'I Love Jesus Because Jesus Is Muslim': Inter- and Intra-Faith ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of 'I Love Jesus Because Jesus Is Muslim': Inter- and Intra-Faith ...

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttps://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cicm20

Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations

ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cicm20

‘I Love Jesus Because Jesus Is Muslim’: Inter- andIntra-Faith Debates and Political Dynamics inIndonesia

Mega Hidayati & Nelly van Doorn Harder

To cite this article: Mega Hidayati & Nelly van Doorn Harder (2020): ‘I Love Jesus BecauseJesus Is Muslim’: Inter- and Intra-Faith Debates and Political Dynamics in Indonesia, Islam andChristian–Muslim Relations, DOI: 10.1080/09596410.2020.1780389

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09596410.2020.1780389

Published online: 07 Jul 2020.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 6

View related articles

View Crossmark data

‘I Love Jesus Because Jesus Is Muslim’: Inter- and Intra-FaithDebates and Political Dynamics in IndonesiaMega Hidayati a and Nelly van Doorn Harder b

aDepartment of Islamic Politics-Political Science, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta,Indonesia; bDepartment for the Study of Religions, Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC, USA

ABSTRACTThis article discusses the public reactions to a billboard with themessage: ‘I love Jesus because Jesus is Moslem’. A radical Islamicgroup placed the billboard in the Indonesian town of Cilacap in2018 with the goal of discouraging Muslims from attendingevents celebrating Christmas and New Year. We place the inter-religious debates resulting from the billboard incident within thelarger context of Muslim opinions on the figure of Jesus in Islamand Christianity. We furthermore ask how the Indonesian statenegotiates Muslim–Christian interreligious dialogues and how itsintervention influences the opinions of individual religious andcommunity leaders. Our main conclusion is that, in spite of thefact that deeper engagement between the two communitiescould yield stronger forms of cooperation or reconciliation whenincidents of interreligious strife occur, all involved prefer to avoidit. Instead, they aim to maintain an equilibrium that represents thestatus quo. Most Muslim and Christian leaders, for various reasons,remain averse to engaging in deeper conversations, especiallywhen it concerns the role of Jesus in their respective religions.

ARTICLE HISTORYReceived 4 June 2020Accepted 6 June 2020

KEYWORDSIndonesia; interreligious;interfaith dialogue; Jesus;Bible; Qur’an; radical Islam;state politics; FKUB (Forumfor the Promotion ofReligious Harmony); religiousleaders

Introduction

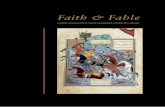

Sometime towards the end of 2018, a billboard appeared in Cilacap, a town in Central Java,stating in big letters: ‘I love Jesus because Jesus is Moslem’, and ‘Tolerance does not equalpluralism’ (see Figure 1). In smaller script, the creators of the billboard explained these twoprovocative statements:

I am a Muslim: I do not celebrate Christmas or the Christian New Year, I do not worship anybut Allah, and I love Jesus/Isa as Allah’s servant and messenger. [The second caliph] Umarbin Khattab said, ‘We are glorified by Allah through Islam, whoever seeks glory besides Islam,Allah will humiliate him.’ Moreover, the Prophet (peace be upon him) said, ‘Whoeverresembles a people is included in his group.’

It did not take long for Muslims, Christians, and the press to take note and react to thebillboard. The local branch of the radical Muslim group, the Islamic Society Forum(Forum Umat Islam; FUI), acknowledged that they had placed the same sign in fourpublic locations, although their chair stressed that they had installed the billboards in

© 2020 University of Birmingham

CONTACT Mega Hidayati [email protected]

ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM RELATIONShttps://doi.org/10.1080/09596410.2020.1780389

cooperation with other Muslim communities. He explained that the aim of this action wasto remind Muslims not to join Christians in celebrating non-Muslim events such asChristmas and the New Year. According to him, the billboards were only meant to‘remind the Muslim brothers’ (Nathaniel 2018). He added that they had put them inonly in four places in Cilacap City, and nowhere else. The issue was not just about the reli-gious holiday of Christmas, but also concerned New Year celebrations, since Muslims andnon-Muslims in Cilacap liked to gather to celebrate together (Susanto 2018).

Indonesian Muslim leaders understand that the statement ‘Jesus is Muslim’ is morethan deeply offensive to Christians as it strikes at the core of Christian beliefs andpoints to the radically different interpretations Muslims have of Jesus’s position as theSon of God, His death and resurrection, and the concept of the Trinity. In their responseto the billboard, many of them tried to keep the fragile balances of religious harmonysteady while staying true to their own convictions about theological concepts they finddifficult to reconcile with the qur’anic principle that God is one.1 At the same time, Chris-tian leaders attempted to steer the conversation to the larger concerns of creating strongbonds between Muslims and Christians, while leaving deliberations about their respectivebeliefs about Jesus to the realm of personal convictions and academic research.

Figure 1. The billboard in Cilacap. Picture: Liputan6.com/Taufik https://www.liputan6.com/regional/read/3858209/dinilai-intoleran-ini-alasan-fui-cilacap-pasang-baliho-jesus-is-moslem

2 M. HIDAYATI AND N. VAN DOORN HARDER

In this article, we trace some of the public reactions to the billboard and attempt toplace them within the field of Indonesian interfaith encounters, in which religious andcommunity leaders influence common opinions. Some struggle to maintain harmoniousrelations between the different religions while others strive to undermine fragile religiousequilibriums, trying to polarize communities. The number of reactions to the billboardwas relatively limited and the issue mostly played out locally. However, many of theopinions voiced and actions taken by local actors raise questions about how nationaladvice and directives about interreligious engagement work out at the grassroots level.The state is an influential stakeholder in this process, which raises the question ofwhether its interventions strengthen interfaith relations or not.

We place the answers to our question within the theoretical frame of reference that dis-cerns different levels of interreligious engagement ranging from the theological and thepolitical, to everyday life. Among others, scholars such as Diana Eck (2007, 754) arguethat the challenge of pluralism lies in three fields, i.e. a challenge for the academy, a chal-lenge for public life, and a challenge for theological thinking and religious communities.The challenge for public life concerns the challenge to the very principles and ideals ofour societies since it concerns who ‘we’ are (760–762). One of our arguments is that,since the interfaith engagement surrounding the billboard controversy was mostlysteered by the government-appointed Forum for the Promotion of Religious Harmony(Forum Kerukunan Umat Beragama; FKUB), it stayed on the level of managing religiousviews with an emphasis on what would benefit local and national politics. Thus, we con-sider whether other levels of interreligious engagement, such as the theological dimension,could help create stronger relations and result in durable platforms of engagementbetween Muslims and Christians.2

In order to gain a better understanding of the local situation, we shall start with adescription of Cilacap, its history, and religious makeup. After discussing the immediatereactions and opinions triggered by the billboard, we shall reflect on some aspects of thefigure of Jesus within Muslim–Christian dialogue, followed by some observations aboutwhat the billboard and its focus on Jesus mean for the ongoing efforts to create effectiveforms of interfaith dialogue in Indonesia.

Cilacap

The first questions that come to mind are: Why were those boards placed in Cilacap andnot in a larger city such as Jakarta or Bandung?What are the specific conditions in Cilacapthat would invite such action?

Since the middle of the twentieth century, Cilacap has had a history of struggling withforms of religious extremism, both Islamic and non-Islamic. During the 1950s, a radicalMuslim group used the town and its surroundings to hide from the government whileat the same time the town saw a rise in its Communist population. For twelve years, itserved as a refuge for the so-called Darul Islam rebellion and hosted members of the extre-mist Darul Islam (or Tentara Islam Indonesia). This group, established in 1949 in WestJava, strove to create an Indonesian Islamic state, and gave rise to ‘one of the greatestworries for the government of the Republic of Indonesia, particularly in the period after1950’ (Boland 1982, 54). Meanwhile, after the Communist party won nearly 16.4% ofthe votes during the 1955 general elections, Cilacap became one of Indonesia’s Communist

ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM RELATIONS 3

hotspots. The party was eradicated after President Suharto replaced President Sukarno in1965–1966. However, until today, the murder of hundreds of thousands of Indonesiansaccused of having Communist affiliations is still a sensitive and open wound in Indonesiansociety. At the same time, Indonesians consider the spectre of Communism, imagined orreal, to be an ongoing threat to society.

Since the fall of President Suharto in 1998, the town has become host to several radicalMuslim groups. Its two million inhabitants are predominantly Muslim (98.49%). Around23,500 are Christian, and around 3,500 practise Hinduism, Buddhism, and indigenousfaiths (Kantor Kabupaten Cilacap 2016). Even though these minority numbers are verysmall, local branches of radical Islamic groups have been actively trying to convince thelocal population of the veracity of their message. For example, during 2017 and 2018,the Cilacap chapter of the Hizbut Tahrir group was very active. Among other activities,it covered the city with banners saying: ‘This is the time for the umma (the Islamic com-munity) to revive itself by introducing the Islamic law (sharia) and the caliphate (Khilafa)’.It was in this social and historical context that the relatively small FUI group tried to rallythe masses and create interreligious tensions related to the celebration of Christmas andNew Year.

On 5 July 2017, a bomb exploded in front of the Office of Religious Affairs (Subarkah2017). Later, in the same location, the authorities found an offensively worded letter, slan-dering certain forms of Islam and vilifying Muslim leaders (Muzaki 2017a). In 2018,groups placed banners across the town attacking the cherished tradition of SedekahLaut (offering gifts to the sea) at the Teluk Penyu beach. The streets leading to thebeach were plastered with texts such as: ‘Don’t bring offerings since it creates tsunamis’;‘Making offerings to any other than Allah invites punishment’; ‘Just make this an activityfor tourists so that it will not incur Allah’s anger’; and ‘Sin will destroy you!’ (Muzaki2018a). Clearly, these activities sought to polarize the local population and so theyraised concerns among the members of the local FKUB, which had in fact already designedproactive strategies to defuse potentially divisive FUI activities.

Depending on the location, the FKUB can play an important role in mediating anddeflating local interreligious conflicts and disputes. FKUB forums were established in2006 by the Minister of Religious Affairs and the Minister of Internal Affairs with thegoal ‘to protect and enhance harmony and to avoid one-sided religious actions’ (Indonesia2006). A number of FKUB branches were established across Indonesia at the provincial,county, and local levels. The Minister of Religion regarded the FKUB as among ‘ourbest achievements’ in the efforts to promote religious harmony across the country. Inaddition, the FKUB initiative symbolized a turning point in the governmental approachas it truly represented a grassroots movement in which ‘top-down became bottom-up’(Ali and Indonesia 2011). The Cilacap forum started in January 2007. Its members rep-resent the local branches of national religious organizations such as the MUI (MajelisUlama Indonesia; the Council of Indonesian Ulama), and the PGI (Persekutuan Gereja-gereja di Indonesia; the Indonesian Council of Churches, which represents mainline Pro-testant churches). Forum members also represent Catholics, Hindus, Buddhists, andConfucians.

As incidents in Cilacap increased, the Forum called for opportunities to educate thepolice and the army about the dangers radical groups pose since they ‘have the potentialto undermine Pancasila and the Republic of Indonesia’ (Muzaki 2018b). In order to create

4 M. HIDAYATI AND N. VAN DOORN HARDER

a better understanding of the dangers involved, the Forum had already focused on devel-oping several programmes to teach the public about radical Islam and issued public state-ments calling for strengthening harmonious ties between the various religious groups.These efforts were not just interreligious, however, but in large part concerned relationsbetween radical and non-radical Muslims. Among other concerns, Forum membersfound that, in several high schools, teachers affiliated with radical Muslim groups wereactively trying to convince students of the need to create an Indonesian Islamic state.As a result, the Forum created a de-radicalization programme aimed at the high schoollevel (Muzaki 2017b).

From a historical point of view, the emphasis of the Cilacap FKUB forum on radicalismis not without a reason. Cilacap has a long history of dealing with radical groups, Islamic aswell as Communist, as noted above. It was in this social and historical context that therelatively small FUI group tried to rally the masses and create interreligious tensionsover the celebration of Christmas and New Year.

The billboard

Indonesians, both Muslims and non-Muslims alike, immediately understood the under-lying context of the billboard. Its message underscored that Muslims should ignore theconventional Gregorian or Christian way of calculating the years and instead refer totheir own lunar calendar. It also symbolized the ongoing efforts of groups such as theFUI, which aim to re-engineer the country from a pluralist nation into one governed byIslamic law. Most of all, the billboard revealed the complex relationship betweenMuslims and Christians when it comes to the person of Jesus Christ. Although theQur’an frequently speaks about him and even dedicates a chapter to his mother, theVirgin Mary (Sura 19), in interactions between Muslims and Christians, each side holdson to their own firm beliefs about who he is and his role in God’s plans for the world.

As a side note, the billboard affair reminded us of the fact that, in spite of the highregard the Qur’an has for Jesus and his mother, he does not play a significant role inMuslim–Christian encounters. That is not just the case in Indonesia. For example, the pro-minent document ‘A Common Word between Us and You’, which seeks to find commonground between Islam and Christianity and was published in September 2007 by the RoyalAal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought in Jordan, does not mention Jesus. The docu-ment, signed by 138 prominent Muslim scholars and leaders focuses on the love ofGod and love of neighbour.3

When considering how religious and community leaders reacted to the billboardmessage, it is also important to mention the role the MUI played in this affair. TheMUI was established on 26 July 1975, and is a non-governmental institution that isnevertheless funded by the government (Ichwan 2005, 46). Under the Suhartoregime, the MUI fatwas were in line with government policies that aimed at maintain-ing a level of harmony between the various religions.4 However, after 1998, during theso-called Reformation Era, the fatwas that the MUI issued became less tolerant. At onepoint, the National Committee for Human Rights even issued a statement accusing theMUI of playing a direct role in creating attitudes of intolerance and hatred among Indo-nesian Muslims (Colbran 2010, 713).

ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM RELATIONS 5

Moreover, in areas of Indonesia that have interreligious families, Muslims celebratingChristmas was always a sore point and, as early as 1981, the MUI issued a fatwa forbiddingit. Furthermore, in 2005, the MUI issued a series of fatwas that seemed aimed at destroyingIndonesia’s pluralist character. They included a fatwa forbidding interreligious marriage(although Islamic law allows a Muslim man to marry a woman of the Christian orJewish faith), a fatwa against Muslims and non-Muslims praying together (for example,at a funeral of someone whose family included both Muslims and non-Muslims), and afatwa ‘against pluralism’ (Ahmad 2015, 171–172). This last fatwa states that pluralismis prohibited since it believes all religions are the same. President Susilo Bambang Yud-hoyono (2004–2014) supported the fatwa, although several prominent Muslim scholarsobjected to it, arguing that it contradicted the spirit of the country’s foundation of Panca-sila, which declares Indonesia to be a multi-religious country.5 The chair of the largeMuslim organization Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) considered the fatwa a step backwards forIndonesian religious life (Mulia 2011).

On the intra-Islamic level, in 2005, the MUI issued an influential fatwa condemning theAhmadiyyah branch of Islam, which opened the door to acts of extreme violence againstAhmadi Muslims. In 2007, the MUI refined its position about ‘deviant beliefs’ by issuingten rules by which to identify ‘deviant sects’. At that time, the government took the sameposition as the MUI and President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono even stressed that his gov-ernment would fight these sects (Colbran 2010, 713).

Clearly, 2005 was a bad year for Indonesia’s pluralist society and the MUI fatwas hadsomething to do with it (Magnis-Suseno 2010, 347–348). The MUI seemed to put asidesociological considerations in its understanding of the concept of pluralism, ignoringthe historical approach that considers Indonesia to be a pluralist state (Anwar 2011;453–454). The MUI fatwas influenced public perceptions and opened the door forgroups such as the FUI to push the agenda further with their billboard. Without theMUI decisions, the issue might never have come to the fore.

The billboard received various responses and protests from religious communities.Darwis Manurung, the chair of the Indonesian Council of Churches in Indonesia (Perse-kutuan Gereja-Gereja di Indonesia; PGI) issued the following statement.

Don’t ever try to handle, interfere in, let alone blame the beliefs of those who follow differentreligions,

Why should talking about faith, be on a billboard display?

Faith is not something to put on display. Christians should not need to worry, let alone beprovoked.6 (Gultom 2018)

This was a very clear and direct reaction, conveying the message that FUI followers shouldkeep their hands off foundational Christian principles of faith and not try to create inter-religious strife. Indirectly, the PGI chair also referred to the fact that Indonesia is a reli-giously pluralistic country where Muslims are the majority (87.18%), with Protestants(6.96%), (Catholics 2.91%), (Hindus 1.69%), Buddhists (0.72%), and Confucians(0.05%) making up the rest of the population (Badan Pusat Statistik 2010). All are includedin the Indonesian Constitution, which upholds the foundational philosophy of Pancasilaand considers the various religious groups to be united in belief in one God. WhileMuslims form a large majority in the nation as a whole, Christians form the majority

6 M. HIDAYATI AND N. VAN DOORN HARDER

in several provinces in Indonesia, such as Papua, Nusa Tenggara Timur, and North Sula-wesi, while the majority in Bali is Hindu. Some cities, such as Yogyakarta, also have largeChristian communities. Since the fall of President Suharto, the influence of radical-mindedMuslim groups who aim to abolish the Pancasila principle has increased and created ten-sions and conflicts between Muslims and non-Muslims.

Within this complex and ever-moving landscape, the FUI has become the main leaderof radical Islam (Hasani and Naipospos 2010). The organization was started by activists inthe Indonesian Council for the Propagation of Islam (Dewan Dakwah Islamiyah Indone-sia), who were supported by Hizbut Tahrir leaders such as KH. Cholil Badowi, KH. KholilRidwan, Mashadi, and Muhammad Al Khaththath. They felt compelled to create a neworganization, the FUI, after hearing rumours of American soldiers committing acts ofblasphemy when interrogating al-Qaeda members detained in Guantanamo.

On 23 May 2005, the FUI held its first public event and rallied thousands of people toprotest against the alleged acts of blasphemy at Guantanamo (Hasani and Naipospos2010). During the following years, the FUI opened 15 branches in various provinces,where they orchestrated several public actions, often jumping on topics that divide Indo-nesian public opinion. For example, on 20 April 2008, the FUI organized a demonstrationof around 100,000 people demanding the abolition of the Ahmadiyyah branch of Islam.They have also lobbied for the refusal of permits to non-Muslims to build places ofworship or to use public facilities for religious activities (Bagir et al. 2011). The FUI hasshown itself to be very adept at effective lobbying. For example, in 2005, they persuadedthe MUI to issue a fatwa forbidding the so-called ‘Liberal Islam’ group from providingcounter-arguments to the growing radical discourses. In 2017, they also managed toorganize mass demonstrations against the highly regarded governor of Jakarta, BasukiTjahaja Purnama, who was accused of breaking the Indonesian laws on blasphemy. Asa result, he had to step down as governor and spent two years in prison.

Jesus/Isa in Christianity and Islam

Before we continue our discussion on the reactions to the billboard, we need to address thequestion of why mentioning Jesus in the context of Muslim–Christian engagement is socontroversial. Why would the FUI come up with the provocative statement that Jesus isMuslim? Why did they not just post a warning that Muslims should not engage innon-Muslim celebrations such as Christmas and New Year? After all, more than adecade earlier, MUI fatwas had cleared the way for such advice so it would not havebeen that controversial.

The reality is that the figure of Jesus can serve as a bridge as well as a barrier betweenChristian and Muslim communities (Ayoub 1995, 65) and can be a controversial,complex, and troubling topic, ‘touching issues that are at the very heart of the respectivefaiths’ (Bryant 1998, 171). Over thirteen centuries of Christian–Muslim relations, the issueof Jesus/Isa has been burdened by polemical ‘you are wrong’ and apologetic ‘I am right’arguments (162). Interreligious understanding and interpretation of Jesus’s birth, life,and crucifixion can lead to firm truth claims being made by both sides. Encounteringexpressions and beliefs that we cannot fully comprehend confronts us with the limits ofour individual understanding. Furthermore, we realize that, in order to accept or atleast understand the other side’s position, we might need to change our entire cultural

ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM RELATIONS 7

and religious frame of reference. The text on the billboard provides a perfect example ofthis reality.

The primary sources for descriptions of Jesus in this context, the Bible and the Qur’an,provide overlapping stories as well as conflicting images. Different beliefs about Jesus’sdivine nature, status as the Son of God, and the crucifixion remain the most contentious.According to Sachiko Murata and William Chittick (1995, 179), Christian–Muslimrelations are coloured by the preconception that ‘Muslims see other religions in termsof Islam, which in their eyes is the perfect religion. Of course, followers of other religionsalso look at the issue from their own perspective; this is not a quality unique to Muslims.The reality is that Muslims will see Jesus in terms of Islam, and Christians will view Jesusin terms of Christianity. In this context, M. Darrol Bryant (1998, 170) raises a crucial ques-tion: ‘Can we see the understanding of Jesus that emerges in the sacred scripture of the twotraditions in the other’s terms?’

Scholars have recently taken up this question in various ways. Zeki Saritoprak in Islam’sJesus argues that we find most commonalities in the eschatological role of Jesus. Muslimsbelieve that, during the time the anti-Christ reigns on earth, he will greatly oppressMuslims until Jesus descends to rescue them (Saritoprak 2014, 73–74). The Qur’andoes not provide much information about how and when Jesus will return and most ofwhat Muslims believe about that time comes from the Tradition of the Prophet, theHadith. In Scriptural Polemics: The Qur’ān and Other Religions, Mun’im Sirry (2014)examines several reformist Muslim interpretations of the difficult passages in theQur’an that hinder interfaith relations, with core topics such as the issues of Jesus asGod’s son, his divine nature, and the Trinity, showing that the issue is much morecomplex than meets the eye. Sirry, who found a wide range of opinions among the sixinterpreters whose work he examined, concludes that there is not one firm and fixedMuslim opinion about these topics.

Generally speaking,Muslims view Jesus as one of God’s prophets but reject the concept ofHis divinity, which is a difficult notion to explain, even for Christians. Many Christians whohave not reflected deeply on the teachings about Jesus’s divinity have trouble explaining it.

The Trinity is an equally difficult topic and unacceptable to Muslims. The Qur’an isvery clear about the fact that God is one. Q 112 clearly rejects the idea of the Trinity:‘Say: He is God, Unique, God, Lord Supreme! Neither begetting nor begotten, and nonecan be His peer.’7 Complicating the concept of the Trinity is the fact that, at the timeof the Prophet Muhammad (PBH), the Arabs believed that the Virgin Mary was thethird member of the Trinity (Watt 1991, 23). Hence, when hearing the term ‘Son ofGod’, they imagined a small nuclear family in the human sense. Furthermore, it remindedthem of the pre-Islamic concept that Allah had three daughters. Naturally, both interpret-ations would deny that God is one.

According to Christian teaching, however, the Trinity reflects God’s economy andexplains how God acts in relation to the world. According to Catherine MowryLaCugna (1993, 377): ‘The economy is not an abstract idea, nor a theological principle,but the life of God and creature existing together as one.’

While the Bible and the Qur’an present a similar record of events in the life of Jesus,such as his miraculous birth and certain miracles, they have conflicting ideas aboutwho Jesus was. Unlike the Qur’an, the Bible presents the story of Jesus/Isa in chronologicalorder. In the Qur’an, we see that there is no tendency to describe the chronological

8 M. HIDAYATI AND N. VAN DOORN HARDER

timeline of Jesus/Isa’s life since the Qur’an’s goal is to clarify what it considers to be wrongimages of Jesus. According to Tarif Khalidi (2001, 17):

The Qur’anic Jesus is in fact an argument addressed to his more wayward followers, intendedto convince the sincere and frighten the unrepentant. As such, he has little in common withthe Jesus of the Gospels, canonical or apocryphal. Rather, the Qur’anic image bears its ownspecial and corrective message, pruning, rectifying and rearranging an earlier revelationregarded as notorious for its divisive and contentious sects. The Qur’anic Jesus issues, nodoubt, from the ‘orthodox’ and canonical as well as the ‘unorthodox’ and apocryphal Chris-tian tradition. Thereafter, however, he assumes a life and function of his own, as oftenhappens when one religious tradition emanates from another.

The different images of Jesus in the Bible and the Qur’an lead both Christians andMuslimsto develop their own interpretations. Ibn Taymiyya (1984, 74), the thirteenth-centurytheologian whose work is popular among radical-minded groups today, believed thatChristians had corrupted the true prophetic religion. According to him, the Qur’anstates that God sent His prophets including Jesus, but Christians corrupted their text bysaying Jesus is more than just a human prophet. People who support this view believethat ‘The true followers of all these prophets have always been and will always be“Muslims”’ (Khalidi 2001, 14). To Ibn Taymiyya (1984, 102), early Christians and Jewsfollowed something but later they had nothing left to follow. Since, according to hisinterpretation, the Gospel was corrupted, it was in his view a human product, reducedto the level of Hadith in Islam (114). The Hadiths convey the Prophet Muhammad’swords and attitudes as reported by the Companions and were collected long after thedeath of the Prophet. In such a context, corruption is inevitable, so not all the Hadithstories can be true and valid, and some could have been fabricated.

According to ʿAta Ur-Rahman (1996, 196), the apostle Paul started this scriptural cor-ruption by creating doctrines on redemption, original sin, and the Trinity. He calls Paul’sideas ‘mathematically absurd, historically false, yet psychologically impressive’ (71–72).Furthermore, Ur-Rahman states, ‘the physical aspect of what Jesus actually brought, hiscode of behavior, is today irrecoverably lost and Christians have been left without anydefinite guidance on how to live their daily lives’ (199–200).

In line with this idea, others argue that there is nothing to learn from the Christian Jesuswhen compared to Muhammad (Zebiri 1997, 63), and the Indian writer K. Niazi believesthat Islam is the true religion of Jesus.Muslims can see that the fundamental tenets of Jesusclosely correspond to the basic beliefs of Islam (quoted in Zebiri 1997, 63). Muslims willnot have difficulty in accepting this because, for them, Jesus actually introduced Islam,since he urged his followers to worship the One and only God, and had no intention ofestablishing a church or leaving behind a community that would worship him (DharmarajE and Dharmaraj S 1998, 146). According to Mahmoud Ayoub (1976, 167):

We see Jesus in Islam, as in the Gospel, as the messenger of forgiveness and love… thepoverty, authority and detachment from this world of the Christ of the Gospel receives, inIslamic piety, a far greater emphasis. Hence, Jesus becomes the example of piety, renunciationof worldly pleasures, and poverty… the one after whom they (the Muslims) sought to patterntheir lives and conduct.

In addition, according to the Qur’an, Christians deserve a level of respect as they areamong the People of the Book:

ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM RELATIONS 9

Those who believe in the Qur’an and those who follow the Jewish (scripture) and the Chris-tians and the Sabians, any who believe in God and the last day and work righteousness shallhave the reward with their Lord, on them shall be no fear nor shall they grieve. (Q 2.62)

According to this verse, the requirement for being saved is to believe in God and the lastday and to do good deeds. In this context, Muhib Opeloye (1998, 183) writes:

This is the belief in and submission to one God without attributing to Him any associate, asenjoined in Deuteronomy 6:4 (cf. Exodus 20:3), Mark 12:29 and surah 112:1–4. The issue ofright belief is not irrelevant because even within each tradition there are groupings.…Natu-rally, each of these groups would see itself as having the right belief. Whoever falls into wrongbelief, whether he be Muslim or Christian, would be denied salvation.

In summary, Christians believe God to be in Christ, and Christ in God. This accountsfor Jesus’s divine spirit. Muslims deny the crucifixion and do not consider Jesus to be asaviour but only a human messenger sent by God. These truth claims are certainly areuncomfortable for both sides and in many cases complicate Christian–Muslim relations.According to Khalidi (2001, 7–8), ‘some writers argue that the Christian concept ofredemption is absent from the Jesus of the Qur’an and that therefore a genuine andtotal reconciliation between Islam and Christianity is at best problematic’. In addition,as the billboard affair shows, the present-day disagreement between Muslims and Chris-tians is not simply about ‘the nature of God as One and living and self-subsistent’ (Wil-liams 2006, 177). It is about who can claim Jesus as a prophet. Furthermore, someMuslim leaders believe that Christians corrupted the Bible to the point where it hasbecome irrelevant. For those who hold that view, claiming Jesus as a Muslim prophetis not such a great leap.

Responses to the billboard

With some of these traditional Muslim and qur’anic views of Jesus in mind, it is of interestto see what a selected group of Indonesian Muslim leaders had to say about the ‘Jesus isMuslim’ message. Taufik Hidayatulloh, the chair of the Institute for Islamic Studies Rah-matan lil Alamin in Cilacap and a member of the FKUB forum that promotes religiousharmony, considered it a religious truth claim. However, in his view, this type of claimshould not be on public display since it could lead to intolerance and hatred and is alsohurtful to the Christian community. For that reason, he asked the district head ofCilacap to remove the billboard immediately or his group would bring a lawsuit foralleged blasphemy and breach of religious freedom (Publica 2018; Gatra 2018; Rachelea2018). After contacting the head of the Cilacap police, he organized a discussion withthe FUI group and also invited other members of FKUB Cilacap to address the matterin order to avoid polarization within society (Gatra 2018).

Masduki Baidowi, national chair of the Information and Communication Division ofthe MUI issued a statement that the FUI should not ‘create an atmosphere that givescause for misunderstandings. It is better to create a peaceful atmosphere so that Christianscan worship in peace’. According to him, Muslims know about the position of Jesus inIslam and they should strive for a united Indonesia where one group does not feel superiorto the other (Rachelea 2018). Meanwhile, Rumadi Ahmad, chair of the NU-related Insti-tute for Study and Development of Human Resources (Lembaga Kajian dan

10 M. HIDAYATI AND N. VAN DOORN HARDER

Pengembangan Sumber Daya Manusia; Lakpesdam), emphasized that the billboard waspointless (Nathaniel 2018).

Reacting to these high-level responses, FUI chair, Syamsuddin, argued that the bill-board was not provocative and nor could it give rise to blasphemy since it was addressingMuslims only. It was to warn Muslims lest they felt tempted to attend Christmas events,especially if Christian songs would be sung. He also denied that the FUI was an intolerantgroup since they never forbade religious celebrations and were committed to protectingfollowers of all religions. Mindful that his organization could be the cause of intra-Muslim strife as well, Syamsuddin agreed to meet with those who were against the bill-board (Gatra 2018; Tribunnews 2018).

With these reactions in mind, we interviewed several Muslim and Christian leaders inYogyakarta to ask their opinion about the billboards and about Jesus in Islam, and if theyhad any thoughts about the benefits or drawbacks of discussing Jesus in interfaith dialogueevents.

Amin Abdullah, professor of philosophy at the Islamic State University in Yogyakartaand a high profile member of the second largest Indonesian Muslim organization,Muhammadiyah, thought that, within the Indonesian context, due to the ongoingdebates about the increasing intensity of Muslim and Christian religiosity in thecountry, it would be better to leave Jesus out of the interfaith dialogue. According toAbdullah, discussing the figure of Jesus prevented the establishment of permanent goodrelationships and that was the main reason why most FKUB forums avoided the topic.Instead, they focused on social issues such as how to address poverty and to upholdjustice. Followers of all religions can agree on such matters (Abdullah 2019).

In line with Abdullah, the Muslim intellectual Munir Mulkhan said that the issue ofJesus should not be part of the dialogue between Christians and Muslims. Both he andAbdullah thought that Indonesia’s Muslims were still traumatized by the Catholic andProtestant missionary efforts of the Dutch colonizers and he advised postponing speakingabout Jesus and first focusing on creating mutual trust between Muslims and Christians(Mulkhan 2019).

Not all Muslim leaders were of the same opinion. NU leader KH Nurhafidz, who headsthe Qur’an school Tarbiyatul Qur’an Buayan, in Gombong Kebumen, was against avoid-ing the topic of Jesus in Christianity and Islam (Nurhafidz 2019). In his view, the Ministryof Religious Affairs and the FKUB forums should encourage exploring the ideas membersof the respective religions have about Jesus since it would facilitate the growth of under-standing and possibly lead to shared points of view. NU leader Hasan Masykur Al Aziz,who heads the Qur’an school Fathul Ulum, Kuwarasan, in Gombong Kebumen, agreedwith the idea that the state via the Ministry of Religion, as well as the FKUB, shouldplay a bridging role (Al Azis 2019). He stressed that differences are normal and areeven part of God’s plan. Therefore, people should be invited to explain their points ofview in order to create a peaceful Indonesia.

While the opinions of Masykur and Nurhafidz, seem on the surface to be leaningtowards opening a true dialogue about the place of Jesus within Christianity and Islam,they also suggested leaving the entire New Testament out of such encounters. Accordingto them, ‘Interfaith dialogue can only be fruitful when based on the Old Testament. Intro-ducing the New Testament will yield no points of connection. The Qur’an urges Muslimsto invite People of the Book to deliberate differences and to respect them’ (Nurhafidz

ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM RELATIONS 11

2019). Moreover, Nurhafidz added that it would be better for the nation to focus onstrengthening harmonious relations between all of the religions, not just between Islamand Christianity.

Christian leaders whose opinion we asked about the issue placed the figure of Jesuswithin the larger framework of Indonesian interfaith engagement in general. Forexample, Professors Giyana Banawiratma, who teaches Theology at the Protestant DutaWacana University in Yogyakarta, and Gregorius Budi Subanar, who teaches ReligiousStudies at the Catholic Sanata Dharma University in Yogyakarta, stressed the realitythat we need to discern several levels of interfaith dialogue (Banawiratma 2020,Subanar 2020). For example, people engage with each other in the workplace or as neigh-bours, while a theological engagement would be on a different level altogether, and not alllevels are equally successful. Subanar also pointed out that within one religion we find alarge spectrum of opinions.

According to Banawiratma, it is important to know why the government interveneswhen certain incidents occur between religious groups. Is it to strengthen or to exploitcommunal relationships? Does it want to mediate between groups even when the localcommunity would have more experience in handling the situation? How does the bureau-cratic apparatus understand local interfaith engagements? In his opinion, for interfaithdialogue to be strong, it must come up from the grassroots level. If that were the case,‘the government could, for example, fund a research project about Jesus in the Qur’anand the Gospel, whether or not it came from the FKUB forums’ (Banawiratma 2020).

Baskara T. Wardaya, a Jesuit priest, acknowledged that there is a dire need for Muslim–Christian dialogue. However, we need to remember that religious convictions are very per-sonal (and are often abused to serve certain political goals). We should not be in a hurry,and should first discuss things on a limited scale, starting, for example, with discussionswithin academic circles. When that works out, we can reach for the next level(Wardaya 2020).

Ongoing efforts to strengthen interfaith relations in Indonesia

The billboard message that ‘Jesus is Muslim’ seems to fit within the context of currentchanges in Indonesian society, where radical-minded groups are aiming to polarize thepopulation and break with the Pancasila principle. As a result, most of the responses tothe ‘Jesus is Muslim’ statement do not touch on the difficult theological issues but aim tomaintain harmonious relations between Muslims and Christians. Therefore, most of thevarious reactions wish to uphold the Pancasila principle and to protect the Indonesian state.

The Christian reactions are careful, pointing out that faith is a personal issue and thatthere are doors in interfaith engagement that are better left closed. When considering themany levels of interfaith dialogue, it seems to be safe to stay at the level of carrying outacademic research about Jesus. Christians are not just a religious minority. As ProfessorAmin Abdullah and Muslim leader Munir Mulkhan pointed out, Muslim–Christianrelations in Indonesia carry the burden of the colonial heritage and evoke Dutch colonialpower, which brought in its wake Christian missionary activities. Such memories are stillalive in the background and groups such as the FUI are ever alert to possible Christianmissionary influences. After all, the Pancasila principle allows Indonesian Muslims toconvert to another religion.

12 M. HIDAYATI AND N. VAN DOORN HARDER

Much more research is needed to find out what the majority of Indonesian Muslimsthink about this issue. Does avoiding difficult topics in relation to Jesus really lead tomore peaceful religious coexistence? There are voices such as those of Qur’an schoolleaders KH Nurhafidz and Hasan Masykur Al Aziz that seem to support a deeper levelof engagement and stress that religious differences are part of God’s plan. They arguethat the state should play a more pro-active role in discussing teachings about Jesus inMuslim–Christian dialogue. However, they also propose leaving the entire New Testamentout of the discussion since, following ideas of scholars such as Ibn Taymiyya and Ur-Rahman, they consider that the Gospel is a corrupted tradition and has nothing to offer.

These contrasting opinions not only show the range of views held by Muslim leadersabout the figure of Jesus, but also point to the fact that discussions tend to be limited tothe Bible and the Qur’an. Materials such as poetry, mystical discourses, and otherdeeply personal faith experiences remain excluded. Shahab Ahmed’s What is Islam?The Importance of Being Islamic touches on the problem of relying on limited bodies ofwork during interfaith encounters. In the Islamic context, Ahmed’s main critique isthat ‘Both Muslim and non-Muslim moderns tend to marginalize the complex modesin which Muslims conceptualized their faith’ (Ahmed 2016, 82–83). To Ahmed, gettingto the heart of the complex religious system called Islam includes taking a closer lookat how believers process and live the holy message by way of philosophy, mystical prac-tices, poetry, and art. Just using the main body of sacred texts of the Qur’an and Tradition(Hadith) does not suffice (82–83).

The reality remains that our knowledge of our respective religions is limited. Where itconcerns Islamic ideas about Christianity, Montgomery Watt, a British scholar of Islam,located this problem within the earliest days of Islam. According to his analysis, weknow virtually nothing about the Christians who were in contact with the ProphetMuhammad. While the qur’anic perception of their views might be correct, it remains‘an inadequate perception of the Christianity of the Byzantine Empire and other lands sur-rounding Arabia at the time of the Prophet Muhammad’ (Watt 1991, 25–26). Thereremains much to be learned about each other’s faith.

Conclusion

As our limited research results show, within the Indonesian context, the billboard affairreveals that religious leaders, both Muslim and Christian, opt to stay on the safe side con-cerning introducing issues within interreligious engagements that could lead to furtherpolarization. If nothing else, the strategies developed by the FKUB forum in Cilacapshow that they follow the primary goal of preventing communal violence, not justbetween followers of different religions, but also between Muslim groups and sects. Pre-venting future violence in itself is, of course, an excellent reason to engage in interfaithengagement.

However, when groups such as the FUI try to push the envelope, they expose signs ofthe reality that entertaining difficult topics within the religiously pluralistic landscapecould mean opening a Pandora’s Box. Alternatively, it could lead to closer and strongerrelationships, in this case between Muslims and Christians.

Especially after the early 2000s, when Indonesia witnessed episodes of inter- and intra-religious strife, the overarching goal of the religious and governmental establishment has

ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM RELATIONS 13

been to strive for reconciliation and to maintain peace. This reality could easily lead to theconclusion that, with its laser focus on maintaining a fragile balance in intercommunaland interreligious relationships, the officially orchestrated dialogue between the religionsprovides a safe, albeit stagnant, space in which to address problems and differences. Thequestion is whether the FKUB and similar approaches create a solid foundation to with-stand sectarian strife when it strikes.

Studies on interreligious dialogue have pointed to its ‘viability’ and ‘efficacy’ (Haddadand Fischbach 2015), but they argue that it is not an easy way out and cannot providequick solutions to complicated situations between followers of different religions. It ishard work and an ongoing challenge. FKUB members and other religious leaders pointto the importance of their activities for the prevention of future atrocities. However,they prefer to keep their intervention to the minimum and most necessary level. Scholarssuch as Peter Admirand argue that such strategies will not help create and sustain stronginterreligious models and groups that will last when new threats occur:

Interfaith dialogue is no elixir or panacea but a key component of atrocity prevention. Atro-cities are constructed and unleashed around the demonization and hatred of the Other,often employing ethno-religious language and justification. Mass-atrocity prevention beginswith the conceptions of ourselves and the Other – and interfaith dialogue is a crucial pieceto inform and direct these conceptions. Coupled with a deeper sense of humility, interfaith dia-logue helps us to recognize our need for, and interdependence in, one another. Taken seriously,such dialogue commitment and practice could revolutionize economic,military, judicial, legal,and foreign policy, demanding foundational historical reassessments and critical and ongoingself-evaluation and judgements… , it will strengthen our role in creating and sustaining suchgroups when context and timing supposedly demand it. (Admirand 2016, 284)

Representing the government at the grassroots level, the FKUB has developed a strategyof not intervening in the theological teachings of other religions, but only managingthe life of Indonesian citizens. A 2008 Joint Ministerial Decree (Surat KeputusanBersama) emphasized this point. According to the minister of religious affairs, theFKUB should not be ‘a form of Government intervention into society’s beliefs’ (Indonesia2008).

When this strategy of minimum intervention prevails, the minority Christian commu-nity suffers. While our interviews show that several of the Christian leaders stress theimportance of applying a multi-tiered model of interfaith engagement, they are notreally eager to engage in the topic, and Muslim leaders are not interested in a deeper inter-action about the role of Jesus in both religions either.

In short, the billboard affair did not only expose conflicting truth claims, but alsouncovered the fact that historical, theological, and political realities should be takeninto account where it is a matter of strengthening harmonious relations betweendifferent religious communities. While the strategy of playing it safe is understandable,the billboard revealed that deeper forms of dialogue using various approaches couldhave yielded great future benefits. Entertaining a deep investigation about what eachside really believes could have strengthened interreligious cooperation for when suchissues re-emerge. For example, FKUB Cilacap could have benefited from invitingMuslim and Christian theologians to address the place of Jesus in Islam and Christianity.If nothing else, including theological discussions and dialogues on historical politicalissues about Muslim–Christian encounters in Indonesia could yield deeper forms of

14 M. HIDAYATI AND N. VAN DOORN HARDER

engagement between the religious communities. When considering the ‘viability’ and‘efficacy’ of interreligious engagement, research has shown that the deeper the engage-ment, the more viable the forms of coexistence that emerge.

However, a deeper approach requires the concerted and long-term effort of all theparties involved. This reality perhaps shows the main weakness of the FKUB and othersimilar models. Having other day jobs, the members do not have the time and energyto pursue forms of dialogue that operate at a deeper level than managing communityrelationships. In their model, there is no room for deep study of each other’s religious con-victions. In actuality, this model also operates outside the core grassroots level whereordinary people, neighbours, friends, and colleagues do create viable and robust initiativesthat yield respect for each other’s position and that can withstand episodes of provocationand interreligious strife. In other words, a large gap remains between the governmentalFKUB approach and the reality of Indonesia as a large pluralist society.

Notes

1. For a longer discussion of this topic, see, among others, Sirry (2014, 133–166).2. Discussing these various levels and approaches would go beyond the scope of this article. For

example, Husein (2005) argues that we first need to distinguish between Muslims who havean inclusive attitude concerning adherents of other religions and those who have an exclusiveattitude, while King (2008) argues that we need to consider dialogue on the spiritual level, andMoyaert (2018) proposes to investigate cases of inter-rituality. See also Eck (2007); Cornille(2008); Patel, Peace, and Silverman (2018).

3. See ‘A Common Word’. Accessed 14 May 2020. https://www.acommonword.com/introduction-to-a-common-word-between-us-and-you/.

4. A fatwa is an opinion on a specific topic within Islamic law given by an acknowledged expert.A fatwa is not binding but devout Muslims in Indonesia tend to take MUI fatwas seriously(Kapten 2018; Laffan 2005).

5. Some of the scholars who disagreed with the fatwa were: Abdurrahman Wahid, DjohanEffendi, Musdah Mulia, Dawam Rahardjo, Syafi’i Anwar, and Weinata Sairin.

6. Translated by Mega Hidayati.7. Translations of the Qur’an are taken from Khalidi (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Contending Modernities team at the University of Notre Dame for their support forour work. We especially owe thanks to Dr Mun’im Sirry, who is in charge of the Indonesia project.The materials for this article were gathered during our membership of the Indonesia ContendingModernities project (2016–2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

This work was supported by Contending Modernities at the University of Notre Dame [grantnumber 383128WFU].

ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM RELATIONS 15

ORCID

Mega Hidayati http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8591-9395Nelly van Doorn Harder http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3242-6220

References

Abdullah, Amin. 2019. “Interview in July 28.” Yogyakarta.Admirand, Peter. 2016. “Dialogue in the Face of a Gun? Interfaith Dialogue and Limiting Mass

Atrocities.” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal 99 (3): 267–290.Ahmad, Rumadi. 2015. Fatwa Hubungan Antaragama di Indonesia. Jakarta: Gramedia.Ahmed, Shahab. 2016. What Is Islam? The Importance of Being Islamic. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.Al Azis, Hasan Mansyur. 2019. “Interview in July 30.” Kebumen.Ali, Suryadharma., and Departemen Agama Indonesia. 2011. Himpunan Pidato Tahun 2011/

Menteri Agama RI. Jakarta: Pusat Informasi dan Hubungan Masyarakat Kementerian Agama.Anwar, M. Syafi’i. 2011. “Ketika Pluralisme Diharamkan dan Kebebasan Berkeyakinan Dicederai

(Sebuah Kaleidoskop, Pengalaman, dan Kesaksian untuk Mas Djohan Effendi).” InMerayakan Kebebasan Beragama: Bunga Rampai Menyambut 70 Tahun Djohan Effendi,edited by Elza Peldi Taher, 424–466. Jakarta: Democracy Project: Yayasan Abad Demokrasi.

Ayoub, Mahmoud M. 1976. “Towards an Islamic Christology: An Image of Jesus in early Shi?’?Muslim Literature.” The Muslim World 46 (3): 163–188. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1976.tb03198.x.

Ayoub, Mahmoud M. 1995. “Jesus the Son of God: A Study of the Terms Ibn and Walad in theQur’an and Tafsir Tradition.” In Christian-Muslim Encounter, Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad andWadi Zaidan Haddad, 65–81. Gainesville: The University Press of Florida.

Badan Pusat Statistik. 2010. “Penduduk Menurut Wilayah dan Agama yang Dianut.” http://sp2010.bps.go.id/index.php/site/tabel?tid=321&wid=0.

Bagir, Zainal Abidin, Suhadi Cholil, Endy Saputro, Budi Asyhari, and Mustaghfiroh Rahayu. 2011.“Laporan Kehidupan Beragama di Indonesia 2010.” Yogyakarta. https://crcs.ugm.ac.id/download/laporan-tahunan-kehidupan-beragama-di-indonesia-2010/?wpdmdl=2251&refresh=5ecbf075538161590423669%0D.

Boland, B. J. 1982. The Struggle of Islam in Modern Indonesia. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.Banawiratma, J. B. 2020. “Interview in April 23.” YogyakartaBryant, M. Darrol. 1998. “Can There Be Muslim-Christian Dialogue Concerning Jesus/Isa?” In

Muslim-Christian Dialogue: Promise and Problems, edited by M. Darrol Bryant, and S. A. Ali,161–175. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House.

Colbran, Nicole. 2010. “Kebebasan Beragama atau berkeyakinan di Indonesia: Jaminan secaraNormatif dan Pelaksanaannya Dalam Kehidupan Berbangsa dan bernegara.” In Beragamaatau Berkeyakinan: Seberapa jauh?, edited by Tore Lindholm, W. Cole Durham, Bahia Jr, andG. Tahzib Lie, 681–735. Yogyakarta: Kanisius.

Cornille, Catharine. 2008. The Im-Possibility of Interreligious Dialogue. New York: Cross Road.Dharmaraj, Glory E., and Jacob S. Dharmaraj. 1998. Christianity and Islam: A Missiological

Encouter. Dehli: ISPCK.Eck, Diana L. 2007. “Prospects for Pluralism: Voice and Vision in the Study of Religion.” Journal of

the American Academy of Religion 75 (4): 743–776.Gatra. 2018. “Baliho ‘Jesus is Moslem’ Muncul di Cilacap, Pegiat Kerukunan Umat Beragama

Protes.” Gatra, Desember 27. https://www.gatra.com/detail/news/375716-Baliho-Jesus-is-Moslem-Muncul-di-Cilacap-Pegiat-Kerukunan-Umat-Beragama-Protes.

Gultom, Jones. 2018. “Soal Baliho ‘I Love Jesus, Jesus Is Moslem’, PGI: Umat Kristen JanganTerprovokasi.” Medanbisnisdaily.com. https://www.medanbisnisdaily.com/news/online/read/2018/12/28/61767/soal_baliho_i_love_jesus_jesus_is_moslem_pgi_umat_kristen_jangan_terprovokasi/.

16 M. HIDAYATI AND N. VAN DOORN HARDER

Haddad, Yvonne Yazbeck, and Rahel Fischbach. 2015. “Interfaith Dialogue in Lebanon: Between aPower Balancing Act and Theological Encounters.” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 26 (4):423–442. doi:10.1080/09596410.2015.1070468.

Hasani, Ismail and Naipospos, Bonar Tigor. 2010.Wajah Para Pembela Islam: Radikalisme Agamadan Implikasinya terhadap Jaminan Kebebasan Beragama/Berkeyakinan di Jabodetabek danJawa Barat. Jakarta: Pustaka Masyarakat Setara.

Husein, Fatimah. 2005. Muslim–Christian Relations in the New Order Indonesia: The Exclusivistand Inclusivist Muslims Perspective. Jakarta: Mizan.

Ibn Taymiyya, Ibn. 1984. A Muslim Theologian’s Response to Christianity: Ibn Taymiyya’s al-Jawabal Sahih, edited by S. J. Thomas F. Michel. New York: Caravan Books.

Ichwan, Moch Nur. 2005. “Ulama, State and Politics: Majelis Ulama Indoensia after Soeharto.”Islamic Law and Society 12 (1): 44–72.

Indonesia, Departemen Agama. 2008. Himpunan Pidato Menteri Agama RI Dr. H. MuhammadM. Basyuni Tahun 2008. Jakarta: Kementerian Agama RI. https://eperpus.kemenag.go.id/opac/detail/36023/Himpunan-Pidato-Menteri-Agama-RI-Dr.-H.-Muhammad-M.-Basyuni-Tahun-2008.

Indonesia, Kementerian Agama. 2006. Himpunan Pidato Menteri Agama RI H. Muhammad M.Basyuni 2006. Jakarta: Pusat informasi Keagamaan dan Kehumasan.

Kantor Kabupaten Cilacap, Kementerian Agama. 2016. “Data Jumlah Penduduk BerdasarkanAgama.” Cilacap. http://cilacap.kemenag.go.id/berita/read/data-jumlah-penduduk-berdasarkan-agama.

Kaptein, Nico J. G. 2018. “Fatwa in Indonesia: An Analysis of Dominant Legal Ideas and Modes ofThought of Fatwa-Making Agencies and Their Implications in the Post-New Order Period, byPradana Boy Zulian.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of theHumanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 174 (4). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill: 549–551. doi:10.1163/22134379-17404021

Khalidi, Tarif. 2001. The Muslim Jesus: Sayings and Stories in Islamic Literature. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

Khalidi, Tarif. 2008. The Qur’an: A New Translation. London: Penguin.King, Ursula. 2008. The Search for Spirituality: Our Global Quest for a Spiritual Life. New York:

BlueBridge.LaCugna, Catherine Mowry. 1993. God for Us: The Trinity and Christian Life. San Francisco, CA:

Harper.Laffan, Michael. 2005. “The Fatwā Debated? Shūrā in One Indonesian Context.” Islamic Law and

Society 12 (1). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill: 93–122. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568519053123920.Magnis-Suseno, Frans. 2010. “Pluralism under Debate: Indonesian Perspectives.” In Christianity in

Indonesia: Perspectives of Power, edited by Susanne Schroter, 347–360. Berlin: Lit Verlag.Moyaert, Marianne. 2018. “On the Role of Ritual in Interfaith Education.” Religious Education 113

(1): 49–60.Mulia, Siti Musdah. 2011. “Potret Kebebasan Beragama dan Berkeyakinan dalam Era Reformasi.”

In Merayakan Kebebasan Beragama: Bunga Rampai 70 Tahun Djohan Effendi, edited by ElzaAldi Taher, 335–364. Jakarta: Democracy Project. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1iodT-VEUFFfddCG-V9fE7QzMdU5fdE4Y/view.

Mulkhan, Abdul Munir. 2019. “Interview in July 28.” Yogyakarta.Murata, Sachiko, and William Chittick. 1995. The Vision of Islam. New York: Paragon.Muzaki, Khoirul. 2017a. “FKUB Cilacap : Jangan Terpancing Isi Selebaran di Lokasi Ledakan KUA

Sidareja.” TribunJateng, 5 July. https://jateng.tribunnews.com/2017/07/05/fkub-cilacap-jangan-terpancing-isi-selebaran-di-lokasi-ledakan-kua-sidareja.

Muzaki, Khoirul. 2017b. “Ada Spanduk Ajakan Dukung Khilafah, FKUB Cilacap Samakan denganMakar dan Lawan Konstitusi.” TribunJateng, 2 April. https://jateng.tribunnews.com/2017/04/02/ada-spanduk-ajakan-dukung-khilafah-fkub-cilacap-samakan-dengan-makar-dan-lawan-konstitusi.

Muzaki, Khoirul. 2018a. “Cilacap akan Punya Hajatan Sedekah Laut malah Muncul Banner Begini.”TribunJateng, 11 October. https://jateng.tribunnews.com/2018/10/11/cilacap-akan-punya-hajatan-sedekah-laut-malah-muncul-spanduk-begini?page=2.

ISLAM AND CHRISTIAN–MUSLIM RELATIONS 17

Muzaki, Khoirul. 2018b. “FUI Copot Banner terkait Sedekah Laut di Pantai Selatan Cilacap.”TribunJateng, 12 October. https://jateng.tribunnews.com/2018/10/12/fui-copot-banner-terkait-sedekah-laut-di-pantai-selatan-cilacap.

Nathaniel, Felix. 2018. “Ramai-Ramai Mengecam FUI Cilacap Atas Spanduk ‘Jesus is Moslem’.”Tirto.id. http://tirto.id/ramai-ramai-mengecam-fui-cilacap-atas-spanduk-jesus-is-moslem-dcMN.

Nurhafidz. 2019. “Interview in July 28.” Kebumen.Opeloye, Muhib O. 1998. “Jesus of Nazareth: A Scriptural Theme to Promote Muslim-Christian

Dialogue.” In Muslim-Christian Dialogue: Promise and Problems, edited by M. Darrol Bryant,and S. A. Ali, 177–186. St Paul, MN: Paragon House.

Patel, Eboo, Jennifer Howe Peace, and Noah J. Silverman. 2018. Interreligious/Interfaith Studies:Defining a Field. Part III. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Publica. 2018. “Baliho Jesus is Moeslim di Cilacap Diminta Dicopot.” PublicaNews. https://www.publica-news.com/berita/daerah/2018/12/27/25787/baliho-jesus-is-moeslim-di-cilacap-diminta-dicopot.html.

Rachelea, Sarah. 2018. “Soal Baliho ‘Jesus is Moslem’ di Cilacap, Menag Tanggapi Begini.”Suratkabar.id. https://www.suratkabar.id/118071/peristiwa/soal-baliho-jesus-moslem-di-cilacap-menag-tanggapi-begini.

Saritoprak, Zeki. 2014. Islam’s Jesus. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.Sirry, Mun’im. 2014. Scriptural Polemics: The Qur’ān and Other Religions. New York: Oxford

University Press.Subanar. 2020. “Interview in April 29.” Yogyakarta.Subarkah, Muhammad. 2017. “Kantor Urusan Agama Sidareja Cilacap Diserang Bom.”

Republica.co.id. https://www.republika.co.id/berita/nasional/hukum/17/07/05/oslkdy385-kantor-urusan-agama-sidareja-cilacap-diserang-bom.

Susanto, Ridlo. 2018. “Baliho ‘Jesus is Moslem’ Muncul di Cilacap, Pegiat Kerukunan UmatBeragama Protes.” Gatra. https://www.gatra.com/detail/news/375716-Baliho-Jesus-is-Moslem-Muncul-di-Cilacap-Pegiat-Kerukunan-Umat-Beragama-Protes.

Tribunnews. 2018. “Kontroversi Baliho bertuliskan I Love Jesus Because Jesus Is Moslem diCilacap.” TribunJateng. https://jateng.tribunnews.com/2018/12/28/kontroversi-baliho-bertuliskan-i-love-jesus-because-jesus-is-moslem-di-cilacap?page=3.

Ur-Rahman, ‘Ata. 1996. Jesus: the Prophet of Islam. Karachi: Begum Aisha Bawany Waqf.Wardaya, Baskara T. 2020. “interview in April 23.” Yogyakarta.Watt, William Montgomery. 1991. Muslim-Christian Encounters: Perceptions and Misperceptions.

London: Routledge.Williams, Rowan. 2006. “Christian and Muslims before the One God.” In Islam and Other Religions:

Pathways to Dialogue edited by Irfan Omar, 175–180. London: Routledge.Zebiri, Kate. 1997. Muslims and Christians: Face to Face. Oxford: Oneworld.

18 M. HIDAYATI AND N. VAN DOORN HARDER