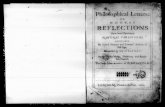

Imagery, Expression, and Metaphor (Philosophical Studies, vol. 174 (2017), pp. 33-46).

Transcript of Imagery, Expression, and Metaphor (Philosophical Studies, vol. 174 (2017), pp. 33-46).

Imagery, Expression, and Metaphor Mitchell Green

University of Connecticut

To appear in Philosophical Studies (early 2016) Abstract: Metaphorical utterances are construed as falling into two broad categories, in one of which are cases amenable to analysis in terms of semantic content, speaker meaning, and satisfaction conditions, and where image-construction is permissible but not mandatory. I call these image-permitting metaphors (IPM’s), and contrast them with image-demanding metaphors (IDM’s) comprising a second category and whose understanding mandates the construction of a mental image. This construction, I suggest, is spontaneous, is not restricted to visual imagery, and its result is typically somatically marked sensu Damasio. IDM’s are characteristically used in service of self-expression, and thereby in the elicitation of empathy. Even so, IDM’s may reasonably provoke banter over the aptness of the imagery they evoke.

Keywords: metaphor, simile, empathy, expression, somatic marker, Relevance Theory, implicature.

1

1. Two flavors of metaphor

A metaphor may be sufficiently familiar that one can bypass any imagery it may convey in

order to grasp what a speaker means in using it.1 ‘Summiting the mountain was a piece of cake,’

‘Getting that contract was a bear,’ and ‘Shaika nailed her calculus exam,’ are likely to be understood

as noting that the climb was easy, that getting the contract was quite difficult, and that Shaika did

very well on her exam, respectively, but without the hearer needing to form images of cake-eating,

marauding bears or nail guns. Assuming these cases do not involve dead metaphors, they are still

sufficiently quotidian to enable most listeners to bypass imagery in interpreting utterances containing

them.2 As such, Relevance theorists’ (e.g., that of Carston 2002) characterization of them as

involving the construction of ad hoc concepts may well be an adequate account of how they function.

A metaphor that an addressee can understood without needing to construct an image I shall call an

image-permitting metaphor, or IPM for brevity.

Other metaphors rely more heavily on imagery. When I was an undergraduate student of

John Searle’s, he related the story of Wittgenstein’s first meeting with Frege. Wittgenstein recalled

that Frege “…wiped the floor with me.” I had never heard this phrase before, and I had briefly to

cast about to understand it. Was Wittgenstein suggesting that Frege used him for housework, that

the two of them did housework together, that Frege used the young Wittgenstein for some other

lowly task, or something else? Eventually I understood that Wittgenstein’s point was that Frege

1 Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Go Figure Workshop, University of London, at the Oslo Workshop on Metaphor and Imagery, and at Lewis and Clark College. I am grateful to all three audiences, and particularly to Nick Allott, Liz Camp, Robyn Carston, Joel Martinez, Jay Odenbaugh, Mihaela Popa, and Dierdre Wilson, for their insights. I am also grateful to two anonymous referees for this journal for their detailed and insightful comments on an earlier draft. 2 Zwaan, et al, 2002, Zwaan, et al, 2004, and Wassenberg and Zwaan 2010, provide experimental evidence suggesting that even idioms such as these activate mental imagery. However, we do not yet know that such imagery is required for utterance interpretation.

2

dominated him intellectually. Now if you tell me that Manchester United wiped the floor with

Chelsea, I readily grasp your point, whereas in first understanding Searle’s story I had to form an

image, presumably cartoon-like, of one person using another to sweep or mop a floor, and then I

had to entertain a conjecture about how this relates to what transpired between Wittgenstein and

Frege.

So it is with many novel metaphors. John F. Kennedy announced the inauguration of the

United States’ space program by saying, “America has tossed its cap over the wall of space.” What

was he trying to get across? Presumably that the U.S. has done something daring toward an entity—

outer space-- that is at the very least mysterious, and where it is not at all clear what the result will

be. We grasp this by considering someone tossing their cap over a wall that one cannot see over or

around, and then by contemplating the audacity of such an act. Many of us will arrive at this

interpretation of JFK’s words by contemplating an image and then reflecting on its significance.3

Those metaphors whose comprehension requires contemplation of an image, be it visual,

tactile, auditory, or involving more than one sensory modality, we may call image-demanding metaphors

(IDM’s). Whether a metaphor is an IDM or merely an IPM will be relative to a hearer and a time,

and this for two reasons. First, once one has heard an IDM, it tends to become an IPM for that

individual. In subsequent encounters with that metaphor, the auditor will generally be able to bypass

construction of an image and distill a semantic content instead. (This for instance is what occurred

in my experience of the ‘A swept the floor with B’ frame.) Second, while one auditor may only be

3 To say that a metaphor requires that the hearer construct an image in order to comprehend the speaker, is not to say that there is a particular image that must be so constructed. Instead, anything within a vaguely specifiable range will do. Accordingly, we can reliably identify cartoon-like images of one person sweeping a floor with another, and of a person throwing their cap over a wall on the other side of which is something vast and mysterious. Further, in what follows we will not need to take sides on the dispute over the nature of mental imagery. Whether such images are sui generis phenomena or instead reducible to, say, sentences in the language of thought, need not be settled here. Instead, we assume only that speakers do in fact form mental images that they on occasion use in utterance interpretation. (See Kind 2001 for further discussion.) Likewise, the present discussion remains neutral on the extent to which mental imagery is embodied. (Gibbs and Berg 2002 contend that much mental imagery is embodied.)

3

equipped to interpret a metaphor by contemplation of an image, another auditor might grasp it by

calling on background knowledge not having to do with a prior encounter with that metaphor. More

specifically, for some listeners, a metaphor might require her to call on more than her lexical

knowledge for its comprehension, and yet not demand that she invoke an image. In a Chronicle of

Higher Education article on the advancement of women in academia, Ward and Eddy (2013) describe

female faculty as traversing a “leaky pipe” on their path of advancement through university

hierarchies. A reader might form an image of women as passing through a pipe with holes big

enough for people to fall through, where one hole might represent bearing a child, another the

aftermath of sexual harassment, a third implicit bias, etc. However, the reader might instead draw on

her background knowledge about leaky pipes, including the fact that things tend to fall through the

openings that enable the leaks. Invoking such background knowledge does not itself require calling

up an image.

Although background knowledge (or belief) will account for our comprehension of many

metaphors, some readers will still process the leaky pipe example imagistically. This was the case

with my first encounter with this metaphor, though I am not prepared to settle the empirical

question how typical my reaction was. Further, for many metaphors, few of us will be able to make

sense of them by drawing on background knowledge. Although I was barely into my third decade

when I heard Searle’s anecdote about Wittgenstein and Frege, I did not have background knowledge

of what happens when one person uses another for housework to enable me to interpret

Wittgenstein’s metaphor. So too for the case of throwing one’s hat over a wall. And similarly for

many other rich and evocative metaphors. Consider these lines from K. Rexroth’s poem, ‘Falling

Leaves and Early Snow’:

In the afternoon thin blades of cloud

4

Move over the mountains;

The storm clouds follow them;

Fine rain falls without wind.

The forest is filled with wet resonant silence.4

‘Thin blades of cloud’ and ‘wet resonant silence’ will for many of us evoke visual and auditory

images respectively. Someone might interpret the latter image by drawing on his background

knowledge, gained perhaps from having been told, that a forest in which it has just rained may be

very quiet. Perhaps he will also interpret ‘resonant’ in this poem as suggesting that any sound that

does occur in said forest will produce an echo. Many of the rest of us, however, will be obliged to

call up imagery in order to comprehend Rexroth’s poem, for instance by aurally imaging the sound

of a very few raindrops echoing off tree trunks. When a metaphor M demands, of an auditor A, that

she call up imagery in order to comprehend it, let us say that M is image-demanding for A. However, in

what follows I will generally suppress reference to auditors, and so will speak simply of image-

demanding metaphors (or IDM’s).5

2. Speaker meaning and self-expression

Davidson (1978) and those following him are wont to deny that verbal metaphors have any

meaning that goes beyond the literal meanings of the words with which they are formulated. As a

4 K. Rexroth, ‘Falling Leaves and Early Snow,’ from The Collected Shorter Poems (New Directions Publishing, 1996). 5 The position I defend in this essay is in broad agreement with that espoused in Carston 2010, but differs in a number of details. For instance, Carston remarks (2010, p. 300) that all metaphors require contemplation of an image, writing, “…in my view, full understanding of any metaphor involves both a propositional/conceptual component and an imagistic component, though the relative weight and strength of each of these varies greatly from case to case.” We do not adopt that view here. So too, Carston suggests (ibid, p. 317) that metaphors that rely heavily on imagery fall outside the domain of pragmatics because they are not driven by reflexive communicative intentions. By contrast, because I take imagistic metaphors to be characteristically in the service of self-expression, which I take in turn to fall within the domain of signaling (see Section 2), I take these kinds of metaphor to fall within pragmatics.

5

result, such writers will take issue with my appeal above to comprehending metaphorical utterances

insofar as doing so takes the interpreter beyond the literal meaning of the words in which they are

couched. In what follows we will find reason to discern an insight in a Davidson-inspired minimalist

position. However, much current research contends that many verbal metaphors are used to convey

a speaker meaning that will typically differ from the meanings of the words used. On one approach

of the latter kind, such as that of Searle 1979, metaphorical utterances conversationally imply

semantic contents; on another, such as that of Carston 2002, such utterances invite interlocutors to

create ad hoc concepts of a sort that will enable the speaker’s utterance to make sense.

Either of these approaches may shed light on the significance of IPM’s. A speaker using an

IPM seems in general to be getting across a content with some illocutionary force. My remark that

your friend Armand is a loose cannon is a way of asserting that he tends to speak in rash,

unpredictable ways; perhaps also that he has upset many of his listeners in the past. Your remark

that developers have raped the countryside is a way of contending that commercial real estate

development has damaged what otherwise might have remained a pristine natural environment. As

evidence that IPM’s are regularly used in service of speech acts, observe that they can be used to lie.

(I know perfectly well that Armand is the picture of diplomatic restraint, and say what I do only to

intimidate you before an important meeting with him). They may also be challenged: knowing better,

to my remark about Armand you might reply, “He’s not a loose cannon at all; in fact he is

diplomatic and gracious in conversation, unlike some other people I know.”

To say that IPM’s are generally used in the service of illocutionary acts, is not to say that

such acts must have propositional contents. A soldier might be told by her superior to blow away

the enemy, and I might ask my daughter how to kill the music blaring on her Ipad. In the former

case we have an illocution with an imperatival content, while in the latter we have one with an

interrogative content. Imperatival and interrogative contents may well be semantic objects that are

6

not reducible to propositional contents, or one to the other (Green, 2014). If that is so, then IPMs

may serve as vehicles of illocutionary acts without expressing propositions.6

A speaker using an IDM might be invoking an image in order to express a semantic content

in the course of performing an illocution. While JFK’s “wall of space” metaphor is in some respects

open-ended, it seems clear that he was making an assertion, very roughly to the effect that the U.S.

has done something daring with respect to outer space. Had it turned out that the entire space

program was a sham that JFK and his staff orchestrated to distract attention from more troubling

matters, JFK would have been a liar in saying what he did. This is evidence that some IDM’s are

capable of being used in the service of content-involving illocutionary acts.

Yet someone using an IDM need not be doing anything illocutionary. Instead, she may be

using the image carried by its figurative language as a vehicle of self-expression. To explain how I

understand this notion and its significance for communication, I will contrast it with two notions of

speaker meaning. As Neale 1992 observes, Grice used the word ‘mean,’ in its non-natural sense, to

refer to acts more or less equivalent to assertion. While he did make room in his account of speaker

meaning for imperatives, he paid only modest attention to different forces with which one might

express a single propositional content. As a result, philosophers of language do not regularly apply

the concept of speaker meaning to the entire range of illocutionary acts. This may be rectified with a

notion of illocutionary speaker meaning, in which one expresses a content (not necessarily propositional)

and overtly manifests one’s commitment to that content. For instance one might express a

propositional content and manifest one’s assertoric commitment to it, or manifest a mode of

commitment appropriate for conjecture, or instead for supposition for the sake of argument.

Alternatively one might express an interrogative content (commonly construed as a set of

6 Just as a speaker might utter a sentence with the intention only of expressing a proposition rather than performing an illocution, it also seems possible for a speaker to utter an IPM with a similar sub-illocutionary purpose.

7

propositions rather than a proposition) with the force of a question, or instead with that of

assertion, such as would be appropriate for, “How many plates we need depends on how many

guests attend the party.” Similarly for other contents and forces with which they may be associated.

Distinct from illocutionary speaker meaning we also have objectual speaker meaning, in which I

overtly make manifest something for the sake of drawing your attention to it as well as to my

intention to get you attend to it. Here, as with illocutionary speaker meaning, my act is overt, but it

does not involve expression of a semantic content. We are hiking through a dense wood, and I see

something in the middle distance that I can’t make out. I silently but overtly gaze at it, with the

intention of getting you to pay attention to it as well. I am not (silently) stating anything, or even

wordlessly warning you of anything. And yet you might ask yourself, what does he mean in overtly

gazing over there? Until you see the creature too…

Contrast illocutionary and objectual speaker meaning with acts that are communicative but

lack the reflexive intentions integral to speaker meaning. Following Green 2007, I construe self-

expression as designedly showing one’s cognitive (belief, memory, wonder, etc.), affective (emotions

and moods), or experiential state (such as perceptual or hallucinatory states). I say ‘designedly’

because self-expression requires more than a manifestation of what is within. A galvanic skin

response might manifest my heightened affective state. That response does not however express that

state. Rather, for a case of self-expression we would need behavior designed to manifest such a

psychological state. Such design may but need not take the form of conscious intention. Instead it

may be the result of cultural evolution or natural selection. Facial configurations associated with

such emotions as anger, fear, surprise and disgust may well be designed by natural selection to show

their possessor’s emotion; if so, then they are also facial expressions. Similar remarks apply to

behaviors that are not intentionally produced but that are acquired as part of one’s cultural heritage:

so long as culture has designed them to manifest one’s psychological state, they are also expressive

8

behaviors. (An example is the high rising terminal intonation pattern of “upspeak”, often used

inadvertently by Gen-X speakers and yet expressive of a sense of tentativeness.) Even when we

perform an act with the intention of manifesting a psychological state, however, that still does not

require the reflexive intentions characteristic of speaker meaning.

In our own species, the more primitive expressive behaviors are facial expressions, vocal

intonation, and bodily posture (scowling, screaming, gearing up for an attack). We also create

artifacts that have expressive qualities. For instance a person might deliberately create an object that

looks as if it has been damaged by the elements: a dwelling dilapidated with age, for instance, might

express the designer’s feeling of decay or exhaustion under the pressures of life. Another artifact

might appear to be reaching for the sky, and we see in it a sense of hope or aspiration. Implicit in the

communicative power of such artifacts is that they are vehicles of expression: they show how the

designer feels, and they may do this without being in the service of illocutionary acts.

In expressing oneself, one designedly shows how one thinks, feels, or what an experience is

like. But expressive activity covers a broader range. I might create an artifact with expressive

qualities that does not express my current feelings. For instance I may be aware of how I felt in the

past and express that feeling, or I might try to give a sense of how someone else might have felt

under certain conditions that I have not experienced (such as watching the death of one’s child or

being a victim of sexual violence.) This is a fraught project best approached with humility. But if I

am at all successful, I will create an artifact that is expressive of an emotion or mood without

necessarily expressing my emotion or mood. For a simple case, if I have the requisite technical skill I

might compose some sad music, and if I succeed the result will be expressive of sadness without

expressing the emotion I feel, which happens to be relief at finally getting a paycheck.

We need not behave according to the pattern of basic emotions or create physical artifacts in

order to express our feelings. Instead we can use words to evoke images that represent such

9

artifacts. I say our love is a house on fire, thereby offering you a sense of how I feel about it.

Further, once we’ve begun to use words to refer to artifacts, we can then take a further step to use

words to evoke images of things that we do not create ourselves. Rexroth does this with his

depiction of wet resonant silence. Similarly, D.H. Lawrence in Lady Chatterley’s Lover describes how

“…little gusts of sunshine blew,” through a wooded area. The first time you hear Lawrence’s

metaphor, you likely need to form a visual image in order to grasp what the narrator might be trying

to convey. But in the cases of Rexroth and Lawrence, although the dramatic speaker is making

assertions, the authors’ primary aims are expressive: both metaphors are expressive of the authors’

sense of what an experience is like. Rexroth’s words give one a sense of the rapture one feels in a

quiet wooded area in which it has just rained; Lawrence provides a sense of the delight we are wont

to experience in dappled forested sunlight.

Once we appreciate the expressive qualities of IDM’s, it also becomes apparent that nothing

crucial is lost by our widening our scope to similes as well. Had Rexroth instead written that the

clouds were like thin blades moving over the mountains, he would not have said much, given the

relative triviality of similarity claims. To appreciate the comparison I need instead to contemplate the

imagery it employs. Similarly for a line from MGMT’s song, ‘Kids’, which reads, ‘Memories fade, like

looking through a fogged mirror.’ The simile shows by means of its imagery what it is like to try to

recall memories, and provides a sense of the author’s difficulty in recovering memories as time

separates him from them.

As I have construed the notion, expressive behavior is not a species of speaker meaning.

This is true regardless of whether one takes speaker meaning to require audience-directed intentions

(Grice 1989) or denies this requirement (as do Davis 2003 and Green 2007). Expressive behavior’s

independence from speaker meaning does not, however, imply that it is to be lumped with natural

meaning. Rather it is a form of signaling designed to convey information about the signaler’s

10

psychological state, where the notion of design at issue here includes but is not restricted to

audience-directed intentional behavior. Construing IDM’s as characteristically in the service of

expressive behavior helps to explain the appeal of Davidson’s animadversions about metaphorical

meaning: the more evocative metaphors not caught in the net of the Relevance Theorists’ analysis

do not seem to be veiled assertions or other illocutionary acts, but are instead used as vehicles of

expression. Further, once we adopt this approach, it also emerges that similes are often used for

expressive purposes, and even that a speaker’s use of an IPM rather than a bit of literal language may

be due to her desire to convey a sense of how she feels, thinks, or what her experience is

like--and thus to speak expressively.

3. Imagery and affect

Images can produce affective responses in those who view, hear, or otherwise experience

them. Whether or not it is a rational response, a picture of someone suffering will upset most non-

sadists, and a picture of some delectable food will make us yearn for a bite of it so long as we are

neither ill nor sated with a recent meal. These pictures need not be taken to represent an actual state

of affairs. Instead, they often do their work in a way that bypasses the higher cortical processes that

help us decide whether the image represents a real situation. Advertisers are forever using images

that largely bypass our skeptical scruples, and even more high-minded activists are not above similar

techniques, be they images of a cigarette shaped like a gun pointed toward the smoker, or a fur coat

covered with blood and entrails.

One source of the power of such images is that they are often somatically marked (Damasio

1995; Adolphs 2003). For an image to be somatically marked is for it to be something to which we

have a visceral and automatic affective reaction intimately bound up with (and not just caused by)

that image itself. An image of a child being physically abused by her parent is “marked” because we

11

tend to view it aversively. Or think of your e-mail inbox when you are expecting a verdict from an

agency to which you’ve applied for a grant. Your perceptual experience of that message with the

subject line ESF, NSF, NIH, AHRC, etc., will be suffused with emotion, probably anxiety,

apprehension, or if you are confident, excitement. Likewise, you can recall events in your life whose

memory is charged in one way or another, and that charge may lingers for years. When I was five my

brother and I decided that not all of our toy Hot Wheels cars were created equal, and each of us got

a hammer and smashed the ones we judged to be inferior. To this day I cannot look at or imagine a

Hot Wheels car without cringing.

It helps to formulate the idea here adverbially. At least phenomenologically, it is not that one

experiences an image and then a consequent affective response. Rather, the affect is bound up with

the image in a way that is well expressed by such locutions as: he looks back on the childhood

indiscretion cringingly; she looks forward to the birthday party excitedly; he anticipates the root

canal with horror. These affective components of the perceptual (or quasi-perceptual, if the image is

a memory or of a prospective event) experience are, inter alia, bodily responses. As such, these

somatically marked experiences are world-directed but at the same time body-involving.7

Words can also call up images, and the images thus conjured may also be somatically

marked. But a single image may well be marked differently for different people. So far as I know,

only my brother and I have the image called up by the phrase ‘Hot Wheels event’ marked with a

feeling of shame. In conversation with him, I could refer to some contemporaneous event in such

terms and he would understand me. However, most everyone else would be puzzled as to my

meaning. Perhaps metaphors always presuppose some common affective ground, but it would be

good to know whether, how, and to what extent a metaphorist can transcend peculiarities of her

7 Space limitations preclude discussion of the neurological aspects of the somatic marker hypothesis. Damasio 1995 and subsequent work by his team of collaborators provide ample discussion of this dimension of the hypothesis.

12

experience for purposes of communication. To make some headway on this question I will briefly

consider some recent work on metaphor by Lepore and Stone in order to show how it contains

some insights that the present approach both incorporates and goes beyond.

4. Cognitivism narrow and wide

It is widely assumed that cognitivism about metaphor must either come as the view that

metaphorical utterances express propositions (or as things that produce propositions when properly

enriched), or as the view that they conversationally implicate such propositions.8 Since just

expressing a proposition is usually of little communicative interest, we may better understand the

propositional view in either of its forms as also holding that the proposition in question is

ensconced in an illocutionary act. Thus modified, either view might pass as a narrow form of

cognitivism about metaphor.

As we have seen, verbal metaphors can conjure up images that often affect us in ways that

don’t require our judging that the image that has been so conjured is an accurate description of some

state of affairs. One might nevertheless present such an image for communicative purposes, and

more precisely in order to convey how one feels or what an experience is like. Cornelius de Heem’s,

‘Still Life with Oysters, Lemons and Grapes,’ displays these items in various stages of decay. In so

doing the work conveys a sense of the ephemeral nature of the pleasures of the flesh. Alternatively, a

speaker might say that the pleasures of the flesh are soon rancid and maggoty. If this latter,

metaphorical utterance provokes us to conjure up a scene, we can with its aid imagine what it is like

to experience such putrefaction, and recoil accordingly. Or someone tells us she is felled by grief,

8 A reviewer of an earlier draft of this essay suggested that talk of a propositional content being conversationally implicated sounds contradictory. The reason given for this seems to be that propositional contents only appear as part of what is said, rather than of what is implicated. This view rests on a confusion. For while it may be that there is more indeterminacy in what is implicated than in what is said, it is still the case that any putative determination of what is implicated will refer to a semantic content, be it propositional, interrogative, imperative, or of a type corresponding to a fourth, more exotic grammatical mood.

13

and we might imagine a scene such as the grieving father depicted in Van Gogh’s, ‘Grief’, or think of

John Lee Hooker’s, ‘Tupelo (Black Water Blues).’

In their 2010, ‘Against Metaphorical Meaning,’ and again in their unpublished ms,

‘Philosophical Investigations into Figurative Speech Metaphor and Irony,’ Lepore and Stone aim to

resuscitate Davidson’s non-cognitivist view of metaphor, according to which

(a) metaphors do not imbue words with a special nonce-sense, and

(b) it is not the case that the metaphorist is producing a speaker-meaning that diverges from

the literal meaning of the words she utters.

The view being denied in (a) would not postulate a divergence between what is literally said

and what is conveyed, but would tell us that the words uttered took on a new, temporary, sense for

the occasion of the metaphorist’s utterance. The view being denied in (b) would be naturally

captured by the view that the metaphorist only makes as if to say such a thing as that Juliet is the sun;

instead, her speaker meaning is produced by pragmatic principles together with a plausible

hypothesis as to what she is instead aiming to convey—perhaps that Juliet is radiant and that the

world revolves around her. On either view, one can recover a content that is speaker-meant, and to

which the speaker has committed herself in a way characteristic of such speech acts as assertions,

questions, and commands.

Lepore and Stone will adopt neither such view, but rather will hold that in metaphor, an act

of speech but no speech act is performed. That is, words are uttered, but the metaphorist is not making

an assertion, suggestion, command or performing any other speech act either direct or indirect. Is

the metaphorist, then, just banging on a brazen pot, in the manner of Cratylus? No, because the

words she uses do tend to call up images that activate associations in the mind of the hearer, and

14

those images/associations can produce results in the hearer that are in the general ballpark of what

the speaker is aiming to achieve.

A characteristic way in which this occurs is by representing A as B. I could represent John as a

baby by reporting his words in an infantile way of speaking. Indeed, such representations need not

be verbal: I might imitate John’s walk or run and stylize that performance in such a way as to

accentuate his baby-like characteristics. But in neither case am I committing myself to something’s

being so, just as I would not typically be committing myself to John’s being a baby by drawing a

picture of him as a baby. (No doubt context could make clear that such a picture is an expression of

my views: “Please draw a picture of John that best represents your considered opinion of his level of

emotional maturity,” but I’m not supposing that now.) So too, “word-painting” John as a baby (for

instance with the words, “John’s a baby”) need not commit me to the truth of the proposition that

he is an infant, and hence is not an assertion (or other speech act such as conjecture or supposition

for the sake of argument).

Lepore and Stone illustrate their view with a quotation from the Colbert Report, writing:

…Colbert’s banter with documentary filmmaker Morgan Spurlock hints at the

subversiveness of imagery that allows people to understand one another better.

Stephen Colbert and Morgan Spurlock, on empathy

S: We kind of live in a world where we don’t really know what other people’s lives are like,

and by doing this [Spurlock’s TV show, 30 Days] you kind of immerse yourself in an

environment where you learn a little bit along the way.

15

C: But don’t we live our own lives so we don’t have to know what other people’s lives are

like? I mean, that’s why I’ve got power windows, so I can roll up the window when I go

through the neighborhoods I don’t live in.

S: I think we need one in between the seats too, so you can’t see the person next to you.

C: That’d be fantastic. Maybe our own oxygen system.

Lepore and Stone characterize their conclusion from this and another case as follows:

In [our examples], interlocutors use the language of debate, but in fact what they are doing is

developing imagery and cementing a shared understanding of their situation, actions and

values. They do not contest propositions. In much the same way, we expect, interlocutors

use their metaphorical discourse not to assert and deny propositions but to develop imagery

and to pursue a shared understanding. Such practices can account for our interactions in

using metaphor, without appealing to metaphorical meaning or metaphorical truth. Indeed,

they are all the stronger for dispensing with such notions. (2010, p. 177)

This notion of developing imagery and pursuing a shared understanding is suggestive, and we are

now in a better position to elaborate what it comes to than are these authors while agreeing with

them that we do not need to reach for propositions, speaker meaning or truth conditions in order to

do so. The reason is we now see IDM’s as characteristically in the business of self-expression. When

I say I’d like my own window and oxygen system in my car, I am speaking metaphorically and

facetiously, but am giving voice to my desire (which is not strong enough to act on) to avoid other

people when I travel. Or I describe a particularly productive colleague as a whirling dervish of

activity, and at the very least am conveying my sense of her as moving very fast. “Conveying a sense

16

of soandso” is a form of self-expression. But to understand me, you may need to form that dervish

image as well. This is how Lepore and Stone’s “shared understanding” can occur in the absence of a

speaker-meant content, and notice as well that it can be used for both good and nefarious purposes.

(Consider the imagery carried by some racial slurs.)

In a more recent paper, Lepore and Stone (ms) try to get at a similar point with their

example of a pilot of a small plane answering a co-pilot’s question why the landing gear is raised

immediately after take-off. The pilot answers the question by overtly putting the landing gear down

in mid-flight, since by doing so she shows how this increases drag on and thereby slows the plane.

The pilot thus shows rather than tells what happens, but still answers the co-pilot’s question. So too,

aver Lepore and Stone, a metaphor shows one how to think about a situation: Matt Groening’s

metaphor (“Love is a snowmobile racing across the tundra and then suddenly it slips over, pinning

you underneath. At night, the ice weasels come.”) shows one how to think about romantic love.

Now we may agree that (as argued in Green 2007, and Green forthcoming) showing how is

a neglected category for theorists of communication. However, a construal of metaphor as showing

how to think about a situation is too narrow. Showing is a success term, and as a result, one cannot

show what is not so. Accordingly I cannot show someone how to count to the largest integer or

show her how to make something that is water but not H2O. Likewise if romantic love is in no

interesting way like a snowmobile ride, then I cannot show you how to think or feel about it with

the aid of Groening’s metaphor. Similarly, if I am phobic about heights, my metaphorical utterances

(“The maw of the abyss gaped below me as I gazed down from atop the stepladder”) will

presumably not show how to think (or feel) about being a few feet above the ground. At most they

will show how I (and my fellow phobics) feel about such situations. But because such utterance are

also designed to show how I feel, they fall squarely within the ambit of self-expression. So too, on

what we might call a wide cognitivism about metaphor, IDM’s characteristically express affective or

17

experiential states without being vehicles of illocutionary speaker meaning. Wide cognitivism’s

breadth, however, also enables it to accommodate speaker-meant uses, which are the natural habitat

of IPM’s.

5. Metaphor and empathy

I might become aware of how a metaphorist thinks about a phenomenon, but be unable or

unwilling to agree that this is how I should think about it. The speaker is a pedophile and uses

metaphors to express the nature of his sexual arousal toward children. I don’t agree that this is how

to feel about children. However, his psychotherapist might by listening to his metaphors have some

hope of appreciating his impulses at one remove, at least in order to come to appreciate the strength

of the attraction that afflicts him. Or again, my arachnophobic friend uses metaphors to express the

nature and extent of her fear of spiders. These metaphors do not show how to feel about spiders,

but they do help me put myself in my friend’s shoes.

Following Green 2008, I construe empathy as imagining oneself into another’s emotional or

experiential situation. Empathizing is thus to be distinguished from sympathizing, on the one hand,

and emotional contagion on the other. Sympathizing requires feeling concern for another but can be

done with no identification with that individual’s situation. Emotional contagion requires “catching”

another’s emotion. But in empathy I don’t have to feel what the other is feeling; I just have to make

as if I am doing so. In so doing I need not sympathize with the other, either. If I think the state

you’re in with which I’m empathizing is entirely your fault and your comeuppance as well, I

probably am not inclined to sympathize with you.

In expressing my emotions and moods I enable others to empathize with me if they are

willing to do the work that is necessary. I can sometimes help them by giving them a sense of what

my emotional state is a reaction to, or rather something that this state corresponds to, in the sense of

18

Eliot’s “objective correlative.”9 And as we have seen, we can in turn do that pretty well by using

words to convey images. Jane Hamilton’s A Map of the World begins with a person’s description of

how it felt to watch her life unravel before her after someone else’s child drowned on her watch. We

read of the unreturned phone calls, the shutters closed as she approaches a former friend’s house,

and of the very brief conversations that do occur. These experiences all contribute to the narrator’s

feeling of being ostracized, and if you read this narrative you will be in a position to know how that

feels even if you’ve never felt ostracized yourself. After reading the narrative you know how it would

feel to experience these various slights, and on this basis you can imagine feeling what the narrator

does. The narrator might have spoken in more general terms but still quite effectively had she said

she felt left out in the cold, or like she was put on an ice floe, or banished to hell for what she had

done.

6. Metaphorical banter

We can reasonably disagree with one another’s metaphorical utterances. You say that the

dead guy was a ton of bricks falling out of the car, and I demur. I might even do so metaphorically,

saying no, he oozed out. Recall Matt Groening’s metaphor about love:

Love is a snowmobile racing across the tundra and then suddenly it flips over, pinning you

underneath. At night, the ice weasels come.

9 “The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an “objective correlative”; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked.” From Eliot, ‘Hamlet and his Problems,’ in Eliot 1921.

19

To this I might reply, no, it’s a ride in a Goth amusement park at the end of which you get dropped

into a vat of boiling oil. These kinds of dispute are not without substance, but at the same time they

differ from disputes over precisely what caused the bridge to collapse or how many guests attended

the gallery opening.

How can we make sense of such rationality as this metaphorical banter may have? My

suggestion is that we can do this by noting metaphor’s expressive role, while keeping in view the fact

that the emotions thus expressed are capable of being more or less apt as responses to worldly

situations. The snowmobile metaphor suggests a sense of bracing exhilaration that ends with a

feeling of being stuck and then a slow, excruciating demise. The Goth amusement park metaphor

also suggests exhilaration though more likely mixed with fear, but then predicts a culmination in

absolute agony. Two speakers can meaningfully dispute which of these two affective responses is a

more apt reaction to falling in love and its likely aftermath. If both have experienced breakups that

are dramatic and agonizing rather than slow and excruciating, they will likely find the Goth image a

better expression of their feelings. In some cases, however, a dispute like this will have no proper

resolution.

Summing up, then, I’ve attempted to cultivate a middle ground between cognitivist and non-

cognitivist approaches to metaphor in which some (the IPM’s) are within the ambit of narrow

cognitivism, at least as that view is formulated in terms of the relevance-theoretic or implicature

approaches; while others (the IDM’s) are not amenable to that treatment but instead are primarily

bound up with expressive behavior, where that behavior trades largely though by no means

exclusively in images. Such expression-supporting imagery puts addressees in a position to

empathize with the speaker, and thereby also to assess the speaker’s affective state for its aptness to

the situation to which it is a response. As such, recognizing imagery as being in the service of self-

expression helps make sense of, and indeed shows some rational basis for, metaphorical banter.

20

Neither of these explanations comes naturally for non-cognitivists, but I have argued that we can

provide these accounts without falling back on the view that one speaking metaphorically is

performing an illocutionary act.

REFERENCES Adolphs, R. (2003) ‘Cognitive Neuroscience of Human Social Behavior,’ Nature Reviews: Neuroscience

4: 165-79. Camp, L. (2013) ‘Metaphor and Varieties of Meaning,’ in Lepore and Ludwig (eds.) Blackwell

Companion to Davidson (Wiley-Blackwell): 361-78. ---(2006) ‘Metaphor in the Mind: The Cognition of Metaphor,’ Philosophy Compass 1: 154-70. Carston, R. (2010) ‘Metaphor: Ad Hoc Concepts, Literal Meaning and Mental Images,’ Proceedings of

the Aristotelian Society CX: 295-21. ---(2002) Thoughts and Utterances (Blackwell). Cohen, T. (1978) ‘Metaphor and Cultivation of Intimacy,’ Critical Inquiry 5: 3-12. Damasio, A. (1995) Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain (Penguin). Davidson, D. (1978) ‘What Metaphors Mean,’ in S. Sacks (ed.) On Metaphor (Chicago). Davis, W. (2003) Meaning, Expression and Thought (Cambridge). Eliot, T.S. (1930) The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Cricisism (Knopf) Gibbs, R., and E. Berg (2002) ‘Mental Imagery and Embodied Activity,’ Journal of Mental Imagery 26:

1030. Green, M. (forthcoming) ‘Expressing, Showing, and Representing,’ to appear in C. Abell and J.

Smith (eds.) Emotional Expression: Philosophical, Psychological, and Legal Perspectives (Cambridge). ---(2014) ‘Speech Acts,’ The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ---(2010) ‘Perceiving Emotions,’ Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society Supp. Volume 84: 45-61. ---(2008) ‘Empathy, Expression and What Artworks Have to Teach,’ in G. Hagberg (ed.) Art and

Ethical Criticism (Blackwell, 2008): 95-122. ---(2007) Self-Expression (Oxford). Grice, P. (1989) Studies in the Way of Words (Harvard). Kind, A. (2001) ‘Putting the Image Back in Imagination,’ Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 62:

85-109.

21

Lepore, E., and M. Stone (2015) Imagination and Convention: Distinguishing Grammar and Inference in Language (Oxford).

---(2010) ‘Against Metaphorical Meaning,’ Topoi 29: 165-80. ---(ms) ‘Philosophical Investigations into Figurative Speech, Metaphor and Irony.’ Locke, J. (1979) Essay Concerning Human Understanding, ed. P. Nidditch (Oxford: Clarendon). Neale, S. (1992) ‘Paul Grice and the Philosophy of Language,’ Linguistics and Philosophy 15: 509-59. Reimer, M, and L. Camp (2008) ‘Metaphor,’ in Lepore and Smith (eds.) Oxford Handbook of the

Philosophy of Language (Oxford): 845-63. Searle, J. (1979) ‘Metaphor,’ in Ortony (ed.) Metaphor and Thought (Cambridge). Sperber, D., and D. Wilson (2008) ‘A Deflationary Account of Metaphors,’ in R. Gibbs (ed.) The

Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor and Thought (Cambridge), pp. 84-108. Ward, K. and P. Eddy (2013) ‘Women and Academic Leadership: Leaning Out,’ Chronicle of Higher

Education; accessed at chronicle.com/article/WomenAcademic-Leadership-/143503/. Wassenberg, S., and R. Zwaan, (2010) ‘Readers Routinely Represent Implied Object Rotation: the

Role of Visual Experience,’ Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 63: 1665-70. Zwaan, R, C. Madden, R. Yaxley, and M. Aveyard (2004) ‘Moving Words: Dynamic Representations

in Language Comprehension,’ Cognitive Science 28: 611-19. ---, R. Stanfield, and R. Yaxley (2002) ‘Language Comprehenders Mentally Represent the Shapes of

Objects,’ Psychological Science 13: 168-71.