Lion Character

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Lion Character

THE “ARYUŚ” CHARACTER (Excerpt from the book <“Lion” Character in the Petroglyphs of Syuniq and Ancient World>)

The image of the lion is the most widespread animal image in the petroglyphs of Syunik

- after that of the goat - comprising around 17% of all the pictures. In many petroglyphs, the

single lion appears accompanied by one or more abstract signs (see: picture 1)

Picture 1. Lion images accompanied by abstract signs

According to our classification, the images presented in picture 1 are central to the

writing (single-centre writing). Here the image of the lion is central and the characteristics

of the central ideas expressed by the lion images are ideographed by the smaller abstract

signs.

Many petroglyphs also exist in which the lion is depicted on the goat “blackboard” (see

picture 2). If we recall that, based on the homonymy of the Armenian դիգ(dig)=“goat” and

դիք(diq)=“god”, the ideograph of the word diq=“god” is the image of a goat and we can

comprehend it as a determinative of the idea of god, then it is clear that the a lion on the goat

“blackboard” is the ideograph of a certain god’s name. Below we will see who that god is,

what name he bore, and what the name meant.

Picture 2. Lion images on the goat “blackboard”.

The traditional perceptions concerning the lion, which have reached down to the

present from ancient times, link the image of this animal to the sun, power, strength and

royal authority. Below we will attempt to substantiate that those perceptions come from the

times of the origin of petroglyph engraving and pictography as a consequence of the

1

ideography of words expressing homonymous and abstract meanings of the word

առյուծ(aryuś)=“lion”, using the objective image of the word lion. In order to clarify this

issue, we must first reveal how this animal’s appellative is written and what homonyms it

has.

For this reason, let’s begin with what is the most important for our problem: the

Armenian appellative of lion. The oldest classical Armenian forms of the appellative of the

animal are “arewś,” “ariwś,” “areawś,” and “aroyś”. Ignoring the final “-ś” sound, which is an

augmentative affix1 acquired relatively later, we have the “arew-, ariw-, areaw-, aroy-” forms

for the initial, root appellative of the animal. Taking into account the word-end w>g

transition (compare: arew>areg, kov>kogi, aru>arog, orog etc.) we can also add the “areg,

arig, arog” forms to this list.

In this way we have the accurate appellative of our objective image (lion). Therefore,

we can form the list of words homonymous with the above mentioned appellatives of lion,

the logographs of which depict the lion image.

arew (also ariw in dialects), areg=“sun, light-emitting daytime star”. From its most

ancient mythological depictions in the Near East to the present, the lion has been considered

the symbol of the sun. Present-day scholars try to explain this sun-lion link by the external

characteristics of the lion or some feature or other in its nature. Scholars have also proposed

such explanations for other animal images (the bull, eagle, boar, snake and so on), but such

an approach is subjective and unsubstantiated. In our examination of the images of the lion

and other animals, we will show that they are ideographs and that homonymous words

expressing non-objective, abstract meanings have been ideographed by means of the names

of those animals.

The homonymy of the Armenian appellatives for Sun=“arew/ariw, areg” and

lion=“arew-, ariw-”, comes to prove that the sun-lion link arose around the time of the dawn

of pictography, when they began to ideograph and vocalise the word “arew, areg” with the

image of the lion (for the w=g equivalency, compare arew>areg, aru>arog/orog, kov>kogi

etc.).

In pictographic scripts, other characters have also represented the ideographs of the

appellative of the Sun or the God embodying the Sun. Firstly, in order to avoid confusion, let

us briefly familiarise ourselves with the most widespread of these. In the pictography of the

ancient world, especially in the Egyptian hieroglyphic script, the sun was also

diagrammatically drawn in the form of a circle with a dot in the centre ( ). The origin of

this character is also from the period of the creation of the rock carvings of Syunik; it was

initially used in the sense of sun and was used as an ideograph in Armenia up to the middle

ages.

The Armenian word “aregakn” is compounded comprising the “areg/arew” and

akn=“eye” components. In the same way the character is comprised of two components:

the =“sun, sun’s disk,” and ●=“eye” characters; i.e., we can say that the =Sun character

has been created based on the structure of the Armenian word “aregakn”.

Since the Armenian word “akn” has the meaning of “eye”, “spherical and circular

object, ball, wheel” and “a hole, fissure in the earth from where water emanates; a hole in

1 H.Ačaryan, Armenian etymological dictionary. See article on “ariwś” (in Armenian).

2

general through which water, light, air pass”, then the word Aregakn can correspondingly be

interpreted as:

a. Aregakn= eye of Areg/Arew

b. Aregakn = ball of Areg/Arew

c. Aregakn = hole (from which the light emanates) of Areg/Arew

In Armenian all three of these interpretations are acceptable as characteristics of the

Sun. However, the (god of) Aregakn=”(god of) sun” is written dUD.IGI2 in Sumerian,

Akkadian, Hittite, and Urartian. We will refer to the areg/arew reading of the UD cuneiform

sign shortly, but the igi=“eye” reading of the IGI cuneiform sign represents the Armenian

word “ak(n)”. In other words, Aregakn = eye of Areg/Arew is a more favourable

interpretation of this form.

The = Aregakn sun character, having kept its appearance and meaning over

millennia, has also been used in the Armenian Medieval Book of Knowledge Signs. Moreover

on that journey it has taken on new “loads”, and has been ligatured to other characters ( ,

, ), which represent one or other of Aregakn’s characteristics.

And why Aregakn and not Arew?

Is it possible that there is a difference in meaning between these words?

It turns out that there is and this is what H. Ačaryan writes about it. “In correct

Armenian, aregakn and arew are differentiated by their meanings in that aregakn is the star

and arew is its light.”3

Thus we have two descriptive appellatives for the sun in Armenian – Arew/Areg, the

ideograph of which is the image of a lion, and Aregakn, the ideograph of which is = “sun”.

This piece of evidence in Armenian also makes the worship in the pantheons of the Ancient

World of the twin gods of the sun (dUTU and dNerigal – Sumer; Helios and Apollo – Greece;

Vahagn and Mihr –Armenia etc.) comprehensible.

In the petroglyphs of Syunik, we also see the =“sun” character on the goat

“blackboard” (see picture 3a). This means that the engravers of the Syunik petroglyphs

worshipped the God Aregakn. We can

read this picture as Diq Aregakni=“God of

the sun-star”, where we can read the “dig”

name of the goat as Diq=“god”, on the basis

of homonymy. In the next picture (picture

3b) the image of a lion is ligatured to the

images of a goat and dot in a circle. This

composition should be read from top to bottom, Diq Aregakn Arewi = “the god of the light of

the (daytime) star”. In this way we see that the appellatives, Areg/Arew and Aregakn were

already differentiated at the time of the engraving of the petroglyphs and different

ideographs were created for their ideography; i.e., the engravers of the petroglyphs

Picture 3. Examples of ideographs of the name

of the sun god in the petroglyphs of Syuink:

ba

2 Cuneiform specialists present this writing in the dUTUŠI or dUTU-ši form, where the U2-TU=UTU is the

ideograph writing for the Areg-Arev meaning and UD is the reading of the cuneiform sign, and ši is the reading

of the IGI cuneiform sign. However these forms are purely a formality because they are not interpreted by the

specialists. 3 H.Ačaryan, Armenian etymological dictionary, see article on Aregakn. (In Armenian)

3

worshipped two sun gods, whose names have reached us through much later sources as

Vahagn and Mihr.

One more clarification concerning the synonyms expressing the meaning of “god”, so

that we understand what other ideographs of words with the meanings of “god” are in the

petroglyphs of Syunik.

In Armenian there is a series of words expressing “god” one of which is the original

word astuaś=ast-u-aś, the “ast-“component of which is homonymous with the ast component

of asteł=ast-eł=astł=“star”, and astičan=ast-i-čan=“step of a ladder”. The word astuaś has an

abstract meaning and it is not possible to draw it, but star and step are possible to draw,

picture. The following signs are given in the Medieval Book of Knowledge Signs for the

“star” meaning” , , and for the “step” meaning, the sign, which portrays a

ladder, is given. For the image of a true step ( ) the Book of Knowledge Signs gives a

meaning of “firm”. The verb is hastatel =“to reinforce, make, create, invent” and the root is

“hast”. The latter is the native Armenian root azd, ast=“power, influence, impact”, with an

«հ» augmentative.

The root “hast” with the –iĉ=“doer, performer” suffix gives us the word hastiĉ=“creator,

maker”. Here we already have a unique characteristic of God and comes from the meaning of

azd, ast, hast =“power, impact”. As a result we see that, with the objective image of the step

( ) and the “ast-” component of its appellative, it is possible to ideograph the abstract word

“hast/ast/azd” and the words hastiĉ=creator, maker”, derived from it, as well as the word

Astuaś=”god” compounded from the same root.

The step sign= is frequently encountered in the petroglyphs of Syunik. It is also

present in the signs discovered at the temple complex of Portasar (Göbekli Tepe). We will

refer to these in detail, separately.

Our other alternative to the

ideograph of the word Astuaś by

using its root “ast” is the star sign.

The three star signs for the “astł”

meaning as testified in the Book of

Knowledge Signs and as mentioned

above are also present in the

petroglyphs of Syunik. Of these, the

eight-pointed star sign has been used

with the “astuaś(=god)” meaning in

Sumerian pictography, and the

cuneiform sign ( ) arising from it has been used with the same meaning in all cuneiform

languages.

Picture 4. Examples of ligatures of Lion and Star

characters in the petroglyphs of Syunik.

The ( , , , , , )4 star signs with different numbers of points

(from five to twelve) have been used both in the petroglyphs of Syunik and in Sumerian

pictography. In the petroglyphs these star signs have also been ligatured to the image of the

4 A. Falkenstein, Archaische Texte aus Uruk I, Münich, 1936, №192

4

lion. In addition, it has been ligatured to the tip of the tail of the lion, its mouth or placed on

its back (see picture 4).

Consequently if we read the star sign as Astuaś(=god), and the lion image as

Arew/Areg(=sun) – then for the aforementioned ligatures we have God of the Sun=Astuaś

Arewi/Aregi.

The use of the ligature of the star sign and the lion image reaches into the period of the

spread of Christianity. In some cases the meaning of the star sign has been lost or has been

identified with the Sun and has been replaced by the image of the radiating disk of the Sun.

(See picture 5c, d).

Picture 5. Ligature of the “astł” and “aryuś” signs: a)from the Syunik petroglyphs; b) Greek

money from the town of Mileţ (190 BC); c) image of the “Aryuś(=Lion)” constellation from a

XV century manuscript; d) ligature of the images of the Lion and Sun, which became the

coat-of –arms of Iran in 1423.

c a db

This much for now about the possibility of using the lion image as the ideograph of the

word Arew. Below we will see that this tradition of using the lion image as the ideograph of

the Arew/Areg name also existed in Sumerian pictography and then cuneiform, and also in

Egyptian hieroglyphic writing.

areg, aŕeg, arek=“powerful, strong, excellent, higher, most”. The lion image can also

be used as the ideograph of this word, homonymous to the “areg” appellative of sun. The

images in picture 2 can be read both as Areg Astuaś=“god of the sun” and also as Areg/Aŕeg

Astuaś=“powerful god”.

It is well known that the lion image served as the symbol of royal authority. Based on

this perception, it follows that the ideograph of the word meaning “king, monarch” also used

the lion image. Of course that would fall within the framework of the meanings of the word

“areg, aŕeg, arek”. In the sense of homonymy, the Armenian word “arqay(=king)” fits these

words and the appellatives of lion. Its simple root is “arq”, which is used in Armenian dialects

with the meaning of “authority”.5

If we take into account the k/g>q sound change specific to Armenian and the

peculiarities of ideography, then in the ideograph of the word areg/areq, the vowel between

the two consonants is ignored and it is possible to ideograph the word “arq” from the

objective image of the name arew/areg. Exactly the same was done in Sumerian pictography

and later in cuneiform.

Amongst other forms in Sumerian, the word meaning “king” was written in a

cuneiform sign derived from the image of a lion, with the well-known reading of PI-RI-

IG=PIRIG. We will touch upon cuneiform signs with this reading in more detail, below. 5 H.Ačaryan, Armenian etymological dictionary. See: “arqay” (in Armenian)

5

Here we will only mention that the PI cuneiform sign has the a3 reading, the RI sign has

readings of ri, re, and the IG sign has readings of ig ,ik ,iq, eg, ek, eq. So, we can present the

PIRIG ideograph with the readings of areg/arek/areq. However this is how the Sumerian

scribes wrote the names of the sun and the lion (more about this below). In order to

differentiate the meaning of “arqa” from them, they replaced the IG cuneiform sign with the

KI cuneiform sign, which has the readings of ki/ke, qe2/qi2, ge /gi PIRIG = pi-ri-ki, with

the Akkadian šarru=“king” placed before it (Lu I 36, Lu I 37). Therefore PIRIG = pi-ri-ki=a -

re-qe = arq=արք= king. That is why and how the lion became the symbol of regal

authority. This is where it got its title as “king of the beasts,” when in the cat family, the tiger

is actually larger, stronger and wilder than the lion

5 5:

3

2

.

Only homonyms present in Armenian allow for such ideography. In the environment

of a foreign language, where those homonyms are absent, the image of the lion changes from

an ideograph to a symbolic sign which does not explain the king-lion link and is perceived as

a conventional character.

aru=“an abundant spring, rivulet, current”, “water way, canal, groove, exit, opening”.

In Armenian this word is homonymous with the “aroy(ś)” and “ariw(ś)>aŕyu(ś)>aru(ś)”

appellatives of the lion and consequently the lion image can also be used for this ideograph .

With the above-mentioned v>g sound change, the word “aru” also acquired the arog =

“spring, irrigating water” form, and the latter became “orog” by an initial vowel change.

When we study the petroglyphs from the point of view of the homonymy of the words

“aru/arog” and “aroy(ś)” it becomes immediately obvious that the lion has frequently been

depicted in a setting with water signs (see: Picture 6, first row.)

Picture 6. Examples of ligatures of the lion image and water signs.

Of all the abstract signs in petroglyphs, the kēt=“point” sign ( ) is more frequently

ligatured to the lion image (see picture 6, second row). We will touch on this character in

more detail in the section on abstract signs. At this point we will just mention that in

Armenian, based on the homonymy of ket, ged=“geometric sign” and get, ket, ged=“river, an

abundant current of water”, the “ket” sign can be read get=“current of water”. Therefore we

can read the ligature of the lion and dot characters as:

a. Ket + aryu(ś) = get+aru, get+orog = “river irrigator”

b. Ket + aryu(ś) = get+aroy = getar= գետառ = “mother river, out of which flow the

irrigator rivulets.”

In both cases we come to the conclusion that it is possible to create the ideograph for

the word գետառ=getar=“mother river, irrigator river” by ligaturing the dot and lion images.

6

We have already spoken about the fact that short formulae bearing mythological meanings

were written by means of the petroglyph ideographic characters of Syunik. In this case the

“getar” reading of the dot+lion ligature must be understood as having the meaning of the

mother river (=Nagar=Haia) in the Book of Genesis.

In Armenian, the word “հաւառի=hawari” also has the meaning of “mother river”. The

former is formed from the “haw-” and “-ari” components, the first of which is homonymous

with the native Armenian word haw=“bird”, and the “-ari” component belongs to that series

of words which can use the lion image as an ideograph. Therefore, in order to create the

ideograph for the word hawari=“mother river”, it is necessary to ligature the lion and bird

images or to ligature bird wings to the image of the lion (we will refer to this interesting

pictography below). The existence of the Sumerian word hu-bu-ur=hu-bu-ura=hu-bu-

uru13=hubur/hubura/huburu=“underworld river, underworld sea current” is an important

testimony to the prehistoric existence of the word “hawari” and its ideography in the above-

mentioned form. This very river would be called Mother River since all springs and rivers

flow from it, from the bowels of the earth.

The syllable hu in the name hubur is the reading of the HU cuneiform sign; it bears the

meaning “bird” and is used as a determinative of the meaning of “bird”. This Sumerian word

is the exact duplicate of the native Armenian word հաւ=haw=“bird”: Hu=haw=“bird”. The

bu-ur component in the river name is identified with bur2=bu-ur=“to be burned, to be

inflamed, to gleam, to radiate,” the Armenian parallels of which are բուռ(ն)(=bur(n)) from

which, brnkil=“to be burned” and վառ(var)=“burned, shiny”. One of the appellatives of the

Sun God is written with this word: dBur2-ra=Աստուած Վառի(God Vari) (Ananum Tablet 7

71), (the –ra is the genitive case particle and the Armenian must also be written in the

genitive case, “var-i”). As a result – haw-vari=hawari= “mother river”.

The fact that Hubur has been used as a synonym of one of the cuneiform appellatives of

Armenia (Šubartu) is also important.

Hu-bu-urki = Su-bar-tum (Hh XXI-XXII Appendix 1 obv. 9):

Arog, aroyg =“powerful, vigorous in body”. This word in Armenian is homonymous

with both the “arog” form of the word “aru” above and the mentioned lion name forms. This

word is formed by the “ar-” prefix and the separate, obsolete root *oyg=“power, strength”.

With the g>ž conjunction we have the synonym oyž=“power, strength”. Linguists

consider the roots oyg and oyž to be loan-words from middle Persian. In reality the

Armenian word oyg is identical to the Sumerian ug, ug2, ug4 words which have the meanings

of “powerful, strong, firm” (Akk. dannu) and represent the readings of the PIRIGxUD,

PIRIG, UD cuneiform signs having the “lion” and “sun” meanings. We will touch upon these

shortly.

Perhaps it is necessary to add the root ayr=“fire” from which comes ayrel=”to burn”, to

this list. This root is also affixed in the forms “ayroş-, ayreaş-, ayreş-, ayraş-” the

ideograph of which, the former being words which express abstract meanings, could be

represented through homonymy by the lion image and pronounced through the root forms

of lion mentioned above. Moreover, if the ideograph of the word “arew/areg” did use the lion

form, then the same image, with the presence of another determinative could also represent

the effect of the burning summer sun (ayreş-, ayraş-, ayroş-). We will shortly see that the

ideograph of one of the widespread names of the god Nerigal uses the lion image and that

7

very embodiment of the burning warmth of the Sun is one of the main features of Nerigal’s

character.

The ideograph of the words presented above which could be represented by the lion

image are distributed into four semantic groups, according to the meanings they express.

a. arew, areg; ayr, ayroş-, ayreaş-, ayreş-, ayraş-; - these are grouped around the idea of

“heavenly fire, light (=sun), fire, to burn”.

b. aru/arog; – the meanings of this word are linked to water elements (rivulet, spring,

irrigator water, current).

c. areg, arek, arq; arog, aroyg – this group of words expresses the idea of power,

strength, authority.

d. Based on the “hole, exit, opening, groove” meanings of the word aru, we can assume

that it could also be used with the meaning of “door” with the ideograph of the lion image.

In order to be convinced that the ideographs of the above mentioned words were really

represented by the lion image in the Syunik petroglyphs, and that that custom had continued

in subsequent ideographic writing systems, we must refer to information from Sumerian and

Egyptian languages, which are currently

considered to be the oldest written languages

in the world.

Firstly let us refer to certain data about

the Sumerian civilization which has reached

us through the efforts of archaeologists,

according to whom the lion image appears in

Lower Mesopotamia from early Ubaid times

when the foundations of the Sumerian

civilisation were being laid. One such piece

of information appeared during excavation in

the oldest Sumerian city of Eridu (beginning

of the VI millennium BC). The oldest

Sumerian temple was built in Eridu. It was devoted to Enki God and represented the core of

the Eridu civilisation, around which the city was shaped. The ideographic appellative of the

temple of Enki God has reached us through cuneiform sources in the form of E2.ZU.AB

Akk. bīt apsû), which literally means “house of the Sea” (E

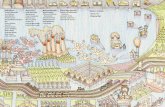

Picture 7. Reconstruction of the Hay God

temple (Eridu VII) according to the excavated

ground plan.

(

gy.

2=“house, temple”, ZU.AB=zu-

ab>zu-aw=ծով(śov)=sea, pool). In Sumerian, the subterranean pool of life-giving sweet-water

from which the springs arose was called Sea. This idea of the Sea is identical to the Śirani

Śov, Arun Śov of Armenian mytholo

The oldest excavated foundations of the temple are from the middle of V millennium

BC (Eridu XI). The temple was reconstructed several (over 17) times. A version of one of

these reconstructions (Eridu VII, end of V millennium BC) is shown in picture 7. Eventually,

Ur Nammu (~2112-2095 BC) the founder of the Ur III dynasty builds a ziggurat on the ruins

of the Enki God temple. The temple is probably ruined in the XXIV century BC, when the

Semite tribes first invade Sumer.

During excavations archaeologists come across twin lion statues at the entrance to the

Enki God temple (see picture 8a). Sumerian written sources6 also mention the twin lions in

6 See e.g.՝ Inana and Enki, Segment A, lines 11, 23

8

front of the Enki God temple. Of course as lion images, those statues expressed a specific

meaning, which we will touch upon shortly.

The lion images discovered in archaeological material from Sumer and Elam are more

frequently encountered on stamps (see picture 8b, c, d)7

Picture 8. a) Lion statue from the Enki God temple (Eridu); b, c, d) Mesopotamian stamps

with the lion image (Uruk V-IV; IV millennium BC, second half),

e) Hurrian stamp with image of lion and goat (III millennium BC).

cb

a de

Subsequently, although the traditions of pictography, particularly the use of the lion

image (seals, statuettes, bas-reliefs) continued to be used in Sumerian culture, in the last

quarter of the IV millennium BC, the process began in the Sumerian writing system of

schematisation and then transition of images to cuneiform writing. The lion image has also

been subjected to these transformations as a result of which the ideographic cuneiform sign for “aŕyuś” was created. The reading for the latter of PIRIG=“aryuś” has been reconstructed

by sumerologists. Three cuneiform signs have the reading of PIRIG and the meaning of

aryuś=“lion”. These are presented in the table below:

Sumerian

cuneiform sign Name of the

cuneiform sign Reading of the

cuneiform sign Meaning of the

reading

PIRIG pirig lion

UD pirig2 lion

PIRIG×UD pirig3 lion

As we mentioned, the PIRIG cuneiform sign has developed from the image of a lion

and the meanings of the cuneiform sign are “lion”, “power, strength” and “light, shine”. The

pictogram of the UD cuneiform sign ( , , , , )8, and also the

Egyptian hieroglyphs , (with unknown phonetic values)9, are identical to the

7 The reader can find many pictures in, for example: P. Amiet, La glyptique Mesopotamienne archaique, Paris,

1961 8 A. Falkenstein, Archaische Texte aus Uruk I, Münich, 1936, №194 A. Falkenstein, 9 N. Grimal, J.Hallof, D. van der Plas, Hieroglyphica, Utrecht, Paris, 2000

9

Armenian aravot=“morning” character in the Armenian Book of Knowledge Signs ( ,

).10 The prototype for all these are the petroglyph characters of Syunik

( , , , , , ).

The ideographs of words with the meanings of “sun, day, light, shine, hot, summer” and

the name of the Sun God are expressed by the UD cuneiform sign. The pirig2 reading of this

cuneiform sign bears the “lion” and “vivid, shiny, radiant, luminous, bright” meanings. The

PIRIGxUD cuneiform sign is the ligature of the previous two, where the pirig3 reading also

bears the “lion”, “vivid, shiny, radiant, luminous, bright”, meanings.

Thus we see that in Sumerian also, the ideograph of the words arew=“sun” and

arew(ś)=“lion” use the same character. In order for the ideograph of the word arew(ś) to be

the sign meaning “arew”, the appellatives of the Sun and the lion must be homonymous, i.e.

sound the same. Otherwise, the ideograph with the “arew” character could not represent the

word meaning lion.

However as we see, the readings of the Sumerian UD or UTU=sun ideographs are not

homonymous with the word pirig, meaning “lion”. The requirement that the words

signifying lion and sun be homonymous gives us grounds to assume that the reading of

pirig=“lion” needs adjustment. The fact that there is no pirig=“lion” word in any language in

the region is the basis for such an assumption. The only one that is close in sound is the

Persian “palang” and Armenian “pǝlǝng” word which is used with the meaning of “tiger” (see

for example the branch of Daviţ from the “Sasna Śrer” epos). Perhaps at some time or other

the words pǝlǝng=pirig(?) and arewś=“lion” were used as synonyms. However, we can

immediately reject this version because this also does not have a homonym with the meaning

of “arew” in either Armenian or Persian.

So all that is left is to assume that the misunderstanding comes from the incorrect

reading of the word PIRIG with the meaning of “lion”. Let us ascertain what different

readings there can be of the word PIRIG, of which the forms of syllabication are:

PIRIG = pi - ri/re - ig/eg (Proto-Ea 572; Sb Voc. I Rec. B205 etc.)

PIRIG = pi - rig/reg (Sa 223; Aa III/3 81; Ea III 144b etc.)

PIRIG = pi - ri = pi - rig5/reg5 (Sa Voc. Frag. L 3’-5’ etc.)

In order to solve our problem it is first necessary to know the list of readings of

cuneiform signs which are in the syllabication of the word PIRIG. They are as follows:

= PI = a3, am7, aw, bax, be6, bi3, bux, dax, ex, ew, geltan, gešdu, ĝeštug, geštug, ĝištug,

gištug, ĝeštu, geštu, ĝištu, gištu, geštunux, gišdu, gištunux, ĝestug, ĝešdu, ĝistug, ĝišdu, i16, iu2,

iw, ma9, meštunux, me8, mi5, mištunux, muštu, muštug, neda, niĝĝeštug, pa12, pe, pi, ta7, tal2,

tala2, til7, u17, uštu, uštug, uw, wa, we, wi, wu, ya, ye, yi, yu - (58 readings)

= RI = bagx, bakx, dal, dala, de5, degx, di5, ere, eš11, ĝešdal, ĝešdi, hux, ri, re, rig5, ša7, tal, tala, ţal - (19 readings)

10 H.Ačaryan, Armenian letters. Yerevan 1984, Appendix, page 687 (in Armenian).

A.Abrahamyan. Armenian letters and writing, Yerevan, 1973, page 237 (in Armenian)

10

= ŠIM = bappir2, bappira2, asila2, asilal2, asilla2, lumgi, lunga, mud5, mulugx, ningi, nugx, nungi, rig/reg, rik/rek, riq/req, siraš, šem, šembizi, šim, siris, siriš, su20, šembi2, šembulugx, ši6, šimbizi - (29 readings)

= IG = da11, eg, eĝ, ek, eq, ga7, gagal, gal2, gala7, ĝal2, ig, iga, ik, iq, kagar, mal3 (16

readings):

The observant reader probably has already noticed that the -ri/re-ig/eg, -rig/reg, -

rig5/reg5 = -rig/-reg component of the syllabication of the word pirig is exactly identical to

the “-reg”, “-rew” component of the Armenian «areg” and “arew” names of the Sun (taking

into account the g>w conjugation). Therefore, if we substitute the first pi- syllable in the

reading of PIRIG with an “a” sound, we get areg/arig/arew/ariw, which corresponds exactly

to the Armenian appellatives of the Sun. And of course we can do that because the reading a3

is amongst the readings for the PI cuneiform sign (let us recall that the numerical index

placed next to Sumerian words has nothing to do with the reading and merely shows how

frequently the reading of the given cuneiform sign was used in the series of homonymous

readings of other cuneiform signs. For example, there is the index 3 next to the a reading of

the PI cuneiform sign, because, a3 is the third in frequency of use amongst other cuneiform

signs with the reading of a).

Thus we can prove that the words with the meaning of “sun” and “lion” are also

homonymous in Sumerian and moreover, that they (areg/arig > arew/ariw) are identical to

the Armenian words areg, arew=“sun” and arew(ś) , ariw(ś)=“lion”.

Let us bring an example of the use of the PI-re-eg, PI-reg = a3-re-eg, a3-reg = areg,

arew reading of the UD and PIRIG cuneiform signs, with the meaning of “sun”. One form of

writing the appellatives of the four corners of the world in Sumerian is as follows:11

Appellatives of the four corners

of the world The Akkadian

appellatives of the

same

The corresponding

four corners of the

world pirig-ban3-da šu-u2-tu2 south pirig-nu-ban3-da il-ta-nu north pirig-si-sa2 ša2-du-u east pirig-nu-si-sa2 a-mur-ru west

Of course the word PI-re-eg, PI-reg = a3-re-eg, a3-reg = areg has nothing to do with

the lion in these appellatives; it presents the word areg/arig=arew/ariw=”sun”, because the

four corners of the world are defined by the specific positions of the sun: south=the lowest

point of the sun (the newborn sun at the start of the year), north=the highest and strongest

position of the sun, east=the direction of the sunrise at the equinox and west=the direction of

the sunset at the equinox.

We also see that the appellatives south and north and east and west differ from each

other by the syllable -nu- placed at the end of the word PIRIG = areg/arig, arew/ariw = “sun”.

This is a Sumerian negative particle which is identical to the Armenian negative particle “an-

”. Therefore it must be assumed that in whatever meaning south (ban3-da) and east (si-sa2)

were described, north (nu-ban3-da) and west (nu-si-sa2) were used in the opposite meanings,

respectively. The above-mentioned Sumerian appellatives describe exactly those positions.

11 Erimhuc II 78-81

11

Here, in pirig-ban3-da=areg banda, the areg component represents the Sun and in the

banda component we can see the Armenian root band/bant=“tie, bonds” or vand (from

which comes vandel=“to hold, repulse, persecute”).12 Hence, we have the areg banda= aregnaband or aregnavand forms for the appellatives of south. As a result, the south and

north in which the sun reaches its highest point in winter and summer, respectively, are

given according to their natural characteristics (held and untied).

As far as it concerns the word si-sa2=şi-şa2=sisa, şişa=“straight, vertical, stick out”13,

the identical Armenian word is “şiş”, from which comes şşuil= “stick out, stick up vertically,

sprout, to bud”: In these senses, the word “şiş” is a synonym of the word “śag” (śagel= “come

out, appear, sprout”) and could be used to characterize the rising of the sun. Therefore areg

sisa/şişa=arewaşiş/arewasis= “the sticking out of the sun, the coming out of the sun” is the

characteristic of the east. Let us pause here, distance ourselves from the topic of the lion for a

short time and, taking advantage of the opportunity, try to follow the tracks of the meaning

of the word « şiş » discussed above, because in that we see the key to the etymology of the

toponyms of Syunik = Sisakan, which relate to our issue.

INTERPOLATION I (Interpretation of the name of Syunik)

As we saw above, Sumerian helped us to expand the framework of meanings of the word “şiş” and to use it as a description of east. Sumerian also shows the existence of the si-sa2=sis=սիս and şi-şa2=şiş=ցից parallel forms (also written as zi-zi. compare:. GIŠ zi-zi = “erect penis”). In this case, it is tempting to etymologise the old name of Syunik, Sisakan through şiş= sis. The Syunik and Sisakan appellatives have been used in parallel in literature, both as the name of the land and the name of the family (ministerial house of Sisakan).

Since one of the synonym appellatives (Syunik) is obviously formed from the word siwn=“erected wood or stone, stake”, then it is logical to derive the other appellative (Sisakan) from the synonym of “siwn”, şiş, sis, i.e. assume the initial *Şişakan form, and from that Sisakan. In this case we consider it probable that the town name Sisean>Sisian originated from the megalithic structure in its vicinity: *şiş-ean=sis-ean=“şiş, sis, stones” where “- ean” is the plural collective particle. Therefore the toponym must literally mean “erect (stones)” and there is no need to artificially re-name them Zoraş Qarer or Qarahunǰ, as some researchers do.

12 Linguists consider the Armenian word band/bant as a middle Persian loan-word on the ridiculous reasoning

that since Armenian has the word “pind” from the the Indo-European prototype then “bant” must be a loan-

word from middle Persian (see H.Ačaryan: Root Dictionary, “bant” article). But the meaning of “prop, support”

may be attributed to the Sumerian word banda which should be understood as tying in another sense (to

strengthen by tying or using a support to strengthen). 13 The e-dictionary of the University of Pennsylvania gives the meaning “to make straight; to make vertical”.

12

The first etymology of Sisakan was given by Movses Khorenatsi (V century). linking the toponym and the family name to the name of Sisak, the son of Gełam. Subsequent etymological attempts have not been accepted (Hübschmann, Lagard, Adonş et al.).14

Firstly, our interpretation corresponds to the geographic features of Syunik. Syunik is a mountainous “island” (a column, a spike) in relation to the surrounding territories: the Araqs and Qur valleys. Syunik is also a land of naked, protruding mountains and peaks (columns, spikes) from the internal, geographic aspect. Here we can also include the man-made megalithic structures and serpent stones (monoliths) strewn all around Syunik.

However we do not think that if the name Sisakan arose from the word şiş/ sis, then it is linked to the geographic features of the region. In reality, as in Sumerian, the şiş/sis, root of the name Sisakan appears as a feature of the east. As a result Sisakan previously meant “eastern”. This truth also belongs to the list of facts which played an active role in prince Sisakan becoming one of the four consuls of Medz Hayk’ (Great Hayk’/Great Armenia) and the one responsible for the defence of the eastern side of the country. Subsequently the word şiş=sis became perceived literally as “erect, column” and the parallel appellative of Syunik (land of columns) was created. If we look at the geographic picture of the region from the point of view of the Upper Palaeolithic and Early Neolithic periods, then the eastern limits of the Utik and Artsakh

lands of Great Armenia were flooded by the waters of the Caspian Sea (Khvalyn transgression). Therefore for the dwellers in the Syunik mountains and those in the lower lands of Artsakh and Utik, the sun would rise over the waters of the Caspian sea, i.e. the territories mentioned would justly be given the general name of the eastern land. In other words they were called eastern land not because they were on the eastern side compared to the other parts of Great Armenia but because the sun rose over that sea which, according to ancient perceptions, surrounded the Earth.

Picture 9. One section of the megalithic structure

near Sisian

In this case we can identify Syunik, Artsakh, and Utik with the Garden of Eden. “And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed”:15 If we can identify Great Armenia with Eden, as the land of the sources of the Euphrates and Tigris, then the lands of Syunik, Artsakh, and Utik are the eastern side of Eden and must identify with the garden of Eden and the country of Khavila/Evilat in the Book of Genesis. Mesopotamian cuneiform sources tell us that the ruler of the land of Khavila is the god Nerigal. dNe3-unu-gal = LUGAL Ha-wi-lumKI=“the king of the land of Khavila” (RA, 1, 1,

14 S. Umaryan: The pantheon of Syunik. Yerevan, 1981 15 Book of Genesis II, 8

13

12);16 This country name of Hawila is identical to the Armenian word *xawil>xawił=«orchard, garden, paradise:17 We will talk further about the geography of Syunik in the Upper Palaeolithic period, but now, having the image of the king of paradise, Angeł = god Nerigal before us, let us return to the examination of the lion images in the rock pictures of Syunik.

Let us refer to yet another example of the use of the word PIRIG= “lion” with the

meaning of “areg/arew” in Sumerian. This is one of the names of the god Nerigal, which is

written in the following forms:

= [email protected] = nergal

= PIRIG.ABxGAL = nergalx

The readings of Nergal and nergalx are attributed to these ideographic forms,

respectively. For the reading of a deity’s name, the following readings and meanings of the

cuneiform signs are taken:

ABxGAL = erigal, irigal, urugal = “subterranean world, underworld, bowels of the

earths” (Akk. erşetu, irşitu)

AB@g = iri11, eri11, ere11, unu = “settlement” and urugal2 = “underworld”

GAL = gal, qal, kal2 = “large; secret, hidden, detached, distant”

Consequently for the mentioned name forms of the god Nerigal, we have:

[email protected] = PIRIG iri11/eri11/ere11-gal=PIRIG eregal/erigal/irigal,

= PIRIG unu-gal= PIRIG unugal

= PIRIG urugal2

PIRIG.ABxGAL = PIRIG erigal/irigal/urugal:

Here in every case the PIRIG ideogram representing the reading of the lion image

presents the word areg=areg/arew = “sun” which is already familiar to us. As far as the words

eregal, erigal, irigal, urugal, unugal are concerned, sumerologists have reconstructed the

meaning of “underworld, bowels of the earth, subterranean world” for them. Let us find the

Armenian parallels for these.

We already know that St. Sahak Partev and St. Mesrop Mashtots used the deity name

Angeł in place of Nerigal in the Armenian translation of the Old Testament. The reader also

probably noticed that, in the name forms of Nerigal given above, the Unugal component

(u=a) of Areg Unugal is identical to Angeł; Unugal>Angel/Angeł=Անգել/Անգեղ.

Consequently the full name of the deity will be Areg Angel/Areg Angeł.

The other forms of writing, Areg eregal/erigal/irigal/urugal/urugal2, represent the

name of the deity Areg Aragel/Arageł=Արեգ Արագել/Արագեղ, where the Aragel/Arageł

component is well- known in Armenian mythology.

The Areg component of the ideogram represented by the lion image in these deity

names is the Sun. Now let’s try to understand the meanings of the Angeł and Arageł

components. Let us start with the characteristics of the Sun God *Aragel > Arageł.

16 Տee: A. Deimel, Pantheon babylonicum, Romae, 1914, p. 191 17 H.Martirosyan: Heavenly and earthly Eden, Pages from the Ancient History of the Armenians. Yerevan,

2001, p. 5

14

The name of the deity Arageł has traditionally been split into the “ara” and “geł”

components. This was first done by Movses Khorenatsi (V century) who mentioned the

name of the deity (Ara Gełeşik) and attributed the “geł” component with the meaning of

“beautiful”. We consider this folk etymology, the purpose of which was to make the legend

of “Ara Gełeşik and Šamiram” explicable.18

We also split the name of the deity Arageł into the components “ara” and “geł”

however we elucidate the component “geł” with the meaning of goł, gał, geł=“cover, hide,

conceal, keep”. These interpretations are also prompted by the Sumerian data, because the

word gal/kal2/qal has:

a. the meaning of “big, large” the duplicate of which is the Armenian word gał=

“much, large” from which, by repetition, gałgałel = “make larger”

b. the meaning of “distanced, isolated, hidden” of which the Armenian parallel is goł,

gał, geł= “cover, hide, conceal, keep”.

Although this interpretation of the word geł is considerably sound, however in

Armenian gil/gel/geł also bears the meanings of “round, gem, wheel”, as well as “eye, hole,

cavity”. For example, in the expression աչքի գիլ(achqi gil)= “eyeball”, the word “gil” bears

the meaning of “round, circle, gem, wheel” and the “gel” root in gelikon/gaylikon=”an

instrument for opening a hole, drill”, bears the meaning of “orifice, cavity”. The parallel for

these also exists in Sumerian. The readings of geli3, gili3, of the KAxLI cuneiform sign,

having the initial meaning of “hole, cavity”, have been used with the meanings of “throat,

trachea”. Therefore we can also attribute the meaning of “entering or exiting point, hole,

orifice, cavity, exit, door” to the gel/geł component of the deity name Arageł.

Consequently, in order to ascertain the entire meaning of the deity name of Areg

Arageł we need to elucidate the meaning of the “ara” component. This of course derives from

the polysemantic root “ar”, the main meanings of which are ar=“build, make, create”, and er/

era=“first”, eri=“first (leg of animal)”, ar=“ forward, the front”. These meanings do not

introduce any certitude to our problem, and additional explanation is needed. For that exact

reason, let us once again deviate from the topic proper.

INTERPOLATION II (Underworld, Earth, Heaven)

The link between the deity name being discussed and the sun hints that the word “ar, ara” must be the characteristic of one of the main components of the structure of the universe. The Sumerian term urugal, eregal, erigal, irigal=“underworld” also testifies to this. Moreover, it is obvious that the Sumerian word uru-, ere-, eri-, iri- corresponding to the “ar-, ara-” component of Arageł bears the true meaning of “underworld”. The meaning of “settlement, city” is attributed to the former in Sumerian. The Sumerian word a-ra-li, in which the ara component that is of interest to us is also present, also bears the meaning of “underworld”. Certain cuneiform dictionaries directly

18 Movses Khorenatsi, History of the Armenians, A. 15

15

testify to the equivalence of ara=a-ra2=er-şe-tu="underworld” (see for example CT 51 58-63 no. 168 iv 65). The UD cuneiform sign also has the er-şe-tu=“underworld” meaning and ara7 reading (Aa III/3 1-21 9). The fact that according to many Sumerian sources, Nerigal is the ruler of the underworld is also significant. We think that this fact is also manifested in his dEr3-ra, dIr3-ra name. The Er3 and ir3 (and also eri3, eru) readings belong to the ARAD cuneiform sign, and the latter bears the meanings of “male”, “man”, “strong”, and “ram”. The words expressing these meanings are homonymous in Armenian and are formed with the “ar”base. Thus: aru (gen. arn)=“male” arn=“male sheep, ram” ayr (gen. arn), ēr(-ik) “man, husband” ari=“brave, masculine” The Sumerian ARAD cuneiform sign represents the ideogram of the homonymous words ayr(gen. arn)=“man” and arn=“ram”. In order to differentiate between them, the determinatives ( sager3=այր(ayr)=“man”, and uduer3=առն(arn)=“ram”) signifying sag/şag= “head, person” (compare Armenian śag=“tip, peak”) and udu=օդի(odi)=“small horned animals” respectively, are added. The Armenian word arnak= “the evil spirit that takes souls to the underworld” (arn + ak particle) should be added to the above list of words. This best corresponds to the character of dEr3-ra,19 as the god of death in Sumerian sources. In Sumerian, ra- is frequently used as the genitive case ending and we can consider the ra in the deity name dEr3-ra both as a genitive case ending and as a phonetic complement to the previous word (er3) ending with an r sound. Therefore, according to the deciphered readings of the ARAD cuneiform sign, the real deity name is Er

n ara does.

3, Ir3, Eri3, Eru, and it corresponds to the Armenian ar, ara, er, era=«first, front» forms. Apart from the mentioned meaning, the latter will also have the meaning of “underworld”, as the Sumeria Is that really so? Is there data confirming that in Armenian? It turns out that the information exists and not only does it confirm the above, but it also helps to understand how the Armenians imagined the three-tier structure of the world in ancient times (Heaven, Earth and Underworld) and what they named each of those tiers. They imagined the centre of the world to be the Earth. In Armenian the name Earth (=Erkir) is identical with erkir=“second”.

The upper part of the world or the roof of the Earth is Heaven. In Armenian the word erkin=“sky” in turn is formed from the root er=եր-եք(er-eq)=“three” and kin=“times” particle. (compare krkin=kr-(=two) + kin(=times)=“doubled, second time, again”). Hence the appellation Heaven literally means “tripled, thrice, third”. In this system, the Underworld is the opposite structure to Heaven, or the support for the Earth. If Earth was called the second, and Heaven third, then the Underworld, which represented the base and support for these, would naturally be called Ar, Ara, Er, Era, Ari,

Eri=“first”:20

19 With his particular mechanical approach, H. Ačaryan, links the word “arnak” to the Assyrian word arnāgā=

“jackal” which is neither semantically nor phonetically acceptable. (H.Ačaryan, Armenian etymological dictionary. See article on “arnak”). 20 A. Sayce was the first to link the Armenian name Ara to Nerigal, but he gave the explanation of the word

“ara” through the Akkadian word aria=”destroyer, demolisher”. (See:՝ A. Sayce, The cuneiform inscriptions of Van, 1882, pp. 415, 416; G. Łap‘anşyan, The worship of Ara Gełeşik. Yerevan 1944, p. 10)

16

There is no other language in which the components of the three-tiered world are named with classical numbers and no other language in which there is a semantic connection between the words denoting Underworld, Earth and Heaven. And from these facts, it follows that the notion of a three-tiered world and the naming of those tiers, as a mythological-worldview system, was born from a way of thought inherent in the Armenian language. This data in Armenian also allows us to adjust the meaning of the word urugal, eregal, erigal, irigal. These readings are interpreted as “large(=gal=gał)” settlement (=uru, ere, eri, iri)”. However, it follows from the above that it is necessary to interpret it as a complex formed from the words “clandestine, hidden, secret (= gal = gał, geł, goł)” and “underworld, bowels (= uru, ere, eri, iri)”. Consequently the word uru, ere, eri, iri=“first, underworld” must be differentiated from the homonymous uru, ere, eri, iri=“city, settlement”. In exactly the same way, by adding a “y” initial sound to the “ar” root, homonymous to the Armenian word ar/ara/year/yeri=“first”, we have the word yar=“get up, stand” which, with the “-ič” particle, gives us the word yarič, harič=”village, township, settlement”. Therefore Armenian also provides the meaning of urugal, eregal, erigal, irigal=“large settlement”. It follows from Sumerian mythology that Nerigal is the God of the Underworld. The name of this god is often written with the PA cuneiform sign (dPA): The latter has the readings of ari3 and aru. Therefore we can present the name Nerigal in the dAri3 and dAru forms. The above interpretation of the Armenian and Sumerian names for the parts of the world gives us grounds to interpret the deity name dAri3 as God of the Underworld (ari3=արի=underworld). We will see below that the dAru appellative of Nerigal is linked to the cosmic gates connecting the Underworld, Earth and Heaven, and the word aru is identical to the Armenian aru=“hole, opening, door”. We bring here just one testimony from Sumerian sources in which the Akkadian word su-u-qi = sūqu=“hole, way; course of brook, canal” is put before the dPA(= dAru)= dNerigal correspondence. (An : anu ca2 ameli 85). We believe further comments are unnecessary here.

Nerigal is frequently mentioned as the king of Gu2-du8-a, Gu2-di city, ( lugal-gud 2-du8-a-ki), where his temple and centre of worship was. This toponym is mentioned in the Old Testament in the form of Kowta/Kowţa (Kings: Book IV): In Sumerian dictionaries, thed

A-ri-a21 syllabogram of his name is often placed before this title for Nerigal.

21 A. Deimel, Pantheon Babylonicum, Romae, 1914, зю 59, №107

For several centuries, in different corners of the world, scholars and people from different strata have been

exploiting the term “Aryan”, for which no solid explanation has been given to-date. One possible explanation of

that term is indicated by Nerigal’s Ari, Aria, Aru name. The followers of the worship of Nerigal may have been

called Aryans. There are two more possible explanations of the term Aryan which we will refer to later and by

comparing them, we will try to ascertain which one of them is true.

A few words about the appellative Gu2-du8-a, the centre of the worship of Nerigal. We identify it with

the “kot-/koţ component present in numerous toponyms in the territory of Armenia (Angełakoţ, Brnakoţ,

Kotayq, Koţi etc.). Many Sumerian toponyms have their parallels in Armenia. Moreover these toponyms are not

etymologised by the Sumerian information currently known. The toponym Gu2-du8-a is one of them. This

name can be etymologised in Armenian with the word koţ=“furious, severe, fierce.” the meanings of which

correspond to the characteristics given to Nerigal in Sumerian sources, (fierce, furious, severe, inflammatory).

For example, the Nerigal dGir3-ra name is composed of the word gir3=“fierce, enraged, inflammatory” of which

the Armenian parallel and synonym of “koţ”, is the root “gir” from which, by repetition we have grgir=“to be

agitated, to be angered, to fight.” Another of Nerigal’s names is written with the ŠU ideogram (dŠU) meaning

ձեռ(zer)=“hand” and կոթ(koţ)= “shaft, handle” (cf. Akk. qātu). Of course such a script can only be possible in

17

These three forms of writing Nerigal’s name are homonymous with the appellatives of lion: “ariw(ś), aroy(ś), areaw(ś)”. Consequently, returning to the images in picture 2, we can say that by carving the lion on the ‘blackboard’ of a goat, the engravers of the petroglyphs of Syunik have created the ideogram for the Ari/Aria name of dNerigal=God Angeł.

Returning to the deity name Areg Angeł, we can already etymologise it as “door, hole

of the underworld” or “hidden, covered sun in the underworld”.22 We will touch on the

“door, gateway of the underworld” interpretation a little later but the “hidden sun in the

underworld” interpretation casts a new light on the legend of Ara Gełeşik, which Movses

Khorentasi and Sebeos23 (VII century) bring. Numerous researchers (N.Adonş, M, Abełyan,

A. Matikyan, G. Łap‘anşyan, et al) have touched on the legend of Ara Gełeşik. However, all

of them,24 ignoring the claim of the source that “when the body began to rot, ordered to

throw it into a great abyss and bury it”25, produce ersatz arguments from here and there to

present Ara Gełeşik as a dying-resurrecting deity. However in reality there is no mention in

Khorenatsi’s source of Ara Gełeşik’s resurrection.

Those who present Ara Gełeşik as the Sun God are right; that is the God

Angeł=Mhir=Nerigal. As far as the dying-resurrecting character of the God’s essence is

concerned, that is wrong. Ara Geł=Angeł=Mihr=Nerigal, the God embodying the Sun of the

Underworld bears the essence of a departing-returning god. In the folk legend, P‘oqr Mher is

just such a one; the Sun hidden in the Underworld. By entering the cave, i.e. the

Underworld, P‘okr Mher set the beginning of the era of anticipation of his redeeming return.

The conclusion of the above authors that there had been a God Ar/Ara in the Armenian

national pantheon is also true but it is incorrect to try and link the name of the deity to the

rigal

the case of homonymity existing between the words koţ= “furious, severe, fierce” and kot= handle”. Let us add,

that in one dictionary the place name kurGu2-du8-a is explained with the homonymous appellation of kurza-'-i-

ri. What is said above gives grounds to identify the name place za-'-i-ri with the form “zayr” which is formed

from the “z” intensifier and the root of the native Armenian ayrel=“to light, to set fire to burn”. The verb form

of the former is “get really angry, to rage.” This last example shows that the notion of fire – which is one of the

main traits in Nerigal’s character - is also at the base of the meanings of the above mentioned names of Ne

“furious, vigorous, irascible”. 22 . Based on the ancient Armenian perceptions of the structure of the Universe as stated above, we can present

the actual word areg=“sun” as a compound formed from the simple roots of ar=“underworld” and ayg, ēg=“arise”

and we can etymologise it as “arising from the underworld”. For the “aregakn” appellative of the sun, we have

aregakn=ar-eg-akn=“akn arising from the underworld” where, for the word “akn”, we can take the meanings of

both akn=”eye”, and also ak=”wheel”. This is more comprehensible from the point of view of ideography

because we can read the same character ( ) as “eye”, “wheel”, “sun”. This etymology of the word Areg is

evidenced by the fact that in classical Armenian it was only used with the meanings of “east,” “eastern” i.e. it

showed the direction of the sun rising. 23 Movses Khorenatsi, History of the Armenians, A, 15

Sebeos, History A 24 N.Adonş, The world view of the ancient Armenians, Hayreniq, Boston,, 1926-1927; M. Abełyan, The

legend of Šamiram,Works, h,Ǝ, Yerevan, 1985,p. 242; A. Matigean: Ara Gełeşikǝ, Vienna 1930; G. Łap‘anşyan: The story of Ara Gełeşik, Yerevan. 1944 , (In Armenian) 25 Movses Khorenatsi, History of the Armenians, A, 15

18

Sun (the word and the star).We saw above that the word “ar, ara” bore the meaning of

“underworld” and that God Ar(a) =dEr3-ra meant God of the Underworld:26

We think it is necessary here to briefly familiarize the reader with the ancient

perceptions of the Underworld.

INTERPOLATION III

(Creation is from the Underworld)

The perception that the Underworld is death, the grave, hell, the place where evil souls reside is entrenched in the mentality of modern man (be he Christian, Muslim, Buddhist or Atheist). Eternity, creation and other positive perceptions are linked to the luminous, bright and blue Heavens. We see the beginnings of similar perceptions in the first millennium BC (Indo-Aryan Mahabharaţa and ramayana eposes, interpretational literature of rigveda, Zoroastrianism, Hebrew Old Testament, Greek mythology etc.). These perceptions also played a certain role in 1865 when the German scientist H. Richter propounded the idea of panspermia (πανσπερμία). The term is formed from the Greek words πᾶν= “uni, whole” and σπέρμα= “seed”. This hypothesis, which was subsequently further developed by other scientists, assumes that the seeds of life arrived on earth from other planets. We see virtually the opposite picture in the mythology of Mesopotamia. The gods who had creative, solar characteristics, (Enki, Nerigal, Marduk, Dumuzi and so on) are linked to the Underworld:27 Of course these perceptions come from those fundamental phenomena which are to be seen in nature, such as:

The eruption of fire from the bowels of the Earth (volcanoes), The gushing out of freshwater from the bowels of the Earth (springs), The sprouting of seeds and emerging of shoots from the bowels of the Earth, The formation of human and animal foetuses and their emergence from the bowels

(womb). From these fundamental patterns, it was not difficult to deduce that life and the life-giving forces (water, fire) spring from the Underworld, the bowels of the Earth.

26 Nerigal’s dEr3-ra name form was written thus: = dARAD.RA, where =d (=div, dev, dig,

diq=”god” in armenian) is the “god” determinative. If we take the arda, urda, urdu, eru, eri3, war3 readings of

the ARAD cuneiform sign and also the rah reading of the RA sign, then we can have the following additional

appellations for the god Angeł=Nerigal:

dARAD.RA=darda/urda/urdu-ra=dArdar (ardar=the just)

dARAD.RA=deri3/eru-ra=dErir/Erur (eriwr=the creator, maker)

dARAD.RA=dEr3-rah=dErah (erah=the glorified)

dARAD.RA=dwar3-ra=dWar= God Var

This Var deity name can bear the meanings of each of the words var =“brilliant, burning, stinging” and var

=“arms and armour” because both of them correspond to the known character of the god Nerigal. 27 See: D. Katz, The Image of the Netherworld in the Sumerian Sources, CDL Press, 2003, concerning the

description of the Underworld and the gods living there.

19

In order to ensure the emanation process and the return route i.e. to ensure the Underworld-Earth link and interaction, our ancestors have also formulated the idea of gateways for entering and leaving the underworld. We will refer to the link between these gates and the image of the lion, below. The knowledge of these perceptions also helps us to understand the fact that in Armenia we come across large accumulations of rock carvings in actively volcanic locations with abundant water (the central mountainous mass of Syunik) and are not present in the absence of one or other of those two features (the lands surrounding Syunik: Artsakh, Utiq, and Gugarq which are also abundant in water but are not actively volcanic.) This fact in its turn testifies that the sculptors of the petroglyphs in Syunik were familiar with the above-mentioned perceptions of the bowels of the Earth. One of the future manifestations of these is the birth episode of Vahagn by Movses Khorenatsi:

The skies were in labour The earth was in labour,

And so was the crimson sea And in the sea a small red reed

Was also in labour

Vahagn was born from the Śirani Śov (Arun Śov) which is the sweet water Sea of the Underworld and corresponds to the Sumerian word zu-ab=şu2-ab=ծով(śov)=“subterranean sea of sweet waters.”

dEN.KI=dHaia=Hay God, the Egyptian creator God Atum and others were born from the primeval Sea in the same way. In the first lines of the book of Genesis in the Old Testament, God, beginning his acts of creation from the point of view of light, appears on a background of the Abyss (subterranean world) and waters. The author of the book of Genesis did not forget to include these in the act of creation but has omitted the episode of that God’s birth from the waters of the Abyss. Let us also remember that in the epic “Sasna Śrer”, Śovinar 28 becomes pregnant from the waters of the spring flowing from that Sea and gives birth to Sanasar and Bałdasar. Sanasar receives his fiery horse, weapon and armour from the shrine below the Sea and his strength multiplies from the waters of the spring in that shrine (compare: according to Sumerian sources, the palace of the Enki is located in the Sea (=zu-ab=şu2-ab) .

As far as the Ara Gełeşik legend is concerned, Khorenatsi (or his source), by re-

writing and ascribing the mythological subject to one of the Armenian patriarchs, presents

him with the corresponding characteristic of a mortal (the God descending into the

Underworld is presented as a mortal hero who is killed and buried in the abyss). There are

many such examples in the mythology of the ancient world.

We saw that the image of a lion was the ideogram for the Areg= “sun” component of

the deity name Areg Eregal/Erigal/Irigal=Areg Arageł. If we look at the deity name from the

28 . Śovinar is a deity name which is formed from (śovi), the genitive case form of the word śov=“sea” and the

word “nar”, which is identical to the Sumerian nir/ner/nur/nar3=“master”. Hence the name of the goddess

Śovinar literally means “mistress of the sea”. In Sumerian parallel to the reading of the cuneiform sign

NUN&NUN we can also reconstruct the ter=”master” reading: ne-er=de3-er=te4-er=der/ter=տեր(ter)=“master”.

This reading of ter is attested amongst the list of readings of the ŠENUN&NUN cuneiform sign.

20

point of view of pictography then we will also discover what character could be used in the

petroglyphs and subsequent pictography for the Aragel/Arageł component of the deity name.

Based on the principle of homonymity we can put the արագիլ(aragil)=“stork” bird name in

front of Aragel/Arageł, the deity name expressing an abstract meaning. Hence in order to

create the ideogram of the complete deity name Areg Arageł, the image of a stork must be

ligatured to the image of the lion. In order to make this pictogram more compact it is also

possible to ligature the wings of a stork to the lion, in which case we have the picture of a

winged lion.

Let us be satisfied with this much for now and turn to the God Nerigal’s Areg

Unugal=Areg Angeł name form. Here the word Angeł appears as the character of Areg, one

of the appellatives of the Sun God, Nerigal. Now our task is to etymologise the word

unugal(=underworld, grave)=angeł. We put the native Armenian polysemic word ankeł,

angeł=“fallen down, found below, finished, weakened, dead, bent, tilted, reached the edge,

extinguished, put out” which has the root “ang, ank”, in front of these. With the addition of a

word initial «հ» sound we have hang= “dwelling place, grave”. The Armenian root “ank, ang,

hang” bears those initial meanings from which we can derive the “underworld, grave”

meaning of the Sumerian word.

The “arew ank” expression in Armenian, which is the exact duplicate of the Sumerian

areg/w unugal, means “sunset”. Moreover, we have the word an-gi6, an-ge6=angi/ange in

Sumerian, which was used with the meaning of “eclipse (of the sun or the moon)” and

literally means “black sky” (sky(an)–black(gi6/ge6)).29 Of course this is the parallel to the

Armenian ank, ang, hang=“pass out, extinguish, fall down, set”. In ancient times the eclipse

of the sun or moon was perceived as their fall into the Underworld. Hence, the literal

meaning of the deity name Areg/Arew Angeł is “the sun god found in the underworld, in the

grave, below”.

Armenian allows us to give an additional interpretation of the deity name Angeł. In

this case we split the deity name into the “an” and “geł” components, the first of which we

consider to be the “an” negative prefix and we identify the second component with the

native Armenian root “gel/gil”. The noun glumn=“victory” and the verb glel=“win,

overcome, exceed, surpass” are from this. Therefore we can etymologise the deity name

Angeł as “invincible”, “unsurpassable”. In Sumerian mythology, this definition characterises

the god Nerigal. Later, during the Roman Empire, Miţra was called Deus Sol

invictus=unconquered Sun God. According to the interpretation above, this is the exact

duplication of the deity name dAreg Unugal=Unconquered God Areg/Sun.

Again we are faced with the ideographic problem of how to write the ideogram of the

deity name Areg/Arew Angeł; to be more precise, its Angeł component. I think that even

before the end of the question the reader who has the Armenian language thought processes

has already guessed that it can be done using the image of the vulture. And indeed the deity

name Angeł is homonymous with the bird name “angeł, angł, ankł”. Therefore we come to

the conclusion that we can ligature the “aryuś” and “angeł/angł” characters, in order to create

the ideogram of the deity name Areg/Arew Angeł.

29 . We think that the Armenian word gišer=”night” has the exact same structure: gi-šer= “black sky”. We find

the “sky” meaning of the word šer(n) in the word šernagoyn= “sky-colour” (cf. Hurrian še-er= “light, gleam”,

but the word *gi=”black” is unknown, and has probably been forgotten due to its briefness.

21

However strange it may seem, we even find this form of ideography of the deity name

Areg Angeł in late Christian pictography. As a striking example of this we point to the

Amenap‘rkiĉ (=All-Saviour) cross-stone which was engraved in the province of Urś30 and

then transported to the courtyard of Eǰmiaśin Cathedral.

The radiating sun’s disc which is pictured on the back of a vulture is in the upper left

corner of the cross-stone. The word ar-eg-akn=”sun” is engraved around these images and in

the weave of the ornamental designs; (the letters “A=Ա” and “R=Ր” are ligated). (see picture

10, first and second pictures).

Picture 10. The upper left corner of the Amenap‘rkiĉ cross-stone with the images of the

vulture and the sun’s disc and Aregakn=“sun” writing. On the right is a picture of one species of a

vulture.

The pictography of the sun’s disc+vulture accurately represents the ideogram of the

reading of Areg Angeł or Arew Angeł on this Christian cross-stone. This differs from that

discussed above in that the lion image is replaced by the equivalent sun’s disc. Therefore this

pictography of the Christian era first shows the existence of the continuing tradition of using

the image of the vulture to represent the ideogram of the deity name Angeł and proves that

1000 years after the adoption of Christianity, the Armenians still preserved the memory of

their old gods. That memory is not attested to in Mesropian literature, for understandable

reasons, but it is abundantly presented in the pictography of the Christian era. We will

become convinced of that during examination of every glyph coming from the petroglyphs

of Syunik.

Let us add that in the upper right corner of the All-Saviour cross-stone the moon is

pictured but this time on the back of a bull. We will touch on this when we examine

ideography using the bull image.

The description of Tork Angeł given by Movses Khorenatsi states that he whittled

planks from quartz stones with his nails and drew “eagles and similar things” 31 on them; this

is also a direct attestation of the existence of ideograms with the image of vultures on them.

Of course the image of the vulture must also be taken into account in the expression “eagles

and similar things” and Tork’s Angeł nickname must be interpreted by the Angeł deity name

ideographed with the image of a vulture, and not the word angeł=”ugly”, as Khorenatsi

states.

If we summarize what has been stated above, then we will have the following picture:

30 . We express our gratitude to Grigor Brutyan for the provision of the photograph of the cross-stone. 31 . Movses Khorenatsi, History of the Armenians, B.8

22

a. In order to ideograph the word Havari=“Mother river” it is necessary to ligate the

characters meaning “lion” and general “bird”.

b. In order to ideograph the deity name Areg Arageł it is necessary to ligate the

characters for “lion” and “stork”.

c In order to ideograph the deity name Areg Angeł it is necessary to ligate the glyphs

for “lion” and “vulture”. Henceforth we will call this picture angłaryuś=vulture-lion.

In all three cases a bird image is ligated to the lion image and the simplest version of

ligation is that the winged lion be pictured. As a result we come to the widespread

mythological animal in ancient world pictography – the image of the winged lion.32

Above, we discovered how and in what linguistic environment that picture would

arise. The other important problem is to discover where and when it originated. As was

expected (at least by me) we find the oldest images of the winged lion on the petroglyphs of

Syunik (see picture 11).

Picture 11. Images of winged lions in the petroglyphs of Syunik

In the first of the pictures presented, the winged lions are pictured in pairs (Areg

Angeł and Areg Arageł ?), and in the second picture the winged lion is ligated with the

ket=“point” glyph. We must read the latter homonymously Hawari get = “mother river, river

of the bowels of the earth”, the parallel of which as we mentioned above, is the Sumerian

writing ID2Hu-bu-ur=ID2Hubur=”mother river of the bowels of the earth”.

Therefore we can say that the get=“river” determinative ligated to the image of the

winged lion makes it possible to differentiate the readings of “havari” and “Areg Angeł”. In

the first case the “ket” character, the wavelike sign of water or the character “spring”, and in

Picture 12. Pictures of the winged lion from Western Asia (III-I millennia BC).

32 . In specialized literature the image of the winged lion is called the griffon, (gryphon, griffin) and they ascribe

its wings not to the vulture, but to the eagle. Experts base the interpretation of this picture on the imaginary

idea that since the eagle is the king of the birds and the lion, that of the beasts, then the picture of the winged

lion must express the idea of regal authority and strength, which of course is a spurious interpretation.

23

the second case, the determinative meaning “sun” or “underworld, bowel” (we will touch

upon these, as yet unfamiliar to us, glyphs in loci).

After the Armenian Highland’s Sunik petroglyphs we see the vulture-lion image at

the beginning of the historical period in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Palestine, and Asia Minor (see

Picture 12). They represented the God Areg Angeł=Nerigal.

Some time later (end II millenium – beginning I millenium BC) the vulture-lion

image spread from the Balkans up to the Indian peninsula and then to China (see Picture 13).

Of course in all these cases when the vulture-lion image appeared in foreign language

environments it lost its ideographic character and was perceived merely as a character and

was ascribed to any deity with a solar nature in the given pantheon.

Picture 13. Images of winged lions. Left to right: Greece, Iran, India, China.

Without doubt the image of the vulture-lion continued to be used as the ideogram for

the name of the God Areg Angeł in Armenia, i.e. in its native language environment. This is

attested by the numerous ancient materials with pictures of the vulture-lion belonging to the

Hurro-Urartian culture (III–I millennia BC) (see picture 14).

Picture 14. Pictures of vulture-lions from the Hurro-Urartian culture.

Picture 15. Section of the seal of

King Šuttarna II of Mitanni

( XIV century BC).

Moreover we learn from Hittite inscriptions that

the god dU.GUR=Nerigal=Areg Angeł was the supreme

God33 in the country of Hayasa (a state in the territory of

High Hayq XVI-XIII centuries BC). At that time, ligation

of the complete images of the lion and vulture can still be

seen (see picture 15):

33 . Г. Капанцян, Хайаса колыбкль армян, Историко-лингвистические работы, Ереван, 1956

24

The archaeological material of the Urartian period is also rich in pictures of the

vulture-lion. In addition, the vulture-lion was pictured with the head of a lion, vulture or

man. (See: picture 14, second row).

In the post-Urartian period, the God Mitra is a striking character bearing the image of

the vulture-lion. The only information that has reached us concerning this god, through the

literature of the Christian period, is the name Mihr and the fact that Mihr was the son of the

father of the Gods, Aramazd, the God of the Heavens.34 If, outside Armenia, Mihr=Miţra is

identified with Helios, Apollo or Hermes, then in Armenian literature Mihr has always been

identified with Hephaestus, the embodiment of the heavenly fire.35 We also see testimony to

that effect from the work of Philo of Alexandria (25BC to 50AD), which is preserved in the

Armenian translation.36

Picture 16. Lion-headed and vulture-winged Miţra (marble high-relief from Rome), statue of

Mars (First century, in the Capitoline museum) and its breast piece on which there is the image

of a pair of vulture-lions.

If we also take into account that Mihr=Miţra was worshipped as the god of fire and

sun and has frequently been pictured with a lion’s head and vulture’s wings, then it is

obvious that the worship of Mihr=Miţra is one manifestation of the worship of the god

Nerigal= Areg Angeł. On the breast of the Roman God of war Mars we see a pair of vulture-

lions which also exist in the petroglyphs of Syunik. In the Sumero-Babylonian period, this

was also Nerigal’s function and in pre-Christian Armenia, the god Vahagn was the parallel to

Mars/Ares. We will refer to the Mihr=Miţra and Vahagn and Nerigal link and manifestations

of worship in detail in the work “Hayots Astvaś(The God of Armenians)”. And here let us

take one more diversion and briefly stop at the misunderstanding that supposedly the name

and worship of the Armenian Mihr and the Roman Miţra are derived from the Indo-Iranian

Miţra.

34 . Agaţangełos: History of the Armenians, (In Armenian), Yerevan, 1983 pp. 444-445 35 . Ł. Ališan: Ancient belief or pagan religion of the Armenians, (In Armenian)Yerevan 2002 p.146; M.

Abełyan: Works, V.I (In Armenian), Yerevan 1966, p. 75 36 . Н. О. Эмин, Вахагн-Вишапаках армянской мифологии есть Индра-Vritrahan Риг-Велы, Исследования

и статьи Н.О. Эмина, Москва, 1886, ст. 81

25

INTERPOLATION IV (Bag- Angeł -Mihr-Nerigal)

In the Sumerian list of gods (Ananum Tablet) of the first half of the III millennium

BC, the dPAmi-it-ra-šu-U.GUD deity name is put in front of the dUD ideographic writing of

the Sun God (Ananum Tablet 3 104). In another early Babylonian list of gods (An;anu ša2 ameli) we learn, as was noted above, that the deity name dPA is one of the names of the god Nerigal (An;anu ša2 ameli 85): First let us refer to the U.GUD component of the above-mentioned deity name, which

is a ligature cuneiform sign, has arisen from the character and has the readings of ul ulu, mul

,

4 , of which mul4=“to gleam, to radiate, star” and is the parallel of the Armenian root, mul=“twinkling light, fire” which when repeated gives us mlmlal=“to glitter, to iridesce, to twinkle”. For the ul, ulu reading of the cuneiform sign, Armenian has the word ułp‘= “abundant light.” Therefore for the šu-U.GUD component of the deity name we will have the reading of šu-ul=šul. And since it refers to the name of the Sun god, then it is logical to identify the word šul with the Armenian word šoł= “sun’s ray, reflection, luminous, shiny, hot”.37

The form of the first component of the deity name (PAmi-it-ra) shows that it is

necessary to take the mi-it-ra=mitra reading for the PA ideogram. Here the it/id syllable is the reading of the A2 cuneiform sign, which also has the readings of ah5, ahi2 . Therefore we can also present the mi-ah5-ra=mihra>mihr=Mihr form for the deity name.

Consequently dPAmi-it-ra-šu-ul=Mihrašoł/Mitrašoł God and this deity name was