Geographies of Housing Finance: The Mortgage Market in Milan, Italy

Transcript of Geographies of Housing Finance: The Mortgage Market in Milan, Italy

Geographies of Housing Finance:The Mortgage Market in Milan, Italy

MANUEL B. AALBERS

ABSTRACT The geography of financial exclusion has mainly focused on exclusion from retail

banking. Alternatively, and following the work of David Harvey, this paper presents a geography

of access to and exclusion from home mortgage finance. The case of Milan shows that capital

switching to the built environment is partly a sign of economic crisis and partly a sign of the

intrinsic opportunities that the built environment provides. A major factor in both is the deregu-

lation of the mortgage market that has enabled the loosening of historically stringent lending

criteria, leading to a tremendous growth of the mortgage market, while leaving the co-evolution of

family and home ownership intact. In addition, capital switches within sectors of the economy and

between places. In Milan, once “unattractive” but currently gentrified nineteenth-century districts

underwent cycles of devalorisation and revalorisation. Even though access to mortgages has

increased throughout Milan, geographical disparities in mortgage lending persist: at present,

yellowlining (differential access, based on less favourable terms) is common in parts of the

Milanese periphery. The creation of boundaries makes the realisation of class-monopoly rent

possible; while the subsequent redrawing of these boundaries creates new submarkets in which

surplus value can be extracted. Based on the Milan case, one cannot explain the timing and

geography of formation and reformation of submarkets in other cities, but it helps us to see how

Harvey’s abstract ideas of class-monopoly rent, submarket creation, and capital switching take

place in the real world.

Manuel B. Aalbers is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Urban Planning at Columbia

University, NewYork. His e-mail address is: [email protected]. This paper was written while the

author was a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam (The Netherlands) and an RTN-fellow at

the University of Milan–Bicocca (Italy). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the session

“European Financial Geographies: Spaces, Flows, and Networks,” RGS-IBG Annual International

Conference, Royal Geographical Society, London, 31 August–2 September 2005. I gratefully acknowl-

edge financial support from the European Commission-funded RTN programme “Urban Europe,”

which enabled me to stay at the Università degli Studi di Milano–Bicocca. I would like to thank Enzo

Mingione, Elizabeth Esteves, and the Dipartimento di Sociologia e Ricerca Sociale for their hospitality

and help, Iwona Wozniakowska for making the map, the referees for very constructive comments, and

Serena Vicari, Francesca Zajczyk, Enzo Mingione, Mario Boffi, Elizabeth Esteves, Alberto Violante,

Simone Scarpa (all at Milano-Bicocca), Antonio Tosi (at Politecnico di Milano), Ugo Rossi (at the

University of Naples “L’Orientale”), Samuel Mößner (at Kiel University), Enrico Gualini, Sako

Musterd, and Robert Kloosterman (all at the University of Amsterdam) for helpful suggestions. The

usual disclaimer applies.

Growth and ChangeVol. 38 No. 2 (June 2007), pp. 174–199

Submitted January 2006; revised June 2006; accepted October 2006.© 2007 Blackwell Publishing, 350 Main Street, Malden MA 02148 US and 9600Garsington Road, Oxford OX4, 2DQ, UK.

Introduction: From Harvey to Financial Exclusion inMortgage Markets

T he contemporary literature on the geography of finance is rooted in the work of DavidHarvey. Harvey is spatialising Marx’s contributions (Sheppard 2004) and, following

Marx, Harvey gives centre stage to financial markets. In Marx’s view, financial marketsenable capital to flow from less profitable to more profitable sectors of the economy;Harvey speaks of “capital switching” when capital (investment) flows from one sector tothe other. Harvey adds that these “temporal” fixes can only temporarily replace cycles ofboom and bust, but not make them disappear. Harvey then identifies four types of spatialfixes. In one of them, he focuses on the urban land market and the built environment. Heargues that for financial institutions, the built environment is seen as an asset in whichmoney can be invested and disinvested by directing capital to the highest and best uses, andby withdrawing and subsequently redirecting capital from low payoff ’s to potentiallyhigher ones (Harvey 1982, 1985). Capital switching then entails the flow of capital from theprimary circuit (production, manufacturing, industrial sector) to the secondary circuit. Thesecondary circuit comprises the built environment for production (e.g., infrastructure) andfor consumption (e.g., housing). Harvey also identifies a tertiary circuit, the circuit of socialinfrastructure identified by investment in technology, science, conditions of employees,health, and education (Harvey 1982, 1985). Switching from the primary to the secondary(or third) circuit takes place when there is a surplus of capital in the primary circuit andsigns of over-accumulation emerge in the primary circuit. In other words, capital switchingis a strategy to prevent a crisis, but because of the inherent contradictions of capitalism,investment in the secondary circuit will only delay, not take away, the crisis. Moreover,because investments in the built environment are generally long-term investments becauseof the nature of the built environment, there are tendencies to over-accumulate and tounder-invest, resulting in a cyclical model of investment in the built environment. Inaddition, the resulting “spatial fix,” while trying to resolve the internal contradictions ofcapitalism, “transfers its contradictions to a wider sphere and gives them greater latitude”(Harvey 1985:60).

Even though Harvey stresses capital switching between the primary and secondarycircuits, capital not only switches between different sectors of the economy but also withinsectors of the economy, between forms of property, and between places (geographicalcapital switching) (Haila 1991:355; Harvey 1985:13; King 1989a:445, 1989b) and ondifferent scales—from one neighbourhood to another, from central city to suburbs, fromperiphery to “prime city,” or from one country to another—in order to exploit unevendevelopment. The formation of submarkets in the built environment facilitates this processby creating a differentiated rate of return, which is necessary for the realisation of class-monopoly rent. Class-monopoly rent arises “because there exists a class of owners of‘resource units’—the land and the relatively permanent improvements incorporated init—who are willing to release the units under their command only if they receive a positivereturn above some arbitrary level” (Harvey 1985:64). Both appreciation and devaluation of

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 175

prices are part of this logic, but “in so doing, capitalists support differentiations thatnecessarily act as barriers to individual mobility” (Harvey 1982:384), as embodied, forexample, in redlining practices. The formation of submarkets and the dynamics of, andbetween, the different submarkets are therefore necessary to extract profits through the builtenvironment; “The class-monopoly rent gained in one submarket is not independent of itsrealization elsewhere” (Harvey 1985:81). In the short run, the boundaries between sub-markets need to be relatively fixed to ensure the creation of class-monopoly rent, but in thelong run, relatively fluid to enable the future creation of class-monopoly rents extractedthrough geographical capital switching. Put differently, the built environment is shaped tomeet the requirements of capital accumulation. As a result, financial institutions have asignificant role in restructuring urban neighbourhoods, in residential differentiation, and in(re-) creating housing submarkets (Harvey 1985; see also King 1987). The importantconclusion of this short summary of a small part of Harvey’s work is that “cities, likecapitalism, undergo cycles of construction and devalorisation, and urban spatial restruc-turing” (Sheppard 2004:474). Although Harvey’s primary focus is on capital switchingbetween different circuits and, only to a lesser extent, on capital switching between differentplaces within the secondary circuit, this paper focuses on both types of capital switching.

One of the things Harvey showed in his more empirical-oriented work was that bankswere redlining inner city areas; i.e., banks did not grant mortgages for home purchase incertain parts of the city. Contrary to the beliefs of neoclassical economics, Harvey arguedthat geographical variations in mortgage lending are not merely a reflection of underlyingdemand-side variations because there are intrinsic contradictions in the structure of rela-tions between different agents as well as between the individual agent and the structure ofcapital; one example of this is that banks have spatially selective practices of creditprovision that cannot be explained sufficiently by the differential demand for credit. Thisresults in, or better, reinforces, existing uneven geographies, but the existing geographies ofuneven development do, of course, also influence the geography of mortgage finance andthe segmentation of urban mortgage markets (Harvey 1985; Harvey and Chatterjee 1974).Although this may sound like a downward spiral, Harvey is quick to admit that the structurecan be transformed by the ebb and flow of market forces, the operations of speculators andreal estate agents, the changing potential for home ownership, the changing profitability oflandlordism, the pressures emanating from community action, the interventions and dis-ruptions brought about by changing governmental and institutional policies, and the like:“It is this process of transformation of and within a structure that must be the focus forunderstanding residential differentiation” (Harvey and Chatterjee 1974:25).

Harvey’s analysis is without doubt a useful starting point for analysing the geographyof housing finance, but we should be careful in taking his argument too far by providing toolittle room for the contingency of urban development and the role of agents that act withinthe structure of the real estate industry. Urban development is no neutral and certainly nonatural development but is steered by agents who institutionalise certain developments,regulations and “rules of thumb.” These agents exercise power on existing structures, butthese existing structures, in return, are partly shaped by previous actions of these agents

176 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

(cf. Bhaskar 1979; Giddens 1984; Harvey 1985; Smith 1996; Stuart 2003; see also Aalbers2006a). In addition, Harvey has been criticised for arguing that real estate investment is a“kind of last-ditch hope for finding productive uses for rapidly overaccumulating capital”(Harvey 1985:20). His critics have argued that the built environment is an investmentchannel in its own right (Beauregard 1994; Charney 2001; Fainstein 2001; Feagin 1987).Investments in the secondary circuit are not made because there are no opportunities in theprimary circuit but because the secondary circuit possesses an intrinsic dynamic thatattracts investment rather than being externally driven by capital switching from theprimary to the secondary circuit (Haila 1991). Investment will not necessarily occur as aresult of a crisis in the first circuit and is primarily switched to equalise the rate of profitbetween sectors (Saunders 1981:230), and investment in the built environment is notnecessarily a last resort but generally competes for financing in the general capital market;actors in financial markets move capital from low-yielding products or places to higher-yielding products or places (Leitner 1994). Therefore, building booms are not necessarilysigns of economic crisis, as Harvey has argued, but may actually reflect what they seem tobe: signs of economic health. The challenge of course is to distinguish the building boomas a switching crisis from the building boom as economic health. A related point of critiquerelates to the Marxist idea of the inevitable global crisis. Because economic cycles indifferent places, despite increasing globalisation pressures, are not congruent, true globaland total crises are rare or hold off completely. Apparently, capitalism is more flexible thanMarxists have predicted.

The work on “financial exclusion” builds upon (but also goes beyond) Harvey’s analy-sis. Following Harvey, the literature on financial exclusion has investigated the relationshipbetween financial crises and the spatiality of the financial sector:

In response to the emergence of financial crises, the financial services industry has been revealed torespond by abandoning fixed and variable capital investments in “risky” areas and to relocate orre-concentrate activities within what are perceived to be “safer” areas. Such processes of financialabandonment and financial exclusion have occurred at a variety of spatial scales over the past 20 yearsor so, ranging from the mass closure of international bank branches in developing countries followingthe Less Developed Countries debt crisis of the 1980s (Corbridge 1993), to the extensive bank branchclosure programmes undertaken within economies such as the US and the UK in the 1990s (Dymskiand Veitch 1996; Leyshon and Thrift 1995; Willis, Marshall, and Richardson 2001). (Leyshon2004:463–464)

The geography of financial exclusion has so far mainly focused on access to, and exclusionfrom, retail banking. Access to, and exclusion from, home mortgage finance has rarely beenconsidered an issue of geographical interest—at least within Europe. In the U.S., there ismuch more research on these issues, but its geographical analysis is often lacking ormisguided (see Aalbers 2005a; cf. Wyly, Atia, and Hammel 2004).

Another tradition that builds upon Harvey’s analysis, but that does not refer systemati-cally to his work, is the literature on discrimination in mortgage markets. In a sea ofeconomists and regional scientists working on this topic, there are a small number ofgeographers who bring Harvey back into the literature on mortgage markets. The work

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 177

of Wyly and his colleagues (Wyly 2002; Wyly, Atia, and Hammel 2004; Wyly and Hollo-way 1999) is a case in point. Wyly and his colleagues show how the mortgage market in theU.S. has changed and how old inequalities have been replaced or restructured by new ones:

The comparative simplicity of redlining has been replaced by a more complex and stratified form ofgreenlining, as the institutional structure of lending evolves to partition borrowers and neighborhoodsin even more accurate but polarizing ways. Although consumer decisions and other demand-sideprocesses are important, we contend that they are not enough to explain new flows of mortgage credit:The restructuring of financial services plays a fundamental, autonomous role. (Wyly, Atia, andHammel 2004:636–637)

Thus, flows of capital investment privilege those already privileged, but it is too easy to saythat those already socially excluded become financially excluded. Indeed, they may beincluded and lured into loans they are very unlikely to be able to pay off (see also Squires2004).

OverviewThis paper focuses on uneven geographical conditions in the mortgage market of the

Milan region, i.e., on exclusion from, or less favourable conditions for, mortgage loans,based on geographical differences. The paper follows research on the same topic in theDutch cities of Amsterdam, Arnhem, Rotterdam, and The Hague (Aalbers 2003, 2005a,2005b, 2007), and is part of the same research programme. The point of this research is notonly to uncover the lines that banks draw between what they see as profitable and unprof-itable investments, but also to establish how, where, and why these lines are drawn, andwhat the consequences are of drawing these lines—in this case in the metropolitan area ofMilan, Italy. The focus is on the spatial patterns of banks’ mortgage loan policies ratherthan on the individual components or on the mortgage loan policies of other agents. Theaim is not to map the neighbourhoods that receive full loans, those that receive loans underuneven conditions, and those that receive no loans at all; the aim is to show why certainareas are faced with less favourable conditions than other areas. Mapping the exact bordersmay be useful, but this was not possible within this exploratory study of geographicaldisparities in mortgage finance in Milan.

Milan is a good place to study these patterns because the Italian mortgage market isdeveloping rapidly and because Milan, as the country’s economic capital, is the placewhere these changes come down first; and the larger metropolitan area is perhaps the mostdynamic one in Italy with new developments, restructuring of older areas, and increasingand decreasing popularity of different city areas. Compared with northern American andnorth-western European mortgage markets, the Italian mortgage market may be quitedifferent, but the recent developments in the Italian mortgage market will be more similarto those in other southern European countries, eastern European countries, and perhapsalso Asian and Latin American countries. All of these countries have mortgage markets thatdeveloped much later than the U.S. and north-western Europe, but most of these countrieshave also witnessed a recent expansion of their mortgage markets. Milan, as an economiccapital, is at the forefront of these changes.

178 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

The next two sections of this paper will discuss the concepts of greenlining, yellowlin-ing, and redlining and will lay out the research approach followed in this study. Subsequentsections will discuss the Italian mortgage market and recent changes in this market, andintroduce the residential geography of Milan. Then, the most empirical part of this paperwill show and elucidate patterns of geographical selectivity in the Milanese home mortgagemarket. Finally, a conclusion will be offered that recognises that the geography of housingfinance is not a straightforward one, but emphasises the dynamics of differential patterns ofmortgage finance and their relation to capital switching.

Greenlining, Yellowlining, and RedliningThe two extremes of geographical disparities are, on the one hand, areas where full

mortgages (100 percent loan-to-value) are granted on advantageous conditions (greenlin-ing), and on the other hand, areas where no mortgages are granted whatsoever at all(redlining). Actual situations will often be located somewhere between the two poles of thisdichotomy (yellowlining). Greenlining can be defined as the provision of mortgage loansunder normal, advantageous conditions; it constitutes the provision of loans to areas inwhich mortgage lenders are eager to provide mortgage loans because the area is consideredlow risk (of course, loan applications can still be rejected because the lender considerseither the collateral [the property] or the applicant high risk). Redlining can be defined asthe rejection of mortgage loan applications solely based on place-based factors; that is,lenders consider certain areas high risk, which implies that even low-risk applicants wouldbe rejected. Some authors have included disadvantageous loan conditions based on place-based factors in their definition of redlining, but in this paper, we use the term yellowliningfor such conditions. Yellowlining includes higher down payment requirements and higherinterest rates, if these are based on place-based factors; for example, if lenders normallycharge a 5 percent interest rate, but raise it to 8 percent only in certain neighbourhoods,these neighbourhoods can be considered yellowlined. Thus, redlining, yellowlining, andgreenlining do not refer to the total volume of credit supplied to neighbourhoods, but tospatial variations in terms of which credit is (not) offered.

It is important to stress that lenders typically use different measures to assess a loanapplication. First, lenders evaluate the borrower’s risk and return profile. Lenders collectdata not only on the income level and income source of an applicant, but also of her/hissocial status and how s/he has handled past loan obligations. Second, the lender assesses thevalue of the collateral, the property that the applicant wants to buy with her/his mortgageloan; this also functions as a safeguard for the lender, that is, the lender can take possessionof the collateral in case the borrower repeatedly defaults in her/his payments. Therefore, thevalue of the collateral is essential in assessing a mortgage loan application. The value of thecollateral depends on many factors, including size, maintenance, and location. Mortgagelenders often use credit scoring systems to integrate the assessment of these first two factors(Aalbers 2005c). In addition, location can also be included in the loan application processas a third independent factor. Even though location is already included in the assessment ofthe collateral, collateral assessments are usually included in credit scoring assessment of

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 179

the borrower, while location as an independent factor is not. For example, a “bad” locationmay not only lead to a lower assessed value of the collateral and therefore to a lower loan(second factor), but a “bad” location may also be taken separately to exclude a borrowerfrom a loan purely based on location (redlining) and not on the assessed value of thecollateral or on the risk that applicant represents (third factor).

In addition to these three factors, lenders also make an assessment of the broadermacroeconomic and regulatory climate. Economic recessions may, for instance, lead tomore caution on the lenders’ side and may even increase the likeliness of redlining andyellowlining practices (see also Aalbers 2005b): “The purchase of consumption fund items[like housing] via mortgages and other forms of consumer credit is sensitive to theavailability of money” (Harvey 1982:231). Capital switching from the primary tothe secondary circuit of capital takes shape within these macroeconomic processes;capital switching between places can also take place in the third factor of assessing loanapplications.

If capital switching refers to switches in mortgage funding between neighbourhoods, itis more dependent on the shifting boundaries between submarkets than on the generaleconomic climate. Capital switching between circuits, on the other hand, is much moreinfluenced by global processes, such as financial globalisation and the ebb and flow offinancial markets, next to the national economic climate and national regulatory changes.In the real world, both processes will often come together. For example, global financialmarkets may increase the flow into the secondary capital and national regulatory changesmay make investment in the built environment more attractive; one of the results may bethat neighbourhoods formerly redlined or yellowlined now become greenlined. Alterna-tively, the expanded mortgage market creates new forms of risk when economic conditionschange, such that lenders suddenly find themselves overexposed and, therefore, make riskassessment and the exclusion of high-risk neighbourhoods imperative, resulting in theimplementation of redlining or yellowlining practices.

Research ApproachThe objective of the larger study of which this paper is part, is to understand the mix of

general and specific factors that create redlining, yellowlining, and greenlining in differentcontexts (cf. Fainstein 2001:26). Just like other processes of urban (re-) structuring, redlin-ing, yellowlining, and greenlining are part of the differentiation of geographical space atthe urban level. However, although these lines are only visible at the urban level, they areconstituted at the intersection of several spatial levels: local, urban, regional, national, andglobal. Redlining, yellowlining, and greenlining are not visible at most of these levels; yet,they are constituted in and through these spatial scales. By explicitly focusing on thedifferent spatial levels through which these lines are shaped, this study tries to explain andunderstand redlining. In order to come to a fuller understanding and a better explanation,it is necessary to combine broad descriptive and theoretical generalisations or abstractionswith detailed studies of the particular, whether these are local or sectoral case studies(Massey 1984; Sayer 1985). This paper presents one such empirical study within a larger

180 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

research programme. This study uses a literature review in order to map general develop-ments in the mortgage market in Italy and urban developments in the city of Milan, andinterviews to map more specific geographical patterns in the mortgage market of Milan.

This paper makes use of semi-structured, in-depth interviews with sixteen real estateagents, five bank managers, and four other specialists in Milan and nearby municipalities.Interviewees were partly selected at random, partly through the snowball method, and in alater phase of the project based on their geographical work area. Bank managers of allleading banks in general, and in the mortgage market in specific, were approached, butseveral declined to be interviewed. There were fewer real estate agents that declined to beinterviewed. Among the real estate agents were representatives of all the major real estateagent franchise companies that are active in the Milan region. In addition, newspaperarticles, research reports, bank documents, real estate guides, and advertisements werecollected and analysed. Another possibility would have been to include households thatapplied for a mortgage loan, but because they often miss specific knowledge of the marketstructure and may not know why their loan application has been approved or denied, or whyit has been priced higher or was limited in loan amount, this exploratory study has favouredinterviews with bank professionals and professional intermediaries over “occasionalmarket actors” like households.

Language was another important consideration. While in some countries, for example,in The Netherlands, it would be possible to conduct a large number of interviews in anotherlanguage than the national one (i.e., if one interviews moderately or highly educatedpeople), I realised that this would hardly be possible in Italy, and I studied Italian for acouple of months in order to acquire a basic command of the language. In fact, this turnedout to be essential. Nevertheless, because a basic command does not guarantee full under-standing, or even less, full speaking capabilities, interviews often took place in Italianmixed with some English. There were also interviews where the basic questions were askedin Italian, while follow-up questions were asked in English. The ability to do, so of course,also depended on the interviewee. So, it was also possible that I talked Italian mixed withsome English, while the interviewer talked English mixed with some Italian. One interviewwas conducted in German, again with the use of some Italian and English “on the side.”Certain concepts were so Italian that translating them to English would only blur things; onthe other hand, real estate and financial professionals often have basic knowledge of theEnglish names of key concepts in their profession. In the end, all quotes used in this paperhave been translated to English. A similar problem occurred with the analysis of writtensources that were mostly but not exclusively in Italian, but the proximity of colleagues andof a dictionary, as well as the absence of high time pressure (a significant factor ininterviewing), made the analysis of written sources from the language point of view mucheasier than interviewing professionals.

Housing, Credit, and Mortgages in ItalyItaly is a country of home ownership, but traditionally it did not have a very developed

mortgage market. Owner-occupation increased from 40 percent in 1950 to around

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 181

80 percent today. Home-ownership rates are increasing for both higher income groups andblue-collar workers (Tosi and Cremaschi 2001). The rental market takes up most of theother 20 percent of the Italian housing stock. Actually, the lack of alternatives in the rentalsector is mentioned as one of the reasons for the high proportion of homeowners in Italy(Del Boca and Lusardi 2003) because the market structure is quite rigid and the decreasein the rental sector has made the overall market less flexible, while demand for housingitself has become more flexible (Tosi and Cremaschi 2001). Moreover, through severalrounds of liberalisation (in particular, the 1978 reform, which was meant to limit rentincreases but led to tenant evictions on the one hand and to under-investment on the otherhand), private-rented housing has become much more expensive while the small stock thatremained rent controlled became frozen (extremely low out-migration) and virtually in-accessible (Bernardi and Poggio 2002; Tosi 1990). Meanwhile, the social rented housingstock has received little investment, and is aimed at satisfying the need of only poorhouseholds (Indovina 2005).

In addition, fiscal treatment of home ownership is rather favourable: “Until the early1980s, owning real estate properties in Italy was basically tax free” (Ave 1996:77); imputedrents are taxed on the basis of administrative values, which are below real market values;tax rebates do exist for mortgage interests; and intergenerational transfer are taxed in afavourable way (sometimes almost tax free) (Bernardi and Poggio 2002). Other reasons forthe high home-ownership rate are the low cost of higher education (which enables peopleto save or invest in housing), the relative stability of the Italian family, the sale of (social)rental housing, the very low geographical mobility (Ave 1996; Del Boca and Lusardi 2003;Indovina 2005), the existence of home-ownership programmes, and the slow rate ofpopulation growth.

Historically, the Italian credit market offered few feasible solutions to finance homeownership. Compared with most other European countries, the Italian mortgage marketwas characterised by very restricted lending policies. Until 1980, there was a law that saidthat mortgage loans could only be granted for up to 50 percent of the estimated propertyvalue, but even when the loan-to-value cap was increased to 75 percent in 1980, and to 80percent in 1993, many financial institutions, but also many households, preferred lower andthus less risky loans. An important reason for financial institutions to ration credit is thatItaly has a complicated system to take possession of property on defaulting loans: it takes5.5 years on average to repossess collateral, 4.5 years in northern Italy, and 6.6 years insouthern Italy. Also, the information system in the mortgage market, and credit market ingeneral, was up until some years ago not very well developed, which also resulted in higherrisk (Bernardi and Poggio 2002; Chiuri and Jappelli 2002; Del Boca and Lusardi 2003;Generale and Giorgio 1996; Sironi and Zazzara 2003; Villosio 1995). Other importantfeatures of the Italian credit market, in particular in the late 1970s and early 1980s, are theunusually high inflation and real interest rates. Even though inflation and interest ratesdecreased in the mid-1980s, until the beginning of this century, they stayed remarkably highcompared with other European countries. The most striking change is undoubtedly infla-tion, which reduced from 12.1 percent in 1980 to 3.9 percent in 1994 (Ave 1996:13) and

182 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

less than 3 percent in recent years. High and often changing interest rates in the creditmarket at large coupled with high inflation also made mortgage loans less attractive forboth banks and households compared with many other (European) countries.

Finally, mortgage loans used to be the responsibility of specialised credit institutions;banks were excluded from operating in the mortgage market because their role was limitedto short-term credit. But after the deregulation operation of the 1980s, banks also enteredthe mortgage market, and the number of mortgage loans rapidly increased because

banks considered mortgages to be particularly attractive in terms of interest rates charged, which wereusually higher than business loans. . . . From the late 1980s the growth rate of mortgages granted bybanks to individuals had reached 25–30 percent per year, much higher than any other credit sector.However, the trend declined sharply in 1990 and 1991, in parallel with the economic recession and theslowing down of the real estate market. (Ave 1996:81)

In 1995, the average mortgage loan in the largest thirteen cities was 42 percent of theproperty value (Ave 1996), and mortgage credit comprised less than 6 percent of GDP.During the late 1990s, however, the fall in interest rates and the economic growth of thepreceding years have led to a boom in mortgage loans, resulting in annual increases of over15 percent (cf. Tosi and Cremaschi 2001).

Once banks were allowed to offer mortgages, it took some time before a well-developedmortgage market developed. Indeed, Italy’s capital market is considerably less developedthan that of Britain, Germany (Alessandrini and Zazzaro 1999:90), Denmark, or TheNetherlands (Aalbers 2006b), and up to the mid-1990s, “mortgage conditions supplied toItalian households were among the worst ones within Europe, in terms of both typicalloan-to-value, real interests and maturity applied” (Bernardi and Poggio 2002). For a longtime, ten years was the maximum time to pay back a mortgage loan, while in many otherEuropean countries and in the U.S., twenty-five- to thirty-year maturities were common(Del Boca and Lusardi 2003:684). In addition, loan applications were processed in a slowand very bureaucratic manner.

In Italy, there is a co-evolution of the institutions of family and home ownership, bywhich the first enables the second, and the second increases the importance of the first.Indeed, “savings over the life course, self-development and family support seem to haveplayed a mayor role in enabling people to enter homeownership” (Bernardi and Poggio2002:8). Even though it is a cliché, it is hard to overestimate the importance of the family,not just in the Mezzogiorno (the South), but also in the Industrial Triangle of the Northwest(Milan, Turin, and Genoa) and in Third Italy (the Centre and the Northeast). The traditionalfamily may be stronger in the South; the high prices of real estate in the North compelespecially first-time homebuyers to rely on their families. Indeed, the family is an importantsource for the down payment, for monthly payments, and also for inheritance (Guiso andJappelli 2002; Tosi 1987). Traditionally, intergenerational transfers to young members havereplaced the lack of alternatives in the credit market (Bernardi and Poggio 2002). For theearly 1990s, it was estimated that intergenerational transfers supported about 30 percent ofItalian homeowners, and about 20 percent of homeowners even received their houses as

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 183

gifts or inheritance (Guiso and Jappelli 2002). Family transfers help overcome liquidityconstraints in housing purchases by shortening saving time by one to two years andallowing households to purchase considerably larger homes (Del Boca and Lusardi 2003;Guiso and Jappelli 2002). Indeed, the incidence of becoming a homeowner this way hasonly increased, leading to what Nuvolati has called a sort of “treasurisation” of thedwellings (Mingione and Nuvolati 2003; Nuvolati and Zajczyk 1990). Because intergen-erational transfers play an important role in facilitating home-ownership attainment,housing also deepens and structures existing social and economic inequalities (Bernardiand Poggio 2002), leading to a reciprocal evolutionary change in the interacting systems offamily and home ownership, resulting in both the security of family structures and in lowresidential mobility.

Recent Developments in the Mortgage MarketSince the early 1990s, but especially in the late 1990s, there have been some important

changes in the Italian mortgage market. Together, these changes have enabled and em-bodied the switching of capital to the secondary circuit. First, there is no longer a law onthe loan-to-value cap. Consequently, it has become possible for banks to grant higher loans.In the past, this did not automatically lead to banks offering higher loans, but in the last five(to ten) years it has due to other reasons. Second, information on the supply-side hasimproved, which makes it less risky for banks to grant loans because they can betterestimate their risks. Third, the organisation of the mortgage market has changed dramati-cally. Not only has the external regulation (laws etc.) changed in order to adapt to a more“European” banking system, but the internal regulation of the banks has also changed. Inaddition, the Amato Act of 1990 allowed banks to provide mortgage loans, which in the pastwas only possible for specialised credit institutions (Casini 1995). Financial deregulation iscoupled with a great and ongoing restructuring of banks, leading to bigger banks and tocooperation and information-sharing between banks, resulting in an increased transparencyon the supply-side of the market. Fourth, competition in the mortgage market has increaseddue to the above-mentioned factors as well as through the entry of foreign players in theItalian credit market who see providing mortgages to Italians as an attractive growthmarket, particularly when their “home markets” offer few opportunities for expansion(Aalbers 2006b). For example, Abbey National, a British bank specialising in mortgages,was one of the first banks to open foreign branches in Italy (Del Boca and Lusardi 2003),but many other banks such as ING, Paribas, and Woolwich are also active in the Italianmortgage market. This has led to a reaction on the part of Italian banks as they try not tolose their market share and hence increase the possibilities for mortgage loans.

These four changes in the Italian mortgage market all apply to the supply-side of themarket. They fit well into the framework provided by Harvey’s theorisation of capitalswitching in which the role of investors and financial institutions is emphasised. Harvey,partly as a reaction to neoclassical economics that had over-emphasised the role of con-sumer sovereignty, underplayed the role played by individual homeowners and home-buyers. I do agree with Harvey that their actions are largely determined by the structure

184 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

of the market; yet, it is important to pay attention to how households have reacted to thesechanges, and themselves have changed the ways of the market.

The first of the four changes on the demand-side of the market is that there seems to bea higher acceptance of the risk of mortgage loans in general, and of high loan-to-value andhigh loan-to-income ratios in particular. This is partly a result of the next reason. Second,due to the much faster rise in housing prices than income, people need to borrow more tobuy a house, displaying the relation between rising prices and higher demand typical of thesector. Third, because the rental market continues to offer fewer alternatives, there is ahigher demand for mortgage loans, also among groups that traditionally favoured rentingor were forced to rent due to market constraints. Fourth and last, real estate is seen as a goodinvestment, and it is increasingly realised that ownership of real estate holds a key to futureincome generation and (as was traditionally well realised in Italy) to security. While thereis a general sense of economic depression, real estate is seen as a safe haven:

It thus seems that the real estate sector has benefited from the troubled general economic climate andthat investment in real estate would appear to be a popular alternative in phases of uncertainty andinstability, considering its ability to maintain its value and particularly the continual reduction ofinterest rates (also providing benefits to the loans market, fuelled by the reduction in debt charges).(Nomisma 2002:3)

Put differently, we can see a process of capital switching from the primary to the secondarycircuit of capital. This process has been encouraged by the European Union, and inparticular, the European Monetary Union, which asked for changes in national bankingregulation, not just to make the differences between countries smaller, but also to dis-continue the existence of different financial systems within one country (such as short-termvs. long-term financial institutions in Italy).

Altogether, there has been a steady increase in the supply of and demand for homemortgage finance as well as a number of new, often large, suppliers. Although Alessandriniand Zazzaro (1999:90) in 1999 still maintained that “Italian households still opt for moreliquid and, thus, less risky investments,” this conclusion would be hard to sustain today. Thechanges in the mortgage market resulted in lower interest rates, higher possible loan-to-value ratios, higher possible loan-to-income ratios, and longer loan periods. Lower interestrates made mortgage loans more affordable but they also resulted in increasing houseprices. In particular, higher loan-to-value ratios are important as it means that the level ofdown payments required to buy a house is lower, and that has a potentially strong effect onthe young, who are the most likely to need a mortgage when buying a home, but it “alsoshifted the burden of homeownership from large down-payment to greater mortgagepayments” (Del Boca and Lusardi 2003:682; cf. Chiuri and Jappelli 2002).

By 1993, when the landslide changes in mortgage market had just been initiated,mortgage instalments rose as high as 52 percent of family income (Del Boca and Lusardi2003; Villosio 1995). Since 1993, changes have had more impact, and Italian banks havealso extended maturities. But because prices have also increased, mortgage payments tendto be high for households who took out loans with a high loan-to-value ratio. One of the

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 185

reasons behind the rising prices of residential real estate is the widened access to mortgageloans because it has increased the possibilities to buy a house for many households, and thishas increased competition for housing, which results in higher real estate prices. This inreturn, may tempt, and has tempted, banks to loosen mortgage requirements further (lowerdown payments, higher loan-to-income ratios, loans for people without fixed employment).This mirrors developments in other (European) countries where the loosening of mortgagerequirements made it possible for households to acquire more expensive properties, butalso lead to higher housing prices. The banks pursued a policy of cheap money; to “keepthe market going,” mortgage requirements were loosened further (cf. Aalbers 2005c; DNB2000). The price boom(s) associated with the expansion of credit possibilities created asituation in which homeowners with outstanding mortgage debts also began to carry morerisk (see also Stephens 2003). In other words, banks as well as households take on morerisk. Furthermore, the expansion of the mortgage market has included a new group ofborrowers that carry higher risk than other groups.

Economy, Migrants, and Housing in MilanThe city of Milan (1.4 million inhabitants) is the centre of a metropolitan area of about

four million people. Milan represents, without any doubt, the main Italian economic centrewith almost full employment:

Here we find most of the financial flows and activities, of production-related services, of the head-quarters of foreign companies, which are active on the Italian market. The Milanese production systemis extremely vital and shows a relevant capacity to penetrate international markets together with adeep-rooted presence on the Italian market. Therefore, we can maintain that Milan is a “rich” city, witha good capacity to create wealth for its population, also because it has a concentration of high-leveljobs. For this reason the province of Milan ranks first among the Italian provinces as far as annualper-capita income is concerned (about 160% of the national average). (Andreotti et al. 2000:41–42)

Although the “impressive regional growth of the service industry has strengthened thecentrality of Milan at both the regional and the national level” (Gualini 2003:267) thedynamism of its buoyant economy “is slipping away from its urban core to the surroundingareas and municipalities” (Healey 2004:51). Milan is the Italian city that best represents themain features of the so-called post-industrial or post-Fordist economies. This is perhapsbest exemplified by the Pirelli Company, once one of Milan’s largest manufacturers andimportant in the decade of the Economic Miracle—the period of 1950–1965 witnessed byhigh economic growth—and, today, one of the largest real estate developers in the country.The oil and industrial crises of the early 1970s hit Pirelli hard, but the subsequent restruc-turing of the industry and the company itself made Pirelli rise like Phoenix from theashes—a car tyre manufacturer turned real estate developer using their derelict brownfieldsfor large and profitable urban redevelopment projects. Indeed, Pirelli also exemplifies theswitch to investment in the secondary circuit of capital in times of crises in the primarycircuit.

While Milan is the dominant economic centre of the country, its own historical centreis the centre of a housing market with high demand and high prices. The nineteenth-

186 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

century, pre-war and post-war belts around the city have historically been a mix ofhigher-priced and lower-priced areas, with especially some parts of the west of the cityhousing the rich. This pattern is being altered and in some way simplified over the last twodecades: the closer to the centre, the higher the housing prices (both owner-occupied andrental) (see, e.g., Borsa Immobiliare 2003). Traditionally, poor areas, for instance, southand north of the centre, are “catching up” with the prices in neighbouring areas, and thepoor are priced out due to a general lack of rent protection. Beyond the city borders, thesuburbs, banlieue, or hinterland (a German phrase often used in Milan) presents a mix ofcheaper housing and of desirable single-family housing, but also includes the biggestpockets of poverty and small yet dense immigrant concentrations, as well as the houses ofthe superrich, and everything in between. At the border of the city of Milan and thehinterland, we find the periphery. This zone, often close to the Tangenziale (the highwayring road) and thicker in the north and northeast of the city, predominantly houses the“working class” and is generally seen as not very attractive with lower housing prices thanin the city itself (cf. Zajczyk 2005; Zajczyk, Borlini, and Mugnano 2005). In the last fiveyears, house price increases have also been the greatest in the first ring around the citycentre (mostly nineteenth-century districts), followed by the city centre itself and thesecond ring around the centre. Prices in the periphery have also increased, but much lessthan the average increase of both the city and the region (Borsa Immobiliare 2003).

Another important factor is the high price of housing, not just in the central areas, butalso in general. Rents in the private market have skyrocketed because of the breakdown ofthe old regulatory system and rental units have been sold off, while demand for them hasbeen increasing. Prices in the owner-occupied market have also increased much more thanincomes have. In 2001, for example, in Italy, prices went up by 17 percent, and by morethan 25 percent in Milan and 40 percent in specific areas (Nomisma 2001). Other sourceseven mention increases up to 60 percent. In addition, the Milan housing market, like thatof Rome, is more speculative than in other Italian cities: “The price gains can be greaterthan elsewhere in the country, but by the same token the price losses can also be massive”(Ave 1996:118).

With 8 percent, the rate of foreigners in Milan is low compared with major Europeancities in the North and West. One-third comes from the “old” European Union (EU15instead of the current EU27); other major migrant groups are the Eritreans, Egyptians,Chinese, and Filipinos. Although it is often argued that “there are no signs of geographicalconcentration or traces of immigrant ghettos” (Andreotti et al. 2000:39), we do in fact seeconcentrations in certain parts of the city. Nonetheless, concentrations tend to be small, andbecause of the low rate of foreigners, concentrations are usually not very dense. Butbecause a large part of migration to Italy is undocumented, actual concentrations can bereal. The earliest areas of immigrant settlement were close to the city centre, mostly innineteenth-century districts such as Lazzaretto. Currently, the pattern is much more diffusewith some nineteenth-century districts showing increasing concentration (e.g., Chinatown,northwest of the centre), others showing reduced concentration (e.g., Lazzaretto, north ofthe centre) due to gentrification pressures, and new immigrant areas forming all over the

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 187

city, its periphery, and the metropolitan region (including some of the suburbs and townslocated quite far from the city centre). While the resulting pattern is indeed diffused, it isnot possible to say that there are no signs of geographical concentration. In this sense,immigrant concentrations fit the image of Milan as a plural and fragmented city (Balducci2003:66) with “the emergence of pockets of marginalisation often linked to the accelerationof immigration from poorer countries; and this has occurred in a wide variety of spatialpatterns” (67). Yet, social polarisation compared with other major European cities, isrelatively low (Andreotti and Kazepov 2001:178).

The Milanese Geography of Access to Mortgage LoansIn previous sections, we have seen that the mortgage market in Italy until recently was

comparatively undeveloped. Recent changes, partly as a result of EU requirements, haveled to a tremendous growth in mortgage supply, in particular, in a city like Milan wheresuch changes touch the ground first. In this section, we will see how the changes in theItalian mortgage market work out in the geographically differentiated spaces of the Milanmetropolitan area. We will see that a switch to the secondary circuit of capital does notnecessarily imply that increased availability of credit is evenly spread over the metropolitanarea. Indeed, capital also switches between different places within the secondary circuit. Itis important to note that the supply-side changes on the Italian mortgage market describedabove are structural changes made mostly by national institutions as a response to bothnational and international demand for such changes; demand-side changes are largely aresponse to these changes as well as to wider social changes. Changes in the geographic-differential access to mortgage loans, as described below, are much more local in theirorigins and impact. On the one hand, they are the banks’ reactions to structural marketchanges, but on the other hand, they also reflect and give direction to local unevendevelopment. Indeed, local, geographically differential lending policies are a structuringelement in uneven development.

Data from Borsa Immobiliare (2004) show that the Milanese mortgage market has notonly grown tremendously, but also that the co-evolution of family and home ownership hasbeen sustained. Milan is a very expensive city, which is mostly home ownership-oriented;mortgages are mainly taken out by young couples who are supported by affluent parents(see also Mingione 2005); more than 50 percent of new mortgages in the last five yearshave been distributed to people between thirty-one and forty years. Increased access tomortgage loans has lead to higher prices, and to keep up with these prices, the averageamount of new mortgage loans has risen as well. The average price of a house (93.7 percentof which are apartments) was €216,100 at the beginning of 2004; the average height of amortgage loan was €135,023 up from only €86,400 two years before. Two-thirds of newlyissued mortgage loans have maturities of twenty years or longer; and about 80 percent ofthe houses measure 45 to 125 sq. m. (Borsa Immobiliare 2004).

There are two dominant trends in geographically differential access to mortgage loansin Milan. First, the geography of access to mortgage loans in Milan parallels the geographyof development in Milan. And second, the development of access to mortgages has

188 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

increased throughout the city and the region of Milan. Let me illustrate this structural shiftwith some representative and captivating examples from the interviews with different typesof real estate and banking professionals:

Twenty years ago it was harder to get a good mortgage. No matter where you would buy a house. Thewhole mortgage market has changed so much since then, and especially during the last ten years. So,in general, it has only become easier to buy a house, no matter who you are or where you want to live.(Real estate consultant)

Nowadays, you can get a loan for the full value of your house. That is incredible—at least in Italy. Ifsomeone had told me that ten years ago, I would have said: “You are crazy. This is not how things goin Italy.” But this is exactly how things go in Italy today. Not so long ago, people who took out amortgage for 50 percent of the estimated value of their house were the exception, because that wasconsidered high. Not anymore. Now 50 percent is becoming the exception because it is considered low.(Real estate agent)

Traditionally, Italians did not like to take out high mortgage loans, and traditionally, the financialsystem also didn’t make it possible. But households think different now, and so does the financialsystem. And although there are differences, you can get a mortgage in any part of the city and thehinterland much easier than ever before. (Bank manager)

As a result of the structural changes described above, access to mortgage loans since the1980s has become easier everywhere in the metropolitan area of Milan, representing theswitch of capital to the secondary circuit. That does, however, not mean that there are nodegrees in the level of widened access to the mortgage market. I do not want to get into thedetails of how borrowers or collateral in general are assessed, but the general idea is that

with the remarkable growth of the mortgage market and the much higher loans that are possible thesedays, it did not mean all banks started giving loans at full value to everyone, at every place. It still verymuch depends on who you are and what you do, and what kind of job you have: precarious work orfixed employment. (Real estate agent)

Rather than focusing on the assessment of borrowers, I will explicate how location hasaffected the mortgage loan application process and how the Milanese geography of mort-gage lending has been rearranged. A wide majority of the respondents, and almost all of theinterviewed real estate agents, contend that access to mortgage loans is geographicallydifferentiated, and that this was the case twenty years ago as well at it is now:

Milan is not a single space, it is multiple spaces. It is not surprising then that the mortgage marketmakes differences across space. The opportunities to make profits are different in different parts of thecity. Indeed, the access to mortgage loans will also be different. (Real estate consultant)

Banks make distinctions between neighbourhoods. The distinctions they make are not the same as theywere. What may be considered a “good investment” today may have been considered a “bad in-vestment” in the past. But also, what were once “bad investments” can now be “good investments.”(Real estate agent)

Access to mortgages has been contingent on geography, and since the geography of Milanhas changed, so has the geography of housing finance: capital has switched from different

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 189

places, from one neighbourhood to another (Harvey 1985; see also King 1989b). Theinterviews show that capital has switched in favour of nineteenth-century areas, and indisfavour of some peripheral areas. In Milan, it used to be some inner-city and nineteenth-century districts that were considered unsafe investments and were therefore yellowlined,but these areas are now receiving considerable mortgages loans on favourable conditions(greenlining):

If we go back to the late 1980s, we can see that poor areas close to the centre were the areas were itwas the hardest to get a mortgage, areas with a bad reputation and where crime was also high.Sometimes these were mixed-use areas where people lived between small factories and other func-tions. In other cases they were residential areas where poorer people were living. (Real estate agent)

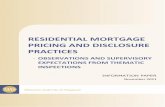

This real estate agent names Lazzaretto as an example of a “poorer” area, and Navigli as anexample of a mixed-used “dirty” neighbourhood. The Lazzaretto area (Figure 1), just northof the city centre, was renowned for the first foreign migrant settlement in Milan, but hasbeen undergoing gentrification in the last ten years or so. Although it still has the image ofan immigrant area due to the many meeting places for migrants as well as the many ethnicrestaurants and take-outs, it is also considered a popular and expensive area to live. Navigli(Figure 1), directly south of the city centre, but also close to the edge of the city, is an areanamed after the canals that characterise the neighbourhood and that originally had anindustrial use. It was known as an unattractive area to live. Nowadays, it is a popular areafor a night out with its restaurants and bars, and opportunities for a walk along the canals.Subsequently, the area surrounding the canals has been gentrified.

While, during the 1990s the nineteenth-century districts of Navigli and Lazzaretto cameback in financial fashion, banks started to consider outer-city areas the least attractive andsubsequently yellowlined them:

All of a sudden these places became popular places to live and the banks followed suit. They werecertainly not the first to invest in these neighbourhoods. The banks started to adjust their policies to thedemography of mortgage applicants for these areas. But around the same time, some banks, only some,started to reconsider their finance policies in the outer areas of Milan. There were lots of attention inthe media for these areas, crime was rising, and banks realised that the lack of services in some of theseareas did not make them very attractive places to live. But contrary to the policies in the ring aroundthe historical centre, these policies were much more selective. A smaller number of areas wereexcluded. In general, there was no problem is getting a mortgage in post-war areas, but it was thoseplaces without services in which it was harder, but certainly not impossible, to get a mortgage.(Real estate consultant)

This consultant shows that there was only a small number of outer post-war areas in whichit was harder to get a mortgage loan, but also that there were important differences betweenthe banks. Below, I will come back to differences between banks. First, the focus is onhistorical development in the geography of housing finance:

You have these areas with no services, and one block of flats after the other. Just blocks of flats androads, and that’s it. What kind of areas were these? Who wanted to live there? People who lived therewere people without a choice; people who could not afford to live in the same type of flat closer to the

190 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

centre. So, it was very clear that it was not the housing type that was the problem. The city is full ofblocks of flats, literally full of it, but it depends a lot where this flat is located. The same types of flatshave very different prices in different parts of the city, and some banks have shown a preference notto supply loans to some areas. Usually, they would not tell you that, but they would let you know: “thisapplication may take some time” or “did you try this and this other bank?” And then you tried the otherbank. If I know that bank A would only give me a loan there for 50 percent of the value and bank Bfor 70 percent of the value, I direct my client to bank B. Well, when that client needs more than 50percent of the price. (Real estate agent)

FIGURE 1. THE MILAN METROPOLITAN AREA WITH INDICATIONS OF SOME OF THE

AREAS (FORMERLY) FACED WITH UNEVEN MORTGAGE LOAN CONDITIONS.

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 191

In several outer-city areas, things also improved and several real estate agents, but also areal estate consultant indicated that the construction and extension of the new yellow metroline made a positive change in some areas. In the Affori area in North Milan (Figure 1), forexample, mortgage loans were provided on less attractive conditions (such as higher downpayments and higher interest rates) by some banks, but since the plans to extend the yellowmetro line to (and beyond) Affori became serious and realistic, yellowlining practices werereplaced by greenlining practices. Since the “discovery” of these new submarkets tookplace at the same time as the more general deregulation and expansion of the Italianmortgage market, loan conditions in these formerly yellowlined areas improved in manyways:

The construction of the yellow metro line has been a good thing for some areas in North Milan andSoutheast Milan. It was like the real estate industry discovered a new market in which they had notmuch activity in the past. That market had to be exploited, and the banks cooperated. That is a recentdevelopment and it parallels the general expansion of credit. So, just imagine, there was this area werethis bank was cautious to provide 70 percent loans, so they asked for 50 percent down-paymentsinstead of 30 percent, and now things changed: the general down-payment became let’s say 5,000Euro, and for this area it was also 5,000! While it had been, let’s say 75,000 Euro—half of 150,000Euro—up until very recently. As a real estate agent that means good business because that increasesthe possible number of transactions, but also the prices paid for apartments in such areas [whichimpacts on the agent’s fee]. (Real estate agent)

More peripheral areas, often outside the municipal borders, such as Cinisello Balsamo inthe North and Corsico and Rozzano in the South (Figure 1), however, continue to face extraloan requirements (yellowlining). And even though some agents say that they can get theirclients a loan in any part of metropolitan area of Milan, they also admit that it is impossibleto get a mortgage loans with 100 percent loan-to-value under normal conditions. Majorlenders yellowline these areas by either providing a lowering of the loan-to-value cap or bycharging higher fees or higher interest rates:

I can get you a mortgage anywhere in Milan—no problem. But I cannot get you a 100 percent loananywhere in the city. That’s the difference. Some banks do not consider some parts of the peripheryvery attractive, and they will ask you for higher down-payments. There are other financial institutionsthat will grant 100 percent mortgages there, but they will charge special fees. If you buy a property inCinisello Balsamo, for example, bank A and B will not grant a full mortgage; bank C will, but it willalso increase interest charges. And then if you go to these other institutions everything seems to bepossible, but often it is not. Yes, if you have a high income it is, but if you have a high income, you willnot move there. (Real estate agent)

The major mortgage lenders have greenlined most of the Milan metropolitan area, but haveyellowlined parts of the periphery and the hinterland. Next to these major lenders, there arealso active small “fringe” lenders that provide predatory loans with extremely high interestrates (usury) and high additional charges (see Dal Lago and Quadrelli 2003:chapter 4), butI will not get into predatory lending here. Instead, the focus remains on the geography ofmainstream mortgage lending. Here, yellowlining means higher interest rates and higherdown payment requirements. It is important to note that there are also big differences

192 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

between peripheral areas, and that the time of construction is an important factor in this,while building type is not significant. In other words, assessed collateral depends partly onthe interaction of location and time of construction:

The periphery is not one entity. The most advantageous mortgage loans will be provided in theperiphery, but also the least advantageous ones. In general, it is harder to get an advantageousmortgage in a peripheral area built before 1980 than in a recent peripheral development. This is notbecause of the block of flats in these areas; newer areas also contain many blocks of flats, and the olderones also contain single-family dwellings. (Real estate consultant)

The age of the house is of importance too. It is so much easier to get a full mortgage for newconstruction. All banks say they give 100 percent mortgages now, but in fact many of them only give100 percent mortgages for new developments. If you want a 100 percent mortgage for an older houseyou are likely to pay much more interest. (Bank manager)

New developments, even in the least attractive parts of the periphery that lenders havelargely yellowlined, continue to be greenlined as several lenders seem eager to cooperatewith private developers to offer attractive loans to prospective homebuyers, thereby makingthe success of these new projects more likely.

But also neighbourhoods still matter: the periphery of the city is not very popular. In fact, it is an areathat receives many loans, but at the same time it isn’t. I mean, for some new projects at the edges ofthe city—Bicocca, Rogoredo—you can easily get a mortgage to cover all costs. Developers oftencooperate with certain banks: the banks promise to give high loans to whoever needs them, and thedevelopers promise to direct homebuyers in their direction. (Real estate agent)

There is a geography of housing finance in Milan, but it is not always a straightforward andplain pattern. There is a strong connection with housing prices and distance from the centre,but also with the building period, and the level of services in the neighbourhood. Finally, asalready briefly mentioned above, there are strong differences between banks, with somebanks engaging more in yellowlining practices than others:

Yes, we have spatially selective policies. I would never tell you what these policies are. That is a matterof banking secrecy. But yes, in fact, we do have such policies, and I know they are different from otherbanks and financial institutions. (Bank manager)

We provide mortgages in every part of the Lombardy region. That is our policy. . . . But in some areas,people may also be less likely to get a loan-to-value of 100 percent. In some areas outside the bordersof the city, we will not just provide a 100 percent loan-to-value. Other banks do provide mortgage loansthere, even for 100 percent loan-to-value, but then the conditions for the loan will not be as advanta-geous as our conditions. (Bank manager)

Different banks have different policies: different guiding principles for different groups, but alsodifferent guiding principles for different neighbourhoods. If I have a client that wants to buy in thisarea, he will be able get a mortgage at any bank, but when I sell him a house in Corsico or RozzanoI will suggest him to contact certain banks and not others. (Real estate agent)

It is fair to conclude that the Milanese geography of access to mortgage loans is contingenton the lenders and their policies, but it is also fair to conclude that through time different

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 193

banks adapt their geographical mortgage policies in similar ways. To many, it may not comeas a surprise that banks have geographically differential lending policies, but in general,lending policies largely follow conventional loan-to-value and loan-to-income standards.The value of the surrounding area is, by definition, calculated in the price of a propertybecause location is an intrinsic attribute of that property, and therefore included in theassessment of the collateral. The present research shows that in Milan, banks move beyondthese conventional lending standards and that geographically differential lending patterns1) do exist, 2) continue to exist in a rapidly expanding and increasingly competitive market,3) are dynamic in the sense that areas fall into banks’ favour and disfavour over time, and4) are different for different banks, partly reflecting different risk assessments and differentperceptions of urban space, and partly reflecting market specialisation (which is still in anearly stage). In addition, the yellowlined areas accommodate a higher share of low-incomepeople than other areas in Milan, but these areas are not overlapping with concentrations ofpoverty (compare Figure 1 to figures 1–3 in Zajczyk 2005).

ConclusionsCapital switches between different sectors of the economy, but also within sectors of the

economy, for instance, between different places. In the mortgage market of Italy, “capitalswitching” in the last ten years or so took place from the primary to the secondary circuitof capital. First, on a national level, in recent years, real estate investment has been used asa safe haven in times of economic stabilisation and depression. Second, also on a nationallevel, the restructuring of the financial services industry in response to changes in thenational and international regulatory environment implied that historically stringentlending criteria were loosened to enable capital flows in the real estate sector, leading to atremendous growth of the mortgage market. Although this enabled households to take outbigger loans and make smaller down payments, the related increase in housing prices havenot necessarily made home ownership more accessible. In addition, the co-evolution offamily and home ownership has been sustained. Milan is a very expensive city, which ismostly home ownership-oriented; mortgages are mainly taken out by young couples whoare supported by affluent parents (see also Mingione 2005). As a result, the high degree offamily support and the housing cycle (and social selectivity) are intertwined. This selec-tivity contributes to explain why the mortgage market, even though it has expanded a lot,is still less dynamic than in countries like the U.S., the UK, Denmark, and The Netherlands.Harvey’s argument that capital switches from the first to the secondary circuit is validatedby the Italian cases, but Harvey’s critics are also right in arguing that the secondary circuitpresents an investment channel in its own right. The case of Milan shows that capitalswitching to the built environment is partly a sign of economic crisis, something that isaccepted by part of the Italian public debate, and partly a sign of the intrinsic economicopportunities that the built environment provides. A major factor in both is that thederegulation and re-regulation of the mortgage market has enabled capital to switch to thesecondary circuit in order to avert the crisis in the primary circuit, but also to be able toextract the opportunities that the built environment by its very nature offers.

194 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007

Capital switches between different opportunities; this can entail switching between theprimary and secondary circuits, but also switches within one circuit. In the metropolitanarea of Milan, capital switches within the secondary circuit from one area to another. Once“unattractive” but currently gentrified nineteenth-century neighbourhoods underwentcycles of devalorisation and revalorisation. In recent years, some post-war, outer-city, andperipheral areas have undergone devalorisation. The geography of housing finance haschanged, and even though access to mortgages has increased throughout the city and theregion of Milan, geographical disparities in mortgage lending persist, although the fate ofplaces has changed. Moreover, different banks have different lending policies reflectingdifferent risk assessments and different perceptions of urban space.

The geographic differential access to credit is a form of financial exclusion, rather thana form of financial abandonment. Redlining is not common in Milan, but yellowlining isthe order of the day. Banks greenline large parts of the metropolitan area of Milan (100percent loan-to-value mortgage loans on advantageous conditions), but they also disfavoursome, usually smaller, areas in which higher down payments are required or loan conditionsare unfavourable in another way (higher interest rates, lower loan-to-value ratios, specialfees). This form of yellowlining differs per bank, although in the long term the loan policiesof different banks are quite similar. As is the case elsewhere, “the comparative simplicityof redlining has been replaced” (Wyly, Atia, and Hammel 2004), but rather than beingreplaced by a structure of prime lending vs. predatory lending, it has been replaced by asystem of geographical differentiations with dominant greenlining practices next to yel-lowlining practices. This pattern depends on dimensions such as distance to the city centre,building period, social class, migration, and housing prices; it is far from a straightforwardpattern because it is contingent on the practices of individual banks. Only to a certain extentis the resulting geography of housing finance a result of structural changes on the nationallevel (partly pursued at the international level); individual policies of banks also reflect andgive direction to the structuring of local uneven development.

Capital switches between circuits and between places are an inherent part of the logic ofland markets under capitalism; surplus value can only be extracted if boundaries existbetween submarkets. The creation of boundaries makes the realisation of class-monopolyrent possible, while the subsequent redrawing of these boundaries creates new submarketsin which surplus value can be extracted. In this respect, the case of Milan is no differentthan most other cases; the structural elements just come in different shapes and sizes. Milanis different in the timing of appreciation and devaluation of different places. The late“opening up” of the mortgage market, in addition, makes the Milanese mortgage marketfundamentally different from most northern American and north-western European mort-gage markets, but not so different from mortgage markets elsewhere in Southern Europe,and perhaps also in Latin America and parts of Asia. Yet, it is important to stress thepeculiarities of the Milan case to understand the mix of structural and specific elements.Geographical patterns of housing finance are highly dependent on the existing social-economic geography, which is less polarised than its U.S. counterparts; this implies that, inMilan, boundaries are more porous and less easily exploited, like in many other continental

GEOGRAPHIES OF HOUSING FINANCE 195

European countries. Nevertheless, the Milan housing market with its dwindling privaterented housing stock facilitates the extraction of class-monopoly rent through the mortgagemarket. The deregulation and resulting expansion of the mortgage market is the expressionof a mix of global, European, national, and even local factors—most of these factors are farfrom unique, but the mix itself and the timing of it are unique to Milan. Based on the Milancase, one cannot explain the timing and geography of formation and reformation ofsubmarkets in other cities, but it helps us to see how Harvey’s abstract ideas of class-monopoly rent, submarket creation, and capital switching take place in the real world andhow the built environment is shaped to meet the requirements of capital accumulation.

REFERENCESAalbers, M. 2003. Redlining in Nederland: Oorzaken en gevolgen van uitsluiting op de hypotheek-

markt. Amsterdam: Aksant/Spinhuis.

Aalbers, M.B. 2005a. Who’s afraid of red, yellow and green?: Redlining in Rotterdam. Geoforum

36(5): 562–580.

———. 2005b. Place-based social exclusion: Redlining in the Netherlands. Area 37(1): 100–109.

———. 2005c. “The quantified customer”, or how financial institutions value risk. In Home owner-

ship: getting in, getting from and getting out, ed. P. Boelhouwer, J. Doling, and M. Elsingaed,

33–57. Delft: Delft University Press.

———. 2006a. “When the banks withdraw, slum landlords take over”: The structuration of neigh-

bourhood decline through redlining, drug dealing, speculation and immigrant exploitation. Urban

Studies 43(7): 1061–1086.

———. 2006b. The geography of mortgage markets. Working Paper, AMIDSt, University of

Amsterdam, Amsterdam. http://www.fmg.uva.nl/amidst/publications.cfm (accessed May 18,

2006).

———. 2007. Place-based and race-based exclusion from mortgage loans: Evidence from three cities

in the Netherlands. Journal of Urban Affairs 29(1): 1–29.

Alessandrini, P., and A. Zazzaro. 1999. A “possibilist” approach to local financial systems and regional

development: The Italian experience. In Money and the space economy, ed. R. Martin, 71–92.

Chichester: Wiley.

Andreotti, A., D. Benassi, M. Bernasconi, D. Carbone, R. Costaiola, E. de Filippo, C. Formisano et al.

2000. Comparative statistical analysis at national, metropolitan, local and neighbourhood level.

Italy/Milan and Naples. URBEX Series 5. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Study Centre for the Metro-

politan Environment.

Andreotti, A., and Y. Kazepov, eds. 2001. The spatial dimensions or urban social exclusion and

integration. The case of Milan, Italy. URBEX Series 16. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Study Centre for

the Metropolitan Environment.

Ave, G. 1996. Urban land and property markets in Italy. London: UCL Press.

Balducci, A. 2003. Policies, plans and projects. Governing the city-region of Milan. DISP 152: 59–70.

Beauregard, R.A. 1994. Capital switching and the built environment: United States, 1970–89.

Environment and Planning A 26: 715–732.

196 GROWTH AND CHANGE, JUNE 2007