Frozen Adventure at Risk? A 7-year Follow-up Study of Norwegian Glacier Tourism

Transcript of Frozen Adventure at Risk? A 7-year Follow-up Study of Norwegian Glacier Tourism

This article was downloaded by: [Universitetsblioteket]On: 18 December 2012, At: 01:26Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Scandinavian Journal of Hospitalityand TourismPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/sjht20

Frozen Adventure at Risk? A 7-yearFollow-up Study of Norwegian GlacierTourismTrude Furunes a & Reidar J. Mykletun aa Norwegian School of Hotel Management, University ofStavanger, Stavanger, NorwayVersion of record first published: 18 Dec 2012.

To cite this article: Trude Furunes & Reidar J. Mykletun (2012): Frozen Adventure at Risk? A7-year Follow-up Study of Norwegian Glacier Tourism, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality andTourism, 12:4, 324-348

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2012.748507

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make anyrepresentation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. Theaccuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independentlyverified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions,claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever causedarising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of thismaterial.

Frozen Adventure at Risk? A 7-yearFollow-up Study of Norwegian GlacierTourism

TRUDE FURUNES & REIDAR J. MYKLETUN

Norwegian School of Hotel Management, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

ABSTRACT This article aims at illuminating the contemporary glacier tourism scene, anddoes so by showing how glacier tourism in Norway has developed as an adventure tourismactivity over the past 7 years. In total, 17 companies offered guided glacier activities forapproximately 20–30,000 visitors per year. Data were collected by repeated interviews,website studies, and participant observation. The product variety covers guided day tours,longer guided tours, and glacier instructor courses. There has been product developmentfrom traditional glacier surface walks and activities in the glacier-arm area as well asglacier lake kayaking, terminal face walks, and ice climbing. Glacier tourism can be seen asa mix between purchasable short-term holidays and gradually acquired life-time skill. Thisanalysis focuses on five important preconditions for this adventure tourism niche, namely,natural resources, access, demand, entrepreneurship, and need for special competence. Thestudy also provides insight into current and future challenges and perceived risks on threelevels. Results indicate that glacier tourism is not dependent on large glaciers. Studyingcurrent companies’ location shows there is room for expansion in terms of extensively usingnatural resources where there is demand. However, some entrepreneurs are sceptical of theindustry’s future as recent recession of the glaciers has made access more difficult.

KEY WORDS: glacier tourism, adventure tourism, guiding, 7-year follow-up, entrepreneurship,Norway, implicit climate change adaption

Introduction

This study is the first to investigate preconditions for glacier tourism in Norway, andthe way this tourism niche has developed over 7 years. The activity forming the basefor this type of tourism, namely, walking and climbing on glaciated areas for theunique experience, as opposed to being a “transport leg” for reaching a mountainpeak or rock-face to climb, has been claimed to be a unique Nordic phenomenon(Breboka, 1999). This may be debatable, however, as there are 20 glacier tourism des-tinations worldwide. Glacier tourism is dependent on resources that are scarce, fragile,

Correspondence Address: Trude Furunes, Norwegian School of Hotel Management, University of Stavan-ger, Stavanger, Norway. E-mail: [email protected]

Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2012Vol. 12, No. 4, 324–348, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2012.748507

# 2012 Taylor & Francis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

and sensitive to climatic changes (Liu, Yang, & Xie, 2006). Although partially differentfrom other adventure tourism activities as outlined by Buckley (2006), other aspectsseem more similar. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first study ofglacier adventure tourism.

As genuine “otherness” (Simmel, 1971), the glaciated landscapes with their cold andunfriendly appearance, which are indeed threatened natural resources, are likely tomake powerful impressions on tourists triggering the travellers’ “Ulysses factor”(Anderson, 1970, p. 17ff), regardless of whether they enter the blue ice or enjoy theview at a distance. Hence, glaciers may be seen as representing the acceleratedsublime (Bell & Lyall, 2002), and may pose a special appeal to and motivate the adven-turous traveller (Singh, 2004).

This study investigates glacier tourism along the preconditions for adventure tourismdescribed by Buckley (2006), that is: natural resources, access, demand, entrepreneur-ship, and need for special competence. The natural resources, access, and demand maybe vulnerable to climate change (Hall & Higham, 2005); so the study explores howglacier tourism operators deal with the climate change dialogue. The research questionsdriving this study are: (1) How are glacier areas as natural resources used for this adven-ture tourism segment and how accessible are they? (2) How are the operators organizedand how may the underlying entrepreneurship be conceived? (3) What competence isrequired and how is it developed? (4) How are the products packaged to make themsaleable? (5) What is the demand and volume for these products? (6) How do the oper-ators and entrepreneurs perceive the current and future challenges for this tourismniche? For comparisons with other adventure tourism niches, parameters establishedby Buckley (2007) are included, namely, price, duration, accessibility, skills, groupsize, and client2guide ratios. In order to determine current and future challenges ofthis niche as perceived by the entrepreneurs, this tourism niche development hasbeen followed from 2003 to 2009.

Background

Natural Resources and Access

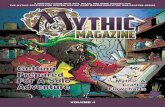

Norway has 1627 glaciers, covering in total 2609 km2 (Orheim, 2009). Unlike otherparts of the world (Liu et al., 2006), many are in mountainous areas near the coast,found mainly near the coast in South-Western and Northern Norway (Figure 1). Thelargest glacier, Jostedalsbreen, is 487 km2, accounting for 12% of total glacier for-mations in Norway. Its highest point is Breakula, 1957 m above sea level, and itslowest point is Supphellebreen, 60 m above sea level, which is also the lowest glaciatedarea in the Northern Hemisphere, south of the Arctic Circle. The maximum depth of thisglacier is 600 m and the annual snowfall is 12 m (Orheim, 2009). Also peculiar in alti-tudes is Svartisen (369 km2) stretching from 1594 down to 20 m above sea level. This isthe lowest glacier on mainland Europe; and is located north of the Arctic Circle. Itsmaximum depth is 540 m (Orheim, 2009). Five other glaciers cover from 170 to370 km2, and about 15 glaciers cover from 22 to 87 km2 each. The first total registrationof all glaciers was finished as late as during 1969 in Southern Norway and during 1973in Northern Norway.

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 325

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

Contrary to popular belief (Rønningen, 2010), most glaciers in Norway are notresidual from the last ice age. Those huge ice masses melted down, and the landscapewas almost free from ice 8000 to 4000 years ago (Orheim, 2009). Since then, high

Figure 1. Norway’s 21 largest glaciers (source: Wold & Ryvarden, 1996).

326 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

levels of precipitation as snow, together with low summer temperatures, have givenNorway unique conditions for glacier formation. About 4000 years ago, some of thewinter snowfall did not melt during the summer. Over years, new layers of snow con-tinuously covered the previous snow and as this became thicker it gradually melted, dueto high pressure from the upper layers of snow. It then froze due to the low temperature,thus being gradually transformed into ice.

This process of glacier formation still occurs, and the size of the Norwegian glacierscontinuously changes. A rapid growth took place as the main trend from 1600 to 1750,named the small ice age, due to heavy snow precipitation during winter times that wasnot counteracted by the same amount of snow melting during the summer (Vorren,Mangerud, Blikra, Nesje, & Sveian, 2007). Interchangeable growth and recessionperiods have been observed up to 1930, and finally after 1997 new recession has beenobserved as the general pattern with average withdrawals of glacier arms range from13 to 43 m between the years 2004 and 2008 (Orheim, 2009). However, again due toheavy winter downpour several glacier arms on the western part of Norway grew signifi-cantly bigger in the 1990s (Vorren et al., 2007). Although influenced by global warming,the direct factors controlling the growth and recession of glaciers are the balance betweenwinter precipitation and snow melting in summer, and contrary to popular beliefs(Rønningen, 2010), the Norwegian glaciers are not all rapidly vanishing. Different gla-ciers change in size at different rates (Orheim, 2009; Vorren et al., 2007). In 2010, 27 outof 31 measured Norwegian glaciers were in the process of recession.

Glaciers move downwards from their highest point at up to 700 m per year (Orheim,2009). Different portions of the glaciers may move at different speeds, constitutingactual “rivers of ice” (Vorren et al., 2007). The movement is caused by a combinationof weight, pressure, and the fact that ice is melting where it meets solid rocky ground.The ice, together with rocks and boulders frozen into the bottom of the glacier, conti-nually carve the solid rock underneath it, moving sand and boulders along its way. Theice cracks with rumbling sounds and slightly changes shape each day. These glacier for-mation processes are somewhat similar to ice melting at the ending of each of the iceages that shaped the landscapes and carved valleys and fjords. Hence, the glaciers mayfascinate visitors and residents alike due to their giant natural strength and power.Moreover, they are the most important archive for climate researchers regardingdetailed climate changes throughout the last hundred thousands of years (Orheim,2009). Consequently, they may be a natural resource for real adventure tourism devel-opment as well as education and scientific research (Liu et al., 2006).

Glaciers and the Concept of “The Accelerated Sublime”

According to Aall and Høyer (2005), glaciers were more popular in the first decades ofthe twentieth century than now, attracting glacier hiking, also known as mountainadventure tourism (Beedie & Hudson, 2003). However, this early interest in viewingglaciers decreased as they recessed. Interest and fascination with the sublime orharsh landscapes increased, and worldwide adventure tours of all kinds are offeredby companies or undertaken by travellers on their own (Singh, 2004). In tourism litera-ture, the phrase “sublime landscapes” has been used to denote vast wilderness with aparadoxical capacity to frighten, but also attract human interest, with thrills and

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 327

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

excitement. In contrast to pastoral, picturesque landscapes, there are vast, powerful, for-bidding, terrifying, and awe-inspiring landscapes holding the suggestion of death (Bell& Lyall, 2002). By coining the expression “the acceleration of the sublime”, Bell andLyall point to the ways extraordinary landscapes gradually have changed as attractions.In the seventeenth century, tourists quietly enjoyed pastoral landscapes at a distance.Later they gradually actively used landscapes by moving by horse, carriage, boat,and sledge or even on foot. Bell and Lyall called this development “movementsalong a line”, as the travel followed a road, path, or river.

A third step was the more forceful entrance into the vista for exploration and sports,using mountains as a playground for skiing throughout the late nineteenth and twentiethcenturies. The discovery of the “Northern Playground” by Slingsby (1904), also calledThe First English Skier, is an example of this process. According to Bell and Lyall, thisthird step may be called “using the plane”. The final step and current trend is constitutedby taking the room or volume into use. This last step is called “use of volume” by Belland Lyall, where using the room for free fall as in the case of BASE jumping from steepmountain cliffs could be the most striking and breath-taking example (Hallin &Mykletun, 2006). Attraction to glaciers fits into this development, mainly as anexample of the third step, “the plane”. As stated by Bell and Lyall

We can use the same continuum (from point to line to plane to volume) for thelandscape itself: From those discrete elements of landscapes encoded in pastoralstillness (the pond, the lake) to the first infatuations with the gently moving land-scapes (the slow upward drift of the bubbles of spa water) to the increasing chat-tering of the energetic brook, the river, the rushing stream, and the river (thelinear) to the far more energetic crashing of waves along the shore and the Vic-torian fascination with glaciers, those moving solid rivers of ice (plane). Vastvolumes of moving landscape, things that swept out the whole solid arena inshort periods of time . . .. (2002, pp. 54–55)

Glaciers may give experiences that meet all four steps of this “acceleration of thesublime”. Indeed, by being vast and solid formations of frozen water they representone of the most sublime types of landscapes, the real adversity of life, possessingpower to seriously change landscapes and changing the course of rivers. One of themain attractions of glaciers is the blue ice, moving through these slow continuouschanges. This uniquely coloured part of the glacier is highly compressed as “old” icebecomes visible when the glacier cracks open due to its movement. It stands in distinctcontrast to the top layers of ice, which are white or greyish with dark spots from air-borne dust from nearby mountain areas. Red-coloured areas may also be seen,caused by small algae on the snow surface. Several shapes and formations of the icemay be observed, all created by the ongoing glacier formation process.

At the lower end of the glacier, the ice continuously melts and breaks off blocks ofblue ice with thunder-like sounds. A cold river appears from a “gate” in the front of theglacier, and winds its way down the valley. The colour of the water is green or azure,and offers another fascination to the traveller. The ice-cold draft in the valley below theglacier may be experienced at a distance, the lower temperature increases the likelihoodof bright weather around the glacier, and finally it reflects light so that the ambience

328 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

in the valley is always unique, regardless of weather conditions and time of the day andyear.

Adventure and the Ulysses Factor

This attraction of the glaciers as well as the potential hazards of traversing them are criti-cal components of adventure products, and can be divided into hard and soft adventureactivities (Beedie & Hudson, 2003). Adventure tour companies offering hard adventureactivities, requiring higher levels of skills in more remote areas, tend to be smaller.There are also many small operators and relatively few large ones. More typical aresoft adventure tours that offer a combination of nature, eco, and adventure components(Buckley, 2000). Several aspects of risk add to it as an “accelerated sublime” attraction.An ice block falling without warning constitutes serious risk for bystanders nearby, andis a main reason for fatalities among tourists in these glaciated landscapes. Moreover,the sudden changes in the front of the glacier may block the river from the glacierand create rapid and serious flooding below the glacier, as it happened in the FortunRiver during early August 2010 (Mandal, Lura, Bordvik, & Børhaug, 2010).

The second risk is caused by cracks on the surface. These cracks may sometimes becovered by thin layers of ice or snow and be hard to spot. It is therefore difficult to deter-mine whether to enter into them or not. Being trapped in a crack is unpredictable regard-ing its outcome. Apart from being hurt on the ice, one may also fall into ice-cold wateror be stuck with low temperatures inside the glacier that will slowly reduce the ability tomove and lead to loss of consciousness. Finally, walking on the surface is difficult formost people. Traversing the ice with the special crampons stops sliding and falling, andindeed accelerates the sensation of adventure.

The “otherness” visits to glaciers allows escape from everyday life, and as such con-stitute what Simmel (1971) called the most general form of adventure. Moreover, gla-ciers can be considered playgrounds for tourists seeking different levels of challenges instrange and potentially hazardous environments. Anderson (1970, p. 17) applied theexpression of “Ulysses-factor” to denote the human search for novelty, the strangeand unknown, and an untested environment as a fundamental human motivation.The “Ulysses factor” is a psychological aspect of special relevance in the planningof vacations, through which people feel a deep need to explore and to discover whatlies beyond their known horizon (Anderson, 1970). It alludes to the myth of theancient Greek king Odyssey of Ithaca, and has also been coined as “the need toexplore” (Mayo & Jarvis, 1981). Everyday life, at least in Nordic countries, has beenextensively characterized by safety and predictability hitherto unseen in humanhistory, and consequently a feeling of boredom threatens. One solution to this psycho-logical entropy (Csikszentmihalyi, 1988) could be the undertaking of extreme sportsand adventurous activities, which may assist development of the individual’s identityand enhance his/her self-understanding (Skarderud, 2001).

According to Liu et al. (2006), glacier tourism may meet peoples need for fresh-ness, difference, surprise, and risk. Approaching the glacier, with or without compe-tent guides, indeed meets adventure motivations like opportunities for play (Gyimothy& Mykletun, 2004), tension (Berlyne, 1960), insight (Walle, 1997), increased self-understanding and identity formation (Skarderud, 2001), and risk-taking (Everts,

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 329

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

1989; Geertz, 1973; Martin & Priest, 1986; Weber, 2001); hence glacier tourismopens for multiplex activity-based sensations and experiences.

The Firm: Entrepreneurship and Special Competence Needs

To reduce the frequency of serious accidents and increase the access to glaciers for tour-ists, guided tours are recommended unless the tourist has special competence in“reading” the glaciated formations. In response, guided glacier tourism has been devel-oped in several destinations in Norway and Spitzbergen; hence Norwegian glaciertourism can to some extent frame a “purchasable short-term holiday experience”.The definition of adventure tourism used here is “. . . guided commercial tours wherethe principal attraction is an outdoor activity that relies on features of the naturalterrain, generally requires specialised equipment and is exciting for the tour clients”(Buckley, 2007, p. 1428). The activity itself is not always difficult, but the clientsrely on guides’ expertise to find their way through the glacial landscape. “The guidespossess particular skills or knowledge that either gives the group a more interestingexperience, keeps them out of danger, or commonly both” (Buckley, 2006, p. 458).

Glacier tourism is also an outcome for entrepreneurial work to create organizationalstructures providing and selling glacier tourism as a product. The entrepreneurial rolemay be conceived of as

. . . the agent who creates, recognises and acts on opportunities. This includes usinginnovation to do new things, operating flexibly and adapting to a wider context,working in conditions of risk and uncertainty, achieving change and gainingreward through profit. If entrepreneurship is viewed as a process, it consists ofthe person, the search for market opportunities, innovative behaviour and bringingtogether the resources needed to exploit these opportunities. (Rae, 2007, p. 27)

The special characteristics of the entrepreneurial leader may be similar to religious ded-ication, and entrepreneurial leadership seen as an act of creation (Sørensen, 2008).Researchers have overlooked this side of the entrepreneurship process (Hjorth,Jones, & Gartner, 2008). Entrepreneurial achievements have been explained by individ-ual approaches as a human process caused by personality characteristics (Gibb, 1987),social or cognitive learning processes (Schumpeter, 1934), or as a combination of thetwo (Rae, 2007) drawing connections between organizational learning, opportunity rec-ognition, and creativity (Dutta & Crossan, 2005). Entrepreneurial persons often usetheir creativity to make innovative businesses and seize opportunities others mightfail to see (Getz, 2007), also in social and other forms of entrepreneurship in the“not-for-profit sector” (Dees, 2001; Leadbeater, 1997), and they frequently take risksto pursue their visions (Bass, 1990). Entrepreneurs use their network to gain accessto necessary recourses, such as information, competencies, finances, and support,and consequently become more successful than those without access to such resources(Witt, 2004). Through this “network approach to entrepreneurship” (Bruderl & Preisen-dorfer, 1998), the stakeholders of the organization often become part of the entrepre-neur’s personal network (Johannisson & Mønsted, 1997).

330 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

The Structure of Adventure Tourism Firms

The structure and compositions of various types of adventure tourism firms has beendescribed for diving, rafting, snorkelling, whale-shark watching, crocodile watching,sea turtles, marine tours, and mountaineering and wildlife tours (Buckley, 2007). Healso describes 78 examples of adventure tourism offered as saleable products in relationto their (1) price; (2) duration; (3) accessibility/remoteness; (4) skills; and (5) group sizeand client to guide ratio. He concludes that, although there is a vast diversity in design,price, place, and duration of the tours offered, most adventure tourism activities

. . . have a recognisable commercial signature as measured by duration and priceper person per day . . . The main bulk of the adventure market consists of high-volume low-difficulty products for unskilled clients. The leading edge, in con-trast, consists of low volume, high-costs products which requires prior skills,involve significant risk for clients and operate in more remote and inhospitableareas. (Buckley, 2007, p. 1432)

Adventure at Risk?

As some nature-based tourism activities may be vulnerable to climatic change, one maythink that the tourism operators would be concerned about the future of theirbusinesses, perceiving recession of some of the glaciers as a risk to their business.However, a Finnish study on nature-based tourism entrepreneurs shows that althoughthey are aware of the issue of global climate change, half of the entrepreneurs weresceptic towards climate change and did not believe that it exists, and hence had no adap-tion strategies in place (Saarinen & Tervo, 2006). According to Saarinen and Tervo’s(2006) findings, there may be reason to believe that glacier tourism operators are notconcerned about the potential effects of climatic change on their businesses, and thusdo not see how they should adapt their businesses. When it comes to climate changeeffects on tourism, Aall and Høyer (2005) distinguish between primary and secondaryeffects, where effects due to changes in nature conditions, as may be experienced byglacier tourism operators, are secondary effects. Climate change adaptations caneither be caused by climate policy (explicit), changes in natural resources (implicit),or other changes in and around the industry (Aall & Høyer, 2005). In this study, entre-preneurs seem to differ regarding the future of their adventure.

Method

This study applied mixed methods for data collection (Brewer & Hunter, 1989;Creswell, 2003; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003). These were analyses of company webpages, repeated telephone interviews to glacier tour operators, and participant obser-vation at four commercial tours. Although three research approaches may constitutevalidation and increase reliability of the study (Kirk & Miller, 1986), their main contri-bution was to add different types of information to the study. Second, they were anoption for compiling data from interviews and participant observations, and whendata conflicted, extended research was made until validity was reassured.

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 331

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

The population of existing commercial glacier tourism operators was identifiedthrough a web search starting with the Norwegian Mountaineering Association(Norges Fjellsportforbund), where most of these businesses are members. At theoutset of this study, 17 commercial operators with glacier activities were identified.The population has been more or less throughout the 7-year period; however, onelarge and two smaller operators stopped glacier guiding and smaller operators tookup glacier guiding on a small scale. Hence, there are 20 operators included in thestudy. A semi-structured interview guide based on previous research on adventuretourism and entrepreneurship was developed. The topics covered were year of start-up and visitor data (annual number of visitors, nationality, and way of travel). Regard-ing business operation, the interview considered ownership and management, andwhether the company had local involvement in its ownership.

The next section examined seasonality, number of employees, and their workthroughout the rest of the year in case the company only operated during summermonths. Product information was then sought, focusing on how it had developedalong with its current offers, the issue of having other companies as customers, andthe possible cooperation with other companies. Furthermore, questions consideredtype, content, and amount of interpretation by guides for the visitors, how theproduct had been developed, and type of gear in use. Regarding safety, type of regu-lations, certificates and training required, as well as current practice were examined.Finally, some questions tapped into business image and future development.

Based on this interview guide, telephone interviews were then conducted withglacier tour operation managers, who were usually owners of the operation. Datawere recorded by taking notes. Quantification of the information was applied whereappropriate, and integrated with the qualitative aspects of the research. Interviewswere conducted when most convenient for the respondent, and all respondents werepositive to the research, willing to talk about their products and business development.Further, the facts and opinions were categorized according to the main structure indi-cated by the research statements. No multi-level coding was applied as the questionswere focused on facts and opinions only. This data collection by interviews wasdone first during winter 2004, and repeated during autumns of 2007 and 2009, provid-ing visitor data from the seasons of 2003, 2006, 2007, and 2009.

Fieldwork with participants as observers (Gold, 1958) was undertaken in 2004 and2005 by both authors. It included participation in guided tours, exhibitions, and coursesin glacier walks and glacier climbing. Notes were taken after each activity, and sup-ported by photos. This approach afforded the researcher the opportunity of gettingclose to the activity and research participants’ experiences (Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw,1995), by being part of the context where the activity took place (Fenno, 1978), andto experience firsthand some of the challenges both tourists and operators face in thisunique environment. Another advantage of participant observation is the unobtrusiveway the researcher can collect the data by taking part in the activity (Kellehear,1993). Thus, participant behaviour is more likely to be unaltered (Adler & Adler,1994) because the researcher is regarded as one of the tourists. In retrospect, we seethat interviews with the operators that dropped out of the glacier tourism market alsomay have given valuable information to the study, particularly concerning perceptionsrelated to adaptations and climatic change. In the results section, data sources are

332 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

marked with NOTE for observations, and with BR followed by number(s) when thesource is a business respondent.

Results

Natural Resources and Access

The natural resources used for commercial glacier tourism activities were in close proxi-mity to inhabited areas, mainly old farmland. Hence, they were easily accessible andserved well as optional day and half-day trip destinations for tourists. Most glaciertourism activities took place on the edges of the glacier, such as the glacier arm area.A precondition for glacier tourism is that the glacier front is not too steep or too danger-ous to enter. Since glacier walks occur on the ice surface, the onset of the glacier tourismseason must wait for the winter snow to melt, which covered the ice in winter. Themain season is June to August, but 56% started the season in May and 75% continuetill September, largely depending on weather conditions. Skiing on the snow thatcovered the ice in the winter has a more extended season; however, this is not part ofthe standard glacier tourism product. Access to the natural resource changed, due torecession and growth of glaciers (see subsection current and future challenges below).

The Firm: Entrepreneurship

The oldest commercial company operating today was established as late as 1984 andwas a forerunner for 8 years. From 1992 onwards, the number of companies offeringglacier activities increased gradually, with a peak of five new companies starting upin 1994, up to a total of 17 companies in 2004. This increase in supply has occurredparallel to establishing three glacier visitor centres located around the Jostedalenglacier (Aall & Høyer, 2005) and one Glacier Museum. These companies variedgreatly in structure and size. Most had multiple owners (3–6) who were involved inrunning the company during the summer season. Due to the seasonality of glaciertourism, most owners also had careers as teachers, students, or self-employment, acommon feature being flexible or long summer holidays in their main employment.

Concerning the business life cycle (Butler, 1980), two-thirds of the businesses hadnew ownership, usually one or two owners selling out of the company, and one ortwo new ones buying in. In only one case, ownership had changed totally. Seventy-three percent of the businesses had one or more local owners. Companies withyear-round employment for one or more of the owners operated with other adventureactivities as rock climbing, mountaineering, skiing, kiting, kayaking, rafting, and dogsledging, and offered their products to tourists or arranged courses for certification.“It is a niche, as the segment is too small for us to make money. We have the compe-tence and are still going to offer the product, but our volume is on dog sledging, kayak-ing and rock climbing” (BR9, 2003). “Glacier tourism is an offer for those who want adifferent nature experience, where competence is needed, i.e. clients are buying a safeconcept” . . .“We have three times the volume for kayak activities, which takes less timeto do, require less physical activity and is more accessible. Kayaking is also more suit-able for groups and easier to adjust to clients needs” (BR9, 2009). For others, glacier

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 333

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

tourism was their raison d’etre: “We will continue with the same activity. We know themarket well, and have followed the development. We know what products to offer”(BR4, 2009).

Glacier tourism businesses had a relatively low entry cost, with an average entry costof 50,000 Norwegian Kroner (Norwegian currency, NOK) (6500 EURO), coveringequipment needed for guiding groups. However, some companies started out carefully:“We borrowed equipment for two seasons to see that it was viable” (BR6, 2003). Abouthalf of the companies got public funding to cover start-up costs, but this varies fromregion to region, as one operator said: “Companies in this area have difficulties ingetting external funding, as the activity is very commercial” (BR4, 2003). Whereasanother experienced that: “. . . there are too few tourists in the area to make this businessa living” (BR7, 2003).

Regional differences were also found to be a deciding factor as to whether thenumber of companies was kept stable or not. This is partly due to changes in the gla-ciers: “In this area there are no new operators. However, many companies have reducedtheir activity to a microscopic level” (BR4, 2007). “Competitors still exist, but theyhave changed their activity” (BR1, 2007). “In Jotunheimen there are several new oper-ators in the glacier tourism segment, new single proprietorships, but no new compa-nies” (BR18, 2007).

Also, new companies with diverse products appeared: “Several activity companiespop up. But the Briksdal glacier is now closed due to the reduced glacier area,which makes it difficult to run safe glacier guiding here. This has led to increasedtourism on the Nigard glacier” (BR11, 2007). Most of these activity companiesseemed to tailor events for their clients, rather than dealing with highly commercializedglacier tourism products. “No company has closed that I know. There is a small newcompany that focuses on horse trekking tours to see glaciers” (BR15, 2007).

Special Competence: Safety, Staff, and Training

The operators claimed to be concerned with guide competence and safety: “We demanda mountain guide basic course and a first aid course. During the activity, guides carry afirst aid kit and radio link. They also have to be extroverted and service-minded,friendly and able to pass on knowledge” (BR1, 2003). “Safety is no. 1 priority, aswe guide inexperienced clients with different interests” (BR11, 2003). “Securityissues are met with . . . mainly risk prevention, rescue work and focuses on cracks inthe ice. We cooperate with Red Cross. Use necessary equipment for glacier activities,such as VFM radio, NOD signals and satellite telephones” (BR15, 2009). Risk preven-tion was done through “. . . cutting steps into the ice in advance to limit risks, also polesare used as anchoring” (BR11, 2009).

Operators claimed to have safety as a priority: “We offer ropes, crampons andharness. In addition all tourists are specially insured beyond self declaration; somethingvery seldom in this industry” (BR20, 2009), and: “We focus strongly on safety, and usetwo guides per group, where one is certified. We also focus on equipment needed. It isimportant that the clients don’t perceive high risk, but get a unique experience” (BR9,2009). The operators claimed that accidents were rare: “We do not have accidents,

334 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

although it happens that clients stumble and fall” (BR1, 2003), and not perceived to beserious: “We have had no accidents, only bone fractures” (BR2, 2003).

Although most operators claimed to have trained guides and few accidents, a non-native entrepreneur noted that:

Norwegians and Norway has a special and somewhat naıve approach to glaciertourism. There are few safety requirements, for instance you don’t have to be acertified glacier instructor. Many tourists, in particular foreign tourists take itfor granted that such companies have certified guides. This also applies forother adventure tourism activities in Norway. (BR15, 2009)

Worker requirements were standardized through Norwegian Mountaineering Associ-ation (Norsk Fjellsportforbund), which has compiled standards for training and certify-ing glacier guides. Additionally, most employers looked for staff that showed specialinterest in the glacier area, ones who grew up in the area, and lived there at least inthe summer.

There were no official safety requirements other than those set by the insurance com-panies. “Our guides are certified glacier guides from Norsk Fjellsport Forum, with aminimum of Glacier Instructor Part 1. Plus local knowledge – which is taught intern-ally” (BR3,6, 2003). The educating organizations had different roles. Since 1980 theNorsk Fjellsportforum (Norwegian Mountain Forum/NF) has maintained a nationalstandard for mountain and glacier instructors, guides, and course providers, andpromoted environmentally friendly (sustainable) and safe passages according toNorwegian leisure traditions, securing the diversity and tacit knowledge of glacierguiding. Glacier tourism operators might apply for membership in NF on threelevels, based on whether they were qualified to arrange courses for beginners, instruc-tors, or course leaders. Personal qualification was valid for a 5-year period. In 2009, allbusiness respondents stated that they followed the national standard, and hencerequired the instructor course as a minimum for all guides.

NORTIND (Norske Tindevegledere), the Norwegian Chapter for the InternationalFederation of Mountain Guides Associations (IFMGA/IVBV), provided certificatesto mountain guides following the IFMGA international standard, and also had theresponsibility for organizing, updating, and providing further education for mountainguides in Norway. Mountain guide education includes mountaineering, skiing, moun-tain climbing, glaciers, equipment, and safety and rescue techniques. NORTIND edu-cated only 10 mountain guides every other year. Both organizations listed qualifiedoperators and guides on their web sites. In 2009, three of the respondents preferredthat their glacier guides also were educated mountain guides through NORTIND.

Saleable Packaged Products

The core product for most of these companies was guided tourist walks on the glaciersurface. A safe and comfortable tour for beginners requires skilled guides and specialequipment, as the clients learn on the tour (Buckley, 2007). In addition to the guidefacility, tourist packages typically include equipment, such as crampons, rope, iceaxe, and helmets when the activity includes climbing (NOTE). On some tours, tourists

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 335

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

brought hot drinks and might bring their own lunch, but meals were normally notincluded in the standard glacier tour. However, this seems to be flexible: “There isno meal included, but it is possible if requested. For instance, cruise-ship passengersand groups will usually order lunch” (BR4, 2007). This statement is supported bysix other respondents who said they could serve food if ordered by the clients. Onlyfive respondents said that they never serve food, and four respondents claimed thatfood always is a part of their product.

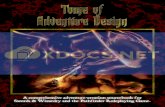

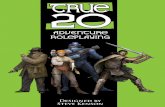

The tour typically started at a meeting point in the parking area, or just below theedge of the glacier. In some cases, there might be a distance to walk or go by boatto the edge of the glacier (NOTE). One respondent claimed that “Most of the visitorshave never been on a glacier before, and have relatively bad basic skills aboutmoving in the kind of terrain we pass on our walk from the car to the glacier” (BR9,2007), but the average customer seems to be adventure-seeking people, not courtingthe extreme. Information was typically offered to tourists before and during thewalk: “Guides are emphasizing skills needed for glacier walks, and informationabout the glacier culture and history, along with climate change issues are importanttopics to address” (BR4,5,6,7,10,11,20, 2009). Another view was: “We basicallyinform about the glacier and the potential dangers. Climate changes are of less impor-tance, as its impact varies from year to year. We mention the changes as a part of thenormal development” (BR9, 2009) (Figures 2 and 3).

Before entering the glacier arm area, equipment was adjusted to the participants.Everyone was hooked on to the rope, got into their crampons, put on helmet andgloves, learned how to carry and use the ice axe, and handle the rope. If anotherperson fell into a crack in the ice, the remaining should just hold on to the rope tosecure the fallen person. It creates a feeling of transformation towards becoming anadventurous person. When on ice, the walk passed into iced mountains and cracks ofblue ice, ice caves, arches, and tunnels, brilliantly blue in colour, combined withflatter wider areas with snow on top. The landscape changed as one passed by, andmovements in the ice produced unique sounds that blended in with the uniquesounds from the crampons crushing the ice. Although the walk was slow and did notrequire high-order physical skills, the ice was unfamiliar for most visitors, and henceinaccessible when on their own (NOTE). “We offer glacier walks for clients whowouldn’t be able to manage on their own” (BR6, 2009). Two important considerationswhen developing products are (1) the time needed for getting an experience and (2)what is physically feasible (BR1, 2003). There has been a slight change in the coreproduct over the 7-year period. Other views were “All tours are arranged for beginners,tours could be customized to experienced clients” (BR4,11, 2009). “We focus onexperience and the feeling of mastery . . . Unique experiences in the unknown” (BR9,2003).

Glacier tourism marketing was directed at average people who love nature and wantto be in the great outdoors. For most companies, it seemed important to stress thatglacier tourism was not an extreme sport, but an exotic, family-friendly activity:“We want to tell that you do not need extreme skills . . . It’s supposed to be exiting,but not extreme” (BR6, 2003). Another stated that glacier tourism is: “. . . a scenicexperience in a special element. Often they are here for the first and last time.Foreigners come here to find peace and tranquillity” (BR11, 2003). Focusing on a

336 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

long-built tradition, “. . . we want to offer leisure activities due to Norwegian traditions,and make products that fit the customers; hence we offer good outdoor experiences withgood service in focus” (BR5, 2003). “We want to . . . make people open their eyes to theelements surrounding us, and make lasting memories. – We focus on sustainable use,not consumption” (BR10, 2003).

Taking part in guided tours is not too difficult as the clients may rely on guides’expertise to find their way through the glacial landscape; however, making this

Figure 2. Boots, crampons, solid clothing, and attached to the rope (private photo).

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 337

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

element accessible to “everybody” requires preparations of the planned route andknowledgeable guides who are good at interpreting the changing surroundings(NOTE). The client2guide ratio differs from company to company, and seems to besubject to change: “We have 12 clients per guide, but are increasing the number ofguests now as we have not had any accidents” (BR1, 2003). On the other hand, oneoperator stated that: “. . . as the glacier is melting, we have fewer clients per guide.The glacier is less accessible, the passages are narrower, the snow layer melts, it issteeper and we need more time” (BR10, 2003).

There is certain variability in products offered. One of the few companies withincrease in number of visitors offered glacier kayaking, i.e. kayaking in one of theglacier lakes at the terminal face as their main product. “When developing theproduct, we started from the standard made by the Norwegian MountaineeringAssociation and NORTIND procedures, which is a solid foundation” (BR5,2003). On the other hand, one operator said “we started to copy others, buthave now adapted to the surrounding area. We offer regular tours” (BR3, 2003).As not all tourists to the area took part in commercial adventure tourism, somecompanies diversified to embrace a larger segment: “New products are developed.We adapt to fit clients’ demands. We have now made a nature trail, which is forfree” (BR3, 2007).

The product per se was very dependent on the interaction between the guide and theclients, as: “Guiding and knowledge dissemination is what we do . . .” (BR9, 2007).

Geology, history, climate and general learning . . . all elements are important,geology and knowledge about the glacier; its distinctive historical development.For glacier tourism, some learning about climate and challenges are elementary,as one of the owners of this company is a climate researcher. The history of theglacier is an important element of the tour. (BR3, 2009)

Figure 3. Participants prepared for the guided glacier walk (private photo).

338 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

Although there seemed to be no fixed relation between price and duration, operatorsincreasingly offered fairly similar products and prices. Due to recent melting of theice on some glaciers, accessibility had changed in some of the main tourism areaswhich required more time to reach the glacier. This led to day trips replacing shortertrips. The average price in 2009 for a 1-day (6 h) glacier experience was approximately600 NOK (77 EURO), whereas some companies also offered shorter trips (2–3 h) withthe average price of 370 NOK (47 EURO). There has only been a small increase inprices over the 7-year period. Many of the companies also tailored guided glaciertours for groups travelling with bus or cruise ships, and for company customers.Also available were overnight tours, glacier courses, glacier-guide courses, andprivate guiding. Therefore, “. . . price is calculated for each tour. For firms weoperate with a total amount, while individuals pay per head” (BR5,12,13,16, 2003).“We offer high quality at a very affordable price. – Available and feasible foranybody” (BR15, 2003).

Demand and Volume

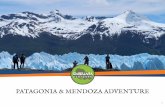

Five of the operators handled more than 1000 tourists per year. The rest dealt with30–650 per year. In 2003, there were three companies handling 7000–8500 touristseach, and two companies handling 2800 and 4000 clients, respectively, while in2009 there was only one large company handling almost 9500 clients, one handling4000 clients, and three handling 1300–1700 clients each. In 2003, a total of about32,000 tourists took part in glacier tourism activities in Norway (see Figure 4).Three years later, the number had dropped by 23%, followed by another drop theyear after. The overall decrease in activity mainly seems to be due to change in theglacier formation as mentioned by the hardest hit companies: “We had an enormousdecrease due to glacier melting. In 2007 we’ve had 200 clients, compared to 2000 in2006”, and “. . . there has been a change in operation and service production. About70 percent of our main activity disappeared. We were using the Briksdal glacier”(BR1, 2007, West Coast). Other companies had moved to other areas that have been

Figure 4. Numbers of participants in glacier tourism activities, 2003–2009.

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 339

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

more stable: “We’ve changed the operation, logistics and safety, and are now operatingon another glacier” (BR4, 2007).

From 2007 onwards the total number of glacier tourists had been more or less stable,with considerable growth for some companies and a small decline for others. The mainoperator in Northern Norway has increased the activity: “We’ve had an increase thisyear. We operate on the only glacier in the area, and have arranged tours every dayat 12 h” (BR14, 2007) (Figure 5).

The guest mix varied across companies, mainly depending on the tourist flow in thearea in which they were operating. The Briksdal area had about 300,000 tourists peryear, whereof 3–4% took part in a commercial glacier activity. In Jostedalen, about10% of visitors bought a guided glacier tour, as the customer segment was different.Most of the larger companies claimed to have a mix of 50/50 of individual guestsand organized groups. Individual customers often came in couples, and travelled bytheir own means of transportation. About 60% were foreigners, mainly German,Dutch, or British. There had been increases in German visitors from cruise ships,and in Spanish groups travelling by bus. Most companies had a lower age-limit of12 or 13 years, but underlined that there was adventure seeking by all age groups.One company claimed to have “. . . younger and fitter tourists than other companies”(BR1, 2003), and another company had “. . . clients that were adventure seeking back-packers” (BR2, 2003). Very few of the clients (20–25%) had previous glacierexperiences.

Current and Future Challenges – Risks for Glacier Tourism

Some of the entrepreneurs expressed uncertainty regarding the future of their business.Among the reasons mentioned were: change in demand, change in accessibility to the

Figure 5. For the advanced – climbing in the cracks of the glacier (private photo).

340 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

nature resources due to glacier retreat, and hard to find a successor for a small-scale firmwhen retiring.

Depending upon the geographical area of their operation, the operators held differentviews on how climate changes might affect the state of the glaciers and consequentlytheir businesses. In 2003, 10 of the 17 respondents expressed no concern for meltingglaciers. Two of these operated in an area where the glacier had grown over therecent years. On the other hand, six respondents expressed moderate concerns regard-ing the development of the glacier; two of them were already looking for alternativeglacier areas to operate on:

The glacier is melting for the third year on a row. It is not dramatic, but if con-tinued, it might become a problem. Today it is easily accessible, but due to thechanges we are looking for alternative glaciers to guide on, as accessibilitymight become more difficult. (BR1, 2003)

In 2007, 8 out of 17 respondents expressed no worries about the recent recession of theglaciers; however, one of the glaciers was closed for tours due to melting and reducedaccessibility:

We are not worried at all. Long ago there wasn’t even a lump of ice here. Theglacier grows and withdraws, in 1960 and 1990 it was the same size. It is astrong focus on melting, but the future of glaciers is dependent on the precipi-tation. (BR14, 2007)

Some operators coped with this threat in a phlegmatic style: “There is some hysteriaconcerning climate change. But no, I am not immediately worried” (BR8, 2007).Many others shared this view:

We are not worried. Environment and climate change is a topic of conversation onevery tour, because of own interest, observations over time, and because theseissues are on the minds of our guests. But we are not worried for the future forthat reason. (BR20, 2007)

The future for the company is quite solid. We are happy with what we have. Wehave been expanding for five years. The climate and global warming and how itaffects Norway – we will have to wait and see what happens. (BR15, 2007)

Seven of the respondents expressed serious concern about recent changes, suggestingthat ice melting may cause considerable challenges for some operators, forcing them towork in new geographical areas or diversifying into other adventure activities. “We willdevelop more mountain walks, due to the recession of the ice” (BR1, 2003). In total,this change caused a dramatic reduction in clients, as it affected two of the largest oper-ators. A controversy exists as to whether the ice melting is due to local weather patternsor climate change. In the ensuing years, the melting continued in some areas, seriouslychanging access to the natural resources for some operators:

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 341

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

The glacier became inaccessible, too steep. Hence we changed to another glacierin 2007. Our company had the choice of reducing activity or moving to anotherglacier. Now we are also offering an activity park, which is a success. Due todiversification into rafting activities, we only had a small decrease in turnoverfrom 2006 to 2007. (BR4, 2007)

Some operators saw changes with a more long-term perspective: “. . . not short term, butour activities are climate vulnerable. As the temperature increase more than normal, thismay become a future problem due to ice melting and recession of the glacier” (BR11,2007).

Having guided since the 80s, I see a radical change in the nearby glaciers, and thisis a natural topic of conversation on our tours. Our guests get visible evidence ofclimate change, and I see changes from tour to tour, even in a few days. (BR9,2007)

“There are clear indicators on the glacier that it is warmer. There has been a great reces-sion and that’s not nice” (BR1, 2007). “We see that the glaciers are disappearing, andare a bit worried, but not within a 10-year perspective. In 30 years they will probablydecrease more” (BR7, 2007).

Discussion and Conclusions

Natural Resources and Access

Few of the Norwegian glaciers are used for adventure tourism by the 17 commercialoperators identified in this study. The activities are based mainly in the “glacierarms”; the parts of the glaciers stretching down into the adjacent valleys. These partsare used for adventure tourism and are in proximity to roads and farmed areas, andhence within reach for daytrips, and equipment needed may easily be brought up tothe front of the glacier. However close, accessibility may be difficult because of theice melting which changes the shape of the glacier. Full- and half-day tours are mostfrequent, but “expeditions” for several days with tents are available. Visitor centresand a glacier museum has been erected to extend the glacier experience also to themajority of visitors approaching them to see and sense the unique glacier ambience,without actually taking part in the excursions on the glacier surface.

Entrepreneurship

Although glacier tourism is old, the longest running operator registered the business in1984. After a peak year in 1994, the entrepreneurial endeavours continue. Glaciertourism operators in Norway are small, locally owned firms in the backcountry andrarely visited areas, with a short operation history. They are locally owned byseveral partners, and the partners have changed over the years, but the entrepreneurusually stays with the operation. More than half the businesses are seasonal; the remain-der offer other mountain tourism products during the off-season. The majority have

342 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

other main incomes in positions and branches that allow them to spend summer monthsin glacier tourism activities. The business may be a life-style issue for some pretendingto be entrepreneurs – “pretentrepreneurs”, while for many it provides a significantsource of extra or even their main income. The onset of the businesses was oftenmade with public funding, while others started borrowing equipment from establishedoperators and hence went more reluctantly into their operations. In most cases, access tonetworks was an important prerequisite for the development.

Competence and Safety

Several types of competences are required to start a glacier tourism operation, such asunderstanding the structure and dynamics of the glacier in use, insight into tourism as aphenomena and business area, operational skills relevant to the logistics of the glacierwalk activities, and the economical and other management issues of the company.Being brought up with the glaciers in their neighbourhood and experienced in traver-sing them, tacit knowledge (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995) accounted for most of theskills in the adventure part of the business. The observed changes in ownership mayindicate, however, that entrepreneurial skills may have been stronger than the oper-ational and business skills. When asked, the operators were most concerned aboutthe guides’ competence and how qualifications should be attained, and trainingcourses to cater for this demand.

No serious accidents have been reported within glacier tourism, indicating a suffi-cient level of competence and security measures. Operator and guide competence isone of the crucial factors in reducing accidents. Similar to Buckley (2007), intervie-wees report that client-to-guide ratios are determined by risk, difficulty, and skillrequirements, and hence the number of tourists per group may be subject to change.Other important factors are equipment, weather condition, and fitness, skills andawareness of the participants, and interactions among these variables may multiplythe likelihood that accidents will happen (Bentley, Page, Meyer, Chalmers, & Laird,2001; Bromiley & Curley, 1992; Yates & Stone, 1992). However, one cannot comple-tely eliminate the risk without destroying the adventure (Greenaway, 1996), as risk,danger, and adrenaline may be central to the definition of adventure (Kane &Tucker, 2004).

The Experience, Packaging, and Product Development

The glacier experience is unique; an indisputable “otherness”, educational, and scaringto most first time visitors. Participation in guided glacier tours is safe, however, but thefear remains in the perception of the visitors. It provides the tourist a “hands-on” experi-ence with the accelerated sublime; hence the product qualifies as an adventure, trigger-ing the Ulysses motivation. The tour moves towards the glacier front, with the changein temperature and light and sounds, to take on the unique outfit and line up in the ropewith the ice axe in one hand and the other on the rope mark a transition (Pine &Gilmore, 1998) into being an adventurer or mountaineer (Beedie & Hudson, 2003).It gives a strange feeling of being slightly different, daring and powered by thegroup, the guide and the outfit, and especially the rope, the axe, and the crampons.

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 343

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

Improvements might be made by having the guide accelerating the transition throughpresenting facts about the dangers of the glaciers, the devastating events that have hap-pened as a process, their history and tremendous power in shaping landscapes, andenhance participants’ immersion (Pine & Gilmore, 1998) into the activities. Althoughadventurous, the activity itself should be considered a soft adventure (Beedie &Hudson, 2003), as the risk is highly reduced through competent guides.

The dominant products in 2009 were short walks (2–3 h, NOK 370/47 EURO) andday trips (6 h, NOK 600/77 EURO), and hence to be found in the lower price and dur-ation range when compared to Buckley’s (2007) categorization of adventure tourismproducts. The diversity of glacier tourism product has been reduced since 2003, asshort 1–2 h tours are not offered anymore. This is claimed to be due to changes inthe glacier fronts and surface, related to recession of the largest glaciers.

Most visitors are inexperienced and unfamiliar with the glacier environment, andhence clients are dependent on qualified guides when they participate in a glacieractivity, and necessary skills are learned on tour. This provides an opportunity forguides to talk about sustainability, climate changes, and effects on the glaciers,which is only used to some extent, leaving much room for improvement.

Glacier tourism is marketed as a low-entry adventure activity for outdoor-lovingpeople, but still as an exotic and scenic experience. This is similar to the results reportedby Buckley (2007, p. 1432), who stated that “the main bulk of the adventure marketconsists of high-volume low-difficulty products for unskilled clients”. There hasbeen a growing trend in the industry towards tourists seeking multiple soft adventureactivities, rather than hard adventure activities, focused on one activity per trip(Sung, Morrison, & O’Leary, 2000). Further product developments are possible withnew products added to the glacier walks, like serving “glacier meals”, storytelling,and educational programmes on glaciers, landscape, and climate changes. An increasein operations would most likely influence the demand side, granted adequate marketing.

Demand and Volume

Glacier tourism is a modest adventure tourism segment, with approximately 20,000visitors per year (2009). Over the study period, 2003–2009, a 30% reduction invisitor numbers and operators was observed. Changes in two of the important precon-ditions, namely, natural resources and access, have forced some of the operators tochange location or mode of operation. These changes may have indirectly affectedboth demand and volume. Demand may be linked to the type of products offered:When, in 2003, access to the glacier surface was made more difficult, the guidedtours had to be extended to get the same amount of time on ice. If more time isneeded for this type of adventure, some types of tourists may lose interest due to exter-nal factors such as travel companions, transport, etc.

As few glaciers have been used for adventure tourism so far, there should be room forconsiderable amount of product development in the form of new operations in otherlocations. This would require new entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial networks, andshortages of such resources may account for the fact that reduction in activities inthe observed operations has not been compensated by new operations. However, in2010, several one-man firms also registered within this niche, and the official

344 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

webpage visitnorvay.com which promotes glacier tourism is also listing new providers,possibly a response to the observed reduction in the glacier tourism niche.

The Future of Glacier Tourism in Norway

Historically, glaciers have grown and recessed interchangeably (Orheim, 2009; Vorrenet al., 2007). Such changes have also been reported during the 7-year period of thisstudy. Recession particularly changes the front of the glacier; hence it might becomesteeper and more dangerous to enter. As a consequence, some operators havereduced their glacier activities, moved to other parts of the glacier, or diversifiedtheir products into other adventure and nature-based activities. The operators tosome degree blame this on climate change, but most of them are upbeat regardingthe future of their business over a 10-year period, as they regard the development ofthe glacier to be more dependent upon local precipitation and summer temperatures,rather than upon climate changes. These findings are in line with Saarinen and Tervo(2006), who found that nature-based tourism entrepreneurs were sceptical aboutclimate change and the potential effects on the industry, and thus focused on whatthey perceived as normal weather variations and market changes. The scepticismabout climate change may explain the fact that there were almost no adaptation strat-egies reported.

One reason why Norwegian glacier tourism operators do not feel that climate changeis a threat may be because the effects they have experienced are secondary effects.A somewhat similar adaptation to changes in nature conditions due to climaticchanges has also been observed by Aall and Høyer (2005). These authors make a dis-tinction between primary and secondary climate change effects, where the changesexperienced by glacier tourism operators; namely, changes in nature conditions trig-gered by climatic changes, are secondary, and thus less obvious and possibly relatedto other causes.

Ongoing melting of glaciers in Central Europe might give a competitive advantage toNorwegian glacier operators. If glacier tourism is less accessible in Europe, the Norwe-gian glacier tourism product may seem more appealing. Although Agrawala (2007)points out that climate change is a threat to tourism in the European Alps, wintertourism seems to be more at stake than summer tourism. In spite of the decreasingnumbers of visitors, operators in this niche are not pessimistic about the future oftheir businesses. They are confident that the glaciers will remain, although there willbe constant challenges due to changing ice conditions and access to the glacier.Increased marketing from the Norwegian Tourism Board and the observed increasein registered operators in 2010 might indicate a growing interest and awareness ofthe unique value of glaciers as a natural tourism resource.

References

Aall, C., & Høyer, K.G. (2005). Tourism and climate change adaptation: The Norwegian case. In C.M. Hall& J.E.S. Higham (Eds.), Tourism, recreation and climate change (pp. 209–221). Clevedon Buffalo:Channel View.

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 345

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

Adler, P.A., & Adler, P. (1994). Observational techniques. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.),Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 337–392). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Agrawala, S. (2007). Climate change in the European Alps: Adapting winter tourism and natural hazardsmanagement. Paris: OECD.

Anderson, J.R.L. (1970). The Ulysses factor. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.Bass, B.M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theroy, research and managerial appli-

cations (3rd ed.). New York, NY: The Free Press.Beedie, P., & Hudson, S. (2003). Emergence of mountain-based adventure tourism. Annals of Tourism

Research, 30(3), 625–643. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00043-4Bell, C., & Lyall, J. (2002). The accelerated sublime: Landscape, tourism and identity. Westport, CT:

Praeger.Bentley, T., Page, S., Meyer, D., Chalmers, D., & Laird, I. (2001). How safe is adventure tourism in New

Zealand? An exploratory analysis. Applied Ergonomics, 32, 327–338.Berlyne, D.E. (1960). Conflict, arousal, and curiosity. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.Breboka. (1999). Handbok i brevandring [Glacier walking handbook] (5th ed.). Oslo: Den Norske

Turistforening [Norwegian Mountaineering Association].Brewer, J., & Hunter, A. (1989). Multimethod research – a synthesis of styles. Newburry Parks, CA: Sage.Bromiley, P., & Curley, S.P. (1992). Individual differences in risk taking. In P. Bromiley, P.S. Curley, &

J.F. Yates (Eds.), Risk-taking behavior. Wiley series in human performance and cognition(pp. 87–132). Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Bruderl, J., & Preisendorfer, P. (1998). Network support and the success of newly founded businesses.Small Business Economics, 10, 213–225.

Buckley, R. (2000). Neat trends: Current issues in nature, eco- and adventure tourism. International Journalof Tourism Research, 2(6), 437–444. doi: 10.1002/1522-1970(200011/12)2:6<437::AID-JTR245.3.0.CO;2-#

Buckley, R. (2006). Adventure tourism. Wallingford, CT: CABI.Buckley, R. (2007). Adventure tourism products: Price, duration, size, skill, remoteness. Tourism

Management, 28(6), 1428–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2006.12.003Butler, R.W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area life cycle of evolution: Implications for management of

resources. Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.xCreswell, J.W. (2003). Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988). The flow experience and its significance for human psychology. In M.

Csikszentmihalyi & I.S. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), Optimal experience. Psychological studies of flowin consciousness (pp. 15–35). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dees, G.J. (2001). Enterprising nonprofits: A toolkit for social entrepreneurship. New York, NY: Wiley.Dutta, D., & Crossan, M. (2005). The nature of entrepreneurial opportunities: Understanding the process using

the 4l organisational learning framework. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 29(4), 425–449.Emerson, R.M., Fretz, R.I., & Shaw, L.L. (1995). Writing etnographic fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: Chicago

University Press.Everts, A. (1989). Outdoor adventure pursuits: Foundations, models and theories. Columbus, OH:

Horizons.Fenno, R. (1978). Notes on methods: Participant observation. In R. Fenno (Ed.), Homestyle. House

members in their districts (pp. 249–295). Boston, MA: Little, Brown.Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books.Getz, D. (2007). Event studies. Theory, research and policy for planned events. Oxford: Butterworth-

Heinemann (Elsevier).Gibb, A. (1987). Enterprise culture. Its meaning and implications for education and training. Bradford:

MCB University Press.Gold, R.L. (1958). Roles in sociological field observations. Social Forces, 36, 217–233.Greenaway, R. (1996). Thrilling not killing: Managing the risk tourism business. Management, May,

46–47.Gyimothy, S., & Mykletun, R.J. (2004). Play in adventure tourism: The case of arctic trekking. Annals of

Tourism Research, 31, 855–878. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2004.03.005

346 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

Hall, C.M., & Higham, J.E.S. (2005). Tourism, recreation, and climate change. Clevedon Buffalo: ChannelView.

Hallin, C.A., & Mykletun, R.J. (2006). Space and place for BASE: On the evolution of a BASE-jumpingattraction image. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 6(2), 95–117. doi: 10.1080/15022250600667466

Hjorth, D., Jones, C., & Gartner, W.B. (2008). Introduction for recreating/recontextualising entrepreneur-ship. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24(2), 81–84.

Johannisson, B., & Mønsted, M. (1997). Contextualizing entrepreneurial networking. The case ofScandinavia. International Studies of Management and Organisations, 27(3), 109–136.

Kane, M.J., & Tucker, H. (2004). Adventure tourism: The freedom to play with reality. Tourist Studies,4(3), 217–234. doi: 10.1177/1468797604057323

Kellehear, A. (1993). The unobtrusive observer. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.Kirk, J., & Miller, M.L. (1986). Reliability and validity in qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Leadbeater, C. (1997). The rise of the social entrepreneurs. London: Demos.Liu, X., Yang, Z., & Xie, T. (2006). Development and conservation of glacier tourist resources – a case

study of Bogda Glacier Park. Chinese Geographical Science, 16(4), 365–370. doi: 10.1007/s11769-006-0365-y

Mandal, F., Lura, C., Bordvik, M., & Børhaug, A. (2010, August 6). Her renn flaumvatnet [Flood watereverywhere]. Bergens Tidende. Retrieved August 6, 2010, from http://www.bt.no/nyheter/lokalt/Fryktar-storflaum-1131027.html

Martin, P., & Priest, S. (1986). Understanding the adventure experience. Adventure Education, 3, 18–20.Mayo, E.J., & Jarvis, L.P. (1981). The psychology of leisure travel: Effective marketing and selling of travel

services. Boston, MA: CBI.Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the

dynamics of innovation. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.Orheim, O. (2009). Norske isbreer [Norwegian glaciers]. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.Pine, B.J., & Gilmore, J.H. (1998, July–August). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business

Review, 76(4), 97–105.Rae, D. (2007). Entrepreneurship: From opportunity to action. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.Rønningen, S.S. (2010, August 20). Norges 1627 isbreer dør. Det haster for dem som vil oppleve den siste

istid [Norway’s 1627 glaciers are dying. Those who want to experience the last ice age should hurryup]. Dagens næringsliv, 6–17.

Saarinen, J., & Tervo, K. (2006). Perceptions and adaptation strategies of the tourism industry to climatechange: The case of Finnish nature-based tourism entrepreneurs. International Journal ofInnovation and Sustainable Development, 1(3), 214–228. doi: 10.1504/IJISD.2006.012423

Schumpeter, J. (1934). The theory of economic development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Simmel, G. (1971). The adventurer. In D. Levine (Ed.), On individuality and social forms (pp. 187–188).

Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.Singh, T.V. (2004). Tourism searching for new Horizons: An overview. In T.V. Sing (Ed.), New horizons in

tourism. Strange experiences and stranger practices (pp. 1–10). Wallingford, CT: CABI.Skarderud, F. (2001). Uro. Oslo: Aschehoug.Slingsby, W.C. (1904). Norway: The Northern playground. Edinburgh: D. Douglas.Sørensen, B.M. (2008). “Behold, I am making all things new”: The entrepreneur as savior in the age of crea-

tivity. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24(2), 85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2008.03.002Sung, H.H., Morrison, A.M., & O’Leary, J.T. (2000). Definition of adventure travel: Conceptual framework

for empirical application from the providers’ perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research,1(2), 47–67.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Vorren, T., Mangerud, J., Blikra, L.H., Nesje, A., & Sveian, H. (2007). Norge av i dag trer fram. In I.B.Ramberg, I. Bryhni & A. Nøttvedt (Eds.), Landet blir til. Norges geologi [Norway’s geology](pp. 532–555). Trondheim: Norsk Geologisk Forening.

Walle, A.H. (1997). Pursuing risks or insight: Marketing adventures. Annals of Tourism Research, 24,265–282. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(97)80001-1

Norwegian Glacier Tourism 347

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012

Weber, K. (2001). Outdoor adventure tourism: A review of research approaches. Annals of TourismResearch, 28(1), 360–377. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00051-7

Witt, P. (2004). Entrepreneurs’ networks and the success of start-ups. Entrepreneurship & RegionalDevelopment, 16, 391–412.

Wold, B., & Ryvarden, L. (1996). Jostedalsbreen: Norges største isbre [Jostedalsbreen: Norway’s largestglacier]. Oslo: Boksenteret forlag.

Yates, J.E., & Stone, E.R. (1992). The risk construct. In J.E. Yates (Ed.), Risk-taking behavior (pp. 1–25).Chichester: Wiley.

348 T. Furunes & R. J. Mykletun

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

itets

blio

teke

t] a

t 01:

26 1

8 D

ecem

ber

2012