Interiors and Interiority in the Ornamental Dairy Tradition

Transcript of Interiors and Interiority in the Ornamental Dairy Tradition

Decor

Meredith Martin

the sudden death of England’s Queen Mary ii (1662–94) in December 1694 elicited an outpouring of national grief that manifested itself in massive funeral processions and a splendid mausoleum designed by Christopher Wren. In his eulogy at her funeral, Thomas Tenison, Archbishop of Canterbury, praised Mary for being an “incomparable wife” to William iii, and extolled her charity, economy, and humility: “How good, how happy a life was this! ... not of vain pleasure, and soft and unprofitable ease, but of true usefulness and comfort.”1 Later writers similarly celebrated Mary’s domestic virtues—recalling, for instance, how she spent her days practising needlework with her ladies. She was also praised for her self-restraint. In the third edition of King William’s Royal Diary (1705), which contained a section on “The character of his royal consort, Queen Mary ii,” the anonymous author points out that, if the queen had indulged at times in projects of “Architecture and Gardenage,” “she had no other inclinations besides this, to any Diversions that were expensive; and since this employed many Hands, she was pleased to say, That she hoped it would be forgiven her.” “As to the Sobriety which relates to the Palate,” the author continues, she “was so

1 Thomas Tenison, A Sermon Preached at the Funeral of Her Late Majesty Queen Mary of Ever Blessed Memory in the Abbey-Church in Westminster, 5 March 1694–5 (London: H. Hills, 1709), 10. For a description of Mary’s funeral, see Ralph Hyde, “Romeyn de Hooghe and the Funeral of the People’s Queen,” Print Quarterly 15, no. 2 (1998): 150–72.

Interiors and Interiority in the Ornamental Dairy Tradition

Eighteenth-Century Fiction 20, no. 3 (Spring 2008) © ECF 0840-6286

358

far from being fond of great Dainties, that I heard her once say, That she could live in a Dairy.”2

Why is the building type of the dairy so revealing of Mary’s character? As a site of exemplary hygiene, temperance, and feminine productivity, the dairy was an architectural surrogate for the queen herself, just as it was for other elite women of her time. I will examine the intimate association between dairies and elite women in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England, as that relationship was envisioned in a range of texts, including novels, household manuals, and architectural treatises. I focus on ornamental dairies that were built for such women patrons as Queen Mary ii, Queen Caroline, Elizabeth Yorke, and Elizabeth Craven and that distinguish themselves from working dairies by the care given to their architectural design, by their luxurious interior decoration, and by their representational, as opposed to practical, function. In this period, ornamental dairies were important sites of self-expression for royal and aristocratic women, who commissioned these buildings to engage with and, in some cases, subvert contemporary ideas of class, femininity, and domesticity. Ornamental dairies also offered women patrons the opportunity to work closely with such architects and entrepreneurs as John Soane and Josiah Wedgwood, who used this building type to experiment with new design ideas and explore new techniques of production and consumption.

In England, the association between dairies and women extends at least as far back as the medieval era, and is etymological as well as historical.3 A number of early modern treatises on household management discuss the practical and symbolic aspects of dairying, and associate well-run dairies with well-domesticated women. Gervase Markham’s The English Housewife, a popular tract first published in 1615, analogizes a spotlessly clean dairy to a housewife of spotless character, and idealizes certain attributes that relate to a woman’s work in the dairy: purity, patience, gentleness, delicacy, and charity. Many of these attributes later appear in conduct books as being naturally linked to “good” 2 The Royal Diary, 3rd ed. (London, 1705), 3–4.3 Harold McGee points out that the English word “dairy” comes from “dey-

ey,” and refers to the place “in which a dey, or woman servant, made milk into butter and cheese.” McGee, On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (1984; rev. ed., New York: Scribner, 2004), 11.

M a r t i n

359D

ecorwomen, but to Markham they are not so much essential female qualities as they are behaviours learned through activities that women perform in the dairy—among them caring for cows and other animals, handling dairy ware, and giving away milk products to impoverished neighbours.4

Dairies also satisfied an emotional need for women, according to Bartholomew Dowe’s A Dairie Booke for Good Huswives (1588). Dowe asserted that dairying helped women “withdraw ... from dumpes and sullen fantasies (being a common disease amongst women) to bee the quicker spirited, the better and the livelier occupied, and the lustier stomaked in all their business.”5 The implicit assumption in Dowe’s account—that women have a tendency towards indolence, poor appetite, and moodiness—presages the eighteenth-century invention of the boudoir (from the French verb bouder, to “sulk” or to “pout”), a space that was understood to indulge these characteristically feminine traits.6 It also anticipates eighteenth-century theories of architectural “character,” whereby certain rooms or building types were imagined to mould the attitudes and behaviours of those who interacted with them. Unlike the boudoir, the dairy promised to cure indulgent, idle women through exercise and honest labour, turning them away from their own self-regard towards more practical and collective responsibilities.

Dairying demanded hard work in often dirty circumstances. In the early modern period, most of this work was done by women servants, rather than the literate middle-class and upper-class women to whom Dowe’s and Markham’s manuals were directed.7 Those well-born women played more managerial roles. But they still reaped the symbolic benefits of the dairy’s association with purity, abundance, and domesticity, even more so than their social inferiors because they did not have to get their own hands dirty and because they did not need to sell their products to make a living.

4 Gervase Markham, The English Housewife, ed. Michael R. Best (1615; Montreal, Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986), 166–79. See also Best’s introduction, xlv–xlvi.

5 Bartholomew Dowe, A Dairie Booke for Good Huswives, appended to The Housholders Philosophie, an English translation of Torquato Tasso’s Padre di famiglia (London, 1588).

6 Ed Lilley, “The Name of the Boudoir,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 53, no. 2 (1994): 193–98.

7 Best, xlvi.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

360

By scrupulously overseeing the dairy and its activities—an arena where, unlike other parts of the estate, they could exert near-total control—elite women distinguished themselves from their female servants and demonstrated their virtuousness whenever members of their own class visited their dairies.8

The primary audience for this performance of domestic femi-ninity seems to have been other women. This can be observed in memoirs and travel accounts written by such women as Sophie von La Roche, who toured Osterley Park in 1786 and wrote a rhapsodic description of its dairy and dairy maid (both of which, she noted, “surpassed all my expectations ... greater sweetness or neatness are impossible”), and in such novels as Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded (1740), in which Pamela ventures on a “little airing” to a nearby farmhouse “noted for a fine dairy,” and remarks admiringly on the “neatness” of not only the house but also its “good woman, and daughter, and maid.”9

The relationship between dairies and elite Englishwomen was never entirely symbolic, however. Even queens were expected to know something of the realities of housewifery, as evidenced by a popular seventeenth-century series of books entitled The Queen’s Closet Opened (1655), which “turn[ed] household management into a branch of national government.”10 In fact, royal women were among the first to take advantage of the expressive potential offered by ornamental dairies. It is perhaps not surprising, given her interest in domesticity, that Queen Mary ii commissioned one of the earliest examples of an ornamental dairy at Hampton Court in the early 1690s. The queen’s dairy was installed in the Water Gallery, a sixteenth-century Tudor brick structure situated at the south end of the palace’s privy garden, overlooking the

8 “Dairying among fashionable ladies could thus serve the dual purpose of confirming their elite status while also creating an image of virtuous domes-ticity.” Ingrid H. Tague, Women of Quality: Accepting and Contesting Ideals of Femininity in England, 1690–1760 (Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2002), 129.

9 Sophie von La Roche, Sophie in London, 1786; Being the Diary of Sophie v. la Roche, trans. Clare Williams (London: Jonathan Cape, 1933), 227; Samuel Richardson, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded, ed. Thomas Keymer and Alice Wakely (1740; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 476.

10 Jane Archer, “The Queen’s Arcanum: Authorship and Authority in The Queen’s Closet Opened (1655),” Renaissance Journal 1, no. 6 (2002): 14–26. Several new editions of the book appeared in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

M a r t i n

361D

ecor

Thames. Soon after William and Mary acceded to the throne in 1689, royal architects transformed the building and its gardens into a pastoral pleasure retreat for the queen.

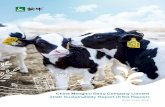

Most of the work on the Water Gallery involved interior ren-ovations. Godfrey Kneller’s portraits of Mary’s ladies-in-waiting, or “beauties,” were hung in a long rectangular gallery in the upper floor. Four smaller rooms were created off this gallery, including a mirrored closet decorated with flower paintings and a cabinet displaying Mary’s extensive collection of porcelain. In the lower storey, the queen’s designers remodelled a bathing pavilion and an earlier dairy, which had been outfitted in the 1670s for the Duchess of Cleveland, the former mistress of Charles ii.11 The new dairy, with decorations attributed to the Huguenot designer Daniel Marot, was tiled in Mary’s favourite blue-and-white Delftware, which complemented an elegant set of Delft milk pans and serving bowls depicting farmhouses, cows, and other bucolic motifs (see figure 1). Perhaps to underscore this theme of rusticity, a small grotto was added to a nearby stairwell.12

11 Simon Thurley, Hampton Court: A Social and Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 172–74; H.M. Colvin et al., The History of the King’s Works, vol. 5 (1660–1782), 157–67. On the Duchess of Cleveland’s dairy, see Thurley, 172.

12 Arthur Lane, “Daniel Marot: Designer of Delft Vases and of Gardens at Hampton Court,” Connoisseur 123 (1949): 19–24; Adriana Turpin, “A Table for Queen Mary’s Water Gallery at Hampton Court,” Apollo 149, no. 443

Figure 1. Delftware milk pan created for Mary ii’s dairy at the Water Gallery, Hampton Court, c. 1694. V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Reproduced by permission.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

362

Daniel Defoe, who toured the queen’s Water Gallery soon after it was completed, was impressed. In A Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724–26), he wrote: “Her majesty had here a fine apartment, with a sett of lodgings, for her private retreat only, but most exquisitely furnish’d ... here was also her majesty’s fine Collection of Delft ware, which indeed was very large and fine; and here was also a vast stock of fine china ware, the like thereof was not then to be seen in England ... also a dairy, with all its conveniences, in which her majesty took great delight.”13 Defoe emphasizes the pleasurable and luxurious aspects of the Water Gallery and its dairy. According to this passage, it appears to have been a place where the queen displayed her innovative taste to visitors, an observation that would seem to contradict Defoe’s characterization of the complex as a purely “private” retreat.

Although few accounts remain of how Queen Mary actually used her dairy, it seems likely that she conceived it as a space in which to consume dairy products and display Delftware in a socially acceptable and politically expedient manner. A pristine dairy would have enhanced Mary’s carefully crafted image as a retiring, domestic counterpart to her husband, King William, and it may have also served as a symbol of her ability to provide and care for the state, especially since she was unable to produce an heir. The queen, who suffered from poor health for most of her life, also relied on the dairy for her daily consumption of fresh milk, a regimen that neo-Hippocratic physicians such as Thomas Sydenham (1624–89) began recommending in the late seventeenth century to treat various ailments. (Unlike other dairy products such as butter and cheese, milk was not a commonly ingested substance in early modern England, and its use among the elite in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries remained, for the most part, medicinal.) Following the advice of her doctors, Mary embarked on a restrictive diet of asses’ milk in May 1694.

(1999): 3–14. A drawing of the grotto appears in Hampton Court Palace, 1689–1702, Original Wren Drawings from the Sir John Soane’s Museum and All Souls Collections, ed. Arthur T. Bolton and H. Duncan Hendry (Oxford: The Wren Society at the University Press, 1927), plate 24.

13 Daniel Defoe, A Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain, ed. P.N. Furbank, W.R. Owens, and A.J. Coulson, vol. 1 (1724–26; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 72. The Water Gallery, which was torn down in 1700, is also described in The Journeys of Celia Fiennes, ed. Christopher Morris (London: Cresset Press, 1949), 59–60.

M a r t i n

363D

ecorShe was also said to have bathed in milk to maintain a youthful appearance.14 The dairy’s association with natural and fashionable regimens like the “milk cure” remained an important aspect of its appeal to aristocratic women in the eighteenth century.

Several queens and princesses followed Mary’s example in commissioning ornamental dairies, suggesting that for them, too, this building type may have helped signify their ability to provide for England and ensure its continued health and prosperity. This symbolism was achieved through the dairy’s longstanding cultural association with industrious, beneficent women and through its connection to milk, which connoted pastoral abundance, nurture, and fertility. For foreign-born queens, constructing a dairy may have also offered an opportunity to demonstrate their Englishness.15 This was an especially pressing issue for Hanover-ian women who, along with their husbands, ruled England in the eighteenth century, a fact that may help explain why so many royal women from this lineage commissioned dairies during this period: Queen Caroline at Richmond Gardens near Kew, her daughter Princess Amelia at Gunnersbury Park in Middlesex, and Queen Charlotte at Frogmore in Windsor Home Park.16

Caroline of Brandenburg-Anspach (1683–1737), the German-born queen consort of George ii, assisted Charles Bridgeman and William Kent in laying out her royal gardens at Richmond in the 1720s and 1730s. The program included the construction of several garden buildings, among them a neo-Palladian dairy, a rustic hermitage, and a Gothic-inspired “Merlin’s Cave.” In John Rocque’s published plan of Richmond from 1734, elevation views of these three buildings appear as vignettes on either side of the garden. Caroline’s dairy is also illustrated in A Description of the Royal Gardens at Richmond in Surry (1736), with the anonymous

14 John van der Kiste, William and Mary (Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton, 2003), 173. I discuss the connection between milk and neo-Hippocratic theories of health and medicine in Dairy Queens: Pastoral Architecture and Patronage from Catherine de’ Medici to Marie-Antoinette (forthcoming).

15 Wendy Wall has detected a nationalist undertone in Markham’s book. Wall, Staging Domesticity: Household Work and English Identity in Early Modern Drama (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 38–39.

16 The dairy at Richmond is discussed below. On Princess Amelia’s dairy at Gunnersbury, see Pierre de la Ruffinière du Prey, “Eight Maids-a-Milking: Ornamental Dairies and Their Owners,” Country Life 181 (5 March 1987): 120; on Frogmore, see Christopher Christie, The British Country House in the Eighteenth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), 159.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

364

author characterizing it as “A neat but low Brick Building, with Venetian windows, the Walls covered with Stucco, within most amply furnished, the Utensils for the Milk being of the most beautiful China.”17

Scholarly accounts of Richmond gardens have devoted more attention to the hermitage and Merlin’s Cave than to the dairy. The hermitage has been described as a place where Caroline showcased her scientific and philosophical pursuits, while the cave, which contained her library and life-size waxwork figures of Queen Elizabeth and others, is said to have demonstrated her literary interests and political capabilities.18 But if, as Sue Bennett has maintained, the garden was for Caroline “both a private space designed for her own personal pleasure and an exercise in royal propaganda,” one could argue that Caroline’s dairy also played a role in her self-image both as a woman of fashionable taste and as the quintessentially “English housewife.”19 By emphasizing her domesticity, Caroline’s dairy may have helped deflect any criticism she would have received with regard to her interest in the more traditionally masculine domains of science, philosophy, and politics. Building a dairy may have enabled the queen to maintain the appearance of adhering to culturally conceived gender boundaries while challenging these boundaries in other, more intellectual arenas.

“Consumption will be great for Dairies”

Ornamental dairies became increasingly popular in England in the last two-thirds of the eighteenth century. They also became increasingly “ornamental” and were devoted more frequently to consumption than production. Several architectural modifications occurred with the building type around this time. Once located near the main house or near service buildings for practical purposes, dairies now became a centrepiece of the pleasure gar-den, a place associated not with domestic labour but leisured

17 A Description of the Royal Gardens at Richmond in Surry (London, 1736), 9.18 Judith Colton, “Merlin’s Cave and Queen Caroline: Garden Art as Political

Propaganda,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 10, no. 1 (1976): 1–20; Colton, “Kent’s Hermitage for Queen Caroline at Richmond,” Architectura (1974): 181–91.

19 Sue Bennett, Five Centuries of Women and Gardens (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2000), 50–51.

M a r t i n

365D

ecor

sociability. Queen Caroline’s dairy at Richmond illustrates the evolution of dairies into elegant, freestanding pavilions, one of the key destination points during a tour of the aristocratic estate. (A picturesque dairy designed around 1787 for Lavinia, Countess Spencer, at Althorp in Northamptonshire also demonstrates this shift.) Moreover, changes in the dairy’s interior layout occurred around this time. Not only were more rooms added, but these rooms were also subdivided into spaces of work, leisure, and display. This trans formation can be observed in a 1783 plan by John Soane for a dairy that features an entrance portico; a scalding room; a presentation room with shelves for displaying porcelain; and a strawberry room, where fashionable visitors could retire to enjoy a snack of fresh fruit and cream (see figure 2).20 20 These modifications might initially be attributed to the rise of early capitalism,

which, as some historians have argued, transformed the home into an arena for consumption and housewives themselves into “ornamental status objects.” But such explanations, economic or otherwise, overlook the development of this building type and its connection to elite women. As Amanda Vickery has argued, the effects of capitalism on women have been overdetermined by

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

Figure 2. Designs, in plan and eleva-tion, for an orna-men tal dairy for Elizabeth Yorke, Lady Hardwicke (c. 1782), by John Soane (1753–1837). V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Reproduced by permission.

366

The aesthetic investment in dairies in this period coincided with a new aesthetic investment in the self that, as Ann Berming ham has argued, is uniquely linked to the modern era. In her study of amateur drawing from the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, Bermingham notes that a characteristic need of modern culture is “to imagine the self and the world in terms of representation.” She emphasizes the idea that “aesthetic representational practices like drawing are not only the means through which individuals become socialized into certain roles, but they are also the means through which individuals shape and give meaning to them.”21 Bermingham makes a crucial point that bears repeating: representational practices, objects, and spaces do not simply register socio-economic developments that affect the lives of those who create or interact with them. They are active tools through which individuals experience and make sense of their world and, in doing so, subtly alter it. Following a similar logic, ornamental dairies are not merely places that depict the changing status of elite women in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. They are places where that status is actively constructed, debated, and transformed from within.

Women patrons of ornamental dairies did not possess an unfettered ability to fashion and “perform” their identity in any

historians such as Alice Clark or Lawrence Stone, who posit a pre-capitalist sphere in which propertied women functioned powerfully and efficiently within their households, and a post-capitalist sphere in which women were reduced to functionless “drones.” Such accounts offer a limited definition of the ways that women contributed to the prosperity of their homes and families in the eighteenth century, which included acts of sociability and leisure. They also rely on ideological constructions of femininity as articulated in eighteenth-century conduct books, which, as Vickery observes, do not account for women’s actual experiences, and do not consider alternative ways in which women may have derived self-worth and empowerment. Finally, they set up a binary opposition in which domestic spaces such as dairies move away from being viewed as wholly functional or utilitarian to being viewed as wholly aesthetic or symbolic—an opposition that is contradicted by early modern household manuals such as Markham’s. See Amanda Vickery, “Golden Age to Separate Spheres?: A Review of the Categories and Chronology of English Women’s History,” Historical Journal 36, no. 2 (1993): 383–414; and Vickery, The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). The term “drones” is taken from Stone’s The Family, Sex and Marriage in England. Vickery also cites Alice Clark, Working Life of Women in the Seventeenth Century (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1919).

21 Ann Bermingham, Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), ix, xiv.

M a r t i n

367D

ecorway they saw fit. As in any other era, eighteenth-century men and women were subjected to a range of ideological parameters and behavioural codes that influenced the way they understood and expressed themselves in life and in art. Many historians of the eighteenth century have emphasized the hegemonic power of cultural representations—focusing on textual forms like novels, periodicals, and conduct books—to present categories of idealized (or debased) femininity against which women defined themselves.22 One of these cultural categories was the appropriately domesticated, naturally maternal housewife, who was associated with the virtuous and salubrious environment of the English country estate. Another was the “vile,” self-absorbed female consumer, who thrived in decadent urban environments like opera houses and tea-tables, and who contributed to the decline, rather than the advancement, of home, family, and nation. These stereotypes were often set against each other, for example in Richard Addison’s description of the “good” woman Aurelia and the “bad” woman Fulvia in an early issue of the Spectator (1711–14). Unlike Aurelia, who, “though a Woman of great Quality, delights in the Privacy of a Country Life,” Fulvia “looks upon Discretion and good Housewifery as little domestick Virtues, unbecoming a Woman of Quality ... The missing of an Opera the first Night, would be more afflicting to her than the Death of a Child.”23

Ornamental dairies offer a unique and compelling means for observing how eighteenth-century women responded to normative views of female identity and behaviour. Take, for instance, the eighteenth-century debate regarding women, luxury, and consumption, which has received a great deal of scholarly attention in recent years.24 Elite Englishwomen were

22 Nancy Armstrong, Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987); Kathryn Shevelow, Women and Print Culture: The Construction of Femininity in the Early Periodical (London, New York: Routledge, 1989).

23 Spectator 15 (11 March 1711). See also the character foils “Harriot” and “Lydia” in Spectator 254 (21 December 1711).

24 See, for example, Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Ann Bermingham and John Brewer, eds., The Consumption of Culture, 1600–1800: Image, Object, Text (New York: Routledge, 1995); Victoria de Grazia, with Ellen Furlough, eds., The Sex of Things: Gender and Consumption in Historical Perspective

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

368

caught in a difficult bind in the eighteenth century: they were encouraged, for the health of the nation’s economy, to consume luxury objects, but they were also criticized as lavish and self-indulgent when they did so. In order to manage this dilemma, producers and consumers attempted to transform luxuries into useful necessities, thereby removing the threat that this activity proposed—that of a woman playing a vital role in the public sphere of the marketplace—by associating certain objects with the non-threatening arena of domestic femininity.25 This “polite and commercial” solution is evidenced by the dairy ware that Josiah Wedgwood produced and marketed in the second half of the eighteenth century. Wedgwood’s cultural barometer was especially acute, and he rightly predicted early on, as he wrote to a friend in 1767, that “Consumption will be great for dairies.”26

Wedgwood understood that dairy ware allowed women to maintain their status as consumers—and the many pleasures that consumption could provide—while simultaneously allowing them to engage in a domestic activity that was seen to benefit themselves and the body politic. Before the mid-eighteenth century, a significant percentage of porcelain wares that were produced for and consumed by women (Queen Mary’s Delft milk pans notwithstanding) were devoted to the pastime of tea drinking. But around this time the taking of tea, especially in its association with the all-female environment of the “tea-table,” was linked to the pursuit of solipsistic, frivolous pleasures like gossip and slander, the latter of which is personified as a club-wielding harpy who chases “truth” and “justice” out the door in

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996); John Styles and Amanda Vickery, eds., Gender, Taste, and Material Culture in Great Britain and North America, 1700–1830 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006).

25 Bermingham offers a stimulating discussion of the “domestication” or femin-iza tion of consumer culture in Learning to Draw, chap. 4.

26 Josiah Wedgwood, cited in Alison Kelly, Decorative Wedgwood in Architecture and Furniture (London: Country Life, 1965), 119; Neil McKendrick, “Josiah Wedgwood and the Commercialization of the Potteries,” in McKendrick, John Brewer, and J.H. Plumb, The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commer-cialization of Eighteenth-Century England (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 100–45. The phrase “polite and commercial” comes from William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765–69); see Paul Langford, A Polite and Commercial People: England, 1727–1783 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989).

M a r t i n

369D

ecoran anonymous eighteenth-century engraving entitled The Tea-Table.27 Excessive tea consumption by Englishwomen in this period was also seen to contribute to an enervated and declining population, by rendering many of these women either barren or unable to breastfeed. And, as people of all classes began to drink tea, it came to be seen as a common activity that was ill suited to a woman of refined, aristocratic distinction.

In 1756, the social reformer Jonas Hanway published a polemic entitled “An Essay on Tea” to warn elite women, and especially prospective mothers, about the dangers of tea drinking. In his dedicatory letter to a “Mrs O***,” he wrote, “Madam ... I have long considered tea, not only as a prejudicial article of commerce; but also of a most pernicious tendency with regard to domestic industry and labour; and very injurious to health.” Later on in his text, Hanway articulates a widely felt fear of Britain’s shrinking population: “If our numbers in general really decrease,” he wrote, “we must impute it to libertinism, to absurd customs, to the nature of our amusements, or to the kind of nutriment we take.”28 Hanway warned that tea, an exotic import, was wreaking havoc on the national economy, by encouraging the flow of gold and silver outside of the country to pay for it, as well as for the foreign-manufactured wares associated with its use. He called upon elite women to perform their civic duty not only by refraining from drinking tea but also by discouraging this practice among their female servants and other “common people.” But at the end of his essay Hanway, sensing a consumer reluctance to part with pleasurable, luxurious wares—or perhaps sensing an opportunity to turn a pernicious practice into a socio-economic boon—tried to sell his readers on the virtues of drinking milk: “Suppose we still retain our porcelain cups, and our sipping: I will leave you this indulgence, but it does not follow, that we must continue the use of tea ... Let me seriously recommend to you to exert yourself, and make experiments, on the virtues and flavours of our own herbs, the various uses of milk, and in how many shapes barley and oats are prepared as excellent food” (2:224–25, emphasis added). Hanway was proposing a

27 For further detailed discussion of this image, see Tague, 63.28 Jonas Hanway, “An Essay on Tea,” in A Journal of Eight Days Journey

(London, 1756), 2:62. References are to this edition.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

370

solution that, in his view, availed the nation and its population of virtuous, civic-minded, and domesticated women.29 Although Josiah Wedgwood may not have read Hanway’s tract, he followed its advice by developing a range of vessels in which to store, prepare, and consume milk products. Soon elite women were being tantalized with a dazzling array of Wedgwood dairy ware that included “trainers, skimmers, dairy spoons, whey-cups with covers and stands, and butterkits.”30

Wedgwood helped create a mania for the consumption of milk that was taken up by other architects and designers of the time. He produced ceramic tiles for a dairy’s interior walls that elite women such as Lavinia Spencer were encouraged to decorate themselves, using ivy leaves or other naturalistic motifs. He also offered cream vases or dairy “pails,” an example of which is now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (see figure 3). These earthenware vessels were coated with a smooth, gleaming white surface glaze that complemented an ornamental dairy’s cream-coloured tiled walls, milk pans, and moulded plaster ceilings, and that added to the overall look of purity and cleanliness. By providing an opening in the vase’s cover for a stirring spoon, Wedgwood made these objects the embodiment of the eighteenth-century ideal of uniting the agreeable with the useful.31 Moreover, the vase’s loose approximation of an antique urn befitted a design scheme of rustic neoclassicism that buildings like the Althorp dairy, which was designed with the assistance of Henry Holland, attempted to evoke. This same style was adopted in dairies designed by John Soane, discussed below.

Wedgwood’s success is underscored by his impressive roster of clients, some of whom commissioned elaborate dairies in order

29 “Let me repeat my request most seriously, as you regard yourself, as you regard your country, to make the discovery of some wholesome and agree-able beverage, be it cold, or hot, or warm, to supply the place of tea; and that you will recommend it, in the strongest terms” (Hanway, 2:235).

30 Kelly, 119.31 Lavinia Spencer’s correspondence with Wedgwood regarding the decoration

of her dairy, which dates from 1787, is at the British Library, Add. 77975. It reveals that, along with a set of dairy ware, Lady Spencer ordered from Wedgwood tiles for her dairy’s interior, the size and pattern of which she customized by including in her letter sketches for Wedgwood’s perusal. Lady Spencer also negotiated a lower price—since, as she reminded him, she was buying in bulk—and requested that he fill the order immediately.

M a r t i n

371D

ecor

to fill their interiors with his wares.32 In an effort to stimulate such consumer desire, Wedgwood played up the element of fan-tasy associated with his products. He may have been thinking specifically of dairies when he wrote to his business associate, Thomas Bentley, that their mission was to “amuse, & divert, & please, and astonish, nay & even to ravish the Ladies.”33 Indeed, fantasy was an aspect of dairy design that men such as Wedgwood or Soane had to do little to promote. In the second half of the eighteenth century, elite Englishwomen freely indulged their imaginations, and advanced consumer trends, by commissioning dairies in the “rustic,” “Gothic,” “Moorish,” and “Chinese” tastes. The Chinese style is exemplified by Henry Holland’s design for

32 As Wedgwood wrote to a business associate in 1769, “Lady Gower will build a dairy on purpose to furnish it with Cream Couler if I will engage to make Tiles for the Walls” (cited in Kelly, 119).

33 Wedgwood to Thomas Bentley, cited in Bermingham, Learning to Draw, 154.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

Figure 3. Josiah Wedgwood, cream vase designed for an ornamental dairy, c. 1785–1800. V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Reproduced by permission.

372 M a r t i n

Figures 4 and 5. Henry Holland, “Chinese Dairy” at Woburn Abbey, late 1780s, interior (top) and exterior (bottom) views. ©Meredith Martin. Reproduced by the kind permission of His Grace the Duke of Bedford and the Trustees of the Bedford Estates. All rights reserved.

373D

ecora Chinese dairy that was built for the Duchess of Bedford at Woburn Abbey in the late 1780s (see figures 4 and 5).

The interior of the Woburn dairy, with ornamental details inspired by William Chambers’s Designs of Chinese Buildings (1757), featured a decorative scheme of trompe l’oeil painted bam-boo that covered its ceiling, door and window frames, and wall shelves, which, along with niches carved into the room’s lateral walls, were used to display the Duchess’s collection of porcelain.34 Aside from these exotic surface motifs, the dairy’s layout echoed that of other ornamental dairies, with a central table and waist-high shelves—usually made of slate or marble—that wrapped around the walls of the room and were used for the storing and displaying of milk products. This layout originally derived from working dairies, but it also recalls the design of the room in the “Tea-Table” engraving, which similarly depicts a central table and a niche for displaying porcelain. The Woburn dairy, however, contrasts with the tea-table by proposing an alternative venue for female congress, one that is imagined to be virtuous and domestic rather than self-interested and insalubrious.

Conspicuous consumption is not always driven by a desire to flaunt one’s status or emulate one’s social betters. As the orna-mental dairy illustrates, consumption also played a vital role in the construction and representation of identity.35 To be sure, there was an element of competition among elite dairy patrons to demonstrate their cultural awareness to their peers, but dairies also indulged the fantasy of transposing self and other that has been linked to the eighteenth-century practice of masquerading. Historians such as Terry Castle and Catherine Craft-Fairchild have debated the extent to which female participants in masquerade

34 Dorothy Stroud, Henry Holland, His Life and Architecture (London: Country Life, 1966), 112. A description of the Woburn dairy’s interior from the early nineteenth century appears in Prince Pücker-Muskau, Hints on Landscape Gardening (London, 1834); the author reports it as being “decorated with a profusion of white marble and coloured glasses; in the centre is a fountain, and round the walls hundreds of large dishes and bowls of Chinese and Japanese porcelain of every form and colour, filled with new milk and cream (205–9).”

35 A number of historians have critiqued the theory of consumer emulation most often associated with Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899). Some of these critiques are discussed by Vickery in The Gentleman’s Daughter, 163–64.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

374

balls, as they were represented in eighteenth-century art and liter-ature, exercised a subversive sense of freedom, self-exploration, and agency through the roles that they assumed (the exotic sultana, the bawdy old lady, or the rustic milkmaid, for example), or whether, by adopting these roles, they conformed to prescriptive categories of gender, class, and sexual difference.36

This question seems to have been one that ornamental dairy patrons themselves asked. By commissioning these buildings, elite women appeared to endorse an idealized vision of domesticated femininity. They imbued this vision, however, with an element of theatricality and playfulness that other members of their social group may have recognized and admired. Ornamental dairies allowed elite women patrons to incorporate new constructions of femininity while simultaneously, and perhaps subversively, making these constructions distinctly their own. Certainly, such patrons were transgressive in bringing elements of theatricality and performance into their homes and country estates—venues that were envisioned, by Addison and others, to be sites of a virtuous and authentic femininity.

Interior “character” in Ornamental Dairies

One of the unique features of the ornamental dairy’s design was that it often juxtaposed an exaggeratedly rustic exterior with a luxurious and well-appointed interior. This aesthetic disjunction provoked a pleasurable frisson in the dairy’s visitors and constituted a deliberate violation of the architectural doctrine of decorum, which stipulated that a building’s exterior should appropriately reflect its function and the social status of its patron. Decorum was first described by Vitruvius in the first century BC, and it became an important category in the Renaissance when it was conceived as an “ethical principle.”37 In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French architectural theory, writers translated Vitruvius’s

36 Terry Castle, Masquerade and Civilization: The Carnivalesque in Eighteenth-Century English Culture and Fiction (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986); Catherine Craft-Fairchild, Masquerade and Gender: Disguise and Female Identity in Eighteenth-Century Fictions by Women (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1993).

37 Peter Kohane and Michael Hill, “The Eclipse of a Commonplace Idea: Decorum in Architectural Theory,” Arq: Architectural Research Quarterly 5, no. 1 (2001): 66.

M a r t i n

375D

ecorconcept into bienséance or convenance (“fitness” or “suitability”), which, in relation to a building’s patron, were preoccupied almost exclusively with the expression of social rank or station. This obsession with class was echoed in Jacques-François Blondel’s definition of architectural “character” (caractère) in his Cours d’architecture (1771–77), which provided an extensive taxonomy of building types and decorative styles—based on the architectural orders—that reflected the rigidly hierarchical society for which it was built. These theoretical concepts exerted a strong influence on eighteenth-century British architects and dairy designers like Robert Adam and John Soane.

Around the same time, a new theory of architectural character was put forth, reflecting on how buildings or rooms could express the emotional states of their owners and inhabitants. This alternative conception of character, which received its most sustained theoretical consideration in Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières’s The Genius of Architecture, or the Analogy of that Art with Our Sensations (1780), was inspired by empiricism and sensationalist philosophy, which emphasized the effect of spatial environments on the psychological constitution of the individual, whether for good or for ill.38 Soane owned several copies of Le Camus’s text and translated a portion of it in 1808 while preparing for the Royal Academy lectures.

This new understanding of architectural character explored how buildings could produce emotional responses and behaviours in those who encountered them, resulting in a new appreciation for architecture’s role in shaping identity. Whereas earlier accounts of decorum, and even Blondel’s description of character, had been concerned primarily with the façade as an outward expression of social status, Le Camus gives equal attention to interiors, and to the question of interiority, in his treatise.

As for how an interior might mould character, Le Camus sometimes attributes this expressive capacity to the object itself, other times to the dynamic, interdependent relationship between a room and its patron. Describing a series of rooms within a

38 Nicolas Le Camus de Mezières, The Genius of Architecture, or the Analogy of that Art with Our Sensations, trans. David Britt (1780; Santa Monica: The Getty Center, 1992). References are to this edition. See also Robin Middleton’s excellent introduction to this volume, 17–64.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

376

French hôtel, Le Camus deliberately blurs the boundaries between architecture and inhabitant. This is especially pronounced in his description of a woman’s boudoir—which he defines as an animate, sensual realm, an “abode of delight”—where “she” (and it is not entirely clear whether Le Camus is referring here to the patron, or to the room itself) “seems to reflect on her designs and to yield to her inclinations” (115). Ultimately, this melding of space and subject had an impact not only on architecture and interior design, but also on the construction of space in the contemporary novel. In La Nouvelle Héloïse, for example, Rousseau describes Julie’s dairy as an ideally productive, pristine space that is meant to reflect and guarantee the heroine’s own virtue and fertility.39

Eighteenth-century architectural books understandably empha-size the roles that buildings themselves play in the articulation of character. But in his treatise Le Camus also describes how patrons manipulate character in order to communicate their interiority to visitors.40 Unfortunately, architectural treatises have little to say about how the specific building type of the dairy could express the character of its patron. In Cours d’architecture, Blondel writes that dairies are places “where ladies go to drink milk, churn better, and make cheese in order to relax and refresh themselves after rustic amusements,” but apart from this there are few theoretical accounts of this building type relative to its appearance in novels, travel accounts, and other printed sources.41 The omission is curi-ous given the celebrity of the architects who designed dairies in this era—among them Ange-Jacques Gabriel and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux in France, and William Chambers and John Nash in England—and the fact that dairies provided a vital means of experimenting with new styles, layouts, and building materials.

One can, however, approach this question by examining the dairies that John Soane designed for two important women patrons: Elizabeth Berkeley, Lady Craven (1750–1828), and Elizabeth Yorke (née Lindsay), Lady Hardwicke (1763–1858).

39 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse, trans. Philip Stewart and Jean Vaché (1761; Hanover, Dartmouth College, 1997), 371–73. References are to this edition.

40 This is especially notable in Le Camus’s description of the apartment of a magistrate, 128.

41 Jacques-François Blondel, Cours d’architecture (Paris: Desaint, 1773), 4:68.

M a r t i n

377D

ecorIndeed Soane got his start as an architect by designing dairies and garden structures for elite women clients beginning around 1780, after he had returned to England from studying in Italy.42 Two years earlier, he had published his first book, Designs in Architecture, which comprised thirty-seven engravings of garden buildings and other ephemeral structures. One of these, a “Dairy House in the Moresque stile,” depicted a fancifully exotic dairy decorated with minarets, bovine-shaped urns, and a freestanding statue of a cow over the entrance.43 The book’s whimsical drawings likely captured the attention of Elizabeth Craven, the daughter of a distinguished military officer who made her own mark on society as an amateur playwright, travel writer, and diarist. Around 1776, Lady Craven demonstrated her interest in rustic architecture by commissioning a cottage orné on the banks of the Thames near London. She financed most of the building herself through lottery winnings. Nearly a decade before the construction of Marie-Antoinette’s hamlet at Versailles, Lady Craven entertained guests at this cottage who shared her aesthetic fascination with la vie champêtre, among them Horace Walpole and Lady Mary Coke.44

Lady Craven embraced rustic architecture not simply out of a wish to be fashionable—though she was certainly ahead of her time in this regard—but also because it was the style best suited to her carefully constructed image as a model English housewife, domestic goddess, and woman of natural sensibility. It became especially important for Lady Craven to emphasize these

42 Soane’s trip to Italy is discussed in Du Prey, “John Soane, Philip Yorke, and Their Quest for Primitive Architecture,” in National Trust Studies (London, 1979), 28–38. Du Prey notes that Soane met Lady Hardwicke’s husband Philip Yorke, 3rd Earl of Hardwicke, while the two men were exploring the ruins of Paestum in southern Italy. It is unclear how Soane first came to the attention of Lady Craven, but it may have been through Soane’s employment with the firm of Henry Holland and “Capability” Brown, who worked on Craven’s country estate at Benham. See Du Prey, John Soane: The Making of an Architect (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 98.

43 Du Prey, John Soane, 89; for an illustration of Soane’s “Moresque” dairy, see 94.

44 Horace Walpole, The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, ed. W.S. Lewis (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937–83), 41:404. References are to this edition. Craven Cottage is also discussed in Du Prey, “Queen of Curds and Cream: Ornamental Dairies and Their Owners,” Country Life 181 (12 March 1987): 104. Craven Cottage has been destroyed but was situated on the present-day site of the Fulham Football Club.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

378

attributes when she scandalously separated from her husband in 1780, which eventually led to her self-imposed exile from bon ton society.45 In the following year, surely out of a desire to maintain an important social connection, Craven hired Soane to draw up plans for garden seats and pavilions that she gave to one of her society friends, Lady Penelope Pitt-Rivers.

Lady Craven also had Soane create two nearly identical designs for a rustic dairy in a natural setting. Though neither design was built, they both featured thatched roofs and a simple façade with a pediment supported by four “columns” made from tree trunks and decorated with floral garlands and vines. Both were inspired by Marc-Antoine Laugier’s model of the “primitive hut” as described in his 1753 treatise Essai sur l’architecture, and as illustrated in the book’s 1755 English edition, several copies of which Soane owned.46 Shortly thereafter, Soane reused this same design in a watercolour rendering of a thatched dairy that he built in 1783 for Lady Elizabeth Hardwicke at Hammels, her estate in Hertfordshire (see figure 2). Soane’s elevation view of the Hammels dairy depicts a façade framed by rustic garden benches and picturesque plumes of smoke that float from sketched-in chimneys on either side of the building. Inside the dairy were stained-glass windows, a vaulted ceiling, and marble tables, elegant additions that depart from Soane’s designation of the structure as “a dairy in the primitive manner of building.”47

Lady Hardwicke, who, like Lady Craven, was also an amateur playwright and society figure, was married in 1782. Soane’s dairy was likely given to her by her husband as a first anniversary present. Many ornamental dairies were presented to women soon after they were married, not unlike the gift of an engagement portrait. Engagement portraits were idealized depictions of young women on the verge of matrimony, often celebrating their 45 Although what transpired to end the marriage is unclear, rumours circulated

at the time that Lady Craven had been having an affair. As Walpole wrote to Horace Mann in October 1785, “She has, I fear, been infinitamente indiscreet—but what is that to you or me?” (25:611).

46 As Du Prey has pointed out, Soane’s dairy design for Lady Craven is quite close to the illustration of Laugier’s hut in the 1755 English edition, right down to the use of “prehistoric” tree trunks instead of columns. Soane may have also been inspired by William Chamber’s depiction of a primitive hut in his 1759 Treatise on Civil Architecture (Du Prey, John Soane, 248).

47 This phrase appears on the bottom left-hand corner of the drawing.

M a r t i n

379D

ecor

worthiness as future wives and mothers. A notable example of this genre is Joshua Reynolds’s 1770 portrait of Sophie Pelham (née Aufrère), the daughter of a wealthy London banker who sat for her portrait in the artist’s studio around the time of her wedding (see figure 6).48

In Reynolds’s painting, Sophie Pelham is dressed in a fashion-able Brunswick cotton frock, scattering seeds to a family of chickens in a rustic landscape animated by thatched farm build-ings. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1774, the portrait, now titled Mrs Pelham Feeding Poultry, was also displayed at the

48 David Mannings, Sir Joshua Reynolds, vol. 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 370.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

Figure 6. Mrs Pelham Feeding Poultry (1770), by Joshua Reynolds (1723–92). Private collection. Reproduced by permission.

380

Pelham country estate of Brocklesby Park in Lincolnshire, where an ornamental dairy, outfitted by Wedgwood, was constructed for Mrs Pelham shortly after her marriage.49 It is impossible not to detect an element of wry humour in this eighteenth-century allegory of a “mother hen,” one that members of this young urbanite’s social circle might have been expected to appre-ciate. As an allegory, it speaks of the sitter’s ability to retire to the countryside and become a good wife and mother, while also maintaining a degree of detachment from this domestic persona.

Engagement portraits may have helped prepare or “socialize” women for certain roles, to borrow Bermingham’s term. Did ornamental dairies perform a similar function? Soane’s project for the Hammels dairy emphasizes the aesthetic appeal of this building type and its longstanding associations with pastoral abundance, women, and the pleasures and comforts of domesticity. By link ing this dairy to the idea of the primitive hut, theorized by Laugier as a generative model for architecture’s origins, Soane provides a fabled lineage and an imprimatur of naturalism to the site and the activities performed there. Rhetorical constructions of femininity in this period similarly summoned the language of naturalism to persuade women that they should feel a certain way, and that they should want to perform a certain social role. Their influence is evidenced by the number of women who embraced this domestic model in the eighteenth century and in the century to follow.

Le Camus’s treatise suggests that the architect is responsible for creating a sensual environment for self-expression through design, decoration, and program. Soane attempted this at Hammels in his rustic decorative scheme, while also providing for programmatic functions within the dairy’s interior, including a space in which to consume healthful fruit and cream. According to his account books, Soane also purchased novels for Lady Hardwicke, including Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther and a novel by Frances Burney—perhaps his client read these sensible texts while lounging in the strawberry room that he designed for her.50 There is frustratingly little firsthand account of what Lady Hardwicke actually did in her dairy, although we do know

49 Kelly, 121. For a photograph of this dairy’s interior, see Kelly, figure 58.50 Du Prey, “John Soane, Philip Yorke,” 30.

M a r t i n

381D

ecorthat she and Soane continually updated the building and that, several years later, she commissioned designs for a second dairy at Wimpole Hall, another Hardwicke property. Soane delivered these designs to her in 1795, two years after he had also sent her plans for workers’ cottages and a Sunday school to be built on the Wimpole grounds. For the next two decades, Lady Hardwicke and Soane continued to exchange letters—now in the Soane archives—about architectural embellishments at Wimpole and elsewhere. These attest to Lady Hardwicke’s considerable knowledge of architectural planning and design and her use of architecture to fashion a role for herself as the domestic doyenne of her husband’s estates.51

Architects could not always control the ways in which patrons used their dairies or visitors responded to them. Indeed, eighteenth-century representations of dairies suggest that the reaction was sometimes the opposite of what was intended. In Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Héloïse, for instance, Julie’s dairy provokes Saint-Preux to feel lustful—hardly the sense of virtuousness it was supposed to elicit (372). Moreover, patrons sometimes used ornamental dairies to stage a culturally valorized masquerade that was not necessarily meant to reflect their inner “character.” Such performances privileged ambiguity over authenticity, an idea made explicit once visitors advanced beyond a dairy’s rustic façade and entered a luxurious, elegant interior outfitted for pleasure rather than use with expensive porcelain wares.

Although Lady Craven never built the dairy that Soane designed for her, her memoirs suggest that she used this building type as a theatre in which to construct a personal mythology and perform the role of a domesticated woman. At the beginning 51 The Soane Archives holds numerous references to Lady Hardwicke. An

entry from Journal 1 dated 1 November 1786 reports that Soane “sent Lady Eliza sketches for fences to front the dairy” (162), which suggests that the two continued to embellish the building after it was completed. Their correspondence regarding Wimpole is detailed in Journal 2, for example in a notation dated 4 July 1795, where it is reported that “Mr Soane took to her Ladyship n. 7 drawings,” including “5 plans and elevations of designs for a dairy.” Letters written by Lady Hardwicke and addressed to Soane are contained in a folder labeled “Correspondence with the Earl of Hardwicke.” In one of these, dated 12 April 1816, Lady Hardwicke discusses Soane’s proposal of a church and writes, “the plan for the church is not quite of my mind—I confess I should like to see some other ideas however slightly drawn—the large arch with the two smaller ones ... please my eye.”

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

382

of her memoirs, she writes of being cared for as a child by a Swiss governess, who instructs her in the duties of housewifery, including how to manage a dairy.52 The lessons proved useful years later when, in the wake of her marital separation, Lady Craven was obliged to leave England for France, leaving all but one of her seven children behind. Residing in a country house outside Paris around 1783, Lady Craven writes of how she continued to embrace the duties of a proper English housewife: “I found much pleasure in my rural amusements at my pavilion. I had cows and a fine dairy: the dairy was situated on the side of the court opposite the entrance-gate” (1:115). She also recounts how these activities attracted the attention of the French queen, Marie-Antoinette, and her sister-in-law Madame Élisabeth, who sent a spy to observe Lady Craven’s dairying activities and then asked her to come live with them at Versailles, so that they might “forget, in the charms of my society, the forms and falsehood of courtiers” (1:96). To hear the Englishwoman tell of it, Marie-Antoinette’s infamous dairy and hameau, which were built in the mid-1780s in the gardens of Versailles, were entirely Lady Craven’s idea.

After her time in France, Lady Craven traveled throughout Europe and visited Russia and Turkey, following in the footsteps of another adventurous eighteenth-century woman, Mary Wortley Montagu. Lady Craven’s travel account was published in 1789 as Journey through the Crimea to Constantinople. She also conducted an affair with the Margrave of Anspach (a nephew of Queen Caroline), once again causing a scandal given her dimin-ished social status as an exiled divorcée. Lady Craven recounts in her memoirs how, while living with the margrave and his then-wife in Anspach in the late 1780s, she renovated a dairy on the grounds of the estate, and taught the margrave’s servants “the art of making cheese or butter” using English principles and recipes, so that her host might be provided with “good cream, and Stilton, or Berkeley hundred, made under my direction” (1:189–90). She also supervised the renovation of a theatre so she could stage plays that she herself wrote. During the time that she was living in Anspach, Lady Craven advertised her domestic and intellectual pursuits in letters to friends like Horace Walpole,

52 Memoirs of the Margravine of Anspach, Written by Herself (London: Henry Colburn, 1826), 1:15. References are to this edition.

M a r t i n

383D

ecoralthough Walpole, who often lampooned her writing abilities, poked fun at her attempt to “[blend] the dairy with the library.” In a letter of June 1788 written to his cousin Thomas, Walpole remarked sarcastically, “We have hen-novelists and poetesses in every parish, and Lady Craven might institute a whole academy of her own gender.”53

Lady Craven later married the margrave and, after his death in 1806, retired to Italy, where she established another dairy in Naples stocked with Devonshire cows. Here again she followed the lead of Lady Montagu, who in the late 1740s had settled in Italy and built a rustic “Dairy House,” playing the role of a bonne bourgeoise to the delight of local residents: “I expect immortality from the science of butter-making,” Lady Montagu wrote self-mockingly to Lady Bute in 1748, “in which [the local residents have] become so skillful from my instructions.”54 These pastoral sites provided Lady Montagu and Lady Craven with a sense of home, a pride of place in a foreign land. But the sites also enabled these women to adopt a veneer of respectable femininity while challenging the restrictions of space and identity that were established for their sex in this period.

In ornamental dairies, elite women both incorporated and sub-verted the ideology of domesticity. In her essay “Womanliness as a Masquerade,” the psychoanalytic theorist Joan Rivière ob-serves that “The reader may now ask how I define womanliness or where I draw the line between genuine womanliness and the ‘masquerade.’ My suggestion is not, however, that there is any such difference; whether radical or superficial, they are the same thing.”55 One problem with many subsequent writings on masquerade is that they seem to imagine an authentic self that 53 Walpole, 36:251.54 Mary Wortley Montagu, Complete Letters, ed. Robert Halsband (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1965–67); letter dated 19 June 1751. In Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), Isobel Grundy recounts how Lady Mary “wished she could send the produce of her farming to England” in the form of gifts or commodities for sale, presumably to offer further evidence of her georgic activities (494). In a 1748 letter Montagu describes decorating her dairy and notes how she “strewd the floor with Rushes, cover’d the chimney with moss and branches ... and put in some straw chairs and a Couch Bed, which is my whole furniture” (492).

55 Joan Rivière, “Womanliness as a Masquerade” (1929), reprinted in Formations of Fantasy, ed. Victor Burgin, James Donald, and Cora Kaplan (London: Methuen, 1986), 38.

O r n a m e n t a l D a i r y T r a d i t i o n

384

exists somewhere underneath—and independent of—its out-ward expression. But the phenomenon of the ornamental dairy suggests that architects and patrons had an altogether different understanding of the relationship between subjects, objects, and spaces in the late eighteenth century. Subjectivity in the modern era may be characterized by a desire “to imagine the self and the world in terms of representation,” but the splitting, or duality, that this process evokes is never stable. Ornamental dairies may have allowed elite women to construct new forms of interiority, but the dairy was never “a room of one’s own,” a place where women were sealed off from their era’s social pressures and expectations. Rather, ornamental dairies embody the creativity and ingenuity with which an elite group of women confronted these issues. The artifice of the faux dairy became a form of reality in itself, an arena in which women could both conform to, and liberate themselves from, ideals of domestic femininity. Life intruded on the theatre they created in this space, and theatricality, in turn, informed the lives they led.

Wellesley College

M a r t i n