in the mid-nineteenth century. Authors like Scottish journalist and materialist philosopher John Ferguson Nisbet, English eugenicist Francis Galton, and Austrian Jewish physician Max Nor- dau - all of whose works were reviewed in Mind - argued that mankind had evolved larger brains at the expense of muscular strength, reproductive capacity, and moral sensibility.5 Wells drew upon these arguments in his fiction and even contributed his own article to Mind, a philosophical re- flection on science entitled "Scepticism of the Instrument" (1904).

In its unique role as "the first English journal devoted to Psychology and Philosophy." Mind was an ideal venue for an inherently interdisciplin-

3 See Roslynn Haynes, "Wells's Debt to Huxley and the Myth of Dr. Moreau," Cahiers Victoriens et Edouardiens 13 (1981): 31-41. 4 Mind articles addressing genius and intellectual over-specialization include James Sully, "Versatility," Mind 7.27 (1882): 366-80; Francis Galton, "Discontinuity in Evolution," Mind 3.11 (1894): 362-72; and Alexander Bain, "Education as a Science," Mind 2.5 (1877): 1-21. 5 Review of The Insanity of Genius and the General Inequality of Human Faculty y Physio- logically Considered, by John Ferguson Nisbet, Mind 16.64 (1891): 540-42; Review of

Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development, by Francis Galton, Mind 8.31 (1883): 453; Review of Degeneration by Max Nordau, Mind 4.16 (1895): 545-46.

319

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

ary subject like the clinical study of genius.6 The journal's first editor, George Croom Robertson, was particularly concerned that articles in Mind rise "above the narrowing influences of modern specialism."7 This disci-

plinary breadth attracted contributors from all fields, including fiction writ- ers and literary critics like George Henry Lewes, Grant Allen, Andrew

Lang, and, of course, H.G. Wells. During the same period, literary works

probed ideas discussed in Mind, such as the nature of the soul, the possibil- ity of free will, and the ramifications of biological determinism. In the four decades following its auspicious start, Mind provided a venue where scien- tists, philosophers and literary authors could find intellectual common ground.

In this essay, the early fiction of H.G. Wells will serve as a case study of cross-fertilization between literature and scientific ideas discussed in Mind. The goals of this exploration are threefold: to gain a better under-

standing of the journal's history and influence; to investigate why Victori- ans associated genius with insanity; and to illuminate the shared intellectual

genealogy linking Wells's mad scientists and extraterrestrials.

I. GENIUS AND INSANITY

Because Nisbet's work synthesized earlier scholarship about genius and in-

sanity and proved especially influential to Wells, his 1891 volume The In-

sanity of Genius will serve as an excellent ideological (if not chronological) point of departure. In this volume, Nisbet declared: "genius, insanity, idi-

ocy, scrofula, rickets, gout, consumption, and the other members of the

neuropathic family of disorders" reveal "want of equilibrium in the nervous

system."8 According to Nisbet's reviewer in Mind, the author assumed that

"superiority and inferiority to the average are to be classed together as devi- ations from the normal" and that abnormality was necessarily pathologi- cal.9 Nisbet also argued that genius was co-morbid with various types of mental illness. More importantly, he defined genius itself as a kind of hered-

itary, degenerate brain condition symptomatic of "nerve disorder" which

6 George Croom Robertson, "Prefatory Words," Mind 1.1 (1876): 1-6, 1. 7 Robertson, "Prefatory Words," 4. 8 John Ferguson Nisbet, The Insanity of Genius and the General Inequality of Human

Faculty t Physiologically Considered, 4th ed. (Folcroft, Penn.: Folcroft Library Editions, 1973), 57. 9 Review of The Insanity of Genius, 541.

320

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

"runs in the blood."10 Nisbet undermined his compelling argument, how-

ever, by failing to provide a consistent psychological definition of genius. Like many other writers linking genius with insanity, Nisbet naively as- sumed that accomplishment bespoke intellectual aptitude, thus confusing success and fame with innate ability.

Despite this flaw, The Insanity of Genius was reprinted three times before 1900, perhaps because it articulated a timely and popular idea. Late- nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century British and Continental authors

produced hundreds of monographs on genius and insanity.11 The cumula- tive result was the widespread belief in a "scientific" relationship between

genius and mental illness during the late- Victorian era - even though the volumes making this claim were surprisingly unscientific, relying primarily upon anecdotal evidence rather than experimental or statistical data.12

Of course, Victorians were not the first to correlate genius and mental illness. This association began with classical authors, notably Plato, Seneca, and Aristotle, who famously declared that "no great genius has ever been without some touch of madness."13 "Genius" is in fact a Latin word derived from the Greek ginestbai ("to be born or created"). In classical pagan tradi-

tion, a "genius" referred to the guiding or tutelary spirit allotted to each

person at birth. From the Renaissance until the eighteenth century, English authors frequently invoked the older meaning of genius as tutelary spirit. This usage gradually gave way in the nineteenth century to the now familiar definition of genius as superlative intellectual ability (or a person possessing such ability).14

Significantly, the period when this linguistic transition occurred - the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries - witnessed the birth of sev- eral modern myths about genius. Whereas Enlightenment authors described the genius as directly inspired by God, Romantics developed a secularized version of this view that emphasized the artist or poet himself as a godlike figure. Politically, the Romantic genius was a rebellious figure who chal-

10 Nisbet, The Insanity of Genius, 325. 11 For a comprehensive bibliography of literature on genius and insanity, see Wilhelm

Lange-Eichbaum, Genie, Irrsinn und Ruhm, 7th ed. (12 vols.; Munich: Ernst Reinhardt Verlag, 1986), 1: 237-53. 12 Nancy Andreasen, The Creative Brain: The Science of Genius (New York: Penguin, 2006), 84-85. 13 Seneca attributes this remark to Aristotle in "De Tranquillitate Animi" (On Tranquility of Mind), in Moral Essays 17:10. 14 This etymology was compiled from two sources: "Genius" in the Oxford English Dic- tionary, 2nd ed. (1989); and Andreasen, The Creative Brain, 6-7.

321

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

lenged social hierarchies by suggesting that innate creative powers trump class status.

Romantics embraced the classical notion of the creative process as an

inherently irrational furor poeticus: an "aesthetic response [that] seemed to involve a spell, a rapture, a delirium, a momentary madness."15 The creative

process was also inherently solitary and necessitated a certain degree of

suffering for one's art. In England, the Romantic figure of the godlike yet tormented genius was memorably embodied by Lord Byron's self-loathing protagonists, the eponymous hero of Percy Shelley's "Prometheus Un-

bound," and Mary Shelley's Victor Frankenstein. Whereas the Romantics saw genius as a mystical phenomenon beyond

the reach of scientific investigation, Victorians brought scientific tools and

techniques to bear on superlative ability. Rather than glorifying creative

powers, Victorians pathologized genius and upheld the mediocre man as an

evolutionary ideal. Michel Foucault has discussed how the impetus towards medical and social conformity reasserted itself as the Romantic cult of indi-

viduality waned; nineteenth-century scientists "embrace [d] a knowledge of

healthy man . . . and a definition of the model man."16 This emphasis on

normalcy derived partly from Belgian mathematician Adolphe Quetelet's influential statistical concept of the "homme moyen" or average man. Que- telet's essay A Treatise on Man and the Development of his Faculties (1835) presented his so-called "average man" as the central value around which measurements of a human trait are grouped according to the normal distri- bution.17 According to this model, all aberrations from the norm could be seen as pathological, including extreme intelligence.

Victorians studying genius and insanity eagerly embraced Quetelet's ideas. Francis Galton, a prodigy who could read, write, and conjugate Latin verbs by age four, employed Quetelet's law of deviation from an average throughout his landmark study Hereditary Genius (1869).18 One of the few

scientifically rigorous studies of genius before 1900, Galton's Hereditary Genius incorporated intelligence distribution charts that were clearly fore- runners of the I.Q. bell-curve.19 Less mathematically-inclined authors like

15 Frederick Burwick, Poetic Madness and the Romantic Imagination (University Park, Penn.: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996), 12. 16 Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Random House, 1994), 34. 17 "Quetelet, Adolphe," in Encyclopaedia Britannica (March 30, 2007) http://www .search.eb.com/eb/article-9062246. 18 Andreasen, The Creative Brain, 82. 19 Daniel Nettle, Strong Imagination: Madness, Creativity and Human Nature (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 37.

322

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

Nisbet likewise absorbed Quetelet's view of normalcy as an index of health. Nisbet claimed, "It is inevitable that all departures from the mean, in the human species, including those which constitute genius, should be un- sound."20 Such apparently democratic sentiments spelled trouble for Victo- rian geniuses, who suddenly found themselves classed among lunatics and imbeciles at the fringes of statistical charts.

Whereas the Romantics idealized poetic genius, Victorians increasingly focused on scientific prodigies. Cesare Lombroso, professor of psychiatry and forensic medicine at Turin and author of Man of Genius (1864; English translation 1891), defied the common view that "mathematicians are ex-

empt from psychical derangements" by including mathematical greats like Isaac Newton and Blaise Pascal in his list of mad geniuses.21 Galton, mean-

while, devoted an entire book to scientific precocity, English Men of Sci- ence: Their Nature and Nurture (1875).

Scientific genius was a timely theme well-suited for imaginative litera- ture. Significantly, the rise of the mad scientist as fictional trope coincided with the growth of scientific professions. Roslynn Haynes has described how pejorative stereotypes about scientists intensified following the Indus- trial Revolution and the biological revolutions of the Victorian era, result-

ing in a plethora of intriguing literary figures. "The alchemist" is a Faustian character who "reappears at critical times" in the history of science. He

obsessively pursues arcane intellectual goals redolent of ideological evil (re- cently, Haynes notes, such characters are usually biologists). A second ste-

reotype, the "unfeeling scientist" who has "suppressed all human affections in the cause of science," is clearly a legacy of Shelley's Victor Franken- stein.22 Late-Victorian mad scientists were often composites of these two

stereotypes. Moreau is a key example, as are the eponymous protagonist of Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), Dr. Raymond of Arthur Machen's The Great God Pan (1894) and the sinis- ter vivisector Dr. Nathan Benjulia in Wilkie Collins's Heart and Science

(1883). The first draft of Moreau, with its deleted references to Franken- stein and its structural resemblance to Jekyll and Hyde, suggests that Wells

self-consciously situated his novella within this emergent tradition of mad scientist fiction.23

20 Nisbet, The Insanity of Genius, xxii-xxiii. 21 Cesare Lombroso, The Man of Genius (New York: Garland Publishing, 1984), 73. 22 Roslynn D. Haynes, From Faust to Strangelove: Representations of the Scientist in Western Literature (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), 3. 23 Robert Philmus, "Introducing Moreau," in H. G. Wells, The Island of Dr. Moreau: A Variorum Text, ed. Philmus (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), xi-xlviii, xx-xxi.

323

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

While it is understandable that literary authors might capitalize on lay fears surrounding science and scientists, this does not explain what Victo- rian scientists stood to gain by doing so. Why would bright men like Galton or Lombroso risk implicating themselves by classifying genius (especially scientific genius) alongside madness? Tellingly, biologists and psychologists seem suspiciously under-represented in Victorian writing on mad geniuses, although crazed biologists abounded in late-Victorian fiction. Psychologists and physicians like Lombroso and Sully focused on insanity among literary authors, musicians, painters, and the occasional mathematician, rarely scrutinizing geniuses from their own disciplines. For instance, Sully (who penned an astonishing 22 articles for Mind) included only one biologist, Georges Cuvier, in his influential 1885 article "Genius and Insanity."24 Gal-

ton, whose own talents were so pronounced, took a kindlier view of scien- tific genius than the other writers represented. Alternatively, some scientists

may have actually coveted the cachet of mystery and power surrounding the Romantic genius, even once this aura became tarnished through associ- ation with evolutionary undesirables.

The ways in which scientists discussed genius changed significantly over the course of the nineteenth century, due to shifting scientific para- digms as much as public sentiment. Early-nineteenth-century authors re- lated genius to monomania, a diagnosis defined by French psychiatrist Jean Esquirol around 1810 that remained popular for several decades. Accord-

ing to Jan Goldstein, monomania was an "idee fixe, a single pathological preoccupation in an otherwise sound mind" that could prompt "overween-

ing ambition."25 By contrast, late-nineteenth-century authors like Nisbet, Galton, Lombroso, and Max Nordau connected genius with evolutionary theory and medical conditions like hysteria.

French psychiatrist Jacques Moreau's Morbid Psychology (1859) be- came the most influential early treatise on genius and insanity. Moreau, who is today best known for his experiments with marijuana, almost cer-

tainly served as the model for Wells's villainous biologist of the same name. Moreau argued in Morbid Psychology that "genius was essentially a 'ne- vrose' or nervous affliction similar to idiocy," based on a review of around 180 alleged geniuses.26 He sought to replace the exalted Romantic view

24 James Sully, "Genius and Insanity," The Nineteenth Century 27 (1885): 948-69, 957. 25 Jan Goldstein, Console and Classify: The French Psychiatric Profession in the Nine- teenth Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 155-56, 159. 26 George Becker, The Mad Genius Controversy: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance

(Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1978), 29.

324

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

of genius with a vision of great thinkers as diseased victims of biological determinism. Moreau accordingly suggested that geniuses create due to in-

stinct or compulsion rather than divine inspiration:

Contrary to what one observes in men of average intelligence, the

work of superior men is entirely spontaneous, and in some ways as involuntary as possible. It is the result of impulse and an instinc-

tive need, and of an intellectual appetite that makes itself felt, no

one knows why ... it has been said, and with reason, that no one

is less free in his work, to choose the time of his work in particular, than the men of whom we speak.27

Moreau's comments stigmatized the genius as an unfortunate, if occasion-

ally useful, biological anomaly. He further suggested that "the idiot, the

hysteric, the epileptic, the madman, as well as the genius, are . . . branches

growing from the same tree" (Figure 2, p. 326).28 Moreau greatly influenced later Continental literature on genius, par-

ticularly Lombroso's Man of Genius and Max Nordau's Degeneration (1892, English translation 1895). Though these works were largely deriva-

tive, both have received far more critical attention than Moreau's more

original Morbid Psychology. This neglect may stem from the relative scar-

city of the latter volume, which was never translated or reissued, or from

the sensational tone adopted by Moreau's successors. "The man of genius is a monster," claimed Lombroso, "but even monsters follow well-defined

. . . laws."29 Lombroso contended that "Genius is a true degenerative psy- chosis belonging to the group of moral insanity."30 Moral insanity was a

common nineteenth-century term for "madness consisting in morbid per-

27 "Contrairement a ce qu l'on observe chez les hommes d'intelligence moyenne, le travail chez les hommes superieurs, est tout spontane, et en quelque sorte, aussi peu volontaire

que possible. II est le resultat de Pentrainement, d'un besoin instinctif, d'une sorte d'ap-

petit de Pintellect, que se fait sentir, on ne sait pourquoi ... on dit avec raison que personne n'etait moins libre dans ses travaux, de choisir son temps, son heure de travailler

que les hommes dont nous parlons." Jacques Moreau, La psychologie morbide dans ses

rapports avec la philosophie de Vhistoire ou de Vinfluence des neuropathies sur le dynami- sme intellectuel (Paris: Librairie Victor Masson, 1859), 494-95. 28 George Frederick Drinka, The Birth of Neurosis: Myth, Malady, and the Victorians

(New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984), 54. 29 Lombroso, The Man of Genius, viii. 30 Thomas Tyler, Review of The Man of Genius, by Cesare Lombroso, The Academy (March 20, 1892), 303.

325

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

FIGURE 2: Jacques Moreau's "Tree of Nervosity," in La psychologie morbide (Paris: Librairie Victor Masson, 1859).

326

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

version of the natural feelings, affections, . . . and natural impulses," in

which the sufferer remains rational and experiences no hallucinations.31

Lombroso solidified the identification between genius and criminality that became a popular theme among late- Victorian scientists and novelists.

As with all criminal types he analyzed, Lombroso identified physical stig- mata of genius, especially "elevation of the forehead, notable development of the nose and of the head, [and] great vivacity of the eyes."32 Lombrosian

stigmata quickly became standard features of mad scientist literature, be-

ginning with Stevenson's Hyde, who bears on his body "an imprint of de-

formity and decay," and continuing with Wells's large-headed, large-eyed mad scientists and extraterrestrials.33

Nordau was Lombroso's intellectual disciple who took aim at artistic

and poetic geniuses, claiming that they manifested the same degenerate mental and somatic traits as hysterics, criminals, prostitutes, anarchists, and other undesirables. Nordau stridently criticized symbolist and decadent

writers like Joris-Karl Huysmans and Henrik Ibsen, not to mention avant-

garde musicians like Richard Wagner. In one particularly hysterical pas-

sage, he asked readers to imagine degenerate protagonists of Ibsen's and

Huysmans' works "in competition with men who rise early, and are not

weary before sunset, who have clear heads, solid stomachs, and hard mus-

cles." Nordau concluded that "degenerates must succumb," damning the

artistic genius to speedy evolutionary extinction.34 Nordau evidently took

Quetelet's idealization of the "average man" to an imaginative extreme,

envisioning the ordinary Austrian peasant laborer triumphing over the ef-

fete, artistic intellectual.

The first important English writer on genius was Galton, Charles Dar-

win's cousin and a six-time contributor to Mind. Galton's book Hereditary Genius and his Mind article "Discontinuity in Evolution" (1894) advanced

the then-controversial notion that genius could be passed down to off-

spring. Though Galton saw genius as beneficial to humanity, he still wor-

ried that "genius ... is perilously near to voices heard by the insane, to

31 James Cowles Prichard, "Forms of Insanity," in Embodied Selves: An Anthology of Psychological Texts: 1830-1890, ed. Jenny Bourne Taylor and Sally Shuttleworth (Ox- ford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 252. 32 Lombroso, The Man of Genius, 14-15. 33 Robert Louis Stevenson, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, ed. Richard Dury, 2nd ed. (Genoa: ECIG, 2005), 167. 34 Max Nordau, Degeneration, trans. George L. Mosse (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 541.

327

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

their delirious tendencies, or to their monomanias."35 Like Nordau and

Lombroso, Galton thought extraordinary men were relatively unlikely to

reproduce, blaming the "shy, odd manners, often met with in young per- sons of genius."36

For the above-mentioned writers, the evolutionary rationale for associ-

ating genius with madness, degeneracy and infertility derived primarily from French zoologist Jean Baptiste Lamarck rather than Charles Darwin. Daniel Pick emphasizes that certain aspects of Lamarckian thought re- mained scientifically current until the early twentieth century. Despite the crucial non-Lamarckian concept of natural selection, Darwin himself and

many of his followers maintained some Lamarckian assumptions, including (to a limited extent) the heritability of acquired characteristics.37 In the

1890s, neo-Lamarckian evolutionary theories peaked in popularity as some intellectuals became disenchanted with the materialist implications of Dar- winian natural selection, which seemed to permit no human control of evo-

lutionary processes. Neo-Lamarckians hoped to positively influence the future of humanity by acquiring desirable traits and passing them on to their offspring, allowing for more rapid and volitionally-directed evolution-

ary progress than Darwinian natural selection.38 Lamarck and his followers suggested that "hypertrophy" or excessive

growth of any given body part - in this case, the brain - was always com-

pensated by atrophy of other body parts. According to Lamarck's first law, which he expounded in Zoological Philosophy (1809), "use of any organ gradually strengthens, develops and enlarges that organ . . . while the per- manent disuse of any organ imperceptibly weakens and deteriorates it, and

progressively diminishes its functional capacity, until it finally disap- pears."39 According to Lamarck's second law, meanwhile, changes brought about by use or disuse of any organs would be inherited by the next genera- tion. Following this logic, the genius who overused his brain could expect his cerebrum to expand while the rest of his body wasted away.

Writers linking genius and insanity reasoned according to these Lamar-

35 Francis Galton, Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry into its Laws and Consequences (Lon- don: Watts and Co., 1950), x. 36 Galton, Hereditary Genius, 318. 37 Daniel Pick, Faces of Degeneration: A European Disorder, c. 1848-1918 (New York:

Cambridge University Press, 1989), 100-101. 38 Peter Bowler, The Eclipse of Darwinism: Anti-Darwinian Evolution Theories in the Decades Around 1900 (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), 70-75. 39 Jean Baptiste Lamarck, Zoological Philosophy: An Exposition with Regard to the Nat- ural History of Animals (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 113.

328

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

ckian principles. For instance, Lombroso suggested that mankind evolved

large brains by eliminating unnecessary organs present in lower animals:

"Reptiles have more ribs than we have; quadrupeds and apes possess more muscles than we do, and an entire organ, the tail, which we lack. It has been in losing these advantages that we have gained our intellectual superi- ority."40 Sully and Lombroso predicted that such lopsided evolution would

ultimately result in geniuses who were "puny and ill-formed men" exhibit-

ing "excessive asymmetry of face and head . . . smallness or disproportion of the body, left-handedness, [and] stammering" among other marks of de-

generacy.41 Lamarckian principles even surfaced in Victorian educational

philosophy, which promoted mental balance by avoiding intellectual over-

specialization. Alexander Bain, the founder of Mind, recommended exercis-

ing the brain to develop "the plastic power of the mind," but cautioned that overusing any particular intellectual faculty could compromise "the whole man."42

Neo-Lamarckian thinkers further suggested that hypertrophy of the intellect led to atrophy of the emotions and consequent insanity. Lombroso stated: "Just as giants pay a heavy ransom for their stature in sterility and relative muscular and mental weakness, the giants of thought expiate their intellectual force in degeneration and psychoses."43 One possible conclu- sion of rapid Lamarckian brain evolution, then, was a species of morally insane beings boasting enormous cerebrums and miniscule bodies, a night- marish vision dramatized in Wells's fiction.

Previous scholarship suggests that Wells abandoned Lamarckism around 1895 in favor of German biologist August Weismann's neo-Dar-

winian, proto-genetic germ plasm theory of inheritance.44 Weismann ar-

gued in 1886 that hereditary information is passed down to offspring via so-called "germ cells" that are distinct from other bodily cells. Moreover,

by cutting off the tails of several generations of mice and observing that their offspring still had tails, Weismann apparently demonstrated that ac-

quired traits are not heritable.45 In early evolutionary writings such as "Inci-

40 Lombroso, The Man of Genius, v. 41 Sully, "Genius and Insanity," 966; Lombroso, The Man of Genius, 6. 42 Bain, "Education as a Science,

' 7, 5.

43 Lombroso, The Man of Genius, vi. 44 See Philmus, "Introducing Moreau," xviii, xl; John Glendening,

" 'Green Confusion': Evolution and Entanglement in H.G. Wells's Island of Dr. Moreau," Victorian Literature and Culture 30.2 (2002): 571-97, 579. 45 "Weismann, August" in Encyclopaedia Britannica (April 7, 2007) http^/www.search .eb.com/eb/article-9076462.

329

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

dental Thoughts on a Bald Head" (1895), Wells apparently agreed with Weismann: "Professor Weissman [sic] has at least convinced scientific peo-

ple . . . that the characters acquired by a parent are rarely, if ever, transmit- ted to its offspring."46 But even if one views this indirect statement as indicative of Wells's own beliefs, I suspect that Wells abandoned Lamarck- ism slowly and reluctantly, rather than all at once. In "Human Evolution, an Artificial Process" (1896) for instance, Wells struck an uneasy compro- mise between Lamarckism and Weismannism. In this article, Wells ac-

knowledged "Professor Weismann's destructive criticisms of the evidence for the inheritance of acquired characters" but suggested that "artificial"

evolution, in the form of education and cultural traditions, could ensure human progress.47

Wells's fictional output between 1895 and 1901 likewise bears witness to his continued interest in Lamarckian evolutionary thought. In The War

of the Worlds and First Men in the Moon, massive alien cerebrums evolve at the expense of dwindling, underused bodies, following Lamarck's first law. Wells, however, broke with progressivist neo-Lamarckian thought that

emphasized purposeful acquisition of new characteristics as "an intelli-

gence-driven process."48 Instead, Wells presented a disturbing vision of the

dystopian possibilities of Lamarckian brain evolution run amok, as did most late-Victorian writers discussing the pathology of genius.

Lamarckism likewise surfaced in Victorian discussions about female

geniuses. Nineteenth-century scientists agreed that "genius of the highest order is practically limited to the male sex," only occasionally making ex-

ceptions for female novelists like Charlotte Bronte, George Eliot, and

George Sand.49 Henry Maudsley, a prominent English psychologist and

four-time contributor to Mind, famously contended that studious women

developed their intelligence at the expense of their reproductive organs, thereby threatening the future of the race.50 This argument, like discourses about overly cerebral male geniuses, stemmed from the Lamarckian idea

that overuse of any organ compromised other bodily functions.

46 H. G. Wells, "Incidental Thoughts on a Bald Head," Pall Mall Gazette (1895), re- printed in Wells, Certain Personal Matters (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1901), 106. 47 H. G. Wells, "Human Evolution, an Artificial Process," in Robert Philmus, ed., H.G. Wells: Early Writings in Science and Science Fiction (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975), 211-19, 211. 48 Glendening, "Green Confusion," 579. 49 Review of Difference in the Nervous Organisation of Man and Woman, by Harry Campbell, Mind 16.63 (1891): 542. 50 Maudsley, "Sex in Mind and Education," Fortnightly Review 15 (1874): 469-71.

330

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

The forgoing discussion suggests how racial, national and gender ste-

reotypes undergirded theories about genius and leant them a measure of cultural authority. While the genius described by late Victorians was defin-

itively male, his masculinity was undermined by the suggestion of hysterical effeminacy and his refusal of heterosexual procreation. Moreover, his social and political loyalties came under scrutiny. Lombroso declared, "in men of

genius, the love of family and country is either absent or less strong than in other men."51 These cultural stereotypes, buttressed by scientific authority, crystallized in late-nineteenth-century fictional portrayals of mad scientists.

Wells wrote his early scientific romances during the decade when inter- est in mad geniuses peaked in the popular press. His fictions faithfully ad- here to the neo-Lamarckian evolutionary theory expressed in these discourses, but add a fascinating new twist by morphing the mad scientists of The Time Machine and The Island of Dr. Moreau into the top-heavy extraterrestrials of The War of the Worlds and The First Men in the Moon. The transition is seamless, striking, and utterly novel, reminding us just how threatening superior intelligence seemed even at a time when it was

increasingly necessary to professional success and scientific progress.

II. MAD SCIENTISTS AND GIANT BRAINS FROM OUTER SPACE

One might reasonably inquire which late-Victorian writings on genius in-

spired Wells's fiction. Though he read Galton and Nordau, Wells seems to have been especially responsive to John Ferguson Nisbet, whom he met in the late 1890s.52 In 1899, Wells reviewed Nisbet's volume The Human Ma- chine for The Academy (1869-1916). In his review, Wells lamented that The Insanity of Genius received insufficient recognition:

Nisbet's former work, on The Insanity of Genius, temperately and

soundly argued, was comparatively speaking a failure. Dr. Nor- dau's bawling version of the same thesis, coarsely seasoned with

gross personalities, sauced with a dressing of sexual incontinence . . . attained a vast success.53

51 Tyler, Review of The Man of Genius, 304. 52 H. G. Wells to Elizabeth Healey, February 7, 1901, The Correspondence ofH.G. Wells, ed. David Smith (London: Pickering and Chatto, 1998), 1: 379. 53 H. G. Wells, Review of The Human Machine, by John Ferguson Nisbet, The Academy (May 6, 1899), 503.

331

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

Critical neglect of Nisbet's relationship to Wells has occluded important links between The Insanity of Genius and The Island of Dr. Moreau. Since Nisbet quoted extensively from Jacques Moreau's Morbid Psychology, it seems that this real-life Dr. Moreau was very likely the prototype for Wells's fictional namesake.54

Wells's fictional Moreau owes as much to Victor Frankenstein, how- ever, as he does to the theories of his non-fictional namesake. As narrator Edward Prendick explains, Moreau is a "prominent and masterful physiol- ogist" forced to leave England due to public outcry over his "wantonly cruel" experiments involving animal vivisection.55 Moreau settles on re- mote Noble's Island near the Galapagos and there grafts the bodies of vari- ous kinds of animals together in order to create "Beast People" with near- human intelligence. These monsters speak broken English and worship their creator. Like Frankenstein, Moreau is unmarried, single-mindedly de- voted to research, and shamefully neglectful of his creations, one of whom (a female puma) ultimately kills him.56

But while Frankenstein's monster is composed entirely of human re- mains, Moreau's patchwork creations grotesquely literalize the opinion Wells articulated in Mind, that "biological species . . . pass into one another

by insensible gradations."57 Moreau's island laboratory is a space where

"every species is vague [and] cloudy at the edges," and where the line be- tween human and animal appears distressingly unclear.58 Indeed, The Is- land of Dr. Moreau stretches the more disturbing implications of

evolutionary thought to their very limits. The Beast People, who revert to their animal state after Moreau's death, embody the frightening possibility of human "retrogressive metamorphosis" described by Huxley, who warned that organisms could "progress from a condition of relative com-

plexity to one of relative uniformity."59 Meanwhile Moreau, with his "fine

54 A few previous critics compare the fictional and historical Moreaus, but none mention Wells's familiarity with Morbid Psychology. See Philmus, "Introducing Moreau," xviii, xli-xliii; Elaine Showalter, Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the fin de siecle (New York: Penguin, 1990), 178-79; Kelly Hurley, The Gothic Body: Sexuality, Materialism, and Degeneration at the fin de siecle (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 109. 55 H. G. Wells, The Island of Dr. Moreau: A Variorum Text, ed. Robert Philmus (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), 21-22. 56 On Moreau's Frankensteinian qualities, see also Chris Baldick, In Frankenstein 's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth -Century Writing (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 153-56. 57 H. G. Wells, "Scepticism of the Instrument," Mind 13.51 (1904): 379-93, 384. 58 Wells, "Scepticism of the Instrument," 386. 59 Thomas Huxley, Evolution and Ethics (New York: Prometheus Books, 2004), 7.

332

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

forehead" bespeaking superior intellectual gifts, seemingly represents the

pinnacle of human evolution.60

However, Moreau has evolved too far in the opposite direction, since his massive intellect compromises his emotional sensitivity. His monomani- acal quest "to find out the extreme limit of plasticity in a living shape" outweighs all considerations of suffering it might cause. When Prendick asks how the doctor can bear the screams of his vivisected animals, Moreau

explains, "The thing before you is no longer an animal, a fellow-creature, but a problem. Sympathetic pain - all I know of it I remember as a thing I used to suffer from years ago."61 Moreau's appalling indifference suggests the "complete absence of moral sense and of sympathy" that Lombroso associated with moral insanity.62

Early drafts of The Island of Dr. Moreau indicate that the mad doctor's

amorality and single-minded devotion to experimentation result from men- tal illness. In one rough draft, Moreau's assistant, Montgomery, excuses his

employer's scientific preoccupation on the grounds of mental instability: "This research is only a sane kind of mania. It's irresistible. He's driven to make these things, can't help it any more than an avalanche . . . can help smashing a tourist."63 This passage exemplifies the late- Victorian biological determinist view of mental illness as hereditary and therefore untreatable, a position championed by Jacques Moreau and Henry Maudsley. Seen from the grim perspective of evolutionary neurology, then, Dr. Moreau's overde-

veloped rationality is the monstrous presence on the island, not the grafted hybrids he creates.

Wells's scientific romances about extraterrestrials, The War of the Worlds and The First Men in the Moon, literally alienate the concept of the mad scientist. The Martians and lunar beings usurp this stereotyped role with their hypertrophied intellects, atrophied emotional sympathies, and unconcealed impulse towards world domination. The language of alien- ation permeating late-Victorian discourse about genius set the stage for this

characterological morphing. Sully, for example, declared that "the peculiar leanings and aspirations" of the man of genius "stamp him as an alien."64

The invading Martians of Wells's War of the Worlds, with their ad- vanced civilization and enormous brains, present a dystopian vision of what

60 Wells, The Island of Dr. Moreau, 17. 61 Ibid., 48. 62 Lombroso, The Man of Genius, 57. 63 H. G. Wells, "Appendix 1: The First Moreau," in The Island of Dr. Moreau, 136. 64 Sully, "Genius and Insanity," 963.

333

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

might happen if all humans evolved into geniuses. One obvious conse-

quence of this development would be widespread moral insanity. The Mar-

tians' amorality is evident soon after they arrive on earth and mercilessly

slaughter the human welcoming party sent to greet them. They later eat the

desperate survivors who remain after they destroy London with terrifying heat rays and toxic gas. In a short time, the Martians overcome all military resistance and nearly take over the earth. These giant brains from outer

space epitomize the mad scientist trope, in which the conscienceless, cosmo-

politan scientist achieves world domination and wreaks havoc on human

subjects. While Moreau merely has a pronounced forehead, the Martian invad-

ers have developed their brains at the expense of all other body parts, ex-

cepting "bunches of delicate tentacles" serving roughly the same function

as human hands. Their physical forms are "heads - merely heads. Entrails

they had none."65 Wells parallels Martian evolution with the eventual prog- ress of human evolution, in which, as centuries pass,

Such organs as hair, external nose, teeth, ears and chin were no

longer essential parts of the human being . . . the tendency of natu-

ral selection would lie in the direction of their steady diminution

through the coming ages. The brain alone remained a cardinal ne-

cessity.66

The Martians, Wells writes, have already undergone such evolutionary de-

velopments on their own planet, foreshadowing man's fate:

Here in the Martians we have beyond dispute the actual accom-

plishment of such a suppression of the animal side of the organism

by the intelligence. To me it is quite credible that the Martians

may be descended from beings not unlike ourselves, by a gradual

development of brain ... at the expense of the rest of the body. Without the body the brain would, of course, become a mere

selfish intelligence, without any of the emotional substratum of the

human being.67

65 H. G. Wells, The War of the Worlds, ed. Patrick Parrinder (New York: Penguin, 2005), 125. 66 Ibid., 127. 67 Ibid., 127.

334

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

By becoming "practically mere brains," the Martians have reached a peril- ous level of intellectual abstraction, in stark contrast to the carnal reality of the human beings upon whom the invaders feed.68 Peter Kemp aptly sug- gests that in Wells's fiction "flesh is made to creep by reminders that it is

flesh, and, as such, edible."69 As human flesh is sacrificed to hungry giant brains, the evolutionary possibility of the body dwindling at the expense of the bulging cerebrum comes vividly to life.

Predictably, such cerebral overdevelopment has disadvantages. Follow-

ing neo-Lamarckian logic, the Martians' accelerated brain evolution weak- ens their fragile bodies. In War of the Worlds, Martian bodies hardly ever become visible, since they are encased in prosthetic devices that provide greater mobility, power, and destructive capacity. These prosthetic devices resemble "a great body of machinery on a tripod stand," a form which in

turn suggests the Martian's large heads and elongated limbs.70 Within these

tripod-like machines, the Martians lay waste to England with fearful weap- ons. Outside of these prostheses, however, the Martians appear "crippled" and move in a "clumsy" fashion, hampered by the earth's strong gravita- tional pull.71 The Martians have clearly "dispense[d] with muscular exer-

tion" in favor of "mechanical intelligence."72 This trade-off leaves them

consummately vulnerable to disease, since they ultimately succumb, in a neat final paradox, to earthly bacteria to which humans have gradually evolved a resistance.

In The First Men in the Moon, Wells creates a darkly comic satire of intellectual over-specialization using the familiar figure of the top-heavy extraterrestrial. In this novella, an eccentric chemist named Cavor becomes the alien visitor from another planet after he invents a gravity-defying sub- stance and journeys to the moon. There, he unexpectedly discovers a com-

plex lunar society of insect-like beings called Selenites. Cavor radios

messages to Earth conveying his unabashed admiration for Selenite culture, but his final broken transmission implies that the Selenites kill him. As in

The War of the Worlds, the novella consistently parallels human scientific

rationality and amorality with that of the aliens. Cavor is an unmarried and

obsessive researcher in the tradition of Frankenstein and Moreau, although he is bumbling rather than malevolent. By juxtaposing a human mad scien-

68 Ibid., 129. 69 Peter Kemp, H.G. Wells and the Culminating Ape (New York: St. Martin's, 1982), 34. 70 Wells, The War of the Worlds, 46. 71 Ibid., 22. 72 Ibid., 33.

335

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

tist and extraterrestrials with similar mental processes, Wells likens mon-

strous alien life forms to the moral monstrosities of which unscrupulous geniuses are capable.

The upper-class Selenites boast hypertrophied brains like the Martians, but have also developed intellectual specialization. No Selenite is able to

function outside of his own particular discipline. A Selenite mathematician, for instance, is trained from birth to disregard all other pursuits:

His brain grows, or at least the mathematical faculties of his brain

grow, and the rest of him only so much as is necessary to sustain this essential part of him. At last, save for rest and food, his one

delight lies in the exercise and display of his faculty ... his brain

grows continually larger, at least so far as the portions engaging in

mathematics are concerned; they bulge ever larger and seem to suck the life and vigor from the rest of his frame. His limbs shrivel, his heart and digestive organs diminish, his insect face is hidden

under its bulging contours.73

The Selenite mathematician's enormous head has manifestly evolved at the

expense of his other body parts, as per Lamarck's first law. Psychologically speaking, this extra-terrestrial resembles a monomaniac or even an idiot savant. Given Wells's great admiration of Jonathan Swift, it is no accident that the Selenite's behavior recalls the Laputans, who can only be roused from mathematical speculation when their servants rap them on the mouth and ears.

Like the Martians, the Selenites of the intellectual class appear physi- cally clumsy and frail. Instead of mechanical prostheses, however, the Sele-

nite intellectuals surround themselves with ushers and bearers to "replace the abortive physical powers of these hypertrophied minds." Cavor relates, "Some of the profounder scholars are altogether too great for locomotion, and are carried from place to place in a kind of sedan tub, wabbling [sic]

jellies of knowledge that enlist my respectful astonishment."74 The utter

dependency of the intellectual Selenites upon the lower classes ominously resembles the grotesquely symbiotic relationship of the Morlocks and Eloi in The Time Machine (1895).

The hypertrophied brain reaches its apex in the figure of the Selenite

73 H. G. Wells, The First Men in the Moon, ed. Patrick Parrinder (New York: Penguin, 2005), 181. 74 Ibid., 183.

336

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

ruler, the Grand Lunar, whom Cavor encounters towards the end of his

journey:

At first as I peered into the radiating blaze, this quintessential brain looked very much like a thin, featureless bladder with dim, undu-

lating ghosts of convolutions writhing visibly within . . . below I

distinguished the little dwarfed body and its insect- jointed limbs, shriveled and white ... It was great, it was pitiful.75

The Grand Lunar lacks a skull, which leaves his brain visible and intensely vulnerable, yet permits unlimited brain growth and evolution. His impres- sive convolutions, meanwhile, reflect the then-prevalent belief that more numerous brain convolutions signify greater intelligence.76 The lunar ruler's

cerebrum is so overgrown that he lacks a face, let alone a body of normal

proportions. In a strikingly obvious way, this "great" yet "pitiful" being demonstrates the impractical, even monstrous result of unchecked progres- sive brain evolution according to the Lamarckian model.

Despite Wells's understanding of the alleged dangers of accelerated brain development, he maintained a lively interest in the Utopian possibili- ties of mental evolution. Wells declared in Mind that "the Instrument of

Thought . . . may have undefined possibilities of evolution towards in-

creased range, and increased power."77 Much later in life, Wells envisioned

even broader possibilities for the mental future of humanity. In 1938, he

penned a Utopian scheme entitled World Brain in which he proposed that

"the scientists, technicians and artists, the specialists in all fields, are to

be employed in the compilation of a vast, and continually updated world

encyclopaedia which will embody the collective wisdom of the world's best

brains on every conceivable issue."78 Wells hoped that this world-encyclo-

pedia or world-brain would serve as a resource for governments all over the globe (a vision partially realized today with the creation of the world- wide web). Moreover, Wells subtitled his 1934 Experiment in Autobiogra-

phy "Discoveries and Conclusions of a Very Ordinary Brain, since 1866." In this eccentric volume, Wells announced that, "the grey matter of that

organized mass of phosphorized fat and connective tissue ... is, so to speak,

75 Ibid., 192. 76 See Lombroso, The Man of Genius, 12-13. 77 Wells, "Skepticism of the Instrument," 391. 78 Roslynn D. Haynes, H.G. Wells: Discoverer of the Future: The Influence of Science on His Thought (London: Macmillan Press, 1980), 110-111.

337

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF IDEAS APRIL 2009

the hero of this piece."79 The revolutionary move of making a brain, rather than a person, the hero of his personal journey reflects Wells's unrelenting scientific materialism and his firm belief that autobiography should be, per- haps more literally than we are used to thinking, "the story of the contacts of a mind and a world."80

III. CONCLUSION

While Wells's scientific romances have endured, inspiring countless literary imitations and Hollywood films, the unique blend of psychology and phi- losophy found in Mind was lamentably short-lived. The foundation of the British Journal of Psychology in 1904 provided an alternative venue for articles in scientific psychology, allowing Mind to focus increasingly on phi- losophy.81 Psychological articles still appeared in Mind until the end of G. E. Stout's editorship in 1920, but thereafter the journal turned towards mathematics and logic and away from biology. In 1974, Mind finally dropped its original subtitle ("A Quarterly Review of Psychology and Phi-

losophy"), signaling a departure from the intellectual diversity of early is- sues and a turn towards the over-specialization that Wells mocks in First Men in the Moon.82

While it is difficult to find a modern venue boasting the interdisciplin- arity of early issues of Mind, certain areas of inquiry have continuously attracted scholars from a wide variety of fields. One such topic is the study of genius and creativity in relation to madness. In the late-twentieth and

twenty-first centuries, both humanists and scientists have addressed this

subject.83 Their work appears in diverse venues, but all of it owes an intel- lectual debt to Wells's fiction and to conversations occurring in fin-de-siecle issues of Mind.

79 Wells, Experiment in Autobiography (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1934), 20. 80 Ibid., 12. 81 William R. Sorley, "Fifty Years of M/W," Mind 35.140 (1926): 409-418, 413. 82 D. W. Hamlyn, "A Hundred Years of M/W," Mind 85.337 (1976): 1-5, 2. 83 Recent scientific studies on the relationship between creativity and mental illness in- clude Arnold Ludwig, The Price of Greatness: Resolving the Creativity and Madness

Controversy (New York: The Guilford Press, 1995); Nancy Andreason, "Creativity and Mental Illness: Prevalence Rates in Writers and their First-Degree Relatives," American

Journal of Psychiatry 144 (1987): 1288-92; and Kay Redfield Jamison, "Mood Disorders and Patterns of Creativity in British Writers and Artists," Psychiatry 52 (1989): 125-34. In humanistic fields, recent works on this subject include Burwick, Poetic Madness; and Corinne Saunders and Jane Macnaughton, eds, Madness and Creativity in Literature and Culture (New York: Palgrave, 2005).

338

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stiles The Journal Mind in its Early Years, 1876-1920

In popular culture, Wells's mad geniuses and malevolent extraterrestri- als have proven even more influential than in academia. Mad scientists re- main stock figures in many literary and filmic genres, while the large- headed, big-eyed aliens envisioned by Wells in the 1890s saturate modern

popular media to an extent that Wells himself could scarcely have imagined. Steven Spielberg's blockbuster rendition of War of the Worlds (2005) is

only the most obvious of many examples; indeed, nearly every alien on film

during the last century resembles a giant cerebrum with a spindly body. This highly visible survival of late-Victorian mad genius theories suggests that unusually high intelligence seems no less threatening or alien today than at the end of the nineteenth century.

Washington State University.

339

This content downloaded from 165.134.156.20 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 19:01:37 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions