Hong Kong Mambo

Transcript of Hong Kong Mambo

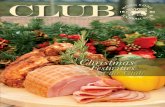

Figures 1 – 3. Grace Chang plays the singing and dancing teenager Kailing in the opening number of Mambo Girl (dir. Evan Yang [Yi Wen], Hong Kong, 1957).

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

The Hole (dir. Tsai Ming-liang, Taiwan, 1998) is one of a number of contemporary Chinese-language films that invoke the past by way of sonic reference. The film is about a nameless man and woman living in present-day Taipei, played by Lee Kang-sheng and Yang Kuei-mei, respectively, who are drawn into a series of encounters when a hole appears in the wall dividing their apartments. Most of the story transpires in muteness, within domestic spaces that barricade as much as shelter these characters. Somewhat improb-ably, though, a voice from beyond periodically punctuates the sound track: that of the 1950s and 1960s Hong Kong singer and actress Grace Chang. The Hole contains several musical interludes staged in a highly theatrical fashion at odds with its otherwise aus-tere realism. In these interludes Chang’s songs are lip-synched by Yang Kuei-mei as she dances in flamboyant costumes, sometimes flanked by backup dancers or accompanied by Lee Kang-sheng as leading man. The songs include Latin Caribbean–style dance tunes like “Calypso,” the playful pop melody “Achoo-Cha Cha,” and a Mandarin rendition of the American jump blues hit “I Want You to Be My Baby.” In the film’s final frame, a handwritten inter-title signed by the director names the vocalist as an inspiration: “In the year 2000, we are grateful that we still have Grace Chang’s

Hong Kong Mambo

Jean Ma

Camera Obscura 87, Volume 29, Number 3

doi 10.1215/02705346-2801496 © 2014 by Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

1

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

songs with us. — Tsai Ming-liang.” The unabashedly nostalgic and personal tone of this epigraph is all the more striking in light of The Hole’s futuristic atmosphere, its story unfolding in an anx-iously surreal but recognizable setting that gestures at the far side of the impending millennial transition. Against the bleakness and anonymity of contemporary life, the film suggests, the colorful past embodied in Chang’s music promises a last refuge for feeling and intensity, the triumph of fantasy over banality, and the sur-vival of humanity in a literally dehumanizing universe (everyone in the film is turning into cockroaches).1

The Hole can be credited with introducing Chang’s songs — if not her image — to audiences around the world, including many too young and geographically removed to have encountered them in their original context. But for a certain generation of viewers throughout the Chinese diaspora, as the epigraph intimates, these songs would have carried a special resonance as twice-heard tunes, recalling a bygone era of popular film and music. The Hole pays tribute to one of the most celebrated performers of the postwar Hong Kong – based Mandarin film industry. Like many other film workers of her time, Chang was part of a wave of migration described by Poshek Fu as the “Shanghai – Hong Kong nexus,” referring to the heavy flow of people and capital across the two regions from 1935 until the closing of the border in 1950.2 Dur-ing these years, waves of migrants poured into Hong Kong, nearly quadrupling its population. Among these were a large number of writers, critics, filmmakers, musicians, and performing artists who would play an important role in the colony’s rise as a new center of cultural production for the Chinese-speaking world. Chang departed Shanghai with her family in 1949, at the age of fifteen, and soon afterward began her training as an actress and singer. In 1955, she entered into an exclusive contract with Motion Picture & General Investment Co. Ltd., also known as MP&GI. The pro-duction studio, along with its rival, Shaw Brothers, was one of the main driving forces behind the efflorescence of the Hong Kong film industry in the postwar period. Both studios were founded by Chinese Malaysian property magnates — Loke Wan Tho and Run Run Shaw, respectively — who saw a lucrative opportunity in the

2 • Camera Obscura

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 3

export market for Chinese-language films throughout the trans-pacific diaspora in the Cold War years. They turned to Hong Kong as a stable environment in which to pursue commercial filmmak-ing. In Fu’s description, the films made by the two major studios reflect the “cosmopolitan, border-crossing consciousness” of the producers and their common desire to forge a polished, technically sophisticated, modern cinema with cross-regional appeal.3

The Mandarin film industry of postwar Hong Kong has been largely sidelined in historical accounts even though it marks a crucial juncture: the emergence of Chinese cinema’s first full-fledged, vertically integrated commercial studio system.4 The vast majority of English-language scholarship on Hong Kong cinema focuses on the Cantonese-language film industry that was consoli-dated in the 1970s, a moment that postdates the disappearance of Mandarin and other dialect industries from the colony’s film-making landscape. While the kinetic action genres that are today objects of worldwide fixation and cultish veneration have their roots in this later phase of Hong Kong filmmaking,5 a glance at the preceding decades reveals a very different genre ecology — one dominated by romantic and family melodramas, historical costume epics, and opera films. In contrast to the kung fu and swordplay films and crime thrillers that serve as platforms for displays of mar-tial prowess and masculine heroic ideals, postwar film culture was characterized by a distinctively feminine orientation, anchored in female-centered dramas and reigned over by actresses who out-shone their male costars both on-screen and in fan magazines. The primacy of female performers is also written on the sound tracks of this time when, to use an oft-cited phrase from the popular music historian Wong Kee-chee, the idea of “no film without a song” became something of an industry watchword.6 Film songs were a ubiquitous feature of postwar Hong Kong cinema, transcending the boundaries of genre, and their performance was the exclu-sive domain of female vocalists and actresses. Many of the biggest stars of this period, like Chang, moved fluidly between the movie and music industries to simultaneously pursue careers as screen actresses and recording artists. Singing actresses sustained a film culture in which music featured as a principal attraction and

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

4 • Camera Obscura

enshrined a regional tendency toward crossover stardom that con-tinues to the present day. (Consider, for instance, the deceased but not forgotten megastar Anita Mui, who was an acclaimed actress as well as a Cantopop star extraordinaire.)

The songstresses of Chinese cinema call to mind equivalent figures from filmmaking traditions around the world: in Holly-wood, stars like Jeanette MacDonald, Marlene Dietrich, Deanna Durbin, and Doris Day; the chanteuses réalistes of French cinema in the 1930s and 1940s; enka singers of Japanese cinema, such as Misora Hibari; and the playback singers of Indian cinema, like Lata Mangeshkar. But postwar Chinese cinema lacks the male musical counterparts that are found in these other realms. Its singing stars are with few exceptions women, while men contribute to musical performances chiefly as composers, instrumentalists, or occasional duet partners. The feminization of vocal performance can be explained partly by recourse to what Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh describes as the “female-centered musical amusements” of the modern era. The term songstress, or genü, originally referred to “female enter-tainers who [sold] nocturnal delights to pleasure-seekers in colonial Shanghai.”7 These genü, who commanded teahouses, cabarets, and musical revue stages, continued to maintain their central position with the advent of mass-mediated music, moving into the sphere of radio performance and phonograph recordings. The modern popular music industry that arose in the early twentieth century saw a dearth of male vocalists and was dominated instead by female singers like Li Minghui, Zhou Xuan, Yao Lee, Bai Hong, Gong Qiuxia, and Ouyang Feiying.8 The transition to sound filmmaking in the 1930s paved the way for these vocalists to cross over to film acting, and as their voices penetrated the soundscape of early Chi-nese cinema, their personas were mythologized on-screen in stories about the plights of hapless genü and wandering songstresses.

Surveying the songstress films of the early sound period, Zhang Zhen observes that throughout these works the female voice stands out as a locus of ambivalence. It is at once alluring and imperiling in its effects, the cause of both the singer’s spectacular rise and her downfall (or death), and “the site of both dramatic and social tension associated with new technology.”9 The conflicting

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 5

thematic meanings of glory and danger thus associated with the singer speak to her embodiment of the unstable juncture of sound and image. These two registers converge not in seamless integra-tion, Zhang notes, but rather as a host of nonsynchronous effects and polyphonic meanings spinning out in unexpected directions across the fractured spaces of mass consumption during the first decade of sound filmmaking. But the ambivalent portrayal of the voice was not only a reflection of the new technologies that enabled its circulation, for another dimension comes into focus as we step back to consider the songstress as part of a longer history of gen-dered tropes extending to silent filmmaking. The imagination of the songstress as a magnet for misfortune and exploitation calls to mind the melodramatic plights that showcased the talents of renowned silent film actresses such as Li Lili and Ruan Lingyu. The singing women of Shanghai sound cinema are kin to the fallen women of the silent screen, where, in the words of Miriam Bratu Hansen, “female protagonists serve as the focus of social injustice and oppression; rape, thwarted romantic love, rejection, sacrifice, prostitution function as metaphors of a civilization in crisis.”10 Like the fallen woman, the songstress is consigned to exploit her body, looks, and voice for a living, often to support others as well as herself and along the way violating traditional prescriptions of gender, visibility, and domestic versus public space. Both the song-stress and the fallen woman more often than not meet a tragic end that betrays the deep anxieties surrounding women, performance, and publicity in the age of mass media.11

The postwar generation of songstresses that includes Chang appears at first glance to be a species apart from the fallen women of the pleasure industry long associated with Shanghai’s colonial era. In the postwar cinematic landscape, the tragic singers of old are joined by feisty country lasses, high-spirited teenagers, college coeds, and cheerily efficient working women. For film historians like Sam Ho, the updated songstress announces a new sensibility and ethos in Hong Kong cinema. Her appeal seems to anticipate the forward-looking mind-set of a younger demographic poised to move beyond the memories of hardship and suffering endured by the wartime generation of migrants. Thus, Ho writes, “The pros-

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

6 • Camera Obscura

pect of the music woman turning away from her tragic fatalism to sunny, homespun optimism is closely related to the changing view of society in the cinema.” In the changing social climate of the 1950s, the old-style songstress, “with her deprived upbringing and tragic disposition, felt absolutely out of place,” while by contrast her newer counterparts appeared “decidedly urban and authentically Hong Kong.”12 But the tragic chanteuses of old do not simply fall by the wayside. Closer scrutiny of postwar film culture reveals that the relationship of the old songstress to the new consists less of the pro-gressive displacement of one by the other than by, more precisely, a fraught series of renegotiations that involve the dynamics of repetition, disavowal, return, haunting, and revision. I trace these complex renegotiations in the discussion that follows, approach-ing Chang’s persona not as a straightforward instantiation of a new type of modern girl but rather as a locus of tensions between old and new gender prescriptions and between progressive and reactionary values. These tensions are dramatized and expressed across the registers of sound and image, spectacle and diegesis, and sensory address and narrative explication.

The Birth of the Mambo GirlChang made her debut as a star in the 1957 MP&GI production Mambo Girl (dir. Evan Yang [Yi Wen], Hong Kong), considered by many critics to be the single most representative work of postwar Mandarin cinema. Her character is introduced with a flourish in the film’s famous opening scene, which commences with a shot of a pair of feet in white ballet flats tautly poised in a dance step, accompanied by the vigorous pounding of bongo drums. As the chorus shouts, “Mambo — oomph!,” the feet launch into action. The camera tilts up to reveal legs clad in capri pants with a bold harlequin print that echoes the checkered floor, then a torso, then a bouncing ponytail. A female voice bursts into song, and finally, the dancing body with her back to the camera turns to reveal the radiantly beaming visage of Chang herself. The careful orchestra-tion of her dance moves, the music, and the camera’s movements produces a seamless gestalt of rhythm, energy, and dynamism

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 7

through which the figure of the songstress springs to life and takes musical flight. These moments can be described as a drama of embodiment, staging an expressively forceful convergence of body and voice. Just as the vertically moving camera shows us fragments of a female figure in sequence — feet, legs, hips, torso, head — so the voice that sings the first notes of the song is cut off from this figure seen initially from behind. Chang whips around to face the camera and with this gesture asserts her ownership of the voice, now synchronized with her facial movements; the cam-era tracks back gradually to frame her entire body, caught up in the physical exertion of song performance. The remainder of the scene alternates between frontal medium close-ups that capture the action of singing and long shots that display her dance moves, cut to the song’s rhythm. Throughout the performance the cam-era does not stray from Chang; thus the performance is authenti-cated by the collocation of voice and body, grounded in the aura of the songstress (figs. 1 – 3).

Mambo Girl introduced to Mandarin cinema the persona of the bubbly, carefree, singing-and-dancing teenager. This archetype would quickly catch on and reappear in numerous other films in the mold of Mambo Girl, which was affiliated with the emergent global genre of the youth film. The film’s reenvisaging of the songstress rides the wave of the invention of the teenager, a phenomenon rooted in the socioeconomic conditions of postwar prosperity; the institution of the nuclear family; and a budding consumer culture of fashion, music and dance, and automobiles. The reification of the teenager as a pop icon is announced in no uncertain terms by Mambo Girl’s rather odd opening credit sequence. A series of line drawings of dynamic dancing figures provide the backdrop for a doll realistically rendered as a young adult woman. Reminiscent of Mattel’s Barbie in its general appearance, it is posed as if in interaction with the two-dimensional images. The doll is styled to resemble Chang as she appears in the opening scene, with dark hair pulled into a ponytail, and attired in the mode of a stylish Western teenager. At the end of the credit sequence, the image of the inert doll is replaced by the animated figure of Chang herself — an uncanny juxtaposition that reinforces both the sense of a

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

8 • Camera Obscura

rhythmic transition from stillness to motion and the self-conscious drama of a static prototype springing to life. The transition also foreshadows the character’s repeated association with dolls and toys in the course of the film, an association motivated by her par-ents’ occupation as the proprietors of a toy shop above which the family lives.13 The visual rhyming of Chang’s character with the doll as commodity object discloses the basis of her character as being modeled upon the preexisting iconography of the teenager and as setting forth an object of identification and consumption aimed at a youth market.

To be sure, the teenager did not fully arrive on the scene of Hong Kong cinema until nearly a decade after Mambo Girl, when the colony’s baby-boomer generation came of age and made its presence felt across a broad spectrum of popular media — from film to television and radio programs, from tea dances to guitar bands and their screaming fans. A glance at the films of this later phase of postwar culture, which depict antisocial impulses, delinquent behavior, and youthful rage against a hypocritical adult society, sets into relief the particular contours of Mambo Girl’s protagonist. Chang’s character, a high school student with extraordinary musi-cal talent named Li Kailing, is less rebellious teenager than filial Chinese daughter. As the film’s opening musical sequence contin-ues, the camera pulls back from its tight focus on Chang’s dancing form to reveal a circle of friends who surround her, clapping and chanting along. Kailing sings:

Clinking glasses, bumping chairsShaking bodies, racing pulsesLoud shouts and frenzied dancesEverything is wild as I amAs wild, as wild, as wild as I am

Everybody clap, everybody cheerIf you feel the rhythm, jump right inLoosen your ties, take off your coatsEverybody come and join in and beAs wild, as wild, as wild as I am

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 9

The impression of raucous all-night partying summoned by the song’s lyrics is negated, however, by the scene’s visual framing. What viewers see is in fact a rather anodyne picture of teenage revelry: a group of respectable middle-class youth channeling their effusive energies into a coordinated performance of song and dance under Kailing’s musical leadership. As if to announce that this is a representation of youth intended to reassure adults as much as appeal to young people, Kailing’s mother enters the room with a tray of refreshments and is warmly greeted by the gang. The gathering, viewers discover, takes place in the Li fam-ily’s home under full parental supervision, a fact reiterated in the song in due course:

No matter how wild the party isSing and dance ’til dawn, it’s all rightJust revel to your heart’s delightBecause this is my home, my heaven.

The lyrics encapsulate the scene’s constitutive incongruity as a literally and figuratively domesticated portrait of modern teen-age culture, the newness and strangeness of which are brought into the safe fold of the family home. The effect of the songstress’s performance is not to transgress the protocols of polite sociality but rather to bring together friends and family and consolidate a community. This incongruity is further mirrored within the song itself: despite its verbal invocation of disinhibition and unruliness, its musical idiom is conventional and old-fashioned by the pop standards of the time, calling for a disciplined style of vocal deliv-ery that conforms to traditional ideals of bel canto singing and expressly shows off Chang’s classical training.

In this opening scene, music functions as the medium of youth’s physical expression, and the link between the two is cemented further in the course of Mambo Girl. Musical perfor-mance is associated with the social spaces of youth culture and folded into a rhythmic alternation of school and play. In particular, the film mines the sensational interest of the dance party as a social ritual of modern teenage life. Not only does it begin with a teenage

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

10 • Camera Obscura

dance party, but it also ends with a scene that mirrors the film’s opening: Kailing and her friends gather once again in her home and dance to a rock-and-roll medley that evokes contemporaneous Hollywood films like Rock around the Clock (dir. Fred F. Sears, US, 1956). The musical idiom of the last scene and its choreographic display of rocking, rolling, and swinging bodies points to Mambo Girl’s debts to the emergent genre of the American rock-and-roll musical. Rock-and-roll musicals, as David E. James argues, played an important role in propagating not just the sounds of rock but also “the visual components of the cultures that formed around it: dance styles and body language, fashions in dress and hairstyle, posters and album covers, and so on.”14 Mambo Girl coincides with the initial phase of a cycle that began in the mid-1950s and under-went intense development for the next decade, marking the global reach of the rock-and-roll wave and participating in an ongoing process by which new popular forms of music were disseminated, remediated, and socially recoded in their encounters with cinema. In purging the potentially transgressive components of youthful musical expression, Mambo Girl can be seen as consistent with what James identifies as a dominant tendency in the American rock-and-roll musicals of the late 1950s: narratively severing the music’s associations with juvenile delinquency, sexual release, and working-class and African American culture.15

Mambo Girl establishes the key traits that would come to define Chang’s star persona: her multifaceted musical genius and her charismatic embodiment of modern feminine identity. Chang consistently sang her own songs in her films, nearly all of which contain musical sequences expressly designed to showcase her vocal talent. In the course of her career she also produced numer-ous recordings. Her extensive training in a wide range of musical styles — including traditional Chinese opera and classical and con-temporary Western music — was noted repeatedly in the publicity discourse surrounding her films. At various turns she played the roles of college student, ambivalent fiancée, young wife, and career woman. Mary Wong takes note of Chang’s roles in June Bride (dir. Evan Yang [Yi Wen], Hong Kong, 1960), where the actress portrays a soon-to-be bride who begins to question the marriage her father

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 11

has arranged for her, and Air Hostess (dir. Evan Yang [Yi Wen], Hong Kong, 1959), where she plays a recent graduate who spurns a marriage proposal in order to pursue a demanding career in the glamorous air travel industry. Such portrayals, Wong observes, were “rare for 1950s and ’60s Hong Kong films” and suggest an active reflection on modernity mediated through a female point of view and channeled by the dilemmas and choices faced by Chang’s characters.16 Viewed from this angle, Chang’s filmography reveals much about the new ideals of femininity promulgated by MP&GI within the context of an industrializing, capitalist, and cosmopoli-tan society.

But as Mambo Girl shows, the depiction of the modern female subject in Chang’s films also carefully filters out those ele-ments that might strike a disconcerting chord. Even when engaged in activities that fly in the face of conventions of proper feminine behavior, Chang’s characters rarely stray from the approval of the family members, peers, and coworkers who surround her. Mambo Girl is indicative of the ways in which Chang’s films contend with the implicit threat of her unconventional behaviors by domesticat-ing her characters, bringing them in line with dominant familial values and gender norms. The figure Chang depicts here and in many of her other vehicles is sunny to the point of relentlessness and wholesome and upright to the point of unbelievability. The staging of Chang’s songs in The Hole underscores this point by deliberately magnifying their discordance with the contemporary reality painted by the film — one that bodes viral epidemic, eco-logical disaster, and the breakdown of social infrastructure in its dramatization of the mood of crisis provoked by the millennial transition. With their exuberant energy and flamboyant theatri-cality, The Hole’s musical numbers carve out a utopian oasis within this otherwise overwhelming dystopian setting. The film invokes Chang’s voice as a shell of the idealism of an earlier, perhaps more innocent era, as a sign of deferred promises of a better life, and as a remnant of postwar mythologies of modernity and upward mobil-ity. In overlaying the dreams of progress spun in the past upon its own degenerative imagination of the future, The Hole constructs a refracted temporality, one that is split between proleptic anticipa-

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

12 • Camera Obscura

tion, nostalgic retrospection, and a distanced present. This elusive temporality is encapsulated in the disjunction of sound and image, for Chang haunts the film as an acousmatic phantom, a presence heard but never seen. The power of her voice to evoke the sense of an elsewhere and another time, whether past or future or both at once, resides in its unlocatable position beyond the threshold of visibility.

In hyperbolizing the incongruity between its musical num-bers and narrative, The Hole also calls attention to contradictions present all along in Chang’s performances, notwithstanding the reconciliation of values toward which her films strive. It invites us to consider these performances against the grain of the script, suggesting that there is more to Chang’s wholesome image than initially meets the eye. For if her films seem rather too insistent on positioning Chang within the bounds of propriety, the reason for this is apparent in their extreme dependence upon modes of cor-poreal display that push those very bounds. More than any other performer of her time, Chang was identified with new, unfamiliar musical fashions from the West as well as other parts of the world. Indeed, Mambo Girl, as her breakout vehicle, cemented her affilia-tion with not just American rock and roll but also Latin Caribbean dance and music. Halfway through the film’s first musical num-ber, Kailing stops her singing and — as a rhythmic percussive beat surges to the fore of the sound track — shimmies, shakes her hips, and throws herself into an energetic solo mambo routine. Later in the film, she dances a cha-cha to one of Chang’s most popular hits, “I Love Cha-Cha.” At direct odds with Chang’s projection of exemplary Chinese femininity is her active role in the cinematic remediation of foreign musical styles, channeling and absorbing their connotations of otherness, exoticism, and threatening sensu-ality. If Chang’s films often fail in the final instance to reconcile the contradictions in her persona, this failure is precisely where their fascination as historical texts begins. Rather than being straight-forward illustrations of liberal or progressive gender values, they demand to be viewed as instantiations of conflicting norms of gen-der identity in the postwar period. Indeed, Chang’s star persona reflects less a fixed, unidimensional ideal of Chinese womanhood

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 13

than the very incoherence of such a construct at a time when codes of feminine conduct were being radically rewritten. And in her films, the fault lines that subtend the idealized image of modern femininity acquire a particular clarity in the performance of song and dance.

The Mambo Girl and Her DoubleMambo Girl can be described as a family melodrama – cum – song-and-dance film, containing several additional scenes of musical performance that center on Kailing. By and by she makes a trau-matic discovery that shakes the foundations of her unperturbed existence in the bosom of a doting family and admiring circle of classmates. At the end of the opening dance party scene, Mr. Li (Liu Enjia) announces to the group that Kailing’s twentieth birthday is just a few days away and invites them to a celebration of the event. Later in the evening, when his wife tells him that he has misremembered the date of his daughter’s birth, the two of them consult a document from a box hidden under their bed to confirm the date. At that moment, Kailing’s little sister Bao-ling (Kitty Ting Hao) bursts into the bedroom and catches sight of the document, which is revealed to be not a certificate of birth, but an adoption certificate. The parents confess the secret and attempt to reassure the stunned Baoling, saying that she and Kai-ling are no different from natural-born siblings. When the day of the birthday party arrives, Baoling unwisely leaks the family secret to the sisters’ classmates. Their gossiping is overheard by Kailing, and she flees the party in tears.

The warm picture of the home-as-heaven constructed at the film’s beginning is thus broken apart. Against the background of comforting familiarity, a discordant sense of unhomeliness rears its head; in the midst of the birthday celebration — a ritual affirmation of modern individuality — Kailing is confronted with the unset-tling enigma of her identity and origins. She plunges into a state of doubt and process of questioning during which she turns away from her family and friends. Eventually Kailing’s self-searching drives her out of the home itself. She runs away and, with her

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

14 • Camera Obscura

adoption papers in hand, embarks upon a search for her biologi-cal mother. The quest draws Kailing into a series of spaces that are increasingly alien and removed from the realm of middle-class domesticity — the orphanage, a sanctuary for homeless children; the slum, a metonymy for the class reality held at bay from the fictive world of privileged urbanites; and lastly, the nightclub, the diametrical opposite of the home. At her first stop, the orphan-age, Kailing obtains the name — Yu Suying (Tang Ruoqing) — and address of the woman who left her there as a baby. The address leads her to a poor neighborhood, where she queries residents about Yu’s whereabouts. Kailing is disappointed to find that the woman no longer lives there, but she obtains a new clue when one of the residents tells her that Yu works at a nightclub. Kailing’s ensuing pursuit of this lead takes her through the pleasure palaces of Hong Kong nightlife.

At her last stop, the Lichi Nightclub, Kailing learns from a kindly waiter that a woman named Yu Suying works as an attendant in the ladies’ washroom. She enters, asks the woman her name, and falteringly begins, “Twenty years ago, did you turn over your child to the orphanage? I’m . . .” The two then enter into an emotionally charged and circuitous exchange. Yu denies that she ever had a child, but she unambiguously betrays the truth of their relationship in the manner of her acting and in the barely repressed interest she takes in Kailing when she asks the girl about her life and adop-tive family. The two circle each other carefully until Kailing makes a last, urgent plea — “Isn’t it you?” Yu responds with the question, “How can I possibly have a daughter like you?” Her performance convinces Kailing enough to leave the nightclub, although after she has gone, Yu confesses to the waiter that she is indeed Kailing’s mother. For her part, Kailing takes refuge at a friend’s house and ponders the conversation before finally going home, where her fam-ily anxiously awaits her. When she walks through the door and sees the concern on their faces, she cries out, “Father! Mother!” They tearfully embrace, and, rounding out the happy ending, her friends rush in and resume the interrupted birthday festivities. The film ends with a scene of singing, dancing, and youthful merriment.

In the midst of the final round of partying prompted by Kailing’s return, Yu and the waiter from the nightclub peer through

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 15

the front door of the house and catch a glimpse of these goings-on. The waiter offers to go inside to fetch Kailing, but Yu tells him, “I have no right to tell her. Those wonderful people, they deserve to be her parents. I have nothing to give her. I don’t deserve her,” and walks away in tears. In Gary Needham’s reading, this ending appro-priates the well-known concluding scene of the classic maternal melodrama Stella Dallas (dir. King Vidor, US, 1937), in which Stella (Barbara Stanwyck) watches her daughter as a distanced spectator from outside the home of the family to which she has relinquished her daughter for the girl’s own good. Likewise, in Mambo Girl view-ers witness the gaze of an “estranged lower-class mother,” Needham writes, who “watches in exclusion her daughter and her adoptive family in a happy reunion.”17 The viability of the middle-class family and the promises of modernity necessitate the sacrifice and expul-sion of the mother who hails from the milieu of the slum. After Yu’s departure, the waiter continues to watch the revelry until Kailing catches sight of him at the door and recognizes him. He makes up an excuse about passing by and overhearing the music and tells her as he leaves, “If you like dancing, you should come to our nightclub sometime.” Kailing shrugs off the odd encounter, and the after-image of maternal suffering is expunged by the upbeat swing tune and lively choreography as she dances away her worries.

Through this series of events, the elementary diegetic mys-tery of Kailing’s parentage is answered, the crisis of her identity resolved, and the threads of the story tied up. Such an account of Mambo Girl, however, is incomplete. At another narrative level, the question of who the mambo girl is and where she comes from lingers. For the enigma of birth finds another articulation in the film, one that emerges only if we shift our analytic focus away from the causal sequence of story events and toward the framing and structuring of musical performance. In this double articulation, the question of Kailing’s identity is reformulated by the film at a metadiscursive level as a question about the roots of musical spectacle itself. If the natural talents of the mambo girl warrant repeated displays of song and dance, then where do these musical gifts come from? From the very beginning of the film, Kailing’s character is individualized and defined by her community in terms of her aptitude for singing and dancing, as the title makes clear.

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

16 • Camera Obscura

When the truth about her birth is disclosed, those very traits that have drawn others to her and carved out her place in a social world become a source of self-doubt. Kailing wonders how she possesses such talents when, as she puts it, “my father can’t sing, my mother can’t dance, and even my sister can’t sing or dance?” The mark of her identity as a songstress becomes the sign of an alienating difference and otherness. The narrative poses an answer to this problem in the single clue offered to Kailing concerning the where-abouts of her birth mother: the fact that she works at a nightclub, an establishment whose existence is premised upon the entertain-ments of singing and dancing. The mambo girl’s search for her origins brings her face-to-face with the nightclub as the place of the mother and locus of the songstress’s true origins.

In postwar cinema the nightclub is commonly portrayed as “an illicit place . . . the Other (place) of the family,” in the words of Roger Garcia.18 The significance of the nightclub can be grasped in contradistinction to the home as a spatial microcosm of a social order founded upon traditional Confucian values and patriarchal authority. Garcia observes that the diametrical opposi-tion between the respectable family home and the disreputable nightclub simultaneously reinforces a familiar, stereotypical binary of female sexuality: “dutiful mothers, daughters, sisters, wives” are never to be found in nightclubs, and “the only question surround-ing the women found in them does not concern their virtue, but their price” (147). For Garcia, the confrontation between mother and daughter in Mambo Girl, constructed in a series of shot – reverse shots against a background of mirrors, exposes the spatial logic that binds the nightclub and the home in an oppositional rela-tionship. Here the nightclub emerges clearly as an “other” space, “the representation of the family’s hidden desire, the expression of its unconscious” (148). Yet Garcia’s analysis overlooks the ways in which Mambo Girl not only invokes but actively deconstructs the binaries of nightclub and home and of the virtuous woman and the fallen woman. For in entering the spaces of nightlife, Kailing is confronted with a series of musical spectacles that uncannily echo her own performances. On the nightclubs’ stages and dance

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 17

floors, viewers behold a mirroring of the song-and-dance scenes that earlier transpired in the home and the school. The first stop on Kailing’s nightclub tour is a venue where a singer belts out a jazzy dance tune from the stage as smartly dressed couples swing on a small dance floor, their moves and appearance indistinguish-able from those of Kailing’s teenage friends. Kailing’s songbird role is reprised here by the lounge singer, Miss Mona Fong (playing herself), as a neon sign behind her announces. The scene entices viewers with a glimpse into urban nightlife that lasts for the entire duration of the song, “Enjoy Yourself Tonight,” which is an incite-ment to pleasure in the same spirit as the film’s opening musical number. Viewers’ first glimpse of the nightclub comes from a long shot encompassing a view of the stage, the dance floor, and the door from which Kailing enters the venue. As she regards the per-formance with earnestly searching eyes, the camera cuts between Kailing and Mona Fong, both frontally framed in medium shots. Fong now occupies the visual and sonic spotlight, as Kailing did ear-lier in the film. The shot – reverse shot editing pattern emphasizes Kailing’s position as onlooker to this performance and the intense concentration with which she fixates on the singer (figs. 4 – 5).

Figures 4 – 5. Kailing encounters the cabaret singer Mona Fong (playing herself) while searching for her mother in Mambo Girl.

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

18 • Camera Obscura

The question hanging in the air here, posed in the syn-tax of the visual face-off between the mambo girl and the lounge singer, is whether the singer is Kailing’s mother. Concomitantly, we are invited to consider the home of the lounge singer, the nightclub, as the font of Kailing’s genetically unaccountable musi-cal talent. The question is put into words by Kailing herself at the final stop of her tour when, entering the Lichi Nightclub, she que-ries the waiter about whether a person named Yu Suying works on the premises. The waiter asks, “What sort of work does she do here?” Kailing replies, “I’m not sure what kind of work. Perhaps she sings or performs or something like that?” “Never heard of her,” the waiter says, “and it’s showtime now. Everyone is here to see Margo. Why don’t you stay and watch for a while — this way, please.” Kailing reluctantly allows herself to be directed to the side of the dance floor as the band strikes up an allegro arrangement of the jazz classic “Summertime,” enlivened by the pounding drumbeat of timbales. To this accompaniment a lone performer, the afore-mentioned Margo, makes her way onto the floor and proceeds to mesmerize the audience with a display of explosive carnal energy. Barefoot and costumed in a beaded and tasseled bikini, she shakes, spins, and thrusts her hips with suggestive abandon in a burlesque dance that draws from a mélange of Latin Caribbean elements. The performance culminates with a frenzied percussion solo dur-ing which Margo goes into high gear and drops to the floor in a none-too-subtle mimicry of sexual intercourse to the evident thrill of the nightclub clientele, which responds with bemused smiles and applause. As in the earlier nightclub scene, the camera cuts to Kailing at moments throughout the performance so that viewers watch her watching the performance (figs. 6 – 7). Her reaction sets her apart from the other patrons in the nightclub; she appears distracted rather than immersed in the spectacle of the dance, ill at ease, and, by the grand finale, quite scandalized by what she witnesses.19

At this point in Kailing’s search, the confrontation between the wholesome singing teenager and the semirespectable night-club entertainer reaches an intensive pitch as a primal encounter. Kailing’s hidden identity returns to her in the form of a danse sau-

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 19

vage, and the shadow of the fallen woman falls upon the youthful mambo girl. During such scenes of nightlife spectacle, the film’s unwinding of the narrative problem of biological origins takes a reflexive turn, directing viewers’ attention to the nightclub per-former as the mambo girl’s mother in the figurative senses of a historical precursor and tropological ancestor. The enigma of Kailing’s parentage condenses the obscured history of the postwar songstress: before the mambo girl, musical spectacle was supplied by the lounge singer and cabaret dancer, whose narrative abode was the nightclub stage. Kailing reacts by refusing this implied par-entage and turning away from the performance she witnesses, and the narrative conspires in her gesture of disavowal by defusing the tension of this confrontation in the immediately ensuing meeting with her biological mother. Yet the force of this distancing ges-ture — the conviction of Kailing’s refusal to look — is significantly undermined by the film’s presentation of the nightclub entertainer, which brazenly caters to the viewer’s desire to look. Most strik-ing here are the concessions granted to the sensuous appeal of these musical performances, which are presented in their entire real-time duration as well as staged in an exhibitionist mode that directly addresses the viewer.

The sense of exhibitionism is especially pronounced in Mar-

Figures 6 – 7. Kailing reacts to the burlesque dance performed by Margo the Z-Bomb in Mambo Girl.

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

20 • Camera Obscura

go’s dance, which is filmed so as to dramatize the self-consciousness of its corporeal display. At several points Margo acknowledges the presence of the camera by looking at and moving toward it, thereby offering the audience close-up views of her dancing body that are quite jolting in their tactile impact and intimate physicality. Her dance is undeniably Mambo Girl’s spectacular high point, and its extremely erotic tenor calls out the stakes of the film’s attempt to distance Kailing from such a choreographic exercise. Just as the mambo girl needs to be rescued from her working-class past, so also must she be delivered from the sexually charged atmosphere surrounding the nightclub performer whose vocation is to arouse the desires of her audience. The danse sauvage is the counterimage of the teenage party, flagrantly displaying all the seamy and pro-vocative elements carefully excised from the mambo girl’s image. If Kailing’s physical effusions have been drained of their libidinal overtones and channeled toward a more socially acceptable signi-fication of youthful vitality, these overtones return with renewed force in the nightclub setting, where social dancing’s associations with courtship and sexual expression come to the fore. The film thus calls attention to the mambo girl’s buried kinship with per-formers like Mona Fong and Margo in the very process of exor-cising that kinship. Musical spectacle offers a key to the mambo girl’s secret history, and, viewed against the background of these nightclub shows, she emerges with greater complexity and depth than the film’s story would otherwise grant her.

The Cinema Goes NightclubbingCountless films made both before and since Mambo Girl have gravitated toward the setting of the nightclub as a public estab-lishment for drinking, dining, and musical entertainment for a mixed-sex clientele. The frequency of the nightclub’s appear-ance in postwar Hong Kong cinema has led one commentator to observe wryly that “night clubs seem to be places where most movie characters who live in Hong Kong spend an inordinate amount of their time.”20 Often portrayed on-screen as an arena of illicit behavior, delinquency, and forbidden desire, the night-

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 21

club functions as a site for the projection of social fantasies of moral transgression and for the return of the family melodrama’s repressed libidinal impulses. But just as Mambo Girl breaks down the opposition between the home and the nightclub with its dis-closure of the secret history of the songstress, so the film also introduces a more expansive understanding of the significance of the nightclub for postwar film culture. More than ideological nodes within an imaginary landscape, nightclubs were a material and historical fixture of urban space, existing alongside cinema within a modern capitalist culture of consumption, leisure, and fashion. As many Hong Kong historians have observed, the night-club was a transplant from prewar Shanghai; like film and Man-darin pop music, it was a cultural import brought to the colony by cosmopolitan exiles. As it took root and flourished throughout the 1950s and 1960s, it gave rise to a vibrant nightlife scene of cabarets, supper clubs, and dance halls. The filmic imagination of the nightclub in this period can be traced to the art deco nightlife temples of early Shanghai cinema, which were presented as spaces of romance, glamour, and revelry as well as hedonistic excess, exploitation, and violence.

In an even more literal sense than the story intimates, the mambo girl was born in a nightclub. As Chang recounts, the initial idea for Mambo Girl came about during an evening on the town with MP&GI studio head Loke Wan Tho, who was so taken with her dancing that he suggested making a film featuring it.21 The film is inspired by and takes its name from the dance styles then sweeping the club and cabaret circuit. Its musical idiom is indebted to not only Western popular music trends and the rock and swing styles of Hollywood youth musicals but also the latest trends from the Hong Kong nightlife scene. The mambo girl’s moves originate in the glamorous, worldly, and risqué environs of the nightclub and are imbued with its color, notwithstanding the film’s attempt to recode her dances with reference to the spaces of the home and school. The rhythms and choreography composing its main attractions are direct imports from the local nightclub scene, appropriated as cine-matic spectacles. Mambo Girl catalyzed a far-reaching shift in the dance floor’s influence on screen culture, as choreography itself

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

22 • Camera Obscura

assumed a more emphatic presence in film’s musical lexicon. In the wake of Mambo Girl’s success, numerous other films attempted to reproduce its formula and harness the popular appeal of Latin Caribbean music and dance, such that the rhythms of mambo, calypso, rumba, and cha-cha quickly became common features of Mandarin cinema’s musical repertoire. And more than any of her contemporaries, Chang embodied the rebirth of the songstress as dancer. The prototype of the mambo girl set the parameters for Chang’s stardom insofar as dance became an integral element of her persona and was featured in nearly all of her films as well as emphasized in her publicity discourse. In Chang’s performances, we discover a seismograph of the process by which dance came to be recoded in its filmic remediation, emerging as a critical part of the imaginary of postwar Chinese modernity.

The conjunction of modernity, femininity, and dance recalls an earlier point in film history when the female body in choreo-graphic display emerged as a key conduit for the expression of new physical, social, and sexual freedoms. As Gaylyn Studlar argues, the dance spectacles of Hollywood silent film channeled a vision of transformed femininity “convergent with those qualities of the New Woman that disturbed social conservatives.”22 Visual representa-tions of dance on-screen and in fan magazines ushered in “a new concept of the female body in movement that suggested sensual-ity, athleticism, and sometimes even androgyny” (111). Moreover, Hong Kong cinema’s fascination with foreign dance styles finds a distant echo in the “dance Orientalism” that Studlar identifies as a distinctive feature of American silent cinema. The Scheherazades, Salomes, and Cleopatras to which Hollywood turned its sights tapped into stereotypical associations of the mysterious East with exoticism and libidinal excess while also locating these fantasies within a framework of otherness distanced from ordinary reality. In a similar fashion, Margo the Z-Bomb’s performance in Mambo Girl simultaneously fulfills the dangling promise of wild and crazy dancing made at the beginning of the film and contains these connotations within a racially marked display.23

Like many other aspects of Hollywood, dance orientalism infiltrated early Shanghai cinema. The 1931 production Two Stars in

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 23

the Milky Way (dir. Shi Dongshan, China) featured an Egyptian-style dance by its star Violet Wong, previously a well-known performer of the musical revue stage; later in the film she performs a tango in a nightclub with her male costar Jin Yan. The film is indicative of the “dance madness,” or wu kuang, of Jazz Age Shanghai. Many other films of the era flaunted new dance styles on the stage and the dance floor.24 But in this milieu, dancing as a social practice stood out as a Western import with no close equivalent in Chinese culture. For this reason, it was both deprecated by some as a decadent foreign practice that incited inappropriate interactions between the sexes and embraced by others as a glamorous and thrilling expression of modernity. The dancing world of the postwar era can be seen as a transplant of prewar nightlife culture, the continuation of a longer process of popularizing dance — as is suggested in press descriptions of Chang’s mambo girl as an “ultra-modern flapper.”25 From Shanghai to Hong Kong, dance persisted as a fashionable pastime interpolated within a modern style of living that was built upon practices of consumption and leisure and the structured division of work and play.

In the postwar decades, however, the popularization of dance reached a new threshold; the values attached to dance irreversibly shifted with its institutionalization as an object of mass consumption. Concomitant with its mainstreaming, dance lost its outré tinge. To be sure, its long-standing sexual connotations did not entirely subside, as Margo’s performance in Mambo Girl attests. But they lost their power to overdetermine social perception. The pleasures and physicality of dancing were no longer defined solely with reference to eroticism and hedonistic indulgence but were reconceptualized according to a wider set of concepts: playfulness, artistry and creative expression, technique, physical fitness, and recreation. Filmic remediations of dance played a critical role in this process of recoding and rehabilitation. For instance, alongside Mambo Girl’s spatial dislocation of the dance floor to the family domicile, we can also consider the parallel the film draws between dancing and more anodyne forms of exercise and physical fitness. As Yeh observes, the film sets out to legitimize dance as a “healthy, athletic, and kinetic art form.”26 The “I Love Cha-Cha” number

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

24 • Camera Obscura

that comes later in the film takes place in a high school gymnasium, and the song’s lyrics include the lines

We merrily go to school togetherWe happily exercise together. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .You have a clear and sharp mindYou have a fit and agile bodySo listen closely to the beat.

The same equation can be seen at work in print repre-sentations of Chang, which frequently portray her in the dance studio, another setting consecrated for physical training. Indeed, the marked resonance between on-screen and offscreen construc-tions of Chang as mambo girl points to the instrumentality of print media in reshaping popular perceptions of dance. Mr. Li’s defense in Mambo Girl of the artistic merit of his daughter’s musical proclivi-ties resurfaces in numerous promotional articles accentuating the artistry and technical rigor in Chang’s dancing. Time and again she is billed as an “accomplished danseuse,” her films are discussed as displays of the “art” and “beauty” of choreographic expression, and her performances are promoted as the products of assidu-ous practice and technical refinement.27 In journalistic accounts of the particular demands made by song-and-dance films upon their performers, dance crosses the line between work and play. For instance, a production report on Because of Her (dir. Evan Yang [Yi Wen] and Wong Tin-lam [Wang Tianlin], Hong Kong, 1963), illustrated by images of Chang rehearsing in the studio with her dance coach and fellow actors, emphasizes the “intense behind-the-scenes work of choreographic training” involved in the making of this musical revue. The performance of dance requires artistic-technical expertise, which can only be acquired by diligent prac-tice. To prepare for her role, the article notes, Chang had absorbed herself in a grueling rehearsal schedule for three months.28 The emphasis on the actress’s rigorous preparation for various roles runs throughout her publicity materials. Across these accounts, dance — and musical training in general — emerges as the center-

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 25

piece of a disciplinary regime of labor and physical conditioning, signaling Chang’s professionalism and work ethic. These values intercept the dubious moral values traditionally assigned to dance and thus pave the way for its cultural legitimization as a form of work. What makes this flapper ultramodern is determined by the demands of modern industry as much as by up-to-the-minute cul-tural trends.

Untimely MelodiesThe ambivalent identity of the mambo girl would continue to haunt Chang’s star image as a structuring tension. As the key fig-ure through which new musical styles were woven into the sounds and images of Hong Kong cinema, Chang embodied the fluctuat-ing meanings of song and dance in postwar Chinese modernity. The five songs from her pop repertoire selected for The Hole call attention to the degree to which Chang’s stardom was consti-tuted around the allure of the foreign and exotic. These dimen-sions come to the fore in “Oh Calypso,” a paean to the pleasures of Afro-Caribbean dance that Chang originally sang in Air Host-ess, where her character’s occupation as an airline attendant pro-vides a narrative pretext for several location shoots throughout Southeast Asia. Chang’s performance of the song in a Singapore nightclub links the pleasures of musical border crossing with the newly available experience of air travel, attesting to the transna-tional imaginary of postwar Hong Kong cinema. Two of the other numbers in The Hole are Chang’s covers of American pop hits: “Achoo-Cha Cha,” originally released by the trio the McGuire Sisters, which opens with the sound of a sneeze and the declara-tion “Gesundheit!,” and the rock-and-roll song “I Want You to Be My Baby.” Chang’s rendition of the latter incorporates most of the original English lyrics, sung at a rollicking pace, thus showing off her linguistic fluency and further rounding out the cosmopolitan musicianship that can be traced in her body of work. Throughout the course of her career, the cultural scope of her performances would extend even further and in some unlikely directions: in The Wild, Wild Rose (dir. Wong Tin-lam [Wang Tianlin], Hong Kong,

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

26 • Camera Obscura

1960), Chang sings the habanera from Georges Bizet’s opera Car-men with Mandarin lyrics and set to a Latin percussion beat, and she dons a kimono for a Mandarin rendition of “Un bel dì” from Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly.

Chang’s stardom reflects the distinctive character of a pop culture industry insatiable in its absorption of international musi-cal styles. The examples described above point to the songstress’s role as a mediator of cultural difference and her ability to make such difference translatable, consumable, and pleasurable for mass audiences. But as Mambo Girl suggests, the work of domesticating what seemed unfamiliar and new and bringing it back into the fold of the familiar was never completely successful. The songstress also embodies the remainder of this incomplete translational process; traces of otherness continue to shadow her performances, despite the films’ best efforts to code them according to socially acceptable values. In Mambo Girl and other musical pictures of its time, the song-and-dance interludes become conduits for meanings that run counter to the film’s more overtly didactic content. With The Hole, Tsai Ming-liang invites us to listen for these meanings in Chang’s songs, incorporating them into the film’s sound track and narrative spaces while leaving their relation to the plot deliberately opaque. The shock of their strangeness is reactivated for the viewer with each jarring transition from narrative to number. Chang’s voice, lip-synched with calculated imperfection by actress Yang Kuei-mei, remains curiously detached from the image and eludes the attempts of the performing body to visually contain it. Slipping free from the synchresis of sound and image and resisting narrative determinations of meaning, the singing voice makes viewers aware of another presence hovering at the edges of the film.

By referencing Chang’s songs in this manner, The Hole pin-points the crux of the fascination they continue to exert across the reaches of time. Similar strategies appear in other recent Chinese-language films that invoke the figure of the songstress as an avatar of history. For instance, In the Mood for Love (dir. Wong Kar-wai, Hong Kong, 2000) summons the familiar voice of Zhou Xuan, one of the most beloved singers of 1930s Shanghai, as an acousmatic presence. At one point, the characters listen to a radio broadcast of Zhou singing her classic hit “The Blooming Years,” another song

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 27

that originally appeared in a film. The Chinese title of Wong Kar-wai’s film in fact takes its name from the song, which expresses the homesickness of the exile who longs for the best years of her life. Zhou’s lyrics channel the dominant mood of the film as a wistful remembrance of a Hong Kong that no longer exists, although the voice is not anchored to a visible body and instead floats free in the electromagnetic ether. In Rouge (dir. Stanley Kwan, Hong Kong, 1987), viewers encounter a songstress who is quite literally a ghost: a 1930s courtesan who returns from the afterworld to take care of unfinished business. Cast in the role of the ghost is acclaimed actress and Cantopop megastar Anita Mui, bearing out the contin-ued legacy of crossover stars like Chang in late twentieth-century Hong Kong popular culture. Across these contemporary invoca-tions of the songstress, what becomes apparent is her magnetism as a locus of cultural memory. The phantomlike register in which these works bring the songstress back to life speaks to the ways in which music can live beyond images and the different ways in which songs and films make claims upon an audience’s memory. The affective power of the songstress’s songs resides precisely in the sense of something other, which remains unheard and therefore commands repeated listening.

Notes

1. For a detailed discussion of The Hole and its musical references, see Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh and Darrell William Davis, “Camping Out with Tsai Ming-liang,” in Taiwan Film Directors: A Treasure Island (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 217 – 48; and Jean Ma, “Delayed Voices: Intertextuality, Music, and Gender in The Hole,” Journal of Chinese Cinemas 5, no. 2 (2011): 123 – 39.

2. Poshek Fu, Between Shanghai and Hong Kong: The Politics of Chinese Cinemas (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003).

3. Poshek Fu, introduction to China Forever: The Shaw Brothers and Diasporic Cinema, ed. Poshek Fu (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 6.

4. Exceptions include two important surveys of the history of Hong Kong cinema: Stephen Teo, Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions (London: British Film Institute, 1997); and Law

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

28 • Camera Obscura

Kar and Frank Bren, Hong Kong Cinema: A Cross-Cultural View (Oxford: Scarecrow, 2004). See also Yingchi Chu, Hong Kong Cinema: Coloniser, Motherland, and Self (New York: Routledge, 2003); and Fu, China Forever.

5. An example in this vein is David Bordwell, Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

6. Wong Kee-chee, “A Song in Every Film,” Hong Kong Cinema Survey, 1946 – 1968 (Hong Kong: Urban Council, 1979), 29 – 32. A more literal translation of his title phrase is “no film without a song.”

7. Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh, “China,” in The International Film Musical, ed. Corey K. Creekmur and Linda Y. Mokdad (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), 173.

8. Popular music historian Szu-Wei Chen writes,

In traditional Chinese operas or folk songs, both genders participate in singing, but most of the historical recordings of Shanghai popular songs were sung by female performers. Male performers often served as characters who were secondary in importance to the main female role in duets and choruses, or as vocalists for backing harmonies. Though some male singers also made their own recordings, such as Yao Min, Yan Hua, and classically trained Sheng Jialun and Huang Feiran, overall, they left behind considerably fewer works than their female counterparts.

Szu-Wei Chen, “The Rise and Generic Features of Shanghai Popular Songs in the 1930s and 1940s,” Popular Music 24, no. 1 (2005): 116.

9. Zhang Zhen, An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896 – 1937 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 310.

10. Miriam Bratu Hansen, “Fallen Women, Rising Stars, New Horizons: Shanghai Silent Film as Vernacular Modernism,” Film Quarterly 54, no. 1 (2000): 15.

11. On this topic, see Catherine Russell, “New Women of the Silent Screen: China, Japan, Hollywood,” in “New Women of the Silent Screen: China, Japan, Hollywood,” ed. Catherine Russell, special issue, Camera Obscura, no. 60 (2005): 1 – 13.

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 29

12. Sam Ho, “The Songstress, the Farmer’s Daughter, the Mambo Girl, and the Songstress Again,” in Mandarin Films and Popular Songs: 40s – 60s, ed. Law Kar (Hong Kong: Urban Council, 1993), 63, 64.

13. The toy motif calls to mind a silent-era Shanghai film, Little Toys (dir. Sun Yu, 1933), in which Ruan Lingyu plays a traditional toymaker and the fate of the nation is represented by toys and children. For an analysis of this film, see Andrew F. Jones, Developmental Fairy Tales: Evolutionary Thinking and Modern Chinese Culture (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 126 – 46.

14. David E. James, “Rock ’n’ Film: Generic Permutations in Three Feature Films from 1964,” Grey Room, no. 49 (2012): 10.

15. James writes, “In the 1950s, when films about rock ’n’ roll were made from within the culture industries, their task was to disclaim the music’s aesthetic and social menace and its associations with delinquent teenage working-class subcultures by legitimating the music as commodity entertainment assimilable to the existing cultural order within the hegemony of capitalist culture.” James, “Rock ’n’ Film,” 26.

16. Mary Wong, “Women Who Cross Borders: MP&GI’s Modernity Programme,” in The Cathay Story, ed. Wong Ain-ling (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive, 2002), 85 – 86.

17. Gary Needham, “Fashioning Modernity: Hollywood and the Hong Kong Musical, 1957 – 64,” in East Asian Cinemas: Exploring Transnational Connections on Film, ed. Leon Hunt and Wing-Fai Leung (New York: Tauris, 2008), 46. Building on Needham’s observation, we can also consider the theme of maternal sacrifice that runs throughout the silent era of Chinese cinema, inflecting notable productions such as Love and Duty (dir. Bu Wancang, 1931), Little Toys, and The Goddess (dir. Wu Yonggang, 1934). In all of these films, Ruan Lingyu is cast as a loving mother who, like Kailing’s biological mother, must be removed as an obstacle to her child’s upward mobility. Love and Duty and Little Toys are particularly significant intertexts for Mambo Girl insofar as these films stage an emotionally wrenching reunion between a mother and a child who no longer recognizes her.

18. Roger Garcia, “The Illicit Place,” in The Seventh Hong Kong International Film Festival Publication (Hong Kong: Urban Council, 1983), 147.

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

30 • Camera Obscura

19. The performance consists of footage of an actual cabaret act filmed on location in one of Hong Kong’s most famous nightclubs. The bikini-clad dancer is Lolinda Raquel, better known by her stage name, “Margo the Z-Bomb,” who, at the time of Mambo Girl’s production, was a sensation on the cabaret circuit in Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and the US.

20. I. C. Jarvie, Window on Hong Kong: A Sociological Study of the Hong Kong Film Industry and Its Audience (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 1977), 92.

21. Grace Chang, unpublished interview by Shu Kei, cited in Shu Kei, “Notes on MP&GI,” in Wong, Cathay Story, 43. Another possible inspiration for Mambo Girl is the 1954 Italian film Mambo (dir. Robert Rossen), starring Silvana Mangano as a professional dancer. The film features several performances of Afro-Caribbean dance by the Katherine Dunham Dance Company. Chang has recalled seeing Mambo prior to the filming of Mambo Girl, and the two films’ credit sequences and opening dance scenes display some similarities. See “One Big Happy Family: Grace Chang’s Cathay Story,” interview by Donna Chu, in Wong, Cathay Story, 192.

22. Gaylyn Studlar, “ ‘Out-Salomeing Salome’: Dance, the New Woman, and Fan Magazine Orientalism,” in Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film, ed. Matthew Bernstein and Gaylyn Studlar (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 106.

23. In bringing together female sexuality, racial difference, and the spectacular climax of the dance, Margo’s performance calls to mind a global history of the danse sauvage by performers from Josephine Baker to Anna May Wong.

24. For a history of the institutions that supported this dance madness — cabarets, dance halls, and ballrooms — see Andrew David Field, Shanghai’s Dancing World: Cabaret Culture and Urban Politics, 1919 – 1954 (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2010).

25. “Ge Lan wuzi” [Grace in her mambo poses], International Screen, no. 14 (1956): 11.

26. Yeh, “China,” 178.

27. See, for example, “Zhihui zhi xing — Ge Lan” [Grace Chang is accomplished danseuse], International Screen, no. 40 (1959): 12 – 13.

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press

Hong Kong Mambo • 31

28. “Ge Lan mai yi chang dagu” [Grace Chang in Story of Three Loves], International Screen, no. 90 (1963): 42.

Jean Ma is an associate professor in the Department of Art and Art History at Stanford University, where she teaches in the Film and Media Studies Program. She is the author of Melancholy Drift: Marking Time in Chinese Cinema (Hong Kong University Press, 2010) and coeditor of Still Moving: Between Cinema and Photography (Duke University Press, 2008) and “Sound and Music,” a special issue of the Journal of Chinese Cinemas. Her book on singing women in Chinese cinema is forthcoming from Duke University Press.

Figure 8. Lolinda Raquel, or Margo the Z-Bomb, photographed by Harry Jay. Courtesy of the Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre Melbourne

Camera Obscura

Published by Duke University Press