Language shift and endangerment in urban and rural East Africa: 3 case studies

Transcript of Language shift and endangerment in urban and rural East Africa: 3 case studies

Language shi+ and endangerment in urban and rural East Africa:

3 case studies

Maik Gibson Redcliffe College & SIL Interna9onal

Bagamba Araali SIL Interna9onal

The three contexts

Nairobi (Gibson 2012) ShiE in informal urban seHlements compared with formally seHled areas.

Bunia, DRC (Bagamba & Gibson) Urban shiE among one of the larger communi9es, Badha-‐speaking Hema.

Bhele community of DRC (Bagamba) ShiE in a small rural community.

In each case the target of shiE is a variety of Swahili (not an ethnically-‐marked language in these contexts).

Nairobi: a mel9ng pot or a salad bowl?

African ci9es -‐ sites of recently developed and dynamic language ecologies.

They can be both sites of language shiE and language maintenance, with Mufwene sugges9ng that at least parts may be seen as “mega-‐villages” (eg 2010:915), with a mix of rural and urban dynamics – a salad bowl.

PaHerns of norma9ve mul9lingualism complicate the analysis of language shiE

Nairobi Suburbs, dominant language at home (Gibson 2012)

Note that figures do not claim to be representa9ve of wider popula9on, beyond a widespread shiE to Swahili.

“Mother Tongue” 3 7%

Swahili 37 80%

Swahili & English 2 4%

English 4 9%

Kibera, dominant language at home

• We note a marked difference from the Northern suburbs.

• Only home domain shows strong MT reten9on

“Mother Tongue” 109 70%

Swahili & MT 18 12%

Swahili 28 18%

Intergenera9onal Transmission (Kibera)

Child to Child

“Mother Tongue” 14 18% Swahili and MT 9 12% Swahili 54 70%

Parent to Child

“Mother Tongue” 11 31%

Swahili and MT 6 17%

Swahili 15 43%

English 3 9%

Language use by age of arrival in Kibera

0-9 10-19 20+

Luos 83% (n=12)

67% (n=12)

89% (n=18)

Other groups

29% (n=7)

77% (n=13)

71% (n=14)

Bunia (Bagamba & Gibson)

Ongoing work – part of larger project Rapid urbaniza9on increased by civil conflict Metaphors – Mel9ng pot (shiE to LWC) Salad bowl (widespread maintenance) Spice pot? (assimila9on to locally dominant vernacular)

Focused on one community – Northern Hema, speaking Badha (=Lendu -‐ not originally their ethnic language)

Not self repor9ng, but assessment of abili9es of children, along with interview of parents, by a Badha speaker.

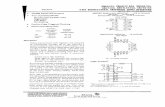

Competence of Northern Hema children in Bunia in Badha

5-‐9 year old(N=59) 10-‐13 year old (N=51)

14-‐18 year old (N=37)

63%

27% 19%

27%

55%

38%

10% 18%

43%

Doesn't understand Badha

Understands but does not speak Badha

Speaks Badha perfectly

Children’s Iden9ty Percep9ons

Inhabitant of Bunia Northern Hema living in Bunia

Northern Hema

74%

7% 20%

61%

8%

31%

45%

11%

45%

5-‐9 year old (N= 61) 10-‐13 year old (N=51)

14-‐18 year old (N=38)

Parents’ language use paHerns, Bunia

Swahili Badha Swahili and Badha

Other combina9ons

59%

20% 17%

4%

59%

21% 18%

2%

18%

44%

27%

11%

Father to children Mother to children Between parents

Other studies

Trends similar to the Northern Hema case were observed among the Alur in Bunia (Bagamba and Ucuon 2012) – another large community in the town

Also among the Tembo people in Goma (Bagamba and Masumbo 2013) – a small community in a larger city.

Bhele (Bagamba)

Sample taken from the four more accessible clans (of six), in rural homeland.

Group oEen present selves as Nande when outside homeland.

Exogamy of around 40% (half with Nande)

ShiE oEen to Nande-‐Swahili bilingualism

Interviews with parents showed that neither Bhele iden9ty or language perceived as useful

Bhele children’s competence in Bhele

Doesn't understand

Understands but don't speak

Speaks but not well

Speaks fluently

25%

35% 27%

13% 9%

14% 16%

56%

Aged 06-‐13 Aged 14-‐20

A Final Ques9on

We raise the ques9on of whether this rural shiE to Swahili (a language which is not perceived as belonging to one par9cular ethnic group) is facilitated by its widespread use in urban contexts. As such, we must ask the broader ques9on of how the dynamics of urban language ecologies in Africa impact those in the countryside.

References

Gibson, Maik (2012) “Language shiE in Nairobi”. In MaHhias Brenzinger and Anne-‐Maria Fehn (eds.), Proceedings of the 6th World Congress of African Linguis'cs, Cologne, Germany, 17–21 August 2009. 569-‐575. Cologne: Koeppe Verlag.

Mufwene, Salikoko (2010) “The role of mother-‐tongue schooling in eradica9ng poverty: A response to Language and poverty” Language 86:4. 910-‐932.

Ucoun, Combe. 2012. “Transmission des langues maternelles en milieu urbain : cas de Dhu-‐Alur à Bunia”. ISP-‐Bunia, unpublished licence disserta9on