HOUSING THE STRANGER: SOCIAL RESILIENCE IN POST CONFLICT AREAS

Transcript of HOUSING THE STRANGER: SOCIAL RESILIENCE IN POST CONFLICT AREAS

HOUSING THE STRANGER: SOCIAL RESILIENCE IN POST CONFLICT AREAS Assist. Prof. Dr. Beril ÖZMEN-MAYER, TOROS University, MERSIN, Turkey, [email protected], [email protected] Ugo K. Elinwa, Eastern Mediterranean University, North Cyprus, [email protected], [email protected]. Housing is one of the very essential needs of humanity. With the alarming global growth rate in post-conflict zones, it is thus very important to consider housing as an important factor that plays a major role in resilience of the inhabitants. Indeed, this concept cannot be totally developed unless a clear picture of the past is not understood and properly outlined in light of current circumstances. This study focuses on conflict as a man-made disaster that has caused different levels of losses, migration, displacement and the eventual resettlement of different groups of people, who are living in the locality of Asagi Maraş /Kato Varosha, a district adjacent to the borderlines of the ghost city of Maraş / Varosha in the city of Gazimagusa / Famagusta. As of today, the area is still battling with the effects of the intervention as it has been cordoned off and left partially abandoned since1974; even if housing construction has become a very important sector in other districts and cities in the island for the economy of the northern land. This study thus tries to understand the factors, which pose as internal problems served by inhabitants for recovery in the study area to understand the mechanisms for conflict mitigation. Therefore, resilience in this study is seen as involving the community, their housing environment and economic sustainability in order to improve the quality of life of the different groups of resettled inhabitants. Analysis of the standard of living is undertaken and presented as different layers of information from the users, understanding of the situation, needs and comments obtained from past housing situation, present phenomena and their future implications. With all the pros and cons tackled, this paper suggests active roles that the local institutional bodies could play in rebuilding a community and boosting its characteristics to withstand adverse future occurrences. Keywords: Adaptation, Housing, Post-Conflict, Resettlement, Resilience.

1. INTRODUCTION Conflicts and struggles as all other man-made catastrophes have influenced residential settings thus affecting the routine of everyday life practices in the existing urban environments. In many situations, conflicts lead to migration, displacements, resettlement and a process of re-building in different forms in the quest for safety in a recovery process. Over the years, urban housing development has been greatly influenced by informal settlements due to urbanization on a global level. However, complexities in post conflict situations may influence especially informal housing settings and cannot simply be unraveled by application of housing systems but require a deep understanding of the abounding difficulties. Therefore, housing resettlement and social resilience should be considered together during the recovery process from all types of disasters. Understanding this process involves both active and passive strategies that are all encompassing in rebuilding the society both in terms of inhabitants’ psychology and the physical environment as a whole. This should be viewed both as formal and informal components of the society through the reforms of policies and institutions (Kumar, 1997). As defined by the free online dictionary, conflict could be any of these situations; state of often prolonged fighting; a battle or war; disharmony between incompatible or antithetical persons, ideas, interests or a clash. In psychology is a psychic struggle, often unconscious, results from the opposition or simultaneous functioning of mutually exclusive impulses, desires, or tendencies. Opposition between characters in a work of drama or fiction stands for especially opposition that motivates or shapes the action of the plot. A most often times misplaced notion of identity and existence arising from an array of many socially, culturally and politically constructed realities culminates in a very deep disappointment floored on an inability to meet varying expectations. This disappointment so many times births a deep eating uncertainty with no form of assurance of affirmation or even a tiny bit of communal synergy in view. Conflicts are very much inevitable because every individual is born with varying innate affiliations and as growth progress, these innate affiliations gradually integrate into strategically augmented responsibilities stretched beyond a wild horizon of differential interests. This state of difference is where conflict is birthed. There is no point blank reason for why conflicts arise apart from differences in interests which most often times are more internally navigated than externally. Many often times, conflict is interchanged with physical violence but it isn’t necessarily physical violence solely. Conflict as it is first debuts in the mind before its effects impact on people, their lives and their practices. A careful articulation of the psychological “state of being” coupled with the metaphysical context of existence are at the bottom line of the disparate preferential diversities of human beings. When conflicts arise, they never leave the players the same. There are many sides to this coin in that conflicts cause a lot of hurt, so much pain and are most often times associated with loss. The state of mind of a fore bearer is perceived first as psychotic, mentally in shambles, sick or just plain deranged. When peace talks are initiated, some people arise to challenge the possibility of perfect peace because they claim there conflict was born when human beings were born. Even where there is physical peace, people’s thoughts are constantly conflicting because of either cultural or behavioral heterogeneity. Such people project the idea that man is naturally structured to kill when in the path of anything that seeks to threaten his life. These claims are more treacherous than real. There is no theory anywhere backed up by sane claims that an average human being has a natural propensity to kill many thousands of humans like him. This projected idea stems from minds that harbor and crave violence and stop at nothing to perpetrate same. There indeed is no natural predilection of any sort to propagate violence or accommodate its excesses as it

relates to human life. People who postulate such theories and even go as far as defending them ought to be put under severe scrutiny precedent to proper mental and psychological evaluation. Under the carefully thought out pattern of political and social synchronicities, various institutions are consequently at the base of reforming violence against certain marked out crimes as majorly punishable by violence alone. Often times, very intense conflicts lead to either or all of the following; displacement, relocation, resettlement, migration, emigration and certain other imbalance in the society. It is important to note here that in any case of relocation, whether resulting from natural or human–induced disasters, the best approach to resettlement is a plan that is well accepted by the affected population as well as stakeholders in disaster management programs (Anon, 2010). Thus, this research attempts to examine inhabitants’ reactions in the light of contemporary theoretical inputs and narratives in the case study area. Bearing in mind that the attachment that individuals get from a place is greatly influenced by the satisfaction they derive from that place (Connerly & Marans, 1985), the pursuit of social adaptation in the study examined informal operations on home-making in the selected districts by paying attention to the views of innumerable inhabitants. Methodology is based on the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods for understanding the realities and analysis of data collected. By applying structured interviews, it pays close attention to the social characteristics and housing practices of the settler groups in the area, while considering the different levels of fragmented social cohesion. The study adopts a retrospective inquiry into the effects and reactions of individuals to their present housing structure. These individuals include three categories of people, namely; those from southern region of the Cyprus Island, who were displaced as a result of the conflict due to the ethnic exchange program; those who migrated from Turkey as a result of the incentives promised by the government, and those who have been living in the area over the years from birth. There are others such as leaving the island to the foreign countries (UK and Australia) when conflict starts in early years, and coming back when the land is divided into a more secure places for them as another case of migration due to different conflict periods. The limitations of this study are centered on certain uncontrollable factors as a result of, either the users own drawback or restrictions imposed by the government in the case study area, such as the unwillingness of respondents to open to discuss certain issues pertaining to the conflict; and illegality that exists with respect to land ownership and disputes.

2. CONFLICT AS a MAN MADE DISASTER

Disasters have become one of the greatest plagues of mankind and can either be natural, man-made or sometimes hybrid. They are considered to have either direct or indirect effects, which can be tangible or intangible in nature (Mileti, 1999), (Figure 1). While the tangible effects are directly linked with monetary figures, the intangible effects are linked with irreplaceable losses. According to United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, disaster is a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or society causing widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses, which exceed the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources (Wamster, 2006).

Figure1: Indirect impact of disasters (Authors)

Conflict is a human catastrophe that has crippled humanity from historical times (Gosselin, 2005). In general terms, conflicts can be sub-grouped under disasters, which require a reconstructive process of recovery that are all encompassing in rebuilding the society. In this case, recovery is not restricted to a psychological balance; rather it involves both the physical and the non-physical components of the environment. In fact, people in the society are hit by disasters differently and their reactions are in many cases based on individual differences and age. For instance, in times of conflict, the high-risk individuals consist of children, elderly people and in some cases women. Apart from the death rate, internal migration and international migration, the collapse of the economy, amongst others, there are also other stress related syndromes, which could be induced by memories of the conflict or the lurking fear in the minds of individuals.

“The war was more devastating for the weaker and less tolerating people such as children, women, elders, and patients. The conflict also helped in raising a generation of children who believe that war and destruction are regular elements of life instead of considering them as negative aspects” (Muhanna, 2008).

Conflicts in very extreme cases may lead to a civil war, which becomes a major threat to sustainable development, and it destroys the social, economic and ecological resources that are desperately needed to improve the welfare of people and the viability of communities and the planet. In terms of the economic effect of conflict, there is little that has been written in recent times as relating to this issue (Carbonnier, 1995). Neverthesless, contemporary conflicts are conflicts of the city. The challenge is to find ways of renewing that civilization which undermines the causes of conflict and enables us to revitalize cities and society, so that we may harness urban forms for peaceful social life (Shaw, 2003). In his book entitled ‘There was a country’ renowned author, Prof. Chinua Achebe laments on the effect of conflict in a different context though;

“But the Biafran war changed the course of Nigeria… it was a cataclysmic experience that changed the history of Africa. There is a connection between the particular distress of war, the particular tension of war, and the kind of literary response it inspires” (Achebe, 2012)

Mileti (1999) points out a significant term associated with disasters “out migration”; moving from one location to another in search of livelihood, having lost their source of income or livelihood to disaster. In this study, disasters are viewed as induced problems or activities seen not as an act of nature, but man-made. One very good example of disaster-induced migration is the aftermath of the 1974 Cyprus conflict. In the case of Maras, there was a

Conflict

Indirect

Tangible

General economic disruption

Household Economic disruption

Intangible

Increased hazard

Vulnerability of survivors

Out- Migration

significant pattern of displacement which gave rise to a phenomenon known as “forced migration” and “mass place reshuffling”. This usually occurs when two groups of people are forced to exchange their housing and the current place of settlement (a geographical displacement, you may call it). The question thus remains: “have they recovered from the conflict?”

3. BUILT ENVIRONMENT & HOUSING

The built environment usually suffers the most from the effects of conflicts; with the destruction of houses, infrastructures and various communal establishments. However, the basic need of man of which shelter is a necessity, becomes an important issue for consideration in post disaster situations. The response of different sectors of the economy involved in housing provision plays a crucial role in this dimension. It is claimed that post conflict housing reconstruction projects that overlook users’ needs and local variations in physical and socio economic conditions lead to dissatisfaction on the part of residents and ultimate remodeling by themselves or rejection and abandonment (Barakath, 2003; Barakath et al., 2004). These factors highlight the importance and necessity of addressing conflict-affected communities’ housing reconstruction needs in post conflict housing reconstruction.

Housing is an important part of every individual’s existence. According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 25.1),

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control”.

One of the major issues encountered in war and conflict situations is the problem of settling the category of displaced individuals, which in this case could be grouped and termed homeless. Rossi et al (1987) suggests two distinct classes of homeless people. They include the “literally homeless” and people who are “housed in uncanny conditions”. Several approaches have been made towards understanding and deciphering these broad contexts, but one method that seeks to holistically give insight into the context of displacement and homelessness is the anthropological approach.

“Careful and intensive fieldwork, and a philosophy of cultural relativism, that is, understanding how each element of culture fits into the larger cultural context without passing moral judgments, form the intellectual underpinnings of anthropological homelessness research” (Bridgman and Glasser, 1999).

It is a common observation that most conflict-plagued regions are faced with housing devastation. Where to go from here seems to be the ultimate question asked by the victims. This gives some hint as to why many agencies, non-governmental and humanitarian are constantly and increasingly focusing their energy and interest in housing. Though these efforts are visibly in place, there is still a huge gap between the complexities that exist in post disaster housing as it also relates with cultural sensitivity, the built environment and the need for sustainable developments. According to Twigg (2002), “most post-disaster housing reconstruction projects are agency-driven and have a narrowly technical approach”. Barakath (2004) and Duyne (2005) further stressed that “they entail the employment of construction companies that consider modern building technologies the only option to achieve hazard-resistant houses”. In post- disaster housing reconstruction plans, it is also important to take

into consideration the lifestyle and culture of the local community, the values of the people and the characteristics and implications of their housing type or types before the occurrence of the disaster. More often than not, organizations that in normal times are committed to sustainable development, in an emergency context often make technological choices without taking into account socio-cultural, environmental and economic implications (Barakath, 2004 and Duyne, 2006). Although there are numerous researches by various organizations and scholars, post-disaster housing reconstruction and resettlement schemes is considered by many experts as one of the least successful sectors in terms of implementation (ALNAP, 2002). 3.1 OBSERVATIONS FROM THE MARAS / VAROSHA Famagusta is one of the major cities on the island of Cyprus. A city with a rich cultural heritage (Walsh, Coureas, Edbury 2013) much of its economic and socio-cultural values were seemingly lost as a result of the war in 1974, which forced a strong disconnection of the city from the sea through its organic link. With the sealed off area covering a land mass of about 6.4square kilometers, this conflict, forty years later, has still not given a chance to the city to develop its own master plan. Based on the so-called “Declaration on Varosha Breakthrough Package”, a report by (Atai et al, 2010), there was a significant 46% drop in touristic records between 1973 (population census) – June 2010 in Famagusta. However, Famagusta today seems to be picking up again on her toes, but the populations of Turkish Cypriots who live by the walls of this division seem not to be part of the general re-development happening in Famagusta. Like in many other cases, the conflict caused different levels of losses, migration, displacement and the eventual resettlement of displaced individuals.

Figure 2: Magusa - Famagusta Map

magusa city ……………………….. municipality

borders

The$City$growing$along$the$axis$through$the$seaside$$Unplanned$growth$

Changing$the$direction$of$the$urban$development$after$1974$

Borders$

$$Ghost$$$$$$$city$of$$$$$$$$$$Maras$$/$$$$$Varosha$Kato$Varosha$$a$

Hotels$Zone$

The selected Asagi Maraş district of Famagusta, has undergone extreme transformations, and exhibits an extra ordinary existence in terms of variety of user groups and their housing environments. Accordingly, the area becomes a laboratory of accommodations in the city due to this neglected part not being built-up properly with a cohesive policy in last decades, with relevant strategies such as inclusive and participatory ways for rebuilding the society. The city has seemingly lost lots of its population, much of its economic, socio-cultural values and touristic sites as a result of the strong disconnection of the city from the sea through its organic link (Atai et al, 2010). On one hand, the Magusa city has a weak relationship with the sea due to the restricted south-end of the city with a border changing the direction of new urban developments along the seashore. On the other hand, non-existence of a master plan brought about an unplanned growth and lack of re-creative public green and facility areas. (Figure 2). Furthermore, radical population alterations have occured, demographic and ethnic profile of citizens has dramatically been changed. At the same time, floating citizens (university members and students) have increased due to several student groups on the island (such as16, 500 students from the local University in the city, which in ratio is nearly a quarter of all inhabitants). As a result, an increase in the population of the “young” can be observed in the overall urban sphere and comprises of different nationalities. Considering the case study area, Maras, although it has been about 40 years since the conflict, the study adopts a retrospective inquiry into the effects and reactions of individuals to their present housing structure due to exchange of the ethnic population across the island.

“Architecture is deeply engaged in the metaphysical questions of the self and the world, interiority and exteriority, time and duration, life and death.” (Pallasmaa, 2005)

This mass movement happened against their free will to relocate, but relocation was necessitated by the conflict. It is also important to note that this mass movement was not based on equal numbers of people moving from one place to another. Out- migration could be viewed in this case as being a problem that could affect or influence the total recovery of disaster areas since it gives the opinion or feeling that the affected area might still be unsafe to dwell in. The scale of out-migration matters a lot and could be the yardstick for measuring the safety level of a place after a disaster. This form of migration could be seen as the secondary effect of an intangible reaction to the indirect impact of a disaster (Smith and Ward, 1998) (Figure 1). Apart from the many questions this research will provide answers to; the research seeks to answer the complications involved in resettlement and the quest for stability after a conflict situation. There are various approaches involved in post-conflict recovery; however, the study tries to question various practices in disaster recovery in post conflict situations as it relates to housing. Therefore, an in-depth enquiry in the study area is carried out to understand the nature of the resettlement and the pattern of movement and development that have resulted from the woes of the conflict. It actively considers the experience of place as approached from a multi-dimensional perspective in order to fully explore the different intricacies in experiences, culture, social and political aspects of a place to review the cases. 3.2 HOUSING RESILIENCE Resilience as being a constructive measure, which serves as a positive approach to dealing with risks of psychological challenges as it affects an individual, family or community. First important factor within the term of resilience is adversity or risk, which points out ‘negative life circumstances’ associated with adjustment difficulties. The second one is ‘positive

adaptation’ defines social competence or success at meeting outstanding developmental tasks. Thus, identifying ideas should be understood clearly in linking with relatively positive or negative outcomes among particular at-risk groups in a resilience research. To discuss the relationship on resilience and implementation of social policies will be the next step after specific case analysis. Therefore, one of the major needs of after a disaster, is a systematic approach towards rebuilding the affected area (Luthar and Ciccethti, 2000). It should be noted that among all other policies, achieving an effective postwar reconstruction policy is obviously the most stringent (Coyne and Cowen, 2005). According to Luther and Ciccethi (2000), this framework gives a detailed understanding the particulars involved in dealing with cases of vulnerability. A good study on resilience should be able to properly identify and outline factors that are potential indicators for vulnerability and protection. The vulnerability level of the affected individuals has a major effect on their response to the recovery from a conflict. These factors could play out in negativities arising from risky conditions, which could undermine the efforts of intervention workers. Factors of vulnerability include the determinants that could worsen risk conditions of an already existing negativity. On the other hand, the protective factors minimize the risks that could arise from negative conditions (Luthar, 2000). The concept of resilience connotes the idea of a ‘fight back’. A resilient city is thus one, which has the ability to “bounce back to equilibrium in the face of adversity" (Pendall et al, 2012). According to OCHA, record shows that an estimated number of 25 million people across 52 different countries are currently living as displaced individuals. The factors responsible for such displacements include disasters, both natural and manmade. Although they are displaced, these individuals still remain within the borders of their own countries. This phenomenon has given rise to what is globally accepted and termed as Internally Displaced Persons. The concept of resilience and sustainability go hand in hand and can be used to diffuse complexities arising from housing strains. In this study, resilience can be viewed from three perspectives: the government, the people and the environment (Figure 3). The resilience paradigm can be considered for social policies. This approach considers several advantages, precautions and limitations and documented studies on resilience with a view to accurately and strategically providing a guide for interventions in high-risk conditions.

Figure 3: Mechanism on Housing Resilience (Author)

RESILIENCE

Governance

Environment People

Ecological

Social

Economic

Institutional

Infrastructure

Community competence

There are numerous literature records that show the relationship of health and housing quality (Keall et al. 2010). In many cases, a community is considered as being resilient when such undermining factors of poor housing do not eventually result to adverse health conditions. This suggests a relational link between neighborhood economy, housing quality and health. Poor Neighborhood does not always result in poor housing and bad health conditions. In very rare cases, however, a combination of a rich neighborhood and poor housing quality could also result in bad health conditions. Studies reveal that over the years, a huge intellectual effort has been concentrated on resilience in terms of housing provision and the providers of such housing for disaster victims. There has however been little concentration on resilience in terms of “place” rebuilding through psychological perceptions, which tend to stigmatize a disaster-affected region. It is evident that housing types, density and street layout play hand in hand in determining the cohesiveness of a society and the implicative impact it has on resilience with a sense of community (O’ Compo et al, 2009). It therefore is important to investigate the quality of housing and also test the varying factors that could influence output in housing resilience. ‘Housing quality ratings’ is one of the determinants for investigating the quality of housing in a region. At the household and neighborhood levels, there are important factors for consideration. Household size, age group, income level, education, government policies, land tenure and network systems. Quality ratings are high when there is an effective provision of support systems for the smooth functioning of the community. Support systems include material development, resources management that enhances the safety of the households and their sense of belonging. The availability of proper institutions and infrastructures boosts the ability to withstand external shocks (Adger, 2000) The deployment of resources to neighborhoods and residences is for the satisfaction of households and the community. Satisfaction in this case is affected by both tangible and intangible determinants such as, physical and social characteristics, personal experiences from previous housing environments and the technologies in place (Oktay et al, 2009 and Pacione, 2001). 3.3 SUSTAINABLE APPROACH TO HOUSING RESILIENCE It is no doubt that there have been a couple of documented literatures talking about sustainability and housing. However, in this case, the study approaches resilience from a different perspective that is centered on improving the quality of health and wellbeing of the community. Reducing carbon emission and energy conservation are important items to be considered during the rebuilding of housing in affected areas. As a result of the conflict, the unresolved dispute over land resulted in the closure of certain areas close to the perimeter of the study area. This has given rise to the decay of buildings within this closed area. Good housing conditions are an important requirement for ensuring total recovery from a disaster. The houses in the case study area appeared to be lacking basic provisions such as proper drainage and refuse disposal systems. After disasters, interventions from several organizations seldom pay attention to climate and the needs of the people. The goal is basically to provide shelter as quickly as possible especially for people who have been displaced. Going by the definition of ASHRAE (2004), comfort is reached in interior spaces when at least 80% of the occupants within a space are comfortable with its thermal condition, there is however a need to consider climatic constraints in the design of houses to ensure thermal comfort and reduce the risk of health challenges. Consideration of building environmentally friendly housing or green estates within this area that could serve as a base for other reconstructions to take place in place. As

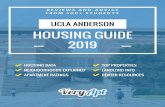

electricity demand and supply to households account for one of the needs of the neighborhood, the idea to integrate houses with photovoltaic collectors was conceived to be integrated at the design stage while paying attention to aesthetics and environmental control. The preferences of the potential users in the study area are also considered. With the current look of housing and infrastructure in the study area, a point of view should be made for construction companies and other agents involved in housing provision to take up a different approach to housing so as to have a more resilient neighborhood that could attract people back to living in this area. Currently, there is seemingly an alienation of the study area from the rest of the city’s social, physical and economic conditions. The study revealed that the residents in the study area were mostly people in low-income groups. The respondents are from the low income earners comprised of retirees, job seekers and the aged people (some of who as the time of the study had serious health issues), the high income earners comprised of military service men and the middle income group comprised of tradesmen (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Income level of Responders (Authors)

In the attempt to remake a place, housing cannot be overlooked. Combining technology with tradition, climate and the needs of the people in a very harmonic manner that does not disrupt the smooth flow of the community is the best approach to ensuring a sustainable result. 3.4 CAPACITY TO ADAPT When we consider a community with respect to its adaptive capacity or capability, we are simply trying to analyze and understand the ability of that community to adapt to change. What one community is able to adopt to could be very much different from what another community will be able to adopt when faced with similar threats or challenges. As referenced by Margurie and Cartwright (2008), the capacity of a community to adopt / or what is known as adaptive capacity can be interpreted or defined as the “the ability or capability of a system to modify or change its characteristics or behavior to cope better with actual or anticipated stresses” (Brooks 2003, p.8) Adaptation is not simply accepting change but it is a response to change / stressors. How a community reacts to a stress factor or stress factors. Thus it becomes useful to understand resilience and adaptation can only be effectively assessed after a change has occurred. A combination of various adaptive capacities and available resources (both natural and manmade) in a productive manner determines the strength of resilience of a community. This makes the community a flexible one which in fact increases it resilience. Maguire and Cartwright (2008) present a conceptual framework of resilience, vulnerability and adaptive capacity. In this framework, a deficit model is introduced as an outcome oriented approach which considers vulnerability as a deterministic state. Viewing vulnerability from this perspective makes it possible to quantify vulnerability in comparative terms.

0" 5" 10" 15"

Fig.7 Income level of Respondents

High"Income" Middle"Class" Low"Income"

3.5 SOCIAL ASSESSMENT Social assessment involves a process of data collection, sorting and analysis. The data gathered is detailed information about the community. This process is all encompassing as it seeks to determine the motivating factors for resilience within a community. It involves both the people within the community and stakeholders. This is necessary as it affects the formation of future policies binding on that community. Integrating the public in harmonious engagement with the community could greatly determine the success level to be achieved. According to Burdge and Vanclay (1995), examples of data collected for social assessment of communities include; population, characteristics and nature of the group, social organizations present within the communities, the history of the community and the lifestyle of people within it, beliefs systems, norms and values, and the available resources. It is important to note at this point that the essence of carrying out a social assessment is not to label any community as not being capable of adapting change. Instead it aimed at spotting potential challenges or weaknesses within the community and then proffering solutions that could help boost the ability of a community to overcome the challenges. According to Stenekes et. al (2008), in order to ensure that a community is involved in the social assessment process, a systematic approach could be developed in the form of negotiations, collaboration and cooperation.

4. REMARKS FROM THE CASE STUDIES

The case studies were carried out in the borderline areas especially Kavunoglu and Gazibaf Streets, in Asagi Maras due to their strategic location. There are lots of issues to deal with such as unorganized premises, poor outlook, squalor settlement and different groups of inhabitants. According to Moore (2000) “people put years of effort into transforming their houses into homes, which, in turn, reflect their individuality and/or identity”. It could be argued that the general condition of the houses in that area leaves the inhabitants in a state of inconvenience. Majority of the people living there tend to adopt a mindset set to cope with the existing condition of houses allocated to them after the conflict and to later transform them according to their needs: “Like food and fashion, houses were a cultural index of wealth and sophistication. Hence, alterations and additions over the years reflect the changing social fabric of the community, wealth, prestige, and expanding households”. (Grass Valley Department, 2014): Housing analysis from the interviews with the owners or occupants formed a background for keywords used in this study. They defined the problems based on how they felt about their home environments; such as lack of engagement, need for empowerment, certain types of discriminations they face, previous housing experience and memories. ‘Lack of Engagement’: Feeling less than fully engaged at work or community activities is a troubling matter that hinders living life to the fullest. Those inhabitants lacked engagement, most of them were bored and sometimes holding back. Engagement level has a lot to do with success and satisfaction. If one is not fully engaged, then it is likely that they will be unhappy, unhealthy or even unproductive. Therefore, something needs to be done to fix the lives of these refugees. ‘Lack for Empowerment’: To give somebody power or authority is like honoring his presence in a dignified manner. Those refugees immigrated from the southern part of the island with probably very little concern, from those who held power in that region. As a result, here in

their resettled location, they seem to have lost their feelings and this has become a major problem for which an ultimate solution should be proffered. We found out that their increasing unpleasant situations are due to the lack of engagement and empowerment. The government undermines support for empowerment of immigrants in many ramifications. ‘Previous Experience’: One of the deep wounds that cannot be eradicated from the hearts of the refugees is the previous unpleasant conditions they had been subjected to. Based on an interview with one of the immigrants, he said that the previous condition under which he lived and the current one cannot be compared, stating he lived in a good and safer house then than he currently is living in now. ‘Discrimination: It exists when different treatments are applied to people in different groups. Discrimination is a common experience—not an unusual one. It was discovered that the immigrants always felt discriminated, when they compared the treatment from the government in relation to their living conditions as opposed to the treatment others get. They expect what is called ‘‘disparate-treatment’’ to ease off their previous negative feelings.

5. FINAL SYNOPSIS

On the overall, the discussions, theories, concepts and research findings, accumulated in the area of “human- environment studies”, are arguable on two extreme ends. One is; adaptability of human beings to any environment; the latter is determination of physical environment on human behavior. For instance, the notion of environmental opportunities has been reviewed as in 'probabilism' model by Rapoport (1977) as provision of opportunities and constraints of physical environment where there are possibilities for choice, and is not determining, but in a given physical setting some choices are more probable than others. People make choices for various reasons, circumstances and rules, which can be developed depending on some specific conditions of their immediate environment. Therefore, people are limited by the set of environmental and spatial opportunities in a situational or contextual manner as Lawrence (1987) argued. However, certain activities require particular means of support from an appropriately designed or facilitative environment, in which, people can make choices about the opportunities available to them with respect to personal, individual, social values and goals, related mostly to their lifestyles. There is no deterministic relationship between human requirements and physical settings since both individual and group requirements can be satisfied in other ways such as changing of economic, social or cultural conditions; people are able to modify the immediate conditions of their environment, and not remain hopelessly tangled with the environment. Northern Cyprus is a small country with a population of approximately, 265 000 people as recorded in the 2006 census. This result includes all foreign nationals such as international students, academics, EU citizens who prefer to live in Cyprus and foreign military forces. Being a small community, one can imagine a strong network of Turkish Cypriot families (relatives and cousins in every corner of the country). In retrospect, we could state that this situation contributes positively to the overall housing satisfaction such as feeling at home, sense of belonging, known neighborhood, and intensity of friendship or kinship bonds. This statement is supported by some studies which have focused on social factors, such as the intensity of friendship or kinship bonds within a community, having a significant positive effect on the perceived level of safety and satisfaction. The profile of owners in their neighborhoods gives the impression of each house / home as

somehow good or satisfactory to the owners. Each household accepted their present house as satisfactory from the findings during the examination of different cases of housing settings. In deep down, rather than highly competitive western societies around the world, people seem to be more content with what they have, owning a house is a determinant for a level of satisfaction to what they have achieved or possess, being able to provide a shelter for their family and their future generations. It does not matter how, what kind or for whom. Owning a shelter is symbolic of success, of realization among other issues in Cyprus, which are impossible to solve at the moment. It shows this achievement as a status, contribution and sense of belonging in a given settlement. Another issue is some users still have possibility to build their houses with little contribution from architect in rural cases, or easily can change the housing layout as a result of minimal control at the phase of application of constructions. Finally, ‘Soul Touching' experiences from various researchers and educators give light to the notion that there is quite a challenging agenda in this fast growing world in search for ways to contribute professional knowledge at various scales, through architectural practices, design teaching. Hope is growing in most of the habitations; the displaced individuals (from the Southlands) who were relocated to this region are gradually moving to the other parts of the city of Famagusta, which are in good conditions in terms of public services and development. On the other hand, the families who are not original immigrants from the South but immigrants from Turkey are pleased to live here (Asagi Maras) to own some land and an informal house setting, even though they may move again if an opportunity avails itself with a more suitable living condition somewhere else in the city. With all the dramatic issues here, there are still ‘hopes’ to be re-united.

LIST OF REFERENCES Achebe, C. 2012. There was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra. Allen Lane, England. Atai et al, Declaration on Varosha-Famagusta Breakthrough Package. http://magusainsiyatifi.org/index.asp?page=251 Anon, 2010. Safer Homes, Stronger Communities: A Handbook for Reconstructing after Natural Disasters. the World Bank, Washington DC. ALNAP Annual Review, 2002. Humanitarian Action: Improving Performance Through Improved Learning. ODI, London. ASHRAE 90.1 (2004), Energy Standard for Buildings, Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings, the States and Municipalities including Minnesota, Maine, Nevada and the Code of Federal Regulations at 10 CFR 433.4. Barakath, S. 2003. Housing Reconstruction After Conflict and Disaster. Network paper number 43. Humanitarian Practice Network, Overseas Development Institute, London. Barakath, S., Elkahlout, G. & Jacoby, T. 2004. The Reconstruction of Housing in Palestine 1993-2000: A Case Study from the Gaza Strip, Housing Studies, 19(2), pp. 175-192.

Bridgman, R. and Glasser, I., 1999. Braving the Street. Berghahn Books, NY.

Carbonnier, G. 1995. Conflict, Postwar Rebuilding and the Economy: A Critical Review of the Literature. Occasional Paper No. 2, War Torn Societies Project, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

Comerio, M.C. 1997. Housing Issues after Disasters, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 166-178.

Connerly, C., and Marans, R.W. 1985. Comparing Two Global Measures of Perceived Neighbourhood Quality, Social Indicators Research, 17, 29-47.

Coyne, C and Cowen, T. 2005. Postwar Reconstruction: Some Insights from Public Choice and Institutional Economics. http://ppe.mercatus.org/sites/default/files/publication/postwar_Reconstruction.pdf, (Accessed 20th Dec.2012) Duyne B., J. 2005. A Comparative Analysis Of Six Housing Reconstruction Approaches in Post-Earthquake Gujarat. World Habitat Research Centre & ESZ, Lugano. Gosselin, R. A., 2005. War Injuries, Trauma, and Disaster Relief. Techniques in Orthopaedics, 20(2):97–108, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc., Philadelphia. Grass Valley Department, Architectural Legacy of Grass Valley. http://www.cityofgrassvalley.com/services/departments/admin/CDD_Downloads/HistoricContextAppendices.pdf

Keall, M. et al 2010. Assessing Housing Quality And Its Impact O Health, Safety And Sustainability. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 64, 765 – 771. Kumar, K. ed. 1997. Rebuilding Societies after War. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Colorado. Lawrence, R. J., 1987. Housing, Dwellings and Homes: Design Theory, Research and Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Canada. Luthar, S. S. 2000. The construct of resilience: Applications in interventions; Keynote address, XX-XII Banff International Conference on Behavioral Sciences; Banff, AB, Canada.

Luthar, S. S. and Cicchetti, D., 2000. The Construct of Resilience: Implications for Interventions and Social policies, Dev Psychopathol; 12(4): 857–885. Mileti, D. S., 1999. Disasters by Design: A Reassessment of Natural Hazards in the United States. Joseph Henry Press, Washington DC. Muhanna, K. 2008. No place for Children during the War: Lebanon Case. http://www.amel.org.lb/aaimages/pdf/childrenhavenoplaceinwar.pdf, O’Campo, P., Salmon, C., & Burke, J. 2009. Neighborhoods and Mental Well-Being: What Are The Pathways? Health & Place, 15, 56 – 58. Oktay, D et al. 2009. Neighborhood Satisfaction, Sense Of Community, And Attachment: Initial Findings From Famagusta Quality Of Urban Life Study, University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, VOL: 6 NO: 1 6-20 2009-1,Ann Arbor, USA. Pacione, M., 2001. Urban Geography - A Global Perspective. Routledge, London. Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin, 2005. Architecture and the Senses, p. 16. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester, West Sussex, England. Pendall, R., Theodos, B. and Franks, K. 2012. Vulnerable People, Precarious Housing, and Regional Resilience: An Exploratory Analysis, Housing Policy Debate, 22:2, 271-296. Rapoport, A. 1977. Human Aspects of Urban Form, Pergamon Press, Oxford.

Rossi, P.H., J.D. Wright, G.A. Fisher, and G. Willis, 1987. “The Urban Homeless: Estimating Composition and Size.” Science, 2(3), 1336-1341.

Shaw, W. H. (2003), Nozick in Zimbabwe. Journal of Social Philosophy, 34: 215–227. doi: 10.1111/1467-9833.00176

Smith, K., and R. Ward, 1998. Floods: Physical Process and Human Impacts, p. 376, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester. http://asprs.org/a/publications/pers/2000journal/october/2000_oct_1185-1193.pdf , (Accessed, Jan. 2013) Statistics New Zealand. (1998). New Zealand now: Housing. Wellington, New Zealand.

Twigg, J., 2002. Technology, Post-Disaster Housing Reconstruction and Livelihood Security. In: Technology for Sustainable Development. DFID, Infrastructure and Urban Development Department.URL: http://livelihoodtechnology.org UNISDR, 2009. Terminology and Disaster Risk Reduction.

Walsh, Michael J. K., Edbury, P. W. and Coureas, N. S. H. 2012. Medieval and Renaissance Famagusta: Studies in Architecture, Art and History, Ashgate Publishing Limited, London.

Wamsler, C. 2006. Managing Urban Disasters: Open House International Journal, 31(1), 4 – 8. ISSN 0168 – 2601.