“From the Author to the Proprietor: Newspaper Copyright & The Times (1842-1956)” Journal of...

Transcript of “From the Author to the Proprietor: Newspaper Copyright & The Times (1842-1956)” Journal of...

This article was downloaded by: [86.144.236.213]On: 26 May 2015, At: 09:05Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH,UK

Click for updates

Journal of Media LawPublication details, including instructions for authorsand subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjml20

From the Author to theProprietor: Newspaper Copyrightand The Times (1842–1956)Jose Bellidoa & Kathy Bowreyb

a Jose Bellido, Kent Law School, University of Kent,UK;b Kathy Bowrey, Faculty of Law, University of NewSouth Wales, Australia. Thanks to Nick Mays, AnneJensen, Rick Watson, Karen Jacques, Eugene Rae,Patrick Russell, Anita de Silva, Charles Mathew, PeterPutnis, Andrea Waterhouse and John Entwistle forfacilitating access to various archives and sharingtheir knowledge. Nathan Moore, Cara Levey andDavid Lobenstine kindly read and commented onprevious drafts. Thanks to Jennifer Kwong for researchassistance. This work was presented in a workshopat Kent Law School organised by Emilie Coaltrie andMartyn Pickersgill and at a seminar led by RobertBurrell at Sheffield University. We would also liketo express our gratitude to them, to the anonymousreviewers at the Journal of Media Law and to EricBarendt for their suggestions.Published online: 07 May 2015.

To cite this article: Jose Bellido & Kathy Bowrey (2014) From the Author to theProprietor: Newspaper Copyright and The Times (1842–1956), Journal of Media Law, 6:2,206-233

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.5235/17577632.6.2.206

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all theinformation (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform.However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make norepresentations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, orsuitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressedin this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not theviews of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content shouldnot be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions,claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilitieswhatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connectionwith, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expresslyforbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

ARTICLES

From the Author to the Proprietor:

Newspaper Copyright and The Times (1842–1956)

Jose Bellido and Kathy Bowrey*

This article explores a major transformation in newspaper copyright that aided the emergence of modern media markets. Part 1 examines the legal foundation of news copyright in the Copyright Act 1842 (UK). Despite legislative inclusion, there was uncertainty as to the legality of news copyright through most of the nineteenth century. Furthermore, contrary to conventional wisdom, we argue that the landmark decision of Walter v Lane (1900),1 which confirmed the reporter’s right to their literary works, did little to assist newspaper proprietors in securing a sound commercial foundation for their enterprise. In Part 2, we show how the reporter’s right was difficult to reconcile with newspaper management practices and how it tended to frustrate the commercial ambitions of proprietors intent on expanding markets and opportunities. Part 3 then explores the creative role played by managers at The Times and key legal personnel in devising ‘workarounds’ in order to reimagine copyright, freeing it in practice from the previous limitations of the author model. It is argued that copyright, contract and new accounting systems worked together to reconstruct copyright as a proprietor’s right. Part 4 demonstrates how this broad-based proprietor’s right was then deployed in order to deliver expectations of exclusive control over channels of media distribution, allow-ing for serialisation and syndication of copyright ‘matter’ across time and space. Part 5

* Jose Bellido, Kent Law School, University of Kent, UK; Kathy Bowrey, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales, Australia. Thanks to Nick Mays, Anne Jensen, Rick Watson, Karen Jacques, Eugene Rae, Patrick Russell, Anita de Silva, Charles Mathew, Peter Putnis, Andrea Waterhouse and John Entwistle for facilitating access to various archives and sharing their knowledge. Nathan Moore, Cara Levey and David Lobenstine kindly read and commented on previous drafts. Thanks to Jennifer Kwong for research assistance. This work was presented in a workshop at Kent Law School organised by Emilie Coaltrie and Martyn Pickersgill and at a seminar led by Robert Burrell at Sheffield University. We would also like to express our gratitude to them, to the anonymous reviewers at the Journal of Media Law and to Eric Barendt for their suggestions.

1 Walter v Lane [1900] AC 539.

(2014) 6(2) JML 206–233DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5235/17577632.6.2.206

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

207From the Author to the Proprietor

reflects on how the eminent barrister and advisor to The Times, AD Russell-Clarke, fur-ther instructed on how to shore up this reconstructed copyright, with a view to revising contracts to secure a firmer legal foundation for the enterprise. The article draws heavily on original internal correspondence from The Times and other archival sources.

In copyright historiography it is commonplace to consider the evolution of leg-islative rights and in particular the theoretical importance of the author, leaving consideration of commercial practice to business and media history. We consider that this creates a misleading picture of the role of law in the media industry. Conventional copyright historiography often buys into positivist fantasies about the importance of copyright law ordering economic life, ignoring the reality of law in practice. Business and media history, without serious consideration of the role of law, tends to construct a simplistic instrumental view of power, ignoring how commercial practice is informed by and develops in response to legal technicalities. We conclude by arguing that, in writ-ing copyright history, there is a need to consider primary sources and corporate records more closely to better understand how copyright is reimagined and renewed in practice, and how, in turn, practice affects our understanding of legal concepts such as authorship. It is only with reference to more diverse sources that we can elucidate the ways in which the law connects and is constructed in relation to commercial realities and how together, both law and practice operate to reinvent copyright and satisfy the proprietor’s projects for market expansion.

1. ThE NINETEENTh CENTURy

(a) Copyright in Newspapers

The Copyright Act 1842 provided copyright protection for newspapers as ‘books’2 and as ‘periodical works’.3 however, what copyright did these provisions confer on the proprie-tor, separate to any rights owned by the employee journalist or independent contractor who had assigned rights to a particular literary work to the proprietor? historically liter-ary property was understood to be both an author and a publisher’s right, with the term originally running from the date of publication of the work in the United Kingdom.4

2 s 2 Copyright Act 1842 (5 & 6 Vict c 45) defined ‘book’ as including every ‘sheet of letterpress’, which was taken to include editions of newspapers and articles in newspapers.

3 s 18 Copyright Act 1842 provided: ‘When any publisher or other person shall … have projected, conducted, and carried on … any encyclopaedia, review, magazine, periodical work, or work published in a series of books or parts, or any book whatsoever, and shall have employed … any persons to compose the same, or any volumes, parts, essays, articles, or portions thereof, for publication in or as part of the same, and such work … shall have been composed on the terms that the copyright therein shall belong to such proprietor … and paid for by him, such proprietor … shall be entitled to copyright.’ Section 19 entitled the proprietor to sue following registration at Stationer’s hall in accordance with the requirements of s 13.

4 Walter Arthur Copinger, The Law of Copyright: In Works of Literature and Art (Stevens & haynes, 1st edn 1870) 58–59.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

208 Journal of Media Law

Under the Act, however, if the proprietor relied upon a claim to copyright in the news-paper or a particular article as a ‘book’, every edition needed to be registered.5 If the proprietor relied upon copyright in periodical works, it was not necessary to register every edition. however, in both cases it was necessary to register prior to bringing suit.6 As we will see shortly, this turned out to be a very clumsy arrangement, ill-suited to the realities of newspaper production.

What copyright did the proprietor actually own under the masthead, separate to a right to the discrete articles published within a particular edition? The practicalities of production varied greatly from the simple transactional model imagined by the legisla-tion. In Platt v Walter (1867)7 the common practice of republishing works from morning newspapers in evening editions came under scrutiny. The problem of conceiving of the publisher’s right beyond any authorial right to particular content that originated with the journalist very much vexed the courts.

John Walter the Elder established The Times in 1785.8 A companion newspaper, the Evening Mail, was first published in 1789. It was described as ‘a republication on the evenings of the Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, in each week, of the matter (other than advertisements) contained in the two preceding numbers of The Times, with such omissions and abridgments as were considered desirable’.9 Both papers were printed at Printing house Square. As various members of the Walter family came to work on the titles, the practice was for part-shares to be drawn in their favour. This eventually led to the creation of 31 part-ownership shares in the Evening Mail, generally conditional on grant or purchase back to the proprietor. While not all shares remained within the Wal-ter family and those that married in it, they maintained control of the ownership. This meant that there was no problem with republishing works from one edition in the other, as ownership was concentrated in one set of hands, notwithstanding the underlying copyrights deriving from multiple sources. Further, it also facilitated the practicalities of newspaper production, including sharing the lead type in order to enable efficient reprinting in later editions.

however, on more than one occasion part-shares in the Evening Mail were sold to a London solicitor, Thomas Platt (1760–1842), with the consent of the proprietor, presumably in order to raise finance. These transactions did not include any formal arrangements, allowing for the practice of coming to Printing house Square and repub-lishing from The Times to continue. After Platt’s death, his family members inherited his shares. And after repeal of the paper duty in 1861, Mr John Walter III decided that

5 Dick v Yates [1881] 18 Ch D 76.6 For registration requirements for newspapers see Walter Arthur Copinger and James Marshall Easton, The

Law of Copyright: In Works of Literature and Art (Stevens & haynes, 4th edn 1904) 246.7 Platt v Walter (1867) 17 LT (NS) 157.8 The Times was founded as The Daily Universal Register in 1785, changing its name to The Times in 1788.

The paper views its start date as 1785. Correspondence from Times Archivist Nick Mays to authors (April 2014).

9 Platt v Walter (1867) 17 LT (NS) 157, 158.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

209From the Author to the Proprietor

the entire business required financial re-evaluation, leading him to seek to repurchase the Platt interests with a view to The Times and the Evening Mail being ‘identical in ownership and character’. Because of this situation, Walter sought dissolution of the partnership and, following unproductive discussions, Sir Joshua’s sons were thereafter denied access to the type from The Times. Platt’s suit sought dissolution of the partner-ship and an injunction against Walter, impeding his entry onto the premises as well as from editing and publishing the Evening Mail, including republished material from The Times. Platt’s legal claim was partly constructed on the basis of his ‘share in the copy-right’ of the Evening Mail. In considering this issue, the court had to determine whether the Evening Mail was merely the ‘handmaiden’ of The Times. If this was deemed to be the case, there was potentially no copyright infringement. The matter was discussed in terms of the content of the paper and the nature of the property rights associated with it. Due to the process of editorial selection and abridgment, the two titles were not consid-ered identical. It was further determined that the Evening Mail had always been treated as separate property, as evidenced by the various separate share transactions.10 Platt’s claim that an irrevocable right had been created allowing him to republish material from The Times was rejected. The Lord Chancellor noted that when a title was sold, it merely entailed a right to continue to use the name, the goodwill and the value of any share of profits that could be generated, presuming the title remained an ongoing concern.

Dismissal of Platt’s copyright claim was based on an interpretation of the legal right to copyright in newspapers which, it was alleged, came into existence in accordance with both common law11 and under section 18 of the Copyright Act 1842. The Lord Chan-cellor determined that newspaper copyright only applied to works already in existence. Rights originated from the material production of the works and could not arise from mere anticipation that this would occur in the future. Thus he doubted the possibility of prospective copyright ownership in relation to newspapers or, by implication, periodical and serial copyright, separate from the copyright in the discrete works, altogether. That there had been a past custom of sharing the copy and lead type with use of the premises at best created a contractual licence; there was no legal right to future copyright as a form of property.

Catherine Seville argues that the periodical right worked ‘tolerably well’.12 however, the 1878 Report of the Royal Commission on Copyright stated: ‘It has been decided … that a newspaper is not a “book” within the meaning of the Copyright Act of 1842 … there is some sort of copyright in newspapers, yet the courts have always leant to the opinion that there is no copyright independent of statute.’ Furthermore, ‘much doubt appears to exist in consequence of several conflicting legal decisions whether there is any

10 Publishers had traditionally divided ‘shares’ in lucrative titles. See John Feather, A History of British Publishing (Routledge, 1991) 53–55.

11 There is no substantive discussion of common law copyright in the case.12 Catherine Seville, Literary Copyright Reform in Early Victorian Britain (Cambridge University Press, 1999)

249.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

210 Journal of Media Law

copyright in newspapers’.13 In writing about Platt v Walter in 1881, Copinger also noted that judicial doubt remained at the time as to whether copyright existed in newspapers at all.14 In the 1893 edition, he elaborated further, stating that there could be ‘no copyright in a non-existent thing. Copyright only accrued when the matter was actually produced. Accordingly, the plaintiffs could not be entitled to a share in, nor could prescription act upon, a right which was not yet in existence.’15 Thus the newspaper proprietor’s right was entirely derived from the authorial right, assigned from the journalist who first penned a particular writing. Nonetheless Copinger questioned whether Platt v Walter could be correct given that the literal words of section 18 clearly anticipated the rights of newspaper proprietors as employers and as the copyright owners of works commis-sioned and paid for.16 Though scant attention was paid to defining it in the Copyright Act 1842, and copyright appears there as both an author’s and a proprietor’s right, when it comes to the courts, ‘authorship’ is treated as the foundation of copyright. Newspaper customs, contracts and trade practices may have created expectations of income streams tied up with production of future editions, but the content of these compilations, in terms of the make-up of the individual literary works and advertising copy, was uncer-tain. It was not possible to determine in advance the precise nature of the ‘contributions’, when they would be produced, by whom, and whether they would be worth republishing in subsequent titles. The indeterminate and open-ended arrangements regarding selec-tion of the newspaper copy meant that these arrangements were not about ‘copyright’ at all. Accordingly, following Platt v Walter, standard terms of publishing agreement between employees, contracting authors, proprietors and other titles became potentially unenforceable.

The notion of newspaper copyright as, presumptively, an author’s and not a pro-prietor’s right was further refined in later newspaper cases. In Walter v Howe (1881)17 the court failed to recognise the Times’ copyright interest in a memoir by Benjamin Disraeli. The court found that a contractual arrangement with the author could have potentially vested rights in the proprietor, but without the newspaper first registering their rights as provided under section 19 of the Copyright Act 1842 after publication the proprietor could not sue in order to restrain an infringement by a rival press. In

13 Copyright Commission, Report of the Royal Commission on Copyright (C 2036, 1878), vii; xvii cited in Peter Putnis, ‘New Media Regulation: The Case of Copyright in Telegraphic News in Australia, 1869–1912’ (Communications Research Forum, Canberra, October 2003).

14 Walter Arthur Copinger, The Law of Copyright: In Works of Literature and Art (Stevens & haynes, 2nd edn 1881) 459. For discussion of further difficulties see Kathy Bowrey and Catherine Bond, ‘Copyright and the Fourth Estate: Does Copyright Support a Sustainable and Reliable Public Domain for News?’ (2009) 4 Intellectual Property Quarterly 399, 409–14.

15 Walter Arthur Copinger, The Law of Copyright: In Works of Literature and Art (Stevens & haynes, 3rd edn 1893) 548–9; Walter Arthur Copinger and John Marshall Easton, The Law of Copyright: In Works of Literature and Art (Stevens & haynes, 4th edn 1904) 244.

16 See also TE Scrutton, The Law of Copyright (William Clowes and Sons, 2nd edn 1890) 104.17 Walter v Howe (1881) 17 Ch D 708.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

211From the Author to the Proprietor

Walter v Steinkopff (1892)18 the firm was successful in an infringement action aimed at restraining republication of material from The Times in an evening newspaper, St James’s Gazette.19 however, this time they had duly registered the periodical publication, the particular edition at issue and the copyright assignment from Rudyard Kipling of the commissioned article on America, ‘On the Monadock’. Nonetheless, it was still not pos-sible for Walter to instigate infringement proceedings for other republished material in St James’s Gazette, because, without evidence of registration or assignment of authorship of the articles at issue, the proprietor was unable to prove ownership of that material.20

While the legislature had clearly envisaged a case for newspaper copyright, there had been little attention paid to the relationship between the author and the proprietor and their respective property interests. Authors had an interest in owning their discrete, tan-gible expressions. The proprietor, as the distributor, had an interest in a different kind of property altogether. It was more abstract and managerial in foundation.21 Management involved the coordination of the discrete productions of authors compiled within the one title, as well as the insight related to republication opportunities at a later time and in alternative venues. The proprietor had much to lose from infringement. Damage did not derive from the republication of any particular infringing work, but from the lost opportunity to exclusively control potential profitable channels of distribution. Despite this economic reality, the formal arrangement of copyright in newspapers, as expressed in the statute and as re-imagined in the ensuing litigation, placed the author as present and in control, from the point of origination of rights through to the registration that enabled the infringement action to proceed. The ‘landmark’ case of Walter v Lane (1900) at the end of the nineteenth century only further entrenched this authorship model.22 This case remains a highly significant copyright decision that is often cited in order to demonstrate the court’s flexible approach to interpreting authorship, originality and the requirement of fixation.23

18 Walter v Steinkopff [1892] 3 Ch 489.19 St James’s Gazette was edited by Sidney Low from 1888–97. ‘Obituary: Sir Sidney Low, Journalist and

Author’ The Times (London, 14 January 1932), 14. The paper amalgamated with the Evening Standard in 1905.

20 Cf Brown v Cooke (1848) 11 Jur 77, where the court noted that confusion over the proprietor’s ownership of articles should not be permitted to excuse piracy. In Walter v Steinkopff (1892) the court explicitly rejected the notion that there was no copyright in news. It also rejected the defence of a trade custom based on ‘a universal mutual understanding amongst journalists—a tacit convention to which The Times was a party—that one paper may copy from another without asking permission’ subject to a number of conditions. Walter v Steinkopff [1892] 3 Ch 489, 496–7.

21 In essence it is closer to the interests later protected in the category of ‘subject matter other than works’ than to a traditional author’s right.

22 See Thomas E Scrutton, The Law of Copyright (William Clowes and Sons, 1903) 119–20. Note that Scrutton had acted for the defendant, Lane. See also Alexander Moffatt, ‘What is an Author?’ (1900) 12 Juridical Review 217.

23 See www.cipil.law.cam.ac.uk/virtual_museum/walter_v_lane_%5B1900%5D_a.c._539.php (accessed 9 May 2014). See also analysis of the case in hector L MacQueen, ‘“My Tongue is my Ain”: Copyright, the Spoken

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

212 Journal of Media Law

(b) The significance of Walter v Lane (1900)

Walter v Lane was instigated by the then principal proprietors of The Times, Arthur Fraser Walter (1894–1908) and his brother Godfrey (1866–1922).24 It concerned Lane’s publi-cation of a book entitled Appreciations and Addresses delivered by Lord Rosebery, which reproduced five speeches published earlier in The Times.25 The newspaper, somewhat ironically, ended up reporting on the status of its own copyright, under the headline, ‘Is there copyright in newspaper reports?’. The report outlines the newspaper’s case in these terms:

The principle is that when a newspaper has expended labour, forethought, and money in pro-ducing something which the public want to read, it ought to have the same rights of property in its production that are enjoyed by those who use brains and capital in producing other articles having commercial value … yet, owing partly to imperfect definition of the right by legal decisions and partly to the existence of what may be called a parasitical Press mainly dependent upon conveyance from a few original sources for the matter that fills its columns, this eminently sound and equitable principle has come to be ignored, and even or more or less sophistically denied.26

Embarking on the case against Lane was controversial. It was not the typical dispute between London and provincial newspapers for ‘lifting’ news, as in Walter v Steinko-pff.27 Nor did it involve two direct competitors facing one another.28 The complaint lodged by Walter tested the boundaries and limits of genres between newspapers and book publishers. Accordingly, the two litigants sought to mobilise alliances vis-à-vis the case. Lane’s solicitor, Mowbray A Upton, emphasised that it was important to ‘enlist financial support’ and to ‘persuade your supporters’.29 Following his advice, Lane spent the period between the first instance and the appeal decision (in which he succeeded) gathering support. A significant number of journalists,30 poets and writ-

Word and Privacy’ (2005) 68(3) Modern Law Review 349; Nigel P Gravells, ‘Authorship and Originality: The Persistent Influence of Walter v Lane’ (2007) 3 Intellectual Property Quarterly 267; Estelle Derclaye, ‘Debunking Some of UK Copyright Law’s Longstanding Myths and Misunderstandings’ (2013) 1 Intellectual Property Quarterly 7; Nigel P Gravells, ‘Reporter’s Copyright and Sound Recordings: A Reply to Professor Derclaye’ (2013) 2 Intellectual Property Quarterly 91.

24 Arthur Fraser Walter was principal proprietor of The Times from 1894 to 1910. See A Newspaper History, 1785–1935 (The Times, 1935), 17; see also ‘Arthur Fraser Walter (Obituary)’ New York Times (New york, 23 February 1910).

25 For further details see Megan Richardson and Julian Thomas, Fashioning Intellectual Property: Exhibition, Advertising and the Press, 1789–1918 (Cambridge University Press, 2012) 116–22.

26 ‘Is there Copyright in Newspaper Reports?’ The Times (London, 11 August 1899), 7.27 See further EhC Moberly Bell, The Life and Letters of CF Moberly Bell (Richards Press, 1927) 185–6;

F Wicks, ‘Newspaper Copyright’ The Times (London, 7 June 1892), 6.28 Richardson and Thomas have also noted this strategic point. See n 25, 119–20.29 Mowbray A Upton [letter to John Lane], 12 August 1899, John Lane Company Records, harry Ransom

Center, University of Texas at Austin, Box 50.1.30 ‘I was so glad to see that your appeal against The Times was sustained—more power to you!’ John Joy

Bell (Scottish journalist) [letter to John Lane], 17 November 1899, John Lane Company Records, harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, Box 4.4.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

213From the Author to the Proprietor

ers31 and members of the National Liberal Party32 joined his cause. The National Liberal Party’s investment in the publication of Lord Rosebery’s speeches saw the head of Pub-lications Charles Geake (1876–1919) editing the volume for Lane. however, Lane soon learned to his detriment that the cultivation of allies was difficult. The Publishers Associ-ation had been founded a few years earlier to aid book publishers in the establishment of common policies and practices of their trade.33 Unfortunately for Lane, the president of the association, John Murray (1851–1921), not only did not back his defence, but came out in support of the newspaper publicly, in a letter published in The Times34 a week after the first instance decision.35 That Lane was disappointed is an understatement. he thought that Murray ‘nourished a grievance’ against him.36 Almost a decade later, he still believed that he had lost the case because of that letter, since—in his view—the newspaper only took the case to the house of Lords after the support given by Murray.37

The facts of the case were not contested. Lane conceded that the copies of the speeches were based on cuttings from The Times, but claimed that they were also proofed and corrected by Lord Rosebery—although four remained identical to the press versions and the publication itself notes Charles Geake as editor. Lord Rosebery made no claim to copyright whatsoever. Walter v Lane revolved around the issue of origination of rights and subsistence of copyright in copy of his speeches, as recorded by various unnamed journalists associated with The Times. Subsistence and registration were treated as sepa-rate matters,38 and no issue was raised as to registration. A week before issuing the writ, The Times arranged for a series of copyright assignments from its reporters to be made in order to commence the action.39 These transactions were not only crucial to the initiation

31 Richard le Galienne, ‘The Times v Lane’ [poem to John Lane], undated, John Lane Company, harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, Box 27.3; Mabel Kitcat [letter to John Lane], 11 August 1900, John Lane Company Records, harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, Box 24.4.

32 ‘I can’t but believe that North would be reversed. There is so little equity in proving the reporter’s copyright as against the author as speaker.’ Charles Geake [letter to John Lane], 11 August 1899, John Lane Company Records, harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, Box 17.1.

33 RJL Kingsford, The Publishers Association 1896–1946 (Cambridge University Press, 1970).34 John Murray, ‘Copyright in Reports and News’ The Times (London, 17 August 1899), 6; John Murray

and John Lane, ‘Copyright in Reports and News’ The Times (London, 26 August 1899), 10; John Murray, ‘Copyright In Reports and News’ The Times (London, 31 August 1899), 10.

35 ‘The President, in his private capacity, had sent a letter to The Times, upholding Mr Justice North’s decision in this case, and to this proceeding Mr Lane had objected. The Council were of the opinion that the President’s conduct was perfectly proper and therefore fully endorsed it.’ in Minutes of Council Meeting, 19 October 1899, Publishers Association Archives, 257.

36 John Lane [letter to John Murray], 20 May 1908, John Lane Company Records, harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, Box 23.3.

37 John Murray [letter to John Lane], 21 May 1908, John Lane Company Records, harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, Box 23.3.

38 See Walter v Howe (1881) LR Ch D 708; Trade Auxillary Company v Middlesborough and District Tradesmen’s Protection Association (1888) LR 40 Ch D 425; Cate v Devon and Exeter Constitutional Newspaper Company [1899] 60 Ch D 500.

39 Ernest Brain (copyright assignment 26 June 1899); Cornwallis henry Smith (copyright assignment 28 June 1899). Arguably, the strategy was devised after the failure of a previous action instituted by The Times [Walter v Howe (1881) 17 Ch D 708]; see Augustine Birrell, Seven Lectures on the Law and History of Copyright in Books (Cassell, 1899) 159–60.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

214 Journal of Media Law

of proceedings,40 but prevented any direct discussion over Walter’s claim to ownership of the journalistic efforts.41 This strategy was commented on at the time.42 The Times case required the proprietor to distinguish their ‘parasitical’ behaviour in reproducing Lord Rosebery’s speech from that of Lane’s. The company had the ‘forethought’ and had covered the expense in sending the reporters, who then exercised their professional skill in transcribing the speech. The newspaper proprietor claimed copyright in the speeches under both section 2 and section 18 of the Copyright Act 1842. Walter sought a decla-ration that they were owners of the copy of the speeches and an injunction to restrain publication of Lane’s book.

The first instance judge, North J, sought to resolve the matter on terms narrower than those described in the Times article, making little reference to the managerial inputs of the proprietors and only referencing the reporters’ efforts as ‘labouring author[s]’. North J distinguished between authorship of the speech and the report of the speech. With respect to the latter, a comparison was made with the following: compilation, which could involve a copyright entailing independent work;43 translation, in which ‘each per-son uses his own head and brain’; and directories, where ‘it is quite clear that one man may publish a directory, and another man may publish another, but he must not take it from the first’.44 North J found that there was copyright in every reporter’s version of the speech and as such Walter was entitled to an injunction. The Court of Appeal rejected this approach, which they noted would leave Lord Rosebery without any copyright and 12 reporters with exclusive rights to his speech. The legislation had not explicitly defined ‘author’. however, ‘[t]he word occurs constantly throughout the Act, but nowhere is it used in the sense of a mere reporter or publisher of another man’s verbal utterances’.45 The Court of Appeal required some distinctive literary input in order to denote author-ship, forging a clear line between authorial and scribal labour. In so doing, they further narrowed the inquiry to one merely about the relationship between author and text, in

40 For another copyright case in which an urgent preliminary assignment dramatically failed, see Jose Bellido, ‘The Failure of a Copyright Action: Confidences in the Papers of Nora Beloff ’ (2013) 18(3) Media & Arts Law Review 249.

41 J Andrew Strahan, ‘The Reporter and the Law of Copyright’ (1900) 26 Law Magazine and Review 35; see also ‘Conference of Journalists’ Law Times (London, 15 September 1900), 446; ‘Institute of Journalists’ The Times (London, 12 September 1900), 6.

42 ‘The Times Managers have anticipated this difficulty … Presumably they did this under good legal advice.’ JE Taylor [letter to C Prestwich Scott], 18 August 1900, Guardian Archive, University of Manchester Library, Series 130 and 131.

43 Citing Leslie v Young & Sons [1894] AC 335; Walter v Lane [1899] 2 Ch 749, 753. 44 Walter v Lane [1899] 2 Ch 749, 757–9.45 Further, ‘[t]he printer or reporter of a speech is not the “author” of the reported speech in any intelligible

sense of the work “author”. To hold that every reporter of a speech has copyright in his report would be to stretch the Copyright Act to an extent which its language will not bear, and which the Legislature obviously never contemplated. The Act was passed to protect authors, not reporters. Moreover, although it may be that reporters and their employers ought to be protected from the unauthorised appropriation of their labour by others, it by no means follows that Parliament would place reporters and their employers on the same footing as authors.’ Walter v Lane [1899] 2 Ch 749, 770–1.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

215From the Author to the Proprietor

particular directed to identification of some original input. however, there was no for-mal requirement of originality expressed in the 1842 Act.

A successful appeal to the house of Lords restored the decision of North J, further refining the legal definition of authorship. Any claim of authors under common law, such as a right to unpublished works, was distinguished from the rights conferred by the statute:

[T]he judgment of the Court of Appeal rests solely on the use of the word ‘author’, and I can-not help thinking that some confusion has been created between two very different things: one, the proprietary right of every man in his own literary composition; and the other the copyright, that is to say, the exclusive privilege of making copies created by the statute.46

As Lord Davey noted, ‘[c]opyright is the right of multiplying copies of a published writing’.47 he later added, ‘[c]opyright has nothing to do with the originality or liter-ary merits of the author or composer’.48 The house of Lords decision was a significant victory for The Times.49 Following Walter v Lane republication rights were now clearly based on copyright and contract, and not just contract alone. The case created quite a generous concept of ‘authorship’ detached from close consideration of the literary content of the work, and this ostensibly allowed the proprietor to control all sorts of ‘parasitical’ copying of copy. The decision thus set newspaper syndication on much firmer legal foundations than had previously been the case. In this sense, the legal action was, above all, a ‘test’ case.50

It is noteworthy that in the Times editorial about Walter v Lane it was suggested that permission would normally have been granted to republish this kind of work. Lane’s transgression was purely that of taking without asking for permission.51 What the Wal-ters wanted was legal endorsement of the ‘need to ask’, and underlying this, the right to control exclusive distribution channels. however, the path that emerged legitimated syn-dication rights by tying the proprietor’s right even more closely to that of the origination of copyright with the author. This required the proprietor to regularise the employment terms of reporters and to clearly tie up claims to future copyright, whether the work originated from employees or freelancers, or from inside or outside the UK. however, throughout the nineteenth century, management of the labour relations of the firm had proved troublesome. In the twentieth century, with further expansion of media empires

46 Walter v Lane [1900] AC 539, 547 (halsbury LC)47 Ibid, 550.48 Ibid, 552.49 The paper reproduced the entire judgment, which took up the majority of page 2 (‘Walter v Lane’ The

Times, (London, 7 August 1900)), as well as running an editorial in the same edition.50 J Lewis May, John Lane and the Nineties (Butler & Tanner, 1936) 230.51 ‘The Times have never attempted to strain its rights against any one who approached it in a reasonable

manner … but Mr Lane asked no permission, and cannot show that Lord Rosebery desired or approved of a republication which, however, he was powerless to prevent.’ ‘Editorial’ The Times (London, 7 August 1900), 7.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

216 Journal of Media Law

and increasing international opportunities, it would prove even more difficult to man-age.

2. MANAGERIAL AMBITIONS IN ThE TWENTIETh CENTURy

The law firm that had provided the majority of the legal advice to The Times in all the above cases was Soames, Edwards & Jones.52 Originally the arrangement was with the Soames brothers, Joseph and Francis, and later with Joseph’s son, Joseph Charles Soames (1871–1930).53 Soames also instructed Counsel in the matter of the state of the Copy-right Acts at the end of the nineteenth century.54 In July 1949, Francis Mathew (1907–65) was appointed manager of The Times.55 The youngest son of ‘one of the best-known members of the English Bar’,56 Mathew was known to the newspaper proprietors,57 and he also had ‘all the abilities required for the management without any temptation to meddle with the editorial part’.58 his real strength was ‘in production, labour relations, costs and finances for he understood business and would have had a plan ready if the paper ran into choppy weather’.59 In fact, Mathew’s managerial talents would soon be tested when copyright at the newspaper came under scrutiny. In 1949, a change in man-agement at Printing house Square, home of the newspaper since its inception in the late eighteenth century, also entailed a reconsideration of newspaper work and the legal framework surrounding it.

52 Joseph Soames (1841–1909) made his name as solicitor of The Times and ‘was for many years the honorary solicitor of the Newspaper Society’. See ‘Mr. Joseph Soames (Obituaries)’ The Times (London, 18 September 1909), 11. The firm also represented the newspaper in famous libel suits such as Hales v The Times Publishing Co (1929) and O’Donnell v Walter (1888). See also John haslip, Parnell: A Biography (Cobden-Sanderson, 1936) 346, 348–9, 364, 369; Richard B O’Brien, The Life of Lord Russell of Killowen (Smith, Elder & Co, 1901) 214–15.

53 ‘Mr. Joseph Soames (Obituaries)’ The Times (London, 14 March 1930), 16; see also Various Authors, The History of The Times, 1884–1912, vol III (The Times, 1947), 45–89; Dodgson Bowman William, The Story of The Times (Routledge, 1931) 288–92.

54 ‘Case to advise in consultation Mr Fletcher Moulton—The Copyright Acts; 30 October 1890, Soames, Edwards & Jones’, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (1890–1936), Times Newspapers Limited Archives, News UK and Ireland Limited (TNL Archives).

55 ‘Obituary—Francis Mathew’ The Times (London, 30 March 1965), 15; see also Stanley Morison (ed), The History of The Times, vol IV, part II: 1921–1948 (The Times, 1952) 991.

56 ‘Obituary—Theobald Mathew’ The Tablet (London, 25 June 1939), 825; Theobald Mathew was a bencher of Lincoln’s Inn and writer of the famous Forensic Fables (Butterworth, 1926) and For Lawyers and Others (William hodge, 1937); see also The Practice of the Commercial Court (Butterworth, 1902) and his edited Reports of Commercial Cases (Butterworth, 1896).

57 See Iverach McDonald (ed), The History of ‘The Times’, vol V: Struggles in War and Peace, 1939–1966 (Times Books, 1984) 167.

58 Stanley Morison quoted by McDonald (n 57) 166–7; see also O Woods and J Bishop, The Story of the Times (Michael Joseph, 1985) 328–9.

59 See McDonald (n 57) 166–7.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

217From the Author to the Proprietor

Soon after Mathew was appointed, the newspaper changed its solicitors, moving away from Soames, Edwards & Jones and strengthening ties, both professional and personal, with Charles Russell solicitors, a law firm founded by Sir Charles Russell (1863–1928).60 Consulting these solicitors appears to have been the obvious choice for Mathew because of his personal links with the firm.61 Additionally, the influential newspaper consultant who had recommended Mathew to The Times, Stanley Morison, was a close associate of another partner of Charles Russell solicitors, Richard (‘Dick’) Butler (?–1965).62 The first legal issue that Mathew consulted with the firm concerned the copyright status of letters sent to the paper and published in the correspondence columns. The newspaper was advised to insert at the head of the correspondence column each day a notice to the effect that the writer of the letter shall be deemed to have conferred upon The Times a licence to republish the letter on any future occasion.63 The second query related to some of the first editorial decisions taken under Mathew’s management. In 1951, the newspa-per had decided to continue the practice of publishing separate supplements, reviews and magazines.64 An example of this was the birth of The Times Review of Science (TRS), established in 1951 as a quarterly paid-for science review. As the repertoire of maga-zines grew, it became apparent to Mathew that there was a need to administer resources more efficiently. Therefore he asked the legal team whether it was possible to republish articles from reviews in magazines and vice versa, without having to treat each publica-tion as if it involved a separate transaction,65 and to streamline copyright procedures to maximise a flexible news service across publication venues. In the summer of 1952, Mathew consulted Butler about whether arrangements for the ‘assignment of copyright in contributions to The Times should not be tightened up’.66 Mathew’s day-to-day job at

60 ‘Sir Charles Russell (Obituaries)’ The Times (London, 28 March 1928), 11.61 his brother, Sir Theobald Mathew (1898–1964), had been a partner at the law firm before the Second

World War. After the war, he became Director of Public Prosecutions; see Jonathan Rozenberg, The Case for the Crown: The Inside Story of the Director of Public Prosecutions (Equation Books, 1987) 26–31; see also Mathew’s description of the role in his lecture delivered at the University of London entitled The Office and Duties of the Director of Public Prosecutions (Athlone Press, 1950).

62 Stanley Morison (1889–1967) was typographical advisor but became the newspaper’s historian and a general adviser. See James Moran, Stanley Morison: His Typographical Achievement (Lund humphries, 1971) 132; see also Derwent May, Critical Times: The History of The Times Literary Supplement (harperCollins, 2001) 274–94; James Moran, ‘Stanley Morison (1889–1967)’ (1968) 43(3) Monotype Recorder 21–22. The different meetings are recorded in the diaries of Stanley Morison (MS Add.9812/E1/24 and MS Add.9812/E1/23) in Cambridge University Archives. See also ‘Richard Butler—Obituary’ The Tablet (London, 30 January 1965), 20.

63 Charles Russell solicitors [letter to the Secretary of The Times], 24 August 1951, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

64 One of the reasons for this trend could have been that the new manager, Francis Mathew, was a great supporter of supplements; interview with Charles Mathew (Leicester, April 2013).

65 PE Clarke [letter to Francis Mathew], 20 June 1952, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

66 Richard Butler [letter to Francis Mathew], 22 July 1952, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

218 Journal of Media Law

the paper made him realise that keeping track of who held the copyright for each piece of the newspaper’s content was an infrastructural problem and hard to handle. Morison, too, recognised that reorganising the copyright protocols in the paper was extremely important since ‘we have had struggles in the past over contributions written by people not on the staff ’.67 The value of the enterprise was now clearly related to the underlying copyright framework that could render all material readily available for publication in any way deemed fit, without limits or restrictions. In order to find the ‘right formula’ for The Times, Butler began corresponding with Alan Daubeny Russell-Clarke (1904–80), a leading barrister on copyright matters.68

The newspaper searched for a distinctive copyright system tailored to the needs of an expanding publishing enterprise. The company explicitly sought a system geared toward the syndicated market and to the (potential) future uses of material received at Printing house Square, to replace the old-fashioned authorship model that revolved around first publication of the work in a specific title and place of publication.69 Mathew was keen to emphasise that it was crucial to standardise the conditions under which ‘we commission the writing of articles’.70 It was equally important to find a suitable copyright framework that reserved rights not only to alter, cut and edit, but also to sell the articles to other newspapers, periodicals and even broadcasters.71 The matter proved difficult to resolve. In 1954 the problem flared up again, this time over the BBC’s re-use of material first published by The Times,72 causing it embarrassment through the failure to manage and control the terms of distribution of ‘their’ copy.73 Many different practices, actors and situations were identified as contributing to the unsatisfactory position.74 Some prob-lems were related to discipline within the organisation. For instance, when an article was commissioned by a particular department—home, foreign, industry, arts—the question of copyright may not have been routinely mentioned at all. In other cases, material sent to the newspaper by contributors was received via different media (letter, cable or tele-phone), in different forms and by people with varying relationships with the newspaper.

67 ‘I am all in favour of tightening up the practice if one could reach the right formula’: Stanley Morison [letter to Francis Mathew], 28 July 1952, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

68 In 1951 AD Russell-Clarke had published his Copyright and Industrial Designs (Sweet & Maxwell, 1951).69 Similarly, the Manchester Guardian considered the need to order its copyright practices ‘as one of the

consequences of our American syndication’; Internal Memorandum, 26 March 1956, Guardian Archive, Syndicated Features, Manchester Library, Series 148/13/1-42.

70 Francis Mathew [letter to Richard Butler], 14 August 1952, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

71 Ibid. 72 ‘A Friend of Britain in the Troubled East Siam’s Anti-Communist Role—Prince Chula’ The Times (London,

28 April 1954), 9.73 Norman [letter to Iverach McDonald], 28 April 1954, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General

Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives; see also Parker [note to Stanley Morison], 11 May 1954, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

74 Internal note, 24 March 1954, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

219From the Author to the Proprietor

The type of contribution and mode of reception affected the ensuing management of copyright. Given the range of factors involved, it made it difficult to repeat the same for-mula and standardise copyright practice across the enterprise. As a result of this chaos, it also became apparent that the newspaper had been assigning copyright to other news-papers for articles ‘of which we do not ourselves hold the copyright’.75 Amidst these trying circumstances, the solicitor Butler reported back to the organisation that all the contracts were meaningless unless the newspaper got the writers of the articles to assign the entire copyright.76 By the mid-twentieth century, the traditional authorship model envisaged by Walter v Lane was at breaking point. The size, scale and complexity of the organisation, and the desire to reach into disparate media markets, made it impossible to manage authorial relations and existing and potential commercial opportunities with any legal certainty.

3. A NEW SySTEM FOR CAPTURING RIGhTS

(a) Classification Exercises

In response to Butler’s concerns, Mathew decided that the time had come to instruct Counsel. The advice of Russell-Clarke was sought to recommend the best method for implementing a system to secure ‘as far as may be possible the copyright in all articles or dispatches printed’. It clearly had to encompass not only the newspaper but also its regu-lar subsidiary periodicals such as the TRS and the Times Literary Supplement (TLS).77 The newspaper gave the barrister a comprehensive report detailing all the different types of writers connected to the company. Given the historical and legal emphasis on author-ship, separating contributors with reference to ‘the various and miscellaneous categories of the individuals who supplied material’78 seems logical and inevitable. The lengthy memorandum sent to Russell-Clarke incorporated a spreadsheet, which did not limit the taxonomy of the newspaper’s contributors to the correspondents employed by the newspaper, but extended it to include different groups of correspondents. The classifica-tion system was intended to organise the details of each piece of material received, from stories to dispatches, sorting each piece by author, with reference to the format in which these were received at Printing house Square, by how they were originally published, and linking them to their type of exchange and transmission in newspaper work. The

75 Parker [letter to Francis Mathew], 15 June 1954, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

76 Ibid. 77 Instructions for Counsel, undated, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence,

1946–54), TNL Archives.78 Memorandum – Copyright – Correspondents of The Times, undated, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks

(Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

220 Journal of Media Law

memorandum also included a report on the syndicated market, a strategy to ensure that Counsel was aware of the newspaper’s broader ambitions.

The first distinction made in the spreadsheet concerned the contributor’s place of residence. This starting point may seem counter-intuitive to lawyers who tend to assume that an individual’s initial status as employee or independent contractor is the starting point for identifying copyright ownership.79 however, the list avoided the use of the terms ‘employee’ and ‘freelance’ altogether, and the appendix clarified what the paper considered, generally speaking, to be ‘our’ contributors—a category that included both staff and non-staff correspondents. Correspondents were classified geographically and primarily determined by whether the individual corresponded from within or outside the United Kingdom. For instance, Counsel was told that no copyright arrangements had been explicitly made with North American contributors and that Stanley Morison would pass the names to the newspaper’s chief accountant who instructed their New york office to pay them.80 This initial mode of classification demonstrates the newspaper’s prioriti-sation of relations of exchange as a way to organise contributions. It used the place from where the material was transmitted as a means to distinguish between different types of contributions. The spreadsheet also referred to the use of payment schemes as a way to locate and fix the identity of the copyright subject. Instead of relying on when material was created, or the specifics of the contract agreed upon, modes of payment were thought to be the most efficient coordinates to grasp the concrete reality of copyright ownership. The classification was divided into further categories, using modalities of payment such as ‘retainer’ and ‘space rates’. Using this system of accounting, the list identified at least 10 different types of contributions to the newspaper.81

The newspaper’s long tradition of fostering anonymity,82 a singular and fundamental feature of Times reporting, also created a unique problem for classification. Anonymity

79 This view is summarised in Lionel Bently and Brad Sherman, Intellectual Property Law (Oxford University Press, 2009) 127–31.

80 American Literature – Copyright, undated, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1954–9), TNL Archives.

81 The different contributions classified were the following: ‘(a) Correspondents in the UK: (1) Staff Corre-spondents; (2) Non-Staff Correspondents paid a retainer; (3) Non-Staff Correspondents paid space rates only; (4) Non-staff correspondents contributing one or a series of special articles, called ‘our special cor-respondent’ or ‘a correspondent’ writing anonymously; (5) Non-staff correspondents contributing one or a series of special articles, writing under their name; (b) Correspondents outside the UK: (6) Staff cor-respondents; (7) Non-Staff correspondents paid a retainer; (8) Non-staff correspondents paid spaces rates only; (9) Non-staff correspondents contributing one or a series of special articles called “our special cor-respondent” or “a correspondent” writing anonymously; and (10) Non-staff correspondents contributing one or a series of special articles, writing under their own name’: Parker [memo to Francis Mathews], 15 June 1954, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1954–9), TNL Archives.

82 ‘Times journalism was anonymous in those days, as it was to remain for many years’: Frank Giles, Sundry Times (Murray, 1986) 73; see also William hargreaves, Is the Anonymous System a Security for the Purity and Independence of the Press? A Question for The Times Newspaper (William Ridgway, 1864) 27 (‘There never has been, and, probably, never can be, a fairer experiment of the anonymous system than that which The Times has afforded’).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

221From the Author to the Proprietor

not only differentiated The Times from other newspapers such as The Observer; it also aimed to create ‘corporate loyalty, pride and job satisfaction’.83 Impersonality and ano-nymity were seen as the source of the paper’s power,84 ingredients that had enabled it to build a reputation as ‘an instrument of social and political criticism’.85 For example, the TLS published anonymously, while many sections of the paper, as well as accompanying photographs, did not record individual authorship until the late 1960s.86 This emphasis on anonymity affected the semantics of the classification scheme; the clearest example was the newspaper’s use of the term ‘contributor’ instead of ‘author’ or ‘journalist’.87 In 1955, at precisely the same time that these copyright protocols were being considered, Stanley Morison wrote an interesting memorandum in which he justified the widespread use of anonymity. he insisted on newspaper work as a collective undertaking:

Those who work in these circumstances are rarely authors in the proper sense. The provision of leading articles to the instructions of a superior is not creative writing. Even when the subjects of such articles are suggested by their writers, the treatment is conditioned on many sides, and the articles open to alteration, addition or correction by other hands, so what is printed cannot be said to be the work of a single personality. The personality is not that of the individual, but that of the newspaper.88

This description clearly resonates with the Court of Appeal decision in Walter v Lane (1899), in which the court had found that, lacking ‘personality’, there was no authorship in newspaper reporting. It is interesting to note that although the house of Lords over-turned this ruling, finding that personality was not necessary for copyright to subsist, the relative absence of the substantive authorship element amongst many contributors only further complicated things for The Times in tracking their rights. It contributed to the development of accounting matrices to replace the generic anchor of ‘authorship’.

In the next two decades the principle of anonymity was relaxed.89 This was not only encouraged by the reorganisation of copyright protocols at the newspaper but also induced by other important factors, such as the emergence of a new style of journal-

83 See Giles (n 82) 69.84 SM – Memorandum, 1949, Papers of Stanley Morison, Cambridge University Archives, Series MS Add.9812/

B3/15.85 Stanley Morison, Memorandum on anonymity in The Times, Papers of Stanley Morison, Cambridge

University Archives, Series MS Add.9812/B3/18.86 ‘A Spectator’s Notebook’ The Spectator (London, 24 April 1952), 5; John Mullan, Anonymity: A Secret

History of English Literature (Faber & Faber, 2007) 181.87 Allan haley, Typographic Milestones (John Wiley & Sons, 1992) 100.88 Morison (n 85). 89 Anonymity formally ceased in the Times Literary Supplement in June 1974, although for a few months

thereafter the stock of reviews already submitted before the change were published without identifying the author: correspondence from Nick Mays to authors (April 2014). See also John Gross, ‘Naming Names’ Times Literary Supplement (London, 7 June 1974), 610; Kenneth hibbert, ‘Anonymity’ Times Literary Supplement (London, 21 June 1974), 670; Jonathan Culler, ‘Anonymity’ Times Literary Supplement (London, 28 June 1974), 694; FW Bateson, ‘The Question of Anonymity’ Times Literary Supplement (London, 12 July 1974), 748.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

222 Journal of Media Law

ism and the newspaper’s concern about increasing competition.90 however, back in the mid-twentieth century, anonymity was still the norm, and it posed a unique challenge in classifying the paper’s copyright interests.

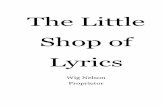

(b) The emergence of contributors’ cheques

A contributor’s cheque or ‘copyright cheque’ was a bespoke instrument devised to assist proprietors with copyright assignment and tracking contributions. These were pre-printed cheques with a copyright clause on the back (see Figure). The key step was to place the copyright clause alongside the requirement of endorsement.91 As the contribu-tor had to sign on the reverse of the cheque to get the cash, the act of endorsing the cheque simultaneously required that the contributor assign the entire copyright to the newspaper.92 By placing the copyright transaction at the end of the whole process—after the material had been sent to the paper—the system of copyright was standardised, foreclosing space for negotiation. If the contributor attempted to alter the form of the cheque, the likely consequence was that the cheque would not be honoured.93 The result was an immediate and very practical problem for the contributor, as the cheque would be returned unpaid.94

This practice had not arisen spontaneously, but was the result of a recommenda-tion made by Joseph Soames (1841–1909).95 Soames’ legal recommendation appears to have been triggered by Walter v Lane.96 News agencies such as Reuters also followed the case closely,97 and the manager of the Guardian also immediately considered whether ‘in view of the recent decision as to the copyright in reports’ we also ‘ought to arrange with the reporters to assign their rights in all their reports [to us]’.98 With reporters now cast as authors, a technology of payment was required to manage reporters’ copyright. These cheques became the main system utilised by The Times to secure copyright in the first half of the twentieth century. It was the method of payment for at least six of the

90 McDonald (n 57) 311–24.91 G herbert Thring, The Marketing of Literary Property (Constable & Co, 1933) 162–3.92 ‘here the author is met with a considerable difficulty, as he cannot get his money until he has endorsed the

cheque, and he cannot endorse the cheque without practically handing over to the proprietor the copyright and other rights that were never bargained for.’ ‘Receipts’ The Author (London, December 1898), 152.

93 ‘In the case of a cheque the matter is different, for the bankers usually have instructions not to cash the cheque if there is any alteration in the endorsement.’ ‘Assignment of Copyright to Magazine Proprietors’ The Author (London, July 1923), 108–9; see also Geo John Lodder, Banking Reminiscences: Some Memories of My Banking Life in Barclays Ltd, 1939–1977 (undated manuscript), Barclays Group Archives (Manchester), C75.

94 Barclays Bank Ltd, Notes for the Guidance of Branch Cashiers (London, 1942) 6, Barclays Group Archives (Manchester).

95 ‘[I]f I recollect rightly, but this form was settled by my father a good many years ago …’ Charles Soames [letter to Cobett], 11 November 1916; for a brief description of Soames, see haslip (n 52) 364.

96 The Times (London, 4 May 1900), 14.97 ‘Walter v Lane’, Reuters Archives, LN 777; 1/972414.98 JE Taylor [letter to C Prestwich Scott], 9 August 1900, Guardian Archive, University of Manchester Library,

Series 130 and 131.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

223From the Author to the Proprietor

ten types of contributors listed in the memorandum.99 Importantly, this system also captured some of the most problematic journalistic contributions, that of non-staff cor-respondents residing in the United Kingdom.

As early as 1916, The Times was accused of setting a ‘bad example’ by this custom, with the Society of Authors explicitly criticising it for inventing the ‘copyright cheque’.100 The legality of the practice was also questioned.101 The newspaper, somewhat ironically, tried to keep the matter out of the press. In so doing, it developed a method of mini-

99 See n 81.100 See ‘Copyright and Receipts’ The Author (London, November 1916) 56–57.101 In the 1950s the Manchester Guardian also considered that the practice developed by The Times was

potentially illegal. An internal memorandum noted: ‘I think that the other method of asking the author to convey the rights by endorsing the cheque is not only working a bit of a fast one, but might even be illegal’: GF [letter to AP Wadsworth], 23 March 1956, Guardian Archive, University of Manchester Library, Series 148/13/1–2.

Figure. Front and back of the Times cheque, with copyright assignment on the back. Image courtesy of the TNL Archive.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

224 Journal of Media Law

mising criticism and risk of litigation. If a contributor disagreed with this practice, the newspaper ceded the outright assignment of copyright. The Times would swap the initial cheque for a new one without the copyright formula because—as the newspaper would reply—‘it is not a point which we wish to press in your case’.102 however, this exchange happened only after the contributor complained; the contributor was burdened with the task of complaining to the editor, and the delay that inevitably resulted from issuing a new cheque. Perhaps not surprisingly, requests for replacement cheques were quite rare.103 It is possible that the newspaper’s emphasis on requesting a replacement cheque as being a personal decision helped to pre-empt collective action and objections against the practice. This could also explain why the newspaper was particularly successful at avoiding litigation.104 The close link between the transaction of payment and the trans-action of copyright made the system extremely effective and silenced objections. Since the newspaper also cultivated the notion that making money was ‘something unfit for gentlemanly conversation’,105 the fact that the exchange of money and copyright assign-ment were undertaken entirely via written communication enabled the newspaper to avoid direct discussions about these issues.106

Despite the fact that the cheques had been a very efficient system to secure out-right copyright assignments for decades, Butler’s ongoing investigation uncovered some problems and loopholes in practice. One particularly troubling issue was that not all members of the editorial staff had signed an employment contract. This might have been due to the newspaper’s explicit policy of avoiding formal contracts.107 A formal system of appointments might have been seen as undesirable because of the contractual and liability risks it could generate. On account of this, Butler wrote to Francis Mathew in 1952: ‘I am presuming that for many reasons you would not wish such a formalised sys-tem to be instituted.’108 however, not formalising employee labour relations had serious implications following Walter v Lane. Furthermore, the system of securing copyright via contributors’ cheques was itself not foolproof in catching all non-employee contribu-

102 ‘Copyright and Receipts’ (n 100) 56.103 As Jean-Joseph Goux notes, ‘[w]hat is most striking about the check, by comparison with the bank note, is

the movement from a purely public and political realm of personalization (the signature of the treasurers of the State) to a private realm of personalization, which engages identities in a wholly different way.’ Jean-Joseph Goux ‘Cash, Check, or Charge?’ in M Woodmansee and M Osteen (eds), The New Economic Criticism: Studies at the Intersection of Literature and Economics (Routledge, 1999) 114, 117.

104 This was a strategy long mooted by the journal The Author, which poignantly asked: ‘Is it possible that the proprietor relies on the reluctance of the author to go to law?’ As noted in ‘Receipts’ (n 92).

105 McDonald (n 57) 67.106 As it was reported in The Author, the ‘question of payment is a delicate one’, particularly for freelancers; see

‘Some Freelance Experiences’ The Author (London, May 1903), 207. See also ‘The Journalistic Free Lance’ The Author (London, February 1902), 117–18; ‘The Journalistic Free Lance’ The Author (London, March 1902), 146–7.

107 According to a former correspondent, the newspaper ‘was traditionally loath to commit itself ’. Giles (n 82) 47.

108 Richard Butler [letter to Francis Mathew], 22 July 1952, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1946–54), TNL Archives.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

225From the Author to the Proprietor

tors. A series of problems hampered their worldwide circulation. Distant correspondents and stringers were affected by currency restrictions, a barrier that made it difficult for payment by cheque and, therefore, the copyright transaction embedded within them. It was still possible for individual contributors to complain about the method and thus avoid assignment. There was a time lapse between transmission of the material and the signing of the copyright cheque, during which time the material lacked any clear owner. Further, cheques that bore the copyright assignment were destroyed after one year, a standard practice but one that removed all written proof that any assignment had actu-ally taken place. Though a useful management tool, clearly reliance on copyright cheques did not provide an adequate legal foundation for ongoing practice.

4. SyNDICATION

The brief given to Russell-Clarke in 1952 included an explicit reference to the news-paper’s efforts at syndication, whereby subscribers to the Times news service could republish articles and features as they thought fit within their country of origin.109 Considering the growing importance of its relationships with other newspapers, broad-casting organisations and film companies, the emphasis on syndication indicates that the newspaper had already begun to characterise copyright in terms of an enlarged notion of proprietorship, commercial opportunity and risk. Syndication had inevitably come to affect the initial creation of newspaper material. Syndication was not concerned with ex post facto circulation of copy. The commissioning of original material was imagined and developed with the aspiration to syndicate it from the outset.

An example of this shift can be seen from the newspaper coverage of expeditions. Since the 1920s, the main sources of funding for expeditions by the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club had come from giving newspapers exclusive copyright of stories, telegrams and pictures.110 These arrangements were mutually beneficial and the possibility of obtaining ‘exclusive rights of a gripping serial’111 was most attractive to the newspapers. The model proved successful. For example, in 1922, The Times attempted to exclusively cover the discovery of the tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amun.112 The British Arc-

109 Parker even insisted on including further references to his ‘general notes on syndication of articles or a series of articles to other newspaper’; see Parker [letter to Richard Butler], 21 January 1955, SB/Copyright and Trade Marks (Copyright: General Correspondence, 1954–9), TNL Archives.

110 Ralph Izzard, An Innocent on Everest (EP Dutton & Co, 1954) 46–47.111 Izzard (n 110) 46–47.112 ‘The Tomb of the King. Contract given to The Times’ The Times (London, 10 January 1923), 11; see also

hVF Winstone, Howard Carter and the Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun (Barzan, 2006) 180–92; Michael Bartholomew, In Search of HV Morton (Methuen, 2006) 62–68; Valentine Williams, The World of Action: The Autobiography of Valentine Williams (hamish hamilton, 1938) 357–72; TGh James, Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun (Tauris Parke Paperback, 2006) 276–83; Thomas hoving, Tutankha-mun: The Untold Story (Simon and Schuster, 1978) 146–65; John Evelyn Wrench, Geoffrey Dawson and our Times (hutchinson, 1955) 212; Alan Gardiner, My Working Years (Coronet Press, 1962) 37–38; hV Morton, Through the Lands of the Bible (Methuen & Co, 1938) 267–9.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

226 Journal of Media Law

tic Route expedition in 1930113 and Paul Bauer’s attempt on Kangchenjunga in 1931114 were also supported by ‘advance’ copyright payments from The Times. Such expeditions were plagued by a number of difficulties that made the media story as interesting as, and inseparable from, the adventure itself.115

The serialised form was an appealing and lucrative practice, not only because it had the potential to extend readership by maintaining interest over time, but also because it opened up the possibility of linking different and supplementary revenue streams: lecture tours, films, photographs and books. An illustration of this ‘land of opportu-nity’ can be seen in the coordination of publicity around the Everest expedition between The Times, hodder & Stoughton, Countryman Films and BBC Television, allowing for windows of exploitation as news-film-book-serialisation-magazine.116 here, payment schemes again played a crucial role in structuring the way in which newspapers invested, reported and ran stories. Advance copyright payments became commonplace in order to secure future copy from high profile sources.117

This new model was radically at odds with the aforementioned major copyright case of Walter v Lane.118 While that case had sought to determine copyright only after the material had been published, newspapers such as The Times found that the valuable material they wanted to exclusively own was now what was not yet published—that yet to be revealed in well-orchestrated and staged releases. Central to this was the attempt to lock, preserve and sell news stories before they happened. Arrangements to secure and relay news stories, photographs and telegrams associated with major events such as the Everest expedition evidenced a shift from reporting events as they happened to seek-ing to control circulation of the story. For a newspaper this fostered a counter-intuitive dynamic: a drive not to report (prematurely). The enemy was now not what copyright law would traditionally define as an infringement of a right but those media activities that targeted its exclusivity and upset the controlled staging of releases, particularly a scoop by a rival newspaper. This new priority was no more apparent than in one of the ‘proudest achievements sponsored by Printing house Square: … the ascent of Everest in 1953’.119 The danger of being scooped affected the preparation for and conducting of the expedition.120

113 R Deakin (The Times) [letter to Charles A Selden (New York Times)], 30 April 1930, New york Times, Mss Coll 17792, New york Public Library, Box 107.3.

114 R Deakin (The Times) [letter to the London Editor (New York Times)], 19 May 1931, New york Times, Mss Coll 17792, New york Public Library, Box 107.3.

115 Nick Conefrey, Everest 1953: The Epic Story of the First Ascent (Oneworld Publications, 2012); Jan Morris, Coronation Everest (Faber & Faber, 2003).

116 himalayan Committee, Report of Sub-Committee on Publicity and Related Matters, 25 June 1953, Royal Geographical Society Archives, RGS/EE/99/2.

117 A later example includes the Churchill memoirs. See generally David Reynolds, In Command of History: Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War (Random house, 2005).

118 Walter v Lane [1900] AC 539.119 The Past and Present of the Newspaper (The Times, 1954) 16.120 ‘The Committee are fully conscious of the importance of avoiding leakage, and think it will be desirable

that before the Expedition starts there should be a meeting between the Leader and Second-in-Command

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

86.1

44.2

36.2

13]

at 0

9:05

26

May

201

5

227From the Author to the Proprietor