INDIAN LAW REPORTS DELHI SERIES 2012

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of INDIAN LAW REPORTS DELHI SERIES 2012

INDIAN LA W REPORTSDELHI SERIES

2012(Containing cases determined by the High Court of Delhi)

VOLUME-6, PART-I(CONTAINS GENERAL INDEX)

EDITORMS. R. KIRAN NATH

REGISTRAR VIGILANCE

CO-EDITORMS. NEENA BANSAL KRISHNA

(ADDITIONAL DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE)

REPORTERS

MR. CHANDER SHEKHAR MS. ANU BAGAIMR. TALWANT SINGH MR. SANJOY GHOSEMR. GIRISH KA THPALIA MR. KESHAV K. BHATIMR. VINAY KUMAR GUPTA JOINT REGISTRAR

MS. SHALINDER KAURMR. GURDEEP SINGHMS. ADITI CHAUDHAR YMR. ARUN BHARDWAJ(ADDITIONAL DIS TRICT

& SESSIONS JUDGES)

PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIGH COURT OF DELHI,

BY THE CONTROLLER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI-1 10054.

I.L.R. (2012) 6 DELHI Part-I (November, 2012)

(Pages 1-446)P.S.D. 25.11.2012

600

PRINTED BY : J.R. COMPUTERS, 477/7, MOONGA NAGAR,

KARAWAL NAGAR ROAD, DELHI-1 10094.

AND PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIGH COURT OF DELHI,

BY THE CONTROLLER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI-1 10054—2012.

Annual Subscription rate of I.L.R.(D.S.) 2012(for 6 volumes each volume consisting of 2 Parts)

In Indian Rupees : 2500/-Single Part : 250/-

for Subscription Please Contact :

Controller of PublicationsDepartment of Publication, Govt. of India,Civil Lines, Delhi-110054.Website: www.deptpub.nic.inEmail:[email protected] (&) [email protected].: 23817823/9689/3761/3762/3764/3765Fax.: 23817876

Oil India Limited v. Essar Oil Limited..................................................222

Omaxe Ltd. & Ors. v. Roma International Pvt. Ltd..............................76

Prabhash Sharma & Anr. v. State............................................................1

Prem Raj v. Babu Ram Gupta & Others.............................................293

Rajesh Kumar Meena v. Commissioner of Police & Ors....................254

Ramesh Jaiswal v. Semjeet Singh Brar & Ors....................................212

Ramesh Kumar v. Mohd. Rahees & Ors..............................................72

Ravinder Prakash Punj v. Punj Sons Pvt. Ltd.. & Ors........................321

Ravi Shankar Sharma v. Kali Ram Sharma and Ors............................338

S.C. Bhagat & Anr. v. UOI & Anr. ......................................................147

S.K. Seth & Sons v. Vijay Bhalla........................................................139

Sat Bhan Singh & Anr v. Mahipat Singh & Ors..................................262

Shantanu Acharya v. Whirlpool of India Ltd.......................................358

Sheenam Raheja v. Amit Wadhwa.......................................................343

Shree Rishabh Vihar Cooperative House Building SocietyLtd. v. Salil Richariya & Ors.........................................................163

Social Jurist, A Civil Rights Group v. Govt. of NCT of Delhi...........308

Sushil Jain v. Meharban Singh & Ors.................................................186

Suresh Srivastava v. Subodh Srivastava and Ors................................272

(ii)

(i)

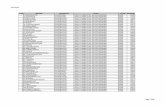

NOMINAL-INDEXVOLUME-6, PART-INOVEMBER, 2012

Amarjeet Singh v. The Management of National ThermalPower Corporation Ltd..................................................................441

Amish Jain & Anr. v. ICICI Bank Ltd.................................................377

Anand Burman v. State.........................................................................152

Asha Rani Gupta v. Rajender Kumar & Ors........................................283

B.R. Grover v. The State.....................................................................127

Bhagwan Dass & Ors. v. State...........................................................114

D.V. Chug v. State & Anr....................................................................81

Harsh Vardhan Land Limited v. Kotak Mahindra BankLimited & Ors................................................................................413

Hindustan Vegetable Oil Corporation Ltd. v. GaneshScientific Research Foundation....................................................368

IFFCO Tokio General Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Babita & Ors................206

The Indian Performing Right Society v. Ad VentureCommunication India Private Limited...........................................426

J.K. Synthetics Ltd. v. Dynamic Cement Traders...............................398

Janak Raj v. State NCT of Delhi & Ors...............................................158

K.K. Sareen and Ors. v. Neeta Sharma and Ors..................................405

K.V. Kohli Through Lrs. v. State...........................................................93

Kulvinder Singh v. Harvinder Pal Singh & Anr....................................108

Lalita Parashar & Anr. v. Ranjeet Singh Negi & Ors..........................119

Mohd. Jafar & Ors. v. Nasra Begum...................................................104

SUBJECT-INDEXVOLUME-6, PART-INOVEMBER, 2012

ADMINISTRA TIVE LA W—Consequential Benefits—Issueinvolved, whether the direction given by the CentralAdministrative Tribunal holding that petitioners would beentitled to all consequential benefits from the date ofregularization would include payment of arrears of pay, afterfixation of pay in the regular pay scale, from the Hon’bleSupreme Court in the case of Commissioner of Hon’bleHousing Board vs C. Muddaiah, AIR 2007 SC 3100, theanswer has to be in affirmative and consequential benefitswould include past wages as well.

S.C. Bhagat & Anr. v. UOI & Anr. ..........................147

ARBITRA TION AND CONCILIA TION ACT, 1996—Sections4, 14, 34—ICA Rules—Rules 58, 63—Submission was thatimpugned Award was delivered more than three years after itwas reserved and extraordinary delay by itself rendered itcontrary to public policy of India—Held, it cannot be laid downas an inviolable law that irrespective of facts andcircumstances of a case, if there is delay in pronouncing anAward, then it should be set aside—Thus, as a party continuedto participate in arbitral proceedings beyond period of twoyears without objecting to delay beyond two years in itscompetition and majority Award deals with each of issues dealtwith by dissenting Award, it cannot be said that delay inpronouncement of Award rendered it patently illegal oropposed to public policy of India.

Oil India Limited v. Essar Oil Limited.......................222

— Limitation Act, 1963—Article 136—Appellant filed executionpetition seeking execution of decree passed by Court, whilemaking an award rule of court—Execution petition dismissedbeing not maintainable—Aggrieved appellant challenged theorder—Respondents raised one of the objections that executionpetition was barred by limitation and merely because appealagainst dismissal of objections was pending, without therebeing a stay, (which was also dismissed.) limitation for

preferring execution petition did not stop to run on the dateon which award was made rule of Court. Held:—The periodof limitation for execution begins from the date of decisionof the Appellant Court in a case when the decree of the LowerCourt is challenged in Appeal as the original decree merges inthe appellate decree.

Ravinder Prakash Punj v. Punj Sons Pvt. Ltd..& Ors..............................................................................321

CODE OF CIVIL PROCEDURE, 1908—Order IX, Rule 13—In proceedings under Section 163A, Motor Vehicles Act, theappellant being owner of the offending vehicle filed the writtenstatement but thereafter, stopped appearing and was proceededexparte leading to exparte award against him—Appellantmoved application under Order IX Rule 13 alleging that hewas informed by his counsel that appellant need not come tocourt and counsel would keep track of the matter and on beingagain contacted, the counsel told him that Insurance Companywould do the needful and subsequently, appellant receivednotice of recovery—MACT dismissed the application—Hencethe appeal—Held, after filing the written statement the appellantstopped appearing and the matter was listed on four dates afterwhich the appellant was proceeded exparte, though someproxy counsel appeared but no evidence was led despiteopportunity—Held, conduct of appellant shows that he wasnot vigilant in pursuing the matter, no infirmity in the orderof MACT.

Ramesh Kumar v. Mohd. Rahees & Ors......................72

— Order 8, Rule 1—Limitation Act, 1963—Section 5—Constitution of India 1950—Article 227—Copy of suit forrecovery was served on 17th August, 2010—Though on 1stNovember 2010, petitioners appeared, but WS was not filed—Thereafter, matter was adjourned on few dates and it was onlyon 4th February, 2011 that petitioners filed an applicationunder section 5 of Limitation act r/w section 148 and 151 ofCPC seeking condonation of delay in filing written statementmainly on ground that petitioners were involved in constructionof various sites and the documents pertaining to this case werenot traceable and could only be traced after much efforts—Itwas also averred that it took some time to requisition the

(iv)

(iii)

relevant documents and on receipt thereof the same were sentto their counsel for preparing WS and in the process, the filingof WS got delayed –Said application was dismissed and reviewagainst said order was also dismissed—Held in instant case,plea that was taken that documents were misplaced at somesite and could be traced only after many efforts, is apparentlyvague and irresponsible—Similar is plea that documents weregiven to counsel who took some time to prepare WS—Inbackdrop of mandatory provision of law regarding filling ofWS, pleas taken for seeking condonation are extremely vagueand devoid of any merit.

Omaxe Ltd. & Ors. v. Roma International Pvt. Ltd... 76

— Order XIV Rule 2 (2) (b)—Respondent No. 2/objector soughtdirections that Issue No. 2 as to whether the legalrepresentatives of late Sh. K.V. Kohli had no right to prosecutethis petition, be decided as preliminary issue—On the day whenissues were framed, no request was made to treat Issue No.2 as preliminary issue—Held, what falls Order 14 Rule 2 (2)(b) CPC are those bars by which the court is prevented/barredto decide the merits of the matter and where the issue requiresevidence, it cannot be treated as a legal issue and therefore,cannot be treated as preliminary issue—in view of factualmatrix of the case, Issue No. 2 need not be treated aspreliminary issue in so far as it does not fall within theintendment of "bar of suit created by law" used in theprovision.

K.V. Kohli Through Lrs. v. State...................................93

— Section 151—Order 7 Rule 1 (A) & Order 6 Rule 17—Plaintifffiled suit for partition—After completion of pleadings,defendant no. 1 moved two applications one seeking permissionto place some additional documents and other for amendmentto written statement—As per defendant no. 1, Court ought tobe liberal in granting prayer for amendment of pleadings unlessserious injustice or irreparable loss is caused to other side—Applications strongly opposed by plaintiff. Held—Amendmentto the written statement stands on a different footing fromthe amendment to the plaint. Though amendment to pleadingscannot be permitted so as to materially alter the substantial

cause of action in a plaint, there is no such principle that canbe applied to amendment in the written statement. Therefore,it is permissible for the defendant to take inconsistent pleas,mutually contrary pleas or to substitute the original plea takenin the written statement.

Kulvinder Singh v. Harvinder Pal Singh & Anr.......108

— Order 2 Rule 2—Order 7 Rule 11—Plaintiffs filed suit seekingpartition, declaration and permanent injunction—Defendant no.1 moved application U/O 7 Rule 11 seeking rejection of plainton ground that plaintiff had filed another suit claiminginjunction but did not claim relief of partition in that suit,therefore, present suit for partition of very same property notmaintainable. Held—If the course of action mentioned in theearlier suit afforded a basis for a valid claim, but did not enablethe plaintiff to ask for any relief other than those he prayedfor in that suit, the subsequent suit would not be barred underOrder 2 Rule 2.

Sat Bhan Singh & Anr v. Mahipat Singh & Ors......262

— Order 12 Rule 6—Limitation Act, 1963—Article 59—SpecificRelief Act, 1963—Section 31—Plaintiff filed suit seekingpartition of suit property situated in Vivek Vihar, New Delhii—Defendant no. 2, brother of plaintiff and defendant no. 1moved application u/o 12 Rule 6 Plaintiff supported theapplication whereas defendant no. 1 contested the same—Asper plaintiff, he, defendant no. 2 and defendant no. 3 (thefather) had entered into agreement recording that property wasjoint property of all the parties—Said agreement was followedby family settlement stating that all parties had 1/4th share insuit property and an affidavit of defendant no. 1 of same dateto same effect—Defendant no. 1 did not deny execution ofsaid documents but alleged misrepresentation and legalineffectiveness of documents which required trial and couldnot be disposed of by applying provisions of Order 12 Rule6. Held—There are two types of documents; one is void andsecond is voidable documents. For void documents, any suitfor cancellation u/s 31 of Specific Relief Act is not requiredto be filed—whereas voidable documents have to be cancelledas per Section 31 of the act and a suit could be filed within 3

(v) (vi)

defendant that proceedings initiated by defendant fordissolution of marriage between them on ground ofirreconcilable differences pending before Superior Court ofCalifornia, U.S was illegal, invalid and void ab-initio—Duringpendency of suit, however, decree for dissolution of marriagewas passed by Superior Court of California and thus, plaintiffamended the plaint to seek appropriate orders declaring orderor dissolution of marriage as null and void and non-est in eyesof law—As per plaintiff, the parties were married accordingto Hindu rites and ceremonies at New Delhi and two femalechildren were born out of their wedlock—Their marriage raninto troubled waters on account of cruelty inflicted upon herby defendant and his relatives—Plaintiff became unwell andcame to India along with her two children—Mother-in-law ofthe plaintiff clandestinely took away the children to U.S. andplaintiff was forced to live with her parents as her matrimonialhome in New Delhi was locked by her mother-in-law-Plaintiffcame to know through close relatives of parties that defendanthad filed proceedings before a Court in U.S. and on checkingwebsite of Court, she came to know about the case fordissolution of marriage; thus plaintiff initiated present suit inDelhi. Held—The first and foremost requirement ofrecognizing a foreign matrimonial judgment is that the reliefshould be granted to the petitioner on a ground available underthe matrimonial law under which the parties were married,or where the respondent voluntarily and effectively submitsto the jurisdiction of the forum and contests and claim whichis based on a ground available under the matrimonial law underwhich the parties are married.—Plaintiff did not contest theclaim nor agree to the passing of decree—Decree ofdissolution of marriage passed by superior court of Californiaheld to be null and void and not enforceable in India.

Sheenam Raheja v. Amit Wadhwa..............................343

— Order 37—Summary Suit filed by the plaintiff/Respondentseeking recovery from Defendant who was distributor of itsproducts—Leave to Defend pleading lack of territorialjurisdiction filed by the Defendant—The Trial Court declinedthe Leave to Defend on the ground that the Application seekingLeave to Defend was neither signed by the Defendant norsupported by any Affidavit—Held, that Order 374 Rule (5)

(vii) (viii)

years as per Article 59 of Limitation Act.

Suresh Srivastava v. Subodh Srivastava and Ors.......272

— Order 39 Rule, 1, 2 & 4—Plaintiff instituted suit seekingpermanent and mandatory injunction against defendantsaverring plaintiff was owner of commercial and residentialproperty—His father-in-law had let out two shops out of theproperty to father of defendants—Defendants completelyencroached upon common verandah and common toilet inproperty which was meant for common use of occupants ofboth shops on ground floor as well as first floor—Acts ofdefendants had caused imminent danger to plaintiff—He alsoinitiated application seeking interim restrain orders andmandatory injunction against defendants. Held—Grant ofmandatory injunction during pendency of suit is essential andequitable relief which ultimately rests in the sound judicialdiscretion of the court to be exercised in the light of factsand circumstances in each case. No reason why plaintiffshould continue to suffer by not allowing her to have freeaccess to verandah toilet—In facts of this cause, temporarymandatory injunction granted.

Asha Rani Gupta v. Rajender Kumar & Ors.............283

— Section 2, Order 12 Rule 6—Delhi Land Reforms Act, 1985—Plaintiff filed suit for partition, possessions, rendition ofaccount, injunction etc alleging that suit properties which werevested with his grandfather, on death of his grandfather, wereinherited by him and defendant no. 1 (his father)—Defendantno. 1 raised various objections including that suit was barredby Delhi Land Reforms Act. Held—As per the provisions ofOrder 12 Rule 6 CPC, A Court is entitled to decide the suiton the basis of admitted facts at any stage—A decree as persection 2 (2) CPC includes dismissal of a suit and therefore,the provision of Order 12 Rule 6 CPC applies even fordismissal of a suit which is also called a decree.—Sinceproperties in the hand of defendants not was self acquired,suit dismissed.

Ravi Shankar Sharma v. Kali Ram Sharmaand Ors...........................................................................338

— Section 3—Plaintiff filed suit seeking declaration against

of the Code postulates that the facts soughts to be disclosedby the Defendant which entitle him to Leave to Defend neednot be on an Affidavit but should be disclosed in a mannerunder such circumstances, that a similar sanctity, probativevalue and presumption of correctness can be accorded to themby the Court—Open to Defendant to draw attention of theCourt either to the facts mentioned in the Plaint itself or evento the facts of which judicial notice can be taken as sufficientfor the grant of Leave to Defend.

Shantanu Acharya v. Whirlpool of India Ltd.............358

— Order 39 Rule 10—Transfer of Property Act, 1882—Section53A—Plaintiff Company became owner of suit property videnotification issued by Government in the year 1984, whichwas acquired by Government in the year 1972—Defendant,a Public trust created by plaintiff under name and style of M/s Ganesh Scientific Research Foundation was allowed byplaintiff to run its office in part of suit premises—However,no lease deed was executed in favour of defendant Trust—Defendant failed to vacate portion in its possession despite itwas asked to do by plaintiff and accordingly plaintiff had putits lock on there rooms and two big halls, in premises—Plaintiffs, then filed suit seeking possession of premises fromdefendant and also pressed for damaged—Plaintiff moved anapplication U/o 39 Rule 10 seeking direction for defendant todeposit charges for use and occupation of property and urged,defendant had no right to continue in possession of portionoccupied by it, without consent of plaintiff company—defendant Trust defended suit and claimed that it was lawfultenant under plaintiff and relief upon various minutes ofmeetings of Board of Trusties of plaintiff company as wellas defendant Trust—It also relied upon S-53A of Act. Held:Section 53A of Transfer of Properties Act comes into playwhen there is a contract between the parties for transfer ofany portion of suit property on leasehold or any other basis.There absolutely was no contract between the plaintiff andthe defendant for transfer of any portion of suit property eitheron leasehold or any other basis.

Hindustan Vegetable Oil Corporation Ltd. v. GaneshScientific Research Foundation...................................368

— Order 6 Rule 17—Plaintiffs had filed suit for damages andpossession of suit property against defendants—Defendantscontested vigorously suit and at time of advancement of finalarguments, they moved application seeking amendment of thewritten statement. Held:—No application for amendment shallbe allowed unless the court is satisfied that inspite of duediligence, the matter could not be raised before thecommencement of trial. The proviso to Order 6 Rule 17ofthe code put an embargo on the exercise of jurisdiction bythe Court; unless the jurisdiction fact as envisaged in theproviso is found to be existing. No amendment of plaint canbe allowed.

K.K. Sareen and Ors. v. Neeta Sharma and Ors.......405

CODE OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE, 1973—Section162(2)—Circumstantial evidence—Dying declaration—As percase of prosecution, deceased was conductor on truckbelonging to accused Prabhash—On morning of incident,deceased went to house of accused Prabhash to take wagesfor two months—Deceased compelled to drink liquor despiterefusal and thereafter beaten by accused Prabhash and othertwo accused Manoj and Jaibir—Accused Manoj picked uptwo plastic canes containing acid and poured on deceasedwhile deceased held by other two accused—Deceased becameunconscious—When gained consciousness he found himselfnaked in injured condition near his jhuggi—Brother of deceased(PW 1) took him to hospital—Accused Prabhash arrested—Two statements of deceased recorded by police constable(PW-8)—Two other accused subsequently arrested—AccusedManoj got recovered plastic cane—Deceased died after 9 daysof incident—Cause of death was pneumonia and septicemiaconsequent to burn injuries—Trial court convicted accusedPrabhash and Manoj u/s 302/34—Accused Jaibir acquitted—Held, well settled principle that dying declaration was asubstantive piece of evidence to be relied on, provided it wasproved that same was voluntary and truthful and the victimwas in a fit state of mind—Doctor examining (PW6) accuseddid not make endorsement on MLC that deceased fit to makestatement—Certificate on MLC relied upon as DyingDeclaration not scribed or signed by doctor—Author ofendorsement on MLC not produced as witness—Nothing to

(ix) (x)

not positively proved to be true, the accused would be entitledto acquittal—Appeal Allowed.

Prabhash Sharma & Anr. v. State...................................1

— Section 482—Petitioner whose prosecutions is sought to beinitiated under Sections 28/112 was working only as a managerof Indian Coffee House—Allegation against petitioner is thathe failed to produce a license for running an eating house andaccordingly, a Kalandara under Sections 28 and 112 waslodged against him—Held, it transpires that petitioner was onlya manager and he was neither owner nor proprietor ofpremises in question consequently, proceedings arising underSection 28 and 112 as well as any other proceedings arisingtherefrom against petitioner are quashed.

Janak Raj v. State NCT of Delhi & Ors...................158

— Section 340—In a civil proceedings under Sec. 340 againstthe defendant—Hon’ble Single Judge dismissed the applicationsas not maintainable-Plaintiff filed letters Patent Appeal—Respondent challenged maintainability of LPA—Held, once Sec340 is invoked, the court exercises criminal jurisdiction, evenif the main proceedings are civil in nature consequently, anorder passed on an application under Sec. 340 would be anorder passed in criminal jusridiction—Therefore, withinexceptions to Clause 10 of the Letters therefore appeal notmaintainable.

Ramesh Jaiswal v. Semjeet Singh Brar & Ors.........212

COMPETITION ACT, 2002—Section 26 (1)—On variouscomplaints being made to Registrar of Cooperative Societies(RCS), enquiry ordered under section 55 of Act—EO madehis report pointing out various irregularities in affairs ofpetitioner society—On basis of aforesaid enquiry report,Registrar constituted another enquiry under section 59 ofAct—EO gave report that Respondent No. 4 usurped powerof duly elected Managing Committee and fabricated and forgedrecords—Against first enquiry report under section 55 of Actand against second enquiry report under Section 59(1) of Act,Respondent No. 4 preferred two revision petitions undersections 80 of Act—Financial Commissioner (FC) allowedrevision petitions holding that enquiry report prepared under

(xi) (xii)

indicate that history in MLC given by patient—MLC recordedvery casually—Endorsement on MLC (Ex. PW 6/A) not adying declaration—Dying declaration (Ex. PW8/B) recordedby Head Constable PW 8 was in language which cast doubt,whether statement recorded on dictation of deceased—Medication administered to deceased not on record—No nameor indentify of person who endorsed fitness on statement Ex.PW8/B brought on record nor examined—No time ofendorsement mentioned—No evidence of fitness of deceasedwhen Ex. Pw 8/B scribed by PW-8—Second statement Ex.PW8/B not in words of deceased –No certification of fitnessor name of doctor who examined—Statement did not bearsignature or thumb impression of deceased—IO had 9 dayswhile the deceased was in hospital to get his statementrecorded by Magistrate, however made no efforts—Seriousinfirmities in statements recorded—Material contradictions withregard to time of occurrence, identify of assailants and mannerin which deceased attacked between two Dying Declaration—Events projected in Dying Declarations did not find mentionin statement of witness—Manner in which deceased receivedinjuries, doubtful—No proximity of time between statementsattributed to the deceased and his death—Contradiction instatements of recovery witnesses—No explanation about noclothes of the deceased being recovered from the spot—Notproved how deceased was transported from place ofoccurrence to site of his recovery—Controversy with regardto identify of kerosene cane recovered and delay in sendingsame for forensic examination—No arrest memo produced—Medical evidence and surrounding circumstances altogethercannot be ignored and kept out of consideration by placingexclusive reliance upon Dying Declaration—No evidence toshow that accused persons last seen with deceased—Evidencereflects failure of IO to examine eye—witnesses/publicwitnesses—In cases of circumstantial evidence, burden onprosecution is always greater—No evidence with regard tocommonality of intention to cause death—In cases ofcircumstantial evidence, inculpatory facts proved on recordmust be incompatible with the innocence of the accused andincapable of explanation—It is settled law that if there is somematerial on record which is consistent with the innocence ofthe accused which may be reasonably true even through it is

Sections 55 of Act was vitiated on account of breach ofprinciples of natural justice—Since enquiry report under section55 of Act was set aside, which is precursor to initiation ofproceedings under Sections 59(1) of Act, same too was setaside—Order challenged before High Court—Held—At stageof enquiry under Section 55 (1) of Act, there is no need forEO to issue notice to any specific individual or office bearerof cooperative society as it is general and preliminaryenquiry—It is only when Registrar decides to proceed againsta particular individual, member of office bearer or personentrusted with organization or management of society undersection 59 that a notice would be required to be issued to thatperson—Pertinently, conduct of enquiry under Section 55(1)of Act and preparation of report thereunder by itself does notresult in any civil or criminal consequence or fall out for anyreason—Even if enquiry report prepared under sections 55 (1)of Act were to suggest wrong doing by a particular personor officer of a society, Registrar may or may not accept reportand may or may not proceed further under Section 59 of Act—Principles of natural justice do not apply to enquiry conductedunder Section 55 of Act—FC had no competence to makeobservations on merits of case. Since he was dealing withrevision petition under Section 80 of Act, primarily on groundthat report under Section 55 of Act was prepared in breachof principles of natural justice—Impugned order passed byFC quashed and petition allowed.

Shree Rishabh Vihar Cooperative House BuildingSociety Ltd. v. Salil Richariya & Ors.........................163

CONSTITUTION OF INDIA, 1950 —Article 227—Copy of suitfor recovery was served on 17th August, 2010—Though on1st November 2010, petitioners appeared, but WS was notfiled—Thereafter, matter was adjourned on few dates and itwas only on 4th February, 2011 that petitioners filed anapplication under section 5 of Limitation act r/w section 148and 151 of CPC seeking condonation of delay in filing writtenstatement mainly on ground that petitioners were involved inconstruction of various sites and the documents pertaining tothis case were not traceable and could only be traced aftermuch efforts—It was also averred that it took some time torequisition the relevant documents and on receipt thereof the

same were sent to their counsel for preparing WS and in theprocess, the filing of WS got delayed –Said application wasdismissed and review against said order was also dismissed—Held in instant case, plea that was taken that documents weremisplaced at some site and could be traced only after manyefforts, is apparently vague and irresponsible—Similar is pleathat documents were given to counsel who took some timeto prepare WS—In backdrop of mandatory provision of lawregarding filling of WS, pleas taken for seeking condonationare extremely vague and devoid of any merit.

Omaxe Ltd. & Ors. v. Roma InternationalPvt. Ltd............................................................................76

— Letters Patent Appeal Clause 10—Code of Criminal Procedure,1973—Section 340—In a civil proceedings under Sec. 340against the defendant—Hon’ble Single Judge dismissed theapplications as not maintainable-Plaintiff filed letters PatentAppeal—Respondent challenged maintainability of LPA—Held,once Sec 340 is invoked, the court exercises criminaljurisdiction, even if the main proceedings are civil in natureconsequently, an order passed on an application under Sec.340 would be an order passed in criminal jusridiction—Therefore, within exceptions to Clause 10 of the Letterstherefore appeal not maintainable.

Ramesh Jaiswal v. Semjeet Singh Brar & Ors.........212

— Article 14, 15, 21, 21-A and 38—Delhi School Education Act,1973—Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities,Protection of Rights and full Participation) Act, 1995—U.N.Convention on Rights of Child (1989)—U.N. Convention onrights of persons with Disabilities (2008)—Delhi SchoolEducation (Free seats for students belonging to EconomicallyWeaker Sections and Disadvantaged Group) Order 2011—Thispetition is concerned with a direction for appointment ofSpecial Educators and for provision of requisite aids inrecognized unaided and aided private schools, Delhi—Pleataken by Action Committee, two special educators may notbe required in all schools inasmuch as all schools may noteven have children with disabilities and recognized unaidedprivate schools should be permitted to make appointments of

(xiii) (xiv)

Special Educators and provision for special aids on a needbased basis—Schools be allowed to share Special Educatorsamongst themselves—Per contra plea taken by counsel forGNCTD as well as counsel for petitioner, if such liberty isgranted, schools, without incurring expenditure on salaries ofSpecial Educators would claim reimbursement per child asbeing paid to schools who employ such Special Educators—Absence of Special Educators and other Special Provisions fordisabled in school would act as a deterrent to children withdisability seeking admission thereto and would become a viciouscycle—Special Educators can be of assistance not only tochildren with disability but to other children as well and forthis reason also it is essential for schools to have them—Held—Recognized unaided private schools as well as aidedschools are required to employ minimum of two SpecialEducators in each school and appointment of such SpecialEducators cannot be made dependent on admission of childrenneeding Special Educators—Each of such school has to haveprovision for special aids for such children and is required toprovide a barrier free movement—Absence today of any suchchildren in school, cannot be excuse for not providing suchfacilities—If existing staff/teachers in schools are surplus and/or student strength or student-teacher ratio of school sopermits, schools can have their existing staff trained to teachchildren with disability instead of engaging separate SpecialEducators—Deployment of Special Educators cannot bedeferred till admission of children with special needs andschools have to be in a state of readiness and preparednessto receive children with special needs—Capital expenditure onmaking school building and premises barrier free so as to allowfree movement to children with disability, has to be incurredby schools from their own coffers and is not reimbursableby Government—All recognized aided and unaided privateschools in Delhi directed to appoint Special Educators and tomake their buildings/school premises barrier free so as toprovide free movement/access to children with disabilities—DoE, Govt. NCT of Delhi directed to ensure compliance ofdirections issued by this Court and to take action for de-recognition against erring schools—Schools where childrenwith special needs are already admitted or will be admittedhereafter, shall immediately make provision for Special

Educators and further ordain that no school shall refuseadmission to children with disability for reason of notemploying Special Educators or not providing barrier freeaccess in school premises.

Social Jurist, A Civil Rights Group v. Govt. ofNCT of Delhi.................................................................308

— Article 14—Notice issued to petitioner asking too show causehis habitual absence—Petitioner did not dispute his absenceas detailed in show cause notice, but merely pleaded that hehad been taking leave explaining his domestic problems andsaid leave was approved without pay and ought not be treatedunauthorized absence—Another notice issued by respondentto petitioner to show cause as to why he should not bedeemed to have voluntarily absented himself from work sincemonth of October, 2007 when his leave had never beenapproved as claimed by him in earlier reply—Petitionersubmitted a reply to said show cause notice stating that leavewas taken verbally; he had applied for regularization of hisabsence in terms of circulars of year, 1997-1998 ofrespondent and he was not allowed to sign attendance registerfor last 20 months and denied he had been absenting fromOctober, 1997—Respondent vide impugned order heldpetitioner to have voluntarily left services within meaning ofRule 24.96—Order of termination challenged before HighCourt—Plea taken, Rule aforesaid is violative of Article 14 ofConstitution of India as it empowers respondent Corporationto terminate service of employee without giving anychargesheet or opportunity of being heard and without holdingany enquiry resulting in violation of principles of natural justiceand order of termination also challenged on merits—Held—In so far challenge to Rule 24.9 of NTPC services Rules isconcerned, validity of said Rule was upheld by judgment ofDivision Bench—Regularisation of leave vide circulars of year,1997-1998 was at best till issuance thereof—Even if it wereto be held that unauthorized absence of petitioner till end ofApril, 1998 stood regularized, second show cause notice wasissued after one year and appellant has been unable to showany application for leave or sanction thereof for said one year—It is inconceivable that employee who though working, is notbeing permitted to mark this attendance for one year, would

(xv) (xvi)

not take up matter—Neither any plea has been raised regardingproof of petitioner having worked during said time nor counselhas any knowledge—Petitioner has also not collected his payfrom month of October, 1997 onwards and no demandthereof was made—There is no perversity in application ofRule 24.9 qua petitioner and in deeming petitioner to haveabandoned his employment by remaining unauthorizedlyabsent from duty for more than consecutives 90 days.

Amarjeet Singh v. The Management of NationalThermal Power Corporation Ltd..................................441

COPYRIGHT ACT, 1957—Section 14, 17 & 33—Plaintiffclaimed to be Society of authors, composers and publishersof various literacy and musical works and administered publicperformances/communication to public rights under Act—Byvirtue of reciprocal contracts with other Societies, plaintiffalso claimed to be vested with public performance rights ofinternational music—Defendant alleged to be involved inorganizing live performances, songs and providing D.JS—Defendant organized live musical event wherein literary/musicalwork of plaintiff's society were communicated to publicwithout obtaining requisite license; thus, plaintiff claimedinfringement of copyright and filed out—Defendant did notcontest the suit and was proceeded ex-parte. Held—Communication of a sound recording to the public by ownerof the recording does not encroach upon the right of theowner of the underlying literary and musical work to performthe said underline works in the public—Copyright Holder ofsound recording does not have copyrights in live performancesbut a separate license from lyricist and musical composer, asthe case may be is required in case of live performances.

The Indian Performing Right Society v.Ad Venture Communication India Private Limited....426

DELHI COOPERA TIVE SOCIETIES RULES, 1973—Rules24(2)—Competition Act, 2002—Section 26 (1)—On variouscomplaints being made to Registrar of Cooperative Societies(RCS), enquiry ordered under section 55 of Act—EO madehis report pointing out various irregularities in affairs ofpetitioner society—On basis of aforesaid enquiry report,Registrar constituted another enquiry under section 59 of

Act—EO gave report that Respondent No. 4 usurped powerof duly elected Managing Committee and fabricated and forgedrecords—Against first enquiry report under section 55 of Actand against second enquiry report under Section 59(1) of Act,Respondent No. 4 preferred two revision petitions undersections 80 of Act—Financial Commissioner (FC) allowedrevision petitions holding that enquiry report prepared underSections 55 of Act was vitiated on account of breach ofprinciples of natural justice—Since enquiry report under section55 of Act was set aside, which is precursor to initiation ofproceedings under Sections 59(1) of Act, same too was setaside—Order challenged before High Court—Held—At stageof enquiry under Section 55 (1) of Act, there is no need forEO to issue notice to any specific individual or office bearerof cooperative society as it is general and preliminaryenquiry—It is only when Registrar decides to proceed againsta particular individual, member of office bearer or personentrusted with organization or management of society undersection 59 that a notice would be required to be issued to thatperson—Pertinently, conduct of enquiry under Section 55(1)of Act and preparation of report thereunder by itself does notresult in any civil or criminal consequence or fall out for anyreason—Even if enquiry report prepared under sections 55 (1)of Act were to suggest wrong doing by a particular personor officer of a society, Registrar may or may not accept reportand may or may not proceed further under Section 59 of Act—Principles of natural justice do not apply to enquiry conductedunder Section 55 of Act—FC had no competence to makeobservations on merits of case. Since he was dealing withrevision petition under Section 80 of Act, primarily on groundthat report under Section 55 of Act was prepared in breachof principles of natural justice—Impugned order passed byFC quashed and petition allowed.

Shree Rishabh Vihar Cooperative HouseBuilding Society Ltd. v. Salil Richariya & Ors.........163

DELHI LAND REFORMS ACT, 1985—Plaintiff filed suit forpartition, possessions, rendition of account, injunction etcalleging that suit properties which were vested with hisgrandfather, on death of his grandfather, were inherited byhim and defendant no. 1 (his father)—Defendant no. 1 raised

(xvii) (xviii)

eviction proceedings, petitioners tenant sought leave to defendon the grounds that the requirement set up by landlordrespondent to the effect that she needed the tenanted shop toset up business of her son was not bona fide since respondentlandlord is in possession of first and second floor, where ahusband is running a hotel and son of respondent is alreadyengaged in business of his father—Application dismissed byARC holding that there was no triable issue—challenged—Held, in view of contradiction in the contents of para 4 (ii) ¶ 4 (vii) of the reply to the application, there was definitelya triable issue regarding the alleged possession of the shops;as such impugned order not sustainable.

Mohd. Jafar & Ors. v. Nasra Begum.........................104

— Section 14 (1)(e)—Petitioner tenant sought leave to contesteviction petition on the grounds that the respondent landlorddid not have bona fide requirement of the demised premises,as respondent was in possession of a shop on ground floorof the suit property, which makes it to be a case ofrequirement of additional accommodation and that being so,petitioner tenant was entitled to leave to defend—AdditionalRent Controller dismissed the leave to defend application andpassed eviction order—Revision—Held, as per record, therespondent landlord concealed the fact of being in possessionof a shop on the ground floor and this fact was admitted byrespondent only on being confronted before the trial court,as such the trial court erred in summarily rejecting asubstantial triable issue—Also held, the factum of therespondent being in possession of alternate shop in acommercial area, essentially makes it a case of requirementof additional accommodation and in such cases leave to defendmust ordinarily be granted.

S.K. Seth & Sons v. Vijay Bhalla.............................139

DELHI SCHOOL EDUCATION ACT, 1973—Persons withDisabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and fullParticipation) Act, 1995—U.N. Convention on Rights of Child(1989)—U.N. Convention on rights of persons with Disabilities(2008)—Delhi School Education (Free seats for studentsbelonging to Economically Weaker Sections andDisadvantaged Group) Order 2011—This petition is concerned

(xix) (xx)

various objections including that suit was barred by Delhi LandReforms Act. Held—As per the provisions of Order 12 Rule6 CPC, A Court is entitled to decide the suit on the basis ofadmitted facts at any stage—A decree as per section 2 (2)CPC includes dismissal of a suit and therefore, the provisionof Order 12 Rule 6 CPC applies even for dismissal of a suitwhich is also called a decree.—Since properties in the handof defendants not was self acquired, suit dismissed.

Ravi Shankar Sharma v. Kali Ram Sharmaand Ors...........................................................................338

DELHI MUNICIP AL CORPORATION ACT, 1957—Section347, 461—Complaint filed by MCD u/s 347/461 of the Actagainst petitioner alleging change of user of property fromresidential to commercial by running Clinic of Doctor; whereasMCD had sanctioned permissible use of property asresidential—Petitioner filing of complaint urging that runningof Clinic by Doctor does not fall in commercial activity—Held:— The professional establishment of a doctor cannotcome within the definition of commercial activity. Commerceis that activity where a capital is put into; work and risk runof profit or loss. If the activities are undertaken for productionor distribution of goods or for rendering material services, thenit comes under the definition of commerce.

D.V. Chug v. State & Anr...........................................81

DELHI PUBLIC ACT, 1978—Section 28/112—Code of CriminalProcedure 1973—Section 482—Petitioner whose prosecutionsis sought to be initiated under Sections 28/112 was workingonly as a manager of Indian Coffee House—Allegation againstpetitioner is that he failed to produce a license for running aneating house and accordingly, a Kalandara under Sections 28and 112 was lodged against him—Held, it transpires thatpetitioner was only a manager and he was neither owner norproprietor of premises in question consequently, proceedingsarising under Section 28 and 112 as well as any otherproceedings arising therefrom against petitioner are quashed.

Janak Raj v. State NCT of Delhi & Ors...................158

DELHI RENT CONTROL ACT, 1950—Section 14(1) (e)—In

with a direction for appointment of Special Educators and forprovision of requisite aids in recognized unaided and aidedprivate schools, Delhi—Plea taken by Action Committee, twospecial educators may not be required in all schools inasmuchas all schools may not even have children with disabilities andrecognized unaided private schools should be permitted tomake appointments of Special Educators and provision forspecial aids on a need based basis—Schools be allowed toshare Special Educators amongst themselves—Per contra pleataken by counsel for GNCTD as well as counsel for petitioner,if such liberty is granted, schools, without incurringexpenditure on salaries of Special Educators would claimreimbursement per child as being paid to schools who employsuch Special Educators—Absence of Special Educators andother Special Provisions for disabled in school would act asa deterrent to children with disability seeking admission theretoand would become a vicious cycle—Special Educators canbe of assistance not only to children with disability but to otherchildren as well and for this reason also it is essential forschools to have them—Held—Recognized unaided privateschools as well as aided schools are required to employminimum of two Special Educators in each school andappointment of such Special Educators cannot be madedependent on admission of children needing SpecialEducators—Each of such school has to have provision forspecial aids for such children and is required to provide abarrier free movement—Absence today of any such childrenin school, cannot be excuse for not providing such facilities—If existing staff/teachers in schools are surplus and/or studentstrength or student-teacher ratio of school so permits, schoolscan have their existing staff trained to teach children withdisability instead of engaging separate Special Educators—Deployment of Special Educators cannot be deferred tilladmission of children with special needs and schools have tobe in a state of readiness and preparedness to receive childrenwith special needs—Capital expenditure on making schoolbuilding and premises barrier free so as to allow freemovement to children with disability, has to be incurred byschools from their own coffers and is not reimbursable byGovernment—All recognized aided and unaided private schoolsin Delhi directed to appoint Special Educators and to make

their buildings/school premises barrier free so as to providefree movement/access to children with disabilities—DoE,Govt. NCT of Delhi directed to ensure compliance ofdirections issued by this Court and to take action for de-recognition against erring schools—Schools where childrenwith special needs are already admitted or will be admittedhereafter, shall immediately make provision for SpecialEducators and further ordain that no school shall refuseadmission to children with disability for reason of notemploying Special Educators or not providing barrier freeaccess in school premises.

Social Jurist, A Civil Rights Group v. Govt. ofNCT of Delhi.................................................................308

HINDU SUCCESSION ACT, 1956—Probate—Testamentarycase of late Smt. Lajwanti Grover seeking probate of willfiled—Three sets of objections filed—One set of objectionwas filed by son of first wife of deceased husband of lateSmt. Lajwanti Grover Second set of objection was filed bylegal heirs of pre—deceased son of deceased husband andthird set of objection was filed by other two sons of deceasedhusband—Third set of objections challenged ownership of lateSmt. Lajwanti Grover, second wife of deceased husband quaproperty in East Patel Nagar, New Delhi alleging that she wasnot owner of property and therefore, she could not bequeaththe same Held:—A Probate Court does not go into the title ofthe properties—It only examines the validity of will i.e.essential execution of the will, attestation of the will and thesound disposing mind of the testator (which will include theaspect of any surrounding circumstances qua the will).

Prof. B.R. Grover v. The State..................................127

INDIAN EVIDENCE ACT, 1872—Section 34—Plaintiff filed suitfor recovery—According to plaintiff, suit amount was onaccount of debit balance due from defendant as per runningaccount—Defendant contested the suit and pleaded that therewas no running account but payment was made bill-wise—Also relationship between parties was terminated all paymentswere cleared—Also suit was barred by limitation—To proverecovery of amount, plaintiff relied upon statement of account.Held: A mere entry in the statement of account is not sufficient

(xxi) (xxii)

to fasten any liability and the entries in the statement ofaccount have to be proved by means of the documents/vouchers of the transaction.

J.K. Synthetics Ltd. v. Dynamic Cement Traders........398

INDIAN PENAL CODE, 1860—Section 288/304A/338/337/427—Petitioners charged for committing offences punishableu/s 288/304A/338/337/427 of the Code—They challenged theorder urging that they were simply members of ManagingCommittee which wanted temple to be constructed forwelfare of general public—Managing Committee had takenservices of three contractors to raise construction andpetitioners had no role in the commission of offence, also nospecific allegations were made against them—Held:—At thestage of charge the learned Trial Court is only required to lookinto the basic material/evidence before it and form an opinionthat prima facie case is made out against the accused persons.

Bhagwan Dass & Ors. v. State....................................114

—Section 162(2)—Circumstantial evidence—Dying declaration—As per case of prosecution, deceased was conductor on truckbelonging to accused Prabhash—On morning of incident,deceased went to house of accused Prabhash to take wagesfor two months—Deceased compelled to drink liquor despiterefusal and thereafter beaten by accused Prabhash and othertwo accused Manoj and Jaibir—Accused Manoj picked uptwo plastic canes containing acid and poured on deceasedwhile deceased held by other two accused—Deceased becameunconscious—When gained consciousness he found himselfnaked in injured condition near his jhuggi—Brother of deceased(PW 1) took him to hospital—Accused Prabhash arrested—Two statements of deceased recorded by police constable(PW-8)—Two other accused subsequently arrested—AccusedManoj got recovered plastic cane—Deceased died after 9 daysof incident—Cause of death was pneumonia and septicemiaconsequent to burn injuries—Trial court convicted accusedPrabhash and Manoj u/s 302/34—Accused Jaibir acquitted—Held, well settled principle that dying declaration was asubstantive piece of evidence to be relied on, provided it wasproved that same was voluntary and truthful and the victim

was in a fit state of mind—Doctor examining (PW6) accuseddid not make endorsement on MLC that deceased fit to makestatement—Certificate on MLC relied upon as DyingDeclaration not scribed or signed by doctor—Author ofendorsement on MLC not produced as witness—Nothing toindicate that history in MLC given by patient—MLC recordedvery casually—Endorsement on MLC (Ex. PW 6/A) not adying declaration—Dying declaration (Ex. PW8/B) recordedby Head Constable PW 8 was in language which cast doubt,whether statement recorded on dictation of deceased—Medication administered to deceased not on record—No nameor indentify of person who endorsed fitness on statement Ex.PW8/B brought on record nor examined—No time ofendorsement mentioned—No evidence of fitness of deceasedwhen Ex. Pw 8/B scribed by PW-8—Second statement Ex.PW8/B not in words of deceased –No certification of fitnessor name of doctor who examined—Statement did not bearsignature or thumb impression of deceased—IO had 9 dayswhile the deceased was in hospital to get his statementrecorded by Magistrate, however made no efforts—Seriousinfirmities in statements recorded—Material contradictions withregard to time of occurrence, identify of assailants and mannerin which deceased attacked between two Dying Declaration—Events projected in Dying Declarations did not find mentionin statement of witness—Manner in which deceased receivedinjuries, doubtful—No proximity of time between statementsattributed to the deceased and his death—Contradiction instatements of recovery witnesses—No explanation about noclothes of the deceased being recovered from the spot—Notproved how deceased was transported from place ofoccurrence to site of his recovery—Controversy with regardto identify of kerosene cane recovered and delay in sendingsame for forensic examination—No arrest memo produced—Medical evidence and surrounding circumstances altogethercannot be ignored and kept out of consideration by placingexclusive reliance upon Dying Declaration—No evidence toshow that accused persons last seen with deceased—Evidencereflects failure of IO to examine eye—witnesses/publicwitnesses—In cases of circumstantial evidence, burden onprosecution is always greater—No evidence with regard tocommonality of intention to cause death—In cases of

(xxiii) (xxiv)

circumstantial evidence, inculpatory facts proved on recordmust be incompatible with the innocence of the accused andincapable of explanation—It is settled law that if there is somematerial on record which is consistent with the innocence ofthe accused which may be reasonably true even through it isnot positively proved to be true, the accused would be entitledto acquittal—Appeal Allowed.

Prabhash Sharma & Anr. v. State...................................1

INDIAN SUCCESSION ACT, 1925—Section 57, 67, 276 readwith 227—Deceased, mother petitioners, died after executinga Will—she was survived by two legal heirs namely herhusband, who died during pendency of Probate petition andher son, i.e., petitioner who is only surviving petitioner—Disposition of her properties by deceased was in favour ofpetitioner and his wife also—Petitioner was also one of attestingwitnesses—Both attesting witnesses of Will have beenproduced—Execution of Will thus, stood duly proved—Thereare no suspicious circumstances surrounding execution of Willin question—One question of law which arose was as towhether Will, having been attested by petitioner, bequest toextent it is in his favour, would be void or not—Held, bequestmade to attesting witnesses of Will, executed by a Hindu, isnot void under Section 67 of said Act—Therefore, bequestmade to petitioner is not void—As regards his competence asan attesting witness, Section 68 specifically provides that noperson, by reason of interest in, or of his being an executorof, a Will shall be disqualified as a witness to prove executionof Will or to prove the validity or invalidity thereof—Therefore,petitioner was a competent witness to prove execution of willexecuted by deceased.

Anand Burman v. State.................................................152

LIMIT ATION ACT, 1963—Section 5—Constitution of India1950—Article 227—Copy of suit for recovery was served on17th August, 2010—Though on 1st November 2010,petitioners appeared, but WS was not filed—Thereafter, matterwas adjourned on few dates and it was only on 4th February,2011 that petitioners filed an application under section 5 ofLimitation act r/w section 148 and 151 of CPC seekingcondonation of delay in filing written statement mainly on

ground that petitioners were involved in construction of varioussites and the documents pertaining to this case were nottraceable and could only be traced after much efforts—It wasalso averred that it took some time to requisition the relevantdocuments and on receipt thereof the same were sent to theircounsel for preparing WS and in the process, the filing of WSgot delayed –Said application was dismissed and review againstsaid order was also dismissed—Held in instant case, plea thatwas taken that documents were misplaced at some site andcould be traced only after many efforts, is apparently vagueand irresponsible—Similar is plea that documents were givento counsel who took some time to prepare WS—In backdropof mandatory provision of law regarding filling of WS, pleastaken for seeking condonation are extremely vague and devoidof any merit.

Omaxe Ltd. & Ors. v. Roma InternationalPvt. Ltd............................................................................76

— Article 59—Specific Relief Act, 1963—Section 31—Plaintifffiled suit seeking partition of suit property situated in VivekVihar, New Delhii—Defendant no. 2, brother of plaintiff anddefendant no. 1 moved application u/o 12 Rule 6 Plaintiffsupported the application whereas defendant no. 1 contestedthe same—As per plaintiff, he, defendant no. 2 and defendantno. 3 (the father) had entered into agreement recording thatproperty was joint property of all the parties—Said agreementwas followed by family settlement stating that all parties had1/4th share in suit property and an affidavit of defendant no.1 of same date to same effect—Defendant no. 1 did not denyexecution of said documents but alleged misrepresentation andlegal ineffectiveness of documents which required trial andcould not be disposed of by applying provisions of Order 12Rule 6. Held—There are two types of documents; one is voidand second is voidable documents. For void documents, anysuit for cancellation u/s 31 of Specific Relief Act is not requiredto be filed—whereas voidable documents have to be cancelledas per Section 31 of the act and a suit could be filed within 3years as per Article 59 of Limitation Act.

Suresh Srivastava v. Subodh Srivastava and Ors.......272

— Article 136—Appellant filed execution petition seeking

(xxv) (xxvi)

execution of decree passed by Court, while making an awardrule of court—Execution petition dismissed being notmaintainable—Aggrieved appellant challenged the order—Respondents raised one of the objections that execution petitionwas barred by limitation and merely because appeal againstdismissal of objections was pending, without there being astay, (which was also dismissed.) limitation for preferringexecution petition did not stop to run on the date on whichaward was made rule of Court. Held:—The period of limitationfor execution begins from the date of decision of the AppellantCourt in a case when the decree of the Lower Court ischallenged in Appeal as the original decree merges in theappellate decree.

Ravinder Prakash Punj v. Punj Sons Pvt. Ltd..& Ors..............................................................................321

MOT OR VEHICLES ACT, 1988—The appellant being ownerof the offending vehicle filed the written statement butthereafter, stopped appearing and was proceeded exparteleading to exparte award against him—Appellant movedapplication under Order IX Rule 13 alleging that he wasinformed by his counsel that appellant need not come to courtand counsel would keep track of the matter and on being againcontacted, the counsel told him that Insurance Companywould do the needful and subsequently, appellant receivednotice of recovery—MACT dismissed the application—Hencethe appeal—Held, after filing the written statement the appellantstopped appearing and the matter was listed on four dates afterwhich the appellant was proceeded exparte, though someproxy counsel appeared but no evidence was led despiteopportunity—Held, conduct of appellant shows that he wasnot vigilant in pursuing the matter, no infirmity in the orderof MACT.

Ramesh Kumar v. Mohd. Rahees & Ors......................72

— Section 168—Award challenged inter alia on the ground thatwhile considering the income of the deceased amount paid bythe deceased employer towards medical, LTA basket,Provident Fund and medi-claim premium, was not taken intoconsideration—Deceased was working with a multi nationalcompany—Held, deceased was getting a flexi basket of Rs.

11,539/- per month, besides salary—In multi nationalcompanies normally choice is given to an employee as to howthe employee wants to take the package to give advantage ofdeduction in income Tax Act—The deceased gave the choiceto get the amount of Rs. 11,539/- as reimbursent towardsconveyance, petrol, mobile phone usage charges etc.—Ifsome facilities are provided are provided by the employer forthe benefit of employee or his family, the same are relevantfor the purpose of computation of income of the deceased—Thus, apart from dearness allowance, other allowances,payable for the benefit of family, are to be considered incomputing the annual income.

Lalita Parashar & Anr. v. Ranjeet SinghNegi & Ors....................................................................119

— Section 163A and 166—Deceased ‘S’ driving TSR met withaccident with a Maruti Car—His legal representatives filed aPetition under Section 163A of Act claiming compensationfrom owner/insurer of Maruti Car as well as TSR—ClaimsTribunal awarded compensation and opined that since bothvehicles were involved in accident, there would be equalliability on insurer of both vehicles—Order challenged byinsurer of TSR—Plea taken, since deceased was himselfdriving TSR, his legal representatives could not have claimedcompensation from themselves and from owner (beingvicariously liable)—Appellant being insurer of TSR had noliability—Claims Tribunal erred in awarding compensationunder Section 166 of Act although petition was preferredunder Section 163A of Act—Held—Where driver of a vehiclewhether a two wheeler, a TSR or any other vehicle meetswith accident involving another vehicle and if accident is causedon account of his own negligence, he would not be entitledto any compensation—If accident did not occur on accountof driver/owner's own negligence, he would be entitled toclaim compensation from owner/insurer of other vehicleirrespective of fact whether there was any default ornegligence on part of driver of other vehicle or not—Nodefence was taken by driver and owner of Maruti Car or it'sinsurer that accident was caused on account of deceased'sown negligence—Claim's Tribunal opinion that there wouldbe equal liability on insurer of both vehicles is not correct

(xxvii) (xxviii)

interpretation of Section 163A of Act—Appellant is not liableat all to pay compensation—Compensation reduced as it is tobe awarded on basis of structured formula.

IFFCO Tokio General Insurance co. Ltd. v.Babita & Ors.................................................................206

RECOVERIES OF DEBTS DUE TO BANKS ANDFINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS ACT, 1993 –Section 2(9),3(2), 19(1) and 25—The Debt Recoveries Tribunal(Procedure) Rules, 1993—Rule 6—Code of Civil Procedure,1908—Section 16, 20 and Order 34—The Security Interest(Enforcement) Rules, 2002—Rule 4, 5, 6 and 8 –The HinduMarriage Act, 1955—Section 21—Petition filed impugningorder of DRT—III, Delhi holding that it has no jurisdictionto entertain appeal preferred by petitioners under Section 17of SARFAESI Act for reason of petitioners being resident ofMeerut, loan in their favour having been sanctioned by branchof respondent bank at Meerut, loan being repayable at Meerutand mortgaged property being at Meerut and even if actionunder Section 13(4) or Section 14 of SARFAESI Act is to betaken by bank, bank will have to approach concerned DistrictMagistrate at Meerut for appointment of receiver, for takingpossession of property—A doubt having arisen as tocorrectness of judgment of DB of this Court in Indira Deviinsofar as holding that appeal under Section 17 of SARFAESIAct can be filed not only in DRT having jurisdiction wheremortgaged property is situated but also in DRT havingjurisdiction where branch of Bank/Financial Institution whichhas distributed loan is situated as well as in all DRTs whichwould have jurisdiction in terms of Section 19(1) of DRTAct read with Rule 6 of DRT Rules, Full bench wasconstituted—Plea taken, DRT Delhi has jurisdiction by virtueof provisions of Section 19(1) (c) of DRT Act read with Rule6(d) of DRT Rules to entertain and decide such appeal—Percontra, counsel for bank supporting impugned order,contended that it is rather in interest of Bank also, ifjurisdiction of DRT Delhi is permitted to be invoked and onsame parity, bank should also have freedom to approach ChiefMetropolitan Magistrate at Delhi for assistance for takingpossession of mortgaged property, even if situated outsideDelhi—jurisdiction of DRT before which appeal under Section

17 (1) of SARFAESI Act can be filed shall be determined asper DRT Act and Rules made thereunder—Referring toSection 19(1) of DRT Act it was contended that jurisdictionthereunder is of DRT where defendants or any of them residesor carries on business or where cause of action wholly or inpart arises—Event which triggers appeal under Section 11 (1),is action of Authorized Officer of Bank—DRT within whosejurisdiction said Authorized Officer is situated, would havejurisdiction—Since in present case, Authorized Officer ofRespondent Bank has issued notice to Petitioners from withinjurisdiction of Delhi, DRT having jurisdiction over Delhi wouldDefinitely have jurisdiction to entertain appeal—Rule 6 has beenamended to provide for jurisdiction not only of DRT Whereapplicant is functioning as a Bank or Financial Institution, butalso of DRTs within whose jurisdiction defendants or any ofthem resides or carry on business or where cause of actionwholly or in part arises—Amendment of Rule 6 is afterSARFAESI Act came into force and legislature should bedeemed to have amended Rule to provide for jurisdiction ofDRT qua appeal under section 17 (1) of SARFAESI Act also—Held—Division Bench fell in error in assuming Debt/moneyrecovery proceeding to be initiated by Bank under DRT Actas equivalent to legal proceeding subject whereof is amortgaged property, within meaning of section 16 of CPC—Proceedings referred to in Section 19(1) of DRT Act aremerely proceeding for recovery of debt and not forenforcement of mortgage—Even prior to coming into forceof DRT, Act, Bank, even if a mortgage, was not mandatorily,required to enforce mortgage and which under Section 16 ofCPC could be done only within territorial jurisdiction of Courtwhere mortgaged property was situated and Bank was freeto institute a suit, only for recovery of money and territorialjurisdiction whereof was governed by Section 20 of CPC,containing same principles as in Section 19(1) of DRT Act—Recovery proceeding under DRT Act are equivalent to a suitfor recovery of money before a Civil Court and cannot besaid to be for enforcement of mortgage—Cause of action ofappeal under Section 17(1) of SARFAESI Act is taking overof possession/management of secured asset and which causeof action can be said to have accrued only within jurisdictionof DRT where secured asset is so situated and possession

(xxix) (xxx)

thereof, is taken over—It is said DRT only which can be saidto be having “Jurisdiction in the matter” within meaning ofSection 17(1) of Act—Exercise of jurisdiction under Section17(1) of SARFAESI Act by DRTs of a place other than wheresecured asset is situated is likely to lead to complexities anddifficulties which are best avoided—There is no provision inDRT Act providing for territorial jurisdiction of appeal underSection 17(1) of SARFAESI Act and question of applicationthereof under Section 17(7) does not arise—Limits ofterritorial jurisdiction described under Section 19(1) of DRTAct cannot be made applicable to Section 17(1) of SARFAESIAct—Section 19(1) of DRT Act is not omnibus provisionqua territorial jurisdiction—It is concerned only with providingfor territorial jurisdiction for applications for recovery of debtsby Bank/Financial Institutions—Same can have no applicationto appeals under Section 17(1) of SARFAESI Act which areto be preferred, not by Banks/Financial Institutions, but againstBanks/Financial Institutions—Use, in section 17(7) ofSARFAESI Act, of words “as far as may be” and “same asotherwise provided in Act” also exclude applicability even ofprinciples contained in Section 19(1) of DRT Act to determineterritorial jurisdiction of appeal under Section 17(7) ofSARFAESI Act—Merely because defendant if were to sue,can sue at place of residence of plaintiff, does not entitleplaintiff to sue at place of his residence if that place wouldotherwise not have territorial jurisdiction—Application underSection 17(1) of SARFAESI Act can be filed only before DRTwithin whose jurisdiction property/secured asset against whichaction is taken in situated and in no other DRT—No errorfound in order of DRT. Delhi holding it to have no jurisdictionto entertain appeal/application under Section 17(1) ofSARFAESI Act, mortgage property against which action istaken being situated at Meerut.

Amish Jain & Anr. v. ICICI Bank Ltd......................377

— Section 19 (1)—The Securitization and Reconstruction ofFinancial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act,2002—Section 13 (2), 14, 17—Transfer of Property Act,1882—Section 65 A—Respondent No. 2 to 6 availed loansfrom ICICI Bank by creating equitable mortgage of propertyin question owned by Respondent no. 6 HUF as well as other

immovable properties and also hypothecation of their movableassets—Since borrowers failed to repay said loan, ICICI Bankapproached DRT by filling two original applications—DRTrestrained Respondent No. 6 from selling or parting withpossession of mortgaged properties—Later, ICICI assignedaforesaid debt and incidental rights together with securityinterest held by it to Respondent no. 1 Bank I.e. KotakMahindra Bank Ltd—Respondent no. 1 Bank initiatedproceeding for recovery by issuing notice under Section 13(2) of SARFAESI Act—HUF filed Securitization Appeal beforeDRT—While said Securitization Appeal was pending HUF andpetitioner, despite restrain order, entered into registered leasedeed—Securitization Appeal dismissed by DRT against whichHUF filed appeal before DRAT—In meanwhile HUF andRespondent No. 1 Bank entered into a compromise and movedapplication before DRT—In terms of joint compromise,consent decree passed by DRT—Alleging default in paymentby borrowers, in terms of aforesaid compromise, Respondentno. 1 Bank moved application under Section 14 of SARFESIAct before DRT for seeking assistance in taking possessionof mortgaged properties—Borrowers filed SecuritizationAppeal against same before DRT—DRT declined to grantinterim relief—subsequently writ petition filed before HighCourt wherein borrowers offered to liquidate their dues bybringing in purchasers—High Court dismissed applicationseeking extension of time to sell property observing thatborrowers have not only cheated and misled Respondent no.1 Bank, but have been even tried to over reach this court bynot disclosing to this court that they had created third partyinterest in respect of various portions of mortgagedproperties—In meanwhile, upon motion by Respondent no. 1Bank, Ld. ACMM (Special Acts) appointed a court receiverto take possession of mortgaged properties which includedproperty in question—A notice in respect of taking physicalpossession of secured assets was served upon borrowers bycourt appointed receiver—Petitioner while in possession ofproperty in question filed securitization appeal impugningaforesaid notice which was dismissed by DRT—Petitionerfiled appeal before DRAT alongwith application seeking interimprotection against taking of possession of property in questionby court receiver—DRAT vide impugned order dismissed

(xxxi) (xxxii)

(xxxiii) (xxxiv)

application—Order challenged before High Court—Plea taken,joint application filed before DRT itself recorded thatRespondent No. 1 bank would be entitled to receive leaserental arising out of property in question—Having soconsented, Respondent NO. 1 Bank cannot now take a pleathat tenancy in question was in violation of restrain order—Tenancy had been entered into much prior to compromiseapplication moved by Respondent no. 1 Bank and borroweraccorded its consent and acceptance—Only right ofRespondent no. 1 Bank is to receive rent towards satisfactionof outstands of borrowers—Aforesaid tenancy had beenexecuted in ordinary course of management vide a registeredlease deed—Amount of Rs. 4.5 crores referred to as securitydeposit in lease deed had actually been advanced to HUF as aloan, vide a separate agreement, which had to be repaid onexpiry of terms of 36 months—Same was not in nature of apremium and as such tenancy was not in violation of section65 A of T.P. Act—This court itself in civil suit filed bypetitioner herein seeking permanent injunction againstborrowers from dispossessing petitioner from property inquestion was pleaded to grant interim protection to petitioner-Per contra plea taken, tenancy relied upon by petitioner, is inutter violation of restrain order of DRT—Same has beenentered into between petitioner and HUF in collusion, with aclear fraudulent intent to avoid/defeat request of RespondentNO. 1 Bank and siphon mortgaged property—Consideringterms and conditions of agreements executed betweenpetitioner and HUF, transaction of Rs. 4.5 Crores thoughnomenclature as a loan, was in true sense, a premium paid inrespect of property in question and thus protection of section65 A is not available to petitioner—In terms of jointcompromise entered into between Respondent no. 1 Bank andborrworrers, symbolic possession of mortgaged propertiesalready vested with Respondent No. 1 Bank and physicalpossession of same could be taken by per its own discretionas and when it deemed so fit—Tenancy of premises expiredon 18.9.12 and possession being taken over by RespondentNo 1 Bank after passing of impugned order, petitioner hereinhas no legs to seek any interim protection in respect ofproperty in question—Held—DRT vide order dated 2.5.2003had in clear terms restrained borrowers from creating and third

party interest in mortgaged properties, including property inquestion—Said order was never modified or set aside in anyproceedings thereafter—However, despite same, tenancy withrespect to property in question came to be entered intobetween petitioner herein and HUF—This clearly demonstratesfraudulent conduct, not only of borrowers, but also ofpetitioner who colluded with borrowers—Said tenancy wasnot only in utter disregard of DRT’s order but was also inthe teeth of provisions of Section 65 A of T.P. Act whichprovides for mortgagor’s power to lease mortgaged property,which is in its lawful possession—A perusal of same, revealsa flow of consideration of Rs. 4.5 Crores under guise andgarb of a loan and security deposit, which was much morethan otherwise agreed rental amount—As per terms of tenancyand loan agreement not only would said amount fetch amonthly interest of 2.92% to petitioner but in event of defaultof payment of same, petitioner would have right to disposeof leased premises through a public auction and recoveramount—Considering conduct and inability of borrowers topay of its principal loans/facilities, and conditions of said leaseand loan agreement, were in effect that of a virtual sale—Saidamount was nothing but a premium paid in respect of saidproperty and as such violative of Section 65 A of Act—Therefore, protection of said provision would not be availableto tenancy in question—Next submission of petitioner thatcompromise entered into between borrowers and respondentbank no. 1 provided for a deemed approval to factum oftenancy in question and as such cannot be overridden bymortgage created in favour of respondent no .1 bank, alsohas no merit whatsoever—Said compromise also gavesymbolic possession of mortgaged properties to respondentno. 1 Bank with discretionary right to take possession as andwhen it deemed fit—Even if one were to accept plea ofpetitioner, that compromise (decreed by DRT) accorded adeemed approval to tenancy in question and in effect over-rid earlier restrain order of DRT, same would have to besubject and conditional to aforesaid possessory rights ofrespondent no. 1 Bank which formed a part of samecompromise—For this reason as well, said submission ofpetitioner also stands rejected—Moreover, Tenancy inquestion also stands extinguished and possession restored to

(xxxv) (xxxvi)

respondent no. 1 Bank—In view of same, nothing survivesin present petition—Grievances, if any, that petitioner mayhave, in view of recovery of possession by respondent no. 1bank before expiry of tenancy in question are matters whichare to be raised in independent appropriate proceedings andcan only be against HUF-Since respondent no. 1 Bank has noprivity of contract with petitioner, petitioner cannot claim anyrelief against respondent no. 1 Bank—Present petitiondismissed with costs.

Harsh Vardhan Land Limited v. Kotak MahindraBank Limited & Ors.....................................................413