Vegetation-environment relationships in a Negev Desert erosion cirque

Hunting and Gender as Reflected in the Central Negev Rock Art, Israel

-

Upload

antiquities -

Category

Documents

-

view

6 -

download

0

Transcript of Hunting and Gender as Reflected in the Central Negev Rock Art, Israel

This article was downloaded by: [George Nash]On: 10 September 2014, At: 13:49Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Time and Mind: The Journal ofArchaeology, Consciousness andCulturePublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rtam20

Hunting and Gender as Reflected in theCentral Negev Rock Art, IsraelDavida Eisenberg-Degena & George Nashb

a Department of Bible, Archaeology and Near East Studies, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Southern District, Israelb Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University ofBristolPublished online: 08 Sep 2014.

To cite this article: Davida Eisenberg-Degen & George Nash (2014): Hunting and Gender asReflected in the Central Negev Rock Art, Israel, Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology,Consciousness and Culture

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1751696X.2014.956009

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

Hunting and Gender as Reflectedin the Central Negev Rock Art,Israel

Davida Eisenberg-Degena and George Nashb*

aDepartment of Bible, Archaeology and Near East Studies,Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Southern District, Israel;bDepartment of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Bristol

(Received 9 July 2014; accepted 8 August 2014)

There are thousands of panels with hundreds of thousands of petro-glyphs that occupy the rock outcropping of the Negev Highlands insouthern Israel. These include abstract, zoomorphic and anthropo-morphic elements, which are sometimes presented as hunting scenes.In this paper we will define hunting scene, review the themes and relatethese figures to the economy, mundane, and spiritual realms of the artist.We argue that a clear panel grammar is in operation whereby the artistis creating a formulaic narrative that conveys a number of underlyingmessages that include the subsistence strategies and the success of thehunt. There is also subtle gender encoding that accompanies suchimagery.

Keywords: Negev; rock art; hunting; gender; Ibex

IntroductionThe Negev is located geographicallywithin the arid region extending fromSahara in the West and Arabia in theeast (Evenari, Shanan, and Tadmor1971, 8–9). It covers approximately13,000 square kilometers. The northern

border roughly extends from theMediterranean coast, south of Gaza, tothe southern basin of the Dead Sea(Hillel 1982, 73), generally following the200 mm precipitation line (Stern et al.1986, I). Northwest, the Negev graduallyblends into the Shefela Hills and coastal

*Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

Time & Mind, 2014http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1751696X.2014.956009

© 2014 Taylor & Francis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

plain, while in the Northeast it mergeswith the Judean Desert. The borderbetween the Negev and Sinai Peninsulais defined by the international borderwith Egypt. The eastern border, themost distinct, is formed by the Arava riftfault (Evenari et al. 1971, 43).

The Central Negev is composed of aseries of parallel ridges and synclinal val-leys running on a northeast-southwestaxis. The Nahal Zin canyon divides theregion into northern and southernhalves. The main rock art areas withinthe Negev stand within the CentralHighlands. It is within these areas thatthe nomadic herding communities havebeen adding their signature to specificrock outcropping for at least the past6,000 years. The earliest phases of thisunique rock art heritage commenceroughly towards the middle of theHolocene. The climate of the fourthmillennium BCE was slightly more favor-able than today, with increased amountsof precipitation resulting in large areas ofthe Negev being covered with vegeta-tion (Bar-Yosef 1982, 47; Horowitz1976, 66; Vaks et al. 2006; Roberts1989, 129–136).

Negev Rock Art: A ProblematicAssemblageNegev rock art motifs include a uniqueset of engraved images including abstractelements, anthropomorphs and zoo-morphs, along with inscriptions, handand foot/sandal prints, tools/weapons,and possible (free-standing) structuresand field systems. Most panels hostnumerous petroglyphs suggesting succes-sive narratives that are being appliedover long periods of time. Examiningeach panel, petroglyphs may be dividedinto engraving phases based on relative

darkness and coloration of the patinashade as well as the superimposition ofsuccessive images. The majority ofCentral Negev rock art is made byremoving patina, a dark-colored crust-like layer, from the stone that exposesa light-colored stone beneath. This con-trast makes fresh petroglyphs clearlystand out and be visible from a distance.Over time, the patina, caused by oxida-tion, begins to reform over the exposedlimestone rendering markings less visible.As witnessed with recent Bedouinmarks, newly developed patina is initiallylight colored, later darkening with age.Some very weathered petroglyphs havea patina as dark as the surrounding sur-face, making it difficult to perceive itsoutline and form. The engraved sectionalso weathers resulting in the oldestengravings being no more than a slightdepression within the rock surface. As ageneral rule, the darkest elements ofeach panel are the oldest within thepanel sequence.

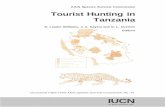

In-depth research of Negev rock artis relatively recent with the first recog-nized fieldwork undertaken in the TimnaValley, in the southwestern Arava, south-ern Negev (Figure 1). Here, BenoRothenberg (1972) concentrated ontwo large Late Bronze/Early Iron Agepanels, where a number of huntingscenes were identified. The huntingscene at this site was one of the mainthemes depicted. Engraved prey includedOryx (Oryx leucoryx), gazelle (sp.Gazella), ostrich (sp. camelus) and ibex(sp. Capra ibex nubiana). These herbi-vores were pursued by hunters andtheir dogs (Figure 2).

In his chronology of rock art stylesof the Negev and Sinai, Anati (2001,154) considered hunting scenes as oneof the principal activities depicted,

2 D. Eisenberg-Degen and G. Nash

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

representing five of the seven recog-nized engraving styles. We may thusconclude that hunting scenes were an

essential theme in the Negev rock art,though recent research could suggestotherwise (Eisenberg-Degen and Rosen2013). Research has suggested thatwhile hunting scenes are present, theyaccount for only a small percentage ofthe Central Negev rock art assemblage.

Of the 2000 rock art panels exam-ined from the Central Negev, only 39were found to include unambiguoushunting scenes. A further two panelsdepict a corralled wild animal. This maybe a slightly distorted low number ashunting scenes were included in theearly rock art engraving phases and assuch are very weathered or have beensuperimposed upon. To add to thesedifficulties, few of the Negev rock arthunting scenes are explicit enough toindicate an obvious hunting element.

The oldest elements are at timespartly or entirely covered by later, morerecent engraving phases. In many cases,panels were continuously engraved overseveral periods while nearby stonesremain untouched. Once a stone hasbeen defined as a “canvas” by one markmaker, others tended to mark it as well,thus creating a plethora of imagery anddesign encoding. On a selected numberof panels up to 12 different layers ornarratives have been be added. Earlierengravings are difficult to recognize. Forexample, in Figure 3, a panel from HarMichia, over 218 individual petroglyphs

Figure 1. Topographical map of Israel withsites mentioned in the text. 1. Har Michia andHar Arkov. 2. Giva‘t HaKetovot 3. RamatMatred 4. Har Karkom 5. Timna

Figure 2. Panel with hunting scene from Timna (after B. Rothenberg).

Time & Mind 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

are engraved onto the surface of aboulder; the various pictographic historiesare represented by numerous engravingphases. Some of the oldest images com-prise segmented lines (Figure 4). Here wesee deeply engraved and very dark paral-lel lines. Though the imagery in itsentirety cannot be seen due to weath-ering and superposition, we may tenta-tively assume that these lines representnumerous front and hind legs of

zoomorphs, most likely ibex. It is possiblethat using advanced photographic techni-ques such as Reflectance TransformationImaging (RTI) that these images willbecome more recognizable.

In identifying the different layers ofengraving (usually part of the recording pro-cess) there appears to be little subject con-nection between the various phases. Thiscould suggest that artists with different ideol-ogies/mindsets are completely ignoring

Figure 3. A plethora of imagery on a panel from Har Michia. (Degen/Nash.)1

Figure 4. Sets of very weathered parallel lines on the upper part of the southern face of thepanel. (Degen/Nash.)

4 D. Eisenberg-Degen and G. Nash

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

earlier narratives. At Har Michia, the earliestidentifiable scenes comprise ibex and anunarmed anthropomorph, in the followingphases hunting and combat scenes becomethe dominant theme. The repertoire of laterand more recent engraving phases is almostentirely composed of abstract motifs(Eisenberg-Degen and Rosen 2013). Fromthese clear subject-based phases, one canidentify the same phasing occurring withinmany areas of the Negev, suggesting arecognizable formulaic narrative beingapplied, similar to a myth of story that usesa series of primary binary associations and/or oppositions (see Levi-Strauss 1973). Bythis, we mean that each panel possesses adiscernible beginning, middle, and an endthat is visually interpreted as a sequence ofimages that either creates a story or at leastpart of a scene – a visual narrative. Lookingat the more densely engraved panels, eachphase in the sequence has its own definedvisual imagery; together they form a ‘seriesof histories’.

Hunting Scenes: Establishing ARecognized Visual NarrativeThis paper addresses two questions –

what are hunting scenes and what do

hunting scenes do? In general terms, hunt-ing scenes usually entail the depiction ofthe pursuit or the trapping of a wild ani-mal. These scenes may take a number ofgeneric forms (Monamy 2014):

● A single anthropomorph facing asingle zoomorph;

● Several anthropomorphs facing asingle zoomorph;

● A single anthropomorph pursuingseveral zoomorphs; and

● Several anthropomorphs pursuinga number of zoomorphs.

The majority of Negev hunting scenesdepict a single anthropomorph pursuinga single animal. The anthropomorph maybe standing or, occasionally, mounted ona donkey, horse, or camel, engraved in ariding position (Figure 5). A second cate-gory comprises multiple hunters on footor mounted, pursuing a number of wildanimals. A third category, though scar-cely represented, is of a group of hun-ters pursuing a single animal. Depictedhunted animals include gazelle, lion, oryx,ostrich, or, sometimes an unidentifiablezoomorph; though the most commonlyhunted animal is the ibex. Ibex are also

Figure 5. Mounted hunter pursing horned herbivore, panel from Ramat Matred. (Degen/Nash.)

Time & Mind 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

the most commonly depicted zoomorphin Negev rock art, but are usually unre-lated to hunting scenes.

There are several ways in which ahunt may be played out: a hidden orcamouflaged hunter may lie in wait fortheir prey, in which case the animal isunaware of the hunter’s presence; a hun-ter may track down and pursue the ani-mal, mounted or with the aid of a dog,or, alternatively, an animal may be direc-ted towards animal traps or enclosuressuch as desert kites.2

Elements that establish a huntingscene include the presence of anthro-pomorphic figures, weaponry, and zoo-morphs. When a panel possesses allthree within the same engraving phasethen all the elements of a hunting sceneare present. However, if the weaponryis unclear, then the identification of theengraving as a hunting scene is proble-matic. For example, in Figure 6, a panelfrom Har Karkom, an anthropomorph isholding an inverted L-shaped deviceand is partially superimposed by anibex. The lack of proportion and the

confusion from later engraving phases,in particular the horns of the ibex,makes the type of weaponry unclear.It is obvious that the anthropomorphand the ibex are physically connected,although a swastika-type symbol left ofthe ibex and the anthropomorph withup-raised arms and emphasized sexual-ity (whether male or female) right ofthe ibex, weaken the hunting scenescenario. Establishing that the presenceof weaponry is an essential componentfor identifying the concept of huntingcoheres with Levi-Strauss’s (1963) bin-ary relationship theory. In our view, thebinary relationship can be either con-frontational or passive.

Based on the Negev rock art data col-lected by Eisenberg-Degen (2012), wemay add the following to Monamy’s list:

● corralled wild zoomorphs;● wild zoomorphs associated with

funneling devices (i.e., desert kites);● wild animals depicted in relation to

weaponry only (without the pre-sence of anthropomorphs); and

Figure 6. Panel from Har Karkom presenting an anthropomorph, zoomorph and weapon thoughis not a clear hunt scene. (Degen/Nash.)

6 D. Eisenberg-Degen and G. Nash

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

● zoomorphs hunted by other zoo-morphs (e.g., hunting dogs andibex)

In the Negev rock art we see that somehunting scenes include an additional ele-ment, a second zoomorph accompanyingor at times replacing the hunter(Figure 7). When a hunting sceneincludes both anthropomorph and ‘hunt-ing zoomorph’, the anthropomorph maybe unarmed. Ibex and ‘hunting animals’are more frequently depicted than a fullhunting composition.

Within the Negev rock art assem-blage, as with most rock art traditionsworldwide, depictions of vegetation orlandscape such as hills or a line to repre-sent the ground surface are not depicted.In addition, anthropomorphic figures arerarely presented in movement.Anthropomorphs are usually presentedeither mounted on an animal (horse/donkey/camel) or as free-standing figures.These are presented in a minimalistic andusually linear style with the inclusion offew details. For example, only occasion-ally is the anthropomorph depicted with

feet (representing roughly 15% of theassemblage). Feet are presented in profileproviding a direction/orientation for thefigure. Running, leaping, dancing, andother activities portrayed in other rockart traditions are only suggested in theNegev rock art and never presentedwith true conviction (Figure 8).

Zoomorphic figures in the Negevrock art are similarly presented, in profilewith two and four legs. The desire to tiethe different elements (i.e., the hunterand hunted) together, with the limitedsize of the panel, and with the limitationsof style and tradition, has resulted in asingle human figure hunting a static ani-mal – two images that are stranded in avacant space (i.e., the panel). Depth offield and perspective are not clearly pre-sented. Here, the artist has taken his orher three-dimensional sight-line andtransformed and flattened the imageinto a two-dimensional entity onto thesurface of the panel. The result is a simplefigure superimposed onto the rock in themost straightforward fashion.

Understanding these limitations inartistic expression, prehistoric artists may

Figure 7. Anthropomorph excluded from a hunting scene. (Degen/Nash.)

Time & Mind 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

have been concerned with issues otherthan accuracy and detail. It is obvious thatthe components that create a landscapesuch as topography and vegetation inwhich the hunter may have stalked hisor her prey are missing. Therefore, inmany respects the viewer is drawn onlyto part of the panel narrative. We areforced to create our own landscapes andperspectives. For example, in Figure 9,from Har Arkov, two clear engravingphases are seen. The first phase includesan ibex presented in profile facing left.Behind the ibex, is an anthropomorphplaced horizontally. A bow is not clearlyseen though the upraised arms and shortline between them hint at a bow withdrawn arrow. The later phase is an archshape extending from the first-phased

ibex’s rear-end. The odd relationbetween the ibex and hunter may beexplained as follows: Either the hunter isindeed horizontal, lying on the ground ina ditch or perhaps behind a group ofboulders such as those on which thepanel was engraved, out of the sight ofthe ibex, or the hunter is presented hor-izontally in an attempt to portray per-spective; however, the hunter and ibexare not on the same plane.

Looking at another panel with a hunt-ing scene, it is evident that one interpre-tation cannot be offered for similarcompositions. In Figure 10, a hunter isportrayed with a bow and arrow.Accompanying this figure is an ibex andtwo additional zoomorphs. The hunter ishorizontally placed and is at a 90 degree

Figure 8. Possible running anthropomorph and later Arabic inscription. (Degen/Nash.)

8 D. Eisenberg-Degen and G. Nash

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

angle to the ibex. The distance betweenthe hunter’s legs and the addition of feetsuggest a forward (downward) move-ment. The first zoomorph, placed belowthe hunter and facing the ibex may beinterpreted as a dog. The second zoo-morph placed slightly distanced fromthese three figures appears to be of adifferent engraving phase and not partof the original composition (although,one can consider the concept ofenhancement to the original narrative).

The suggested movement of theanthropomorph goes against the ideasuggested for the Har Arkov panel(Figure 9). Here, the horizontally-

engraved hunter is lying down in waitfor his prey. The incorporation of a doglikewise negates a strategic ambush sce-nario. The dog element is presented withopen jowls, possibly barking. Barking ornot, ibex and dog do not naturally standfacing each other, nose to nose. Onceagain the hunting scene appears to bemore suggestive than a true account ofthe event.

The Karkom panel (Figure 10) servesas a good example of another recurringphenomenon – that of retouching andadding engravings to the initial engravingphase. As noted above, a zoomorphplaced above and to the right of the

Figure 9. Hunting scene from Har Arkov. (Degen/Nash.)

Time & Mind 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

ibex is a later addition (along with otherengraved figures). The male anthropo-morph seems to have three legs,although close examination of individualpecked marks and the shade of the threelegs show that the furthermost right ofthe three lines was made by a later artist.The third leg is actually an over-sizedpenis.

The addition and enhancement ofexisting engraved figures or alteration offigures made by later artists is a commonoccurrence and is repeated in many areasof the world where both engraved andpainted rock art exists. It also has its placein the contemporary world in the form ofhigh art and street art, in particular graffiti(Nash 2013). A good prehistoric exam-ple of this is found in Figure 11. Thispanel possesses three clear engravingphases, the first being the image of anibex with a distinct set of horns thatarch over the back of the animal. Theibex stands alone within in the center ofthe panel. At a later period, an artist hasdecided to set the image in a composi-tion by adding a set of images around.These include a zoomorph, probably a

dog and an anthropomorph. The anthro-pomorph, a male, has up-raised arms andis holding some form of weaponry. Thissecond phase of engraving has trans-formed the original lone, standing ibexfigure into a hunting scene that involvesa male hunter and his dog. The third andfinal engraving phase takes the form of ashort line placed between the ibex andhunter and a few small markings belowthe ibex and on the dog’s tail. These linesmay represent arrows and/or spears, sug-gesting a long-term fluid narrativewhereby successive artists add theirmarks to a well-established (and revered)scene.

The Hunt, Social Order, andEconomic StrategiesSeveral researchers have interpretedNegev rock art as depicting everyday lifeand economy (Anati 1962, 195; Nevo1991, 104–105; Oxtoby 1968, 25;Sharon 1990, 9*). There is no evidencethat this rock art was made by hunter-gatherers (although one cannot dismissthe possibility). On the contrary, the

Figure 10. Hunting scene from Har Karkom. (Degen/Nash.)

10 D. Eisenberg-Degen and G. Nash

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

rock art seems to have been a phenom-enon which developed after domesticgoat and herding was introduced intothe central Negev and as such the art isof a herd-based society.

In terms of the archaeological evi-dence, wild species account for approxi-mately 2% of the faunal assemblageswithin the Early Bronze Age of theNegev, whilst less than 9% account forthe Later Bronze Age (Forenbaher 1997;Horwitz and Tchernov 1989).Furthermore, we see that gazelle ratherthan ibex were the preferred animal tohunt between the Chalcolithic and EarlyBronze Age periods (Dayan et al. 1986;Hakker-Orion 1999: 327; Rosen andHorwitz 2005). Engraved herding scenesdepicting goat and penned animals (argu-ably the dominant livelihood of theNegev inhabitants from Early Bronzethrough to the present) are almostentirely missing, along with caravans andploughing scenes. The juxtaposition ofwhat is happening in reality and what isdepicted on the rock art sends out aconfusing message.

Although considered a minor role,the killing of animals in contemporaryhunter/gatherer societies is consideredmore than just a means of providingfood. Lee and De Vore (1968) haveshown that South African !Kung Bushpeople’s dietary intake consists of 60–80% vegetable foods. The remaining20–40% consists mainly of small inverte-brates (i.e., grubs and larvae, both ofwhich are high in protein). Studies offorest hunter-gatherers, too, emphasizethe dietary importance of gatheredfoods but also the heavily symbolic roleof meat, in particular, the way meat andfood in general become engendered.

Wild zoomorphic imagery by socie-ties sustained by domestic herds is notunusual; see for example the importanceof the bull and eagle in the sedentaryagro-herd based Pre-Pottery NeolithicCatalhöyük (Cauvin 2000, 28–32;Russell and Meece 2005, 106), and theibex at Ain Ghazal (Cauvin 2000, 106),and Chalcolithic-Early Bronze Age seden-tary agro-herd based Tall Hujayrat al-Ghuzlan (Schmidt 2009).

Figure 11. Hunting scene from Har Michia. (Degen/Nash.)

Time & Mind 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

This data works well with Jung’s(1991) research in Yemen which suggeststhat rock art of ibex hunting represents aritual act rather than an economicresource. Evidence of ritual ibex huntingperformed by people with agricultural-based economies comes from both pre-Islamic inscriptions (Beeston 1948) andtwentieth-century CE observations(Ingrams 1937; Serjeant 1976). The ibexhunting scene of the Negev likewiseseems to depict a ritual rather than areflection of the economy.

Could we be witnessing here someform of cult that is aligned to an ancestralhistory, whereby the “old way of life” wasbound up with the ritualization of huntingwild animals? Are wild animals a meta-phor for maleness and things that usedto be?

Moving Traditions and EconomyWith the slow transformation from ahunter-gatherer economy to domestica-tion and herding, several changes appearto have taken place. These are related tohuman cognitive behavior associated withthe notional concepts of wild versusdomestic animals, changes in use, percep-tion of landscape and division of labor;the latter concept indicating new genderroles. We suggest that the dominance ofibex engravings in the oldest engravingphases and how they are portrayedwithin the Central Negev is a reflectionof these changes.

Domestication is a process in whichcommunities through selective slaughter-ing, castration, and controlled siring andpenning (isolating a number of animals,limiting the gene pool, resulting in selec-tive breeding), have caused an alterationin the genetic composition and beha-vioral and phenotypic attributes of the

animal (Wenke 1984, 165–166).Domestication altered animal size, live-stock composition, and behavior. Withthe first stages of domestication, livestockwas controlled and reared. In the Negev,this change is identified through theadoption of what is termed pen andattached room architecture (Rosen 2008).Herds were either taken out to pastureor provided with seasonal feed. With theincrease in herd size (most likely a laterphase of herding) a need to pasture ani-mals further afield would have encour-aged communities to move out into thesteppes and semi-desert areas during thespring and early summer. The ability torely on milk from the herd would haveprovided the shepherds with an oppor-tunity to stay in remote areas for longerperiods of time (Martin 2000).

If domestic goat herds were intendedmainly as a meat source, then slaughter-age would have been within the firstthree-and-a-half years (Martin 2000).Ethnographic examples show that 50%of animals born each year (principallymale) are sold mainly for slaughter.Once a male has reached the age oftwo years, further investment in food ortime yields little additional return (Wenke1984). Dairy herds consist almost entirelyof females, with male goats culled beforereaching maturity. Domestic female ani-mals are usually hornless as well as smal-ler in size in comparison to similarly agedmales (Wenke 1984, 166). Wild herds ofmature males will differ from domesticones, in particular, in composition, physi-cal size and the existence of horns.

Artists’ Perception: Wild versusDomesticWith domestication, Neolithic commu-nities became livestock herders,

12 D. Eisenberg-Degen and G. Nash

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

controlling reproduction, assuring ade-quate pasture and water, as well asaffording protection from natural preda-tors. Human control over domesticatedanimals resulted in a fundamental changein human life, including that of the spiri-tual realm where certain animals are por-trayed on rock panels.

Ingold (1987, 247–255) has statedthat wild animals are regarded as mani-festations of an essential type of spiritsoul which is termed the animal “master”or “guardian”. The animal “master” is of ahigher order than other animal species. Insocieties that have no domestic livestock,humans and animals are seen as being onthe same level, being equal to oneanother. Animals are perceived as havingintellectual capabilities that are similar toor even above those of humans (Kent1989, 11–13). The animal world oftenrepresents creatures with magical orsuperhuman potency (Ingold 1987,245). Common themes in mythologyconsist of animals teaching humans cus-toms, skills, and knowledge; all of whichare necessary for survival. Not surpris-ingly, plants do not share these traits.

Based on the rock art imagery, thequid pro quo relationship betweenhumans and wild animals appears not tohave passed on to domesticated species.In societies that have domesticated ani-mals and hunt wild animals, the twoeconomies are seen as belonging toseparate categories. Wild animals andhumans form one category while domes-tic animals and plants form a second one.The design coding on certain panels sug-gest that domesticated animals arestripped of their intelligence and areviewed as more distant from humans(and more object-like). Despite this,domestic animals become socially,ritually, politically, and economically

different to their wild counterparts.According to numerous ethnographicexamples domesticated animals collec-tively become an important source ofpersonal and tribal wealth (Kent 1989,15–16) but at the same time lose theirindependent status – cattle become“head” and, goats and sheep become a“flock”.

Gender RolesThe transition from hunter-gatherers toherders most probably redefined genderroles. Cross-cultural studies of hunter/gatherer societies have shown that cer-tain divisions of labor are consistent.Ethnographic evidence suggests maleand female roles were rigid – hunting,gathering, food preparation, and feastingwere probably gender encoded(Ehrenberg 1992; Mateu 2002;Rappaport 1967). Phillips (1975, 26)reporting on gender roles within theSpanish Levent, argues that womenwould have been responsible foragingand collecting seeds, whereas menwould have hunted occasional big game;a similar social organization has beenobserved by ethnographers Lee and DeVore (1968). Meat appears to be animportant commodity where strict shar-ing rules apply. Apart from symbolic andritual uses, meat may also be of politicalsignificance. The equal sharing of meat inmost hunter-gatherer societies dispelsthe notion of hierarchy and economicvalue – the group becomes cohesive asone (Leacock and Lee 1982; Lee 1976).In !Kung and Mbuti society, the owner-ship of a killed animal by an individualcannot be regarded as ownership in thetrue sense of the word. Weaponry usedfor killing the animal are usually made byindividuals of the group and loaned to

Time & Mind 13

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

the hunter, thus reducing the legitimateright of direct ownership of the deadanimal (Lee and de Vore 1968, 369).Meat can therefore belong to morethan one individual, and its distributionallows everyone in the group to partici-pate in the sharing (Leacock and Lee1982). This may explain why someengraved hunting scenes involve largenumber of males stalking and killinglarge mammals.

In terms of contemporary domesti-city, sheep and goat herding is usuallyundertaken by women and children ofboth sexes (Köhler-Rollefson andRollefson 2002; Sinn et al. 1999; Shamiet al. 1990, 22). The age and sex of theshepherd depends on the size of theflock, the distance needed to travel forpasture and whether collective or indivi-dual transhumance is practiced (Olaizolaet al. 1999). A herd of up to 150-headled to daily pasture can be herded bychildren, irrespective of gender(Akkermans 1994). With domesticationand the growing size of herds, traditionalhunting was practiced less, as expressedthrough the reduction of arrowheads inthe Central Negev’s lithic assemblages(Rosen 2010) and human-animal contactno longer fell strictly within the malerealm (e.g., Lee and DeVore 1968).

The transition from a hunter-gathererway of life to a herding economy wouldhave affected many aspects of daily life.Although this transition would haveoccurred slowly over many generations,the histories and memories of the “oldway of life” would have transmitted viastory-telling and myth. It is from thisbackdrop that we see an increase in thedepiction of mature male ibex. Atroughly the same time, one witnesses achange in the rock art narrative.Verhoeven (2002) rightly points out

that bringing the undomesticated andwild into the domestic and ritual realmsis a counter-reaction to changes indomesticity. Wild animals may haveserved as a metaphor and mechanismfor exerting gender control over society,as well as metaphysically over nature. Thecontinued emphasis on the mature maleibex may have been a conscious devicefor this form of empowering malenesswithin the pastoral communities of theNegev. One can also consider that themaleness of the ibex (and the artist) maybe a metaphor for control over women.

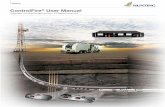

Concluding CommentsWithin the Negev rock art, zoomorphsare identified by their most characteristicphysical attributes such as the camel’shump, the donkey’s ears, and the ibex’shorns. The attributes of the ibex isemphasized many times. Generally, ibexare presented with extremely large andlong curvilinear horns such as those of amature male specimen (Figure 12).Similarly, human male figures oftenengraved with exaggerated male attri-butes, such as a large phallus. It is con-ceivable that both ibex and humanfigures represent potency [engenderedpower] and maleness. In simple termsthough, it is also possible that both aredepicted in order to clearly separate ibexfrom gazelle and oryx and the humanmales from females (and other ambigu-ous sexed figures). There is overwhelm-ing evidence though that engenderingmaterial culture is an important conceptwith most contemporary societies; geni-tals and breasts appear to be the mostwidely used representations in expressinggender and sexuality. Likewise, the hornsof wild and domesticated species mayhave metaphorically “acted” in a similar

14 D. Eisenberg-Degen and G. Nash

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

way (Nash 2008; Garfinkel and Austin2011).

With the identification of male andfemale figures, one may see many aspectsof the gender division within the markmakers’ societies (e.g., Tilley 1994). InNegev rock art females for the mostpart were depicted as being static, notengaged in any defined and recognizableactivity such as combat, hunting, or riding.This view of women goes well withTimothy Yates’ (1990) description inwhich women are domesticated, private,inside [hidden], and passive. By contrast,human male figures are characteristicallydepicted with weaponry. If weaponry isabsent, male figures are usually engravedwith raised arms. It would appear based

on the various stances that women helda less important role within society.However, it is more likely that the roleof engraving was a male concern, and assuch narratives are engraved through themindset of the male. Male figures withup-raised arms are presented with eitherover-sized erect penises or with anextended line between their legs. By con-trast, males with weaponry have ashorter line (representing a penis)between their legs (Eisenberg-Degen2013). As only males were armed, wemust assume that weaponry served as atype of gender marker, maybe acting as ametaphor for the penis.

Additional concepts may be pre-sented here; the first is that not all

Figure 12. Image of ibex with emphasized long horns from Giva’t Haketovot. (Degen/Nash.)

Time & Mind 15

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

anthropomorph-zoomorph relationshipslead or relate to trapping and huntingscenarios. For example, an ibex may beinterpreted as serving as a metaphor usedto depict hostile mountain dwellers (Kent1989, 14). Others have suggested thatibex represented qualities of virility,strength, and power (De Miroschedji1993). Tilley (1991, 167) has tentativelysuggested the concept of social reproduc-tion and power relationships within com-munities. Here, the ibex and hunterperform the acts of courting, bonding,and sexual intercourse; the two entitiesbeing indelibly linked. Based on these andother concepts, we promote the idea thatthe hunting of ibex may represent anengendered entity; that of the male hunt-ing the female (or vice-versa); each genderclaiming ownership over the other. Thisclaim has numerous ramifications thatinclude procreation, the success and long-evity of the clan group, territoriality, andthe continuing future of gender relations.

The full chronological sequence ofthe Negev rock art is, as yet not fullyunderstood but appears not to pre-datethe sixth millennium BCE. More complexengraving phases date to the Early BronzeAge and merge later to form domesti-cated scenes that include camel, donkey,and horse. As such, all documented pet-roglyphs so far represent an emergingpastoral-based society (Haiman 1998;Rosen 2002; Rothenberg and Glass1992). However, hunting was still in prac-tice, taken-up by pastoral societies,maybe as a supplement to domestication.One can consider, based on ethno-graphic studies, that the hunting of wildanimals represented a form of maleness,whereby hunting acted as a potent sym-bol of what would have been strictly amale concern (see Hodder 1990). Fromthis evidence, we can speculate that the

Negev rock art was not an account ofthe mundane activities of daily life, norwere the hunting scenes. What we areprobably witnessing here is parody andthe ideal scenario. The artist would nothave been concerned with artistic accu-racy but more likely a rationale to pro-duce a narrative that could dialecticallyread and understood.

Notes1. All images of rock art in this paper have

been digitally enhanced.2. Also found in the desert regions of Jordan,

Syria, and Yemen.

Notes on contributorsDavida Eisenberg-Degen is a specialist in prehisto-ric and contemporary rock art of the NegevDesert and works as an archaeologist at the IsraelAntiquity Authority, Southern District, Israel. She isalso affiliated to Ben-Gurion University of theNegev and the Negev Rock Art Centre whereshe is involved in a number of teaching programs.

George Nash is one of the executive editors ofTime and Mind, and is a part-time lecturer andVisiting Fellow at the Department ofArchaeology and Anthropology, University ofBristol; Associate Professor at the Spiru HaretUniversity, Bucharest, Romania; and SeniorResearcher at the Museum of Prehistoric Art(Quaternary and Prehistory Geosciences Centre),Macao, Portugal. George has undertaken extensivefieldwork on prehistoric rock art and mobility artthroughout many parts of the world and has writ-ten and presented for television and radio.

ReferencesAkkermans, P. M. M. G. 1994. Villages in the

Steppe Later Neolithic Settlement andSubsistence in the Balikh Valley, NorthernSyria. International Monographs inPrehistory. Archaeological Series 5.

Anati, E. 1962. Palestine Before the Hebrews.London: Jonathan Cape.

Anati, E. 2001. The Riddle of Mount Sinai:Archaeological Discoveries at Har Karkom.

16 D. Eisenberg-Degen and G. Nash

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

Valcamonica: Edizioni del Centro. StudiCamuni no. 21.

Bar-Yosef, O. 1982. “The Late PalaeolithicPeriod, the Pre Pottery Neolithic Period,and the Neolithic Period.” In The History ofEretz Israel Introductions the Early Periods,edited by E. Israel, 46–75. Jerusalem: Keter[in Hebrew].

Beeston, A. F. L. 1948. “The Ritual Hunt.”Muséon 61: 183–196.

Cauvin, C. 2000. The Birth of the Gods and theOrigin of Agriculture. Translated by T.Watkins. Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Dayan, T., E. Tchernov, O. Bar-Yosef, and Y.Yom-Tov, 1986. “Animal Exploitation inUjrat El-Mehed, a Neolithic Site inSouthern Sinai.” Paléorient 12: 105–116.

De Miroschedji, P. 1993. “Cult and Religion inthe Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age.” InBiblical Archaeology Today 1990, edited byA. Biran and J. Aviram, 208–220. Jerusalem:Israel Exploration Society.

Ehrenberg, M. 1992. Women in Prehistory.London: British Museum Press.

Eisenberg-Degen, D. 2012. “Rock Art of theCentral Negev: Documentation, StylisticAnalysis, Chronological Aspects, theRelation between Rock Art and theNatural Surroundings, and Reflections onthe Mark Makers Society through the Art.”PhD thesis, Ben-Gurion University of theNegev, Beer-Sheva, Israel.

Eisenberg-Degen, D. 2013. “Concluding the HarMichia Rock-Art Survey.” InternationalNewsletter on Rock Art 67: 11–15.

Eisenberg-Degen, D., and Rosen, S. 2013.“Chronological Trends in Negev Rock-Art:The Har Michia Petroglyphs as a Test Case.”Arts 2 (4): 225–252.

Evenari, M., L. Shanan, and N. Tadmor. 1971.The Negev the Challenge of a Desert.Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Forenbaher, S. 1997. “A Terminal Neolithic/Chalcolithic Assemblage from Har Harif(Central Negev Highlands).” Journal of theIsrael Prehistoric Society 27: 83–100.

Garfinkel, A. P. and Austin, D. R. 2011.Reproductive Symbolism in Great BasinRock Art: Bighorn Sheep Hunting, Fertilityand Forager Ideology. CambridgeArchaeological Journal 21:3, 453–71.

Haiman, M. 1998. “Nomads and Sedentary Sitesin the Negev Highlands during the EarlyBronze Age.” In Researches in theArchaeology of Nomads in the Negev andSinai, edited by S. Ahituv, 103–122. IsraelAntiquity Authority and the Ben-GurionUniversity Publishing House [in Hebrew].

Hakker-Orion, D. 1999. “Faunal Remains fromMiddle Bronze Age I Sites in the NegevHighlands.” In Ancient Settlements of theCentral Negev Volume I The ChalcolithicPeriod, The Early Bronze Age and the MiddleBronze Age I, edited by R. Cohen, 327–335.Jerusalem: Israel Antiquity Authority.

Hillel, D. 1982. Negev Land, Water, and Life inthe Desert Environment. New York: Praeger.

Hodder, I. 1990. The Domestication of Europe.London: Blackwell.

Horowitz, A. 1976. “Late QuaternaryPaleoenvironments of PrehistoricSettlements.” In Prehistory andPaleoenvironments in the Central Negev, IsraelVolume I, edited by A. E. Marks, 57–68. Dallas:Southern Methodist University Press.

Horwitz, L. K., and E. Tchernov, 1989. “AnimalExploitation in the Early Bronze age of theSouthern Levant: An Overview.” InL’urbanisation de la Palestine á l’âge duBronze ancient, edited by P. de Miroschedji,279–296. Part ii BAR International Series(527).

Ingold, T. 1987. The Appropriation of NatureEssays on Human Ecology and SocialRelations. Iowa City: University of IowaPress.

Ingrams, W. H. 1937. “A Dance of the IbexHunters in the Hadhramaut.” Man 37: 12–13.

Jung, M. 1991. “Research on Rock Art in NorthYemen.” Annali Istituto Universitario Orientale51 (1): 41–75 Supplement 66.

Kent, S., ed. 1989. “Cross-Cultural Perceptionsof Farmers as Hunters.” In Farmers asHunters the Implications of Sedentism, , 1–17. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Köhler-Rollefson, I., and G. Rollefson. 2002.“Brooding About Breeding: SocialImplications for the Process of AnimalDomestication.” In The Dawn of Farming inthe Near East Studies in the Early NearEastern Production, Subsistence, andEnvironment, edited by R. T. J. Cappers andS. Bottema, 177–181. Berlin: Ex Oriente.

Time & Mind 17

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

Leacock, E., and R. Lee, eds. 1982. Politics andHistory in Band Societies. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Lee, R. B. 1976. “The !Kung San: A Hunting andGathering Community.” In The Study ofCultural Anthropology, edited by D. E.Hunter and P. Whitten, 368–385. NewYork: Harper & Row.

Lee, R. B., and I. De Vore, eds. 1968. Man theHunter. Chicago: Aldine.

Lévi-Strauss, C. 1963. Structural Anthropology.London: Nicholson.

Lévi -Strauss, C. 1973. From Honey to Ashes:Introduction to a Science of Mythology Vol.2. London: Jonathan Cape.

Martin, L. 2000. “Mammal Remains from theEastern Jordanian Neolithic, and theNature of Caprine Herding in the Steppe.”Paléorient 25 (2): 87–104.

Mateu, T. E. 2002. La Representacion del CuerpoFemenino: Mujeres y Arte Rupestre Levantinodel Arco Mediterraneo de le Peninsula Iberica.BAR International Series. 1082.

Monamy, E. 2014. “Hunters and Warriors inRock Art: A Comparison between theSouthern Levant and the ArabianPeninsula.” Paper presented at The FirstInternational Conference on Rock Art inthe Negev Desert and Beyond, 27 March2013, Sde Boker, Israel.

Nash, G. H. 2008. Northern European Hunter/Fisher/Gatherer and Spanish Levantine Rock-art: A Study in Performance, Cosmology andBelief. Trondheim. NTNU, Norge.

Nash, G. H. 2013. “The Then and Now:Decoding Iconic Statements inContemporary Graffiti.” 25th ValcamonicaSymposium. pp. 437–446, Citta dellaCulture, Capo di Ponte (Italy).

Nevo, Y. D. 1991. Pagans and Herders A Re-examination of the Negev Runoff CultivationSystems in the Byzantine and Early ArabPeriods. Midreshet Ben-Gurion: IPS.

Olaizola, A. M., E. Manrique, and M. E.LópezPueyo, 1999. “Organization Logics ofTranshumance in Pyrenean Sheep FarmingSystems.” Options Méditerranéennes, Série A,38: 227–230.

Oxtoby, W. G. 1968. Some Inscriptions of theSafaitic Bedouin. Ann Arbor: AmericanOriental Society.

Phillips, P. 1975. Early Farmers of the WestMediterranean Europe. London: Hutchinson.

Rappaport, R. 1967. Pigs for the Ancestors. NewHaven, CT: Yale University Press.

Roberts, N. 1989. The Holocene: AnEnvironmental History. London: Blackwell.

Rosen, S. A. 2002. “The Evolution of PastoralNomadic Systems in the SouthernLevantine Periphery.” In In Quest of AncientSettlements and Landscapes: ArchaeologicalStudies in Honour of Ram Gophna, editedby E. C. M. van den Brink and E. Yannai,23–44. Tel Aviv: Ramot.

Rosen, S. A. 2008. “Desert Pastoral Nomadismin the Longue Durée. A Case Study fromthe Negev and the Southern LevantineDeserts.” In The Archaeology of Mobility, edi-ted by H. Barnard and W. Wendrick, 115–140. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute ofArchaeology, University of California.

Rosen, S. A, 2010. “The Desert and the Sown:A Lithic Perspective”. In Lithic Technologyin Metal Using Societies. Proceedings of aUISPP Workshop, Lisbon, September 2006,edited by B.V. Eriksen, 203–210.

Rosen, S. A., and L. K. Horwitz. 2005. “GivatHayil 35: A Stratified Epipaleolithic Site inthe Western Negev.” Journal of the IsraeliPrehistoric Society 35: 201–228.

Rothenberg, B. 1972. Timna Valley of the BiblicalCopper Mines. London: Thames & Hudson.

Rothenberg, B., and J. Glass. 1992. “TheBeginnings and the Development of EarlyMetallurgy and the Settlement andChronology of the Western Arabah, fromthe Chalcolithic Period to Early Bronze IV.”Levant 24: 141–157.

Russell, N., and S. Meece. 2005. “AnimalRepresentations and Animal Remains atCatalhöyük.” In Catalhöyük PerspectivesReports from the 1995–99 Seasons, editedby I. Hodder, 209–230. Cambridge:McDonald Institute for ArchaeologicalResearch/London: British Institute at Ankara.

Serjeant, R. B. 1976. South Arabian Hunt.London: Luzac.

Shami, S., L. Taminian, S. A. Morsy, Z. B. El Bakri,and M. K. El-Wathig, 1990. Women in ArabSociety: Work Patterns and Gender Relationsin Egypt, Jordan, and Sudan. New York: Bergand UNESCO.

Sharon, M. 1990. “Arabic Rock Inscriptions fromthe Negev.” In Archaeological Survey of IsraelAncient Rock Inscriptions Supplement to Mapof Har Nafha (196) 12-01, edited by Y.

18 D. Eisenberg-Degen and G. Nash

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014

Kuris and L. Leder, 9*–35*. Jerusalem: IsraelAntiquity Authority.

Schmidt, K. 2009. “Tall Hujyrāt al-Ghuzlān – theWall Decorations.” In Prehistoric Aqaba I,edited by L. Khalil and K. Schmidt, 99–112.Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf.

Sinn, R., J. Ketzis, and T. Chen. 1999. “The Roleof Woman in the Sheep and Goat Sector.”Small Ruminant Research 34: 259–269.

Stern, E., Y. Gradus, A. Meir, S. Krakover, and H.Tsoar. 1986. Atlas of the Negev. Beer-Sheva:The Geography Department, Ben-GurionUniversity.

Tilley, C. 1991. Material Culture as Text: The Artof Ambiguity. London: Routledge.

Tilley, C. 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape:Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford:Berg.

Vaks, A. Bar-Matthews, M. Ayalon, A. Mattews,A. Frumkin, A. Dayan, U. Halicz, L. Almogi-

Labin, A. and Schilman, B. 2006.“Paleoclimate and Location of the Borderbetween Mediterranean Climate Regionand the Saharo-Arabian Desert asRevealed by Speleothems from theNorthern Negev Desert, Israel.” Earth andPlanetary Letters 249: 384–399.

Verhoeven, M. 2002. “Ritual and Ideology in thePre-Pottery Neolithic B of the Levant andSoutheast Anatolia.” CambridgeArchaeological Journal 12 (2): 233–258.

Wenke, R. J. 1984. Patterns in PrehistoryHumankind‟s First Three Million Years. 2ndEd. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yates, T. 1990. “Archaeology through theLooking-Glass.” In Archaeology afterStructuralism Post-Structuralism and thePractice of Archaeology, edited by I. Baptyand T. Yates, 153–204. London:Routledge.

Time & Mind 19

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Geo

rge

Nas

h] a

t 13:

49 1

0 Se

ptem

ber

2014