International Journal of Heritage Studies Sustainable architectural conservation according to...

Transcript of International Journal of Heritage Studies Sustainable architectural conservation according to...

This article was downloaded by: [Khalfan Khalfan]On: 18 November 2011, At: 07:53Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

International Journal of HeritageStudiesPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjhs20

Sustainable architectural conservationaccording to traditions of Islamic waqf:the World Heritage–listed Stone Townof ZanzibarKhalfan Amour Khalfan a & Nobuyuki Ogura ba Graduate School of Engineering and Science, University of theRyukyus, Japanb Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture, University ofthe Ryukyus, Japan

Available online: 04 Oct 2011

To cite this article: Khalfan Amour Khalfan & Nobuyuki Ogura (2011): Sustainable architecturalconservation according to traditions of Islamic waqf: the World Heritage–listed Stone Town ofZanzibar, International Journal of Heritage Studies, DOI:10.1080/13527258.2011.607175

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.607175

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representationthat the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of anyinstructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primarysources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,

demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

Sustainable architectural conservation according to traditions ofIslamic waqf: the World Heritage–listed Stone Town of Zanzibar

Khalfan Amour Khalfana* and Nobuyuki Ogurab

aGraduate School of Engineering and Science, University of the Ryukyus, Japan;bDepartment of Civil Engineering and Architecture, University of the Ryukyus, Japan

(Received 6 March 2011; final version received 19 July 2011)

Sustainability in the conservation of architectural heritage is now more exten-sively considered than it was decades ago. The introduction of the concept ofsustainability to the field marked hopes to overcome problems threatening heri-tage sites. There are general concepts guiding sustainable conservation. How-ever, heritage specifics play important roles in achieving sustainability, and maydirect the formulation of sustainable concepts to be applied. This paper is anattempt to add to the discourse of heritage sustainability by discussing buildingsmanaged through a tradition of Islamic waqf in the World Heritage Stone Townof Zanzibar. It examines sustainability in terms of its financial, social,managerial, and environmental aspects. The relatively good survival rate of waqfbuildings in the old town over several centuries suggests sustainable and trans-missible ‘genes’ within the tradition. Waqf was found to elaborate ways to strikea balance between heritage consumption and use, avoiding gentrification, andenabling collective urban conservation. It further suggests that sustainableconservation cannot avoid monetary sacrifices, and if it is to be sustainable inthe long term it should be inherent in the heritage itself.

Keywords: architectural conservation; Islamic waqf; sustainable ideas; WorldHeritage; Zanzibar Stone Town

Introduction

The concept of sustainable conservation is relatively new when speaking of the builtenvironment. It first reached the field of architectural heritage at the UN-HABITATConference of Vancouver in 1976, but it was not until 1996 that the Istanbul Declara-tion and Habitat Agenda introduced the notion into the field’s policy documents.Since its first appearance in the architectural heritage field several approachesemerged in response to the envisaged sustainability, which includes architectural recy-cling, historic conversion and adaptive re-use. Nevertheless, these approaches are notwithout pitfalls. Conversion and re-use often involve commercial means that seekimmediate economic returns. In many countries, they have created irreversiblechanges to heritage places, in terms of both their physical character and their socialstructure (Marks 1996). These approaches are likely to cause more harm to the

*Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

International Journal of Heritage StudiesAquatic InsectsiFirst article, 2011, 1–17

ISSN 1352-7258 print/ISSN 1470-3610 online� 2011 Taylor & Francishttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2011.607175http://www.tandfonline.com

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

heritage of developing countries, where financial resources are scarce (Khalfan andOgura 2010).

Recent trends in sustainable conservation focus on the ways in which negativeeffects of conservation activities could greatly be minimised, and how such activi-ties are sustained. Sustainability in heritage sites is, however, a complex issue thatdepends on a number of factors, some of which are situational and system depen-dent.1 This suggests a number of approaches might be needed to suit particular cir-cumstances to supplement common practices. In a study of Palestine waqf, anIslamic endowment tradition, Assi (2008) points out that this tradition may possessuseful attributes for sustainable heritage management. However, as yet insufficientdetail on waqf sustainability, and the way it may enhance our understanding of sus-tainable heritage conservation, taking into account issues other than financial pros-pects of the waqf, has emerged. Therefore, this paper focuses on qualifying thewaqf tradition and its relevance to the sustainable conservation of built heritage. Toachieve this aim, the waqf institution in the World Heritage Stone Town of Zanzibar(STZ), located in Tanzania, East Africa, was studied between August and Septem-ber 2010.

The presence of waqf in this town can be traced back to the fifteenth century.2

The waqf has played, and continues to play, an important role in the social, culturaland economic life of the town’s inhabitants, as well as Zanzibar Island in general.Nonetheless, very little is known about the conservation potentials of this institution.Several studies on the waqf have concentrated on its social welfare aspects (Bang2002, Yahya 2008). Others have dwelt on the structure of the waqf institution, itsscholars (Bang 2000), and external influences that transformed its practice (Oberauer2008). The long-term survival of waqf buildings in relation to its traditions has notreceived much attention. According to the present Waqf and Trust Commission(WTC), about 20% of existing historic buildings in the town belong to waqf. Withthis building stock and period of operation, it is possible that the waqf traditionembodies sustainable conservation practices that this paper intends to elaborate.

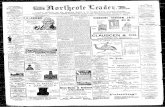

Research methodology

The study was accomplished through a research of waqf practice in STZ. Overtime, as in some other Islamic countries, waqf rudiments in the STZ have remainedalmost the same as those of other countries. However, its practice was shaped bycolonization, schools of Islamic law known as madh’heb or sects,3 as well as effectsof changing the country’s governing system. The waqf in the town passed throughthree major periods of economic, political and social change (Figure 1) whichimpacted on practice. The first period is from its introduction and consolidation(around the fifteenth century to the third quarter of the nineteenth century). The sec-ond is the time of British colonial administration (1890–1963). The third and lastperiod is after the revolution, when independent government was achieved (1964 tothe present). Therefore, at the outset of this research, it became apparent that anappropriate time period in the history of waqf, as well as a school of law needed tobe chosen, to get the best representation of the theoretical and actual practice of thewaqf in the town.

Waqf practice was very traditional during the first period, but little is knownabout the practice in that time due to the meagre information that remains. So, thefirst period is not suitable for our purposes. The second period, when waqf activities

2 K.A. Khalfan and N. Ogura

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

were well documented and for which records are retained in the Zanzibar NationalArchives (ZNA), is the focus of this study. Although the waqf was appropriatedand influenced by the British colonial policy, during this period its rudiments werestressed and tested by a series of decrees enacted by the British (Figure 1) aimed atcontrolling the waqf institution (Oberauer 2008).4 This period also offers a compre-hensive understanding of waqf in their traditional setting, as well as when they areunder stress. The third period is less useful for this study; although similar in prac-tice to the second period, this period saw less challenges to the waqf then the sec-ond period. The second period therefore offers the potential for far more interestinginsights for our purposes.

The research ventured into the archival records of the ZNA, featuring the Britishwaqf administration, which forms a major part of the discussion in this paper. Some32 files were examined from the archives.5 The analysis contains qualitative andquantitative data from waqf deeds, rent records, waqf decrees, waqf registers, jurists’rulings, daily correspondence, and minutes of the British Waqf Commission (WC).

The research also ventured into confidential files of the administration to unveilclassified waqf information. Most of the archival records are in English, exceptwhen Arabs are involved, in which case their English translation was often pro-vided. The archives were eventually supplemented with field observations of thetown’s waqf and private buildings, along with targeted questioning of some of theiroccupants. Private properties were involved to provide insight into certain aspectsof waqf buildings and their sustainability, in contrast to that of private owners.

Meaning, purpose and conservation aspects of waqf

Waqf (plural awqaf) may be explained as an endowment of a property carried outvoluntarily by individuals as everlasting charity, which once endowed is subject toreligious rules. According to the rules, waqf properties are eternal. They cannot besold, mortgaged, gifted or inherited (see waqf deed in Box 1). Endowing waqf issaid to be an original Islamic tradition dating back 1,400 years (Hennigan 2004).

WPD No.1

WPD No.2

NPWD No.2

WPD*

No.15WPD No.1

WPD*

No.16WPD*

No.16WPD*

No.16WPD No.21

WVD No.5

WPD WVD*

No.5WPD*

PD No.12PD

No.12

WPD No.7

W&

TPD

W&

TPDA

1700

<1700

1800

1817 1840 1890

1900

1904 1905 19071892 1909 1916 1920 1921 1922 1927 1946 1951 1959 1965 1966 1967 1980 2007 2011

2000

1912

1914

1940

1949

1945

1952

1961

1964

1904

1890

1993

2011

26 m

osqu

es in

STZ

und

er W

C

Oldest mosquebuilt in STZ

Date of one Al-Mafazi

tomb in STZ

Oldest w aqf deed found

in ZNA British rule

Order to handover w aqf properties to BA

Waqf under RGZTraditional w aqf practice

36 m

osqu

es in

STZ

und

er W

C

128

hous

es u

nder

WC

; 109

in S

TZ

158

hous

esun

der

WC

inST

Z&

19pr

oper

ites

of u

nkno

wn

dedi

catio

ns

165

hous

es,1

10sh

amba

sun

der

WC

& 31

mos

ques

in S

TZ

135

hous

esin

STZ;

52fa

mily

awqa

f&

74 d

edic

ated

to m

osqu

es

175

hous

esin

STZ

unde

rW

C;1

36fa

mily

dedi

catio

ns&

39de

dica

ted

tom

osqu

es

WC established

1980

WTC established

351

build

ings

&35

mos

ques

unde

rW

TCin

STZ

358

build

ings

ofw

hich

35ar

em

osqu

es u

nder

WTC

in S

TZ *

*

British Waqf Administration

Notes: BA = British Administration; NWPD = New Waqf Property Decree; PD = Property Decree; RGZ = Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar; STZ = Stone Tow n of Zanzibar; W & TPD = Waqf and Trust Property Decree; W & TPDA = Waqf and Trust Property Decree Act; WC = Waqf Commission; WPD = Waqf Property Decree; WTC = Waqf and Trust Commission; * = Revised Version of a Decree; **- w aqf buildings ˜ 1/5 of all buildings in the STZ.Sources of data: Zanzibar National Archives f iles: AB 22/8, AB 34/1, HD 4/67, HD 10/7, HD 10/37, HD 10/53, HD 10/85; Sheriff (1999); Stone Tow n Conservation & Development Authority; Waqf & Trust Commission; Valuation list for the Tow n of Zanzibar, 2nd March, 1914, Zanzibar Government Printing Press.

waqfdecree

TIMELINE

miles-tones

waqf proper-

ties

Figure 1. Historical development of Islamic waqf in STZ (source: the authors).

International Journal of Heritage Studies 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

Muslim scholars trace waqf origins from the traditions of their Prophet.6 The Pro-phet is reported to have advised one of his future caliphs to endow as waqf a pieceof land and distribute its income to the poor, but to ensure what can be describedas the preservation of the property, presumably for a very long period of time.

Box 1. Sample of a typical waqf deed (source: ZNA, Deed No. 304, 18 January1937).

. . . [Name] dedicates as waqf his shamba[land] at . . . which is bounded onthe North by. . ., on the South by. . ., on the West by. . ., and on the East by. . ..The shamba contains . . . [number] trees including the house built of . . .[structural material] and covered with . . . [roofing material]. The shambatogether with their boundaries, rights and whatever is connected therewith arean accomplished waqf in favor of his . . . [first beneficiaries’ name] and theirchildren and grand children and their posterities, one generation after anotherand that the first generation is entitled to enjoy the waqf before the secondone and so forth . . ., it is for the benefit of poor, the children of his paternaluncles and aunts . . . should be continued in all the generations and on theirdeath it is for the benefit of poor Moslem of . . . tribe . . . who have to enjoythe income of the waqf and also to live therein after making provision of theupkeep of the property so that it should remain in good condition until on theresurrection day. The dedicator has appointed himself as a trustee during hislife time and after him, his executors . . . until the waqf revert to poorMoslems of . . .tribe when the General Trustee should be a trustee. The execu-tors are entitled to 10% out of the income of the waqf during their life timebeing their remuneration. It is a valid waqf and lawful and which is neither tobe sold, mortgaged, gifted nor inherited until God inherits the Earth. . .. Datedthis day of . . . Name and signature of dedicator . . . Witnessed by . . .

The fundamental idea behind waqf practice is therefore to endow property thatgenerates income to serve a social function, and in turn maintains the property.Through this idea, a continuous financial arrangement is set in place which is sup-posed to be sustainable as long as the practice is properly carried out. Islamic coun-tries still have properties maintained through the waqf system, althoughmismanagement and corruption in some of these countries render the system lesseffective (Assi 2008). Building maintenance in the city of Kashan in Iran is oneexample of a good waqf practice (Jokilehto 1999). Since existing buildings arepotentially future heritages they do benefit from such a system. Their chance of sur-vival is enhanced by the maintenance and care provided under the waqf system.Also, as waqf is a long-term arrangement, it can continue to provide maintenanceand support as the buildings become older, and eventually may be seen as a legacyof the past. By maintaining these buildings, waqf performs an important task ofarchitectural conservation. It is through this task that waqf may be regarded as a tra-dition with inherent qualities that foster conservation.7

A person who dedicates property to waqf is known as waqif, and those whobenefit from the waqf are called montase’. The waqif has a mandate to choose amutawalli (waqf manager), who will administer the waqf according to stipulationsmade by him or her and laid down in a waqf deed (Box 1). The mutawalli is

4 K.A. Khalfan and N. Ogura

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

remunerated from the share of income derived from the property, often set as apercentage of income earned at an instance. His or her duty is to ensure that maxi-mum revenue is derived from the waqf. They are also responsible for distributingthe revenue to the montase’, and ensuring the property is well maintained. Sincewaqf properties are dedicated by private individuals who decide the managementsetup, they were traditionally kept under separate mutawalli. However, as the waqfinstitution becomes incorporated with secular states, awqaf are collectively keptunder a unit of a state division. In Zanzibar’s case, for example, awqaf were admin-istered by the British WC during British colonial rule. Currently, they are under aWaqf and Trust Commission (WTC), which includes trust properties in addition tothose designated waqf. Some Islamic countries have a special ministry that takescare of awqaf. In either case, the mutawalli’s duties are transferred to the newadministration, but the deeds continue to govern the waqf.

STZ waqf involves mainly land and buildings. The oldest surviving waqf struc-ture in the town is a mosque dating back to the seventeenth century (Sheriff 1999).Waqf became a common practice in the town, and by the beginning of thenineteenth century it controlled a substantial part of the urban space of the STZ(Oberauer 2008). Of the 1,700 heritage buildings in the town, over 350 are ownedby waqf institution, according to the latest records of the WTC. Other buildings areowned by government and private individuals. Although this number might looksmall in relation to the town’s building stock, the role played by waqf buildingscannot be dismissed as negligible, particularly when they are thought of in terms ofthe accommodation they provide to a large section of poor inhabitants in the town.However, what is more important to our argument is its conservation efficiency vis-à-vis other forms of building ownership. Waqf-administered properties have success-fully housed more of the poorest population of the town than other owners, andhave conserved its stone and mud buildings without much compromise of theirform and structural integrity.8

Sustainable conservation ideas in waqf

Islamic waqf, as a practice involving aspects of conservation of buildings, has sev-eral ideas that might be useful, especially with regards to the concept of sustainabil-ity in built heritage sites. These ideas are apparent from both its theory and practicein the town. The following section discusses some important ideas.

Inherent conservation

Many of the conservation approaches available today are rather ad hoc remedies tosave obsolete building stocks, or those deemed worthy as heritage. Theseapproaches arise as a result of the urgent need for conservation, and are often asso-ciated with effects that are sometimes irreversible to those buildings. One of thereasons is that they are immediate and non-intrinsic. According to waqf ideas, con-servation of built heritage might be sustainable if its planning is thought of well inadvance. In other words, it is made inherent in the system that controls heritage, orin the item heritage itself.

Waqf elaborates inherent conservation (IC) through its system. The inherent sus-tainability is structured under a three-tier interdependent gyrating system (Figure 2).Financial income is central to the system. The property (P) generates income (E), of

International Journal of Heritage Studies 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

which part is used to support the waqf beneficiaries (B) and the remaining reservedfor the property maintenance (M) to ensure it stays intact. Maintaining propertyfrom the share of income is therefore inherent in its traditions. Waqf is usuallyendowed to benefit certain social functions. So, the establishment of a waqf prop-erty depends on a social demand. Hence, absence of social demands would meanabsence of waqf. Similarly, if the property maintenance is not carried out the prop-erty may not yield enough income. The interdependence of the 3 system compo-nents (P, B, and M) is what keeps the waqf system sustainable and in equilibrium.

Income has a significant effect on the overall system. Nonetheless, it is not thesole factor of waqf sustainability. The property is paramount, because if it is discon-nected from the system there is no finance, waqf or conservation. Securing theproperty is therefore the most important issue in sustaining waqf. This study hasfound several qualities possessed by waqf that help to achieve this. Some of themspring directly from the basics of its traditions, while others are the results of philo-sophical interpretations of its rudiments by schools of Islamic thought. The rules ofwaqf require that building properties dedicated as waqf should be on lands that arealso waqf,9 since a waqf, whether it is land or a building, is governed by the eter-nity rule. This is simply because a waqf building set on a non-waqf land may bemore easily removed than a waqf building which is built on waqf land, even thoughthe land and the building are dedicated by different persons. The deed in Box 1shows the waqf should explicitly state that its property is neither sold, mortgaged,gifted, nor inherited. Such clear stipulations indicate the intention of perpetual reten-tion of a property as waqf, which its dedicator considered before making their dedi-cation, and should be considered inherent in the system.

Tsunoda et al. (2007) provide an example of IC conceived from a planningpoint of view during a design for the re-use of a World Expo building at Aichi,Japan. Expo buildings are largely temporary structures, their purpose finished withat the end of the expo show. Contemporary expos may last for 6 months, accordingto Tsunoda et al. (2007). The recent Chinese showcase expo at Shanghai lastedonly five months.10 At the end of the expo, most expo buildings are demolished orabandoned. However, the Aichi Expo 2005 in Japan was an exception. It carefullyconsidered the re-use of its components during the planning stage. Furniture andother equipment were recycled, while its pavilion was converted into a forest centre.The relevance of the message that comes out of this expo project is not its conver-sion, and perhaps consequently property alienation, which is not consonant withwaqf ideology;11 rather the idea of advance planning for such a conversion, whichleads to re-use and conservation, is inherent.

The strength and success of an IC may differ from one building type to another,despite the buildings belonging to the same owner. For example, in the waqf case,mosques are inherently the most-preserved structures, not only in STZ, but almost

B

M P

E

B = beneficiaries P = property E = income M = maintenance

Figure 2. The three-tier system of waqf sustainability (source: the authors).

6 K.A. Khalfan and N. Ogura

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

everywhere in Islamic cultures. This is because they are central to the culture, andtheir use is frequent and often continuous over long time-periods. Mosques are usedfor prayers as many as five times a day. Even mosques in deserted areas are notdemolished, as passersby may still use them. A survey of the town revealed all ofthe 51 mosques are in use, and their cumulative number has to date remained thesame.

Mosques, as objects of Islamic rituals, are morally subjected to very tight rules,and once erected cannot be demolished, unless they are replaced. One apparentexample signifying this phenomenon is that of the nineteenth-century Mabluu Mos-que in the town’s buffer zone, which was demolished in the 1930s following a roadexpansion project. The mosque was reconstructed by the Zanzibar government inthe 1990s, after almost six decades of criticism from the Muslim community, whoargued that its demolition was an immoral mistake, and the country would notreceive God’s blessings if the mosque was not re-established. Mosques in Islamicsocieties do have conservation protection, so that their form and function havehardly changed. This is, however, contrary to some other religious edifices that maybe converted and adopted. In England for example, Douglas (2006) reports that theconversion of vacant religious buildings into workshops and light industries iscommon. This suggests similar building types by different owners may not beinherently conserved.

Sustainability through mutual benefit

The next idea emerges out of the fact that waqf is used to perform several functionsat the same time. It works on the principle that a property such as a building isdedicated to at least one basic and one implied purpose. As previously discussed,the basic form is to finance a social function (Figure 3a) in addition to the upkeepof the property that generates the finance.

P

BS

M

P

BP

M

P

BS

M

BP

P

P

M

BP

BS

BP

P

P

M

(a) (b) (c) (d)

(e)

Key:Income flow

Maintenance link

Income and maintenance links M = maintenance of property P = property set waqf BP = beneficiary as other property BS = beneficiary as social function

Figure 3. The various forms of income generation and maintenance pursuit in Islamic waqf(source: the authors).

International Journal of Heritage Studies 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

The relationship between the property and the function is therefore analogous toa symbiosis that exists between a host and a symbiote with property maintenanceincluded as a prerequisite. Nevertheless, as the waqf in the STZ evolved, the basicform was extended from one to many relationships. Several other combinationswere derived from the basic model as evident from waqf deeds. They include: aproperty sustaining another property that hosts a social function (Figure 3b) such aspublic facilities; a property sustaining a social function and one or more other prop-erties (Figure 3c); a number of properties supporting single beneficiary property(Figure 3d); and a number of properties sustaining a social function and one ormore other properties (Figure 3e).

This system therefore creates mutual conservation benefits. The properties thatreceive the income are conserved, along with those which generate the income. Ifthe conservation of the ‘host’ property is sustainable, the sustainability is alsoachieved by the ‘parasites’. Nevertheless, in a similar way the ‘parasites’ areaffected when the ‘host’ is unsustainable.

The records of the WC exemplify this, though they are not limited to it, as inthe case of mosques. The records show that some of the mosques receive theirshare of maintenance from the income of various buildings. Some 16 mosquesunder the waqf commission in the 1940s were maintained by at least two propertieseach.12 Two of the mosques were highly endowed (Figure 4), one with 13 andanother with 14 buildings for their upkeep. Survey showed the two mosques areamong the healthiest in the town. The former was endowed by a member of theSultan’s family, while the later belongs to the Hujjat Islam Jamaat, one of theIndian Shia Muslim communities in the STZ. The properties of the latter were con-tributed to by several Jamaat members.13 Although some of the mosques were bet-ter endowed than others, waqf practice allowed the rich ones to share theirincome14 and several mosques in the town were found to subsidise the poorlyendowed ones.15 This scenario represents a form of cross-financing that itself is away to achieve sustainable conservation through mutual benefit between waqf prop-erties of utterly different dedicators.

Further, through such finance it was possible to conserve several buildings thathost a variety of cultures. There are waqf buildings belonging to Arabs, Indians,Commorians, and native Swahilis, each of which displays the cultural elements of

Figure 4. Religious buildings dedicated by Seyyid Hamoud (left) and to Hujjat IslamJamaat (right). These buildings represent the two dominant cultures of STZ that contributedto the recognition of the town as a World Heritage Site (source: the authors).

8 K.A. Khalfan and N. Ogura

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

its origin, while some blend the different cultures to create an architecturalamalgam, which Sheriff (2001) describes as unique. The cultural mix and thearchitecture were highly influential during the nomination of the town as a WorldHeritage Site. According to UNESCO, of the three criteria used to nominate and listthe town in the World Heritage List, two of them were related to its cultural andarchitectural characteristics.16

Social sustainability

One of the most widely discussed and hard-to-solve issues in the world of conser-vation today is that of social sustainability of heritage sites. Social sustainabilityinvolves retaining people along with heritage to allow them to contribute to the cul-tural landscape of an historic area. Gentrification is to blame in some cases forpushing people out of these areas.17 It has become almost impossible to avoid gen-trification in historic towns and cities driven by economic revitalization, with poorinhabitants being the most vulnerable (Ergun 2004). Marks (1996) explains how thepoor in STZ were affected by gentrification following a boom in the tourism sector.The boom has seen a number of buildings fall into the hands of investors who openup tourist facilities. Although this is useful for revitalizing the heritage buildings,again it gentrifies inhabitants. Private buildings were the first victims of gentrifica-tion. According to an interview with a member of a heritage organization in thetown, the private owners perceive the chance of a sale as an opportunity to make afortune, and are therefore selling their buildings to investors quite fast, at relativelylow prices, and then living in the outskirts of the town.

Government buildings are not exceptions to gentrification, as several have beenprivatised. Initially, a government sale was justified to secure maintenance of whatare described as ‘houses in poor condition without architectural significance’ (daCosta and Meffert 1991). Nevertheless, the sales continue, unregulated, and the soldbuildings are out of government control. They are bought by entrepreneurs, who inturn sell them to investors. The exact number of buildings sold by the governmentto date could not be obtained because sales are unsystematic and undisclosed. How-ever, some 135 such buildings were reported to have been sold in 1985 (da Costaand Meffert 1990). Later, a survey reported privatization has reduced the amount ofpublicly owned buildings in the town from 33% in 1982 to 24% in 1993 (Siravo1996). There has been a lot of market activity since 1993; hence a much highershift in ownership from public to private hands is possible. With the recent rapidconversion of those properties to tourist facilities, gentrification of private and pub-lic buildings in the STZ is now far greater than what Marks (1996) had previouslyobserved. This is evident as most people who spoke to us during our researchexpressed concern over the fast-changing demography of the town, and warned ifthis situation is not brought under control the town will soon become a tourist habi-tat and would therefore lose its natives, as well as its cultural charm.

Waqf tenants have seldom been gentrified, except in a few cases of corruption.Because of its strict rules, waqf buildings possess a certain immunity against com-mercialization. The fact that social welfare is at the forefront of waqf traditions hasfurther shielded tenants from commercial forces. It has even proved resistant to theBritish colonial policy, which planned to commercialise waqf properties. In one ofthe confidential records of the WC a British officer is reported to lament on Muslimjurists’ (Kadhis) frequent rejection of its business plans. The officer said, ‘it has

International Journal of Heritage Studies 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

been custom only to summon the Kadhis when any question of Mohamedan Lawarose, as, from business point of view they have few suggestions to offer’.18

Over-commercialization is suppressed in waqf traditions, because it can easilyundermine social aspects envisaged by waqf, although some scholars are trying tobring entrepreneurial elements to the surface (Kahf 1998). Again, as shown above,a property set to waqf is dedicated basically to support social functions in additionto its maintenance. This function is either achieved by waqf beneficiaries occupyingwaqf premises19 or enjoying its share of rental income. The priority of waqf is peo-ple (especially the poor) over property (profit), which provides its buildings the bestimmunity against gentrification, and hence insures social sustainability.

The emphasis on people over profit is evident in many facets of waqf buildings.One is the fact that its rental fees are the lowest among the STZ buildings. A mar-ket survey during our research revealed that the minimum monthly rent a tenant ofwaqf building pays for a single bedroom unit is US$3.70, nearly one-tenth that of aminimum monthly rent for a private property. In fact, even the government, whichadvocates a low rental housing policy, has its rent higher than that of waqf. It is thecharity dimension in waqf that prioritises people and keeps its rent lower than thepolicy requirement or profit motivation.

In an interesting case, a waqf of a two-storey former caravanserai in theKiponda area of the stone town accommodates some 22 families (Figure 5). Thisbuilding is nicknamed ‘jumba la bure’, meaning a ‘free house’ because tenants livevirtually rent free. An interview with one of the tenants of this former caravanserai

Figure 5. Entrance to an 1892 caravanserai at Kiponda, one of the waqf buildingsproviding shelter for several urban poor of STZ (source: the authors).

10 K.A. Khalfan and N. Ogura

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

revealed that, although she recognises the overcrowded condition of the building,she and other tenants believe, since the building is a waqf property, that they allhave the right to live in it as such. Nonetheless, this is a mistaken belief by manyin the town, caused perhaps by the WTC, the landlord administrator of waqf proper-ties, being so sympathetic to the tenants (Yahya 2008) in addition to its inefficientmanagement. The sympathy is nevertheless not confined to the present WTC. TheBritish WC was much stricter, for sake of commercial manoeuvre, but the status ofthe social elements in waqf could hardly be suspended in its demand for rent reduc-tion. A number of tenants complained about the economic downturn that hit Zanzi-bar during WWII, and so demanded reduction in the rent that waqf offered.20 Thewaqf’s low rental fee so affected the condition of its buildings that after long-termdeterioration the WTC reviewed its rent scheme in 2008 to subsidise maintenance.However, new rents are still lower and affordable to the poor occupants.

The social sustainability in waqf is strengthened by its ability to avoid commer-cial affiliations. The only time waqf buildings were said to be mortgaged, sold orinvolved in market shares was during the British hegemony,21 despite explicit state-ments by awqaf dedicators that they should not be mortgaged or sold (Box 1).Muslim jurists protested this strongly, but at times their voices fall on deaf ears andthe British sold some properties anonymously.22

Another factor strengthening social sustainability is that, to date, most waqfbuildings have retained their intended charity status as well as their original func-tions. As these properties are not allowed to be sold, they are prevented fromchanging hands. Hence their ownership becomes stable. The stability in ownership,and its sympathy to tenants, allows to a large extent the preservation of bothproperty and occupants. It is common today to find two generations of a family stillliving in the same house as tenants.

Managerial aspects

As described above, the traditional management of waqf property is vested on anindividual mutawalli who is the sole administrator of a particular waqf. Thus, sus-tainability of a waqf depends a great deal on the actions of the mutawalli. This hasperhaps prompted the majority of waqf founders to initially dedicate themselves asmutawalli, and after their death others in their lineage take over (see Box 1). In afew cases mutawallis were appointed from outside the family circle, and were oftenelders or educated persons. In so doing, dedicators attempted to find someone trust-worthy to secure administration of their property.

People would often volunteer for religious duties, especially in societies livingby religious traditions. This is evident in Islam, because it does not separate betweenpeople, religion and state. However, waqf seems to be out of reach of such volun-teers, due to the fact that people are easily tempered by money. Thus, waqf traditionallowed for a person administering a waqf to be remunerated from its income, as pre-viously noted. This tradition apparently attempted to decrease temptation andincrease mutawalli commitment. An amount between 5% and 10% of waqf incomewas found to be allocated in waqf deeds to remunerate mutawalli. However, for amutawalli solely dependent on the income, this proportion is relatively low, consider-ing waqf responsibilities, the ability of waqf to generate enough income, and in somecases economic downturn and rising living expenses. For those who have otherlucrative sources, it might even be of little significance. Hence, a mutawalli’s

International Journal of Heritage Studies 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

commitment, a significant factor of managerial sustainability in the waqf system, isapparently secured through credibility and trust rather than by monetary patronage.23

The relationship between waqf property, beneficiaries, and mutawalli providesthe waqf management system with an automated means of regulation and control(Figure 6). The beneficiaries depend on the income derived from the property fortheir living. Similarly, for the property to be sustainable, it has to be maintainedfrom the funds it generates. The poor beneficiaries would certainly like to see theshare of their income continue. The share depends on the ability of the property togenerate funds, which in turn depends on the attractiveness of the building. It is theduty of the mutawalli to perform proper maintenance to ensure the property attractstenants’ interest. Therefore, the mutawalli is ‘hooked’ between the demands of thebeneficiaries (income) and the requirements of the property (maintenance). It fol-lows that mutawalli becomes the focal point of the system whose watchdogs arethe beneficiaries. The demands from beneficiaries and the requirements of the prop-erty are what make the system work. When the system’s performance is satisfactory,maintenance is guaranteed and so is the property’s preservation.

There are two other factors that contribute to the managerial sustainability of atraditional waqf system. One is its decentralised management. It is shown above thatwaqf properties are administered independently. The success of this system providesa sharp contrast with that of waqf administration during the British colonial period,when the properties were centralised under the British WC. The WC was smearedwith scandalous practices that included misappropriation of funds and the disappear-ance of several properties in its register.24 This was a result of involving a numberof people, some of them dishonest. The more people that are involved the greaterthe risk of dishonesty. Conversely, in the decentralised management structure, sucheffects are confined within a single property and cannot affect a larger number ofthem. Additionally, a decentralised system is locality oriented; it allows the benefi-ciaries and mutawalli to be closer; hence the former can monitor the actions of thelatter. The second factor is the cost of administration. A system involving a singleadministrator is absolutely cost effective. Much of its income could then be appliedto basic functions. The maintenance share would therefore be higher. This is useful,especially during periods of economic downturn, when the income yields relativelylittle, which needs to be divided between several competing demands.

Beneficiary

Property

Maintenance

Income

Mutawalli (facilitator)

Mutawalli (facilitator)

Beneficiary (watchdog)

Mutawalli (facilitator)

Figure 6. The interlink relationships between subjects of traditional waqf management(source: the authors).

12 K.A. Khalfan and N. Ogura

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

Environmental sustainability

The benefits of conserving built heritage involve its contribution to the naturalenvironment. When renovation and re-use of old or existing building stock ismeasured against their demolition, and the construction of new facilities, the formerminimises environmental destruction, in terms of material input and disposal duringthe construction life cycle.

Waqf tradition contributes to the environment in that it always seeks prolongedbuilding life and strives to prevent building demolition at all costs. One of the prac-tical ways in which waqf achieves this is through the so-called long-term lease(LTL). In this arrangement a building is leased on a longer period of up to 70 years.The lease involves a sacrifice at the expense of property survival. LTL was foundto be particularly applied to buildings threatened by their very low income, whichcannot sustain the upkeep, nor produce sufficient funds to remunerate beneficiaries.It was therefore used as a last resort in building-rescue efforts. In 1937, a waqf of ahouse of a dedicator named Hamed bin Mzaham was about to be demolished bythe British municipal authority, due to its poor inhabitable condition, but it wassaved from demolition through the procurement of a 10-year lease by a lessee whopaid a monthly rent of only 1 shilling.25 By 10 November 1944, minutes of theWC reported some 58 waqf houses were held on long-term leases in the town.26

Leasing a building for such a long time for very low rent may sound awkward.In fact, the LTL is carried out as a mutual benefit to hold the property rather thanto demolish it. Thus, it has its long-term survival benefits, which include environ-mental promotion, which are more important than its income. The lower rentsoffered in such leases are intended to encourage repairs, in order to retain the build-ings, regardless of their financial benefits. The LTL binds the lessee to undertakewhatever repairs are required, be they structural or to fabric, over the whole periodof the lease; a modest contribution but one which safeguards buildings.

Drawbacks to waqf sustainability

While in many aspects waqf was found to be potentially sustainable, there are somecrucial situations that may compromise its sustainability. In the event that the waqfis alienated its long-term commitment is cut off, and so is its sustainability. Basi-cally, waqf rules strictly prohibit property alienation (Box 1). Some schools of Isla-mic jurisprudence allow alienation in exceptional situations (Maghniyyah 1998),27

although this is disputed by other conservative schools that object to alienationunder any circumstances. However, those in favour of the alienation demand areplacement for an alienated property. This aspect may be considered desirableunder extreme circumstances, since the replacement is supposed to provide a soun-der property that is potentially a more sustainable heritage in the future,28 and atthe same time keeps the number of properties constant. This thinking has helpedobtain the replacement of several waqf buildings that were unilaterally sold by theBritish for reasons that were unconvincing to Muslim jurists, such as accessibilityand low income.29 Ideally, the numbers of waqf properties are supposed to increaserather than decrease. Therefore, despite alienation terminating the sustainability ofthe original property, it establishes another property, which may be considered use-ful in creating a sustainable heritage in the future. Since this is only done in ratherexceptional cases it cannot harm the greater part of awqaf.

International Journal of Heritage Studies 13

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

Records indicate there is no fixed number of beneficiaries a waqf ought to serve.This has an economic implication to the waqf. In case the amount of incomegenerated by the waqf is too little to impress a large number of beneficiaries, thebeneficiaries might become less interested in it. They may no longer be motivatedto monitor the mutawalli. Consequently, this may pave the way for the deteriorationof properties, and eventually the loss of waqf. When Box 1 above is examined, thewaqf logically limits the size of beneficiaries by fixing it to a particular generation.However, its size depends on the number of members in the generation.

In one case, which was exceptional but could be representative of this scenario,a renowned waqf of Mauli had some 175 beneficiaries. Despite the waqf’s vastamount of land the ratio of its income to the beneficiaries was relatively low. In1939, the waqf yielded some 884 shillings, that when divided among the beneficia-ries meant that they would each receive some 5 shillings, which would hardlyimpress them.30 Nevertheless, upon the beneficiaries’ agreement the laws allowedsuch a waqf to benefit, for example, a public facility instead, if it were to serve acharitable purpose. In fact, as Box 1 implies, several private awqaf were establishedto benefit the greater public after the extinction of the family lineage. This is per-haps a better way to restore its sustainability.

Conclusion

This study explored some ways in which the tradition of Islamic waqf has helpedto achieve sustainable preservation of properties in the heritage Stone Town of Zan-zibar. From this exploration emerged a number of ideas to consider for applicationin conserving built heritage. First and foremost is the idea of having conservation‘inherent in the heritage itself’. This idea suggests shifting from impromptu conser-vation practices towards a conservation that is embodied in the building systemsthemselves. The mechanism of such a conservation should function in such a waythat it is maintained along with the building systems until the building is consideredas worthy of status as heritage and continues to support the survival of the heritageproperty in the future. Methods of achieving inherent conservation may vary fromone heritage property to another and the creation of a particular method depends oneach heritage property’s specific circumstances.

Second, waqf shows practically the benefits of heritage use vis-à-vis commercialconsumption, and how to strike a balance between the two. The result of such anidea leads to a third point, on how to deal with the gentrification of heritage sites.According to waqf, it is only through a true and sympathetic spirit that gentrifica-tion in heritage sites could be prevented or minimised. By placing social use aheadof commercialization, heritage sites would be able to retain their inhabitants, and sotheir cultural flavours. This could be achieved if conservation activities involve sac-rifices, in particular financial ones. The sacrifices lead to a fourth point to be con-sidered.

The fifth and last point relates to the way a large number of facilities could becollectively sustained to contribute to the conservation of a wider area, and subse-quently urban preservation as opposed to maintaining individual structures. Individ-ual buildings may foster conservation other than their own, if they can extend theshare of their income to those with meagre or no income at all. This may be doneeven at the international level. Concerted efforts may be organised to benefit heri-tage beyond local borders. Through these efforts, heritage agencies may not only be

14 K.A. Khalfan and N. Ogura

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

able to share finance, but may also benefit from each other’s practice. Such a prac-tice supports the very idea that world heritage belongs to all humanity, regardless ofgeographical borders.

AcknowledgementsThe authors are grateful for kind support to this research by Mr. Abuu Ahmada Shani(heritage enthusiast), Mr. Hajj Mohammed Hajj (field advisor), Mr. Omar Sheha (ZanzibarNational Archives), Mr. Abdulla Talib (Waqf and Trust Commission), and Prof. AbdulSheriff (Zanzibar Indian Ocean Research Institute).

Notes on contributorsKhalfan Amour Khalfan is a PhD candidate at the Graduate School of Engineering andScience, University of the Ryukyus, Japan.

Nobuyuki Ogura is Professor of Architecture in the Department of Civil Engineering andArchitecture, University of the Ryukyus, Japan. His research interests are architecturalplanning and history, especially in terms of the adaptation of modernism to developing areasin the tropics.

Notes1. Sustainable methods are still under development in various parts of the world. One of

the recent developments involves community rehabilitation. The Stone Town of Zanzi-bar features one such example under SIDA conservation projects. Several buildingswere renovated by involving the community in order to derive sustainable solutionsfrom them. The project looked quite attractive and sustainable at the outset, and buildingconditions improved considerably (see Battle et al. 2006). Nevertheless, in less than fiveyears its image seems to have changed, casting questions on its future sustainability.

2. Archaeological evidence of mosques built on waqf land dates back at least to thefifteenth century, although extant sites may be only from the seventeenth century.

3. The presence of several schools of Islamic jurisprudence in the history of the townmeans that different extended interpretations of the rudiments were inevitable, as weretheir consequences in the overall practice.

4. The British involved two influential jurists from the Ibadhi and Sunni sects in decidingwaqf matters. The problem of the differing visions on the extended interpretation of therudiments by the schools of law was therefore solved. Their collective decisions couldbe taken as representative of the STZ case.

5. File selection was guided by the archives’ documentation index. In these archives waqffiles are under the HD class of an alphabetical arrangement. The study first made abroad coverage of the HD class, and then a narrower search into its sub-classes wasperformed, according to the relevance of their data to this research. A strategic selectionwas made to include general administrative files featuring British colonial administra-tion daily correspondences stored under the AB class in order to supplement the infor-mation of the HD class.

6. The traditions of the Prophet are recorded in some six major collections. One of themost authentic of these collections is that of Sahih Muslim. For the tradition pertainingto the explanation in this paragraph see Sahih Muslim, Book #13, Tradition #4006.

7. The authors are currently working on an article detailing the link between Islamic waqfand architectural conservation.

8. Private ownership is the predominant form of land-holding in the town. According toresearch by Khalfan and Ogura (2010), a considerable number of private buildings havebeen sold to investors, who radically alter them to meet the requirements for touristfacilities, and there has been an increase in radical alterations over the past decade.

9. ZNA: Minute No. 9 of 28 June 1939 (HD 10/7).10. Expo 2010 Shanghai China, http://en.expo2010.cn [Accessed 25 February 2011].

International Journal of Heritage Studies 15

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

11. See section on ‘Drawbacks to waqf sustainability’ on the way alienation is dealt with inwaqf ideologies.

12. List of mosques and corresponding properties dedicated for their upkeep, found inZNA, HD 4/68.

13. ZNA: HD 4/67 provides an extensive list of properties dedicated to the Hujjat IslamJamaat.

14. ZNA: HD 10/7, HD 10/24.15. ZNA: Correspondence between Waqf department and the Honourable Chief Secretary to

the Government, Zanzibar, 16 November 1949 (AB 22/8); Records of a discussionbetween Hon. Sh. Seif bin Suleiman, the Provincial Commissioner and the Secretary ofthe Waqf Commission 8 January 1940 (HD 10/85).

16. For the criteria used to inscribe the STZ in the heritage list, see World Heritage List:Stone Town of Zanzibar, http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/173 [Accessed 13 February 2011].

17. The term gentrification refers to extinction of social-cultural elements (existing inhabit-ants) in heritage as a result of revitalization of historic areas.

18. ZNA: Correspondence from the Secretary the Waqf Commission to the Chief Secretaryof 12 December 1916 (HD 5/18).

19. ZNA: Development of waqf decrees and their subsequent discussion (HD 10/37).20. For rent reductions see ZNA: Secretary to the Waqf Commision and Public Trustee to

The Chief Secretary, 13 May 1944 (HD 10/53); AB 34/2; Minute No. 12 of a meetingheld on 28 June 1939 (HD 10/7).

21. Waqf of Syd Hamoud Ahmed was one example of a highly valued mortgaged property.It was mortagaged for 77,000 shillings by the British Waqf Commissioners (ZNA: HD10/51).

22. ZNA: Secretary Waqf Department 12 December 1916 (HD 5/18); Sheikhs Hamed binSmit and Ali Mahomed versus Acting Secretary Waqf Commission 11 March 1915 (HD10/9); Maloo Brothers and Co. to The Secretary Waqf Commission, 24 November 1934(HD 3/21); From Ibadhi and Sunni Qadhi to Acting Secretary of the Waqf Commission,16 March 1915 (HD 10/9).

23. In traditional Islam, trust was regarded as among the major credentials that defined thecharacter of good personnel. It grew to such an extent that some scholars associate itwith the development of a bank cheque in Muslim Spain. It is reported that a persontravelling on a pilgrimage could be remitted with funds in Mecca after presenting asigned paper from an authority in Spain (for details see Nyang n.d.).

24. ZNA: Confidential letter from District Officer, Zanzibar to H.B.M’s Diplomatic Agentand Consul General, Zanzibar, 14 March 1914 (AB 34/1).

25. According to the East African currency bills of 1939 and 1955, 1 British Pound = 20shillings. See also Minute No. 12 of a meeting held on 28th June 1939 (ZNA: HD 10/7).

26. ZNA: Secretary Waqf Commission to Hon. Chief Secretary, 10 November 1944 (HD10/53).

27. Some of the situations in which alienation of waqf may be allowed include: 1) whenthe waqf is considered unfit for its intended purpose; and 2) when there is the need forconstruction of a public facility, like a roadway, that has to pass across the property.

28. ZNA: Minute No. 10 of 20 October 1943 (HD 10/46).29. ZNA: Sheikhs Hamed bin Smit and Ali Mahomed versus Acting Secretary Waqf Com-

mission 11 March 1915 (HD 10/9); Secretary Waqf Commission to Chief Secretary, 3May 1924 (AB 34/35); HD 3/21.

30. ZNA: Minute No. 22 on the distribution of income from Mauli waqf, Minutes of meet-ing held on 28 June 1939 (HD 10/7).

ReferencesAssi, E., 2008. Islamic waqf and management of cultural heritage in Palestine. International

Journal of Heritage Studies, 14 (4), 380–385.Bang, A.K., 2000. Sufis and scholars of the sea: the sufi and family networks of Ahmad ibn

Sumayt and the Tariqa ‘Alawiyya in East Africa c. 1860–1925. Unpublished PhD thesis,University of Bergen.

16 K.A. Khalfan and N. Ogura

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011

Bang, A.K., 2002. Cash crossing the sea: waqf distribution to Mecca and Medina, ca. 1870–1940, scholarly and financial links over three generations. Unpublished article, Univer-sity of California, Los Angeles.

Battle, S., et al., 2006. Fighting poverty in historical cities: an example from Africa. Schoolof Art and Communication, Malmo University, for SIDA and Aga Khan Trust forCulture.

da Costa, T. and Meffert, E.F., 1990. The Stone Town of Zanzibar. In: R. Powell, ed. The archi-tecture of housing. Singapore: Concept Media, for Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

da Costa, T. and Meffert, E.F., 1991. Rehabilitation of the Stone Town of Zanzibar. Proceed-ings of the International Seminar on the Improvement of Housing Conditions and Reha-bilitation of Historic Centers. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT.

Douglas, J., 2006. Building adaptation. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.Ergun, N., 2004. Gentrification in Istanbul. Cities, 1 (5), 391–405.Hennigan, P.C., 2004. The birth of a legal institution: the formation of the waqf in third-cen-

tury A.H. Hanafi legal discourse. In: R. Peters and W. Bernard, eds. Studies in Islamiclaw and society. Volume 18. Boston: Brill.

Jokilehto, J., 1999. A history of architectural conservation. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.Kahf, M., 1998. Financing the development of awqaf properties. Seminar on the Develop-

ment of Awqaf. IRTI, March 2–4, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.Khalfan, K.A. and Ogura, N., 2010. Influence of outsourced finance on conservation of built

heritage in a developing country: the case study of Stone Town of Zanzibar. Journal ofArchitecture and Planning, 75 (656), 2507–2515.

Maghniyyah, A.M.J., 1998. Waqf according to five schools of Islamic law. Al-Tawhid, 7 (4),Part 1, 83–98.

Marks, R., 1996. Conservation and community: the contradictions and ambiguities of tour-ism in the Stone Town of Zanzibar. Habitat International, 20 (2), 265–278.

Nyang, S., n.d., The history of Islam in Spain [online]. Available from: http://www.mecca-centric.com/sulayman_nyang.html [Accessed 24 January 2011].

Oberauer, N., 2008. Fantastic charities: the transformation of waqf practice in colonialZanzibar. Islamic Law and Society, 15, 315–370.

Sheriff, A., 1999. Mosques, merchants and landowners in Zanzibar Stone Town. In: A.Sheriff, ed. The history and conservation of Zanzibar Stone Town. London: Departmentof Archives, Museums and Antiquities/Zanzibar: James Currey, 46–66.

Sheriff, A., 2001. Zanzibar Stone Town: an architectural exploration. Zanzibar: The GalleryPublications.

Siravo, F., 1996. Zanzibar: a plan for the historic Stone Town. Zanzibar: The GalleryPublications.

Tsunoda, M., Harada, S., Toriumi, M., and Yanagisawa, T., 2007. Design for re-use: casestudy of World Exposition 2005, Aichi, Japan. Proceedings of Building Stock Activation,International Conference of 21st Century COE, 5–8 November. Program of TokyoMetropolitan University, Japan.

Yahya, S.S., 2008. Financing social infrastructure and addressing poverty through wakfendowments: experience from Kenya and Tanzania. Environment and Urbanization,20 (2), 427–444.

International Journal of Heritage Studies 17

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Kha

lfan

Kha

lfan

] at

07:

53 1

8 N

ovem

ber

2011