IJALEL, Vol.1 No.5 (2012) [Special Issue]

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of IJALEL, Vol.1 No.5 (2012) [Special Issue]

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature ISSN 2200-3592 (Print)

ISSN 2200-3452 (Online)

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

All papers on which this is printed in this book meet the minimum requirements of "National Library of Australia and EBSCOhost". All papers published in this book are accessible online. Editors-in-Chief: Prof. Dr. Dan J. Tannacito, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA Prof. Dr. Jayakaran Mukundan, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Dr. Tan Bee Tin, The University of Auckland, New Zealand Managing Editor: Seyed Ali Rezvani Kalajahi Website: www.ijalel.org E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978 -600-5361-84-1 ISSN 2200-3592 (Print) ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Graphic Designer: Ali Asghar Yousefi Azerfam Publisher Information (Online) EBSCO Publishing Australia Office Level 1, 51 Stephenson Street Richmond, VIC 3121 Australia Phone: +61 (0)3 9276 1777 Publisher Information (Print) Digital Print Australia 135 Gilles Street, Adelaide South Australia 5000 Australia Phone: +61 (0)8 8232 3404 Website: www.digitalprintaustralia.com Hoormazd Press Inc. also provides hardcopies of IJALEL.

© 2012 – IJALEL No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photo print, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher.

Editors-in-Chief Professor Dr. Dan J. Tannacito, Composition & TESOL Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA

Professor Dr. Jayakaran Mukundan, ELT University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Dr. Tan Bee Tin, Applied Language Studies and Linguistics The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Managing Editor Seyed Ali Rezvani Kalajahi Senior Associate Editors

Professor Dr. Hossein Farhadi, Assessment University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA

Associate Professor Dr. Jesús García Laborda, Linguistics Universidad de Alcala, Madrid, Spain

Professor Dr. Ali Miremadi, Language, Linguistics California State University, USA

Professor Dr. Eugenio Cianflone, TEFL University of Messina, Italy

Professor Dr. Kazem Lotfipour-Saedi Ottawa University, Canada

Associate Professor Dr. Ali S. M. Al-Issa, Applied Linguistics Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

Professor Dr. Mohammad Ziahosseini, Linguistics Allameh Tabataba’i University, Tehran, Iran

Associate Professor Dr. Mojgan Rashtchi, Applied Linguistics IAU North Tehran Branch, Iran

Professor Dr. Farzad Sharifian, Applied Linguistics Monash University, Australia

Associate Professor Dr. Reza Pishghadam, TEFL Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran

Associate Professor Dr. Parviz Maftoon, TEFL IAU, Science & Research Branch, Tehran, Iran

Associate Professor Dr. Wan Roselezam Wan Yahya, Literature University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Professor Dr. Juliane House, Applied Linguistics University of Hamburg, Germany

Associate Professor Dr. Alireza Jalilifar , Applied Linguistics Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran

Associate Professor Dr. Biljana Cubrovic, Linguistics University of Belgrade, Serbia

Assistant Professor Dr. leyli Jamali IAU Tabriz, Iran

Associate Professor Dr. Fatemeh Azizmohammadi, Literature IAU Arak, Iran

Associate Professor Dr. Christina Alm-Arvius, Linguistics Stockholm University, Sweden

Associate Professor Dr. Moussa Ahmadfian, Literature Arak University, Arak, Iran

Associate Professor Dr. Zia Tajeddin, Applied Linguistics Allameh Tabataba'i University,Tehran, Iran

Associate Professor Dr. Ahmad M. Al-Hassan, Applied Linguistics Petra University, Amman, Jordan

Professor Dr. Biook Behnam, ELT IAU Tabriz, Iran

Professor Dr. Meixia Li, Linguistics Beijing International Studies University, China

Professor Dr. Kourosh Lachini, Applied Linguistics University of Qatar, Qatar

Professor Dr. Ruzy Suliza Hashim, Literature Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia

Professor Dr. Cem Alptekin, Applied Linguistics Bogaziçi University, Turkey

Professor. Dr. Sebnem Toplu, Literature and Linguistics EGE University, Turkey

Associate Professor Dr. A. Majid Hayati, Linguistics Shahid Chamran University, Iran

Professor Dr. Ruth Roux, Applied Linguistics El Colegio de Tamaulipas & Universidad Autonoma de Tamaulipas, Mexico

Associate Professor Dr. Huai-zhou Mao, Applied Linguistics Xin Jiang Normal University, China

Associate Editors Associate Professor Dr. Minoo Alemi, Applied Linguistics Sharif University of Technology, Iran

Dr. Servet Celik , Literacy, Culture, and Language Education Karadeniz Technical University, Turkey

Dr. John Dolan, Literature Najran University, Saudi Arabia

Assistant Professor Dr. Mohd Nazim, ELT Najran University, Saudi Arabia

Assistant Professor Dr. Marisa Luisa Carrió Pastor, Linguistics Universitat Politècnica de València, Spain

Assistant Professor Dr. Ahmed Gumaa Siddiek, ELT Shaqra University. KSA

Assistant Professor Dr. Ramesh K. Mishra, Linguistics University of Allahabad, India

Assistant Professor Dr. Javad Gholami, TESOL Urmia University, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Saeed Yazdani, Literature IAU Bushehr, Iran

Dr. Vahid Nimehchisalem, TESL University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Assistant Professor Dr. Reza Kafipour, ELT Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Nasrin Hadidi Tamjid, Applied Linguistics IAU, Tabriz, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Sasan Baleghizadeh, TEFL Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Nooreen Noordin, TESL University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Assistant Professor Dr. Touran Ahour, TEFL IAU Tabriz, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Hossein Pirnajmuddin, Literature University of Isfahan, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Javanshir Shibliyev, Linguistics Eastern Mediterranean University, Cyprus

Assistant Professor Dr. Roselan Baki, TESL University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Assistant Professor Dr. Masoud Zoghi, TESL IAU Ahar, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Md. Motiur Rahman, Applied Linguistics Qassim University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Assistant Professor Dr. Natasha Pourdana, TEFL IAU Karaj, Iran

Dr. Usaporn Sucaromana, TEFL Srinakharinwirot University, Thailand

IJALEL Editorial Team

Assistant Professor Dr. Arshya Keyvanfar, TEFL IAU North Tehran Branch, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Nader Assadi Aidinlou, Applied Linguistics IAU Ahar, Iran

Dr. Tanja Angelovska, Applied Linguistics Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich, Germany

Dr. Catherine Buon, Applied Linguistics American University of Armenia, Armenia

Dr. Ferit Kılıçkaya, ELT Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey

Assistant Professor Dr. Karim Sadeghi, TEFL Urmia University, Iran

Dr. Christopher Conlan, Applied Linguistics Curtin University, Australia

Assistant Professor Dr. Franklin Thambi Jose, Applied Linguistics Eritrea Institute of Technology, Eritrea

Assistant Professor Dr. Ibrahim Abdel- Latif Shalabi, Literature Isra University Amman, Jordan

Assistant Professor Dr. Yousef Tahaineh, Applied Linguistics Al-Balqa Applied University, Amman -Jordan

Distinguished Advisors Professor Dr. Brian Tomlinson, Material Development Leeds Metropolitan University, UK

Professor Dr. Alan Maley, Creative Writing Leeds Metropolitan University, UK

Professor Dr. Dan Douglas, Applied Linguistics Iowa State University, USA

Professor Dr. Jalal Sokhanvar , English Literature Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

Professor Dr. Hossein Nassaji, Applied Linguistics University of Victoria, Canada

Professor Dr. Roger Nunn, Communication, The Petroleum Institute, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Advisors Dr. Ian Bruce, Discourse Analysis and Genre Studies The university of Waikato, New Zealand

Dr. Mohammad Reza Mehdizadeh IUST, Iran

Dr. Steve Neufeld, ELT Middle East Technical University, Cyprus

Dr. Hassan Fartousi, English Studies University of Malaya, Malaysia

Dr. Shadi Khojasteh rad, Applied Linguistics University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Dr. Majid Hamdani, Educational Technology University Technology of Malaysia, Malaysia

Dr. Atieh Rafati, ELT & literature Eastern Mediterranean University, Cyprus

Dr. Kristina Smith, ELT Pearson Education , Turkey

Dr. Saeed Kalajahi, Literature IAU Tabriz, Iran

Dr. Oytun Sözüdoğru, ELT University of York, UK

Dr. Mohamdreza Jafary, TESL University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Reviewers Associate Professor Dr. Esmaeel Abdollahzadeh, TEFL University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran

Dr. Helena I. R. Agustien, Applied Linguistics Semarang State University, Indonesia

Assistant Professor Dr. Omid Akbari, TESL Imam Reza International University, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Ali H. Al-Bulushi, Applied Linguistics Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

Assistant Professor Dr. Hassan Soleimani, Applied Linguistics Payame Noor University, Tehran, Iran

Assistant Professor Dr. Azadeh Nemati, ELT IAU, Jahrom, Iran

Dr. Ruzbeh Babaee, English Literature University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Dr. Yasemin Aksoyalp, ELT Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland

Dr. Shannon Kelly Hillman, Applied Linguistics University of Hawaii, Hawaii

Dr. Marilyn Lewis, Language Teaching DALSL, The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Dr. İsmail Zeki Dikici, ELT Muğla University, Turkey

Dr. Ebrahim Samani, TESL University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Dr. Mahdi Alizadeh Ziaei, Literature The university of Edinburgh, UK

Dr. Melchor Tatlonghari, TESOL The University of Santo Tomas , Manila, The Philippines

Dr. Siamak Mazloomi, ELT IAU Islamshahr, Tehran, Iran

Dr. Bakhtiar Naghdipour, ELT Eastern Mediterranean University, Cyprus

Dr. Sepideh Mirzaei Fard, ELT National University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Dr. Bora DEMİR, ELT Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Turkey

Dr. Hossein Saadabadi, TESL University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

Dr. Kenan DİKİLİTAŞ, ELT Gediz University, Turkey

Dr. Haleh Zargarzadeh, Literature Urmia University, Iran

Dr. Mohammad Javad Riasati, TESL IAU Shiraz, Iran

Dr. Orkun Janbay, ELT Izmir University, Turkey

Dr. Yassamin Pouriran, TESL IAU Tabriz, Iran

Dr. Taher Bahrani, Applied Linguistics IAU Mahshahr, Iran

Dr. Tin T. Dang, Applied Linguistics Vietnam National University, Vietnam

Dr. Sardar M. Anwaruddin, TESOL University of Toronto, Canada

Dr. Erdem AKBAS, ELT University of York, UK

Dr. Inayatullah Kakepoto, ELT Quaid-e-University of EST(Sindh), Pakistan

Dr. Saeed Rezaei, TEFL Allameh Tabataba’i University Tehran, Iran

Dr. Gandhimathi Subramaniam, Language & Literature Anna University Coimbatore, India

Dr. Jerome C. Bush, English Education Yeditepe University, Turkey

Dr. Efstathios (Stathis) Selimis , Linguistics Center for the Greek Language, Thessaloniki, Greece

Dr. Diego Pascual y Cabo, Linguistics University of Florida, USA

Dr. Chili Jason LI, Applied Linguistics University of Liverpool, UK

Dr. Karim Hajhashemi, Applied Linguistics James Cook University, Australia

Dr. Emilia Di Martino, ELT Università Suor Orsola Benincasa, Napoli, Italia

Editorial Assistants Dr. Ali Asghar Yousefi Azarfam, TESL, IAU Tabriz, Iran

Dr. Reza Vaseghi, TESL, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Founding Editor

Seyed Ali Rezvani Kalajahi

Table of Contents Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Images of Iranians in Western Movies: The Case of Iranium

Mohammad Reza Amirian Ali Rahimi Gholamreza Sami 1

The New Development of the Study of Discourse Anaphora ------Review of Discourse Anaphora: A Cognitive-

Functional Approach

Meixia Li 14

Revitalization of Emergentism in SLA: A Panacea!

Nima Shakouri Masouleh 19

Insights From Verbal Protocols: A Case Study

Margaret Kumar 25

On Laotsu’s “Ming and Yan” and the Language in English

Xin Xiong 35

The Picture of Modern Workplace Environment and Oral Communication Skills of Engineering Students of

Pakistan

Inayatullah Kakepoto Hadina Habil Noor Abidah Mohd Omar Yusuf Boon S M Zafar Iqbal 42

Language Countertrading In Courtroom Exchanges in Nigeria: A Discursive Study

Tunde Opeibi 49

Early Lexicon of the Yoruba Child

Bolanle Elizabeth Arokoyo 64

From Polarity to Plurality in Translation Scholarship

Abdolla Karimzadeh Ebrahim Samani 76

Native Breath: Incorporating Linguistically Relevant Pedagogy in the Classroom through Reified Literature

Desiree de Chachula 84

The Evolution of Pakistani English (PakE) as a Legitimate Variety of English

Humaira Irfan Khan 90

Perceptual Convergence as an Index of the Intelligibility and Acceptability of Three Nigerian English Accents

Fatimayin Foluke 100

Null Arguments in the Yoruba Child’s Early Speech

Bolanle Elizabeth Arokoyo

116

Comparison of Gratitude across Context Variations: A Generic Analysis of Dissertation Acknowledgements

Written by Taiwanese Authors in EFL and ESL Contexts

Wenhsien Yang 130

A Sociolinguistic Study of Fagunwa/Soyinka’s The Forest of a Thousand Daemons

Idowu Odebode 147

Theory Construction in Second Language Acquisition In Favor of the Rationalism

Mehdi Shokouhi 157

A Study of Directive Speech Acts Used by Iranian Nursery School Children: The Impact of Context on Children’s

Linguistic Choices

Shohreh Shahpouri Arani 163

Perspectives on Oral Communication Skills for Engineers in Engineering Profession of Pakistan

Inayatullah Kakepoto Noor Abidah Mohd Omar Yusuf Boon S M Zafar Iqbal 176

Using Bilingual Parallel Corpora in Translation Memory Systems

Hossein Keshtkar Tayebeh Mosavi Miangah 184

Language As A Tool For National Integration: The Case Of English Language In Nigeria

Hanna Onyi Yusuf 194

Globalization And English Language Education In Nigeria

Hanna Onyi Yusuf 202

Second Language Acquisition at the Phonetic-Phonological Interface: A proposal

Ashima Aggarwal 208

Engaging with Old Testament Stories: A Multimodal Social Semiotic Approach to Children Bible Illustrations

Abuya Eromosele John Akinkurolere Susan Olajoke 219

Evaluation of English Language Teaching Departments of Turkish and Iranian Universities in Terms of Politeness

Strategies with Reference to Request

Maryam Rafieyan 226

Some Major Steps to Translation and Translator

Mohammad Reza Hojat Shamam 242

The Role of Meaning in Translation of Different Subjects

Mohammad Reza Hojat Shamami 247

Book Review: Litosseliti, L. (2010). Research Methods In Linguistics. Continuum International Publishing Group

Ltd. 228pp. ISBN 978-0-8264-8993-7 (paperback)

Mohammad Javad Riasati Forough Rahimi 251

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 1 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Images of Iranians in Western Movies: The Case of Iranium

Mohammad Reza Amirian, M.A. in TEFL (Corresponding author) Department of English Faculty of Literature & Foreign Languages

University of Kashan, Iran Postal Code: 81997-67951, Isfahan, Iran

Tel: 0098-311-2278352 E-mail: [email protected]

Ali Rahimi, Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics Department of English Faculty of Literature & Foreign Languages

University of Kashan, Iran Postal Code: 87317-51167, Kashan, Iran

Tel: 0098-361-5552930 E-mail: [email protected]

Gholamreza Sami, Ph.D. (Sussex) Professor of Comparative Literature

Department of English Faculty of Literature & Foreign Languages University of Kashan, Iran

Postal Code: 87317-51167, Kashan, Iran Tel: 0098-21-22615284 E-mail: [email protected]

Received: 20-05- 2012 Accepted: 21-06- 2012 Published: 03-09- 2012 doi:10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.5p.1 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.5p.1 Abstract The significant role of the media, in general, and the movies, in particular, in disseminating information and creating images of the real life by use of the language as a powerful social tool is totally irrefutable. Although critical analysis of the movie discourse is a fashionable trend among the critical discourse analysts, there is a paucity of research on movie discourse in Iran. Besides, the increasing number of the anti-Iranian movies produced in the last decade and the growing tendency among the English students to watch American movies, have established the need for conducting a research to investigate the images of Iranians represented in the Western movies. Thus, in this article an anti-Iranian movie called Iranium, allegedly labeled as documentary, has been critically analyzed using Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). For this purpose, Van Dijk’s framework (2004) has been utilized to uncover the ideological manipulations and misrepresentations of this movie. The analysis revealed that the dichotomy of in-group favoritism vs. out-group derogation is a very effective discursive strategy at the disposal of the movie makers who have used language as a weapon to attack Iran by representing a distorted and unrealistic image of the Iranians’ history, culture and ideologies. The findings of the present study imply that adopting a critical discourse analysis perspective in the EFL classes is a necessity which needs the development of the required materials, by the curriculum developers, that raise the students’ critical awareness as well as their language skills and proficiency. Keywords: Critical Discourse Analysis, Discursive Structures, Derogation, Euphemization, Hegemony, Ideology, Manipulation, Power

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 2 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

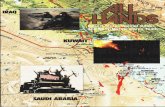

1. Introduction 1.1 Statement of the Problem Media today has become an integral part of life in modern societies. Development of new technologies, computer and entertainment industries including the film industry has encouraged “a titanic struggle among some of the largest corporations in the world for control of a consolidated information industry” (Hamelink, 1997). Hollywood which is often used as a metonymy for American cinema is the birthplace of some of the biggest film production who have been in charge of the production of the most famous blockbusters of all times. This symbol of movie industry has had a profound impact on the modern societies since the early 20th century. As a matter of fact, “not only does Hollywood have a negative impact on society, but it is also becoming an obsession with people living normal lives all around the world” (Miller, 2007). This obsession has become even epidemic in some Western societies. People, especially the adolescents, follow the celebrities lead on TV shows and movies and try to look like them both physically and morally. The ideal body image presented by the motion pictures is skinniness and it is no longer appropriate to have curves or extra weight. More important, Hollywood films and music videos promote sex which damages the moral values and leads the very young astray. The above-mentioned negative effects are only a handful of what is really happening in the real world due to the dominance of the cinema and the movie productions among the adolescents. The situation is different for Iranians. First, there is a great tendency, nowadays, among English students as well as their teachers to increase their exposure to the foreign language by watching movies, sitcoms, TV series, talk shows and documentaries. Students try to watch as many movies as possible in order to boost their listening ability and, at the same time, enjoy the contents of the films, most of which are not suitable for their age. Second, the media representation of Iranians in the West is totally distorted and stereotypic. After the Iranian revolution of 1979 followed by the break-down of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the end of the Cold War, Muslims including Iranians suddenly emerged as the arch-enemy of the West, especially the Americans. As a matter of fact, American leaders felt the need to have a new enemy in order to justify their hegemony over the world. They portrayed Iranians to the Western people, who at that time could hardly find Iran or any other Middle Eastern country on the map, as terrorists and barbaric, cruel savages with no civilization. This situation was aggravated after the declaration of ‘war on terror’ by George W. Bush administration after the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center complex in New York City. America started a war against Afghanistan and Iraq, two neighboring countries of Iran and the so-called ‘axis of evil’, to allegedly shut down al-Qaeda and other terrorist organizations. These military attacks were accompanied by a full media support and a full-fledged attack on Islamic countries especially the Islamic Republic of Iran. Therefore, it seems necessary for the Iranian language learners to develop a critical approach toward movies and exercise caution in selecting them. They need to learn how to increase their grasp of reality and face the distortions and fabrications and this would not be possible, unless they are introduced to the techniques and procedures of manipulation and misrepresentation. As a result, this study can guide both English teachers and students in their selection of the movies and shed some light on the hidden discursive structures and ideologies embedded in their discourse. 1.2 Significance of the Study The findings of the present study in the area of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), including the disclosure of the ideological implications of the discourse of certain movies, can be presented to the field of applied linguistics including pedagogy, and specifically curriculum and materials development to develop materials that raise the students’ critical awareness as well as their self actualization and creativity. First, in the realm of pedagogy and curriculum development, teachers need to reconsider their techniques and procedures of selecting and using the mass media, especially movies, to equip their students with the basic skills of critical thinking. Second, the educational system needs to be completely reformed in the “preponderance of language usage and the somewhat invisibility of language use” (Rahimi & Sahragard, 2006, p.4). In other words, the semantic, pragmatic and functional aspects of language are rarely taught to the students and the result is “a multitude of students with good theoretical knowledge about language but a few of them apparently have a good comprehension of semantics and the hidden messages in the language” (ibid.). 1.2 Objectives of the Study Considering the paucity of research on movie discourse in Iran and the increasing amount of the anti-Iranian movies in the last decade, this article aims at investigating the images of Iranians represented in a Western movie.

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 3 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

The researchers seek to uncover the discursive structures embedded in the discourse of this movie and reveal the ideological manipulations and power relations invisible to the naked eyes. CDA techniques, proposed by Van Dijk’s (2004) framework, have been utilized to scrutinize the language of the movie which represents a distorted and stereotypic image of Iranians to the world. Within this framework, the study focuses on investigating how us and them as social groups are represented in the euphemization and derogation procedures in the discourse of the Western movies. The primary objective is therefore to familiarize the audience with the techniques and procedures used by the producers of such movies to manipulate and misrepresent the truth; so that the listener/reader would be competent enough to detect the biased and exploitative language and develop a critical approach toward the movies. 1.3 Research Questions According to the above-mentioned objectives, the focus of this study can be summarized in the following research questions:

1. What CDA techniques, discursive structures and strategies have been utilized by the producers of this movie to construct and disseminate the idea of Iranophobia?

2. What are the discursive manifestations of the ideologies and how are they achieved in the selected movie?

1.4 Approaches to Media Discourse Many studies have been inspired due to the unquestionable power of the media throughout the world, most of which are critical in different disciplines: linguistics, semiotics, pragmatics, and discourse studies. Their approaches have been mostly content analytical which have revealed stereotypical, discriminatory, racist or sexist images in texts, photos and illustrations. The preliminary studies of media language focused mostly on easily observable surface structures, such as the prejudiced use of words in the description of ‘us’ and ‘them’ (and our/their actions and characteristics), especially in representing the communists along the sociopolitical lines. A series of studies on “Bad News” by the Media Group of Glasgow University, established the critical tone on the characteristics of TV reporting, such as the coverage of various issues (e.g. industrial strikes.) It was the systematic analysis of these events that helped the critical assessment of the subtle bias of the official media in favor of managers, nationalists or racists, for instance by comparing the people who were interviewed, their locations, the methods of interviewing and its camera angles. Cultural Studies paradigm was the framework that was used by a number of media studies (e.g. Hall, et al., 1980). A combination of European neo-Marxist work and British socio-cultural approaches and film analysis (Fairclough, 1995) was the basis for these studies. Within a broad cultural approach to the media text analysis was combined with analyses of images. There is a broad perspective of culture as the dialectic between social consciousness and social being within which critical analysis of media discourse is dealt with as a practice, interwoven with other practices such as social practices, and the experiences of people in their social conditions. Social practices are then examined, among many other dimensions, to analyze the ways they propagate both culture and ideology. In the U.S. a different story emerged; Discourse structures were not the centre of attention for critical media studies. Herman and Chomsky (1988), in their ‘propaganda model’ attacked the U.S. media for their scheming with official U.S. foreign policy, and from time to time refer to the use of biased and persuasive words (such as euphemisms for the brutality of the U.S. troops), but what they do not propose is a comprehensive analysis of media discourse. Furthermore, linguistics, semiotics or discourse analysis has not inspired many critical studies of the media and analysis focuses mostly on the impressionistic readings of the news. “Although in recent years there has been a growing influence of the British Cultural Studies paradigm, this has so far led to few detailed and empirical studies of media discourse” (Van Dijk, 2003:8). Some critical studies have focused on the representation of ‘race’ and ‘gender’ in the media (e.g. Dines & Humez, 1995; Van Zoonen, 1994 in Van Dijk, 1997). There has also been a growing critical literature on popular culture and the media, for example about soap operas (Liebes & Katz, 1990). The study of media discourse was influenced by semiotics which had already found its way into media studies, and thus affected the study of media images, both in the U.S. and in the U.K., by bringing about some basic structuralist notions. However, instead of being critical in nature much of its work is descriptive. (e.g. Hodge & Kress, 1979; Kress & Van Leeuwen, 1996). However, right now there is an ever growing integration of these semiotic studies and work in Critical Discourse Analysis. Van Leeuwen (1998, 2005) has done many studies that bridge the gap between semiotics and CDA. According to (Van Dijk, 2003) “media studies, together with

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 4 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

feminist studies, for many years have provided the richest ground for critical studies of discourse, but few of these studies have been based on a systematic theory of the structures of media genres” (p.9). However, in the past few years media studies and other social sciences as well as linguistics, semiotics and discourse analysis are being intertwined, and “a more detailed and explicit attention for the subtleties of ‘texts’ themselves has been the result” (Van Dijk, 2003:10). Besides, the majority of the studies on the nature of the media in Iran are focused entirely on newspapers, news talks and political debates and there is not much of a research on the case of the movies using CDA framework. Hence this article examines one of the productions of the movie industry which is related to the Iranian people, their history, culture, religion and modern life. 2. Methodology In this article the social function of language as a powerful social practice in a specific discourse, such as media discourse, generally, and the movie discourse, particularly, has been examined. There is a great tendency, nowadays, to represent a distorted and stereotypical image of Muslims, particularly Iranians as terrorists and barbarians who want to destroy and raze to the ground the democracy and freedom of the Western world, especially, those of the American society. Therefore, by analyzing the movie, the researchers try to show how media work and how politicians and policy makers of the Western society influence the world of the media and vice versa. As a matter of fact, there is a mutual relationship between the politicians and the politics of media and how they affect each other. In order to investigate the representation of the images of Iranians in the Western movies, Van Dijk’s framework as a major critical discourse analyst has been utilized. 2.1 Design The researchers chose this movie because it was amenable to the intended CDA framework and epitomized various religious, nationalistic and political viewpoints. The language used in the movie was both politically and religiously charged and it was full of derogation and euphemization strategies or negative other-representation as well as positive self-representation. In other words, it was replete with ideologically manipulative and evaluative vocabulary. The script of the movie was analyzed within the framework proposed by (Van Dijk, 2004). The dichotomous categorization of euphemization and derogation in his framework which reflects the basic strategy of ‘negative other-representation’ and ‘positive self-representation’ (in-group vs. out-group, us / them) has been adopted for the analysis of the data. 2.2 Analytical Framework The framework utilized in this article is that of Van Dijk’s (2004) who elaborates on 27 ideological strategies, the most prominent of which is the dichotomy of ‘euphemization’ and ‘derogation’. This classification is very helpful in implementing the strategy of ‘positive self-representation’ and ‘negative other-representation’. The first one which is an ideological function is used to depict oneself superior than others; while the latter is used to represent others as inferior. Positive self-representation or in-group favoritism is a semantic macro-strategy used for the purpose of ‘face keeping’ or ‘impression management’ (Van Dijk, 2004). Negative other representation is another macro-strategy which is used to categorize people into ‘in-groups and out-groups’. According to Van Dijk (2004) “the division between good and bad out-groups, is not value-free, but imbued with ideologically based applications of norms and values. These are discursive ways to enhance or mitigate our/their bad things, and hence to mark discourse ideologically. Euphemization which is a rhetorical device helps to create positive self-representation and prevents any kind of negative impression formation against the dominant powers. This ideological function as a semantic move is in fact in concordance with another discursive structure called self-glorification mentioned in Van Dijk’s framework. On the contrary, derogation as a discursive device is totally in line with another semantic device suggested by Van Dijk called ‘victimization of others’. As the name suggests others’ deficiencies or even ordinary characteristics are enlarged and brought to the surface. It should also be noted that the macro-strategy of positive self-representation and negative other-representation is made possible through other discursive strategies such as actor description, authority, burden, categorization, comparison, consensus, counterfactuals, disclaimers, derogation, euphemization, evidentiality, falsification, instantiation/example, generalization, hyperbole, implication, irony, lexicalization, metaphor, self-glorification, norm expression, number game, polarization, populism, presupposition, vagueness, and victimization. (For a fuller description of the terms see Van Dijk, 2004.)

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 5 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

3. Data Analysis: Iranium Iranium is a so-called documentary that takes aim at the Iranian Revolution, its ideology and the people behind it. This new Clarion Fund film is the last production of a series of anti-Muslim, anti-Iranian movies produced by Israeli filmmakers. In 2006, Clarion released Obsession: Radical Islam’s War Against the West. In 2008, Clarion released another so-called documentary, The Third Jihad: Radical Islam’s Vision for America. And its newest film, Iranium, premiered February 8, 2011. This documentary or as Ordibehesht (2011) calls it “a malicious and contemptible absurdity paraded as documentary”, bolstered by slick graphics and archival footage, lays out cases for attacking Iran and an official U.S. policy of regime change. From the interviewees to the movie's producers and writer/director, Alex Traiman, “all of the participants espouse hard-line, hawkish views on Iran” (Clifton & Gharib, 2011). Apart from judging the validity and the credibility of the statements made in the film, Iranium leaves out a lot of important history that would help Western viewers understand U.S. relations with Iran. There is nothing about the CIA coup of the 1950s, America’s support for the long-time oppressor of Iran, Mohammad Reza Shah, or “Western support for Iraq’s use of weapons of mass destruction against Iran during the Iran-Iraq War” (Mundy, 2011). What is noticeable throughout the movie is the continuous alarming tone of the interviewees and their partisan outlook, accompanied with countless stock video clips of missile launches, bomb explosions and the wounded and “a soundtrack of suspenseful music that might be used to score a thriller” (Clifton & Gharib, 2011). A central interviewee -- one who passes along a list of largely unsubstantiated links between Iran and al-Qaeda (the alliance of two adversaries with totally different ideologies) as facts -- is Clare Lopez, who is also named to Clarion's advisory board. 3.1 Plot Summary This ostensible documentary opens with a history lesson that begins in 1978 with the first signs of the widespread unrest that would eventually topple the Shah. Iran’s despotic dictator is presented as “a long-time ally of the United States,” as the film’s narrator, Iranian actress Shohreh Aghdashloo, explains. Then comes the Islamic Revolution, and the film “places the blame squarely on the fecklessness of President Jimmy Carter” (Clifton & Gharib, 2011). “The fact that Jimmy Carter did not support the Shah in his time of difficulties actually signaled to the Iranian people that the Shah’s rule was over,” says Harold Rhode, a former Pentagon analyst “involved in Douglas Feith and his Office of Special Plans’ activities building a public case for war with Iraq” (ibid.). Rhode’s comment hints at themes that keep reemerging throughout the documentary: The belief that in order to overcome the Middle Eastern people one should exert power and strength and that, “while Carter and Obama have been weak on Iran, Reagan’s supposed strength was respected in the region” say Clifton and Gharib (2011). After a long buildup describing Iran’s desire to spread the Islamic Revolution abroad (such as through its alliance with Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez), and its so-called brutality to annihilate its opponents and terrorize its enemies, the film describes the Iranian nuclear program. Iran’s public avowals of the program’s peaceful aims are dismissed, and the next section -- titled "Pushing the Button" -- explains how the world will not be able to deter Iran from using a weapon. “Americans and Europeans are really uncomfortable with the idea of holy war and mass murder for religious reasons,” Cliff May says in the film. “Because they can’t imagine that for themselves, they also can’t imagine that others behave that way. But this is a failure of imagination.” It ends with the narrator saying: “Now is the time for action. Americans, Iranians and members of the free world now have a choice; to stand idly by or stand up and take part in Iran’s new revolution.”According to Clifton and Gharib (2011) “Iranium fits nicely into Clarion’s oeuvre” and like the producers’ previous movies, it portrays a clash of civilizations, and propagates the warmongering ideology of American neo-conservatives. It terrifies the viewers of the Muslims’ endorsement of martyrdom, and portrays their so-called irrational hatred toward Israel as key to understanding the anger and frustration voiced by Muslim countries against the United States and states that the only way to stop the Muslims, especially Iranians, is to wage a war against them. The extract selected for the analysis is the third chapter of the film, 30 Years of Terror, where the interviewees make some unsubstantiated claims about Iran’s support for terrorism and try to persuade the viewers that all the terrorist attacks around the world are traced back to Iran. 3.1.1 Thirty Years of Terror Narrator: For over 30 years, the regime has used International terror in its struggle to spread Khomeini’s revolution. Kenneth Timmerman: When you look at the Iranian government terrorist, what you understand is that from the very beginning of this regime in January of 1979, they considered terrorism as a tool of policy. Eliot Engel: We know that Iran is the leading sponsor of terrorism around the world.

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 6 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Walid Phares: The Iranian regime has an endless number of proxy organizations, beginning with the big ones such as Hezbollah. Kenneth Timmerman: Iran set up Hezbollah early in time to have a cut out. Somebody who could independently carry out terrorist attacks with no fingerprints back to Tehran. Narrator: Founded in the early 80s in Lebanon under the guidance of Ayatollah Khomeini, Hezbollah wasted little time before striking American installations. [Showing pictures of the American Embassy bombing captioned as:] Beirut, Lebanon April 1983 ABS News Reporter: The day after this attack on the embassy here in Beirut, the death toll has continued to climb. It is believed that before the counting is over more than 60 people will be found to have died, at least 16 of them Americans. Narrator: Hezbollah’s next attack would prove even more deadly. Attacking multi-national peace keeping forces stationed in Beirut following Lebanese civil war. [The movie shows a procession of hurrying fire engines and ambulances with their wailing sirens captioned as:] Beirut, Lebanon October 1983 Arnold Resincoff: The dead point this had been the largest non-nuclear explosion ever recorded. We were for four days trying to find people who were buried and then we continued to work just to find pieces of bodies to put them together. Every piece of body we wanted to bury and not just leave the bodies under the rubble. Kenneth Timmerman: Their intention in attacking us in Beirut was to drive the United States out of Lebanon and ultimately out of the Middle East. ABC News reporter: Despite repeated proclamations that terrorists won’t affect U.S. foreign policy Muslim forces in Lebanon achieved their goal when Reagan withdraws all 1400 marines to the safety of offshore ships. Kenneth Timmerman: When we put our troops out, we essentially sent the message that Iranians you win! We will respond to terrorism by retreating. It was a terrible message to send and we’ve been paying the price for that ever since. You’ve got a whole series of hostage takings in the 1980s. Clare Lopez: You had attacks in the early 1990s, 1992 Buenos Aires against the Israeli embassy, 1994 against the Jewish cultural center in Buenos Aires. 1996 against Khobar Towers, 1998 Iran was involved with Al-Qaeda and Hezbollah in the East Africa Embassy bombings of Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. In the year 2000 Iran was involved with Hezbollah and Al-Qaeda again against the USS Cole. You’ve got the attacks against Riyadh and so forth. We know from the 9/11 commission report that Iran provided substantial material support to the hijackers who would launch the 9/11 attacks in the United States. Dore Gold: There is clearly a direct connection between the Iranian petroleum and gas industry and its support for global terrorism. Walid Phares: They sent that money to Hamas in Gaza and they sent that money to Nasrollah in Lebanon. Hezbollah in Lebanon used to receive 300 million dollars a year. After 2006 according to open sources they have been receiving close to one billion dollars a year. Kenneth Timmerman: They work with just about every Islamist terrorist group in the world. [Showing continuous images of explosions] Narrator: More recently, Iran has supported militant actions against U.S. troops fighting in the region. Frances Townsend: Iran has not been really very subtle about confronting us in Iraq. Gen. David Petraeus: It is increasingly apparent to both Coalition and Iraqi leaders that Iran through the use of Quds Force seeks to turn the Iraqi special groups into a Hezbollah like force to serve its interests and fight a proxy war against the Iraqi state and Coalition Forces in Iraq. Fox News Reporter: Highly sophisticated weapons known as Explosively Formed Penetrators or EFPs can be directly tied to Tehran. Lt.Gen. Thomas Mcinerney: They are responsible for at least the death of 500 Americans and now they are

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 7 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

moving them over to Afghanistan. CNN Reporter: Iran has gone beyond giving weapons to the Taliban. The Iranians are helping train the Taliban fighters in the use of small arms and they are doing some of that training inside Iran. Senator Jon Kyl: When they provide training and equipment to people fighting us in Iraq and Afghanistan; you would have to say that they are at war with us. Dore Gold: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, was the one who sparked the current wave of global Islamic terrorism through the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Hasan Nasrollah: We yell the rallying cry we learned from Imam Khomeini Louder... Higher... Stronger... Death to America! [People chanting the same slogan, repeatedly.] 3.2 CDA of the Movie This film advertised as documentary, is based on the incomprehensible and in large part baseless and unproven assertions of the interviewees. A true documentary aims at informing and enlightenment, while this movie aims at obfuscation and misleading. “It seems that those who attempt such propaganda films must be truly aiming at the demented”, who don’t have any access to the world of information, “or those who through the indolence of their minds readily accept falsehoods for truth” (Ordibehesht, 2011). Hearing an Iranian actress, Shohreh Aghdashloo, conscientiously reading out loud 60 minutes of accusations and fabrications against her homeland, written and supported by a group of hardliners, including some other Iranians and Arabs, who are urging the public that Iran must be bombed points to the fact that “the U.S. empire now banks on a pedigree of comprador intellectuals, homeless minds and guns for hire” (Dabashi, 2006). In the beginning of this chapter, the narrator generalizes her claim that “for over 30 years, the regime has used International terror”, which is an instance of derogation. Timmerman says, “when you look at the Iranian government terrorist, what you understand is that from the very beginning of this regime in January of 1979, they considered terrorism as a tool of policy” which is an instance of presupposition, derogation, victimization, and polarization. He presupposes that the ‘Iranian government terrorist’ is so widespread that the viewer knows about it and disparages the Iranian foreign policy by accusing the ‘regime’ of utilizing ‘terrorism’ as a tool. He also generalizes his point from the ‘very beginning’ of the revolution to this date. Eliot Engel who is supposedly a democratic congressman states that, “we know that Iran is the leading sponsor of terrorism around the world.” He doesn’t state how he has obtained such information and this is just of a sample of the bulk of unverified assertions of the interviewees. Walid Phares, an Arab author says, “the Iranian regime has an endless number of proxy organizations, beginning with the big ones such as Hezbollah” which is an instance of hyperbole. Using the word ‘endless’ aggrandizes the situation and warns the viewer of the following threats. Another ideological ploy used in the statement is presupposition, in which the speaker presupposes that the viewer already knows that Hezbollah is connected to Iran. Timmerman describes Hezbollah as a ‘cut out’ who “could independently carry out terrorist attacks with no fingerprints back to Tehran.” Here the speaker intends to manipulate the viewer by using the strategies of implication and vagueness. It implies that both Hezbollah and Iran are responsible for all the terrorist attacks and it is not also clear what attacks can really be traced back to Tehran. The narrator then accuses Hezbollah of two ‘deadly’ terrorist attacks during the Lebanese Civil War: “Hezbollah wasted little time before striking American installations”; “Hezbollah’s next attack would prove even more deadly. Attacking multi-national peace keeping forces stationed in Beirut.” What is apparently evident in the above-mentioned statements is the unverified assertions made about Hezbollah, which is an instance of falsification. To the present day, the accusations against Hezbollah about its alleged attacks to the U.S. Embassy and Barracks in Beirut have not been proved. The other point is that, an attack on the military soldiers during a war is never called a terrorist attack, especially the invading forces that have occupied one’s land. The term ‘peace keeping forces’ used to describe American invading forces stationed in Beirut is an instance of euphemization and positive self-representation or in-group favoritism and calling Hezbollah and Iranians as terrorists is an instance of negative other-representation or out-group derogation. The other interviewee says, “the dead point this had been the largest non-nuclear explosion ever recorded” which is another instance of hyperbole and falsification. One of the largest non-nuclear explosions in the history of mankind ever to occur was in 1917 up in Halifax, Nova Scotia. “The Mont-Blanc was a big ship carrying a lot of extremely dangerous cargo -- almost 3,000 tons of munitions bound for the war that was then tearing Europe apart. Approximately 2,000 people died from the explosion and another 9,000 were injured” (Christian, 2008). The Lebanese explosions are not comparable in any degree to the largest non-nuclear explosions recorded in the history. [For a

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 8 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

full list of the explosions see Christian (2008)]. In the following statements, ABC News reporter states that, “despite repeated proclamations that terrorists won’t affect U.S. foreign policy Muslim forces in Lebanon achieved their goal when Reagan withdraws all 1400 marines to the safety of offshore ships.” Here, the speaker implicitly compares Muslim forces to terrorists, which is an instance of implication and comparison. Timmerman continues: “You’ve got a whole series of hostage takings in the 1980s” which is again an instance of vagueness and generalization. Clare Lopez completes the string of unfounded and unsubstantiated allegations and says: You had attacks in the early 1990s, 1992 Buenos Aires against the Israeli embassy, 1994 against the Jewish cultural center in Buenos Aires. 1996 against Khobar Towers, 1998 Iran was involved with Al-Qaeda and Hezbollah in the East Africa Embassy bombings of Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. In the year 2000 Iran was involved with Hezbollah and Al-Qaeda again against the USS Cole. You’ve got the attacks against Riyadh and so forth. We know from the 9/11 commission report that Iran provided substantial material support to the hijackers who would launch the 9/11 attacks in the United States. To respond to all these false and groundless accusations and reveal the absurdity of the arguments is totally beyond the scope of this article but for more information and an in-depth analysis and response to the arraignments and incriminating remarks made in the film see Porter (2008a, 2008b, 2009). What is really facetious about the remarks is that the speaker blatantly connects Iran to Taliban and subsequently to the 9/11 attacks. The 9/11 Commission report states that: “Iran has implemented several widely publicized efforts to shut down al-Qaeda cells operating within its country” (“9-11 Commission Report,” 2004) and there is not any indication of Iran’s support for the hijackers. Besides, Iranians have never accepted Taliban as a legitimate Islamist group and have always supported the anti-Taliban movement in Afghanistan, e.g., Ahmad Shah Massoud who led resistance against the Taliban regime between 1996 and 2001. After the Taliban took power in 1996, Iran's supreme leader denounced the group as an ‘affront’ to Islam (“Policy of Iran's Supreme Leader,” 2012), and “the killing of eleven Iranian diplomats and truck drivers in 1998 almost triggered a military conflict” (Bruno & Beehner, 2009). The last but not least, is that in all the above-stated claims Clare Lopez has utilized the semantic strategy of evidentiality. The speaker has supposedly provided some evidence to persuade the viewer that Iranians are monstrous creatures responsible for all the terrorist attacks occurred during the last decades. The interviewees continue their opprobrious verbiage and Dore Gold says: “There is clearly a direct connection between the Iranian petroleum and gas industry and its support for global terrorism.” Here the speaker disguises his claim as a proven fact and does not provide anything to support his argument which is an instance of vagueness. Another interviewee, based on the Gold’s claim, states, “they sent that money to Hamas in Gaza and they sent that money to Nasrollah in Lebanon. Hezbollah in Lebanon used to receive 300 million dollars a year. After 2006 according to open sources they have been receiving close to one billion dollars a year.” These sentences can be regarded as exemplars of falsification and number game. The speaker has used such big numbers to indicate objectivity that Iran is spending a lot of money on terrorism and increase the credibility of his statement. In the same vein, Timmerman gives it his best shot and says: “they work with just about every Islamist terrorist group in the world” which is an instance of generalization, victimization and derogation. ‘Terrorist’ is used in conjunction with the word Islam to strengthen the producers’ objective which appears to be to naturalize the ideology of the link between Islam and terrorism. This is no doubt a very direct instance of negative other-representation. After presenting a sketchy and distorted historical account, the interviewees talk about the present confrontations of U.S. with Iran in Iraq and Afghanistan. The film shows Gen. David Petraeus, the commander of Multi-National Forces in Iraq, briefing reporters on the issue of Iran’s involvement in attacks against the invading forces in Iraq. He says: “It is increasingly apparent to both Coalition and Iraqi leaders that Iran through the use of Quds Force seeks to turn the Iraqi special groups into a Hezbollah like force to serve its interests and fight a proxy war against the Iraqi state and Coalition Forces in Iraq.” Showing the General’s speech in the film is an instance of the semantic strategy of authority, which the producers have used to legitimize their allegations and accusations against Iran. The General’s speech itself is again an instance of falsification and victimization. He does not provide any proof to support his claims and by the use of intensifiers ‘it is increasingly apparent’ tries to prove his assertion, a direct instance of lexicalization. Then the film shows Fox News report about EFPs or (Explosively Formed Penetrators) which is claimed that these weapons “can be directly tied to Tehran”, again an absurd and groundless allegation and one more instance of evidentiality and falsification. EFPs were first developed during the World War II and they are regarded as improvised explosive devices which can be easily built everywhere with a simple knowledge of weaponry (“Explosively formed penetrators,” 2012).

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 9 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Another instance of authority, falsification, generalization and number game is Lt.Gen. Thomas Mcinerney’s claim that Iranians are “responsible for at least the death of 500 Americans and now they are moving them over to Afghanistan.” Quoting a General who is supposedly an expert in the field and knows about the casualties of the war, with the provided numbers, will not let the viewer doubt the credibility and validity of the statements. Using the word ‘at least’ to imply the high rate of the casualties is an instance of lexicalization. And finally their last orchestrated effort in this chapter to denigrate and disparage the image of Iranians is to relate all the atrocities and abominations of Talibans to Iranians. CNN Reporter says: “Iran has gone beyond giving weapons to the Taliban. The Iranians are helping train the Taliban fighters in the use of small arms and they are doing some of that training inside Iran.” As discussed earlier in the text, connecting Taliban to Iran is an outrageous verbiage and utterly nonsensical; and can be regarded as another instance of victimization and falsification. As some of the American experts have repeatedly stated “the weapons could have been smuggled into Afghanistan via various third-party channels” or “arms factories in Pakistan's North West Frontier Province” that make copies of the Iranian weapons could have sent the weapons to Talibans (Slavin, 2005). Dore Gold, the Israeli hard-liner, finishes this chapter by identifying the Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini as the “one who sparked the current wave of global Islamic terrorism” throughout the world; which is an instance of actor description, derogation, generalization and victimization. Again the derogatory words ‘spark’ and ‘terrorism’ are all instruments of negative other representation. The CDA of this film has provided some ideologically significant points regarding “the effectiveness of language in distorting realities, vilifying certain people and mentalities” (Rahimi & Sahragard, 2007:102). The surprising number of derogatory and pejorative terms used is expressive of the producer’s indignation and disgust with Muslims, especially Iranians. A disproportionately high number of derogatory words, in a short extract of the movie, have been employed to humiliate, criticize and stigmatize the Iranians. The repercussions of mounting a smear campaign of fear-mongering and disinformation against a nation and its people are dreadful and it poses “a mortal threat to the lives and the well-being of millions of innocent Iranians who seem to have now become the targets of yet another war of aggression that appears to be in the making” (Ordibehesht, 2011). Table I CDA of Movie

Selected Terms Discursive Strategy Pressumed Effect/Connotation

Euph. Derog.

distaste ä AVERSION & DISLIKE

defiant ä REBELLIOUS & REFRACTORY

regime ä TOTALITARIANISM

(leading) sponsor of terror

ä PROMOTER OF TERRORISM

violator ä DISOBEDIENCE & CONTRAVENTION

extreme doctrine ä FANATIC & HARDLINER

hostage ä WAR PRISONERS

International terror

ä PANIC & FOREBODING

struggle

ä AGGRESSIVE & BELLIGERENT FIGHTING

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 10 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Iranian government terrorist

ä SAVAGERY & FEROCITY

Fingerprint

ä OUTRAGEOUS & SCANDALOUS BEHAVIOUR

strike ä INVASION & AMBUSH

deadly ä LETHAL & FATAL ACTIVITIES

terrible message ä HORRENDOUS & APPALLING

pay the price ä REVENGE & RETALIATION

proxy war ä ABUSE & DECEPTION

destruction ä DEVASTATION & DEMOLITION

nuclear weapon ä APOCALYPTIC REPERCUSSIONS

peace keeping forces ä AMIABLE & GENIAL SOLDIERS unthinkable

consequences ä APOCALYSE & ARMAGEDDON

endless ä EVERLASTING & PERMANENT

fighters ä FORTHCOMING WAR

explosion ä DESTRUCTION

Muslim Forces ä TERRORISTS

hijackers ä CRIMINALS

train ä ANIMALS

spark ä PROVOCATION & ANTAGONIZING

wave ä EPIDEMIC

Note. Euph.=Euphemization, Derog.=Derogation So based on the presumed effect of the words on the audience and their connotations, presented in the table, it is revealed that the speakers throughout the movie have used every possible derogatory word to hijack the truth and vilify the Iranians.

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 11 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

4. Discussion Response to the first research question: Using the CDA framework (Van Dijk, 2004), in analyzing the movie revealed an extensive use of the semantic discursive strategies of positive self-representation and negative other-representation by the movie producers which was made possible through other discursive strategies such as actor description, derogation, euphemization, and evidentiality. Negative other-representation as a semantic macro-strategy which is usually complimentary to positive self-presentation has been used to enlarge the Iranians’ deficiencies or even ordinary characteristics (them). Throughout the movie, the speakers have repeatedly used derogatory terms and phrases which are usually accompanied with other semantic strategies like lexicalization, hyperbole, irony and polarization. In the Iranium the Iranians are bombarded with a wave of malicious remarks and contemptuous assertions. Using a derogatory term such as ‘defiant president’, in the beginning of the film, to describe the Iranian president who is the representative of a nation establishes the tone of the film which soon proves to be belligerent and aggressive. The speakers have used the same trend of negative other-representation through the use of ideologically laden derogatory terms such as Iranian regime, sponsor of terror, violator of human rights, extreme doctrine, hostage, International terror, struggle, Iranian government terrorist, strike, deadly, terrible message, pay the price, Death to America, destruction of nations, suffer unthinkable consequences, leading sponsor of terrorism, endless number of proxy organizations, hijackers, train, fighters, spark, wave of global Islamic terrorism to construct and disseminate the idea of Iranophobia. The mechanisms of manipulation in the discourse of this movie have been proved to be dramatically manifested in the derogatory and ideologically laden terms. Response to the second research question: Ideology is simply a “system of ideas, beliefs, values, attitudes, and categories by reference to which a person, a group or society perceives, comprehends and interprets the world” (Oktar, 2001: 313-14). In this sense, ideologies define a person’s position in the society and their perspective toward the world. According to Van Dijk (1995b) an ideology is a self-serving schema or a frame for the representation of us and them as social groups, and reflects the fundamental, social, economic, political and cultural interests or conflicts between us and them. Van Dijk (1995a) believes that a theory of ideology should be multidisciplinary and his approach to ideology relates cognition, society and discourse together. Ideologies play an undeniable role in the symbolic field of thought and belief, i.e. cognition, and they are usually associated with group interests, conflicts or struggles. The primary functions of ideologies in a society such as manipulation and concealment are mostly discursive social practices; therefore, language plays a significant role in the expression and the reproduction of ideologies. Owing to the fact that language performs within the social systems and institutions, it tends to reflect and construct ideology. (Van Dijk, 1995b). Therefore, to understand what ideologies are and how they work, it is necessary to “investigate their discursive manifestations for the fact that discursive practices are embedded in social structures, which are mostly constructed, validated, naturalized, evaluated and legitimized in and through language, i.e. discourse” (Rahimi & Sahragard, 2006:129). Within the framework of this article, (Van Dijk, 2004), the in-group favoritism vs. out-group derogation was investigated in the selected movie to demystify the relations between discourse and ideology as represented in the euphemization and derogation procedures in the discourse of the movie. The viewers make general inferences based on such discourse and construct mental models of Iranians as Muslims and terrorists. Then they generalize these inferences with their own basic opinions about the related ideological groups. Therefore this article has made an attempt to investigate the significant role of the media in reproduction and dissemination of ideologies among people with a focus on the anti-Iranian sentiment in Western movies. 5. Conclusion The findings revealed that the producers of the Iranium, made an extensive use of the perplexing power of the semantic components of the language in their arguments to support or reject an ideology. It was also proved that the production of an argument, according to Rahimi and Sahragard (2006), is truly affected by the positive and negative meanings of the words and their impact on the audience. The breakthrough made in this research substantiated the claim that Critical Discourse Analysis is the proper way of detecting the hidden ideologies of discourse and revealing the discursive structures and manipulative language of the speakers/writers. The dichotomy of in-group vs. out-group, based on the Van Djik’s framework (2004), proved to be a very effective discursive strategy at the disposal of the movie makers. It also showed that language can be used as a weapon to attack a nation and represent a distorted and unrealistic image of their history, culture and ideologies. The huge

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 12 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

power of the words in appealing to emotions, manipulating one’s thought and behavior and misrepresenting the realities has manifested itself in the CDA conducted on the discourse of the selected movie. The manipulation of the audience into believing the speakers’ ideologies and distortions of the facts have been masterfully attained in this movie and it was revealed that the main purpose of the movie makers had been the naturalization of such ideological attitudes into the subliminal knowledge of the viewers. The findings of this study, thus, add to the bulk of research done in the field of CDA and suggest the pervasiveness of these strategies in the discourse of the media. References Bruno, G. & Beehner, L. (2009). Iran and the future of Afghanistan. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from http://www.cfr.org/iran/iran-future-afghanistan/p13578. Campbell, J. (1997). Portrayals of Iranians in U.S. motion pictures. In Y. R. Kamalipour (Ed.), The U.S. Media and the Middle East: Image and Perception (pp. 176-186). Westport, CT: Praeger. Christian, M. (2008). KABOOM! - world's biggest non-nuclear explosions. Retrieved from http://www.darkroastedblend.com/2008/11/ kaboom-worlds-biggest-non-nuclear.html. Clifton, E. & Gharib, A. (2011). Iranium or: how I learned to stop worrying and love the ‘military option’. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/iranium.html. Commission Report/ 9-11. (2004). National commission on terrorist attacks upon the united states. Retrieved from http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/index.html. Dabashi, H. (2006). Native informers and the making of the American empire. Al-Ahram Weekly. Retrieved from http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2006/797/special.html. Dines, G. & Humez, J. M. M. (eds). (1995). Gender, race, and class in media. A text-reader. London, CA: Sage Publications. Ebert, R. (1991). Not without my daughter. Retrieved from http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19910111/REVIEWS/101110303/103. Explosively Formed Penetrator. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Explosively_formed_penetrator. Fairclough, N. (1995). Media discourse. London: Edward Arnold. Fairclough, N. L., and Wodak, R. (1997). Critical discourse analysis. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Discourse Studies. A multidisciplinary introduction. Vol. 2. Discourse as Social Interaction. (pp. 258-284). London: Sage Publications. Hall, S., Hobson, D., Lowe, A., & Willis, P. (eds). (1980). Culture, media, language. London: Hutchinson. Hamelink, C. J. (1997). New information and communication technologies. Social Development and Cultural Change, 86, Retrieved from http://dare.uva.nl/document/14111. Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: the political economy of the mass media: Random House. Kaplan, R. B. (1990). Concluding essay: on applied linguistics and discourse analysis. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 11(1), 199-204. Kress, G., & Hodge, B. (1979). Language as ideology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images: the grammar of visual design: London, Routledge. Liebes, T. & Katz, E. (1990). The export of meaning: cross–cultural readings of “Dallas”. New York: Oxford University Press. Miller, B. (2007). Does Hollywood have a negative impact on the world? Retrieved from http://www.helium.com/items/432855-does-hollywood-have-a-negative-impact-on-the-world. Mundy, J. (2011). The issues behind the controversy. Retrieved from http://www2.canada.com/ottawacitizen/story.html?id=cdd5ff44-ef78-4f8c-bf54-77c907b80ca8. Oktar, L. (2001). The ideological organization of representational processes in the presentation of us and them. Discourse & Society. Vol 12(3): 313-346.

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 13 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Ordibehesht, S. (2011). Iranium: A malicious and contemptible absurdity paraded as documentary. Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/notes/sassan-ordibehesht/iranium-a-malicious-and-contemptible-absurdity-paraded-as-documentary/ 162627503786568. Policy of Iran's Supreme Leader in Past 22 Years. (2012). Farsnews.com. Retrieved from http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13901118000986. Porter, G. (2008a). Bush’s Iran/Argentine terror frame-up. The Nation.com. Retrieved from http://www.thenation.com/article/bushs-iranargentina-terror-frame. Porter, G. (2008b). Documents linking Iran to nuclear weapons push may have been fabricated. The RawStory.com. Retrieved from http://www.rawstory.com/news/2008/IAEA_suspects_fraud_in_evidence_for_1109.html. Porter, G. (2009). Investigating Khobar Towers: how a Saudi deception protected Bin Laden. Dissident Voice.org. Retrieved from http://dissidentvoice.org/2009/06/investigating-khobar-towers-how-a-saudi-deception-protected-bin-laden. Rahimi, A., & Sahragard, R. (2006). A critical discourse analysis of euphemization and derogation in e-mails on the late Pope. The linguistics journal, 1(2). Rahimi, A., & Sahragard, R. (2007). Critical discourse analysis. Tehran: Jungle Publications. Religion, 1638-Present. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h3817.html. Slavin, B. (2005). Iran helped overthrow Taliban, candidate says. USAtoday.com. Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/2005-06-09-iran-taliban_x.htm. Van Dijk, T.A. (1995a). Discourse analysis as ideology analysis. Language and Peace, 17, 33. Van Dijk, T.A. (1995b). Ideological discourse analysis. New Courant, 4(1), 135-161. Van Dijk, T.A. (1997). The study of discourse. Discourse as structure and process, 1, 1-34. Van Dijk, T.A. (2003). 18 critical discourse analysis. The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, 18, 352. Van Dijk, T.A. (2004). From text grammar to critical discourse analysis. Retrieved from http://www.discourses.org/download/articles. Van Leeuwen, T. (1998). It was just like magic--a multimodal analysis of children's writing. Linguistics and Education, 10(3), 273-305. Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge. Van Zoonen, L. (1994). Feminist media studies. London: Sage Publications.

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 14 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

The New Development of the Study of Discourse Anaphora ------Review of Discourse Anaphora: A Cognitive-Functional

Approach Meixia Li (Corresponding author)

School of English Language, Literature and Culture, Beijing International Studies University No. 1 Nanli, Dingfuzhuang, Chaoyang District, Beijing, 100024, China

Tel: 86-10-6574-2856 E-mail: [email protected]

Received: 05-05- 2012 Accepted: 07-07- 2012 Published: 03-09- 2012 doi:10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.5p.14 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/ijalel.v.1n.5p.14 The research is financed by Funding Project for Academic Human Resources Development in Institutions of Higher Learning Under the Jurisdiction of Beijing Municipality No. PHR201006131 & Research Planning Fund Project of China Ministry of Education, the Humanities and the Social Sciences No. 12YJA740039 1. Introduction The English word anaphora is derived from the Greek word ἀναφορά, meaning carrying back. For a long time anaphora has been the object of research in a wide range of disciplines, such as rhetoric, philosophy, theoretical linguistics and so on. A great number of remarkable achievements have been made in these fields. In the 1970’s there was a “discourse turn” in the domain of the humanities and the social sciences, which marked the birth and flourishing of such cross-disciplines as psycholinguistics, computational linguistics, cognitive linguistics, corpus linguistics, discourse studies and so on, and which also paved the way for the turn of the study of anaphora from focusing on intrasentential anaphora to intersentential anaphora. Intrasentential anaphora refers to the relationship between a pronoun and its antecedent being contained within one sentence, while intersentential anaphora can also be called discourse anaphora, which refers to “the relationship between a pronoun and its antecedent earlier in the discourse” (Clark & Parikh, 2006, p. 1). From the late 20th century on, discourse anaphora has become one of the hot topics in several fields such as psychology, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, etc. Many fruitful research results (i.e. Huang, 2002; Clark & Parikh, 2006, etc.) have been obtained. Ming-Ming Pu’s monograph Discourse Anaphora: A Cognitive-Functional Approach, published by LINCOM GmbH in Muenchen, Germany in 2011 is another important work of the study of discourse anaphora. In this book, the author first proposes a cognitive-functional model to account for how the construction of mental structures determines the use and resolution of discourse anaphora. Afterwards he does a comparative quantitative study of both English and Chinese empirical and text data, which demonstrates that on the one hand the occurrence and distribution of discourse anaphora is more universal in nature than language-specific, and on the other hand that the proposed model is adequate, feasible and workable. This book suits such readers as university teachers, graduate students and researchers who are interested in the study of anaphora, cross-linguistic studies, discourse analysis, and language teaching and learning. In the following I shall review each chapter and then offer my evaluation. 2. Chapter overview This monograph contains 7 chapters. In the introductory chapter, the author first situates discourse anaphora in a new perspective. Discourse anaphora is not held as a static product or entity linked to its linguistic antecedent in a text but as a manifestation of cognitive processes of memory and attention, and of building discourse coherence and maintaining local and global topics, along with the tacit cooperation between speakers and hearers. Against this background this chapter aims to construct a cognitive-functional model to account for the use and resolution of discourse anaphora. Then, the scope of the book, the categorization of anaphora and the overview of the book are given sequentially. This introduction sets the anchoring point, establishing the structure of the book and providing readers with contextual information so that they have the necessary knowledge about the present research topic.

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature

ISSN 2200-3592 (Print), ISSN 2200-3452 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 5; September 2012 [Special Issue on General Linguistics]

Page | 15 This paper is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.