'“If I could see the Puppets Dallying”: Der Bestrafte Brudermord and Hamlet’s Encounters with...

Transcript of '“If I could see the Puppets Dallying”: Der Bestrafte Brudermord and Hamlet’s Encounters with...

“If I could see the Puppets Dallying”: Der Bestrafte Brudermordand Hamlet’s Encounters with the Puppets

Tiffany Stern

Shakespeare Bulletin, Volume 31, Number 3, Fall 2013, pp. 337-352(Article)

Published by The Johns Hopkins University PressDOI: 10.1353/shb.2013.0051

For additional information about this article

Access provided by Oxford University Library Services (16 Jan 2014 12:11 GMT)

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/shb/summary/v031/31.3.stern.html

“If I could see the Puppets Dallying”: Der Bestrafte Brudermord and

Hamlet’s Encounters with the Puppets

Tiffany STern

Oxford University

Two critics mention an extraordinary manuscript in Germany: an ancient, farcical puppet text that tells the story of Hamlet. Writes Su-san Young, “As early as 1626 a version of Hamlet for marionettes was performed in Europe; first in Dresden, then in Hamburg, Gdansk, and Frankfurt;” she footnotes “The small format 13 page ms was found in a German monastery in 1710, and was published 1781” (Young 9). A ver-sion of this information, with varied dates, is provided by Barasch; she too refers to “a thirteen-page plot outline of a Hamlet puppet show,” and also dates this text ultimately to 1626, though she maintains that it was not published until 1785 (Barasch 175). Both trace their information to a common source: an Italian article by the doctor and puppeteer, Nino Amico; both also record, however, that Amico’s information is taken from another writer, Ingrid Hiller. Barasch tries to trace Hiller’s actual work, but is unsuccessful: “Amico […] dates Hiller’s study in 1964 but gives no citation […] I have been unable to locate [it]” (Barasch 175). This essay will explore the text to which Amico, ultimately, is referring; tell its story; and ask whether there is, indeed, a surviving German puppet text for Hamlet.

To begin with Amico’s article. The 1981 piece, published in Italian, has this to say:

The present note doesn’t presume to furnish a complete account of the use of Shakespearean dramaturgy for puppets; however going back in time […] we find a date that has been the object of study of Ingrid Hiller, in-structor from the University of Catania, which seems to me useful to cite. In 1710, in the monastery of Preez in Germany, thirteen pages containing

Shakespeare Bulletin 31.3: 337–352 © 2013 The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tiffany STern338

a draft with the title Der Bestraftebrudermord [sic!] oder Prinz Hamlet aus Dänemark […] were found in a manuscript of small-format. The studies of the author [Hiller] explain that the work is not a translation but a free adaptation made from recollections of some parts with the addition of segments characterized by their crass humour—probably concessions for the public who enjoyed a vulgarly conducted and staged comic genre. The first representation is documented for the year 1626 in Dresden; subse-quent ones were in Hamburg, Danzig and Frankfurt. The manuscript was published in 1781 (Hiller 1964)” (Amico 98).1

The facts of the matter, then, are disappointing: immediately it is clear that there is no new, hitherto unknown text to be found; rather, Amico, presumably in the wake of Ingrid Hiller, has implied that a known Ger-man play, Der Bestrafte Brudermord, was written for puppets.2 Yet this assumption raises questions not asked elsewhere. Generally what is taken to be of interest about Der Bestrafte Brudermord, a farcical descendant of Hamlet in German that contains “no grace, no charm, no poetry” (Bren-necke 252), is its bearing on Shakespeare’s play: does it come from the Ur-Hamlet and give us a trace of that text; is it an echo of an intermediate Shakespearean Hamlet not otherwise surviving; or does it, with its Co-rambus character, and its arrangement of the “nunnery” sequence come from Hamlet Q1, or, with its section of Claudius’ speech of 1.2 (missing in Q1) come from Hamlet Q2?3 Critics have focused least, then, on the elements that are clearly added to the play: flying entrances from above; slapstick fights; flashes of lightening and bursts of gunfire; bouts of un-necessary illness. These details, however, may explain why the text was altered, and that might help define what the base text was.

It is important, then, to start by providing what is known about the manuscript of Der Bestrafte Brudermord before exploring its internal features. This, however, is surprisingly hard to do: much on the play is only written in German, and few writers either in German or English reach agreement about the sparse information available. Here, then, is as full a picture as I have managed to acquire of the manuscript’s actual, and potential, heritage, some of which may—but may not—be internally confirmed by incidents in the play itself.

Der Bestrafte Brudermord oder: Prinz Hamlet aus Dännemark was first brought to public attention in 1779, when extracts of it were published in Theater-Kalender auf das Jahr 1779, by its editor H. A. O. Reichard. Two years later, in 1781, Reichard published the play in full in his periodical Olla Potrida, where he hailed it as “Eine alte deutsche Bearbeitung des Englischen Originals,” “an old German adaptation of an English origi-

“if i could See The puppeTS dallying” 339

nal” (Reichard, Olla Potrida 167). We thus have two published texts for it; one partial, one full, but as both are supplied from the same source, they merely double information. Reichard also provided the very minimal additional information that he had for the text in his possession: that it was dated “Pretz, den 27. Oktober 1710” (Theater-Kalender 47), and came from actor-manager of the Gotha Theater, and early theater historian, Konrad Ekhof (1720–1778), who had recently died.

The manuscript of Der Bestrafte Brudermord has subsequently disap-peared, seemingly for good. Creizenach, publishing the text in 1888, maintained that it was nowhere to be found (Creizenach 128). In the 1950s Ernest Brennecke made strenuous attempts to find it; he made enquiries of E. K. Chambers whose writing suggested he had seen it, and searched in a number of German libraries. Ultimately he was told by the librarian of the Landesarchiv at Gotha that “it has been lost through the exigencies of war” (Brennecke 251). That means that its appearance, dimensions, and handwriting are unknown—unless the mysterious Ingrid Hiller, who gave the text thirteen sides, a small size, a place in a larger document, and, interestingly, a name reflective of early German spelling, had in fact come upon the manuscript in the 1960s, or had read about it in a source I haven’t located.

The sole piece of additional information about Der Bestrafte Brud-ermord, place and date, “Pretz, den 27. Oktober 1710” is also hard to interpret. The year 1710 obviously precedes publication by seventy years, but the play that follows appears to be, in origin, much older than that: Hamlet Q1 was not to be (re)discovered until 1823, yet as Furnivall sneered, at the expense of both texts, “a German writer got hold of the messt Quarto of 1603, and made a further mess of it” (Furnivall xi). Thus what we seem to have is a 1710 copy and/or adaptation of a much earlier play. “Pretz,” too, needs to be unpacked. What made Amico/Hiller main-tain that Pretz was a monastery seems to have been an article in Jahrbuch der Deutschen Shakespeare-Gesellschaft, which suggests the word stands for “Kloster Preez,” Preetz Priory (Gersdorff 148).4 As “Kloster Preez” was in fact an aristocratic nunnery—not a usual site for copying or storing dramatic material—this is likely to have been a simple misinterpretation. Most other scholars have assumed Pretz is, in fact, a town, though they have not reached consensus as to which. Suggestions have ranged from Gräz (in Steiermark), to Pretzsch (in Sachsen), to “Preetz” (in Plön, Schleswig-Holstein, site of the nunnery, but also of a surrounding town) (Ward 2:163; Pietsch-Ebert 12; Isaacs xvi). The latter, though, is the most likely and provides an explanation for the date of the manuscript, and the

Tiffany STern340

way that the actor Ekhof acquired it. Ekhof had married Georgine Sophie Spiegelberg; Georgine’s father, Johann Christian Spiegelberg, had started a theater company that performed in Preetz in 1710 (Widmann 17).

Spiegelberg had, moreover, up until 1710, been performing in a com-pany run by actor-manager Johannes Velten (1640–92/3). A further heritage for the text can, then, be tentatively guessed at. Spiegelberg might well have been copying, though perhaps also adapting, a man-uscript from his erstwhile mentor. This is likely, as Velten, a famous university-educated actor, prided himself on his German adaptations of foreign plays. His productions had included German versions of works by Molière, Corneille, and Calderon as well as Shakespeare. Moreover, in September 1686, in Frankfurt, Velten’s troupe had even performed a Hamlet play for which a playbill was once said to have survived, though it too is now lost; that play is variously said by critics to have been called Hamlet, and to have been called Der Bestrafte Brudermord.5 The text of Der Bestrafte Brudermord, as we have it, may come directly from a Velten heritage. Indeed, it may even boast as much. When the frightened sentry, seeing a ghost on the battlements, says “Oh, Saint Velten, if only this watch were over, I’d run off from this post like any rascal” (1.2.2–4), 6 he beatifies a name not otherwise so distinguished. Though Saint Valentine was occasionally shortened to “Velten” or “Felten”, that was for phrases such as “Potz Velten!” or “Dass dich der Velten!” imprecations that, tak-ing up from Saint Valentine’s fabled epilepsy, denoted delirium tremens, epilepsy or demonic possession (Hampson 164). The wish that the saintly, or demonic, Velten might aid the Sentry to escape, then, may be a meta-theatrical reference to Johannes Velten.

An incident in the play as we have it, moreover, supplies, potentially, a yet earlier heritage for aspects of the text. Velten had married Catherina Paulsen; his father-in-law had been Karl Andreas Paulsen (1654–1685) (Emde 7), one of the first theater managers to emerge after the Thir-ty Years War (1618–48), and a man who regularly acted plays that he had inherited from what were called “Die Englischen Komödianten,” “the English Comedians”. Der Bestrafte Brudermord may contain verbal traces of having once been performed by Karl Paulsen and his company. The visiting players, for instance, are led by a principal player whose name is “Karl,” and who says to Hamlet “Wir sind fremde hochteutsche Comödianten” (“we are foreign High-German players,” 2.7.4–5). As Karl Paulsen’s company had been known as the “Hochteutsche Comödianten” (“the High-German players”) this seems a probable Karl Paulsen refer-ence (Freudenstein 28–9). The possibility is, then, that a play initially

“if i could See The puppeTS dallying” 341

brought to Germany by “the English Comedians” was taken on by Karl Paulsen, inherited by Johannes Velten, copied by Johann Spiegelberg, given to Konrad Ekhof and published by Reichard—with adaptations, changes and alterations happening along the way, of course.

So far, none of this appears to make the puppet story very likely. But what kind of productions were the German actors named above putting on? And who were the English Comedians, and what were they playing that either “Karl” inherited or that Velten, or Spiegelberg—and certainly Ekhof—acquired?

From at least the 1590s onwards, English acting companies took to the Continent for money and fame. At a time when English theatres regularly closed because of the plague, there was every reason to avoid poverty by performing abroad; besides, English actors were often in-vited overseas by influential noble patrons such as Heinrich Julius von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel or Moritz von Hessen-Kassel (Limon 1–33; Haekel, Englischen Komödianten 15–79). German scholars have written more about English Comedians than scholars of other countries, though in fact the English players also performed all over Northern Europe, including the Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Po-land and Bohemia. Surviving information about Robert Browne, and the host of actors he took around Europe between 1590 and 1620 provides just one such example (Katrizky). These players put on popular dramas from England. There are records of German performances of The Spanish Tragedy, Dr Faustus, The Jew of Malta amongst others; hardy Shakespeare favorites included Julius Caesar, Lear, Othello and, surprisingly, The Com-edy of Errors (Brennecke 9); Romeo and Juliet was regularly performed in Dresden (Siedler 180–1).7 The companies played at first in English. Fynes Morison recalls being in Frankfurt in c. 1592 and seeing “some of our cast dispised Stage players come out of England” perform there: “the Germans, not understanding a worde they sayde, both men and women, flocked wonderfully to see theire gesture and Action, rather then heare them, speaking English which they understoode not” (Moryson 304). He caught up with a similar—or perhaps the same—company of “cast Players of England” in Switzerland, who “the people not understanding what they sayd, only for theire Action followed them with wonderfull Concourse” (Moryson 373). In order to make performances work without a common language, the English Comedians used a number of exigen-cies: sometimes they preceded their acts “mit stummen Personen”—with dumb-shows that revealed the story; sometimes they handed the audience an “argument” or paper plot that informed them of the story to follow

Tiffany STern342

(Stern 274). Sometimes they sought out a bilingual clown to present and explain the play. There were, for instance, “Englishmen” who acted “five different comedies in their English language” at Munster on twenty-sixth November (1599): “They had with them a clown, who, before each Act […] spoke much nonsense in German, and played many pranks to make the people laugh” (Cohn cxxxiv). These, however, were short-term remedies: the transition to native languages, at least in the case of Ger-man and Dutch speaking countries, appears to have happened late in the sixteenth century. There is a reference to performing plays in German as early as 1596 (Haekel, ‘Neue’ 2004); there are no definite accounts of English language performances in Germany after 1606 (Brennecke 5).

A 1620 publication, Engelische Comedien und Tragedien, published anonymously, but probably by Frederick Menius, shows the kinds of plays that had made their way to Germany, and hints at what they may have become after a few years of performance—though whether Menius’ texts are associated with a particular theatre company is frustratingly unclear. The book contains seventeen pieces including the plays Fortunatus, A King’s Son of England and a King’s Daughter of Scotland, Nobody and Some-body, Sidonia and Theagenes, Julio and Hyppolita, and Titus Andronicus, all in German. In its title-page it boasts that what may be loosely translated as “these English Comedies and Tragedies” are “very beautiful, splendid, and select spiritual and worldly comic and tragic plays, which…have been acted and performed by the English in Germany, at royal, electoral, and princely courts”. 1630 saw the publication of Liebeskampff oder ander Theil der Englischen Comoedien und Tragoedien, containing six more German plays and two “Singspiele” (jigs) though it is possible, as Price maintains, that this collection was written for the page. Other free-floating German versions of English texts also survive, roughly traceable to the period. There is, for instance, a manuscript, c. 1688, of Tragaedia von Romio und Julietta preserved in the Vienna Nationalbibliothek (a printed Dutch text of that same play from 1634 shows the English Comedians’s equal success in Holland), and a printed text, Kunst über alle Künste, from 1672, preserves a version of Taming of the Shrew. Holland, meanwhile, also has a 1650 Midsummer Night’s Dream, a 1654 Taming of the Shrew, and a 1641 Titus Andronicus that has been described as “an offshoot of Titus Andronicus […] at second remove, via a coarse German fairground paraphrase” (Westerweel 143). So the existence of a Hamlet text, in Ger-man, and traceable in some way to seventeenth century performance, is no surprise: it, or another version of the play, was apparently recorded in a diary kept by an officer of the Dresden court which listed plays performed

“if i could See The puppeTS dallying” 343

by “the English actors;” on twenty-fourth June there was a performance of “Tragoedia von Hamlet einen printzen in Dennemarck” (Cohn gives a date of 1626 for this entry, cxv; Schindler dates it to 1688, 131).

The story less often told, however, is of the exigencies that might affect a sizable troupe of English players abroad. To perform their plays, English Comedians were reliant on a substantial number of talented English ac-tors—even their cut-down dramas required between twelve and sixteen players ( Jurkowski 151). These actors were expensive to clothe and house; moreover, as they travelled, they had a tendency to drop away, lured by love, yielding to disease, or choosing to return to England. Up to a point, they could be replaced by German, Dutch, Swiss or other players—but replacements required training, and were often then called up, as were the English players themselves, for army duty during the Thirty Years War ( Jurkowski 149).

Companies had, however, a range of options available to them. Though it is seldom written about, there had long been a tradition, in England, of making puppet versions of major theatrical characters. Every Woman in her Humor (1609), sig. H1r, for instance, has a reference to the entire play of “Julius Caesar acted by the Mammets,” and a surviving puppet playbill of unclear date—suggestions have ranged from 1650 (Lennep 382–5) to 1670 (Speaight 152, 295)—advertises puppets who can per-form a selection of plot moments and characters from a range of early modern dramas, including Henry II, Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, and The Late Lancashire Witches (reproduced Speight 151). Sometimes the puppet versions of actor-characters enacted further dramas, suggesting that, in puppet-form, noted tragic characters were expected to have a further (non-literary) afterlife. Chettle and Day’s The Blind Beggar of Bednal Green (1600) refers to a variety of puppet entertainments on of-fer in London: “Gentlemen,” boasts Canbee as “Master of the Motions” (Master of the Puppet shows), “You shall […] see the famous City of Norwitch, and the stabbing of Julius Caesar in the French Capitol by a sort of Dutch Mesapotamians […].Or if it please you shall see a stately combate betwixt Tamberlayn the Great, and the Duke of Guyso the less, perform’d on the Olympick Hills in France” (Day G2v). As Chettle and Day also illustrate, puppets required or brought about certain types of situation: combats and violence were a puppet-staple.

Polish and Czech scholars, who are conscious of puppet activities, perhaps because their native puppets have retained an important cultural role, take it as a given that the English Comedians “turned to puppets in order to survive” ( Jurkowski 149). Germans have written about it far less,

Tiffany STern344

even though accounts survive of the puppets left behind by the English players when dismissed from Saxony in 1631, for instance (Rudin 3). Carl Riessen has, however, drawn attention to the earliest surviving “Faust” puppet show explaining how it relates to Marlowe’s Dr Faustus; he has suggested that other puppet shows of the period might have come from the English Comedians—though the puppet version of Hamlet he knew of was of a later date and not connected to Der Bestrafte Brudermord (470).8 Creizenach, meanwhile, suggested that the English Comedians performed puppet-person medleys, though his reading of the informa-tion has been queried: it was his contention that the type of mainpiece slapstick entertainment by travelling troupes called “Haupt- und Staat-saktionen” (“Haupt” seemingly referring to “high” themes and descending from English and other dramas, and “Staat” referring to political subjects), referred to mixed puppet-person performances ( Jurkowski 150). The habit of combining puppets and actors was certainly employed during the period: surviving pictures from Holland (1627 and 1632) record just such combination performances (reproduced Bourgoingne; Bolswert); the combination was habitual in Germany in 1714 (Rudin 7).

On occasion, obviously, it was simpler to substitute puppets for play-ers altogether. Puppeteer Jan Malík, writing in 1940s Czechoslovakia, thought his country’s puppet heritage descended from this. He main-tained that the “motley strolling companies” of English Comedians often “alternately performed an actors’ and a marionette repertoire” in his native land. He added: “there were also some troupes which engaged exclusively in puppet-plays, among them some former heads of actors’ companies who had lost part of their troupe and were compelled, therefore, to per-form a simplified repertoire by means of marionettes. This is why with the marionettes of those days, we so often find names and subjects of plays reminding of Marlowe (1564–1593), Shakespeare (1564–1616), Molière (1622–1673), and other classics of the theatre” (Malík 7).

It is possible that throughout Europe the English Comedians, and their descendants, according to ability and numbers, performed combi-nations of actor plays, actor-puppet plays, and puppet plays, of English productions. At any rate, that makes sense of the fact that later German actor-managers had extensive puppet plays descending from English dramas: Michael Daniel Treu (sometimes referred to as Drey), when he visited Lüneburg in 1666, had a puppet and person repertoire consist-ing of twenty-five pieces, including Titus Andronicus, Doctor Faust and “Konnich Liar auß Engelandt, ist eine materien worin die ungehorsamkeit der Kinder gegen ihre Elder wirt gestraffet, die Gehorsamkeit aber belohnet”

“if i could See The puppeTS dallying” 345

(“King Lear of England, that is, the Matter in which the disobedience of Children towards their Parents is Punished but Obedience Rewarded”) as well as English historical pieces such as Cromwell ’s Ghost (Boehn 63);9 and Weltheim (Veltheim) of Leipzig in 1679 formed a troupe of marionettes and comedians who put on plays by Shakespeare and Molière (Batchelder 111)—indeed, Cohn says they put on Der Bestrafte Brudermord, though the date he supplies for this, 1665, suggests he is confusing Veltheim with Velten (Cohn cxx). When plays of the English Comedians or their inheritors are advertised, perhaps we should question whether what is be-ing promoted is a play for puppets or a play for people, not least because exigencies might at any time make the one yield to the other.

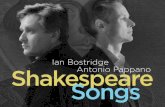

The oddest hint that well-known plays were travelling over Europe in puppet form—or at least that the puppets were—is a puppet himself. “Amleto” (“Hamlet”), said to date from 1667, and to have been carved by Pietro Resoniero (1640–1735) in Vienna, now resides in the basement of “Il Museo dei Burattini di Zanella Pasqualini,” “Zanella Pasqualini’s Museum of Puppets”. Amleto, who long precedes the formal translation of Hamlet into German or Italian, is said to have been made for Austria’s first permanent marionette theater at the Judenmarkt in Vienna; he thus crops up on the path taken by the English Comedians and their descen-dants. Some caveats about his origin, however, are supplied by Zachary Lesser who kindly visited Amleto’s owner, and sent me fig.1, which il-lustrates a “Yorick” (a puppet skull) being lowered into Amleto’s hand: “How exactly [Vittorio Zanella] knows that it is Hamlet he couldn’t quite explain. I tend to think he’s right because he is completely obsessed and has been studying them and performing as a burattinaio (puppeteer) for 30 years or so. But I don’t think there’s any real documentation of it.” That this is Hamlet relies on one’s reading of his black clothes, the bending mechanism at the knees that allows him to kneel in front of his father, and the skull-receptive hand. Yet the existence of a seeming Hamlet at this period both confirms what puppet scholars have independently been suggesting, and hints excitingly that records of the English Comedians or their descendants may be extant not in documentary, but in puppet form.

Putting all this information together, Amico/Hiller’s suggestion that Der Bestrafte Brudermord is a puppet text becomes at least half-possible. Given the nature of early modern travelling players and their texts, Der Bestrafte Brudermord may record not a puppet text per se, but a text with traces of having been, at some stage, reworked or reshaped for puppet reasons. What, in the text, may suggest this?

Tiffany STern346

Der Bestrafte Brudermord starts with a dialogue prologue that bears no relationship to any of Shakespeare’s Hamlets. It serves the purpose of in-troducing the story of the play and is perhaps a leftover of an “argument”: “the King of this country, burning with love for his brother’s wife, has murdered his brother for her sake, in order to win both her and the king-dom. Now the hour has come for him to celebrate his nuptials with her” (Prologue, 28–31). It is spoken by four women who do not then feature in the play that follows, Night, Alecto, Maegera, Thisiphone. As, however, the rest of Der Bestrafte Brudermord features only two women, the Queen (Sigrie) and Ophelia, the prologue raises immediate casting difficulties for a stretched company of actors: two additional women (or, depend-ing on period, boys dressed as women) will have had to be acquired for

Fig.1. ‘Amleto’ carved by Pietro Resoniero (1640-1735) from The Collection of Zanella-Pasqualini. Photo: Zachary Lesser

“if i could See The puppeTS dallying” 347

the purposes of this short exchange. A second problem is the prologue’s complex staging. Night enters from above (1), and at the end, “ascends” (48) above again, requiring some kind of flying mechanism, or a secured chair that can be lowered from a ceiling; the three Furies are instructed “up, up, come forth” (11) from below requiring a trap door. Yet neither “above” nor “below” are used in the subsequent play—it is notable, indeed, that the Ghost cries “swear” from “within” (1.6.25–32) rather than, as in the Shakespeare Hamlets, from below, and that Ophelia has no funeral, so that the trap-door is not necessary. The prologue, finally, is very spe-cific about its own night-time setting, opening with “I am the darksome Night” (1). Though Hamlet, of course, starts at night, prologues do not usually mirror the fiction of the play to come, particularly when, as here, they do not feature the play’s characters. All this may, of course, suggest that the prologue belongs to some other play and has been adapted and latched onto this one, as is quite possible. But the prologue to Der Be-strafte Brudermord would also be a good puppet prologue. With puppets, supplying additional characters, female or male, is easy: they are simply pulled out of the bag. Flying and sinking too, which asks a lot of strolling players on makeshift stages, was almost a requirement for puppets—the easiness with which puppets can rise and sink indeed is the reason why their stories so often have supernatural and ghostly elements. Even the night-time prologue may have a puppet cause: while actors tended to perform in the light, puppet shows were put on in the dark to render the puppeteer less visible: as Ben Jonson explains “A Puppet-play must be shadow’d, and seene in the darke: For draw the Curtaine, Et sordet gesticulatio [and the action is disgusting]” ( Jonson 91).

Within Der Bestrafte Brudermord itself are features that were favored by puppets, starting with the play’s very length. A fifth as long as the ‘good’ Hamlet (Q2/F), Der Bestrafte Brudermord consists of tiny scenes, some lasting for as little as a short speech. Fast entrances and exits, easy with puppets, do not favor actors, who need to walk to exits in order to go offstage, and who are in danger of bumping into entering characters the whole time. Moreover, brief though it is, the script does also add a lot of action to the play—much of its new events consisting of fight-ing. In addition to the swordfight between Hamlet and the character called, here, Leonhardus, is the violence of the Ghost, who supernaturally boxes the sentry’s ears, and Ophelia, who madly strikes Phantasmo. As already explained, puppet-fights were a favorite with watchers; they also illustrated the skill of the puppeteer: “an expert Puppet-player can at his pleasure make the little Actors chide and fight one with another, and

Tiffany STern348

knock their own heads against the Posts” (Bramhall 9). Several of the play’s slapstick attacks come, additionally, from behind. The Ghost “from behind, boxes the Sentry’s ear, so that he drops his musket” (1.2.7–8); the result, perhaps consciously, is to create a parallel between him and his son Hamlet who, when he thinks of killing the praying king, “moves to stab him from behind” (3.2.8–9), and when he finally does kill him after the rapier match, “stabs him from behind” (5.6.56.1). This position makes sense for a puppeteer, as puppet entrances and actions come from behind, reflecting the fact that the puppeteer was himself situated be-hind the entire show: “You have peradventure heard or seene a Motion, a Puppet-play; how the little Idoles leape, and moove, and run strangely up and downe […] but there is a fellow, behind, which we see not, it is he that doth the feat” (Adams 45).

Fundamental to the entertainment aspect of puppet-shows were squibs and firecrackers; Flecknoe refers to “the Ring-leaders of the Jansenists blown up like Crackers in a Puppet play” (Flecknoe 101). There is one, or perhaps there are two, bursts of cracker fire in the play of Der Bestrafte Brudermord. The first is brought in for the joy of the effect; in literal terms it makes no sense. When the Ghost of Hamlet’s father enters the Queen’s closet, he is accompanied by what is called in the stage direction, “lightning” (3.6.0)—almost certainly created by a lighted cracker as was usual in the period. This lightening adds to the Ghost’s display, but is incomprehensible in play terms, for the Queen is obliged to claim, over the stage effect, that she sees and hears nothing: “What are you doing, and with whom are you speaking?” (3.6.4–5) A further effect requires either additional crackers, or guns with blanks. The two bandits sent to kill Hamlet by the king, are tricked to their deaths. Told by Hamlet to stand on either side of him with their guns so, Hamlet says, as to “hit me squarely, so that I may not have to suffer overlong” (4.1.51–2), they die when Hamlet “ducks down between the two; they shoot and kill each other” (4.1.50.1–2). This pratfall is partly brought in for the purpose of gunshots—it substitutes for the tame swapping of letters in Shakespeare’s Hamlets.

Even one of Hamlet’s reactions just might have come about for puppet reasons. Before the fight with Leonhardus, Hamlet starts displaying signs of illness—a nosebleed yields to an uncontrollable fit of trembling, before finally he faints: “my whole body is trembling! Alas, what is happening to me?” (5.3.29–30). Ill omen as this may be, it also asks for a bodily movement loved by audiences at puppet shows: shaking was a physical activity embraced by the puppet world. “[Her gate] presented the world

“if i could See The puppeTS dallying” 349

with occasion to laugh […] for she gave her whole body a certain shaking, as if it had been a Puppet” (Sorel 31).

Finally, just as there seem to be coy references to Velten and Karl Paulsen in Der Bestrafte Brudermord, there may too be metatheatrical ref-erences to another moment in the life of the play. When Ophelia decides not to bed Phantasmo at once she explains, “No, no, my puppet, we must first go to church together” (3.2.15).

None of these reasons are strong enough to confirm the idea that Der Bestrafte Brudermord was ever a puppet play—and the information sup-plied here about the troupes that owned the play may indeed mitigate against that reading. However, it is telling how often critics seeking to describe the play’s mixture of farce, action and caricature, light upon puppet shows as an analogy: Freudenstein describes the play’s writing method as “Stil des Puppenspiels” (“puppet-show-style”); and Dover Wilson identifies the play’s “spook which boxed the sentinels’ ears and [stands] in the center of the stage opening and shutting its jaws” as the “roistering puppet of Der Bestrafte Burdermord” (Freudenstein 56). This essay has raised the possibility that these critics might in fact be sensing something more literal than they realize.

If Der Bestrafte Brudermord may have aspects of the Puppenspiel em-bedded within it, then the play’s confusion of two Hamlets would have behind it a mixture of actor and puppet concerns. The need for explana-tion, clarity and logic (Q2) combines with a need for action and vigor (Q1): perhaps the two versions of the play were even brought together for this reason—or perhaps a hash of the two was recalled by English players who need not physically have had either. Yet it is the prologue, and the features reminiscent of old-fashioned or “low” theater, often said to be traces of the Ur-Hamlet (in that they do not resemble any of Shakespeare’s Hamlets), which may in particular have at their heart something humbler. At least, as this essay has explained, there are reasons to think that be-hind Der Bestrafte Brudermord need be not so much a Kydian tragedy as a drama shaped by what Hamlet—in the play of that name—dismissed so offhandedly as “puppets dallying” (Hamlet, 3.2.248).

Notes

Many thanks to Nicholas Halmi and Stephanie Dumke for help with transla-tions; grateful thanks, too, to the three anonymous readers to whom this article was sent—their advice and information much improved this piece.

1My thanks to Nicholas Halmi for this translation.

Tiffany STern350

2Ingrid Hiller’s text was never published and is not in the library catalogue for the University of Catania.

3Duthie lists 21 moments when Der Bestrafte Brudermord and Q1 agree (where Q2 differs), and 36 moments when Der Bestrafte Brudermord and Q2 agree (where Q1 differs), though the parallels with Q1, which extend to naming and characterization, could also be said to be more far-reaching. Seidler shows further similarities between Der Bestrafte Brudermord and Q1 and Q2, some side-by-side, and concludes that the text does not simply derive from one text, but from a combination put together from memory—and perhaps information from extant quartos—over time (Seidler 218–228).

4This same article also maintains the play is already lost, and suggests that it disappeared while in the possession of Reichard.

5For the first, see Isaacs (xvi); for the second, see Fürstenau (1: 96). 6All line numbers from Der Bestrafte Brudermord are from Brennecke; transla-

tions are based on this text.7This may be the Robert Browne (or his father), who was accused of show-

ing puppets at Coventry and Norwich in 1638 and 1639, though connections between the two remain speculative (Katrizky 135).

8My thanks to Lukas Erne for translating this text for me.9That Treu used puppets is disputed by Purschke (Puppenspiels 32), but

Jurkowski points out that later puppet shows have exactly the same names, and seem to descend from Treu’s. Under the alternate spelling of his name, “Drey”, his Figurentheater is better attested. Purschke, 1984, 60, refers to a different German puppeteer, Adam Kloss, who boasted in 1666 that he had “Englisches Figurnspill”.

Works Cited

Adams, Thomas. Five Sermons Preached upon Sundry Especiall Occasions. London, 1626. Print.

Amico, Nino. “Shakespeare coi Pupi,” Quaderni di Teatro 13 (1981): 96–101. Print.

Anon. Everie Woman in her Humor. London, 1609. Print.Barasch, Frances K. “Shakespeare and the Puppet Sphere.” ELR 34 (2004):

157–175. Print.Batchelder, Marjorie Hope. Rod-Puppets and the Human Theatre. Columbus:

Ohio State U P, 1947. Print. Brennecke, Ernest and Henry, Shakespeare in Germany, 1590–1700, with Transla-

tions of Five Early Plays. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1964. PrintBoehn, Max Von. Puppets & Automata. Trans. Josephine Nicoll. New York: Dover

Publications, 1972. Print.Bolswert, Boetius A. Voyage de Colombelle et Volontairette. Antwerp, 1627. Print.Bourgoingne, Anton Van. Ghebreken der Tonghe. Antwerp, 1632. Print.

“if i could See The puppeTS dallying” 351

Bramhall, John. Schisme Garded and Beaten Back upon the Right Owners. London, 1658. Print.

Cohn, Albert. Shakespeare in Germany in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. London; Berlin: Asher & Co, 1865. Print

Creizenach, Wilhelm. Die Schauspiele der Englischen Komödianten. Berlin und Stuttgart: W. Spemann, 1889. Print

Day, John. The Blind-Beggar of Bednal-Green. London, 1659. Print.Duthie, George. The “Bad” Quarto of Hamlet. Cambridge: Cambridge U P, 1941.

Print.Emde, Ruth B. Schauspielerinnen im Europa des 18. Jahrhunderts: ihr Leben, ihre

Schriften und ihr Publikum. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1997. Print.Flecknoe, Richard. Enigmaticall Characters. London, 1658. Print.Freudenstein, Reinhold. Der Bestrafte Brudermord: Shakespeares “Hamlet” auf der

Wanderbühne des 17. Jahrhunderts. Hamburg: Cram, de Gruyter, 1958. Print.Furnivall, Frederick J. Shakspere’s Hamlet: the First Quarto, 1603. London: W.

Griggs, 1879. Print.Fürstenau, Moritz. Zur Geschichte der Musik und des Theaters am Hofe zu Dresden.

2 vols. Dresden: Rudolf Kuntze, 1861. Print.Gersdorff, Wolfgang Frh. von. “Vom Ursprung des deutschen ‘Hamlet.’” Jahrbuch

der Deutschen Shakespeare-Gesellschaft, 48 (1912). Print.Haekel, Ralf. Die Englischen Komödianten in Deutschland. Berlin: Freie Univer-

sität, 2004. Print.———. “Neue Quellen zur Geschichte der Englischen Komödianten in

Deutschland.” Jahrbuch der deutschen Shakespeare-Gesellschaft 140 (2004): 180–185. Print.

Hampson, Robert Thomas. Medii Ævi Kalendarium: or, Dates, Charters, and Cus-toms of the Middle Ages. London: Henry Kent Causton and Co, 1841. Print.

Isaacs, J. William Poel’s Promptbook of Fratricide Punished. London: The Society of Theatre Research, 1956. Print.

Jonson, Ben, Timber or Discoveries in The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. London, 1640. Print.

Jurkowski, Henryk. A History of European Puppetry. Trans. Penny Francis. Le-viston, USA: Edwin Mellen Press, 1996. Print.

Katrizky, Peg, “Pickelhering and Hamlet in Dutch art: the English comedians of Robert Browne, John Green, and Robert Reynolds.” Shakespeare in the Low Countries. Ed. Douglas A. Brooks. New York: Lewiston, 2005. 113–40. Print.

Lennep, William van. “The Earliest Known English Playbill.” Harvard Library Bulletin 1:3 (1947): 382–5. Print.

Lesser, Zachary. Message to the author. 18 April. 2011. Email.Limon, Jerzy, Gentlemen of a Company: English Players in Central and Eastern

Europe, 1590 to 1660. Cambridge: Cambridge U P, 1985. Print.Malík, Jan. Puppetry in Czechoslovakia. Trans. B. Goldreich. Prague: Orbis, 1948.

Print.

Tiffany STern352

Moryson, Fynes. Shakespeare’s Europe: Unpublished Chapters of Fynes Moryson’s Itinerary. London: Sherratt & Hughes, 1903. 304. Print.

Pietsch-Ebert. Lilly, Die Gestalt des Schauspielers auf der Deutschen Bühne des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts. Berlin: Emil Ebering, 1942. Print.

Price, Laurence Marsden. “The English Comedians.”English Literature in Ger-many. Berkeley and Los Angeles: U of California P, 1953. Print.

Purschke, Hans R. Die Entwicklung des Puppenspiels in den klassischen Ursprung-sländern Europas. Frankfurt am Main: Eigenverlag, 1984. Print.

Purschke, Hans R. Puppenspiel und Verwandte Künste in der Freien Reichs-Stadt Frankfurt am Main. Frankfurt am Main: Puppenzentrum Frankfurt, 1980. Print.

Reichard, H. A. O. Olla Potrida. 2 vols. (Berlin, 1781. Print.———. Theater-Kalender auf das Jahr 1779. Gotha, 1779. Print.Riessen, Carl. “Das Volksschauspiel und Puppenspiel.” Handbuch der Deutschen

Volkskunde. 2 vols. Leipzig: Roder, 1934. Print.Rudin, Bärbel. “Puppenspiel als Metier. Nachrichten und Kommentare aus dem

17. und 18. Jahrhundert.” Kölner Geschichtsjournal 76. Köln: Historische Mu-seen der Stadt Köln, 1976. 2–11. Print.

Schindler, Otto. “Arlequin im Böhmerwald.” Theater der Region. Ed. Andreas Kotte. Basel: Theaterkultur Verlag, 1995. 129–50. Print.

Seidler, Kareen. Shakespeare on the German Wanderbühne in the Seventeenth Cen-tury: Romio und Julieta and Der Bestrafte Brudermord. Diss. Université de Genève, 2012. Print.

Sorel, Charles, The Extravagant Shepherd. London, 1653. Print.Speaight, George. The History of the Puppet Theatre. London: Robert Hale, 1990.

Print.Stern, Tiffany. Documents of Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge U P, 2009.

Print.Ward, Adolphus William. A History of English Dramatic Literature. 3 vols. Lon-

don: Macmillan and Co, 1899. Print.Westerweel, B. and Theo d’Haen. Eds. Something Understood: Studies in Anglo-

Dutch Literary Translation. Amsterdam and Atlanta: Rodopi, 1990. Print.Widmann, Wilhelm. Hamlets Bühnenlaufbahn. Leipzig: Tauchnitz, 1931.Print.Wilson, John Dover. What Happens in Hamlet. 19th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge

U P, 2003. Print.Young, Susan. Shakespeare Manipulated: The Use of the Dramatic Works of Shake-

speare in Teatro di Figura in Italy. London: Associated University Presses, 1996. Print.